Spring 2022

The College has started the Spring 2022 term stronger than ever. We have nine delegates enrolled on our new Doctorate in Health Studies. This programme is unique in that we have focused this programme on the experienced healthcare professional. We do not accept applications unless we see years of experience from the applicant. The BSc, MSc and MGH programmes are also moving along nicely. The new PGDip Tropical Medicine and Health will officially launch for the Autumn 2022 semester.

The current pandemic seems to be smoothing out a bit, and we are delighted to reintroduce our classroom training in May and June. We will run the BSc Remote Paramedic Practice modules for years one and two. We have external delegates coming to Malta for the Tropical Travel and Expedition Medical Skills course and our critical care programmes.

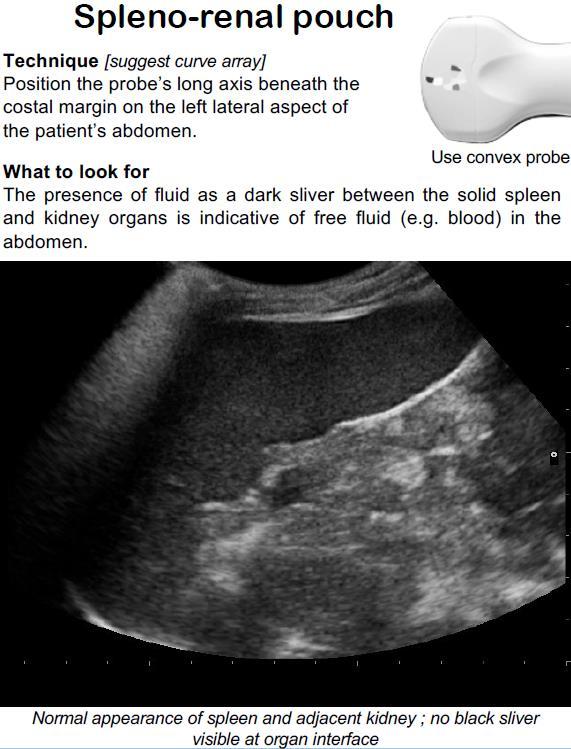

This year, we launched our ultrasound programmes. The Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound (APUS) course is based on the textbook of the same name, and it focuses every lecture on the practitioner working in remote areas of the world.

On a personal note, I was invited to the Big Sick conference run by Air Zermatt It is a small cohort since they only accept 85 delegates, and I was fortunate to have a place There were delegates from four continents attending

The College continues to move from strength to strength. This is due to the faculty who have been fantastic with student development and course design. We are only as strong as the team that we work with. It is an honour to lead these amazing professionals.

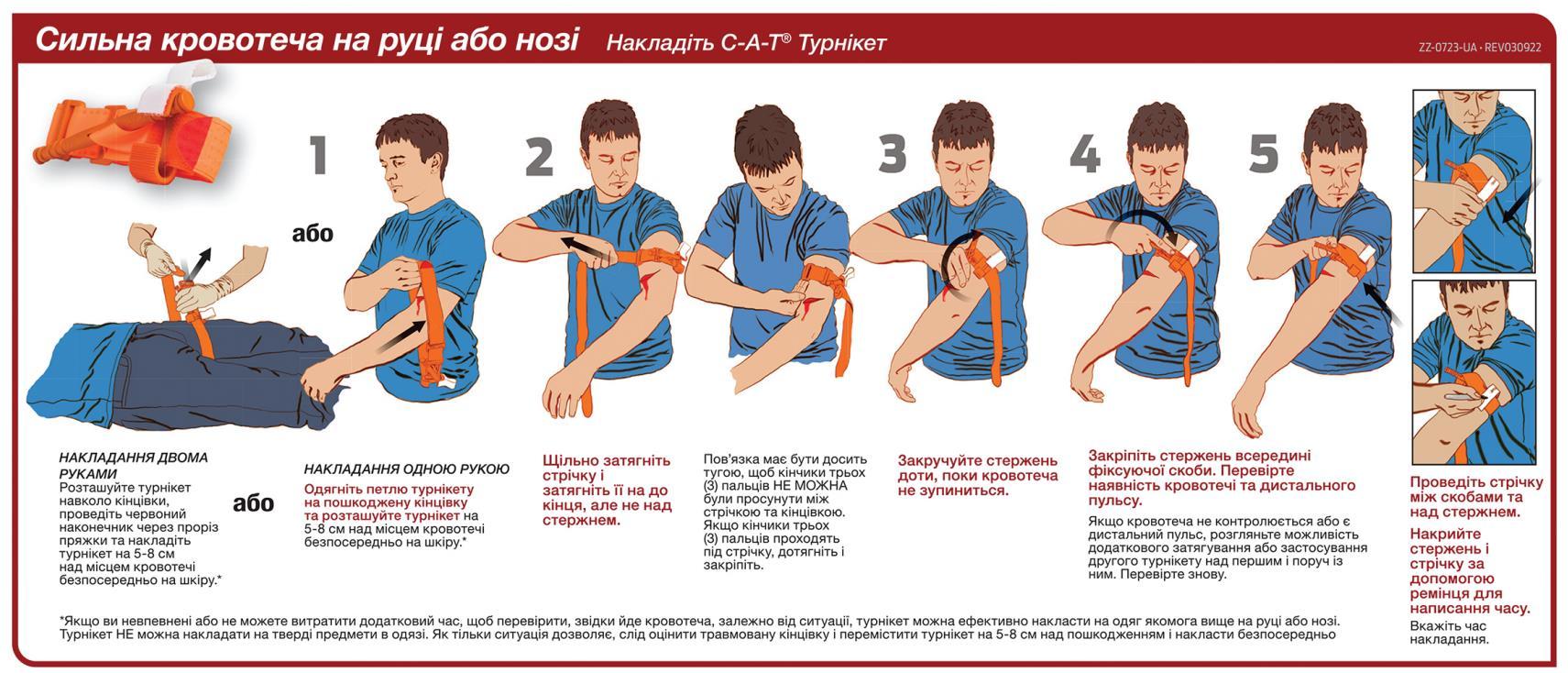

As I wrap up this edition of The Compass, I am thinking of all of the Ukrainians embroiled in the very thing CoROM specializes in – field care of casualties. The situation in Ukraine is evolving rapidly and no one knows what will happen next, but I do know that there are many brave medical providers toiling tirelessly there, and there are many, many more on their way to that beleaguered country to lend what assistance they can.

In order to help in some small way, I have included a Ukrainian language infographic on hemorrhage control on page 9 of this issue. Additionally, I have included a link to Dr. Bohdana Pereviznyk’s recent U.S. media appearance; she is an anaesthesiologist in Ternopil, Ukraine, and has been a valuable link for CoROM in delivering medical training to Ukrainians.

