Winter 2019

Theofficialnewsletterofthe CollegeofRemoteandOffshoreMedicine Foundation

CONTENTS PAGE About CoROM 3 Dean’s Desk 4 Message From the Academic Board 5 Photo Gallery 7 Course Calendar 8 Where Are They Now? 9 Washington Sisimayi on providing medical coverage in the Middle East Case Report 11 Dr. Michael Shertz on rattlesnake envenomation Special Report 13 Nicole Foster on the 2019Australian Tactical Medicine Conference Trends in Traumatology 15 Jason Jarvis on the CRASH-3 study Selected product information for tranexamic acid 16 Test Yourself 17 ECG, drug calculation, and clinical case Resources 18 Aselection of medical references and gear Journal Watch 19 Pit latrines:Apotential risk factor for latrodectism in SouthAfrica? Air pollution: the emergence of a major global health risk factor Eastern Equine Encephalitis – another emergent arbovirus in the U.S. The reliability of NIBP measurement through layers of autumn/winter clothing Book Review 21 West Nile Story by Dickson Despommier

Cover photo: The view of Mount Kilimanjaro from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center, Tanzania.

Winter 2019 2

Photo courtesy of Kaylyn Joyce

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntaryAcademic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

What does CoROM specialise in?

About CoROM 3

Dean’s Desk

The College has been busy this Autumn semester. We ran our critical care course in Saint James Hospital, Malta in October with delegates joining us from three continents. Dr. Csaba Dioszeghy and Dr. Gorove spent the week with our delegates preparing them for the IBSC board exams, after which they sat exams for the Flight Paramedic and Critical Care Paramedic certifications. The College is authorised to offer those exams any time we like, as we are now a fully-approved exam centre for ProMetric, which hosts the IBSC board exams.

18E MA FAWM DipPara CCP-C TP-C

In addition, we had a full house for the Remote EMT course which ran this November. The waiting list has been filling up as well for the next course in 2020.

Our first delegate for the Kilimanjaro SAR clinical experience arrives in a few weeks. We look forward to hearing how many casualties he will evacuate off Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru. He will spend a lot of time in the only altitude clinic inAfrica, located in Moshi, Tanzania at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro.

One of our faculty – Tim Cranton – spent some time on the Budapest HEMS service with Matyas Solténszky, one of CoROM’s Critical Care Paramedic faculty members. Our clinical placement in Budapest is a fantastic location for getting hands-on experience with critical casualties as well as medical evacuation with a Eurocopter 135.

Meanwhile, we are preparing for the Spring semester, which kicks off in January with two of our faculty returning to Kibosho district hospital, located 14 kilometers up the forested slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. CoROM will be donating medical kit and providing training programmes for their remote healthcare practitioners, as well as conducting research on the mountain, which focuses on the early assessment and management of the critical casualty and access to medical evacuation to tertiary clinics at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) in Moshi.

The Spring semester will see twelve of our first year HDip students go through the classroom phase of the Remote Paramedic programme. They will have three of our faculty putting them through the rigors of remote clinical practice using live simulated casualties. Those who successfully pass that module are then invited to continue to KCMC in Tanzania for their clinical placements.

It has been a busy few months for the College and we are looking forward to the slower paced holiday season so we can catch up on administrative matters. We wish the very best for our graduates, our faculty and our current students as they enjoy the holiday season.

4

Aebhric O’Kelly

CoROM faculty members Matyas Solténszky (left) and Tim Cranton working the HEMS program in Budapest, Hungary

Message From the Academic Board

Why do research?

As I go deeper into my journey in life and medicine, I find I have more questions than answers which, being on the more OCD side, does not sit well with my psyche. Medicine is frequently described as an art and science, but there seems to be a growing trend towards protocol driven medicine, which is the antithesis of the former. Because of my desire to practice both theArt and Science of medicine, I find myself drawn to clinical medical research.

What would make a busy clinician want to take the time out of their schedule to learn more about doing research and then help lead the way with it? An easy answer is to appeal to the altruistic side of humans with the old motto “To learn, To teach, To heal, To discover.” By embarking on a research journey, one can answer basic questions that clinically make a difference, which could improve survival, decrease suffering, improve resources and allow for further research to be built upon your work.

All of these are worthy objectives for any healer in the medical realm; on the more personal side, maybe you just want to be part of something bigger than yourself, or something that is farther-reaching. Ask yourself: how big is the impact you have on treating one patient? Taking the next step – how farreaching is the effect of teaching someone how to perform a medical skill? Finally, ask yourself what the net effect is if you were part of a research project that discovered a treatment option?

Does the last question sound too complex for you to work? Let’s suppose you learned – through research of local tribal hygiene practices – that a very remote village had poor hand hygiene which caused significant disease. With this knowledge, you teach villagers to make soap using locally available materials. Does that sound that complex? It might not sound “sexy” but when you think about the overall effect that simple project could make, it truly could be eternal.

Another reason to consider doing research is as you do it, you will learn to understand how it is done and the meanings behind all the terms, and how to be able to critically evaluate the literature. Do you find you’re confused by terms such as cohort study, meta-analysis, randomized controlled study, systematic reviews, retrospective, case-study and prospective studies?

5

Dr. Drew Stephens MD, FACEP CoROM Head of Research

Dr. Drew Stephens leads CoROM’s research projects at Kibosho Regional Hospital, Tanzania

My favorite scenario is when I have a student with a medical question who has googled it only to get 10 different answers and they are now more confused than before. Or, during the google search they find a research paper telling them that “this research says X is the best answer for the patients,” only to be followed by another research paper that says, “X is actually harmful to patients.”

Can you imagine the research paper ancient Egyptians would have published about the practice of bloodletting?

If you talk to researchers and other practitioners who have the ability to critically evaluate the literature, they will tell you the devil is in the details. You must understand if correct research methods are being used to look at X, coupled with appropriate application of that data. It is almost impossible to participate in research and not start to learn your way through these issues.

As the College expands physically and academically, it is time for it to grow and start to lead in medicine, within our area of expertise that is “remote and offshore medicine.” Over the last year, the College started a research department and is kicking off exciting projects with Kibosho Regional Hospital in Tanzania. In the meantime, there are many other worthwhile programs that can be explored and learning to be done through the process.

The goal for the College is to be able to give back to the communities we are working with throughout the world, to help them answer questions to key issues that are endemic to local issues. In return, we become more proficient in delivering medical care in remote and offshore areas.

“If I have seen further than others it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Sir Isaac

