The Journal of the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation

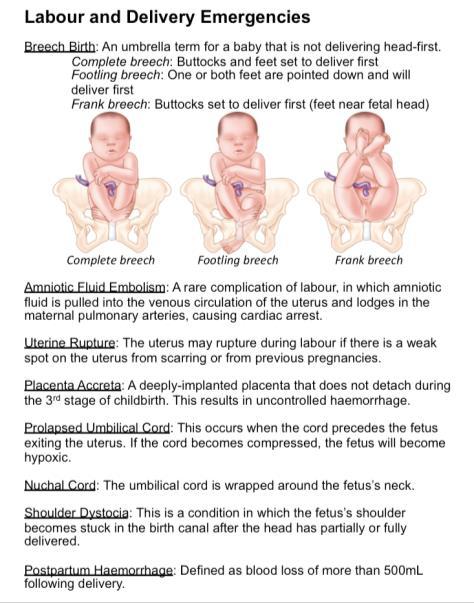

Spring 2024, Volume 7, Issue 22

Spring 2024, Volume 7, Issue 22

I am very excited to announce that Mr. Alfredo Leal has been awarded the first CoROM full MScACC degree! He is the first to finish the program after he presented and defended his dissertation on 19 March 2024

Alfredo Leal is a distinguished healthcare professional with a wealth of experience and expertise in emergency medical services (EMS) and critical care for 28 years His extensive qualifications and registrations span across multiple countries, reflecting his dedication to providing top-tier medical care worldwide He is currently working with Alpha Star Aviation Services in Saudi Arabia as a Flight Paramedic

John Clark JD MBA NRP

John Clark JD MBA NRP

With a Bachelor of Science (Hons) in Paramedicine and now a Master of Science in Austere Critical Care from CoROM, Alfredo's academic background underscores his commitment to excellence in healthcare provision, particularly in challenging environments. His postgraduate studies include specialized training in Medicine of Conflict and Catastrophe, as well as Professional Practice. Alfredo, a Fellow in the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM), is enrolled in CoROM’s Doctorate in Health Studies starting in September 2024.

Alfredo's career journey has taken him across various regions, where he has held pivotal roles in EMS and critical care. As a registered Paramedic with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) in the United Kingdom, he has demonstrated his proficiency in delivering high-quality care in accordance with stringent regulatory standards.

Furthermore, he is registered with the Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC) in the Republic of Ireland as an Advanced Paramedic; with the International Board of Specialty Certification (IBSC) in the United States as an FPC and CCP-C; with the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) as a Specialist in EMS; and as a Paramedic with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) in Australia; with the Kaunihera Manapou Paramedic Council in New Zealand; and with the Ukrainian Medical Council.

His expertise extends to offshore medicine, having served as an HSE Offshore Medic mainly in the North Sea. Additionally, his experience working in Afghanistan, Occupied Palestinian Territories, Ukraine, Qatar, and in the States of Jersey, Channel Islands; showcases his adaptability in diverse healthcare settings.

Alfredo's expertise encompasses various facets of emergency medical care, including his past roles as an Emergency Medical Technician in Portugal. His multidimensional skill set and unwavering dedication to advancing healthcare make him a respected figure in the global medical community.

Beyond his clinical achievements, Alfredo holds a master’s degree in history, Defence, and International Relations, reflecting his intellectual curiosity and interdisciplinary approach to healthcare His commitment to continuous learning and innovation underscores his status as a leader in the field of emergency medicine and critical care

Alfredo’s accomplishment is only one of the milestones of CoROM Enlarging our beachhead in the austere critical care community is our objective To do so, we must have a solid plan to execute The Board of Regents will help us develop and update that plan and will be pivotal to continued growth and success For 2024, we have empaneled a group of very talented subject matter experts whom will hold this responsibility in the highest regard Let's delve into the composition and role of this influential body that will drive the advancement of our academic endeavors

The primary mission of the Board of Regents is to provide oversight and strategic counsel to the Dean on matters pertaining to the management and enhancement of continuing education, continued competency, as well as our bachelor, master, and doctoral degree programs Operating within the regulatory framework set forth by the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority (MFHEA), the Board of Regents will ensure alignment with academic standards while fostering innovation and excellence

Comprising a diverse group of individuals, the Board of Regents embodies expertise and dedication to CoROM's mission, vision, and objectives Here is our roster of esteemed directors:

•Board Members at Large: Four individuals appointed for their expertise in relevant fields, including education and academia, serve a four-year term Among them are: 1.Wyndham Pierce, an accomplished Fire Fighter/Paramedic from Dublin (Ireland) Fire Brigade

2.Price Parker, with a wealth of experience from his time as a combat medic with the US Army 10th Grp based in Stuttgart

3.Giedrius Meskauskas, bringing his insights as the Lithuanian Emergency Medical Team Manager

4.Emmanuel Acheampong, a distinguished Nurse Lead representing the African Federation for Emergency Medicine from Ghana

•Public Member: An appointment from the community, unaffiliated with the college, serving a three-year term This position remains open, awaiting a dedicated individual to contribute their perspectives

•Administrative Board Member: Appointed from the CoROM Foundation Board of Administrators, this member serves as a permanent fixture, facilitating communication between the College and Foundation Currently, Graham Pierce, CEO of the International Board of Specialty Certification, holds this vital role

•Faculty Representatives: Elected by the CoROM faculty, Tim Cranton and Dr Csaba Dioszeghy will serve a two-year term, embodying the academic excellence and dedication of our teaching faculty

•Student Representative: Rhodi Jordan, MGH Student and President of the CoROM Student Union, represents the student community, ensuring their voices are heard in the governance process

•The Executive Dean: Serving as an ex-officio member, I will provide institutional leadership and strategic guidance, aligning Board decisions with CoROM's overarching objectives.

The Board of Regents shoulders significant responsibilities, including:

•Providing strategic direction and oversight to uphold academic quality and integrity.

•Approving academic programs, policies, and budgets in alignment with regulatory standards.

•Monitoring institutional performance and fostering continuous improvement initiatives.

•Safeguarding the interests of stakeholders, including students, faculty, staff, and the broader community.

In essence, the Board of Regents serves as the cornerstone of CoROM's governance structure, ensuring our institution remains at the forefront of austere, remote and offshore medicine education.

A dedicated page on the CoROM.edu.mt site is being created with links to speak to any of the Board. As we navigate the ever-evolving landscape of higher education, I extend my appreciation to the dedicated members of the Board of Regents for their unwavering commitment to excellence and the advancement at CoROM. Warm regards,

This issue might very well be nicknamed “the African edition ”

Dr. Geelhoed returns with more clinical pearls of wisdom, with a very relevant discussion on expectations (and pitfalls) of humanitarian aid in resource-poor settings such as during his recent foray into western Kenya.

‘Boots on the Ground’ provides insights into one of CoROM’s most unique clinical rotation locations: Kibosho Hospital, Tanzania (incidentally, this is where my profile picture was taken).

‘Tropical Medicine Update’ takes a look at the ongoing cholera outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo and deep-dives into cholera case presentations as well as treatment guidelines.

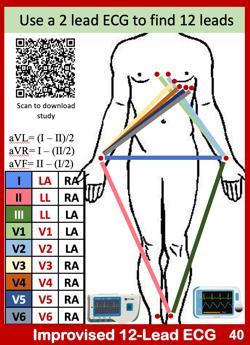

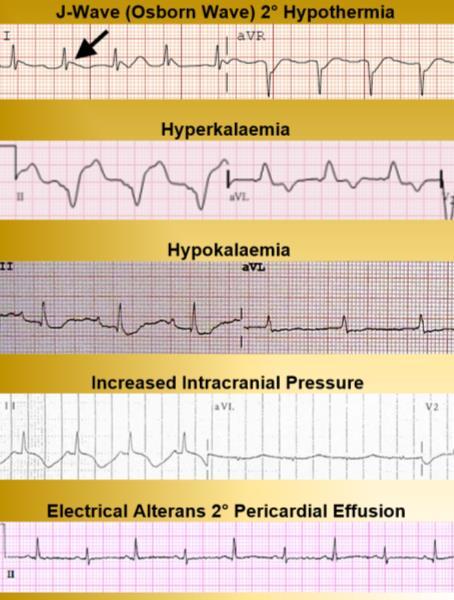

As always, ‘Improvised Medicine’ teaches motivated yet resource-constrained healthcare providers how to do more with less – in this case, obtaining a 12-lead ECG without actually being in possession of 12-lead-capable technology

Rounding out the issue is a snapshot of the 2024 TCCC updates, as well as a wide range of resources to help healthcare providers stay abreast of the latest and greatest in austere medicine

Programme Lead. He is a paramedic and of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan. As of 2024 he is beginning his third transect of Africa teaching predeployment medicine courses for UN peacekeeper clinicians. Jason is a freelance medical educator who teaches advanced trauma courses, minor surgical procedures, ACLS for Experienced Providers, and PALS He has presented several times at the Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly and is an article reviewer for both International Health and Wilderness and Environmental Medicine Jason holds a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Beginning in 1929 as a dispensary and later upgrading to hospital status in 1965, Kibosho Hospital is now one of three Council Designated Hospitals owned and operated by the Catholic Diocese of Moshi. Located in Moshi Rural District of Tanzania, the hospital is situated 1400 meters above sea level in Singa Village at the foot of iconic Mount Kilimanjaro.

The hospital is led by the very competent and motivated Medical Superintendent Dr. John Materu who takes a very personal, hands-on approach to improving patient care and making improvements in service. He is supported by an equally dedicated administrative staff. In total, there are 189 staff at the hospital.

As one would expect, Kibosho Hospital is a busy place with an average of approximately 50,000 outpatients and 5,000 inpatients seeking treatment there. The facility is approved for 220-bed capacity but currently operates at 200. Despite its rural location, the hospital offers a broad range of services with full-time specialists available for dental, orthopedics, obstetrics and gynecology, and epidemiology / public health. These services will soon expand as a full-time pediatrician and general surgeon is expected to be available at the hospital later this year.

As a CoROM student, one has numerous options for clinical placement which helps in preparing you for your own future planned practice goals. I chose to apply at Kibosho Hospital for my second year clinical since the focus of my future practice plans is voluntary rural missionary/charity hospital and clinical NGO work in the Asian sub-continent. Kibosho’s locale in rural Africa better prepares me to operate with more autonomy in an austere, resource-limited environment.

Upon arriving for a clinical placement, a CoROM student can expect a warm reception by Dr. Materu and the administrative staff of the hospital. On the day of my arrival, I received a hospital tour and was then settled into my accommodations onsite for the remainder of the day to eat and rest up from my journey. I did take advantage of a quick walk around the area outside of the hospital, proceeding by foot to the Kibosho Seminary where I enjoyed a fantastic view of Mt. Kilimanjaro’s peak, walked a bit through the forest, and generally got my bearings.

Student accommodations are an onsite three-bedroom flat which are basic, clean, safe, and conveniently located less than a five-minute walk from the EMD. As I was the sole student in attendance, I had the entire flat to myself. Each day, a sister prepares three meals for you and otherwise caters to your dietary requirements.

My cell phone provider partners with Vodaphone in Tanzania, and the reception is more than adequate. I used it as a Wi-Fi hotspot for my laptop without issue, having even attended the live streaming of the WMS Winter Conference during my clinical placement. However, due to its remote rural location, Kibosho has limited local shopping options. I found it useful to shop for basics in Moshi prior to arriving at the hospital. Since then, with the help of the CoROM driver Johnny, along with fellow CoROM student Mick Rayner, I have periodically gone into Moshi (about a 30minute drive) for a quick re-supply and meal.

Students are free to set their own clinical schedules at Kibosho. In my case, due to my planned time at the hospital and duration of being in country, I have elected to work a combination of 10- and 12-hour shifts each week so that I could obtain at least 75 hours per week of clinical time in the EMD. This is a solid pace you are on your feet quite a bit.

It is best to maintain a healthy routine with balanced clinical hours as one can quickly grow tired. Personally, I would prefer to work less hours each day in order to have more time to study and exercise. Unfortunately, I am under time constraints due to my employment leave time allotment and need to obtain 375 hours, so sacrificing on “wants” is simply necessary.

Students can expect a fast start to their clinical placement. On the day after my arrival, I arrived in the EMD at 06:45 for the 07:00 shift. It was very busy, and no time was wasted putting me to work. First there were the usual basics patient vital signs, charting, administering medication, IV cannulation, and urinary catheterization all under the watchful eye of a friendly RN who wanted to assess my skill set competence. Any areas that are beyond your competence/confidence level or as to which you require more background knowledge, simply ask; both the physicians and nurses are happy to assist.

While each day was different, my typical day began at approximately 06:45 with patient rounds / case reviews. After an 07:30 faith meeting (Monday – Friday), at 07:45 is the morning doctors’ meeting which CoROM students are invited to attend. I found these to be quite valuable with generous knowledge-sharing as well as often interesting case reviews. Afterwards, while in the EMD, you can expect to be working in all areas throughout the day with much variability depending upon patient type and load. Essentially, one can expect to do everything taught in years one and two of the CoROM BSc program. A paramedic can put to practice repeatedly all skill sets, and use knowledge learned in the CoROM program across all patient types from neonates to the very elderly. Once you have established trust and mutual respect with a demonstrated willingness to work, you will be afforded quite a bit of autonomy in delivering patient care and feel as though you are just a regular member of the team.

Most cases that I have experienced so far are medical and often complicated; patients here tend to only come to hospital once they have progressed to the point of being seriously ill. Often their condition is a result of not being medication compliant or lack of access to healthcare due to socio-economic challenges. Pneumonia, hypertension, diabetic crisis, septicemia, congestive heart failure, anemia, renal failure, CVA, and ETOH poisoning are the standard fare. There is trauma, of course, but to a much lesser extent. I have assisted and cared for severe burns, physical altercation injuries, fractures, septic wounds, and the like. There is poly-trauma at times, and some very severe, but I have yet to experience this as of the time of writing this article (halfway point of my placement).

An invaluable aspect of this clinical assignment for me personally is the amount of direct contact and nursing time I have with many patients in the EMD’s attached high-acuity wards and ICU. This enables me to observe, treat, and follow patients from arrival through their treatment and healing process. It can take as much as a week and sometimes longer for a patient to be suitable for transfer to a general ward, transfer to a more specialized facility, or discharge.

The extended patient contact helps me better understand the disease progression process from theory to actual, real-time, direct patient observation and treatment. This aspect is unique and is likely something most paramedics do not get to experience in more traditional EMS systems. For the Remote Practice Paramedic, I feel this extended contact is crucial.

Although in general I have been kept more than occupied inside the EMD, there are lulls in activities where you may take advantage of visiting, observing, assisting, and simply asking questions in other areas of the hospital. While it is incumbent upon you to be proactive and seek out these opportunities, they do exist if you take the initiative. The staff are generally very open and welcoming to your inquisitiveness. Like all endeavors, the effort you put into the clinical placement at Kibosho Hospital equates to the benefit you receive from it.

I have received so much friendly support from the hospital staff in furthering my skills, knowledge, and experience that frankly, I have experienced some guilt, feeling that I am receiving far more than my contributions.

With fellow CoROM student Simon Ruparelia’s initiative to improve emergency resuscitation at the hospital as an inspiration, I took the opportunity to dovetail off his efforts and build upon the work he began. Simon reclaimed an old disused crash cart and has stocked it significantly with his personal equipment/resources organizing it and building a solid foundation to be further built upon later. Drs. Materu and Dr. Daniel Mganga EMD Doctor in Charge, are appreciative of his efforts and want to develop it further as it is central to EMD services for which they are ill equipped.

Using mannequins borrowed from the attached Kibosho College of Nursing, I undertook an initiative to train and properly certify EMD staff and physicians in BLS at the Healthcare Provider level. This was at the request of Dr. Materu which helped me feel that I was “doing my part.” A huge challenge to this project, however, was that there is no AED or defibrillator at the hospital. Discussing this with my fellow CoROM Student Mick Rayner (who was close by at KCMC), he suggested an AED app which I promptly downloaded on my iPad. After fashioning makeshift AED pads made from scrap materials, we were in business! Dr. Mganga, keen on developing a team approach to resuscitation, helped in running code drills as part of the course using the crash cart. Essentially, we exceeded the BLS requirements and built it into a BLS++ course with the inclusion of ECG, IVs, OPA/NPAs, and frontline medication.

Having participated in several resuscitation attempts already, I have seen firsthand the real need to better secure an airway than with OPA/NPAs. With the blessing of Dr. Materu and support of Dr. Mganga, I have been able to source and acquire from Nairobi four complete, full-sized sets of iGel supraglottic airways for trial in the crash cart. Additionally, with the support of my family, we have been able to acquire a new AED for the EMD.

I do not wish to give the impression that it is expected for CoROM students make purchases or donations when on clinical placement. However, I do feel that as paramedics it is incumbent upon us to lead and provide solutions wherever we come across gaps in patient care that we can help solve. The knowledge, skill, practice, and experience which we as CoROM students are privileged to obtain during a clinical placement such as at Kibosho Hospital more than offsets the value of reasonable giving in return.

Hopefully all of this equipment will arrive before I depart, but if not, the training and commissioning of it will be an excellent project for the next CoROM student coming to Kibosho Hospital. The crash cart project, supraglottic airways, and AED acquisition will go further to assist the hospital in meeting a recent Ministry of Health Inspection and subsequent recommendations to upgrade this area of concern.

I have about two more weeks left to complete my clinical placement. So far it has been an extremely positive experience, and I look forward to that continuing.

Kibosho Hospital may not be for everyone. But if you are seeking experience in a resource-limited area with a good patient load, and if you can think outside of the box on the fly, make do with what you have, and appreciate a degree of practice autonomy, this is a great location. For me personally, I look forward to returning here for my next clinical placement later this year.

NOTE: If anyone is interested in selecting Kibosho Hospital as a clinical placement site, they may reach out to me on my CoROM e-mail, and I am more than willing to arrange a Zoom meeting to discuss the same.

Lance

4 April 2024

From left to right: Dr. Daniel Mganga, Doctor in Charge of the Emergency Medical Department; Dr. John Materu, Medical Superintendent of Kibosho Hospital.

From left to right: Dr. Daniel Mganga, Doctor in Charge of the Emergency Medical Department; Dr. John Materu, Medical Superintendent of Kibosho Hospital.

We have a clinic for screening patients this morning; some have dental complaints, others are carrying children they want to be seen, and a larger number are being lined up for screening by the antenatal clinic we will initiate with Nicole Williams and her sonography unit. The Turkanaspeaking CLO (Community Liaison Officer from LTWP [Lake Turkana Wind Power]) said something curious to me. He said the people were disappointed. Why? “You come with these big trucks, and you are not giving us lots of medicines!” “What is your problem you would like to have resolved? “No problem; we just want lots of medicines for all diseases!”

Glenn Geelhoed MD, AB, BS, MA, DTMH, MPH, MPhil, EdD, ScD, FACS, MAMSE

Glenn Geelhoed MD, AB, BS, MA, DTMH, MPH, MPhil, EdD, ScD, FACS, MAMSE

Someone, or some agency, has clearly pre-conditioned their expectations, that an NGO comes loaded with “Free Stuff ” They had hoped to come with big bags and go back with loads of free stuff that would keep them from ever being sick And here we arrive with big white trucks and tell many of them that they do not need medicines, and even more of them that they do not need operations So, what good are we, anyway?

I said through Rose that a higher objective would be not to need medicines than to start by taking everything and wind up sicker than if they had just stuck to clean water, adequate food and regular exercise. What they have come for is a substitute for all of this that requires any input of personal effort, and you doctors are supposed to cure and prevent all diseases; it is “Not my Job!” How thoroughly modern and First-World of them!

I have to disabuse some members of the team to re-define roles. For example, “A surgeon is a doctor who can operate, and does so on lots of patients in ‘surgery camps’. ” No. “A Surgeon is a Physician who can operate and knows when and for whom to do so and, more importantly, who would NOT benefit from a procedure applied mindlessly upon anyone who should happen by such a mass ‘surgery camp.’” My chief role here is to be teaching judgment, whereas both many of the patients and some of the providers are eager to get some indication of their selfworth by “Doing Something---Anything especially something no one else is doing.” A ‘Surgical Camp’ would be a great success, since there would be reports of many operations, whether or not there were any indication for many of them, and the measurable metric to write home about is how many cases were done, not the humanitarian benefit or outcome of any of them that might best be random. Like a “Truckload of medicines” let loose on this population, the chances for harm would outweigh the accidental benefit to a very few. After arranging through the CLO the transportation of several mothers and children for putative diagnoses of TGDC [thyroglossal duct cyst] and inguinal hernia to the next mission in April in Ngurunit when we will have both pediatric surgeon and anesthetist, I had re-checked the patients being referred, intercepting misdiagnoses, neither of whom required operations.

I was assisting Mohammed in a dental extraction in a young man who passed out, and we had to elevate his legs and then put him on an examining table. Some might say that this should facilitate the procedure that was undertaken, since now the extractions could be done under general anesthesia, quickly while the patient was “out!” This, again, would be an error from focusing first on the procedure intended and not the patient who is to be the alleged beneficiary. It happened again later with a woman patient, who also had an extended nap at the clinic after the injection of the local anesthetic, through no property of either the drug or the administrator of it

A good deal of the syncope has to do with the dehydration status of everyone here, patients and providers alike. I have felt somewhat light-headed myself and have kept track of the amount of water I am drinking and the number of times I am peeing the first a very high number and the latter nearly zero. I decided to change that immediately, so I have now been adding the abundant stocks of Gatorade powder I had brought in over several trips to maintain the circulating volume. One of the problems is that the only place where I feel drippy hot and sweaty is in the MSU [mobile surgical unit]. In most of the slow movement between the clinic and the MSUs parked out in the blazing noonday sun, I feel like a hot air balloon is being deflated in a swoosh around me But I do not feel sweaty since the sweat sublimates directly and this makes the loss “insensible ”

On return to the parked MSUs I note a group of six dogs lying like roadkill under the rear of the vehicles, and a gaggle of eight people also taking advantage of the shade from the overhead sun, also splayed out under the dried-mud-caked chassis. If anyone wishes to write up a tourist brochure on the potential for the Lake Turkana resorts, I would recommend some copywriter from far away who has never been here emote glowingly about the balmy warmth of the tropical sun in year-round baking in the glow of the sunshine. No one here gets sentimental about the balmy warmth of the Lake Turkana desert sun. The sun sucks life. Every animal and human being slinks toward even a minimal sliver of shade, and almost no one is fussy about what the solar obstruction might be as long as it keeps the burden of the oppressive radiation of heat and light off the biologic package of some flimsy skin containing a balance of mixed fluids that would be brought to boil and the container burst without the shelter in the shade

Dr. Glenn Geelhoed received his BS and AB cum laude from Calvin College and MD cum laude from the University of Michigan. He completed his surgical internship and residency through Harvard University at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital Medical Center. To assist in developing further volunteer surgical services in underserved areas of the developing world, Glenn completed masters degrees in international affairs, epidemiology, health promotion and disease prevention, anthropology, and a philosophy degree in human sciences.

He still works as a professor of surgery at George Washington University Medical Center in Washington D.C. and is a member of numerous medical, surgical, and international academic societies. Glenn is an avid game hunter and runner. He has completed more than 135 marathons across the globe. He is also a widely published author accredited with several books and more than 500 published journal articles and chapters in books. He has two sons and five grandchildren.

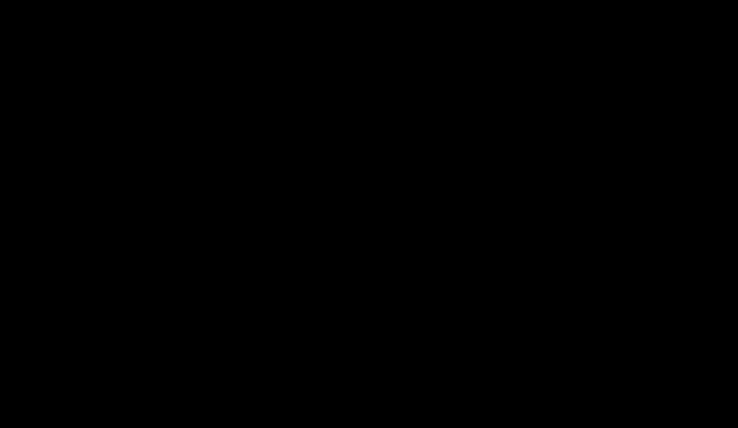

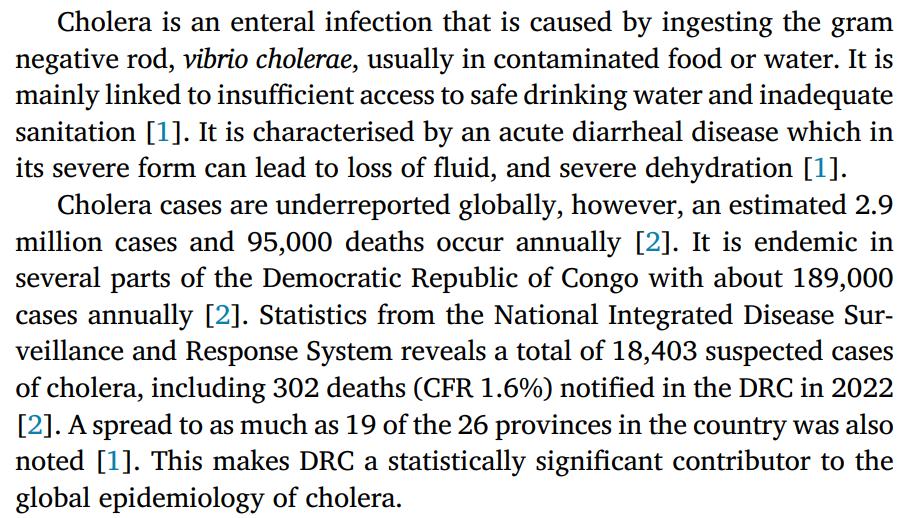

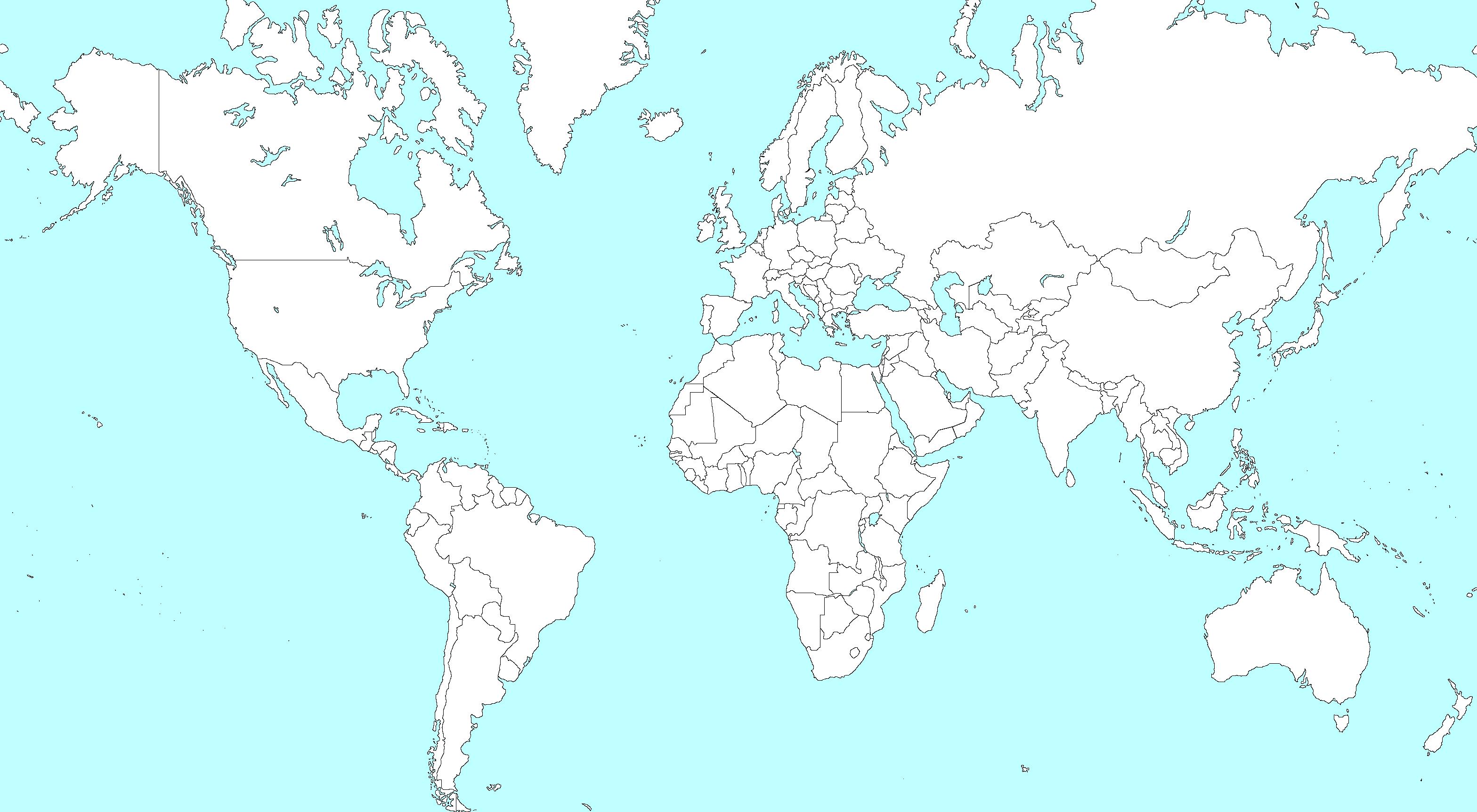

A long-running outbreak of cholera continues to beleaguer the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). As the secondlargest African nation reels in the throes of armed conflict and flooding, the age-old cholera bacterium thrives not only in DRC, but in many other locations throughout the developing world.

Jason

Jarvis MSc 18D NR-Paramedic

Cholera hotspots within DRC.

Flooding in Kinshasa, DRC, on 12 January 2024. Photo credit: UNICEF

Bunia

Goma

Bukavu

Baraka

Kalemie

Kasenga

Bukama

Jarvis MSc 18D NR-Paramedic

Cholera hotspots within DRC.

Flooding in Kinshasa, DRC, on 12 January 2024. Photo credit: UNICEF

Bunia

Goma

Bukavu

Baraka

Kalemie

Kasenga

Bukama

https://iris.who.int/han dle/10665/372986

Mai Mai militia members from the APCLS armed group after recapturing Photo credit: The Guardian

Mai Mai militia members from the APCLS armed group after recapturing Photo credit: The Guardian

Causative organism: Vibrio cholerae, a motile flagellated curved gram-negative bacteria. While there are >200 serogroups, types O1 and O139 are responsible for epidemics.1

Reservoir: Humans; zooplankton and copepods residing in brackish water such as river-ocean estuaries.

Mode of transmission: Fecal-oral route.

Incubation period: Typically 2-3 days (range is a few hours to 5 days)

Pathophysiology: V. cholerae shedding of enterotoxin that affects the small bowel.

Infection severity: Most infections present asymptomatically or with mild signs and symptoms – infected persons are contagious regardless of disease severity.

Signs and symptoms: In severe cases: sudden onset of copious fishy-smelling “rice water” diarrhea, borborygmi, cramping, acidosis, hypoglycemia, renal failure. These patients are typically afebrile.

Differential diagnosis: Enterotoxigenic E coli, Campylobacter species, Salmonella species 2

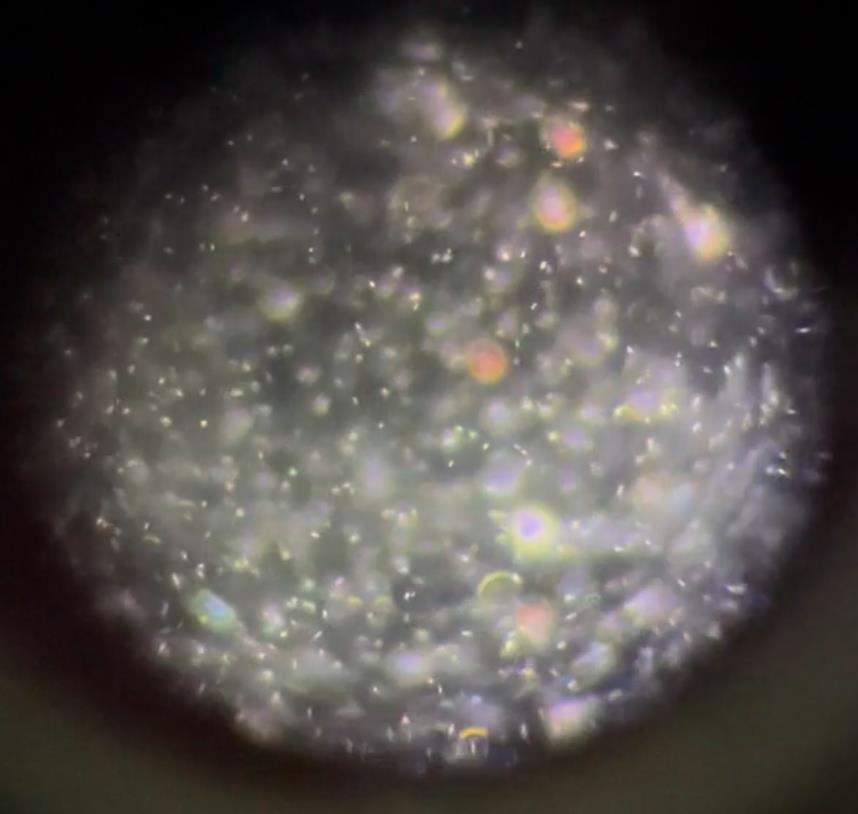

Field diagnosis methods: Presumptive based on clinical signs; dipstick RDT; dark-field microscopy.

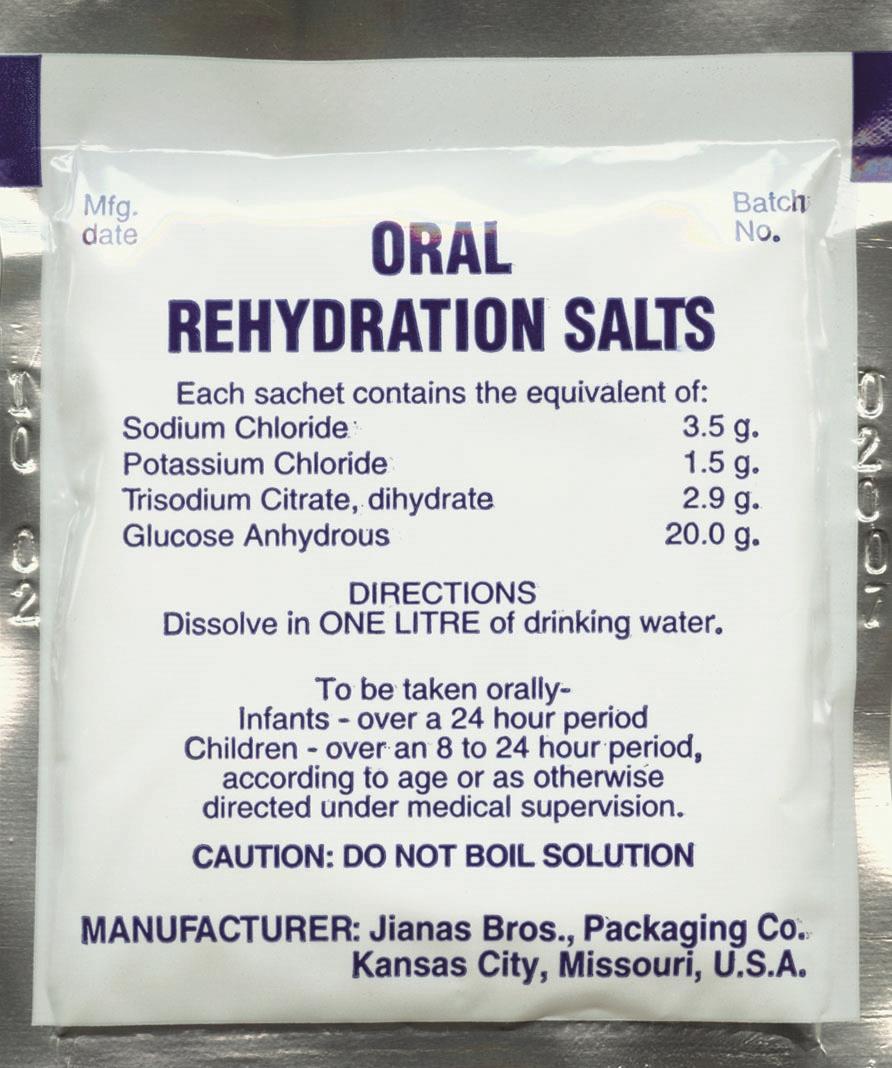

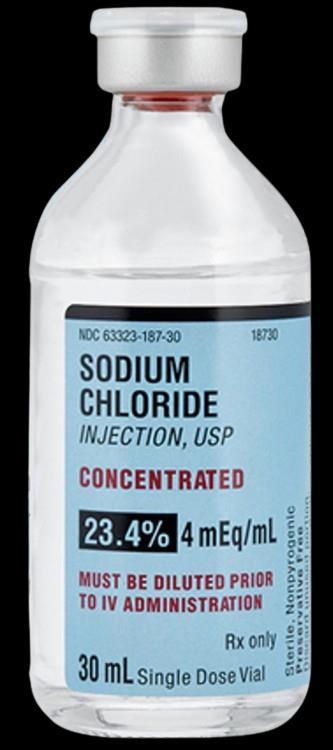

Treatment*: Oral rehydration salts; IV/IO Lactated Ringers PRN; antibiotics PRN.

Vaccine: Dukoral (from the Netherlands) and Shanchol (from India) are available as a 2-dose series; vaccine trials have shown a ~65% efficacy after 5 years.1

Reinfection: “Infection with cholera provides short-term protection against reinfection, particularly by a homologous strain In endemic areas, most residents have acquired protective antibodies by early adulthood ”1

Cholera gravis: The term for a severe case of cholera in which death may occur within a few hours. Case fatality rate (CFR) is upwards of 50%. With aggressive rehydration the CFR can be reduced to <1%.

Cholera sicca: “An unusual form of the disease whereby fluid accumulates in the intestinal lumen circulatory collapse and death can occur in the absence of diarrhea.”2

* See following page for specifics on treatment

Cholera Treatment: Depends upon degree of dehydration and patient age, as detailed below:

Mild dehydration criteria: 5% loss of bodyweight*

Moderate dehydration criteria: 7% loss of bodyweight*

Give oral rehydration salts (ORS) over 4-6 hours to match fluid lost; “continuing losses are replaced, over 4 hours, via a volume of ORS equal to 1.5 times the stool lost in the previous 4 hours”. 1

In patients younger than 14 years old, give 30 mg elemental zinc per day to decrease severity and duration of disease.

*AND/OR two or more of the following signs: Sunken eyes, absence of tears, dry mouth and tongue, thirst, decreased skin turgor.

Severe dehydration criteria: 10% loss of bodyweight; AND/OR patient meets moderate dehydration criteria plus any of the following signs: Lethargy or unconsciousness, inability to drink, weak radial pulse.

Administer IV/IO rehydration with solution containing the following electrolyte profile (all units are in mEq/liter): 130 sodium, 4 potassium, 3 calcium, 110 chloride, 28 lactate (Lactated Ringer’s is the fluid of choice).

If patient age <1 year old: administer 30mL/kg in the first hour, reassess, then give 70 mL/kg over next 5 hours.**

If patient age >1 year old: administer 30 mL/kg in the first 30 minutes, reassess, then give 70 mL/kg over next 2.5 hours.**

**Once circulatory collapse has been reversed, most patients can switch from parenteral fluid therapy to ORS to round out the 10% bodyweight deficit.

Adult: single dose of 300 mg doxycycline*** (alternatives include erythromycin (500 mg q6h x3 days), azithromycin (1 g single dose), or ciprofloxacin (1 g single dose or 500 mg q24h x 3 days))1,2

Children: Erythromycin (50 mg/kg/day divided q6h for 3 days) or azithromycin (20 mg/kg single dose)

***Avoid doxycycline in pregnant patients

1 Heymann DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 20th edition. Alpha Press; 2015. 102-107

2 Magill AJ, Ryan ET, Hill DR, et al. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9th edition Elsevier; 2013 448

Vibrio cholerae bacteria are highly motile and move in the manner of “shooting stars” under dark-field microscopy.

“ORS, originally developed for the treatment of cholera…is one of the landmark medical achievements of the 20th century.” Hunter’s Tropical Medicine

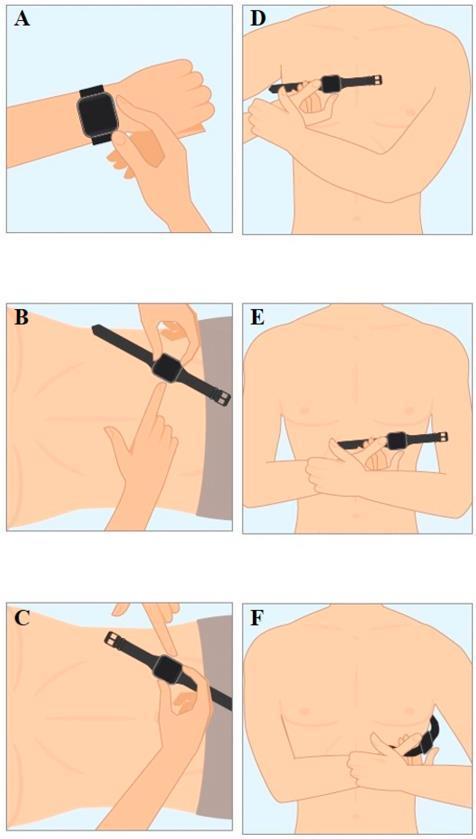

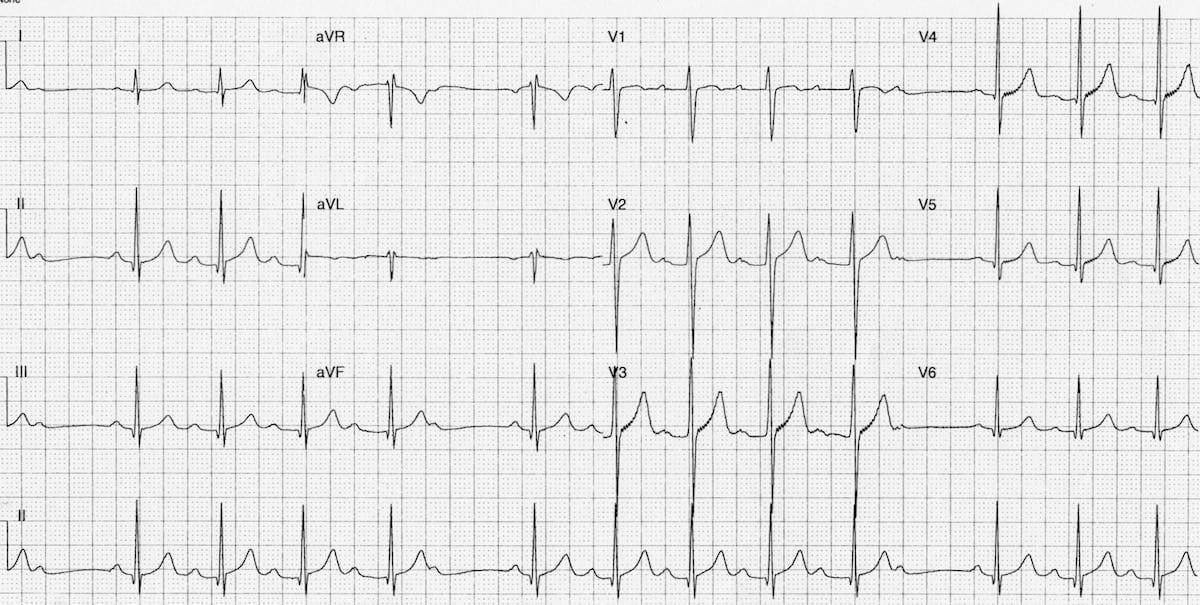

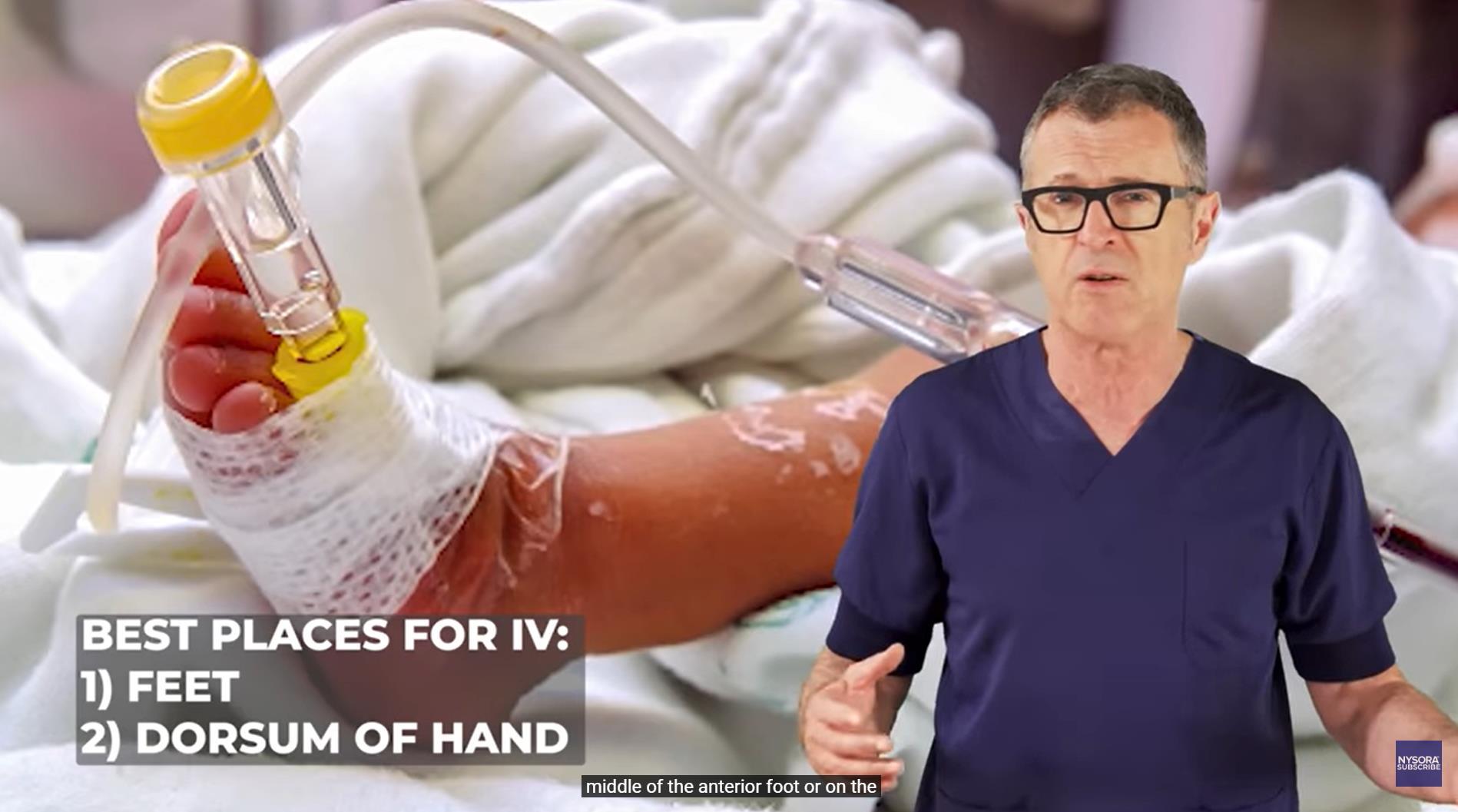

For the Remote Medic, we don’t have enough space or ability to carry a full LifePak 20 or Zoll X series defibrillator when we are working out of our rucksack clinic. We need the ability to conduct 12-lead investigations due to the aging population we are treating in the remote, austere and resource-limited areas in which we work.

When researching content for CoROM’s new Austere Critical Care Field Guide, I came across this study that showed how to find and calculate all 12 leads using a handheld 2-lead device. Leads I, II, III, and the six precordial leads are easy to obtain. To calculate the aVF, aVR and aVL, you need to do a bit of calculation. Here is a video describing that process.

This technique works with the ECG function found on most smartwatches. I take my lead II reading several times daily using my Samsung watch, and I have compared that to a full defibrillator and found comparable results.

This study showed promising results. This single study showed that you could use this technique to find your 12-lead results from just a smartwatch.

This study from the American Heart Association showed the high accuracy of a smartwatch-derived ECG in diagnosing bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias, and cardiac ischemia.

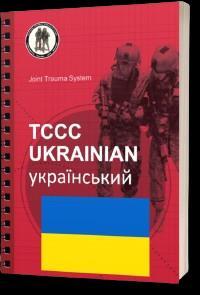

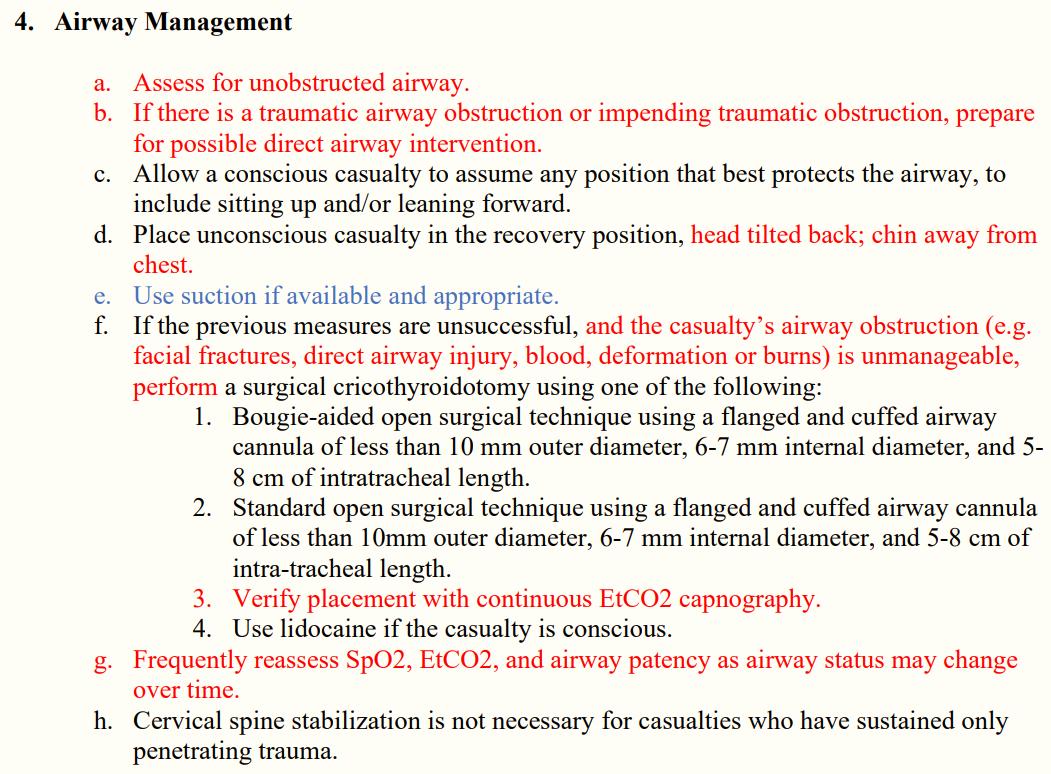

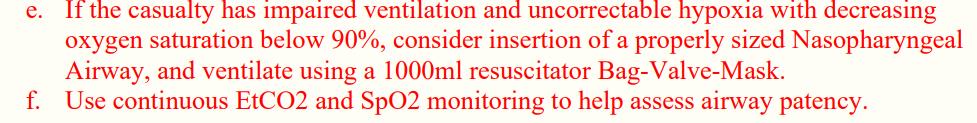

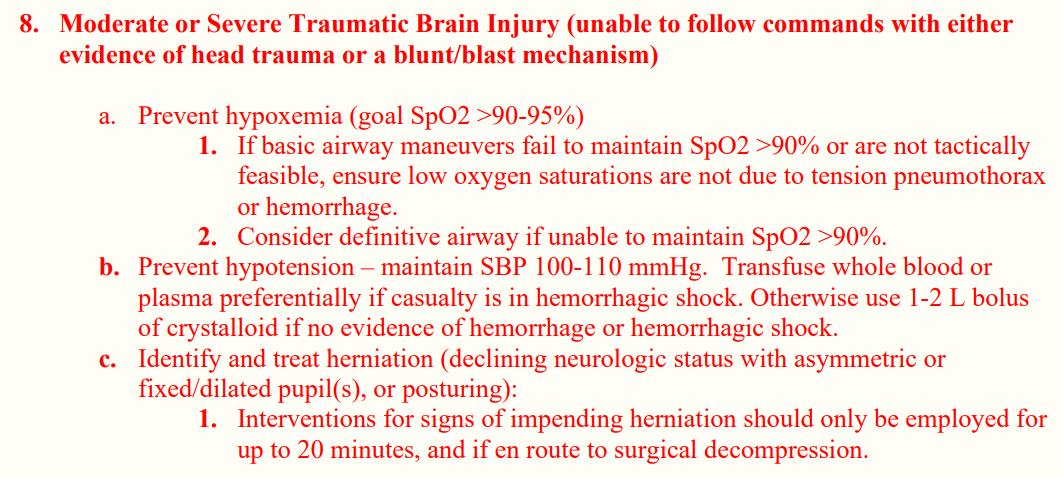

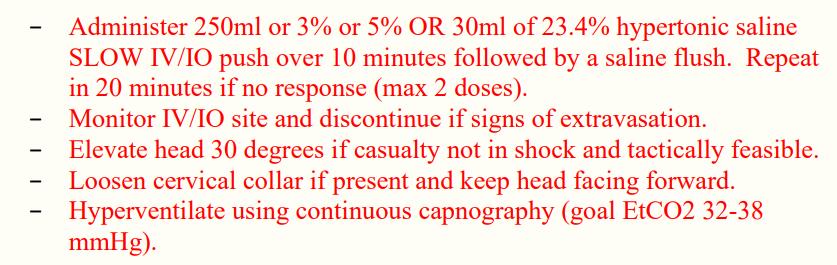

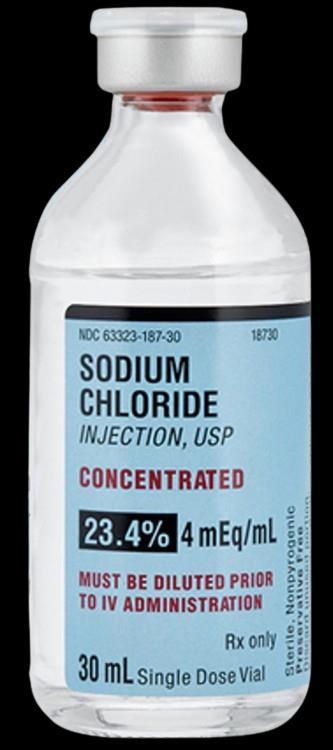

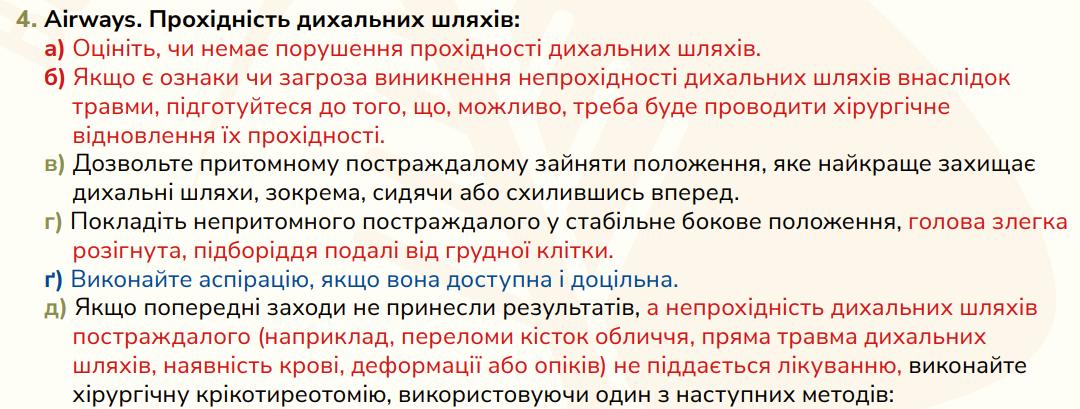

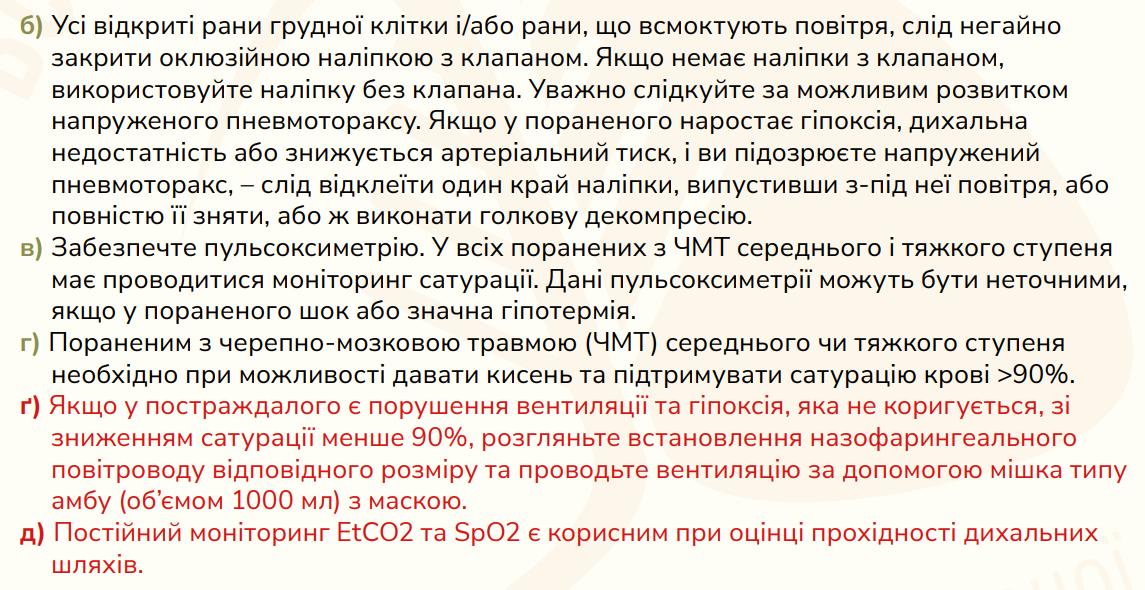

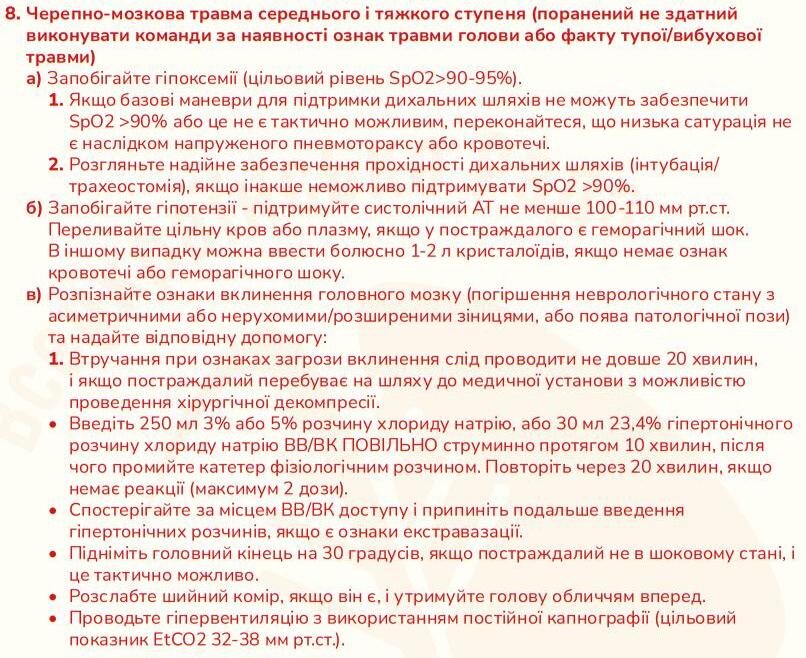

The Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care updated the TCCC guidelines on 25 January and can be found here: https://tccc org ua/en/collection/recommendations

The TCCC guidelines are available in both English and Ukrainian languages.

Jason Jarvis MSc 18D NR-Paramedic

Jason Jarvis MSc 18D NR-Paramedic

In this guidelines only airway management and the management of head trauma were updated, the text of which is printed in red.

Screenshots of these updates follow.

https://tccc.org.ua/en/guide/tccc-guidelines-2021-ukr

https://tccc.org.ua/en/guide/tccc-guidelines-2021-ukr

Which atrioventricular block is shown?

A. First degree

B. Third degree

C. Second degree, type 1

D. Second degree, type 2

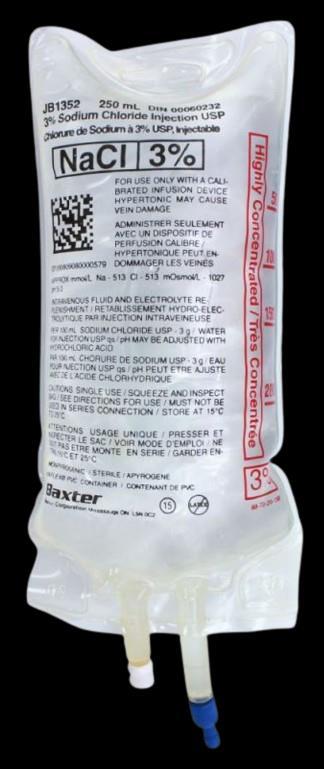

You have been deployed to Madagascar to staff a remote clinic during a plague outbreak. A 10-yearold 35kg semiconscious girl is brought to you for emergency care. She fell off the back of a motorcycle at high speed and was not wearing a helmet. The girl has GCS 9 (2,3,4), exhibits widening pulse pressure, and ultrasound reveals an optic nerve sheath diameter of 5.3mm. Top cover advises treatment of her increased intracranial pressure using 3% saline via femoral IV, at a dose of 8 mL/kg and at a rate of 40 mL/hour. Using a 60 gtt/mL intravenous giving set, at how many drops per minute should

Species Identification

This snake is most

A. Coral snake

B. Scarlet kingsnake

C. Red-bellied keelback

D. Blotched palm pit viper

The condition shown above is most likely a result of which of the following pathologies?

A. Dracunculiasis

B. Rat lungworm disease

C. Alpha-gal meat allergy

D. Chronic schistosomiasis

Answers will appear in the Summer 2024 Compass

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: D. Hyperparathyroidism

Clinical calculation: Add 0.25mL of epi 1:1000 to the 50mL bottle

Species identification: D (Glossina genus tsetse fly)

Clinical case: B. Transfuse blood from donors 3, 6, 8, and 10

A selection of medical references and gear

Medical Reference (editor’s picks)

Gear

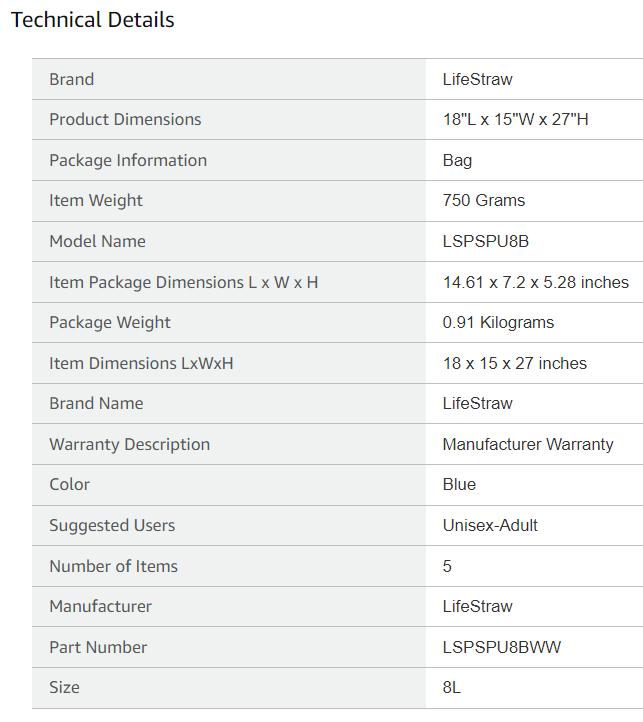

LifeStraw Ultrafilter Membrane Water Purifier available from amazon.com

“Removes 99.99% viruses, bacteria, parasites. 30 liter per hour gravity flow, 18,000 liters lifetime capacity.”

A selection of medical podcasts

Episode 27 – James Roth on Mt. Everest lessons and medical expeditions

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3mHpJvacu8YfHBAWi7dNcn

Episode 78 – The case of the hypervaccinated German

https://open.spotify.com/episode/7yrNs4YRVbVkxVOJKpaZnI

Episode 174 – John and Paul on the invention of the Abdominal Aortic Junctional Tourniquet (AAJT)

https://open.spotify.com/show/3jf8IZONKw2QiR5lkUCQDg

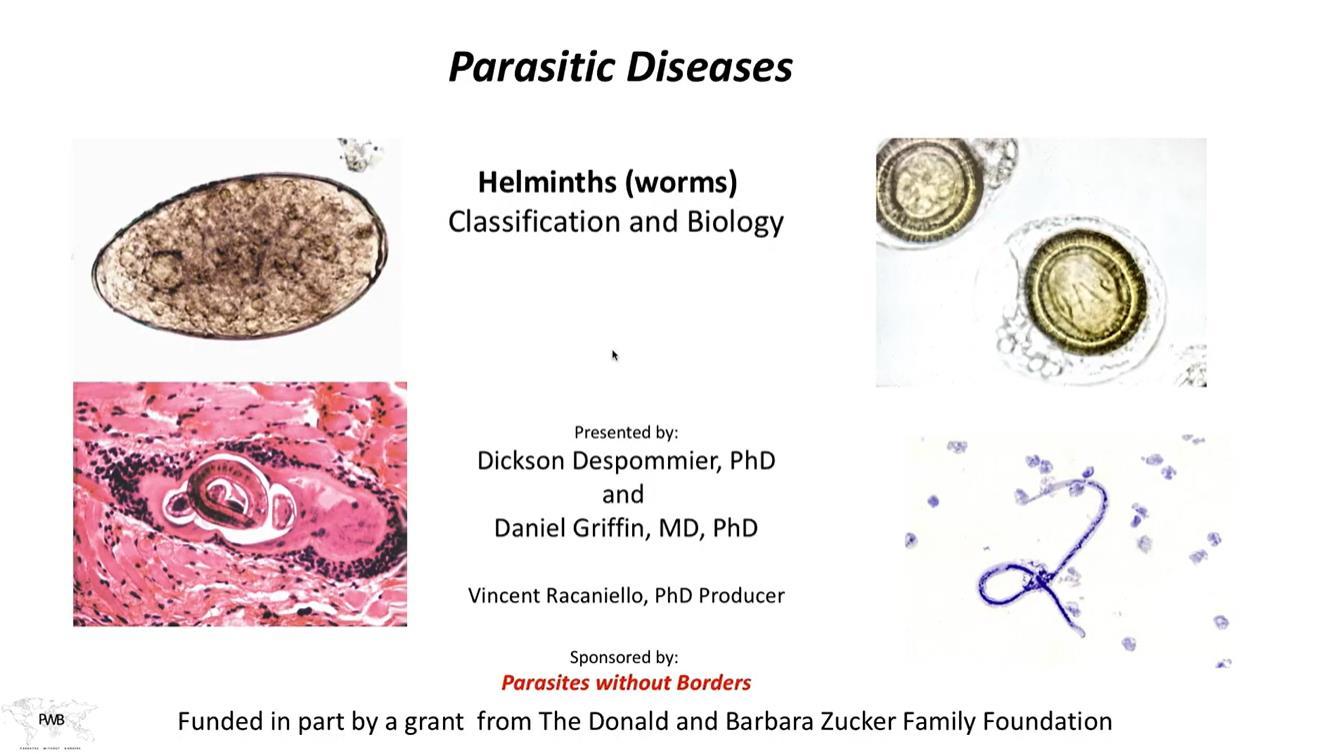

https://parasiteswithoutborders.com/parasitic-diseases-lectures/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HXnekKicGmc&t=128s

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Hynes AM, Murali S, Bass GA, et al. 2023;23(4):81-86.

doi:10.55460/AAZW-R052

Nine males with gunshot wounds transported to the hospital by police were included in this study. Eight patients were pulseless on arrival, and one became pulseless shortly thereafter. Seven (78%) sternal-IO placements were successful, including six TALON devices and one of the three FAST1 devices, as FAST1 placement required attention to Operator positioning following resuscitative thoracotomy. Three patients achieved return of spontaneous circulation, two proceeded to the operating room, but none survived to discharge.

Sternal-IO access was successful in nearly 80% of attempts. The indications for sternal-IO placement among civilians require further evaluation compared with IV and extremity IO access.

Wilderness & Environmental Medicine

Hughey SB, Kotler JA, Ozaki Y, et al. 2024;35(1):57-66.

doi:10.1177/10806032231220401

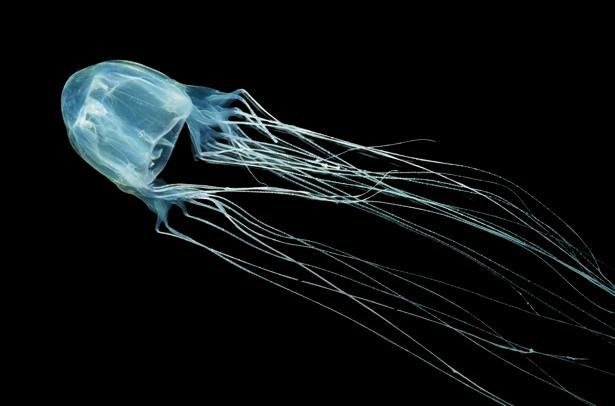

Okinawa prefecture is a popular tourist destination due to its beaches and reefs The reefs host a large variety of animals, including number of venomous species Because of the popularity of the and marine activities, people are frequently in close contact dangerous venomous species and, thus, are exposed to potential envenomation. Commonly encountered venomous animals throughout Okinawa include the invertebrate cone snail, sea urchin, crown-of-thorns starfish, blue-ringed octopus, box jellyfish, and coral The vertebrates include the stonefish, lionfish, sea snake, and moray eel Treatment for marine envenomation can involve first aid, hot water immersion, antivenom, supportive care, regional anesthesia, and pharmaceutical administration. Information on venomous animals, their toxins, and treatment should be well understood by prehospital care providers and physicians practicing the prefecture

Blue-ringed octopus

Moray eel

Box jellyfish

International Journal of Molecular Sciences

Smyk JM, Szydłowska N, Szulc W, et al. 2022;23(20):12244.

doi:10.3390/ijms232012244

ABSTRACT

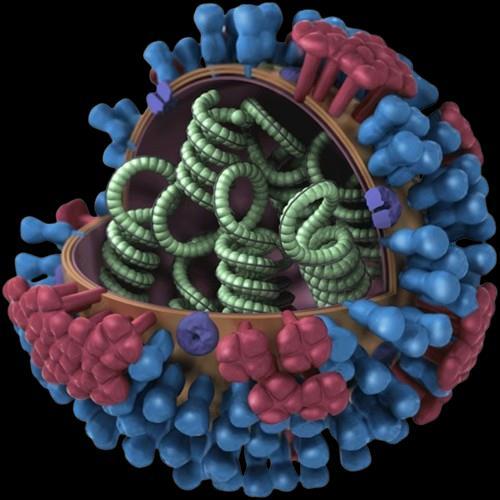

Influenza virion.

