I am both humbled and honored to have been selected as Executive Dean of CoROM. A decade ago, I met Aebhric when he established a relationship with the International Board of Specialty Certifications (IBSC) to use our Board certification exams for flight, critical care, and tactical paramedics as part of CoROM classes in Malta. I have always been impressed with his vision and commitment for the College, and it is because of him that I take up the mantle.

Based on my review of the College’s history, current character, direction, and the excellent faculty who are committed to the purpose of realizing the College’s mission, I believe we have an essential platform to improve the delivery of healthcare worldwide. The three key word in the College’s mission statement are “excellence”, “research”, and “worldwide”. This is not a charge that I take lightly. CoROM promises a financially attractive model, an academic home where paramedic research opportunities abound, and is a touchstone for the necessary degrees for professional advancement and programs for continuous professional development and continued competency. We are nimble enough that can be responsive to the ever-evolving nature of emergency medicine and have a true impact on making the world a better place for everyone. Dean O’Kelly has keenly positioned CoROM to be the worldwide leader for paramedic education from CPD to Doctoral-level research. My commitment is to build on this success.

To help you understand where I come from and what I have to offer, allow me to say that I have always been committed to the betterment of the paramedic profession I bring a unique combination of skills and experiences will allow me to lead CoROM into the future I started my EMS career in college when the volunteer fire department (who fielded a cave rescue team for the Eastern Region of the National Care Rescue Commission (ER-NCRC)) asked me to go to EMT school It was from that starting point that I realized I had found my niche I have worked in both clinical and administrative areas of healthcare, from ER Tech to Flight Program Director With 35+ years of experience in clinical settings ranging from urban trauma centers to community emergency departments; supervisor and preceptor roles in a fire department-based EMS systems and critical care transport; teaching experience in hands-on skills to graduate level cohorts; experience in both ground and flight environments; law practice experience in a boutique EMS focused law firm and in academic medical center risk management; and I bring expertise in budgeting and resource management Today this varied and insightful perspective will help to continue CoROM’s success

I am past-vice chairman of the IBSC Board of Directors for 15 years until I assumed a full-time role as the Chief Operating Officer, a past-president of the International College of Advanced Practice Paramedics (formerly the International Association of Flight and Critical Care Paramedics Association (IAFCCP)) and a former member of the Board of Directors of the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). I am a section editor for the Air Medical Journal (AMJ) and write a monthly feature for the AMJ on legal issues in critical care transport and am a benchmark editor for the International Journal of Paramedicine. For the last 3 years, I have sat on the Managing Board and have been a staff member of CoROM.

My paramedic education and Baccalaureate degree are from The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences with an Executive MBA from Madison University. I also hold a Juris Doctorate from the University of New Hampshire School of Law as well as a Graduate Certificate in Health Law and Policy. Additionally, I maintain my NREMT paramedic certification and my Commonwealth of Pennsylvania paramedic license and hold Board certification as a Certified Flight Paramedic (FP-C), Certified Critical Care Paramedic (CCP-C), Certified Wilderness Paramedic (WP-C), and Certified Medical Transport Executive (CMTE).

First, I agreed to take on the executive leadership role because I believe in Aebhric and CoROM. Secondly, it allows me the opportunity to work with an amazing group of people who also believe in the College. I will make the most of this leadership change to build on the solid foundation to lead an international strategic plan and resource model, support accreditation and quality enhancement initiatives, strategically grow graduate, online programs, and short courses and oversee a revenue model that allows continued and sustainable growth. My focus on initiatives will extend beyond budget and metrics, to include academic excellence, student success initiatives, diversity and inclusion, student-faculty research and mentoring, strategic enrollment, and community collaborations.

None of the above can be done in a vacuum I will need the strong support from both faculty and staff as we define programs and policies that will impact all College stakeholders I recognize that transparency and inclusiveness in decisionmaking and policy development can transform a culture I know that good leadership is built on trust and open communication I understand that the faculty must be part of the decision-making process, know how and why decisions are made so they can support and value those decisions and be invested in the change Obviously, there will be times when difficult decisions are necessary and consensus is not possible, but honesty and transparency in the process builds understanding even if the policy or decision is unpopular Change is hard, but strategic growth is good

