Issue 315 | June 2024

Control & Therapy Series

PUBLISHER

Centre for Veterinary Education

Veterinary Science Conference Centre

Regimental Drive

The University of Sydney NSW 2006 + 61 2 9351 7979

cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au

cve.edu.au

Print Post Approval No. 10005007

EDITOR

Lis Churchward

elisabeth.churchward@sydney.edu.au

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Dr Jo Krockenberger joanne.krockenberger@sydney.edu.au

VETERINARY EDITOR

Dr Richard Malik

DESIGNER

Samin Mirgheshmi

ADVERTISING

Lis Churchward elisabeth.churchward@sydney.edu.au

To integrate your brand with C&T in print and digital and to discuss new business opportunities, please contact:

MARKETING & SALES MANAGER

Ines Borovic ines.borovic@sydney.edu.au

DISCLAIMER

All content made available in the Control & Therapy (including articles and videos) may be used by readers (You or Your) for educational purposes only.

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broadens our knowledge, changes in practice, treatment and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate. You are advised to check the most current information provided (1) on procedures featured or (2) by the manufacturer of each product to be administered, to verify the recommended dose or formula, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications.

To the extent permitted by law You acknowledge and agree that:

I. Except for any non-excludable obligations, We give no warranty (express or implied) or guarantee that the content is current, or fit for any use whatsoever. All such information, services and materials are provided ‘as is’ and ‘as available’ without warranty of any kind.

II. All conditions, warranties, guarantees, rights, remedies, liabilities or other terms that may be implied or conferred by statute, custom or the general law that impose any liability or obligation on the University (We) in relation to the educational services We provide to You are expressly excluded; and

III. We have no liability to You or anyone else (including in negligence) for any type of loss, however incurred, in connection with Your use or reliance on the content, including (without limitation) loss of profits, loss of revenue, loss of goodwill, loss of customers, loss of or damage to reputation, loss of capital, downtime costs, loss under or in relation to any other contract, loss of data, loss of use of data or any direct, indirect, economic, special or consequential loss, harm, damage, cost or expense (including legal fees).

An Unexpected Diagnosis of Dirofilaria immitis (Heartworm Infection) in a Dog on Liver FNAs Yuqin

Katrina Cheng

What to Tube & When? Feeding Tube Management & Care Cecilia Villaverde & Sam Taylor ...........................................................20 Research Roundup

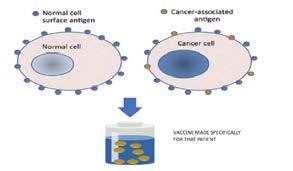

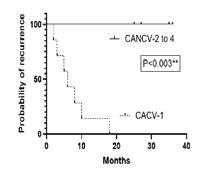

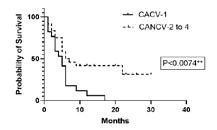

CANCV-4—Canine Autologous Nanoparticle Cancer Vaccine (V4) Immunotherapy for Dogs Chris Weir 27

Treatment of ‘Swamp Cancer’ (Oomycete Infections) In Horses With Metalaxyl-M Andrea Harvey, Sarah Townsend, Jamin Farebrother, Richard Olsen, SallyAnn Olson, Luisa Monteiro de Miranda, Mark Krockenberger, Cathy Shilton, Oliver Liyou & Richard Malik ............................................................................................ 39

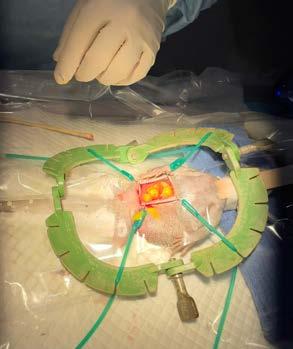

A Canine Desexing Model Utilised by 3rd Year Students in a Tutorial Prior to Their First Live Animal Spey .................................................... 38 Transform Your Passion into Impact: Join Our PhD Program

The C&T forum gives a ‘voice’ to the profession and everyone interested in animal welfare. You don’t have to be a CVE Member to contribute an article—please send your submissions to Dr Jo Krockenberger. joanne.krockenberger@sydney.edu.au

Join In!

The C&T is not a peer-reviewed journal.

We are keen on publishing short, pithy, practical articles (a simple paragraph is fine) that our readers can immediately relate to and utilise. Our editors will assist with English and grammar as required.

I enjoy reading the C&T more than any other veterinary publication.

-Terry King, Veterinary Specialist Services, QLD

The C&T Series thrives due to your generosity.

Vouchers can be used towards membership fees or continuing education courses

Prize: A CVE$500 voucher

Bearded Dragons in Practice

Harry Sollom

Winners Prize: A CVE$100 voucher

An Unexpected Diagnosis of Dirofilaria immitis (Heartworm Infection) in a Dog on Liver FNAs

Yuqin Zhu & Lucy Barker

Heartworm Case in Southwest Sydney

Michael Yazbeck

Necrotising Pancreatitis with Concurrent Chronic Hepatitis in a Dog

Alexander Teh

Enhancing the Euthanasia Experience: An Overview of Advancements in End-of-Life Care and Best Practice

Euthanasia

Jessica Pockett

The C&T thrives due to its unique and altruistic nature: it’s a forum rather than an academic journal. Contributors share their experiences—warts and all—with colleagues to contribute to animal welfare everywhere.

On this special anniversary, the last word goes to its founder Tom Hungerford OBE BVSc FACVSc HAD who wanted a forum for uncensored and unedited material.

Tom wanted to get the clinicians writing:

not the academic correctitudes, not the theoretical niceties, not the super correct platitudes that have passed the panel of review… not what he/she should have done, BUT WHAT HE/ SHE DID, right or wrong, the full detail, revealing the actual ‘blood and dung and guts’ of real practice as it happened, when tired, at night, in the rain in the paddock, poor lighting, no other vet to help.

Now every one of you who has done anything practical that’s not easily obtainable in all the common textbooks, write it up. Being local Australian experience it’s invaluable.

We welcome articles from everyone involved in the profession, worldwide. You don’t have to be a CVE member to contribute.

Email: cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au

Here’s to the next 55 years!

The CVE Team cve.edu.au

Dip-ECVIM

Internal Medicine Specialist

Small Animal Specialist Hospital, Western Sydney

C&T No. 6019

Mojo is a 13-year-old male neutered Maltese Shih Tzu cross that first presented to Small Animal Specialist Hospital Western Sydney emergency service for a sudden collapse at home. The owner reported that Mojo was conscious but laterally recumbent. He recovered in 15 minutes.

The owner also reported that Mojo had a progressively worsening dry cough for over a year. In the last few days, Mojo seemed to have difficulty breathing.

On presentation, Mojo was bright, alert and responsive. His physical examination was unremarkable. General blood profile and thoracic radiographs were recommended for further assessment and investigation. The owner declined this option, and Mojo was discharged for monitoring.

Two weeks later, Mojo presented to the emergency service again for a different reason: acute vomiting and diarrhoea.

A complete history revealed that Mojo was not up to date with vaccines and worm preventatives. His overall energy level had decreased. He was lethargic and had reduced appetite. He had never travelled outside New South Wales.

Mojo was admitted for initial work-ups and supportive care overnight. He was referred to the medicine specialist service the next day for further management and investigation of vomiting and diarrhoea.

The emergency service performed thoracic and abdominal radiographs which were reviewed as unremarkable.

A general blood profile was performed, the blood test result revealed moderately elevated ALT 348 IU/L (10-125), ALKP 2711 U/L (23-212), moderate hypercholesterolaemia CHOL 12.29 mmo/L (2.84-8.26), and mild hyperproteinaemia TP 86 g/L (52-82) with mild hyperglobulinaemia GLOB 50 g/L (25-45).

Due to the elevated liver enzyme values, abdominal ultrasound was recommended.

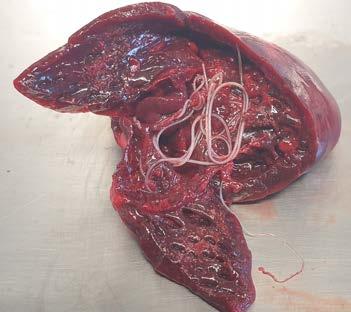

On ultrasound, the liver was enlarged with a diffuse patchy parenchyma (Figure 1). There was sonographic evidence of renal cysts, splenic nodules, and pancreatic changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis. The cause of vomiting and diarrhoea remained open, but due to hepatic changes, fine needle aspirates of liver were taken and submitted for cytology.

Mojo’s gastrointestinal signs improved with supportive care during hospitalisation (Hartmann’s solution at 1x maintenance rate 13mL/hr, and maropitant 1mg/kg IV q 24 hours), therefore suspected to be consistent with acute gastroenteritis or dietary indiscretion. He was discharged while pending liver aspirates result.

