The official newsletter of the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation Summer 2018 2 About CoROM 3 Dean’s Desk 3 Message from the Medical Director 4 Photo Gallery 5 CoROM Courses 7 Where Are They Now? CoROM paramedic graduate Ryan Elliott on saving lives and his educational goals 8 Instructor Spotlight Q & A with Thomas Mpande 9 Trends in Traumatology Jason Jarvis’ experience with the REBOA in a human cadaver lab 6 Boots on the Ground A CoROM instructor’s experience in the emergency department of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre by Nicole Foster 9 United in Purpose CoROM’s alliance with Tanzania’s Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre by Aebhric O’Kelly FEATURES 10 Continuing Education Neil Coleman on the fundamentals of good research 11 Test Yourself ECG Recognition Drug Calculation Clinical Case 12 Resources A selection of gear, references, books, websites and podcasts 13 Journal Watch Updated Global Burden of Cholera in Endemic Countries Maggot Therapy for Wound Care in Austere Environments 14 Book Review The Death of the Golden Hour and the Return of the Future Guerrilla Hospital Aebhric O’Kelly and Thomas Mpande at the 2018 Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly in North Carolina

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine is an academic not-for-profit organisation for health care professionals working in the remote, offshore, transit, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary MedicalAdvisory Board (MAB) consisting of medical professionals from NorthAmerica, Europe,Africa and the Middle East. The College is gaining registration with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta to become a degree granting educational facility.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and difficult environments.

