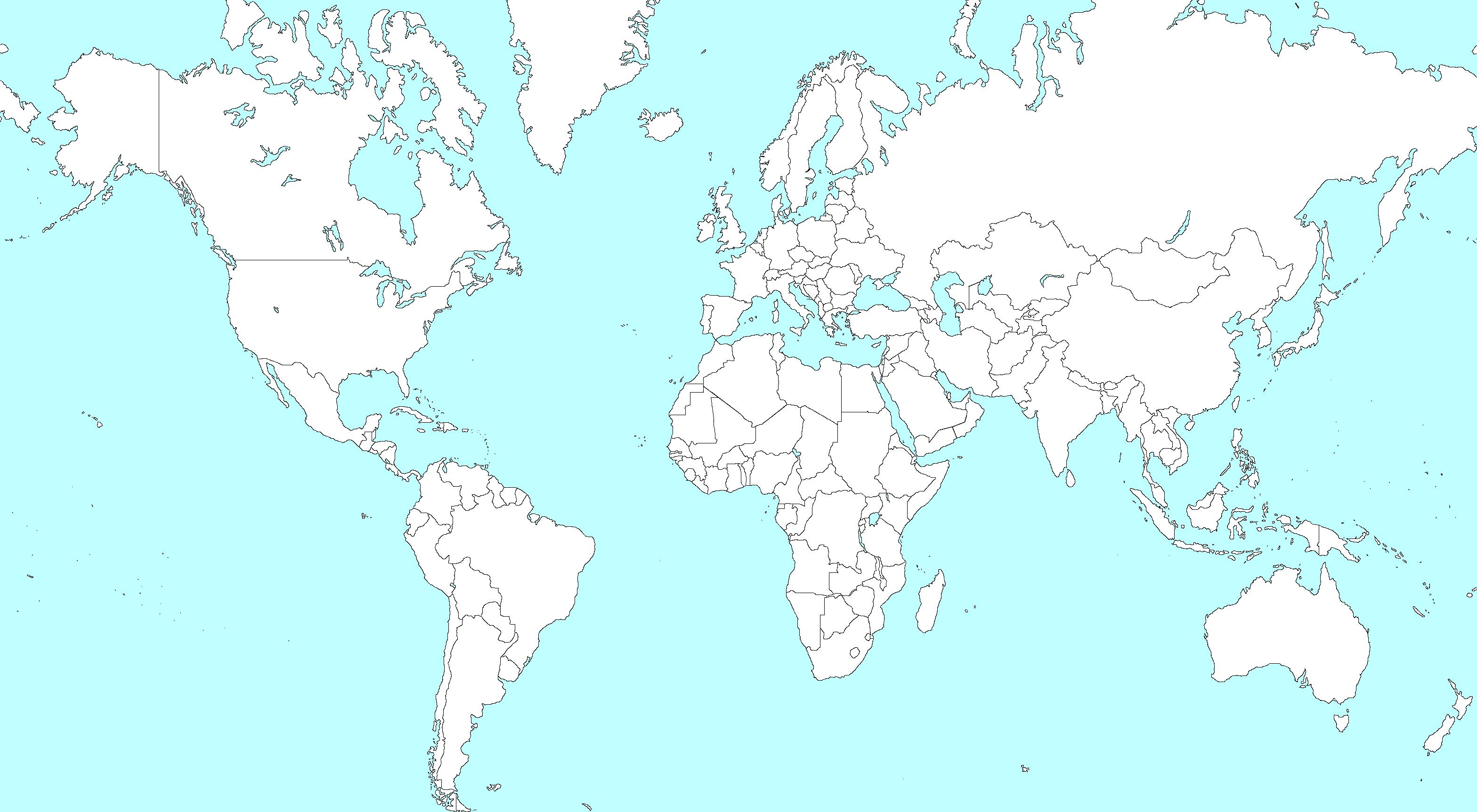

We are fortunate to have an excellent faculty and a dynamic student body that brings a unique perspective to medicine from across the world It is that perspective that we will bring to bear with our first ever continuing education conference we’re calling “Medicine in the Mediterranean” In the realm of medicine, it's crucial to stay up to date with the latest advancements and exchange knowledge across borders to provide top-notch patient care Taking place from February 2 to 4, 2024, in Valletta, the capital city of Malta, this conference is poised to be a valuable event for physicians, nurses, and paramedics worldwide

The Medicine in the Mediterranean conference presents a unique opportunity for healthcare professionals to convene, learn, and connect with an array of speakers from all corners of the world The event promises to feature cutting-edge presentations, innovative practices, and case studies that will broaden the horizons of austere medicine The conference committee is finalizing speakers and content, but I am super excited to see the quality of both It will prove to be a fantastic event The conference is planned to kick off on Friday evening, February 2nd and continue 0800h until 1430h Saturday and Sunday in Valletta Those who are interested (and qualified) can plan to stay for Monday that will be a dive rescue workshop in the waters off Malta that Diver Magazine recently ranked the top dive destination in Europe

Selecting Malta as the conference venue is a strategic decision that adds a special charm to the event. Malta boasts a rich history in medicine, and the Mediterranean backdrop creates a serene atmosphere that will enrich both learning and networking experiences. The island's history, culture, and breathtaking landscapes offer participants a chance to unwind and recharge between sessions, ultimately contributing to the conference's overall success.

Medicine in the Mediterranean holds the potential to be more than just a conference; it marks a stride towards nurturing a global community of CoROM faculty, students and alumni and other medical professionals who are committed to advancing austere and remote medicine through collaboration and shared knowledge. Attendees will not only learn from esteemed experts but also establish connections that could lead to new learning environments, future research partnerships, cross-border collaborations, and the exchange of best practices.

We are confident that Medicine in the Mediterranean will become a pivotal event. Mark your calendars for February 2 to 4, 2024, to be part of this diverse speaker lineup, engaging topics, and inspiring discussions on the transformative journey towards better healthcare. To find out more and to register, visit https://corom.edu.mt/medicine-in-the-mediterranean-conference/ See you there!

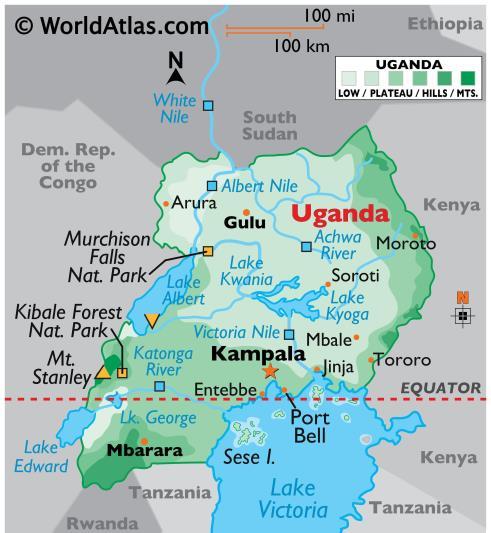

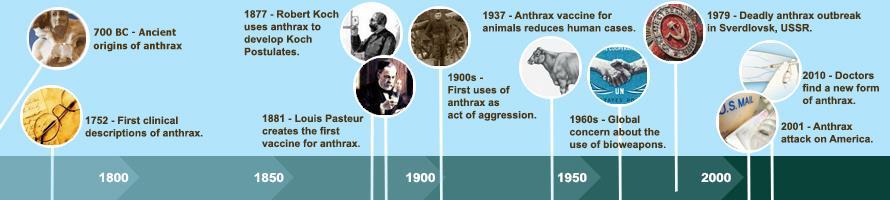

This issue of The Compass has a truly international flavor Trends in Traumatology showcases CoROM Senior Faculty Dr. Quinn’s latest data from the war in Ukraine, while the book review examines the 1979 Soviet airborne anthrax outbreak. Our case reports include a case in Australia from Dr. Shertz, and Dr. Geelhoed presents a fascinating surgical case he recently conducted in rural Uganda.

Besides these pieces, there is a trove of information contained within Aebhric O’Kelly’s Improvised Medicine, the Tropical Medicine Update (focused on recent outbreaks of anthrax), Test Yourself, Envisioning Information, Audio Files, Journal Watch, and the Resources sections.

I hope to see – and dive with – many Compass readers at the 2024 Medicine in the Mediterranean conference in Malta.

Sincerely,

Jason

20 September 2023

page 30

page 33

page

page 17

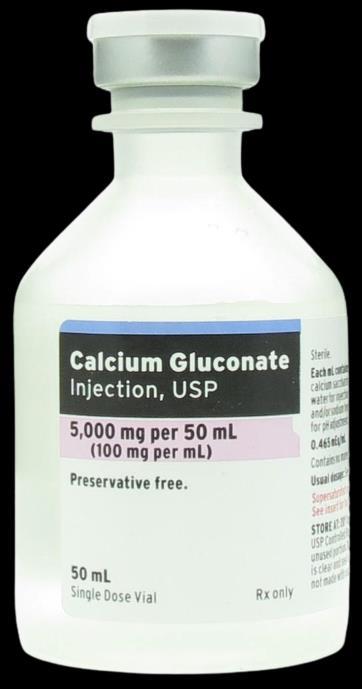

Octreotide 1.5 mg

9 September 2023

Jason Jarvis is CoROM’s Press Chair and an associate lecturer in Tropical Medicine. He is a paramedic and former U S Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan He recently completed his second transect of Africa, teaching predeployment medicine courses for UN peacekeeper clinicians in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya. Based in Seattle, Jason is a freelance medical educator who teaches advanced trauma courses, minor surgical procedures, ACLS, and PALS. He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for International Health, and is pursuing a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

A 53-year-old male oil platform worker presents to you complaining about three days of gradual right calf / leg swelling, pain, and tenderness. He returned to work at the platform five days ago after completing his vacation in Australia.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D MD DTM&H

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D MD DTM&H

He has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and non-insulin-dependent diabetes His medications include lisinopril, atorvastatin, and metformin

He denies any prior history of leg swelling, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, recent surgery, and has no cancer history

His vital signs are completely normal He denies any fevers, cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, strenuous activities, or trauma to the limb His physical exam is notable only for right leg swelling and tenderness

Differential diagnosis isn’t very broad High on the list is a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) Leg cellulitis can present similarly but would include spreading leg redness and frequently fever A calf muscle tear or Achilles tendon rupture would also be unlikely without any acute injury or sudden onset He has no history of significant lymphedema on that limb or risks for lymphatic filariasis

Routine laboratory testing available to you in the oil platform medical clinic is unhelpful

With a concern for a leg deep vein thrombosis, you request transport to the nearest mainland clinic with ultrasound capability There, the sonographer notes extensive DVT involving the peroneal, posterior tibial, and distal femoral veins The treating medical provider places him on oral anticoagulants for the next three months and returns him to the oil platform

Deep vein thrombosis is a thrombosis or “blood clot” in the deep veins of a limb. The vast majority occur in the lower extremity. Traditionally, Virchow’s triad was cited as the reason for these thromboses. The triad includes hypercoagulatory states, like the use of oral contraceptives, recent cancer, alterations in blood vessel flow from trauma, from casting after a fracture, prolonged sitting, and vessel wall / endothelial damage.

What likely caused this patient’s leg DVT? His plane flight from the oil platform to Australia was over 8 hours.

Asymptomatic calf DVT occurs 2.35 to 3.98 times more frequently in passengers with plane flights over 4 hours. The most feared complication of a DVT is embolism to the lungs, called pulmonary embolism (PE).1

In mild cases, PE only causes shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. In severe cases, it can cause hypoxia, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, pulmonary infarct, and death from right heart strain and arrhythmia. 11 of 61 inflight deaths undergoing autopsy after arrival to Heathrow Airport in a 1986 study died from PE: All involved flights over 6 hours.2

Most air travel-related DVT cases occur within two weeks of the flight.3 Asymptomatic leg DVT may occur in 1.6% of all airline passengers with no risks for clotting, but up to 5% with those felt to be high risk. Risk factors include estrogen use, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.1

Somewhat reassuringly, less than half of asymptomatic leg DVT becomes symptomatic. Only 10 to 20% of isolated calf DVT progresses proximally. Proximal progression sets the patient up for possible PE.4

How is DVT related to air travel? Prolonged sitting triggers decreased venous flow, systemic inflammation, and platelet aggregation.5 Greater than 1 liter of lower leg fluid retention is common in flights over 6 hours. Experts speculate that pressure from the edge of the seat on the back of the leg further interferes with venous return.1

How do passengers avoid DVT while flying? Below-the-knee compression socks with 14 to 30 mmHg compression have been shown to reduce the rate of DVT to nearly zero. There is no benefit to prophylactic aspirin, even at doses of 400 every day for three days. Being “mobile” for three minutes every hour of the flight as well as “stretching” your legs for 2 minutes in the seat every hour are recommended, but largely based on expert opinion without good studies to back them up.1

1 Aryal KR, Al-Khaffaf H. Venous thromboembolic complications following air travel: what's the quantitative risk? A literature review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006 Feb;31(2):187-99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.08.025. Epub 2005 Oct 17. PMID: 16230037.

