Summer 2020

Theofficialnewsletterofthe CollegeofRemoteandOffshoreMedicine Foundation

Summer 2020

Theofficialnewsletterofthe CollegeofRemoteandOffshoreMedicine Foundation

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntaryAcademic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

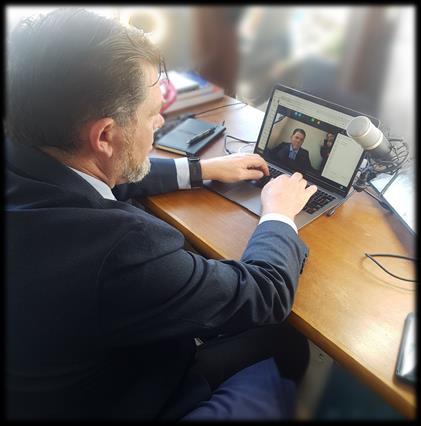

The College has been busy over this spring semester. The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc around the world and also in our ability to run classroom courses. The Maltese government closed all of its universities and colleges in March which forced our Remote Paramedic Higher Diploma students out of the classroom and back to their homes.

We were not going to let a pandemic stop us from running excellent medical training. We converted the last week of the paramedic course into an online and interactive webinar. We had Nicole Foster teaching from Perth, Jason Jarvis teaching from Seattle, Tim Cranton teaching from Czechia, Dr Hannah Evans teaching from the United Kingdom, Neil Coleman teaching from Ireland and I taught from Germany.

The College also converted the Tropical Travel and Expedition Medical Skills course into the online interactive teaching format. In addition, theAdvanced TTEMS was taught completely online. We had to fill quite a few hours that are normally allotted to a prolonged field care scenario so extra lessons were added to replace those extra hours.

The College has not slowed down since. We continue to offer live and interactive webinar-based courses several times each week for the remainder of the spring semester and will be running them sporadically throughout the summer break.

While the College has been on partial closure due to COVID-19, most of our faculty are busy working in the direct line of fire on the front lines of the fight. For example, Dr. Francis Sakita is running the Emergency Department at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre in Northern Tanzania. The College continues to support the efforts of KCMC as best as we can. Here is one of their faculty wearing our scrubs as he treats the local casualties:

As this pandemic runs its course, we wish for the safety and health of all the frontline medical staff throughout the world who are putting their lives on the line for the people of the world.

Screenshots of CoROM’s livestreamed webinar classes

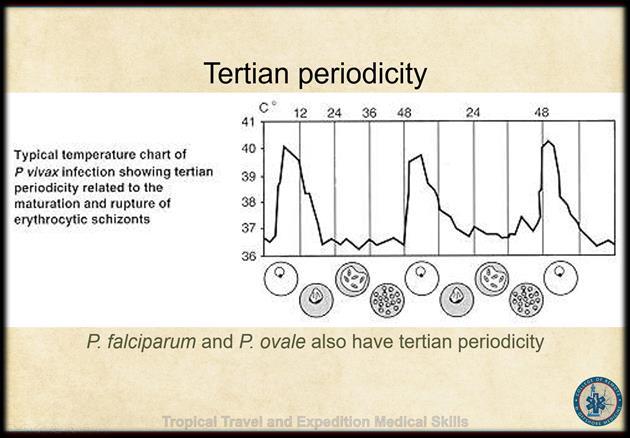

Introduction to Tropical Medicine

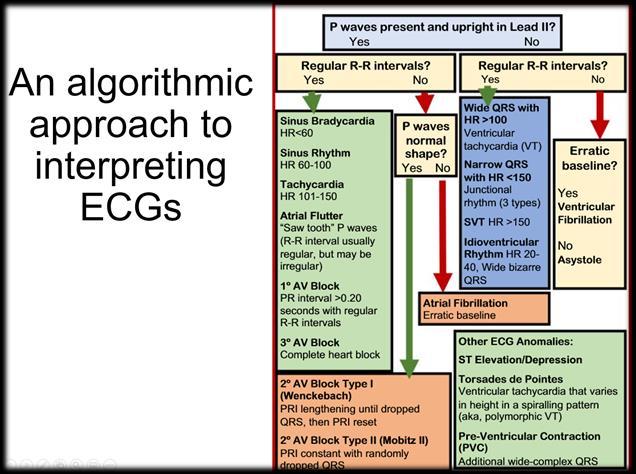

ECG interpretation

Case studies

Malaria

Ectoparasites & Other Arthropods

Case studies

Most in-house courses are postponed until the end of COVID-19 travel restrictions

MALTA

All

Suturing Fundamentals

21 July 7 October

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitudes

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

REMT Remote Emergency Medical Technician

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org. Please address newsletter correspondence to editor@corom.org.

Nine years ago, my close friend Chris was tragically killed in a motorbike accident and this was the catalyst for me to begin my medical training as I wished I could have done something to save his life. I started off training as a Wilderness Emergency Medical Technician and spent some time in Guatemala City working alongside the Bomberos, who are the local firefighter/paramedics. I completed my Remote Paramedic course in Malta with Aehbric and his team. At one stage in that training I certainly got my money’s worth being the only student with three instructors. I certainly had nowhere to hide with Aehbric’s daily morning warm-up sessions - you have all been there!

After the course, I returned to work as a UKArmed Police Officer within SO19 Specialist Firearms Command, Metropolitan Police Service in London. Within days of being back, I was putting my new skills to use during live firearms operations, dealing with gunshot and stabbing victims. The first of these was a male with multiple gunshot wounds who had been shot at close range through his front door.

My clinical placements were at The Royal London Hospital and The Tambo Memorial Hospital in Johannesburg, mainly working in theA&E Departments. These experiences were worlds apart, but at least in Johannesburg I didn’t confuse my police colleagues when they arrived with a shooting victim to find me wearing a nurse’s uniform.

After 14 years as a Firearms Officer in London and being involved in the terror attacks, I decided to move from the ‘big smoke’to the beautiful county of North Yorkshire, to retire…..I wish!

It is here that I qualified as a National Firearms Instructor, teaching weapons handling and tactics; this new role provides me with a great opportunity to train my colleagues.

