Winter 2020

Winter 2020

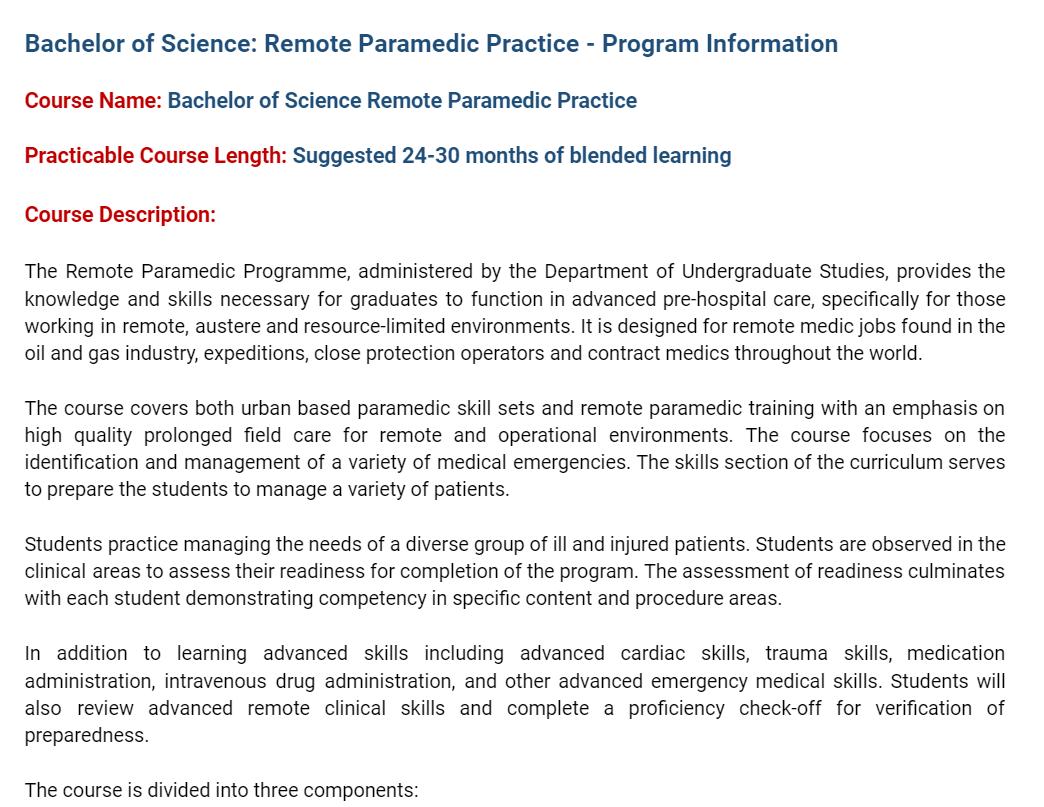

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not -for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

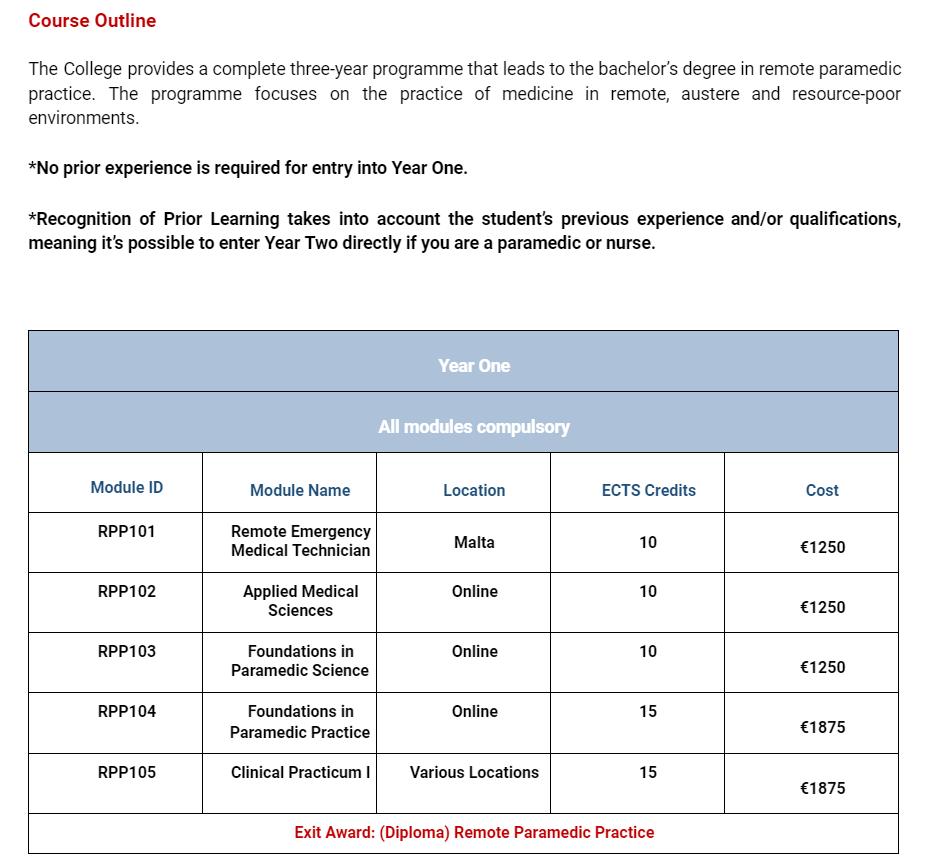

The College has been busy over the autumn semester. We have 25 students enrolled into years one and two of our BSc Remote Paramedic Practice programme. We are looking forward to officially launching our year three of the programme and will begin accepting applications for all three years for an autumn 2021 enrolment.

Additionally, we are almost finished with the accreditation process for the MSc Austere Critical Care. This programme has been in the works for the past three years and we are delighted to see the final stages of the accreditation process come into fruition. We will be accepting applications for the MSc.ACC starting this autumn semester.

Other academic programmes coming down the pipeline include a PGCert in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. This will be a two week programme in Tanzania followed by hands-on clinical placements at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC). We are aiming at the official launch at the end of the summer semester. Keep an eye on our social media for updates.

COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc on all educational institutions throughout the world. On a good note, KCMC is again accepting medical students and CoROM’s paramedic students for clinical placements in their hospital wards. We currently have two CoROM delegates there on placement.

As the new vaccine is rolling out this week in the U.K. and shortly in the U.S., we are hopeful that we will return to the classrooms in Pretty Bay, Malta this March and April. This year has been a challenge for everyone walking this planet. But we have to be flexible and willing to modify our approach to how education is offered. This pandemic has a silver lining in that educational institutions are more willing to do what CoROM has been doing since we started: running a flipped classroom. We continue to enhance our own online offerings as we transition into a more virtual world.

It is with great joy that I am resuming my editorial duties for The Compass. During my one-season hiatus, I discovered I could not stop thinking about how future Compass issues might look, and what valuable content might be found within them. Creating the Trends in Traumatology, Book Review and Test Yourself pieces was not enough to keep my editorial hunger satiated, and I thank Aebhric O’Kelly for letting me have my old job back.

Jason Jarvis 18D NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editorDuring my absence, I began my final classes at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for the Postgraduate Certificate in Infectious Diseases, taught all manner of medical classes throughout the United States, and deployed to Ghana with the UN to help run a predeployment medical course for Ghanaian military doctors and nurses.

Within this issue is a great Where Are They Now? writeup from TJ, the team leader of the aforementioned Ghana training mission.

Nicole Foster’s Public Health piece details the longawaited and much-anticipated COVID-19 vaccine, a topic that is developing on a daily basis and is shaping up to be the world’s central issue of the year 2021.

A summary of CoROM’s Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice program follows the Course Calendar, and I am pleased to announce CoROM will run its first ever training course in Norway, and I remain confident that the College will continue to branch out to all corners of the globe

Test Yourself offers a rather difficult 12-lead ECG, an epinephrine infusion calculation and a case of elephantiasis in Ethiopia.

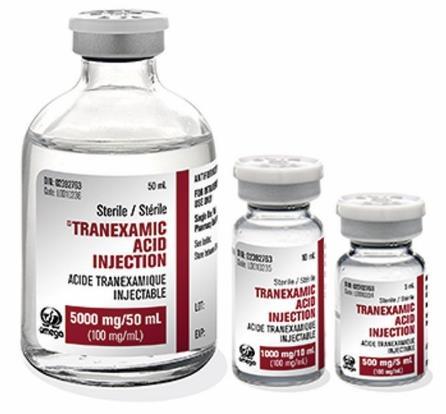

In the Journal Watch section, The British Journal of Anaesthesia has published a remarkable article on the viability of administering tranexamic acid via intramuscular injection, and CoROM’s Academic Board member Dr. Willem Stassen appears as the lead author in an African Journal of Emergency Medicine prehospital randomised control trial.

Trends in Traumatology gives a summary of the Joint Trauma System’s Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) clinical practice guidelines. These guidelines are a superb resource for the austere advanced medical practitioner caring for severe trauma patients, and readers can look forward to the highlights of these guidelines finding their way into the next edition of the CoROM Field Guide, which I hope to begin work on next year.

