The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, transit, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary MedicalAdvisory Board (MAB) consisting of medical professionals from NorthAmerica, Europe,Africa and the Middle East. The College is gaining registration with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta to become a degree granting educational facility.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and difficult environments.

The College had a busyAutumn semester, with our faculty teaching in Malta, France and Germany. The Malta programs included the Remote Paramedic course, plus the TTEMS and RAMS courses, with 26 and 14 delegates attending the latter two courses, respectively. Most of the attendees were collecting Fellowship credits in order to earn their Fellow of theAcademy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM) from the Wilderness Medical Society.

In France we offered the ITLS course at our new affiliate, Remote Medicine France. In Germany, our Faculty were invited back to teach on the Tactical Combat Casualty Care module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course. Our Faculty have taught on every NSOCM course and will be returning later this winter to teach Tropical Medicine and Prolonged Field Care.

2019 is shaping up to be another exciting year. In January we are launching a Clinical TTEMS course on the Thai-Burma border. Besides poolside medical lessons, our delegates will have the opportunity to assist in the healthcare of Burmese refugees.

In February we will serve as adjunct faculty for the University of Limerick in Ireland. We will be teaching our Critical Care Paramedic course and are honoured to have this course accredited by UL.

CoROM is returning to the annual Special Operations MedicalAssociation Scientific Assembly in May. Besides our exhibitor’s table, we are offering two pre-conference workshops: Malaria Microscopy, and the Tactical Medicine Review which will include the IBSC board certification exam.

The College excels by the work and dedication of our Faculty and the motivation from our delegates. In addition, we benefit from all the medical professionals who have become Members of the College.

I would like to send my personal appreciation to our faculty, our delegates and the members of the College. It is their passion that lights the way toward our goal of providing superb evidence-based medicine in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

I am honoured to serve as a member of theAcademic Board of CoROM.

Dr. Csaba Dioszeghy PhD FRCEM FERC FFICM

My first encounter with prehospital emergency care - and the time when I fell in love with it - was in 1986 as a part-time EMT during my junior medical school years in Budapest, Hungary. After passing the paramedic exams in 1990 I carried on working for theAmbulance service as a part-time paramedic until I received my MD and then further on as a prehospital doctor both on ambulance and helicopter up until 2005. I completed my specialist training inAnaesthesia and Intensive Care in 1996 and carried on for additional specialist training in cardiology (2001). I was most interested in emergency critical care, resuscitation and acute cardiac emergencies. In 2004 I passed the specialty board exam in Emergency Medicine and in 2009 the specialty exam for prehospital emergency medicine. In 2010 - after 10 years of research activity - I completed my PhD work in the field of “Critical Care in Cardiology.”

Between 2000 - 2003 I was an associate professor of anaesthesia and intensive care at the Semmelweis University and the head ofAnaesthesia and Intensive Care teaching program for the English faculty; in addition, I introduced the Emergency Medicine undergraduate training for medical students there in 2003. Between 2003-2005 - besides being a senior guest lecturer for Semmelweis University - I was the head of theAnaesthesia - Intensive Care and Emergency Departments for Jahn Ferenc Teaching Hospital in Budapest. Since 2005 I worked as a consultant in emergency medicine and intensive care in the NHS (UK); first in Yeovil, then in North London and since 2012 in Surrey. Currently, I am the deputy clinical lead of the Emergency Department in East Surrey Hospital.

I was extensively involved in the work of the European Resuscitation Council from 2000-2012, including working on the 2010 ILCOR consensus statement and guidelines, and playing a key part in the dissemination of the different life support courses in Europe and beyond as international course director.

My involvement in CoROM is mainly focused on Critical Care training which I enormously enjoy. Critical care is getting so much high-tech nowadays that providers are getting more and more dependent on technology and tend to ignore the rationale behind the numbers and actions. While a state-of-the-art facility provides a safe environment for most patients, critical care should be more a way of thinking and a way of a clinical approach based on a thorough understanding of physiology, pathophysiology and clinical evaluation and prioritisation rather than utilisation of guidelines based on numbers given by high-tech monitoring devices. The greatest challenge in critical care is to be able to take it anywhere and apply the critical care approach and mindset to the sickest patients even in remote and resource-poor areas. I believe this is possible by demystifying the core principles of critical care and explaining them in a way that is easy to understand. Making it simple and clinically relevant are my main objectives while teaching these courses. In critical care, making the right decision based on the understanding of the ongoing physiological processes is the key and far more important than to establish a nice-sounding diagnosis. Critical care is not rocket science but does hinge upon good decision making.