I am currently the North Yorkshire Police Lead Instructor for several disciplines including Tactical Medicine (teaching Police Officers to provide medical assistance in hostile environments), Armed Response (teaching Police Officers weapon handling skills of both lethal and non-lethal weapons, and the tactics to deal with a variety of situations) and the use of Pyrotechnic Devices. I have never worked so hard or kicked away so much unsecured equipment (found to be an effective teaching method after I learnt it the hard way….hey Aehbric?)

I want to make North Yorkshire a centre of excellence for Police Firearms Tactical Medicine, and I hope to go back to Malta for the Higher Diploma of Remote Practice Paramedic training soon.

Having spent time training in Emergency Medicine, Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, Hannah left the hospital environment to pursue a career as a portfolio GP and currently works as an out-of-hours GP in Aberdeen, Scotland.

She has a keen interest in wilderness and humanitarian medicine, deploying to help in humanitarian crises whenever time allows. She has provided medical cover and has led medical teams for endurance and professional sporting events around the UK and the world for a decade.

Hannah Evans MBChB, DTMH, MSc Global Health and Infectious Disease, MRCGP, FAWM

Hannah Evans MBChB, DTMH, MSc Global Health and Infectious Disease, MRCGP, FAWM

Hannah is an active Expedition and Wilderness Medicine, ALS and AWLS instructor and is an online tutor for postgraduate wilderness medicine diploma and MSc programmes in the UK. She gained her Fellowship of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM) in 2014 and was a staff writer for Adventure Medic for several years and published on expedition and humanitarian medicine. She spends as much time outdoors or under water as possible having recently achieved her Master Scuba Diver qualification.

What aspect of CoROM motivated you to join the College?

I taught on the TTEMS course a few years ago and have had a very high regard for the educational opportunities provided by the CoROM since its inception. I love teaching as part of a multidisciplinary faculty as that’s the type of environment I find most conducive to improving my own practice and providing rich learning opportunities for delegates.

During the Coronavirus pandemic in particular, the College has impressed me by quickly adapting and pushing forward with innovative ways of teaching and learning. I enjoy being part of a community of individuals with a commitment to improving the care we provide in the remotest and most challenging environments.

I enjoy teaching about the common conditions encountered in extreme environments. Given my background, I enjoy teaching public health, expedition primary care with a little tropical medicine thrown in for good measure.

I find the focus is sometimes disproportionately on ‘worst case scenario’training and so common minor ailments are glossed over. On expeditions over the years I have found that being asked about diarrhoea or a sore throat is a far more common occurrence than major trauma requiring planned evacuation and so, having a comprehensive knowledge of these more minor ailments which we see commonly in General Practice has served me well.

Over the last few years I have developed a keen interest in the psychology and psychiatry of expedition environments and so teaching some basic mental health assessment and management strategies feels like a good investment of time. I get the most satisfaction when teaching transferable skills. Adaptations of ‘shiny hospital’practice that can be taken to the field/trip are both innovative and potentially lifesaving.

The Coronavirus pandemic has been a challenging time for most of us, yet it has provided an opportunity for diversification, and this is particularly true of the CoROM. The way we teach and learn has changed as a result of this and it is likely that many of these changes will be integrated going forward which will be exciting to see and be part of. I hope that the college will continue to be innovative at the forefront in austere environment medical training and forge further connections with great educators around the world.

My interest in global health has taken me to some remote and challenging places. In Bangladesh, whilst working in the Rohingya camps, a 5-day old baby was brought to our clinic. He was floppy, lethargic and severely dehydrated. I hadn’t seen a child that unwell for a while. Both parents were in their teens and terrified. I was lucky to be working with a great team of doctors and nurses from the US. We treated the baby for sepsis and dehydration and transferred him to the local paediatric facility. He thankfully improved and was discharged back to camp the following week. I had recently become a parent myself and so it was particularly pertinent. One of the privileges and challenges of medicine for me, is seeing patients and their families at their most vulnerable. The main lasting impact was the satisfaction of being part of a really effective team despite only knowing those I was working with for a few days.

I would probably take the Oxford Handbook of Expedition Medicine wherever I was going. It covers a very wide range of expedition health and safety considerations. For location-specific health information before a trip, I like to use the fitfortravel website (www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk) as it gives current vaccination recommendations and lists the most common threats to health by area including up-to-date malaria information. I would also recommend keeping up to date with the Practice Guidelines published in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine.

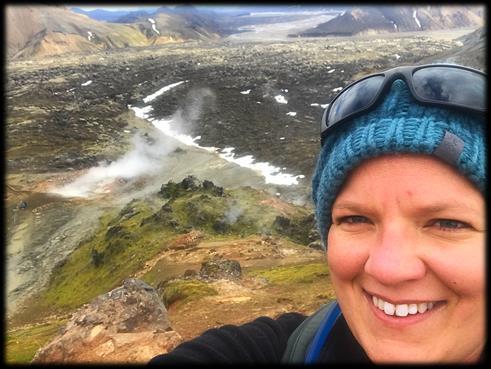

Working as an expedition doctor in Iceland on volcanic terrain

Working as an expedition doctor in Iceland on volcanic terrain

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former U.S. Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

OnApril 5th a 55-year-old male with treated hypertension presented to the emergency department for one week of dry cough, shortness of breath “while talking”, body aches, and fever to 38.5 Celsius. He stated overall, he “felt good”, but didn’t think his symptoms were improving.

He was afebrile, but diaphoretic, mildly tachycardiac (110’s) and mildly tachypneic (high 20s) on arrival. He had very minor end expiratory wheezing on auscultation and an O2 saturation of 92% on room air.

Differential for his symptoms included a viral upper respiratory infection with a reactive component, influenza as it was still present in the community and he didn’t undergo vaccination for it this season, pneumonia, and COVID-19. With his fever and body aches, noninfectious causes like congestive heart failure and pulmonary embolism seemed unlikely.