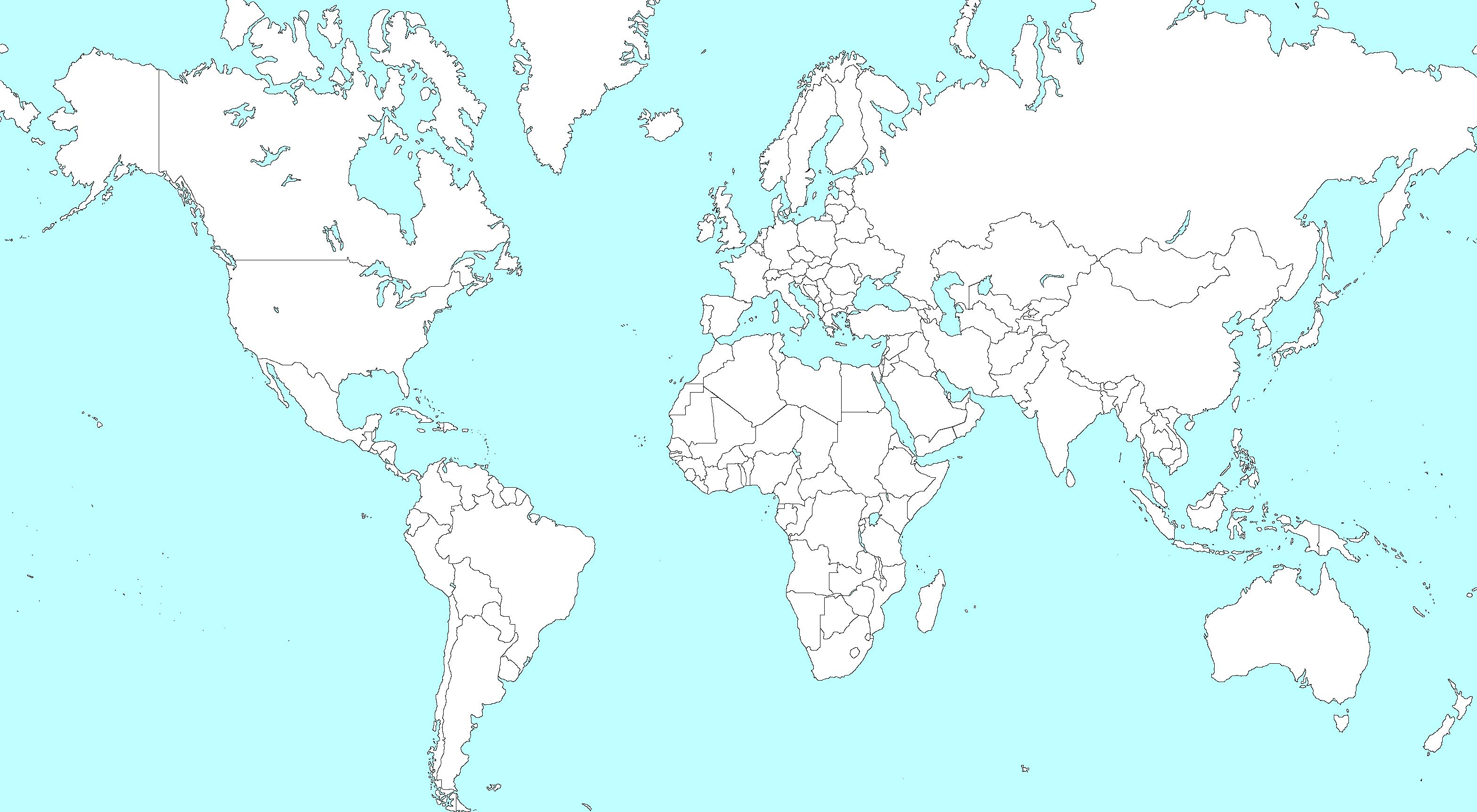

The College to be well-positioned to expand its impact in teaching and research through committed faculty, close personal attention provided to all students, engagement with innovative strategies, academic and clinical research opportunities and expansion of program offerings while recruiting students from every corner of the globe. Working together with Dean Emeritus O’Kelly, I look forward to the future.

It’s good to be back in the editor’s chair at The Compass. That chair is currently in Nairobi, Kenya, as I begin my second transect of Africa as a U.N. contract medical trainer.

CoROM has boomed during my sabbatical, and I anxiously await returning to Malta to help deliver another TTEMS course in April. Beyond assisting with CoROM’s CPD courses, I hope to begin collaboration soon on the long overdue 3rd edition Remote and Austere Medicine Field Guide for Practitioners.

I would like to personally welcome John Clark to the CoROM faculty I have known John for several years and I know he will do an outstanding job as Executive Dean

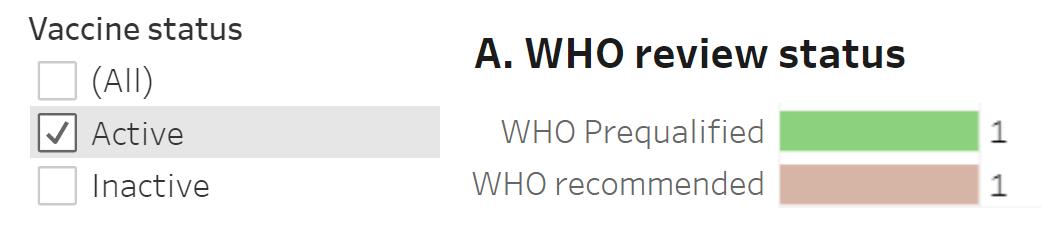

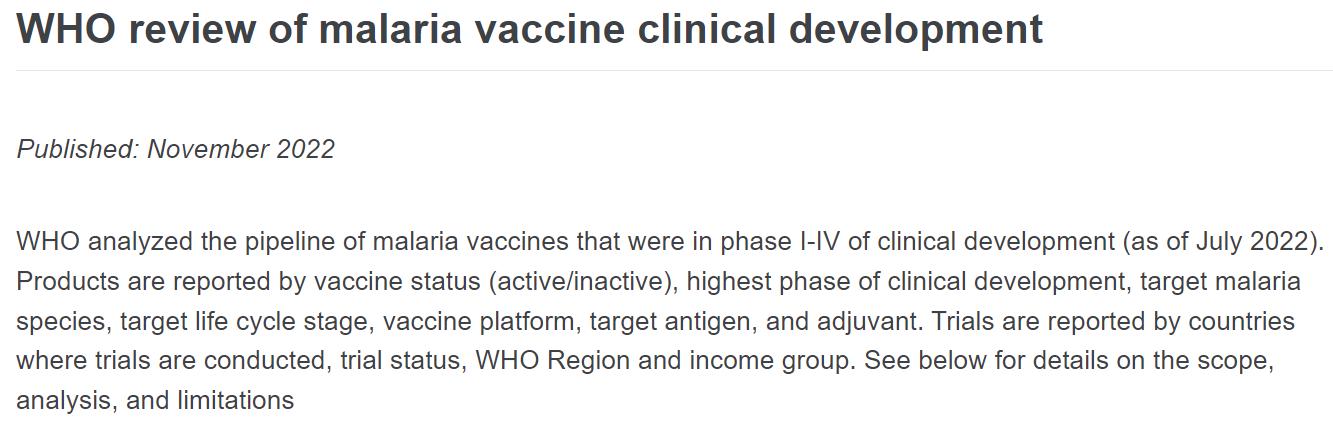

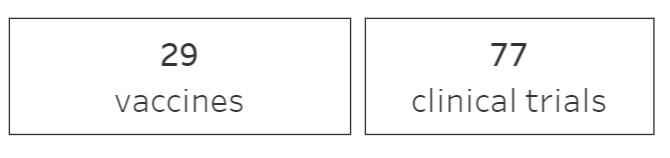

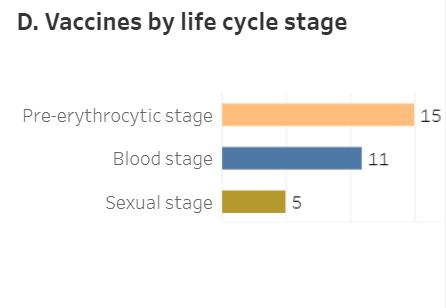

In this issue we have a Special Report on digital documentation from CoROM instructor (and one of my favorite Norwegians) Eirik HolmstrØm. This issue also marks the first instalment of Tropical Medicine Updates, with an infographic on the current state of malaria vaccine development. As for the Book Review, I was so impressed with Doug Stanton’s novel In Harm’s Way that I decided to review his Afghanistan war story Horse Soldiers for this issue. I was not disappointed.

