At the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine (CoROM), we are driven by a commitment to empower medical professionals working in remote, austere, and challenging environments. As we look ahead, I encourage all of you whether current students, alumni, or prospective learners to take this moment to plan for your future. The time is now.

John Clark JD MBA NRP

Applications are open for our September semester, and we are excited to welcome new cohorts into several of our flagship academic programmes. The newly revised Master’s in Global Health and Leadership has been carefully updated to meet the evolving needs of healthcare professionals aiming to drive meaningful change on a global scale. Our Doctorate in Health Sciences provides a rigorous, researchinformed pathway for those ready to contribute at the highest level of academic and professional practice. And the Bachelor in Remote Paramedic Practice continues to offer an exceptional foundation for practitioners seeking to work at the sharp end of pre-hospital care.

If you are considering advancing your career, now is the perfect time to apply. The Master’s in Austere Critical Care remains our only programme that accepts students on a rolling basis, but for all other programmes, securing your place for the autumn semester ensures you can begin the next stage of your professional journey without delay. CoROM offers fantastic education at an affordable price, with flexible learning designed to suit the demands of working healthcare providers around the world.

While you are planning ahead, I also urge you to mark your calendars for an event not to be missed: the Medicine in the Mediterranean Conference (MiM26). Taking place 30 January to 1 February 2026 in Sliema, Malta, this conference promises to be a landmark gathering of experts, practitioners, and thought leaders in austere, remote, and pre-hospital medicine. MiM26 will coincide with a special occasion the 10th anniversary of CoROM. It will be a time not only to share knowledge and innovation but also to celebrate a decade of advancing medical education and practice in some of the world’s most challenging settings.

I invite you to take charge of your future today. Apply for our academic programmes, set your professional goals, and make plans to join us in Malta for MiM26. Together, we can continue to shape the future of healthcare in remote and austere environments.

The time is now. Let’s move forward together.

Summertime is upon those of us residing in the northern hemisphere, and, in the spirit of the season, I am pleased to introduce a new regular feature entitled On the Shoulders of Giants

The Compass has been long overdue for a “hero” section, and this inaugural edition features none other than Louis Pasteur. While the sentiment “we stand on the shoulders of giants” is among the most widely-invoked cliches, its popularity makes it no less true. In a time when medical science is under unjust attack, it is apropos to hearken back to the 19th century, a golden age of scientific discovery during which Pasteur developed the germ theory of disease, invented pasteurization, and created vaccines for rabies and anthrax.

In this issue, we present a pair of double features: two fascinating case studies from east Africa, and two clinical pearls writeups from CoROM faculty.

I would like to thank all of the contributors to this edition of The Compass, including Ukrainian Dr. Bohdana Pereviznyk – not only for her bravery in saving lives in a country under siege, but also for her recommendation of the first piece of medical literature found in this issue’s Journal Watch section.

For those of you traveling to Malta for October short courses, I look forward there!

Jason 1 July 2025

Jason Jarvis is a paramedic and former U S Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated in countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq, and Afghanistan He is a freelance medical educator who teaches for CoROM, the U N , the U S Department of Defense, Harborview Medical Center, and Seattle Children’s Hospital Jason is a PhD student in Widener University’s Health Professions Education program and holds a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Kibosho Hospital, 2025

An elderly female patient presented to the Kibosho Hospital emergency department accompanied by her family members. They said that she had been feeling unwell for the past few days and eventually began experiencing difficulty breathing, prompting them to bring her to the hospital. Since this was a district hospital located in a smaller village, there was no access to emergency medical services or formal transport, so the family brought her to the hospital themselves in a small three-wheeled vehicle.

Capt Mason Leschyna

Unlike in North America, she was not received at the hospital entrance by staff. Instead, the family borrowed a wheelchair from the hospital, transferred her onto it themselves, and brought her to the emergency department. She waited in the hallway for quite some time before any vital signs were obtained or a doctor was available to assess her. When I first saw her, I recognized that she was significantly tachypneic and hyperpneic. Despite this, she waited calmly in line alongside the other patients awaiting their turn to see the physician. When it was her turn, she was brought by the physician into the consultation room.

Given the relatively small team at the hospital, it was up to the family to transition the patient from the wheelchair to the stretcher. We then began collecting a set of vital signs. Although the patient looked uncomfortable, she did not appear to be in complete respiratory failure or peri arrest. To my surprise, however, when we checked her vital signs, we found her to have an oxygen saturation in the sixties and a systolic blood pressure in the seventies. This was quite shocking to me as such findings are not common in North America, and certainly not among those who were brought to the hospital by private vehicle or those sitting in the waiting room for some time! Moreover, when we have patients with these findings, they're deemed an emergent priority and whisked away to the resuscitation room where they are promptly started on oxygen and IV fluids.

Here, however, there was not the same sense of urgency to which I was accustomed The doctor calmly spoke with the family, carefully examined the patient and recorded her vital signs He then proceeded to explore the history of presenting illness in greater detail before initiating any treatment Eventually, after several minutes of assessment, he discussed with the family that the patient would need supportive care, including IV fluids for her blood pressure and supplemental oxygen for her hypoxemic respiratory failure Unfortunately, however, this hospital did not have a large supply of these, and it was the responsibility of the patient's family to obtain the supplies that the hospital did not have stocked

Therefore, the patient stayed in the emergency department as the family went off to the local pharmacy to obtain bags of IV fluids It took the family about 45 minutes to an hour to obtain these supplies All the while, the patient sat on a stretcher breathing and awake but with saturations in the sixties and blood pressure in the seventies At the time, this was quite uncomfortable for me to observe I had always been trained that when we saw numbers like this we should move very quickly because this was a life-threatening pathology I had always been taught and had the impression that there was a significant risk of the patient quickly collapsing into cardiac arrest Reflecting upon this case, however, I realized that this patient had been deteriorating over several days

This wasn't a sudden pneumothorax, flail chest, or other sudden injury Rather, it was a gradual process that built up over several days and possibly weeks at home Therefore, she had been sitting at home in this condition for at least several hours or days prior to her presentation to the emergency department! Given this understanding it seems somewhat reasonable that she had already at least partially adapted to these severely abnormal vital signs Although her condition was far from optimal, she had survived long enough to have her family recognize a problem, transport her several hours to the local hospital, and then have her wait in the emergency department Therefore, while she certainly needed urgent medical attention, it was unlikely that an additional few minutes would result in a sudden collapse

When the family arrived back with the requested supplies, we began providing the patient with IV fluid resuscitation as well as supplemental oxygen With this supportive care, her symptoms did improve, and her vital signs returned to a more normal range We then began further investigations including lab work as well as radiography which identified what appeared to be a multifocal pneumonia Blood cultures as well as other infectious markers were sent, and the patient was admitted to the hospital She was also started on empiric antibiotics

Due to the organizational structure and resources available at the hospital, the emergency team also rounded on the most acute inpatients Therefore, we began to follow this patient daily over the next few days of her hospitalization By the following day, the results of her tests had returned showing that this patient had tuberculosis This was another shock to me!

