Summer 2022

Theofficialnewsletterofthe CollegeofRemoteandOffshoreMedicine Foundation

Summer 2022

Theofficialnewsletterofthe CollegeofRemoteandOffshoreMedicine Foundation

It is fantastic to see the College return to “normal” after two and a half years of COVID lockdown. This week, we have our first post-COVID Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills course running in Malta. We have delegates from six countries coming together in Pretty Bay to learn about tropical diseases and expedition medicine.

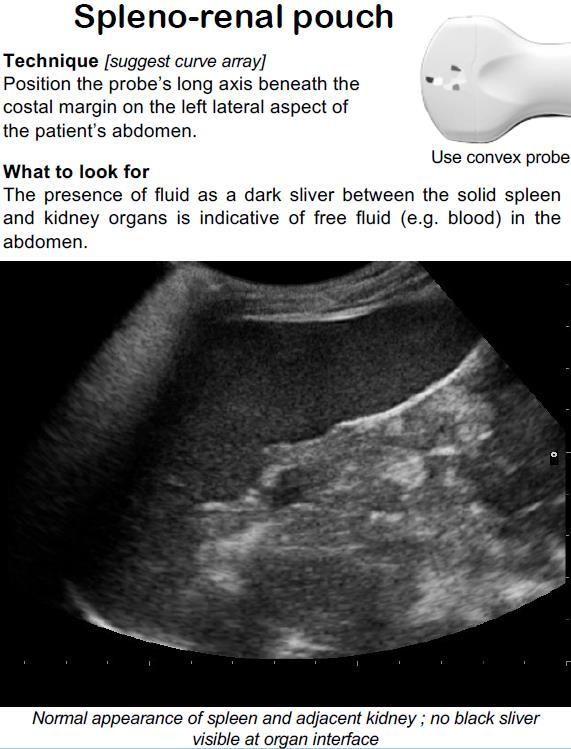

Next week we begin the Advanced TTEMS in Malta, followed by our first Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound (APUS) course. I have personally looked forward to the APUS course, as it was built specifically for healthcare professionals working in austere environments. I attended the Royal College of Emergency Medicine’s Level 1 Ultrasound course last week, and thoroughly enjoyed seeing how RCEM teaches their programme. We at CoROM plan to follow a similar pathway with Level 1 Ultrasound certification.

Earlier this month, the College hosted an exhibition table again at the Special Operation Medicine’s Scientific Assembly in Raleigh, NC. Three of our faculty spoke at the conference, and all of our delegates thoroughly enjoyed reconnecting with old mates and meeting new friends.

As the College moves into the summer recess, our faculty and staff will have time and space to review the curriculum that students have completed in the 20212022 academic year. We will review the applications for degrees that several students have earned and confer those degrees in late August. This is the first cohort to graduate from our programmes since Covid started. We are delighted to see our graduates complete their training and move on to bigger and better things.

Here at the College, we wish the very best of summer to all of our faculty, staff and students, and the Members of the College and all of you who have supported our efforts in this academic year.

As the College forges ahead into the semi-post COVID era, we are reminded in Nicole Foster’s piece on monkeypox (page 5) that the world is still teeming with zoonotic infectious diseases lying in wait for the unwary, the unprotected and the uneducated. Virtually all of the recent and ongoing epidemics owe their origins to animals – HIV, SARS coronavirus 1 and 2, MERS, Zika, West Nile, Ebola, and now monkeypox. Some of the most catastrophic epidemics in history have also been zoonoses – plague, the eastern variant of African trypanosomiasis, swine and avian influenza, and yellow fever, just to name a few. Malaria, the disease probably responsible for more human deaths than any other cause in history, was already an ancient zoonosis when Homo sapiens made its first appearance on the African savannah. Being the highly adaptable protozoa that it is, some strains of malaria were selected to prefer the human host, thus shedding the zoonosis moniker. While four species of Plasmodium call humans home, Plasmodium knowlesi and a handful of other ‘simian’ malaria species continue to spill over into the human population with little difficulty.

Staying ahead of the curve with regards to emerging infectious diseases is just a part of what drives me towards my goal of mastery within the domains of infectious diseases, pathobiology, and immunology.

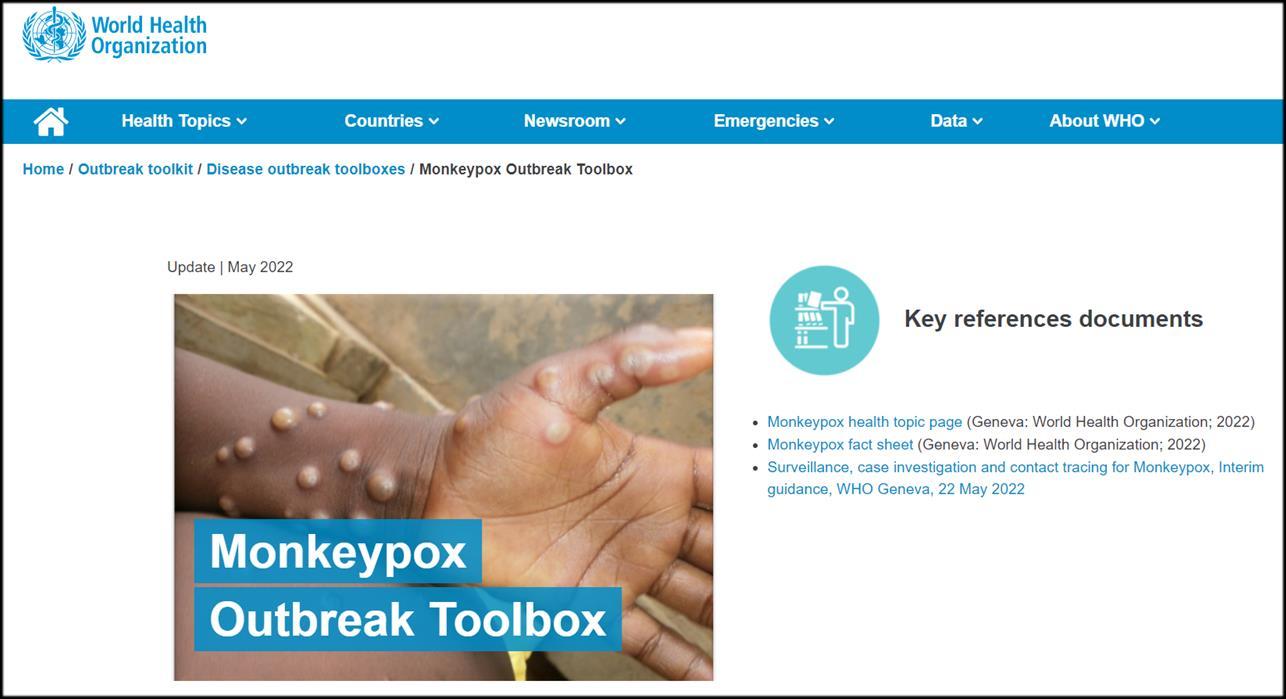

At the conclusion of Nicole’s informative monkeypox piece is a link to the World Health Organization’s ‘Monkeypox Outbreak Toolbox’ for readers who wish to know more.