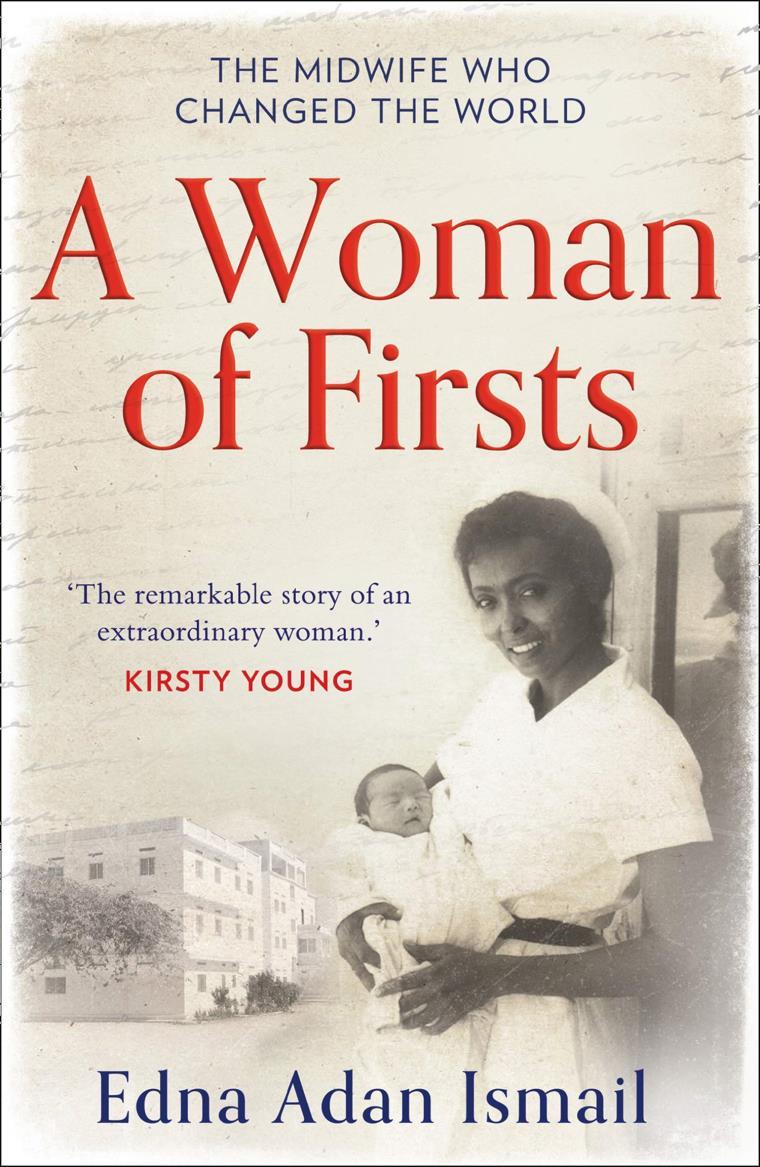

Finally, the Book Review offers a glimpse of the life of Edna Adan Ismail, a midwife and superwoman who hails from Somaliland. My only criticism of A Woman of Firsts is that it should have boasted the subtitle ‘True Grit.’

Most in-house courses are postponed until the end of COVID -19 travel restrictions

NORWAY

TTEMS (closed course) July TBD

MALTA

TTEMS 22-26 March

ATTEMS 29 March-2 April

TTEMS November TBD

ATTEMS November TBD

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON

Suturing Fundamentals 12 April

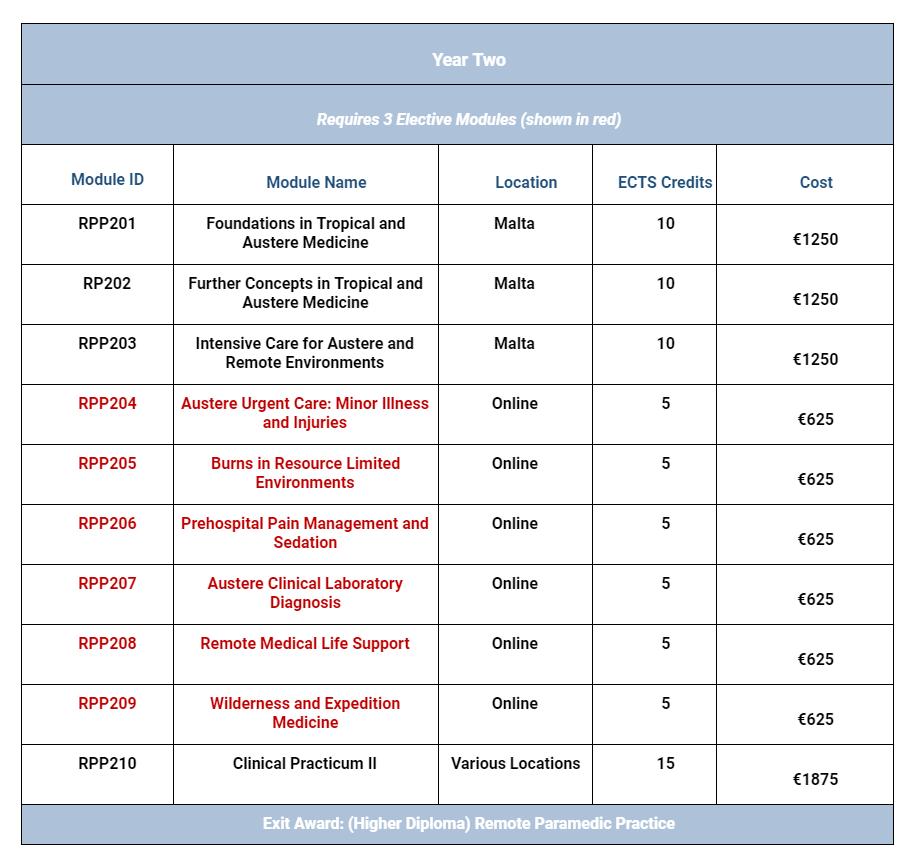

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

Higher Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Cert Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene (in accreditation process)

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

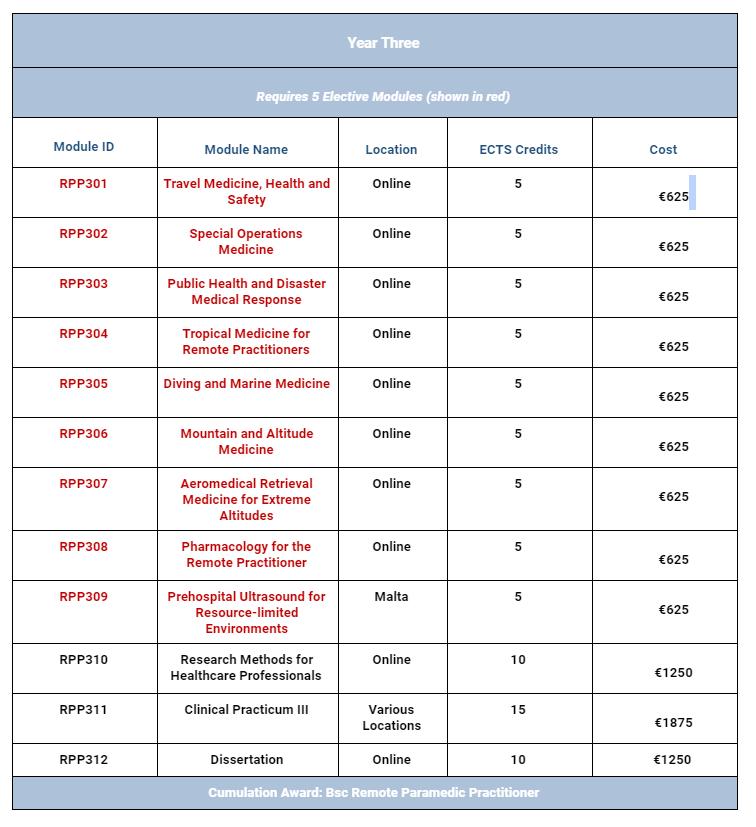

Degree Courses

TANZANIA

TTEMS TBD

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

MSc Austere Critical Care (in accreditation process)

MSc Leadership in Healthcare (in accreditation process)

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitudes

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

REMT Remote Emergency Medical Technician

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org.