The challenge CoROM is facing in 2019 regarding critical care training is huge: we are setting up a whole new way of teaching critical care by creating better and more structured online material and running a two-week modular face-to-face course. The first week should demystify the core concepts of critical care, introducing the mindset which is needed to apply these principles to clinical practice. The second week focuses on clinical scenarios with hands-on practice and simulations. The CoROM faculty are enthusiastic and dedicated, and we hope that our trainees will enjoy the experience and will successfully complete these courses. But what is far more important is that students will be able to take these concepts and skills with them and provide high-level critical care to their sickest patients in the remote and offshore environment whenever needed.

Dr. Csaba Dioszeghy on the past, present and future of Critical Care training

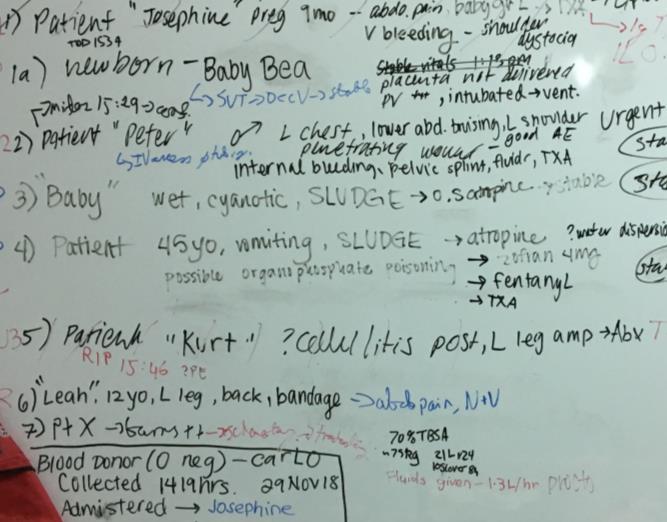

under head torches during a field training exercise

Improvised suturing using a young Dorylus driver ant in Tanzania

Patient charting during a field training exercise

CC-P 4-8 Feb

NSOCM

TTEMS 18-22 Feb

Prolonged Field Care 25 Feb-8 Mar

CRP 18 March-6 April

TTEMS 8-12 April

RAMS 15-19 April

Foundations in Crit Care 15-19 April

CC-P 22-27 April

TTEMS 27-31 May

RAMS 3-7 June

Foundations in Crit Care 7-11 Oct

CC-P 14-19 Oct

Remote EMT 18-23 Nov

TTEMS 25-29 Nov

Advanced TTEMS 2-6 Dec

RAMS 9-13 Dec

NORTH CAROLINA

SOMSA Conference 6-10 May

Tropical Medicine workshop

Tactical Medicine Review with exam

TANZANIA

CRP 15 July-3 Aug

TTEMS 5-9 Aug

THAI-BURMABORDER

Clinical TTEMS course

14-26 January

CC-P: International Critical Care Paramedic (with optional pre-study week)

CRP: CoROM Remote Paramedic*

NSOCM: NATO Special Operations Combat Medic course

RAMS: Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS: Remote Medical Life Support

SOMSA: Special Operations Medicine Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS: Tropical, Travel and Expeditionary Medical Skills

* The CRP course also includes 20-30 weeks of online training, plus a 400-hour clinical rotation.

Advanced Certificate and Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Clinical Placements

University teaching hospital, Moshi, Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Level 3

Health and Safety for the Workplace

Level 3 Food Safety for the Workplace

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org. Please address newsletter correspondence to editor@corom.org.

Johannes Boshoff is an ex-fireman, close protection operative and CoROM remote paramedic student. He currently works in Somalia for Bancroft Global Development as an operational medic/mentor.

Johannes Boshoff CRP student

Johannes Boshoff CRP student

I attended the CoROM Remote Paramedic Course in Tanzania in September 2018. I thoroughly enjoyed the well-presented course, and I was really impressed by the amount of work that went into it. I also learned so many new skills and made new friends whilst being there. I am still busy completing my 400 hours of practical and am very fortunate to have an employer that fully understands the challenges to complete that.