I am excited to have two other U.S. Special Forces Medics contributing to the pages of this newsletter – CoROM MSc student Dennis Jarema, an instructor at the Special Forces Medic schoolhouse at Fort Bragg and host of the Prolonged Field Care podcast – and long-time Compass contributor Dr. Shertz, with another interesting clinical case report from abroad. Postgraduate faculty member Dr. Aslanidis shares his motivation for joining the CoROM family in the Faculty Spotlight section.

Associate Vice President of Academic Affairs Nicole Foster shares updates on what is perhaps the most dreaded of all infectious diseases: the viral hemorrhagic fevers.

In CoROM President Aebhric O’Kelly’s Improvised Medicine piece, the research behind the ins and outs of the use of coconut water as an intravenous fluid is laid out.

The Joint Trauma System is rolling out clinical practice guidelines just about as fast as I can read them, and I chose their new Mechanical Ventilation Basics CPG as the subject of this issue’s Trends in Traumatology.

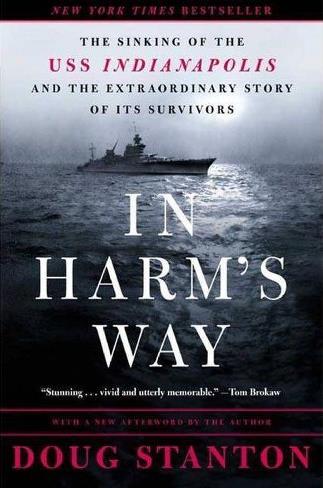

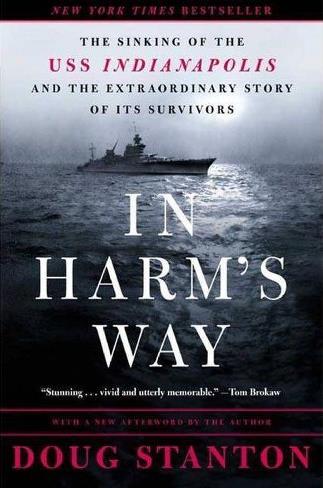

Inspired by podcaster Dan Carlin’s superb recounting of the incredible and tragic survival story of the U.S.S. Indianapolis sailors, I chose Doug Stanton’s In Harm’s Way as this issue’s book review and was not disappointed.

A series of questionnaires for CoROM students can be found on page 33, and the back cover is graced with a concept sketch of my current labour of love: CoROM’s first-ever Tropical Medicine Field Guide.

Jason Jarvis is CoROM’s Press Chair and an associate lecturer in Tropical Medicine. He is a paramedic and former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan He recently completed his first transect of Africa, teaching deployment medicine courses for healthcare providers in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya under the auspices of the United Nations. Based in Seattle, Jason is a medical educator for Virtus, Harborview Medical Center, Raider Tactical, Allied Universal, 4 Site Group, CPR Seattle, LifeTek, and Children’s Hospital of Seattle He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for the Journal of Special Operations Medicine and International Health, and is pursuing a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NR-Paramedic PGCert Infectious DiseasesDennis Jarema is a U S Army Special Forces Medic who teaches at the Joint Special Operations Medical Training Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He is a 15-year combat medic with multiple combat deployments, and is the host of the Prolonged Field Care podcast* In addition, Dennis is a registered nurse and is enrolled in the CoROM Master’s in Austere Critical Care program. He is married with three children.

This is the perfect way to get a professional degree in an area of medicine that I am passionate about. Of course there are certification courses that focus on wilderness medicine, however this is the only school that is offering an entire master’s degree curriculum that is focused on not only prehospital medicine, but delivering outstanding care in an austere and resource limited environment. The instructors that have been assembled for this program have a wealth of knowledge not only on the subject area they are discussing, but how to provide care in either a first world hospital or an austere resource limited location. That shows me that the professors actually know what to do and are not dependent on the toys.

You’re an advanced medical practitioner with a wealth of experience, what do you hope to gain from the CoROM MSc in Austere Critical Care program?

I think one of the things I’m getting from the program is a professionalization of things I’ve learned and done thus far. You find yourself speaking to a professional medical provider – usually hospital-based – and they say, “What is it you do?”

I respond with, “I’m a Special Forces Medic.”

They really only hear “medic” and they don’t know what any of the rest of that means, but they know what “medic” means and they think of “paramedic” which is at the bottom rung of their hierarchy. So usually they dumb down everything and ask you things like “Are you able to do an IV? Are you able to put on a Band-Aid?”

Currently, I do a lot of teaching in wilderness medicine. I plan on this program really amping up my knowledge base and allowing me to bring my teaching to an even higher level. Current conflicts around the world require medical providers to be capable, adaptable, and innovative in where and how they approach patient care.

So far, the experience has been great. The staff and professors have really gone above and beyond to help with any questions or issues I've had. The classes and reading assignments have really opened my view on what is possible, when it comes to taking care of patients in a resources limited environment. Being able to really discuss patient care in these situations and the hypothetical decision points really help form how I would make decisions in that situation.

At the time I was in eastern Afghanistan - fairly close to the Pakistani border – and back then they would build these launch ramps for 107mm rockets out of rocks, place the rocket, set a timer and then run away. Obviously, this ramp built out of sticks and rocks was not super-accurate, so one day, instead of the rocket hitting our compound, it veered south and hit a playground.

There were 7-8 people at the playground and only one of them made it out – a five-yearold boy. His older brother, maybe ten years old, carried him out and made it to our compound. The patient was immediately starting to posture [exhibiting signs of severe head trauma]. The guys at the gate called me so I ran down, brought the boy inside the clinic, got an open airway and got IV access. The patient was obviously bleeding inside his head, so I ran through all the traumatic brain injury treatments I had available, like hyperventilation and positioning. Unfortunately for the boy, because he was Afghani and we [the Americans] didn’t cause the injury, our rules of engagement dictated that he had reached the maximum level of care that he was going to get from us. When we called for a U.S. military evacuation of the patient, the advice we were given was to return the child to his family.

That was the hardest thing I’ve had to do as a medic. Occasionally I’ll tell this story to my medic students and explain that training to “win all the time” just isn’t a realistic part of this game.

CoROM continues to work with Ternopil State Medical University (TSMU) in Ukraine for the advancement of field medicine education

Dr Theodoros Aslanidis is a member of CoROM’s Postgraduate Faculty He received his Doctor of Medicine degree from Plovdiv Medical University, Bulgaria and his PhD degree from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. He served in the Hellenic Army Force as a medical doctor and then worked as a rural physician in the Outhealth Centre, Iraklia and Serres’ General Hospital, Greece After training in Anesthesiology, in 'Hippokratio” General Hospital of Thessaloniki, he completed his fellowship in Critical Care AHEPA University Hospital, and then Prehospital Emergency Medicine training.

