John Clark JD MBA NRP

As we step into 2025, CoROM continues to embrace innovation, growth, and the pursuit of academic excellence The coming year is poised to be transformative, with three major initiatives defining our strategic direction. These initiatives reflect our commitment to providing exceptional education to our community in remote and austere environments, preparing our students to lead and excel.

One of our most exciting undertakings for 2025 is the relaunch of the Master of Global Health Leadership & Practice programme Under the expert leadership of Dr Nicholas Zuber, this programme will adopt a forward-thinking curriculum designed to equip healthcare leaders with the knowledge and skills necessary to address global health challenges. Dr. Zuber brings a wealth of experience and vision to this role, ensuring that the programme remains relevant and impactful in a rapidly changing world

The revamped curriculum will focus on critical areas such as remote health systems strengthening, leadership in crises, and the intersection of technology and healthcare delivery. Practical application will remain a cornerstone, with students engaging in realworld experiences that address pressing global health issues. As we relaunch this programme, we aim to create a new generation of leaders who will influence policy, innovate solutions, and drive positive change on a global scale.

Continuous professional development (CPD) has always been central to CoROM’s mission, and 2025 will see significant enhancements in this area. Collaborating with our partners at FlightBridgeED, we have developed a new Learning Management System (LMS) that will serve as the backbone of our redesigned CPD courses This innovative platform combines state-of-the-art technology with user-friendly design, enabling us to deliver high-quality, interactive learning experiences.

The redesigned CPD courses will offer a modular structure, allowing learners to customise their educational pathways to suit their professional goals. Enhanced multimedia content and robust assessment tools will provide a dynamic and engaging learning environment The integration of the new LMS marks a significant leap forward in how we deliver education, ensuring that our courses remain accessible, flexible, and impactful for medical professionals worldwide.

The BSc in Remote Paramedic Practice has long been a cornerstone of our academic offerings, and 2025 will see substantial investments in this programme to enhance its quality and relevance including a clearer pathway for licensure/accreditation in the student’s home country. We are updating core modules to reflect the latest advancements in remote paramedic practice, ensuring that our students are well-prepared to meet the demands of their roles.

One of the most exciting developments is the expansion of face-to-face learning opportunities Students will have increased access to hands-on training sessions in Malta, where they can hone their practical skills under the guidance of experienced faculty Additionally, students will have access to new clinical rotation sites in Kumasi, Ghana and in Gunnison, Colorado, USA, providing students with diverse, real-world experiences in remote and austere medical settings

These enhancements are driven by our commitment to delivering a programme that not only meets but exceeds the expectations of students and employers alike By providing a comprehensive blend of theoretical knowledge, practical training, and clinical experience, we aim to produce graduates who are ready to excel in the challenging and rewarding field of remote paramedic practice

These three major projects represent more than just academic initiatives; they embody CoROM’s core values of innovation, excellence, and service They are a testament to our unwavering commitment to providing top-tier education and training for medical professionals who operate in some of the world’s most challenging environments.

While these projects will demand significant effort and collaboration, they also offer immense opportunities for growth and impact As we embark on this journey, I invite our faculty, students, alumni, and partners to join us in shaping the future of CoROM Your insights, contributions, and support are invaluable as we work together to achieve our shared vision.

The future of CoROM is bright, and 2025 promises to be a landmark year in our history. With the relaunch of the Master of Global Health Leadership & Practice programme, the redesign of our CPD courses, and the advancements in the BSc in Remote Paramedic Practice, we are setting the stage for a new era of excellence and innovation.

Thank you for being an integral part of this journey. Together, we will continue to empower medical professionals to lead, innovate, and make a difference in remote and austere environments worldwide Here’s to a successful and transformative 2025! Warm regards,

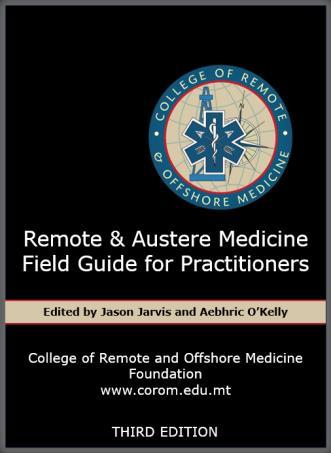

CoROM finished strong in 2024, with 2025 looking to become the College’s new high-water mark The Medicine in the Mediterranean conference is just around the corner, academic programs and clinical rotation sites are humming along, and the first steps toward publication of the third edition Remote and Austere Medicine Field Guide for Practitioners have been taken. This issue of The Compass contains two pieces on the war in Ukraine – the first is an account of a recent training evolution conducted by CoROM in Kiev, while the other is a review of a December 2024 article published in The Lancet.

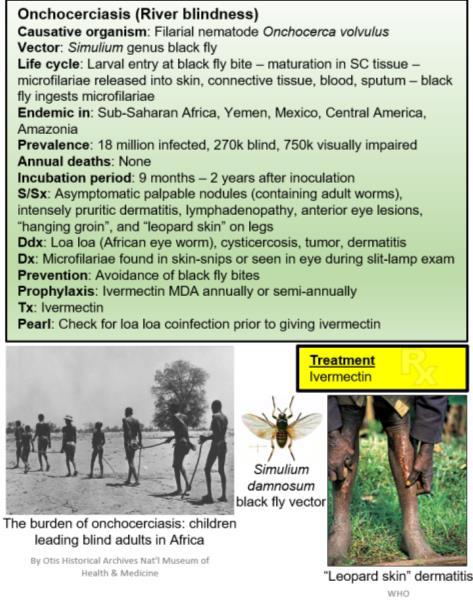

Dr. Bajic and Dr. Bozickovic return with another case report from their clinical practice in Slovenia; Aebhric O’Kelly’s Improvised Medicine piece covers an innovative alternative to ultrasound gel put into practice at a recent training course in Norway; my own pieces on tropical medicine and trauma focus on African sleeping sickness and The Lancet’s assessment of battlefield casualties in Ukraine, respectively.

Thanks also to Mindi Counts and Ginney Hitchon for both their humanitarian efforts in Nepal and the photo that graces this edition of The Compass Jason Jarvis MSc

Jason Jarvis is a paramedic and former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience in countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan He is a freelance medical educator who teaches for CoROM, the U.N., the U.S. Department of Defense, Harborview Medical Center, and Seattle Children’s Hospital Jason is a PhD student in Widener University’s Health Professions Education program and holds a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Abstract

This case report highlights an instance of combined shock resulting from pneumothorax and septic shock in a patient who presented with acute respiratory distress and hypotension This report focuses on the clinical approach, immediate management strategies, and the significance of early intervention.

A 57-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department at a local health center with acute respiratory distress and chest pain. Upon arrival patient had pale and clammy skin, his BP was 100/60 mmHg, HR 110/min, SpO2 85% on room air, RR 30/min. He had GCS 14 with pupils 2 mm wide, reactive, without face asymmetry. ECG showed sinus tachycardia with HR 115/min, blood glucose was 5 7 mmol/L Initial assessment revealed decreased breath sounds and hyperresonance on both apices of the chest.

Slaven Bajic MD, Emergency Medicine Specialist, MCoROM

Milan Bozickovic MD, Emergency Medicine Resident

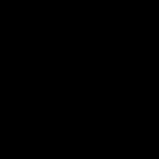

Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) showed absence of pleural sliding on both sides of the apices. According to the medical history, five days prior he was involved in an altercation resulting in physical assault, during which he sustained fractures to the 5th and 6th ribs on the right side The clinical presentation, POCUS findings and medical history were all leading to the suspicion of a tension pneumothorax. High-flow oxygen and intravenous fluid resuscitation were initiated, followed by immediate needle decompression, resulting in rapid symptomatic relief

We decompressed both sides of the lung, which resulted in an adequate increase in the oxygen saturation level. Concurrently, the patient exhibited signs of possible combined shock. This was suspected due to hypotension that was refractory to fluid resuscitation and decompression of the pneumothorax Vasopressor support with ephedrine and norepinephrine was also administered, after which we were able to hemodynamically stabilise the patient. Given the severity of the condition, the patient was transferred into the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local general hospital for close monitoring and advanced supportive care. At the ICU it was confirmed that the underlying condition was mediastinitis causing septic shock, along with multiple rib fractures on both sides and a resolved pneumothorax

POCUS of the left lung. “Barcode sign” on M mode suggests pneumothorax.

POCUS imagery of optic nerve sheath diameter,

The etiology of mixed shock in this patient involved two primary components:

1. Obstructive shock secondary to pneumothorax: The traumatic injury sustained in the altercation likely caused rib fractures leading to bilateral pneumothorax, resulting in compromised ventilation and decreased venous return due to mechanical pressure.