As an operational medic I get to deploy with various organizations and operational groups in Somalia. The bulk of my work is within the base where I am part of a team of medics that staff the 24-hour clinic that we have on site. We see medical and trauma patients, dispense medications, and may refer patiens for blood labs, x-rays, or other diagnostic tests. We can admit patients or evacuate them to either the nearby Level 2 hospital or Nairobi for further treatment.

As an operational medic I deploy to the field for variable periods of time, from a one-day operation, to 6 weeks at a time - as long as the job requires to complete. We mostly travel by road, driving vehicles that are armored to withstand IED blasts. While outside the compound, I wear PPE and carry my own weapon. We are supported directly by our medics that work on the helicopters for the UN, and by our medics that work on the fixed wing service that we provide. Typically, we stabilize and treat the patients in the field that were injured during operations, or we see them a short while after the injuries occurred elsewhere and are then brought to us for treatment wherever we are deployed at the time. Each operation that leaves the base gets an operational medic and no two missions are the same, which creates its own set of challenges.

Occasionally we get asked to fly with the aeromedical team and medics to gain flight hours and experience. With our vast team of physicians and medics from various countries and backgrounds, we also assist in the operating theatre and work part time in the emergency department at the Level 2 Amisom Hospital. I learn something new daily and am very glad that I took the next step towards better patient care with the CoROM CRP course. I look forward to returning to CoROM for the Critical Care Paramedic course,

Mátyás Solténszky is an IBSC board-certified critical care paramedic and flight paramedic. When not teaching for CoROM, he works in Budapest at Hungarian Air Ambulance Nonprofit Ltd.

What aspect of CoROM motivated you to join the College?

In the spring of 2016 I had the opportunity to attend the Critical Care Paramedic and Flight Paramedic courses in Malta. After the classroom week, Aebhric O’Kelly and I had a short conversation about the training, the future of the training centre, his plans, and at the end he invited me to join the “black-shirted guys.” Those amazing plans and the power I’ve seen in that gentleman to make them led me to join CoROM. That was one of my best decisions as now I see how amazing the College has become.

What is your favorite teaching topic at CoROM?

Hard question…maybe most of the Critical Care subjects. In Hungary I spent years teaching critical care airway management, prehospital RSI, trauma and critical care, so these topics are the closest to me. I also really love teaching cardiac topics – ECGs andACLS - and prehospital ventilator therapy. It’s difficult to make a choice which topic is my favorite, but if I had to, I’d choose the prehospital airway and RSI.

Where would you like to see CoROM go in the next five years?

The development that CoROM has gone through in the last few years is amazing, and I hope that the College will be unstoppable and continue this process! It would be nice if CoROM’s CCP course would become more widely accepted in Europe, but I also know that due to the very different systems in the EU nations, it is hard or close to impossible to design a course that covers each unique medical system.

Describe a medical case that has had a lasting impact on you.

It was at the beginning of my CCP career, with the feeling of a superhero, that I can save everyone’s life. Aground ALS unit received a call to a middle-aged man complaining of severe chest pain. Upon arrival we found him on the floor of his house, very agitated and confused. I tried to make my initial assessment, but he was too agitated for me to finish it. I wanted to sedate him, but his blood pressure was too low and I froze…this is not what I learned in school. This was a difficult scenario to handle. I fixated only on the chest pain and agitation, but I was unable to treat them, and I needed to collect more pieces of the puzzle. What was causing this this condition? When he became unresponsive, this was the slap that pulled me back again. From this point it was just like another scenario at medic school. But it was too late…his breathing stopped, we performed ALS for an hour…but we lost him…

The lesson I learned then is a very important one. When you feel that you start to lose control on the scene, when you can’t put the pieces to one picture: step back, calm yourself down, and summarize all the information you have. That will clear the picture. And finally: we can’t save everyone’s life but must always do our best!

Mátyás Solténszky CCP-C FP-C CoROM FacultyWhat are some references you would recommend for those interested in HEMS work?

To keep up-to-date, I listen to a lot of podcasts, like the Sydney HEMS podcast (https://sydneyhems.com/category/podcast), the SMACC (https://www.smack.net.au/blog), or the EMCrit Project (http://emcrit.org).