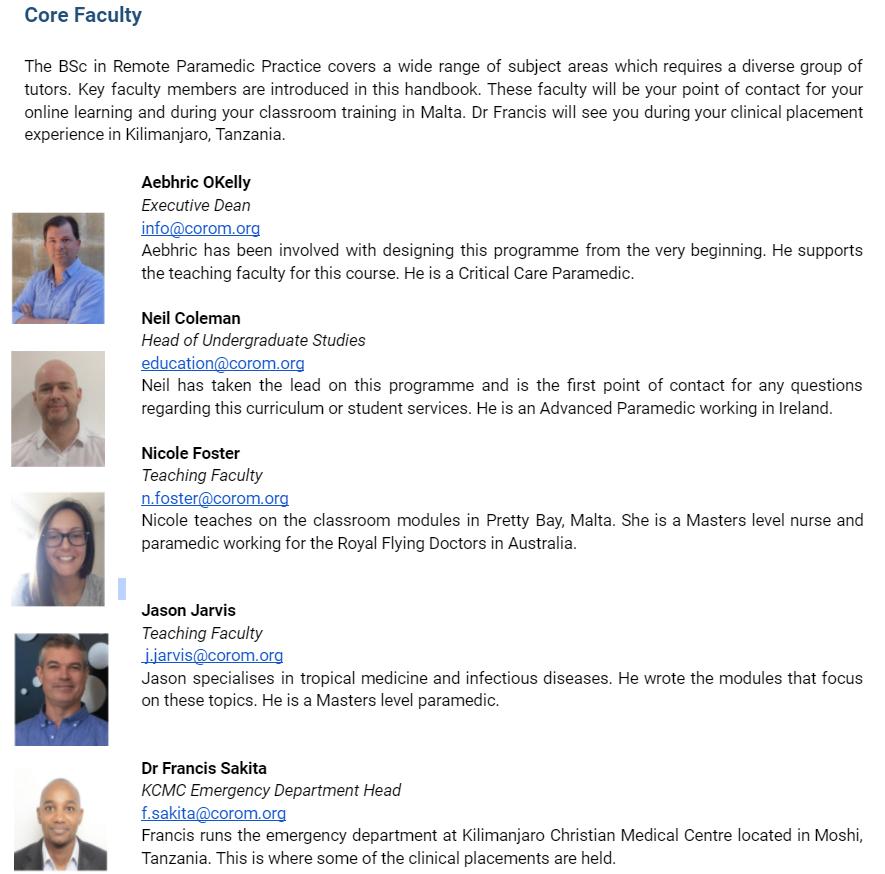

I enrolled in the CoROM Industry paramedic programme in 2016 as I was working as a security contractor close by in North Africa. At the time I’d been an EMT for a bit over 10 years and was ready to give prehospital medicine the attention that I wish I’d been able to dedicate years earlier. Everything about the CoROM paramedic programme was an exact fit for what I needed – a no-frills approach by true industry pioneers, that allowed me the flexibility to work my studies and classes into the ‘all or nothing’ nature of my rotation cycles. The flexibility to entirely neglect studies for weeks on end and then catch up just as intensely when downtime and leave permitted was crucial to my success, along with the occasional reminders and tutor check-ins that helped me get back on task.

Most importantly of all, CoROM gave me an opportunity to network with likeminded people and expand my network in the industry. Finishing the classroom phase I was fortunate to attend surgical rotations in Moldova and ED rotations in Johannesburg where I got to refine my regional nerve blocks and wound care skills and meet several amazing physicians that I am still in touch with to this day. I have since been able to complete the TTEMS and RAMS classes which have put me in great stead for my current career. As a freelance contractor, I’ve been fortunate to gain a whole range of experiences that would not have been possible without both paramedic certification and the uniquely broad scope of industry and remote skills that only CoROM provides. I’m now fortunate to find myself on “a whole bunch” of ad-hoc rosters for short term training, medical support and security opportunities; here are just a few…

While at CoROM, I learnt about Team Rubicon, a volunteer disaster response group that started in the USA, but now has chapters around the globe. I joined them when I immigrated to the USA in 2018, and through TR had the opportunity to start working as a daily rate Wildland Fire Medic working 3 -week stints on the fire line, and a year later, as a Helitack crewman (HECM).

About a year after graduating from CoROM, I landed a spot with an international organization as a Tactical Paramedic in their rapid response capacity. It’s an on-call gig that sees me doing short overseas deployments throughout the year in the middle east and more often these days, Africa. The role is predominantly in training and quality assurance, visiting remote sites to work with host government security forces and ordnance teams to stress test their casualty evacuation procedures. Through my hands, CoROM material has impacted the International Mine Action Standards and will no doubt reduce preventable deaths in sector by ensuring our team medics are ready to perform the best (and only) Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) and transport available in many of these countries.

2018 bought me the opportunity of a lifetime, to work with Toyota Japan on a transcontinental 4WD expedition across Africa over 8-weeks. While I was hired as a deputy TL, it was clear that being able to double hat as a Medic had been a consideration in my selection. That cost saving strategy seems to have become the de facto industry standard of recent years. While we were accompanied by a team physician and a separate contract for an ambulance, it was quickly apparent that the separate medical entities had very different ideas of how to do business. My CoROM knowledge became the foundation for both our force preventative health plan, CASEVAC and prolonged field care/buddy transfusion contingencies. Something we would surely need if we had a serious accident; often 4 or more hours from additional medical care. In the end, it was a great ride with a couple of strains, one allergic reaction secondary to a bite, a suspected malaria case, and a few cases of constipation from those delicate GI tracts on their first overseas visit. Yeah constipation!! Not the end of the spectrum I had been anticipating.

The response to the major category 5 Hurricane Dorian in the Caribbean in 2019 saw relief organizations and private security companies mobilize in support of a range of humanitarian and industrial needs. Before the storm even hit, phones were ringing to identify medics with their own gear who could mobilize on short notice. Less than 12 hours later we were taking off from Florida in charter aircraft, destination status unknown. Our only instructions were to prepare to be fully self-sustaining for at least 7 days including food, water, and shelter; resupply was unlikely. We did not know if the water was drinkable, the air was breathable or if we’d be sleeping in standing water at the remote industrial site where we were headed. Hammocks, dry bags, baby formula and soccer balls were the order of the day. On that job I treated several team-mates for heat exhaustion, some minor wound infections, and was able to save the company three expensive CASEVAC flights to the States. We suffered one heat stroke patient, a dental emergency and an eye injury from an unknown industrial chemical splash (thanks to my RAMS optho kit). A strong lesson learnt in how much telemedicine can be your friend. While I may not have the brains, my hands can do the work of someone else far, far away who does.

In May 2020, following a police death in custody, major peaceful demonstrations broke out across the Unites States and Europe, many of which degraded into pockets of alcohol-fueled rioting and looting in the evenings. Freedom of the press being critical to the maintenance of a healthy democracy, private security contractors and medics filled the emergency services void in many contested areas. I was picked up for a contract and worked the first seven days in Minneapolis for mainstream media outlets on both sides of the spectrum, and eventually for the city council members whom received threats of violence and intimidation for carrying out their duly elected responsibilities of public office. In that seven days, I treated innumerable bumps, bruises strains and eye injuries (OC/CS). I was able to use remote care techniques like a tuning folk and Ottawa ankle exams to rule out fractures and keep the team moving.

Most recently, I used my CoROM -acquired skills to treat the most important patient of all; myself. I contracted coronavirus in West Africa, and it hit me much harder than expected, given that I have none of the known preconditions. With a pulse oximetry of 55% we knew a visit to the local hospital was necessary. After waiting 12 hours at the nearest ‘hospital’ without any news from a doctor, I was informed I’d be transferred to their COVID ward. Fearing an increased viral load, my team and I decided that hut care at the hotel was my best chance, taking my CXR and lab results on the way out. Being stuck in West Africa and becoming a team liability is not something any of us ever want or imagine. I was grateful for the information I had learned earlier in the year being involved in the planning of a Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) facility in Bangladesh. I had no idea at the time, I would need that information to treat myself and protect my team. Being able to contribute to my own care was crucial to both our mission success and my eventual recovery and psychological well-being. Skills and tools I learnt from CoROM made that treatment possible not to mention telemed with ‘smarter people’ that I knew and had kept in touch with from the CoROM class. At times, we all stand on the shoulders of giants.

Where to from here? I hope to undertake some academic study when time permits, and am developing myself further in remote field dentistry, physiotherapy, more regional nerve blocks and ultrasound. Yes, one day I will master that pesky little torch. When I’m home between jobs, I volunteer on the local country 911 ambulance, which is a pleasant change of pace, testing my knowledge of chronic disease. I’m regularly able to practice physical exam skills and diagnostics that many of my colleagues missed out on in their US -based NRP programme.

Enrolling at CoROM really has changed (and maybe literally saved) my life. Next to marrying my wife, it was the best decision I think I have made in a long time before or since. It has bought me not just new skills and knowledge, but a new career, a new way of life and some good friends to share it with.

TJ’s students in South Sudan performing a blood autotransfusion

TJ’s students in South Sudan performing a blood autotransfusion

Nicole Foster Nicole teaches on the classroom modules in Pretty Bay, Malta. She is a critical care paramedic with a masters in public health and tropical medicine and works as an exploration paramedic in remote Australia.

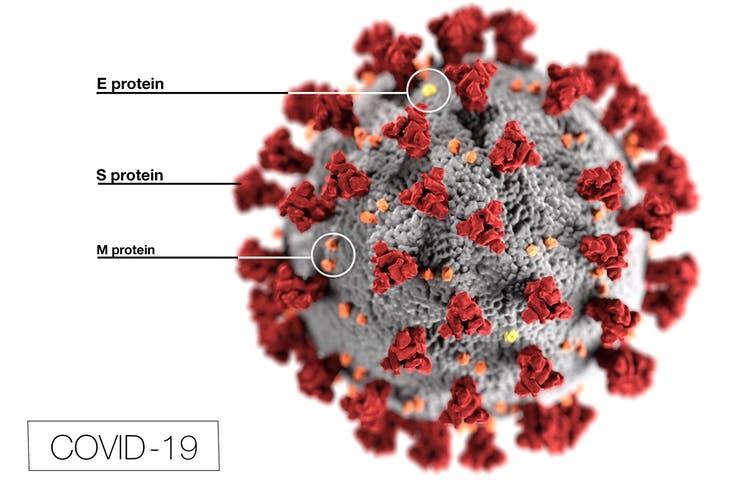

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS -CoV-2) is responsible for the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID -19) pandemic. There has been a lot of press in the past several weeks concerning the current COVID-19 vaccine trial data that has been released. Over 65 vaccine candidates are in development, with over 50 progressing to phase 3 clinical trials. Research and development for most medications can take years and even decades to come to fruition – and we have witnessed the creation of a new vaccine in under six months. This has created some trepidation about the safety and efficacy of these vaccines, and time will only tell if the new technologies utilised will produce a safe vaccine for all.