In Canada, I was trained that if there was even the slightest suspicion of tuberculosis, you had to don full airborne precautions with a respirator and place the patient in negative pressure isolation This patient, however, had been sitting in the emergency department hallway and then in a regular ward bed for over 24 hours at this point The doctor also only mentioned this casually after we'd been in the room speaking to the patient for a few minutes on the second day, not wearing a respirator I asked him why he was not concerned about the risk of tuberculosis, and he said that it's quite common in Tanzania for patients to have tuberculosis and that the risk of infection is relatively low given a short period of exposure and a healthy host From then on, us and other staff generally used surgical face masks due to limited availability of respirators He explained that we would transfer the patient into her own separate room Yet, this would not be a negative pressure room with HEPA filters, but rather just a private room to avoid contaminating other patients

The patient began recovering quickly Her oxygen was titrated down, and she was transitioned from an oxygen bottle to an oxygen concentrator The Physician explained to me that they had several oxygen concentrators at the hospital, and this allowed them to provide ongoing oxygen without the cost of buying oxygen I was surprised at how quickly they transitioned her to the oxygen concentrator The physician was willing to accept oxygen saturations in the mid to high eighties if this meant moving from expensive bottled oxygen to inexpensive concentrated oxygen He explained that the family had limited means, and the hospital could not afford to cover additional medical supplies

Therefore, this was the best compromise given the resource limited situation The patient continued to improve with appropriate therapy and was eventually discharged home to the care for family Unlike North America there was no contact tracing or follow up for the tuberculosis because this was such a common presentation that it would be nearly impossible to isolate the individuals Patients were treated symptomatically when they presented and isolated as best they could while they underwent treatment with typical therapy It was, however, certainly a different experience to what would have happened had this patient presented to the hospital in North America where I work This case really made me reflect on how we approach situations in North America and how much of what we do is based on dogma and assumptions rather than evidence

Hospital, Tanzania

The main things that I reflected up on about this case were related to the urgency with which problems were addressed There is a saying that if something happened quickly you should fix it quickly We try to follow this saying in medicine for issues related to electrolyte imbalances and other metabolic problems When it comes to vital signs, however, we often don't take this approach It's interesting to consider that the body can adapt to quite extreme states, whether that is a sodium of 115 mEq/L or oxygen saturations of 75% This was demonstrated in how some COVID patients who were severely hypoxemic with oxygen saturations previous thought to be unsurvivable were in fact quite comfortable Moreover, we learned with time that excessive intervention to address these numbers with intubation may have worsened outcomes This experience led me to recognize that considering the patient's clinical presentation may perhaps be more important than adhering to specific numbers While this lady had very concerning vital signs upon presentation, when you looked at her, her level of distress did not match what I would have expected given those vital signs It therefore makes sense to consider the vital signs and treat them, but consider urgency based on the patient's presentation A patient who has an oxygen saturation in the eighties from a sudden presentation, is in severe respiratory distress, and unable to speak even single words, is very different from someone who has saturations in the sixties due to a gradual presentation of their illness and is in mild to moderate distress but is still able to carry on a full conversation

One of the most surprising things about this case was the hypoxemia of the patient I had always been taught and assumed that patients with a situation below 80 were critically ill and on the verge of cardiovascular collapse (Tintinalli et al , 2019; Walls et al , 2022) Both this case and those during COVID, however, have brought to light the concept of silent hypoxemia Upon doing further research, this is not a new phenomenon solely related to COVID, but rather one that was always present but relatively unfamiliar to most physicians (Kallet, Branson & Lipnick, 2022) Silent hypoxemia, sometimes called happy hypoxemia, is a condition in which patients are profoundly hypoxemic via pulse oximetry as well as possibly arterial oxygen pressure but do not display significant respiratory distress clinically

The primary finding in silent hypoxemia is hypoxemia with minimal respiratory distress, especially when compared to the degree of respiratory distress as is prominent in most other people with respiratory failure and similar saturation readings It seems that this is common among both COVID as well as other forms of pneumonia, although perhaps under-reported (Ribeiro et al , 2022) Another place in which this can present is in high altitude medicine or areas where patients are exposed to a hypoxic or hypobaric environment (Tintinalli et al , 2019; Walls et al , 2022) Numerous literature reviews have demonstrated this presentation in COVID, although often in the early stages which eventually progresses to more severe respiratory failure

The most likely explanation for this presentation relates to the pathophysiology and physiology of both respiratory distress and dyspnea In most healthy adults, the primary driver of respiratory effort and rate is related to carbon dioxide levels as well as acid base balance Both acidosis and hypercapnia have been demonstrated to have a strong impact on respiratory effort and respiratory drive Hypoxemia, on the other hand, has demonstrated a relatively weak correlation with respiratory drive That is to say that patients who are hypoxemic but not hypercapnic nor acidic and, even more so, patients who are hypoxemic but hypocapnic and alkalotic have minimal if any increase in respiratory drive (Dhont et al , 2020; Kallet, Branson & Lipnick, 2022)

The sensation of dyspnea, rather than relating to actual hypoxia as is often presumed in medicine, relates more so to a mismatch between respiratory effort and ventilatory effectiveness Therefore, a patient whose pathology primarily causes hypoxemia without hypercapnia or acidemia may not experience the mismatch between ventilatory effort and hypercapnia which is perceived subjectively as dyspnea When a pathology results in low oxygen saturations but still permits ventilation, the patient often experiences little subjective distress Moreover, additional factors can contribute to this apparent mismatch between the clinical impression and the oxygen saturation including things such as fever and previous adaptation (Ora et al , 2021)

This patient, being ill with an infection and febrile may have shifted the oxygen hemoglobin dissociation curve to the right As well, having lived at altitude for all her life she may have been relatively accustomed to mild hypoxemia Therefore, until the disease progressed resulting in hypercapnia, the relative hypoxia and hypoxemia may have been insufficient to trigger severe symptoms of respiratory distress despite the concerningly low saturations The important thing to take away from this case is that while we often assume in medicine that hypoxia and hypoxemia are the main driving factor behind dyspnea and respiratory distress, it is often actually hypercapnia and acidemia driving this The reason for this misunderstanding likely relates to the availability heuristic We have easier access to pulse oximetry than to capnography and when a patient is in respiratory distress the first thing we check is their oxygen saturation Moreover, we tend to focus on this since we can immediately fix it by providing supplemental oxygenation Therefore, we fixate on the oxygen saturation rather than the more difficult to measure and manage hypercapnia and acidemia which are often the true driving forces of dyspnea

Oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve. Image credit: Life in the Fast Lane

Another surprising element of care for this patient was the infection control procedures, or rather lack thereof, compared to what I was used to in North America In North America, patients with any suspicion for tuberculosis are immediately placed in negative pressure isolation rooms and all staff entering or leaving are expected to don full airborne respiratory precautions including a respirator after undergoing a formal fit-test procedure (Tintinalli et al , 2019; Walls et al , 2022) This patient who had confirmed tuberculosis with a productive cough and respiratory symptoms, however, was simply placed in a private room The doctor would occasionally wear a simple face mask but never once an N95 respirator I initially suspected that this was related to the resource-limited nature of the hospital; however, surprisingly the evidence on many of the techniques emphasize so strongly in the west is quite limited (Anon, n d )

For example, the best evidence from the World Health Organization recommends natural ventilation as the preferred ventilation mechanism in resource limited settings (World Health Organization, 2019) They suspect that natural ventilation is likely as effective as mechanical ventilation in the best-case scenario and is much more robust and less susceptible to failure Looking back, this is exactly what was done The patient was placed in an individual room and the windows were opened with the door closed, allowing natural ventilation of the room I was very surprised to learn this was the recommended technique despite the emphasis on mechanical ventilation and HEPA filtration in North America

Personal protective equipment was also highly emphasized in North America; however, once again the evidence in support of this is quite scant (World Health Organization, 2019) There is some weak evidence that using properly fit-tested respirators in the most infectious period of tuberculosis does marginally reduce transmission (Azeredo et al , 2020) Guidelines emphasize, however, that tuberculosis rapidly decreases in infectivity as soon as treatment is started (World Health Organization, 2019) Therefore, the most important intervention to prevent spread is early initiation of treatment which occurred in this case In fact, due to the high prevalence and suspicion, treatment was likely initiated much sooner than it would have been in a North American facility Interesting, masking is only recommended in a healthcare setting and, if patients are well enough to return home, many guidelines recommend that they be treated as outpatient (Anon, n d ) They do not recommend respiratory precautions for family members but instead focus on contact tracing and treatment as appropriate

It seems that in the West we expend many resources on tuberculosis infection control despite our relatively low prevalence of the disease and the marginal efficacy of these interventions (McCreesh et al , 2021) While they no doubt have some impact, this is likely relatively small In a significantly resource constrained environment with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, the evidence supports a focus on natural ventilation and isolation which are the most effective as well as the most cost-effective mechanisms of transmission reduction The lack of mechanical ventilation does not appear to be a hinderance based on this evidence and the lack of airborne precautions with respirators is likely due to the minimal efficacy relative to the cost in a resource limited setting combined with the low contact time with the patients