2. Septic Shock: The patient exhibited signs consistent with septicemia, potentially exacerbated by the trauma or a secondary infection, which led to systemic inflammatory response and vascular permeability changes causing hypotension

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) and needle thoracostomy play vital roles in the early management of pneumothorax, particularly tension pneumothorax, which is a lifethreatening condition. POCUS allows clinicians to rapidly assess the thoracic cavity and identify pneumothorax with high accuracy. By visualizing characteristic signs, such as the absence of lung sliding and the presence of a "lung point," POCUS enables swift diagnosis, often more quickly and with greater sensitivity than traditional chest X-rays. In the context of a suspected tension pneumothorax, the ability to recognize the condition promptly is crucial to prevent rapid cardiovascular compromise

Here, needle thoracostomy is a critical intervention, serving as an immediate decompressive procedure. By inserting a needle into the pleural space, trapped air can be quickly released, alleviating pressure on the lungs and cardiovascular system, thus preventing further deterioration of the patient's condition The integration of POCUS for diagnosis, coupled with the prompt application of needle thoracostomy, exemplifies the importance of rapid intervention in emergency medicine. Together, they enhance patient outcomes by facilitating accurate, timely, and efficient care in situations where every moment counts

This case demonstrates the complexity of managing patients with dual etiologies of shock, emphasizing the importance of rapid diagnosis and treatment Recognizing the signs of tension pneumothorax and instituting timely interventions such as needle thoracostomy can be life-saving. Concurrent management of sepsis with early fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support is vital to addressing underlying infectious etiologies. Multidisciplinary coordination and vigilant monitoring are imperative to successful patient recovery in such critical scenarios.

We thank the medical and nursing teams for their dedication and effective implementation of protocols that ensured a positive outcome for this patient

Conflict of interest

None.

References

1. Management of Pneumothorax

Light, R. W. (1994). Pneumothorax. *New England Journal of Medicine*, 331(6), 409-412. doi:10.1056/NEJM199408113310607

Brown, S., et al. (2010). British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010: Management of pneumothorax *Thorax*, 65, ii18-ii31 doi:10 1136/ thx 2010 136986

2. Needle Thoracotomy (Decompression) in Tension Pneumothorax

Leigh-Smith, S , & Harris, T (2005) Tension pneumothorax time for a rethink? *Emergency Medicine Journal*, 22(1), 8-16 doi:10 1136/ emj 2003 011031

Brooks, A J , et al (2003) Assessment of clinical and radiological factors affecting timeframe for successful treatment of tension pneumothorax in prospective observational study. *Injury*, 34(9), 681686 doi:10 1016/ S0020-1383(03)00054-4

3. Septic Shock Management

Rhodes, A., et al. (2017). Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016 *Intensive Care Medicine*, 43(3), 304-377 doi:10 1007/s00134-017-4683-6

Singer, M , et al (2016) The Third International Consensus Definitions fo Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) *JAMA*, 315(8), 801-810 doi:10 1001/ jama 2016 0287

Dr. Slaven Bajic is an emergency medicine physician with extensive experience in both ER and prehospital settings. He has also worked in remote areas and war zones, including leading the ER at the Role 2E military hospital in Koulikoro, Mali. He is a certified POCUS ultrasound instructor for COROM, Winfocus and EUSEM. Dr. Bajic is an Emergency Medicine Specialist at Izola General Hospital, Izola, Slovenia.

Dr. Milan Bozickovic is an emergency medicine physician working in the emergency department and prehospital unit. He is a trainee within the Winfocus ultrasound mentorship program, and is passionate about working with POCUS ultrasound and in the delivery of emergency care in high pressure environments. Dr. Bozickovic is an Emergency Medicine Resident at Izola General Hospital, Izola, Slovenia.