Surprisingly, the cytology results returned for Mojo revealed Dirofilaria immitis microfilariae within the hepatic parenchyma (Figure 2). Although an unexpected finding, these results were consistent with heartworm infestation. Based on these results, heartworm antigen test was added, and it came back positive. Due to the presence of circulating microfilariae in the liver, a microfilariae blood test was not performed.

The thoracic radiographs taken by the emergency service were reviewed by the radiology specialists but there was no evidence of significant heart disease, and changes in the pulmonary artery were not seen.

Though not evident on thoracic radiographs, heartworm infection is suspected to be the answer to Mojo’s chronic coughing and intermittent weakness. The concern is that his collapse event may also have reflected pulmonary thromboembolism. The owner declined performing echocardiogram to investigate the extent of cardiac changes further.

Mojo received American Heartworm Society’s recommended heartworm treatment protocol¹ (Table 1) The treatment was commenced two days after diagnosis.

Figure 2. Dirofilaria immitis microfilaria within the hepatic parenchyma (Photomicrographs courtesy of Dr George Reppas Vetnostics)

Mojo was last seen by the medicine specialist service on Days 61, 90 and 91 for melarsomine injections. Since the treatment started, Mojo had been doing well with improved energy level and appetite. No more collapse episodes were observed. Cough was ongoing but improved.

The owner reported that Mojo was lethargic and inappetent for approximately 12 hours after the second melarsomine injection, then spontaneously returned to normal. No other concerns were reported.

Overall, Mojo showed a positive response to treatment. His case has been lost to follow-up, so repeated microfilariae testing has not been performed.

This case implies that despite now being classed a rare diagnosis, heartworm infection still exists around the Greater Sydney Region (Mojo had never travelled outside of Western Sydney in his lifetime).

Therefore, veterinarians should continue to stay vigilant for this infectious disease and continue raising client awareness on the risks of this infection, especially in animals who are not up-to-date with heartworm preventatives. For dogs that present to clinic with clinical signs of cardiac or respiratory disease, with a lapse of heartworm prevention, heartworm antigen test is strongly recommended. Regular heartworm prevention should remain as an important part of all pets’ health care plan.

1. American Heartworm Society. (2018). Current Canine Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Dogs heartwormsociety.org/images/pdf/2018AHS-Canine-Guidelines.pdf

Day 0 In a dog diagnosed and verified as heartworm positive:

Positive antigen (Ag) test verified with microfilaria (MF) test

If no MF are detected, confirm with second Ag test from a different manufacturer

Apply an EPA-registered canine topical product labeled to repel and kill mosquitoes

Begin exercise restriction—the more pronounced the signs, the stricter the exercise restriction

If the dog is symptomatic:

Stabilize with appropriate therapy and nursing care

Prednisone prescribed at 0.5 mg/kg BID first week, 0.5 mg/kg SID second week, 0.5 mg/kg every other day (EOD) for the third and fourth weeks

Apply frontline plus (Fipronil 9.8%, (S)-methoprene 8.8%)

Begin exercise restriction

Start steroids Prednisolone 5mg twice daily for first week, 5mg once daily for second week, 5mg every other day for the third and fourth weeks

Chlorphenamine 4mg one

tablet orally twice daily

Day 1

Administer appropriate heartworm preventive

y If MF are detected, pre-treat with antihistamine and glucocorticosteroids, if not already on prednisone, to reduce risk of anaphylaxis

y Observe for at least 8 hours for signs of reaction

Administer milbemycin oxime

Days 1-28

Administer doxycycline 10 mg/kg BID for 4 weeks

Reduces pathology associated with dead heartworms

Disrupts heartworm transmission

Day 30 Administer appropriate heartworm preventive

Apply an EPA-registered canine topical product to repel and kill mosquitoes

Days 31-60 A one-month wait period following doxycycline before administering melarsomine is currently recommended as it is hypothesized to allow time for the Wolbachia surface proteins and other metabolites to dissipate before killing the adult worms. It also allows more time for the worms to wither as they become unthrifty after the Wolbachia endosymbionts are eliminated.

Day 61

Administer appropriate heartworm preventative

Administer first melarsomine injection, 2.5 mg/kg intramuscularly (IM)

Prescribe prednisone 0.5 mg/kg BID first week, 0.5 mg/kg SID second week, 0.5 mg/ kg EOD for the third and fourth weeks

Decrease activity level even further: cage restriction; on leash when using yard

Administer doxycycline 75mg PO BID for 4 weeks

Administer milbemycin oxime

Apply frontline plus

The owner rested Mojo for the next month with no medication to be given.

Administer milbemycin oxime

Apply frontline plus Administer first melarsomine injection (0.65mL) IM

Prednisolone 5mg twice daily for first week, 5mg once daily for second week, 5mg every other day for the third and fourth weeks

Table 1. American Heartworm Society’s recommended heartworm treatment protocol and Mojo’s treatment schedule

Day 90

Administer appropriate heartworm preventative

Administer second melarsomine injection, 2.5 mg/kg IM

Prescribe prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg BID first week, 0.5 mg/kg SID second week, 0.5 mg/ kg EOD for the third and fourth weeks

Day 91

Administer third melarsomine injection, 2.5 mg/kg IM

Continue exercise restriction for 6 to 8 weeks following last melarsomine injections

Day 120 Test for presence of MF

y If positive treat with a microfilaricide and retest in 4 weeks

Continue a year-round heartworm prevention program based on risk assessment

Day 365 Antigen test 9 months after last melarsomine injection; screen for MF

If still Ag positive, re-treat with doxycycline followed by two doses of melarsomine 24 hours apart

Administer milbemycin oxime

Apply frontline plus Administer second melarsomine injection (0.65mL) IM

Prednisolone 5mg twice daily for first week, 5mg once daily for second week, 5mg every other day for the third and fourth weeks

Continue to restrict exercise for 8 weeks

Administer third melarsomine injection (0.65mL) IM

Administer prednisolone as prescribed

Continue to restrict exercise for 8 weeks

A heartworm test is recommended. It is recommended to continue a heartworm preventative medication.

A repeat heartworm test is recommended. If this test remains positive, further/repeat treatment with injections would likely be recommended.

Table 1. American Heartworm Society’s recommended heartworm treatment protocol and Mojo’s treatment schedule

The second book will be a celebration of all things veterinary, the days when everything went well and the days when it didn’t. It’s going to be second collector’s item—a coffee table showpiece—so don’t miss the opportunity to be a part of it.

The CVE is again donating resources and expertise free of charge to design, deliver and market this second edition. Thanks to the contributors and sponsors who made the first Vet Cookbook

Or earlier—first in, first published

Upload your recipe: cve.edu.au/vet-cookbook

Winner

Entitled to a CVE$100 voucher

Greencross Vets Campbelltown

3 Blaxland Serviceway

Campbelltown NSW 2560

t. 02 9146 1163

e. michael.yazbeck@greencrossvet.com.au

C&T No. 6020

History

Sheba, an 11 1/2-year-old female speyed Chihuahua, presented for a 2-day history of hyporexia, lethargy and laboured breathing. Gradual weight loss was noted over the preceding 2 weeks and there was no coughing, sneezing, vomiting or diarrhoea. She was not on any medications or supplements, and her usual diet consisted of commercial wet and dry dog food and home cooked meals. She was on an isoxazoline drug for parasite prevention, which was last administered approximately 4 weeks prior and was believed to be upto-date with this regime for an unknown number of years, but prior to this her parasite prophylaxis was unknown.

She was acquired at 6 to 8 weeks old from a local market in Southwest Sydney and has lived locally ever since with no history of travel. She’s had no significant medical history, except for a broken right hindlimb at 8-weeks-old.

Examination

Sheba was quiet, alert and responsive with a 5/6 systolic heart murmur and normal pulses. She was mildly tachypnoeic with a mild to moderate increase in respiratory effort and crackles on auscultation. She had pale pink mucous membranes and periodontal disease. She was mildly hypothermic, had a lean body condition and her right hindlimb was non-weight bearing. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

Inhouse biochemistry and CBC were performed, which revealed a PCV of 19% and total protein of 68 g/L. There were mild elevations in glucose, BUN, ALP and AST. The CBC revealed a normocytic, normochromic moderate non/pre-regenerative anaemia (reticulocytes not included) and mild thrombocytopaenia. Polychromasia was noted on the blood smear.

Sheba was provided flow-by oxygen and a thoracic point of care ultrasound was performed. The LA:Ao ratio was 1.7 indicating mild left atrial enlargement; there were occasional B lines present, and pleural space disease was excluded based on the absence of pleural effusion and pneumothorax (glide sign present). Surprisingly, there were a number of segments of hyperechoic, parallel lines within the right ventricle, indicative of heartworm infection. The finding was supported by a positive heartworm antigen test.