This case served to highlight the differences in practice between a high resource setting in a developed country such as North America and a low resource setting such as Kibosho Hospital in Tanzania Prior to my time in Tanzania, I had a relatively biased view of healthcare in that I suspected high resource settings provided much higher quality of care and were the ones best able to follow evidence-based guidelines Reflecting on this case, however, I realize that low resource settings are able provide excellent quality care if they have a dedicated team focused on evidence-based medicine As well, the differences in a high resource setting often come at an extremely high cost with a relatively marginal improvement in outcomes versus these possible at a much lower cost in lower resource settings Moreover, I realize that many of the things we do in a high resource setting are based in dogma and not always based on solid evidence I truly enjoyed my time at Kibosho Hospital working with the many talented doctors there I've learned countless things including the importance of focusing on clinical presentation rather than simply numbers as well as the importance of prioritising high impact interventions in a low resource setting so you can have the maximum impact for the minimal cost This experience has truly opened my eyes to global healthcare, particularly how to provide high quality healthcare in a low resource setting with minimal compromise I am extremely gratefully for my time at Kibosho and all those who were so welcoming and taught me so much

Anteroposterior chest X-ray showing a case of advanced bilateral pulmonary TB. The white triangles indicate pulmonary infiltrates, while the black arrows indicate caving formation. Image credit: Wikipedia

Anon (n.d.) Tuberculosis: Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Tuberculosis, and Measures for Its Prevention and Control.

Azeredo, A.C.V., Holler, S.R., de Almeida, E.G.C., Cionek, O.A.G.D., Loureiro, M.M., Freitas, A.A., Anton, C., Machado, F.D., Filho, F.F.D. & Silva, D.R. (2020) Tuberculosis in Health Care Workers and the Impact of Implementation of Hospital Infection-Control Measures. Workplace health & safety. 68 (11), 519–525. doi:10.1177/2165079920919133.

Dhont, S., Derom, E., Van Braeckel, E., Depuydt, P. & Lambrecht, B.N. (2020) The pathophysiology of ‘happy’ hypoxemia in COVID-19. Respiratory research. 21 (1), 198. doi:10.1186/s12931-020-01462-5.

Kallet, R.H., Branson, R.D. & Lipnick, M.S. (2022) Respiratory Drive, Dyspnea, and Silent Hypoxemia: A Physiological Review in the Context of COVID-19. Respiratory care. 67 (10), 1343–1360. doi:10.4187/respcare.10075.

McCreesh, N., Karat, A.S., Baisley, K., Diaconu, K., Bozzani, F., Govender, I., Beckwith, P., Yates, T.A., Deol, A.K., Houben, R.M.G.J., Kielmann, K., White, R.G. & Grant, A.D. (2021) Modelling the effect of infection prevention and control measures on rate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission to clinic attendees in primary health clinics in South Africa. BMJ global health. 6 (10). doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021 007124.

Ora, J., Rogliani, P., Dauri, M. & O’Donnell, D. (2021) Happy hypoxemia, or blunted ventilation? Respiratory research. 22 (1), 4. doi:10.1186/s12931-020-01604-9.

Ribeiro, A., Mendonça, M., Sabina Sousa, C., Trigueiro Barbosa, M. & Morais-Almeida, M. (2022) Prevalence, Presentation and Outcomes of Silent Hypoxemia in COVID-19. Clinical medicine insights. Circulatory, respiratory and pulmonary medicine. 16, 11795484221082760. doi:10.1177/11795484221082761.

Tintinalli, J., Ma, J., Yealy, D., Meckler, G., Stapczynski, J.S., Cline, D. & Thomas, S. (2019) Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine. 9th edition. McGraw Hill / Medical.

Walls, R., Hockberger, R., Gausche-Hill, M., Erickson, T. & Wilcox, S. (2022) Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 10th edition. Elsevier Canada.

World Health Organization (2019) WHO guidelines on tuberculosis infection prevention and control: 2019 update .

Mason Leschyna currently works clinically as an Emergency Physician at multiple hospitals in Ontario, Canada. He also serves as a Trauma Team Leader and Critical Care Associate at the regional trauma center As well, he serves in the Canadian Armed Forces Reserves as a Medical Officer at the rank of Captain He recently completed a tasking at CFS Alert, the Northern-most continuously inhabited place in the world He is also a member of the Canadian Forces Disaster Assistance Response Team. His clinical interest is in quality management and austere medicine He has completed his Diploma in Dive and Marine Medicine and is currently an MSc Candidate at COROM pursuing a degree in Austere Critical Care

Kibosho Hospital, Tanzania

In the middle of our Mission to Heal (M2H) tutorial discussions on thyroid disorders, the local Rendille Liaison Daniel came in to report that our driver Abdi had just been “bit by a scorpion.” For the precision use of language, I am compelled to point out that scorpions do not “bite” but “sting. ”

Glenn Geelhoed AB, BS, MD, MA, DTMH, MPH, MA, FACS

Abdi had tried to open the window in his "gab" (the low-profile domed hut that is wind resistant in the perpetual winds of the Great Rift Valley, particularly here in the Korr Desert) when he felt a sharp pain in the thenar eminence (the base of his left thumb.) The hand swelled up immediately, and we brought him into our tutorial as I thanked him for volunteering to serve as the model for this component of the teaching of tomorrow’s full tutorial on “Bites and Stings, Snakes and Venomous Critters and Their Management.”

He hurt. The venom produces a rapid swelling from the immediate histamine response, and as if the sting itself is not bad enough, the “compartment syndrome” that follows from the tight swelling makes it worse. Here is the teaching point, since we are able to make someone immediately better by what might seem an excruciating treatment. We inject lidocaine into the already tightly swollen compartment of the thumb pad. Kristen Alcorn, our M2H nurse practitioner, had the kit already prepared from the local anesthetic kits I had brought from home, one of the few supplies I had carried in for this trip, since there was half a hope that the M2H MSU operating room unit might be ready for our use on this mission into the Korr Desert where no such OR or supply chain exists.

The biochemistry lesson here relates to the depolarizing action of local anesthetics, the “-caine” drug derivatives The end of the molecule that makes it anesthetic is a “quaternary nitrogen” end, the opposite end of the carboxyl terminus, that contains the weak alkaline acid/base structure of “NH4 ” an alkaline moiety That means that this end of the molecule is basic and neutralizes weak acids The two-fold action of the local anesthetic injection is 1) anesthetic – immediate pain relief from the depolarization numbing of the innervation – depolarizing the nerve to block the sensations, and 2) neutralization of the weak acid venom

Abdi was immediately relieved, and was ready to drive over to pick up Peter, our psychologic counselor to contribute to the later patient presentation This also got a good start on the tutorial topic for tomorrow on the venomous snakes and other toxic creatures in Africa, with a case report by Rose on a young mother of a fourmonth-old who was brought in late after an alleged puff adder bite, but seemed to have succumbed to a hemotoxic venom just three weeks ago here at the Korr Health Center

The sting of a scorpion is treated principally as a local envenomation and rarely gets to the point of systemic complications in an adult-size patient, whereas the envenomation from toxic snakes is often treated both at the local envenomation site and systemically for 1) neurotoxic, (e g , cobra or mamba) 2) hemotoxic, (e g vipers) or 3) histolytic (e g , puff adders) complications depending on the species of the venomous snake, often employing transient venous tourniquets and

Dr. Glenn Geelhoed received his BS and AB cum laude from Calvin College and MD cum laude from the University of Michigan. He completed his surgical internship and residency through Harvard University at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital Medical Center. To assist in developing further volunteer surgical services in underserved areas of the developing world, Glenn completed master's degrees in international affairs, epidemiology, health promotion and disease prevention, anthropology, and a philosophy degree in human sciences.