Dr. Mike Shertz follows with a graphic case study on imported cutaneous myiasis.

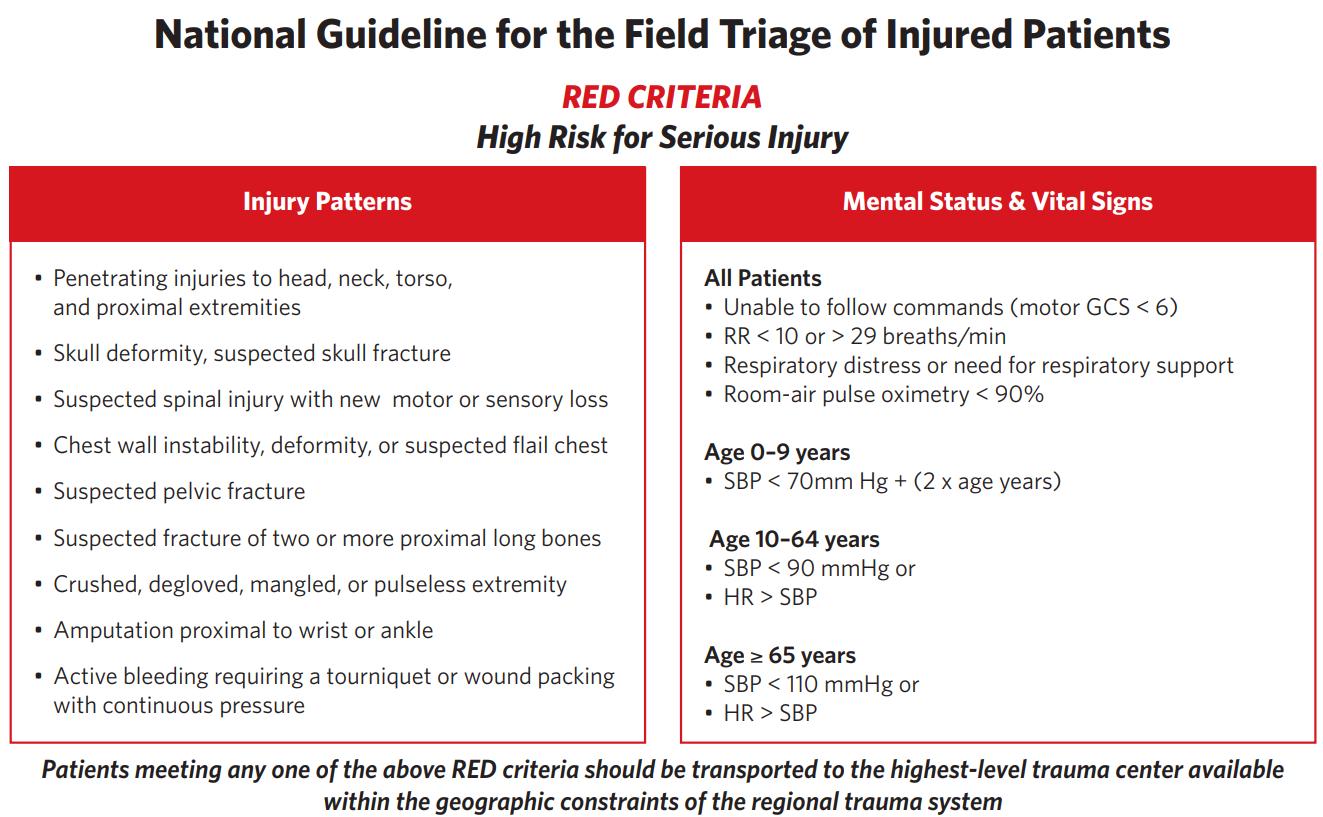

Our regular Trends in Traumatology piece looks at the latest triage guidelines from the American College of Surgeons, based on 2021’s “National Guideline for the Field Triage of Injured Patients: Recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2021” by Dr. Craig Newgard, et al.

CoROM president Aebhric O’Kelly shares the ‘scratch test’ in Improvised Medicine, followed by the usual clinical challenges within Test Yourself, plus four recent journal articles that caught my eye.

Jason Jarvis is CoROM’s Press Chair and an associate lecturer in Tropical Medicine. He is a paramedic and former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan He recently completed his first transect of Africa, teaching deployment medicine courses for healthcare providers in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya under the auspices of the United Nations. Based in Seattle, Jason is a medical educator for Virtus, Harborview Medical Center, Raider Tactical, Allied Universal, 4 Site Group, CPR Seattle, LifeTek, and Children’s Hospital of Seattle He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for the Journal of Special Operations Medicine and International Health, and is pursuing a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Name:

Monkeypox - Orthopoxvirus genus in the family Poxviridae

Brief description:

A viral zoonosis with two clades. The West African clade (case mortality rate 3.6%) and the Congo Basin clade (case mortality rate 10.6%). The Orthopoxvirus genus also includes variola (smallpox), vaccinia (used in the smallpox vaccine), and cowpox.

First identified:

First human case in a child in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970; first identified in monkeys in 1958.

Reservoir host:

Rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, non-human primates and other species. Further studies are needed to identify the exact reservoirs and how virus circulation is maintained in nature.

Transmission:

The disease spreads from animals to humans by bites, or by touching an infected animal’s blood, body fluids or fur, or eating its partially cooked meat. Human to human transmission occurs by close contact with lesions, body fluids, respiratory droplets and contaminated materials such as bedding.

Incubation period:

Usually from 6 to 13 days but can range from 5 to 21 days.

Endemic countries:

Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Ghana (identified in animals only), Ivory Coast, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan.