If one prefers books over digital content, my favorites are the Cases in Pre-hospital and Retrieval Medicine (by Dan Ellis and Matthew Hooper), which guides the reader through many HEMS cases. As a critical care provider I must maintain mastery in ECGs, so the other book I enjoy is 150 ECG Problems (by John R. Hampton). For all other topics UpToDate.com is my bible!

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) is a Zonal referral and teaching hospital situated in the northern region of Tanzania. It is situated at the foothills of the highest snow-capped mountain in Africa - Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Francis Sakita MD, MMED Emergency Physician Head of ED-KCMC CoROM Faculty

Francis Sakita MD, MMED Emergency Physician Head of ED-KCMC CoROM Faculty

The emergency medicine department (EMD) is just one among the many departments of KCMC which receive up to 60 critically-ill patients per day. Initially, there was only one room for resuscitation and three cubicles for treatment of walk-in patients. Expansion was done in 2016 and now there are three sections in the department: the adult medical, pediatrics, and trauma resuscitation bays.

CoROM and KCMC-EMD signed a memorandum of understanding in January 2018 and this has enabled CoROM students from different parts of the world to conduct their clinical shifts of learning and gaining hands-on skills.

We see a broad number of cases from non-communicable disease like hypertension and diabetes, to infectious diseases like malaria. Moreover, vehicular trauma cases are on the rise, specifically head injury and long bone fractures. Situated so closely to Mt. Kilimanjaro, we do see occasional cases of high-altitude illnesses.

Dr. Andrew Stephens, Dr. Francis Sakita, and Aebhric O’Kelly at the KCMC ED

Dr. Andrew Stephens, Dr. Francis Sakita, and Aebhric O’Kelly at the KCMC ED

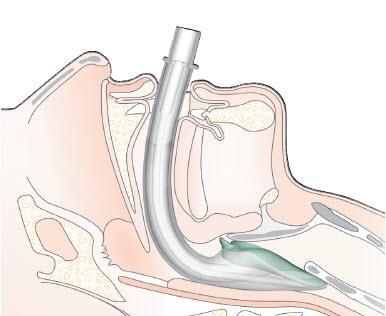

The pantheon of extraglottic airway devices – like many other staples in the emergency medicine practitioner’s arsenal – continues to evolve.

Two decades ago, the Combitube was the primary blind insertion airway device backup to a failed intubation attempt in the field. Then along came the King tube (with its cumbersome 100mL syringe), which enjoyed a years-long heyday in the dusty bottoms of military medical bags throughout Iraq and Afghanistan.