Jason Jarvis is CoROM’s Press Chair and associate lecturer in Tropical Medicine. He is a paramedic and former U S Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan He recently completed his first transect of Africa, teaching deployment medicine courses for healthcare providers in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya under the auspices of the United Nations Based in Seattle, Jason is a freelance medical educator who teaches advanced trauma courses, minor surgical procedures, ACLS, and PALS. He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for International Health, and is pursuing a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

The medical community has made tremendous progress with regards to evidence-based medicine for treating trauma in both military and civilian settings. Research, investigation, and documentation have improved both our treatments and training.

An enormous amount of research and protocols for trauma management has been developed by the Joint Trauma System (JTS) during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. My personal observation has been that the military “pushes the envelope” out of necessity and their lessons learned trickle down to civilian medicine practice some years later.*

A prime example of this pushing of the envelope is the creation of the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) system in the 1990s, and the way this system redefined our concept of battlefield preventable deaths. TCCC freed us from the traditional “ABC” sequential approach (airway, breathing, circulation) and gave field medicine providers the scientific backing to instead approach the battlefield casualty using the “MARCH” sequence (massive hemorrhage, airway, respirations, circulation, head injury, hypothermia).

Other examples of military trauma pioneering include the aggressive use of tourniquets in cases of catastrophic extremity haemorrhage, the use of tranexamic acid for uncontrolled hemorrhage in the prehospital setting, not using crystalloids as the sole replacement fluid for hemorrhagic shock, and devising plans and protocols to administer whole blood in the field

TCCC is now the standard of care for all combatants (not just medical providers) within NATO. Tactical Emergency Casualty Care is a “spinoff” of TCCC that is in wide use among civilians, and the JTS’s Prolonged Field Care clinical practice guidelines have now been transformed into a civilian training model known as Austere Emergency Care (AEC).

“SAFE MARCH PAWS” is the version of MARCH being taught by the U.N.

* Editor’s note:

“If you wish to become a surgeon, follow an army.”

-widely attributed to Hippocrates

During my years of training, education, operations, and deployments within various services I have seen firsthand the effects of failure to maintain continuity of casualty information.

At the same time, I have seen that I could have been better prepared to maintain this information continuity, and that I could have provided a better job in my role as a medic and as a provider of information to my higher command

I have read some papers discussing the documentation flow from point of injury to the final treatment facility, and the common criticism that runs throughout these papers is the lack of information flow. Most of the patients arrived at hospitals with little to no record of prior treatment.

Is this a problem? Let’s look at what is essential for survival and patient’s outcome down the line. In NATO we have today implemented a standard TCCC field casualty information card. The casualty card has been a major contribution to assisting us in retaining and focusing on vital casualty information.

The challenge is twofold: 1) getting a medic to actually fill out the card during the stress of combat; 2) keeping the card reasonably free of dirt and blood so that it can be read. As a flight medic in Afghanistan from 2010-2012, I don’t recall getting a single casualty card that provided me the information I needed. With full respect to the heroism of the ground medics, after casualty handovers I could not read their muddy and blood-spattered cards in the back of the helicopter.

The inability to read the casualty’s card meant that I had to start the MARCH assessment all over as if it was the initial assessment

Without the vital information contained on a casualty card, I did not know which (if any) treatments had been done and most important, had the patient received any drugs? Had the casualty with chest wounds been decompressed already? Had any other treatments been attempted before I received this patient? Yes, this lack of documentation was – and is – a major problem.

Let’s look at other military units and civilian entities who needs documentation for their work. I am referring to forward air control, breachers, EMTs, and almost all of the military and civilian medical services. Most of them have gone digital whilst medics in military, offshore, remote and austere environments are still using pen and paper.

I am involved in a company called P3D medic (disclaimer) who have developed a digital TCCC app with additional possibilities. I know there are a couple of other system out and in the making that are also worth looking at.

This article is not for favoring any system, but to get medics interested in a system that ensures patient treatment is submitted up the chain of treatment with the patient, or digitally sent as soon as possible to the receiving facility

My generation is almost certainly more reluctant to implement digital systems than younger generations. I did a workshop for P3DMedic Tool in Germany last year and the younger generation – as you might expect - did not need any introduction or explanation to the system.

We are going digital on all our platforms, why not medical?

Getting correct information throughout the chain of treatment is self-explaining for patient outcome, but one of the most important benefits is statistics

Statistics is the cornerstone of evidence-based medicine, and this is what we can help develop if we can manage to get the detailed information from the point of injury up the chain of treatment following the casualty.

Medics need to get digital on reporting, it’s as simple as that.

While working in Afghanistan as an independent contractor, you are asked to see an 18-year-old Peruvian male security contractor who has been moderately ill for the last forty-eight hours

He states he began having generalized abdominal pain, a global throbbing headache and decreased appetite two days ago. Subsequently, he developed fever to 38.8 C, N/V and significant fatigue. He has lost no weight and had no diarrhea.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D MD DTM&H

His unit has been at the current location for one month There have been several other ill security contractors recently, but none were very ill and the unit commander thought it was “a flu ” Your patient has not had contact with the ill individuals His area of operations has no known malaria and he had no malaria contacts pre-deployment

There are no stray animals or livestock within the compound, nor does the security contractor have contact with animals. He received all his Peruvian mandated military vaccinations pre-deployment. He denies local sexual contacts, any drug use, and eats only the Peruvian rations issued by his unit.

After your evaluation of the patient you are somewhat concerned. His vomiting is difficult to control, requiring IV fluid intermittently. His abdominal pain becomes more epigastric focused, which he describes as a severe bloating. With 1 gram acetaminophen / paracetamol every six hours his headache and fever improve.