2 Sarvesvaran R. Sudden natural deaths associated with commercial air travel. Med Sci Law. 1986 Jan;26(1):35-8. doi: 10.1177/002580248602600108. PMID: 3959826.

3 Marques MA, Panico MDB, Porto CLL, Milhomens ALM, Vieira JM. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis on flights. J Vasc Bras. 2018 Jul-Sep;17(3):215-219. doi: 10.1590/16775449.010817. PMID: 30643507; PMCID: PMC6326126.

4 Scurr JH, Machin SJ, Bailey-King S, Mackie IJ, McDonald S, Smith PD. Frequency and prevention of symptomless deep-vein thrombosis in long-haul flights: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001 May 12;357(9267):1485-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04645-6. PMID: 11377600.

5 Martin-Gill C, Doyle TJ, Yealy DM. In-Flight Medical Emergencies: A Review. JAMA. 2018 Dec 25;320(24):2580-2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19842. PMID: 30575886.

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former US Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

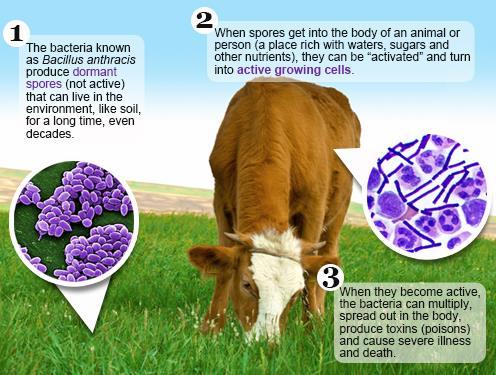

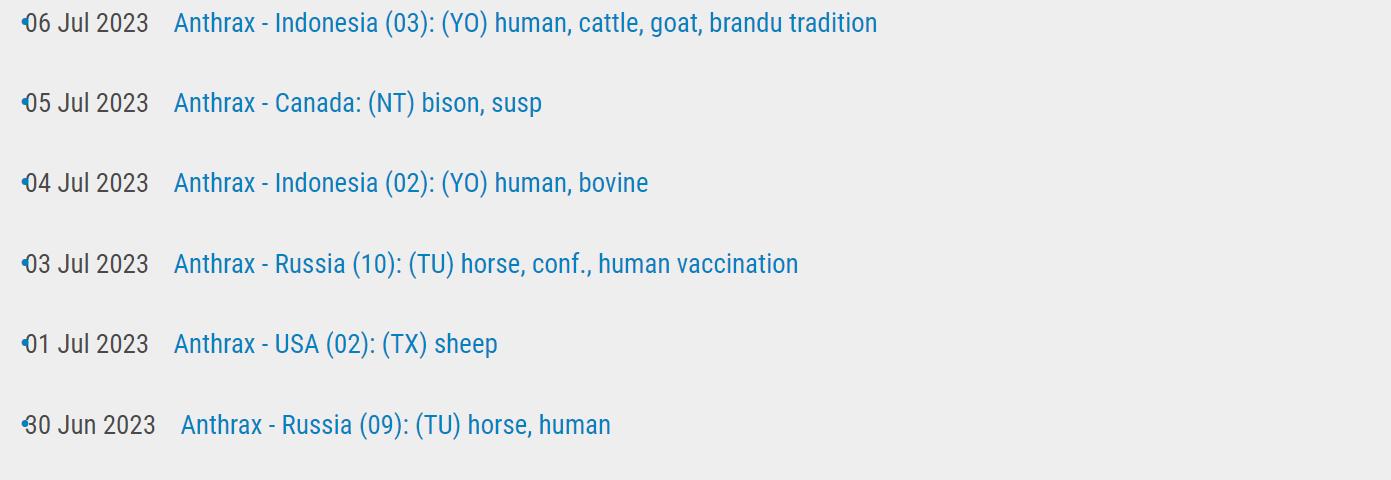

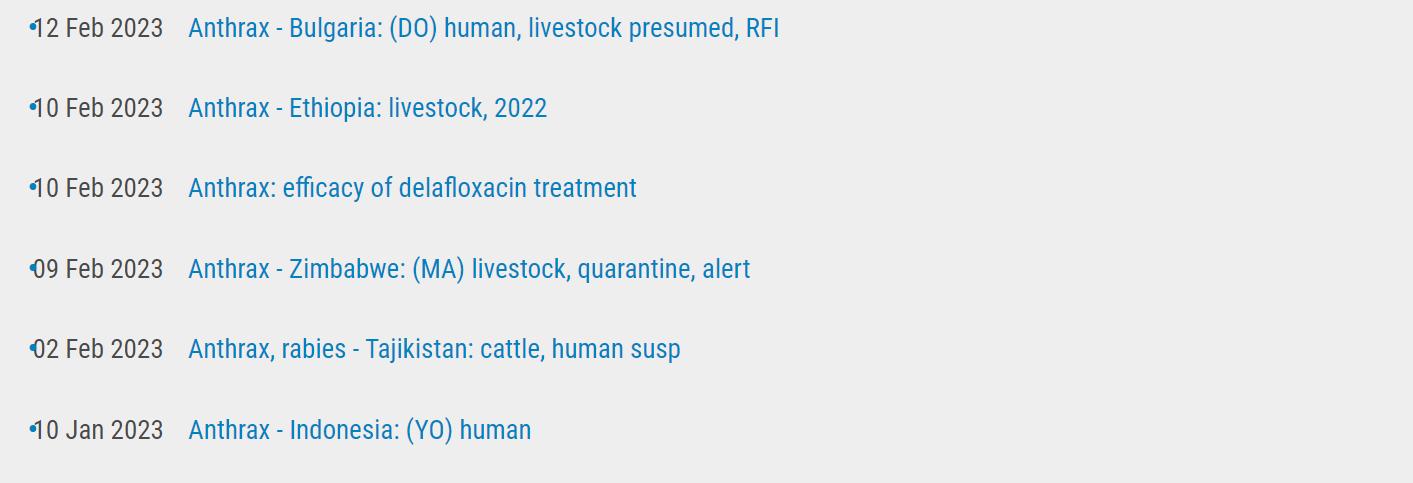

As I delved deeper and deeper into this issue’s book review on Jeanne Guillemin’s Anthrax: The Investigation of a Deadly Outbreak, I decided that a more appropriate place for many of her basic science points on Bacillus anthracis was this section.

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NR-Paramedic PGCert Infectious Diseases

It is worth noting that there have been no less than 18 anthrax cases and/or outbreaks reported by the ProMed global network in 2023 so far. These outbreaks are listed on page 13 of this newsletter.

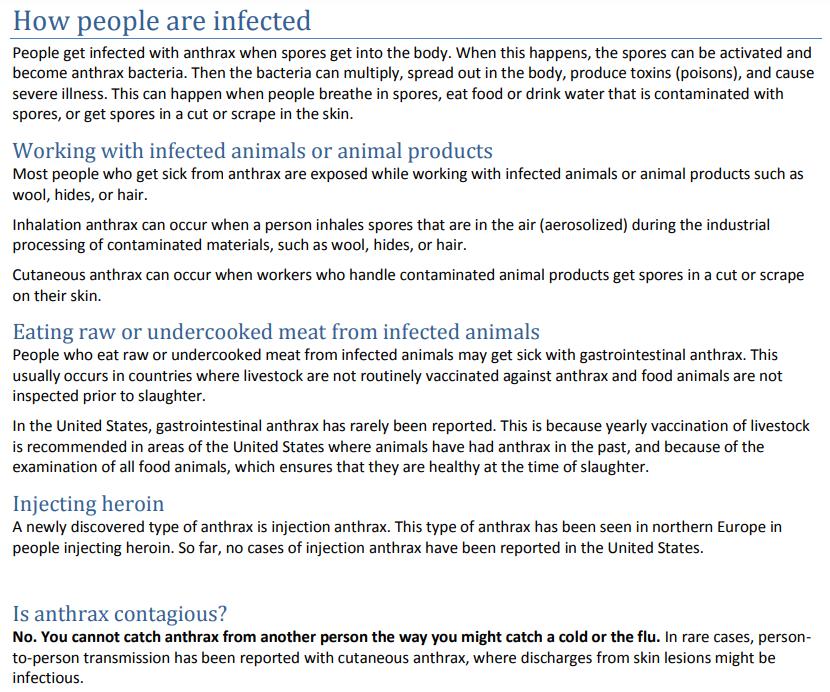

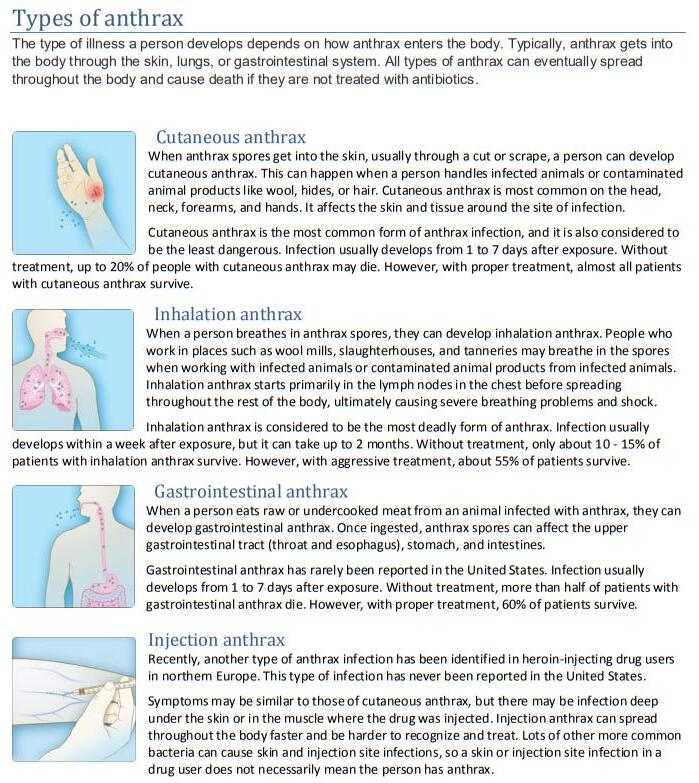

On to the basic science: anthrax is a disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, an encapsulated spore-forming gram-positive facultative anaerobic bacteria. It is a zoonosis (normally infecting ruminants) and is usually transmitted cutaneously, presenting with black and painful skin ulcers. Rarely, anthrax is acquired via ingestion, inhalation, or injection.

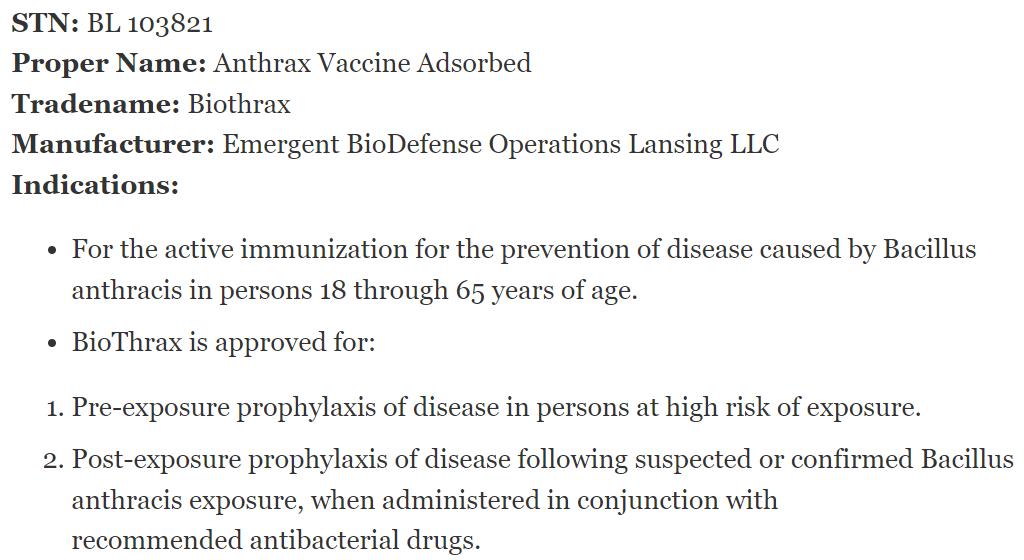

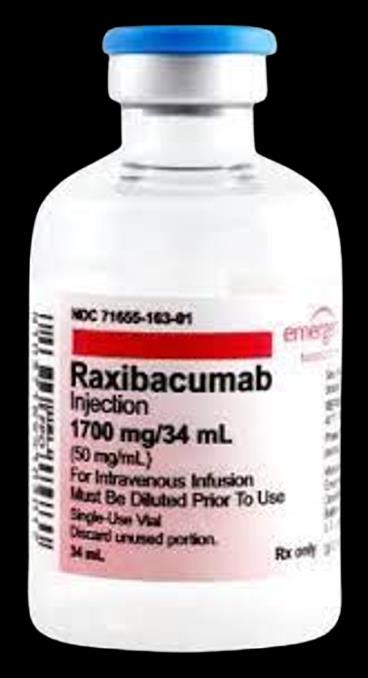

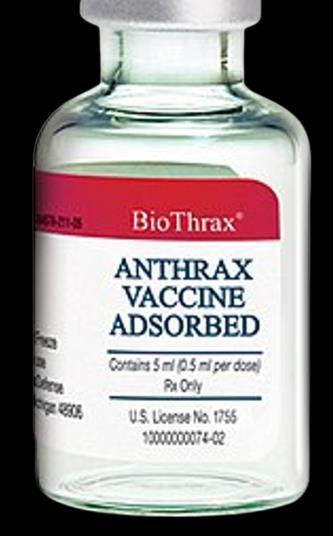

Pathology results from the release of three bacterial toxins: protective antigen, lethal factor, and edema factor. A vaccine exists (Biothrax®), and cases can be treated with ciprofloxacin and monoclonal antibodies (raxibacumab or obiltoxaximab).