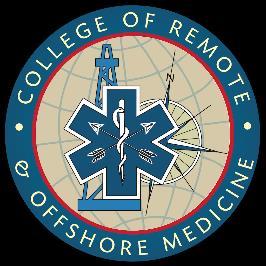

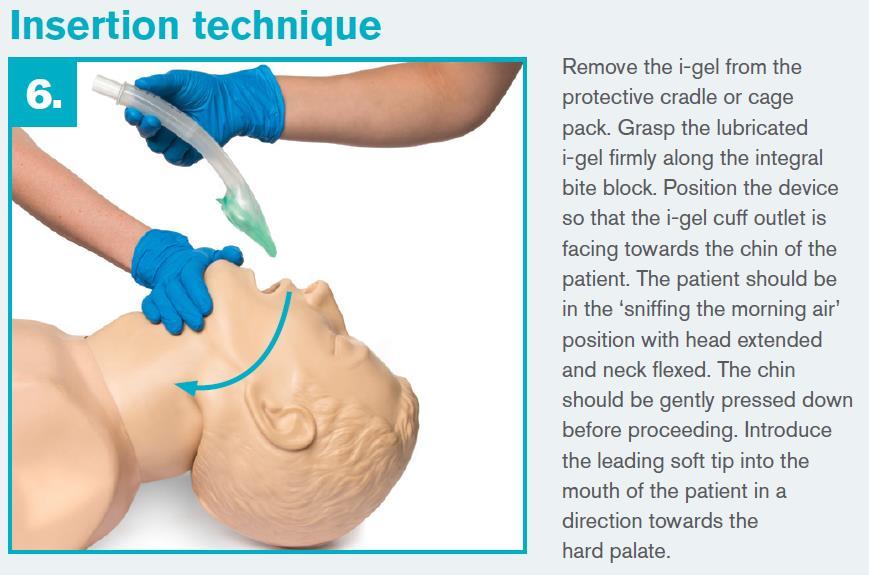

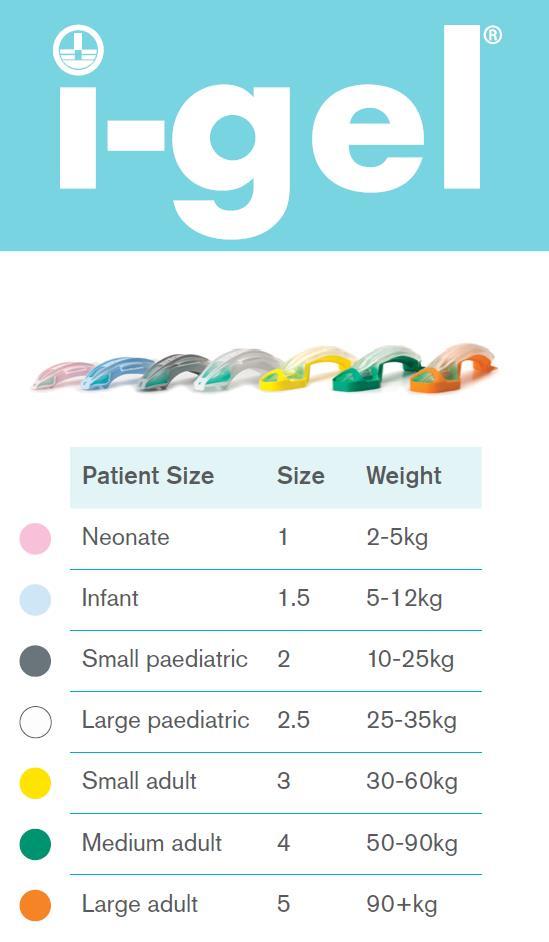

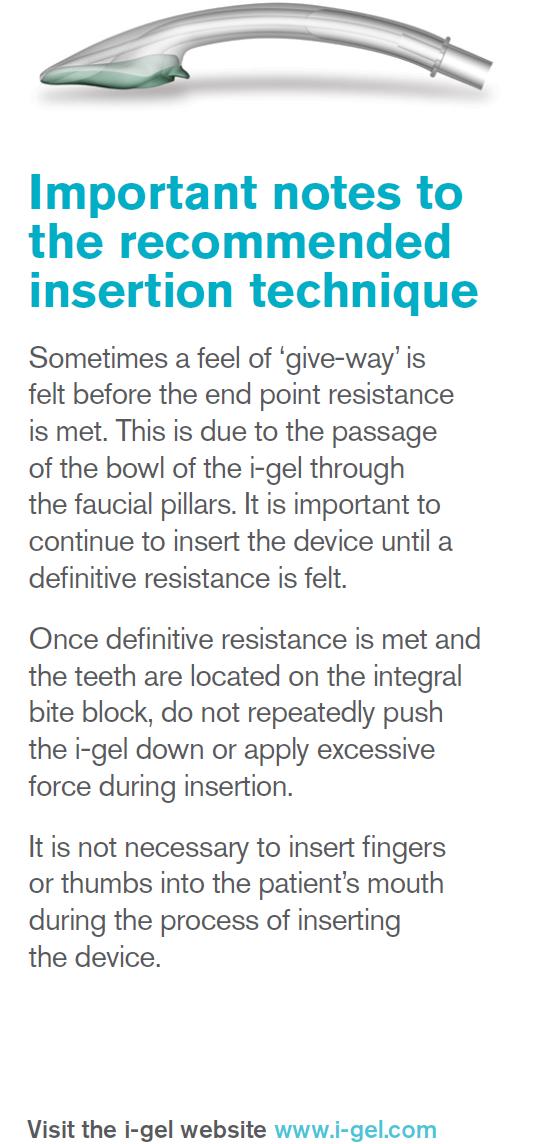

In 2018, a new extraglottic airway has risen to primacy: the i-gel®

The U.S. military’s Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) committee endorsed the i-gel in itsAugust 1 update as “the preferred extraglottic airway” for field medics. The i-gel resembles a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) in shape, but whereas the cuff of an LMA is inflatable, the analogous “cuff” of the i-gel is gelfilled.

CoROM takes pride in its robust airway management training curriculum and has trained its students in the use of the i-gel (as well as the LMA and King tube) since the inception of the College in 2014.