He still works as a professor of surgery at George Washington University Medical Center in Washington D.C. and is a member of numerous medical, surgical, and international academic societies. Glenn is an avid game hunter and runner. He has completed more than 135 marathons across the globe. He is also a widely published author accredited with several books and more than 500 published journal articles and chapters in books. He has two sons and five grandchildren.

Ice-pick headache (Stabbing headache)

A fairly rare headache syndrome characterized by very brief stabs of recurrent and focal head pain Often occurs in people with other headache syndromes, perhaps due to spontaneous firing of individual nerve fibres which have been sensitised by recurrent activation

Sex-induced headache (Coital cephalalgia)

Tom Mallinson

BSc (Hons) MBChB

PGCHE DipMSK (FSEM) MRCGP (2020) MCPara

MCoROM DFSEM (UK) FHEA FFRRHHEd FAWM FRGS

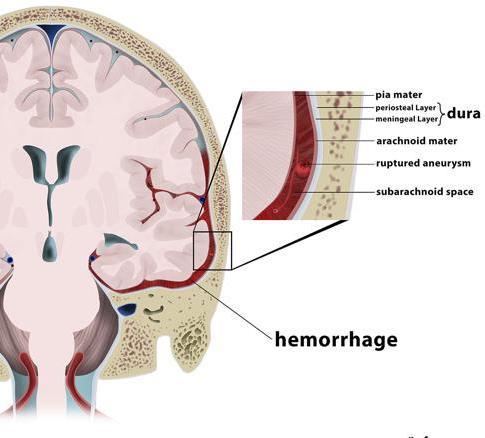

Usually benign and peri-orgasmal Pre-orgasmic is often a dull ache, while orgasmic is more severe May be first presentation of a subarachnoid bleed

Thunderclap headache

May be due to subarachnoid haemorrhage or one of the reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes Requires urgent investigation

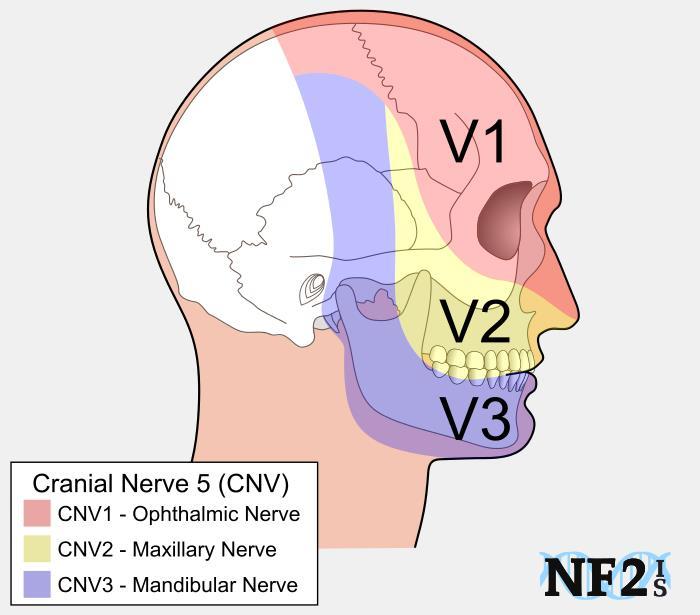

Eating cold food stimulates a severe but short-lasting headache, likely due to vascular constriction and subsequent dilation with stimulation of the trigeminal nerve.

Image credit: NF2IS.org

Said to occur in response to the nitrates/nitrites used to preserve foods such as hotdogs, bacon etc.

Taking preventive measures before departure is crucial for minimising dental issues during an expedition:

Burjor Langdana MDS FDSRCS NZDREX FEWM

Schedule a comprehensive dental examination, including necessary X-rays. Request a copy of your dental chart/records.

Complete any outstanding dental treatments to allow adequate healing and settling time. Focus on reinforcing excellent oral hygiene habits, including the use of highfluoride toothpaste and adopting the "spit, don't rinse" method after brushing to maximize fluoride's protective effect.

Dental emergencies generally fall into two categories: dental/oral pain (like toothache or infection) and dental trauma (such as injuries).

Patient Complaint Likely Diagnosis

Brief, sharp pain (seconds) from hot/cold, stops when removed

Visible hole or decay in tooth

Dentine Hypersensitivity

Description / Likely Cause Likely Recent History

Exposed dentine reacting to stimuli. Minor gum recession, toothbrush abrasion, cold weather

Dental Caries / Decay Bacterial destruction of tooth structure.

Visible decay developing.

Loose or broken filling Loose / Broken Filling Failure of existing restoration. Filling recently damaged or worn.

Pain on biting, potentially sharp edge, tooth feels weak

Short twinges from hot, cold, or sweet; increasing discomfort

Twinges developing into aching pain lasting several minutes

Severe, poorly localized pain, worse with heat, disrupts sleep, often eased by cold

Recent severe pain (hot/cold/sweet), now NO symptoms

Pulsing, continual toothache, worse lying down, tooth may feel 'high' & tender to touch/tap (percussion)

Pulsing toothache lessening as swelling appears, becomes fluctuant (soft/pusfilled), discharges pus

Cracked Cusp / Cracked Tooth

Reversible Mild Pulpitis

Reversible Pulpitis

Fracture line in tooth structure, often from biting forces.

Early inflammation of the dental pulp.

Moderate inflammation of the dental pulp.

Irreversible Pulpitis Severe inflammation, pulp tissue dying.

Sterile Non-Vital Pulp

Periapical Abscess (Early/Acute)

Dental pulp has become necrotic (died) but without infection/abscess symptoms yet.

Necrotic, infected pulp; infection spreading to tissues/bone around tooth root. Tooth tender to percussion.

Periapical Abscess (Draining/Fluctuant) Necrotic, infected pulp; well-formed abscess at root tip, may be draining. Tooth very tender to percussion.

Swollen, bleeding gums Gingivitis

Swelling, redness, and pain in the gum tissue (not necessarily linked to one tooth's root)

Painful bleeding, swollen gums around wisdom teeth, bad taste, limited opening (trismus), maybe facial swelling

Painful, bleeding, ulcerated gums with bad breath/taste

Rapid onset ache, radiating facial pain (ear/temple/eye), facial swelling, swollen lymph nodes, fever.

MEDICAL EMERGENCY:

Rapidly spreading infection, difficulty opening mouth/ swallowing/breathing, swelling below jaw/ tongue or around eye.

Jaw joint pain or clicking, may follow stress or clenching

Gum Abscess (Periodontal/Gingival)

Plaque build-up around gum margins causing inflammation.

Recent trauma or heavy biting force.

Lost/broken filling, cracked tooth, new decay

Ongoing sensitivity to hot, cold, or sweet

Long history of sensitivity, now severe pain

Long history of sensitivity; pain has now subsided.

Dental symptoms sometime in the past. Recent immune system upset.

Recent continual aching toothache, swelling developed.

Poor oral hygiene regimen recently.

Infection within the gum pocket/tissue. Acute gum infection.

Pericoronitis Food/plaque trapped under gum flap (operculum) over a partially erupted tooth (usually wisdom tooth), causing infection.

ANUG (Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis)

Spreading Facial Swelling (Periapical Abscess vs Periodontal Abscess)

Spreading Facial/Neck Infection (Cellulitis / Ludwig's Angina / Orbital Cellulitis)

Aggressive bacterial infection causing tissue necrosis.

Periapical: From chronic abscess/ granuloma. Periodontal: From deep

Partially erupted wisdom tooth, recent poor oral hygiene.

Plausible Previous History

Aggressive brushing, history of gum disease

History of untreated dental problems, sugary diet, poor OH.

Tooth has previous fillings.

Hx of dental work (esp. large fillings), grinding, or weakened tooth structure.

Previous tooth damage, minor injury, lack of recent dental care

History of untreated dental problems

Untreated decay likely reaching the pulp

Known untreated damage, large/deep fillings, crowns, fillings near pulp, past trauma.