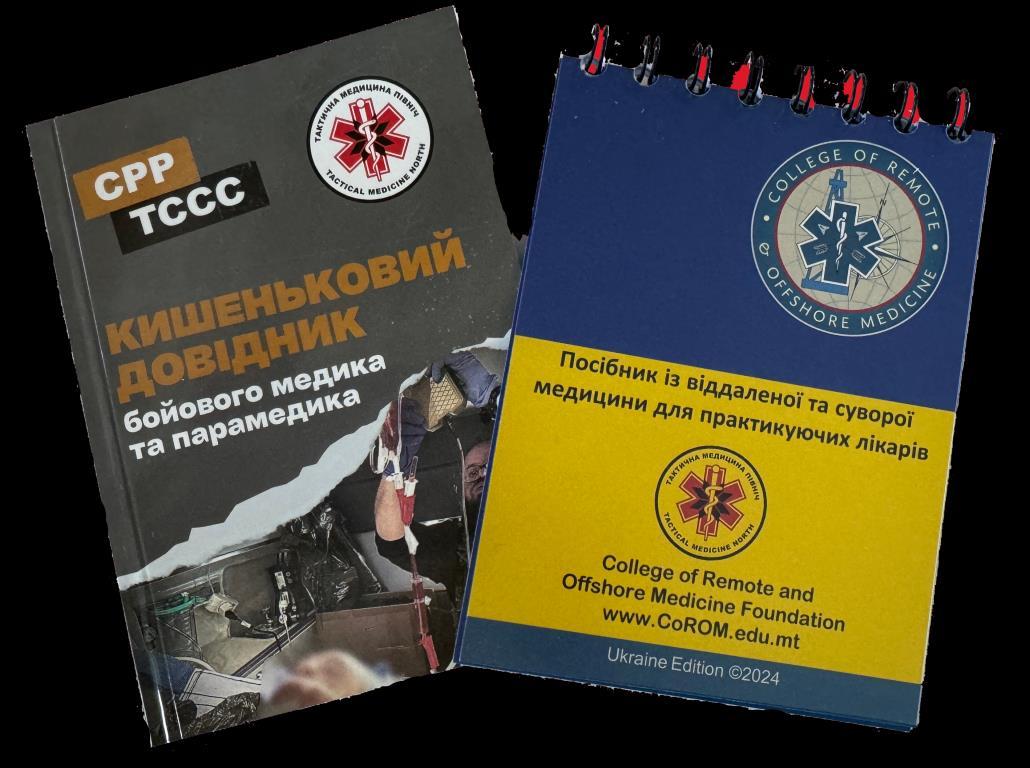

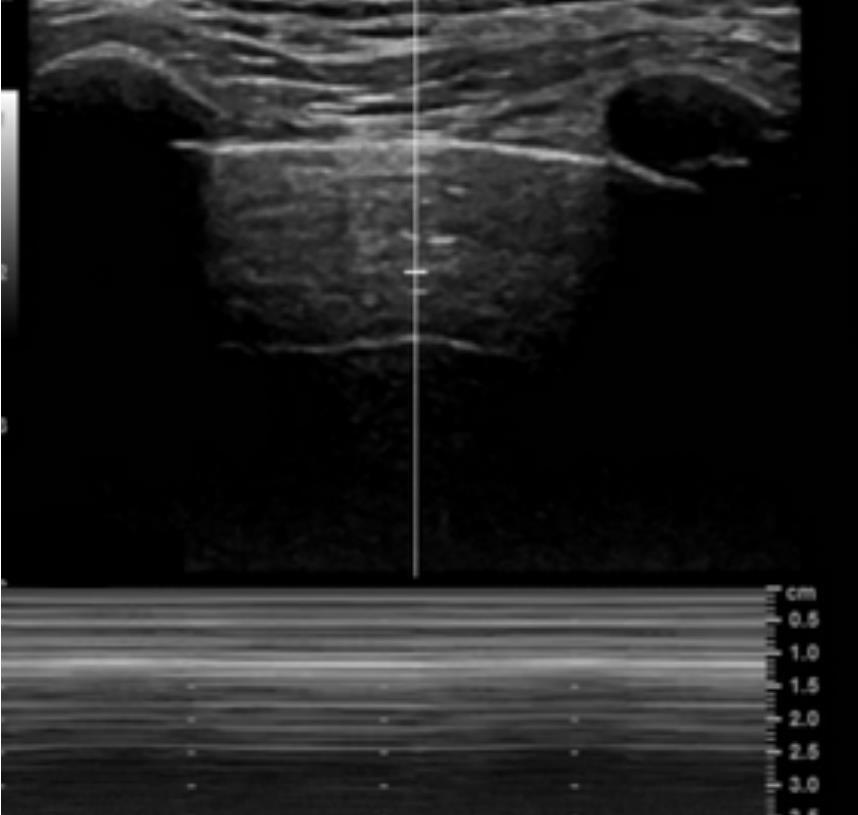

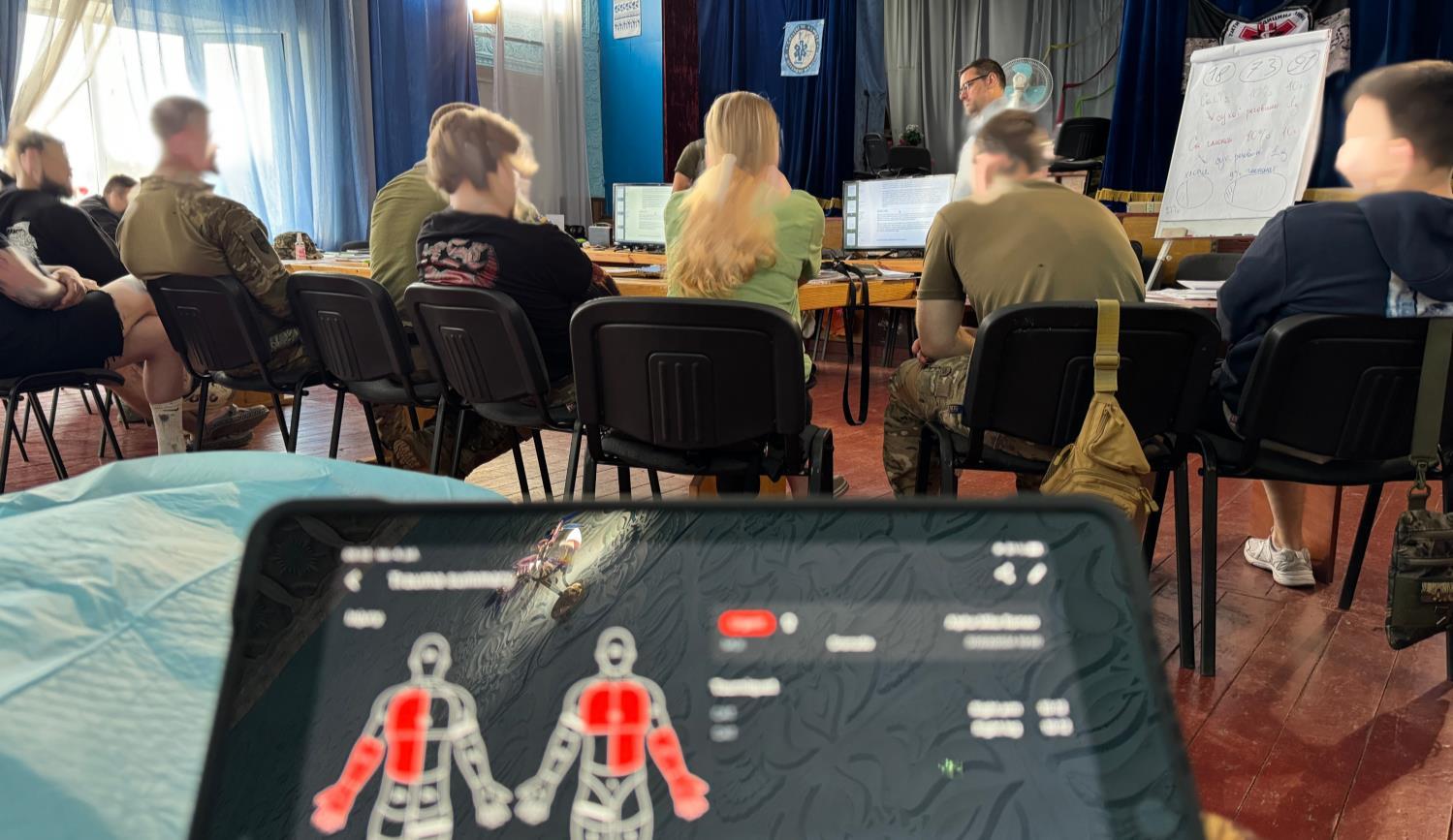

In July 2023, the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation (CoROM) conducted the international Austere Emergency Care (AEC) course in Malta, with funding support from Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency/European Union (MSB/EU). Tactical Medical North (TMN), a Ukrainian organisation, participated in this Prolonged Field Care (PFC) training due to the urgent need for enhanced capabilities among frontline medics and stabilisation points during the ongoing full-scale invasion. The increasing delays in evacuation made it evident that medics required advanced education and skills to manage severe casualties beyond the standard “Golden Hour” timeframe.

The course was a resounding success, prompting a request for a tailored PFC program for TMN in Ukraine. Drawing from frontline experiences and the specific needs of stabilisation points, CoROM developed the Damage Control Resuscitation – Ukraine (DCRUkraine) course. This program incorporated current clinical practical guidelines (CPGs) from the Defense Health Agency (DHA) website, https://deployedmedicine.comDeployed Medicine.

In July 2024, three CoROM faculty members deployed to Ukraine to deliver two courses. The first course targeted active-duty medics and TMN instructors. Designed as a pilot, its primary goal was to familiarise TMN instructors with the course content, preparing them as instructor candidates under a "Train-the-Trainer" model. In the subsequent course, CoROM instructors assumed a supporting role, observing and assisting TMN instructors as they led the sessions. The course curriculum was grounded in TCCC (Tactical Combat Casualty Care) and PFC guidelines, which were translated into Ukrainian to ensure accessibility and relevance.

The program's key emphasis introduced and developed competency in fundamental clinical procedures to provide basic life support as adjuncts to advanced skills. Fundamental skills include trauma assessment, primary survey (“MARCH-PAWS”), secondary survey, tourniquet application, pressure dressings, tourniquet replacement, tourniquet conversion, wound packing, basic airway manoeuvres, airway clearance, use of airway adjuncts, positioning for airway management, recovery position, pain management, administration of antibiotics, reassessment, blood transfusion, wound care, advanced trauma assessment, and prolonged casualty care.

The program's objectives include high-level procedural skills, complex patient management, and advanced clinical decisionmaking. Clinical practice guidelines from the DHA website, Deployed Medicine, and its mirrored Ukrainian website provided the underlying course competencies and objectives. Some advanced interventions within the advanced course include advanced trauma assessment, complex resuscitation with blood and blood products, prolonged field care, advanced pain management, tourniquet conversion and downgrading, advanced antibiotic and antimicrobial therapies, surgical airway management, chest tube insertion and management, advanced surgical interventions, retrograde or resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) identification and support, advanced surgical wound care, surgical site infection management, advanced burn care, advanced intubation techniques, mechanical ventilation, and advanced hemodynamic monitoring.

The delivery of the DCR-Ukraine course was thoughtfully structured to maximize engagement and adaptability. Instructors resided offsite and were transported daily to the remote training location, which provided ample facilities for both classroom instruction and hands-on skills-based training. The curriculum was meticulously pre-established at 90%, leaving 10% flexible to address specific needs identified through end-of-day faculty discussions and morning feedback sessions from students during open lab time. Patient case scenarios and situational exercises formed the backbone of the training, fostering small group learning and open discussions that enhanced critical thinking and real-world application. This iterative approach, enriched by continuous feedback and practical scenarios, ensured that the course remained both relevant and effective in meeting the dynamic needs of the medics.

Engagement with partner forces during the DCR-Ukraine course underscored the importance of a two-way learning process, where knowledge exchange benefits both parties and enhances global health practices. Participation in such activities proved invaluable for professional and personal development, offering unique insights into medical care delivery in austere environments. Despite deployments across Ukraine and two other active war zones, the omnipresent threat of aerial bombardment made personal safety and operational security paramount, requiring constant vigilance and access to bomb shelters. The logistical complexities of delivering training in a war zone remained significant, even when ample resources were available, highlighting the importance of meticulous planning and adaptability. This experience demonstrated the resilience and determination needed to ensure the success of critical training programs in challenging and high-risk settings.

The DCR training program significantly enhanced the clinical capabilities of Ukrainian medical teams, equipping them with advanced procedural skills and clinical decisionmaking support necessary for effective DCR. The collaboration between the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine and TacMed North proved invaluable. The lessons learned from this training initiative will inform future programs, ensuring continued prehospital care and clinical governance improvement. This iterative process of evaluation and adaptation is critical for meeting the evolving challenges of medical care in conflict zones.

Jason Jarvis MSc 18D NR-Paramedic

A recent article published in Nature Communications1 reminds us that the state of infectious diseases is not static.