Newton

6

Dr. Stephens delivering medications to Kibosho Regional Hospital, Tanzania

Photo Gallery

Trauma training at

emphasizes the use of both manufactured and improvised tourniquets

7

CoROM

CoROM’s newest training centre at St. James Hospital in Sliema, Malta

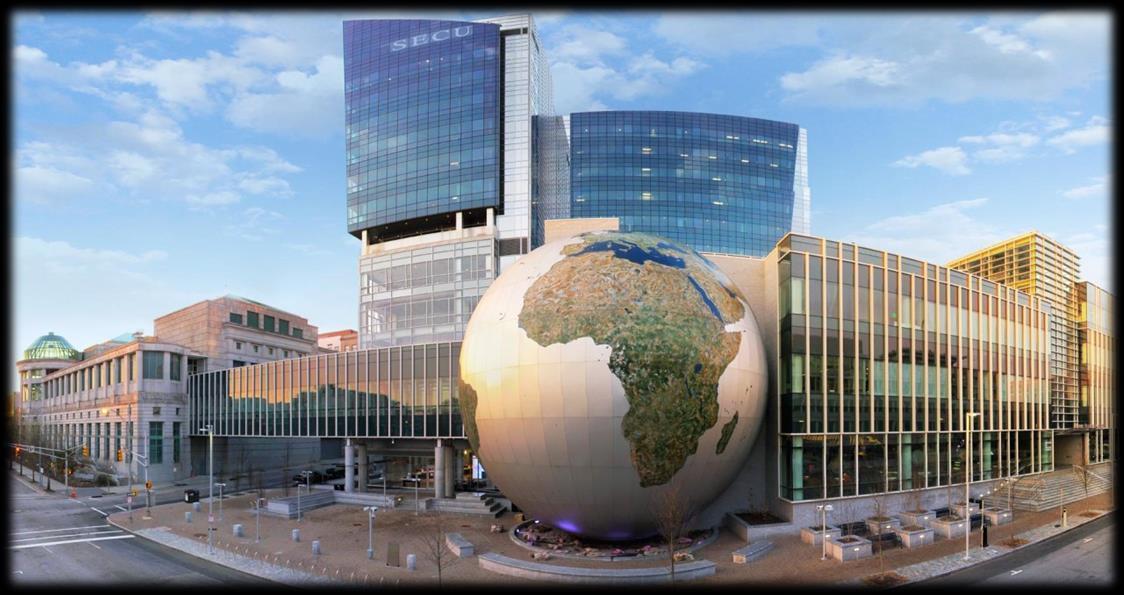

Exterior view of CoROM’s training centre at St. James Hospital in Sliema, Malta

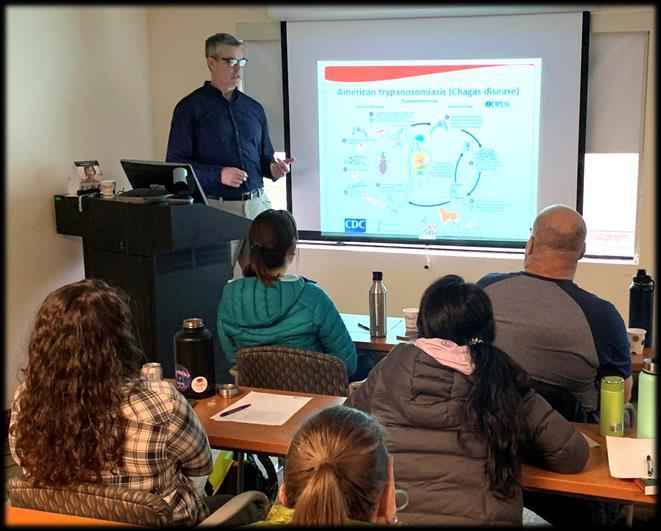

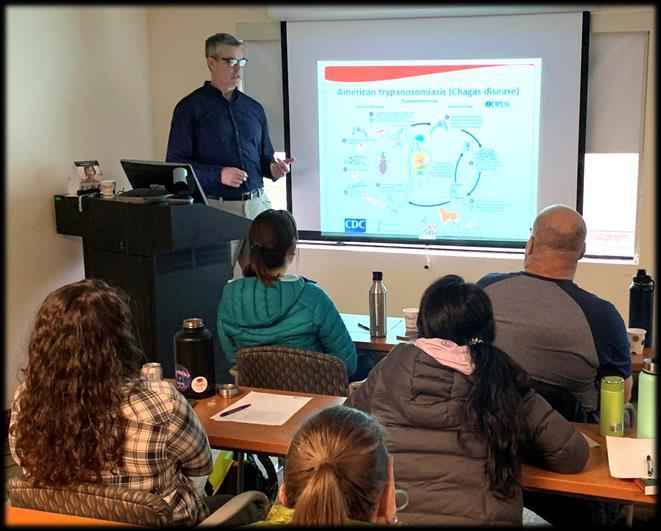

CoROM Tropical Medicine Lead Jason Jarvis presenting a Chagas disease case at the Harborview ACLS EP course in Seattle, Washington

CoROM Education Manager Neil Coleman supervising a medical training scenario

Splinting class at the Remote Emergency Medical Technician course

Course Calendar

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA

Special Operations Medical Association Scientific

Assembly 11-15 May

Tactical Medicine Review with IBSC exams

Malaria workshop

MALTA

eITLS 22 March

FiCC 6-12 April

ACLS 16-17 April

eITLS 18 April

TTEMS 23-27 March

eITLS 15 November

TTEMS 16-20 November

RAMS 30 November-4 Dec 2020

RMLS Spring Semester 2021

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON

Suturing Fundamentals 14 January

GERMANY

NSOCM TTEMS

18-22 May (closed course)

CMC Conference TropMed workshop

1-2 July

LEGEND

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

CC-P International Critical Care Paramedic (IBSC)

TANZANIA

TTEMS 3-7 August

eITLS International Trauma Life Support Completer Course (follows ITLS eTrauma course)

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

NSOCM NATO Special Operations Combat Medic course

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expeditionary Medical Skills

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitude

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Level 3 Health and Safety for the Workplace

Level 3 Food Safety for the Workplace

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org. Please address newsletter correspondence to editor@corom.org.

8

Where Are They Now?

CRP and TTEMS student Washington Sisimayi on providing medical coverage and training in the Middle East

After completion of the 2019 CoROM Remote Paramedic and TTEMS courses in Tanzania I resumed my work in the Middle East, where I have now been training field medics as well as ushering them into the prehospital fraternity.

I have also been part of a team setting up field trauma packs and converted vans into designated ambulances for programmes in northeast Syria to cover expats. The CoROM TTEMS course also helped in broadening my view and approach to medical care in the remote site arena. I wish to continue progressing and eventually take the CoROM RAMS course.

It has been good getting to use many of the skills I learned with CoROM – setting up satellite clinics and equipment using the minimum-better-best approach, plus training and updating skill sets for the national medics.

I am planning to head back to Tanzania or SouthAfrica soon for more clinical experience as well as working through my clinical hours. I will be on the lookout for more wilderness and expedition opportunities in the near future.

9

Washington Sisimayi EMT, ALS CoROM IP Student

Washington Sisimayi conducting medical training

10

Case Report

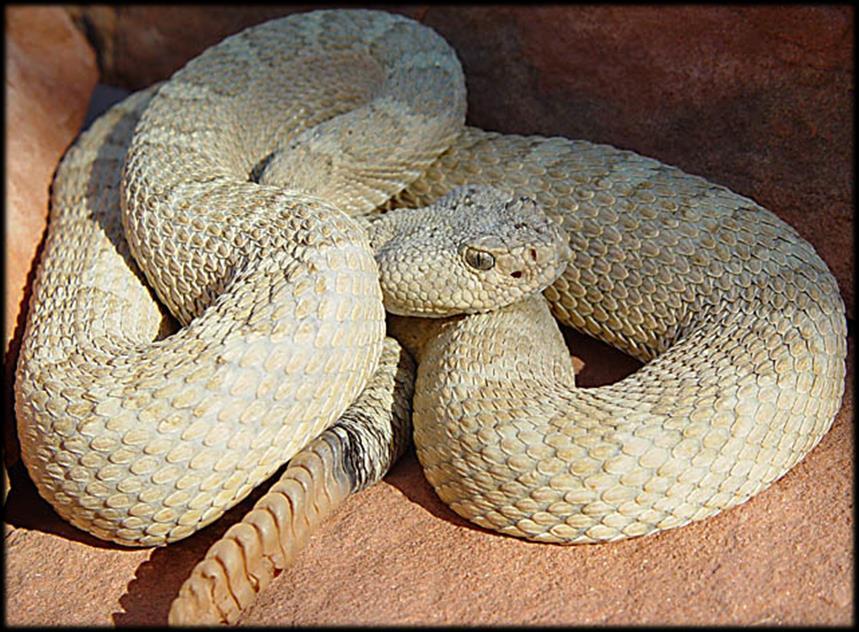

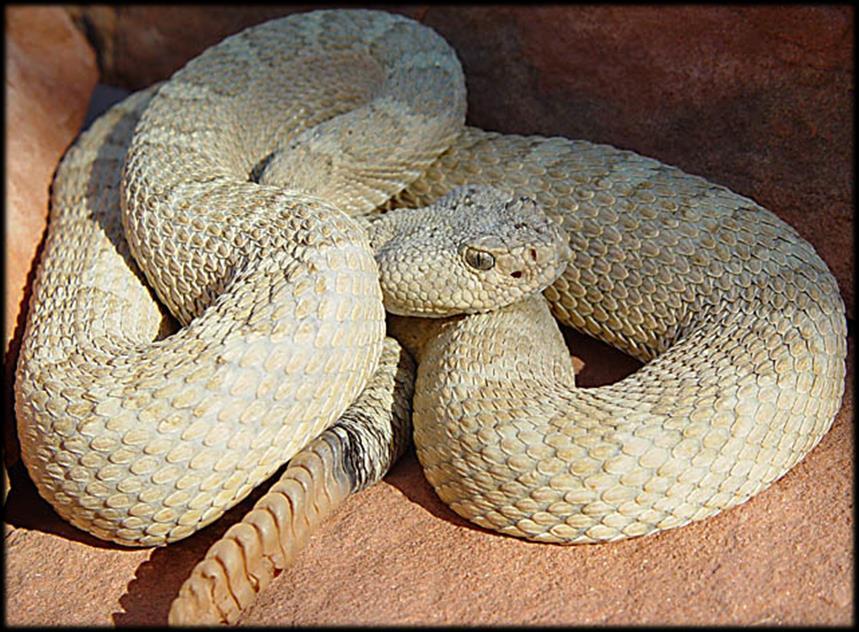

Western Rattlesnake envenomation with Dr. Michael Shertz

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former U.S. Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

A23-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department after being bitten on his right thumb an hour before by a Western Rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus) he picked up as a souvenir while hiking in Eastern Oregon.1 He has normal vital signs, minimal bleeding from two parallel punctures, and thumb pain. The patient brought the snake to the ED as proof of the speciation.