Intersurgical®, the manufacturer of the i-gel, describes its product in the following passage: “The i-gel® is the innovative second generation supraglottic airway device from Intersurgical The first major development since the laryngeal mask airway, i-gel has changed the face of airway management and is now widely used in anaesthesia and resuscitation across the globe.

Made from a medical grade thermoplastic elastomer, i-gel has been designed to create a non-inflatable, anatomical seal of the pharyngeal, laryngeal and perilaryngeal structures whilst avoiding compression trauma.

Launched in 2007 after years of extensive research and development, i-gel now has an established reputation in anaesthesia with three adult and four paediatric sizes in the range, ideal for use with patient weights between 2-90+kg. In 2012, the indications for use were expanded to include use as a conduit for intubation (with fibreoptic guidance).”

Araft of research on the i-gel is available here: https://igelevidence.intersurgical.com/

The following is the pertinent excerpt from the August 1 2018 TCCC guidelines: “The i-gel is the preferred extraglottic airway because its gel-filled cuff makes it simpler to use and avoids the need for cuff inflation and monitoring. If an extraglottic airway with an air-filled cuff is used, the cuff pressure must be monitored to avoid overpressurization, especially during TACEVAC on an aircraft with the accompanying pressure changes.” https://www.naemt.org/docs/ default- source/education-documents/tccc/tcccmp/guidelines/tccc-guidelines-for-medical-personnel-180801.pdf?sfvrsn=13fc892_2

Afrequent question that we are asked in class is what is the best way to learn? Unfortunately, there is no simple answer to this question. Students’learning styles will vary just as much as tutors’teaching styles, and as such it can take some time to learn what works for you.

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Education Manager

From an education perspective we have seen wholesale changes over the last decade or so in what is available to students. Podcasts (Resus room, EmCrit, SMACC, etc.) and YouTube have changed the availability of information and the speed at which it can be accessed. While these are invaluable to the student they can also lead to "rabbit hole" learning. By this we mean that you delve into the topic in far more detail than is required at your current level. It is admirable to understand a topic in depth, but not at the expense of the many other topics that Paramedics are required to know.

So this month's advice is quite simple. If you don't know what you are supposed to study, go ask your tutor or mentor. Like you, they are also students (education never stops in this profession), and they will be able to guide you as to what is expected of you at your current level.

At a remote clinic in the Amazonian lowlands of Bolivia, your patient is suffering from an acute onset of altered mental status (GCS 3) and presents with the following ECG:

Lead II

As you continue to gather more data, you most strongly suspect:

A. Increased intracranial pressure secondary to head trauma

B. Neurocysticercosis

C. Cerebral malaria

D. Uremic encephalopathy

On a backcountry hiking expedition in the Tombstone Towers mountains of theYukon, you are preparing to infuse ketamine into a 60kg patient with 30% TBSAburns for pain relief.Your protocols call for a dose of 0.5mg/minute.Your junior medic hands you 200mg of ketamine mixed into a partially-full bag of normal saline (total volume is 360mL). Using a 20 drop/mL giving set, at what rate will you infuse this solution?

While manning an offshore oil rig clinic in the North Sea, one of the workers returns ill from shore leave in Helsinki, where he stayed at a hostel for two weeks. During his leave he was frequently bitten on the ankles and legs by “bugs” during the night. He never managed to catch any of these bugs, but you find one on the patient’s skin and inspect it under x50 magnification. You see a light brown arthropod that is roughly 3mm in length (see picture). In addition, the patient is complaining of abrupt onset of fever, headache, chills, loss of appetite, and muscle aches that started two days ago. Further physical exam reveals a rash on the trunk, as shown in the accompanying picture. Identify the arthropod and the most likely vector-borne disease this patient has based on the clinical picture.

Answers will appear in the Spring edition of The Compass.