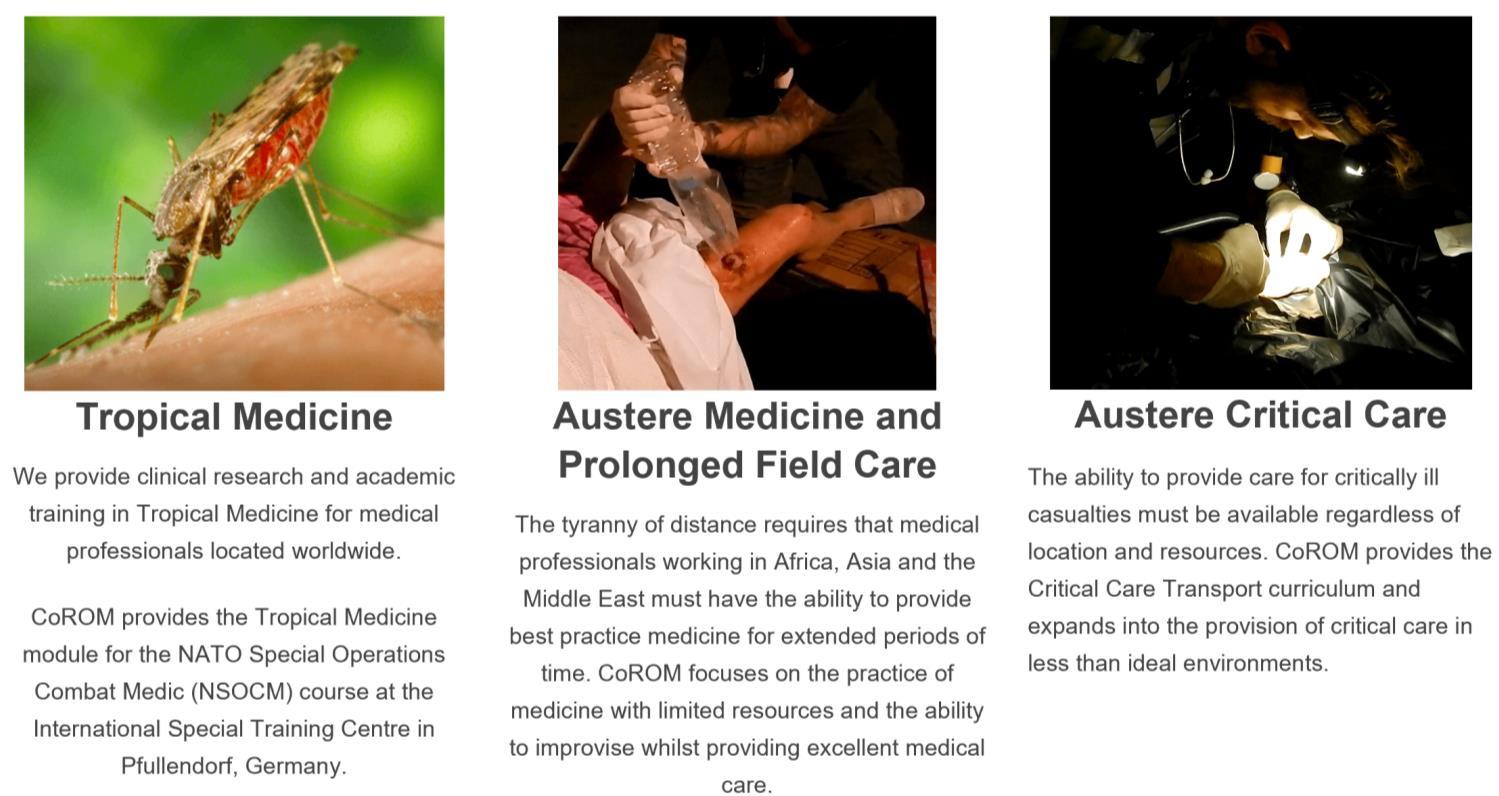

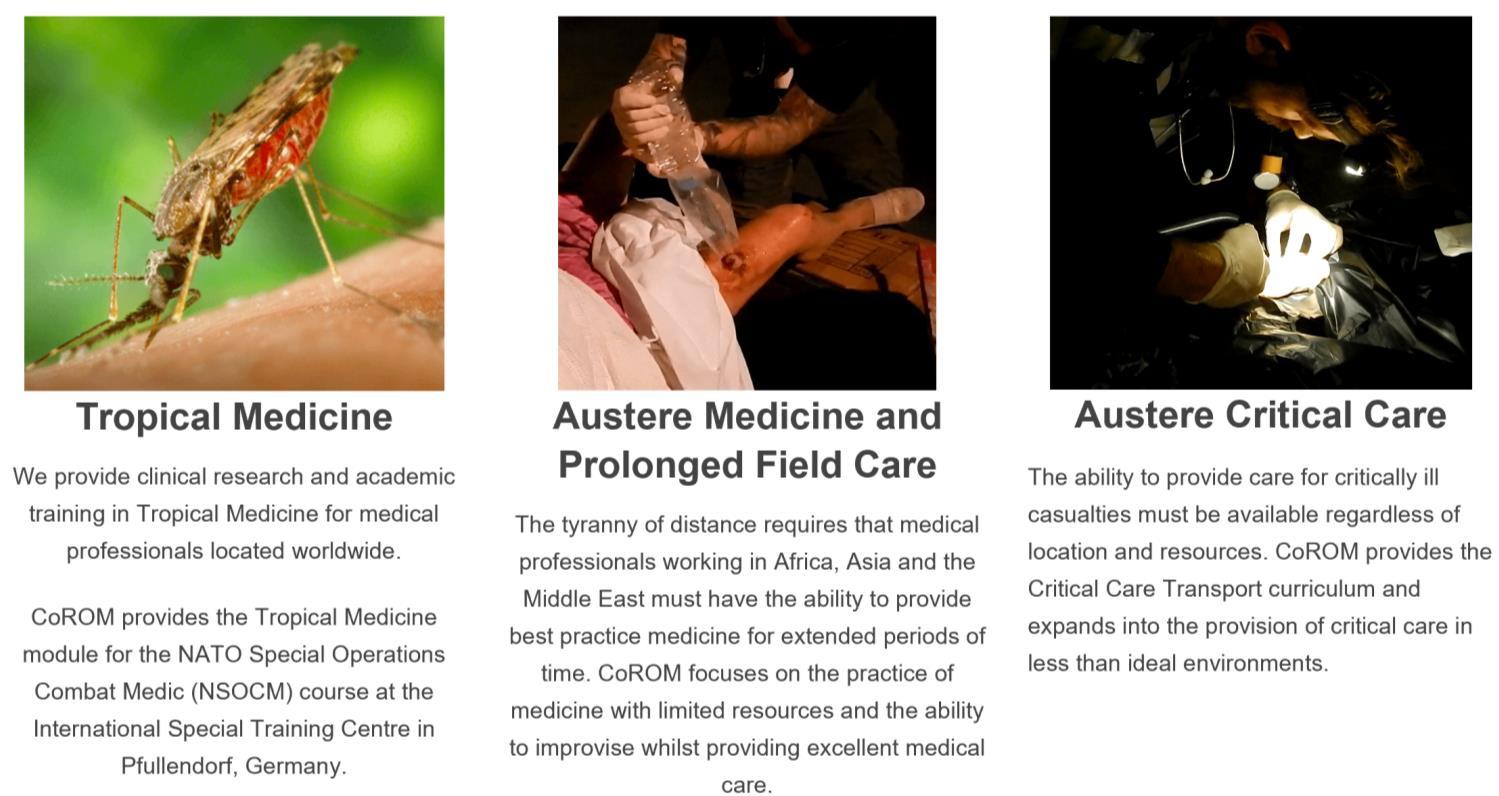

What does CoROM specialise in?

About CoROM 2

Dean’s Desk

It is with great pleasure that we launch our first College newsletter. For the past two years, the College has been gaining ground and going from strength to strength.

It is my intention that this newsletter provide updates, educational content and current medical topics and research.

We’ve had a busy year with a return to North Carolina and the Special Operations MedicalAssociation ScientificAssembly, where we exhibited CoROM for the second year running. We will also be attending the Remote Damage Control Resuscitation Symposium in Norway this June.

ThisAugust will see the initial offering of the CoROM Remote Paramedic course in Tanzania. It is a fantastic location to earn your paramedic qualification. We have full access to the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, to include their human anatomy laboratory.

Keep an eye on our Facebook and website for updates on our adventures.

Message From The Medical

Director

First, I would like to thank Jason Jarvis for his hard work and effort in launching The Compass as the newsletter of CoROM

Writing this short piece makes me appreciate how quickly the College has progressed since its launch in June 2016.

There have been courses run from the College as well as educational contracts to NATO and other institutions

We pride ourselves in making sure our instructors are not only experienced but also able to deliver both theoretical content and practical skills Moreover, we are gradually recruiting instructors not only from the military but also civilian background.