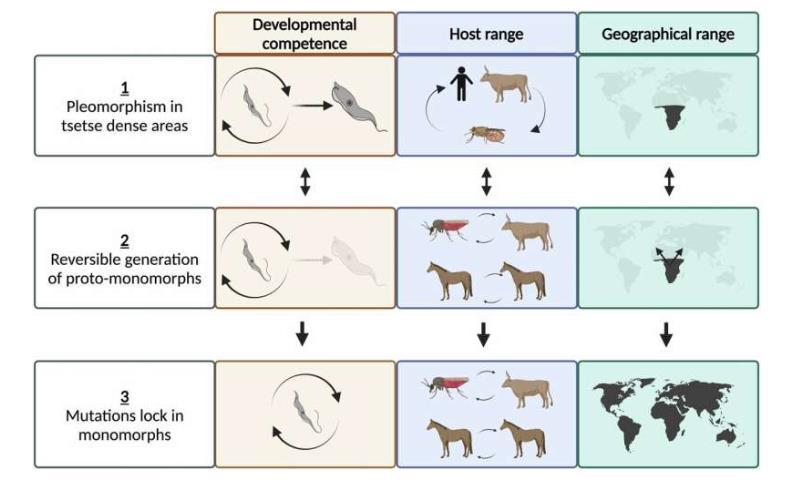

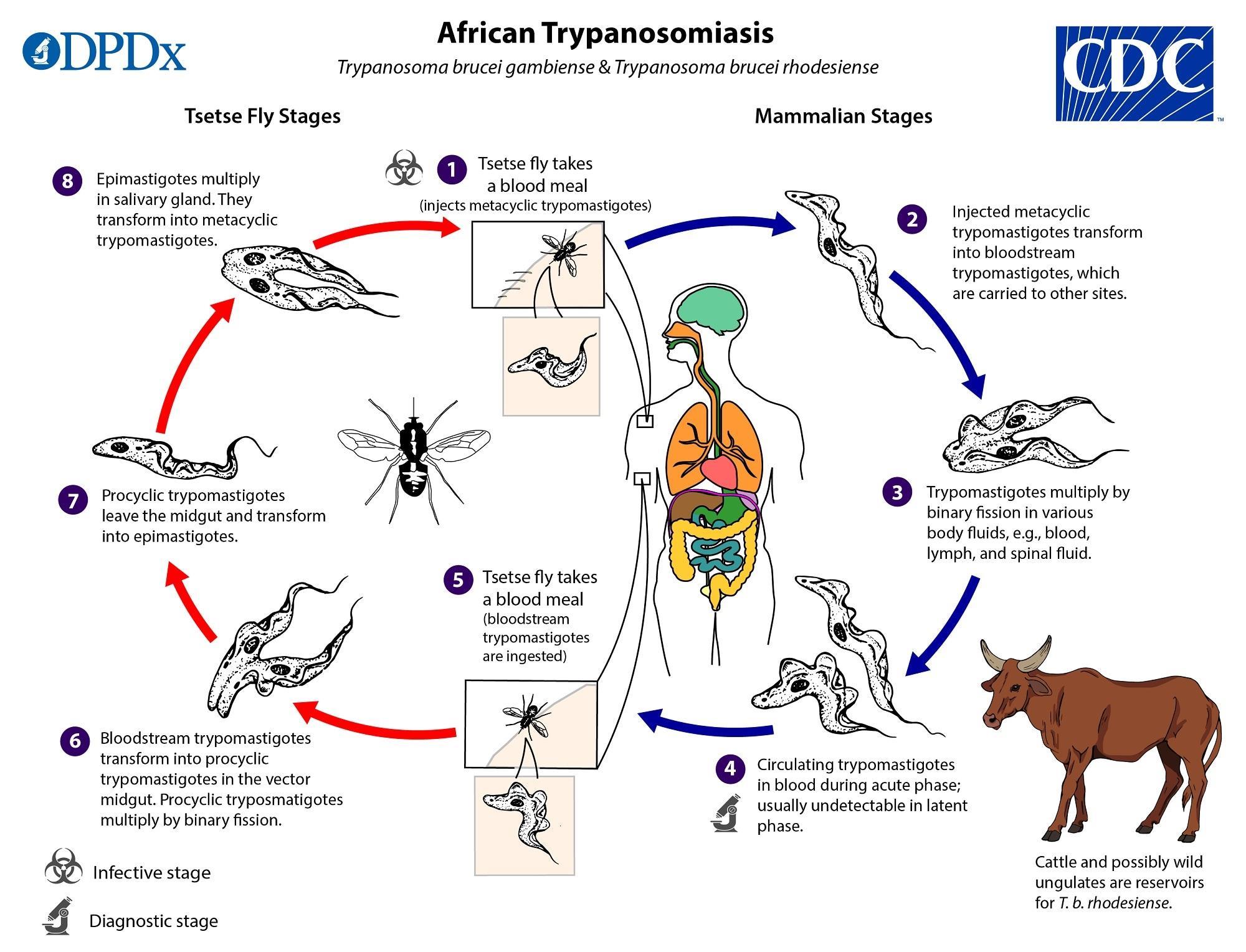

“Mechanisms of life cycle simplification in African trypanosomes” by Oldrieve, et al. examines the processes by which protozoal parasites can adapt to a changing environment.

Both the genomes and geographic distribution of infectious diseases are subject to various natural and manmade selective pressures, such as antigenic shift, antigenic drift, antimicrobial selective pressure, climate change, changes in land use, importation, vector control measures, and the coevolution of the human genome in response to disease.

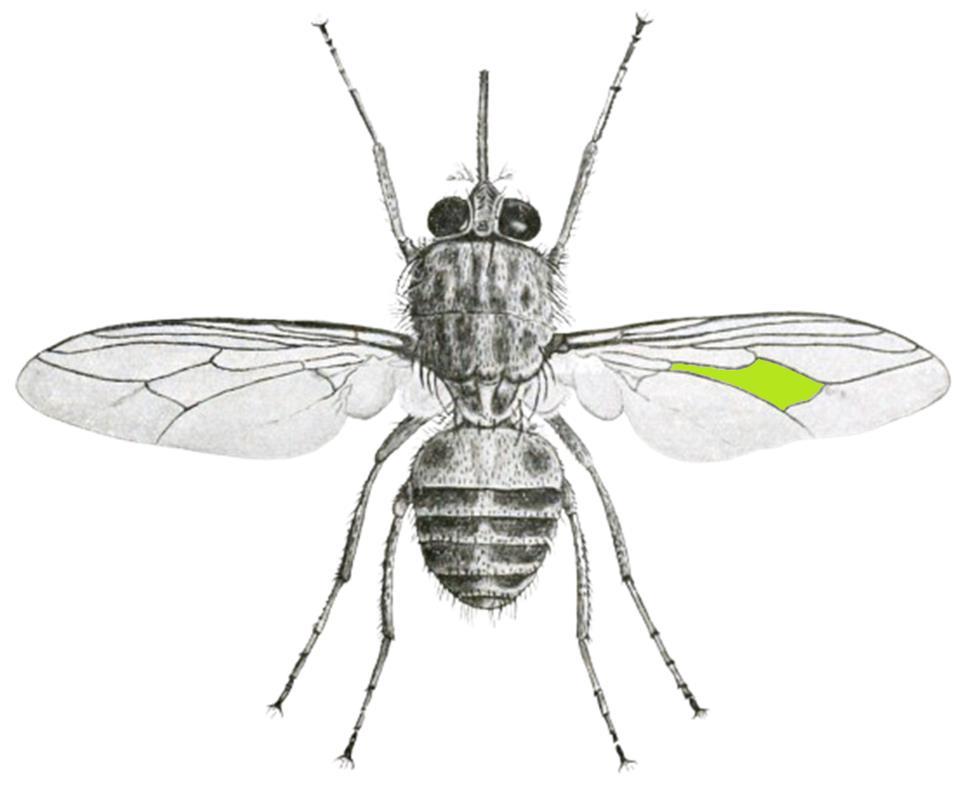

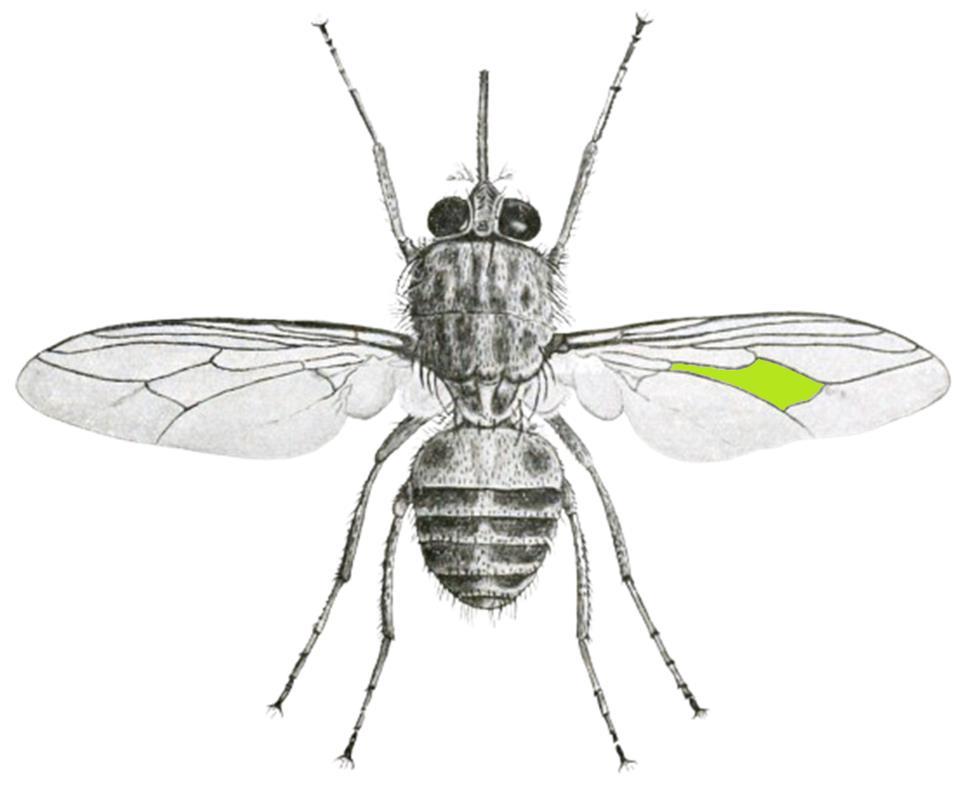

This article studies the molecular pathways by which trypanosomes acquire ways to spread infection without the use of the traditional insect vector – the tsetse fly. Glossina morsitans tsetse flies are endemic to the equatorial region of Africa. The limited geographic range of tsetse flies thus maintains the natural acquisition of human sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis) within a fairly narrow swathe of the world. Trypanosoma brucei gambiense occurs mainly in western Africa, while T. brucei rhodesiense occurs mainly in eastern Africa.

