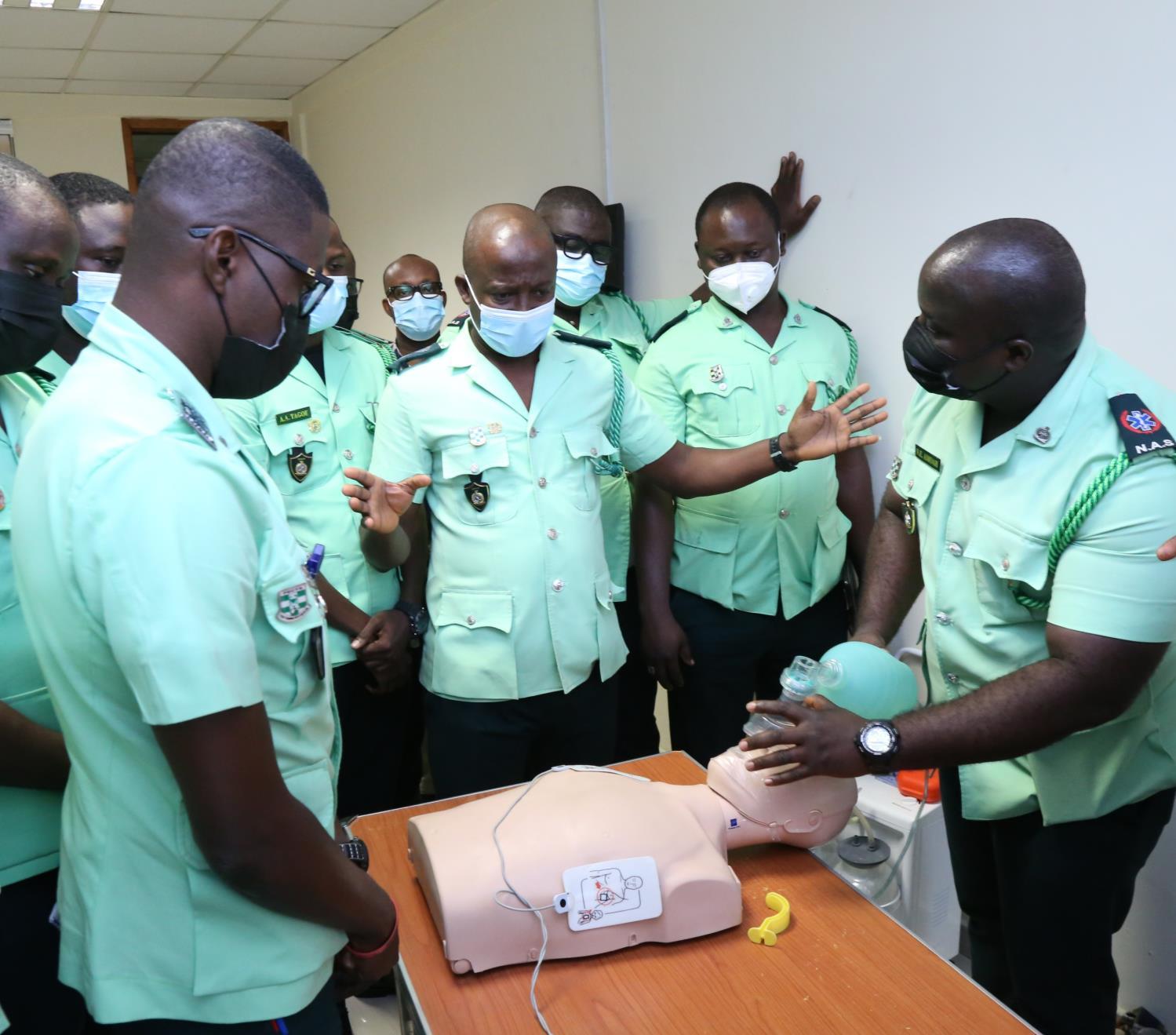

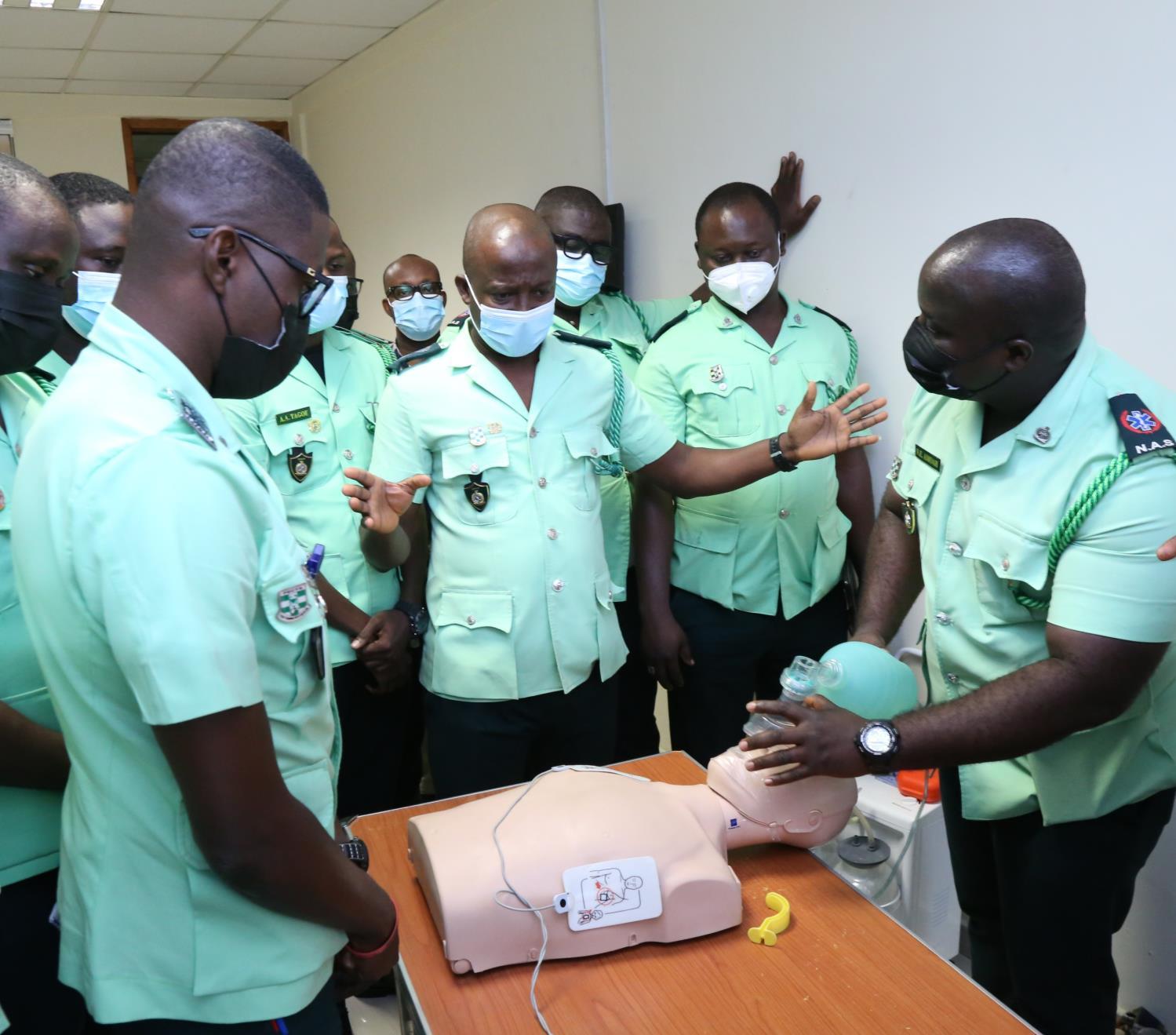

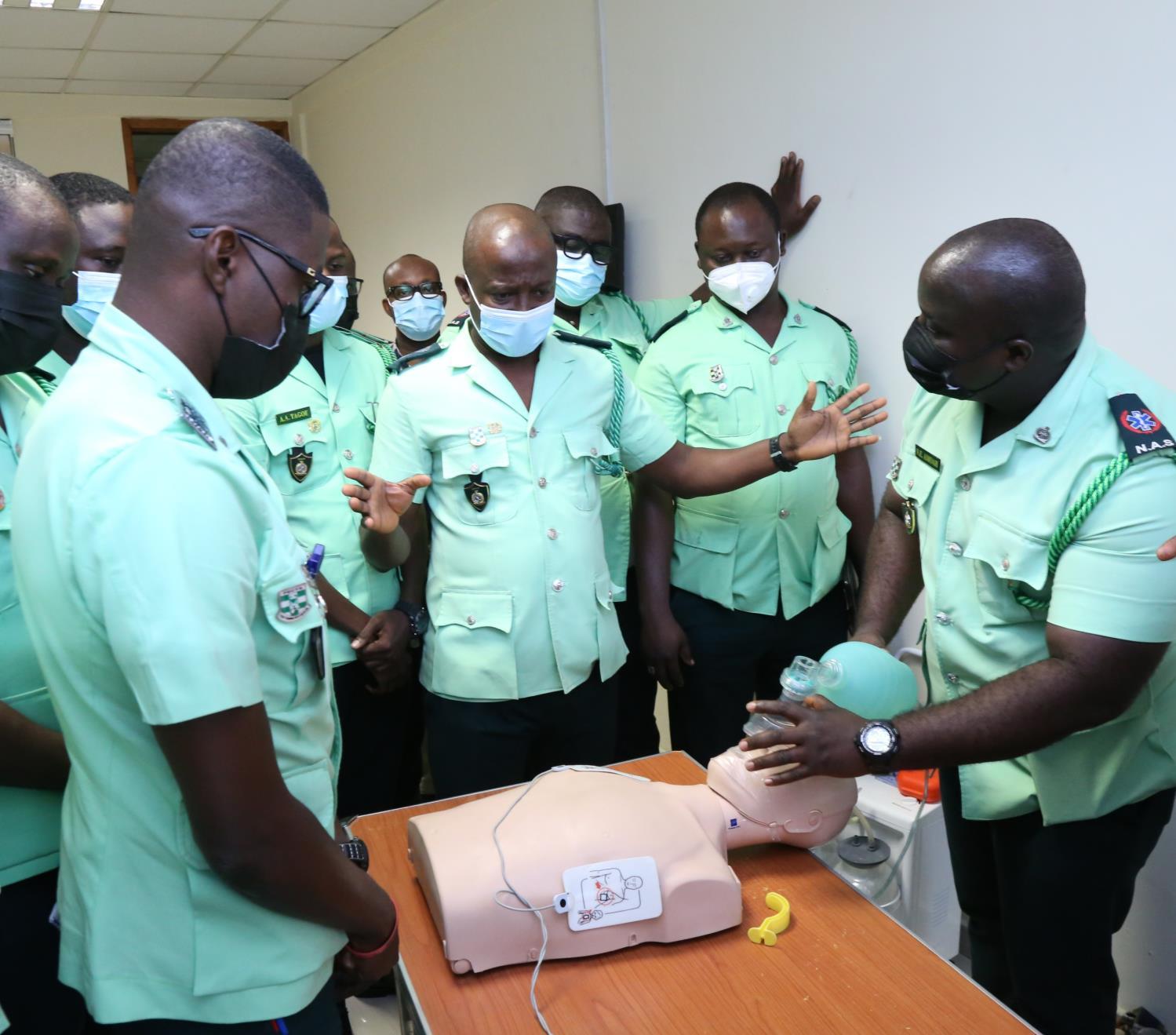

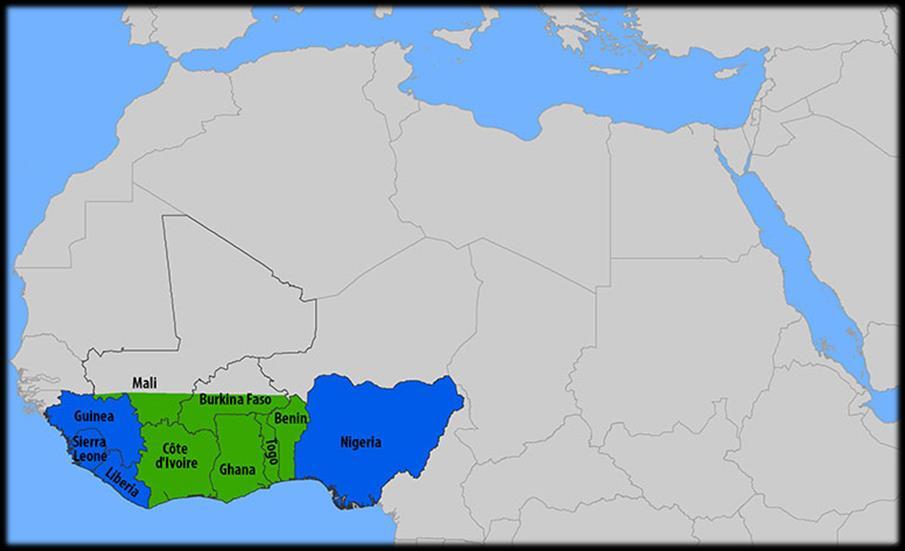

The College was quite busy this summer. I was invited by the National Ambulance Service of Ghana to come to Accra and certify their senior staff as ACLS instructors. I worked with them to set up their own ACLS training centre, and now they are self-sufficient and can provide their own ACLS certifications through ASHI in the U.S.

I am interested in seeing an improvement in patient outcomes once the Ghanaians have certified all 3000 EMTs with the ACLS programme. I plan to do a pre/post longitudinal study to see if this educational intervention will make a difference in outcomes.

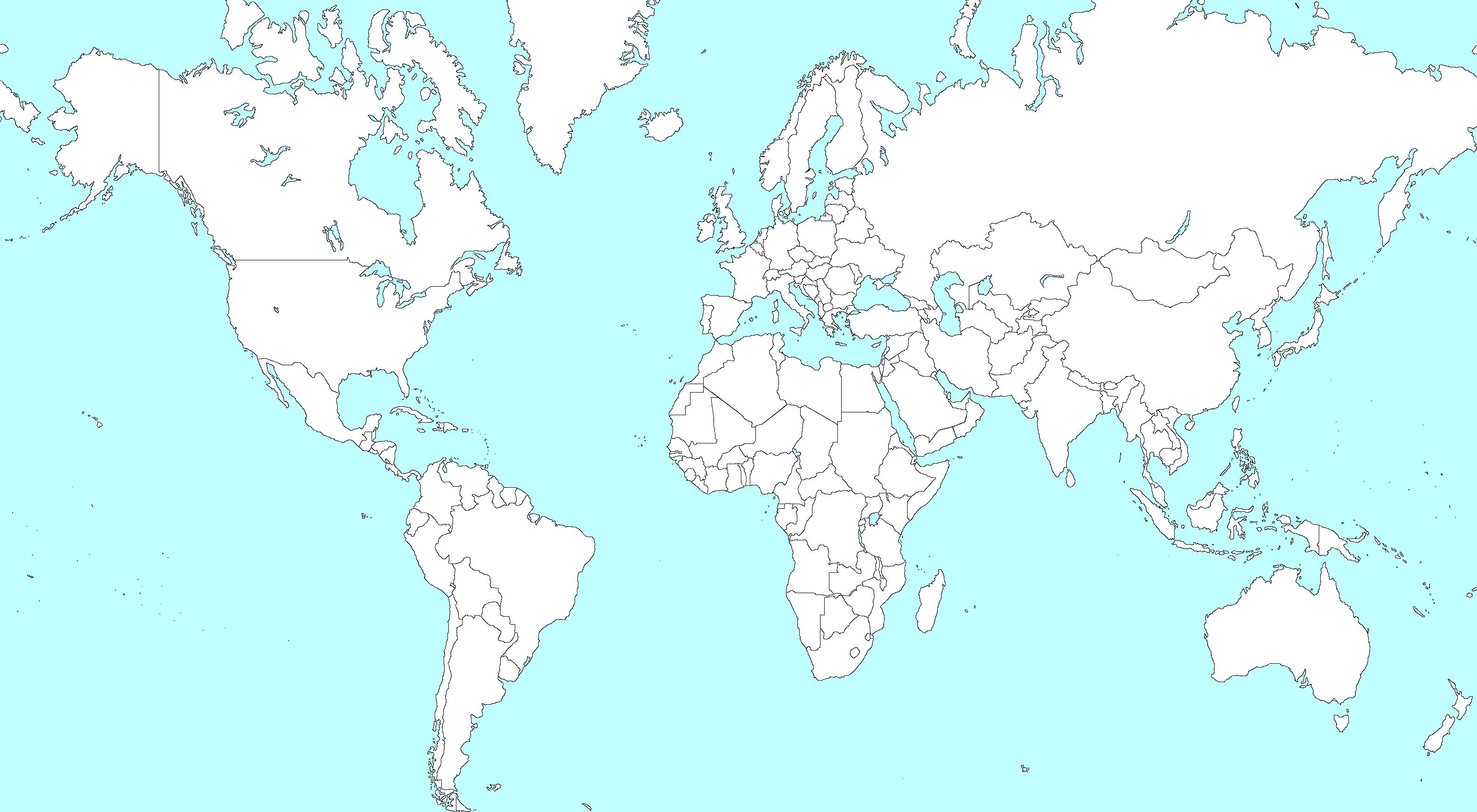

The College was invited back to the Special Operations Medical Association’s Scientific Assembly in Charlotte, North Carolina. Jason Jarvis gave a talk on tropical medicine updates, with a focus on the RTS,S malaria vaccine and the introduction of Aedes genus mosquitoes harbouring Wohlbachia bacteria into the wild as a means of mitigating arboviruses. Dr. deMello gave a lecture on the Biopsychosocial Approach to Pain Management for Military Operations, while I provided the Tactical Medicine Review workshop. The College is delighted to continue to support SOMA each year.

CoROM also ran a virtual workshop for the Combat Medicine Conference that is usually held in Ulm, Germany. I have enjoyed this conference over the past four years, but this time, we had to meet virtually. It was a challenge for me to create a Prolonged Field Care scenario over a virtual format. Typically, the PFC workshop at CMC is very much hands-on. But I managed to provide two lectures covering the basic concepts of PFC and the need for advanced nursing skills when dealing with a casualty for extended periods.

The College has started taking enrolments for the new MSc Austere Critical Care programme. We have 12 delegates so far and have a waiting list for the cohort beginning February 2022. We have a fantastic programme planned out for the delegates, including 10-12 subject matter experts holding virtual discussions on assessing and managing the critical casualty whilst working in resource-limited environments.

The College continues to move from strength to strength, and it is humbling to see what my team of professionals can create.