My aspiration is to ensure that CoROM can supply modules for Bachelor and Master Degrees for other Universities and educational institutions

Finally, I would like to wish our students (past and present) every success in their professional lives and encourage them to contribute to CoROM’s development

3

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E MA FAWM DipPara CCP-C TP-C

Winston de Mello MBBS FRCA FFPMRCA FIMCRCSEd CCP-C

Photo Gallery

4

After Action Review led by Dr. Winston de Mello, following a helicopter crash training scenario in Malta

Dr. Andrew Stephens shares his ultrasound expertise at KCMC, Tanzania

Pretty Bay – home to CoROM’s Maltese classroom facilities

Intravenous cannulation training in Malta

Scenario training in Malta

Casting training in Malta

CoROM Courses

SEATTLE

Tropical Medicine short course

TTEMS

RAMS (courses under development)

MALTA

ITLS 3 June 2018

CC-P 22-27 October 2018

CRP 29 October-24 November 2018

RMLS 7-9 November 2018

TTEMS 19-23 November 2018

RAMS 26-30 November 2018

CRP 18 March-13 April 2019

TTEMS 8-12 April 2019

RAMS 15-19 April 2019

CC-P 29 April-4 May 2019

PARSIC (dates TBD)

Burns course (dates TBD)

Pain Mgnt for Clinicians (dates TBD)

TANZANIA

CRP 27 August-22 September 2018

TTEMS 17-21 September 2018

CRP 2 September-28 September 2019

TTEMS September 2019

LEGEND

THAI-BURMA BORDER

Clinical TTEMS course

14-26 January 2019

CC-P: International Critical Care Paramedic (with optional pre-study week)

CRP: CoROM Remote Paramedic*

PARSIC: Pre-Hospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction

RAMS: Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS: Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS: Tropical, Travel, and Expeditionary Medicine Skills

* The CRP course also includes 20-30 weeks of online training, plus a 400-hour clinical rotation.

Advanced Certificate and Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Clinical Placements

University teaching hospital, Moshi, Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Level 3 Health and Safety for the Workplace

Level 3 Food Safety for the Workplace

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org.

5

Boots on the Ground

ACoROM instructor’s experience in the emergency department of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre

by Nicole Foster

by Nicole Foster

The College provides the opportunity to gain clinical experience in the Emergency Department at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Tanzania.

I was fortunate enough to have some spare time on my hands to experience this placement for three weeks in April 2018. I was greeted by Dr Francis Sakita - the head of the EDand given a general tour of the hospital grounds. It is one of the larger hospitals in Tanzania, and all departments were full or overflowing. The ED has four medical, three trauma and two paediatric beds. By the time our morning tour came to an end, the morning rush had begun. Typical ED presentations don’t really change throughout the world, and non-communicable diseases are prevalent wherever you are. Hypertension, diabetes, heart failure were common, with smatterings of MVC trauma (it’s popular to ride in Bajaji’s - tuk tuks or to grab a lift on the back of open tray trucks). Communicable diseases such as HIV, TB are assumed until proven otherwise. PPE (glove and masks) is essential when heading into any cubicle. The staff is eager for you to help, and common skills performed include vital sign survey, airway manoeuvres and ventilation, IV and blood draws, medication and fluid administration, wound dressing, cardiac monitoring and ultrasound, and participating in cardiac arrests (adult and paediatric).

As it was the “long wet” season (not to be confused with the short wet), it meant that the kids got sick

and the presentation of three, four or five children would usually come in at once (usually the 3:30pm rush). Most prevalent was respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, sepsis and some more unusual presentations such as Ewing’s Sarcoma. The greatest challenges working in countries such as Tanzania is how the system works – the doctors and nurses are amazing (improvised medicine at its finest!) to provide care with what they have (bring a head torch as power outages are common). The people are friendly and the experience was eye-opening.

If you would like to experience KCMC as a clinical placement, please contact the College for further information and available dates.

If you would like to donate to the cause and support ‘Medications forAfrica’that Dr. Drew has organised for a smaller hospital in the Kibosho region –https://au.gofundme.com/medications-for-Africa

–

Nicole Foster BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

6

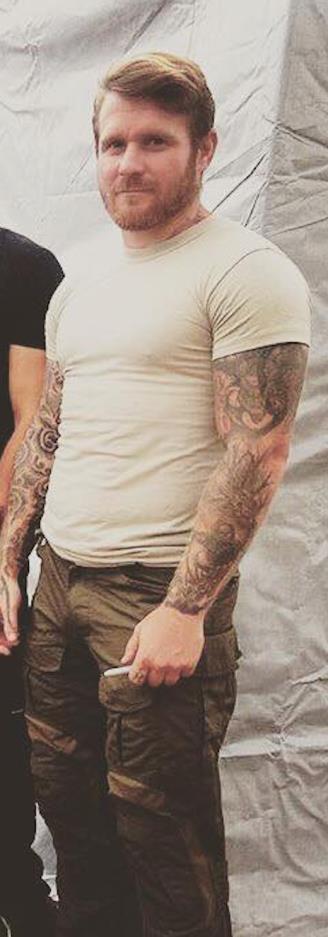

Where Are They Now?