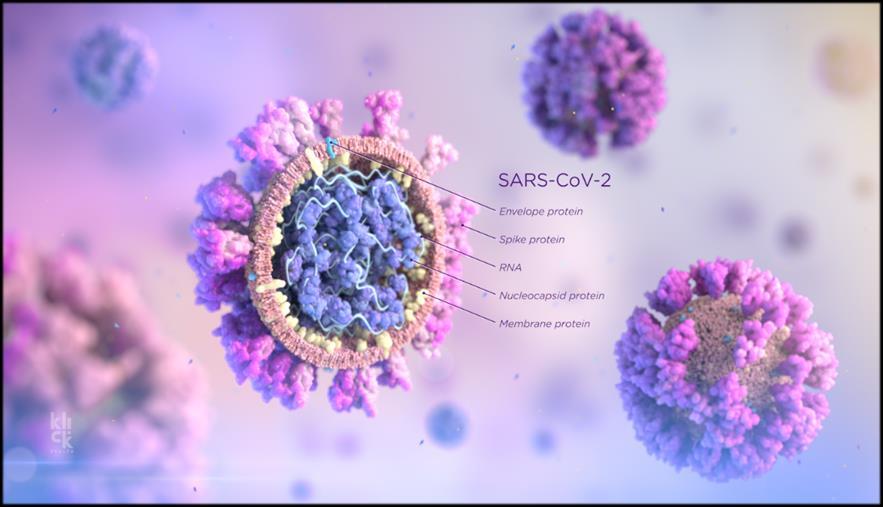

Vaccine development is focusing on the structural makeup of the virus, in particular the glycosylated S proteins (spike proteins) that cover the surface of SARS -CoV-2. These spike proteins bind to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), mediating viral cell entry. Once within the cell, the viral RNA genetic sequence is translated, replicated, and transcribed within the cell, before being packaged up and released to seek more hosts. Although not completely certain, scientists believe that the spike protein triggers an immune response within humans and the aim of current vaccines in development is to safely introduce these spike proteins into the body in a form that stimulates an immune response for future viral loads.

There are two types of delivery systems that have been produced for the SARS -CoV-2 vaccine –messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and S spike protein vaccines.

Big pharmaceutical names such as Pfizer and Moderna have developed an mRNA vaccine. RNA vaccines work by introducing a synthetic mRNA particle, which acts as an instruction manual for cells and tells them what to build. Scientists have placed a blueprint of the spike protein (not the whole virus structure) into a mRNA molecule, and when delivered into a human host, will build a singular virus protein (the S spike protein). The immune system is triggered and begins to produce antibodies and T cells against any presence of similar spike proteins in the body.

The Pfizer mRNA vaccine require cold chain management at -75 degrees Celsius and must be used within five days once removed from this temperature into refrigeration. Moderna’s storage requirement is -20 degrees Celsius and used within 30 days at refrigeration temperatures. Both vaccines at this stage require 2 doses spaced several weeks apart, creating further issue in countries that cannot maintain the frozen cold chain storage.

AstraZeneca and Johnson and Johnson (amongst many others) are using ‘nonreplicating ChAdOx1 vector vaccine.’ This involves placing the blueprint for the spike protein into a harmless / disabled viral strain (ChAdOx1), creating a recombinant virus which, when delivered into the human body, creates SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and therefore triggers the immune response to that protein spike, and therefore, to COVID-19.

The S spike protein vaccines do not require freezer cold chain requirements and can be kept at refrigeration temperatures between 2 – 8 degrees Celsius for at least six months. AstraZeneca looks to be the most viable option for resource poor countries due to the standard cold chain requirements and has already pledged 300 million doses to GAVI, the vaccine alliance and the world health organisation to distribute to 92 developing countries. It is unknown what the dosing schedule is – both a half dose followed by a full dose and two full doses (one month a part) were trialled, with varying efficacy.

Resource poor environments that struggle to maintain basic western cold chain management standards are going to be left behind with the new vaccines – it is essential that in order to create an immunity level above 70% in any given population to begin to decrease the impact of this pandemic, countries will need to improve their accessibility and logistics in order to provide coverage over many points within a country over many days – otherwise we will see a huge disparity between those that can provide herd immunity through vaccination and those that can’t.

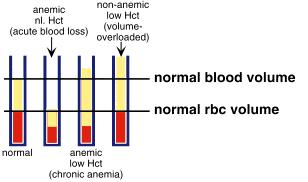

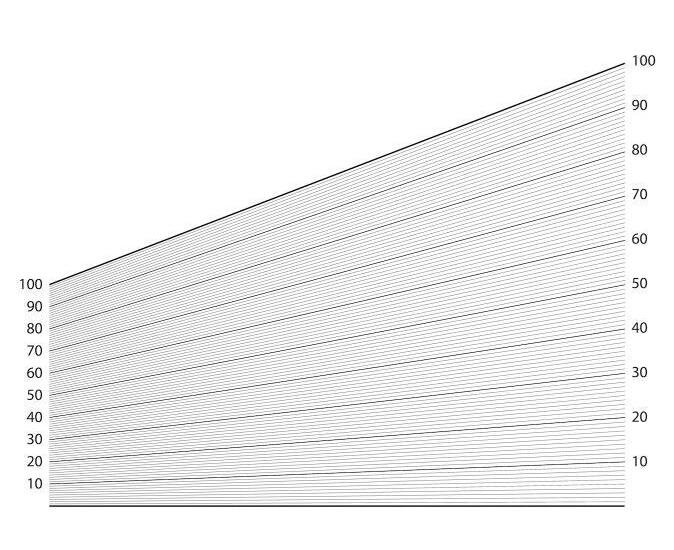

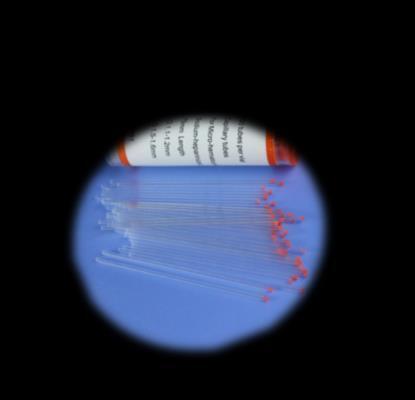

Each edition of the Compass will feature a new skill explaining improvisation of a particular medical task or device. This issue will cover measurement of haematocrit (Hct).

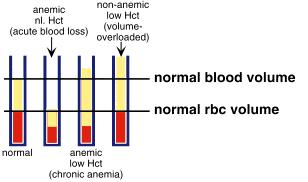

Knowing a casualty’s haematocrit can be quite useful for the remote medical practitioner as it will reveal the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood. It should be in your austere clinical laboratory kit to supplement your diagnostic capabilities. If you have an unwell casualty with signs of shock but without obvious signs of injury, this skill may help rule out a massive internal haemorrhage.

Causes for an elevated Hct (polycythaemia)

- Drop in blood plasma levels

- Dehydration

- A danger sign in dengue fever for an increased risk of dengue shock syndrome

- During climbs to high elevation, there is a lower oxygen supply in the air and thus haematocrit levels may increase over time

Causes for a drop in haematocrit (anaemia)

- Massive haemorrhage

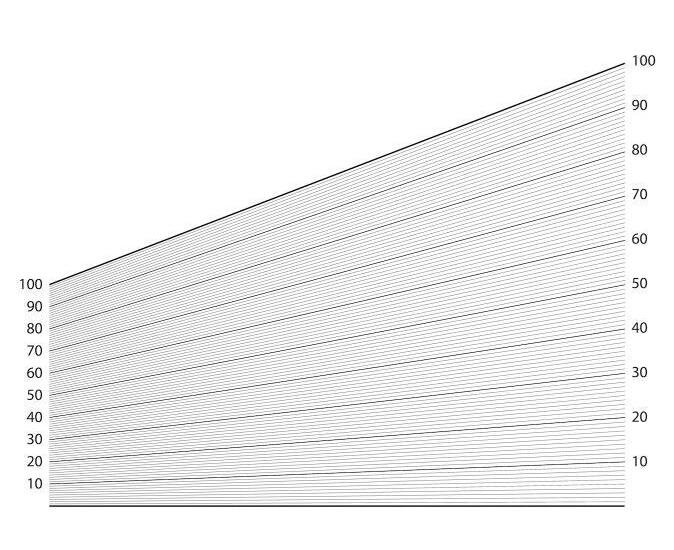

Required items

- Heparinised capillary tubes

- Capillary tube sealant

- Cardboard disk or similar option

- String

- Duct tape

- CoROM 2nd edition Field Guide pages 308 and 309

anaemic, normal Hct with acute loss

non-anaemic, low Hct with overhydration

normal blood volume

normal volume of red bl

normal

a H aem ato crit cap illary tu b e

b Plasm a (w ater an d electrolytes)

c W h ite b lo od cells an d p la telets

d Eryth ro cytes (red b lo od c ells)

e Sealin g p u tty

f Air

b f

References

Boneu B, Fernandez F. The role of the hematocrit in bleeding. Transfus Med Rev. 1987 Dec;1(3):182-5

Paperfuge: An ultra-low cost, hand-powered centrifuge inspired by the mechanics of a whirligig toy. M Bhamla et al. bioRxiv 072207; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/072207

During a recent UN-sponsored field medicine course in Ghana, I needed to “get smart” on the latest Damage Control Resuscitation Clinical Practice Guidelines (DCR CPGs) in order to present the topic to a student cohort of physicians and nurses.

