Spring 2021

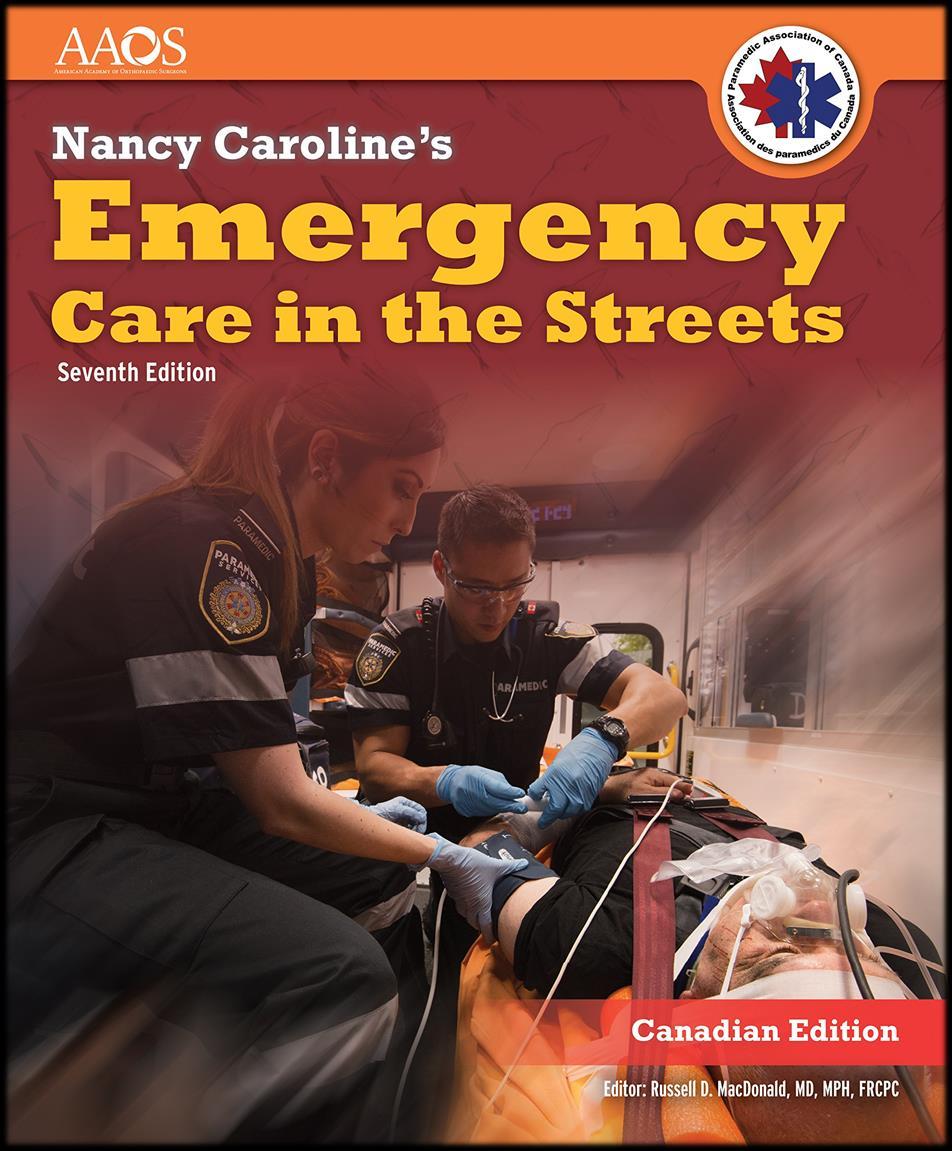

The College has been busy over the winter. We have 32 students enrolled into our three-year BSc Remote Paramedic Practice programme, which has full accreditation approval from the European Qualifications Framework.

The pandemic has still been causing disruptions to the College schedule but we do hope to be able to run our Remote Paramedic classroom sessions in May and June in Malta. The clinical placements at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center in Tanzania are up and running and we currently have Remote Paramedics working there with Dr. Francis Sakita in the A&E department.

The College has again been invited to give lectures at the Special Operations Medical Association’s conference in Charlotte, NC in June and July. I will be giving my usual Tactical Medicine Review workshop and we will be giving the IBSC board certification exams in collaboration with the IBSC. Dr. Winston de Mello will be lecturing on burns and Jason Jarvis will give another lecture on tropical medicine.

As usual, the College will have an exhibitor’s table at the SOMA conference and will be giving out free subscriptions to the new CoROM Field Guide app. We will also be giving out free access to our new online CPD courses called “Tropical Medicine for SOF Medics.” We welcome everyone to stop by our booth and claim these free gifts from CoROM.

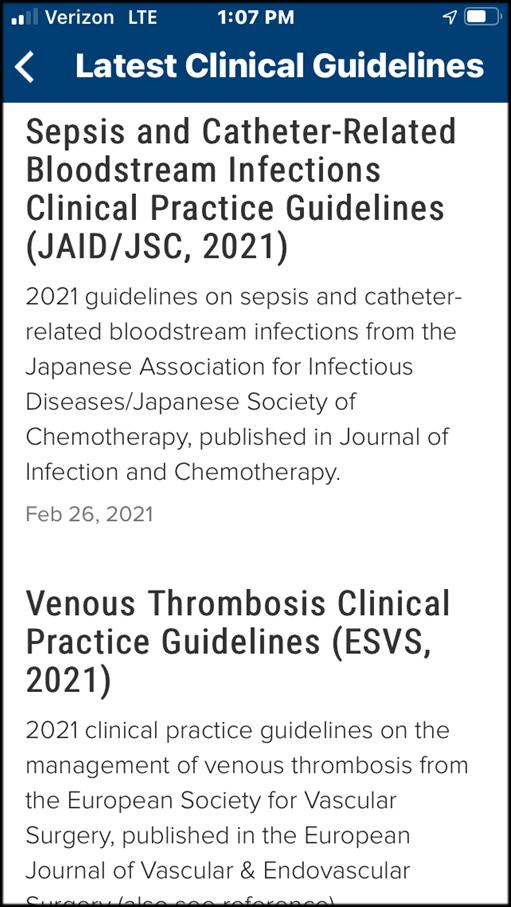

We are delighted to publish our new CoROM app. It will include searchable content from our Field Guide and will include the EMS drugs guide and other tools helpful for remote medics and other healthcare practitioners. Yes, all content is downloadable and available offline.

The College continues to be flexible during the pandemic. We are putting more planning on virtual postgraduate options for the healthcare professional working in remote, austere and resource-limited environments.

It is thrilling to see in-house courses returning to the CoROM calendar of events. The College made great strides into the realm of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is certainly more satisfying as a trainer to interact with students in physical space.

In spite of the myriad COVID-19 restrictions we’ve all endured, I managed to teach predeployment medical courses in Ghana and Rwanda for the United Nations Institute of Training and Research, and am leaving soon for Kenya under the auspices of that group.

Jason Jarvis 18D NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

Jason Jarvis 18D NREMT-P CoROM TropMed Lead The Compass editor

My ambition to review Dr. William Osler’s voluminous The Evolution of Modern Medicine for The Compass was regrettably curtailed by my work in Africa, so readers will have to settle for a review of Osler’s much shorter and punchier Aequanimitas.

Springtime is always a special season for CoROM as we prepare for our return to the Special Operations Medicine Scientific Assembly held annually in North Carolina. I have already begun what will be an exhaustive review of the recent literature on tropical medicine as I prepare to give a seminar entitled ‘2021 Tropical Medicine Updates.’ While at SOMSA – an event that is the closest I get to the center of the universeCoROM Dean Aebhric O’Kelly and I will man an exhibitor’s booth and will glean what useful information/practices/technologies can be incorporated into the CoROM curriculum.

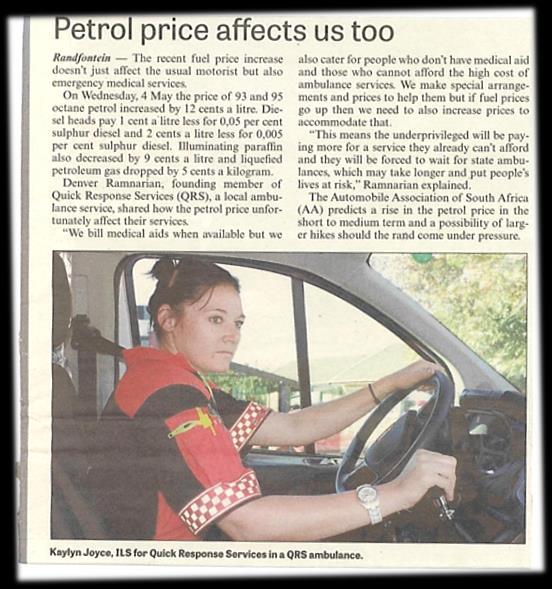

In this issue of The Compass we feature another superb Public Health writeup from Nicole Foster, as well as O’Kelly’s regular Improvised Medicine piece – this time on the lowly Mylar Emergency Blanket. CoROM’s Head of Undergraduate Studies Neil Coleman is our featured faculty member, and South African medic Kaylyn Joyce rounds out our contributors with the newsletter cover photo as well as being the subject of Where Are They Now?

a feature profiling past and current CoROM students and their journey towards excellence. It is with both excitement and gratitude that I piece together this edition of The Compass, the product of like-minded people living on four continents.

Jason Jarvis is a paramedic and former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan. Based in Seattle, he is currently a freelance medical educator for several organizations including the United Nations, Harborview Medical Center, Raider Tactical, Operational Medicine Consultants, CPR Seattle, LifeTek, and Children’s Hospital of Seattle. He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for International Health, and is working towards a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

I have been qualified as an Intermediate Life Support Paramedic in South Africa just over 10 years now and to be honest, I think there is very little that I have not experienced. Secondary to that, I have been caught in cross fires and literally dodged bullets, while some of my colleagues have been robbed and/or even assaulted. Being a medic in SouthAfrica is certainly not for the fainthearted, but without a doubt after all this, being a part of the EMS family comes with a tremendous passion that I have for helping the sick and injured, whilst serving the community. We truly are one big family.

Kaylyn Joyce ILS Paramedic

Our ambulances crew both an Intermediate Life Support and a Basic Life Support medic; alongside this there areAdvanced Life Support Paramedics that operate response cars to provide backup when required.

Our training does not extend to place advanced airways or administer sedatives and analgesic drugs, but we can do a few invasive procedures, and we do have some drugs in our scope.

Working in SouthAfrica, every day is filled with heart pumping adrenaline, racing from one call to the next. You never know what to expect. Needless to say, each call is different, so we’re always alert and ready to go. Regardless of the severity, we as team generally complete the entire call within the golden hour. Often - with little to no time for a rest - the next call has us back out and on the road serving the community once more.

As a senior paramedic on the ambulance, one of the most challenging situations that I am faced with is triaging of patients on a mass casualty scene. We experience a high rate of mini bus accidents (known here as taxis).The taxis, are legally able to transport 14 passengers at a time, but sadly, toooften they carry more than they are equipped to handle and to add to the problem, the vehicles have been poorly maintained, which can lead to terrible consequences. Thus, when these vehicles are involved in road traffic collisions, the casualties often lead to fatalities. Apart from these difficult scenes, the high crime rate involving hate crimes, gender-based violence and pedestrian accidents can all be part of the same 12 hour shift.

I recently completed my first year CRP with CoROM, including my ACLS, ITLS and TTEMS. The course was outstanding. I learned a lot with regards to medical and environmental emergency medicine as well as remote-based medicine and prolonged patient care. The latter topics are things we would not normally have exposure to in SouthAfrica. I completed my clinical placement at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) in Tanzania over four weeks – a very educational experience. Although our government facilities are a lot like KCMC, the Emergency Department at KCMC is filled with many medical cases, making it a great learning platform. The doctorsare encouraging and great mentors, and I certainly gained an invaluable amount of experience and am excited to be returning for my second year placement in the near future.

During my time at KCMC I was exposed to a different approach to emergency medicine. I was quite used to the EMS-style rapid exams, the “find it and fix it” approach, followed by the rapid handover at hospital. CoROM teaches you how to do a comprehensive workup of the patient as well as compile a variety of different treatments that are available to assist the patient and then most importantly the long-term treatment. Alongside this, I also learnt how to document the treatment plan while maintaining a high standard of patient care. At KCMC I was able to practice this as well as practice the advanced skills I had been taught during my CRP course. Overall this was one of the most invaluable life learning experiences I’ve yet to encounter and I thoroughly enjoyed every minute of it.

I am excited to begin my second year with CoROM, and to continue this knowledge and experiencebuilding journey toward becoming a well-rounded practitioner.

Kaylyn Joyce assists in the delivery of a newborn at KCMC, Tanzania

Kaylyn Joyce assists in the delivery of a newborn at KCMC, Tanzania

Neil Coleman is the head of undergraduate studies for CoROM. He began his career as a Combat Medic, and is now an advanced paramedic in his native Ireland. Neil is also registered in Malta with the MRP. He has worked in several jurisdictions across a 20+ year career, and holds a master's degree and two postgraduate qualifications in pre-hospital care. He is currently a Fellowship candidate with the Wilderness Medical Society and is the chapter coordinator for the ITLS Malta and Gozo Chapter.

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed Hdip EMT-A CoROM Head of Undergraduate Studies

I have been involved with CoROM prettymuch from the start. It has been an incredible journey that I have learnt so much from, and hopefully I've been able to do a little teaching along the way! For me, one of the best parts of CoROM is meeting people from very different backgrounds clinically, and from all over the world. That in itself is a huge educational experience, and something I value very much.

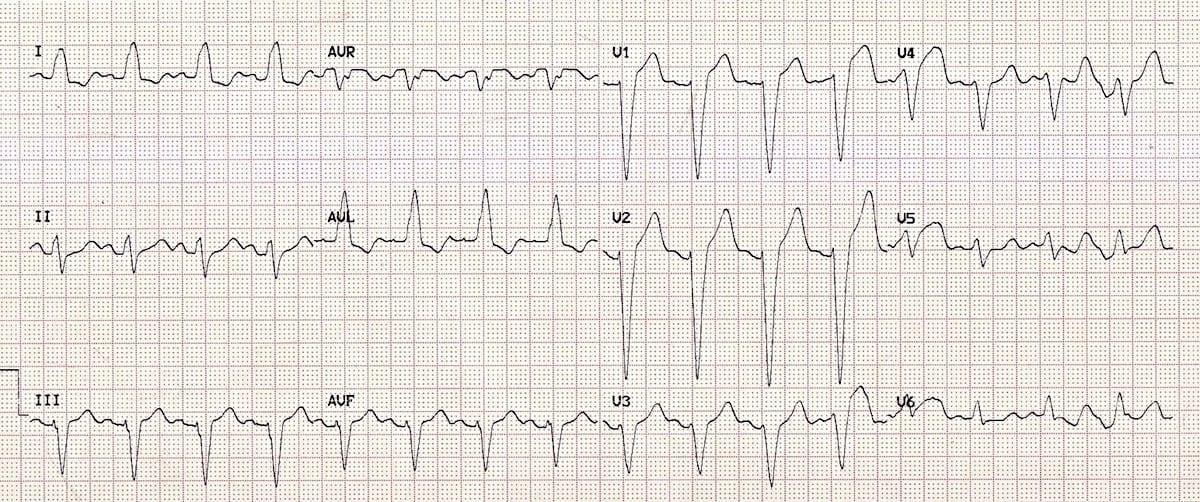

I have always really enjoyed teaching entry-level ECG interpretation. For many students it is daunting to look at a 12-lead ECG for the first time. I know the first time I saw one I seriously reconsidered my career choice! There is a great sense of satisfaction from spending some time teaching this and watching the understanding of the topic grow.

The CoROM journey has already been incredible. Five years ago go if you had told me that we would be a degree granting institution, on the verge of launching a master's level degree, and with firm plans for a PhD already in motion, I probably would have laughed at you! Over the next five years I want to see CoROM continue to grow and develop into a world-class college, teaching what is a very specialised area of care. I would also love to see a drive towards standardisation of the paramedic grade across Europe but I am all too aware how large and difficult a task this would be!

Being honest about this there have been many. It would be very difficult at this stage of my career to pick one specific case that would answer this question. Some cases have made a lasting impression because of what I learnt from them, some because of the difficulty in dealing with them and some because of very good outcomes. What I think is important, is that even after 23 years as a working paramedic across several different grades and titles, I still learn every single day. If you are open to learning, then literally every case you attend has the potential to impact upon you in a positive way.

Neil Coleman is the ITLS chapter coordinator for Malta and Gozo

Neil Coleman is the ITLS chapter coordinator for Malta and Gozo

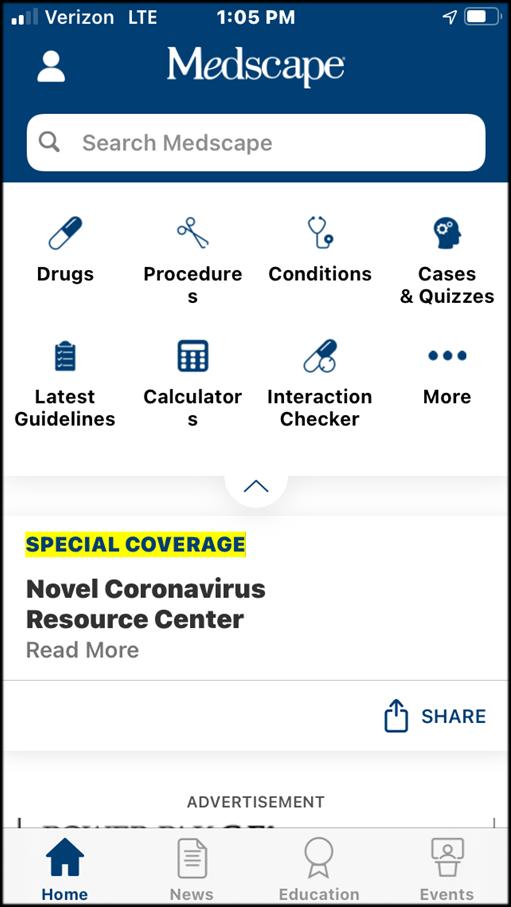

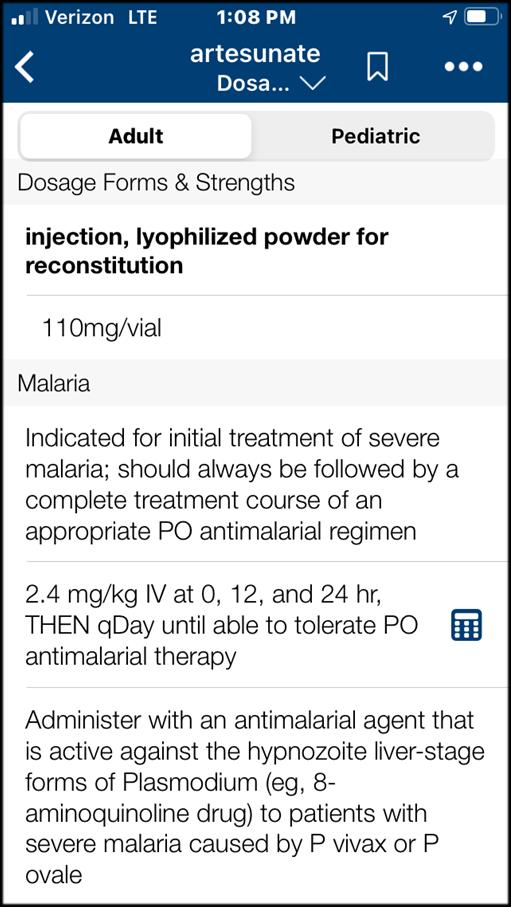

I am going to cheat on this question and only offer two answers. This is because I think the reference you require will change depending on your contract or deployment. For example, a clinicbased contract may require you to have a good ECG reference. Then if you are on contract where you are the lone medic, you may require a totally different type of reference. So my answer is this. Medscape as a general reference is something I have used often and found to be an excellent, accurate, and reliable source of information.. But I also have to fly the CoROM flag here and say that I honestly find the CoROM field guide very concise and a good reference for remote and austere Medics, largely because that is the market it was aimed at. Because of that it is "taskspecific." Something I feel very strongly about, is that references are just that, and do not and should not replace sound clinical knowledge and practice.

COVID-19 has been the focus of the media and the community since the pandemic kicked off in 2020, however, in the past 12 months, other natural and humanitarian disasters have continued to impact on the global community. COVID-19 has been devastating in resource poor environments, but not because of the harm that the disease itself causes – it is an additional burden to those already facing internal and international displacement due to conflict, natural disasters compounded by climate change, famine and interruption of health care and vaccination programs. We know that focusing on this pandemic has set back 20 years of progress in fighting the big 3

TB, malaria, and HIV. So, what has been happening while COVID-19 is the centre of attention?

Aquick snapshot of the data that has been captured from 2019 - 2020

• 396 natural disasters

• 24 396 fatalities

• 97.6 million people affected

• 130 billion dollars (US) in damage

• 127 floods, 59 storms, 25 landslides, 8 wildfires, 10 extreme temperatures, 8 droughts, 32 earthquakes, 3 volcanic activities, 36 disease outbreaks

In 2020, more than 100 disasters occurred in the first 6 months of the pandemic (March – Sept), with 50 million people affected. 99% of people affected were impacted by extreme climate and weather-related disasters – most were from natural disasters such as flooding, storms, disease outbreaks and earthquakes – with most of these events occurring in Africa and Asia. Swarms of desert locusts, the most destructive migratory pest in the world, are devouring thousands of square kilometres of crops and grasses throughout Eastern Africa. It is the worst infestation in decades and affecting over 25 million people already severely food-insecure in this region.

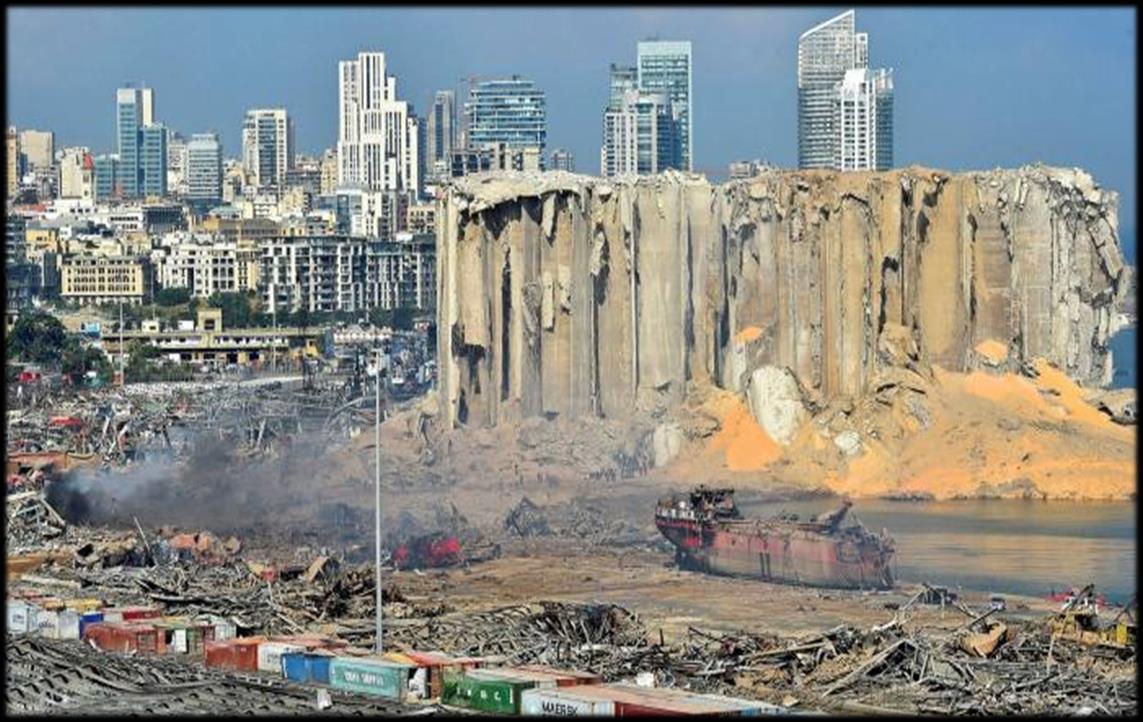

Technological, man-made and complex humanitarian disasters occurred in / continued in Beirut, Venezuela and Colombia, and Syria and Yemen, with the Syrian refugee crisis now in its 10th year, and Yemen in its 4th year with 80% of its population requiring some form of humanitarian or protection assistance.

Nicole Foster BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

Nicole Foster BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

In 2021, 235 million people will need humanitarian assistance and protection. The 13 top countries requiring help are:

Yemen 24.3m, Ethiopia 21.3m, DRC 19.6m, Afghanistan 18.4m, Sudan 13.4m, Syria 13m, Pakistan 10.5m, Nigeria 8.9m, South Sudan 7.5m, Mali 7.1m, Venezuela 7m, Zimbabwe 6.8m, Colombia 6.7m.

Most of these countries are facing complex disasters – civil unrest, unstable governments, lack of access to health care, spiralling communicable disease outbreaks, food shortages, famine and natural disasters, all of which are increasing in occurrence, intensity, and duration.

The WHO are currently responding to grade three health emergencies (highest response) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Yemen and a further 22 countries or events that are Grade two, and 6 Grade one emergencies. Last year, in addition to SARS-CoV-2 (and its variants), the WHO dealt with the following infectious disease outbreaks:

• 29 December 2020

Yellow fever

Senegal

• 23 December 2020

Yellow fever

Guinea

• 27 November 2020

Acute hepatitis E – Burkina Faso

• 24 November 2020

Yellow fever

Nigeria

• 17 November 2020

Avian Influenza A(H5N1)- Lao People's Democratic Republic

• 13 November 2020

Rift Valley Fever – Mauritania

• 24 October 2020

Mayaro virus disease - French Guiana, France

• 13 October 2020

Oropouche virus disease - French Guiana, France

• 1 October 2020

Monkeypox

Democratic Republic of the Congo

• 24 September 2020

Chikungunya – Chad

• 1 September 2020

Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 – Sudan

• 1August 2020

Yellow fever – French Guiana, France

• 23 July 2020

Plague – Democratic Republic of the Congo

• 9 July 2020

Influenza A(H1N2) variant virus – Brazil

• 17 June 2020

Yellow fever – Gabon

• 5 June 2020

Yellow fever – Togo

• 25 May 2020

Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) – Ethiopia

• 6 May 2020

Measles – Burundi

• 24April 2020

Measles – Mexico

• 23April 2020

Dengue fever – Mayotte, France

• 22April 2020

Yellow fever – Ethiopia

• 18April 2020

Yellow fever – Republic of South Sudan

• 12 March 2020

Chikungunya is an enveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA arbovirus in the Togavirus family, which includes rubella, Eastern equine encephalitis, and Western equine encephalitis

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Qatar

• 10 March 2020

Dengue fever – French Territories of theAmericas – French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint-Martin, and Saint-Barthélemy

• 4 March 2020

Measles - Central African Republic

• 24 February 2020 – 1 Feb 2021

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

• 22 February 2020

Dengue fever – Chile

• 21 February 2020

Yellow fever – Uganda

• 20 February 2020

Lassa Fever – Nigeria

• 10 January 2020

Measles – occupied Palestinian territory

• 8 January 2020 – 31 January 2020

Measles is an enveloped negativesense single-stranded RNA virus in the Paramyxovirus family, which includes mumps, parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial virus

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – The United Arab Emirates

• 2 January 2020 – 18 November 2020

Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo

Read the reports:

Global humanitarian overview 2021 by the UN Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairshttps://www.unocha.org/global-humanitarian-overview-2021

World disasters report 2020 - Come heat or high water by the International Federation of the Red Cross - https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/world-disaster-report-2020/

The Global Risks Report 2020 – World Economic Forum

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risk_Report_2020.pdf

The WHO - https://www.who.int/emergencies/crises/en/

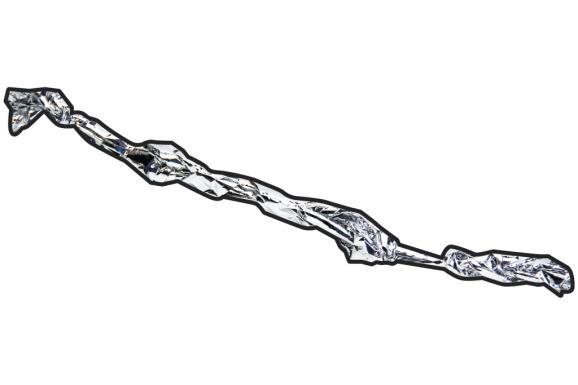

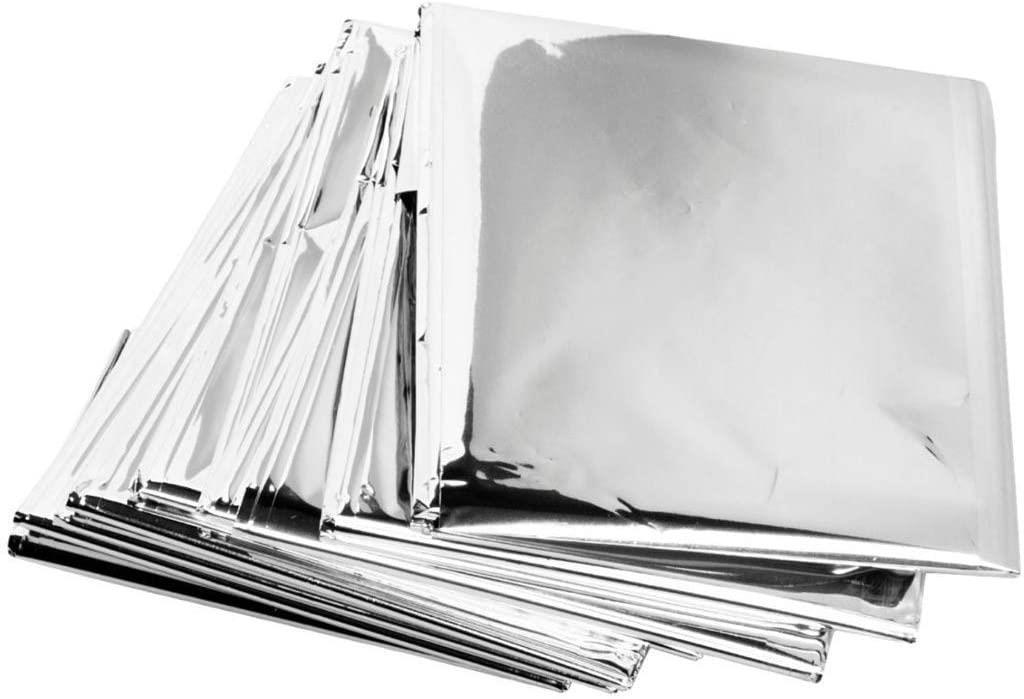

I get it. We all get it. This is a flimsy, self-disintegrating, shoddy piece of medical kit. We see them as we inventory our medical pack at the beginning of each shift and either completely ignore them or possibly toss them in the bin when no one is looking. They catch the slightest bit of breeze and are quickly blown away as you try to keep your casualty warm. They are loud, deafeningly loud in enclosed places. They don’t seem to ever work. But we may be tooquick to judge.

Perhaps we should relook at this bit of kit and think outside the box on how it can benefit the remote healthcare practitioner.

The first suggestion is to use it as a ground insulation for your casualty. But you cannot just lay it on the ground and hope for the best. You need insulation. So, grab two of these blankets. Put one on the ground. Find dry moss, spare clothes, a blanket, leaves or even pine needles and cover the blanket with 4-5cm of debris. Then place the second Mylar blanket on top. Now you have an insulating layer on which to put your casualty. Use three additional silver blankets to cover your casualty. That will provide two empty spaces between the blankets where trapped air can keep your casualty warm. Oh, and one more blanket ripped in half – one half goes around the head of the casualty, the other gets wrapped around the legs.

So, the magic number is six. It takes six of these shoddy silver blankets to cover your casualty. Two under the casualty, three over the casualty and one more split in two for the head and feet. These blankets are compact and don’t take up much space. Make sure that you have at least six packed together in your medical kit.

Additional benefits for your casualty:

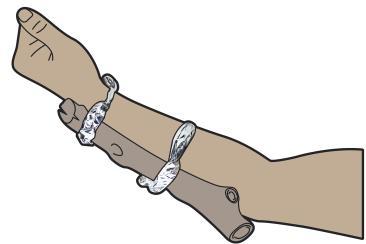

Make triangular bandages for splinting

Compression bandage

Cut into strips to tie improvised splints

Cushion material for improvised splints

Improvise a scarf

Create a pillow for the casualty by stuffing it with dry leaves or spare clothes

Cut into strips to tie your ECG wires so you don’t have spaghetti problems

Create sandbags to support the neck of a suspected spinal fracture

Warm IV fluids near the coals of a fire (the melting point of Mylar is 250°C)

Tarp to keep the rain off of you and your casualty

Tarp to keep the sun off of you and your casualty

Create a sterile field for suturing

Protective apron when you irrigate a wound

Wrap up bloody items to keep your kit uncontaminated until you can clean them

Wrap a neonate patient after delivery

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E MA FAWM DipPara CCP-C TP-CNon-medical uses:

Cut into strips and tie to trees for marking an austere clinic

Hang from trees to create privacy walls

Build a horseshoe pack to carry small items

Use as a belt if yours breaks

Twist into an antenna to boost mobile phone or radio reception

The bottom line:

There is no reason that you should not have a pack of six Mylar Emergency Blankets in your medical kit.

Resources

Rodriguez A, Algaze I,Almog R, Katzer RJ. Heating Intravenous Fluid Tubing in an Experimental Setting for Prehospital Hypothermia. Air Med J. 2021 Jan-Feb;40(1):41-44.

Since the publication of Tactical Combat Casualty Care in Special Operations in 1996 (known today as the “TCCC white paper”), the science behind casualty care on the front lines has grown by leaps and bounds. The many lessons learned during Operation Enduring Freedom and Operations Iraqi Freedom hearken back to Hippocrates, who once said, “He who wishes to be a surgeon should go to war.”

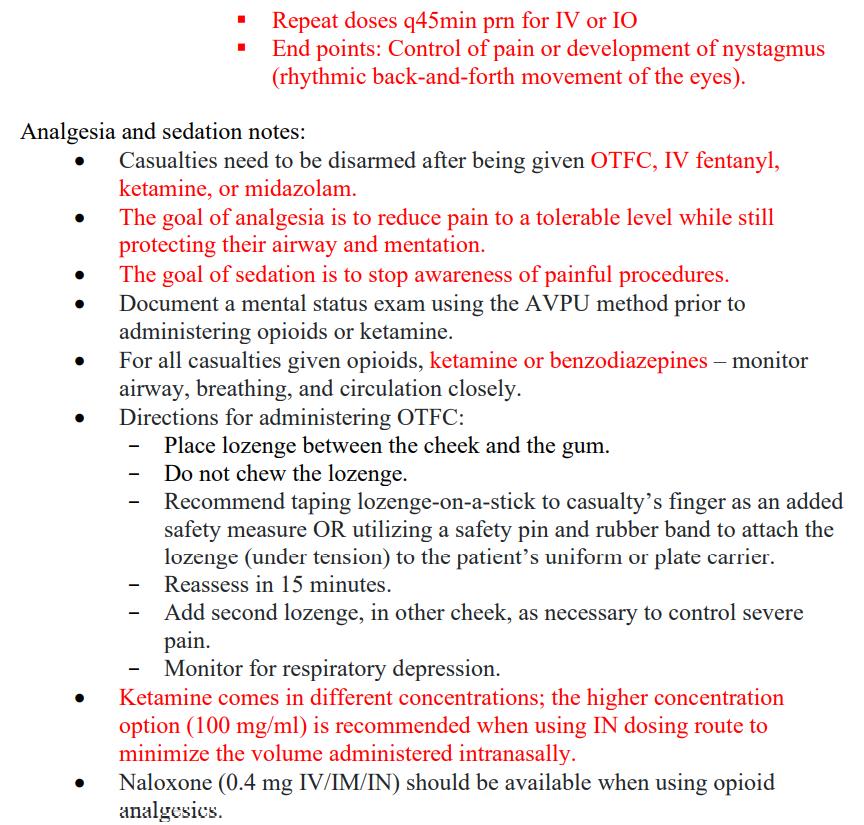

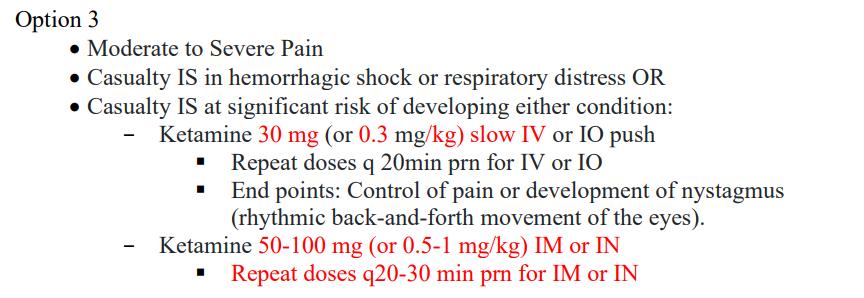

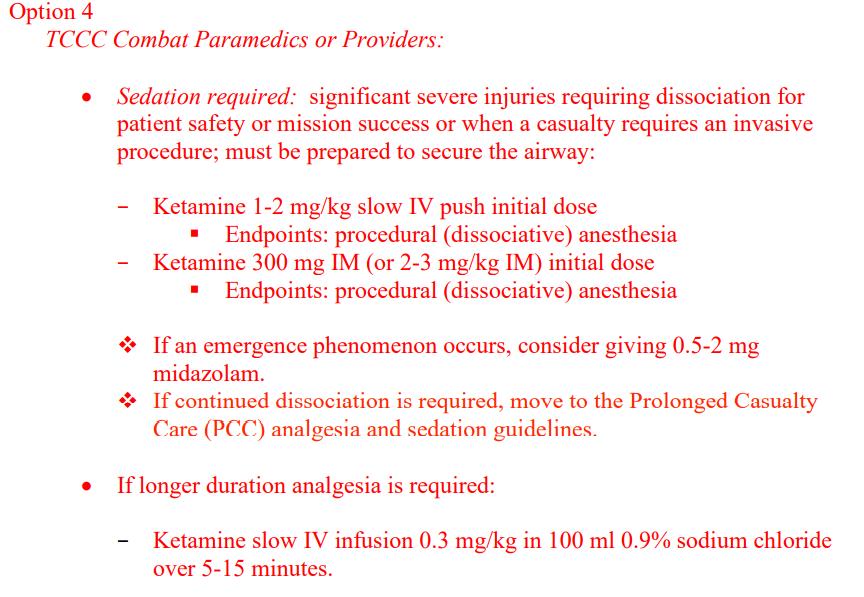

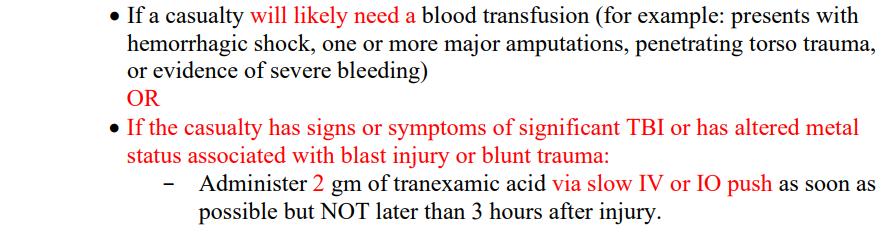

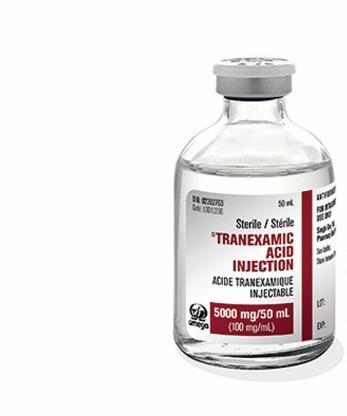

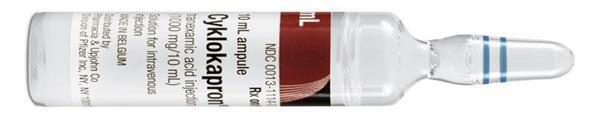

JarvisThe Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) periodically releases new guidelines for field medical practitioners. The latest guidelines – dated 5 November 2020 – reflect changes in “tranexamic acid administration, prevention of trauma induced hypothermia, fluid resuscitation, analgesia, abdominal evisceration, and separation of the TACEVAC guidelines.”

For a full description of the TCCC guidelines visit the Deployed Medicine website or try out the app. Highlights from the new guidelines appear on the following pages of The Compass

Tranexamic acid

Fluid resuscitation

Abdominal evisceration

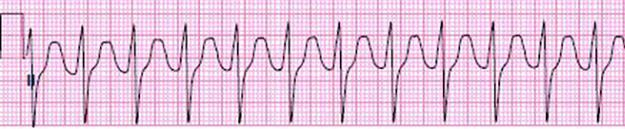

While working up a patient complaining of abdominal pain you notice an anomaly in her 12-lead. Which part of her heart is most likely responsible for this?

A. Sinoatrial node

B. Left bundle branch

C. Right bundle branch

D. Atrioventricular node

While assigned to a demining mission in Laos, you are asked to resuscitate a 30-kilogram boy who fell off of a motorcycle and was subsequently run over by a second motorcycle. The child is hypotensive with decreased mental status, a rigid belly and your point-of-care ultrasound shows free fluid in Morrison’s Pouch. While in transit to the nearest hospital (a 5-hour journey via pickup truck) you have administered a 450 mg IO bolus of tranexamic acid (TXA) and are preparing to give additional TXA as an infusion at a rate of 2mg/kg/hour over the next 8 hours. You have 1 gram of TXA mixed into a 1-liter bag of 0.9% sodium chloride, and a 20-drop/mL giving set. At what rate should you set the infusion, in drops per minute?

During a sustained nighttime mortar attack on your camp in Afghanistan, one of your junior medics believes he inadvertently gave the wrong medication to a casualty whom he meant to give 10mg of morphine intravenously. The casualty is now exhibiting the following signs: flushed red skin, dry mucous membranes, mydriasis, wide-complex tachycardia with QT prolongation (pictured), altered mental status and a temperature of 38.5° C. Which of the following drugs do you think was administered?

A. Bactrim

B. Ketamine

C. Epinephrine

D. Diphenhydramine

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: COPD

Clinical calculation: 53 drops/minute

Clinical case: Podoconiosis

Medical Reference (Kaylyn Joyce’s pick)

Gear

For further information please contact https://www.tacmedsolutions.com

The OLAES® Hemostatic Bandage combines the globally recognized OLAES® Modular Bandage with battle-tested HemCon® ChitoGauze® PRO, creating the industries new “gold standard” trauma dressing. Both proven life-saving devices are now together in a single, easily accessible package. Being hemostatic in effect, and modular in its flexibility, this is an industry first with the ability to treat multiple injury profiles- all in one package.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Winter 2020.

PMID: 33320318

Androski CP, et al.

Early tranexamic acid (TXA) administration for resuscitation of critically injured warfighters provides a mortality benefit. The 2019 Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) recommendations of a 1g drip over 10 minutes, followed by a 1g drip over 8 hours, is intended to limit potential TXA side effects, including hypotension, seizures, and anaphylaxis. However, this slow and cumbersome TXA infusion protocol is difficult to execute in the tactical care environment. Additionally the side effects caution derive from studies of elderly or cardiothoracic surgery patients, not young healthy warfighters. Therefore, the 75th Ranger Regiment developed and implemented a 2g intravenous or intraosseous (IV/IO) TXA flush protocol. We report on the first six cases of this protocol in the history of the Regiment. Afteraction reports (AARs) revealed no incidences of post-TXA hypotension, seizures, or anaphylaxis. Combined, the results of this case series are encouraging and provide a foundation for larger studies to fully determine the safety of the novel 2g IV/IO TXA flush protocol toward preserving the lives of traumatically injured warfighters.

Prehospital use of ketamine in mountain rescue: a survey of emergency physicians of a single-center alpine helicopter-based emergency service

Wilderness & Environmental Medicine

December 2020.

DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2020.06.004

Vanolli, et al.

Ketamine was considered safe and judged irreplaceable by most physicians. The main reason for ketamine use was acute analgesia during painful procedures, such as manipulation of femur fractures. The doses of ketamine administered with or without fentanyl ranged from 0.2 to 0.7mg/kg intravenously. Most physicians reported using fentanyl and midazolam along with ketamine. The median dose of midazolam was 2 (interquartile range 1-2) mg for a 70-kg adult. Monitoring and oxygen administration were used infrequently. Hallucinations were the most common adverse events. Knowledge of ketamine contraindications was poor.

International Health

June 2010.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inhe.2010.02.003.

Sousa-Figueiredo, et al.The Ugandan national control programme for schistosomiasis has no clear policy for inclusion of preschool-children (≤5 years old) children. To re-balance this health inequality, we sought to identify best diagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis, observe treatment safety and efficacy of praziquantel (PZQ), and extend the current WHO dose pole for chemotherapy. We examined and treated 363 preschool children from shoreline villages of Lakes Albert and Victoria, and found that 62.3% (CI95 57.1-67.3) of the children were confirmed to have intestinal schistosomiasis. One day after treatment, children were reported as having headaches (3.6%), vomiting (9.4%), diarrhoea (10.9%) and urticaria/rash (8.9%) with amelioration at 21-day follow-up, where the parasitological cure rate was found to be 100%. Height and weight data were collected from a further 3303 preschool children to establish and validate an extended PZQ dose pole that now includes two new height-intervals: 60-84cm for one-half tablet and 84-99cm for three-quarter tablet divisions; which would result in 97.6% of children receiving an acceptable dose (3060mg/kg). To conclude, preschool children in lakeshore communities of Uganda are at significant risk of intestinal schistosomiasis; we now strongly advocate for their immediate inclusion within the national control programme to eliminate this health inequity.

African Journal of Emergency Medicine

19 February 2021

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2021.02.003

Hamza, et al.

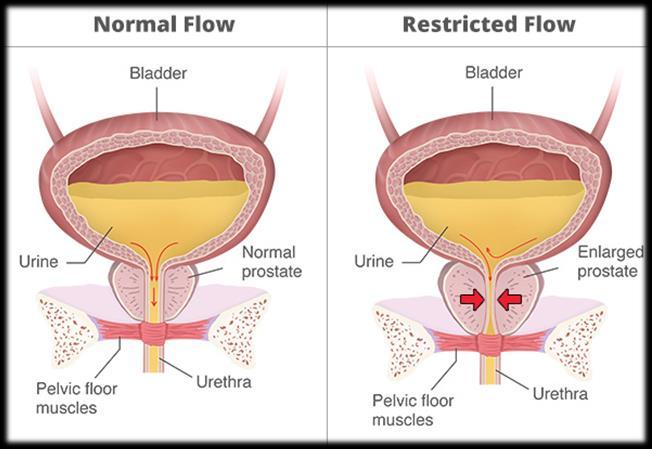

The records of a total of 681 patients were retrieved and they span across almost all ages with age range of 2-90 years. Urinary retention was the commonest emergency seen, accounting for 51.7% of the patients.

Testicular torsion was the next most common (10%), others are bilateral ureteric obstruction and priapism with 5.4% and 5.3% respectively. Suprapubic cystostomy (SPC) was the commonest operative procedure performed (37.6%). The age range for patients with urinary retention was 3-90 years, though the peak incidence was in the 7th decade (37.3%).

Patients with testicular torsion were young adults between the ages of 11 and 44 years.

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis

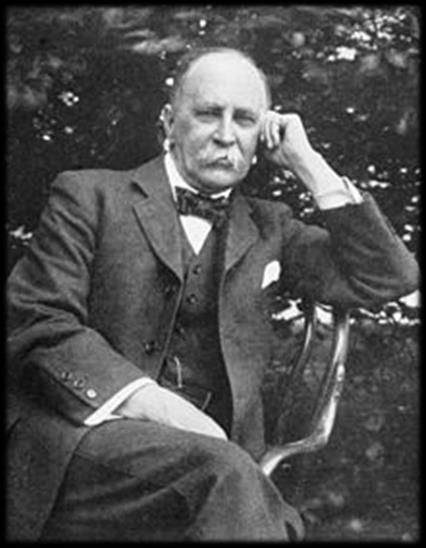

Only when the name of Dr. William Osler had been reverentially spoken of by two different mentors of mine on two different continents did I decide to read up on the famous physician. Medical history has become one of my favorite pastimes, so it was only a matter of time before I would have stumbled upon the extraordinary works of one of medicine’s most extraordinary minds.

As mentioned on the earlier Editor’s Notes page, my ambition was to read and review Osler’s Evolution of Modern Medicine, a work that spans 125 pages in my Project Gutenberg digital copy. Osler himself described Evolution as “an aeroplane flight over the progress of medicine through the ages.” Strapped for time between running medical training courses in both Ghana and Rwanda, I settled upon Osler’s much shorter essay Aequanimitas, which was his 1889 farewell address to newly-minted doctorsat the Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

As Osler explains in his essay, aequanimitas is the core personality trait of a goodphysician, that is, maintaining a state of calm imperturbability in the face of uncertainly and disaster. Undoubtedly this is a desirable trait in many other walks of life, from astronauts to generals to athletes.

Reading Osler, one becomes immediately aware of the depth and breadth of his learning. He reminds us of a time when medical practitioners were much more steeped in classic literature and the humanities than their modern counterparts.

For example, I have difficulty imaging a twenty-first century-era doctor penning a passage such as this from Aequanimitas: “Even with disaster ahead and ruin imminent, it is better to face them with a smile, and with the head erect, than to crouch at their approach. And, if the fight is for principle and justice, even when failure seems certain, where many have failed before, cling to your ideal, and, like Childe Roland before the dark tower, set the slug-horn to your lips, blow the challenge, and calmly await the conflict.”

On the following page is a longer passage from Aequanimitas I hope readers will enjoy.

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, FRS FRCP; (1849 – 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the four founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of physicians, and he was the first to bring medical students out of the lecture hall for bedside clinical training. He has frequently been described as the Father of Modern Medicine and one of the "greatest diagnosticians ever to wield a stethoscope." Osler was a person of many interests, who in addition to being a physician, was a bibliophile, historian, author, and renowned practical joker. One of his achievements was the founding of the History of Medicine Society of the Royal Society of Medicine, London. -Wikipedia

“In the first place, in the physician or surgeon no quality takes rank with imperturbability, and I propose for a few minutes to direct your attention to this essential bodily virtue. Perhaps I may be able to give those of you, in whom it has not developed during the critical scenes of the past month, a hint or two of its importance, possibly a suggestion for its attainment. Imperturbability means coolness and presence of mind under all circumstances, calmness amid storm, clearness of judgment in moments of grave peril, immobility, impassiveness, or, to use an old and expressive word, phlegm. It is the quality which is most appreciated by the laity though often misunderstood by them; and the physician who has the misfortune to be without it, who betrays indecision and worry, and who shows that he is flustered and flurried in ordinary emergencies, loses rapidly the confidence of his patients.

In full development, as we see it in some of our older colleagues, it has the nature of a divine gift, a blessing to the possessor, a comfort to all who come in contact with him. You should know it well, for there have been before you for years several striking illustrations, whose example has, I trust, made a deep impression. As imperturbability is largely a bodily endowment, I regret to say that there are those amongst you, who, owing to congenital defects, may never be able to acquire it. Education, however, will do much; and with practice and experience the majority of you may expect to attain to a fair measure. The first essential is to have your nerves well in hand. Even under the most serious circumstances, the physician or surgeon who allows "his outward action to demonstrate the native act and figure of his heart in complement extern," who shows in his face the slightest alteration, expressive of anxiety or fear, has not his medullary centres under the highest control, and is liable to disaster at any moment. I have spoken of this to you on many occasions, and have urged you to educate your nerve centres so that not the slightest dilator or contractor influence shall pass to the vessels of your face under any professional trial. Far be it from me to urge you, ere Time has carved with his hours those fair brows, to quench on all occasions the blushes of ingenuous shame, but in dealing with your patients’ emergencies demanding these should certainly not arise, and at other times an inscrutable face may prove a fortune. In a true and perfect form, imperturbability is indissolubly associated with wide experience and an intimate knowledge of the varied aspects of disease. With such advantages he is so equipped that no eventuality can disturb the mental equilibrium of the physician; the possibilities are always manifest, and the course of action clear. From its very nature this precious quality is liable to be misinterpreted, and the general accusation of hardness, so often brought against the profession, has here its foundation. Now a certain measure of insensibility is not only an advantage, but a positive necessity in the exercise of a calm judgment, and in carrying out delicate operations. Keen sensibility is doubtless a virtue of high order, when it does not interfere with steadiness of hand or coolness of nerve; but for the practitioner in his working-day world, a callousness which thinks only of the good to be effected, and goes ahead regardless of smaller considerations, is the preferable quality. Cultivate, then, gentlemen, such a judicious measure of obtuseness as will enable you to meet the exigencies of practice with firmness and courage, without, at the same time, hardening ‘the human heart by which we live.’”

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

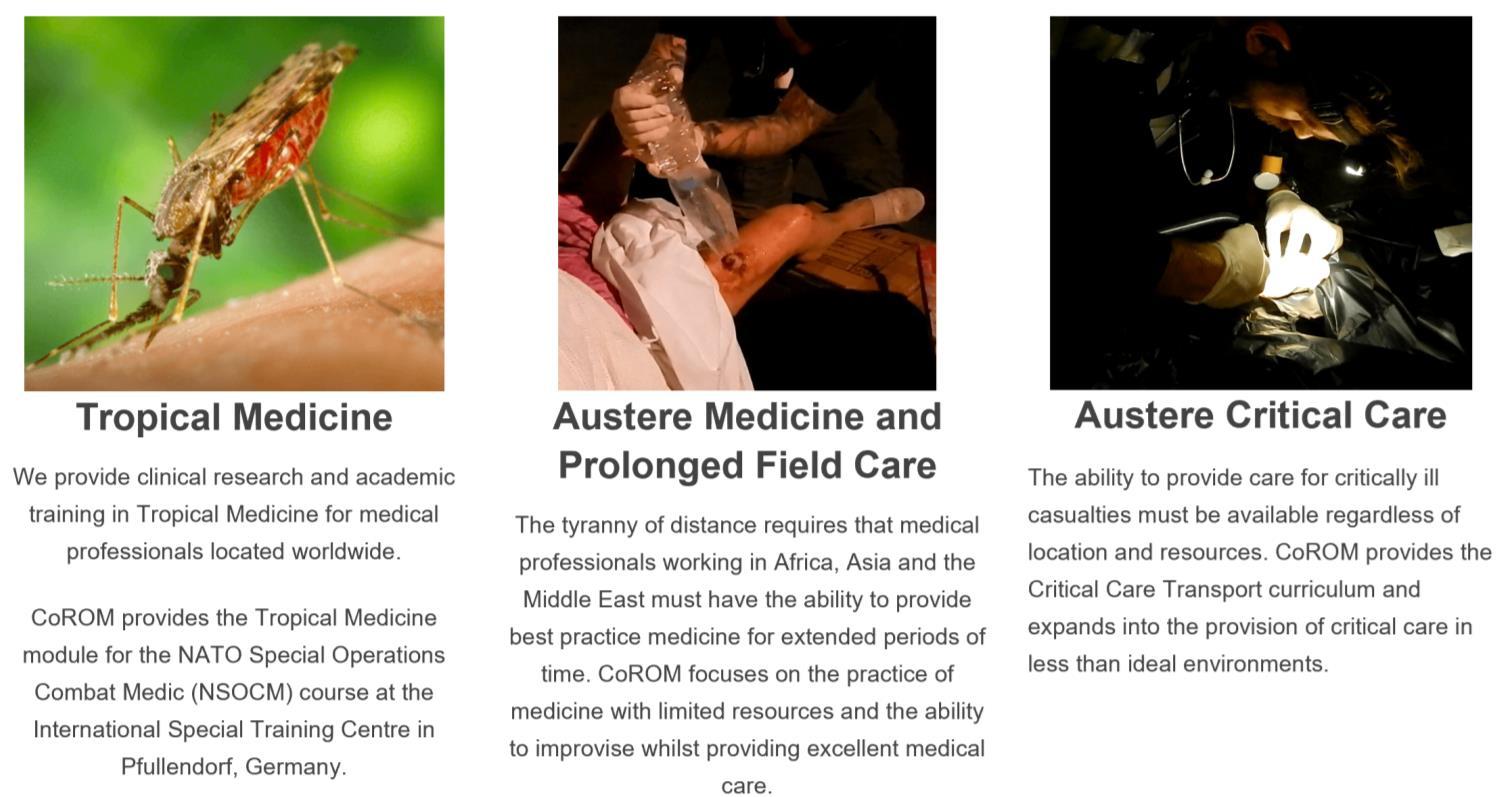

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionalsworking in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

NORWAY

TTEMS (closed course) 6-17 November

MALTA

ACLS 28 April 29 April 30 April

1 May

2 May

TTEMS 31 May-4 June

ATTEMS 7-11 June

PARSIC 16-17 August

ITLS 18 August

Prehospital

skills course 19 August

RPP104 30 Aug – 18 Sept

Suturing Fundamentals 15 April

SOMSA Conference 28 June – 2 July

Tactical Medicine Review (O’Kelly)

2021 Tropical Medicine Updates (Jarvis)

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

Higher Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Cert Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene (in accreditation process)

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Degree Courses

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine

August dates TBD

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

MSc Austere Critical Care (in accreditation process)

MSc Leadership in Healthcare (in accreditation process)

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitudes

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

iCARE Intensive Care for Remote and Austere Environments

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert

Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104

Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (classroom learning)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org

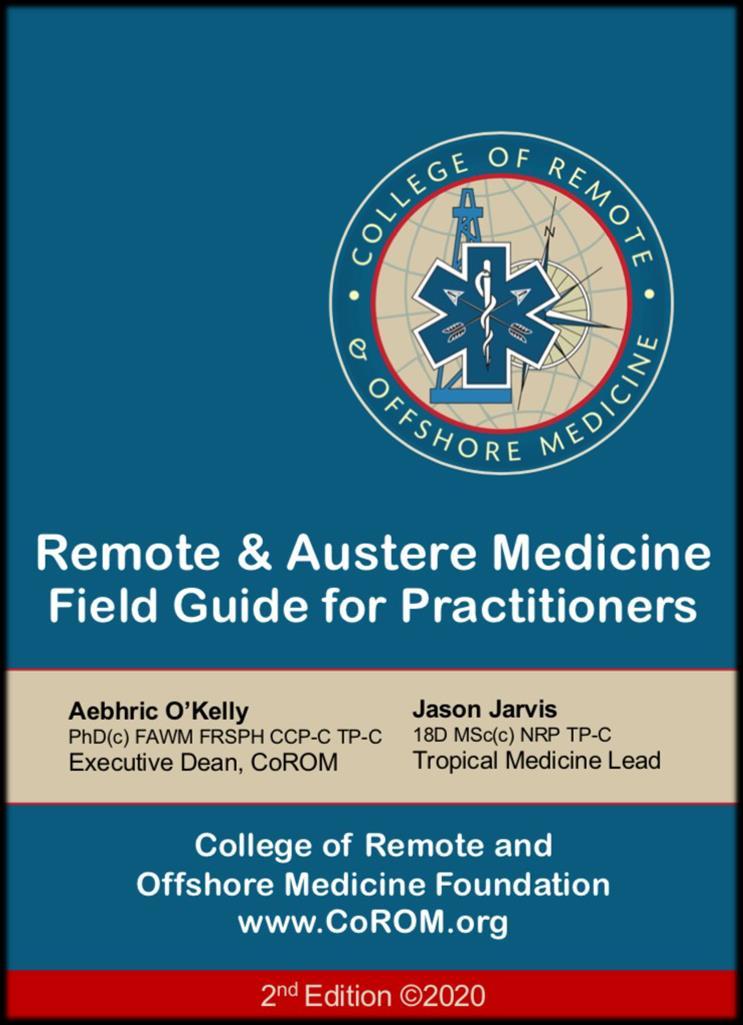

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E, MA FAWM, DipPara, CCP-C, TP-C CoROM Executive Dean

Jason Jarvis 18D, BSc, NREMT-Paramedic CoROM Tropical Medicine Lead

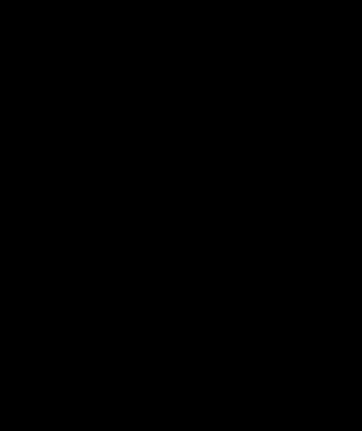

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

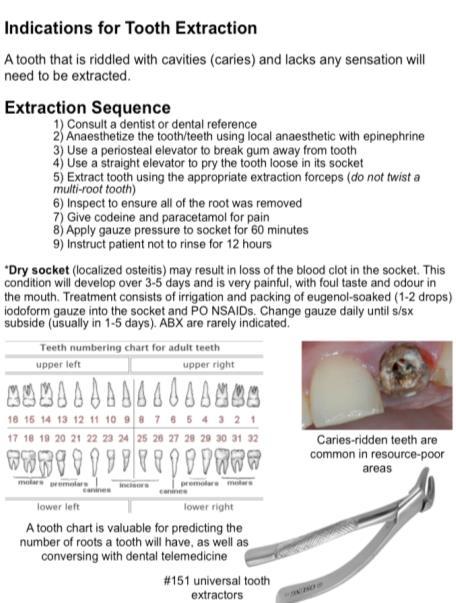

Dentistry

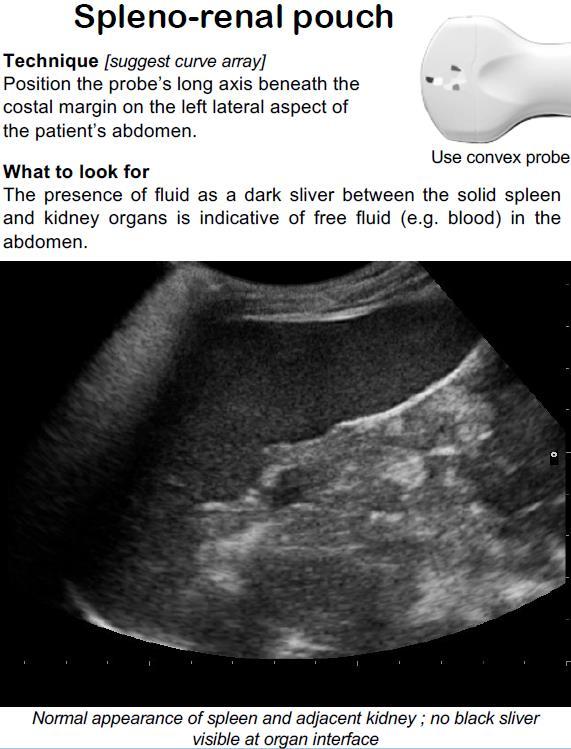

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

Canine medicine

…and much more!