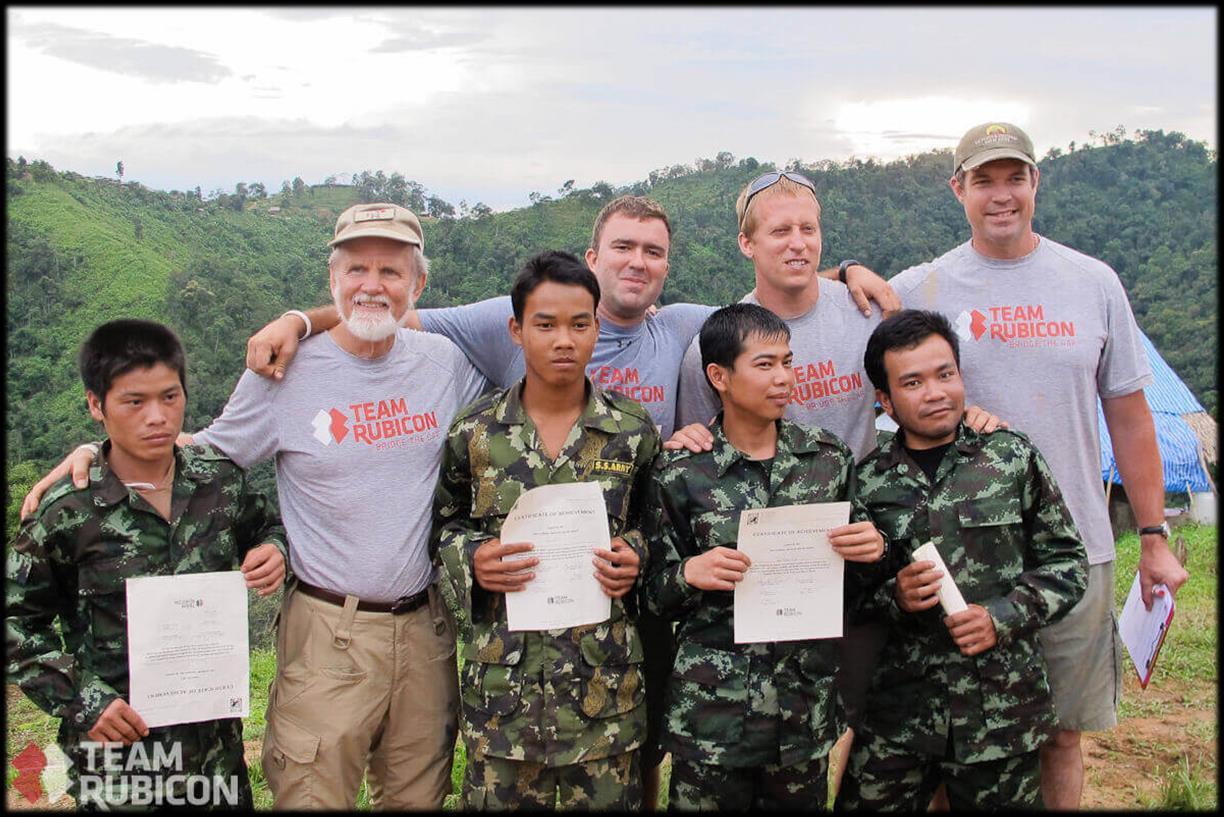

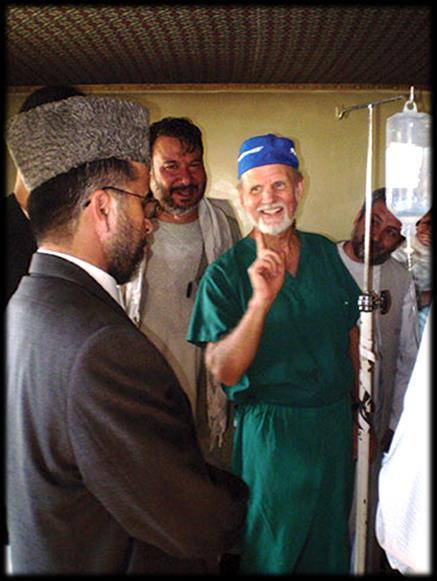

This was a highly enjoyable issue to put together. I have previously worked with four of the contributors – Hamida Ahmed (Ghana and Kenya), Dr. Glenn Geelhoed (Burma), Dr. Mike Shertz (Thailand) and Aebhric O’Kelly (many countries!) and it is gratifying seeing their continuing accomplishments in the field of remote medicine.

To Dr. Geelhoed in particular I owe a great debt, as his zeal for Tropical Medicine and all aspects of the natural world helped set me on the path to greater mastery of the intricacies of infectious diseases. I had the pleasure of visiting him at his home in Maryland last month during a training event in Washington, D.C., and he was every bit The World’s Most Interesting Man that I recalled from our Burmese jungle expedition ten long years ago. His unforgettable account of an encounter with a novel arenavirus in 1968 is the subject of the first medical case report.

Hamida Ahmed is a colleague of mine from my recent transect of Africa and is the author of this issue’s Special Report, in which she details her personal experience in assisting the victims of the 2013 terrorist attack upon the Westgate Mall in her home city of Nairobi.

Dr. Mike Shertz, whom I also had the pleasure of seeing again recently (at the annual SOMSA conference in North Carolina) has graced this issue of the Compass with our first nonhuman medical case report.

In this issue’s Trends in Traumatology I have shared the highlights of the Joint Trauma System’s newest Infection Prevention in Combat-Related Wounds clinical practice guideline.

Rounding out this issue is a drug calculation that I will admit took me more than a few minutes to solve (in the Test Yourself section), and recent literature on two new vaccines – the RTS,S malaria vaccine and the first vaccine to combat tick-borne encephalitis.

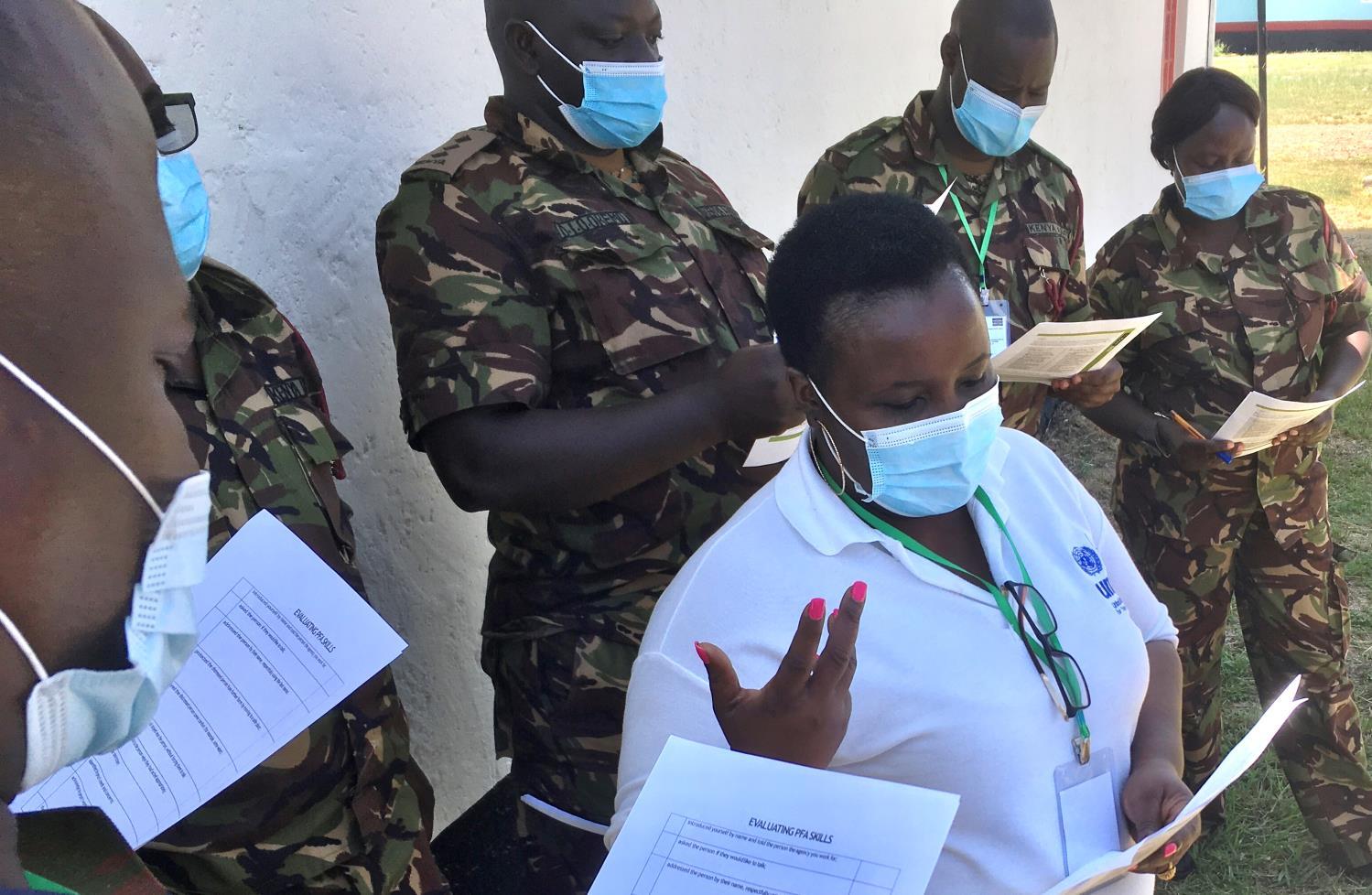

Jason Jarvis is CoROM’s Tropical Medicine Lead. He is a paramedic and former U.S. Army Special Forces Medic (18D) with years of accumulated experience as an austere primary care practitioner in resource-poor countries such as Laos, Burma, Iraq and Afghanistan. He recently completed his first transect of Africa, teaching deployment medicine courses for healthcare providers in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya under the auspices of the United Nations. Based in Seattle, Jason is a medical educator for Virtus, Harborview Medical Center, Raider Tactical, Allied Universal, 4 Site Group, CPR Seattle, LifeTek, and Children’s Hospital of Seattle. He is a recurrent presenter at the annual Special Operations Medical Scientific Assembly, an article reviewer for the Journal of Special Operations Medicine and International Health, and is pursuing a master’s degree in Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

It was around mid-day on the 21st September 2013. I was driving back home from my Saturday class at the campus. It had been a long hectic week and I couldn’t wait to reach home and relax. Balancing a full time job, being a doctoral student, mum and wife was taking a toll on me. Lost in my thoughts, my phone rung and one of my classmates informed me that there had been a terror attack at the Westgate Mall. This is one of the most popular upscale shopping malls in the city where families and especially the foreigners loved to hangout. She sounded terrified!! She however warned me not go to the site of the attack as it was unsafe. I had chills down my spine as I remembered that I was at Westgate the previous weekend with my son to buy a bike.

Hamida Ahmed Consultant Psychologist/Trainer

When I reached home, both the local and international TV channels were airing images of the on goings at the mall. It then dawned on me just how serious the situation was! I sat glued to the TV feeling angry, invaded but helpless! Apparently four masked gunmen had stormed the mall, detonated some grenades and started shooting at people indiscriminately. The extremist Islamic group al-Shabaab from Somalia claimed responsibility of the attack.

The following day, psychologists were asked to volunteer at the response centre. The Oshwal community in Kenya had offered their facility/temple which was about 200 metres from the mall as a response centre. Things were quite chaotic at the centre. There were people who had been rescued from the mall, family members looking for their loved ones, people crying, first responders, security agents, basically a lot of confusion. Kenya Red Cross and The Oshwal Community did a commendable job at setting up and coordinating desks providing different information for the various needs. These included information about casualties admitted in various hospitals and the missing. Different teams worked hard to collect as much data as possible. Donations of different supplies were also in plenty. The place was a buzz of activities.