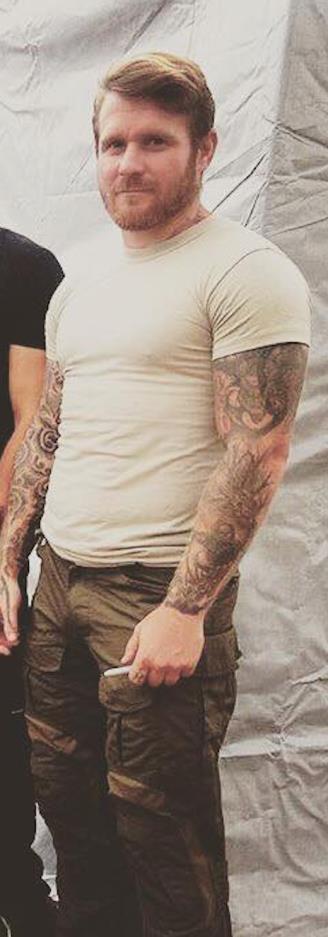

CoROM paramedic graduate Ryan Elliott on saving lives and his educational goals

Ryan Elliott is a graduate of the CoROM Remote Paramedic course and currently works in Nigeria alongside the Tri-Services, mentoring team medics.

“Since qualifying as a paramedic, my time has been spent mostly working at sea for a fleet of super yachts

The training and skills I acquired from the Industry Paramedic course has undoubtedly saved one life, as well as allowed me to suture a few fingers back up and ease the sickness of the crew on several occasions.

Concerning the life saved, I was called to the stern of a yacht, where a patient had gone unconscious for no apparent reason

As I went through the ABC’s and primary survey, it became obvious she had been stung by an unknown insect - we suspected a wasp – and I recognized that she had gone into anaphylactic shock

After I reversed the anaphylaxis, I evacuated the patient via tender to the local hospital, where she made a full recovery.

At present I am awaiting a response to my application to university for the Masters in Physician Associate Studies I have already sat an interview and completed my application online, and look forward to matriculating.”

7

Ryan Elliott Industry Paramedic

Ryan Elliott conducting medical training in Kabul, Afghanistan

Ryan Elliott onboard an Mi-8, enroute to the Kajaki Dam in southern Afghanistan

Instructor Spotlight

Q andAwith Thomas Mpande

Originally hailing from England, Thomas Mpande now lives in Washington, DC, where he works for Grey Medical Group. Thomas is CoROM’s Austere Medicine Lead and a member of the CoROM Advisory Board. In addition, he was an instrumental faculty member of the original 2017 RAMS course held in Malta.

What aspect of CoROM motivated you to join the College?

Thomas Mpande PgCert DipPara EMT-P CoROM Austere Medicine Lead CoROM Advisory Board Member

The wealth of experience available amongst the instructors at the college provided a clear draw to me. It was a mix of medical and educational experience that provided me an assured sense of the high standards that would exist, keeping me both challenged and supported.

What is your favorite teaching topic at CoROM?

My favorite subjects being covered at the moment are tropical diseases and remote area medicine. I feel that it is something that has not had the limelight it is due. Despite teaching on the course, I am yet to have a day teaching that I do not learn numerous amounts of new information. I'm looking forward to watching the classroom instruction and wider publication develop over the next few years.

Where would you like to see CoROM go in the next five years?

I have a vested interest in the progress of the 'Austere Medicine' post-graduate diploma over the next 5 years, into a masters. However, it would be great to have 'Austere Medicine', 'Tropical Medicine' and 'Austere Critical Care' as fully functional Masters programs within the next 5 years. I would also like to see CoROM lessons being taught in even more locations than Malta, Germany and Tanzania.

Describe a medical case that has had a lasting impact on you.

Acase that I often use in lessons to make a point, and has forever improved my practice, was a local national patient with an entry and no exit injury to the right arm, in Afghanistan. I had 3 other patients with reasonably destructive, but not immediately life threatening, gunshot injuries. I had a two-hour hold at site, prior to transit to the nearest medical facility. I found myself initially fixated on the obvious injuries, neglecting the patient with the entry GSW and not actually identifying it in my initial sieve. It was only at the on-set of tension pneumothorax signs and symptoms (mainly the labored breathing) that I moved to treat this patient. This was 45 minutes after receiving the casualties. I've forever kicked myself for not being thorough enough on my initial assessments. Remote sites can be distracting and overwhelming environments to work in, this being an example of it getting the better of me. There’s no excuses for not making a truly thorough assessment and you should always accept your mistakes as lessons!

What are your top three go-to medical references for remote deployments?

My three current "go-to" medical references are the 'Merck Manual Professional Application', 'Tarascon Primary Care Pocketbook' app and of course the CoROM Field Guide.

8

Thomas Mpande on deployment to East Africa in 2015

United in Purpose

CoROM’s alliance with Tanzania’s Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre

by Aebhric O’Kelly

by Aebhric O’Kelly

An official Memorandum of Understanding exists between CoROM and KCMC, which states that we can produce jointly accredited tropical medicine degrees, jointly run medical courses in Tanzania, and provide clinical placements for our delegates.

The MoU allows for the College to hire KCMC professors for teaching on our courses throughout the globe. The College has flown three of the KCMC professors to Malta where they taught on our tropical medicine courses.