Diagram credit: CDC

Viral evolution refers to the genetic changes that a virus accumulates during its lifetime which can arise from adaptations in response to environmental changes or the immune response of the host Influenza A virus is one of the most rapidly evolving microorganisms Its genetic instability may lead to large changes in its biological properties, including changes in virulence, adaptation to new hosts, and even the emergence of infectious diseases with a previously unknown clinical course Genetic variability makes it difficult to implement effective prophylactic programs, such as vaccinations, and may be responsible for resistance to antiviral drugs The aim of the review was to describe the consequences of the variability of influenza viruses, mutations, and recombination, which allow viruses to overcome species barriers, causing epidemics and pandemics Another consequence of influenza virus evolution is the risk of the resistance to antiviral drugs Thus far, one class of drugs, M2 protein inhibitors, has been excluded from use because of mutations in strains isolated in many regions of the world from humans and animals Therefore, the effectiveness of anti-influenza drugs should be continuously monitored in reference centers representing particular regions of the world as a part of epidemiological surveillance

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Melau J, Bergan-Skar P, Callender N, et al. 2023;23(4):87-91

doi:10.55460/7NII-VT7T

ABSTRACT

Background: The war in Ukraine urged a need for prompt deliverance and resupply of tourniquets to the front Producing tourniquets near the battlefront was a feasible option with respect to resupply and cost Methods: A locally produced 3D-printed tourniquet (Ukrainian model) from the "Tech Against Tanks" charity was tested against commercially available and Committee of Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC)-recommended tourniquets (C-A-T and SOF TT-W) We tested how well the tourniquets could hold pressure for up to 2 hours Results: A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed significant differences between the groups (p<.05). Post-hoc testing revealed a significant difference between the C-A-T and the Ukrainian tourniquet (p=.004). A similar significance was not found between the SOF TT-W Wide and the Ukrainian model (p= 08) Discussion: The Ukrainian model can hold pressure as well as the commercially available tourniquets There is much value if this can be produced close to the battlefield. Factors including logistics, cost, and selfsufficiency are important during wartime. Conclusion: We found that our sample of 3Dprinted tourniquets, currently used in the war in Ukraine, could maintain pressure as well as the commercially available tourniquets Indeed, our tests demonstrated that it could maintain a significantly higher pressure.

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-forprofit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries

The College was founded in 2016 and is governed by a Board of Regents supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority License No 2018-022

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments

Tropical Medicine

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

Austere Medicine and Prolonged Field Care

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

Austere Critical Care

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources.

CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

MFSLR Dates TBD

NORWAY

APUS 9-10 September

AEC Dates TBD

Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

MALTA

REMT 1-6 April

APUS 13-14 April

ICARE 15-19 April

SOMSA Conference 13-18 May 2024

Tactical Medicine Review (Clark, HolmstrØm)

Improvised Medicine (O’Kelly, Mallinson, Shertz, Loos)

Austere Clinical Laboratory Diagnosis (O’Kelly)

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice

Doctor of Health Studies

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Award in Tropical & Expedition Medicine

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Basics of Resource Limited Critical Care

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Ghana National Ambulance Service

27-30 May REMT 13-18 October APUS 2-3 November ICARE 4-8 November

TTEMS 11-15 November Medicine in the Mediterranean conference 31 Jan-2 Feb 2025

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

ACC

Acute Critical Care

AEC Austere Emergency Care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.edu.mt

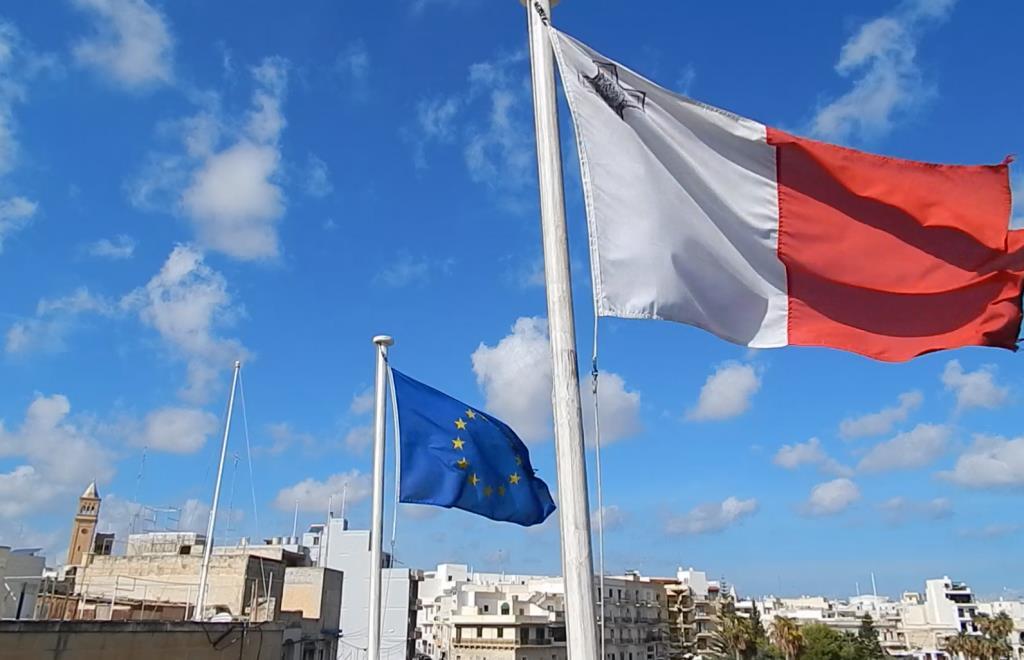

Medicine in the Mediterranean 2024 was a resounding success!

Huge thanks to all attendees and the fantastic group of speakers and faculty who made it all possible! We’re making plans for MiM 2025 –please join us.

Call for Speakers:

The Medicine in the Mediterranean Conference, sponsored by the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine, is seeking dynamic speakers to present on topics related to prehospital, remote EMT, and austere medicine. The conference will take place from January 31st to February 2nd, 2025, in the historic city of Valletta, Malta. We are inviting passionate experts in wilderness prehospital care, remote paramedic practice, and austere medicine to share their knowledge and experiences with our diverse audience. Presentations should be engaging, current, and approximately 1 hour in length.

If you are a leader in your field and have valuable insights to offer in these areas, we encourage you to submit your proposal to be a speaker at our conference. This is an excellent opportunity to connect with fellow professionals, exchange ideas, and contribute to the advancement of prehospital and remote medical care.

Submission Guidelines:

– Presentation topics should focus on wilderness prehospital care, remote EMT practices, or austere medicine.

– Proposals should include a brief description of the presentation, outlining key points and learning objectives.

– Speakers must be able to deliver engaging and informative presentations that cater to a diverse audience.

– Presentations should be approximately 1 hour in length, including time for Q&A.

Important Dates:

– Submission Deadline: 1 August 2024

– Notification of Acceptance: 15 September 2024

Please submit your proposal and your CV along with any inquiries to info@corom.edu.mt with the subject line to include “MiM Presentation Idea” by the submission deadline. We look forward to receiving your submissions and welcoming you to the Medicine in the Mediterranean Conference in Valletta, Malta!

Mission to Heal goes where medical need is greatest. We visit remote regions to teach basic surgical skills to local healthcare practitioners so they can care for their community year-round. Due to our educational approach, we need a variety of expertise on these missions. We welcome the following specialists to volunteer with us:

Nurse Anesthetists

Tropical Medicine Specialists

Obstetricians & Gynecologists

Optometrists & Ophthalmologists

Dentists & Oral Surgeons

General Surgeons

OR Nurses

Triage Nurses

Medical & Dental Students

Residents

As you can see, it’s a wide-ranging list – but it’s not all inclusive. If you have a specialty that’s not listed here, but would love to volunteer with us, there is still a place for you!

Why volunteer?

- Get a transformational learning experience where you learn just as much as you teach.

- Experience a culture outside of your own.

- Experience how healthcare is practiced in other countries.

- Use your expertise to benefit the less fortunate.

As one of our volunteers said to us, “We want to volunteer with you because you actually do.”

Useful links:

Volunteer with Mission to Heal - https://missiontoheal.org/apply/ Volunteer FAQ’s - https://missiontoheal.org/faqs/

Our approach to missions - https://missiontoheal.org/approach/ Volunteer reflections - https://missiontoheal.org/blog/

Questions about M2H missions – samuel.jangala@missiontoheal.org

2024

Mission Dates and Countries:

Kenya II: March 1 – March 16

Kenya III: April 12 – April 27

Uganda I: June 15 – June 29

Uganda II: August 10 – August 24

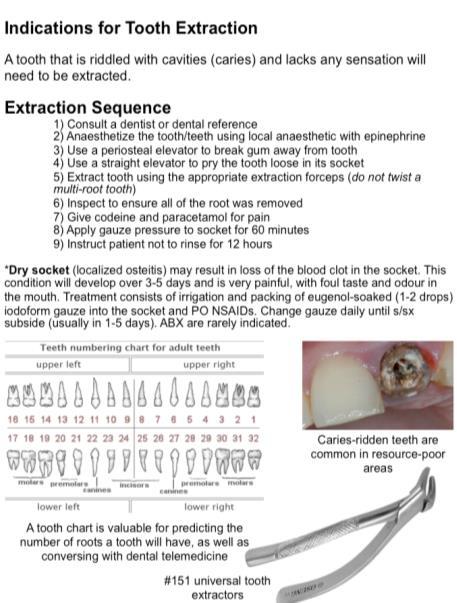

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

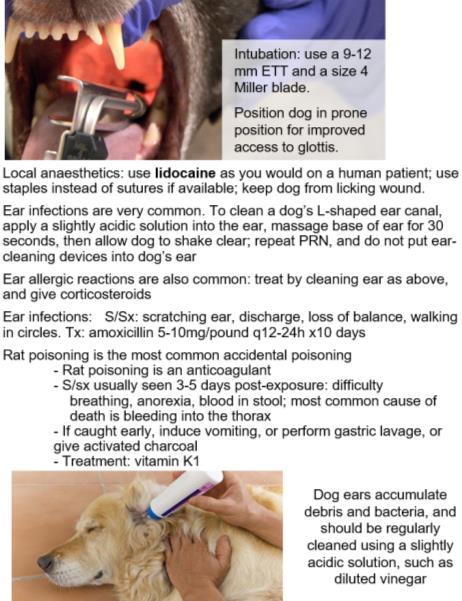

Canine medicine

…and much more!