As a former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic laboring under the expectation of providing physician-quality medical acumen in the field without the benefit of four years of medical school (or a residency), getting smart on innumerable medical subjects has been my stock -in-trade for over two decades.

Jason Jarvis 18D NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

Jason Jarvis 18D NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

Tropical medicine phenom Dr. Glenn Geelhoed, one of my most cherished mentors (whose book “Ebenezer” was recently featured in The Compass) said it best: it’s not that medicine is hard, there’s just so much to know.

In the case of my Ghanaian dilemma, I turned to the Joint Trauma System’s 2019 CPGs on DCR. To the delight (or consternation) of healthcare practitioners worldwide, the body of knowledge contained within medical subspecialties is growing exponentially in size – with no end in sight - and Damage Control Resuscitation is certainly not missing that boat. Within the DCR CPG I discovered many technical terms and acronyms perhaps unfamiliar to practitioners working outside the disciplines of surgery, hematology, or emergency medicine.

In this newsletter’s Trends in Traumatology I will present the background, definitions and some pearls contained within the JTS DCR CPG (is that enough acronyms?), beginning with an excerpt from the article background*

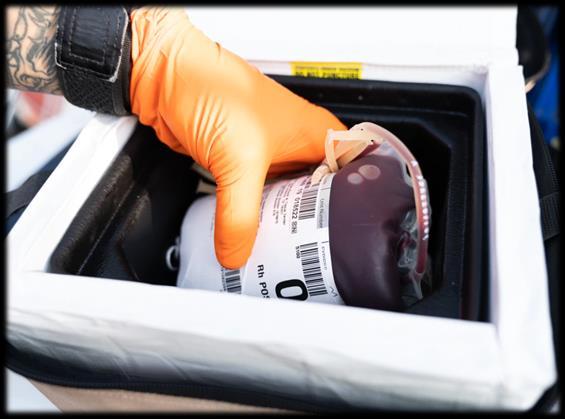

“Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) is generally accepted as a complementary strategy usually paired with Damage Control Surgery (DCS), which focuses surgical interventions to those which address life-threatening injuries and delays all other surgical care until metabolic and physiologic derangements have been treated. Recognizing that this approach saved lives, DCR was developed to work synergistically with DCS and prioritize non -surgical interventions which may reduce morbidity and mortality from trauma and hemorrhage.

The major principle of DCR is to restore hemostasis, prevent or mitigate the development of tissue hypoxia, oxygen debt and burden of shock, as well as coagulopathy. This amounts to preventing ‘blood failure,’ specifically with a goal of restoring functionality (improving oxygen delivery and tissue perfusion, reducing acidosis, preventing fibrinolysis, reducing coagulopathy, protecting the epithelium, and reducing platelet dysfunction). This is best accomplished through aggressive hemorrhage control and a blood product -based resuscitation, which restores tissue oxygenation, avoids platelet and coagulation factor dilution, and also replaces lost hemostatic potential.

DCR is most effective when resuscitation replaces lost blood with whole blood, whether ideally transfused as units of whole blood (WB), or blood product components transfused in a ratio approximating whole blood (i.e. 1:1:1 ratio of FFP:Plt:RBC).

Additional goals of DCR are avoidance or limiting use of crystalloids to avoid dilutional coagulopathy, selective use of hypotensive resuscitation (SBP of 100 or 110 if TBI is suspected) until surgical control is achieved, correction of coagulopathy and acidosis, maintenance of normothermia, empiric administration of tranexamic acid in appropriate patient populations, and expeditious evacuation to damage control and definitive surgical capabilities.”

*Citations omitted. For the full text refer to: https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Damage_Control_Resuscitation_12_Jul_2019_ID18.pdf.

Pearls

Predicting the need for a massive transfusion (MT)

“Robust pre-hospital data are lacking, but a number of risk factors predict the need for MT support in trauma. In a patient with serious injuries, the presence of 3 of the 4 features below indicates a 70% predicted risk of MT and 85% if all 4 are present:

Systolic blood pressure <100mm Hg

Heart rate > 100 bpm

Hematocrit <32%

pH <7.25

Other risk factors associated with MT or at least need for aggressive resuscitation.

Injury pattern (above-the-knee traumatic amputation especially if pelvic injury is present, multi-amputation, clinically-obvious penetrating injury to chest or abdomen

>2 regions positive on FAST scan

Lactate concentration on admission >2.5

Admission INR 1.5 or more

BD >6 mEq/L

Low haematocrit is a predictor of the need for a massive transfusion

“In 2014 the U.S. Army Rangers developed and instituted the ROLO program. Low titer Rangers were identified as a screened donor pool serving as immediate WBB capability (approximately 2/3 of the group O Ranger population is low titer, generally accepted as having anti-A and anti-B levels less than 1:256 concentration). Every Ranger is trained to set up and administer a Fresh Whole Blood buddy transfusion. This program represents a success story of leadership and since 2015 every Ranger task force has deployed with a functional ROLO program. This model is currently being broadened to other prehospital communities.”

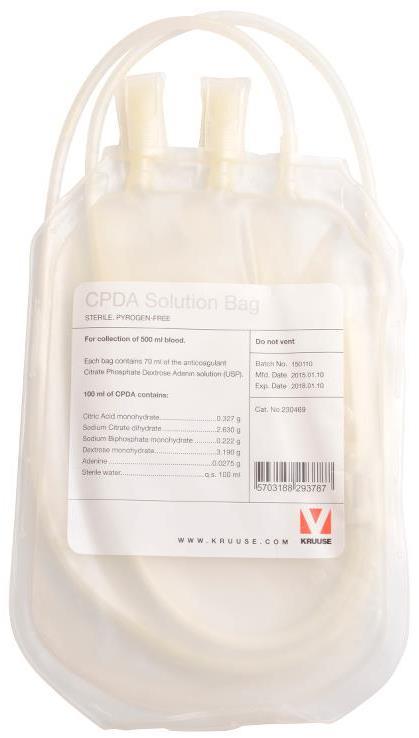

Available data suggest that CWB will provide robust platelet hemostatic function during the first 2 weeks of storage. When using anticoagulants such as CPD and CPD -A, function is moderately reduced during the remaining shelf life (21 days for CPD WB and 35 days for CPDA-1 WB), but it should be noted that platelet function remains and that WB plasma hemostatic function is comparable to that of liquid plasma. Throughout its shelf life, CWB remains a relatively hemostatic product compared to RBCs and plasma alone.”

“[The] survival benefit associated with TXA supports its use in conjunction with damage control resuscitation following combat injury. This association is most prominent in those requiring massive transfusion. In casualties at high risk of hemorrhagic shock, TXA reduces mortality IF GIVEN WITHIN 3 HOURS of injury, optimal use of TXA requires that it be given as soon as possible when indicated rather than suggesting that TXA administration any time within 3 hours after injury is acceptable.” [1 st dose: 1 gram IV/IO over 10 minutes, 2 nd dose: 1 gram over the next 8 hours]

“The ideal application of REBOA in the combat environment is evolving, but the technique, when used appropriately, has the potential to significantly improve outcomes from non -compressible truncal hemorrhage.”

“Normal saline and PlasmaLyte A are the only crystalloid solutions compatible with blood products.”

“The use of rFVIIa is no longer recommended in most trauma patients since it has not been shown to reduce mortality and may increase the risk of adverse events.”

“One gram of calcium (30ml of 10% calcium gluconate or 10ml of 10% calcium chloride) IV/IO should be given to patients in hemorrhagic shock during or immediately after transfusion of the first unit of blood product and with ongoing resuscitation after every 4 units of blood products [to avoid citrate toxicity].”

“Note that hypomagnesemia is also common in trauma patients and is worsened by citrate -containing blood products.”

Colloidal resuscitation fluids

“The use of hydroxyethyl starch ( Hextend, Hespan) as a resuscitation fluid is NO LONGER RECOMMENDED and has been removed from the guideline.”

Pediatric considerations: Blood transfusion

“A MT in pediatrics has been defined as 40 +ml/kg of blood products in 24 hours. The circulating blood volume in children is approximately 60-80ml/kg. Children are at high risk of developing hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, hypothermia and hyperkalemia during MTs. For children under a weight of 30kg, transfusions of RBC units, FFP, or apheresis platelets should be given in ‘units’ of 10-15ml/kg.”

Pediatric considerations: TXA

“The UK Royal Society of Pediatrics and Child Health has recommended a loading dose of 15mg/kg (up to 1g) followed by 2mg/kg/ hr over 8 hours (or up to 1g over 8 hours).”

Definitions

CPD: Citrate Phosphate Dextrose

CPDA-1: Citrate Phosphate Dextrose Adenine

CSP: Cold-Stored Platelets

CSP-PAS: Cold-Stored Platelets in Platelet Additive Solution

CWB: Cold-Stored Whole Blood

DCR: Damage Control Resuscitation

DCS: Damage Control Surgery

FDP: Freeze-Dried Plasma, a.k.a., lyophilized plasma

FFP: Fresh Frozen Plasma

FWB: Fresh Whole Blood

LIFO: Last -In, First -Out – a reference to using the freshest whole blood available

LTOWB: Low Titer Group O Whole Blood

MT: Massive transfusion (10 or more units of RBCs and/or whole blood in 24 hours)

TSWB: Type Specific Whole Blood

TTDs: Transfusion-Transmitted Diseases

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former US Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

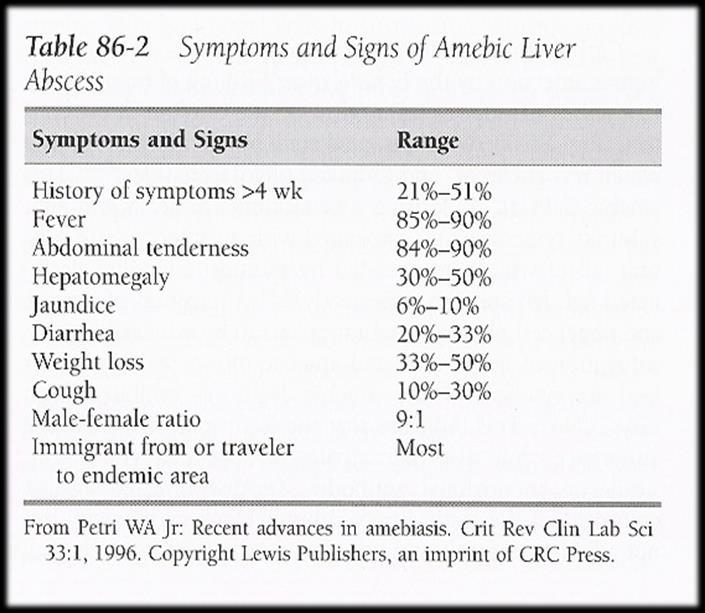

HPI:

A 74-year-old Indian male arrived in the U.S. one month before presenting to the Emergency Department. He described fever to 38.5C for ten days and intermittent right upper quadrant abdominal pain for “years”. Other than visiting family in the U.S., he spent his entire life in urban southern India. He had seen a U.S. physician a week before and had one negative set of malaria thin and thick smears.

In the ED he was well appearing, but slightly febrile with moderate RUQ tenderness. His laboratory testing was notable for slight liver function test abnormalities and RUQ ultrasound showed a 10 by 6 cm abscess.

Differential diagnosis for a hepatic abscess:

Hepatic Tumor, Pyogenic Liver Abscess, Echinococcal Cyst, or Amebic Liver Abscess

Hepatic tumor:

• Malignant tumors more common than benign lesions.

• Metastatic lesions are most common hepatic neoplasm in the western countries.

• Hepatitis B / C and liver cirrhosis are major causes of hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide.

• Ultrasound is inferior to CT imaging for most hepatic tumors.

Pyogenic abscess:

• Less common worldwide than amebic abscess.

• Fever, focal abdominal tenderness, hepatomegaly, and elevated alkaline phosphatase usually present.

• Patients more commonly present with jaundice, sepsis, and a palpable mass.

• Typically, polymicrobial frequently from a biliary source.

• Treatment involves percutaneaous drainage with a catheter or needle. More successfully than surgical drainage (70% for PC, 65% for abx alone and 61% for surgical drainage. 1

• Diabetes is the most frequently associated disease.

• 95% involve the right lobe of the liver.

Echinococcal cyst:

• Infection with the cystic / larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, a 2-7 mm dog tapeworm.

• Frequently asymptomatic and most discovered coincidently.

• RUQ pain / tenderness, fever, jaundice, urticaria, N/V when symptomatic.

• Majority involve right lobe of the liver (77%).

Amebic liver abscess:

• A parasitic infection caused by the protozoa Entamoeba histolytica

• This parasite is fecal oral spread and causes amebiasis, an intestinal infection that is also called amebic dysentery. After an infection has occurred, the parasite may be carried by the bloodstream from the intestines to the liver.

Ultrasound appearance did not support Hepatic tumor or Echinococcal Cyst.

Can you clinically separate ALA from Pyogenic abscess?

• “It was not possible to differentiate between amoebic and pyogenic liver abscess on clinical grounds, routine investigations and imaging techniques.” 2

• “Aspiration of pus, was most helpful in differentiating the two types of abscesses.” 2

• “Serological testing for E. histolytica was highly specific and sensitive for amoebic liver abscess.” 2

• “In our setting, amebic abscess is more prevalent and, in most circumstances, can be identified and managed without percutaneous aspiration.” 3

Serology:

• Serum antigen detection has a sensitivity of 95%.

• Stool microscopy only 10 to 40% sensitive.

Treatment:

• Metronidazole 500 mg 3 - 4 doses a day x 10 days.

• Since the parasite can persist in the intestine in 40 to 60% of patients also need treatment with a “luminal agent” to clear E. histolytica cysts.

• Paromomycin 500 mg tid x 7 days.

Follow Up:

• Feeling better, fever resolved, and lab abnormalities improving.

• Repeat hepatic ultrasound on day 13 essentially unchanged.

• Ultrasound resolution may take 10 to 300 days. 4

1 Pyogenic liver abscess. Changes in etiology, management, and outcome. Medicine 1996 Mar;75(2):99 -113. Mortality rate between 6 and 20%, depending on study.

2 Ahsan T, et all. Amoebic versus pyogenic liver abscess. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002 Nov;52(11):497 -501

3 Lodhi S, Et All. Features distinguishing amoebic from pyogenic liver abscess: a review of 577 adult cases. Trop Med Int Health. 2004 Jun;9(6):718-23.