De-vitalising tooth (trauma, deep filling, crown), failed previous root canal therapy.

De-vitalising tooth (trauma, deep filling, crown), failed previous root canal therapy.

Sub-optimal brushing, lack of interproximal cleaning. Exacerbated by smoking.

History of gum infection or untreated gum disease (periodontitis).

Previous episodes of pericoronitis.

Management / What to Do

Use desensitizing toothpaste; apply fluoride varnish (e.g., Duraphat) to exposed dentine areas.

Clear visible decay, place a temporary filling to seal the cavity. Consider NSAIDs for pain relief if needed. Requires definitive filling later.

Remove loose or broken filling material. Place a temporary filling. Requires replacement filling later.

Place a temporary filling covering the tooth, possibly slightly raised ('high') in the bite to reduce pressure on crack. Use NSAIDs. Be aware of possible abscess/pulpitis if crack reaches pulp. Requires definitive restoration (crown) or extraction.

Avoid trigger stimuli. Clear visible decay if present. Place a temporary filling to cover/insulate the area. Consider pain relief (NSAIDs).

Clear visible decay. Seal the damaged area with a temporary filling. Apply a sedative dressing (e.g., Ledermix, clove oil). Use NSAIDs. Antibiotics may be considered.

Definitive: Root canal therapy or extraction. Palliative/Field: Clear obvious decay, place sedative dressing (e.g., Ledermix, clove oil) + cotton pellet, cover with temporary filling. Consider local anaesthetic. Prescribe antibiotics & NSAIDs.

Place sedative dressing (Ledermix) + cotton pellet in cavity, cover with temporary filling to prevent bacterial ingress. Requires definitive follow-up (RCT or extraction).

Give NSAIDs & antibiotics. If open cavity, leave open for drainage. Advise patient requires definitive dental treatment (Root Canal Therapy or Extraction).

Incise and drain fluctuant swelling if present & safe. Give NSAIDs & antibiotics. Advise patient requires definitive dental treatment (Root Canal Therapy or Extraction).

Reversible. Improve oral hygiene: brush 2x daily (2 mins), daily interproximal cleaning (floss/TePe). Chlorhexidine 0.2% mouthwash daily (max 2 weeks). Discuss OH importance.

Irrigate under the gum edge with chlorhexidine. Scrape the gum pocket (curettage) to encourage drainage if feasible. Prescribe antibiotics & NSAIDs.

Thoroughly clean under gum flap, flush with chlorhexidine 0.2% or saltwater (syringe helpful). Improve OH. Use NSAIDs. Prescribe antibiotics if severe or not resolving.

Rapid onset of symptoms.

History of serious dental treatment/trauma, or gum disease.

Associated w/ stress, poor dental hygiene, weakened immune system, smoking.

Periapical: Past trauma, failed RCT, non-vital tooth. Periodontal: Long-

Use chlorhexidine mouthwash. Prescribe antibiotics (Metronidazole is often the first choice). Gentle cleaning. Pain relief (NSAIDs). High protein diet, increase fluid intake. Control dehydration. Stop smoking.

Serious Infection. Incise and drain fluctuant swelling if present & safe. Give NSAIDs & antibiotics. Requires definitive treatment (RCT/extraction for periapical; extraction/periodontal therapy for periodontal).

TMJ Pain / Disorder

IMMEDIATE HOSPITAL REFERRAL / MEDIVAC. High dose IV Amoxiclav +/Metronidazole). Surgical drainage likely required. Extract offending tooth if possible. Monitor airway closely. Rule out

Use NSAIDs for pain relief. Soft diet. Avoid clenching. May need

Emergency care for dental injuries depends on the specific type of trauma sustained For all dental injuries, providing pain relief (analgesia), recommending a soft diet, ensuring careful oral hygiene (including chlorhexidine mouthwash if available), and advising follow-up dental investigation upon return are essential baseline measures

Description

Minor impact; tooth painful but not loose; no bleeding at gum line.

Minor impact; tooth loose (mobile) in socket; moderate pain; bleeding at gum line.

Moderate impact; tooth partially pushed out of socket; very loose; moderate pain; significant gum bleeding.

Severe impact; tooth pushed sideways, forward, or backward (often feels stuck/non-mobile); pain; significant bleeding.

Severe impact; tooth pushed upwards into the gum/bone; appears shorter; pain.

Tooth completely knocked out of socket; significant bleeding.

Injury Type

Concussion

Subluxation

Extrusion

Lateral Luxation

Intrusion

Avulsion

Part of the tooth is broken off.

Tooth Fracture

Immediate Management

Usually, no immediate treatment needed besides pain relief (analgesia) and observation. Soft diet advised.

Soft diet is crucial. May require splinting to adjacent teeth for comfort, if materials are available.

Gently rinse any exposed root surface (do not scrub). Carefully reposition the tooth back into its proper place in the socket using firm, steady pressure. Splint to adjacent teeth if possible.

Gently rinse the tooth to remove debris. If possible and trained, administer local anaesthetic. Carefully reposition the tooth into its correct alignment. Splinting to adjacent teeth is required (ideally for 2 weeks, but stabilise as best as possible in the field).

Do not attempt to reposition the tooth. Provide pain relief. Requires specialist dental assessment for management.

Time-critical emergency - aim for reimplantation within 60 minutes. Prioritize: Check for serious injuries (head/spine/bone fractures); medical emergencies take precedence. Do not attempt if the patient is unconscious. Handle Tooth: Pick up by the CROWN (white part) ONLY. Avoid touching the root. Clean Tooth: Gently rinse root debris with normal saline, saliva, or clean water. DO NOT SCRUB. Transport (if needed): Best in patient's cheek pouch (if conscious/cooperative), or saliva. Avoid water. Prepare Socket: Gently remove blood clot. Reimplant: Carefully push the tooth firmly back into the socket. Stabilize: Have the patient bite gently on gauze/folded card for 5-10 mins. Splint: If possible, create a splint (e.g., paperclip, foil, nasal clip of face mask) and attach to adjacent teeth using dental cement or medical adhesive (Liquiband/Dermabond). Medication: Prescribe antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline with clindamycin / metronidazole for patients with penicillin allergies) for 7 days. Provide pain relief . Follow-up: Urgent dental review is essential.

First, check for any associated looseness or displacement (luxation injury).Minor (Enamel only): Smooth any sharp edges (e.g., with an emery board). Apply desensitizing toothpaste. Moderate (Dentine exposed, no pulp bleeding): Cover the exposed dentine with a temporary filling material (e.g., glass ionomer cement). Severe (Pulp exposed/bleeding visible): If the broken fragment is found, try reattaching it with adhesive. Otherwise, gently cover the exposed pulp (bleeding spot) with a sedative dressing (e.g., Ledermix/Odontopaste) and place a temporary filling over it. Pain relief is essential.

Airway Obstruction Risk

Trauma or swelling that may compromise the airway.

Suspected Conditions

Ludwig’s angina (a severe form of cellulitis that affects the floor of the mouth and can obstruct the airway).

Post-septal extension of maxillary abscess (infection spreading behind the septum, potentially affecting the airway).

Facial Fractures

Significant facial fractures that could impact breathing or require advanced surgical intervention.

Sepsis

Suspected or confirmed sepsis, especially if systemic symptoms are severe or deteriorating.

Uncontrolled Bleeding

Any situation where bleeding cannot be controlled effectively and poses a threat to the patient's stability.

This list includes all the essentials for managing dental emergencies in a remote setting, as well as some optional equipment for experienced practitioners.