CoROM continues to support KCMC and Kibosho District Hospitals by way of medications, medical equipment, and medical expertise.

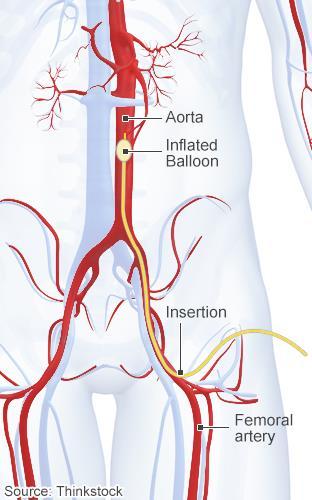

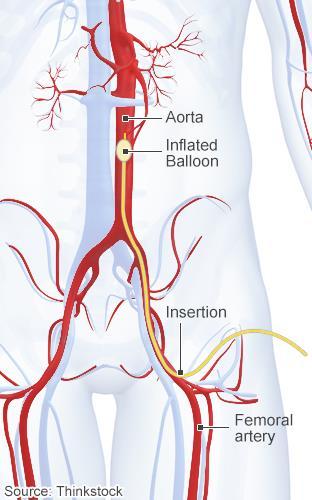

Trends in Traumatology

Jason Jarvis’experience with the REBOAin a human cadaver lab

At the 2018 Special Operations MedicalAssociation Scientific Assembly I had the opportunity to practice the use of the REBOA on human cadavers. The REBOA(Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of theAorta) is a new take on the decades-old technology of aortic balloon occlusion (first attempted in the Korean War) used to prevent haemorrhage of the abdomen and lower extremities.

Manufactured by Prytime Medical™, the REBOAis used in 246 hospitals worldwide, and in a handful of out-of-hospital services. The application of the device is fairly straightforward once the “crux move” has been accomplished: cannulation of the femoral artery. While the device is primarily used in-hospital, it has also been successfully implemented out-of-hospital; select U.S. military medics are currently being trained in its use.

In skilled hands, the REBOAshows promise for field use, and may soon make an appearance in CoROM advanced practice coursework.

9

CoROM Dean Aebhric O’Kelly presenting medical equipment to Dr. Francis Sakita at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre

Jason Jarvis 18D BS NREMT-P TP-C CoROM Tropical Medicine Lead The Compass editor

Continuing Education

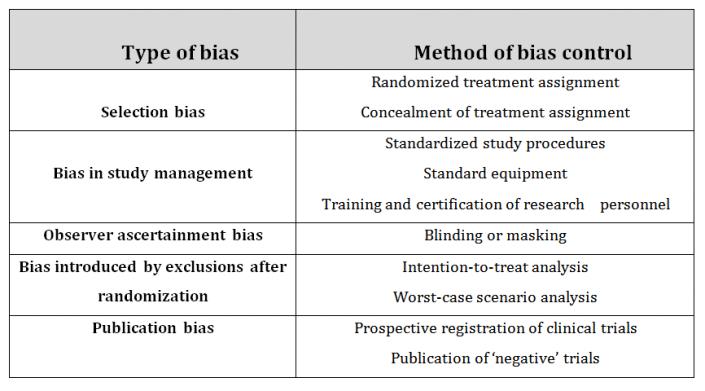

Neil Coleman on the fundamentals of good research

Research, or finding information, may not be the first thing a paramedic thinks of when they enter the profession. However, the entire medical profession is built on research. From drug trials to lessons we learn from each other in publications and during training courses, we are constantly researching.

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Education Manager

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Education Manager

Let me give you an example. You administer a fictitious medication (Medication X) to a patient. Over the next hour they develop a cough.You are suspicious that the medication may have caused this. So how do you find out if this medication is known to do this?You research the medication.

As this is our first foray into research, we won't blow the lid off the topic. Let’s take a couple of terms you will come across and explain them in simple, (hopefully) easy to follow language.

Firstly, let’s review the term “research.” What are you doing when you research? Quite simply, research is the investigation of a topic... or as a Police service friend of mine once said...it’s gathering information. I personally believe this is a very accurate way of putting it. Research must be fair and open, and it’s generally held that the best research is the one that reviews both sides of an argument (so the manufacturers of Medication X say it won’t cause our cough, but from online research you find that several clinicians have witnessed this side effect). In the example offered, outlining both sides of your research would make for a stronger paper, or submission, or discussion point. In simple terms, be open to both arguments.

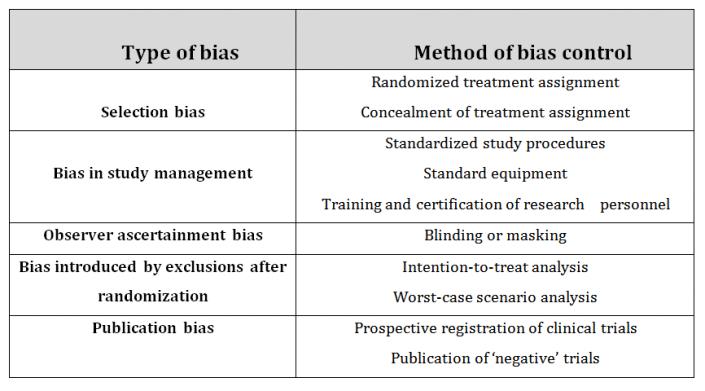

Bias is another term you will see in research a lot. It simply means that research has been influenced in some way. This could be the manufacturers of Medication X funding the study, or perhaps a little less obviously, a tutor or instructor taking a survey of his or her students. This would be viewed as bias, as the students may feel they “had” to complete the survey.