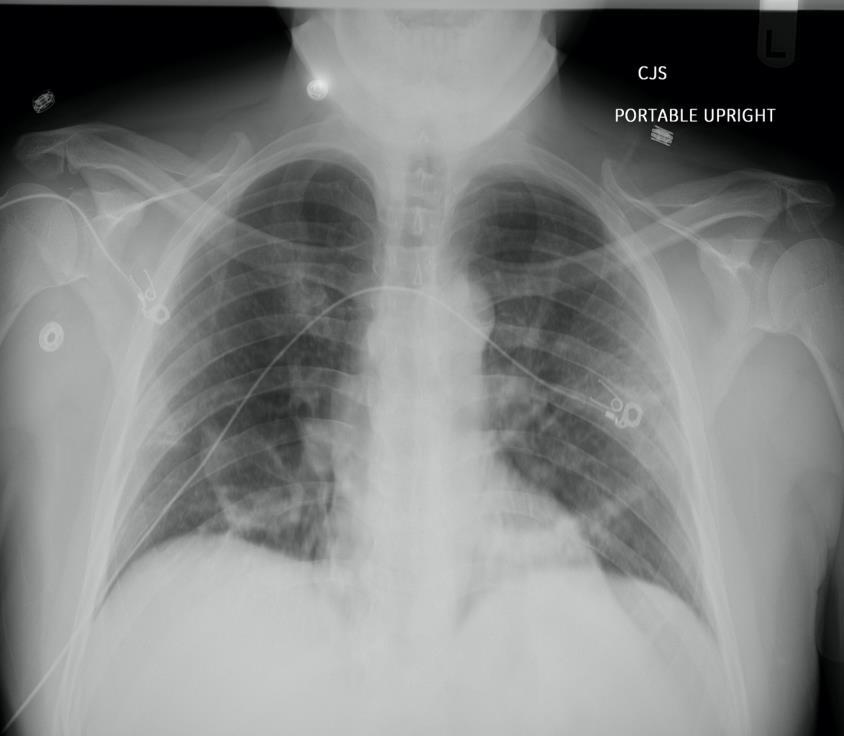

His complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and venous lactate were baseline for him. His portable chest x-ray is shown.

His chest x ray shows patchy bilateral airspace abnormalities most prominent in the right lower lobe.

Despite albuterol MDI use in the ED, his minor wheezing persisted. He became a bit more tachypneic (28 – 30), but never had O2 saturations below 90%.

Overall, it was felt that he likely had a viral pneumonia based on CXR findings. COVID-19 was presumed, but since it had limited penetration in the local community at that time and nearly 1/3 of viral appearing pneumonias on CXR ultimately have a bacterial cause he received 1 gm ceftriaxone and 500 mg azithromycin, both IV.

Because he was slowly worsening in the ED he was admitted to the hospital. During the five days of his admission he became hypoxic requiring nasal cannula oxygen, but ultimately improved. His COVID-19 testing was positive.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

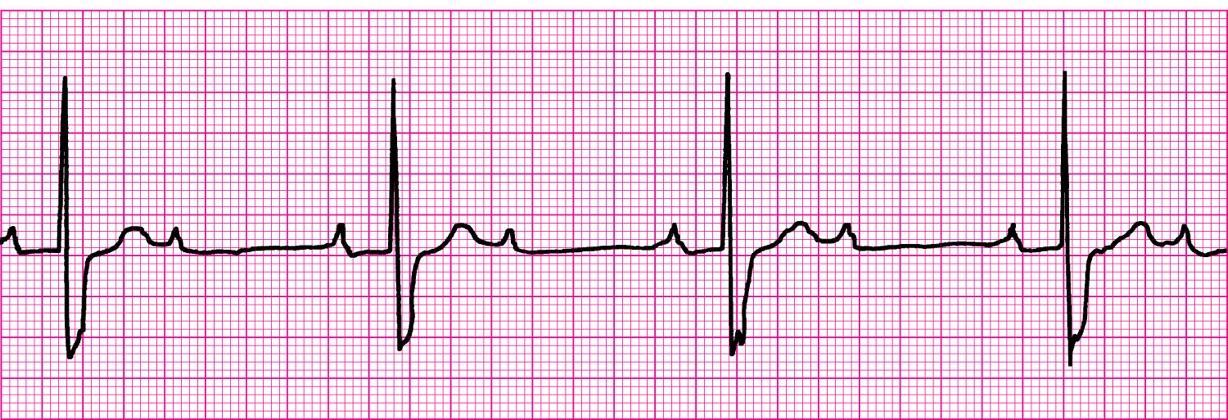

SARS-CoV-2 and its infection COVID19 are currently responsible for a global pandemic. The last four pandemics of the last 100 years were 1918 Spanish Influenza-H1N1, 1957 H2N2 Influenza, 1968 H3N2 Influenza, and 2009 H1N1 Influenza.

Based on a retrospective review of 1099 Chinese patients with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 89% had fever, 68% dry cough, and 19% dyspnea.1 Ultimately, 82% of those requiring hospitalization would require some oxygen support. Half required only nasal cannula oxygen. Unfortunately, 3% required intubation.2

Generally speaking about 20% of symptomatic adults with COVID-19 will be ill enough to require hospitalization. One quarter of those will become critically ill requiring ICU admission. Survival rates of patients requiring intubation have been between 33 to 50% and they are generally intubated for a week which can lead to a shortages of ventilators.

At the time of this publication there are currently no well-studied treatments available that have shown an improvement in mortality. Multiple different medications are being researched and used in the hopes of improving the death rate of the infection which is generally 3 to 5%. Typical seasonal flu has a 0.1% mortality per the US CDC.

1 Guan WJ, Ni ZY, et al. Clinical characteristics of corona virus disease in 2019. NEJM, 2020 FEB 28.

2Wu C, Chen X, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with Corona virus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMAInternal Med. 2020 MAR 13.