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/anthrax/ photos.html

https://www.cdc.gov/ant hrax/basics/index.html

Anthrax lesions on the neck

Anthrax lesions on the neck

https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/basics/index.html

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

https://www.nature.com/articles/3880337

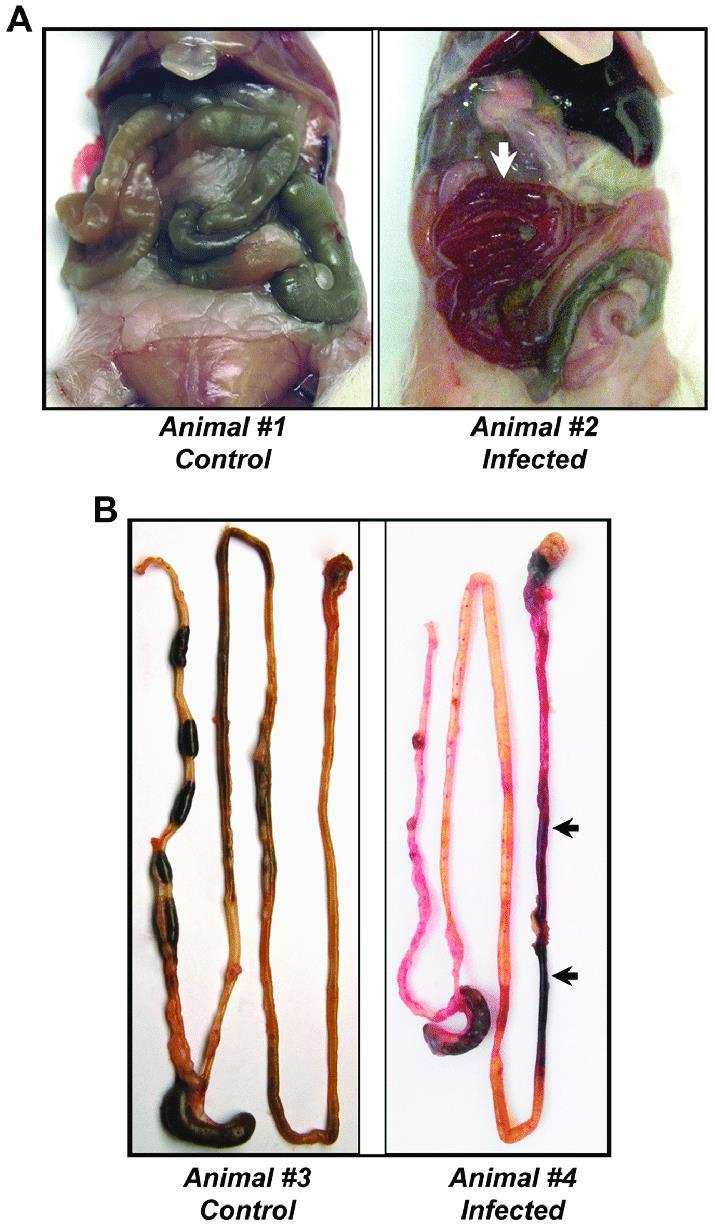

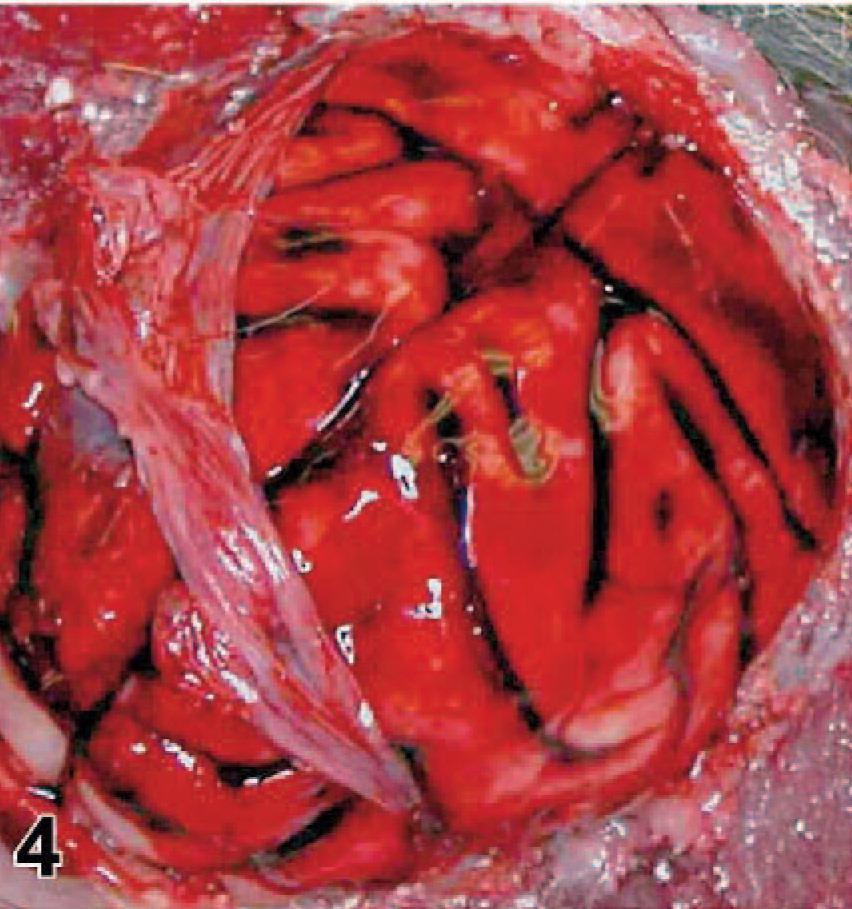

Gastrointestinal anthrax in a mouse model.

https://www.nature.com/articles/3880337

https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/biothrax

During a mass casualty event such as the Boston Marathon Bombing, even well-equipped medical responders will quickly run out of their disposable medical equipment. It is important the healthcare professionals know how to improvised the basic medical equipment needed during one of these events.

O’Kelly M.Psy DTN FRSM FAWM FRSPH

O’Kelly M.Psy DTN FRSM FAWM FRSPH

During the Boston incident, 281 people were injured. Three were immediate fatalities whilst 66% suffered lower extremity soft tissue injuries. 31 more could have died from exsanguination if treatment was not immediately provided. 26 of those casualties were given tourniquets and most of those tourniquets were improvised (Gates et al, 2017).

During the patient assessment, these injuries should be addresses at big C (catastrophic haemorrhage), little C (moderate bleeding) and at D (disability where we address fractures). When I was working on the ambulances in Seattle, we carried commercial bandages, tourniquets and slings to address these injuries. However, we only carried enough for one or two calls before we had to return to base (RTB) for resupplies. When working in remote, austere and resource-limited environments (or during a mass casualty) we don’t have the option to RTB for more supplies. As remote healthcare professionals, we need to be better than this and have the ability to quickly create tourniquets, bandages and slings in order to meet any major medical event.

Improvised Tourniquet

McCarty et al (2019) conducted a study comparing commercial tourniquet application and improvised tourniquets. They found that only 32% of non-medical responders were able to correctly apply an improvised tourniquet compared to 92% who use the CAT. This means that making an improvised device can be dangerous and could possibly cause more harm. It is imperative that healthcare providers practice this technique in order to be effective.

You can create an improvised tourniquet by cutting up a shirt, pants, sheet or other fabric into two-meter strips that are at least 10cm wide. When we teach this at the College, we make sure that the length is equal to their outstretched arms holding the cloth with both hands as far apart as possible. This will be close to two meters. Then, when they cut the cloth, they make sure that at no time is the width of the bandage narrower than the palm of your hand. Using this bandage, you can place it just below the shoulder or just below the groin. Find the halfway point in the bandage and place that on the casualty with two onemeter length ends. Start wrapping the bandage around the appendage making sure that you are keeping the bandage at least 10cm wide. You don’t want to bunch up the bandage. It must be kept wide to increase the surface area of the tourniquet. Then, find a windlass and tie it into a knot. Start twisting. Make sure that you don’t pinch the skin as you twist. Keep twisting until arterial bleeding stops. Give it another couple twists after that.

According to the McCarthy study, most applied tourniquets are not twisted tightly enough. Don’t make that mistake here. Make sure you have (or create) a proper tourniquet. Document the time on the casualty and continue with your assessments and treatments.

We discussed how to make improvised bandages in the paragraph above. You need a bandage in order to improvise a tourniquet. In a mass casualty event, you will need a lot more bandages than you will need tourniquets. There should be someone giving directions to non-medical personnel to make as many bandages as they can.

Once you have sorted the catastrophic haemorrhage and the minor bleeding with your improvised bandages, it is time to start creating splints and slings to treat all of the Disability injuries such as broken bones. You can create triangular bandages by cutting open tee shirts or finding bed sheets. Cut them into triangles about the height of your fingertips to your elbow. Or, you can use one of the commercial cravats that you have and use that as a template to cut around.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bandaging_techniques_for_use_in_first_aid._Lithog raph,_ca._Wellcome_L0044656.jpg