Signs/Symptoms:

The illness begins with the ‘invasion period’ - fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion. Within one to three days (sometimes longer) after the appearance of fever, the patient develops skin eruptions which tend to be concentrated on the face and extremities rather than on the trunk. It affects the face (in 95% of cases), and palms of the hands and soles of the feet (in 75% of cases). Also affected are oral mucous membranes (in 70% of cases), genitalia (30%), and conjunctivae (20%), as well as the cornea. Lesions progress through the following stages before falling off: macules, papules, vesicles, pustules and scabs. The illness typically lasts 2−4 weeks.

Nicole Foster FAWM MPHTM BScTreatment:

At this time, there are no specific treatments available for monkeypox infection, but monkeypox outbreaks can be controlled via smallpox vaccine, cidofovir, ST-246, and vaccinia immune globulin (VIG)

Vaccine?

Historically, vaccination against smallpox had been shown to be protective against monkeypox. Cross-protective immunity from smallpox vaccination is limited to older persons, since populations worldwide under the age of 40 or 50 years no longer benefit from the protection afforded by prior smallpox vaccination programmes. There is little immunity to monkeypox among younger people living in non-endemic countries since the virus has not been present there.

While one vaccine (MVA-BN) and one drug treatment (tecovirimat) were approved for monkeypox - in 2019 and 2022, respectively - these countermeasures are not yet widely available.

Healthcare precautions?

A combination of standard, contact, and droplet precautions should be applied in all healthcare settings when a patient presents with fever and vesicular or pustular rash.

Outbreak!! What’s happened?

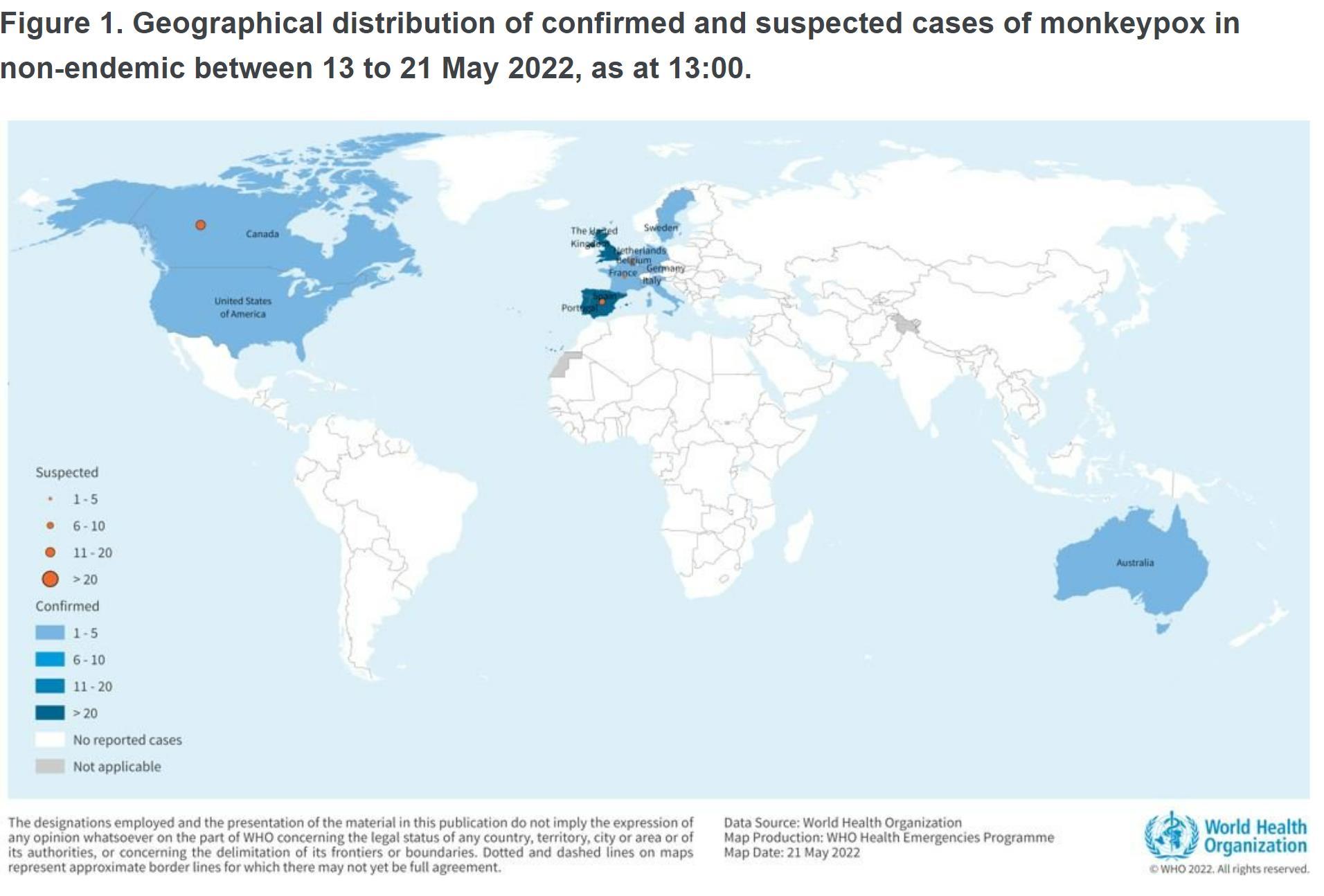

As of 21 May 2022, 92 laboratory confirmed cases, and 28 suspected cases of monkeypox, have been reported to WHO from 12 Member States that are not endemic for monkeypox virus, across three WHO regions. No associated deaths have been reported to date. All cases that have been confirmed by PCR have the West African clade.

Such a large increase in cases of monkeypox in countries that are not endemic has caused an increased awareness and concern by public health and surveillance organisations. This is the first time that chains of transmission have occurred without known epidemiological links and travel history in west and central Africa.

Increased contact tracing, isolation and supportive care to limit further onward transmission. The WHO is expecting further cases in non-endemic areas to be reported. Available information suggests that human-to-human transmission is occurring among people in close physical contact with cases who are symptomatic. The most probable reason (but not exclusive) for the case increase in these regions has been traced to super spreader events attended by men who have sex with men (MSM). Further investigations are ongoing. This is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, rather it is the close skin to skin contact that is furthering transmission.