The most unfortunate thing was that the attackers were still in the mall, and many people were still trapped in the mall. Once in a while we could hear heavy gunfire and even blasts. Twice we were asked to take cover in one of the halls and put our phones on silent. This was due to rumours that one of the terrorists had escaped the mall and may have come our way. We felt unsafe. I remember people frantically calling their loved ones to let them know that we had taken cover. My family members insisted that I needed to go back home as it was too risky. It was quite a chilling experience. Disturbing images being shared on social media platforms made it worse. I thought “I’m here to help, but I may end up dead!”

Once in a while a group of survivors would be rescued from the mall and rushed to the rescue centre. We continued to offer psychological First Aid (PFA). This is an intervention designed to reduce the occurrence of post-traumatic stress disorder in people who have had traumatic experiences. PFA is not therapy. Our job was to provide a humane, supportive & practical assistance to those affected. We listened, assessed the needs of the people and directed them to the necessary support.

It is hard to believe that the siege went on for four days! I would go home at night and go back to the centre early the next morning. We continued to provide PFA to the survivors and their families. It was tough listening to the horrifying stories of what the survivors had witnessed in the mall. One assignment that I was given was to support members of staff of a popular radio station. They had a children’s cooking competition at the rooftop of the mall that Saturday. Unfortunately, they were attacked and lost a member of staff. She was pregnant! I had to support her grieving family and colleagues. Sad!

When the siege was over, 67 people were reported dead with over 100 injured. Three floors of the mall had collapsed. It was clear that many people were traumatised. The Kenya Red Cross in partnership with The Kenya Psychological Association(KPA) set up a project to provide trauma psycho-social support to those affected. The project lasted for several months. I was part of the team of the psychologists recruited to provide skills for psychological recovery (SPR) and trauma therapy. It was not easy listening to clients sharing their experiences. We also attended to the armed forces and other first responders involved in the operation. As a country, this traumatic event brought to light the importance of mental health care. After Westgate, unfortunately, we have had to respond to other terrorist attacks, but have become better at coordinating response and interventions.

On the 18th July 2015, almost 2 years after the attack, Westgate mall re-opened, and is now one of the safest malls in the country. However, it took me 2 years to get the courage to return to the mall after it was re-opened. The Westgate terror attack experience will stay with me forever. However, I have also developed a passion in trauma work. I have since responded and intervened to other terror attacks, and continue to respond because I know that my contribution makes a difference in people’s mental wellbeing and their lives in general.

Working in public relations means it is my responsibility to bring together communication campaigns for healthcare clients which drive behaviour change. This can mean launching new drug therapies or medical devices to healthcare professionals to drive awareness, driving the public towards healthier lifestyles as part of government and NGO initiatives, or helping patients understand a medical condition by creating interactive educational content.

My previous campaigns have included a fertility awareness campaign across 11 countries in Asia to encourage couples to seek appropriate help, and promotion of a multi-year public engagement plan for anti-smoking and obesity for Singapore’s Health Promotion Board to encourage participation in community activities.

Healthcare marketing around the world is rightly defined by regulations and guidelines and when driving a healthcare message to patients, doctors or the general public, it is easy to stick to safe and sometimes bland messaging to ensure campaigns don’t fall foul of these regulations. This serves no one well.

In a world of massively fragmented media channels, creating a campaign that resonates with the intended target audience takes much more effort to be successful, especially if the topic is taboo in society. Campaigns must be based on strong insights and be creative and bold in their execution. In addition, when targeting specific age groups; knowing when to utilise social media, local influencers and the trending topics of the day, can mean the difference of reaching the intended target or missing them completely.

Ultimately, creating a memorable campaign is the perfect cocktail of insights, science which backs up every claim, original, bold creativity and respect for local healthcare marketing guidelines.

AGENCY CAMPAIGN - Singapore’s One Million KG Challenge aims to slow down the rate of increase of obesity and to raise awareness of the importance of long-term healthy weight management.

AGENCY CAMPAIGN – Fertility Awareness

Month - An Asia-wide campaign across different media channels to drive attendance at Fertility educational events customised to the language, cultural and regulatory requirements of each country taking part.

AGENCY CAMPAIGN – Taiwan Aids

Society: Driving change to legislation to eliminating bias against HIV sufferers with a public education and a media outreach programme.

Simon Ruparelia is a second year student of the CoROM BSc Remote Paramedic Practice programme. He is also completing a Postgraduate Certificate in Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and is a Wilderness Medical Society Fellowship (FAWM) candidate. He has lived and worked in Singapore for 10 years in his current role as Head of Growth for Golin, a global public relations agency.

Simon Ruparelia completed 400 hours in the Emergency Medicine Department at KCMC Hospital, Tanzania in 2019.

There are geographic “addresses” that have been identified with health and longevity and they have been described with dubious claims to be “healthful locations.” Ponce de Leone considered that the Timiquan Indians he encountered around the Bay of St Augustine in what would become Florida were unusually fit and long-lived in comparison to their Spanish counterparts, which induced him to go in search of the elixirs of the Fountain of Youth that must have been the reason for their good health. We have not escaped these hopes and contemporary investigators seek out the “keys to longevity” in the healthy elders of the Caucasus, or the “stress-free lifestyle” of the citizens of Vilcabamba Ecuador to try to borrow or adapt whatever the place confers upon its residents in long-lived health.

There are also geographic locations with bad reputations for association with diseases and death. Rome was built on Seven Hills to get above the “miasmas and rheums” of the lowland swamps around the ports over which hung “bad air” from which they attributed the fevers of “mal aria.”

In the myriad of biologic diversity that the tropics represents, some of these places are micro-endemias from which emergent illness can arise and may even take the place name as its designation.

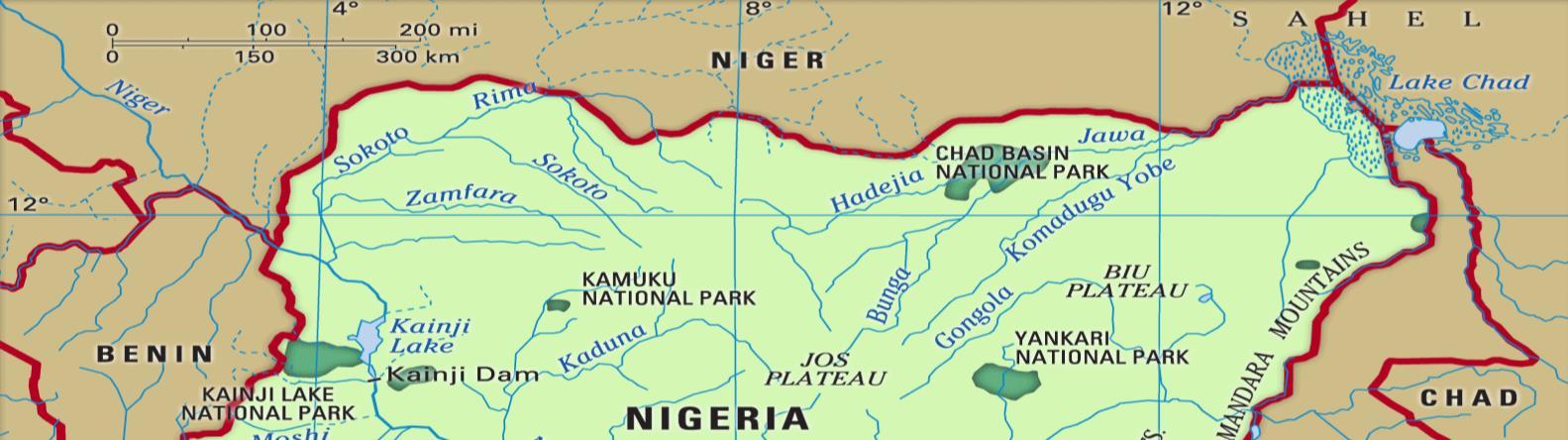

I was a young and ingenuous clinician working in my first-ever entry into tropical Africa in January 1968 when I encountered a disease pattern certainly never before seen by me and I attempted to describe and characterize it, being unaware that the illness had not yet been identified by others besides me.

I had entered the Nigerian north through Jos, after having been delayed by the harmattan winds that bring down sandstorms from the Sahara blotting out visibility for flying in light aircraft. On arrival in Jos I had been introduced to a young woman physician named Susan Troup who with her two nurses Penny and Char was managing a small hospital at Hillcrest. I made rounds with Dr. Troup and the nurses at the Bingham Hospital and they had hosted me at their home showing me around their rose garden; each of them was an avid gardeners and had the rose thorn wounds to prove it.

I went on to be working in what would become Benue River State after the Biafran War in the Nigerian north, based at Takum Christian Hospital, making brief sorties into the Nigerian bush to remote rural villages to hold clinics and give immunizations. The Sudan United Mission had made available a Piper Comanche light aircraft to reach some of the villages beyond road access, and on one occasion, the missionary pilot Ray Browneye and I had flown to a remote airstrip to hold the promised clinic at an adjacent village.

On approach to the airstrip I could see upstart mountains rising from the guinea savannah behind the village surrounded by dry season bush, and considered the stark scenery hauntingly memorable.

On arrival I could not continue in those reveries, since there was great consternation in the village population and the planned clinic with orderly review of scores of patients was disrupted by an emergency. The crisis involved the head man of the village who, uncharacteristically, had not been at the front of the greeting party since he had recently fallen ill himself. He was a very prominent citizen of this Hausa community, and was so well traveled that I was told he had even been to Germany at one time in his life. He was unable to communicate with me or the translators, however, since he had a very high fever and had lapsed in and out of unconsciousness before he began to seize.

The fever had been consistent for thirty-six hours but the seizures had just begun. Before the fits, an attempt had been made to take his temperature reading on an oral glass thermometer, which could only register up to 105° F, and his temperature had exceeded that calibration. He had already bitten his tongue during one of his seizures and I attempted to insert an oral airway through his foamy sputum and bloody lips to prevent him from losing his airway in his unconsciousness. I used up the whole bottle of rubbing alcohol I had brought in bathing him to bring down the fever and had injected a barbiturate through the intravenous line started to deliver what other medicines we carried which included one ampoule of diazepam. As I watched rather helplessly, he suffered an apneic seizure and then his spasms drew him into head-to heels opisthotonous and he collapsed with dilated pupils. I attempted mouth-to-mouth ventilation using the oral airway and intermittent chest compressions, but there was no return of vital signs.