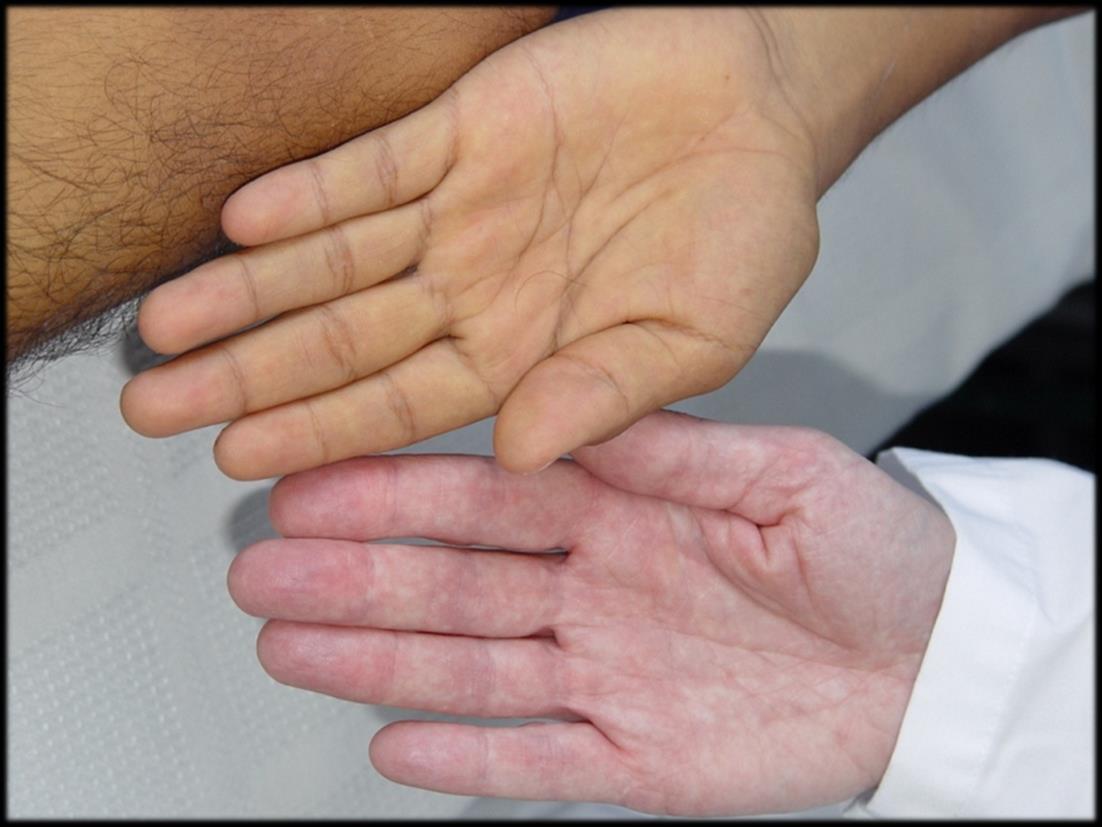

On his fourth day of illness - while you are seriously considering medevacing him to higher medical authority - his fever abruptly ceases and his appearance changes dramatically (see photo below).

What is his likely diagnosis, how is it managed, is it contagious, and does he need to be evacuated?

He has acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) which is a virus transmitted by oral fecal contamination. It has a 2-6-week incubation period and the potential for causing widespread epidemics, particularly when it contaminates an untreated or inadequately chlorinated water supply.

Residents of developing nations usually acquire this infection naturally between 2-3 years old and have minimal symptoms. Severity generally increases with age with a death rate over 2% in patients over the age of 50. Generally, residents of the U.S. born before WWII II are considered immune since it was widespread in that era secondary to sanitation practices.

Once infected, patients excrete virus in their stool and are infectious for about 2 weeks before they develop symptoms until about 1- 2 weeks after they develop jaundice Typical symptoms include an abrupt onset of fevers, fatigue, malaise, anorexia, and N/V, all of which occurs in >60% of adult patients After several days symptoms give way to jaundice and the fever resolves Jaundice generally resolves about a month after symptom onset Treatment is purely symptomatic, but post-HAV convalescence may include months of malaise, fatigue, and anorexia Although he doesn’t have to be sent home to recover, he may be on light duty or less for a month His stool is infectious as outlined above, but with proper sanitation and hand washing he shouldn’t get anyone else sick

A very effective vaccination is available for HAV; however, it is expensive and used only in developed countries since residents of developing nations generally acquire this disease and resulting immunity as young children. The currently recommended two shot series likely provides lifelong immunity. Any U.S. citizen traveling aboard should have this vaccine. Currently, vaccination for hepatitis A is common in the U.S. and very effective in preventing the infection. Traditionally only a few U.S. states actually required this vaccination for school children. All travelers to the developing world should ensure they are vaccinated before travel.

In several studies of travel-associated fever, HAV was one of four major causes along with malaria, typhoid fever, and influenza Most foreign militaries use different vaccination schedules than the U S does, rarely including HAV vaccine

Epidemic jaundice has been noted in military campaigns since the Middle Ages through the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. During WWII, General Rommel was medevac'd from North Africa for HAV. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, they were aware of significant ground water contamination with typhoid, HAV, and cholera, among others. Subsequently, they made water decontamination and distribution to the troops a top priority. However, in October through December of 1981, the entire Soviet 5th Motorized Rifle Division was rendered combat ineffective when over 3,000 of its personnel (over one-quarter of its strength) were simultaneously stricken with HAV. The sick included the division commander, most of his staff, and two of the four regimental commanders. This outbreak was traced to the young Soviet enlisted personnel’s distaste of the heavily chlorinated water.* Subsequently they would drink untreated water, usually at their base camp. Overall, the Soviets had 115,000 cases of HAV during their time in Afghanistan.

Although our Peruvian security contractor had ample access to properly chlorinated water, you’d have to ask him whether he drinks untreated water. He would tell, as you already expected “the treated water tastes like bad* , so he and his buddies drink untreated whenever they find ”

Hepatitis A virus is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus with linear nucleic acid structure and icosahedral capsid symmetry. It is in the picornavirus family, whose members include poliovirus, echovirus, the rhinoviruses, and coxsackievirus.

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former US Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

* Editor’s note: The taste of drinking water that has been disinfected with chlorine can be improved by adding a pinch of ascorbic acid per liter of water.

https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/monitoring/who-review-ofmalaria-vaccine-clinical-development

vaccine

Targets the preerythrocytic stage

ChAd63-MVA PvDBP (ongoing)

Pfs25M-EPA/AS01B (completed)

PfSPZ (completed)

PfSPZ-Vac (ongoing)

PvCSP/ISA-51 (completed)

PvDBP/Matrix M1 (ongoing)

PvSPZ (completed IIa)

Rh5/AS01B completed IIa)

Blood stage parasites

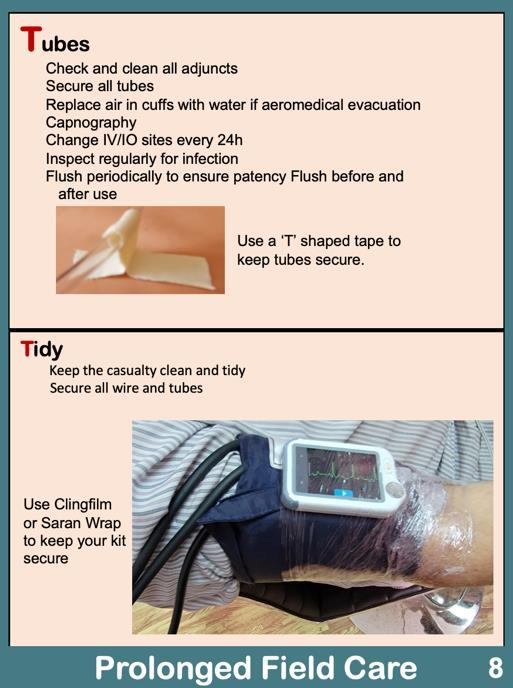

In critical care, we have a lot of sophisticated medical “toys”, and often have lines and electronic leads running all over the place. I have no idea how often I have stepped on an IV line, a BP cuff line, or an electrical lead whilst treating my casualty. Sometimes these mishaps don’t cause problems, but oftentimes they do, such as detaching an SpO2 meter or pulling the BP cuff pipe out of the BP cuff or a thousand other things.