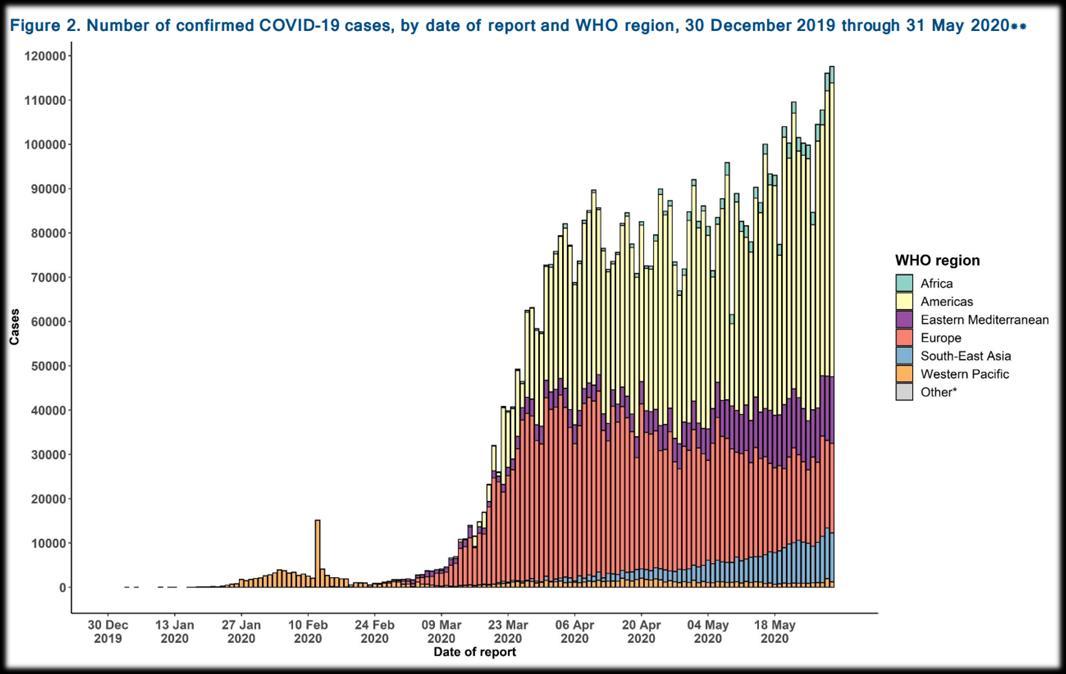

COIVD-19 continues to spread throughout the globe, and there is still so much information about this virus that is still unknown. In times where information is key, knowledge about the disease itself, how it replicates, its effect on children and adults is fluid and constantly being updated, making it difficult to contain, control and treat. The virus is at the forefront of every country’s public health initiatives and will be until it runs its course or a vaccine is developed and distributed.

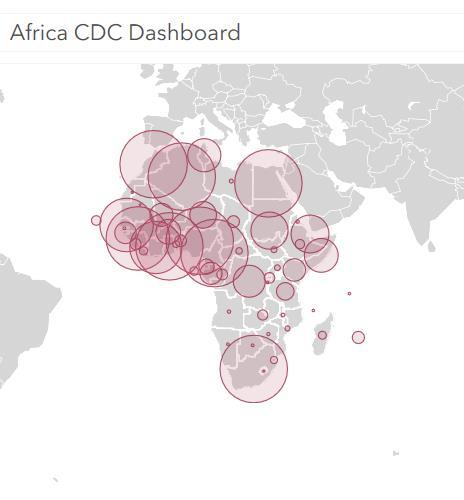

Most western countries are either on the other side of the disease curve or just peaking, but Africa is bracing itself for the first wave to hit. As of 10 May, 2020, there has been 61,165 confirmed cases of COVID-19, 2239 deaths and nearly 21,000 recoveries. The worst-affected countries include SouthAfrica, Egypt, Morocco andAlgeria. The WHO is expecting the worst – if containment measures fail - an estimated 190,000 people will die within the first year and anywhere from 29

44 million people will be infected.

The African continent watched as the first COVID-19 wave hit Asia, Europe andAmerica and was able to pre-emptively close borders, isolate and prepare their health systems – a brief respite before the storm which so far has limited the spread of COVID-19. But what happens when a pandemic hits on top of other public health emergencies? Public health emergencies and the usual acute and chronic health issues continue in countries where the health system and infrastructure are already strained or broken – what’s going to happen if containment fails and countries that don’t have the resources in the first place begin to see cases?

Long term consequences are anticipated when other public health emergencies are given the back seat to fight COVID-19 - what happens when isolation and stay at home orders restricts access to clean water, food, medication and health care? How do you isolate a sick person when there is no physical space required inside a house or refugee camp to do so? Years of progress will be lost against HIV/AIDS, TB, malaria, Ebola, measles, polio, cholera, and dengue. Expect to see increasing numbers of other diseases and expect to see an increase in case fatality rates.

As medical professionals, we are at the forefront of this pandemic. We are responsible for the health of our patients, our communities and most importantly, ourselves. The consequences of COVID-19, just like the disease itself, is still being charted. We don’t know the answer to a lot of ‘what if’questions. As healthcare professionals, we can only do the best with what we have.

COVID-19 guidance based on humanitarian standards -

https://spherestandards.org/coronavirus/Africa CDC - https://africacdc.org/covid-19/

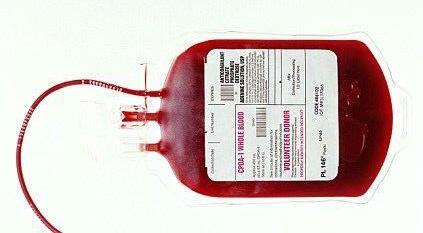

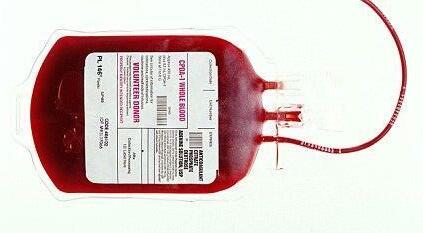

Ahealthcare practitioner working in an austere setting will naturally seek to employ as many tools in the modern medicine arsenal as can fit in his or her rucksack. When correcting blood loss in a patient suffering from hemorrhagic shock, the best option (if prepared to do so) is to replace that blood with whole blood; failing that, several other options may be available.

Alternatives to whole blood in the far-forward field setting run the gamut from freeze-dried plasma (most desirable) to sodium chloride (least desirable).

Administering whole blood in any setting is not a trivial matter and is fraught with numerous risks. Doing so in a primitive or austere clinical setting can be made even more difficult by the lack of general cleanliness, sophisticated equipment, and number of clinicians. Then there is the issue of the procurement of the blood itself. If cold-chain storage is not available (or the practitioner has run out of refrigerated blood) then the “walking blood bank” protocol may be invoked.