WHO surveillance case definitions (non-endemic countries) - case definitions will be updated as necessary

Suspected case:

A person of any age presenting in a monkeypox non-endemic country with an unexplained acute rash

AND

One or more of the following signs or symptoms, since 15 March 2022:

• Headache

• Acute onset of fever (>38.5oC),

• Lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes)

• Myalgia (muscle and body aches)

• Back pain

• Asthenia (profound weakness)

AND

For which the following common causes of acute rash do not explain the clinical picture: varicella zoster, herpes zoster, measles, Zika, dengue, chikungunya, herpes simplex, bacterial skin infections, disseminated gonococcal infection, primary or secondary syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, molluscum contagiosum, allergic reaction (e.g., to plants); and any other locally relevant common causes of papular or vesicular rash.

N.B. It is not necessary to obtain negative laboratory results for listed common causes of rash illness in order to classify a case as suspected.

Probable case:

A person meeting the case definition for a suspected case AND

One or more of the following:

• has an epidemiological link (face-to-face exposure, including health workers without eye and respiratory protection); direct physical contact with skin or skin lesions, including sexual contact; or contact with contaminated materials such as clothing, bedding or utensils to a probable or confirmed case of monkeypox in the 21 days before symptom onset

• reported travel history to a monkeypox endemic country in the 21 days before symptom onset

• has had multiple or anonymous sexual partners in the 21 days before symptom onset

• has a positive result of an Orthopoxvirus serological assay, in the absence of smallpox vaccination or other known exposure to Orthopoxvirus

• is hospitalized due to the illness

Confirmed case:

A case meeting the definition of either a suspected or probable case and is laboratory confirmed for monkeypox virus by detection of unique sequences of viral DNA either by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and/or sequencing.

Discarded case:

A suspected or probable case for which laboratory testing by PCR and/or sequencing is negative for monkeypox virus.

Resources

Nicole Foster is the Associate Vice President of Academic Affairs and is the Undergraduate Coordinator for the College. She is a critical care paramedic and specialises in remote and austere environments. She is based in Perth, Australia.

A 35-year-old male presents to the Emergency Department with a “mosquito bite” on his right shin. It occurred while on vacation in Guatemala several weeks ago and has not resolved. He is convinced he can feel something “moving inside it.” He has a several millimeter, slightly erythematous nodule with a central “hole” within it on his shin.

Review of Symptoms:

Mild pain and itching at the nodule. No other symptoms.

Differential diagnosis for a papular or nodular lesion post-travel to the Americas is broad. Insect bites tend to occur on exposed skin. Early cutaneous leishmaniasis could appear similarly with a nodular appearance early after a sandfly (Lutzomyia spp.) bite. Most rashes would involve more than one lesion. The subjective feeling of movement is classic for this condition.

Presumptive Diagnosis: Cutaneous myiasis.

Treatment:

Manual removal of the larva.

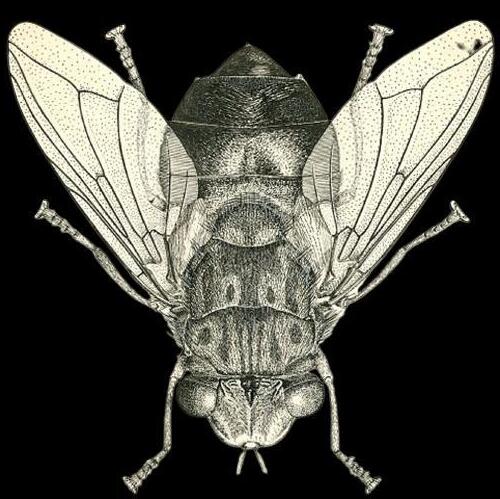

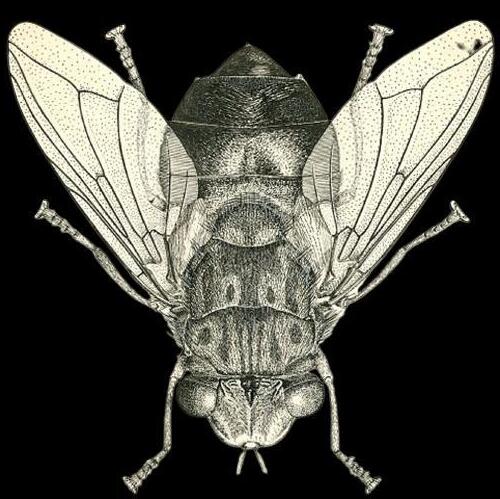

Causative Organism: Larva of Dermatobia hominis, also known as the tropical bot fly.

Adult Dermatobia hominis fly, whose larvae is a major cause of cutaneous myiasis in Central and South America.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D MD DTM&H

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D MD DTM&H

Geographic Distribution:

The tropical Americas and sub-Saharan Africa (other types of bot flies).

Myiasis is the infestation of human tissue by fly (Diptera) larva. It can occur in open wounds or intact skin depending on the fly type. Cutaneous myiasis, as in this case, is a common skin related complaint in returning travelers.

Dermatobia hominis, one of the most common causative flies, captures mosquitos and applies its larval to their abdomens. As the mosquitos are biting the host, the larva detaches and penetrates intact skin.

The typical lesion is an erythematous papule or nodule with a central “puncture” through which clear to purulent, sometime bubbly, fluid might drain. The lesions typically occur on “exposed” skin. That central pore is the respiratory spiracle of the larva through which it breathes. Itching, pain, and movement in the nodule, frequently at night, are often reported. Once the larva matures it will drop from the nodule. This can take a few months. The lesions usually heal without any scarring. Secondary bacteria infections can occur.

Treatment generally is by application of a toxic or occlusive substance to the lesion to encourage the larva to start to extract itself. Once partially extruded, gentle manual traction / pressure on the lesion edges will extract the larva intact. The black spicules on the larva provide it traction within the wound. Aggressively pulling the larva out of the wound will tear it apart with resultant infection. Occlusive substances like petrolatum, topical antibiotics, and bacon over the ‘breathing hole” have been used to essentially asphyxiate the larva. It can take 24 hours for the larva to start to extrude itself.

For a review of all types of myiasis see Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012 Jan;25(1):79-105.