This event brought about great ululation among the mourning villagers and I withdrew to the quieter airstrip to use the radio in the Comanche single-engine aircraft to call Hillcrest to speak to Dr Troup for advice. After my description of the terminal events, there was a long pause following which she said, “I believe you should get up here as soon as possible and we will start you on the series of anti-rabies injections.” Perhaps fortunately for me, as I had little enthusiasm for the encephalitis that I had heard might often follow the series of rabies antiserum made from a crude preparation of an extract of mashed primate brains, nightfall was upon us which would not allow the flight under VFR (visual flying rules) and any possibility of flying the following day was again shut down by the impaired visibility of the dry season harmattan.

I went about seeing the list of patients, selecting those with surgically fixable problems such as hernias and hydroceles and one cryptorchid eight year old boy, to be scheduled when these patients could make their way to Takum, and treated the inflammatory and infectious problems as well as de-worming the villagers.

By the next day, the village head man had been buried and we were ready to fly back to Takum, with many more unresolved questions carried back from this village which had appeared so haunting on my first approach. I later heard from pilot Ray Browneye that he had returned several weeks after our visit to the same village and had done a medical evacuation for another man with a similar high fever. Ray had delivered the patient to Bingham Hospital where Dr. Troup and her nurses tried many of the same things I had tried with considerably better inpatient facilities, but with the same outcome. With my report to her from the field and this puzzling similar case before her from the same village, Susan Troup assisted by nurses Penny and Char set about doing a limited post-mortem examination, collecting blood and biopsy samples for later microscopic staining, culture and histology. The hubris of the rose thorn punctures is memorable in retrospect for these three heroes, as each of them became ill with a high fever shortly thereafter, to which both Susan and Char succumbed.

Penny struggled through the delirium of high fever and could only be given supportive care against this unknown illness which had already claimed the lives of her two closest friends. In a slow and gradual recovery, her own convalescent serum along with the blood and tissue biopsy specimens she had helped obtain were examined at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York which made it possible eventually to identify the causative agent of this severe illness, described and named [see the book “Fever” published later from this experience] only after each of us had encountered it first hand as an unknown.

It was Penny’s convalescent serum that became the therapeutic agent that salvaged the next patient from this region who presented with the same mysterious until-that-moment unknown contagion. I remember well my own encounter with this mysterious plague, but recollect more vividly those who stood up against it.

And the name of the village?

Lassa.

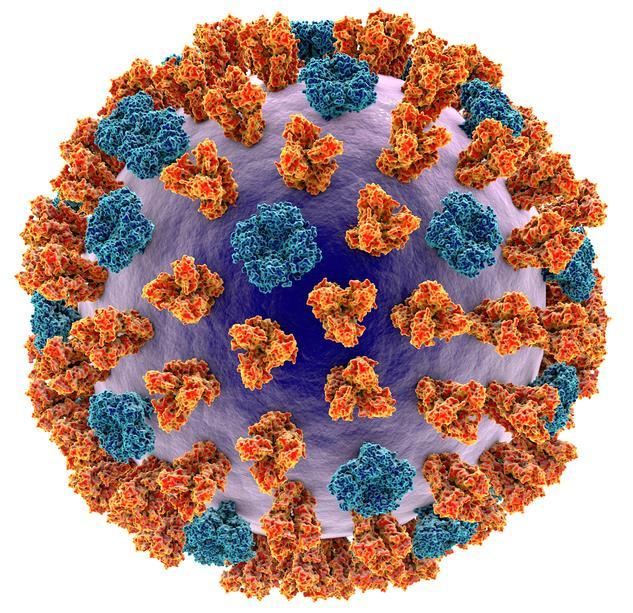

Lassa virus is an enveloped RNA virus in the arenavirus family, and is further grouped among VHF (viral hemorrhagic fever) viruses such as Ebola, yellow fever, and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever.

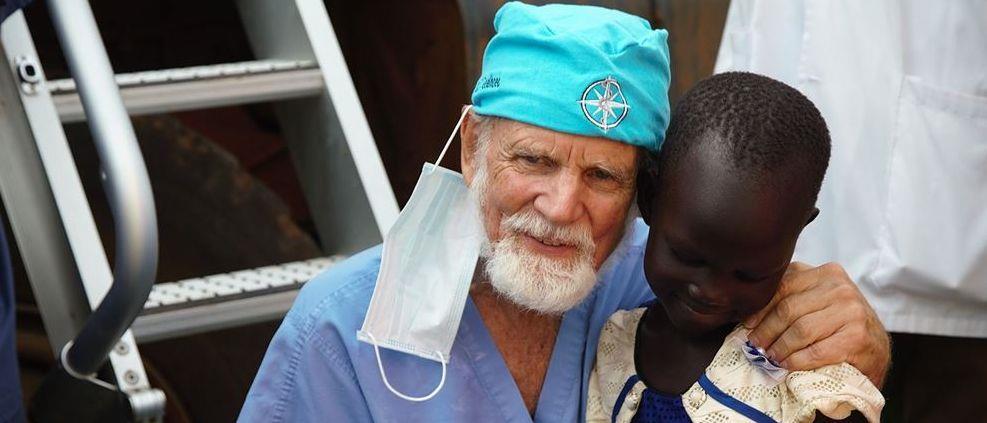

Dr. Glenn Geelhoed received his BS and AB cum laude from Calvin College and MD cum laude from the University of Michigan. He completed his surgical internship and residency through Harvard University at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital Medical Center. To assist in developing further volunteer surgical services in underserved areas of the developing world, Glenn completed masters degrees in international affairs, epidemiology, health promotion and disease prevention, anthropology, and a philosophy degree in human sciences.

He still works as a professor of surgery at George Washington University Medical Center in Washington D.C. and is a member of numerous medical, surgical, and international academic societies. Glenn is an avid game hunter and runner. He has completed more than 135 marathons across the globe. He is also a widely published author accredited with several books and more than 500 published journal articles and chapters in books. He has two sons and five grandchildren.

Martyna is a Polish paramedic currently working in Malta. She joined CoROM in 2019 as an ACLS and ITLS instructor. Her special interest lies in training children in Basic Life Support and developing effective training programs for pre-school children through play and games.

During my student years I discovered great pleasure in sharing knowledge with fellow students. I actively participated and taught on all sorts of training and courses which my science club was offering to the public. After moving to Malta I lost that opportunity, and from time to time while teaching BLS for hospital employees I knew that there was something missing in my life. When the opportunity arose to join CoROM, I saw all of the various courses and educational experience they were offering, and without hesitation I sent my CV hoping to be accepted. The most tempting was the chance to work with clinicians from all around the world with a different backgrounds and experience. The work with CoROM does not mean just sharing knowledge with the students, but constant and active learning from other colleagues and above all the friendships I had the opportunity to gain.

However silly it may sound, my favourite topic is Basic Life Support. We may know all drugs of the world, possess the most advanced equipment and have multiple medical titles, but without basic knowledge of life support we won’t save anybody. Correct performance of BLS is often downplayed by health care professionals as obvious knowledge not requiring refreshment and training. That approach can produce multitudes of caregivers failing to provide basic life saving manoeuvres. My special interest is in developing the most effective ways to train pre-school children in the delivery of BLS and implementing a system which would require BLS education from the earliest stage from the National Education System.

Martyna Abratkiewicz BSc (Hons), Paramedic

Martyna Abratkiewicz BSc (Hons), Paramedic

Where would you like to see CoROM go in the next five years?

I started my adventure with CoROM when the college was offering short term courses. During last 3 years we opened BSc and MSc programs which are the first paramedic degree courses offered in Malta to students from around the world. I see huge potential and will in the people participating and managing this project. I strongly believe that CoROM is just creating part of Maltese history and hopefully in the future has a chance to introduce the much needed paramedic profession on our little island.

It is difficult to choose one, but a particular case of a 30-year-old male in stage IV of melanoma stands out in my memory. The only action required during transport was a morphine infusion to make his last journey to the hospital tolerable. This patient arrested on the hospital driveway. Cases like this make us aware that no matter how much knowledge we gather we need to know when to let go, which sometimes is the hardest part of our job. This knowledge is not taught in university, this is the knowledge we gain in the hardest way, by personal experience.

I would definitely recommend CoROM field guide which always accompany me at work. However, in the digitalize world one cannot forget about useful mobile apps. I am currently using the British National Formulary whenever I am in doubt regarding medications. The huge disadvantage of the application is that it’s not available in every country. Last, but not the least JRCALC Plus, which is a set of guidelines for most of the clinical scenarios we may encounter during our clinical practise.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTMH

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTMH

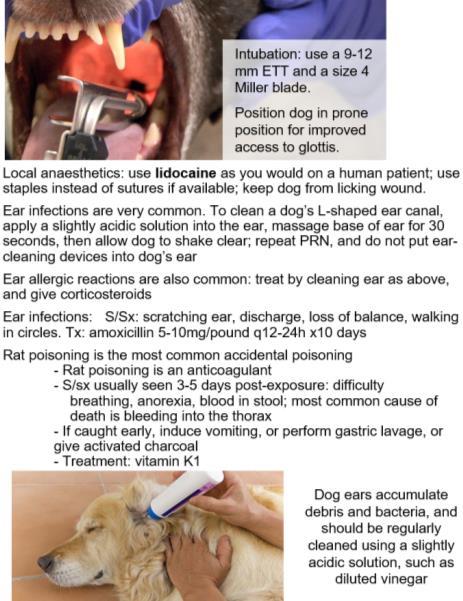

While providing medical support for an oil field in West Africa, you are frantically brought a 30kg operational canine used for site security. The German Shepherd dog and handler were conducting bite work training when the K9 rapidly developed ‘weird breathing”,’ seemed increasingly agitated, and now - twenty minutes lateris less responsive and struggling to breathe. The handler denies any recent injury, illness, or obvious envenomation for the K9.

The K9’s heart rate is 140 beats per minute, with a weak femoral pulse. You know from prior K9 TECC / TCCC training that these signs fit with early decompensated shock. On lung examination, there are markedly decreased breath sounds in the right lung. It is hard to say on the left lung because of the commotion of the handler and onlookers.

No wounds are found on rapid physical inspection, using an “ice scraper” hand / finger position, raking against the grain of the animal’s fur. As their fur hides small wounds and bleeding, a K9 blood sweep needs to be “against the grain” to help get down to their skin. Additionally, their tail is a “fifth” limb” and needs to be checked. Finally, this K9’s abdomen is soft and seemingly non-tender.