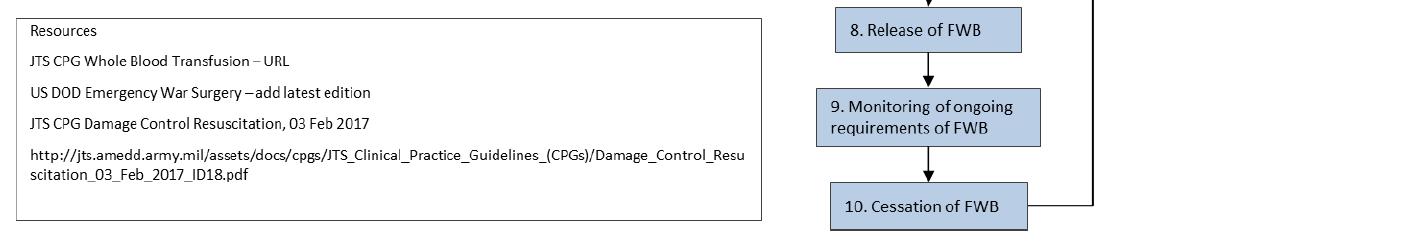

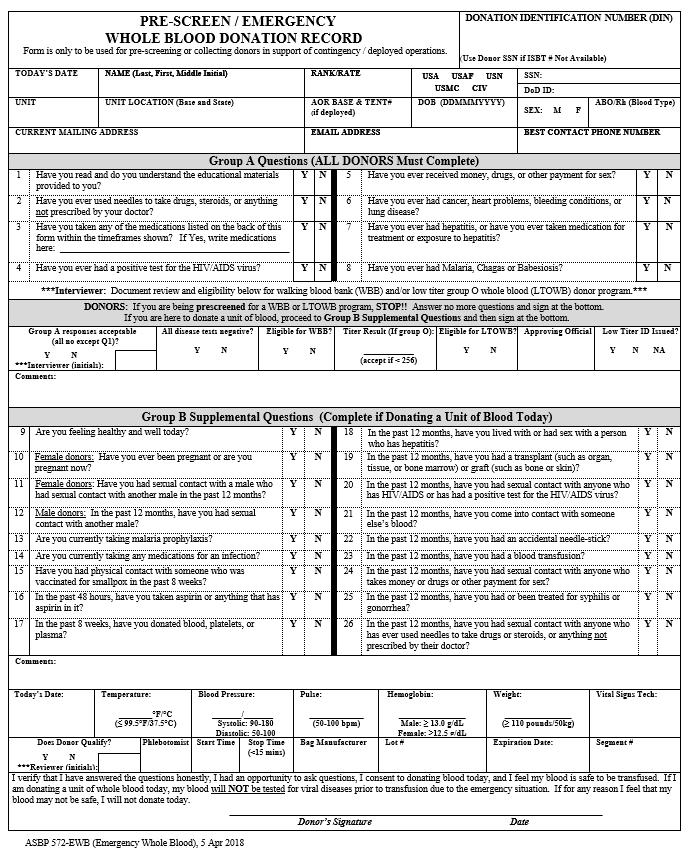

The following excerpts are from the Joint Trauma System (JTS) clinical practice guideline on how to safely harvest and administer whole blood in a field environment. For further details, please visit https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/JTS_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_(CPGs)/Whole_Blood_T ransfusion_15_May_2018_ID21.pdf

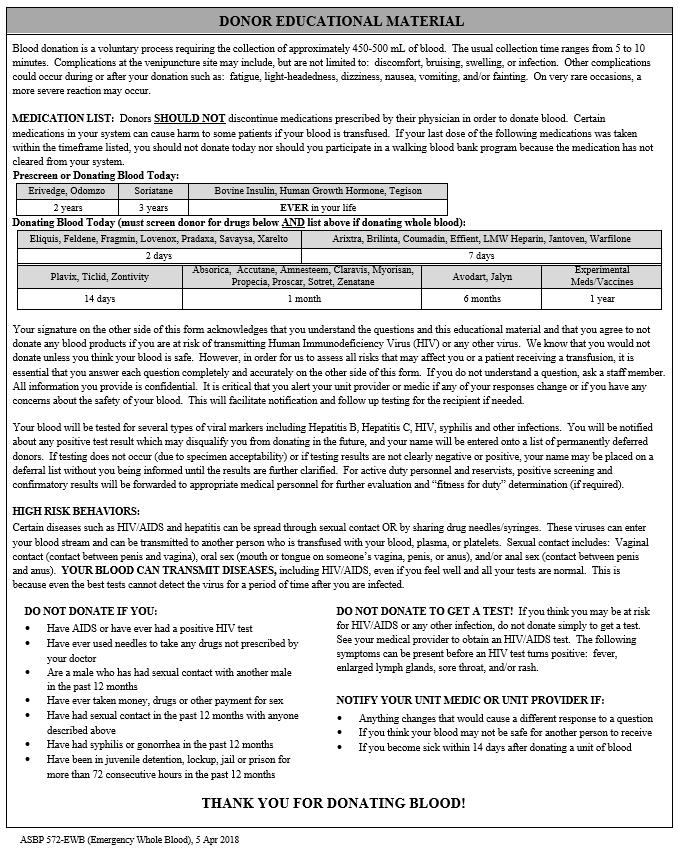

Which term best describes the following arrhythmia?

A. 1° AV block

B. Junctional rhythm

C. Mobitz II AV block

D. Complete heart block

You are assisting in a clinical trial on the therapeutic efficacy of sarilumab –an interleukin-6 inhibitor – for SARSCoV-2. You have orders to administer 200mg SC to a patient but have run out of the 200mg pre-filled syringes. The only sarilumab you have on hand are 150mg/1.14mL pre-filled syringes. How many mL should you inject?

While attending a course at the Kawthoolei Jungle School of Medicine in Burma, you see a patient who has been complaining of flea bites and painful inflammation of the inguinal lymph nodes. Using your smartphone microscope you image one of the patient’s fleas and identify it as a member of the Xenopsylla cheopis species. What is your working diagnosis at this point?