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former US Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

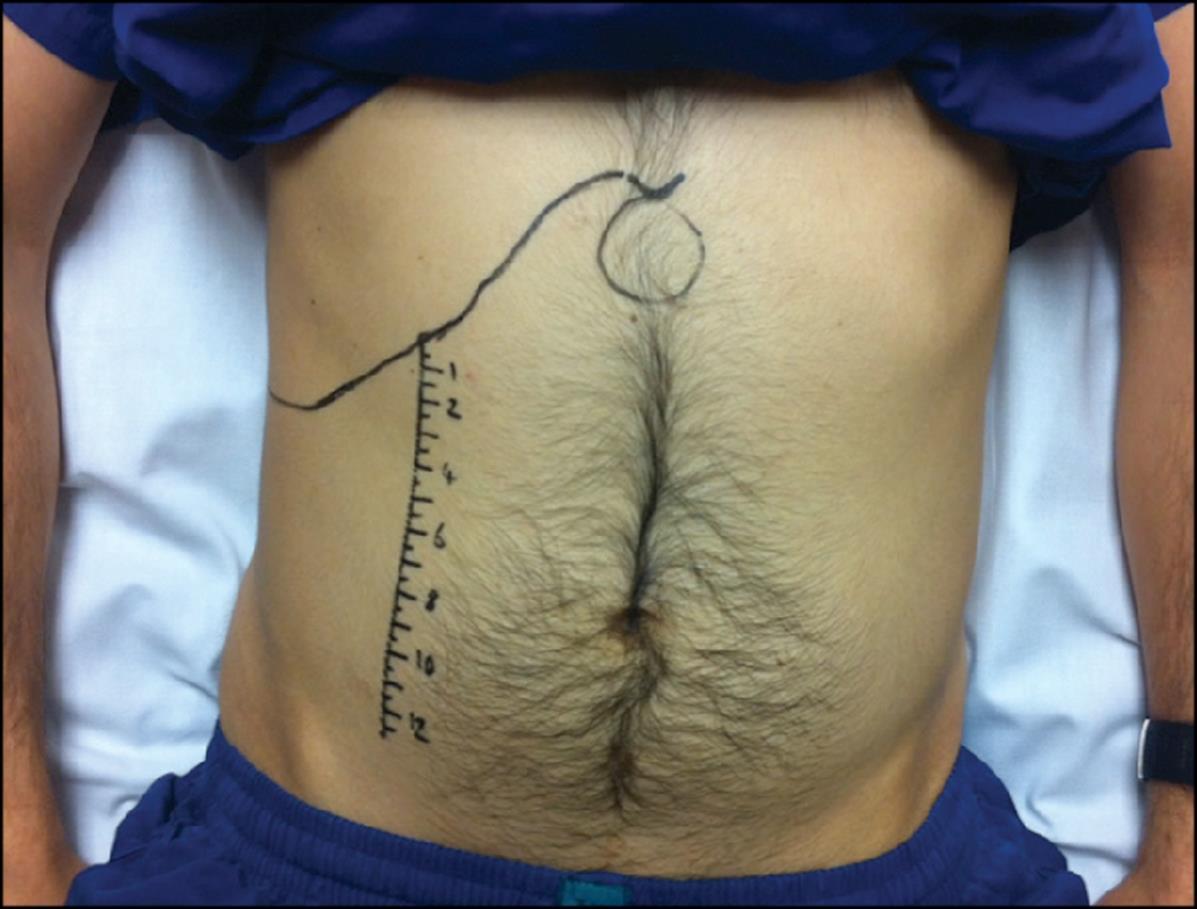

For the austere healthcare provider, clinical assessment skills are extremely important. We often lack resources found in an A&E department. The ‘scratch test’ is a tool for outlining the solid organs of the abdomen and for detecting large amounts of blood vs air. It works because sound transmits differently through solid vs hollow objects.

Equipment:

• Stethoscope

• Pen, preferably a sharpie, but a ballpoint works fine

• A fingernail

How to do this:

• Place the stethoscope below the right rib cage on the midclavicular line. This is right over the liver.

• Scratch the skin surrounding the stethoscope. Listen for the drop in sound volume.

• Mark with the pen where the sound volume changes.

Your pen marks will create an outline that looks like the shape of a liver. You hear the dull sound of a blood-filled organ. Once you move past the liver, the sound will decrease due to the lack of blood conducting the sound of the fingernail scratching the skin. This test can also detect an enlarged spleen.

Take home message: There is no excuse for not having an ultrasound with you anywhere you work as a healthcare provider. But we work in less-than-ideal environments, and electronics lose battery power or get wet or stop working. It is essential to have other clinical skills in your toolbox to assess the critical casualty.

Resources:

1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3598244/

2. http://depts.washington.edu/physdx/liver/tech.html

3. https://griddownmed.blog/2015/02/10/the-scratch-test-the-resource-poor-mansultrasound/

The concept of triage continues to evolve. I recently came across an early example of triage in John Keegan’s military classic The Face of Battle, in which casualties from WWI’s Battle of the Somme were triaged into three categories (from the French etymology of the term): the expectant, those needing immediate surgery, and those whose surgery could wait until they had been shipped rearward.

One hundred five years later, the American College of Surgeons has given us the latest science has to offer concerning triage in the National Guidelines for the Field Triage of Injured Patients. This guideline is based on the 2021 paper by Dr. Craig D. Newgard, et al, the background of which appears on page 14 of this newsletter. From the American College of Surgeons:

“The 2021 National Guidelines for the Field Triage of Injured Patients or ‘Guidelines’ are now available. A multidisciplinary expert panel led by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) undertook this revision with support from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau, and EMS for Children Program.

For three decades, the Guidelines have been widely adopted by trauma systems in the United States to support decision making by EMS clinicians in transport destination determinations for injured patients. The goal has been to ensure that seriously injured patients are transported to the most clinically appropriate trauma centers.

The 2021 revision was based on a scientific literature review conducted by Oregon Health and Science University as well as the results from a broad stakeholder feedback tool, which aimed to capture the perspective from those in the field.”