4 Simjee AE. Clin Radiol. 1985 Jan;36(1):61-8.

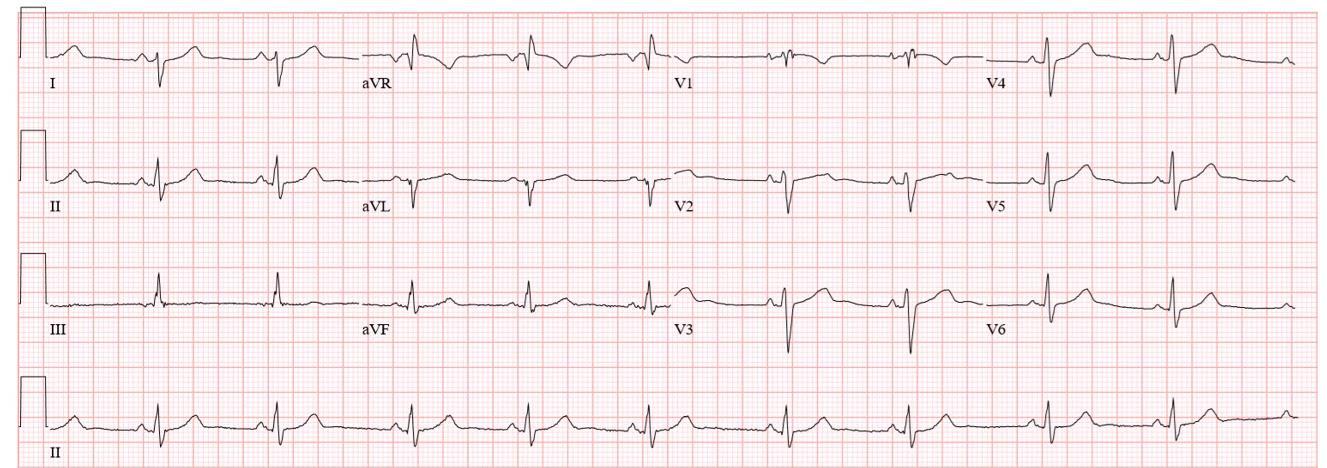

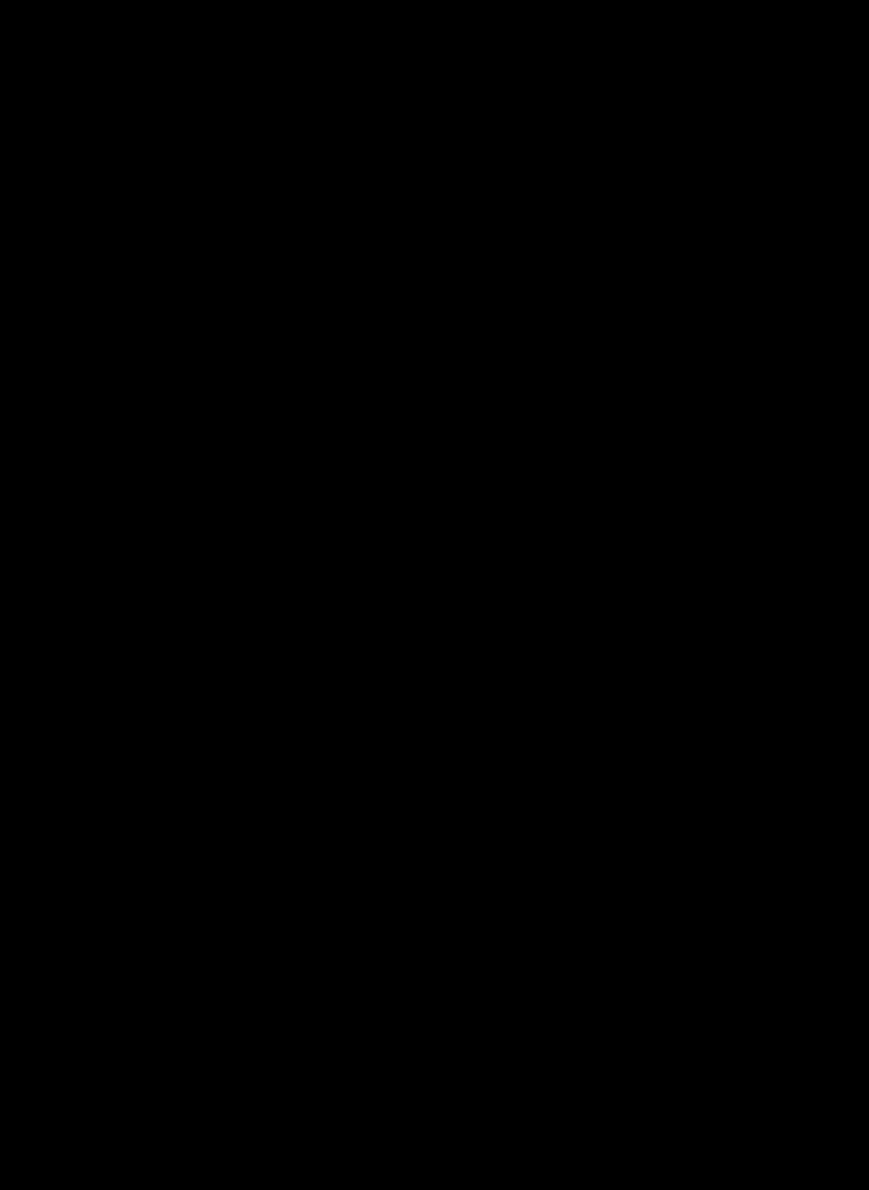

During your clinical rotation through Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Ghana, a 55year-old female patient with dyspnea is admitted and you are asked to review the patient’s 12-lead. What working diagnosis could you form based solely upon this ECG?

A. COPD

B. Pneumonia

C. Tuberculosis

D. Spontaneous pneumothorax

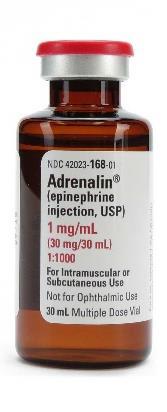

Following the successful resuscitation of an 80kilogram scientist who suffered a sudden cardiac arrest at an Antarctic research station, you note that his systolic blood pressure is now 78 mm Hg. A 2 -liter intravenous saline bolus has failed to raise the systolic pressure over 90 mm Hg, so you decide to apply a vasopressor infusion to the problem. Your colleague has mistakenly added 6mg of epinephrine 1:1000 to a 1-liter bag of normal saline, leaving the clinic with no remaining epinephrine. Using a 10 drop/mL IV giving set, at what rate will you infuse the drug to achieve a dosing of 0.4 micrograms per kilogram per minute?

You have set up a remote clinic in Yebelo, Ethiopia and have seen several male adult patients suffering from bilateral swelling of the lower limbs (pictured). None of the patients exhibit hydrocele or chyluria, and their leukocyte differentials are normal. You suspect these men are suffering from:

A. Leprosy

B. Podoconiosis

C. Tertiary syphilis

D. Lymphatic filariasis

Answers will appear in the Spring 2021

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: Pulmonary embolism

Clinical calculation: 18 drops/minute

Clinical case: A. Dengue virus

Medical References (TJ’s picks)

Gear

available at amazon.com

Deployed medical practitioners are expected to have everything, everywhere, all the time. While this is never feasible, that is the expectation, and the practitioner that comes closest to that utopian ideal will stand out as a “good doc” in the eyes of his or her patients and peers.

Over the years, I have built a lot of rapport in the simple task of being able to dispense oral medications on the fly, and the key to that success is the utilization of Folca pill cases. These hardy little containers are excellent stand-ins for the less-practical option of lugging around pills in their original containers.

To the right is pictured my current medical rucksack oral medications loadout. At higher echelons of care, i.e., the truck and the ‘house,’ there will be found greater quantities of these and other oral medications.

-Jason Jarvis

-Jason Jarvis

British Journal of Anaesthesia

30 September, 2020.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.058

Grassin-Delyle, et al.

Intramuscular TXA was well tolerated with only mild injection site reactions. A two -compartment open model with first -order absorption and elimination best described the data. For a 70-kg patient, aged 44 yr without signs of shock, the population estimates were 1.94 h−1 for i.m. absorption constant, 0.77 for i.m. bioavailability, 7.1 L h−1 for elimination clearance, 11.7 L h−1 for intercompartmental clearance, 16.1 L volume of central compartment, and 9.4 L volume of the peripheral compartment. The time to reach therapeutic concentrations (5 or 10 mg L −1) after a single intramuscular TXA 1 g injection are 4 or 11 min, with the time above these concentrations being 10 or 5.6 h, respectively.

The Lancet – Infectious Diseases

12 October, 2020.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473

Tillett, et al.

-3099(20)30764-7

Genetic discordance of the two SARSCoV-2 specimens was greater than could be accounted for by short -term in vivo evolution. These findings suggest that the patient was infected by SARS-CoV-2 on two separate occasions by a genetically distinct virus. Thus, previous exposure to SARSCoV-2 might not guarantee total immunity in all cases. All individuals, whether previously diagnosed with COVID -19 or not, should take identical precautions to avoid infection with SARS-CoV-2. The implications of reinfections could be relevant for vaccine development and application.

African Journal of Emergency Medicine

6 March, 2019.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2019.02.002. Stassen, et

al.

The incidence of cardiovascular disease and STEMI is on the rise in sub -Saharan Africa. Timely treatment is essential to reduce mortality. Internationally, prehospital 12 lead ECG telemetry has been proposed to reduce time to reperfusion. Its value in South Africa has not been established. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of prehospital 12 lead ECG telemetry on the PCI -times of STEMI patients in South Africa. A multicentre randomised controlled trial was attempted among adult patients with prehospital 12 lead ECG evidence of STEMI. Due to poor enrolment and small sample sizes, meaningful analyses could not be made. The challenges and lessons learnt from this attempt at Africa's first prehospital RCT are discussed. Challenges associated with conducting this RCT related to the healthcare landscape, resources, training of paramedics, rollout and randomisation, technology, consent and research culture. High quality evidence to guide prehospital emergency care practice is lacking both in Africa and the rest of the world. This is likely due to the difficulties with performing prehospital clinical trials. Every trial will be unique to the test intervention and setting of each study, but by considering some of the challenges and lessons learnt in the attempt at this trial, future studies might experience less difficulty. This may lead to a stronger evidence - base for prehospital emergency care.

Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research

12 October, 2020.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20207851

Resende, et al.

The neutrophil is an important cell in host defense against infections, acting as the first line of microorganism control. However, this cell exhibits dysregulated activity in sepsis and may contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. This systematic review aimed to highlight the major scientific findings regarding neutrophil activity in sepsis reported in clinical and experimental research published in the last 10 years. The search was conducted in the Virtual Health Library of PAHO -WHO (BVS) and PubMed databases, and articles published between January 2007 and May 2017 in Portuguese, English, and Spanish were eligible. Article selection was carried out independently by two reviewers (CB and IB). A total of 233 articles were found, of which 87 were identified on PubMed and 146 on BVS. Eighty-two articles were duplicates. Of the remaining 151 articles, 19 met the inclusion criteria after title, abstract, and full-text analysis. Overall, research in clinical samples and animal models of sepsis showed reduced capacity of neutrophils to migrate and delayed apoptosis, but there was no consensus on the phagocytic activity of neutrophils in sepsis. Molecules, such as pentraxin 3 (PTX3), have been analyzed as potential diagnostic markers in sepsis but the diversity of soluble molecules detected in blood samples of sepsis patients did not enable further understanding of the correlation of these circulating molecules with neutrophil activity during sepsis. Optimal understanding of the function of neutrophils in sepsis remains a challenge that, if overcome, would eventually allow targeted therapeutic interventions in patients affected by this severe syndrome

by Edna Adan Ismail 2019

Review by Jason Jarvis

by Edna Adan Ismail 2019

Review by Jason Jarvis

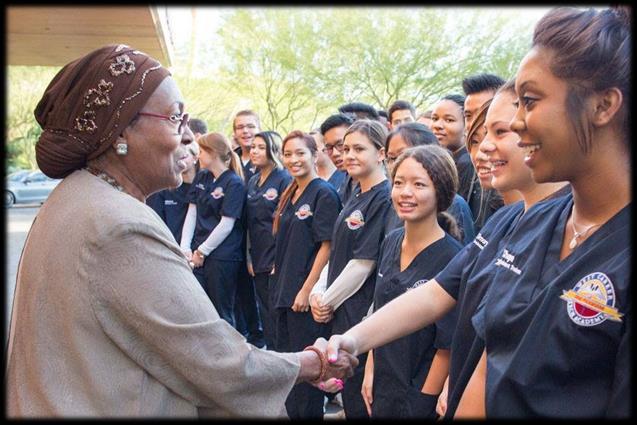

“Persistence and determination are everything,” is one of my favorite quotations, and few biographical accounts I have read exemplify this more than Edna Adan Ismail, author of A Woman of Firsts. Born in Somaliland in 1937, Ismail displayed at a young age a propensity for stubbornness and willingness to buck the social norms of that place and era. The daughter of a physician, Ismail preferred helping her father in the hospital to helping with more traditional duties such as cooking and cleaning around the house. Formal education was forbidden to her, so she taught herself to read and was sent by her father to French-speaking Djibouti for her primary education. At age of nine, her female relatives inflicted upon her the age-old custom of female genital mutilation, an experience she recounts in graphic detail within the pages of A Woman of Firsts. Ismail later won a scholarship to study in England, where she pursued a degree in nursing with specialization in midwifery. Armed with her new profession and the resolve to make the world around her a better place, she returned to Somaliland and endured a lifetime of calamities: the 1969 Marxist revolution (and the ensuing decades-long military dictatorship), failed marriages, open warfare, imprisonment, and the virtual destruction of her country. Through it all, Ismail remained unbroken, laboring tirelessly for many organizations including the WHO and UN, and eventually built a hospital in her hometown upon the killing grounds of forgotten warlords.

