Spring 2020

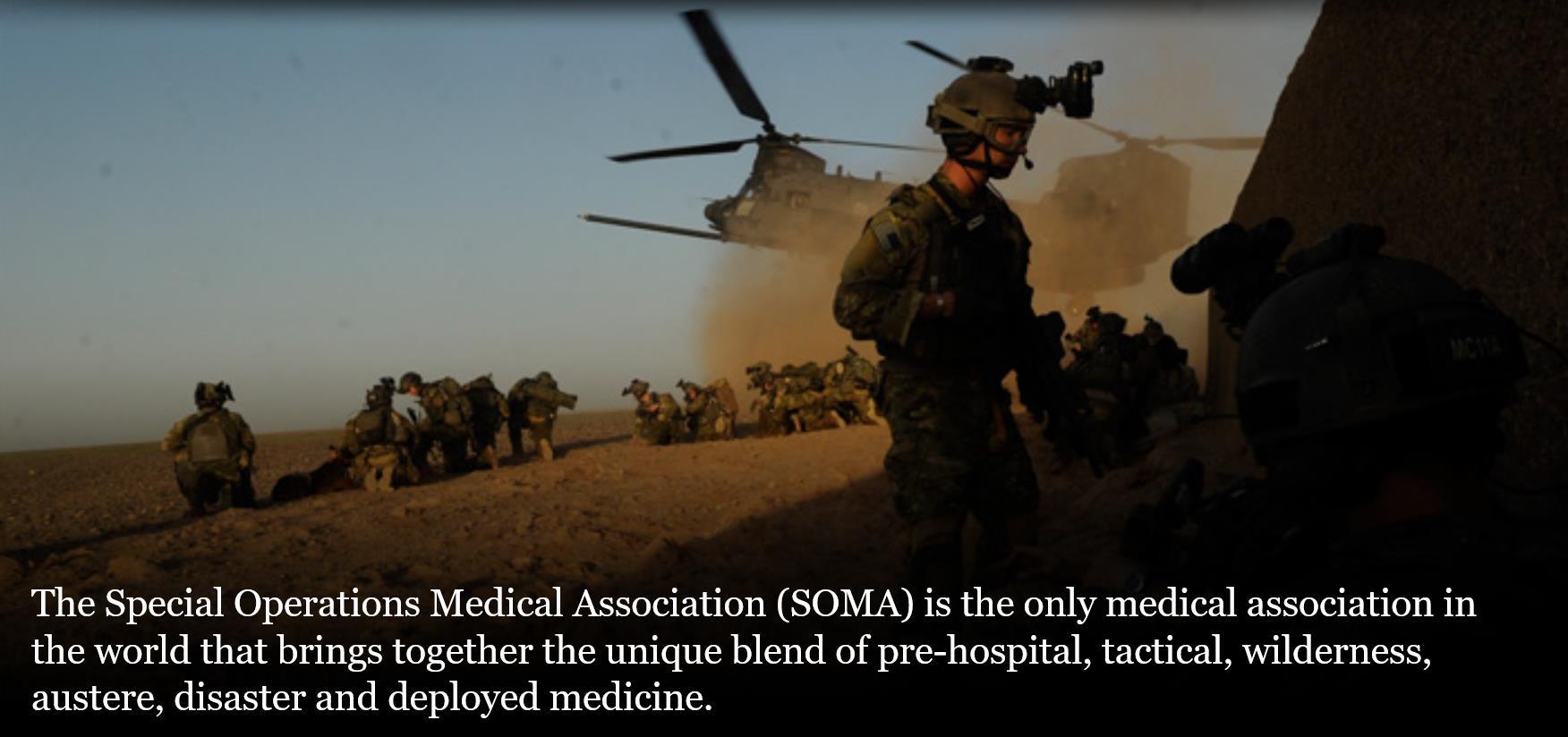

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntaryAcademic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

The College has been busy over the winter months. We began a research project on the forested slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, working with the Kibosho District Hospital to ascertain the prevalence of hypertension among the remote mountainous inhabitants. Remarkably, we found that one third of the population suffered from severe hypertension with a systolic blood pressure over 180; several of these individuals registered systolic blood pressure readings in the 240s.An additional third of the population were shown to have normal hypertension. The College will publish these findings as it continues to support research projects in the region.

This spring semester sees our first cohort of Higher Diploma students coming for their paramedic classroom training and testing. We have seven delegates who have made it through the gruelling online coursework and are now prepared to apply their head knowledge to hand knowledge.

The College has been invited back to run two workshops at the Special Operations MedicalAssociation’s ScientificAssembly this May in Raleigh, North Carolina. If you are in the area, stop by our exhibition table and say hello.You are also very welcome to attend our two workshops: Tactical Medicine Review and Tropical Medicine.

Following the medical workshops in North Carolina, we will return to the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany to run our Tropical Travel and Expedition Medical Skills course as part of the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic course. The major difference this year is that we have been invited to run theirAustere Medicine Week as well as our Tropical Medicine Week. We will be teaching improvised medicine, austere laboratory skills, preventative medicine and other topics associated with running a clinic in remote, austere and resource-limited environments.

It will be some busy times for the College in the next few months.

It is good to see that not only our students but also our faculty are busy with their professional studies. I wish you all every success.

At the SOMA2020 meeting I have asked to talk on burns in prolonged field care, and I look forward to meeting up with some of you.

This week we will be meeting the SBLS educational charity who have asked that the on-line pre-hospital module of their Burns Master’s degree apply for CoROM accreditation.

In the next few months I will be winding down my NHS job towards retirement and I look forward to handing over to the next generation of instructors.

Finally, I wish that 2020 is a good year for you all both professionally and personally.

Special Operations Medical Association Scientific

Assembly 11-15 May

Tactical Medicine Review with IBSC exams

High Impact Tropical Diseases and Malaria workshop

MALTA

ITLS 22 March

TTEMS 23-27 March

ATTEMS 30 March-3 April

Ultrasound Fundamentals 28, 29, 30, 31 March, 1 April

FiCC 6-10 April

PALS 13-14 April

PARSIC 15 April

ACLS 16-17 April

REMT 9-14 November

ITLS 15 November

TTEMS 16-20 November

ATTEMS 23-27 November

RAMS 30 November-4 December

RMLS Spring Semester 2021

FiCC 5-9 April 2021

Suturing Fundamentals

28 April

21 July

7 October

GERMANY

NSOCM Austere Medicine & TTEMS

11-22 May (closed course)

CMC Conference TropMed workshop

1-2 July

Advanced Certificate & Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

TANZANIA

TTEMS 3-7 August

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitudes

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

NSOCM NATO Special Operations Combat Medic course

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

REMT Remote Emergency Medical Technician

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org. Please address newsletter correspondence to editor@corom.org.

Tom Otten started out his career in the Belgian military as a Paracommando with missions to Afghanistan. Before working in the medical field he was a rope technician and there he started taking first aid courses and quickly climbed the ladder to EMT certification and onward to paramedic. After gaining medical experience in Iraq, South Africa and Europe he is now conducting medical training and Hostile Environment Awareness Training (HEAT) courses around the world.

Tom Otten EMT-Paramedic

Where am I now, where am I not…life became busy after my training with CoROM. I hoped to gain some adventure and doing an important job again after the military, and all of this came to pass after my training with them. At the time of this writing I am in Kenya, having just delivered a medical training course. Being in Kenya was not exactly part of my plan but life is full of surprises…

After my medical training I did clinical placements in Johannesburg, and a few months later I landed my first big job as a paramedic in Iraq as part of a Close Protection (CP) team. I was lucky because a lot of these missions are the same grind every day and even boring, but in this position, we went to new places almost every day. We worked always in small teams, everywhere from cities to remote places. We had EOD (explosive ordnance disposal) guys with us and we always went to places where mines, UXOs (unexploded ordnance) or other dangerous materials were found in order to clear them. While in Iraq I even had the privilege/luck to work with U.S.Army flight paramedics.

Once we cleared places such as schools or factories of explosives, the locals - with foreign aid assistance - could rebuild these places and start bringing the “normal life” back. Some crazy stuff happened when we were there but luckily no serious injuries.

In between missions I ran a lot of medical training for locals and team members. In the process, I found out I am good at delivering medical training and making complicated things simple; I also enjoyed teaching people how to take care of themselves or others. What I like most is to give people knowledge so they can adapt to changing situations, not only give them the how to do it, but the why …if they understand, they can adapt.

Running medical training gave me a lot of satisfaction and made me feel that I could make a bigger difference in showing people how to save lives than to occasionally save one myself. At the end of the day I will not be around all the time…so other people must know how to fix things. That is also the reason why I started doing medical training, because it is so important for everyone to know life saving skills - and it’s just great fun to do in my opinion.

After a few deployments I was contacted by various companies wanting me to provide medical training for them. I thought why not, a change of scenery would be nice. Following my time in Iraq, I mostly performed medical training for offshore employees and NGOs. I combine this with teaching HEAT courses in countries all over the world, such as Lebanon, Iraq, Kenya, South Sudan, South Africa and all over Europe.

Sometimes I miss the adventure of giving real medical care, but at the same time teaching people the skills I have learned from CoROM and in my career is very rewarding.

For the amazing teaching and professionalism, many thanks to Aebhric and his team. If anyone is looking to become a medic, I recommend this college!

Hope to see you guys again someday.

An epidemic occurs when the pathogen, host and the environment create an ideal situation for disease spread. Low vaccination rates, poor nutrition, age (young and elderly), and poor health all contribute to the spread of infection. Overcrowding, poverty, limited access to appropriate water, sanitation and hygiene measures, climate change and natural disasters can lead to conditions that allow easier transmission of disease.

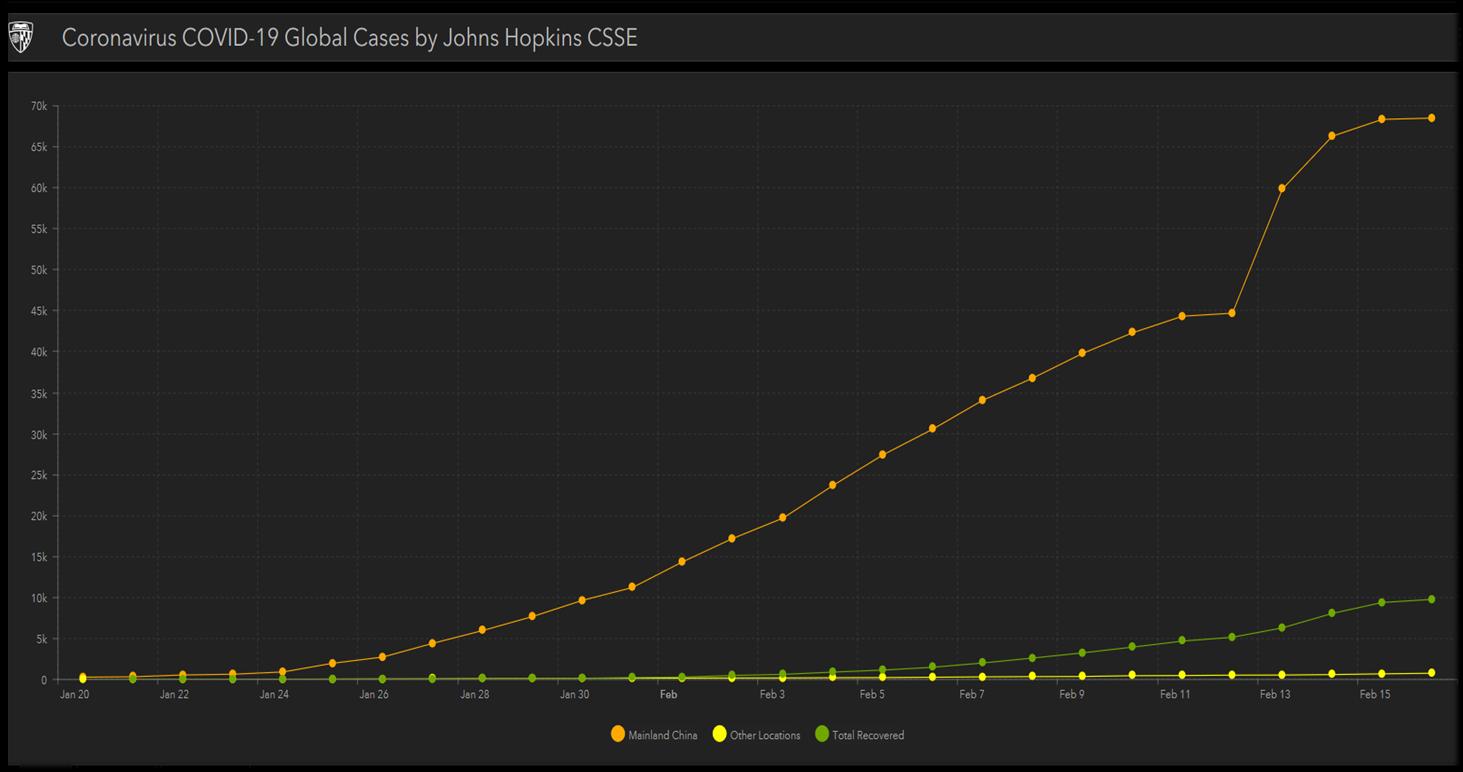

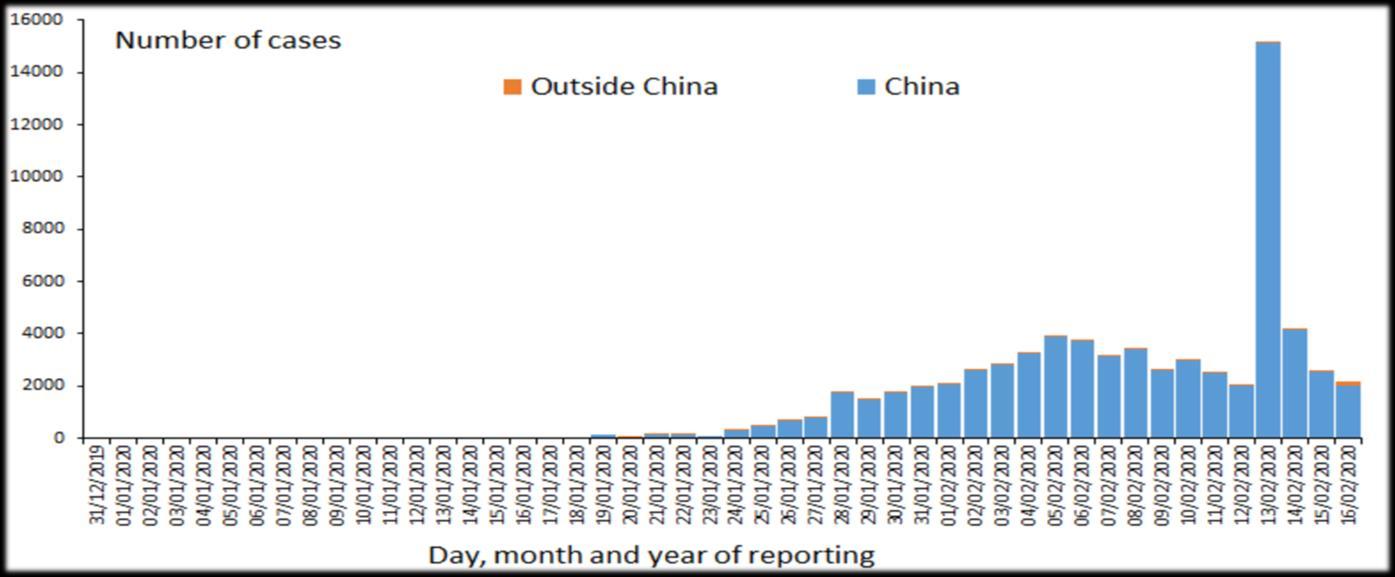

So how do organisations, governments and individuals deal with communicable disease epidemics? From viral gastroenteritis in a mining camp, to national E-coli outbreaks, to the current coronavirus pandemic, there are certain steps involved to contain, control and reduce the impact of infectious diseases. These steps are usually implemented concurrently, and the data collected is constantly used to refine and revise containment and treatment. This article will use the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as an example of communicable disease control.

Note: There is a plethora of information (some correct, some not so correct) concerning COVID-2019 that originated in Wuhan, China in November 2019. Information and data is being updated daily and beyond the scope of this article. The most up to date information about this current public health emergency of international concern can be found at:

World Health Organisation –https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

ProMed International Society for Infectious Disease –www.promedmail.org

Johns Hopkins CSSE

https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf

An outbreak is an increase in the frequency of a disease above what is expected in a given population

what is the normal baseline for a disease in the area? On December 31, 2019, the Chinese government alerted the WHO of several influenza-like illness cases in the Wuhan province of China. The live seafood and wild animal market was identified as the likely source of the illness on January 1st, 2020.

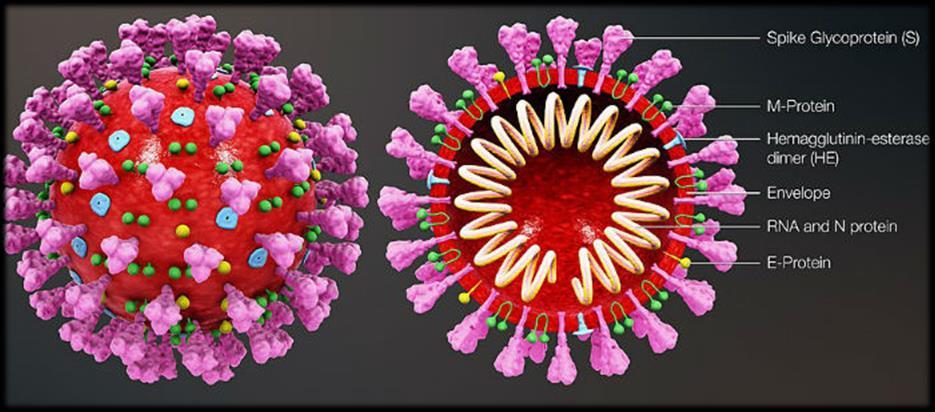

January 6, 2020: SARS, MERS, and H5N1 avian flu ruled out. Gene sequencing identified the disease as a Betacoronavirus, subgenus Sarbecovirus and mixed with SARS-like strains. It is temporarily given the name 2019-nCOV. Human to human transmission is unknown. Temperature screening is begun at major airports out of China’s Wuhan province.

Using line listing / spreadsheet, case definition should include 4 components: time, place, person, clinical aspects.

Suspected cases - Patient with severe acute respiratory infection (fever, cough, and requiring admission to hospital), AND with no other aetiology that fully explains the clinical presentation AND a history of travel to or residence in China during the 14 days prior to symptom onset OR patient with any acute respiratory illnessAND at least one of the following during the 14 days prior to symptom onset: contact with a confirmed or probable case of COVID-2019 infection, or worked in or attended a health care facility where patients with confirmed or probable COVID-2019 acute respiratory disease patients were being treated

Probable cases -Asuspect case for whom testing for COVID-2019 is inconclusive or is tested positive using a pan-coronavirus assay and without laboratory evidence of other respiratory pathogens.

Confirmed cases -Aperson with laboratory confirmation of COVID-2019 infection, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms.

Orient the data in time, place, and person using an ‘epi curve’that plots the number of cases against the time of onset of illness (minutes, hours or days). These graphs can assist with trending (containment or spread), magnitude, duration of the outbreak and possible incubation period.

Conduct outbreak investigations – active surveillance, environmental studies, identify sources of infection, means of transmission and the population at risk.

Original host: Unknown – possibly bats

Transmission: Zoonotic – Human to human (limited) via respiratory droplets, fomites and contact

Severity: Unknown (approximates) – Mild: 80%, Severe: 16%, Case fatality rate: 2-3%

Incubation period: 1-24 days with median estimates of 3-6 days

Infectious period: Unknown

R naught: Unknown – modelled between 2 and 3

Diagnosis: Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) through respiratory and serum samples. The WHO has shipped 250,000 test kits to more than 159 reference laboratories globally, as of early February. CT and chest radiograph are also being used in lieu of availability of RT-PCR.

Treatment and vaccine options: Supportive treatment, no vaccine available (in development, approximately six months)

It is thought that the spread of COVID-2019 began in a live seafood market which also sold exotic and wild animals. It is the close proximity of these animals and the spread of disease between closed caged animals that has allowed for a mutation of this strain of coronavirus and allowed for the jump to humans. At this stage, it is unknown if COVID-2019 will maintain its limited human-to-human transmission (rather than sustained transmission) and if the travel restrictions and isolation of 18 million people will retard the spread of this disease.

Prevent further transmission by breaking the connection between host, pathogen and environment:

Individuals: self-quarantine, cough hygiene, hand washing, appropriate PPE, disinfection, timely reporting of illness to appropriate health providers.

Nations: Quarantine, isolate, enact travel restrictions and public health emergency measures, continue to assist in the research and development of treatment options and vaccines.

Due to the speed of spread of COVID-2019 and the international economic impact this disease has had, the WHO declared this outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on the 31st January 2020.

The WHO are releasing daily situation reports and countries that are affected are also providing up to date country specific information. The battle of misinformation is ongoing, with various myths and misinformation being spread. Until more definitive data is provided about COVID-2019, the battle of misinformation continues.

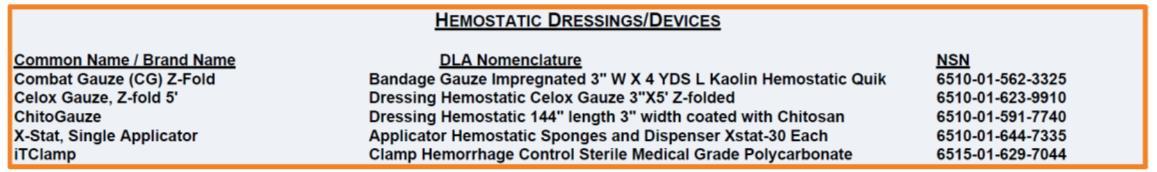

The iTClamp® is a novel hemorrhage control device that has recently become a member of the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) list of recommended devices. With the array of hemorrhage control devices becoming more numerous by the day, I feel compelled to give readers a glimpse of the lay of this land, and where I believe the iTClamp® best fits into that terrain.

Hemorrhage control is at once the most basic of trauma care skills yet becomes more and more nuanced the further one delves into the subject. It is important to remember that there are no one-size-fits-all approaches to hemorrhage control.

I divide hemorrhage control techniques into two broad categories: mechanical and nonmechanical. By mechanical I am referring to the application of a solid object to the patient, such as a tourniquet. Nonmechanical techniques function in the abstract and involve manipulation of the blood pressure, capillary constriction, or the blood’s ability to coagulate; a list of these techniques includes limited-duration permissive hypotension, the use of local anesthetics containing epinephrine, topical or parenteral tranexamic acid, and prevention of hypothermia.

In virtually any scenario involving massive external bleeding and the presence of only one or two caregivers, the application of mechanical techniques should precede nonmechanical techniques, though it is theoretically possible (but seldom practical) to perform them both simultaneously. For example, in a massively hemorrhaging casualty with gunshot wounds to the legs and abdomen, administration of tranexamic acid and hypothermia prevention should happen as soon as possible, but not before tourniquets have been applied to the legs and the body has been fully exposed in the search for additional injuries. Hypothermia prevention in this case may be applied in piecemeal fashion (as soon as a given part of the body has been cleared of injuries). Once vascular access is obtained – following the placement of tourniquets – tranexamic acid may be given in order to mitigate internal abdominal bleeding. In addition, this patient will likely benefit from permissive hypotension, a practice also known as hypotensive resuscitation.

I divide mechanical techniques into basic, intermediate and advanced categories.

Basic mechanical techniques work most of the time for most types of external bleeding and require minimal technical proficiency or technology to apply. These include direct pressure, tourniquets, wound packing (using inert gauze/fabric and/or a gauze-type hemostatic agent) and simple pressure dressings.

Intermediate mechanical techniques are used in external bleeding cases in which application of a basic mechanical technique won’t work (or is delayed) or serve as adjuncts to a basic mechanical technique. These techniques are more technically demanding and generally require a higher level of knowledge of human anatomy than do the basic techniques. Some have specific equipment requirements, though improvisation may overcome a gear shortage in most instances. Techniques in this category include arterial pressure points, junctional tourniquets, complex pressure dressings, syringe-injected hemostatic agents and other non-gauze hemostatic agents, cautery, indirect pressure of the skull, traction of the femur, splinting of impaled objects, splinting of bone fractures, urinary catheter balloons, oversewing, and reapproximation of the superficial tissues (such as the scalp).

Advanced mechanical techniques include procedures such as vessel clamping/ligation and use of the REBOAdevice.

Following the rationale of the previous section, I place the iTClamp® mainly into the category of intermediate mechanical techniques. It is my opinion (and experience) that this is a device best used in the management of facial or scalp hemorrhages. Scalp bleeding is usually copious, even when the only severed vessels are capillaries. This has to do with the great abundance of capillaries in the scalp (ostensibly to nourish the hair follicles) and the unique inability of scalp capillaries to constrict when severed. Capillary bleeding from the scalp is therefore high volume yet low pressure, and it is standard clinical practice to stop such bleeding via reapproximation of the scalp – typically performed via fingertip pressure followed by application of sutures, staples, Raney clips, or apposition using the patient’s hair. The iTClamp® can provide quick hemostasis of scalp wounds, after which the device may be replaced (ideally under local anesthesia) with a lower-profile closure device at the practitioner’s earliest convenience.

In this new series, we will look at a disease or case study, that while not overly common in the developed world, may well present to the remote or austere medic. In this edition of Compass, Neil Coleman takes a look at tuberculosis.

TUBERCULOSIS

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Head of Undergraduate Studies

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Head of Undergraduate Studies

When working as a remote medic, we are often employed in low-to-middle income countries. In line with this, healthcare in these countries is often fragile and financially limited.

So, the first things you need to know about tuberculosis (TB) are:

It is a disease that is spread by infected persons (e.g. coughing bacteria into the air)

It is contagious

It is bacterial in nature

It is the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent ranking (above HIV/AIDS)

It is among the top 10 causes of death worldwide

Clinical Facts about TB

TB is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) It is a highly communicable disease, and most commonly affects the lungs, which is known as pulmonary TB (when affecting other organs, it is known as extrapulmonary TB). The World Health Organisation estimates that about one quarter of the world’s population is infected with M. tuberculosis, and therefore at risk of developing the disease. According to United Nations population statistics, approximately 1.9 billion people have either active or latent TB.

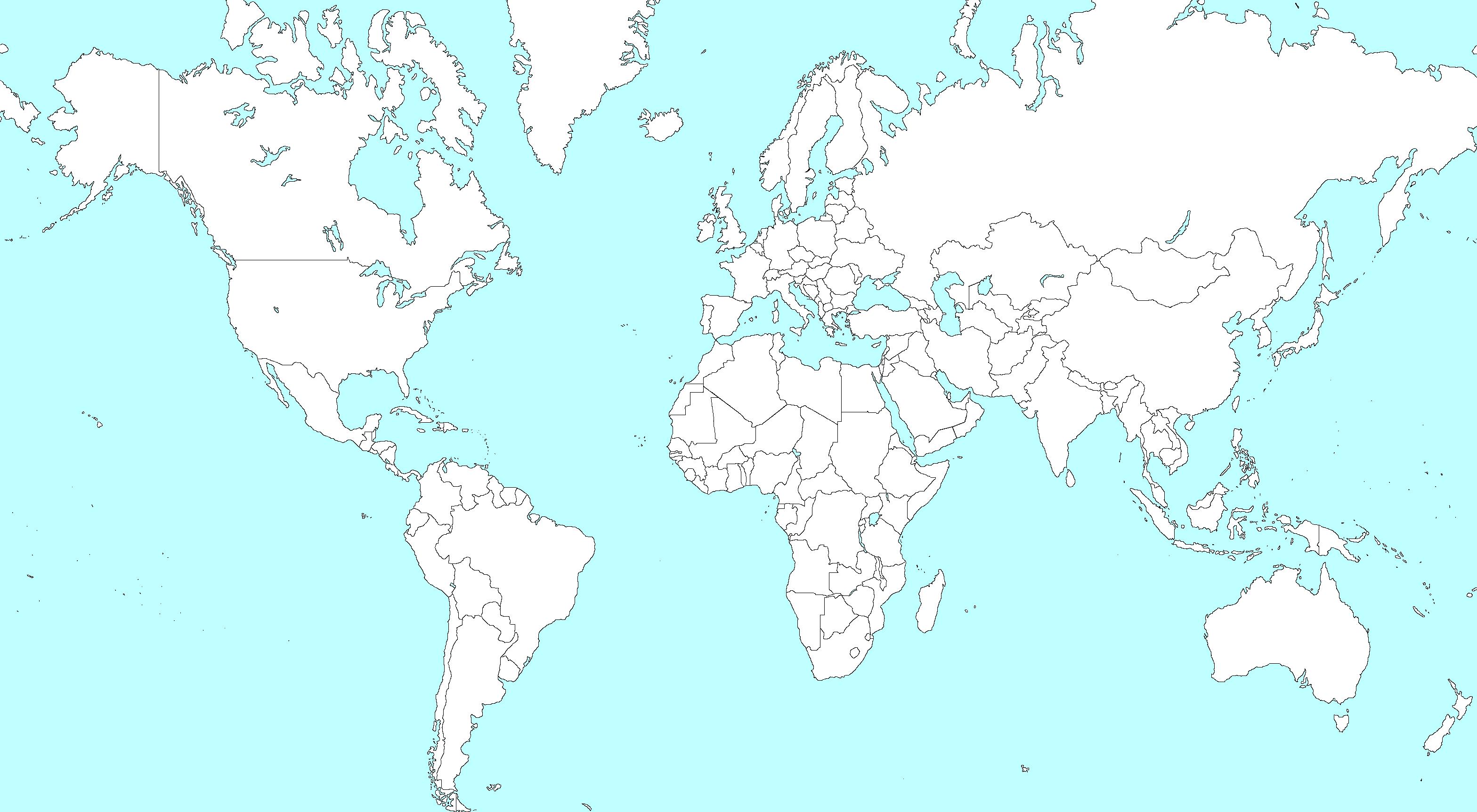

In 2018 (the most recent year that statistics are available for), there were an estimated 10 million new cases of TB. It is worth noting that 8 countries accounted for 66% of those new cases. These countries were: India, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and SouthAfrica.

In the same year, 1.5 million people died from TB, with an estimated 251,000 of those deaths occurring in patients who were HIV-positive.

In most developed countries, the incidence of new cases is very low. New case incidence in the UK, the U.S. andAustralia for the examined year was 3/7/7 per 100,000, respectively. In contrast, South Africa had 520 new cases per 100,000 population, while the global average was 130 per 100,000. Another point the remote medic should consider is the likelihood of a given patient receiving treatment.

Peru has a population of about 32 million. In 2018 they reported 39,000 cases of TB. They were able to treat 80% of patients and incurred 2,700 deaths.

Ghana has a population of 30 million. In 2018 they reported 44,000 cases of TB. Only 32% of these patients received treatment, with a resulting 16,000 deaths.

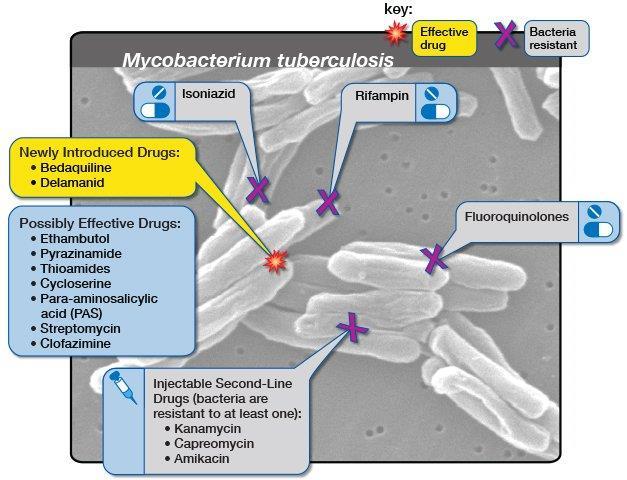

Drug resistant TB continues to be a problem for healthcare systems. About half a million cases of drug resistant TB were reported in 2018, with 78% of those cases being reported as multi drug resistant rather than just rifampicin resistant TB (rifampicin is the antibiotic most used for treatment of TB).

Contributing factors

The WHO have identified factors that contribute to the chances of TB infection in an individual. These include:

Smoking

Diabetes

Harmful use of alcohol

HIV

Undernourishment

Signs & Symptoms

Apatient who harbours the TB organism but is not actively infected by it (i.e. their immune system is effectively managing the infection), is referred to as having latent TB. In this stage, most patients will be asymptomatic (showing no symptoms). Active TB, or TB that is symptomatic, is suspected when the patient presents with signs and symptoms that may include:

Persistent cough lasting more than 2 weeks

Fever lasting more than 2 weeks

Noticeable loss of appetite

Sudden weight loss

Night sweats

Swelling of the lymph nodes of the neck

The risk of contracting the active form of TB is higher in:

Young patients or elderly patients

People who have contracted the disease within the last 5 years

People who have received inadequate treatment for TB in the past

Testing

The Mantoux skin test uses purified protein derivative (PPD)

Testing for TB is usually conducted by a skin test (purified protein derivative test) and/or a blood test. The skin test involves injecting a small amount of PPD into the patient’s dermis, usually on the forearm. If a red lump develops over the next 2-3 days, this is taken as being an immune reaction to the PPD. If a patient doesn’t return for the follow up exam in the 2-3-day timeframe, they will need to have the test conducted again. These tests cannot differentiate between latent and active TB, so a sputum test and chest x-ray will often be required. Aremote medic constrained by scarce resources may not be able to run these additional tests for his or her patient.

All patients who test positive for TB require treatment, irrespective of whether it is latent or active.

Treatment for tuberculosis may seem surprisingly simple, at least in theory. Acourse of antibiotics is recommended; however, the medic should note that the duration of the course will be entirely dependent on the strain of TB and how resistant it is to the medications. The course of antibiotics may last from 12 weeks to 9 months.

In the face of drug resistance, antimicrobial treatment of tuberculosis grows more difficult every year

In many jurisdictions the remote medic cannot realistically be expected to eradicate TB. However, early recognition and taking measures to prevent spread of the disease would be considered part of their remit.

In this regard:

Wear masks when treating patients suspected of being TB-positive Ventilate rooms

Avoid contact with infected persons if possible

Diagnose early and refer out for further testing/treatment

Conclusion

Tuberculosis is common in resource poor countries and is a major cause of mortality. Patients with compromised immune systems are at higher risk. It is a highly communicable disease and the key role of the remote medic should be based around early recognition/treatment and prevention of further transmission.

Author

Neil Coleman is the Head of Undergraduate Studies for CoROM. He is an Advanced Care Paramedic andAssistant Professor of Emergency Medical Science.

Which term best describes the following arrhythmia?

A. 3° AV block

B. PVC triplets

C. PVC trigeminy

D. Junctional escape rhythm

The senior lab technician at a hospital in Cambodia tasks you with the creation of a new batch of surface decontamination bleach (diluted sodium hypochlorite).You recall her telling you to add 15% sodium hypochlorite to distilled water to create six liters of 0.5% solution but cannot remember how much 15% sodium hypochlorite she said to use.After working through the problem you decide on what volume of 15% sodium hypochlorite?

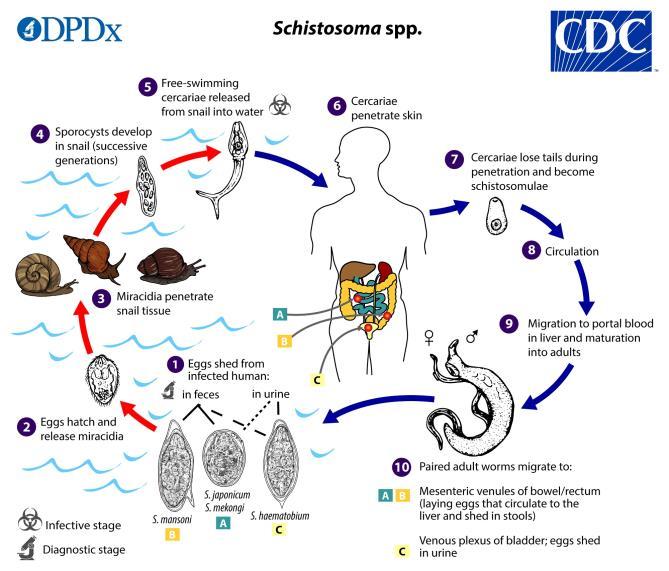

You are the healthcare provider assigned to an executive protection team and have escorted your principal and his family to an economic summit in Finland. At the conclusion of the six-day event the principal’s 20-year-old son comes to you complaining of itchy papules on his feet and ankles. Your subjective investigation reveals that he took his little sister to a rural petting zoo four days ago and had contact exposure with many species of agricultural animals. In addition, he swam in a nearby lake yesterday that was closed for reasons he was not able to discern from the Finnish-language warning signs posted along the shore. What is your working diagnosis?

A. Scabies infestation

B. Cutaneous anthrax

C. Cercarial dermatitis

D. Echinococcus multilocularis

Answers will appear in the Summer 2020

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: Premature junctional contraction

Clinical calculation: 67 drops/minute infusion

Clinical case: Methylene blue for the treatment of methemoglobinemia

Medical References (Dean’s picks)

Gear Nurugo Smartphone Microscope available at amazon.com

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Winter 2019, Vol 19, Edition 4. 19(4). 91-93.

Bradley KD.

Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have seen expansion with their application in many fields, including the opportunity these tools offer to improve medical care. Drones have significant potential for use in the tactical setting. New, unique possibilities for these drones are emerging constantly, but there is no standardized inclusion specifically with tactical medicine operations. This article is a review of the future possibilities of drones, the associated risks that drones present, and the current application of drone technology in the field of civilian operational/tactical medicine.

The New England Journal of Medicine N Engl J Med 2019;381:2519-28.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812165.

Arminder K. Deol, PhD., Fiona M. Fleming, PhD., Beatriz Calvo-Urbano, PhD., et al.

All but one country program (Niger) reached the disease-control target by two treatment rounds or less, which is earlier than projected by current WHO guidelines (5 to 10 years). Programs in areas with low endemicity levels at baseline were more likely to reach both the control and elimination targets than were programs in areas with moderate and high endemicity levels at baseline, although the elimination target was reached only for S. mansoni infection (in Burkina Faso, Burundi, and Rwanda within three treatment rounds). Intracountry variation was evident in the relationships between overall prevalence and heavy-intensity infection (stratified according to treatment rounds), a finding that highlights the challenges of using one metric to define control or elimination across all epidemiologic settings.

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine

December 2019, Volume 30, Issue 4, Pages 401-406.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2019.06.002.

Aldon J. Whitehead, Nathan W. Nelson, Lacy

These data suggest that both St. John’s wort and white oak are potential candidates for infection prophylaxis and therapy in austere wilderness scenarios, with St. John’s wort being the more potent agent. White oak may be more logistically feasible because the larger surface area of a white oak tree allows for harvesting a larger quantity of bark compared to the smaller surface area of the St. John’s wort plant.

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) grows on six continents. The plant contains seven groups of medicinally active compounds, including naphthodianthrones, which are found in the black dots along the flower petals.

Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75:218-220.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.09.002. Pat Croskerry, MD, PhD.

Without good decisionmaking, lapses in rationality are inevitable, and ultimately patients will be failed. The essence of clinical decisionmaking is embodied in the diagnostic process, yet we are said to fail in emergency medicine about 10% to 15% of the time. The good news is that we are becoming more aware of the critical role of decisionmaking. The scoping review of clinical reasoning in emergency medicine, published in this issue of Annals, provides a useful depiction of the scope and breadth of our knowledge in this burgeoning domain, and is reflected in an encouraging increase in published studies in the last 20 years. As Pelaccia et al note, much of the focus has been directed at reducing the risk of error in the treatment of patients, and considerably less demanding than diagnostic failures, even though the latter are more common and do greater harm. This is probably because treatment errors are more tangible and less demanding than diagnostic errors. The diagnostic process is a complex act that may involve upward of about 50 discrete variables and therefore presents a considerably greater challenge in detecting and analyzing failures. Nevertheless, considerable ground has been gained recently, largely under the auspices of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine.

by Josh Waitzkin 2007

Free Press

Review by Jason Jarvis

by Josh Waitzkin 2007

Free Press

Review by Jason Jarvis

When a person proves him or herself capable of world-level mastery of multiple subjects as disparate as chess and martial arts, attention must be paid. Such a person is Josh Waitzkin, author of The Art of Learning

Waitzkin – catapulted to early fame as the young chess prodigy portrayed in the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer – was undoubtedly born with a keen intellect and highly competitive personality. While the vast majority of those gifted with such attributes might be content to lead comfortable lives of easy dominance over their less-talented peers, Waitzkin has instead cultivated a life dedicated to hard work, deep introspection, an obsessive eye for detail, and bridging the divide between theory and practice; in short, the relentless pursuit of excellence.

By his late teens, years of dominating international chess tournaments had honed Waitzkin’s Western, linear-thinking brain to a razor’s edge, but he eschewed the spotlight that had been cast upon him by Hollywood. A fortuitously timely reading of the Tao Te Ching led him Eastward, philosophicallyspeaking, ultimately landing him in a Tai Chi school in his hometown of New York City. Six years later, he won the Tai Chi Push Hands World Tournament in Taiwan. Since then, Waitzkin founded the JW Foundation, earned a black belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, and now spends his free time in the Caribbean mastering the art of foiling.

Waitzkin’s techniques are not for the unimaginative. His teaching methodologies read like a Jedi training manual, with esoteric-sounding principles like form to leave form, making smaller circles, and slowing down time. As he states succinctly in the conclusion to the book’s introduction: “A lifetime of competition has not cooled my ardor to win, but I have grown to love the study and training above all else. After so many years of big games, performing under pressure has become a way of life. Presence under fire hardly feels different from the presence I feel sitting at my computer, typing these sentences. What I have realized is that what I am best at is not Tai Chi, and it is not chess – what I am best at is the art of learning. This book is the story of my method.”

“The title is accurate – at a profound level, it’s about real learning from hard conflict rather than from disinterested textbooks.”

Josh Waitzkin, an eight-time National Chess Champion in his youth, was the subject of the book and movie Searching for Bobby Fischer.At eighteen, he published his first book, Josh Waitzkin’s Attacking Chess. Since the age of twenty, he has developed and been spokesperson for Chessmaster, the largest computer chess program in the world, currently in its eleventh edition. Now a martial arts champion, he holds a combined twenty-one National Championship titles in addition to several World Championship titles. He regularly gives seminars and keynote presentations and is president of JW Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to maximizing each student’s unique potential through an enriched educational process.

–Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

“Dr. Carol Dweck, a leading researcher in the field of developmental psychology, makes the distinction between entity and incremental theories of intelligence. Children who are “entity theorists” – that is, kids who have been influenced by their parents and teachers to think in this manner – are prone to use language like “I am smart at this” and to attribute their success or failure to an ingrained and unalterable level of ability. They see their overall intelligence or skill level at a certain discipline to be a fixed entity, a thing that cannot evolve. Incremental theorists, who have picked up a different modality of learning – let’s call them learning theorists – are more prone to describe their results with sentences like “I got it because I worked very hard at it” or “I should have tried harder.” Achild with a learning theory of intelligence tends to sense that with hard work, difficult material can be grasped –step by step, incrementally, the novice can become the master.”

- The Art of Learning

“We are built to be sharpest when in danger, but protected lives have distanced us from our natural abilities to channel our energies.”

- The Art of Learning

“The key to pursuing excellence is to embrace an organic, long-term learning process, and not to live in a shell of static, safe mediocrity. Usually, growth comes at the expense of previous comfort or safety.”

- The Art of Learning

Join

CoROMwillberunninganexhibitor’sboothaswellas hostingtwoworkshops:

HighImpactTropicalDiseasesandMalariaWorkshop

TacticalMedicineReview&IBSCExams

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

Snakes and arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS & diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

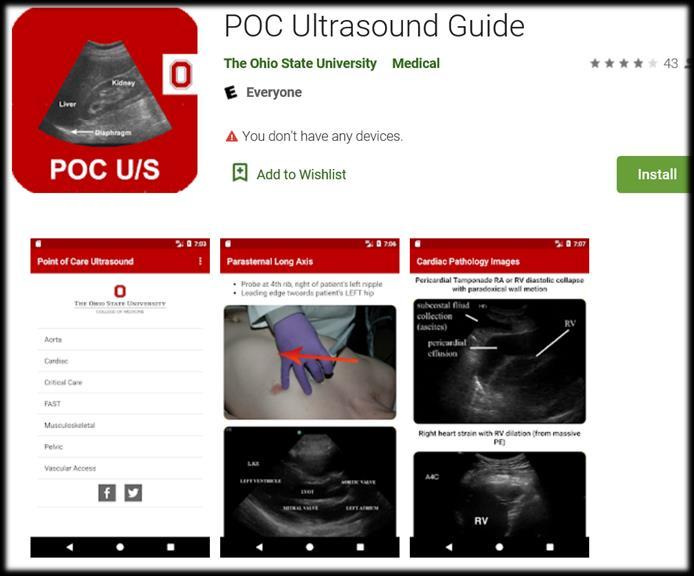

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory techniques

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

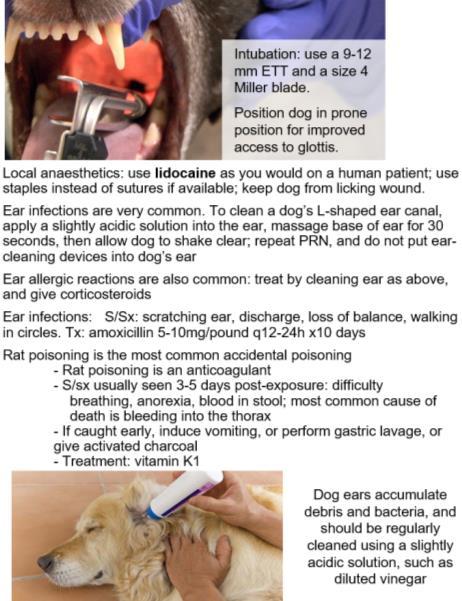

Canine medicine

…and much more!