In the United States, unintentional injury remains the leading cause of death and years of potential life lost among children and young adults, and the third most common cause of death overall.1,2 Injury is the most common reason for use of 9-1-1 emergency medical services (EMS) in the US,3 with EMS playing a critical role in the early evaluation and care of injured patients.4 An important aspect of EMS care is field triage - the process of identifying seriously injured patients in need of care in specialized trauma centers from among the larger number of patients with minor to moderate injuries who can be cared for in nontrauma hospitals. To accomplish this task quickly and efficiently, EMS clinicians use specific prehospital criteria known as the field triage guideline. The triage guideline was originally developed in 1976, with periodic revisions every 5 to 10 years.5 The most recent evidencebased revisions to the field triage guideline were completed in 2011.6 Concentrating the most seriously injured patients in trauma centers through field triage is predicated on the principle that patients have better outcomes in these hospitals. A landmark study demonstrated 20% lower in-hospital mortality and 25% lower 1-year mortality among seriously injured adults treated in Level I trauma centers compared to non-trauma hospitals.7 Other studies have shown that regionalized trauma systems are associated with reductions in mortality,8-11 with the benefit driven primarily by Level I trauma centers.8,9 The benefits are similar for children, particularly when treated in pediatric trauma centers12-14 and in trauma centers with high emergency department (ED) pediatric readiness.15,16 For older adults, the benefit of tertiary trauma centers is less clear, with some studies showing reduced mortality17,18 and others no effect.7,19 Until the evidence becomes clearer, the prevailing view is that seriously injured older adults should be managed in trauma centers. The effectiveness of field triage is measured at the system level using metrics termed “under-triage” and “over-triage”. Under-triage is the percentage of seriously injured patients missed by field triage processes and transported to non-trauma hospitals, which is associated with increased mortality in adults and children.20-23 Over-triage is the percentage of patients with minor to moderate injuries identified by field triage criteria as having serious injuries and transported to trauma centers unnecessarily, representing overuse of limited resources and inefficiency in the system. Under- and over-triage are inversely related.24 Trauma systems have prioritized the goal of minimizing under-triage and accepting a higher level of over-triage to avoid increased mortality, with targets set at ≤ 5% and ≤ 35%, respectively.4 A systematic review of field triage performance across all ages showed 14% to 34% under-triage and 12% to 31% over-triage.25 Under-triage of children is up to 51%26 and has increased with recent triage guidelines.27 Under-triage is highest among older adults,28-30 with half of seriously injured older adults treated in non-trauma centers nationally.31 Reducing under-triage was an important goal of the Panel for the current guideline revision. The purpose of this report is to present the final 2021 field triage guideline and to describe the process of guideline development and the supporting evidence. The guideline is intended for use in civilian 9-1-1 EMS systems and is not intended to guide mass casualty events or in-hospital trauma team responses. The evidence to support the current guideline is based on civilian trauma systems. The guideline is intended for patients in whom maximal resuscitative care is appropriate and does not apply to patients with limited goals of care.

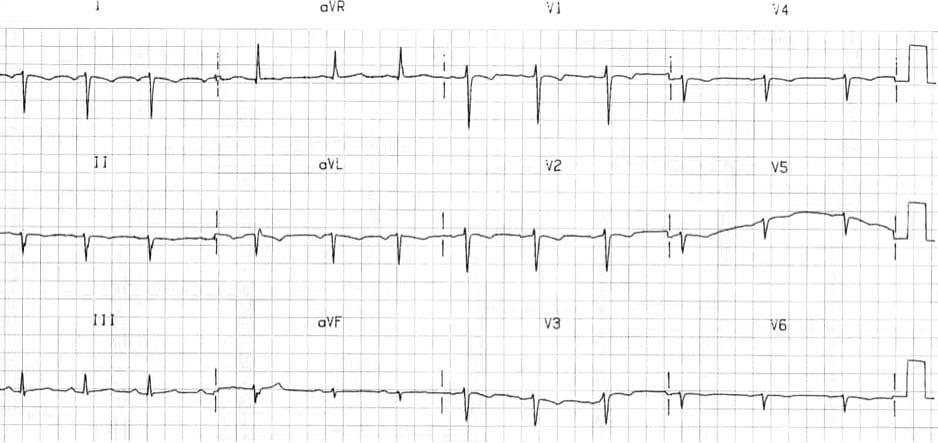

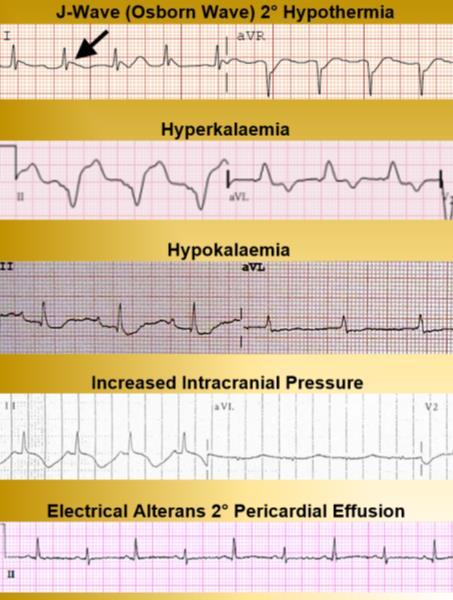

While deployed on a humanitarian mission to Uganda, you are caring for a two-year old girl whose parents say she has suffered from malaise since birth. What cardiac anomaly can you ascertain from her ECG?

A. Dextrocardia

B. Pericardial effusion

C. Complete heart block

D. Patent ductus arteriosus

In order to buffer the pH of lidocaine, your medical team leader asks you to draw up 252 mg of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate. What volume of this drug should you prepare?

During a salvage dive in the South China Sea, one of the SCUBA divers surfaces and presents with a Glasgow Coma Score of 9 (2/2/5). The patient’s mental status improves but with a reduced Glasgow Coma Score of 14 (3/5/6), accompanied by loss of sensorium at the left cymba conchae (pictured). The patient admits he panicked while deep underwater and swam quickly to the surface without exhaling. You suspect the patient is suffering from an arterial gas embolism; based on the clinical picture, at which anatomical structure is the embolism most likely located?

A. Vagus nerve

B. Vestibulocochlear nerve

C. Anterior cingulate gyrus

D. Capsule of atlanto-axial joint

cymba conchae

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue: ECG: B. High-lateral STEMI.

Clinical calculation: Combine 0.4 mL morphine with 9.6 mL saline. Clinical case: B. Neisseria meningitidis.

Gear SAROS™

Portable Oxygen Concentrator

Designed for Military Use

available at https://www.caireinc.com/product/saros/

The SAROS Oxygen System was designed to address the logistical and safety challenges associated with high-pressure oxygen cylinders while providing medical grade oxygen on the battlefield. Its traditional cylindrical shape makes it ideal for placing on the stretcher with the patient, and for storage on existing oxygen storage racks commonly found in emergency transport vehicles. These units are designed to be robust and reliable for operation in extreme temperatures and in the harshest environments.

The SAROS 3000 has 510(k) clearance by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada. It meets Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) guidelines for medical evacuation on Black Hawk helicopters and commercial air flights.

For SAROS 3000 specifications, click here.

American Family Physician

15 January 2021.

https://www.aafp.org/afp/2021/0115/od4.html

Slawson D, Garcia C.Lido/Epi is one of the most commonly used local anesthetics for office-based procedures The acidic nature of lidocaine is thought to be responsible for the burning sensation during infiltration. NaHCO is used as a buffering agent to minimize acidity and reduce pain during infiltration The investigators recruited 48 healthy volunteers, 18 to 75 years of age, who randomly received (allocation concealed) either two or four infiltrations of 2-mL Lido/Epi buffered with NaHCO at room temperature in mixing ratios of 3:1, 9:1, or 10:0 (unbuffered), or a placebo (sodium chloride 0 9%) Mixing occurred within one minute before infiltration, and the injections randomly occurred on various sites of the right and left forearm. All participants completed the trial and no serious adverse events occurred Study participants rated the 3:1 mixture as significantly less painful than the 9:1 mixture (median pain score is 1.5 points lower on a 10-point scale, where 0 = no pain and 10 = unacceptable pain, when 3:1 mixture is given first, and 0.5 points lower when given second) The unbuffered mixture was more painful than the 3:1 and 9:1 mixtures, and the placebo mixture was notably the most painful of all the injections.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine Spring 2022.

DOI: 10.55460/ABX3-D3G2.

Ivory JW, Jenzer AC.

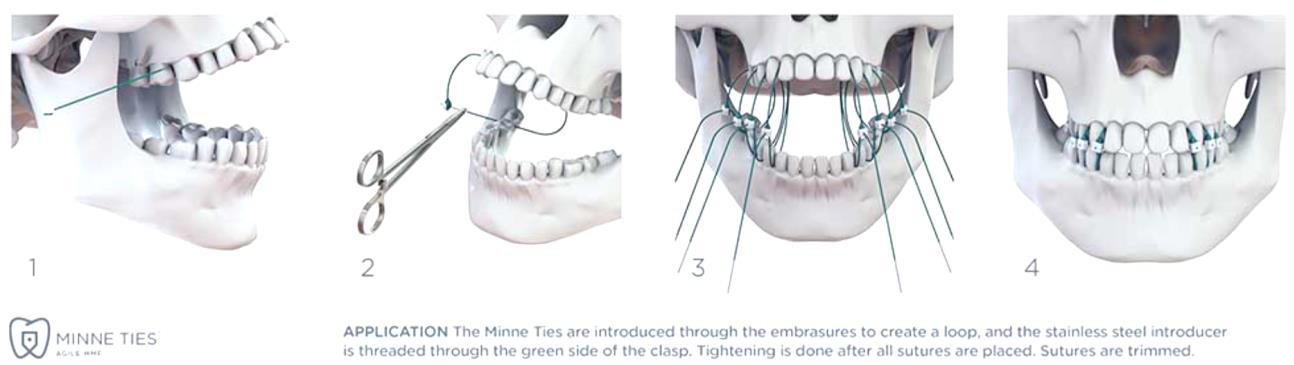

Application of maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) for the treatment of jaw fractures has a long history stretching back thousands of years. Modern methods of MMF require extensive training for correct application and are often not practical to perform in a forward operating environment. Most MMF methods carry inherent risks of sharps injuries and exposure to bloodborne pathogens. The authors present a method of MMF with Minnie Ties, which are simple, effective, and much safer than traditional methods of MMF.

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine

1 March 2022.

DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2021.11.009.

Gaudio F, et al.

Accounts of anaphylaxis date back to the earliest recorded history

Hieroglyphs from 2640 BC depict the pharaoh Menes dying after a wasp sting 1 Today, anaphylaxis continues to be a serious medical issue. An estimated 2 to 5% of the US population has experienced anaphylaxis. In addition, between 1999 to 2010, there were a total of 2458 anaphylactic deaths, a figure that may reflect underreporting. Although such deaths appear to be rare, estimated at 0 1% of all emergency department (ED) visits and 1% of all hospital admissions for anaphylaxis, the potential for sudden and unpredictable fatality is an ever-present concern for at-risk individuals and their families 2 In remote areas or wilderness settings, access to standard medical care may be limited or delayed. To help increase the availability of life-saving treatment, the Wilderness Medical Society published clinical practice guidelines in 2010 and 2014 supporting the concept that nonmedical professionals whose duties include providing first aid or emergency medical care in the field also be trained to administer epinephrine for anaphylaxis 3,4 Examples of such professionals include expedition leaders, outdoor instructors or guides, park rangers, and camp directors. The current guidelines expand the focus from the administration of epinephrine by trained nonmedical professionals to the broader field treatment of anaphylaxis, with consideration for hospital-based treatment

The Lancet Global Health

21 April 2022.

DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00007-9.

Malembaka EB, et al.

Despite being one of the oldest known infectious diseases, cholera typically caused by toxigenic Vibrio cholerae bacteria of serogroup O1 still causes between 1 and 4 million cases per year 1

Most cholera cases reported to WHO between 1996 and 2018, excluding the 2010 Haitian and 2017 Yemen epidemics, have occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which also has the highest case-fatality rates (eg, 2% in 2018) 2

An estimated 87 million people in SSA live in districts with high cholera incidence 3

Cholera transmission spans the endemic–epidemic spectrum across SSA, with large heterogeneity in transmission characteristics across time and space.4, 5

Tailoring cholera prevention and control programmes to local epidemiological characteristics might be one efficient way to reach global targets for cholera control,6 although detailed systematic descriptions across broad geographies remain sparse.

Seasonality is one important aspect of cholera epidemiology, and cholera exhibits strong seasonal patterns in countries on the Bay of Bengal The seasonal patterns of cholera in coastal and estuarine areas in this region have been linked in part to the ecology of V cholerae in its natural brackish water habitats.7

8

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority. License No. 2018-022.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

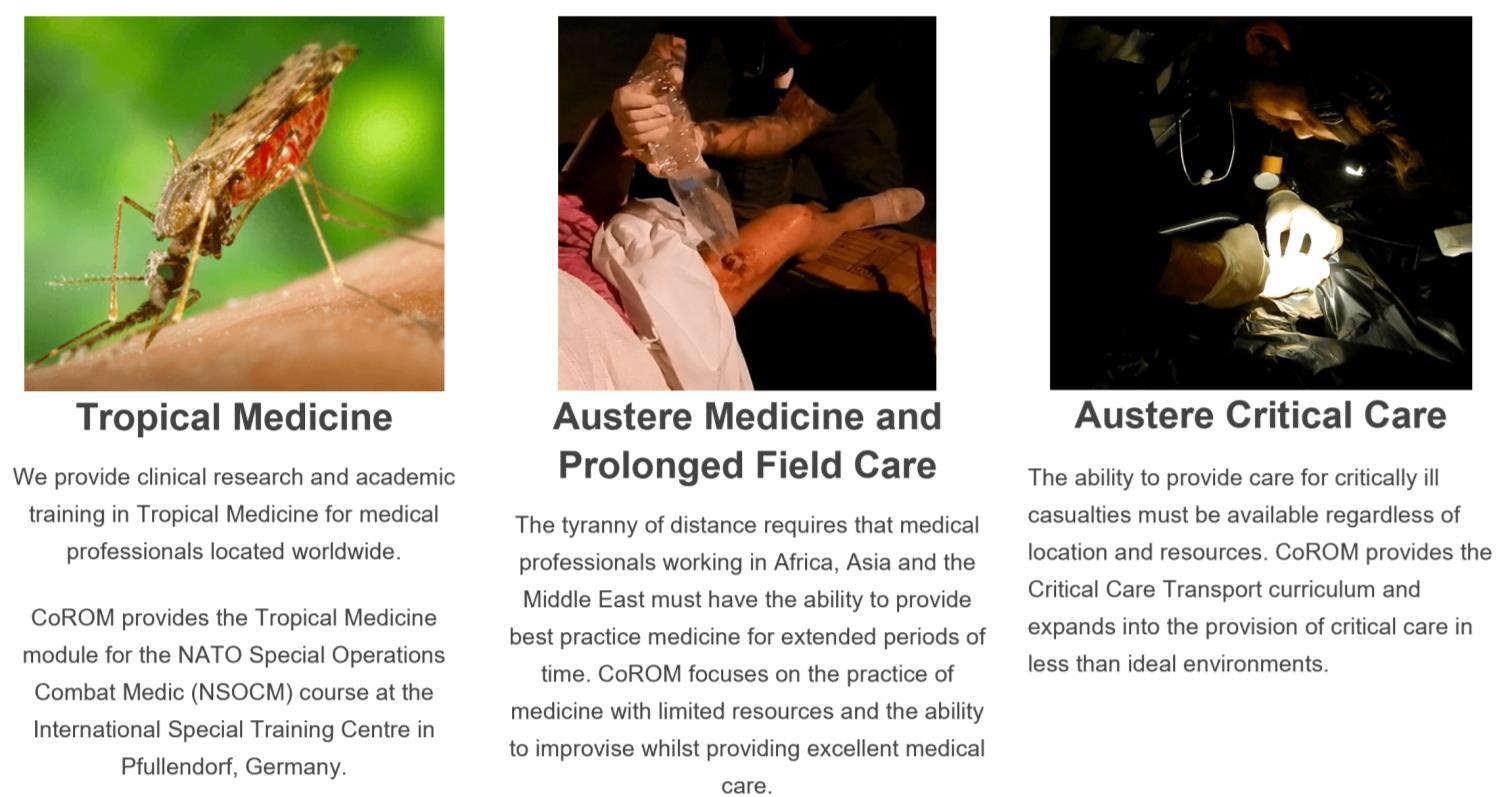

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionalsworking in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

WASHINGTON STATE

MFSLR 6 July NORWAY TTEMS (closed course) October 2022

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

Degree Programmes

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice

Doctor of Health Studies

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Ghana National Ambulance Service

ACC Acute critical care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS

Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.edu.mt

The purpose of this questionnaire is to identify gaps in the knowledge or skills that clinicians have gained whilst practicing since they have completed their studies / course (it doesn’t necessarily need to be a course completed within the College. All identifying data will be removed and will be kept confidential. Your answers will help the College better understand the learning gaps of students.

Survey available here:

We are collating information and data from current paramedics, students and alumni about the requirements to practice as a paramedic in different countries. We invite you to add to this database. It will be available from the College in 2022.

Survey available here:

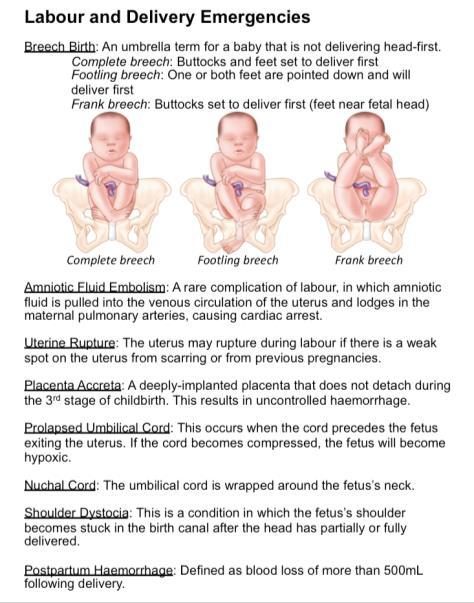

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

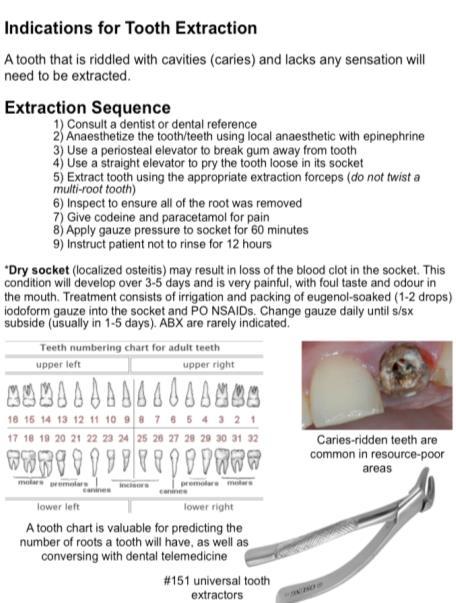

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

Canine medicine

…and much more!