Be better.

You can use improvised equipment to tidy up your casualty and make your “office space” clean, clear and safe. I like to use clothes pegs or metal paper binder clips to gather up all the loose 12-lead cables and anything else that can get in the way.

Clothes Pegs

Growing up in the U.S., we called these things ‘clothes pins.’ Here in the EU, we call them pegs. Same device and an excellent option for you to have in your kit. They can be used to hang things on a line strung across your austere clinic, and they can be used to collect 12-lead ECG leads, so the leads don’t look like spaghetti.

Cling Film

This is called Saran Wrap in the U.S. It is an excellent option for burn coverings and for securing IV lines. But you can use 20cm lengths as ties for keeping lines/leads in place. You lose serious cool points if you do not have a half-roll of cling film in your kit. Use a pipe cutter to cut a standard kitchen roll in half, making it easier to manage.

Binder Clips

I have seen these used as a clothes peg for keeping 12-lead lines in check. They tend to slide up and down the line/lead unless you also clip some of the bed fabric. This works nicely and holds onto the fabric better than a clothes peg.

Take home message

Once you have stabilised your casualty, take a moment and tidy up your office space

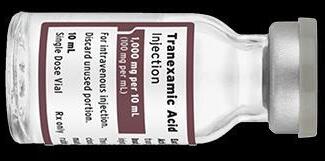

“Changes are written in blood,” the old adage goes, and has perhaps never been truer than in the case of the excruciatingly slow adoption of tranexamic acid by Western medicine. First synthesized in Japan in 1962, this life-saving drug remained largely unappreciated for decades until 2009, when it was added to the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NR-Paramedic PGCert Infectious Diseases

In 2011, the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care recommended tranexamic acid (TXA) be administered immediately to battlefield casualties suffering from uncontrolled hemorrhage. However, the biggest impediment – by far – to immediate administration of the drug lies in its mode of administration, the intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) route.

In true pioneering spirit, efforts have been underway to challenge the idea that TXA can only be given intravascularly for uncontrolled bleeding Aside from certain surgical and dental procedures, the two major patient cohorts for which TXA is highly desired are traumatic casualties and women suffering from postpartum hemorrhage (PPH)

Both the CRASH-21 and WOMAN2 clinical trials demonstrate the efficacy of TXA in trauma and PPH; however, in many parts of the world establishing vascular access can be significantly delayed (as in a tactical military or law enforcement setting) or unavailable (midwives working in resource-poor areas).

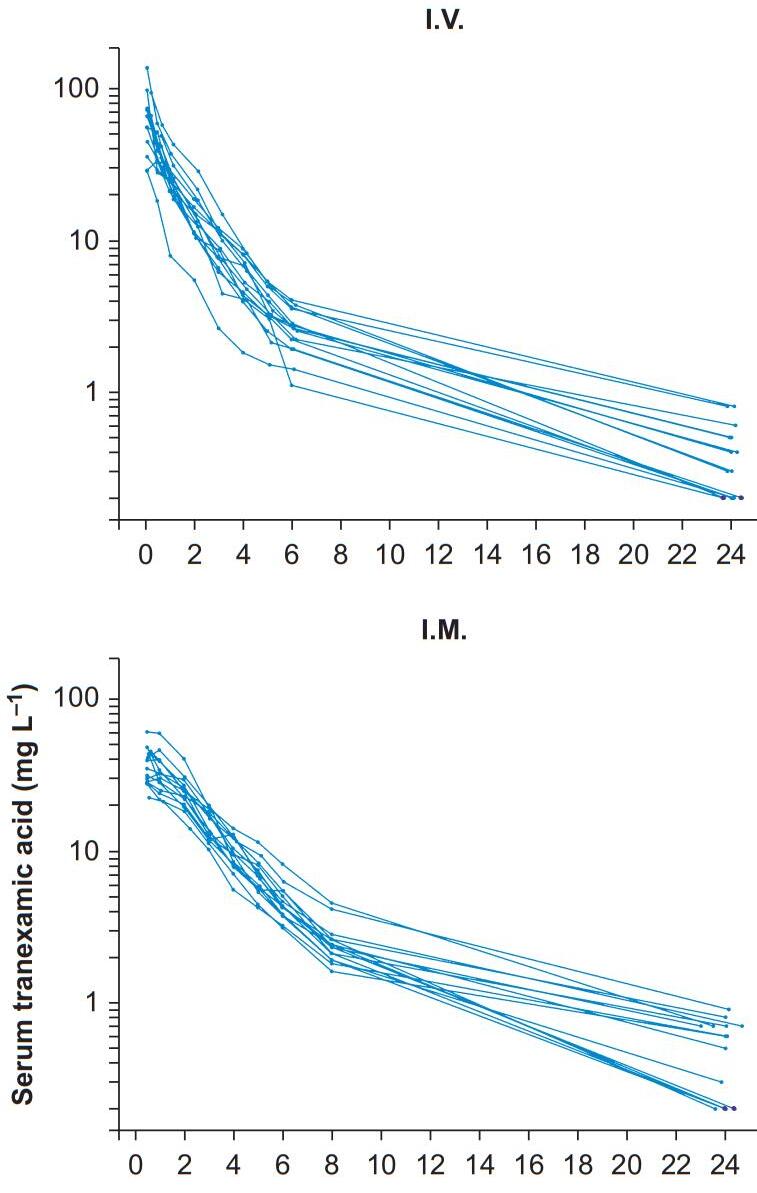

Grassin-Delyle et al recently conducted research on the pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid given via intramuscular (IM) injection. Their findings were published in the British Journal of Anaesthesia in January of 20223 , the key figure of which is found on the following page.