Although his ED laboratory testing was normal, his thumb and hand quickly began to swell. Fifteen minutes later, the swelling had progressed to his forearm.

The venom from pit vipers is predominantly hemotoxic, causing decreased fibrinogen, decreased platelets, and increased platelet consumption at the bite site. Local and systemic effects can include tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, sweating, and vomiting. In severe envenomation, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or rhabdomyolysis can also occur.

“Dry bites,” in which a venomous snake bites without injecting venom, occur in 20 - 30% of viper bites, 50% of elapid, and 75% of sea snake bites.2

There is very little evidence base to make firm recommendations regarding the prehospital management of viper bites. There is research showing that incision / excision, venom extraction devices, tourniquets, chill methods, and electroshock have no efficacy. No currently recommended prehospital treatment has been shown to alter outcome.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

11

Crotalus oreganus, the Western rattlesnake

Immediate treatment of venomous snake bites - besides the typical ABCs - is the determination of envenomation. Local or systemic symptoms or abnormal laboratory results (new anemia, decreased platelet count, increased prothrombin time / PT) indicate envenomation.

Swelling, unless minimal, alone or progressive, is enough to warrant antivenom treatment.

Antivenoms are either monovalent, providing coverage for only one species of venomous snake, or polyvalent for multiple species. CroFab is one of the most common antivenoms in the US. It is polyvalent, provides coverage for all North American pit vipers, and possibly some protection for Central and SouthAmerican species.2

Prophylactic antibiotics are not generally indicated in snake bites, although good wound care is. Splinting of the extremity, padding between fingers, and elevation can be helpful. Hemorrhagic or bullous vesicles should be debrided in 3 to 5 days.

The patient received four vials of CroFab antivenom and his swelling did not continue to progress. He was admitted for serial observations and pain control.

1 The patient was initially rushed into the ED with a struggling life in a blanket; the nurses, assuming it was an infant who had also been bitten, were shocked to find the patient’s dog, the individual first bitten by the snake when it got loose in the car coming home. The dog was rushed to an emergency vet and was successfully resuscitated. The ED doc would like it noted he offered to resuscitate the dog but was denied the privilege.

2 Animal Poisons in the Tropics chapter in Tropical Infectious Disease, 2nd edition.

12

Special Report

Nicole

on the 2019Australian Tactical Medicine Conference

The Australian Tactical Medical Association (ATMA) hosted its second Australian Tactical Medicine Conference in Brisbane 18-20th September 2019.ATMAis a not-for-profit that represents tactical medicine providers in emergency services, military, police and other special operations groups. The theme of the ATMAconference this year was ‘faces of high threat medicine’ and was able to capture the spectrum of the patient’s journey from point of injury all the way through to recovery. The conference explored how people interact within this niche area of medicine, with a focus on military and deployed medicine, civilian tactical medicine and human performance.

Pre-conference workshops were held the day prior to the conference and included workshops such as prolonged field care, improvised tourniquets, TECC, medical support planning and introduction to REBOA. I attended the morning session on Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA), which has received a lot of coverage in the pre-hospital environment. We had some interesting discussions surrounding the use of this procedure outside of the hospital and, like most things in medicine, it is not the skill that is the hardest hurdle, but the clinical decision-making of when to use this procedure and the resources available to a patient after the procedure is done. It was an enlightening introduction and I’m cautiously optimistic about its future in pre-hospital and austere environments. The afternoon was spent working in teams roleplaying a hostage scenario and the medical support planning that goes with these events. The who, why, where, and how of medical support in a tactical setting was laid out, and we (hopefully) saved our hostages!

There were some fascinating speakers and topics over the next two days, including local perspectives from the 2019 Townsville floods, the Christchurch terror attack and the Sydney Lindt café siege to international events such as the Thailand cave rescue and Mosul, Iraq. Topics varied from load carriage, distribution and performance to surgical management of manmade mass casualties and how to improve survival in intentional active shooter incidents. The basics were reinforced, and a strong emphasis was placed on not only the medicine, but the human factor relating to these situations. It was a great balance of “cool tac med” and the impact that this job has not only on the provider, but on our patients and bystanders.

As with all great conferences, the opportunity to network with an international cast of like-minded people who are interested in progressing tactical medicine was amazing. This group of people are all about collaborating and educating anyone and everyone about tactical medicine and pushing for the best evidence-based practice – a worthy cause. The College is hoping to have a footprint at this conference next year – dates for next year’s ATMAare 10-11 September 2020. The conference will be held at Pullman Hotel, King George Square, Brisbane.

Check out the team at ATMA- https://www.atma.net.au/.

13

Nicole Foster BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

Foster

14

Pullman Hotel, Brisbane, site of the 2020 Australian Tactical Medicine Conference

Trends in Traumatology

Jason Jarvis on the CRASH-3 study

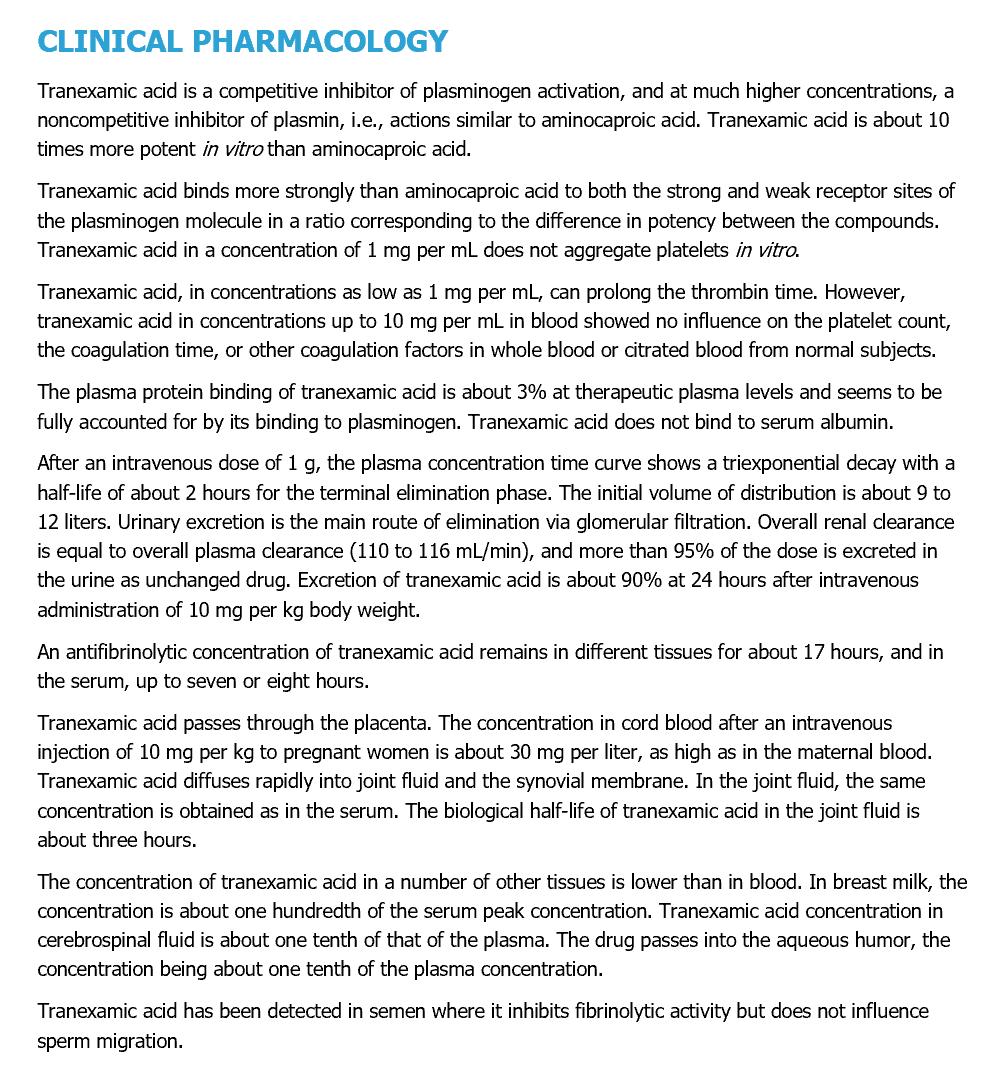

On October 14, 2019, The Lancet published the long-awaited CRASH-3 study on the effects of tranexamic acid on patients experiencing acute traumatic brain injury (TBI). This landmark study is formally titled: “Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3); a randomised, placebo-controlled trial.” The full text of the study: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS01406736(19)32233-0/fulltext