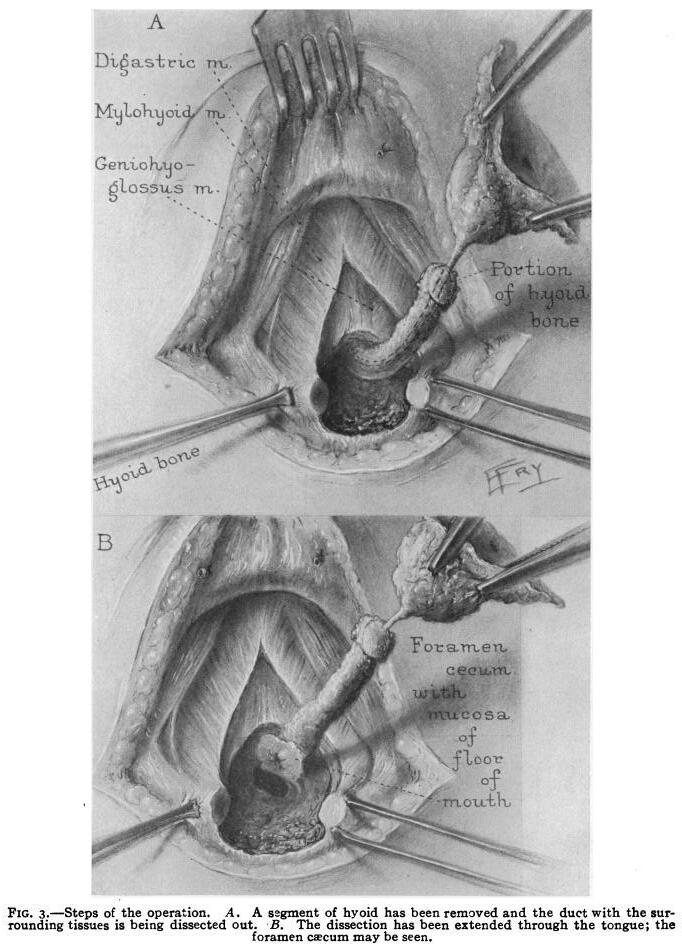

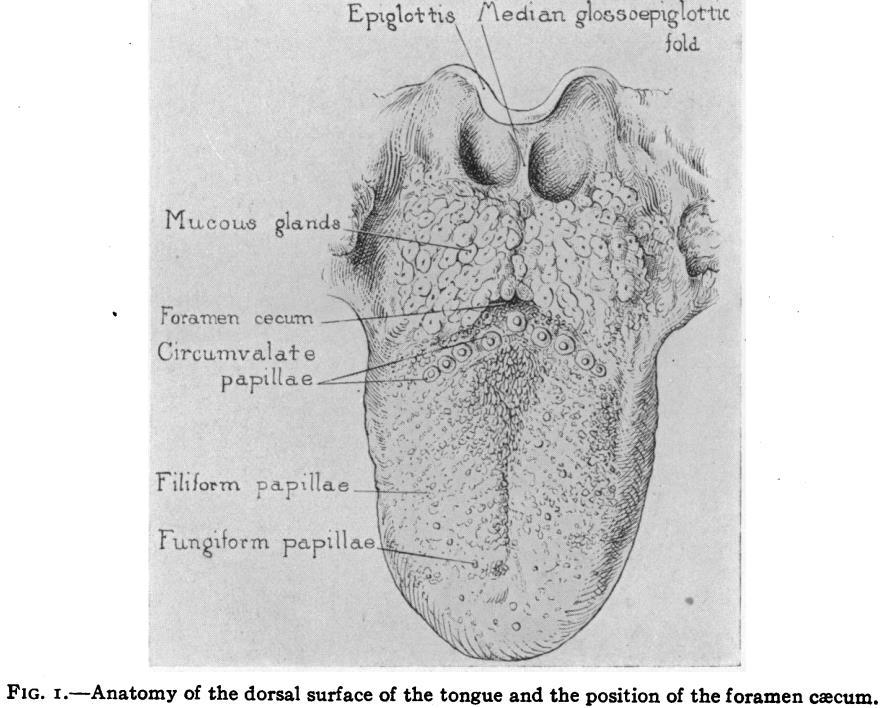

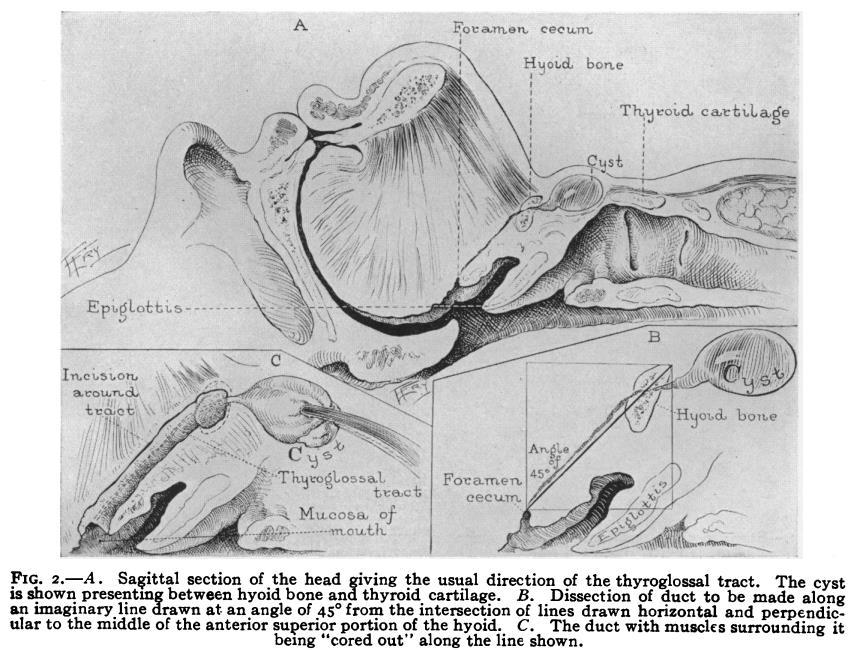

The "thyroglossal duct cyst" ("TGDC") is a classic example of a congenital abnormality that can be tracked in the knowledge of its embryologic development. As its name suggests, the cyst develops in the midline along a track from the base of the tongue down through the midpoint of the hyoid bone to the thyroid cartilage in the "migration" of the thyroid gland as the neck extends in fetal development.

Geelhoed

The anatomic position is pre-determined by the development of this endoderminduced (the foregut from the foramen cecum at the apex of the circumvallate papillae at the base of the tongue) mesoderm-derived thyroid gland.

1. Presenting symptoms, and physical findings: This young boy had the classic presentation of a non-tender midline neck mass that was present in the area between the thyroid cartilage and the submental midline. It might be mistaken for a lymph node but for its position, duration and one unique feature which distinguishes it immediately upon physical examination. When asked to protrude the tongue, the mass rises since it is tethered to the foramen cecum at the base of the tongue. This is the pathognomonic feature that confirms the diagnosis on this simple observation made on initial physical examination.

Rarely, the mass might become inflamed and in that instance exhibits the cardinal signs of inflammation including redness, tenderness, and might even become abscessed and drain to the exterior if any invasive procedure is done. This is a circumstance that might occur if there is a patent track to the base of the tongue and the oral cavity contaminates this to become a thyroid glossal duct abscess. The same feature of the rise in the mass given the protrusion of a tongue remains, however, one would not undertake the elective operation of its excision until the inflammation had subsided after incision and drainage done for management of any abscess.

At this "teaching point," I often use this TGDC as an example of my "cervical rule of sevens" for the differential diagnosis of any neck mass That is, if the mass is present for 7 days it is inflammatory; if it is present for 7 months it is neoplastic; if it is present for 7 years, it is congenital

Glenn

MD, AB, BS, MA, DTMH, MPH, MPhil, EdD, ScD, FACS, MAMSE

Glenn

MD, AB, BS, MA, DTMH, MPH, MPhil, EdD, ScD, FACS, MAMSE

The patient's age, presence or absence of tenderness, and the anatomic site are, of course, critically important distinctions, but this general rule of thumb in the patient’s history holds for most masses in the neck, clenched with the findings on physical examination.

Further "value added" information would be unlikely to come from imaging (sonography, scanning, or contrast x-ray) since all of these "shadow producing procedures" would merely confirm the presence of a mass, information already in hand from the faster, cheaper, and much more direct data obtained by the palpation of your dynamic physical examination!

If the suspicion of a non-tender, solid-texture mass is whether it might be a neoplasm, the only "value added" differential of consequence to the clinician--and, above all, to the patient--is whether this neoplastic mass is benign or malignant. In contrast to an imaging study at this point, which might most likely yield ambiguous further data, the only way to add value in this critical determination is to add magnification to the clinician's fingers, and that is done by cytology.

Fine needle aspiration would be the single determinative step beyond the physical findings on top of that history based in the cervical rule of sevens to determine the next step in diagnosis which would likely be done by excisional biopsy, which will give a definitive histologic diagnosis following extirpative therapy.

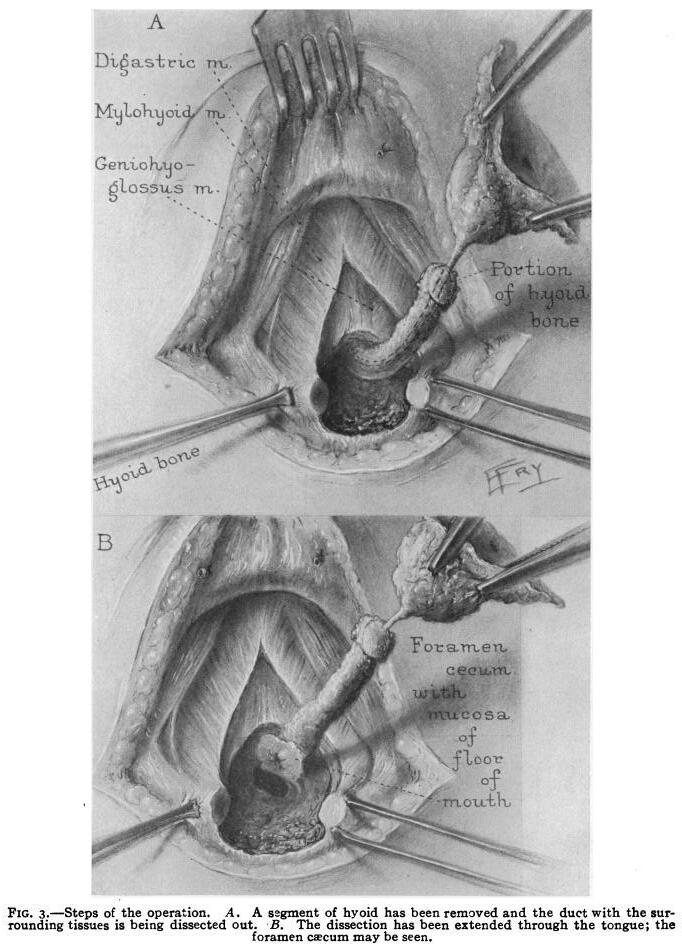

2. The surgical procedure was 25 minutes in duration, and the name of the procedure is the Sistrunk operation, which is distinguished by not simply the removal of the lump (the TGDC), but the track down which the thyroid anlage have migrated, so as to prevent recurrence. This operation involves the resection of the midpoint of the hyoid bone through which the track progresses, and, indeed, had induced the hyoid bone formation in embryology.

3. Ideally, the choice would be for general anesthesia with control of the airway in the patient in the pediatric age group in which this operation is most generally carried out in the developed world. A very short acting general anesthetic would be appropriate, but in the remote setting in which this was done, (in the Mission to Heal (M2H) mobile surgical unit at a mountaintop village in the Virunga "Mountains of the Moon" Uganda/Rwanda border) we lacked both anesthesiologist and endotracheal airway control, and therefore employed a short-acting period of amnesia with ketamine, and infiltration local anesthetic. We used 1% lidocaine with epinephrine for local operative site infiltration after one very brief low dose of intravenous ketamine which was adequate both for the operation and immediate recovery.

4. Airway was carefully maintained by cervical hyperextension and monitored by a senior medical student who was present to observe the operation with primary responsibility for the patient's airway with AMBU mask and oropharyngeal airway. The cervical hyperextension is maintained by a plastic liter IV saline bottle which is warmed in this tropical setting and covered in a sleeve of stockinette under the shoulders for a comfortable pillow when the patient is awake and for cervical hyperextension for airway protection when he is not.

We find one of these congenital abnormalities on nearly every mission and sometimes several at each site. It is easily recognized and readily treated but resection must be performed correctly, as simple excision as though it were the same lump as a lymph node or lipoma will result in recurrence when residual components of the track are left behind.

One of the reasons that we see so many TGDCs on M2H missions relates to several other highly prevalent conditions such as hernias, hydroceles, lipomas and burn scar contractures. The "burden of illness" in these remote settings relates to the distinction of "incidence" and "prevalence." The incidence of any given abnormality is how many of these diagnoses are recognized per unit of time, and the prevalence is how many are in the population at any given point in time. Since no one has been recognizing and treating these abnormalities, the cumulative incidence becomes greater prevalence, and therefore there are many readily fixable problems that would have been eliminated as they are "incident", become diagnosed, and are promptly repaired, (as an example, how many adult cleft lips or palates, or club feet are encountered in urban first-world settings?)

The incidence of these fixable problems that are subtracted from the prevalence in the developed world is in sharp contrast with a very large cumulative burden of illness in the developing world.