I hope that this brief article will help break down what is a very broad topic. In subsequent articles we will continue to introduce terminology and “how-to” sections on several topics.

10

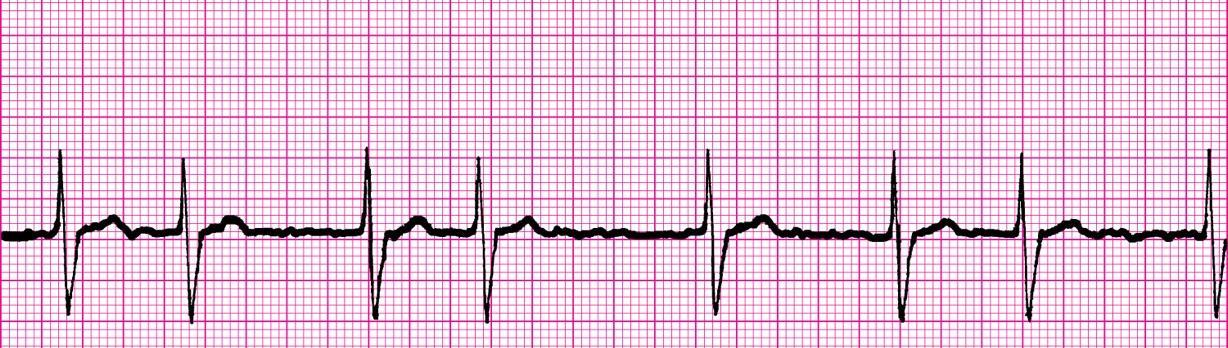

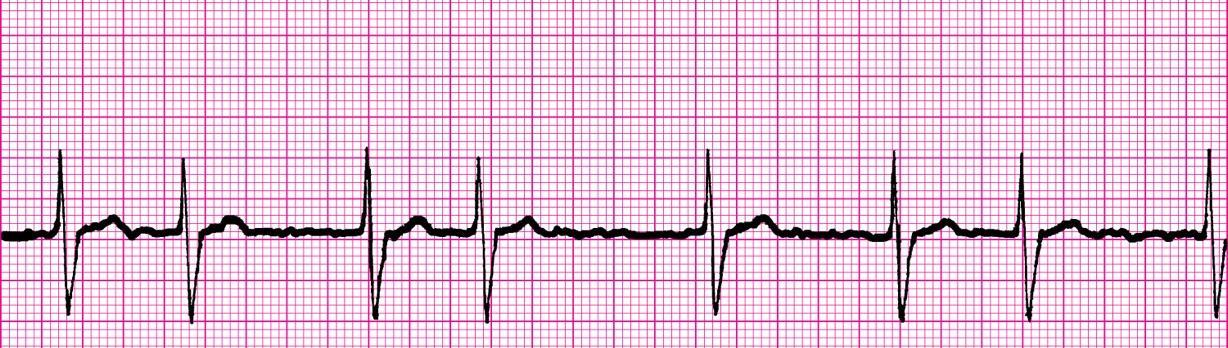

Test Yourself

ECG Recognition

A. Second degree heart block, Type 2

B. Controlled atrial fibrillation

C. Third degree heart block

D. Uncontrolled atrial fibrillation

Drug Calculation

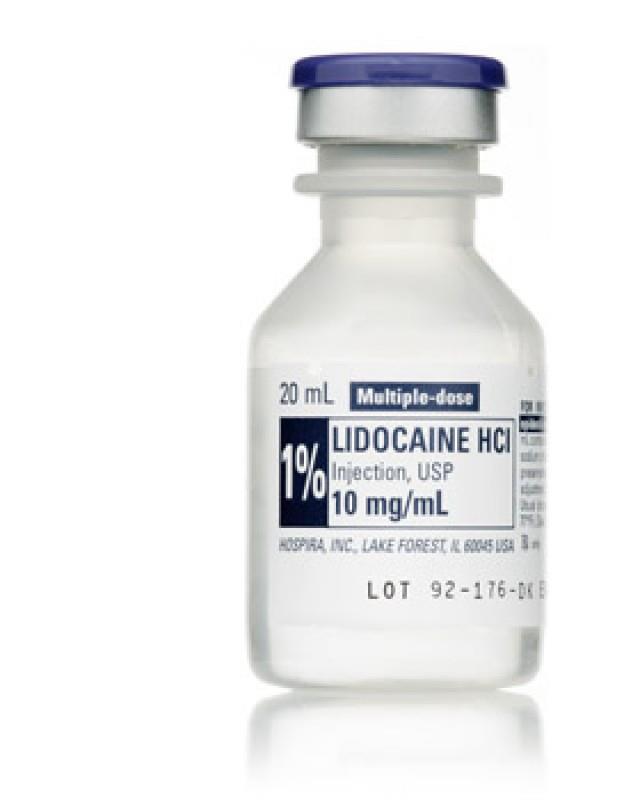

You are preparing to debride a severely-necrotized spider bite on the dorsal aspect of your 60kg patient’s hand.