A. Tungiasis

B. Scrub typhus

C. Murine typhus

D. Bubonic plague

Medical References (Dr. Hannah Evans’ picks) Gear

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Spring 2020.

18(1). 37 – 43.

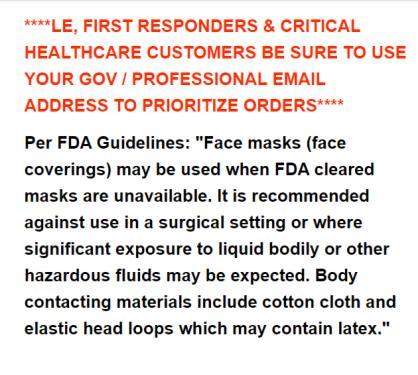

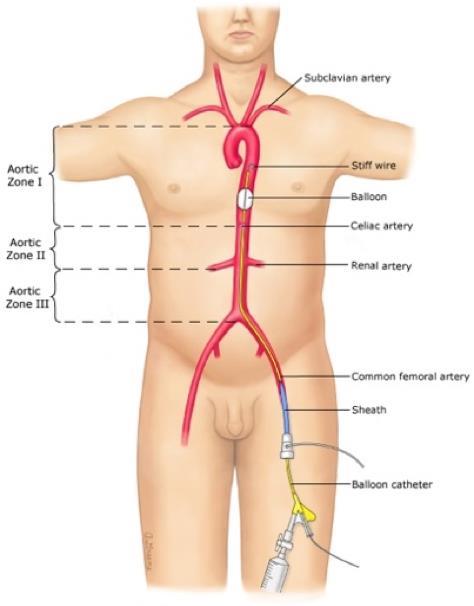

Ross,

EM, Redman, TT.There were 28 REBOAcatheter placement attempts in 14 perfused cadaver models in the nonhospital setting: eight placements in a field setting, eight placements in a static ambulance, four placements in a moving ambulance, and eight placements inflight on a UH-60 aircraft. No statistically significant differences with regard to balloon inflation time were found between the two providers, the side where the catheter was placed, or individual cadaver models. Successful placement was accomplished in 85.7% of the models. Percutaneous access was successful 53.6% of the time. The overall average time for REBOAplacement was 543 seconds (i.e., approximately 9 minutes; median, 439 seconds; 95% confidence interval [CI], 429-657) and the average placement time for percutaneous catheters was 376 seconds (i.e., 6.3 minutes; 95% CI, 311-44 seconds) versus those requiring vascular cutdown (821 seconds; 95% CI, 655-986). Importantly, the time from the decision to convert to open cutdown until REBOAplacement was 455 seconds (95% CI, 285-625).

Annals of Emergency Medicine

May 2020, Volume 75, Issue 5, pages 640-641. Shah, KH, Melville, LD.

The initial literature search yielded 370 studies.After screening of title and abstracts, 43 full texts required review, with 5 studies included for meta-analysis. There were a total of 1,038 patients; the majority of subjects were from one large emergency department (ED) study (n=757) by Driver et al and an out-of-hospital study by Heegaard et al (n=51). The remainder of subjects were from 3 preoperative studies (total N=230). Ris of bias was considered high only in the out-of-hospital study. Overall, firstattempt intubation success, intubation duration, and the esophageal intubation rates were similar between bougie and stylet groups, with RR 1.03 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.85 to 1.24), mean difference 6.01 (95% CI -0.07 to 12.09), and RR 0.59 (95% CI 0.13 to 2.59), respectively.

Lancet Infectious Diseases

March 30, 2020; excerpt from page 4.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7.

Verity, R, Okell, LC, Dorigatti, I, et al.

Onset-to-recovery data from 169 cases outside of mainland China. Red lines show the best fit (posterior mode) gamma distributions, uncorrected for epidemic growth, which are biased towards shorter durations. Blue lines show the same distributions corrected for epidemic growth. The black line (panel A) shows the posterior estimate of the onset-to-death distribution following fitting to the aggregate case data.

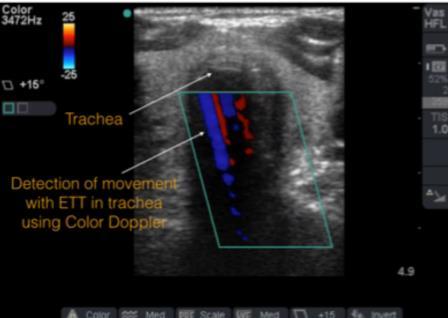

American College of Emergency Physicians

ACEP Emergency Ultrasound section.

DOI: https://www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/emergencyultrasound/news/june-2015/tips-and-tricks-airway-ultrasound/.

Alice Chao, MD, Laleh Gharahbaghian, MD.

In recent years, the use of ultrasound (US) for confirmation of endotracheal tube (ETT) placement has gained increasing popularity. Several techniques already exist to confirm endotracheal tube placement. However, every tool has its limitations, and some are not always available in the emergency department (ED). The likely reason that airway US has gained attention is the ease at which images can be obtained. Airway US for ETT confirmation is best used when the end-tidal CO2 monitor is not accurate, radiology is unavailable, the patient arrives intubated and requires airway confirmation, or the patient does not respond as expected after intubation. There are some tips and tricks that can assist in obtaining the best view.