Instruments

(Sterile disposable kits are available, usually including their own tray)

•2 dental mirrors (size 3)

•1 flat plastic instrument (stainless steel, used for placing dental filling material onto the tooth)

•College Tweezers

•Medium-sized spoon excavator (for scraping out soft caries/tooth decay)

•1 double-ended stainless steel cement mixing spatula

•1 glazed mixing paper pad (for mixing and moulding temporary filling materials)

•Disposable scalpel (number 15 blade)

•Cold sterilization tablets

Medicaments

•Temporary filling materials: Glass Ionomer powder + liquid, Intermediate

Restorative Material (IRM), or Cavit® , or Coltosol®

•Chlorhexidine 0.2% mouthwash (e.g., Corsodyl®) or 1% Corsodyl® Gel

•Duraphat (high fluoride varnish)

•Ledermix paste

•Antibiotics: Co-amoxiclav 500/125mg, Metronidazole 200/400mg, and Clindamycin 150 mg (penicillin allergy)

•Painkillers: Ibuprofen, Paracetamol, Codeine phosphate

•Dental local anaesthetic cartridges: 2% Lidocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline or 4% Articaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline

•Toothpaste for sensitive teeth

•Eugenol (oil of cloves) for topical analgesia

Other Items

•Cotton wool rolls

•Sterile gloves

•3/0 Black Silk or Vicryl suture, reverse cutting semilunar needle 19-21 length

•5ml syringes with blunt needles (for irrigation and flushing out debris in teeth gum pockets)

•Nasal clips from face masks (5) – can be used as dental splints

Practical Equipment

•2 head torches + batteries

•Gas aerosol for camera cleaning

Whether one is working in the best of conditions or the worst of conditions, a strong “improvise, adapt, and overcome” mindset is ultimately the key to success when things go awry.

Jason Jarvis NR-Paramedic MSc 18D

Not having the right bit of kit is no excuse to give up or to say that a thing is impossible. Instead, such a dilemma should be reframed as an opportunity to exercise the muscles of improvisation. Unfortunately, time spent in resource-rich environments often comes at the cost of atrophying of these vital muscles. In light of the improvisation that took place in the article1 below, it is clear that the nasogastric tube meets all of the criteria of an excellent piece of medical gear: it is lightweight, inexpensive, relatively small, and multi-purpose.

Thoracic injuries pose a challenge in conflict zones, where disrupted healthcare infrastructure and supply shortages limit access to conventional chest tube drainage (CTD) systems. This study evaluates the safety and efficacy of an improvised CTD system as a viable alternative in resource-limited settings in Sudan.

Methods

A prospective, single-center analytical cohort study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in Sudan from June to December 2023. A total of 120 adult patients (aged 18-70 years) requiring CTD for thoracic injuries were included. The improvised CTD system consisted of a radiopaque nasogastric (NG) tube and a repurposed 1.5-liter plastic water bottle as an underwater seal. Clinical outcomes, complications, and patient satisfaction were assessed. Serial imaging at baseline and 24-hour intervals evaluated lung re-expansion and drainage efficacy. Data were analyzed using SPSS, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Lung re-expansion was achieved in 90 % (N = 108) of patients within 72 h. Complications included atelectasis in 15 % (N = 18), subcutaneous emphysema in 20 % (N = 24), and empyema in 12 % (N = 14). Tube repositioning was required in 25 % (N = 30) of cases, and obstruction occurred in 10 % (N = 12). The mean hospital stay was 6.5 days, and mortality was 5 % (N = 6). Smoking status, age, and injury type significantly predicted complications. Patient satisfaction was high, with 85 % (N = 102) rating their experience as satisfactory.

The improvised CTD system is a safe, effective, and cost-efficient alternative for managing thoracic emergencies in conflict settings. Its adaptability addresses critical gaps in emergency care, offering a scalable model for humanitarian crises worldwide

1 Suliman A, Mohamedosman R, Suliman B, Musa H, Ali S, Ahmed M Improvised chest tube drainage: A practical approach to thoracic emergencies in humanitarian crises. Surg Pract Sci. 2025;21:100282. Published 2025 Apr 9. doi:10.1016/j.sipas.2025.100282

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Improvised chest tube drainage (CTD) system in a patient with right-sided hemothorax.

The yellow arrow indicates the CTD site with skin fixation.

The green arrow shows the improvised chest tube (NG) placed in the pleural cavity. The blue arrow demonstrates the drainage pathway to the water-seal bottle with visible blood drainage.

The black arrow highlights the airtight seal around the tube entry on the bottle cap secured with plaster.

The red arrow shows approximately 1500 ml of collected blood in the improvised water-seal drainage bottle.

1 Suliman A, Mohamedosman R, Suliman B, Musa H, Ali S, Ahmed M. Improvised chest tube drainage: A practical approach to thoracic emergencies in humanitarian crises. Surg Pract Sci. 2025;21:100282. Published 2025 Apr 9 doi:10 1016/j sipas 2025 100282

Malaria remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in many parts of the world, particularly in subSaharan Africa and parts of Asia In austere environments where trained medical personnel and advanced treatment modalities are limited, early diagnosis and immediate treatment of severe malaria are essential For remote healthcare providers, rapid assessment tools and alternative treatment routes are critical to saving lives

Aebhric O’Kelly M.Psy DTN FRSM FAWM

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are the primary assessment used in field settings to confirm Plasmodium infection A negative result on the RDT does not mean that the casualty does not have malaria It only means that the parasitemia levels in the blood are not high enough to be detected by the RDT A practical field criterion for diagnosing severe malaria is the patient's ability to swallow: patients who test positive for malaria but cannot swallow are assumed to have progressed to severe malaria This binary classification helps non-physician providers make informed decisions about treatment options If the patient can swallow, oral artemisininbased combination therapy (ACT), such as artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem), is indicated In contrast, if oral administration is not feasible, parenteral artesunate is typically required (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2015)

In settings where IV or IM routes are impractical, rectal artesunate has been demonstrated as an effective alternative. A large-scale study involving 17,826 participants in Ghana, Tanzania, and Bangladesh showed promising outcomes when rectal artesunate was administered by lay or minimally trained providers (Gomes et al., 2009). Although efficacy was higher among paediatric patients, adult administration proved feasible when pharmacokinetic parameters were considered. These findings affirm rectal artesunate as a viable treatment for adults with severe malaria in remote environments.

Current WHO guidelines and protocols from humanitarian organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières recommend rectal artesunate dosing at 10 mg/kg, typically delivered via 100 mg suppositories. Adult patients often require one or two suppositories based on weight (WHO, 2015). Importantly, this administration method is accessible to trained medics in austere settings, enabling life-saving interventions even when conventional administration routes are inaccessible.

In austere and resource-limited settings, the ability to initiate early and appropriate treatment for severe malaria is essential. Rectal artesunate provides an effective pre-referral option that can be safely administered by remote medical personnel when IV or IM access is delayed or unavailable. Integrating this intervention into remote medical protocols will enhance malaria care delivery and improve survival outcomes.

Sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) from which artemisinin is extracted.

References

Gomes, M et al. Pre-referral rectal artesunate to prevent death and disability in severe malaria: a placebo-controlled trial The Lancet, Volume 373, Issue 9663, 557 – 566

World Health Organization. (2023). The use of rectal artesunate as a pre-referral treatment for severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. https://www who int/publications/i/item/9789240075375

World Health Organization, Global Malaria Programme. (2007). Use of rectal artemisinin-based suppositories in the management of severe malaria: Report of a WHO informal consultation, 27–28 March 2006 (WHO/HTM/MAL/2006 1118)

Geneva: World Health Organization https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43694/WHO_HTM_MAL_2006.1118_eng.pdf?

Besides the Centers for Disease Control, my favorite free source for up-to-date information on global notifiable disease incidence and outbreaks comes courtesy of the Program for Monitoring Emerging Disease (ProMED).

ProMED is particularly useful in that it includes zoonotic disease in its daily updates. Given that the majority of recent pandemics had their origins in animals, it is worth paying attention to the illnesses that stalk our furry friends.

Jason Jarvis NR-Paramedic MSc 18D

Pandemics aside, many infectious maladies such as rabies, anthrax, leishmaniasis, hydatid disease, and West Nile virus thrive among animal hosts worldwide. A cursory review of ProMED’s recent “headlines,” as it were, indicated many rabies cases in both humans and in animals. A summary is reprinted below.