However, in at least three instances ancient trypanosome species either changed their insect vector or did away with insect vector transmission altogether.

The first example is American trypanosomiasis, in which central and South American flightless reduviid bugs vector T. cruzi parasites.

Surra, a trypanosome disease of nonhuman mammals in North Africa, the Middle East, and central/South America, is vectored via biting flies such as the tabanids and stable flies. Surra (T. brucei evansi) may also be transmitted via vampire bats.

In the third example, dourine (T. brucei equiperdum) has no insect vector but instead exists as an equine sexually transmitted infection.

The world is an ever-changing place, and we must remain vigilant for shifting patterns of disease pathology and the means by which they are acquired.

1 Oldrieve GR, Venter F, Cayla M, et al. Mechanisms of life cycle simplification in African trypanosomes. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10485. Published 2024 Dec 2. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-54555-w

Glossina morsitans – better known as the tsetse fly – is the vector of African sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis)

The tsetse fly can be differentiated from other flies by recognition of the hatchet-shaped cell within the veins of the wings (highlighted area)

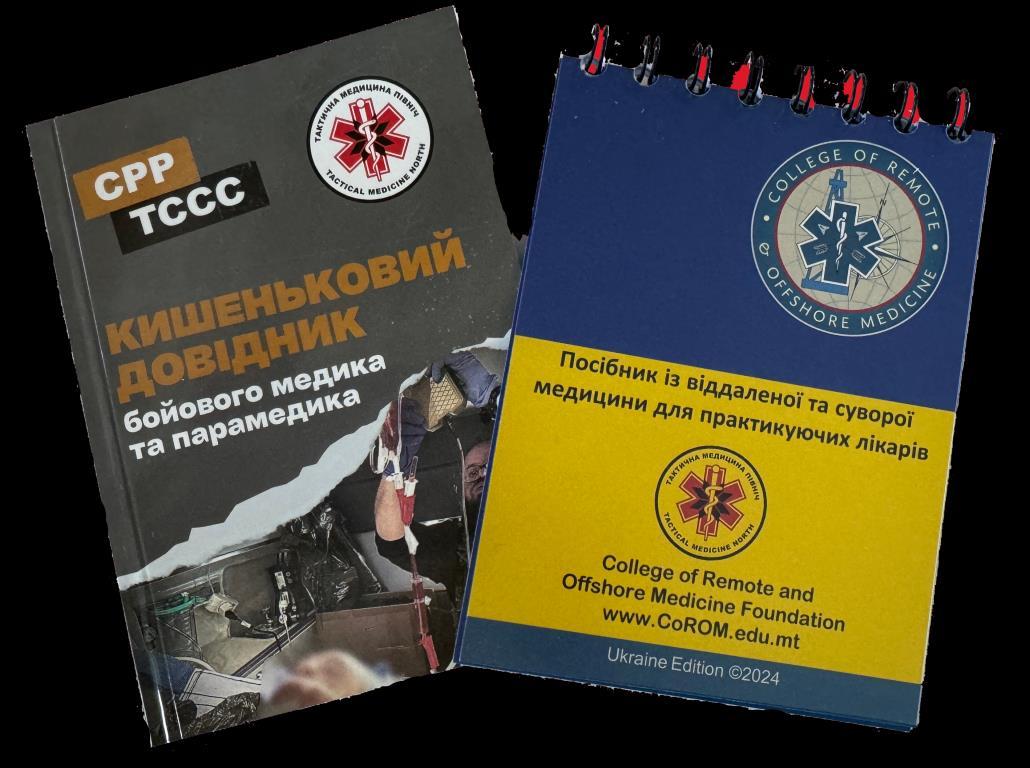

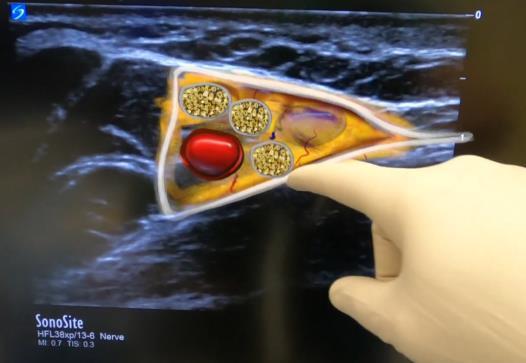

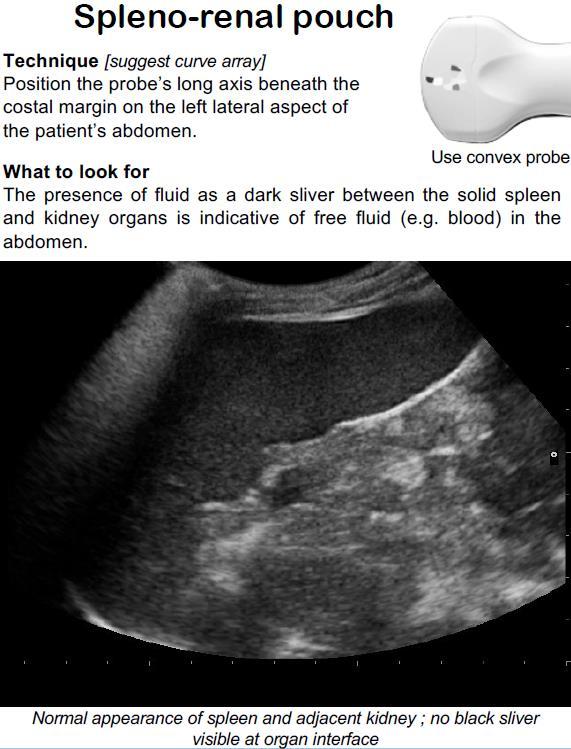

In austere environments, the unavailability of standard ultrasound gel poses challenges for effective imaging with devices like the Butterfly iQ3 probe. An innovative solution involves placing the probe's head into a Ziplock bag filled with water, ensuring the transducer is adequately covered. This method creates a liquid medium that facilitates the transmission of ultrasound waves, thereby enabling clear imaging even in resource-limited settings.

Aebhric O’Kelly M.Psy DTN FRSM FAWM

A study1 published in Military Medicine evaluated intravenous fluid (IVF) bags as substitutes for gel standoff pads in musculoskeletal point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) The researchers compared images obtained using standard gel standoff pads with those acquired using IVF bags of various sizes. The findings indicated no significant difference in image quality between the standard devices and the IVF bags for specific examinations, suggesting that fluid-filled bags can effectively serve as alternatives to traditional gel pads in resource-constrained environments.

However, it is important to note that while using a water-filled Ziplock bag can be a practical alternative, this approach may introduce potential sources of error and bias Factors such as air bubbles, inconsistent water coverage, or improper sealing of the bag can degrade image quality. Additionally, the bag's material might attenuate the ultrasound signal, potentially affecting the accuracy of the imaging Therefore, while this method offers a viable solution without standard ultrasound gel, careful attention to technique is essential to minimise potential errors.

References

1 Mount C, Taylor D, Skinner C, Grogan S. Intravenous Fluid Bag as a Substitute for Gel Standoff Pad in Musculoskeletal Point-of-care Ultrasound. Mil Med. 2023;188(5-6):e949e952 doi:10 1093/milmed/usab422

Prolonged field care course in Norway using Ziplock bag with water

Jason Jarvis MSc 18D NR-Paramedic

On 9 December 2024, The Lancet published “Ukrainian battlefield medicine” by Rebecca Sers.1

The axiom “If you wish to become a surgeon, follow an army” is widely attributed to Hippocrates, and CoROM has paid heed to this advice since the inception of the College. From 2000 until the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the “best” casualty data stemmed from U.S. and allied nations’ military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan, upon which CoROM and countless other organizations built their training curriculum. Now that Ukraine has become the tip of the proverbial spear, medical practitioners and trainers alike should be paying close attention to what is happening there.

Highlights from “Ukrainian battlefield medicine”1 –

Electronic emissions from devices such as mechanical ventilators are being detected by Russian drones. The lesson here is don’t throw out that Ambu bag just yet – it may still be of service to you and your patients.