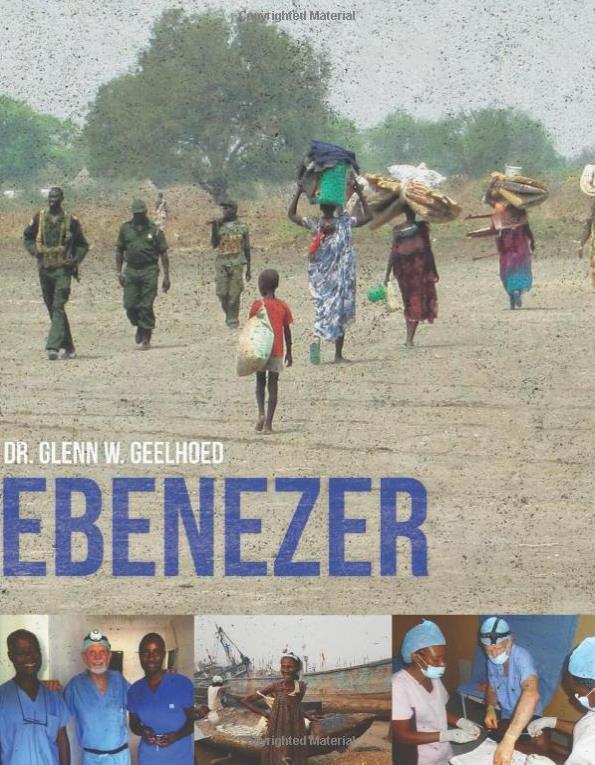

I have been planning a long time to review a book written by one of my personal heroes, Dr. Glenn Geelhoed, and am delighted that the day has finally arrived. I first met “Dr. G” in 2011 in California as we prepared to deploy to Burma as part of Team Rubicon’s “Project Karen-Shan” medical team. Once inside Burma, we trained the Karen and Shan tribal community healthcare workers who were (and are) striving desperately to improve their medical capabilities.

While I had received foundational training in the principles of Tropical Medicine at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, nothing had sparked my interest in the topic until I sat in on the classes being taught by Dr. G. He was a powerful educator and a seemingly endless trove of information on not only Tropical Medicine, but every other medical discipline as well. Medicine aside, his encyclopedic knowledge of the natural world made me feel I was in the presence of a once-in-a-century personage such as Charles Darwin, and the enthusiastic tales of his adventures on all seven continents – to include every African country – held our team spellbound during the quiet evenings in the Burmese jungle.

“Ebenezer is an amazing story, giving us an authentic picture of historic events and brave people. Dr. Geelhoed is indeed one of the few heroes of our unheroic time. I hope some of our young friends will read the book and be inspired by it to undertake tough jobs in tough places.”

Freeman Dyson, winner of the Templeton Prize, professor of physics at the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton, and New York Times book reviewer

Glenn W. Geelhoed received his BS and AB cum laude degrees from Calvin College and his MD cum laude from the University of Michigan. Following the Harvard surgical internship and residency at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Boston, and the Boston Children's Hospital Medical Center, he served as clinical associate and senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. After completion of his chief surgical residency, he joined the full-time faculty at George Washington University as an Associate Professor of Surgery in Washing ton, DC in 1975. He was awarded an appointment as clinical scholar of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. He is a member of numerous medical, surgical and international academic societies, including the Society of University Surgeons and The American College of Surgeons, and is a past president of the Washington Academy of Surgeons. He was selected the James IV Travelling Scholar of 1986, and inducted into the Academie de Chirurgie de Paris in l990.

His major clinical interests are in endocrine surgery, surgical physiology, oncology and transplantation. He has been a frequent Visiting Professor in most of the United States and on all continents, traveling with a strong interest in global health that includes the third world. He is a widely published author accredited with several books and over 500 published journal articles and chapters in books, and has a major interest in medical education in academic, professional and international organizations.

To assist in developing further volunteer health and surgical services in underserved areas of the developing world, he completed the DTMH in the University of London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in l990, and a Masters degree in International Affairs from the Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University, in l99l. He completed the MPH degree in Epidemiology: Health Promotion/Disease Prevention in 1993, and in 1995 additionally achieved the MA cum laude in Anthropology with special interests in Biologic and Medical Anthropology. He is currently a candidate for the Ph.D. in Human Sciences in an interdisciplinary program at George Washington University, and planning a further period of research and service in southern Africa supported by an award as Senior Fulbright Scholar, African Regional Research Program, for 1996. He has developed both Medical Anthropology and Tropical Medicine programs within the MPH programs of George Washington University, and as GW University Professor of International Medical Education is working on the development of an international health center and international medical education program.