A brief literature search reveals that this research was bookended by an animal study on the efficacy of IM TXA in patients in shock4 (2019 Journal of Special Operations Medicine) and a 2022 case report in Emergency Medicine entitled “Intramuscular Tranexamic Acid Administration on the Battlefield”5 . Both of these articles make a persuasive case for the adoption of this practice. Indeed, efforts are already underway in the U.S. to design a TXA autoinjector device.

1 CRASH-2 clinical trial

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21702233/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28456509/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34998508/

Grassin-Delyle S, Semeraro M, Lamy E, Urien S, Runge I, Foissac F, Bouazza N, Treluyer JM, Arribas M, Roberts I, Shakur-Still H. Pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid after intravenous, intramuscular, and oral routes: a prospective, randomised, crossover trial in healthy volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 2022 Mar;128(3):465-472. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.054. Epub 2022 Jan 5. PMID: 34998508.3

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31910476/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9584727/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34998508/

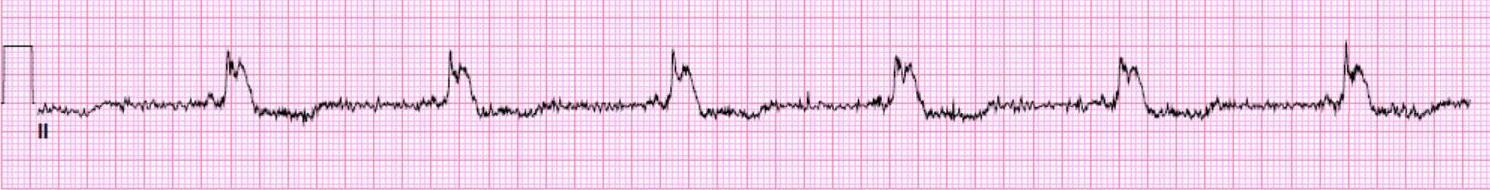

Following an unsuccessful nighttime raid on your security compound in Ukraine, you arrive in your clinic to find your junior medics performing CPR on a wounded soldier. What does the casualty’s pre-arrest ECG tell you is the most likely cause of the cardiac arrest?

A. Hypoxia

B. Hypothermia

C. Cardiac tamponade

D. Tension pneumothorax

While on a United Nations peacekeeping mission in Ethiopia, a male farmer presents to your clinic with a case of fungal mycetoma of the left foot. As you do not have a sufficient stock of antifungal medicine, you decide to surgically debride the infected tissue. In preparation for this procedure, you draw up 150mg of 0.75% bupivacaine to administer posterior tibial and sural nerve blocks. What volume of bupivacaine will you draw up?

During a wilderness expedition in Borneo, one of your teammates is found comatose in his hammock at 0600. The patient’s heart rate is 110, temperature is 40.5° Celsius, blood sugar is 2.0 mmol/L (36 mg/dL), and serum lactate is 4.6 mmol/L. Fundoscopy reveals the image below. What is your working diagnosis at this point in your investigations?

A. Hemorrhagic stroke

B. Intoxication with methyl alcohol

C. Malaysian pit viper envenomation

D. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria infection

Medical References (editor’s picks)

EOlife X

available at Archeon Medical

EOlife X is a CPR manual ventilation training device.

EOlife X teaches about airway management and good ventilation regardless of the user’s level of experience and the type of patient treated.

EOlife X gives feedback on leaks and its bar graph displays the volumes inhaled and exhaled in real time, teaching you how to:

– Position and seal the mask more effectively

– Use the jaw-thrust manoeuvre correctly to avoid insufflation of air into the stomach

– Intubate successfully

Real-time visual feedback increases the quality of manual ventilation by 70% and reduces the risk of hyperventilation tenfold.

BMC Anesthesiology

Kuchyn I, Horoshko V.

2023 Feb 7;23(1):47.

doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-02005-3.

METHODS

The treatment of 769 patients was analyzed Pain intensity was diagnosed using a visual analog scale (VAS) To detect neuropathic pain, the Douleur Neuropathique 4 questions (DN4) The presence of an acute stress reaction (ASR) was diagnosed using The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) and medical history, the diagnosis was established by a psychiatrist Satisfaction with treatment results was studied using the Chaban quality of life scale (CQLS) Group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney test and the chi-square test, taking into account continuity correction

Patients with gunshot wounds have a high risk of chronic pain, averaging 45% higher than the general population in civilian trauma patients. A greater frequency of the neuropathic component of pain and acute stress reactions is the reason for such chronicity. A decrease in the level of satisfaction with the results of treatment, in the remote period of observation, compared to the level at the time of discharge from the hospital, is probably a consequence of the formation of chronic pain.

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine

Wray JN, et al.

2023 Feb 18:S1080-6032(22)00220-4.

doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2022.12.005. Epub ahead of print.

METHODS

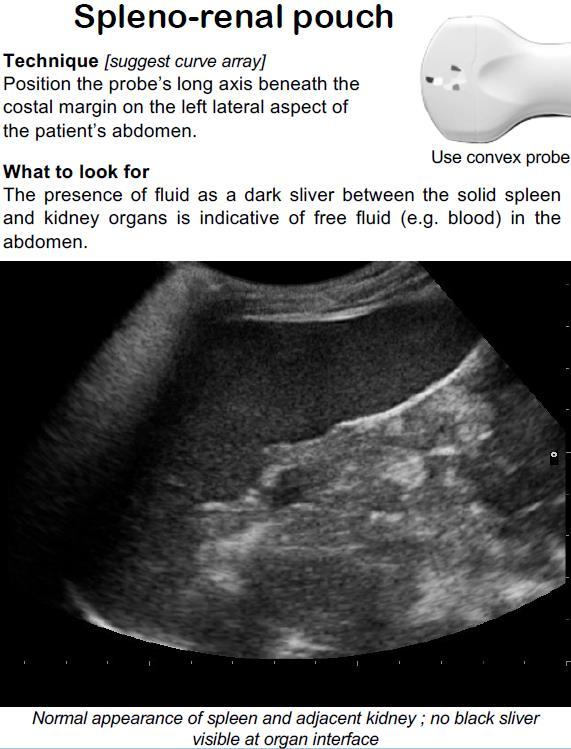

A noninferiority study compared 9 products to commercial gel. Each substance was independently tested on 2 subjects by 2 sonographers covering 8 standardized ultrasound windows. Clips were recorded, blinded, and independently graded by 2 ultrasound fellowship-trained physicians on the ability to make clinical decisions and technical details, including contrast, resolution, and artifact. A 20% noninferiority margin was set, which correlates to levels considered to be of reliably sufficient quality by American College of Emergency Physicians' guidelines. The substances included water, soap, shampoo, olive oil, energy gel, maple syrup, hand sanitizer, sunscreen, and lotion.