Thirty minutes after performing an axillary nerve block with 10mL of 1% lidocaine, the patient is still sensitive to sharp touch around the wound.

How many more mL of l% lidocaine can you inject before reaching a maximum dose of 3mg/kg?

Clinical Case

While manning a remote clinic in Uganda, you examine a 28-year old local woman who says she “feels like she has malaria again.”

She is febrile, with muscle aches, headache, and a 3cm erythematous rash surrounding a painless papule on her leg.

The patient states she has had the headache and constitutional symptoms for one week, while the papule and rash developed around an insect bite that occurred two weeks ago.

Pregnancy and malaria RDTs both yield negative results, but you follow up with a Giemsa-stained thin blood film that reveals the image to the right.

What pathology is at the top of your differential diagnosis?

Answers will appear in the next edition of The Compass

11

Resources

Aselection of gear, references, books, websites and podcasts

Mountainsmith™ Lumbar Pack

While not designed as a medical bag, this voluminous lumbar pack works well as a mobile first-response bag, riding conveniently beneath any large backpack.

Compartmentalization of medical kit away from clothes, food, mosquito netting, etc. is one of many keys to providing prompt medical support on expeditions.

Oversized/high-visibility zipper pulls are a must-have feature with any bag used for rapid medical response.

Medical References (Thomas Mpande’s picks)

Books: Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped Our History by Dorothy Crawford Cutting For Stone:ANovel by Abraham Verghese Mountains Beyond Mountains by Tracy Kidder

Websites: sphereproject.org (Guidelines for humanitarian disaster response)

rdcr.org (Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research Network (THOR))

pfcare.org (Repository of articles and resources on Prolonged Field Care)

cdc.gov (Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (pre-deployment information)) immunise.health.gov.au (Free Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10th edition)

Podcasts: Prolonged Field Care

ICU Rounds

This Week in Parasitism

12

Journal Watch

Updated Global Burden of Cholera in Endemic Countries

Public Library of Science Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015 Jun; 9(6): e0003832

Published online 2015 Jun 4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832

Mohammad Ali, Allyson

Justin V. Remais, Editor

R. Nelson, Anna Lena Lopez, and David A. Sack

AUTHOR SUMMARY

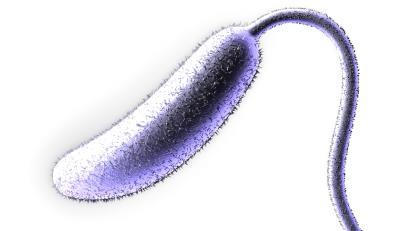

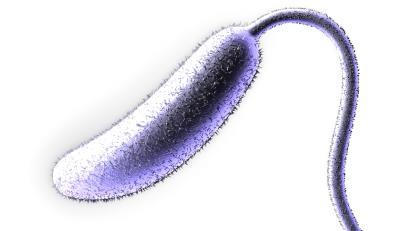

The global burden of cholera is largely unknown because the majority of cases are not reported. The low reporting can be attributed to limited capacity of epidemiological surveillance and laboratories, as well as social, political, and economic disincentives for reporting. We previously estimated 2.8 million cases and 91,000 deaths annually due to cholera in 51 endemic countries. Amajor limitation in our previous estimate was that the endemic and non-endemic countries were defined based on the countries’reported cholera cases. If a country did not report cases even though the country had cholera, the country was classified as cholera free. This time we addressed this limitation by using a spatial modelling technique, which helped us define the cholera-endemic countries based on access to improved water and sanitation in the country as well as cholera incidence in neighboring countries. Our new estimate illustrates 2.9 million cases and 95,000 deaths in 69 endemic countries, with the majority of the burden in Sub-Saharan Africa. The sustained high burden of cholera points to the necessity for integrated and improved control efforts, and these findings may help programmatic decision-making for controlling the disease in endemic countries.

Vibrio cholerae, the causative organism of cholera

Maggot Therapy for Wound Care inAustere Environments

Journal of Special Operations Medicine. Summer 2017

https://www.jsomonline.org/jsomstorefront/index.php?rt=product/product&product_id=458

Ronald

A. Sherman, MD, MSc, DTM&H; Michael R. Hetzler, 18D, ATP

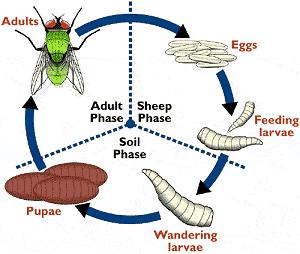

ABSTRACT

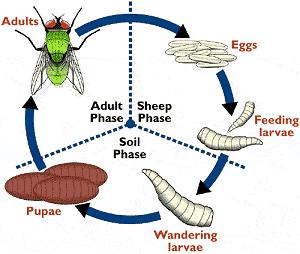

The past 25 years have seen an increase in use of maggot therapy for wound care. Maggot therapy is very effective in wound debridement; it is simple to apply and requires very little in the way of resources, costs, or skilled personnel. These characteristics make it well suited for use in austere environments. The use of medical-grade maggots makes maggot therapy nearly risk free, but medical grade maggots may not always be available, especially in the wilderness or in resource-limited communities. By understanding myiasis and fly biology, it should be possible even for the nonentomologist to obtain maggots from the wild and apply them therapeutically, with minimal risks.