Asummary of the CRASH-3 results:

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

“Between July 20, 2012, and Jan 31, 2019, we randomly allocated 12 737 patients with TBI to receive tranexamic acid (6406 [50·3%] or placebo [6331 [49·7%], of whom 9202 (72·2%) patients were treated within 3 h of injury. Among patients treated within 3 h of injury, the risk of head injury-related death was 18·5% in the tranexamic acid group versus 19·8% in the placebo group (855 vs 892 events; risk ratio [RR] 0·94 [95% CI 0·86–1·02]). In the prespecified sensitivity analysis that excluded patients with a GCS score of 3 or bilateral unreactive pupils at baseline, the risk of head injury-related death was 12·5% in the tranexamic acid group versus 14·0% in the placebo group (485 vs 525 events; RR 0·89 [95% CI 0·80–1·00]). The risk of head injury-related death reduced with tranexamic acid in patients with mild-to-moderate head injury (RR 0·78 [95% CI 0·64–0·95]) but not in patients with severe head injury (0·99 [95% CI 0·91–1·07]; p value for heterogeneity 0·030). Early treatment was more effective than was later treatment in patients with mild and moderate head injury (p=0·005) but time to treatment had no obvious effect in patients with severe head injury (p=0·73). The risk of vascular occlusive events was similar in the tranexamic acid and placebo groups (RR 0·98 (0·74–1·28). The risk of seizures was also similar between groups (1·09 [95% CI 0·90–1·33]).”

Procedures

Interpretation

For further insights into the CRASH-3 study and its applicability to both field and hospital-based patient care, CoROMAcademic Board member Dr. Willem Stassen provides in-depth commentary on the BadEM podcast: https://badem.co.za/crash-3/

15

“Our results show that tranexamic acid is safe in patients with TBI and that treatment within 3 hours of injury reduces head injury-related death. Patients should be treated as soon as possible after injury.”

“Patients were randomly allocated to receive a loading dose of 1 g of tranexamic acid infused over 10 min, started immediately after randomisation, followed by an intravenous infusion of 1 g over 8 h, or matching placebo….”

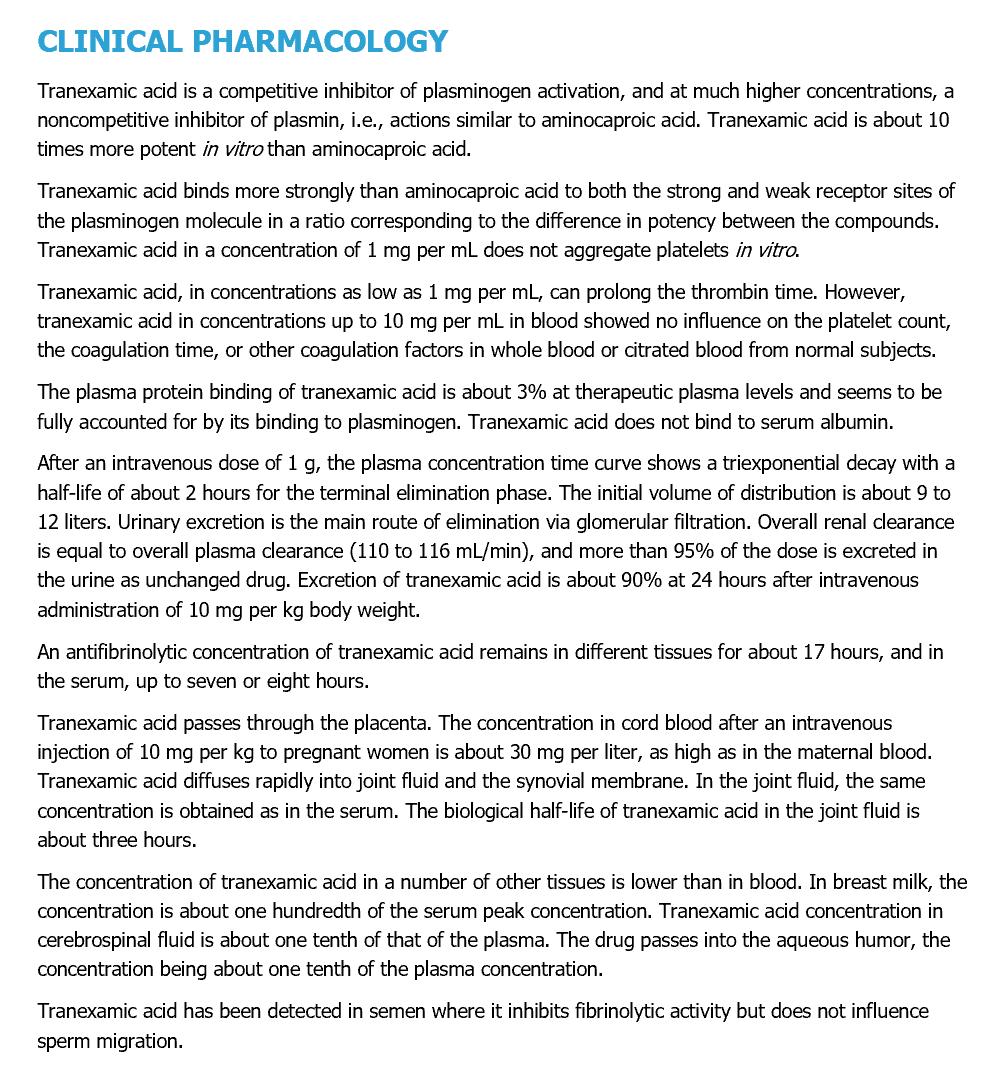

Selected product information for tranexamic acid(TXA)

16

Test Yourself

One of the scientists under your care at a research base inAntarctica comes to you complaining of heart palpitations.You recognize the anomaly in her ECG as a:

A. Mobitz II heart block

B. Premature atrial contraction

C. Premature junctional contraction

D. Premature ventricular contraction

Drug Calculation

Using the USAISR Rule of Ten, at how many drops per minute will you infuse Lactated Ringer’s for a 90kg patient with 30% TBSAburns using a 10gtt/mL giving set?

Clinical Case

On the first day of a climbing expedition on Baffin Island, one of the climbers sustains a midshaft femur fracture.After applying a traction splint and administering 400μg of transmucosal fentanyl, you perform a femoral nerve block using 20mL of 1% lidocaine. The patient weighs 75kg.An hour later you notice that the patient is exhibiting cyanosis of the face and hands (pictured), altered mental status, and an SpO2 of 88%. Which of the following medications should you give next?

A. Normal saline

B. Amyl nitrate

C. Epinephrine 1:1000

D. Methylene blue

Answers will appear in the Spring edition of The Compass.