Theodoros Aslanidis MD PhD

Dr Aslanidas served as EMS Physician and Emergency Communication Centre Medic at Hellenic National Centre for Emergency Care before moving to his current post as consultant at the Intensive Care Unit of St Paul General Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece. He has been an educator for EMS staff in Thessaloniki, an active ALS instructor and participates in the Prehospital Emergency Medicine program of the Hellenic National Centre of Emergency Care

During my EMS service, I realised that I needed to broaden my knowledges within the field of medicine “All-around player” was the term that came to mind This search led me to the Professional / CPD online courses of CoROM. Following that, seeking more ways to be involved in College activities was the most normal thing to do The team and the vision of the people that give life to the College and my life-long learning curiosity are the strongest motives I could have for that journey.

Literature Review. Literature (both oral and written) is our experience, our teachers’ experiences, parents and colleague’s beliefs, memories, working data files, norms, doubts, ethics and so forth. Know the history, they say, and you’ll predict the future. More importantly, you can change the future. I feel that the new Doctor of Health Studies programme (DHS) will enable candidates to develop their abilities to read critically, identify gaps, and synthesize ideas from the literature to pose their questions for future contribution to scientific knowledge and everyday professional practice

St. Paul General Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece

The COVID-19 pandemic came both as a crisis and as an opportunity. A crisis that proved that we should reform our way of education. It seems to me that CoROM’s natural field are crises. After all, crises are typically austere in character and may be remote from our usual practice. That’s why I see huge potential and I strongly believe that for the near future the college can be a reference centre in teaching and researching.

Describe a medical case that has had a lasting impact on you.

It’s hard to choose one. Yet, I remember a case of an old man, mid-70s I think, who came to the Emergency Department with a bandage in his hand. He was accompanied by his son. The man had amputated his own finger while working. His son took his finger, put it in a bag with iced water and brought it together with them to the ED. At the time the ED was overcrowded, with many people complaining about delays - a noisy, jammed, tense environment. I passed by two men rushing into the resuscitation room for a mutlitrauma road victim that just had been transferred by EMS. Unfortunately, there was nothing to do - the young man was already dead. We then had call for a second person from the same accident coming in and got out of the resuscitation room to wait It was then that I saw the two men - father and sonarguing. Suddenly, the old man took the bag with the finger, threw it into the nearby garbage bin and said loudly to his son, ”Come on lad, let’s go home There are young people dying here, to concern ourselves with trifles.” The whole environment got suddenly deadly silent; everyone just watched the two men leaving the ED. It was as if the old man talked to everyone there. It was a scene that I vividly remember.

It is hard to pick only three. There are many electronic apps and guides and they can fill almost any need. However, If I need a print format guide, the CoROM field guide is my choice.

The term 'viral haemorrhagic fever’ (VHF) refers to a group of illnesses that are caused by several distinct families of viruses. Although some types of haemorrhagic fever viruses can cause relatively mild illnesses, many cause severe, life-threatening illnesses.

VHFs are classified into the following four groups:

Arenaviruses

o Argentine hemorrhagic fever

o Bolivian hemorrhagic fever

o Chapare hemorrhagic fever

o Sabia-associated hemorrhagic fever

o Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever

o Lassa fever*

o Lujo hemorrhagic fever

o Lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM)

Filoviruses

o Ebola

Lassa virus is an example of an arenavirus. Arena is Latin for “sand” and is a reference to the sandlike appearance of the virus on microscopy.

o Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever

Ebola virus is an example of a filovirus. Filo is Latin for “thread.”

Bunyaviruses

o Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

o Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS)

o Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS)

o Rift Valley fever

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus is an example of a bunyavirus. Bunya is a reference to the Ugandan town of Bunyamwera, at which the first bunyavirus was discovered.

Flaviviruses

o Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever (AFD)

o Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD)

o Omsk hemorrhagic fever

o Tick-borne encephalitis

o Yellow fever

o Dengue

Yellow fever virus is an example of a flavivirus. Flavi is Latin for “yellow” and is a reference to the typically jaundiced appearance of those afflicted.

• Lassa Fever outbreak was reported in February 2022 in Nigeria

• Severe Dengue outbreak has been reported in February 2022 in Timor-Leste and in December 2021 in Pakistan.

• Yellow Fever outbreak was reported in 2021 in Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic (CAR), Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, and the Republic of Congo. An outbreak also occurred in Venezuela in October 2021.

• A short outbreak of Ebola occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo between October to December 2021

This article will focus on Lassa Fever (LF), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Marburg, and Ebola.

LF, Marburg and Ebola viruses are restricted to sub-Saharan Africa. CCHF virus is more widely distributed in Africa, the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Central Asia and China. The origins of Marburg and Ebola viruses are still unclear, but most cases appear to have arisen in Africa.

VHFs should be considered in the differential diagnosis of every patient with an unexplained fever who has been exposed to the infection in an area with endemic VHF during the preceding 3 weeks.

Clinically apparent infections with any of these viruses may present with similar symptoms. Fever is typically insidious in onset and accompanied by severe headache, myalgia and malaise.

Other symptoms include retrosternal chest pain, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, conjunctivitis, facial swelling, proteinuria and jaundice.

A bleeding diathesis leads to mucosal bleeding, haematemesis, melaena and haematuria

Severe infections are complicated by massive haemorrhage and multi-organ failure.

Acute onset of fever of fewer than three weeks duration in a severely ill patient and any two of the following

• haemorrhagic or purpuric rash

• epistaxis

• haematemesis

• haemoptysis

• blood in stools

• other haemorrhagic symptoms and no known predisposing host factors for haemorrhagic manifestations

• LF has a case-fatality rate of 1 percent of infected cases but 25 percent of hospitalised cases.

• CCHF has a case-fatality rate of 2–50 percent.

• Marburg has a case-fatality rate of 25 percent.

• Ebola has a case-fatality rate of 50–90 percent.

The incubation period varies according to the causative agent:

• LF virus – the range is 6–21 days.

• CCHF virus – the range is 1–12 days (usually 1–3 days).

• Marburg virus – the range is 3–9 days.

• Ebola virus – the range is 2–21 days.

• The reservoir for LF virus is a rodent known as the multimammate rat of the genus Mastomys. Mastomys rodents shed LF virus in urine and droppings. The virus can be transmitted through direct contact with these materials, touching objects or eating food contaminated with these materials, or through cuts or sores. In addition, the person-to-person transmission may occur through sexual contact or inoculation with blood.

• The reservoirs for CCHF virus are hares, birds and Hyalomma spp. of ticks. In addition, domestic animals such as sheep, goats and cattle may act as amplifying hosts. Ticks are believed to acquire the virus by transovarial transmission or from animal hosts. Nosocomial spread to medical workers in contact with infected blood or secretions has been observed. The slaughtering of infected animals is also linked to infection.

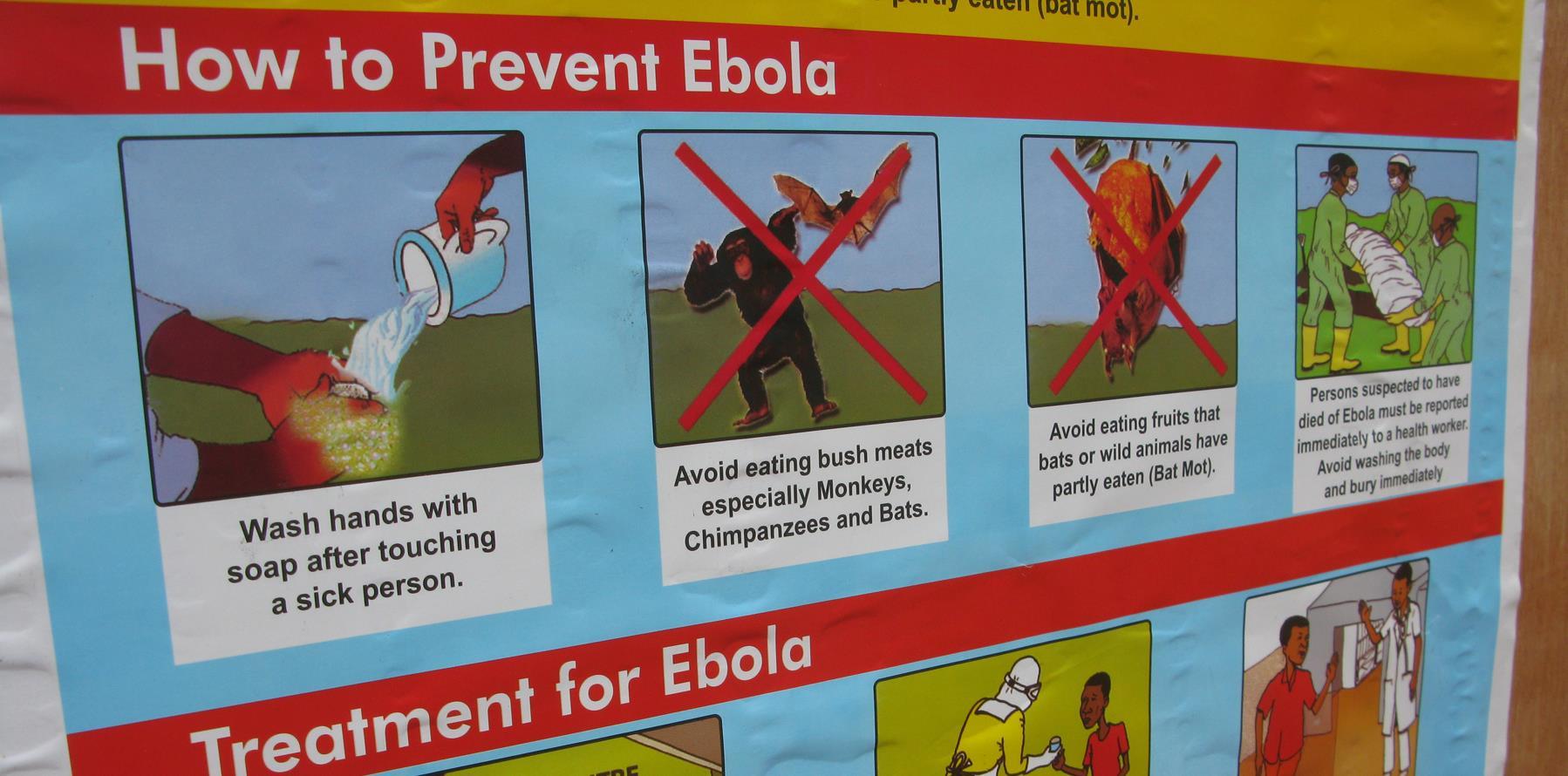

• The natural reservoir of Ebola virus is probably African fruit bats. Current evidence suggests that the virus is zoonotic (animal-borne) and is typically maintained in animal hosts native to the African continent. Outbreaks among species such as chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys and forest antelope occur from time to time. The source of infection for the index human for Ebola and Marburg viruses is usually unknown. Secondary human infections occur by person-to-person spread through direct contact with infected blood or secretions, including semen. Nosocomial transmission has also been reported through contaminated needles and syringes and sharps injury.

Communicability of VHFs depends on the infective agent:

• LF virus is communicable via person-to-person spread during the acute febrile phase. The virus is excreted in the urine for up to 9 weeks from the onset of the illness.

• CCHF virus communicability is unknown. However, the virus is highly infectious in the hospital setting, where it has been transmitted to healthcare personnel by accidental needlestick injury.

• Marburg and Ebola virus are communicable as long as blood and secretions contain the virus. The virus has been isolated in seminal fluid 60 days after the onset of infection.

Are vaccines available?

No vaccines are available, with the exceptions of yellow fever and Argentine hemorrhagic fever. As a result, the focus is on prevention.

For rodents:

• Control the number of rodents

• Prevent them from entering or living in homes or workplace

• Keep areas clean

• Immediately clean up nests and droppings when identified

• Ensure all food storage areas have rodent-proof lids and containers.

For viruses spread by ticks or mosquitoes, prevention focuses on:

• Control mosquitoes and ticks in the environment

• Wear long sleeves and long pants treated with permethrin

• Use insect repellent

• Use bed nets in areas where outbreaks are occurring

• Ensure window screens and other insect barriers are in place in accommodation

Travelling to an area where there is a risk for viral hemorrhagic fevers:

• Wear long sleeves and long pants treated with permethrin

• Use insect repellent

• Use bed nets in areas where outbreaks are occurring

• Avoid contact with livestock or rodents in areas where outbreaks are occurring

WHO - https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news

CDC - https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/index.html

Nicole Foster is the Associate Vice President of Academic Affairs and is the Undergraduate Coordinator for the College. She is a critical care paramedic and specialises in remote and austere environments. She is based in Perth, Australia.

You are providing medical coverage for a hiking expedition in the Peruvian Andes. Prior to ascending, an otherwise healthy 34-year-old trekker presents to you with acute onset of watery, non-bloody diarrhea, nausea, one episode of vomiting, abdominal cramping, and no documented fever.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D MD DTM&H

His vital signs are normal, he takes no medications, and has had no malaria or dengue exposures. He reports frequently eating at roadside stands in Lima over the last few days.

Although the differential diagnosis is broad, with minimal abdominal tenderness and no fever, traveler’s diarrhea is the most likely diagnosis.

One-quarter to half of international travelers will develop diarrhea during their trip to a low-resource destination. Generally, traveler’s diarrhea (TD) is the acute onset of loose, watery stools, abdominal cramping, urgency to stool, and occasionally fever. Nausea and vomiting are common with the onset of infection. Although a mild, self-limiting disease, the average affected traveler loses 24 hours of their trip related to their nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Most TD occurs within two weeks of destination arrival and lasts 3 to 4 days.

Etiologies for TD are generally food and waterborne exposures containing infective organisms, i.e., stool contamination. The most-identified cause of TD worldwide is the bacteria enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). It is identified in one-third of TD cases in which an organism is found. Other bacteria genera such as Shigella, Salmonella, and Campylobacter are each found in about ten percent of cases. Norovirus and other enteric viruses are found in about 15% of affected individuals. Giardia lamblia is the most frequently identified parasite causing TD but represents only 3 to 9% of all cases. Parasitic infection is much more common in protracted diarrhea (greater than 14 days) in returning travelers.