Dr Glenn Geelhoed received his BS and AB cum laude from Calvin College and MD cum laude from the University of Michigan He completed his surgical internship and residency through Harvard University at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital Medical Center To assist in developing further volunteer surgical services in underserved areas of the developing world, Glenn completed masters degrees in international affairs, epidemiology, health promotion and disease prevention, anthropology, and a philosophy degree in human sciences

He still works as a professor of surgery at George Washington University Medical Center in Washington D C and is a member of numerous medical, surgical, and international academic societies Glenn is an avid game hunter and runner He has completed more than 135 marathons across the globe He is also a widely published author accredited with several books and more than 500 published journal articles and chapters in books He has two sons and five grandchildren

CoROM Senior Faculty Dr John Quinn recently coauthored an article in Military Medicine entitled “Prehospital lessons from the war in Ukraine: damage control resuscitation and surgery experiences from point of injury to Role 2 ”

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NR-Paramedic PGCert Infectious Diseases

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NR-Paramedic PGCert Infectious Diseases

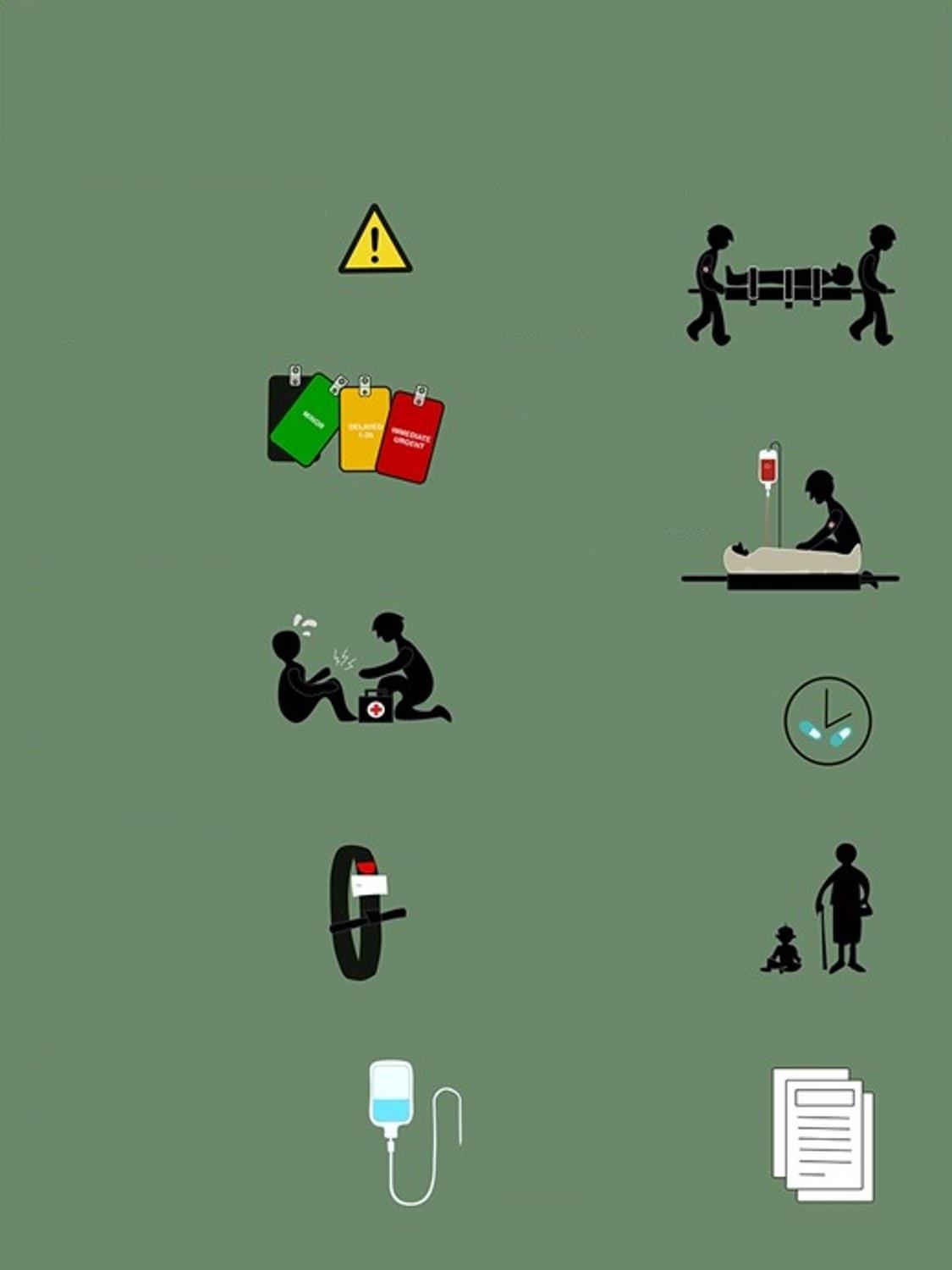

This article includes a ten-point infographic, reprinted on the following page. These lessons learned are enumerated below, with my commentary.

#1 The safety of rescuers and medical personnel is at risk due to multi-domain warfare & a disregard of International Humanitarian Law and the use of deadly weapons. This necessitates adjustments in PPE, contingency and communication planning, and prioritizing scene safety principles.

Editor’s commentary: This is the typical strategy of nations that have decided to engage in total war and go “all in.” Russia has – thus far – shown restraint with regards to CBRN weapons in Ukraine, though the same cannot be said of Russia’s Syrian allies. The idea that the will of a population can be broken by the indiscriminate killing of civilians flies in the face of numerous failed examples of this strategy in recent history – at least not in wars by proxy.

#2 In modern multi-domain battles and hybrid warfare, traditional triage approaches face challenges due to the lack of resources, training, and access to medical facilities. Adapting to these challenges is crucial to manage overwhelming situations and treat casualties with multiple injuries.

In order to prepare for conflicts such as the war in Ukraine, field training exercises should contain “triage conundrums” which go beyond the sorting of casualties into the classic Urgent, Priority, Routine, and Expectant categories. Civilians, host nation soldiers, international media, contractors, VIPs, and even working dogs can be included in a mass casualty exercise in which an evacuation has been requested. To maximize effect, aircraft (or ambulance) arrival times should be staggered so that not all casualties cannot be evacuated upon the arrival of the first vehicle.

#3 In high patient volume conflict zones like Ukraine, thorough primary and secondary assessments remain essential to identify and treat life-threatening injuries. These must occur in a timely fashion despite operational security challenges, light availability and the frequent need for sound discipline. Coping strategies and improved training for these circumstances are crucial for adequate patient care.

Conducting a thorough physical assessment in a tactical environment can be incredibly difficult, even for the most highly-trained field medicine practitioners. My guidance has always been to continuously reassess, and to not let one’s ego (or simple complacency) get in the way of asking a colleague to double-check for missed injuries.

J Quinn, S

J Quinn, S

Y

Y

#1 The safety of rescuers and medical personnel is at risk due to multi-domain warfare & a disregard of International Humanitarian Law and the use of deadly weapons. This necessitates adjustments in PPE, contingency and communication planning, and prioritizing scene safety principles.

#6 Transport immobilization is a crucial aspect of prehospital care, as effective immobilization helps stabilize patients’ hemodynamics, reduces nociceptive impulses, prevents secondary tissue and vascular damage, and minimizes the risk of fat embolism.

#2 In modern multi-domain battles and hybrid warfare, traditional triage approaches face challenges due to the lack of resources, training, and access to medical facilities. Adapting to these challenges is crucial to manage overwhelming situations and treat casualties with multiple injuries.

#3 In high patient volume conflict zones like Ukraine, thorough primary and secondary assessments remain essential to identify and treat life-threatening injuries. These must occur in a timely fashion despite operational security challenges, light availability and the frequent need for sound discipline. Coping strategies and improved training for these circumstances are crucial for adequate patient care.

#4 Ensuring proper tourniquet use in conflict zones requires quality control, procurement, training, and best practices. Improvements in prehospital care include phasing out substandard and outdated rubber alternatives, supplying CoTCCC-approved tourniquets, and implementing quality assurance measures for battlefield tourniquet use.

#5 Effective pain management in prehospital settings remains a challenge in Ukraine. Rescuers and providers lack reliable access to adequate pain management resources, such as fentanyl, ketamine, and morphine. Nalbuphine is the most frequently used in the field. If the military medical system cannot provide other analgesia in the field, due to potential interactions with morphine and fentanyl, it may be prudent to continue with nalbuphine throughout echelons of care.

#7 Ensuring proper patient warming at the point of injury and during transport is vital for patient comfort and stability. While thermal blankets can help maintain heat passively, active warming methods are essential in severe injuries and critical conditions – as is the use of fresh whole blood.

#8 The proper use of antibiotics is crucial for reducing morbidity and mortality in battlefield injuries. However, limited access to antimicrobial guidance, biogram data, and clinical resources can make it challenging to administer appropriate antibiotic therapy for trauma patients in the conflict zone.

#9 As the conflict plays out in a civilian landscape, medical professionals must be prepared to care for a diverse range of patients, beyond the traditional focus on young, healthy males in wars. Various age groups present unique challenges and require different treatment approaches.

#10 Significant administrative and operational challenges for healthcare professionals, volunteers, NGOs, and public sectors include working within one’s scope of practice, accountability, professional roles, documentation, security, and navigating checkpoints.

J Quinn, S Panasenko, Y Leshchenko, K Gumeniuk, A Onderková, D Stewart, AJ Gimpelson, M Buriachyk, M Martinez, TA Parnell, L Brain, L Sciulli, JB Holcomb

J Quinn, S Panasenko, Y Leshchenko, K Gumeniuk, A Onderková, D Stewart, AJ Gimpelson, M Buriachyk, M Martinez, TA Parnell, L Brain, L Sciulli, JB Holcomb

#4 Ensuring proper tourniquet use in conflict zones requires quality control, procurement, training, and best practices. Improvements in prehospital care include phasing out substandard and outdated rubber alternatives, supplying CoTCCC-approved tourniquets, and implementing quality assurance measures for battlefield tourniquet use.

The one trauma skill that is currently being trained above all others across every organization I have worked with in recent years is tourniquet use. That said, there is never a shortage of tourniquets of questionable utility, despite the promulgation of the CoTCCC-approved tourniquet list. Besides the proliferation of such “new and improved” tourniquets into a market that is already maximally saturated with highquality tourniquets, the online marketplace can easily dupe the unsuspecting purchaser of tourniquets into buying cheaper knockoff products that are not intended for clinical use.

#5 Effective pain management in prehospital settings remains a challenge in Ukraine. Rescuers and providers lack reliable access to adequate pain management resources, such as fentanyl, ketamine, and morphine. Nalbuphine is the most frequently used in the field. If the military medical system cannot provide other analgesia in the field, due to potential interactions with morphine and fentanyl, it may be prudent to continue with nalbuphine throughout echelons of care.

Controlling pain on the battlefield is an ongoing challenge that is as old as warfare. Believed by some to be a “nice to have” capability, pain control is in fact critical to casualty survival, in at least three aspects: 1) increased success rate for painful lifesaving procedures such as the cricothyroidotomy, 2) preservation of immune system function, and 3) marked reduction of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ketamine is the drug-of-choice for burns and has emerged as a mainstay analgesic drug for neuropathic pain, as well providing anesthesia in cases of grievous soft tissue injuries and surgical procedures to include wound debridement.

#6 Transport immobilization is a crucial aspect of prehospital care, as effective immobilization helps stabilize patients’ hemodynamics, reduces nociceptive impulses, prevents secondary tissue and vascular damage, and minimizes the risk of fat embolism.

This is in line with the way the MARCH trauma assessment/treatment algorithm has classically been taught, with the “H” signifying “head injury, hypothermia, and casualty handling.”

Damage Control Resuscitation and Surgery Experiences from Point of Injury to Role 2

J Quinn, S

Y Leshchenko, K

J Quinn, S

Y Leshchenko, K

#7 Ensuring proper patient warming at the point of injury and during transport is vital for patient comfort and stability. While thermal blankets can help maintain heat passively, active warming methods are essential in severe injuries and critical conditions – as is the use of fresh whole blood.

Aggressive hypothermia management and the utilization of blood products (fresh whole blood and/or lyophilized plasma) in the field are core capabilities taught across many CoROM courses.

#8 The proper use of antibiotics is crucial for reducing morbidity and mortality in battlefield injuries. However, limited access to antimicrobial guidance, biogram data, and clinical resources can make it challenging to administer appropriate antibiotic therapy for trauma patients in the conflict zone.

Early delivery of broad-spectrum antibiotics for massive penetrating trauma is a mainstay of both TCCC and CoROM training. CoROM follows the TCCC empiric war wound guidance, which recommends oral moxifloxacin or parenteral ertapenem. In addition, irrigation and debridement of such wounds is paramount and should be taught to all mid-to-high level field practitioners.

#9 As the conflict plays out in a civilian landscape, medical professionals must be prepared to care for a diverse range of patients, beyond the traditional focus on young, healthy males in wars. Various age groups present unique challenges and require different treatment approaches.

The incorporation of female casualties as well as geriatric, pediatric and obstetric cases should be effected in field trauma training exercises. An acute coronary syndrome, sudden cardiac arrest, snakebite, or severe infectious disease case can liven things up a bit as well. When I have inflicted such training amplifiers upon my students the learning curve tends to steepen quite a bit. At a capstone field training event earlier this year in Rwanda, one of the students said, “Wow Jason, you threw the whole book of medicine at us on that one.” To which the best response perhaps is simply to say, “You’re not going to rise to the occasion in a real crisis, you’re going to default to your baseline level of training.”

#10 Significant administrative and operational challenges for healthcare professionals, volunteers, NGOs, and public sectors include working within one’s scope of practice, accountability, professional roles, documentation, security, and navigating checkpoints.

“Plans are nothing, but planning is everything” (to paraphrase, “Everyone has a great plan until they get punched in the face).” Communication, communication, communication. Train as you fight.

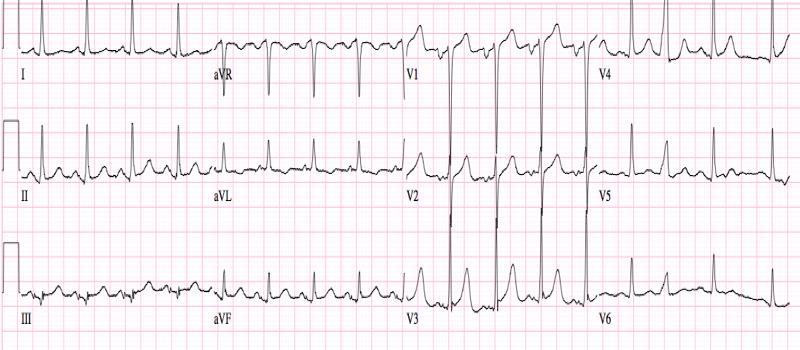

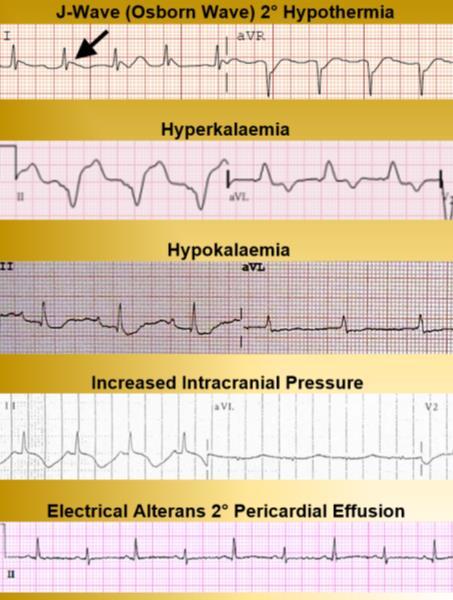

This 12-lead reveals which of the following conditions?

A. hypokalemia

B. right axis deviation

C. left atrial hypertrophy

D. first-degree atrioventricular block

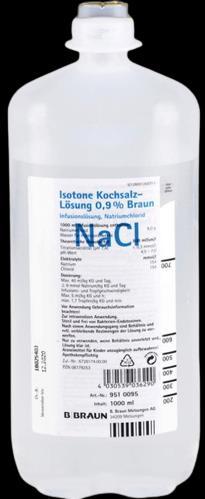

During a demining mission in a remote region of Laos, you are asked to evaluate the local village leader who presents with esophageal varices secondary to liver cirrhosis. You decide to initiate an octreotide infusion to mitigate hemorrhaging during ground ambulance transport to a hospital in Vientiane. The infusion will run at 50 mcg/hour from a stock of 1.5 mg octreotide mixed in one liter of normal saline. Using a 60 drop/mL giving set, you should deliver how many drops per minute?

Octreotide 1.5 mg 9 September 2023

As part of a crew filming a documentary in the Australian outback, you assess an 42 year-old male complaining of bilateral leg weakness x2 days. In addition, he exhibits loss of patellar reflexes and reduction of sensorium in both legs. He suffered a bout of gastroenteritis one month ago, and the entire film crew has been plagued by mosquito and tick bites since arriving on the set two months ago. This patient is most likely afflicted with which of the following conditions?

A. West Nile virus

B. tick bite paralysis

C. myasthenia gravis

D. Guillain-Barré syndrome

Answers will appear in the Winter 2023

Compass

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

A Elevated ST segments produced during pericardiocentesis

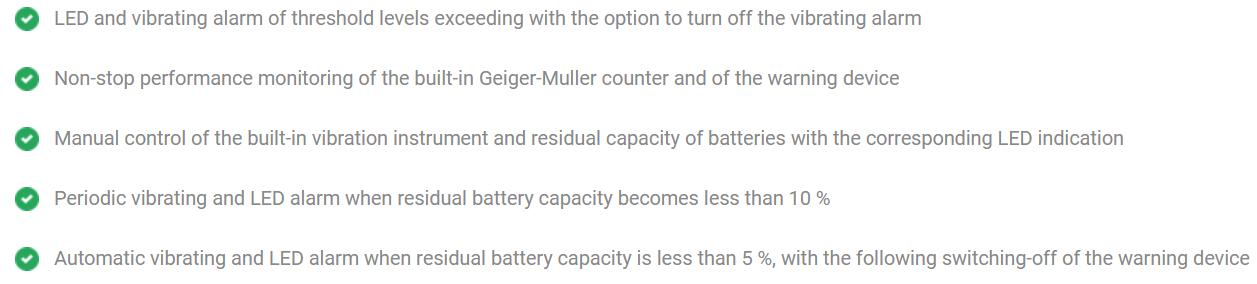

available at https://ecotestgroup.com/products/agent-r/

A wrist-type warning device in a shock-resistant body with a high ingress protection rating IP67. aGent-R is designed for detection and evaluation of gamma radiation using four-level threshold alarm system.

This week, Aebhric talks with Dr. Slaven Bajic, who teaches our Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound course. He is from Slovenia, where he runs the A&E department at his local hospital.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/28fno5yQqrFH7g0llcrtXW

Matt served seven years in various combat roles as a soldier and officer in the Australian Army before becoming a paramedic. With over 15 years as a paramedic across multiple ambulance services, Matt is currently a Special Operations/Intensive Care (ICU) Paramedic. Matt was part of the team that established the first full-time Tactical Paramedic Team in Australia and was the first-ever dedicated Tactical Medicine Training Officer in the country.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/50mHQuHRxiyw2d2ZcCSu3S

TWiP solves the case of the Hiker from Queens who Denies Bug Bites, and reveal two different malaria experimental vaccines that target different parts of the parasite life cycle.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/0MafT2QWzIVWcZyvusyT9X

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xXReoUoCTc8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rhgwIhB58PA

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Brandt MD, et al.

2023 June 23;23(2):44-48.

doi: 10.55460/WYEJ-1M3J.

Background: Recent data published by the Special Operations community suggest the Lethal Triad of Trauma should be changed to the Lethal Diamond, to include coagulopathy, acidosis, hypothermia, and hypocalcemia. The purpose of this study is to determine the prevalence of trauma-induced hypocalcemia in level I and II trauma patients. Methods: This is a retrospective cohort study conducted at a level I trauma center and Special Operations Combat Medic (SOCM) training site. Adult patients were identified via trauma services registry from September 2021 to April 2022. Patients who received blood products prior to emergency department (ED) arrival were excluded from the study. Ionized calcium levels were utilized in this study. Results: Of the 408 patients screened, 370 were included in the final analysis of this cohort. Hypocalcemia was noted in 189 (51%) patients, with severe hypocalcemia identified in two (<1%) patients. Thirty-two (11.2%) patients had elevated international normalized ratio (INR), 34 (23%) patients had pH <7.36, 21 (8%) patients had elevated lactic acid, and 9 (2.5%) patients had a temperature of <35°C. Conclusion: Hypocalcemia was prevalent in half of the trauma patients in this cohort. The administration of a calcium supplement empirically in trauma patients from the prehospital environment and prior to blood transfusion is not recommended until further data prove it beneficial.

StatPearls

Lofgran T, Warrington SJ. 2023 July 3. PMID: 32491386.

Millipedes are arthropods from the class Diplopoda that consists of more than 12,000 species. Many of the species are brown or black but can also vary in color, including orange and red. They are detrivores meaning that they feed primarily off of decaying plant matter. Size is variable and ranges from 2 mm to greater than 160 mm, and their body shape can be flattened or cylindrical. Their distribution extends to all continents except Antarctica with a preference for burrowing in dark areas of warm, humid climates such as the tropics. They are easily confused with their distant relative to the centipede but can typically be distinguished by the following criteria. Millipedes have two pairs of legs per body segment compared to centipedes, which have one, they are slower moving than centipedes, and they lack forcipules or fangs like centipedes and are unable to inject venom. Millipedes instead employ defensive mechanisms by curling up in a ball and secreting irritating chemicals from micropores along their sides to deter predators.

Emergency Medicine Australasia

Ogilvie T, et al.

2023 Feb;35(1):18-24.

doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.14036.

Objectives: Wave forced impacts are known to result in cervical spine injuries (CSI) and approximately 20% of drownings in Australia occur at the beach. The most common mechanism of injury in studies examining the frequency of CSI in drowning patients is shallow water diving. The aim of the present study was to determine what proportion of CSIs occurring in bodies of water experienced a concomitant drowning injury in a location where wave forced impacts are likely to be an additional risk factor.

Results: Ninety-one of 574 (15.9%) CSIs occurred in a body of water with risk of drowning. However, only 4 (4.3%) had a simultaneous drowning injury, representing 0.8% (4/483) of drowning presentations. Ten (10.9%) patients reported loss of consciousness, including the four with drowning. The principal mechanism of CSI was a wave forced impact (71/91, 78%). Most injuries occurred at the beach (79/91, 86.8%). Delayed presentation was common (28/91, 31%). A history of axial loading was 100% sensitive when indicating imaging.

Conclusions: The combination of CSI and drowning is uncommon. Cervical spine precautions are only required in drowning patients with signs or a history, or at high risk of, axial loading of the spine. This paper supports the move away from routine cervical spine precautions even in a high-risk population.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine Thompson P, et al.

2023 June 23;23(2):9-12.

doi: 10.55460/ZU1D-3DL9.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Tension pneumothorax (TPX) is the third most common cause of preventable death in trauma. Needle decompression at the fifth intercostal space at anterior axillary line (5th ICS AAL) is recommended by Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) with an 83-mm needle catheter unit (NCU). We sought to determine the risk of cardiac injury at this site.

Methods: Institutional data sets from two trauma centers were queried for 200 patients with CT chest. Inclusion criteria include body mass index of =30 and age 18-40 years. Measurements were taken at 2nd ICS mid clavicular line (MCL), 5th ICS AAL and distance from the skin to pericardium at 5th ICS AAL…

Results: The median age was 27 years with median BMI of 23.8 kg/m2. The cohort was 69.5% male. Mean chest wall thickness at 2nd ICS MCL was 38-mm (interquartile range (IQR) 32-45). At 5th ICS AAL, the median chest wall thickness was 30-mm (IQR 21-40) and the distance from skin to pericardium was 66-mm (IQR 54-79).

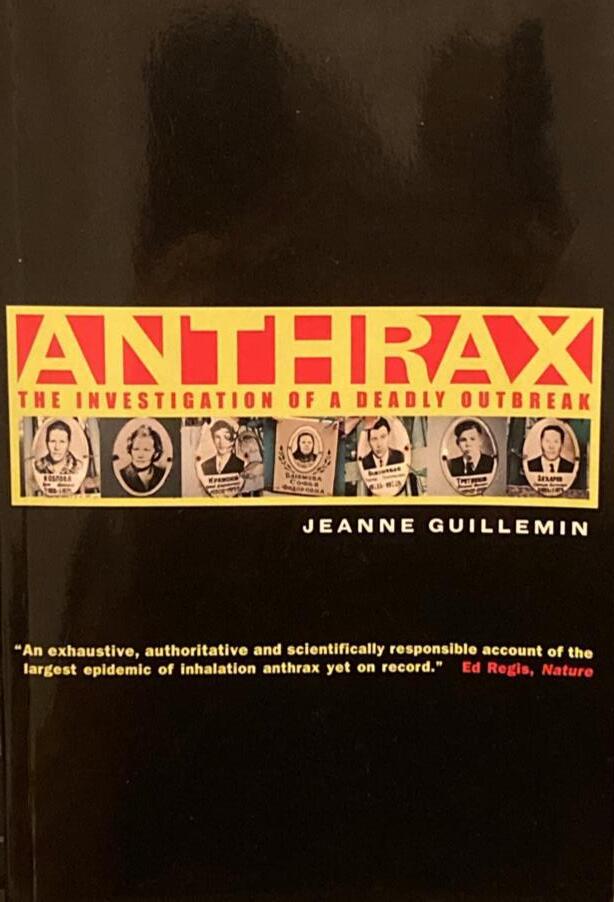

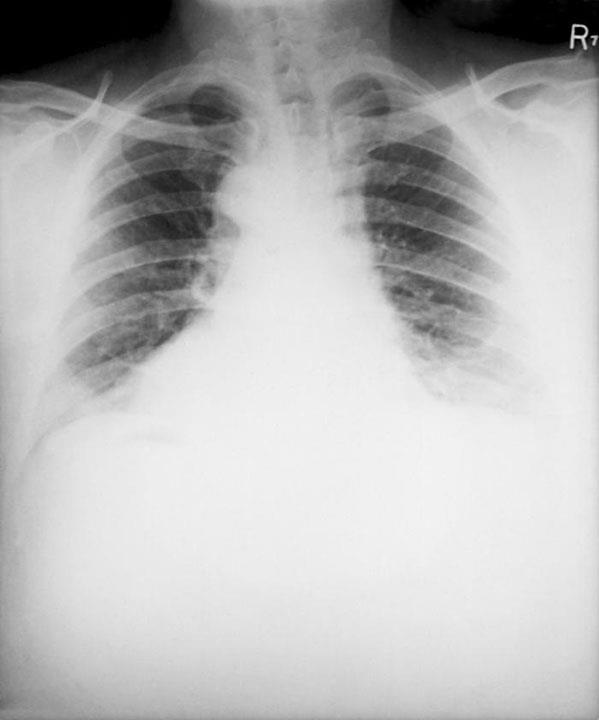

In the spring of 1979 the Soviet Union copped to an outbreak of anthrax in the city of Sverdlovsk. With a final death toll of at least 64, the Soviets claimed that that the outbreak was caused by the gastrointestinaltransmitted form of anthrax, and that tainted meat sold on the black market was to blame.

Both the suddenness of the outbreak and the rumors that had escaped across the Iron Curtain led many to suspect that the anthrax may have been spread via airborne spores, a rare phenomenon normally confined to those in very close proximity to infected animal fur (hence the term “wool-sorters disease”). An outbreak of airborne Bacillus anthracis claiming the lives of 64 people not otherwise involved with livestock would be a damning piece of evidence that the 1979 Soviet government was in violation of the 1975 Biological Weapons Convention.*

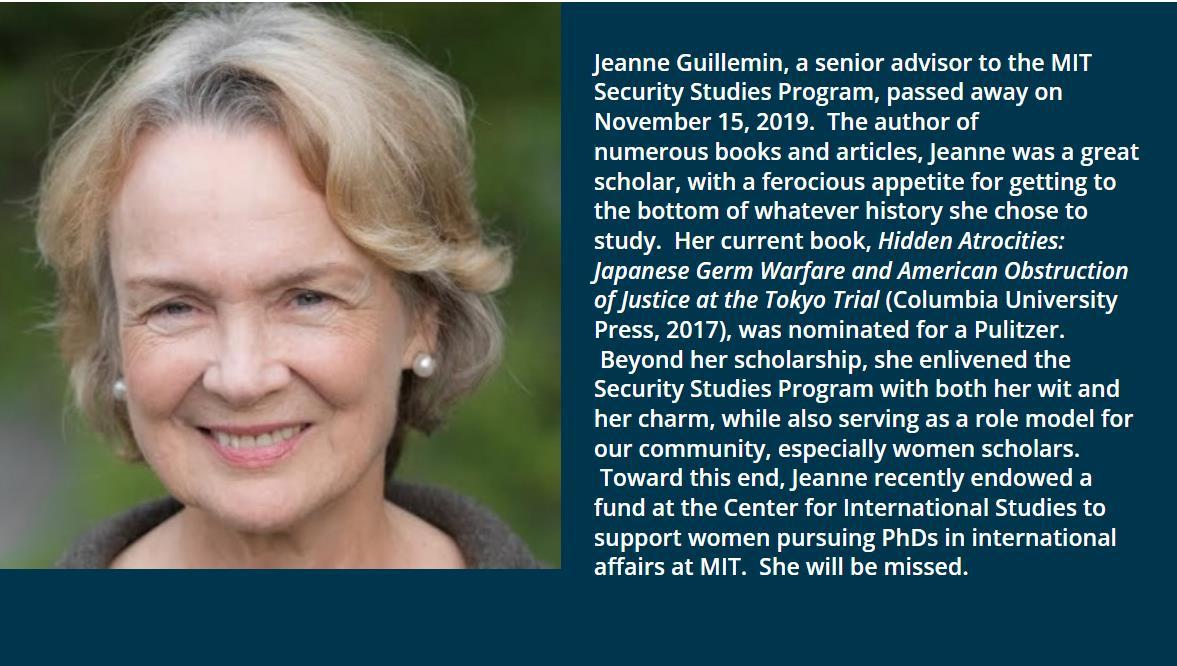

Sociologist and bioweapons expert Jeanne Guillemin was unconvinced that Moscow was being entirely truthful about the origin of the outbreak. She and a team of scientists visited Sverdlovsk in 1992 to discover the true origin of the bacterial zoonosis.

With a brilliant flair for history, Guillemin writes, “Anthrax is as old as pastoralism and the origins of civilization. It might be the Sixth Plague, the sooty “morain,” in the Book of Exodus that kills livestock and affects people with black spots ”

She goes on to quote the following passage from Homer’s Iliad, referring to Apollo’s “burning winds of plague”:

Pack animals were his targets first, and dogs but soldiers, too, soon felt transfixing pain from His hard shots, and pyres burned night and day

“A beautiful book It offers vivid insights into how scientists actually work – the ceaseless questioning from every conceivable angle whose goal is to eliminate doubt ”

- David Warsh, Boston GlobeJeanne Harley Guillemin

(March 6, 1943 - November 15, 2019) was an American medical anthropologist and author, who for 25 years taught at Boston College as a professor of Sociology and for over ten years was a senior fellow in the Security Studies Program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She was an authority on biological weapons and published four books on the topic.

*Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxic Weapons and on their Destruction.

Virgil’s Georgics is also quoted: For neither might the hides be used, nor could one cleanse the flesh by water or master it by fire. They could not even sheer the fleeces, eaten up with sores and filth, nor touch the rotten web. Nay, if any man donned the loathsome garb, feverish blisters and foul sweat would run along his fetid limbs, and not long had he to wait ere the accursed fire was feeding on his stricken limbs.

“In humans, and anthrax infection can begin in one of three ways. Infection through the skin (cutaneous anthrax) is what Virgil described and is the most common and obvious form. It begins with a tiny pimple. In a few hours this eruption becomes a reddish-brown irritation and swelling that turns into an ulcer, the “feverish blister” that splits the skin. The black scablike crust that the lesion develops gives the disease its name, anthracis, the Latin transliteration of the Greek name for coal. In Russian, anthrax is also called “Siberian ulcer” (Siberskaya yazva) because of the prevalence of the disease in that region.”

“The terms gastrointestinal and inhalation, as noted, refer to the portal of entry, how the pathogen entered the body, not necessarily to specific clinical manifestations. According to the few published reports of cases, fatal gastrointestinal anthrax and inhalation anthrax are characterized by similar initial symptoms. At first the patient experiences the aches, chills, mild fever, and nausea characteristic of influenza. In many cases, there is a brief respite from the symptoms, a “false recovery.” Then as the infection progresses, there may be high fever, severe pain in either the abdomen or chest or both, congested breathing, dizziness, bloody vomiting, and diarrhea.”