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: Complete heart block (3rd-degree atrioventricular block)

Drug calculation: The Primaxin should be infused at 50 drops/minute

Clinical case: G6PD deficiency

17

ECG

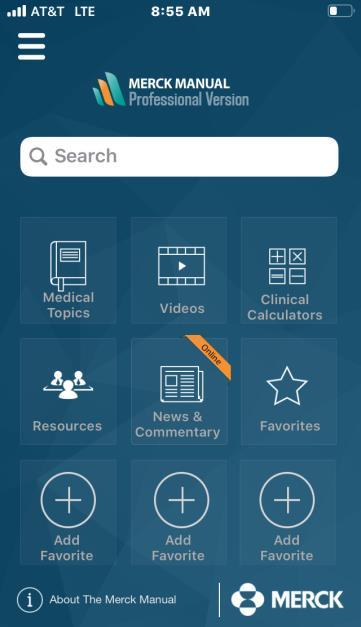

Resources

Aselection of medical references and gear

Medical References (Editor’s picks)

Gear Hyfin® Vent Compact Chest Seal Twin Pack available

at https://www.narescue.com/military-products

“The Hyfin® Vent Compact Chest Seal Twin Pack provides users with two vented chest seals in a compact packaging designed for the prevention, management and treatment of an open and/or tension pneumothorax potentially caused by a penetrating chest trauma. The cutting-edge design of these chest seals incorporate 3 vented channels designed to allow air to escape the chest cavity during exhalation but prevent airflow from entering the injury site during inhalation. Each Hyfin® Vent Compact Chest Seal is made with advanced hydrogel technology designed to provide a superior adhesion in adverse conditions or austere environments where the casualty may be covered in blood, sweat, body hair, or other environmental contaminants.

Constructed of a rugged, easy-to-open foil pouch, the perforated twin packaging allows users to open only one dressing at a time as needed. Its small packaging is approximately 25% smaller than that of the original Hyfin® Vent Chest Seal and is ideal for low profile kits as you do not have to fold it to get it to fit in your kit, go-bag, cargo pocket or body armor.”

Specs

Dimensions 12cm x 12cm

Weight 43.94g

18

Journal Watch

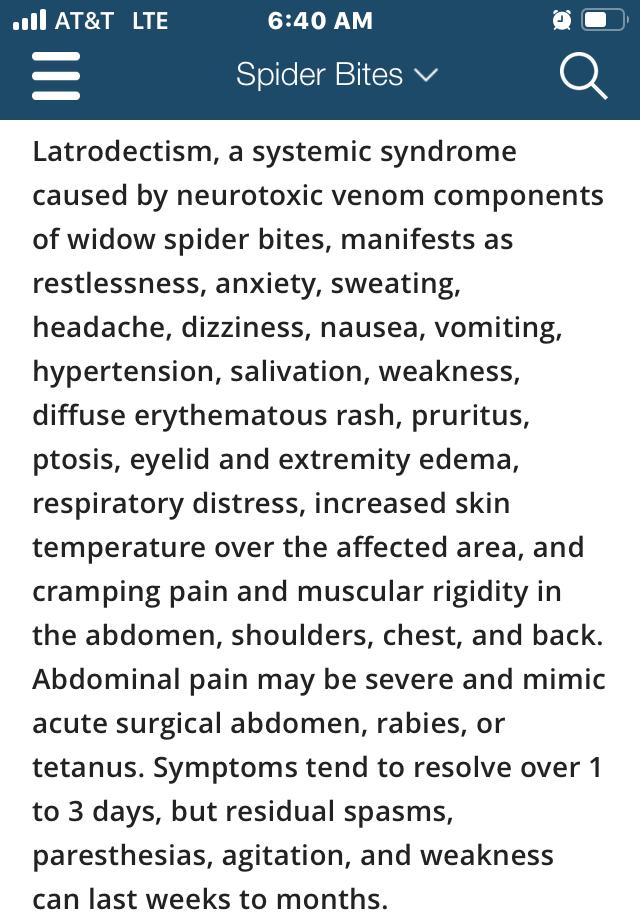

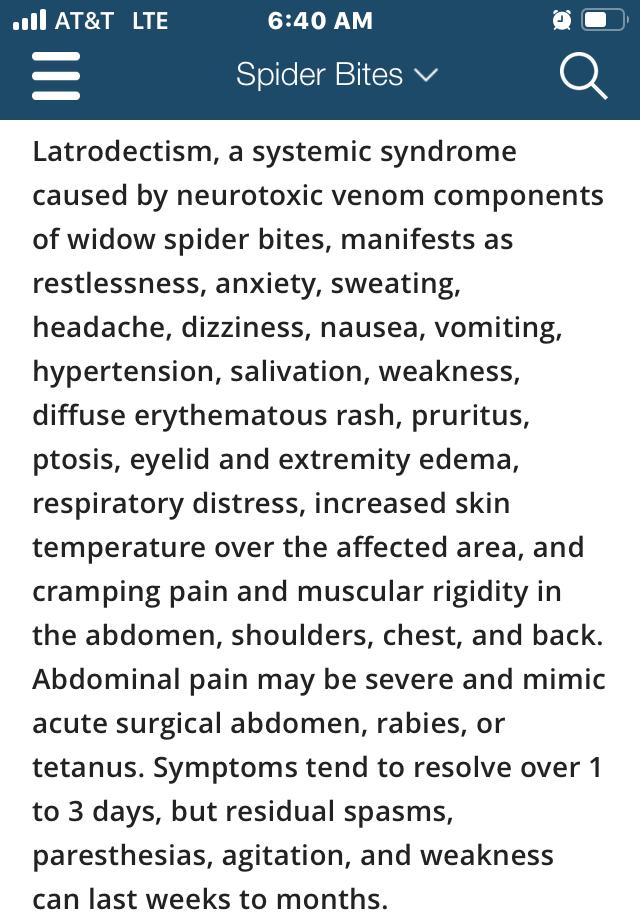

Pit latrines:Apotential risk factor for latrodectism in rural SouthAfrica?

The South African Medical Journal 2019; 109(11):848-849.

A Msiwa, S D Ntshalintshali

A Msiwa, S D Ntshalintshali

Abstract

Latrodectus spp. spider bites usually occur away from domestic sites, in the open fields or bushes. We report 3 cases of latrodectism that were identified to be associated with bites by these spiders in a rural domestic setting, specifically while the victim was using a pit latrine.

Air pollution: the emergence of a major global health risk factor

International Health

Volume 11, Issue 6, November 2019, Pages 417-421. Hanna Boogaard, Katherine Walker, Aaron J Cohen.

Abstract

Air pollution is now recognized by governments, international institutions and civil society as a major global public health risk factor. This is the result of the remarkable growth of scientific knowledge enabled by advances in epidemiology and exposure assessment. There is now a broad scientific consensus that exposure to air pollution increases mortality and morbidity from cardiovascular and respiratory disease and lung cancer and shortens life expectancy. Although air pollution has markedly declined in high-income countries, it was still responsible for some 4.9 million deaths in 2017, largely in low- and middleincome countries, where air pollution has increased over the past 25 years. As governments act to reduce air pollution there is a continuing need for research to strengthen the evidence on disease risk at very low and very high levels of air pollution, identify the air pollution sources most responsible for disease burden and assess the public health effectiveness of actions taken to improve air quality.