Deciding that an oxygen saturation reading would be helpful in clarifying that this animal has a respiratory problem, you roll up the K9’s tongue and insert it into your fingertip pulse ox monitor. Fingertip pulse oximeters don’t really work on K9s unless the animal is quite comatose or sedated. There are “ear clips” specifically for K9s that can also be used on the tongue, lip, and or genitals. This K9’s O2 sat is 84% on room air. The oximeter does seems to be correlating with the animal’s heart rate of 140, so you believe the number is accurate.1

What is on your differential diagnosis for this athletic operational K9 who developed substantial difficulty breathing, tachycardia, hypotension, and hypoxia over twenty minutes?

Infection seems unlikely based on the rapidity of onset and lack of prodromal signs and symptoms.

Metabolic causes like heat injury are very possible. It is one of the top three killers of operational K9s in both military and law enforcement settings.2,3 K9s typically run higher body temperatures than humans. Temperatures as high as 39° Celsius are common. Heat injury in an operational K9 can result in altered mental status, wobbly weakness, and possibly seizures. Heat injury or metabolic causes wouldn’t be expected to cause respiratory distress and hypoxia. Trauma seems unlikely as the animal didn’t seem to sustain any injuries.

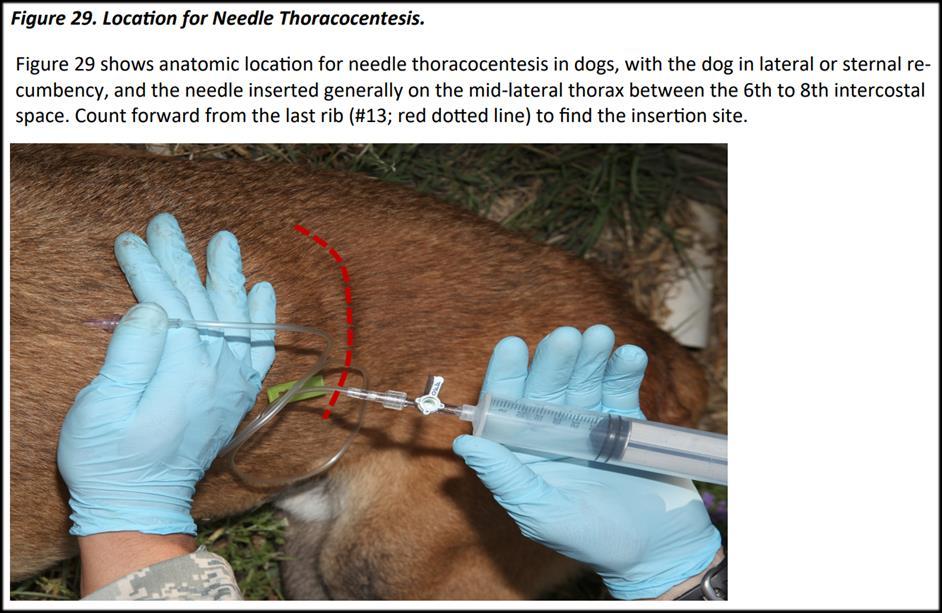

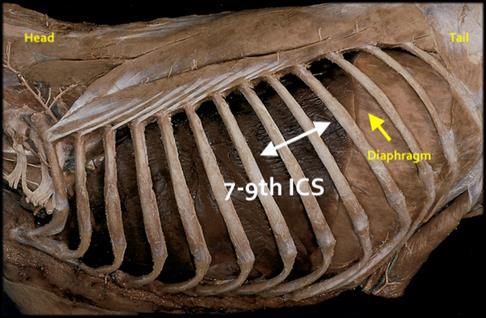

You decide the K9 is in enough extremis to justify needle decompression. K9s have 13 ribs, not 12 as humans do. With the K9 on its side (called the lateral recumbent position) you figure the needle and catheter should enter low and at least midway across the K9’s side. Upon placement of your standard 8cm 10-14 gauge needle, you immediately hear a loud rush of air. Figuring the animal is not adult humansized you only place the needle/catheter unit halfway in and then remove the needle. Once the chest is fully decompressed, you can hear air moving in and out of the catheter, indicating resolution of tension pneumothorax. As the animal’s vital signs normalize its altered mental status also improves.

K9s have an incomplete or fenestrated mediastinum, so when they get tension pneumothorax, it can occur bilaterally. This can require bilateral decompression. The phenomenon of spontaneous pneumothorax occurring during bite work has been seen. One trauma veterinarian I’ve spoken with has managed five cases personally. I question whether it is related to a forceful Valsalva during the initial hit on the bite. In humans, 16.9% of spontaneous pneumothorax goes on to tension pneumothorax.4 This can be difficult to diagnose without the presence of external chest wall injury. Needle decompression is similar, but performed at the 7th to 9th intercostal space. With the heart lying anterior in the chest, placing the needle/catheter about 2/3 up the lateral chest wall is best. In this case, figuring the K9 will likely need a chest tube for presumed spontaneous pneumothorax, you decide to provide ketamine for sedation while the K9 is transported to the local veterinarian with whom the company has previously made arrangements for care. Ketamine dosing in K9s is the same as humans, however, K9s seem to suffer from significant emergence reactions with it, so benzodiazepines are always recommended for coadministration.1

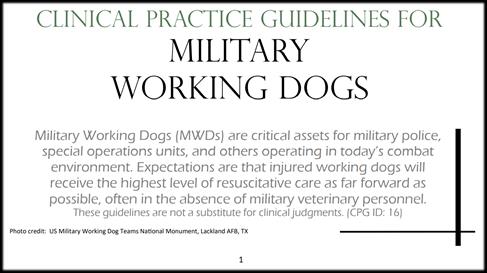

1 JTS Military Working Dogs Clinical Practice Guidelines: https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Military_Working_Dog_CPG_12_Dec_2018_ID16.pdf

2 Miller L, Pacheco GJ, Janak JC, Grimm RC, Dierschke NA, Baker J, Orman JA. Causes of Death in Military Working Dogs During Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001-2013. Mil Med. 2018 Sep 1;183(9-10):e467-e474.

3 Stojsih SE, Baker JL, Les CM, Bir CA. Review of Canine Deaths While in Service in US Civilian Law Enforcement (2002-2012). J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Winter;14(4):86-91.

4 Yoon JS, Choi SY, Suh JH, Jeong JY, Lee BY, Park YG, Kim CK, Park CB. Tension pneumothorax, is it a really life-threatening condition? J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013 Oct 15;8:197

See Also: K9 TECC Guidelines: http://users.neo.registeredsite.com/1/2/1/13151121/assets/K9_TECC_FINAL_JSOM_TacMed_Updates_AU_ 1.pdf

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former U.S. Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E, MA, FAWM DipPara, CCP-C, TP-C

The College has been teaching the virtues of Cling Film for many years. I finally decided to do this article and quickly turned to PubMed, as I usually do for all of my writing. There are plenty of articles discussing the use of Cling Film on burns. Hudspith (2004) showed that covering the wound protected it from bacteria in the air. It reduced pain and kept moisture from oozing out of the wound.

Mclure et al. (2013) reviewed current burns guidelines and found similar results but particularly noted that Cling Film should not be applied to the face. I asked them what they would suggest using instead, but they did not comment. At the College, we put Cling Film on facial burns but always apply it in thin strips to allow movement. The burns are usually wet from moisture seeping from the wound, which helps the cling film easily adhere to the burn. The NHS mentions many times on many web pages that Cling Film should cover the wound once it is cooled.

So, the research confirms that using a non-occlusive (and sterile) dressing on cooled burns. That is reason enough for having a roll of Cling Film in your medical bag. But there are more justifications for having Cling Film close to hand:

• It can be used on wet plaster of Paris to protect the cast until dry

• It is very effective in covering an IV site. It allows you to visually inspect the IV site without having to remove bandages.

• It can also be used to secure IV lines, EKG lines and other items usually scattered around at trauma sites.

• It can be used to secure your 3-lead ECG to the upper arm of the casualty, where it will always be easily read and assessed.

I try to motivate our students and our faculty to push for Cling Film during all parts of the patient assessment and management. Cling Film is sterile, cheap and always available in practically all parts of the world. Most remote villages that I have visited use Cling Film. You can find it in the kitchen of your offshore oil rig. You can find it just about anywhere.

Therefore, there is no reason you, as a Remote Medic, do not have a roll in your medical bag.

Resources:

1 Hudspith J, Rayatt S. First aid and treatment of minor burns

BMJ 2004; 328 :1487

2 Mclure M, Macneil F, Wood F M, et al. (June 20, 2021) A Rapid Review of Burns First Aid Guidelines: Is There Consistency Across International Guidelines?. Cureus 13(6): e15779.