Of the 9 substances tested, 8 were noninferior to commercial gels for clinical decisions. Our study indicates that several POCUS gel substitutes are serviceable to produce clinically adequate images.

StatPearls Publishing

Napier A, et al. 2022 May 29.

PMID: 30725622.

The supraorbital nerve block is a procedure performed to provide immediate localized anesthesia for a multitude of injuries such as complex lacerations to the forehead, upper eyelid laceration repair, debridement of abrasions, or burns to the forehead, removal of foreign bodies, or pain relief from acute herpes zoster. A regional block allows for minimal anesthetic use, which permits the operator to obtain the intended anesthesia over a larger surface area versus that of local infiltration. The smaller anesthetic volume used also allows for minimal dissemination of anesthetic into tissues, which will prevent the distortion of normal anatomy during the intended procedure. This procedure requires knowledge of appropriate anatomical landmarks and minimal equipment.

The recognition of the appropriate anatomy for this procedure is critical, as it is landmark-based. The supraorbital nerve is one of the terminal branches of the trigeminal nerve. The trigeminal nerve divides into three branches: the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3). The supraorbital nerve is a branch of the ophthalmic nerve. This sensory nerve branches into two separate terminal branches, known as the smaller supratrochlear nerve and the larger supraorbital nerve. The supraorbital nerve exits the cranium through an opening above the orbit known as the supraorbital notch or supraorbital foramen which lies within the medial one-third of the supraorbital margin

Pediatric Clinics of North America

Gupta S, Smith L, Diakiw A. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2022 Feb;69(1):79-97.

doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2021.08.003.

Although rare in the developed world, amebiasis continues to be a leading cause of diarrhea and illness in developing nations with crowding, poor sanitation, and lack of clean water supply. Recent immigrants or travelers returning from endemic regions after a prolonged stay are at high risk of developing amebiasis. A high index of suspicion for amebiasis should be maintained for other high-risk groups like men having sex with men, people with AIDS/HIV, immunocompromised hosts, residents of mental health facility or group homes. Clinical presentation of intestinal amebiasis varies from diarrhea to colitis and dysentery. Amebic liver abscess (ALA) is the most common form of extraintestinal amebiasis. Various diagnostic tools are available and when amebiasis is suspected, a combination of stool tests and serology should be sent to maximize the yield of testing. Treatment with an amebicidal drug such as metronidazole/tinidazole and a luminal cysticidal agent such as paromomycin for clinical disease is indicated. However, for asymptomatic disease treatment with a luminal cysticidal agent to decrease chances of invasive disease and transmission is recommended.

America’s military response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks followed the core tenets practiced by SWAT teams worldwide: speed, surprise, and violence of action.

Not long after the dust had settled in Manhattan and the Pentagon, Afghanistan was infiltrated from the north by a 12-man team of U S Special Forces soldiers The team inserted covertly via helicopter by way of Uzbekistan, and were immediately installed onto horses as a means of transportation by the U.S.-friendly Afghan Northern Alliance.

These American “horse soldiers” teamed up with their Afghan counterparts (who had been fighting the oppressive Taliban regime for many years) and rained airstrike upon airstrike upon the common enemy

Despite having undisputed air superiority over the Taliban, ground fighting occurred all too often, and the myriad skillsets of the American soldiers were put to the test, not least of which was their medical expertise.

“Doug Stanton’s Horse Soldiers is the story of the first large American unconventional warfare operation since World War II My Green Berets were launched deep into enemy territory to befriend, recruit, equip, advise, and lead their Afghan counterparts to attack the Taliban. The Horse Soldiers succeeded brilliantly with a highly decentralized campaign, reinforced with modern airpower’s precision weapons, forcing the Taliban government’s collapse in a few months Doug Stanton captures the gritty realities of the campaign as no other can.”

- Geoffrey C. Lambert, Major General (retired), U S Army, commanding general of the U.S. Army Special Forces Command, 20012003

One medical case that stood out to me in particular was an Afghan teenager with a very recent gunshot wound to the abdomen The Special Forces medic proceeded to pack the wound with gauze before telling the many Afghan onlookers that he had done all that he could and that the boy needed a higher level of care elsewhere.

I was initially confused by his choice of medical care, as this medic and I had attended the same schoolhouse, and the two trauma-related directives I remembered best from my training were “Never sew up gunshot wounds,” and “Never pack the abdomen with gauze ” As I reflected, however, I recalled the recommended field plan of care for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) In cases of SIDS, in which an infant is unquestionably and irrevocably deceased with no hope of revival, medics are taught to attempt resuscitation regardless of the futility of their efforts – it is for the sake of the family in attendance that resuscitation is carried out on scene and on the way to the hospital.

I salute the medic in this case who had the situational shrewdness to pack an abdomen with gauze despite being told a thousand times to never perform such a procedure.

As the early stages of World War One shone a spotlight onto the technological transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, the events of Horse Soldiers created a similarly fascinating historical estuary between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In the former conflict: horseback cavalry in suits of armor leading saber charges against machine guns; in the latter conflict: horse soldiers using satellite radios to call airstrikes onto their foes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=arxKhJIjIiY

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority. License No. 2018-022.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments

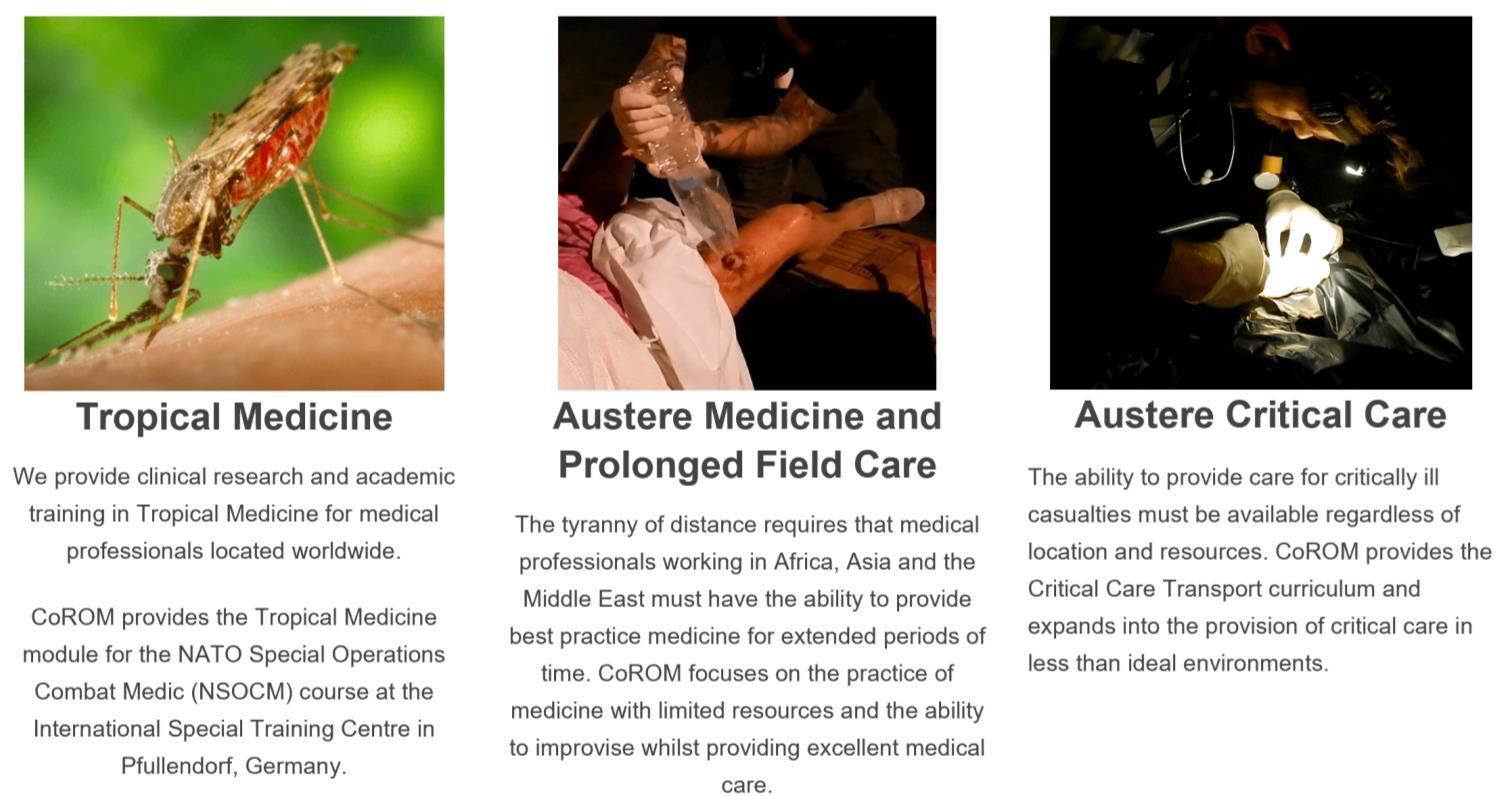

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources.

CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

MFSLR

Dates TBD

TTEMS (closed course) 29 May – 9 June

NORTH CAROLINA

SOMSA Conference 15-19 May

Tactical Medicine Review (O’Kelly)

Degree Programmes

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice

Doctor of Health Studies

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Ghana National Ambulance Service

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine

Dates TBD

ACC Acute Critical Care

AEC Austere Emergency Care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS

Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical

Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.edu.mt

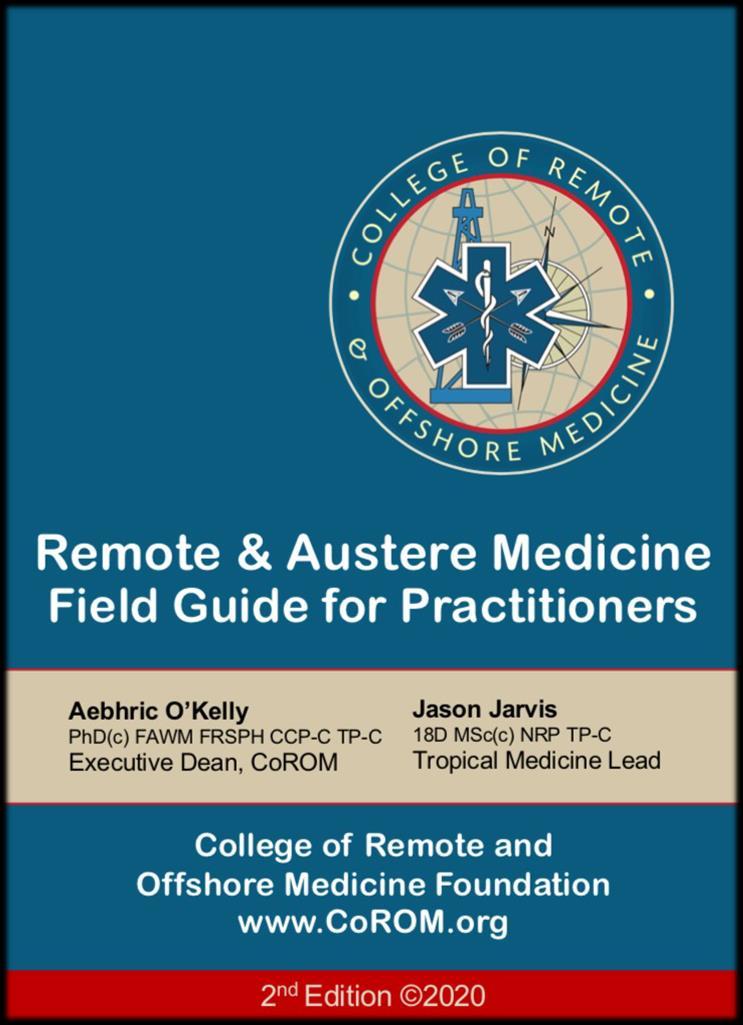

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

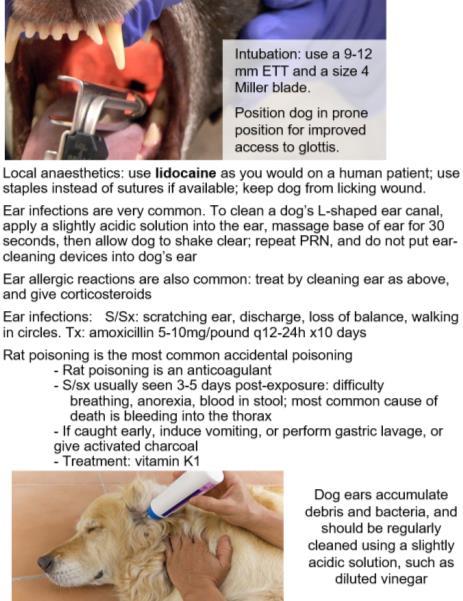

Canine medicine

…and much more!