19

South Africa’s Latrodectus cinctus, a.k.a., the East Coast button spider

The Merck Manual entry on latrodectism

Smog in New Delhi, India

Journal Watch

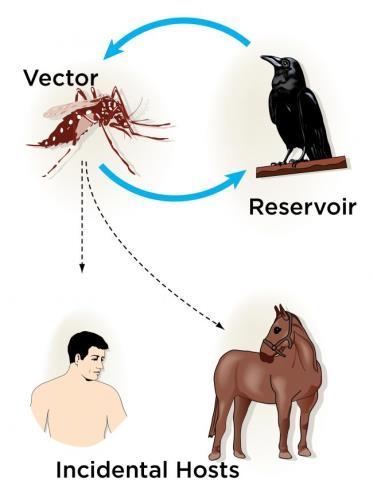

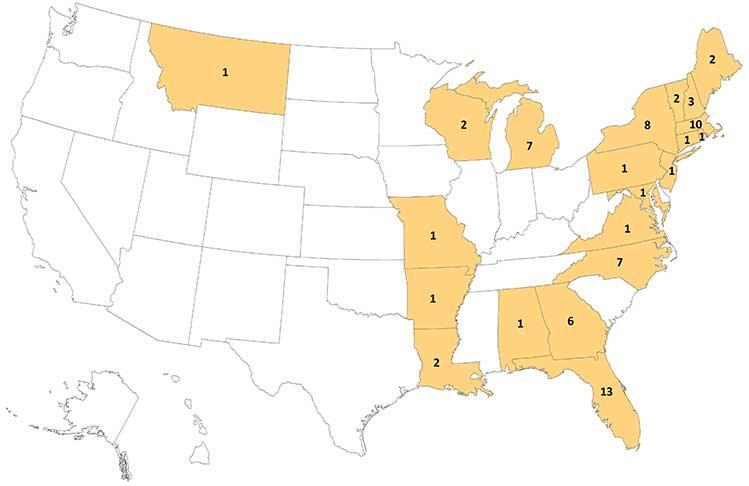

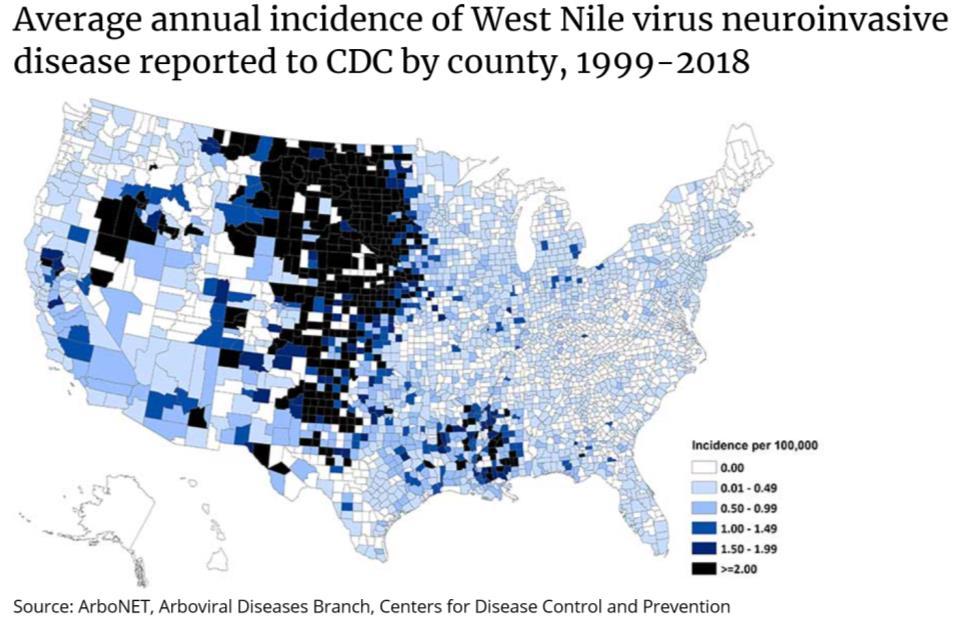

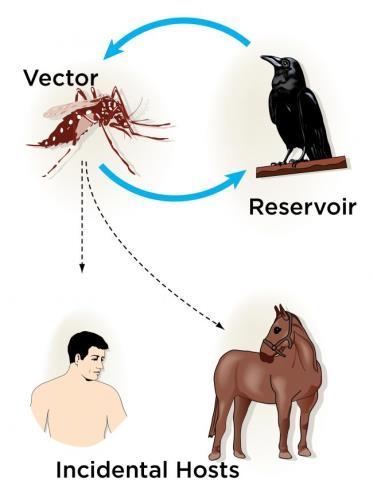

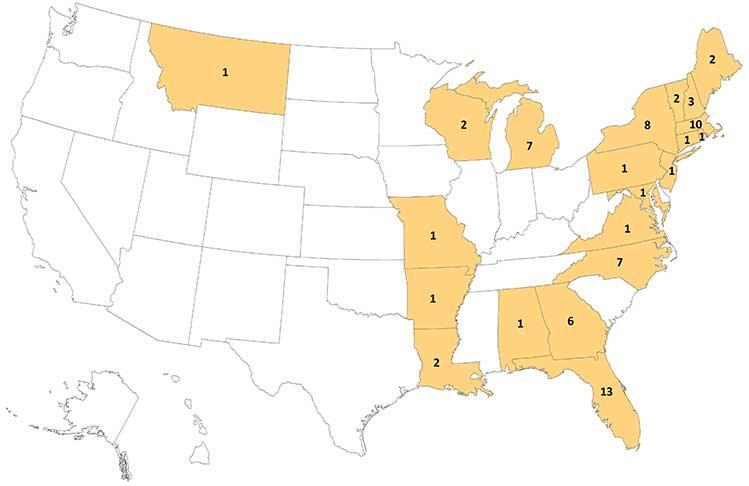

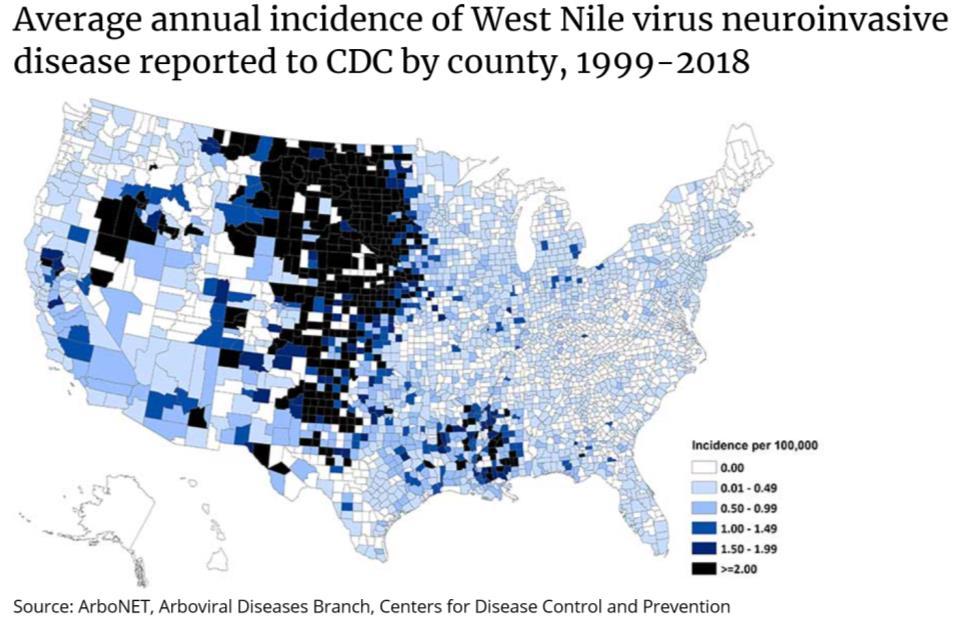

Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus –Another Emergent Arbovirus in the United States

New England Journal of Medicine

November 21, 2019.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1914328.

David M. Morens, MD; Gregory K. Folkers, MS, MPH; Anthony S. Fauci, MD.

Perspective

Humans have always lived in intimate association with arthropods that transmit pathogens between humans or from animals to humans. About 700,000 deaths due to vector-borne diseases occur globally each year, according to World Health Organization estimates. In the summer and fall of 2019, nine U.S. states have reported 36 cases (14 of them fatal) of one of the deadliest of these diseases: eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), an arthropod-borne viral (arboviral) disease transmitted by mosquitoes. In recent years, theAmericas have witnessed a steady stream of other emerging or reemerging arboviruses, such as dengue, West Nile, chikungunya, Zika, and Powassan, as well as increasing numbers of travel-related cases of various other arboviral infections. This year’s EEE outbreaks may thus be a harbinger of a new era of arboviral emergencies.

The Reliability of Noninvasive Blood Pressure Measurement Through Layers ofAutumn/Winter Clothing:AProspective Study

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 2019 Sep;30(3):227-235.

Doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2019.03.006.

Woloszyn P, Baumberg I, Baker D.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm that it is possible to perform reliable NIBP measurements over 2 and 3 layers of autumn/winter clothing. Measuring NIBP with a clothed arm does not show clinical or statistically significant differences in comparison with measurements performed on the bare arm.