Once robust medevac capabilities were installed within the Iraq and Afghanistan combat theaters, there was little need for Prolonged Field Care (PFC). Special Operations medics who were brought up in the pre-911 era remembered the paradigm of those days: prolonged field care was the rule, not the exception. The previous advice on Ambu bags holds true here as well, that is to say, what is old may become new again.

In Ukraine, frontline medical personnel are routinely conducting PFC prior to evacuation, in addition to Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) and even Damage Control Surgery (DCS).

With an estimated total of 80,000 Ukrainian soldiers killed and 400,000 wounded, data on injury patterns has emerged. The Ukrainian Ministry of Health reports that hemorrhage accounts for at least 60% of all battlefield deaths. Common injury patterns include “shrapnel injuries to the limbs, trunk, and head from first-person view drones, and mine explosive injuries with limb amputations.”1

In keeping with the tenets of Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), fresh whole blood is no longer a procedure restricted to hospitals, with Ukrainian frontline medics being trained in this lifesaving procedure. Case in point: “The first transfusion under trench conditions was performed on November 11, 2023 by an Azov brigade combat medic.”1

Common evacuation platforms utilized in Ukraine include litter carries, all-terrain vehicles, armored extraction vehicles, and pickup trucks.

The many excellent Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) of the Joint Trauma System2 (JTS) are being put to good service in Ukraine. JTS recommendations specifically mentioned within this article include protocols on tourniquets, hemostatic pressure dressings, tranexamic acid, antibiotics, TCCC, DCR, and DCS.

Despite the heroic medical efforts on display in Ukraine, the country itself remains mired in an existential fight for survival. Rebecca Sers observes that “…some aspects of the military system are innovating dramatically, and other parts are simply struggling to survive.”1

1 Sers R. Ukrainian battlefield medicine. Lancet. Published online December 9, 2024. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02677-1

2 Clinical practice guidelines. Joint trauma system. Accessed December 31, 2024. https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/PI_CPGs/cpgs

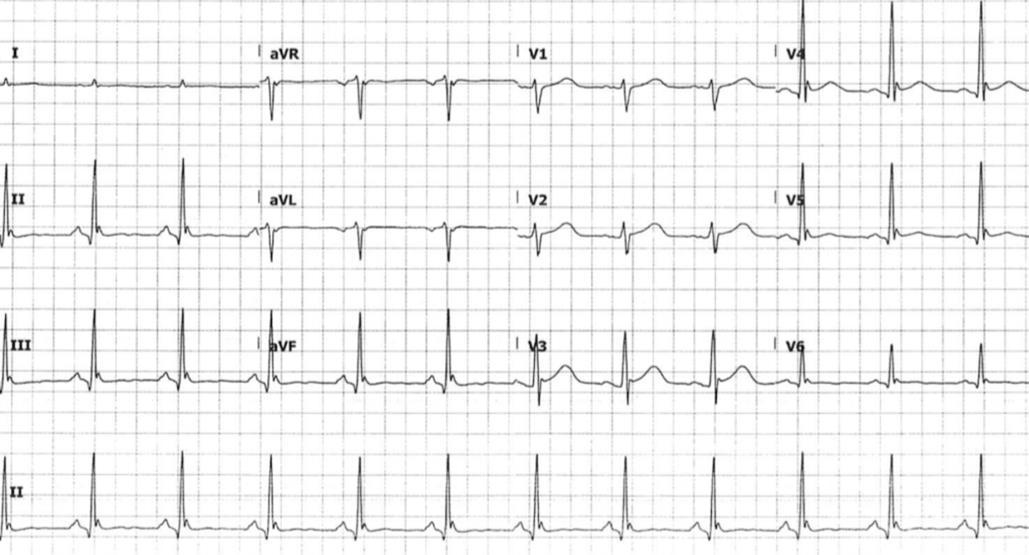

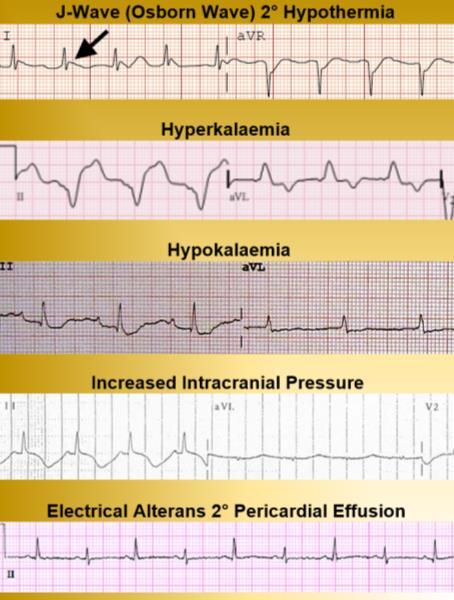

Which of the following reversible causes of cardiac arrest is shown in this 12-lead?

A. Hypothermia

B. Hypokalemia

C. Cardiac tamponade

D. Pulmonary embolism

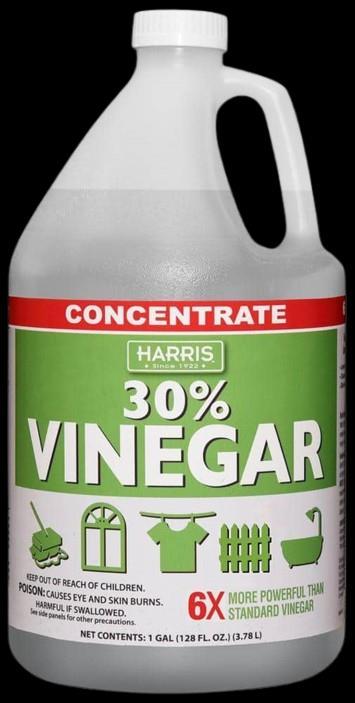

As the dive medical technician assigned to a National Geographic diving expedition in the Lesser Sunda Islands, you are preparing a large batch of 5% acetic acid (vinegar) for treatment of jellyfish stings.

Beginning with a stock of concentrated (30%) acetic acid, how many mL should you mix with water to create five liters of 5% acetic acid?

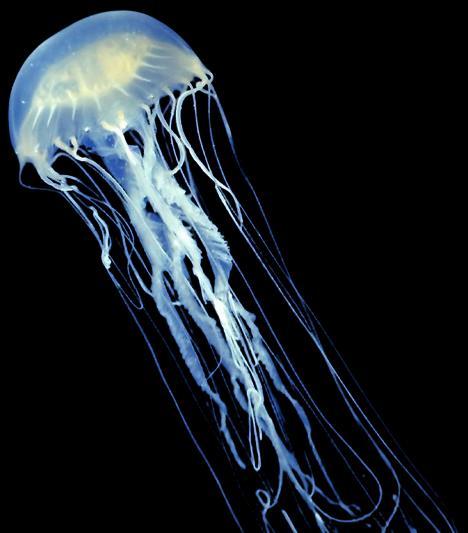

While covering a series of scuba dives off the coast of East Timor, you apply 5% acetic acid to three divers who suffer jellyfish stings. As they are recovering in your boat, they spot one of the jellyfish in the water. You identify this as a:

A. Irukanji

B. Box jellyfish

C. Cannonball jellyfish

D. Portuguese man o’ war

Medical References

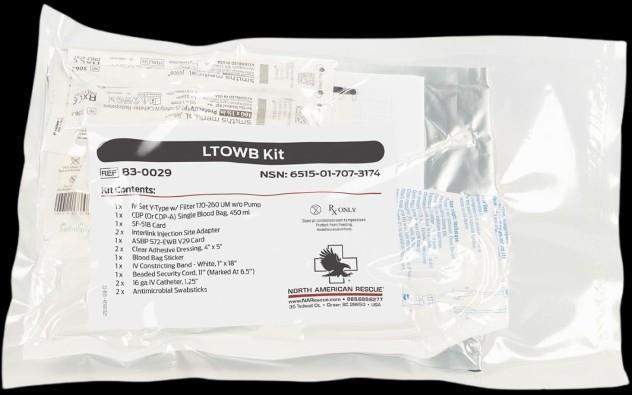

Gear

Low-titer O whole blood kit available from North American Rescue

$100.99

https://open.spotify.com/episode/6J0lLUGCrbIMTozU6QFOKo

This week, Aebhric O’Kelly talks with Dr. Jamie Riesberg, who created the separation of Prolonged Casualty Care (PCC) from Prolonged Field Care (PFC). Dr. Riesberg has extensive experience in military medicine, focusing on the evolution of prolonged field care and the transition from the Global War on Terror (GWOT) to future conflicts. He emphasizes the importance of adapting medical training to current battlefield realities, including lessons from Ukraine. Dr. Riesberg advocates for a shift in mindset toward PCC and the need for continuous hands-on experience for medics. They also discuss the challenges posed by policy and training limitations, urging a more robust approach to medical care in combat situations.