Conscious thoracic radiographs were taken, which highlight the very dilated and tortuous pulmonary lobar arteries in the lateral and dorsoventral views (credit to Dr Catheryn Walsh), consistent with heartworm infection. Cardiomegaly was appreciated; however, the left atrium did not appear obviously enlarged on radiographs and there was no obvious interstitial to alveolar pattern consistent with left-sided congestive heart failure.

Although recently published data Australia-wide is lacking, Zoetis have been encouraging vets to report heartworm cases onto a company website and have advised that over 3,000 positive cases have been reported from practices Australia-wide since 2017, of which approximately 10% are external to Queensland.

Despite not being commonly encountered in Sydney, this case serves to remind vets to continue to inform pet owners on heartworm disease, to recommend diligent heartworm prevention and to maintain heartworm disease as a differential diagnosis for cardiorespiratory cases, even in the absence of a more typical locality or history of travel. Sheba represents a signalment where myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) and leftsided congestive heart failure, or primary airway diseases, are highest on the differential diagnosis list for similar case presentations. Sadly, due to multiple patient factors, Sheba was euthanased. Her owners hope her case may raise awareness of the risk of heartworm disease in our local area and Australia-wide.

Heartworm is transmitted by mosquitoes, the obligate intermediate host. Heartworm infection causes a spectrum of disease, ranging from subclinical to severe pulmonary disease and secondary right-sided congestive heart failure due to the presence of worms in the pulmonary arteries and heart (and potentially vena cava), the host-parasite interaction and modulation by the intracellular bacterium, Wolbachia

Anaemia, as in this case, can be caused by inflammatory disease or the shearing of the red blood cells as they flow past the worms, causing intravascular haemolysis. The thrombocytopaenia was likely due to consumption in the pulmonary arterial system or artefact due to clumping. The mildly elevated BUN was likely pre-renal, or due to immune-complex glomerulonephritis. The mildly elevated ALP may have been due to passive congestion of

the liver or an unrelated process. The elevated AST could have been due to intravascular haemolysis, or concurrent hepatopathy or myopathy. Ideally, a urinalysis could have been performed to screen for haemoglobinuria (suggestive of intravascular haemolysis), proteinuria and to assess USG. If treatment was to be pursued, a proper echocardiogram would be recommended to detect concurrent abnormalities, such as MMVD, pulmonary hypertension, pericardial effusion and caval syndrome. 1 3 4 5 2

Figure 4. Tortuous pulmonary artery on lateral view

Figure 5. Visit the open access eBook to view the video

Figure 1. Heartworm evident on echo

Figure 2. Heartworm evident on echo

Figure 3. Tortuous pulmonary artery on dorsoventral view

Figure 1. Heartworm evident on echo

Figure 2. Heartworm evident on echo

Figure 3. Tortuous pulmonary artery on dorsoventral view

University of Sydney e. jan.slapeta@sydney.edu.au

These two intriguing cases of canine heartworm serve as compelling evidence that Dirofilaria immitis is not as ‘extinct’ in New South Wales as thought. The first case is reminiscent of a similar instance we encountered at the University Veterinary Teaching Hospital Sydney a couple of years ago.1 In smaller breeds, ultrasound proves invaluable, as the distinct ‘tram-tracks’ are an unmistakable telltale sign. Utilising X-rays to visualise the tortuous pulmonary artery is a crucial aspect of heartworm disease assessment. Despite these two cases, Sydney remains comparatively hypo-endemic to Far North Queensland for D. immitis.

In the McKeever et al 1 case report, we speculated that occurrences like these may stem from what could be termed ‘baggage heartworm’. This occurs when infected mosquitoes, vectors of D. immitis, are inadvertently transported in luggage from endemic areas such as Far North Queensland. It is analogous to ‘baggage malaria’ in humans in non-endemic regions.2

Though there is no recent epidemiological data for New South Wales, two recent studies are relevant. One involving around 400 dogs from New South Wales found none tested positive for D. immitis antigen.3 However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, given the irregular (not normal) distribution of parasites. Another study in Queensland shelters revealed a high prevalence of D. immitis (~20%) in Far North Queensland and a lower prevalence (~5%) in Southern Queensland pound dogs.4 Unfortunately, a similar study in New South Wales is not feasible due to legislation barring research on impounded dogs, and that includes collection of few millilitres of blood for such research purpose.

One can infer that compared to Queensland, the incidence of D. immitis infection in New South Wales is currently lower. However, the situation is dynamic, particularly with the weather patterns observed in recent years. Not too long ago (1980s to 1990s), D. immitis infection was a common diagnosis in Sydney, with figures similar to those now reported by colleagues in Far North Queensland.

The detection of microfilariae in liver biopsies is certainly feasible in dogs with patent D. immitis infection. Counts vary significantly in positive dogs; we have seen counts exceeding 50,000 microfilariae per mL. However, not all D. immitispositive dogs have circulating microfilariae. In Australia, 30-50% of D. immitis-positive dogs are amicrofilaremic, often with single-sex infections.

While I advocate for the use of rapid antigen tests (RAT), I still emphasise the necessity of checking suspect positive dogs for microfilariae. Performing tests like the Knott’s test in-clinic is essential. This simple yet effective test not only confirms diagnosis but also assesses the risk posed by the infected dog to others. Access to a microscope and centrifuge makes conducting the Knott’s test feasible for any practitioner.

1. McKeever B, Podadera JM, Beijerink NJ, Slapeta J. Suspect ‘baggage canine heartworm’ case: canine heartworm disease in a dog from Sydney, New South Wales. Aust Vet J 2021;99:359-362. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.13074

2. Mantel CF, Klose C, Scheurer S, Vogel R, Wesirow AL, Bienzle U. Plasmodium falciparum malaria acquired in Berlin, Germany. Lancet 1995;346:320-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92212-1

3. Orr B, Ma G, Koh WL, Malik R, Norris JM, Westman ME, Wigney D, Brown G, Ward MP, Slapeta J. Pig-hunting dogs are an at-risk population for canine heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in eastern Australia. Parasit Vectors 2020;13:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-3943-4

4. Panetta JL, Calvani NED, Orr B, Nicoletti AG, Ward MP, Slapeta J. Multiple diagnostic tests demonstrate an increased risk of canine heartworm disease in northern Queensland, Australia. Parasit Vectors 2021;14:393. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04896-y

“The American Heartworm Society and the European Society of Dirofilariosis and Angiostrongylosis currently suggest a monthly treatment based on macrocyclic lactones (ML)(e.g. moxidectin) along with doxycycline for a 4-week period as an alternative to melarsomine.”

Treatment with Moxi/doxy is a bit contested. No one actually argues that it works but there are 3 potential issues that have been flagged over the years:

1. Owner compliance is required for an extended period of time.

2. Resistance to DOX in Wolbachia or any other bacteria (theoretically human ones as well).

3. Resistance to MOX (=ML) in Dirofilaria.

Plus the requirement to use whatever is registered in US first makes MOXI-DOXY bit of a liability for the vets there.

When I tell students about it, I call it 'slow kill'compared to “fast kill” with Immiticide.

Fast kill is mostly under control of the vet (assuming the owners actually decide to come back after the first round of Immiticide) and is completed in 3-4 months. With slow kill, you treat for 2-3 years, assuming they are compliant, and vets need to justify that having few dying worms is kind of ok [it seems it is].

parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.1186/s13071-023-05690-8

e. richard.malik@sydney.edu.au

I think the America HW Society treatment guidelines are far too influenced by vets in the USA. The treatment protocol is highly complex and VERY expensive. Many vets’ visits – lots of changes and different drugs.

The newer treatment using doxycycline and moxidectin is IN MY OPINION just as effective, just as safe and should be industry standard medicine.

In cats – we have been accidentally doing this for many years - as killing worms SUDDENLY in cats often kills the cats – so we just stuck them on monthly prevention. So, I was already thinking in this direction when the Italians dreamed up killing the endosymbiont Wolbachia, and then slowly killing the adults with moxidectin.

I don’t want to force my view on everyone – but that’s MY considered opinion. 4 weeks of VibraVet and a year of Advocate – is SO MUCH CHEAPER than following the US guidelines. Also easy to remember!

Christopher Simpson

Victoria Veterinary Clinics

Hong Kong

e. simpson_christo@icloud.com

The AHS guidelines protocol is absolutely not a benign process. Over the years I can recall multiple dogs which have dropped dead in the first or second day after one of the Immiticide injections.

So far, I have never seen that happen with Moxi/Doxy.

It is now close to ‘standard of care’ in our practice. We use it routinely in Class 1 and 2 disease.

If our regular clients come to us with a HW patient, we will explain that the American Heartworm Society ( AHS) Guidelines exist, and are probably the most formally recognised option, but that we have good recent experience with an “alternative” protocol which we consider has significant potential advantages. Our good clients will then usually ask us to choose what we think is best, and trust our judgement.