Dysentery is a form of TD but is associated with bloody diarrhea and typically fever. All dysentery is considered severe TD. Organisms like Shigella, nontyphoidal Salmonella, and Campylobacter are frequent causes.

The quantity of material necessary to infect a person with TD varies highly based on the organism. With ETEC the quantity is quite large, in contrast to Shigella which can infect with less than 200 individual bacteria. Norovirus is also easily spread from person to person.

Age seems to play a role in the likelihood of experiencing TD. Rates among 20- to 29-year-old travelers can be as high as 37%, whereas only 27% of traveler’s 40 to 49 are affected.

Although protective immunity occurs after infection with ETEC, the duration of that immunity is unknown. There is little protective benefit from prior travel to low resource locations, however travel to those locations within the last six months does seem to decrease the risk of acquiring TD.

The typical traveler food/water recommendations of “boil it, cook it, peel it, or forget it” seems to make intuitive sense as ways to avoid TD. However, the medical literature supporting this guidance is both limited and contradictory.

The most-identified cause of traveler’s diarrhea worldwide is the bacteria enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC).

Bismuth subsalicylate, Pepto-Bismol, etc., (BSS) is an effective strategy for the treatment of TD. BSS has an anti-microbial quality but can turn both tongues and stool black. Additionally, the salicylate in BSS is completely absorbed and is the equivalent of taking 3 to 4 regular strength aspirin daily. Although it does not increase bleeding risk, it really shouldn’t be taken in combination to NSAIDS or any anti-coagulants. Additionally, BSS can decrease the absorption of other drugs like doxycycline used for malaria prophylaxis.

Another option, loperamide, can be very effective in the treatment of mild TD, even without antibiotics. The initial loading dose of 4 mg can take 1 to 2 hours to become therapeutic and additional doses shouldn’t be provided until after that period.

Loperamide and antibiotic treatment of moderate TD resolves symptoms and diarrhea faster than either alone. The combination makes it 2.6 times more likely diarrhea will be resolved within 24 hours.

Antibiotic treatment of TD shortens the duration of illness. Although traditionally fluoroquinolone antibiotics like ciprofloxacin have been very effective, increasing drug resistance to these agents and the FDA black box warning secondary to tendonopathy and other side effects have limited their use. Subsequently, this led to the widespread recommendation for azithromycin instead.

Currently, single-dose antibiotic regimens have been shown to be just as effective as multi-day courses with clinical cure at 24 hours in the high 70’s% in cases of moderate TD. Severe TD or dysentery are best treated with azithromycin due to the widespread fluoroquinolone drug resistance in the causative organisms.

If diarrhea fails to resolve by 48 hours, symptoms worsen, or fever persists, the traveler should be more formally medically evaluated as a parasitic infection or numerous other etiologies could be causing the illness.

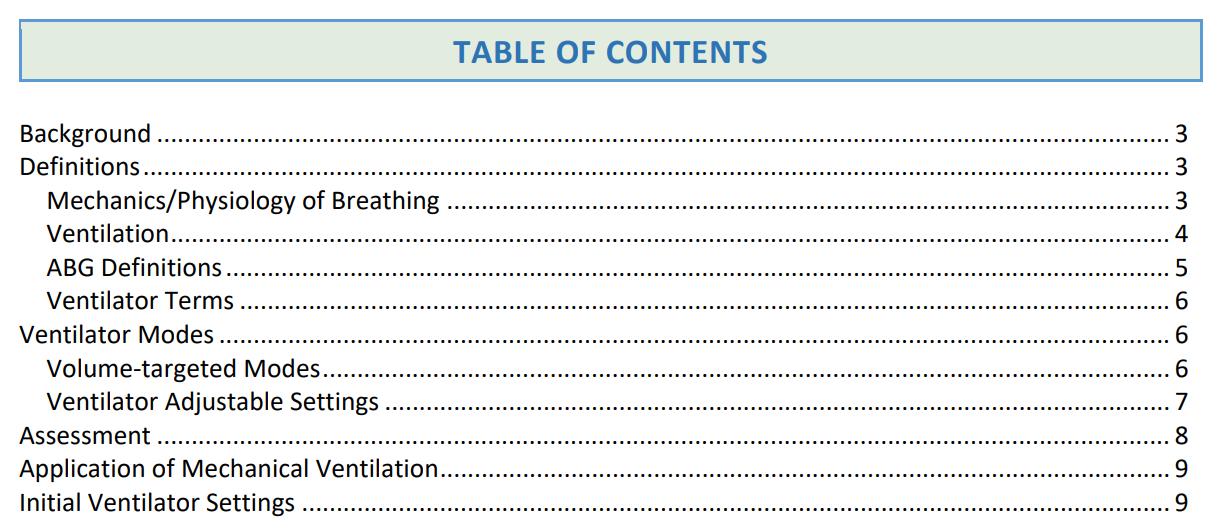

Reference: Travel Medicine, 4th Edition, Jay Keystone Editor, 2019.

Street vendor in Lima, Peru, 2003.

A 1975 study in Mexico recovered E. coli from 39% of food prepared in restaurants, 55% of street vendors, and in 40% of small grocery stores. Photo courtesy of Dr. Shertz.

There have been many case studies published on using “coconut water” to increase the intravascular volume of a patient in shock. The first publication can be found from the WWII era1. Other studies show this procedure as an effective form of IV hydration and an alternative for remote areas with limited supplies2 .

Don’t forget that there is a good, better, best option for hydration. Oral hydration is better than a coconut water IV. But the best intravenous hydration option is hospital-grade sterile IV solution. On page 133 of the CoROM 2nd edition Field Guide, we discuss alternative hydration options to the intravenous or oral routes. Dermoclysis and proctoclysis remain excellent hydration options that I would use before attempting a coconut water IV.

According to the Coconut Handbook3, one can find almost 700ml of fluid in a coconut. It contains sugar, sodium, potassium, chloride and calcium. The big red flag for me is that the pH of this fluid is around 5; normal saline has 5.5 pH, while Ringer’s Lactate is 6.5 pH. I would look at other hydration options before putting that much acidic solution into a shocked casualty.

Back to the WWII-era case study - this patient was living on Solomon Island and was dehydrated. The caregivers attempted to rehydrate the patient orally, but the patient could not swallow, so they infused 2.5 litres of coconut milk over two days. The patient survived and was discharged. No electrolyte monitoring was done.

I would hesitate before using this option, as there are far better selections listed above that are much safer. Coconut fluid is acidic, has low sodium with high potassium, and high osmolarity due to the sugar content. My guess is that the patient will urinate out most of this fluid before it can be shifted from the intravascular and into the interstitial and intracellular spaces.

Take home message: Sure, this option looks cool. Some survival experts would jump at the chance to discuss this. But do not do this. I taught wilderness survival for many years in North America and here in the EU. Don’t risk this. The research supporting this option is sparse at best. Please review our Field Guide for better alternative hydration options.

References:

1. Pradera ES, Fernandez E, Calderin O: Coconut water, a clinical and experimental study. Amer J Dis Child 1942; 64:977-995

2. Campbell-Falck D, Thomas T, Falck TM, Tutuo N, Clem K. The intravenous use of coconut water. Am J Emerg Med. 2000 Jan;18(1):108-11? doi: 10.1016/s07356757(00)90062-7. PMID: 10674546. https://dr-martins.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/07/2000_the-intravenous-use-of-coconut-water.pdf (Accessed: 26 February 2022).

3. (2022) Coconut Handbook. Available at: https://coconuthandbook.tetrapak.com/chapter/chemistry-coconut-water (Accessed: 26 February 2022).

18D

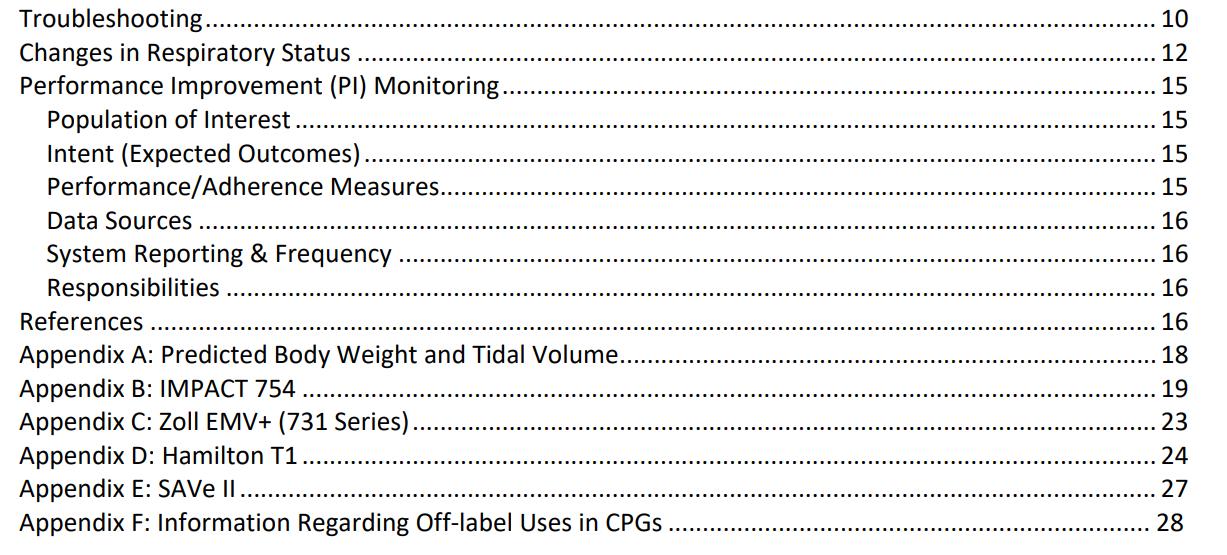

On December 27 of the previous year, the U.S. Joint Trauma System released Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) 92: Mechanical Ventilation Basics. This CPG joins the ranks of the many other useful JTS CPGs such as Prolonged Field Care, Damage Control Resuscitation, and setting up a walking blood bank.

While many field medics continue to be relegated to manual bag-valve-mask ventilation should the need arise, the mechanical ventilator is becoming more and more prevalent, particularly at the “truck-house-plane” echelons of care. In addition, the advent of portable oxygen concentrators enables much greater flexibility in the titration of blood oxygenation, especially in patients with penetrating chest trauma who may be poor candidates for high levels of positive-end-expiratory pressure.

The next few pages contain the introductory section of the CPG; the full 28-page PDF may be downloaded at the link below.

Instructions on using the SAVE II ventilator is found in Appendix E of the new JTS Mechanical Ventilation Basics CPG.

Your patient is exhibiting classic signs and symptoms of a myocardial infarction. Based on the patient’s ECG, where do you believe the location of the infarct lies?

A. Anterior

B. Low-lateral

C. High-lateral

D. Anterolateral

Following a terrorist attack upon a primary school in Somalia, the physician in charge of the emergency medical response orders you to prepare a quantity of 10 mL syringes containing 1 mg/mL morphine. Drawing from your stock of high-concentration morphine (25 mg/mL), what combination of this drug and normal saline should each syringe contain?

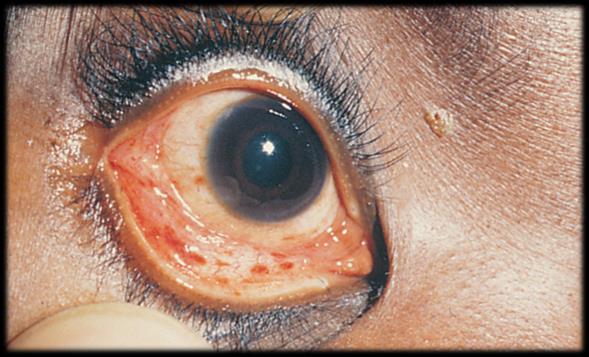

While deployed with the United Nations to Bamako, Mali, you are caring for a 19year-old female Ghanaian cook with unknown vaccine history suffering from an acute onset of headache, irritability, neck stiffness, purpuric nonblanching rashes on both legs, and a petechial rash of the conjunctivae (pictured below). She is now obtunded with a GCS score of 11.

Based on her history and these physical findings, with which of the following organisms do you suspect she is infected?

A. Escherichia coli

B. Neisseria meningitidis

C. Haemophilus influenzae

D. Streptococcus pneumoniae

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

The New England Journal of Medicine

6 January 2022.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2105228.

Seifert S, Armitage J, Sanchez, E.

Snake envenomation represents an important health problem in much of the world. In 2009, it was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease, and in 2017, it was elevated into Category A of the Neglected Tropical Diseases list, further expanding access to funding for research and antivenoms.1 However, snake envenomation occurs in both tropical and temperate climates and on all continents except Antarctica. Worldwide, the estimated number of annual deaths due to snake envenomation (80,000 to 130,000) is similar to the estimate for drug-resistant tuberculosis and for multiple myeloma.2,3 In countries with adequate resources, deaths are infrequent (e.g., <6 deaths per year in the United States, despite the occurrence of 7000 to 8000 bites), but in countries without adequate resources, deaths may number in the tens of thousands. Venomous snakes kept as pets are not rare, and physicians anywhere might be called on to manage envenomation by a nonnative snake. Important advances have occurred in our understanding of the biology of venom and the management of snake envenomation since this topic was last addressed in the Journal two decades ago.4 For the general provider, it is important to understand the spectrum of snake envenomation effects and approaches to management and to obtain specific guidance, when needed.

The Lancet Infectious Diseases

1 February 2022.

DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00485-0.

Ader F, et al.

No clinical benefit was observed from the use of remdesivir in patients who were admitted to hospital for COVID-19, were symptomatic for more than 7 days, and required oxygen support.

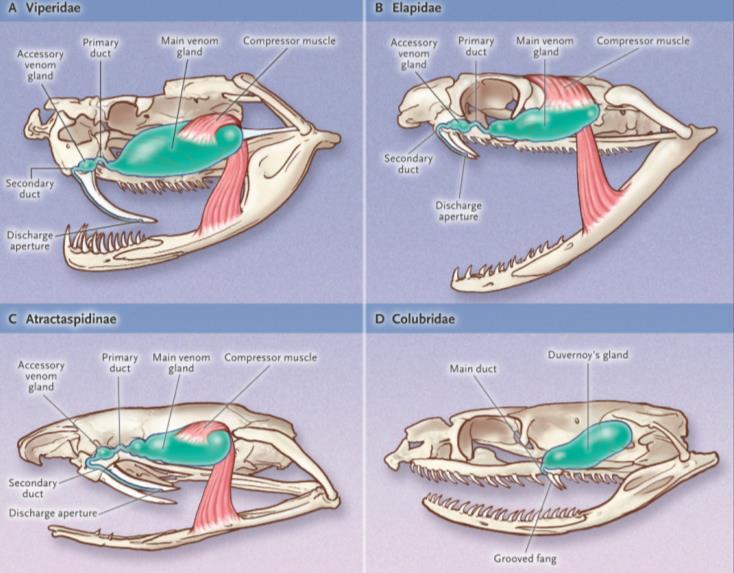

plus standard of care versus standard of care alone for the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a phase 3, randomised, controlled, open-label trialVenom delivery systems of snakes. Diagram courtesy of the NEJM.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

2021 Winter.

PMID: 34969134.

Fulghum GH, et al.

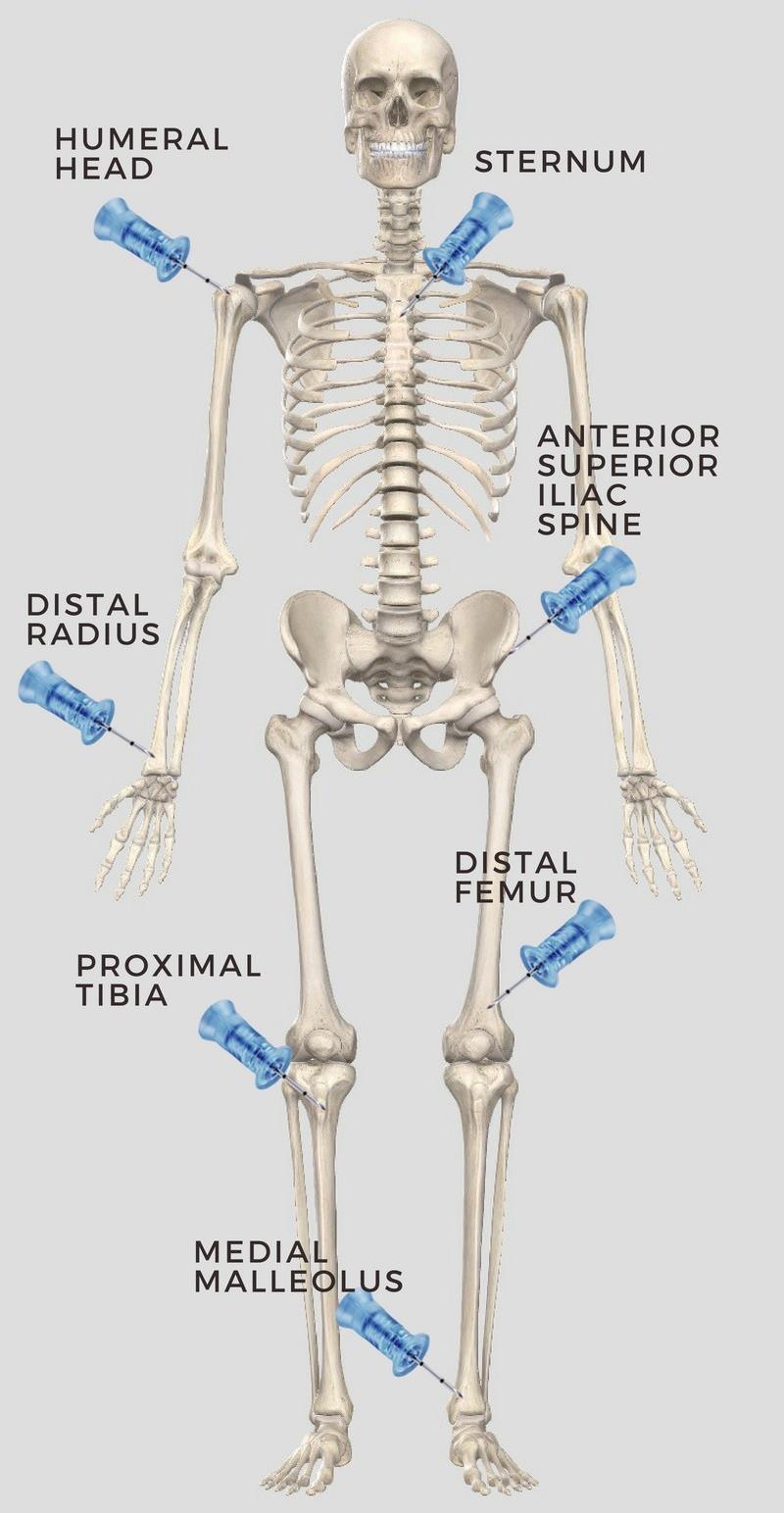

Low-titer cold-stored O-positive whole blood (LTCSO+WB) resuscitation therapy is the cornerstone of military hemorrhagic shock resuscitation. During the past 19 years, improved patient outcomes have shown the importance of this intervention in shock treatment. Iliac crest intraosseous (IO) placement is an alternative when peripheral sites such as the humeral head and tibia are not available options. To date, no study has explored the administration of LTCSO+WB through an iliac crest IO in the military prehospital setting. Contingency procedures for vascular access are necessary for casualties with severe trauma to all four extremities, and the iliac crest is a viable option. The literature supports situational advantages over other peripheral IO sites.

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine

1 December 2021.

DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2021.06.001.

DeYoung H, et al.

CASE REPORT

Stingray envenomation is common in coastal regions around the world and may result in intense pain that can be challenging to manage. Described therapies involve hot water immersion and potentially other options such as opioid and nonopioid analgesics, removal of the foreign body, wound debridement, antibiotics for secondary infection, and tetanus toxoid. However, for some patients, this may not be enough. Peripheral nerve blockade is a frequently used perioperative analgesic technique, but it has rarely been described in the management of stingray envenomation. Here, we report a case of stingray envenomation in an otherwise healthy 36-y-old male with pain refractory to traditional therapies. After admission for pain control, the patient received an ultrasound-guided sciatic popliteal nerve block. Upon completion of the peripheral nerve block, the patient reported rapid and complete resolution of the intense pain, which did not return thereafter.

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis

The summer of 1945 was witness to two historic manmade calamities: the first atomic bombing of a city, and the worst disaster in U.S. naval history. The two events occurred within eight days of each other, and as fate would have it, the U.S.S. Indianapolis – the ship to become immortalized as a cautionary tale to all future naval officers – was the very transport vehicle for Little Boy, the atom bomb dropped onto Hiroshima.

The sinking of the Indianapolis by a Japanese submarine and the subsequent ordeal of the surviving sailors is the central tale of Doug Stanton’s In Harm’s Way. Thanks to the fog of war and a fatal string of assumptions, the survivors underwent four days adrift in shark-infested waters before the U.S. Navy came to the rescue.

“Vividly re-creates this catastrophic chapter in military history. Weaving together accounts from official records and interviews with survivors, [Stanton] has created a war story that is part Titanic, part Stephen King nightmare. Stanton has an eye for the story’s awful ironies and telling details.”

-Star-Tribune (Minneapolis)

Doug Stanton is an author and a founder of the National Writers Series (2009) and the Traverse City Film Festival (2005) Since graduating from the University of Iowa Writer's Workshop, he has worked as a contributing editor at Esquire, Sports Afield, Outside and Men's Journal Stanton has written extensively on travel, sports, entertainment and history.

Drawing on his experiences working in the U.S. and overseas, and with contacts in various branches of the U S military and government, Stanton lectures nationally to corporate and civic groups, libraries, writing & book clubs, and universities about current events, international affairs, politics, and writing

Stanton’s Horse Soldiers was a best-seller on lists in USA Today, Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Entertainment Weekly Publishers Weekly, and IndieBound

What happens to you when you’re floating in salt water for four days?

Haynes: You get dehydrated because you don’t drink. And you’re exercising and losing fluid. I remember fighting with guys to keep them from drinking salt water. It was one of my jobs: to make the group not drink. Because if you drink it, you get diarrhea and that dehydrates you more. You get delirious, like somebody with a high fever. In the beginning, someone would drink salt water and thrash around and raise hell. The two guys holding him down would get exhausted, and they’d die too. So you lost three men for one guy who drank salt water.

We had hallucinations. Guys would see the ship underneath them. They’d think they could dive down and get water out of the scuttlebutt. They’d see it. And then you’d think you could see it.

How did you manage to keep your wits about you?

Haynes: Somebody was always asking me a question: “Doc, can I drink the water if I hold it in my hand for awhile? Will the salt go away?” Or: “If I dive down real deep will it be fresher so I can drink it?” I always had people to take care of. That’s what kept me alive. I had to respond.

McCoy: It’s your mind: I was determined I was going to be the last one alive. I wasn’t going to be the first to quit...It was a helluva lot easier to die than it was to stay alive. It was easier to give up than it was to keep yourself awake and worry about the sharks and go through the torment of that.... I can remember pleading with some of the guys most of the men in our group had children, they were married. We begged, “Hang on! You guys got something to live for!”

What have you learned from Dr. Haynes and Mr. McCoy and all the survivors?

Stanton: Meeting the survivors changed my life; I don’t say that lightly. The unspoken code among them is: be a man of your word. I think people my age, in their 30's, forget that everyday life can be much simpler if you just try to do the right thing it sounds flip, but it’s true. Living a good life is an honorable challenge.

The story of the Indianapolis is a tale of sacrifice and selflessness. Doctor Haynes saved countless lives with nothing more than pure grit and a huge, empathic heart. His simple presence among the boys in the water, as he talked to them, urged them to keep living, kept them sane and breathing. Gil McCoy learned what real strength was only after he surrendered to what seemed his fate, that soon he would be dead, probably eaten by a shark. He didn’t give up his struggle to survive; he surrendered to the situation and accepted it, which is different. He said, “I know I’m going to die, but I’m going to live as long as I can.” If we could bottle the clarity of this understanding, we might answer a whole bunch of questions about what’s important to each of us.

author Doug Stanton

Lewis Haynes LCDR, Medical Corps, USN

Giles McCoy Private First Class, USMC

author Doug Stanton

Lewis Haynes LCDR, Medical Corps, USN

Giles McCoy Private First Class, USMC

“We were hungry, thirsty, no water, no food, no sleep, getting dehydrated, water logged and more of the guys were goin bezerk. There was fights goin on so Jim and I decided to heck with this, we'll get away from this bunch before we get hurt. So he and I kind of drifted off by ourselves. We tied our life jackets together so we'd stay together. Jim was in pretty good shape to begin with, but he was burned like crazy. His hand was burned, he couldn't hold on to anything, couldn't touch anything.”

-Woody Eugene James, COX, USN U.S.S. Indianapolis survivor

-Woody Eugene James, COX, USN U.S.S. Indianapolis survivor

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority. License No. 2018-022.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionalsworking in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

WASHINGTON STATE

MFSLR 6 April 5 July

TTEMS Summer 2022

NORWAY

TTEMS (closed course) October 2022

COLORADO

Austere Emergency Care 10-13 May

Degree Programmes

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice

Doctor of Health Studies

NORTH CAROLINA

SOMSA Conference 2-6 May

Tactical Medicine Review (O’Kelly)

Management of Burns (de Mello)

2022 Tropical Medicine Updates (Jarvis)

AHA ACLS for Experienced Providers (Jarvis)

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Ghana National Ambulance Service

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine

Dates TBD

ACC Acute critical care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

ATTEMS

Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS

Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.edu.mt

The purpose of this questionnaire is to identify gaps in the knowledge or skills that clinicians have gained whilst practicing since they have completed their studies / course (it doesn’t necessarily need to be a course completed within the College. All identifying data will be removed and will be kept confidential. Your answers will help the College better understand the learning gaps of students.

Survey available here:

We are collating information and data from current paramedics, students and alumni about the requirements to practice as a paramedic in different countries. We invite you to add to this database. It will be available from the College in 2022.

Survey available here:

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

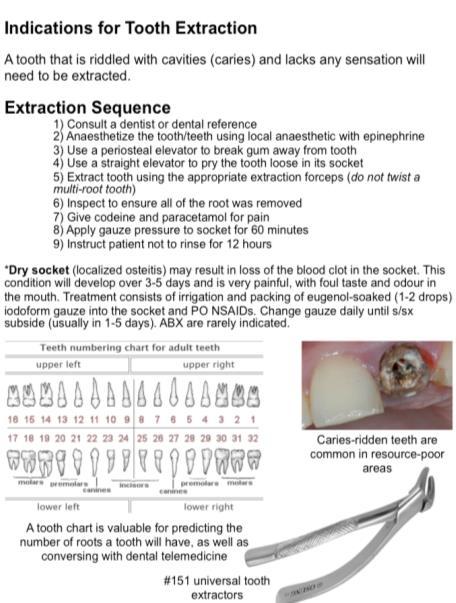

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

Canine medicine

…and much more!