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG : C. Sinus tachycardia with one premature atrial contraction

Drug calculation: Epinephrine should be infused at 168 drops per minute

Clinical case: Diaphragmatic rupture with protrusion of stomach into thorax

Medical References (Mátyás Solténszky’s picks)

Gear Mystery Ranch RapidAccess Trauma System pack available at mysteryranch.com

Annals of Emergency Medicine

January 2019 Volume 73, Issue 1, pages 1-7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.05.014

Romolo J. Gaspari, MD, PhD; Alexandra Sanseverino, MD; Timothy Gleeson, MD

Romolo J. Gaspari, MD, PhD; Alexandra Sanseverino, MD; Timothy Gleeson, MD

Results

Atotal of 125 patients were enrolled, 63 randomized to the point-of-care ultrasonography group and 62 to physical examination alone. After loss to follow-up and misallocation, 54 patients in the ultrasonography group and 53 in the physical examination alone group were analyzed. The overall failure rate for all patients enrolled in the study was 10.3%. Patients who were evaluated with ultrasonography were less likely to fail therapy and have repeated incision and drainage, with a difference between groups of 13.3% (95% confidence interval 0.0% to 19.4%). Abscess locations were predominantly torso (21%), buttocks (21%), lower extremity (18%), and axilla or groin (16%). There was no difference in baseline characteristics between groups relative to abscess size, duration of symptoms before presentation, percentage with cellulitis, and treatment with antibiotics.

Conclusion

Patients with soft tissue abscesses who were undergoing incision and drainage with point-of-care ultrasonography demonstrated less clinical failure compared with those treated without point-of-care ultrasonography.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine.

Fall, 2018, Vol 18, Edition 3.

https://www.jsomonline.org/TOC/1803JSOMTOC.php

Jonathan Auten, MD, et alBackground: Intraosseous (IO) access is used by military first responders administering fluids, blood, and medications. Current IO transfusion strategies include gravity, pressure bags,rapid transfusion devices, and manual push-pull through a three-way stopcock. In a swine model of hemorrhagic shock, we compared flow rates among four different IO blood transfusion strategies.

Methods: Nine Yorkshire swine were placed under general anesthesia. We removed 20 to 25mL/kg of each animal’s estimated blood volume using flow of gravity. IO access was obtained in the proximal humerus. We then autologously infused 10 to 15mL/kg of the animal’s estimated blood volume through one of four randomly assigned treatment arms.

Results: The average weight of the swine was 77.3kg(interquartile range, 72.7kg–88.8kg). Infusion rates were as follows: gravity, 5mL/min; Belmont rapid infuser, 31mL/min; single-site pressure bag, 78mL/min; double-site pressure bag, 103mL/min; and push-pull technique, 109mL/min. No pulmonary arterial fat emboli were noted.

Conclusion: The optimal IO transfusion strategy for injured Servicemembers appears to be single-site transfusion with a 10mL to 20mL flush of normal saline, followed immediately by transfusion under a pressure bag. Further study, powered to detect differences in flow rate and clinical complications is required.

Eurosurveilance

Volume 23, Issue 41, 11/Oct/2018.

https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.41.1800527

Lorenzo Zammarchi, et alIn August 2018, a Moroccan man living in Tuscany developed Plasmodium falciparum malaria. The patient declared having not recently visited any endemic country, leading to diagnostic delay and severe malaria. As susceptibility to P. falciparum of Anopheles species in Tuscany is very low, and other risk factors for acquiring malaria could not be completely excluded, the case remains cryptic, similar to other P. falciparum malaria cases previously reported in African individuals living in Apulia in 2017.

*Editor’s note: cryptic malaria is defined as a case that occurs in isolation and is not associated with secondary cases or imported cases

Journal of Emergency Medical Services.

Oct 24, 2018.

https://www.jems.com/articles/2018/10/ditch-the-machine-to-improve-accuracy-in-blood-pressuremeasurement-and-diagnostics.html

Mark Rock, NRPFor the patient in this case, the decision to forego the convenience of a machine in favor of the skills of a knowledgeable paramedic was lifesaving. Much like the comparison often drawn between the oldfashioned barbell and more sophisticated exercise machines, newer, more complex, and more expensive might make a process more comfortable, but doesn’t always equate to superior results.

As we surrender more and more of our hands-on skills to the ease of automated technology, we risk more than the loss of the aptitudes that form the foundation of sound patient assessment we place our patients in jeopardy of misdiagnoses and inadequate treatment. Proper use of the aneroid sphygmomanometer is but one of many practices that’s important for EMS professionals to maintain if we are to claim that we are anything other than accomplices to placing our patients’lives at the mercy of machines.