“As tough as General Petraeus, as compassionate as the Pope, as tireless as Michael Phelps, as beautiful as Tina Turner, and with a work ethic to rival Bill Gates.”

– Kirsty Young

Edna Adan Ismail was born in Hargeisa, Somaliland in 1937 and is one of the world’s foremost pioneers in nursing, health, education, and women’s rights. Lacking formal education, Edna taught herself to read at the age of seven, before going to school in neighboring Djibouti. She campaigned tirelessly for better healthcare for women and fought on a global stage as the first female Foreign Minister of her country.

She is the director and founder of the Edna Adan Maternity Hospital in Hargeisa, which opened in 2002, and an activist and pioneer in the struggle for the abolition of female genital mutilation. She is also President of the Somaliland Association for Victims of Torture.

In 2010, she opened the Edna Adan Ismail University in Hargeisa. She was married to Mohamed Haji Ibraham Egal who was Head of Government in British Somaliland five days prior to Italian Somalia’s independence and later the Prime Minister of Somalia (1967-1969) and President of Somaliland from 1993 to 2002.

[Kabul, 1989] “The day before I was to fly out after a nine-day stint, eighteen rockets fell on the city, killing civilians and children…Expecting casualties, I hurried to inspect the UN dispensary and was shocked to discover it was completely unprepared for trauma cases or critical emergencies. The mostly bare shelves had eardrops and nose drops, allergy tablets, aspirin, sticking plasters and laxatives. There was no morphine or antibiotics, no bandages, IV fluids, dressings, splints, sutures or surgical instruments. None of that had even been ordered – in a war zone. The man in charge was left with no doubt how angry I was. “Can you hear those explosions?” I told him. “Do you have any idea what that means? Have you ever seen someone brought in bleeding to death, or their bodies peppered with shrapnel wounds? If our compound is hit, lives will be lost not because of the bombing but because of the lack of appropriate first aid and management of their condition. People don’t die of earache and constipation, they die from the wounds caused by bullets and bombs!”…On the way home, via India, I burst in unannounced to the UN Office of Logistics Support in New Delhi and gave them the list of emergency supplies that were urgently needed in Kabul. Then I gave them a piece of my mind.”

“My plans for the [maternity] hospital’s remit changed less than twenty -four hours after we’d opened when an eightyyear-old man was knocked down in the street by a donkey cart right opposite our entrance. Once he fell he cracked his head and was bleeding heavily, so people carried him in like a sack of potatoes, holding his arms and legs as he dripped blood all over my clean floor…before too long, I opened a male ward for patients with every condition – scorpion stings, burns, landmine victims, cleft palates, snake bites, accidental poisonings, kids drinking kerosene, malaria, hepatitis, meningitis, shingles, measles, the lot.”

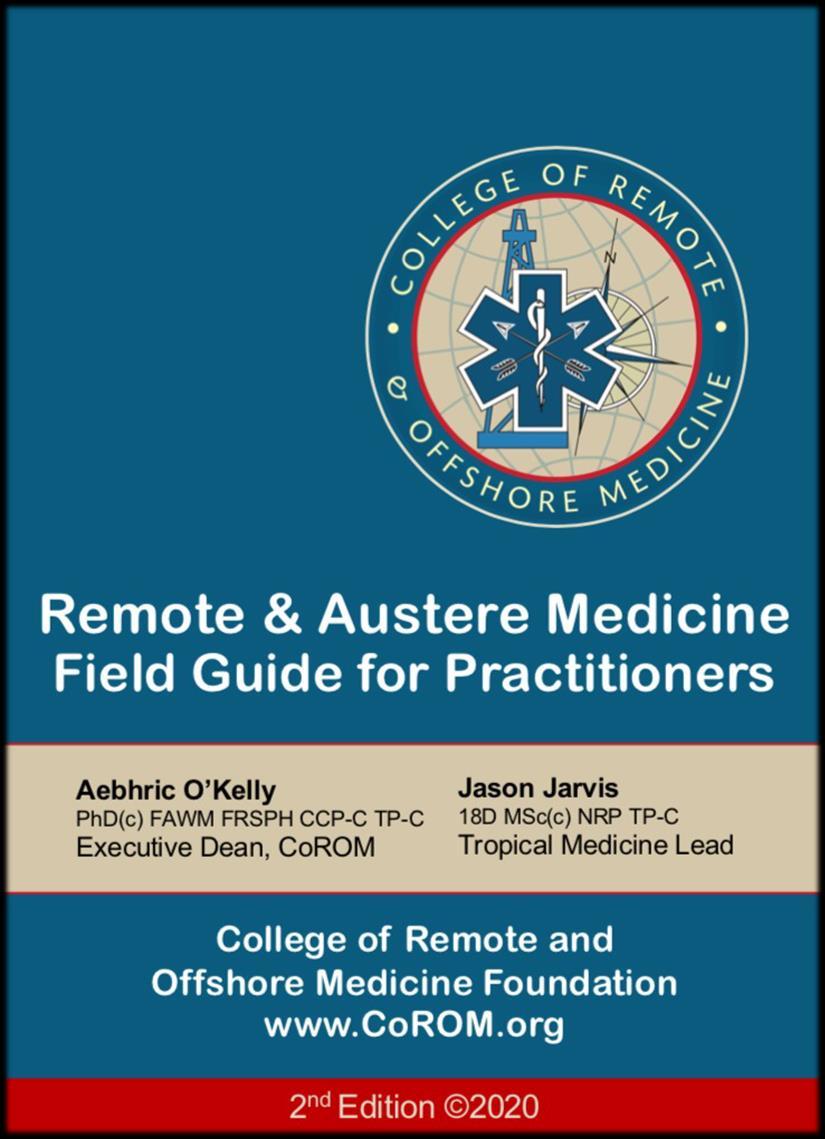

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS & diseases

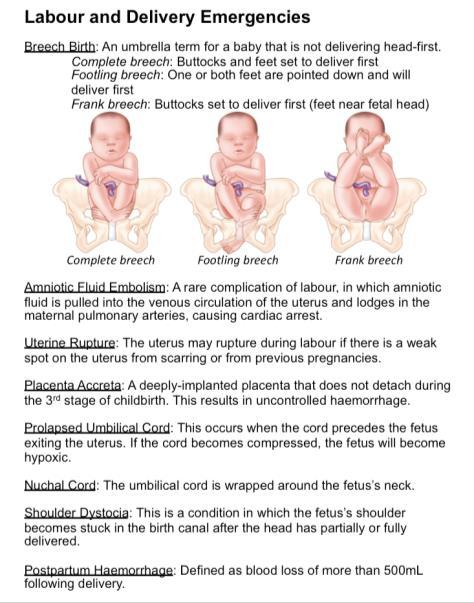

OB/Gyn

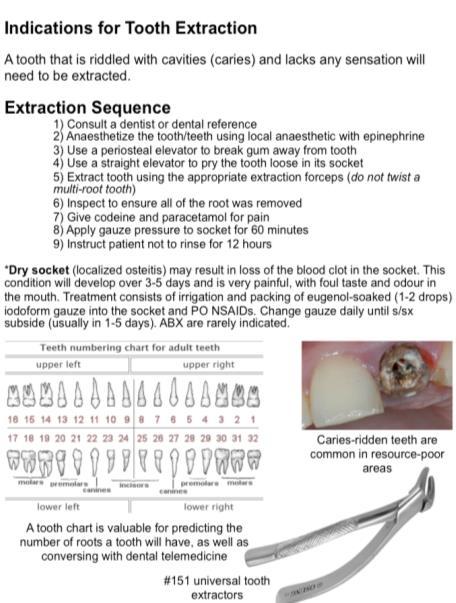

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory techniques

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

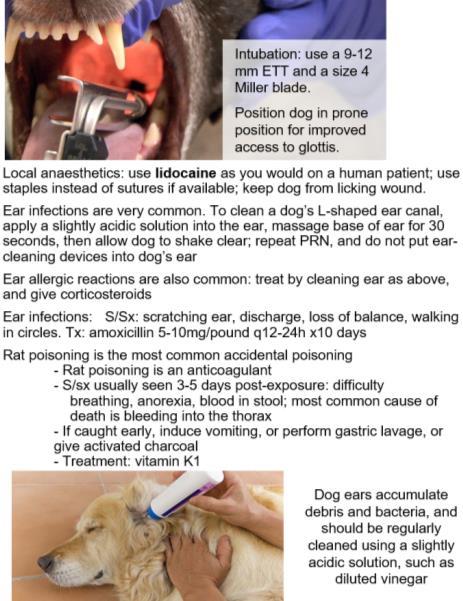

Canine medicine

…and much more!