13

Adult Phase Wound Phase Soil Phase

Lucilia sericata – aka, the common green bottle fly – one of the most commonly used blow flies for maggot therapy

Book Review

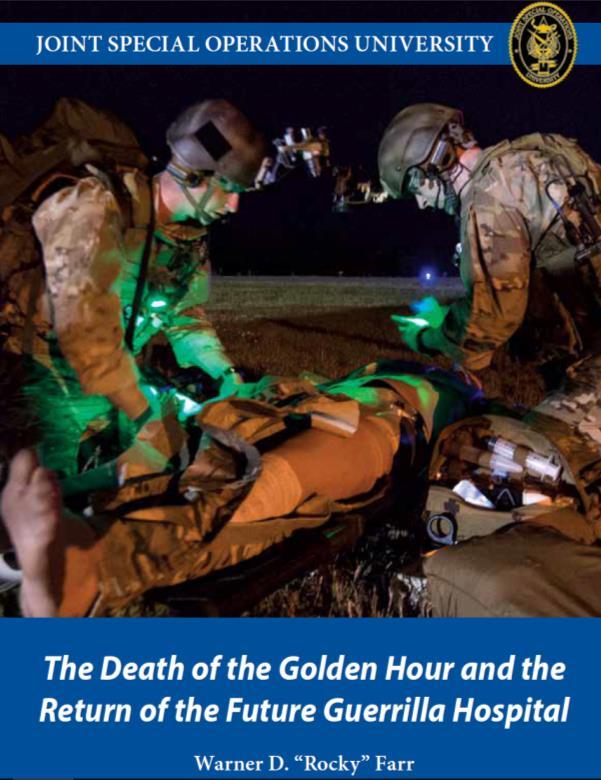

The Death of the Golden Hour and the Return of the Future Guerrilla Hospital

By Warner D. “Rocky” Farr Joint Special Operations University Press

Published in 2017

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis

Dr. Warner “Rocky” Farr’s eBook Death of the Golden Hour and the Return of the Future Guerrilla Hospital –available free of charge – offers an insightful review of field medical practice within the context of nineteenth and twentieth century guerrilla warfare.

The title is a reference to the operational environment in which Special Operations Forces are designed and trained to work: austere far-forward locations where casualty transport to high-level surgical facilities can be a several-hours-long endeavor at best. This eBook is timely, as the Iraq and Afghanistan theaters draw to a close and the days of lightning-fast evacuations become a thing of the past. In the author’s own words, “…in the Iraq andAfghanistan warzones specifically, the Department of Defense (DOD) mandated that the “golden hour” is, by default, a worldwide standard. This is neither true, nor militarily supportable. Already in Africa, and soon in the Pacific and SouthAmerica, teams must hold the wounded for a prolonged period of time before evacuation due to challenges with nonstandard land and air transportation with limited availability.”

Death of the Golden Hour is broken down into bite-sized historical chapters, such as “World War I SOF and Medical Support:Africa and the Middle East,” “Vietnam, Special Action Forces, and the Green Berets,” and “The Rise of SOF and the Small Wars of the 1980s and 1990s.”

In the second chapter, titled “SOF Unique Medical Support Requirements,” Dr. Farr highlights the importance of medicine to small teams operating with little to no support in the field: “Twenty percent of the enlisted structure on a SF “A” Team are medical for a reason. Medicine is not just important, it is essential to successful UW [Unconventional Warfare].” In several other instances, Dr. Farr re-emphasizes the importance of far-forward medical capabilities in service to guerrilla fighters. Besides the obvious practical reasons for having a skilled medic close at hand, he observes that the psychological impact should not be overlooked. He drives this point home with a quote from ColonelAaron Bank, the founder of Special Forces and former OSS (Office of Strategic Services) officer: “…the individual guerrilla would perform his battle duties with more ardor and spirit and accept more risks if he knew that there was medical support in case he became a casualty.”

The most fascinating episodes (to me) include the against-all-odds exploits of WWI German General von Lettow-Vorbeck in East Africa, and the audacious Norwegian surgeons-on-bicycles in Soviet-era Afghanistan. Although little ink is spent on guerrilla warfare legends Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Mao Tsetung, several other theaters of guerrilla conflict are given treatment in Death of the Golden Hour, including Yugoslavia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Greece, France, Lithuania, Korea, and others.

In the chapter “Back to the Future: Prolonged Field Care” Dr. Farr calls attention to the current efforts of the Prolonged Field Care working group (pfcare.org) to codify best practices for this phase of casualty care.

The book concludes with the reiteration that, as Special Forces returns to business as usual (i.e., farforward deployments in austere locations with minimal outside support), they retain the hard-fought lessons paid for in blood by those who have gone before them.

All-in-all, Death of the Golden Hour was a superb and illuminating read, and, thanks to the efforts of Dr. Farr, I have added several new titles to my must-read list (starting with “My Remembrances of East Africa” by von Lettow-Vorbeck).

14

by Aebhric O’Kelly

by Aebhric O’Kelly