Prolonged field care is essential for future military operations. Past conflicts influence the evolution of military medicine. NATO plays a crucial role in standardizing medical training Lessons from Ukraine highlight the need for adaptability in medical care. Expectant casualty management is a growing concern in military medicine. Curiosity and creativity are critical traits for success in austere medicine.

Bedside Rounds Episode 74

What does it mean when a computer can make better decisions than a human?

https://open.spotify.com/episode/32Zw4IRlEqJr2mUe7npezC

This Week in Virology Episode 1175

TWiV reviews the appearance of poliovirus in Europe, mystery disease in DRC, global burden of Chikungunya, viruses of parasitic nematodes, and more

https://open.spotify.com/show/6GifipQkBOoRzOpMxw3Xix

Anatomy & Physiology – Bit by Bit Episode 51

Respiratory anatomy and spirometry

https://open.spotify.com/show/6ZGQXkt6mJ6SKsZwLjeJCc

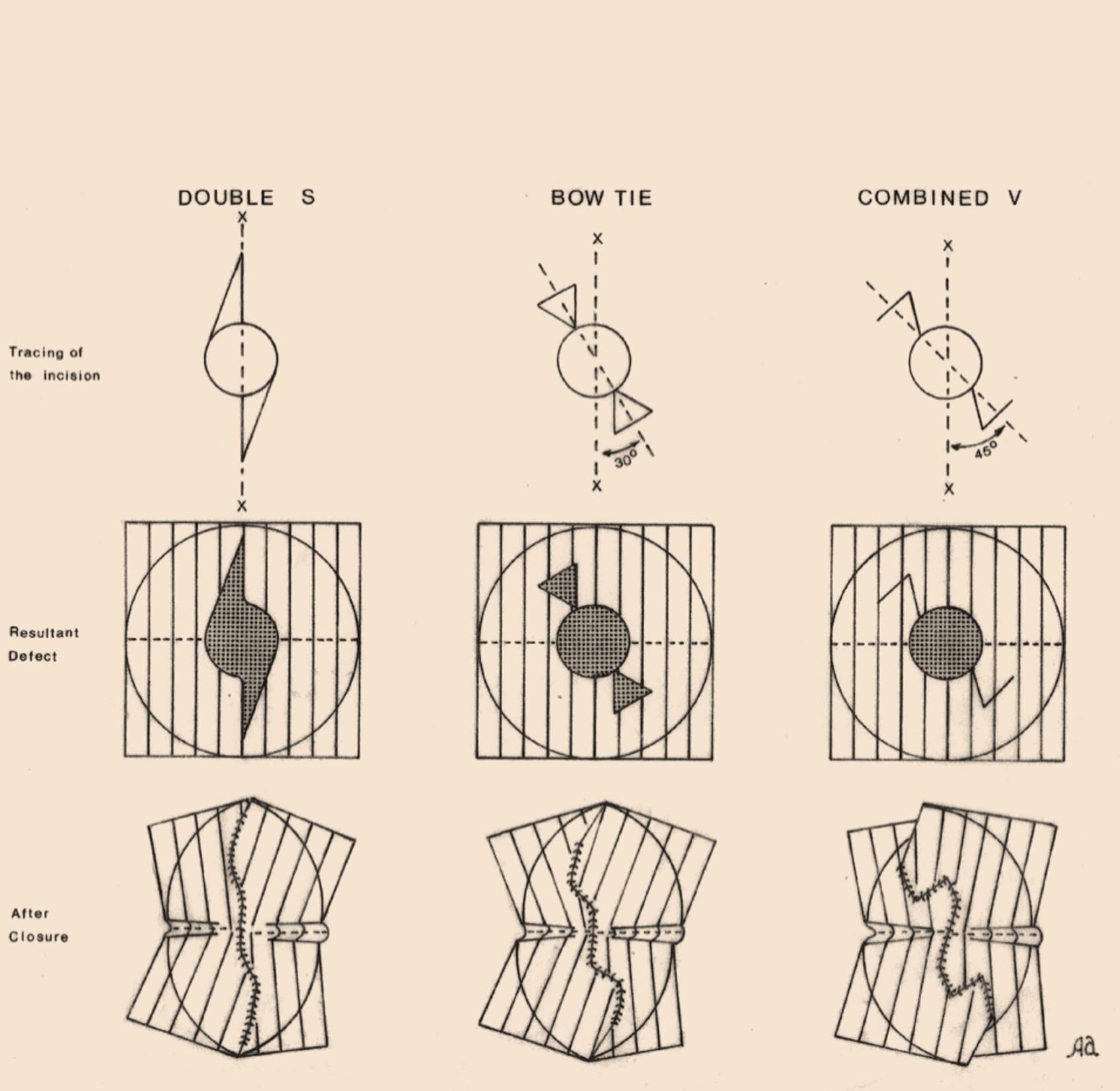

Fig. 3. This figure shows the tracing of the incision, the resultant defect, and the suture line after closure for the double S, bow tie, and combined V incisions.

Note that the axis of these incisions is different in relation to the axis of the minimal tension lines (X–X).

For the bow tie incision, the angle is 30 degrees and for the combined V incision it is 45 degrees.

The suture line of the double S incision has mild curvatures, and the suture line of the combined V incision is more angulated.

However, the distortion of the minimal tension lines is similar for these 3 incisions.

The double S incision is very simple to construct and can be used in many situations where an elliptical incision is indicated but with the advantage of being able to save more sound skin.

If we consider the waste of the skin as the skin excised in addition to the circular defect, the waste for this incision is less than 78% when compared with 156% for the elliptical incision.

The double S incision is useful in small defects of the scalp (less than 1 cm in diameter) and moderate defects of the face (2–3 cm in diameter)

The bow tie incision is very useful when the skin is not quite elastic, such as in small intermediate defects of the scalp (1 to 2cm in diameter), because the waste of sound skin for this incision is 36% only.

The combined V incision is very useful in large defects of the scalp (more than 2cm in diameter) because with this incision there is no wastage of normal skin

For the same reason, it is very useful in very large lesions of the trunk (5–10cm in diameter).

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292188214_Designing_Flaps_for_Closure_ of_Circular_and_Semicircular_Skin_Defects

Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine

McLeod GA, Sadler A, Boezaart A, Sala-Blanch X, Reina MA. Peripheral nerve microanatomy: new insights into possible mechanisms for block success. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Published online October 10, 2024. doi:10.1136/rapm-2024-105721

ABSTRACT

Postmortem histology and in vivo, animal-based ultra-high-definition microultrasound demonstrate a complex array of non-communicating adipose tissue compartments enclosed by fascia. Classic nerve block mechanisms and histology do not consider this tissue Injected local anesthetic agents can occupy any of these adipose compartments, which may explain the significant differences in outcomes such as success rates, onset time, block density, duration of nerve block, and secondary continuous block failure. Furthermore, these adipose tissue compartments may influence injection pressures, making conclusions about needle tip location unreliable. This educational review will explain the neural anatomy associated with these fatty compartments in detail and suggest how they may affect block outcomes

American Journal of Emergency Medicine

Tin D, Granholm F, Helou M. Hybrid warfare tactics and novel injury patterns in the Beirut pager explosions. Am J Emerg Med. Published online November 10, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2024.11.021

On September 17, 2024, a coordinated attack across Lebanon involved the simultaneous detonation of explosives hidden in pagers, which had been modified and triggered by a coded message. Among the many hospitals affected, the Lebanese American University Medical Center (LAUMC) in Beirut received 38 patients, of whom 13 were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. A total of 31 patients required urgent ophthalmic surgeries due to eye trauma (16 unilateral evisceration, 4 bilateral evisceration, 11 “other” eye injuries) a need that had not been anticipated in the hospital's mass casualty planning. The unexpected demand for specialized surgeries underscores how hybrid warfare tactics create injury patterns that strain medical response systems

Greif R, et al. 2024 International consensus on CPR and ECC science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2024;150(24). doi:10.1161/CIR.000001288

This is the eighth annual summary of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations; a more comprehensive review was done in 2020. This latest summary addresses the most recent published resuscitation evidence reviewed by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation task force science experts. Members from 6 International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation task forces have assessed, discussed, and debated the quality of the evidence, using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation criteria, and their statements include consensus treatment recommendations. Insights into the deliberations of the task forces are provided in the Justification and Evidence-toDecision Framework Highlights sections. In addition, the task forces list priority knowledge gaps for further research.

Petersen LB, Bogh SB, Hansen PM, et al. An assessment of long-term complications following prehospital intraosseous access: A nationwide study. Resuscitation. Published online December 5, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2024.110454

Data sources were the nationwide electronic Prehospital Patient Record system, the Danish National Patient Registry, and the Danish Civil Personal Registry. We investigated all patients who were subjected to prehospital intraosseous cannulation in Denmark from January 2016 through December 2019. During a follow-up period of 180 days from the index date we extracted information concerning mortality status and potential long-term complications defined as osteomyelitis, osteonecrosis, or compartment syndrome from the day of prehospital intraosseous cannulation.