29 June Philippines

29 June India

27 June Morocco

26 June Vietnam

26 June Malaysia

26 June dog bite in Kazakhstan

25 June Togo

23 June East Timor

22 June Costa Rica bat bite

20 June India dog bite

20 June Namibia

20 June UK cases imported from Morocco & Kazakhstan

16 June Philippines dog

15 June Vietnam

9 June Norway – Svalbard

8 June Russia – Mordovia

5 June Spain, imported from Ethiopia

2 June Bolivia, US – NJ & Colorado

30 May Philippines

30 May Malaysia

28 May Philippines

27 May Thailand

26 May Malaysia

23 May Indonesia

22 May Vietnam

21 May Vietnam

12 May Vietnam

5 May US – Texas

5 May India

5 May Benin

4 May India

4 May Indonesia

3 May Vietnam

2 May India

30 April Bolivia, US – North Dakota, Massachusetts Florida, Georgia, Arizona

The following excerpt summarizes the CDC’s recommendations for rabies preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), dated 15 May, 2024.

The following excerpt summarizes the CDC’s recommendations for rabies postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), dated 20 June, 2024.

Rabies virion.

Rabies is a single-stranded negative sense RNA virus in the Rhabdoviridae family. It is enveloped, with helical capsid symmetry, and is vaccine-preventable.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/7AaU5yl8ptfXO1OXsH8rnO

This week, Aebhric O’Kelly talks with Alan O’Brien (OB), who is a paramedic from Ireland with a military background. They discuss OB’s journey from the Irish Army to becoming a paramedic. He shares insights into the evolution of paramedic training in Ireland, the importance of academic pathways for military medics, and the significance of the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) programme. The conversation also touches on the role of drones in modern combat medicine and the need for standardized medical training across NATO countries. In this conversation, OB discusses various aspects of military medical training, focusing on the NATO SOMT program, the future of the NSOCM programme, and the challenges faced in sustainment training for medics. He shares insights into the Irish Army Ranger Wing and the Nordic programme’s impact on medical training. OB also outlines his aspirations for developing a master’s programme in security and defence medicine and offers valuable advice for new medics entering the field.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/50BFScNn78txZaZgddyiKG

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3faMcfdYCAuF1rjoVKbOta

https://open.spotify.com/episode/1xd3fGMAFEbS9uWqQnF32C

Poster

Effects of whole blood donation on physiological responses

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Jones DM, Roberts N, Weller RS, McClintock RJ, Buchanan C, Dunn TL. Effects of Whole Blood Donation on Physiological Responses and Physical Performance at Altitude. J Spec Oper Med. 2025;25(1):29-34. doi:10.55460/ZXN7-EFUJ

Thirteen acclimatized military personnel (age: mean 28 [SD 6] years; height mean 175 [SD 7] cm; weight: mean 78.4 [SD 9.1] kg; residence elevation 2,100m) completed two 3.2-km rucksack carries (mean 24.2 [SD 2.1] kg from 2800 to 3,050m, one without BD (control) and one after BD. Total ruck march time, heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory rate (RR), minute ventilation (VE), rating of perceived exertion (RPE), thermal sensation (TS), and acute mountain sickness (AMS) symptoms were analyzed.

There were no differences between control and BD for ruck march time (F(1,11)=2.13, P> 1, η2G= 03), HR (P> 1), RR (P> 1), VE (P> 1), RPE (P> 1), and TS (P> 07) AMS symptoms were not impacted by either condition. SpO2 was lower in the control scenario than after BD (b=-4.23 [SE 2.4], P=.007).

A single-unit whole blood donation does not impact donor physical performance in acclimatized participants during combat-load carries at elevations up to 3,050m except with respect to SpO2.

Use of sugammadex in “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate”

Anesthesia and Analgesia

Abou Nafeh NG, Aouad MT, Khalili AF, Serhan FG, Sokhn AM, Kaddoum RN. Use of Sugammadex in "Cannot Intubate, Cannot Ventilate" Scenarios: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Anesth Analg. 2025;140(4):931-937. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000007199

EXCERPT

In 6/8 cases (75%), adequate spontaneous ventilation was restored after the administration of sugammadex In the remaining 2 cases, sugammadex administration resulted in an obstructed pattern of breathing, and surgical airway was the successful rescue technique There was wide variability in the sugammadex dose with a median (range) of 14 (5–16) mg.kg 1 and median timing (range) from rocuronium administration of 6 (2–10) minutes.

The recency and geographical origins of the bat viruses ancestral to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2

Cell

Pekar JE, Lytras S, Ghafari M, et al. The recency and geographical origins of the bat viruses ancestral to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2025;188(12):3167-3183.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2025.03.035

ABSTRACT

The emergence of SARS-CoV in 2002 and SARS-CoV-2 in 2019 led to increased sampling of sarbecoviruses circulating in horseshoe bats Employing phylogenetic inference while accounting for recombination of bat sarbecoviruses, we find that the closest-inferred bat virus ancestors of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 existed less than a decade prior to their emergence in humans. Phylogeographic analyses show bat sarbecoviruses traveled at rates approximating their horseshoe bat hosts and circulated in Asia for millennia We find that the direct ancestors of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are unlikely to have reached their respective sites of emergence via dispersal in the bat reservoir alone, supporting interactions with intermediate spillover These results can guide demonstrate that viral genomic related to SARS-CoV and SARShorseshoe bats, confirming their reservoir species for SARS viruses

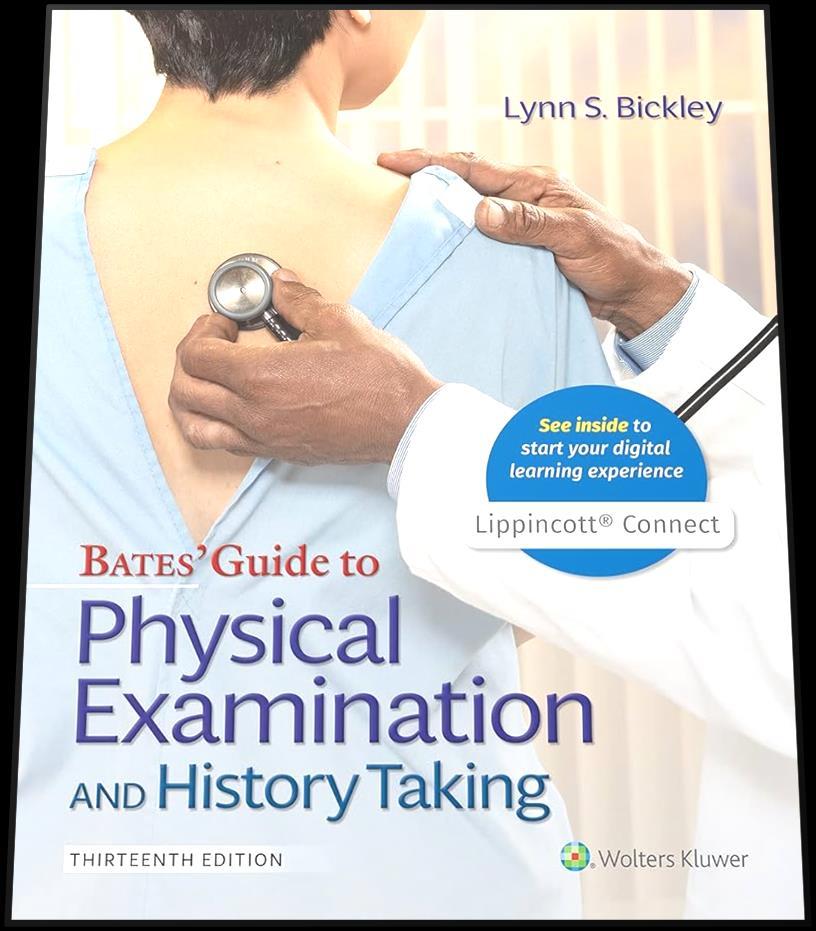

by Dr. Tom Mallinson

Review by John Clark

Dr Tom Mallinson's "MCQs for Specialist & Enhanced Care Paramedics" is a comprehensive resource for paramedics looking to advance into enhanced and specialist roles The book fills a crucial gap in educational materials for paramedics aiming to progress beyond their initial qualifications

The book is thoughtfully organized into four main sections, mirroring current paramedic career progression frameworks and the "Four Pillars" approach often referenced in advanced practice:

• Primary and Urgent Care (100 questions)

• Critical Care (101 questions)

• Austere Medicine (100 questions)

• Leadership and Management (100 questions)

Each section includes recommended completion times (typically 90 minutes for 100 questions), indicating the author's understanding of real-world examination conditions. The inclusion of difficulty ratings (Easy, Medium, Hard) within each section helps cater to various learning needs and supports progressive skill development.

The book's primary strength lies in its extensive coverage of specialized paramedic domains. The Critical Care section, for example, effectively transitions from basic emergency care to advanced critical care concepts. This makes it valuable for both newly qualified paramedics and those pursuing specialized certifications like DIMC, CCP-C, or FP-C.

The Austere Medicine section stands out for its focus on an often-overlooked specialty. By including expedition, remote, and wilderness medicine, Mallinson addresses the broad scope required for paramedics working in challenging environments. The references to established resources, such as Wilderness Medical Society guidelines and the Oxford Handbook, underscore the book's academic rigor.

Mallinson's decision to provide answers at the end of the book, along with difficulty classifications, promotes effective self-directed learning. The suggested timing for each section also helps readers practice managing their time under exam conditions.

A unique and valuable feature is the dedicated interview preparation section. This goes beyond typical MCQ content, offering practical advice on professional presentation, staying informed about current affairs, and using the ‘Tell Your Story’ approach for competency-based questions. This focus on real-world recruitment processes acknowledges that career advancement requires both clinical knowledge and strong interview performance.

The book directly addresses the emerging Enhanced Care Paramedic tier recognized by NHS England, making it highly relevant to the evolving UK healthcare landscape. It also benefits candidates preparing for various professional certifications, from the College of Paramedics' DipPUC to international certifications from IBSC, enhancing its overall value.

While the book's organizational structure is strong, the ultimate effectiveness of any MCQ resource depends on the quality and accuracy of the questions themselves, which cannot be fully assessed without reviewing them. The effectiveness of the difficulty grading system and the clinical relevance of scenarios would also require a detailed examination of the actual questions.

The introductory discussion on terminology, while necessary, highlights the ongoing complexity and potential confusion surrounding paramedic role definitions – an issue the book acknowledges but cannot fully resolve.

“MCQs for Specialist & Enhanced Care Paramedics” appears to be a well-structured and comprehensive resource that meets a clear need in paramedic education. Dr. Mallinson has created a tool that covers the full range of specialist paramedic practice while remaining practical for examination preparation.

Its alignment with current professional frameworks and broad coverage of specialized domains makes it a valuable resource for paramedics looking to advance their careers. Although the final measure of its effectiveness depends on the quality of individual questions, its thoughtful organization and comprehensive scope make it a strong contender for any paramedic pursuing specialist or enhanced care roles.

“The next seminal development in vaccines [after Edward Jenner’s work on the prevention of smallpox using variolation] came through the research of Louis Pasteur who had developed the germ theory of disease…The attenuation of virulent organisms was reproduced by Pasteur for anthrax and rabies using abnormal culture and passage conditions. Recognizing the relevance of Jenner’s research for his own experiments, Pasteur called his treatment vaccination, a term that has stood the test of time.”

Roitt’s Essential Immunology, 13 edition

Which atrioventricular block is shown?

A. 1st degree

B. 3rd degree

C. 2nd degree type I

D. 2nd degree type II

The expedition dentist has asked you to mix epinephrine into bottles of lidocaine to support an upcoming free dental clinic for the indigenous tribespeople. She hands you several 50 mL bottles of 2% lidocaine and a multidose bottle of epinephrine 1:1000. She specifies that the lidocaine bottles must contain an epinephrine concentration of 1:80,000 to achieve an adequate level of vasoconstriction. How many mL of the epinephrine should you add to each lidocaine bottle?

While setting up a remote clinic in Vietnam’s Yen Bai province, you discover tiny (1 mm) swimming organisms within the local river. If ingested, what disease might your patients and colleagues be at risk of acquiring?

A. Murine typhus

B. Dracunculiasis

C. Schistosomiasis

D. Cercarial dermatitis

Sapphire Multi-Therapy Infusion System available at https://eitanmedical.com/infusion-pumps/sapphire-multi-therapy/

The Sapphire Multi-Therapy infusion system is a complete solution for varied clinical uses in hospital, ambulatory and EMS settings. Offering ease of use and reliability, Sapphire combines high end volumetric infusion pump functionality with compact size and low weight.

Sapphire is based on a unique combination of patented Flow Control Technology, innovative hardware design, intuitive touch-screen and software control, and low total cost of ownership. With its robust design, easy maintenance, and built-in adaptability to evolving requirements, Sapphire delivers medication infusion confidence now, and far into the future. This same technology powers a wide range of dedicated infusion pumps, creating a single-platform that answers all medical infusion needs.

The Sapphire advanced multi-therapy infusion pump is designed for PCA, TPN, Continuous, Piggyback, Intermittent and Epidural treatments.

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-forprofit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries

The College was founded in 2016 and is governed by a Board of Regents supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority License No 2018-022

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources.

CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

MFSLR 18 Sept

8-13 Sept

29 Sept-3 Oct

SOMSA Conference 27 April - 1 May 2026

Tactical Medicine Review (Clark, HolmstrØm, Birks, Moront)

Improvised Medicine (O’Kelly, Jarvis, Moront, Shertz, Loos)

Austere Clinical Laboratory Diagnosis (O’Kelly)

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice Doctor of Health Studies

Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Award in Tropical & Expedition Medicine

Online

Critical Care Transport

Basics of Resource Limited Critical Care

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro Ghana National Ambulance Service

AREMT 23-28 March 2026 ITALY

ACC

6-10 Oct BSc RPP/Y1 module 27 Oct-15 Nov RPP104 3-22 Nov Medicine in the 30 Jan-1 Feb 2026 Mediterranean

2-7 Feb 2026 TTEMS 9-15 Feb 2026 APUS 14-15 Feb 2026

ICARE 16-20 Feb 2026

Clinical Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

Acute Critical Care

AEC Austere Emergency Care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

AREMT Award in Remote Emergency Medical Technician

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

Mission to Heal goes where medical need is greatest. We visit remote regions to teach basic surgical skills to local healthcare practitioners so they can care for their community year-round. Due to our educational approach, we need a variety of expertise on these missions. We welcome the following specialists to volunteer with us:

Nurse Anesthetists

Tropical Medicine Specialists

Obstetricians & Gynecologists

Optometrists & Ophthalmologists

Dentists & Oral Surgeons

General Surgeons

OR Nurses

Triage Nurses

Medical & Dental Students

Residents

As you can see, it’s a wide-ranging list – but it’s not all inclusive. If you have a specialty that’s not listed here, but would love to volunteer with us, there is still a place for you! Why volunteer?

- Get a transformational learning experience where you learn just as much as you teach. - Experience a culture outside of your own.

- Experience how healthcare is practiced in other countries.

- Use your expertise to benefit the less fortunate.

As one of our volunteers said to us, “We want to volunteer with you because you actually do.”

Useful links:

Volunteer with Mission to Heal - https://missiontoheal.org/apply/ Volunteer FAQ’s - https://missiontoheal.org/faqs/ Our approach to missions - https://missiontoheal.org/approach/ Volunteer reflections - https://missiontoheal.org/blog/ Questions about M2H missions – samuel.jangala@missiontoheal.org

2025 Missions: Kenya IV August 8-24

https://www.masteryourmedics.com/pages/fastcanada2025

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

Canine medicine

…and much more!