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/burns-and-scalds/treatment/

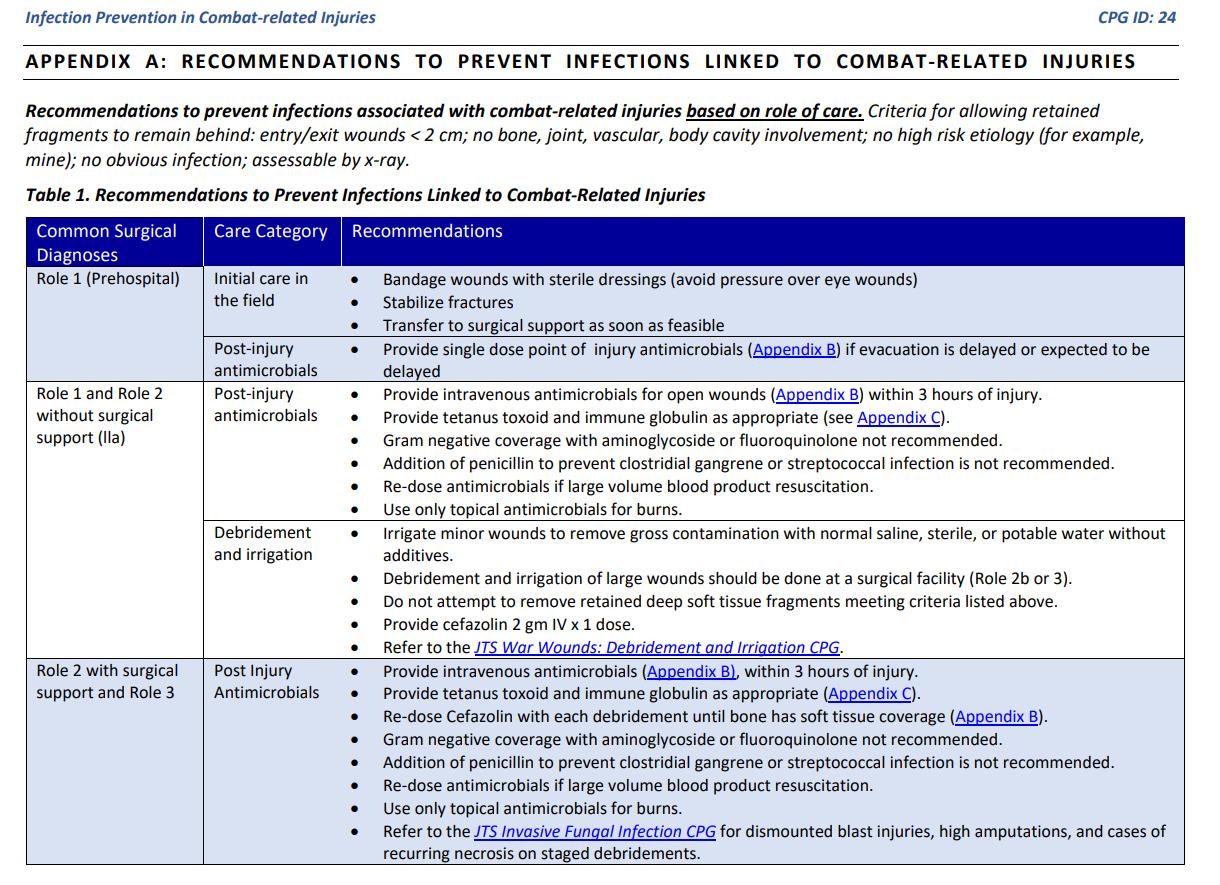

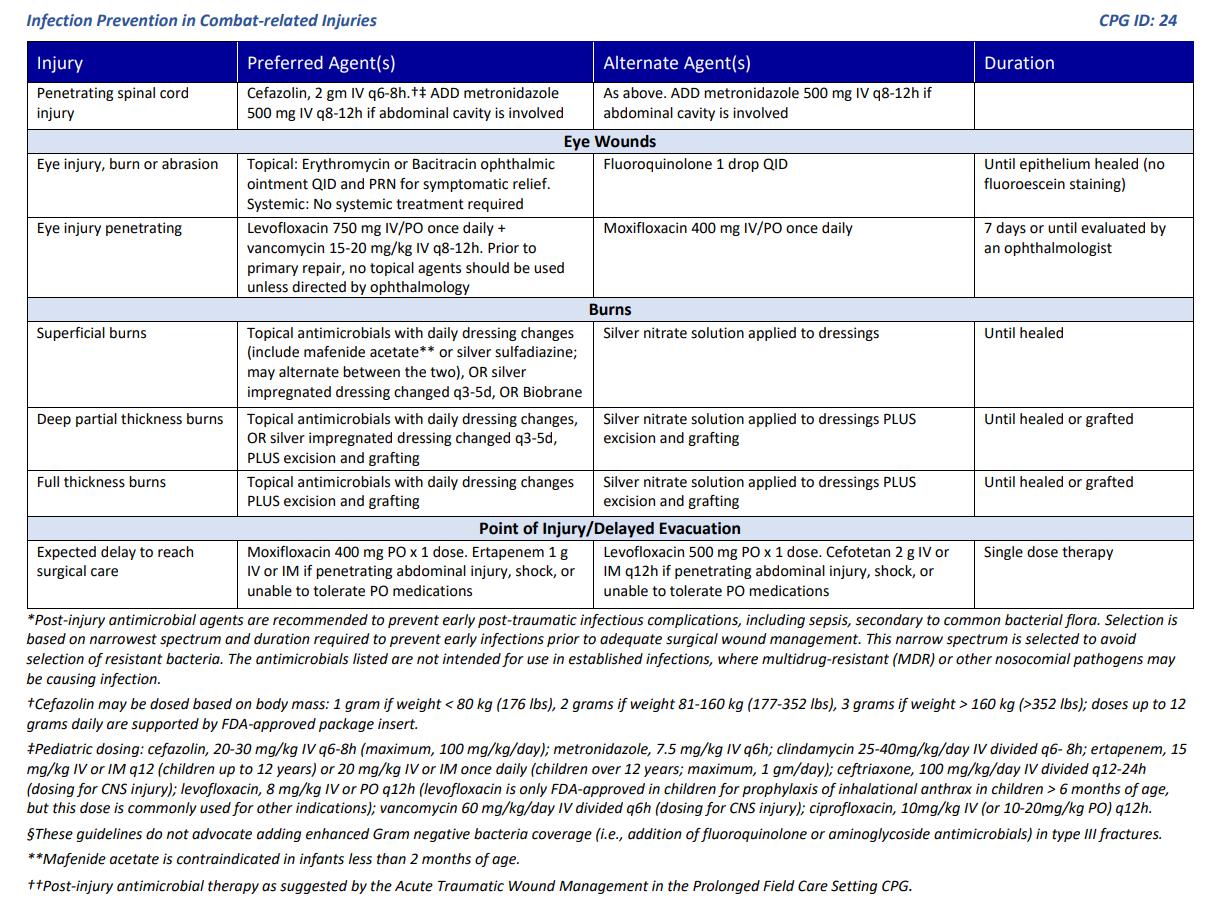

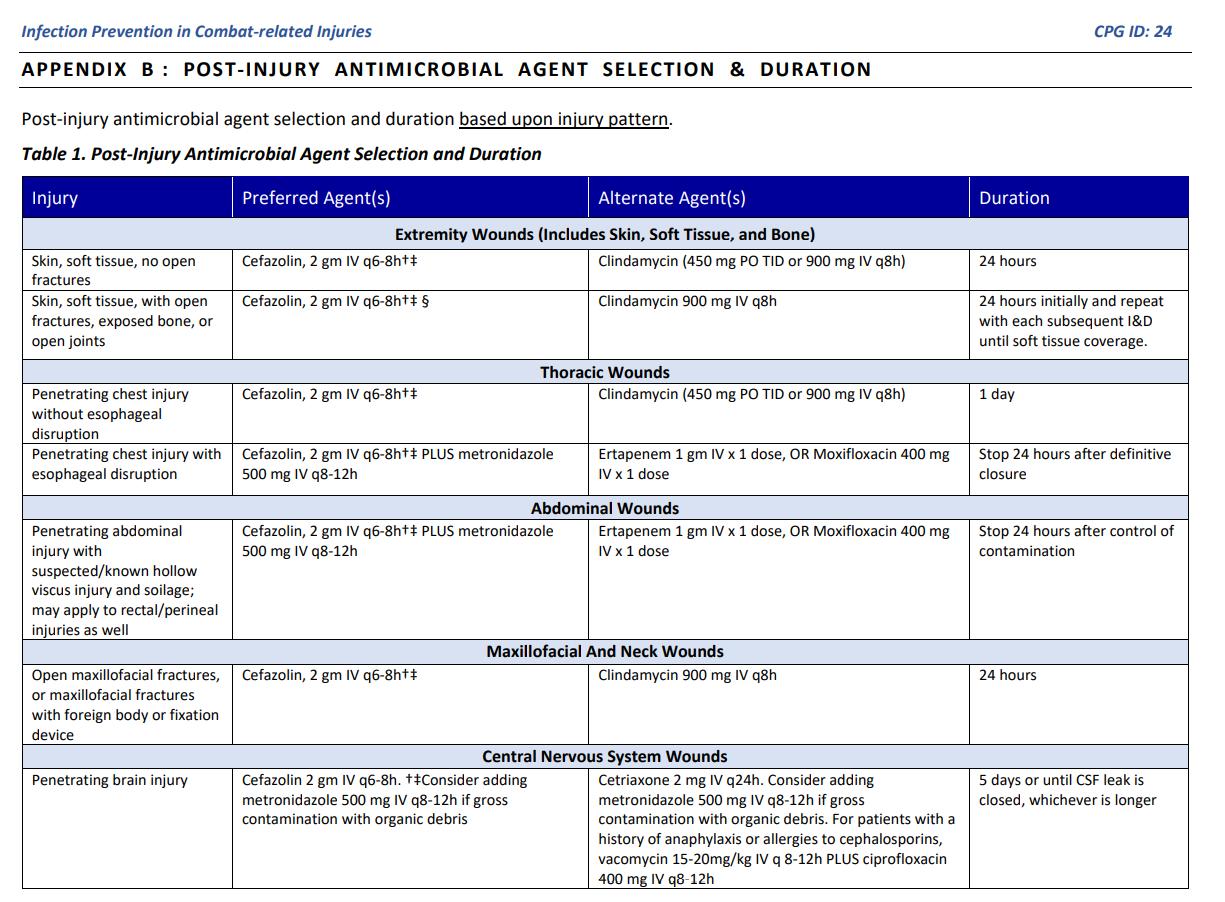

Prevention of wound infection should begin as soon as life-threatening injuries have been dealt with. Assuming the casualty can swallow medicine, the first infection preventive modality may be the casualty’s own Combat Wound Medication Pack (CWMP), containing the following medications: 15mg meloxicam, 1000mg paracetamol (acetaminophen/Tylenol), and 400mg moxifloxacin, a powerful broad spectrum antibiotic in the fluoroquinolone drug class.

The pain relief from the CWMP may be marginal, but every effort must be made to aggressively dampen the severely-wounded casualty’s perception of pain, which goes a long way toward preservation of his or her immune system. Additionally, the sooner antibiotics are administered, the less severe will be the wound infection. Wound irrigation and debridement are just as – if not more – important than antibiotics, but it is not usually practical to begin these processes just after the point of wounding in a field setting.