Of the 5,387 patients receiving intraosseous access, 375 were unidentified and lost to follow-up. Of the 5012 remaining patients, 4,775 were adults, and 237 were children. No children and "less than five" adults had long-term complications. No osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis or compartment syndrome appeared later than 175 days after an intraosseous cannulation

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-forprofit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries

The College was founded in 2016 and is governed by a Board of Regents supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority License No 2018-022

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments

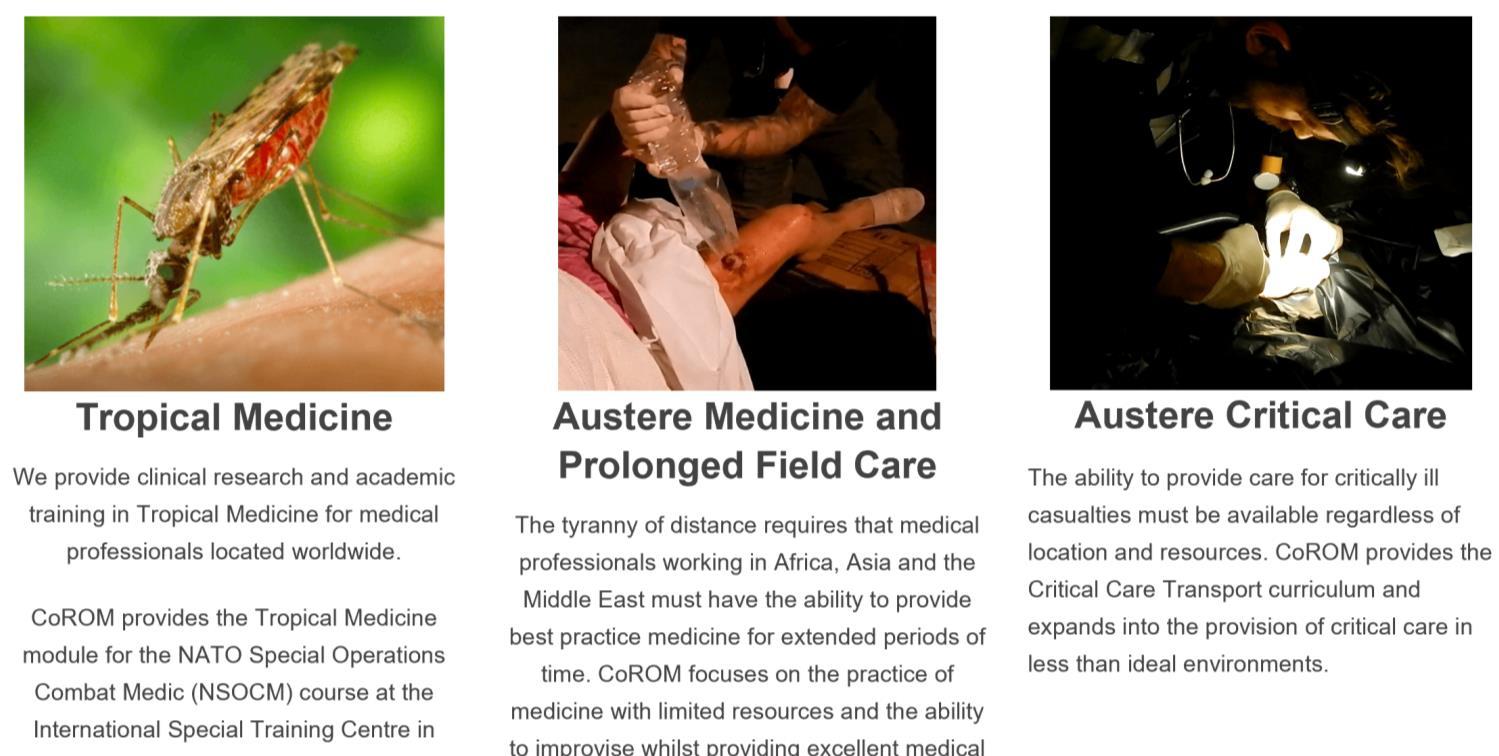

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources.

CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

MFSLR Dates TBD

AEC Dates TBD

Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

SOMSA Conference 5-9 May 2025

Tactical Medicine Review (Clark, HolmstrØm)

Improvised Medicine (O’Kelly, Mallinson, Shertz, Loos)

Austere Clinical Laboratory Diagnosis (O’Kelly)

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice Doctor of Health Studies

Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Award in Tropical & Expedition Medicine

Online

Critical Care Transport

Basics of Resource Limited Critical Care

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro Ghana National Ambulance Service

17-21 Feb 2025 APUS 22-23 Feb 2025

24-28 Feb 2025

7-12 April 2025

BSc RPP/Y1 module 12-31 May 2025

AREMT 8-13 Sept 2025

BSc RPP/Y1 module 27 Oct-15 Nov 2025

ACC

Clinical Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

Acute Critical Care

AEC Austere Emergency Care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

AREMT Award in Remote Emergency Medical Technician

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

Medicine in the Mediterranean 2024 was a resounding success!

Huge thanks to all attendees and the fantastic group of speakers and faculty who made it all possible! We’re making plans for MiM 2025 –please join us.

Call for Speakers:

The Medicine in the Mediterranean Conference, sponsored by the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine, is seeking dynamic speakers to present on topics related to prehospital, remote EMT, and austere medicine. The conference will take place from January 31st to February 2nd, 2025, near the historic city of Valletta, Malta. We are inviting passionate experts in wilderness prehospital care, remote paramedic practice, and austere medicine to share their knowledge and experiences with our diverse audience. Presentations should be engaging, current, and approximately 1 hour in length.

If you are a leader in your field and have valuable insights to offer in these areas, we encourage you to submit your proposal to be a speaker at our conference. This is an excellent opportunity to connect with fellow professionals, exchange ideas, and contribute to the advancement of prehospital and remote medical care.

Submission Guidelines:

– Presentation topics should focus on wilderness prehospital care, remote EMT practices, or austere medicine.

– Proposals should include a brief description of the presentation, outlining key points and learning objectives.

– Speakers must be able to deliver engaging and informative presentations that cater to a diverse audience.

– Presentations should be approximately 1 hour in length, including time for Q&A.

Important Dates:

– Submission Deadline: 1 August 2024

– Notification of Acceptance: 15 September 2024

Please submit your proposal and your CV along with any inquiries to info@corom.edu.mt with the subject line to include “MiM Presentation Idea” by the submission deadline. We look forward to receiving your submissions and welcoming you to the Medicine in the Mediterranean Conference in Sliema, Malta!

Mission to Heal goes where medical need is greatest. We visit remote regions to teach basic surgical skills to local healthcare practitioners so they can care for their community year-round. Due to our educational approach, we need a variety of expertise on these missions. We welcome the following specialists to volunteer with us:

Nurse Anesthetists

Tropical Medicine Specialists

Obstetricians & Gynecologists

Optometrists & Ophthalmologists

Dentists & Oral Surgeons

General Surgeons

OR Nurses

Triage Nurses

Medical & Dental Students

Residents

As you can see, it’s a wide-ranging list – but it’s not all inclusive. If you have a specialty that’s not listed here, but would love to volunteer with us, there is still a place for you! Why volunteer?

- Get a transformational learning experience where you learn just as much as you teach. - Experience a culture outside of your own.

- Experience how healthcare is practiced in other countries.

- Use your expertise to benefit the less fortunate.

As one of our volunteers said to us, “We want to volunteer with you because you actually do.”

Useful links:

Volunteer with Mission to Heal - https://missiontoheal.org/apply/ Volunteer FAQ’s - https://missiontoheal.org/faqs/ Our approach to missions - https://missiontoheal.org/approach/ Volunteer reflections - https://missiontoheal.org/blog/ Questions about M2H missions – samuel.jangala@missiontoheal.org

2025 Missions:

Kenya I February 7-23

Kenya II April 11-27

Kenya III June 13-29

Kenya IV August 8-24

https://www.masteryourmedics.com/pages/fastcanada2025

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

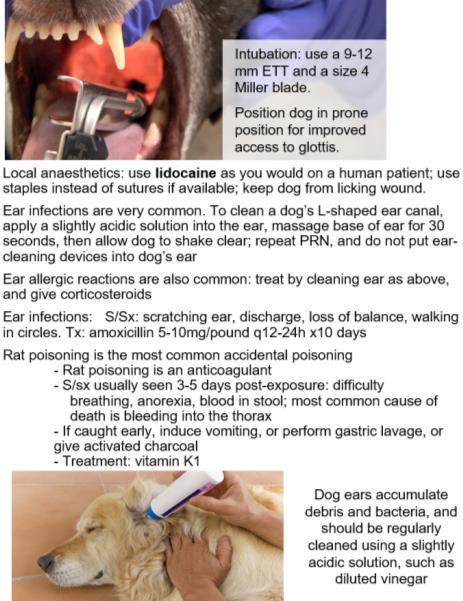

Canine medicine

…and much more!