By Sonia Shah Picador, 2011

Review by Jason Jarvis

By Sonia Shah Picador, 2011

Review by Jason Jarvis

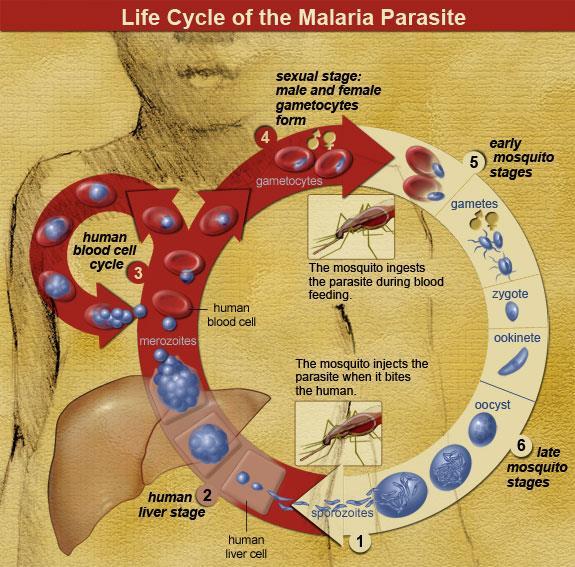

For those interested in public health, infectious diseases, or tropical medicine, The Fever is an essential and enthralling read on the history of malaria, the disease Oxford’s Handbook of Tropical Medicine calls “the most important parasitic disease of man.”

Author Sonia Shah’s investigative journalist chops shine as she takes the reader on a fascinating journey into the darkest recesses of the convoluted history of malaria – a tale that is equal parts human suffering, human ingenuity, human folly, and grim evolutionary tenacity. Africa – the probable birthplace of malaria – has been alternatively cursed or blessed by malaria in unexpected ways, depending upon the historical epoch in question. While sub-Saharan Africa has suffered the loss of countless millions due to malaria over the millennia, its relatively immune natives enjoyed a long period of invulnerability to nonimmune white settlers, that is, until the advent of the drug quinine. On the other hand,African slaves were prized over American natives for their ability to withstand the ravages of malaria in the New World. Thus an evolutionary and environmental advantage was turned against Africans, subjecting them to centuries of slavery in theAmericas.

Sonia Shah is an investigative journalist and the critically acclaimed author of The Body Hunters: Testing New Drugs on The World’s Poorest Patients.

Tropical medicine disciples with a penchant for history like yours truly can revel in passages such as these: “The physician Hippocrates described it as a disease common around swamps, while the poet Homer referred to malaria when he decried Sirius as an ‘evil star’that was ‘the harbinger of fevers.’The ancient Chinese called malaria ‘the mother of fevers,’while in India thirty-five hundred years ago it became known as ‘the king of diseases,’ personified by the fever demon Takman. The Vedic sages accurately described malaria’s signature chills and fever. ‘To the cold Takman,’they wrote, ‘to the shaking one, and to the deliriously hot, the glowing one, I render homage. To him that returns on the morrow, to him that returns for two successive days, to the Takman that returns on the third day, shall homage be.’”

Perhaps the most insightful part of the book is the chapter that deals with the reality of malaria control measures by those most affected by malaria.

Shah writes, “For the people who live with Plasmodium, the risk of malaria isn’t just numbingly familiar. In their lived experience they know that the overwhelming majority of the parasite’s incursions are trivial. Most of the time, carrying the parasite means next to nothing: no fever, no chills, no readily discernible symptoms, especially against a gray backdrop of other, more pressing ailments. It may not even be noticeable. Only seldom does one fall ill. Even then, when illness does occur, ninety-nine out of a hundred times, the fever and chills come and go…”

“Most of the ways we’ve devised to destroy malaria rely upon the committed participation of malaria’s victims. It is they who must drain the standing water, swat the mosquitoes, wear the repellent, sleep under the bed nets, go to the clinics, and take the drugs…”

“We want to think ofAfricans as battling an enemy, malaria, so that we can help them fight this enemy. We come

like Livingstone, with his moral righteousness – bearing the best our society has to offer: our riches and our technology. But the fight outsiders would like to wage against malaria isn’t always the same one fought by those who live with the disease.”

CoROMwillberunninganexhibitor’sboothaswellashosting twoworkshops:

TacticalMedicineReviewwithIBSCTacticalParamedicexam

MalariaMicroscopy