20

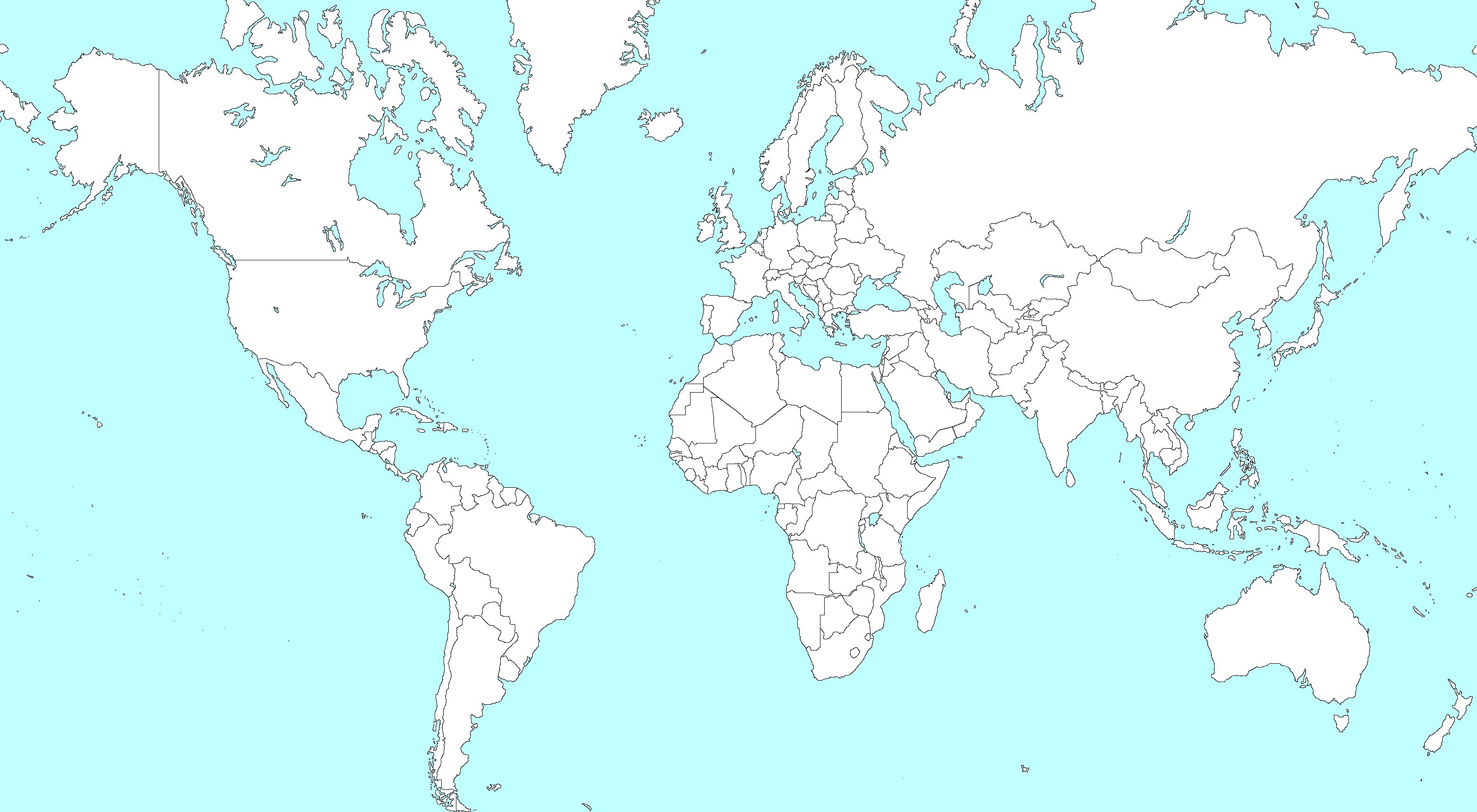

Case map of the 2019 U.S. eastern equine encephalitis outbreak

Transmission cycle of EEE virus

Book Review

West Nile Story:ANew Virus in the New World

By Dickson Despommier 2001

Apple Trees Productions, LLC

Review by Jason Jarvis

By Dickson Despommier 2001

Apple Trees Productions, LLC

Review by Jason Jarvis

West Nile Story is edutainment at its finest, a fast-paced and engaging tale that is part ecological saga, part medical detective story.

In West Nile Story, Columbia University public health and microbiology professor Dickson Despommier traces the 1999 New York City outbreak of West Nile Virus (WNV) back to the 1998 outbreak in Israel, and ultimately back to WNV’s patient zero in the West Nile district of Uganda in the year 1937.