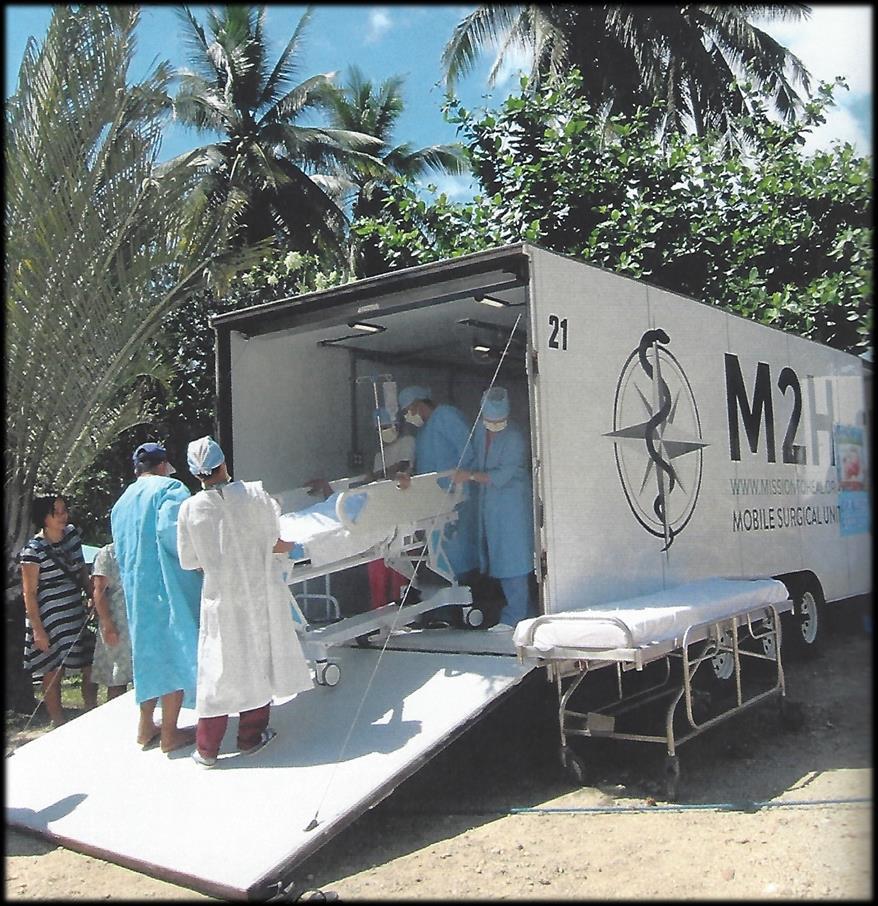

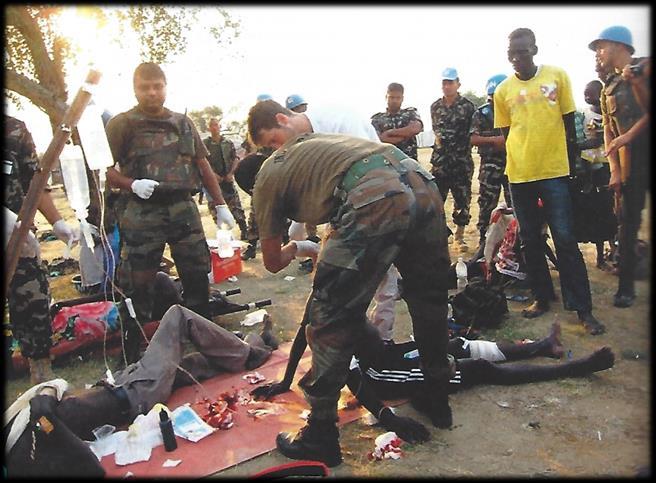

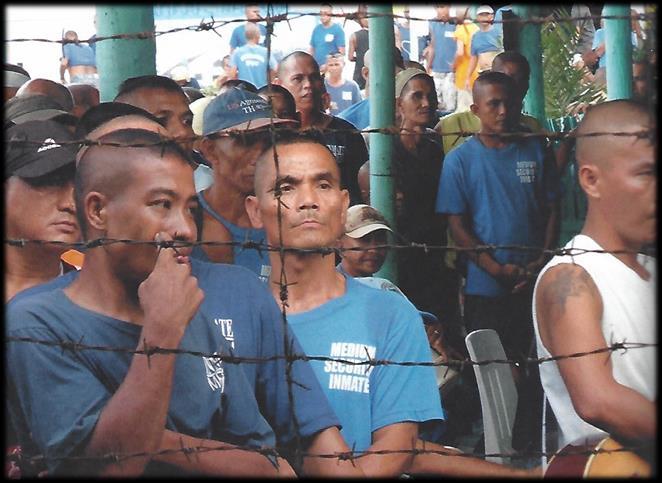

“Ebenezer” recounts the 2014 adventures of Dr. G and his volunteer-driven humanitarian organization Mission to Heal (M2H) as they worked their way through Nigeria, South Sudan, Liberia, and the Philippines. Besides the inherent difficulty of bringing healthcare and healthcare training to “the bottom billion” - as Dr. G refers to the poorest of the poor - the mission was beset by obstacles both calamitous and unforeseen, not least of which was an armed raid in South Sudan, a major outbreak of Ebola in Liberia, and Dr. G himself coming down with cerebral malaria upon his return to the U.S.

Dr. G is a prolific writer and photographer, and it is my privilege to share some of the many compelling photos and excerpts from “Ebenezer,” penned by my nomination for The World’s Most Interesting Man.

1) delivery of first class medical surgical care to remote peoples who would otherwise have no access;

“M2H [Mission to Heal] has three primary missions:

2) transformational learning through encounters with the developing world and its peoples who live by ingenuity and cope by improvisation – lessons we need to learn from them – taking care of larger numbers, of bigger problems, with far fewer resources;

3) indigenization of health care skills, empowering those who will assume responsibility for the burden of care. The MSU [Mobile Surgical Unit] is a powerful tool to accomplish this outreach to the “FPF” – Furthest Peoples First. It is a medical educational vehicle for transplanting motivation and means for development, self-sustaining and not colonial benevolence which may suffer the attrition of those weary of well-doing. It is very rewarding on both sides of this transformational learning exchange.”

“The team was convinced they could never learn all the medicine. ‘What do you need to know to take on the responsibility of caring for another in health professions?Always more than you do!’Glenn assured them that none of it was so hard; it was simply so much. There is a universe of possibilities to which the human body and mind are susceptible. And a whole panoply of necessary knowledge that must be absorbed by someone who is motivated, interested and compulsive enough to stay up late, study hard, and hold onto the information until such time that it is confirmed in experience in each new environment. When the environment changes, you sometimes must take out that file of information stored in your brain and see if it applies in a new, for example, tropical environment. If that set of solutions solves the problems encountered, then that pattern is reinforced, and it is likely never forgotten. This is one reason M2H can, perforce, train local non-medical personnel to treat medical problems. There are common illnesses or conditions in certain areas of the world. By knowing the most obvious symptoms and learning how best to handle them, many people can be helped. Will some things be missed? No doubt, but many others will be caught. It is the first step.”

- Ebenezer

- Ebenezer

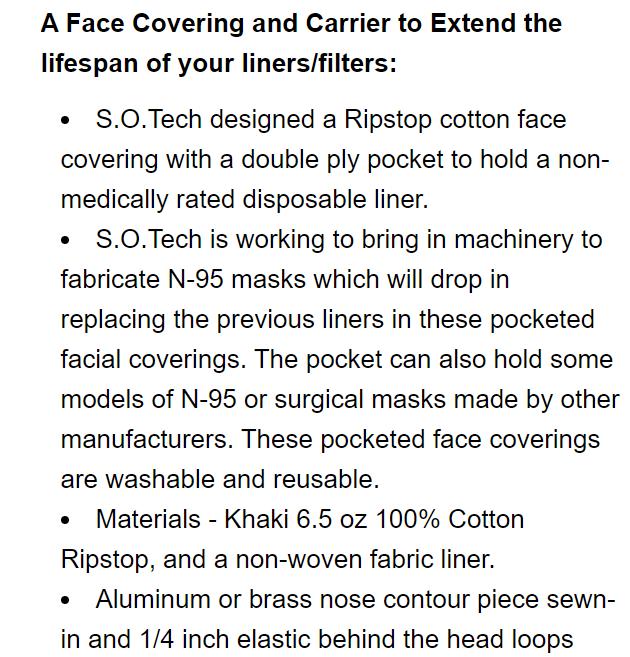

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS & diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory techniques

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

Canine medicine

…and much more!