We choose to use the AHS protocol in three scenarios:

a. if the dog is in heart failure due to a very heavy intracardiac burden (causing severe tricuspid regurgitation)

b. if the client is not well known to us, and we want to do things “by the book” for medico-legal reasons

c. if we have tried the Moxi/doxy protocol and no evidence of efficacy at the 6-month recheck (this has happened once).

We still do both, as above, and in most cases Moxi/doxy is smoother, cheaper, strongly preferred by the clients, and appears highly effective in many cases in our anecdotal experience.

I would be interested to see an randomised controlled trial comparing the two, but of course I never will…

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8353148/

Queensland

C&T No. 6021

A 6-month-old female Australian Cattle Dog (recently desexed), weighing 15kg, presented one evening after the owners had arrived home to find her in a collapsed state. She had been observed as normal that morning and was locked up with no access to intoxications or envenomations that day. She was a compost eater and had been seen regularly eating the remnants of chicken feed (containing amprolium).

Initial clinical examination revealed temperature 38.8ºC, HR 170, panting, MM pink, CRT 1+ seconds with tachycardia the only recorded thoracic auscultation abnormality. Neurologically she was recumbent and unable to move, although she was hyperaesthetic to stimuli; pupils were dilated and unresponsive with mild bilateral third eyelid protrusion. CBC/MBA/ACT were essentially normal. The dog was treated with diazepam, vitamin B1 injection, and IV fluids. She was discharged to owner care the next morning, a mild ataxia the only residual symptom.

She was represented the following evening when the owners returned home to find her again (in her locked room) collapsed and unresponsive. Physical examination on representation showed a recumbent, seemingly comatose adolescent dog with temperature 37.8ºC, HR 160, RR 52, MM pink, CRT 1+ seconds. Her ocular palpebrae were shut and on examination, her pupils were pin-points, bilaterally. Some response was elicited with vigorous stimulation, e.g. placement of an intra-nasal oxygen line, urinary catheter placement; she displayed an exaggerated hyperaesthetic response to subcutaneous injections. Abdominal palpation indicated very firm, cranial abdominal organomegaly.

CBC/MBA were again normal. Abdominal ultrasound examination revealed a markedly distended stomach creating marked gaseous shadowing with the spleen displaced caudally. A right lateral abdominal radiograph revealed a distended food-filled stomach.

Methadone 0.25 mg/kg was given IM, she was intubated, and gastric lavage was performed without any other chemical restraint—this procedure returned copious amounts of sodden pellets of dry dog food (owners subsequently reported that she had eaten a huge amount of dry dog food after going home that morning).

Oxygen therapy ceased after extubation, IV fluids were continued, and Vitamin B1 was administered at 250mg IM.

Within 12 hours, the pup was assessed as being normal neurologically with all vital signs normal. She was again discharged to her owner’s care; the treatment prescribed was Vitamin B1 (thiamine) 100mg PO Daily for a minimum of 3 weeks. Stopping access to the household’s chicken feed was also prescribed. Subsequently, amprolium was detected in the gastric lavage contents by laboratory analysis. The dog was normal at follow-up examination a week later and was reported as being normal at 3 week and 3-month phone follow-up.

The coccidiostat Amprolium hydrochloride is 1-[(4-amino-2-propyl-5-pyrimidinyl) methyl]-2ethylpyridinum chloride which is used in the prevention and treatment of coccidiosis in chickens and turkeys. A structural analogue of Vitamin B1 (thiamine) it competitively inhibits thiamine utilisation by parasites (coccidia).

Amprolium is not considered to have antimicrobial activity other than its action on coccidia; it does not possess any significant antibacterial activity. Amprolium is authorised as a feed additive for poultry at concentrations in the range of 62.5-125 mg/kg of complete feed; the authorisation prohibits the use of the substance from laying age onwards and for at least 3 days before slaughter.

Amprolium is a thiamine (vitamin B1) analogue and is a competitive antagonist of thiamine transport mechanisms. The affinity for the blood-brain uptake system is similar to that of thiamine. At sub-optimal dietary intakes of thiamine, amprolium can cause decreases in body weight gain and tissue thiamine concentrations, suggesting a selective inhibition of thiamine uptake. With oral ingestion, peak plasma activity is reached within 4 hours after a meal containing amprolium and declines gradually over 24 hours. With continuous access to amprolium-containing feeds, peak concentrations are maintained at a steady state. Total excretion approximates 90%, with the faeces being the major route of excretion (~80%); urinary excretion accounts for some 9-10% of the total dose.

Parent amprolium—up to 50% of the amount ingested—is excreted unchanged in the faeces. Significant tissue concentrations are rapidly reached in the liver and gastrointestinal tract and up to 17 metabolites are detectable in the liver and muscles (within 4 hours), and urine (continuously for up to 7 days).

In experimental studies, acute toxicity causing death within 36 hours occurs in dogs receiving an oral dose of 500mg/kg amprolium; signs of toxicity included emesis, head drooping, ataxia, loss of righting reflex, tremors and dyspnoea. In comparison, a single oral dose of 300mg/kg amprolium produced no clinical signs.

The concurrent supplementation with thiamine in trials with lower doses of amprolium (up to 300 mg/kg) did not improve survival, but clinical signs (similar to the acute toxicity signs) resulting in death took up to 16 weeks to emerge, especially if amprolium-meals were limited to 5 days weekly. There were no substance-related effects on cardiovascular parameters or none could be detected on ophthalmoscopic examination; haematology, biochemistry and routine urinalysis values were normal. The major signs of toxicity included pupillary dilatation, paralysis and collapse. Supportive studies have established a NOEL (non-observed effect level) of 100mg/kg.

A degenerative encephalomyelopathy in seven out of ten Kuvasz puppies was suspected to be due to the effects of an amprolium-induced thiamine deficiency on the developing brains of those puppies. The litter was treated, beginning at 4.5 weeks of age, with amprolium 48mg/dog/day for 10 days for the prevention of coccidiosis. Dragging of the hindlimbs and lethargy was noticed in all the pups around the end of the treatment, and four of the pups showed progressive ataxia, weakness, and reluctance to rise over a 4-to-5-month period. Neurological examination indicated a diffuse or multifocal lesion involving the thalamocortex, the rostral medulla (with signs suggesting vestibular-cerebellar connection involvement) and possibly the spinal cord.

A second litter from the same parents had amprolium coccidiostat prevention stopped after 6 days (initiated at 4 weeks of age) because 3 of the 5 pups showed trembling that progressed rapidly to a crawling gait (inability to stand). Thiamine supplementation was instituted at 50 mg/pup/day for 5 months; improvement was slow, ending with mild weakness and ataxia with reduced exercise tolerance and reduced learning ability (subjective observation). On neurological examination, all pups showed cerebellar ataxia (with truncal ataxia and dysmetria), decreased proprioception (more pronounced in the hindlimbs), and variable degrees of ventral strabismus on elevation and extension of the head and neck. The signs these pups showed suggest diffuse

central nervous lesion involving the thalamocortex, cerebrum, vestibular (central) systems, and spinal cord.

Postmortems were performed in 3 of the pups from each of the litters, and microscopic lesions were seen in all 6, with focal necrosis of the caudate nucleus and gliosis with spongy change in the cerebellar nuclei the most prominent and consistent findings. Spongy change was seen in other areas, including the spinal cord (mostly the descending tracts), in all 6 pups necropsied.

2 subsequent litters that were not treated with amprolium produced 14 normal puppies; these were from the same bitch but a different sire.

It would seem that the amount given to each of these pups (50mg/pup/day) falls well within the recommended safety margin for amprolium (200mg/dog/day for no longer than 14 days), unless an accidental overdose was given, which seems unlikely. Plumb (5th Edition) states that prolonged high doses can cause thiamine deficiency in the host, and it is not recommended to be used for over 12 days in puppies.

Plumb also states that exogenously administered thiamine in high doses may reverse or reduce the efficacy of amprolium. The fact that the second litter improved with thiamine supplementation supports the implication of amprolium in the onset of signs, either as a direct toxicosis or its associated thiamine deficiency, especially as the lesions were bilateral and lacking in inflammation. The very young age of the puppies (immature metabolism neurologically and systemically, and undeveloped blood brain barrier integrity perhaps augmenting the neurotoxicity of the amprolium), as well as the possible predisposition of an exotic breed may help explain why this presentation hasn’t been described before.

No functional tests for vitamin B1 status in the blood were performed on this ACD adolescent (the case study above), and no urinary organic acid assays were done that may indicate a deficiency of at least one of the components of the dehydrogenase complex using thiamine pyrophosphate as a cofactor—blood levels of thiamine can be performed but the laboratory process is difficult (need to discuss with the lab). However, the detection of the thiamine inhibitor, amprolium, in the gastric contents of the dog showing bizarre acute neurological signs that resolved with thiamine supplementation, is compelling evidence of overdosage of this product inducing acute thiamine deficient neurotoxicity.

Reference

Murray J. Hazlett, Laura L. Smith-Maxie, Alexander de Lahunta (May 2005), Case Report: A degenerative encephalomyelopathy in 7 Kuvasz puppies, CanVetJ Volume 46.

The Cat Clinic, Hobart

t. +613 6227 8000

e. moira@catvethobart.com.au

C&T No. 6022

Bingo is a 3-year-old male neuter domestic long hair cat. He presented to our clinic for his first vaccination as an 850 g kitten that had been found as a stray with a suspected female litter mate. He was a healthy kitten. He received his full kitten vaccination course and had a routine castration at 11-weeks-of-age.

He had a dental procedure at 11 months-of-age where 106, 109, 206 and 209 were extracted with gingivoplasty performed on 309 due to marked gingival hyperplasia. He had an unremarkable recovery.

In August of this year, he presented for ear flicking and a black substance in his ears. His owners had done some googling and diagnosed ear mites. He lived with 2 other cats at home and 2 dogs; interestingly, no other animals within the household had similar clinical signs. Bingo is meant to be an inside only cat but did have a habit of escaping every now and then. On examination, only his ears were affected and he had no other skin issues. Bilaterally, his ears had a crusty brown discharge

with friable tissue which bled after swabbing (Figure 1) On microscopic examination of the swabs taken from the ears there were no mites, Malassezia or bacteria detected. There were occasional neutrophils and many red blood cells.

Initial treatment included 5mg prednisolone PO SID and Dermotic topical ear ointment applied to the external cartilage and rubbed into the canal (taking care with application on the friable tissues). Bingo was very distressed about visiting the vets and PVP’s (pre visit pharmaceuticals- pregabalin) was also dispensed for future visits to the clinic.

Bingo revisited 7 days later. His ears were not much improved. He had a moist brown discharge within the canals, the external cartilage was thickened and inflamed. He resented examination of his ears, although he had had a positive response to the PVP’s. On cytology, there were minimal red blood cells but many squames and cocci were seen. Oral antibiotics were dispensed (amoxyclav 75 mg BID PO) and a revisit arranged for 14 days.

At his revisit 14 days later, both pinnae and canals were thickened, proliferative and hardened (see images). Repeated cytology again showed many squames and bacteria.

He was admitted to hospital for sedation and biopsies. Multiple biopsies were taken from both ears and samples submitted to VPDS, the University of Sydney, for histopathology. A tentative diagnosis of feline proliferative and necrotising otitis externa was made.

His antibiotics (due to diarrhoea with blood), prednisolone and Demotic were ceased. We applied a fentanyl (25 µg/hr) patch for analgesia (his ears looked very painful), started metacam oral (2.5 mg SID PO) and Pro-kolin (2mL BID PO) for his diarrhoea. Two days later,

Figure 1. External ear canal of Bingo. Note the blackish proliferative lesions emanating from the external ear canal.

Figure 1. External ear canal of Bingo. Note the blackish proliferative lesions emanating from the external ear canal.

The findings are similar across the specimens with varying degrees of severity. There is marked hyperplastic thickening of the epidermis with marked orthokeratotic and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis. There is a moderate pallor of the stratum spinulosum, proliferation of the stratum basale, with variable degrees of epidermal spongiosis present. Scattered apoptotic cells are present. Underlying sebaceous glands are frequently hyperplastic and apocrines frequently dilated. There is a mild superficial dermal perivascular inflammatory infiltrate of small lymphocytes and plasma cells and occasionally neutrophils. In many of the specimens, there is increased density of the connective tissue of the superficial dermis with relative lack of hair follicles, consistent with scarring.

Marked multifocal epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and surface necrosis

his owners called to say he smelt like ‘roadkill’. His stools were now normal but his owners were happy to start antibiotic cover again.

A diagnosis of feline proliferative and necrotising otitis externa was confirmed, see Uni Syd Report below. 0.03 % tacrolimus ointment was ordered from BOVA and started. Due to having never seen this condition prior, I was unsure as to how to apply the ointment to his ears. In the end his owner and I decided that she would apply the ointment to the areas that she could easily apply it to using her finger and hoped that it would ooze into his canals.

His owner recently reported that Bingo was responding really well to the 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. We are waiting for him to come back in for examination and photos.

The histopathology appears to be broadly consistent with the clinical suspicion of proliferative and necrotising otitis externa, although the feature of that condition is reported to have a severe acanthosis of the outer root sheath of hair follicles with increased apoptosis of epidermal cells. These were not prominent features in this case. Few of the samples had good numbers of hair follicles included in the specimens and the dermal scarring and relative lack of follicles may reflect past damage.

While viral cytopathic features are not evident in this case, a viral aetiology cannot be excluded as a possibility. Mauldlin et al Veterinary Dermatology 18(5):370-377

Figure 3. The external ear canal after a good clean-upResident in Anatomical Pathology

SSVS, The University of Sydney e. alexander.teh@sydney.edu.au

C&T No. 6023

Signalment, History, and Clinical Presentation

A 13-year-old female entire Staffordshire Bull Terrier cross presented to the University Veterinary Teaching Hospital Sydney for chronic weight loss and inappetence over a duration of approximately two to three months.

She later re-presented for worsening lethargy and developed acute respiratory distress and tachypnoea with a marked abdominal effort. Her oxygen saturation levels were reduced (SpO2 89-90%) and she became oxygen dependent.

She continued to deteriorate clinically and was ultimately euthanised and submitted for a post-mortem examination.

Bloodwork

Haematology revealed a moderate non-regenerative normocytic normochromic anaemia with mild hyperproteinaemia, thrombocytopaenia, and segmented neutrophilia with monocytosis. The plasma appearance was moderately lipaemic.

Figure 1. Abdominal organs at necropsy

Figure 1. Abdominal organs at necropsy

Biochemistry revealed mild elevations in amylase, ALP, globulins, urea, and C-reactive protein, and a slight hypoalbuminaemia.

At necropsy, a number of changes were identified primarily within the abdominal cavity. The liver was enlarged and firm with an irregular to slightly nodular capsular surface and an orange-yellow tinge. The common bile duct was patent, and bile was readily expressed from the gallbladder with mild pressure.

The pancreas was markedly enlarged and firm with an irregular surface and there were variable degrees of erythema and a few fibrin strands in the surrounding mesentery. Grossly, it appeared consistent with a severe necrotising pancreatitis with associated fibrinous peritonitis.

The abdomen also contained approximately 5mL of thin turbid dark orange fluid which was collected for fluid analysis and cytology.

Analysis of the abdominal fluid yielded the following information:

Protein: 47g/L (refractometer)

Nucleated cells: 8575 x 10⁶/L

Erythrocytes: 28,000 x 10⁶/L

Cytology of the fluid revealed a population of predominantly non-lytic neutrophils with a few reactive mesothelial cells and macrophages.

Overall, the abdominal fluid was consistent with a nonseptic exudate

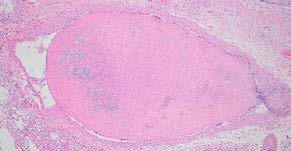

Histopathology of the pancreas confirmed necrotising pancreatitis with surrounding peritonitis and fat necrosis (Figure 3)

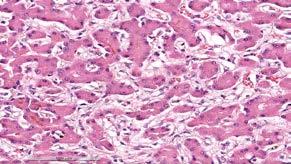

Additionally, pulmonary thromboembolism was identified in the lungs (Figure 4) which likely accounted for the patient’s acute respiratory distress.

The liver had evidence of widespread fibrosis with an interesting intra-sinusoidal pattern (Figure 5) Intrahepatic cholestasis was additionally observed. Chronic hepatitis likely accounted for the patient’s chronic weight loss and hyporexia, and the extensive fibrosis was the presumptive cause of the liver firmness at necropsy. In the liver, special stains for copper (Rubeanic acid) and iron (Perl’s Prussian Blue) were both negative.

5. Hepatic sinusoidal fibrosis with bile plugs within bile canaliculi and hepatocytes indicative of intrahepatic cholestasis

In dogs, the cause of necrotising pancreatitis is often unknown or obscure, as in this case. Trauma, hypoperfusion, and/or nutritional factors (high fat diets) are possible contributing factors. Clinical signs usually associated with acute pancreatitis include vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain. Severe necrotising pancreatitis is associated with a number of serious lifethreatening complications including shock, SIRS, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS), sepsis, consumptive coagulopathies, and death.

Figure 3. Severe necrotising pancreatitis Figure 4. A massive pulmonary thrombusPulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) is a known but relatively uncommon complication of pancreatitis in both human and veterinary medicine. Presenting clinical signs can include an acute onset of dyspnoea/ respiratory distress and hypoxaemia. In this case, PTE was presumably due to a combination of blood hypercoagulability and endothelial injury related to the pancreatitis. Severe necrotising pancreatitis is often related to the systemic release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-a, IL-1 and IL-8 resulting in hypercytokinaemia/cytokine storms which altogether contribute to blood hypercoagulability (thrombophilia). Additionally, widespread tissue damage and necrosis inflict endothelial damage further exacerbating the patient’s thrombotic state.

In dogs, most cases of chronic hepatitis are idiopathic and presenting clinical signs can be non-specific and vague. However, known causes of canine chronic hepatitis include copper and iron-associated hepatopathies, metabolic disturbances, toxicity, infection, and possibly immune-mediated mechanisms. In this case, an overt inciting cause of the chronic hepatitis was difficult to identify. Copper and iron excess were not detected with special stains.

If the owners had unlimited emotional and financial commitment to the patient, how would have you investigated the case to arrive at a definitive diagnosis, and how would you have treated the case?

Email cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au Best complete answer will receive a CVE $100 voucher!

Dr Natalie Courtman

Associate Professor of Veterinary Clinical Pathology

Veterinary Pathology Diagnostic Services, Sydney School of Veterinary Science

t. +61 2 9351 3099

e. natalie.courtman@sydney.edu.au

C&T No. 6024

Thank you to all our readers who answered the What’s Your Diagnosis. The most common answer given was histiocytoma.

This case is a cutaneous poorly pigmented melanoma. The cytologic appearance of the cells is very similar to a histiocytoma but there are two key (but subtle) differences. Firstly, some of the cells contain a fine dusting of green pigment in the cytoplasm which is consistent with melanin. This is not expected with a histiocytoma but is expected in a melanoma, melanocytoma or pigmented epithelial cell tumour. The cells being round and not cohesive makes epithelial origin unlikely. Secondly, the nuceloli are prominent in these cells and sometimes quite large which is not expected with a histiocytoma nor a melanocytoma, but is a characteristic feature of melanoma (which is a malignant tumour).

of the cytology smear is shown below.

A 13-year-old neutered female Staffordshire bull terrier was referred for evaluation of a raised round 2cm pigmented haired left foreleg mass above the carpal pad. Fine needle aspirate smears were prepared from the mass and stained with Wrights Giemsa.

Figure 3. FNA from leg mass (1000x magnification)

Figure 1: FNA from leg mass (200x magnification)

Figure 2: FNA from leg mass (1000x magnification)

Image

Figure 3. FNA from leg mass (1000x magnification)

Figure 1: FNA from leg mass (200x magnification)

Figure 2: FNA from leg mass (1000x magnification)

Image

What is your diagnosis based on the cytologic appearance?

Cytology description: The cytology is highly cellular with good cell preservation and staining, containing round cells amidst small amounts of blood in a light blue proteinaceous background. The round cells have round nuclei of granular chromatin with 1-3 prominent nucleoli and small to moderate amount of light blue cytoplasm often containing a few fine vacuoles and rarely containing a dusting of fine green pigment ( Figure 2 green arrows). They show marked anisokaryosis and anisocytosis (3-fold variation), variable nucleolar size and shape, frequent macronucleoli ( Figure 3 red arrow), variable N:C ratio, occasional binucleation and occasional mitoses are evident ( Figure 3 yellow arrow).

Interpretation: Melanocytic neoplasm, most likely malignant melanoma.

Differentials: Melanocytoma, less likely other round cell neoplasia e.g. histiocytic sarcoma, plasmacytoma, agranular mast cell tumour. A pigmented basilar cell tumour is considered unlikely as no cell cohesion is evident. Histiocytoma is considered unlikely based on the nuclear atypia and prominent nucleoli.

Melanocytic neoplasms are derived from neural crest and include benign melanocytoma, benign melanoacanthoma, and malignant melanoma. Most melanocytic neoplasms arising in the haired skin of dogs are benign melanocytomas whereas most melanocytic neoplasms arising in the nail bed, oral cavity and at mucocutaneous junctions are malignant melanomas (Bolon 1990, Smedley 2011). Cutaneous melanocytomas tend to be heavily pigmented, small, raised, nonulcerated and confined to the dermis. Cutaneous malignant melanomas tend to be poorly pigmented, larger, ulcerated, extend deeper than the dermis and show greater variation in nuclear morphology and more frequent mitoses (Smedley 2022).

Malignant melanomas usually affect dogs older than 6 years. Breeds reported to have increased risk include Schnauzer (miniature, standard and giant), Chow Chow, Shar Pei, Scottish terrier and Doberman Pinscher. Most cases of malignant melanoma involve the nasal bed, oral cavity and mucocutaneous junctions; however, they also occur in haired skin particularly of the head and scrotum (Goldschmidt 2017). Malignant melanomas can grow rapidly, are locally invasive, and can metastasise via lymphatics to regional lymph nodes. They can also spread to more distant sites such as brain, lung, heart, kidney and spleen (Bolon 1990).

Histologic criteria associated with a poorer prognosis in cutaneous melanocytic neoplasms include nuclear atypia (≥20% atypical nuclei e.g. large nuclei, large nucleoli, irregularly shaped nucleoli, multiple nucleoli, eccentric nucleoli), poor pigmentation (<50% of cells pigmented), mitotic count (≥3 mitoses per field area of 2.37mm²), proliferation marker Ki-67 index (≥15% positive cells), size (tumour thickness >0.95cm), extension beyond the dermis and vascular invasion. (Spangler 2006, Smedley 2011)

Of these criteria, only nuclear atypia and degree of pigmentation can be evaluated on cytology smears, along with a subjective assessment of frequency of mitoses. Nuclear atypia and poor pigmentation were evident in the smears from this case supporting malignant melanoma as the most likely diagnosis. Histologic evaluation of the excised mass confirmed malignant melanoma with a high mitotic count (>10 per high power field).

Histologic evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes is recommended even if the lymph nodes are not enlarged as metastatic disease can still be present (Grimes 2017). Cytologic evaluation of lymph node aspirates for metastatic melanoma is problematic as differentiating melanocytes from melanophages (macrophages that contain melanin pigment) and haemosiderophages (macrophages that contain haemosiderin) can be difficult leading to equivocal results. Agreement between routine cytology and histopathology for staging of lymph nodes in dogs with melanocytic neoplasms has been reported as slight to fair, with cytology showing lower sensitivity for detection of metastatic disease (Grimes 2017).

Bolon, B., Calderwood Mays, M. B., & Hall, B. J. (1990). Characteristics of canine melanomas and comparison of histology and DNA ploidy to their biologic behaviour. Veterinary pathology 27(2), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/030098589002700204

Spangler, W. L., & Kass, P. H. (2006). The histologic and epidemiologic bases for prognostic considerations in canine melanocytic neoplasia. Veterinary pathology, 43(2), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.43-2-136

Goldschmidt MH and Goldschmidt KH. Chapter 4 Epithelial and melanocytic tumors of the skin, in Tumors in Domestic Animals. Meuten DJ ed. Page 125-131. Wiley Blackwell 5th edition 2017.

Smedley, R. C., Sebastian, K., & Kiupel, M. (2022). Diagnosis and Prognosis of Canine Melanocytic Neoplasms. Veterinary sciences 9(4), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9040175

Grimes, J. A., Matz, B. M., Christopherson, P. W., Koehler, J. W., Cappelle, K. K., Hlusko, K. C., & Smith, A. (2017). Agreement Between Cytology and Histopathology for Regional Lymph Node Metastasis in Dogs With Melanocytic Neoplasms. Veterinary pathology 54(4), 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985817698209

Smedley, R. C., Spangler, W. L., Esplin, D. G., Kitchell, B. E., Bergman, P. J., Ho, H. Y., Bergin, I. L., & Kiupel, M. (2011). Prognostic markers for canine melanocytic neoplasms: a comparative review of the literature and goals for future investigation. Veterinary pathology, 48(1), 54–72. https://doi. org/10.1177/0300985810390717

Specialist in veterinary oncology

One Cancer Care for Pets

e. Katrina.cheng@onepetcancercare.com

Cutaneous melanoma tends to have less aggressive behaviour compared to oral melanoma, although occasionally they can have aggressive behaviour. Although we know that stage is prognostic for oral melanoma, this is less defined in dogs with cutaneous melanoma. In a recent study looking at post-surgical outcome and prognostic factors in canine malignant melanomas of the haired skin ( Laver et al. 2018), the post-surgery median PFS and median OST of 87 cases were 1,282 days and 1,363 days, respectively. In the dogs that lymph node status was known, only 5 dogs had lymph node metastasis, compared to 37 without lymph node metastasis. The survival time between the two groups did not result in any statistical significance.

If this dog had lymph node metastasis (and confirmed by histopathology), especially if other negative prognostic factors (such as high mitotic count and nuclear atypia) were also present, I would consider the use of immunotherapy, such as the Oncept vaccine. However, as far as I know, there has not been any evidence on the survival benefit of using Oncept in cutaneous melanoma. In Laver et al’s study, the median OST of dogs receiving the Oncept vaccine was not statistically different from patients receiving no adjuvant therapy after surgery. Therefore, the use of Oncept vaccine in this scenario is based on the lack of other systemic treatment, and the evidence of efficacy in oral melanoma.

Oncept melanoma vaccine contains xenogeneic (human) DNA encoding tyrosinase. Tyrosinase is essential for melanin synthesis and overexpressed in tumour cells, but not normal melanocytes. Injection of xenogeneic tyrosinase DNA produces a human antigen that is homologous to canine tyrosinase, but recognised as foreign, therefore elicits an immune response against malignant melanoma cells. Oncept is licensed to use in dogs with stage II or III oral melanoma.

References

Laver T, Feldhaeusser BR, Robat CS, Baez JL, Cronin KL, Buracco P, Annoni M, Regan RC, McMillan SK, Curran KM, Selmic LE, Shiu KB, Clark K, Fagan E, Thamm DH. Post-surgical outcome and prognostic factors in canine malignant melanomas of the haired skin: 87 cases (2003-2015). Can Vet J. 2018 Sep;59(9):981-987. PMID: 30197441; PMCID: PMC6091115.

Professor Bruce Andrew Christie

By Wing Tip WongDr Bruce passed away peacefully surrounded by family on 19 February 2024. As an educator, Bruce was noted for his calm and non-judgemental approach to helping someone discover the gift of learning. His strength lay in supporting and guiding a learner to build a strong foundation in principles which can be utilised to understand why things happen, to maximise a favourable outcome, and to navigate out of a problem. The veterinary community has lost a passionate mentor and a selfless educator. His contributions will live on in those who have learned from and been inspired by him.

Read the full obituary here

Adj Professor Philip Moses BVSc MRCVS Cert SAO MANZCVS FANZCVS AM

By Mandy Burrows, Terry King & Richard MalikPhilip Moses died peacefully on 16 March 2024, surrounded by his family. The veterinary profession has lost an exceptional individual, a colourful, bigger than life personality with an authentic life story. Philip loved and served the veterinary profession. There are probably no continents on earth where his influence on the veterinary profession has not reached. We will remember Philip as a dedicated veterinarian and great friend. The world is a shade darker with his loss.

Read the full obituary here

The International Society of Feline Medicine is the veterinary division of the pioneering cat welfare charity International Cat Care. Trusted by vets and nurses, it provides a worldwide resource on feline health and wellbeing, via the Journal of Feline Medicine of Surgery, by fostering an international community of veterinary professionals with a shared vision of feline welfare, and supporting professional development with practical CPD. Additionally, International Cat Care’s website provides a valuable resource of accurate information delivering what both vets and cats would want owners to know.

Cecilia Villaverde BVSc PhD DACVIM (Nutrition) DECVCN

Sam Taylor BVetMed(Hons)

CertSAM DipECVIMCA MANZCVS FRCVS

C&T No. 6025

Feeding tubes are an excellent tool to manage cats that cannot or will not eat enough, and, depending on the case, can be used both in the hospital and at home. This article looks at important factors to consider when deciding in which cases feeding tubes should be used, when to place them and how to develop a feeding plan.

There is a close relationship between illness and malnutrition. An inadequate nutritional status can predispose to illness via several mechanisms, such as effects on the immune system and damage to the intestinal barrier function. On the other hand, ill animals are more prone to malnutrition due to either reduced food intake and/or increased nutrient and energy requirements. Several studies in veterinary medicine support that patients not meeting their energy requirements can have poorer outcomes,1–3 and that nutritional support can help in these situations. Therefore, efforts should be made to ensure that ill cats receive adequate nutritional support.

Performing a complete nutritional assessment⁴ is important for several reasons, such as deciding on the

best feeding plan (diet, allowance, feeding method) and best route of feeding, and also to identify the patients that will benefit from nutritional support and when to start it. For hospitalised patients, Table 1 shows some of the risk factors that will indicate that the patient requires nutritional support.

Age: kittens and older animals are more prone to malnutrition than young adults. Chronic losses: chronic losses (e.g. vomiting, diarrhoea, polyuria or hypermetabolic state) accelerate the rate of development of: Involuntary weight loss: this is one of the clearer markers of malnutrition, but also denotes that the process is quite advanced.

Days of decreased/absent food intake: the length of anorexia/ hyporexia correlates tightly with malnutrition risk and it precedes weight loss; therefore, this risk factor alone can be enough to start assisted feeding.

Body condition score (BCS): low BCS is related to inadequate energy intake of some duration, as loss of at least 10% of body weight is needed to note a low BCS. While patients that present with a low BCS require more urgent support, a high BCS is not a reason to not provide nutritional support if other risk factors are present. Overweight cats that do not eat are at high risk of hepatic lipidosis,⁵ and it is important to provide assisted feeding in a timely manner to prevent this serious condition.

Muscle condition score (MCS): a low MCS is a nutritional risk factor but is not specific, meaning that low protein and energy intake can contribute

to a low MCS, but many other factors do as well, such as sarcopenia, cachexia or intestinal disease.

Skin and coat: the skin is the largest organ in the body and has a high turnover rate; as such, nutritional deficiencies can show there.⁶

Some laboratory findings can be representative of malnutrition; however, these measurements are late (i.e. the malnutrition is already advanced) and are also not specific or sensitive, so they should be interpreted together with the other factors.

The sooner the better, as suggested by most studies from human and veterinary medicine.1,7,8 It is important to stabilise the patient, i.e. they are well hydrated, haemodynamically stable and there are no acid–base or electrolyte abnormalities.

Oral voluntary intake is the preferred feeding method and there are a variety of strategies that can be used to promote this. If oral intake is not sufficient, and the patient is still anorectic or hyporectic and losing weight, assisted feeding is required. This can be via the enteral or parenteral route; enteral is preferred9,10 as it is safer, cheaper, easier, and more adequate nutritionally. Parenteral feeding (central or peripheral) is not nutritionally complete, therefore it can be used only for the short term.11,12

Syringe/force feeding is not recommended, as it can result in food aversions, aspiration pneumonia or injuries, and is also stressful for the patient. It is also unlikely to meet feeding requirements.

Feeding tubes may be placed to provide fluids and nutrition but also to facilitate long-term medication (e.g. for mycobacteriosis). They can be placed quickly and should be considered proactively; for example, if a patient is being anaesthetised for diagnostic tests but is consuming less than the resting energy requirement (RER) or is predicted to be inappetent after surgery.

The type of feeding tube chosen will depend on the patient, its underlying illness, its temperament and the likely duration of the inappetence. The most commonly placed are naso-oesophageal (NO), nasogastric (NG) and oesophagostomy (O) tubes. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

NO or NG-Tubes (Figure 1), can be used to provide nutrition for up to 5 days and are also useful when a cat

is not a candidate for general anaesthesia. The narrow diameter reduces diet choice to liquid diets and the tube can become obstructed. Crushed medications may also obstruct the tube but liquid medications usually pass easily.

O-Tubes (Figure 2) are well tolerated and larger bore so facilitate the use of many diets and the administration of crushed or liquid medications. However, placement requires general anaesthesia. Common complications are dislodgement, obstruction and stoma site infection.

Other types of feeding tube, such as gastrostomy (G)-Tubes (Figure 3), are less commonly placed but are indicated in cases of oesophageal disease/dysmotility.

Figure 1. Naso-oesophageal or nasogastric tubes are useful for short-term assisted feeding

Figure 1. Naso-oesophageal or nasogastric tubes are useful for short-term assisted feeding

Figure 3. Cat with gastrostomy tube in situ

Step-by-step guides to the placement of NO/NG and O-Tubes are available via the QR codes (below). Placement of an NO/NG-Tube can be facilitated by mild sedation/ anxiolysis (e.g., gabapentin, butorphanol) and placement should be confirmed with radiography and/or capnography and checking for a vacuum or aspiration of acidic stomach content in the case of an NG-Tube.

Placement of O-Tubes can be assessed by radiography, endoscopy or fluoroscopy, and should be checked before each use by checking for negative pressure and injection of 2 mL sterile saline to monitor for coughing or respiratory noise that could suggest endotracheal intubation. G-Tubes are placed surgically or with endoscopic guidance and can be used long-term.

Complications are unusual and generally minor with both NO/NG and O-Tubes. Patient interference can be minimised with cat friendly interactions and environment and using soft collars.

Serious complications include endotracheal intubation and, for O-Tubes, damage to neurovascular structures in the neck resulting in haemorrhage or transient Horner’s syndrome (both rare). Stoma site infection (Figure 4) can occur with O and G-Tubes and is usually managed with antimicrobial dressings and increased cleaning of the area, and avoided with aseptic placement. Cats on chemotherapy or corticosteroids may be more likely to suffer stoma site infections. Complications of G-Tubes can include injury to abdominal viscera, peritonitis, cellulitis, vomiting and metabolic derangements.

Click on the links below to see the videos: youtube.com/watch?v=MEge0fUqotY youtube.com/watch?v=w3K9KWJwsqc

Cats should be offered food under supervision, while the NO/NG feeding tube is in place. Removing Elizabethan collars, or using soft fabric versions, may help to encourage voluntary intake.

If cats are still not eating adequately voluntarily when the NO or NG-Tube has been in place for 5 days, consideration should be given to placing a more mediumterm tube such as an O-Tube. Some cats may be deterred from eating by the presence of the tube; hence, tube removal and ‘testing’ of appetite may be needed, with the tube replaced if voluntary intake remains inadequate. With O-Tubes, cats should be able to eat normally (fabric collars, rather than hard plastic Elizabethan collars can help) and appetite and food intake can be monitored. Sometimes, O-Tubes can be left in place to facilitate medicating the cat, even when its appetite has returned.

G-Tubes cannot be removed for 10–14 days postplacement to allow a seal to form at the gastrostomy site. NO/NG and O-Tubes can be removed with the cat conscious; G-Tube removal is dictated by the type, with some requiring endoscopic removal.

Every cat with a feeding tube should be given a customised feeding plan, which includes diet, allowance, and feeding method.

The diet choice must cover the nutritional requirements of the patient (which depend on its life stage), be well tolerated and include any necessary modifications if the cat has a nutrient-sensitive disease. Other factors that will affect diet choice include availability and cost, palatability (which does not matter with the feeding tube, but can help when stimulating food intake), energy density (the higher the better) and texture (some foods will not be able to fit through certain feeding tubes).

If possible, choosing a convalescence-type diet is indicated, as these have a high energy density, are palatable and are made specifically to be easy to fit through feeding tubes. Some are liquid and some have a slurry consistency. Moreover, these diets are highly digestible, high in good-quality protein, high in fat (which helps with texture, palatability, and energy density) and low in carbohydrates and fibre (as these cats can have insulin resistance and fibre can clog the feeding tube).

For hospitalised patients, the goal is to feed RER (70 × body weight [kg]0.75, kcal/day). Once RER has been reached, and well tolerated, the amount can be

increased if needed; for example, if the patient is losing weight, a kitten is not growing or an underweight patient is not gaining weight. The RER should be calculated using the current weight of the cat, to avoid both over, and underfeeding issues, and afterwards adjustments in 10% intervals can be made to achieve the weight goals of each case.

When the RER is calculated, the daily allowance can be calculated by dividing the RER (kcal/day) by the energy content of the diet (kcal/g or mL) to give the g or mL per day. Using mL is easier as the feedings through the tube are usually done with a syringe. The manufacturer of the diet might need to be contacted for the energy content, or this can be found in product guides in the case of veterinary diets.

Once the feeding tube is in place and the cat has recovered from the anaesthetic or sedation, the tube needs to be tested with a small amount of water (the authors use 3–5 mL/kg body weight, a couple of times) to test that water flows with no obstacles. After that, feedings can be started. It is recommended to start with one-quarter or one-third of the RER, divided over 3–6 meals per day. The longer the period of inappetence and the more severe the disease, the slower the transition should be to prevent refeeding issues.

The food should be warmed to body temperature and placed in the syringe. Before feeding, the tube should be flushed with 5 mL of warm water to ensure there are no obstacles. The meal should be given slowly (at least 10–15 mins per meal). Afterwards, the tube should be flushed with 5–10 mL of warm water to make sure all the food has gone into the cat and to prevent obstruction (Figure 5).

It is important to monitor body weight to adjust the food allowance and achieve weight goals: weight stability

in patients with good or a high BCS, and weight gain (after weight stability is achieved) in growing kittens, underweight cats, or in all cats losing weight with RER. Overweight cats should be kept well stable, and a weight loss plan should be developed and implemented once the patient has fully recovered from the present disease and is eating on its own.

Food can be offered orally once the cat is showing signs of improvement, and the feeding tube can be removed once the cat has been consuming its full RER voluntarily for 3–4 days. If the feeding tube has been in place for a few days (such as for NO/NG-Tubes) and the patient is still not eating enough, a more permanent tube (e.g. O-Tube) should be placed.

body temperature

1. Molina J, Hervera M, Manzanilla EG, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and risk factors for undernutrition in hospitalized dogs. Front Vet Sci 2018; 5. DOI: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00205.

2. Brunetto MA, Gomes MOS, Andre MR, et al. Effects of nutritional support on hospital outcome in dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2010; 20: 224–231.

3. Remillard RL, Darden DE, Michel KE, et al. An investigation of the relationship between caloric intake and outcome in hospitalized dogs. Vet Ther 2001; 2: 301–310.

4. Freeman L, Becvarova I, Cave N, et al. WSAVA nutritional assessment guidelines. J Small Anim Pract 2011; 52: 385–396.

5. Armstrong PJ and Blanchard G. Hepatic lipidosis in cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2009; 39: 599–616.

6. Hensel P. Nutrition and skin diseases in veterinary medicine. Clin Dermatol 2010; 28: 686–693.

7. Will K, Nolte I and Zentek J. Early enteral nutrition in young dogs suffering from haemorrhagic gastroenteritis. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin 2005; 52: 371–376.

8. Mohr AJ, Leisewitz AL, Jacobson LS, et al. Effect of early enteral nutrition on intestinal permeability, intestinal protein loss, and outcome in dogs with severe parvoviral enteritis. J Vet Intern Med 2003; 17: 791–798.

9. Eirmann L and Michel KE. Enteral nutrition

10. In: Silverstein DC, Hopper K (eds). Small animal critical care medicine. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders, 2014, pp 687–690.

11. Chan DL. Nutritional support of the critically ill small animal patient. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020; 50: 1411–1422.

Figure 4: Oesophagostomy tube stoma site infection Figure 5. Prepare flushes for pre- and post-feeding and warm the food to12. Chan DL, Freeman LM. Parenteral nutrition in small animals. In: Chan D (ed). Nutritional management of hospitalized small animals. Chichester: Wiley, 2015, pp 100–116.

13. Pyle SC, Marks SL, Kass PH. Evaluation of complications and prognostic factors associated with administration of total 14. parenteral nutrition in cats: 75 cases (1994– 2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 225: 242–250.

More details on feeding tubes/ placement/management and appetite stimulants can be found in the 2022 ISFM

Consensus Guidelines on Management of the Inappetent Hospitalised Cat here: journals.sagepub.com/doi/ full/10.1177/1098612X221106353, including videos of the techniques, nutritional history forms and tube feeding records to download.

Further reading

C&T No. 5723 Danielle's Top Tip for Feeding Tubes

C&T No. 5845 Horner's Syndrome as a complication of O-Tube Placement

Welcome to Research Roundup, where ISFM brings you summaries of the latest feline research. This issue features interesting articles covering different areas of feline health and welfare including obesity, chronic kidney disease, bicavitary effusions and hypertension. Additionally, the new ISFM/AAFP guidelines on the long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in cats. There are also useful caregiver guides for owners.

1. Clinical Spotlight: 2024 ISFM and AAFP consensus guidelines on the long-term use of NSAIDs in cats

2. Blood pressure in hyperthyroid cats before and after radioiodine treatment

3. Bicavitary effusion in cats: retrospective analysis of signalment, clinical investigations, diagnosis and outcome

4. Information about life expectancy related to obesity is most important to cat owners when deciding whether to act on a veterinarian’s weight loss recommendation

5. Risk factors and implications associated with ultrasound-diagnosed nephrocalcinosis in cats with chronic kidney disease

Read the articles here

1 Feb 2025 - 30 Nov 2026

Enrol now at Super Early Bird rates before 30 Jun 2024 to save AU$827 and automatically be entered in the lucky draw to win AU$1,000 off your course registration fee. cve.edu.au/feline-medicine

Delivered in Partnership with:

Tutor for the Backyard Poultry TimeOnline course

e. r.doneley@uq.edu.au

C&T No. 6026

I was interviewed by the ABC on Friday 12 April regarding an article published in The Guardian: Australia’s back yard chicken owners urged to implement biosecurity measures in case of bird flu outbreak. Paraphrasing the old advertisement, ‘Flu ain’t flu’.

Many people think that Avian Influenza (AI) is just one disease and forget the myriad of strains that exist.

From the Qld Department of Agriculture and Fisheries website:

Highly pathogenic avian influenza - HPAI