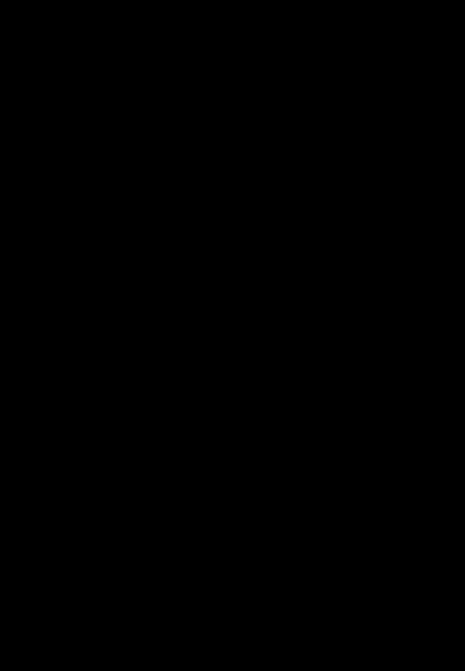

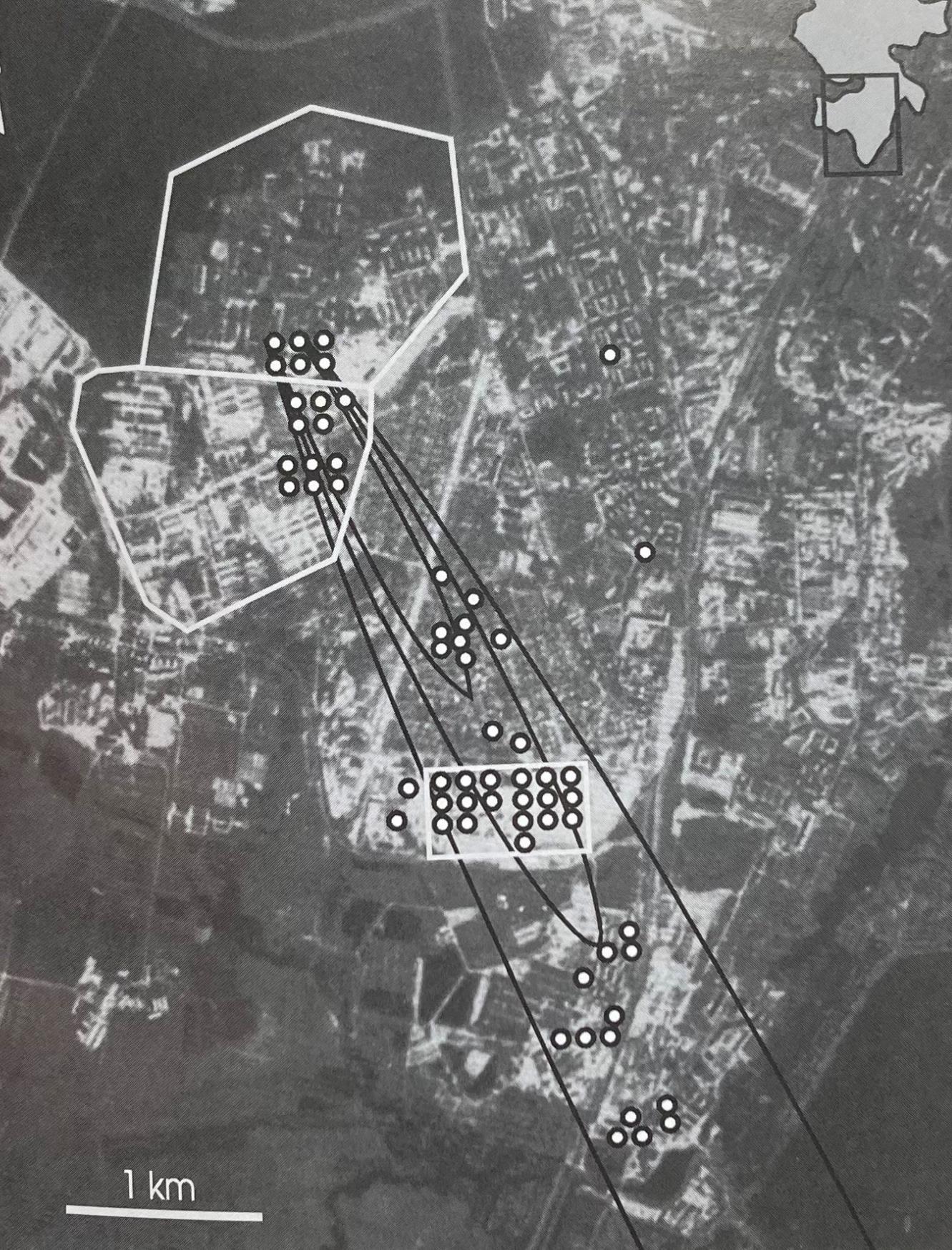

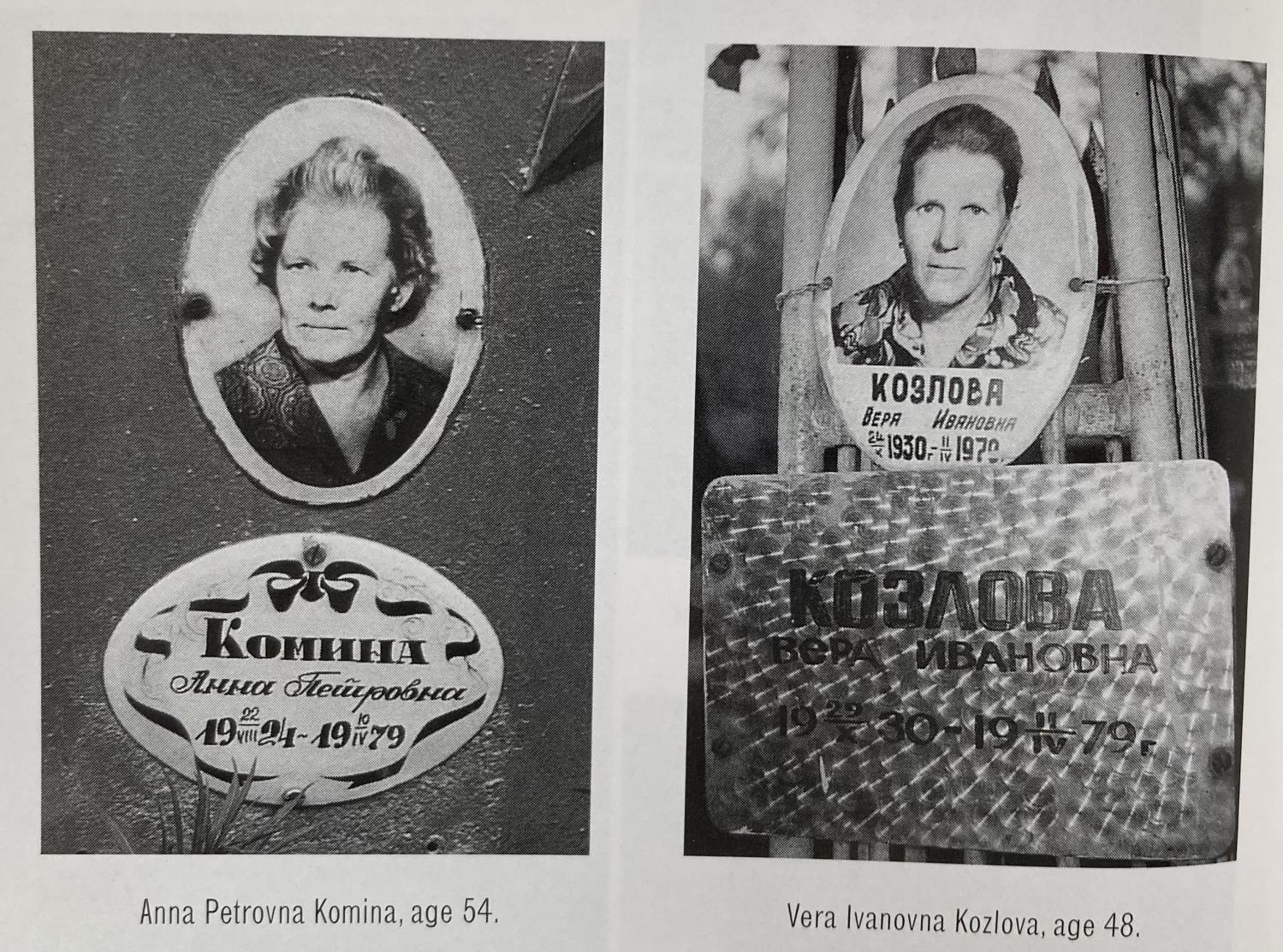

The Soviet city of Sverdlovsk – now renamed Yekaterinburg, according to its original pre-Bolshevik moniker – was ultimately judged by the investigational team to have been the site of an airborne anthrax leak from a bioweapons facility. On the following page is an aerial photograph of the city depicting “daytime locations of sixty-two anthrax victims in Chkalovsky rayon on Monday, April 2, 1979” in relation to Compound 19, the putative source of the anthrax leak.

All in all, Anthrax was an excellent read, encompassing quality basic infectious disease science and epidemiology, many aspects of biowarfare, Russian culture, and the dynamics of a team under stress attempting to accomplish a mission in a faraway land. The Soviet government’s coverup of this incident in 1979 set the playbook for the obfuscation it applied only seven years later to the explosion of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant’s RBMK Reactor 4.

http://ssp.mit.edu/news/2019/remembering-jeanne-guillemin

Daytime locations of sixty-two anthrax victims in Chkalovsky rayon on Monday, April 2, 1979. The insert at upper right shows Chkalovsky’s location in Sverdlovsk. Four outliers, in addition to the two that fall to the right of the plume here, lie outside this map’s boundaries, in the north and west of Sverdlovsk. The irregular areas outlined in white indicate the perimeters of Compound 19, from the emission emanated, and, to its south, Compound 32. The rectangle outlined in white indicates the location of and number of victims at the ceramics factory. The elliptical shapes (isopleths) indicate areas of decreasing concentration of dose, moving outward from the source.

-Anthrax

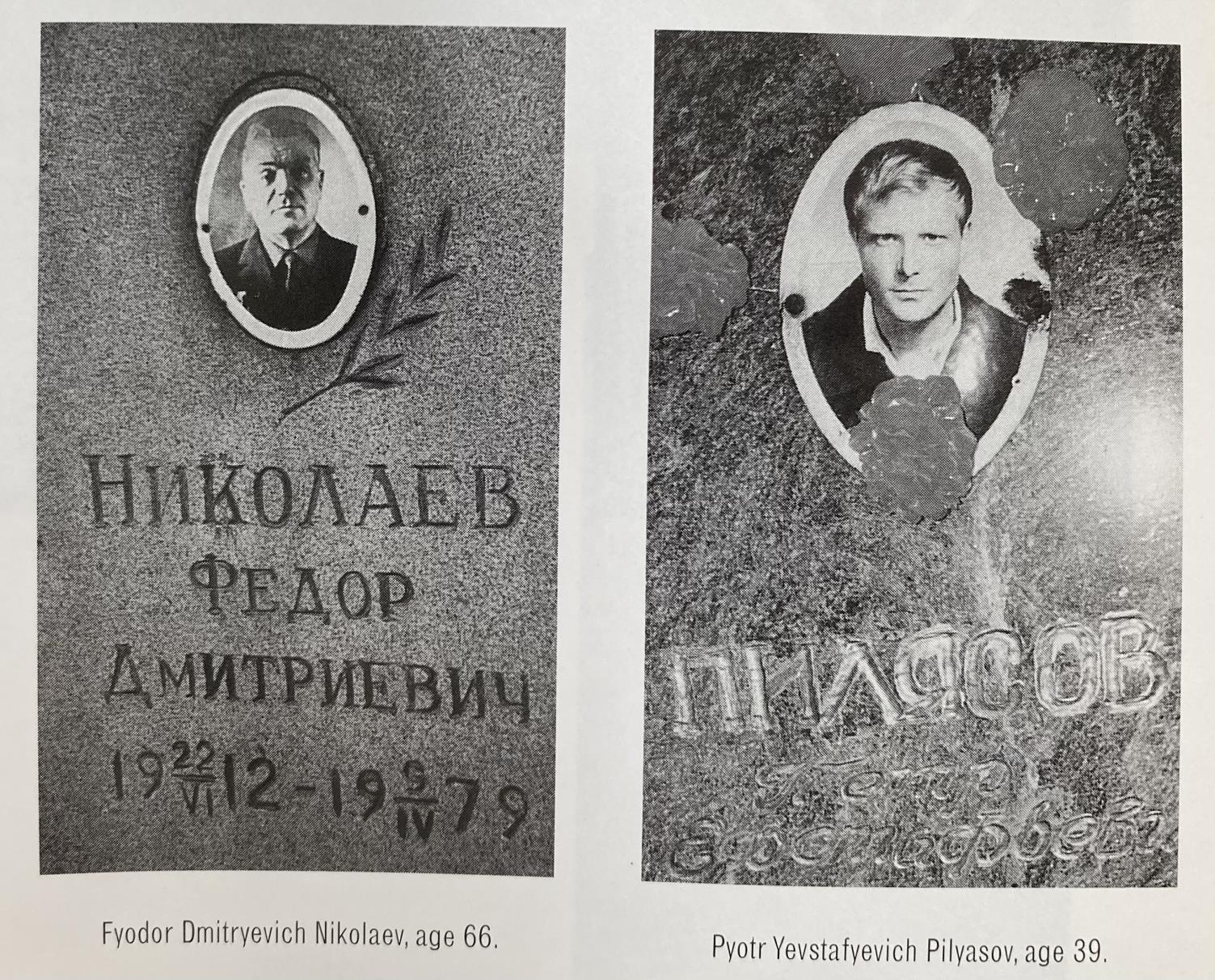

Memorials to victims of the 1979 anthrax outbreak

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-forprofit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is a Higher Education Institution registered with the Malta Further and Higher Education Authority. License No. 2018-022.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionals working in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources.

CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

MFSLR Dates TBD

TTEMS Dates TBD

NORTH CAROLINA

SOMSA Conference 13-18 May 2024

Tactical Medicine Review (O’Kelly)

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

Master of Science in Austere Critical Care

Master of Global Health Leadership and Practice

Doctor of Health Studies

Courses

Diploma Remote Paramedic

Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Diploma in Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitude

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Ghana National Ambulance Service

ACC

AEC

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

Acute Critical Care

Austere Emergency Care

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

AHA American Heart Association

APUS Austere and Prehospital Ultrasound

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

MFSLR Mastering Fundamentals of Skin Laceration Repair

PALS

Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (in-classroom)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition

Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.edu.mt

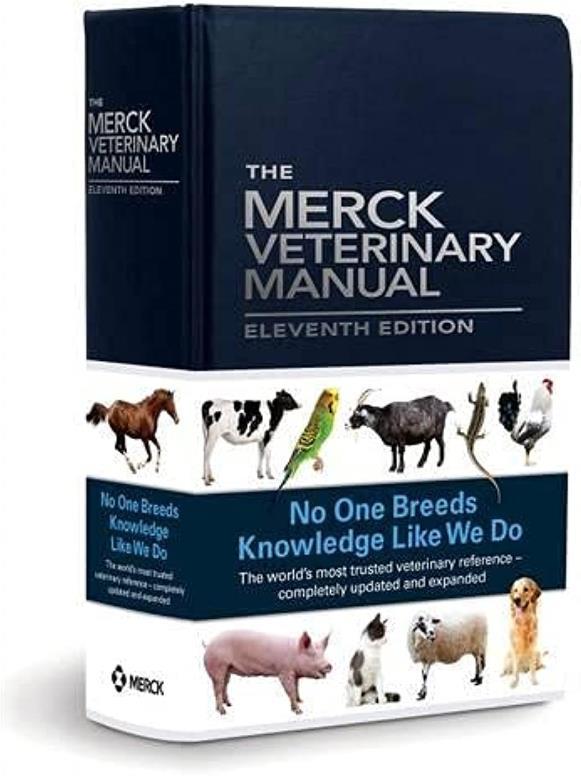

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

OB/Gyn

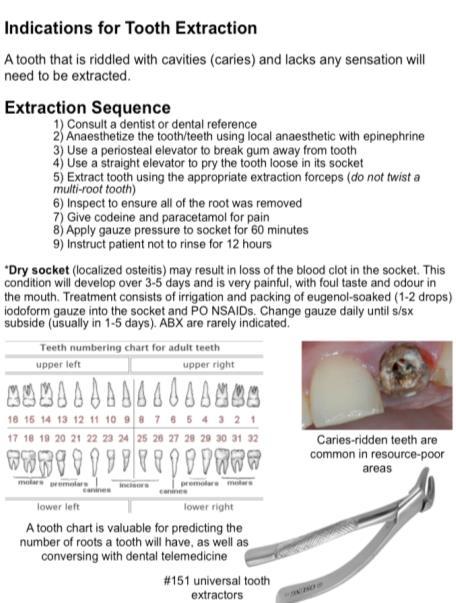

Dentistry

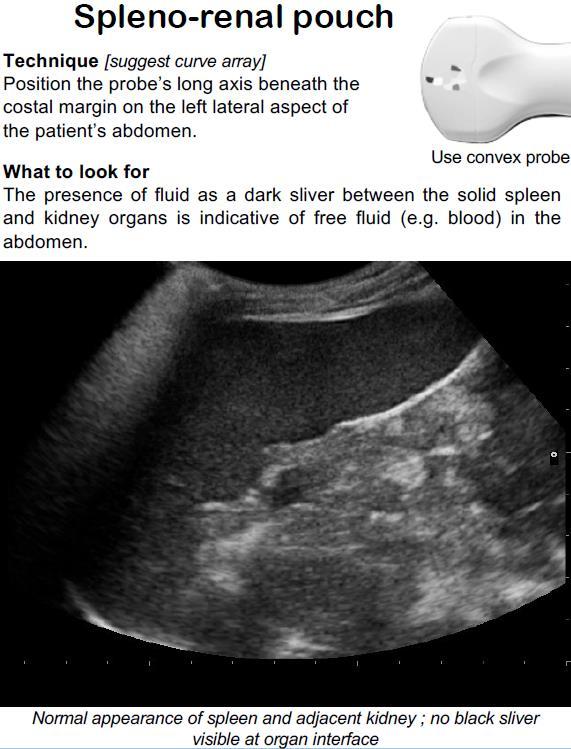

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

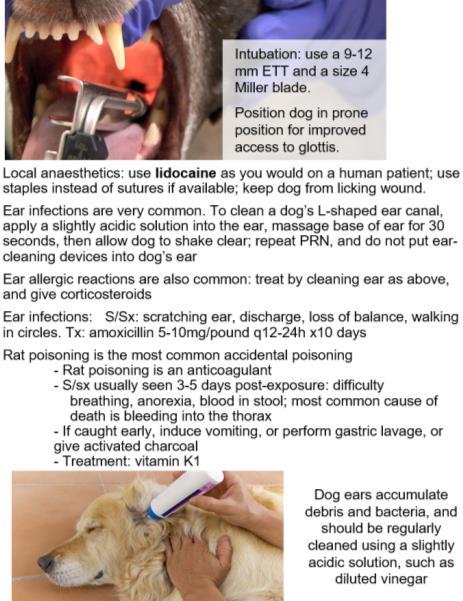

Canine medicine

…and much more!