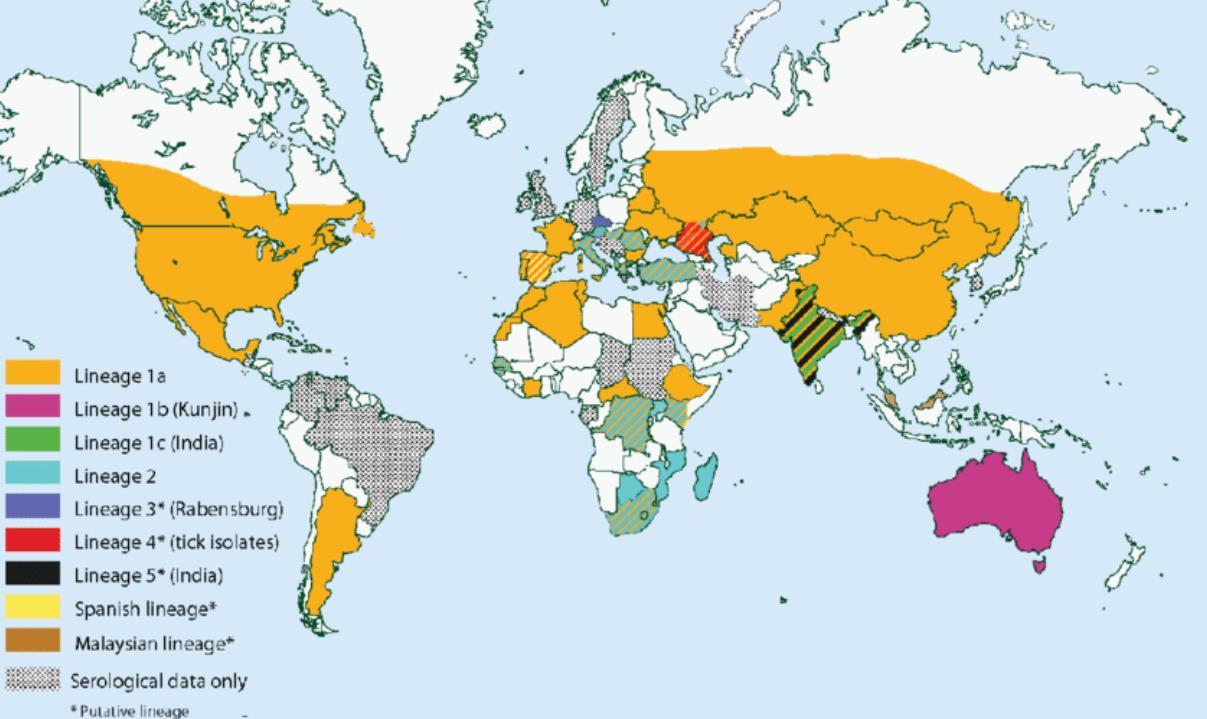

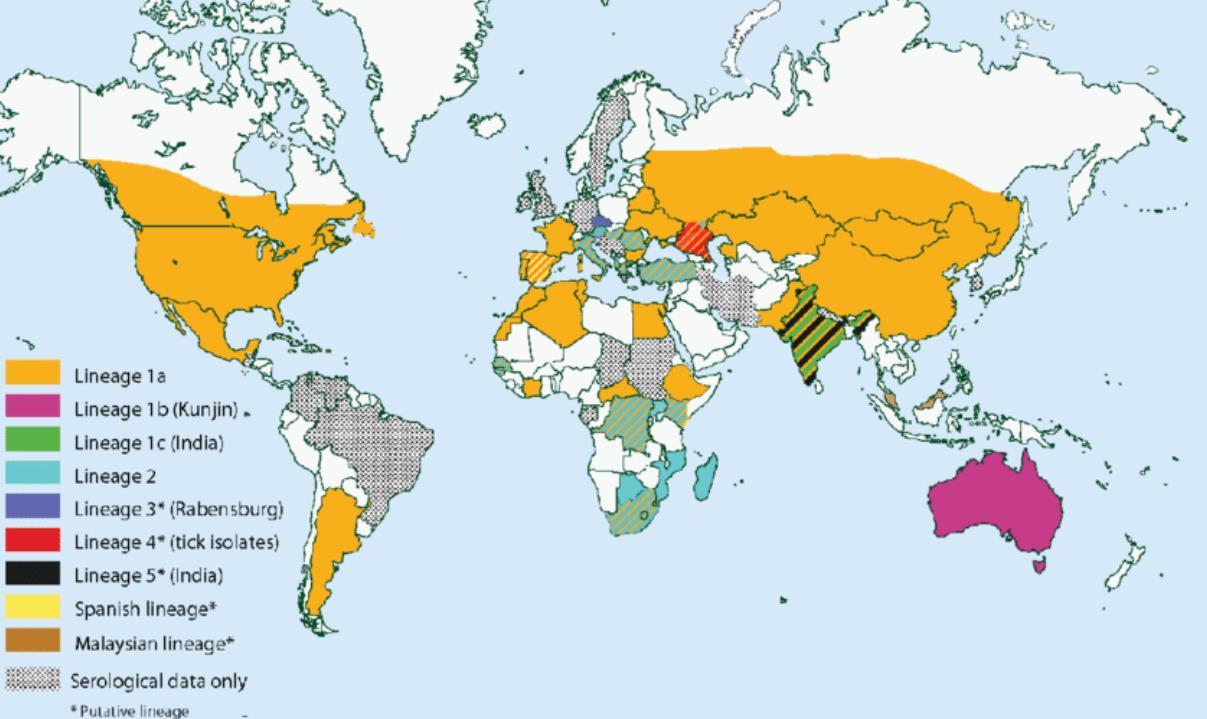

WNV is classified as both an arthropod-borne virus (arbovirus) and flavivirus, which places it into the same viral taxonomic grouping as yellow fever, dengue, St. Louis encephalitis, and Zika virus. In the New World, WNV is mainly transmitted via the bite of infected female Culex pipiens mosquitoes, though many other mosquito species – chiefly members of the Culex and Aedes genera – are capable of inoculating both people and animals with the virus.

Despommier goes on to explain the ecological and climatic conditions favorable for outbreaks of WNV and similar arboviruses. WNV originated as an infection of Old World birds, most of which exhibit little if any pathology. It is theorized that these birds, having been exposed to the virus for countless generations, have been selected by evolution to be largely resistant to the deleterious effects of the virus. New World birds –particularly crows – exposed to WNV do not fare so well, many of them dying upon exposure to the virus. Many of the mosquito species which prey upon birds have shown themselves to be competent vectors for WNV and have little qualms about turning to alternative sources of blood (i.e., humans) once these birds migrate away from drought conditions. In addition, many of these Culex and Aedes mosquitoes preferentially breed in polluted water, a resource found all too abundantly in most of the world’s urban areas. Humans infected with WNV, while more than capable of exhibiting pathology (myalgia, encephalitis, and death) do not typically develop sufficient levels of viremia capable of transmission to mosquito vectors; humans are therefore considered dead end hosts (unlike birds, which build up high levels of viremia and readily transmit the virus to

Dickson Despommier is Professor of Public Health and Microbiology at Columbia University in New York City. He has taught numerous courses to medical and graduate students. He has authored 13 review chapters in books and is the senior author on two textbooks dealing with parasitic infections. He often lectures to the lay public on such diverse subjects as the medical ecology of infectious diseases, stream ecology, and trout fishing. His interest in the West Nile Virus stems from a lifelong passion for learning about the ways in which infectious agents behave in the environment. His current research is on the development of a new hybrid science, Medical Ecology.

feeding mosquitoes; birds in this case are termed

West Nile Story is therefore a cautionary tale for our times: urban dwellers would do well to avoid mosquito bites during summertime drought conditions.

21

Electron micrograph of West Nile Virus other

amplifier hosts).

Major mosquito vectors of West Nile Virus within the U.S.

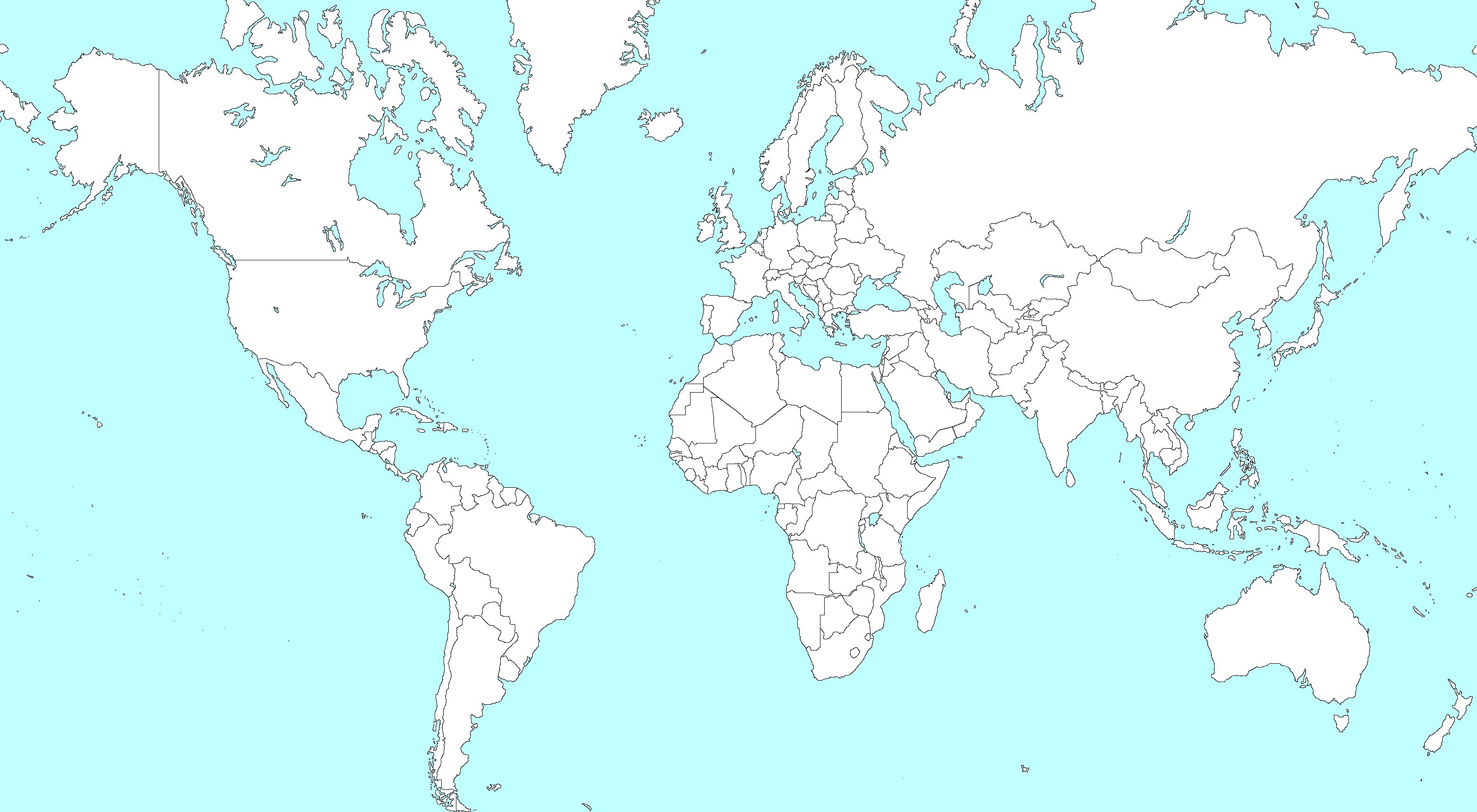

Global distribution ofWest Nile Virus

22

Culex pipiens

Culex restuans

Aedes triseriatus

Aedes japonicus

Aedes vexans

Aedes albopictus

Culex tarsalis

Join

CoROMatthe 2020SpecialOperationsMedicalAssociation

ScientificAssemblyandExhibition inRaleigh,NorthCarolina

CoROMwillberunninganexhibitor’sboothaswellas hostingtwoworkshops:

Detection andMitigationofMalariaintheAustereSetting

TacticalMedicineReview&IBSCExams

Remote &Austere Medicine Field Guide for Practitioners, 2nd edition

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

Snakes and arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS & diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory techniques

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

…and much more!

AVAILABLE

FEBRUARY 2020 at corom.org

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor