Summer 2021

Summer 2021

The College has been busy during the spring semester. Our first-year BSc students are progressing through their online modules and are preparing for the three weeks of hands on skills training in Malta in August. We hope that this is the last disruption to our academic schedule due to the CoVID pandemic. This past weekend I was able to fly down to Malta for the first time in 14 months. It was good to get back into the classroom and start setting things up for the coming classes.

We have had quite a turnout for our MSc Austere Critical Care programme. The College will have to have two separate cohorts in order to accommodate all of the delegates who have registered for the programme. We have a superb curriculum ready to launch that starts with a weeklong skills training session in October in Malta.

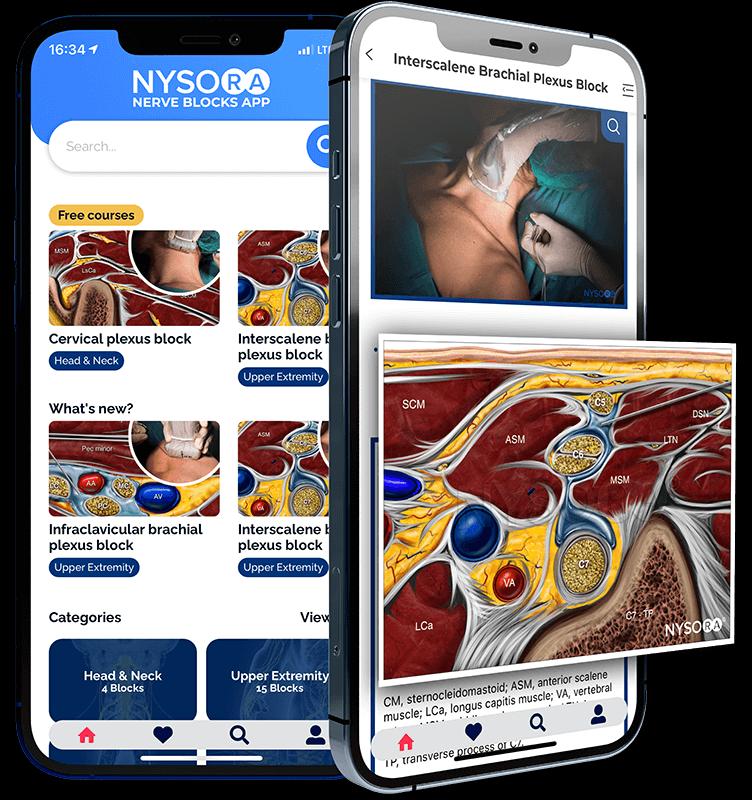

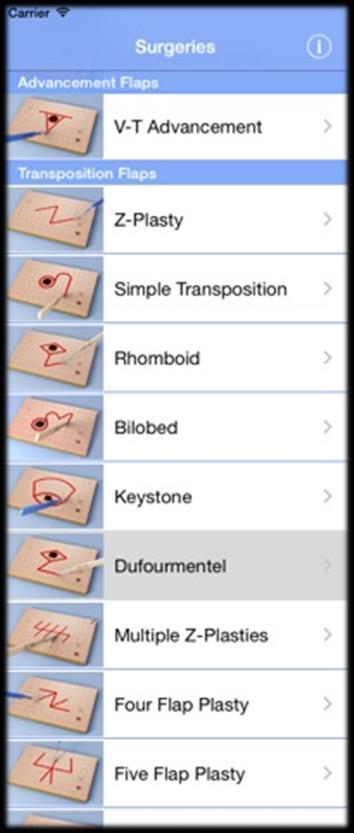

The new virtual Field Guide has sold quickly, with several hundred people subscribed to the application. We have been busy working on additional content that will become available in a few months. One of the many benefits of adding a virtual option to the Field Guide is that additional content can be uploaded onto that platform with little effort. Keep an eye on social media for updates.

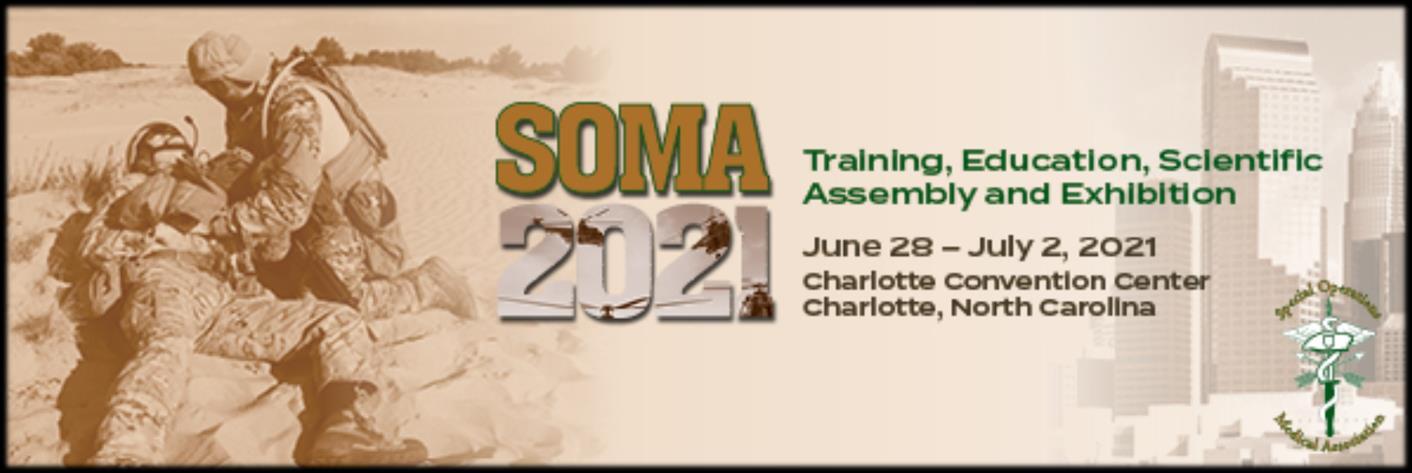

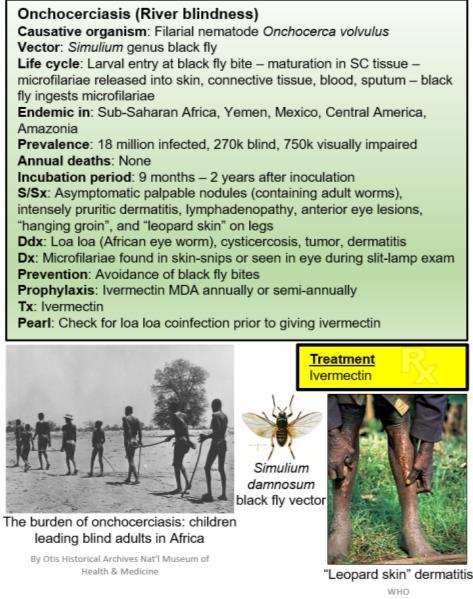

The College returns to the Special Operations Medical Association’s conference in Charlotte in June, at which we have been asked to continue giving presentations. Jason Jarvis will give another update on Tropical Medicine for the SOF medic, while I will be giving my Tactical Medicine Workshop again and will work with John Clark from IBSC on administering the TP-C, FP-C and CCP-C exams. The College is hosting an exhibition table as usual and will be giving free access to the virtual Field Guide to anyone who stops by our booth.

As this pandemic transitions into a ‘new-norm’ and we adjust to new travel requirements and socialdistanced classroom teaching, the College will continue providing evidence-based healthcare education for the remote, austere and resource-limited environments.

The College has been making great strides in its educational offerings and there seems to be no stopping this momentum. I am pleased to offer up the Summer 2021 edition of The Compass, with some of the usual features plus a very special historical writeup from Dr. Nick Williams, beginning on the next page. His article struck a deep cord in me as I had recently worked in eastern Africa and heard first-hand accounts of the calamities he describes.

CoROM faculty Nicole Foster follows with a look at ILCOR, the place quality medical research is synthesized into international clinical practice guidelines.

Dr. Mike Shertz presents a recent case report on a chemical exposure I doubt many readers of The Compass have seen – mustard agent.

CoROM dean Aebhric O’Kelly gives us the next instalment in his Improvised Medicine series, on what is perhaps the ultimate in field medical improvisation: the improvised tourniquet.

Rounding out this issue is Test Yourself (chockfull of austere medicine scenarios that I probably have way too much fun designing), a couple of my favorite medical apps, an everyday carry trauma kit, some interesting journal articles, a review of Envisioning Information (yet another terrific title recommended by Columbia University parasitology professor Dickson Despommier) and of course the CoROM calendar of events.

Jason Jarvis is a paramedic and former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan. He recently completed his first transect of Africa, teaching deployment medicine courses for healthcare providers in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya under the auspices of the United Nations. Based in Seattle, he is a medical educator for Virtus, Harborview Medical Center, Raider Tactical, Allied Universal, 4 Site Group, CPR Seattle, LifeTek, and Children’s Hospital of Seattle. He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for International Health, and is working towards a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Summer of 1994 saw the country of Rwanda descend into chaos, anarchy and death. Precipitated by tribal unrest, bitterness, and warfare between Hutu and Tutsi factions, the early days of the conflict were dominated by wholesale killing, often by machete dismemberment.

The result of the genocidal atrocities was a mass migration across the Rwandan border to United Nations organized camps in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo). In the near vicinity of the town of Goma, three main camps developed, containing an estimated three million refugees, mostly of Hutu tribal affiliation. Conditions were appallingly primitive. Occupants were issued a blue UN plastic tarp and a set of aluminum cooking pots. Camp residents were left to construct their own domelike huts from local materials with the tarp for rain proofing. The floor was the base volcanic rock. About twice a week, cooking oil, grain or beans and maize were delivered, forming the base nutritional support plan.

Our team of 12 healthcare specialists arrived in the area shortly after the establishment of the camps. Our area of responsibility comprised an estimated 60,000 residents, ranging in age from newborn to very elderly. Many unaccompanied children were present, living together in groups of up to 12 in a single hut, the absent parents victims of genocide.

Not speaking much of the local language, we hired an interpreter from the camp population to help us with not only the always-present language challenge but also with the immense task of trying to assimilate our team into the complex society of the camp.

Her name was Veniranda, but she was known to us as Veni, and she immediately became indispensable to our operation. Perhaps 25 years old, Veni personified optimism and hope. Always a smile. Always a good word. No matter what. Veni was a law student before the war and saw no reason why this episode should alter her life’s ambition.

As the weeks went by, the full expanse of the medical catastrophe before us unfolded. Our scope included insect infested wounds not primarily closed in the field, repair of cervix lacerations after unattended childbirth, and wholesale outbreaks of cholera and shigella. This was the home stable for the Four Horsemen – War, Famine, Pestilence and Disease.

It became clear that a supply of clean, drinkable water for the camps was a critical need. But how could this be accomplished? An interesting fact worth remembering is that there are people who own swimming pools in every corner of the world. Therefore, pool chemistry in the form of dry chlorine can almost always be found. A new use for UN blue tarps was discovered. By digging a depression in the hard ground and lining it with plastic, a water pool can be created. Add chlorination and an old pumper fire truck, and the water problem is answered! The water/chlorine solution was hand mixed with boat oars and transported to the camps by truck. This proved to be the solution to our deadly cholera outbreak.

Here is where the story takes a turn, however. Dry chlorine buckets are always marked with cautions about the toxic nature of the contents, usually in the form of a skull and crossbones so everyone gets the message. These notifications did not escape the attention of the ubiquitous “observers” in the region, and a rumor shortly arose that the cholera epidemic was a hoax and that camp residents were being poisoned by the western healthcare workers. Immediately the leader of a neighboring country in the region issued orders for the summary decapitation of western health workers, allegedly with a bounty to be paid!

This posed a serious problem. An emergency meeting was called in our GP medium tent to discuss options. Astonishingly, a few argued for continuing on as normal. This was rejected instantly, and it was decided that the 12 of us would load up in our two trucks and proceed immediately to the French military camp adjacent to the Goma airport, stopping for nothing. From the airport to Nairobi, Kenya, by whatever means available. When planning an emergency exfiltration, it’s best to keep it simple.

We filed out to make preparations for our escape, leaving only one teammate. Veni. In tears. Veni had two serious problems. First, she was born of mixed heritage. Hutu mother, Tutsi father. And so she was rejected by both factions. Veni had no allies in the camp. Second, because she worked for us and had become a de facto member of our team, the threat to us presumably extended to her. Another emergency meeting was called.

All of us knew that Veni could not leave the camp where she was recognized as a refugee by the United Nations. Our best plan then became sponsorship and asylum application through diplomatic channels, hoping for an expedited resolution. Veni was to hunker down in the quickly dissolving camp while arrangements proceeded.

Our own exfiltration was miraculously successful. Upon return to the USA, plans were set in action to establish an asylum request for Veni. Even a request for a student visa to continue her law studies was considered. This combined with local sponsorship actually seemed like a good and true solution to the immediate problem.

These processes do not occur quickly, however, and a month passed without much movement. A letter arrived one day. Hand written. Postmarked Goma, Zaire. From one of Veni’s stay-behind team trying to carry on in the eroding camp, with no support and nothing to work with. Veni was dead. The letter was long and offered several possible causes for Veni’s demise. Maybe she got sick with any number of possible pathogens? Maybe something else happened? No answers were offered, because there were none, and if there were an answer, you wouldn’t talk about it or put it in a letter. So, the truth will never be known. Failure takes many forms in this line of work.

There are many lessons to be learned from this sad story. A few which bear considerations are the following:

1. There are many ways to meet death in dangerous places. You will not anticipate all of them.

2. Not all of us will make it back every time. Honor the memories of our brothers and sisters.

3. Care deeply for your support colleagues. You cannot work without them, nor they without you.

4. Never underestimate how your good and heroic efforts will be misunderstood and condemned.

5. Never underestimate the human inclination and capacity to believe the impossible.

6. Do not promise what you cannot, or will not, deliver.

7. Develop a strong moral compass. Take it out and shine it up now and then!

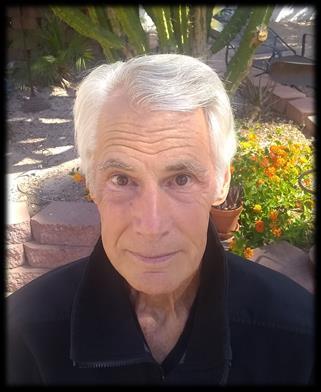

Dr. Williams is a General Practice physician, in practice for more than thirty years. His areas of operation have included North, Central and South America, Africa, the India and Nepal Himalayas and other locations. Dr. Williams served in the National Disaster Medical System of the USA as a Team Doctor and has also worked with several nongovernment organizations. He holds a Certificate of Added Qualification (CAQ) in Traveler’s Health, is a Fellow of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM) and is a lifetime member of the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine (MCoROM).

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) was formed in 1992 as an international council of councils with the mission “to promote, disseminate and advocate international implementation of evidenceinformed resuscitation and first aid, using transparent evaluation and consensus summary of scientific data.” ILCOR comprises representatives from:

• American Heart Association (AHA)

• European Resuscitation Council (ERC)

• Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC)

• Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR)

o Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC)

o New Zealand Resuscitation Council (NZRC)

• Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa (RCSA)

• Inter American Heart Foundation (IAHF)

• Resuscitation Council of Asia (RCA)

There are 6 ILCOR Task Forces:

• Basic Life Support (BLS)

• First Aid

• Advanced Life Support (ALS)

• Paediatric (basic and advanced) Life Support

• Neonatal Life Support

• Education, Implementation, and Teams (EIT)

Every five years (or so), the Consensus on Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR) update their findings. Over the past several years, the six task forces have completed 184 structured reviews – you can read their 2020 findings here. All the national resuscitation councils are in the process or have released updates to their national guidelines.

Nicole Foster BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM, FAWM CoROM FacultyIt is important to understand that ILCOR reviews the evidence and provides updates to best practice. Based on recommendations from the ILCOR Scientific Affairs Committee and agreement from the task forces, only systematic reviews result in new or modified treatment recommendations. It is then the prerogative of each national resuscitation council to update its practice (or not). There is always a gap from what ILCOR recommends and what the resuscitation councils implement.

When reading these treatment recommendations, you will see something like this at the end of each recommendation.

(weak recommendation, very low-certainty evidence)

What does this mean?

ILCOR task forces complete systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and evidence updates and rates the quality of the evidence using GRADE. GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) is the most widely used framework for developing and grading evidence summaries and provides a systematic approach for making clinical practice recommendations. The quality of this evidence (also known as the certainty of evidence) from the reviews are given one of four levels - very low, low, moderate, and high. Each level is related to how close the true effect of the outcome is to the estimated effect of the outcome of the study – as described in the table below:

Evidence gathered from randomised controlled trials is considered higher quality and, because of residual confounding (any bias that remains after controlling confounding in the design or analysis of a study), evidence that includes observational data is considered low quality. The certainty in the evidence can either increase or decrease by one or two levels, depending on certain factors. Certainty can be decreased by risk of bias (risks of systematic errors), imprecision (risks of random errors), inconsistency (when different studies show inconsistent effects), indirectness (comparison differs between the interventions, the population, and outcomes of studies), and publication bias (making inferences about missing evidence).

Confidence in the certainty of evidence can be increased if the extent of the effect creates large or very large difference – where the effect is at least greater than a small, estimated effect. Increased certainty can also occur when there is a clear cause-effect relationship, shown by a dose-response gradient or if any residual confounding decreases the extent of the effect.

Recommendations are inherently subjective (by the responsible task force) and are classed by strength (strong or weak), and in favour or against an intervention. Strong recommendations indicate that the majority of informed people would choose that intervention. Weak recommendations occur when there is variation in the decision or intervention, and when there is a low level of certainty in the evidence.

Regardless of which (or how many!) resuscitation council guidelines you are following as a health professional - the evidence all comes from ILCOR.

BMJ – Best Practice. What is GRADE? https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-isgrade/

Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;353:i2016.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;353:i2089.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2008;336(7652):1049-51.

Nicole Foster teaches on the classroom modules in Pretty Bay, Malta. She is a critical care paramedic with a masters in public health and tropical medicine and works as an exploration paramedic in remote Australia.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

While providing medical coverage for an NGO, an Iraqi security guard presents to your clinic with extensive redness, superficial swelling and blisters across his right buttock. He states he sat on some ground that was damp about 24 hours ago. He got up when he realized the wet ground had seeped through his pants. About an hour later he noted burring pain across his right buttock. He states the area had been previously mortared by ISIS.

Review of Systems: He has no systemic complaints, nor fever, facial swelling, conjunctivitis, or SOB.

Physical Examination: Completely normal vital signs with what appears to be over 4% body surface area (BSA) partial thickness burn across his right buttock. No skin involvement elsewhere.

Differential Diagnosis: Thermal burn, contact dermatitis, or chemical warfare vesicant exposure (mustard agent).

The patient would have been aware if he experienced a thermal burn. Contact dermatitis can occur when the skin reacts to an irritant, but typically doesn’t develop larger blisters or bulla. Sulfur mustard agent has been used by ISIS in Iraq.

Diagnosis: Likely sulfur mustard exposure.

Treatment: Supportive care similar to that for any thermal burn. Mustard agent burns are not as deep as thermal burns and subsequently don’t require as much IV fluid for resuscitation. If no secondary infection, he will completely recover without any scarring in a few weeks.

Sulfur mustard is a chemical warfare agent first used by the Germans at Ypres in 1918. As a liquid, its color can range from dark yellow to black depending on purity. The vapor is heavier than air and will collect / persist in low laying areas. The vapor is often described as having an odor like garlic, onions, mustard, or an “industrial” smell. It was felt to be responsible for 70% of all WWI chemical warfare casualties.

Sulfur mustard is an alkylating agent that binds to cellular DNA resulting in cell death. Onset of symptoms occur within one to several hours depending on concentration of substance exposure. Overall mortality is about 5%.

Mustard gas’s benefit on the battlefield was because it causes damage to intact skin, gas masks alone weren’t sufficient protection. If inhaled, it can cause central airway damage, essentially a respiratory “burn”, laryngeal spasm, airway obstruction and resultant death. Secondary bacterial pneumonia can occur. COPD can be a late term effect in survivors. Treatment of respiratory exposures are supportive.

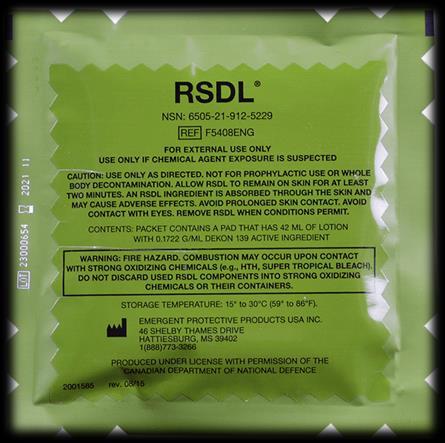

Even large surface skin exposures (>20% BSA) can be fatal. If exposed skin is decontaminated within two minutes, there is no pathologic effect. If not removed until five minutes, 50% damage, and by 15 minutes, 90% damage will occur. Less significant exposures can cause mucus membrane irritation, conjunctivitis, and temporary blindness.

Though some say the fluid in the “mustard” blisters contains residual mustard agent, the US DOD has tested this, and it does not, nor is it a source of secondary contamination. However, with the persistent nature of mustard agents, it is worthwhile to always decontaminate the patient’s skin, even hours later, as often some agent remains. Use of Reactive Skin Decontamination Lotion would be the decontamination substance of choice and has good efficacy against mustard agents. 0.5% bleach and simple soap and water would be second choices. Traditionally, Fuller’s earth, a clay soil, was used to physically remove the oily agent from contaminated skin.

Reference: Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare, 2008, available online at: https://ckapfwstor001.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/pfw-images/borden/chemwarfare/FM1.pdf

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former US Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

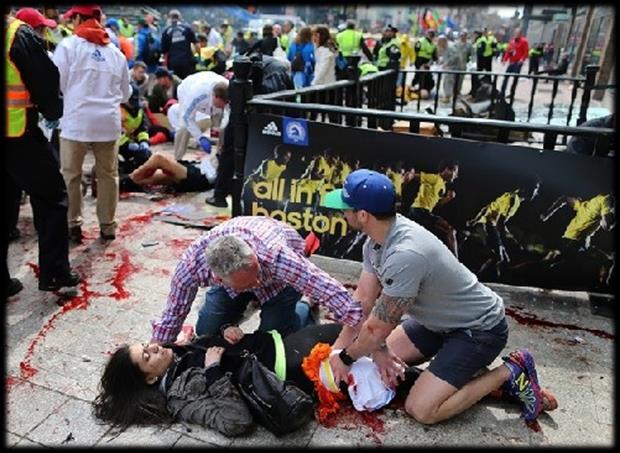

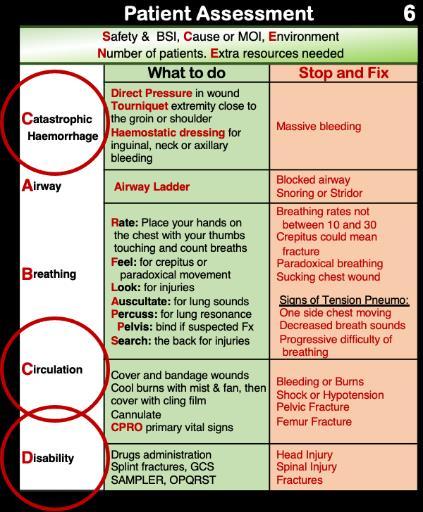

During a mass casualty event such as the bombing at the Boston Marathon, even well-equipped medical responders can quickly run out of medical equipment. It is important that healthcare professionals know how to improvise basic medical equipment needed during such events.

281 people were injured at the Boston attack; three were immediate fatalities whilst 66% suffered lower extremity soft tissue injuries. 31 additional casualties could have died from exsanguination if treatment was not immediately provided. 26 of those casualties were given tourniquets and most of those tourniquets were improvised (Gates et al, 2017).

While assessing the casualty, injuries should be addressed at “big C” (catastrophic haemorrhage), “little C” (moderate bleeding) and at “D” (disability, at which point we address fractures). When I was working on the ambulances in Seattle, we carried commercial bandages, tourniquets and slings to address these injuries. However, we only carried enough for one or two calls before we had to return to base (RTB) for resupplies. When working in remote, austere and resource-limited environments (or during a mass casualty event) we may not have the option to RTB for more supplies. As remote healthcare professionals, we need to be better than this and have the ability to quickly make tourniquets, bandages and slings in order to meet any major traumatic event.

McCarty et al (2019) compared the application of commercial tourniquets (the CAT tourniquet in this case) with improvised tourniquets. They found that only 32% of non-medical responders were able to correctly apply an improvised tourniquet compared to 92% correct usage of the CAT. Failure to properly improvise a medical device can be dangerous and can even cause more harm in many cases. It is imperative that healthcare professional practice improvised tourniquets.

You can create an improvised tourniquet by cutting up a shirt, pants, sheet or other clothing options into 2m strips that are at least 10cm wide. When we teach this at the College, we make sure that the length is equal to their outstretched arms holding the cloth with both hands as far apart as possible. This will be close to 2m. Then, when they cut the cloth, they make sure that at no time is the width of the bandage narrower than the palm of your hand. Using this bandage, you can place it just below the shoulder or just below the groin. Find the halfway point in the bandage and place that on the casualty with two 1m length ends. Start wrapping the bandage around the appendage making sure that you are keeping the bandage at least 10cm wide. You don’t want to bunch up the bandage. It must be kept wide to increase the surface area of the tourniquet. Then, find a windlass and tie it into a knot. Start twisting. Make sure that you don’t pinch the skin as you twist. Keep twisting until the pulse can no longer be felt. Give it another couple twists after that.

According to the McCarthy study, most applied tourniquets are not twisted tightly enough. Don’t make that mistake here. Make sure you have a proper tourniquet. Document the time on the casualty and continue with your assessments and treatments.

We discussed how to make improvised bandages in the paragraph above. You need a bandage in order to improvise a tourniquet. In a mass casualty event, you will need a lot more bandages than you will need tourniquets. There should be someone giving directions to non-medical personnel to make as many bandages as they can.

Once you have sorted the catastrophic haemorrhage and the minor bleeding with your improvised bandages, it is time to start creating splints and slings to treat all of the Disability injuries such as broken bones. You can create triangular bandages by cutting open tee shirts or finding bed sheets. Cut them into triangles about the height of your fingertips to your elbow. Alternatively, you can use one of the commercial cravats that you have and use that as a form to cut around.

Resources

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5531449/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6659166/

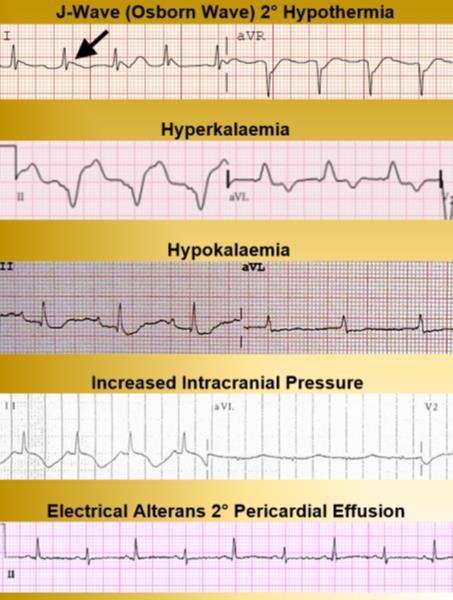

One of your field EMTs sends you an ECG strip for rhythm identification but the satellite uplink is interrupted during the transmission.

You identify this partial strip as:

A. Junctional tachycardia

B. Ventricular tachycardia

C. Supraventricular tachycardia

D. Accelerated junctional rhythm

As you are preparing to ascend from Everest Base Camp, one of the Sherpa porters assigned to your climbing team goes into cardiogenic shock. Your entire stock of injectable drugs was frozen solid during last night’s storm but the physician from a nearby Chinese expedition team gives you two of her bags of dopamine, which are packaged as 450mg in 250mL and 900mg in 500mL. Using a 60 drop/mL giving set, at what rate should you infuse your 60kg patient with dopamine to achieve a dose of 5mcg/kg/minute?

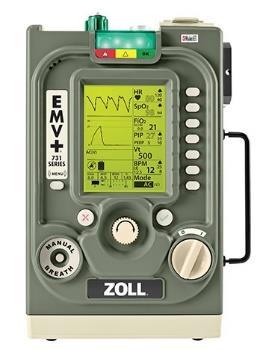

While running a remote clinic in Burkina Faso you assume care for a patient suffering from late-stage African trypanosomiasis. The 70kg patient has a GCS of 5 with poor vital signs so you decide to intubate and ventilate him with your Zoll EMV ventilator, set to the following parameters: Rate 12, VT 500mL, FiO2 21%, and a PEEP of 5 cmH20. Your clinic contains no supplemental oxygen, and the patient’s SpO2 reading is 82%. Which of the following settings on your ventilator should you adjust first to correct your patient’s oxygenation?

A. Ventilation rate

B. Tidal volume (VT)

C. Fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)

D. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

Answers will appear in the Summer 2021 Compass

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: left bundle branch, based on left axis deviation

Clinical calculation: 20 drops/minute

Clinical case: diphenhydramine

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Spring 2021.

PMID: 33721304

Cook RK, et al.

This study provides evidence that sterilization is possible with off-the-shelf pressure cookers. Though lacking U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, the use of this commercially available pressure cooker [Presto® 4quart] may provide a method of sterilization requiring minimal resources from providers working in expeditionary environments.

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine

February 7, 2020.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2019.11.003

Bennett, et al.

EAH [exercise-associated hyponatremia] has a complex pathogenesis and multifactorial etiology. The primary mechanism leading to the majority of EAH cases is overhydration of hypotonic fluids, likely in combination with nonosmotic stimulation of arginine vasopressin secretion. In the majority of cases, EAH is asymptomatic; however, it can be insidious, debilitating, and in rare cases present with severe symptoms and potentially devastating outcomes.

Preventing EAH is the key factor in protecting participants in endurance events and other wilderness recreation activities. Currently, there is no single hydration recommendation that fits all individuals for fluid and salt consumption during all exercise scenarios…

Cell

March 4, 2021.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.051

Desai P, et al.

West Nile virus is an enveloped positivesense single-stranded RNA flavivirus. It has an icosahedral capsid symmetry, is usually transmitted via the bite of Culex genus mosquitoes, and exhibits neurotropism.

Although enteric helminth infections modulate immunity to mucosal pathogens, their effects on systemic microbes remain less established. Here, we observe increased mortality in mice coinfected with the enteric helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri (Hpb) and West Nile virus (WNV). This enhanced susceptibility is associated with altered gut morphology and transit, translocation of commensal bacteria, impaired WNV-specific T cell responses, and increased virus infection in the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system. These outcomes were due to type 2 immune skewing, because coinfection in Stat6-/- mice rescues mortality, treatment of helminth-free WNV-infected mice with interleukin (IL)-4 mirrors coinfection, and IL-4 receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells mediates the susceptibility phenotypes. Moreover, tuft cell-deficient mice show improved outcomes with coinfection, whereas treatment of helminth-free mice with tuft cellderived cytokine IL-25 or ligand succinate worsens WNV disease. Thus, helminth activation of tuft cell-IL-4-receptor circuits in the gut exacerbates infection and disease of a neurotropic flavivirus.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine Spring 2021.

PMID: 33721301

Blakeman T, et al.

Resuscitation of the critically ill or injured is a significant and complex task in any setting, often complicated by environmental influences. Hypothermia is one of the components of the “Triad of Death” in trauma patients. Devices for warming IV fluids in the austere environment must be small and portable, able to operate on battery power, warm IV fluids to normal body temperature (37°C), and perform under various conditions, including at altitude. The authors evaluated four portable fluid warmers that are currently fielded or have potential for use in military environments.

by Edward R. Tufte Sixteenth printing, September 2018

by Edward R. Tufte Sixteenth printing, September 2018

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis

The effective conveyance of information is at the core of successful education. While the presentation of the latest best-practice medicine concepts is an undisputable foundation of medical education, educators cannot rely solely on the strength of the curriculum to ensure their students are better practitioners at the conclusion of the training.

There are basic strategies an educator can employ to improve the impact of a presentation, such as gaining the audience’s interest, building rapport, showing vulnerability1, making deliberate use of repetition, creating an interactive learning environment in which it is okay to make mistakes, and so forth. More refined presentation tactics include placing text above images instead of beneath them, eschewing bullet points2, and engaging as many of the brain’s afferent pathways as possible (auditory/visual/kinesthetic/tactile) for maximizing long-term retention of knowledge and skills.

Edward R. Tufte elevates the visual elements of the transmission of information to their ultimate level in Envisioning Information, a book lauded by Sci-Tech Book News as a “Brilliant work on the best means of displaying information.”

Using examples as far-flung as the writings of Galileo, the geographic distribution of the birthplaces of Chinese poets, and a 1933 Czechoslovakia Air Transport Company flight map, Tufte weaves a tapestry of effective visual communication techniques that have stood the test of time.

From the introduction – “To envision information – and what bright and splendid visions can result – is to work at the intersection of image, word, number, art. The instruments are those of writing and typography, of managing large data sets and statistical analysis, of line and layout and color. And the standards of quality are those derived from visual principles that tell us how to put the right mark in the right place.”

Edward Tufte has written four books on visual reasoning: Beautiful Evidence, Visual Explanations, Envisioning Information, and The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. He is Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Statistics, and Computer Science at Yale University, and also served as Professor of Public Affairs at Princeton University.

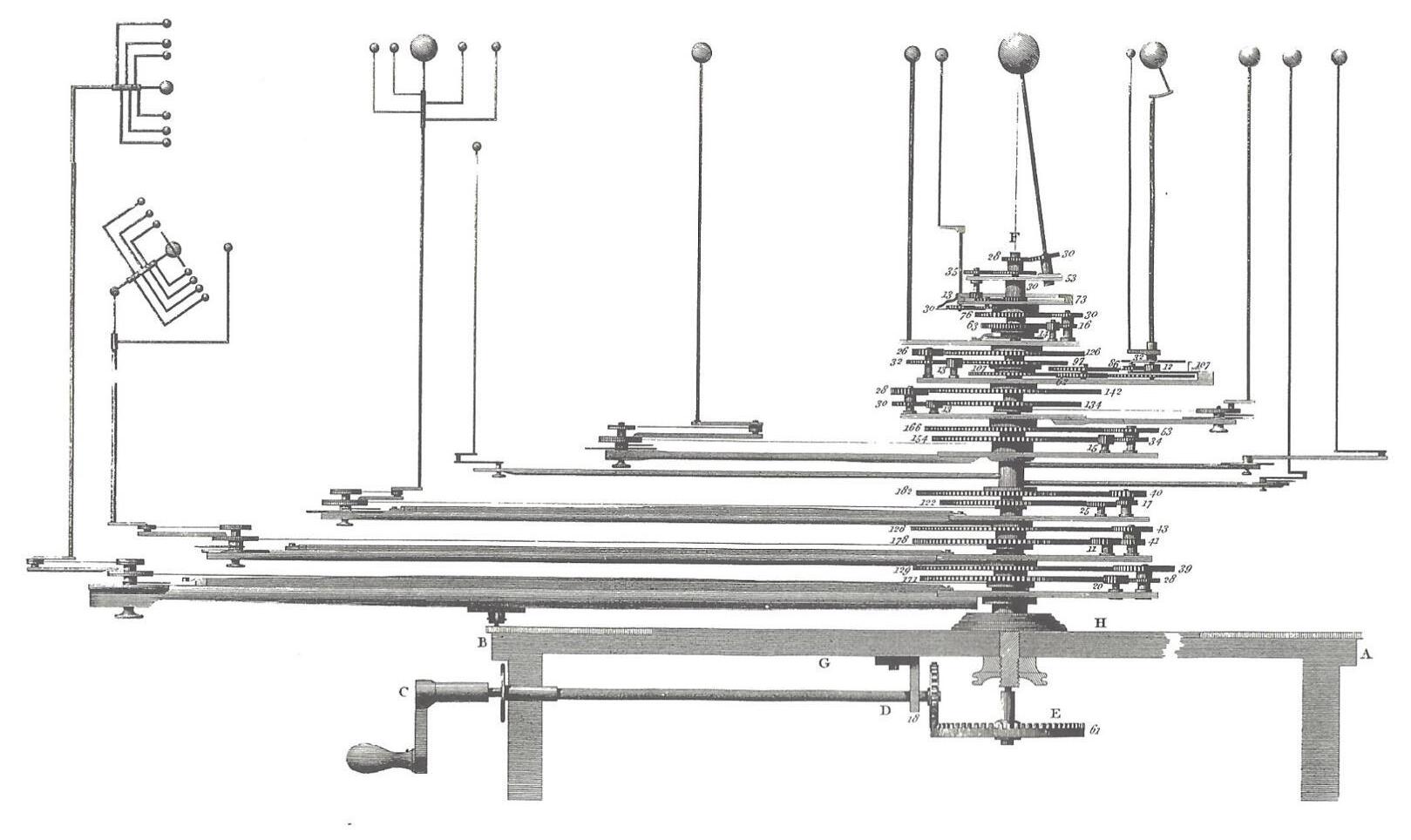

“Narratives of the universe were impressively cranked up in orreries, simulations of our solar system (as known in 1800), with planets and their satellites rotating and orbiting. Although a triumph of gear ratios, the machines did commit a grave sin of information design – Pridefully Obvious Presentation – by directing attention more toward miraculous contraptionary display than to planetary motion.”

William Pearson, “Planetary Machines,” in Abraham Rees, ed., The Cyclopedia; or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, Plates, Vol. IV (London, 1820), plate XI; and Henry C. King with John R. Millburn, Geared to the Stars: The Evolution of Planetariums, Orreries, and Astronomical Clocks (Toronto, 1978).

“The space-time grid has a natural universality, with nearly boundless subtleties and extensions. Organized like the graphical timetable, this unusual arrangement below simultaneously describes two dimensions, space and time, on the horizontal, while maintaining vertical spatial dimension. A complete year-long life cycle of Popillia japonica Newman (the Japanese beetle) is shown, transparently, in a smooth escape from flatland brought about by doubling up variables along the horizontal.”

- Envisioning Information

“The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC achieves its visual and emotional strength by means of micro/macro design. From a distance the entire collection of names of 58,000 dead soldiers arrayed on the black granite yields a visual measure of what 58,000 means, as the letters of each name blur into a gray shape, cumulating to the final toll. When a viewer approaches, these shapes resolve into individual names. Some of the living seek the name of a particular soldier in a personal micro-reading; more than a few visitors here touch the etched, textured names.”

“We focus on the tragic information; absent are the big porticoes, steps and stairs, and other marble paraphernalia usually attached to grand official monuments. Walking on a slight grade downward (approaching from either side), our first close reading is of panels no higher than a few names. But looking forward, the visitor sees names of the dead rising higher and higher, a statistical blur of marks in the distance with microdetail at hand.”

- Envisioning Information

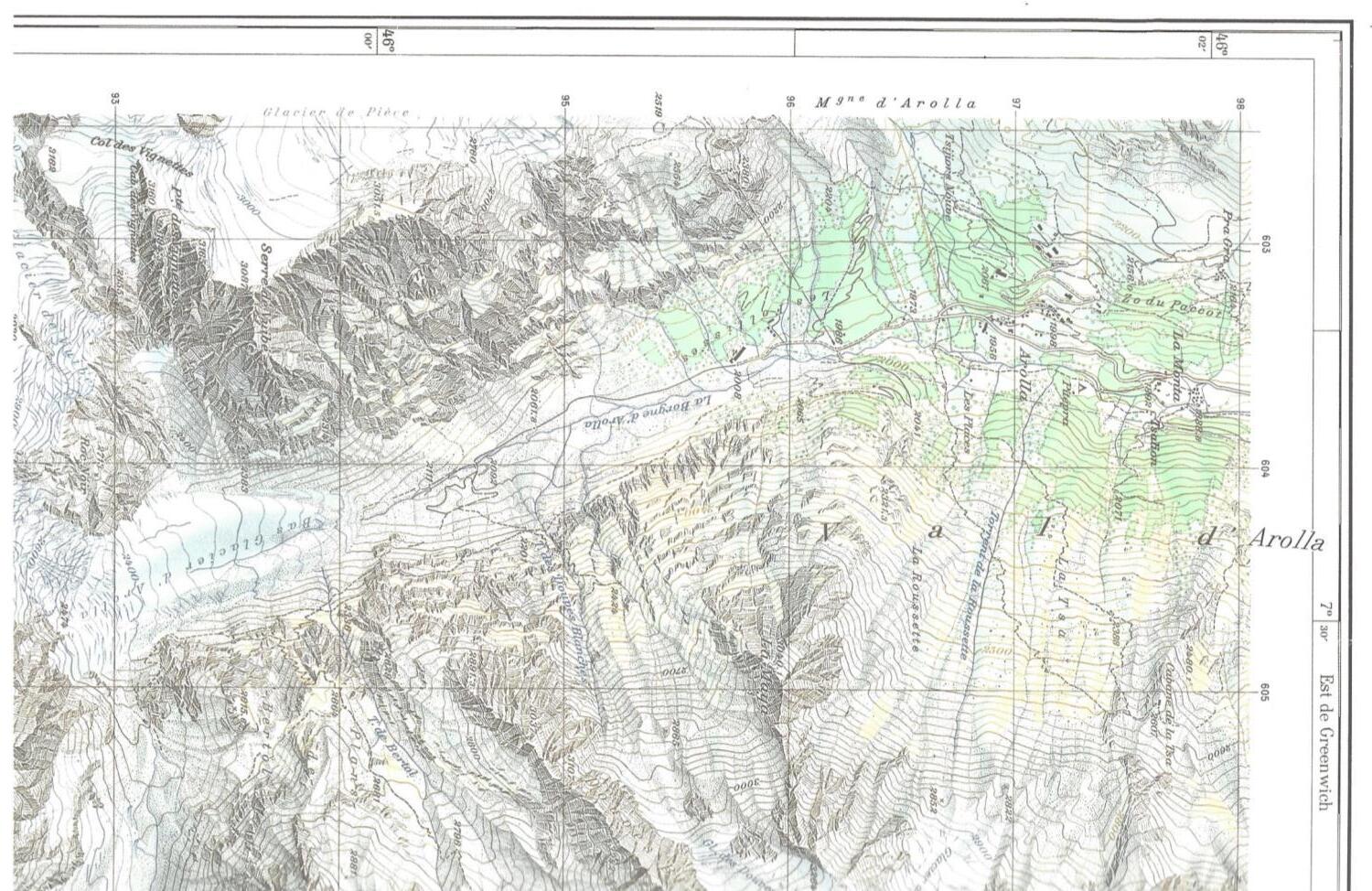

“At work in this fine Swiss mountain map are the fundamental uses of color in information design: to label (color as noun), to measure (color as quantity), to represent or imitate reality (color as representation), and to enliven or decorate (color as beauty). Here color labels by distinguishing water from stone and glacier from field, measures by indicating altitude with contour and rate of change by darkening, imitates reality with river blues and shadow hachures, and visually enlivens the topography quite beyond what could be done in black and white alone.

Strategies for how color can serve information are set out in Eduard Imhof’s classic Cartographic Relief Presentation, which describes the design practices for the Swiss maps. The first two principles seek to minimize color damage:

First rule: Pure, bright, or very strong colors have loud, unbearable effects when they stand unrelieved over large areas adjacent to each other, but extraordinary effects can be achieved when they are sparingly on or between dull background tones.

Second rule: The placing of light, bright colors mixed with white next to each other usually produces unpleasant results, especially if the colors are used for large areas.

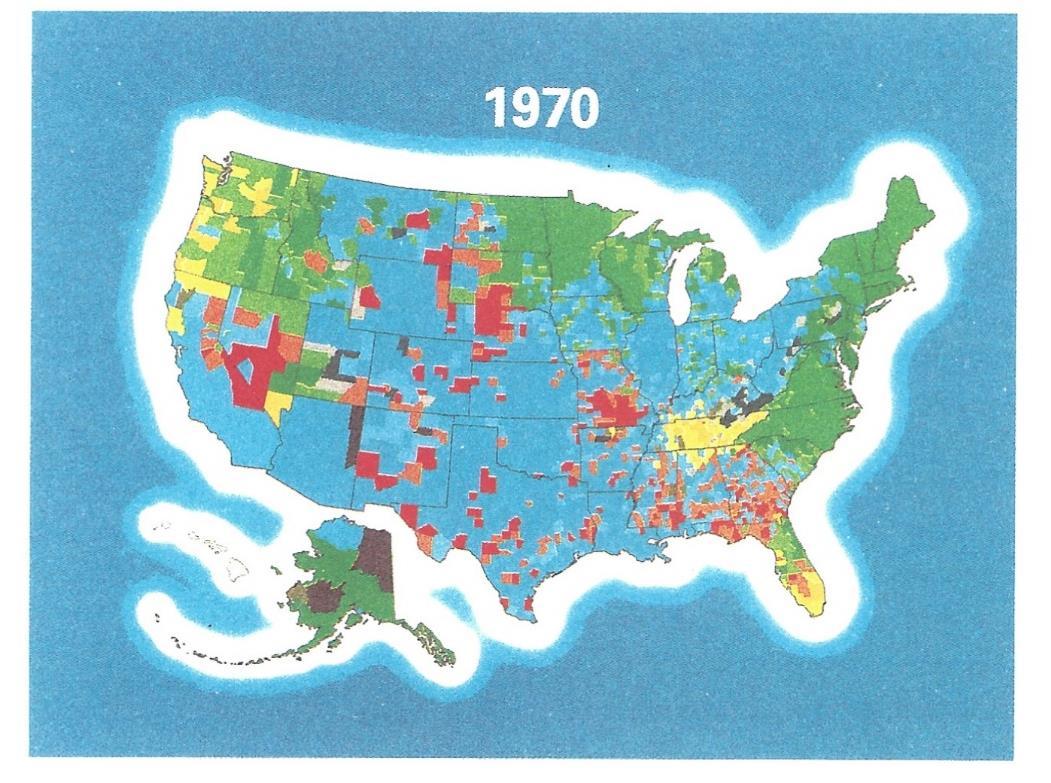

…violation of this counsel yields the exuberantly bad example below. All this strong color, especially the surrounding blue, generates a strange puffy white band, making it the map’s dominant visual statement, with some alarming shapes at lower left.”

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

NORWAY

TTEMS (closed course) 6-24 September

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON

Suturing Fundamentals 21 August

NORTH CAROLINA

SOMSA Conference 28 June – 2 July

Tactical Medicine Review (O’Kelly)

2021 Tropical Medicine Updates (Jarvis)

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

Higher Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Cert Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene (in accreditation process)

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Degree Courses

MALTA

PARSIC 16-17 August

ITLS 18 August

Prehospital

skills course 19 August

RPP104 30 Aug – 18 Sept

RAMS 30 Nov – 4 Dec

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine

August dates TBD

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

MSc Austere Critical Care (in accreditation process)

MSc Leadership in Healthcare (in accreditation process)

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitudes

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

iCARE Intensive Care for Remote and Austere Environments

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert

Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104

Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (classroom learning)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E, MA FAWM, DipPara, CCP-C, TP-C CoROM Executive Dean

Jason Jarvis 18D, BSc, NREMT-Paramedic CoROM Tropical Medicine Lead

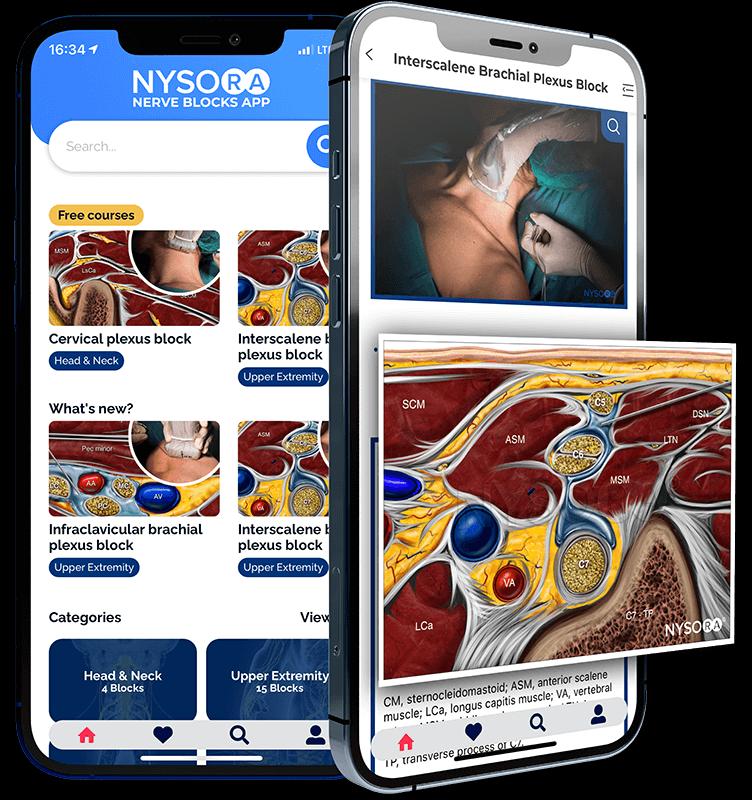

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

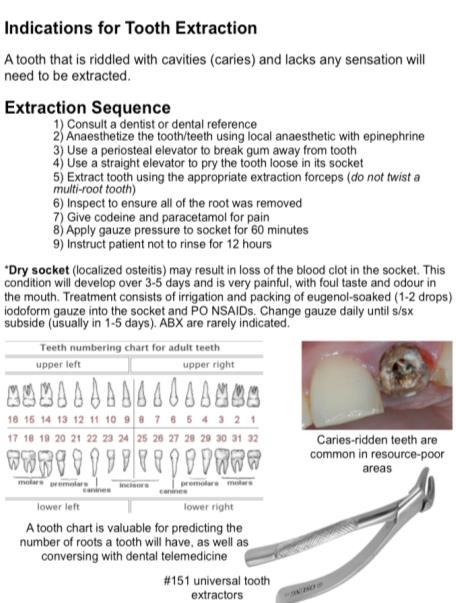

Dentistry

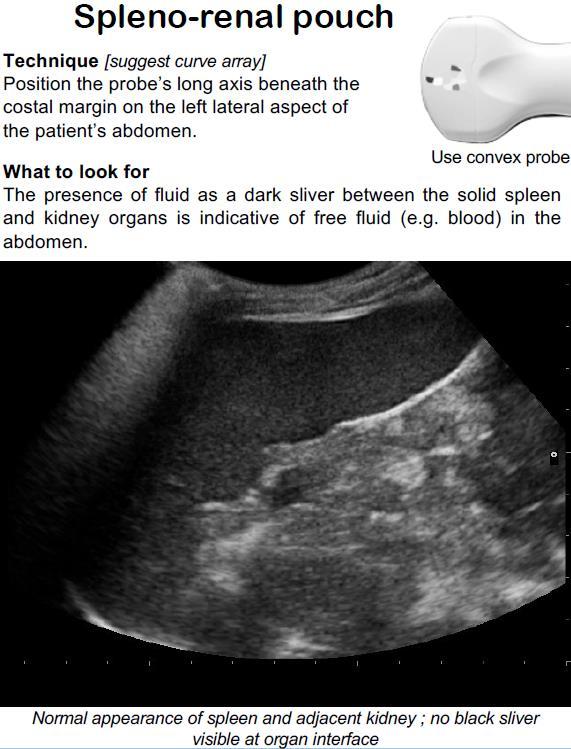

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

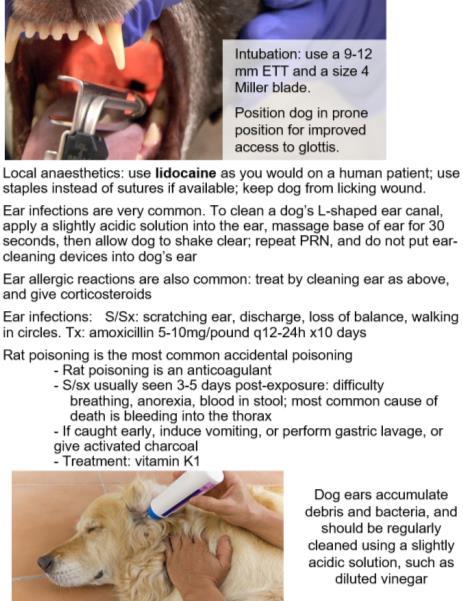

Canine medicine

…and much more!