As soon as vascular access has been attained, the healthcare provider may begin administering more powerful analgesics and antibiotics than those contained within the CWMP. Note that many of these IV drugs may be given intramuscularly, an important consideration when choosing antibiotics and analgesics, as quick intravascular access is never guaranteed in the field setting. Besides the standard medicine administration routes, one should also consider the transmucosal route (fentanyl), intranasal (ketamine) and regional nerve blocks (lidocaine and/or bupivacaine). Psychological first aid, as described by Hamida Ahmed in this issue’s Special Report, is an another key component in decreasing suffering and in turn bolstering the immune system.

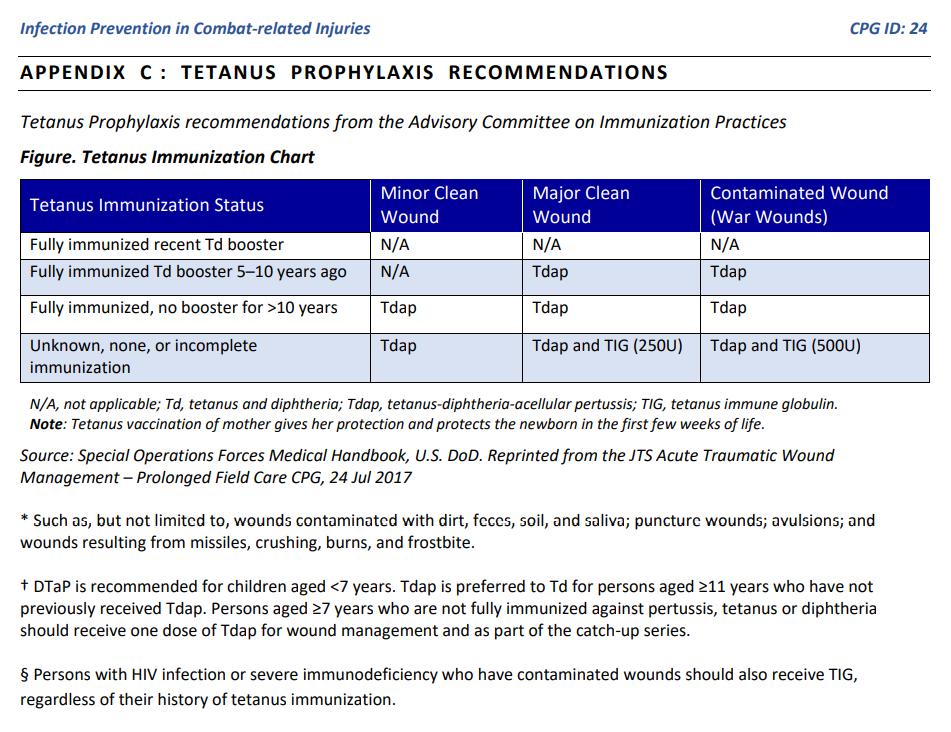

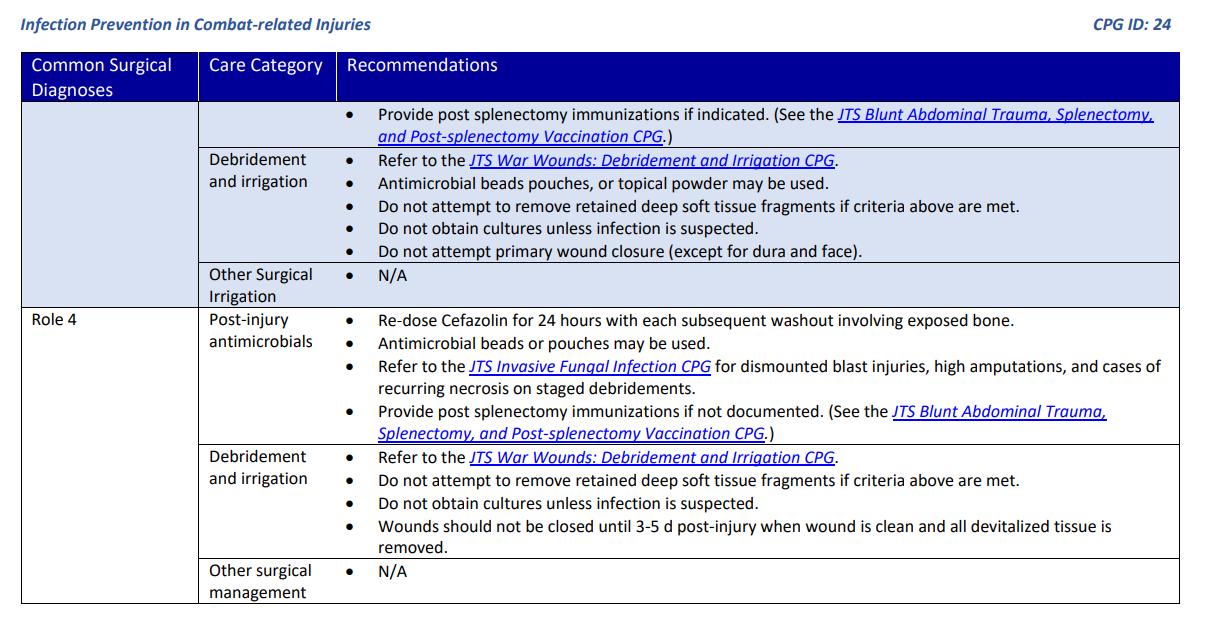

On 27 January of this year, the U.S.’s Joint Trauma System published an update to its Infection Prevention in Combat-Related Injuries Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG), the highlights of which are reprinted on the following pages.

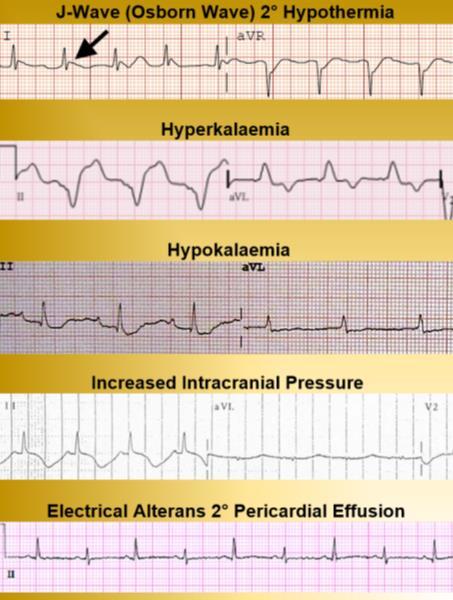

Which of the following pathologies is the most likely cause of the anomaly in this ECG?

A. Dehydration

B. Guinea worm disease

C. Right-sided heart failure

D. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Following the retrieval of a climbing team member who fell into a crevasse on Kangchenjunga, you note a massive contusion of the head, symptomology consistent with Cushing’s Triad (bradycardia, widened pulse pressure and irregular respirations), a GCS of 10 and unilateral pupil dilation. Using the 2020 TCCC clinical practice guidelines, you decide to administer 250mL of 3% saline to treat the apparent increased intracranial pressure. You have 250mL bags of 0.9% saline and a 30mL vial of 23.4% saline; what combination of each of the fluids will yield 250mL of 3% saline?

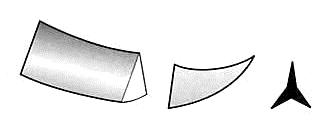

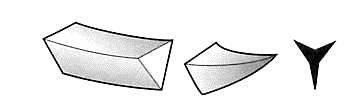

You are preparing to close a longitudinal laceration on the knee of an expedition member in remote British Columbia. You should use which of the following types of suture needles to close the skin?

A. Blunt

B. Cutting

C. Tapered

D. Reverse cutting

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: Supraventricular tachycardia (rate is ~160)

Clinical calculation: 10 drops/minute dopamine infusion

Clinical case: D. PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure)

Medical References (Martyna Abratkiewicz’s picks)

available from North American Rescue

A compact, lightweight and essentially indestructible piece of kit that works, what else could one ask for in the field setting?

New England Journal of Medicine

August 25 2021.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026330

Chandramohan D, et al.We randomly assigned 6861 children 5 to 17 months of age to receive sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine and amodiaquine (2287 children [chemoprevention-alone group]), RTS,S/AS01E (2288 children [vaccine-alone group]), or chemoprevention and RTS,S/AS01E (2286 children [combination group]). Of these, 1965, 1988, and 1967 children in the three groups, respectively, received the first dose of the assigned intervention and were followed for 3 years. Febrile seizure developed in 5 children the day after receipt of the vaccine, but the children recovered and had no sequelae. There were 305 events of uncomplicated clinical malaria per 1000 person-years at risk in the chemoprevention-alone group, 278 events per 1000 person-years in the vaccine-alone group, and 113 events per 1000 person-years in the combination group. The hazard ratio for the protective efficacy of RTS,S/AS01E as compared with chemoprevention was 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84 to 1.01), which excluded the prespecified noninferiority margin of 1.20. The protective efficacy of the combination as compared with chemoprevention alone was 62.8% (95% CI, 58.4 to 66.8) against clinical malaria, 70.5% (95% CI, 41.9 to 85.0) against hospital admission with severe malaria according to the World Health Organization definition, and 72.9% (95% CI, 2.9 to 92.4) against death from malaria. The protective efficacy of the combination as compared with the vaccine alone against these outcomes was 59.6% (95% CI, 54.7 to 64.0), 70.6% (95% CI, 42.3 to 85.0), and 75.3% (95% CI, 12.5 to 93.0), respectively.

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

August 2021.

DOI:https://myemail.constantcontact.com/Your-08-15-2021Journal-of-Special-Operations-Medicine JSOM eNewsletter-ishere-.html?soid=1112660968204&aid=VBEgpmq4WyU

DeSoucy ES, et al.There are limited options available to the combat medic for management of traumatic brain injury (TBI) with impending or ongoing herniation. Current pararescue and Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines prescribe a bolus of 3% or 5% hypertonic saline. However, this fluid bears a tactical burden of weight (~570g) and pack volume (~500cm3). Thus, 23.4% hypertonic saline is an attractive option, because it has a lighter weight (80g) and pack volume (55cm3), and it provides a similar osmotic load per dose. Current literature supports the use of 23.4% hypertonic saline in the management of acute TBI, and evidence indicates that it is safe to administer via peripheral and intraosseous cannulas. Current combat medic TBI treatment algorithms should be updated to include the use of 23.4% hypertonic saline as an alternative to 3% and 5% solutions, given its effectiveness and tactical advantages.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

August 13, 2021.

https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/ticovac

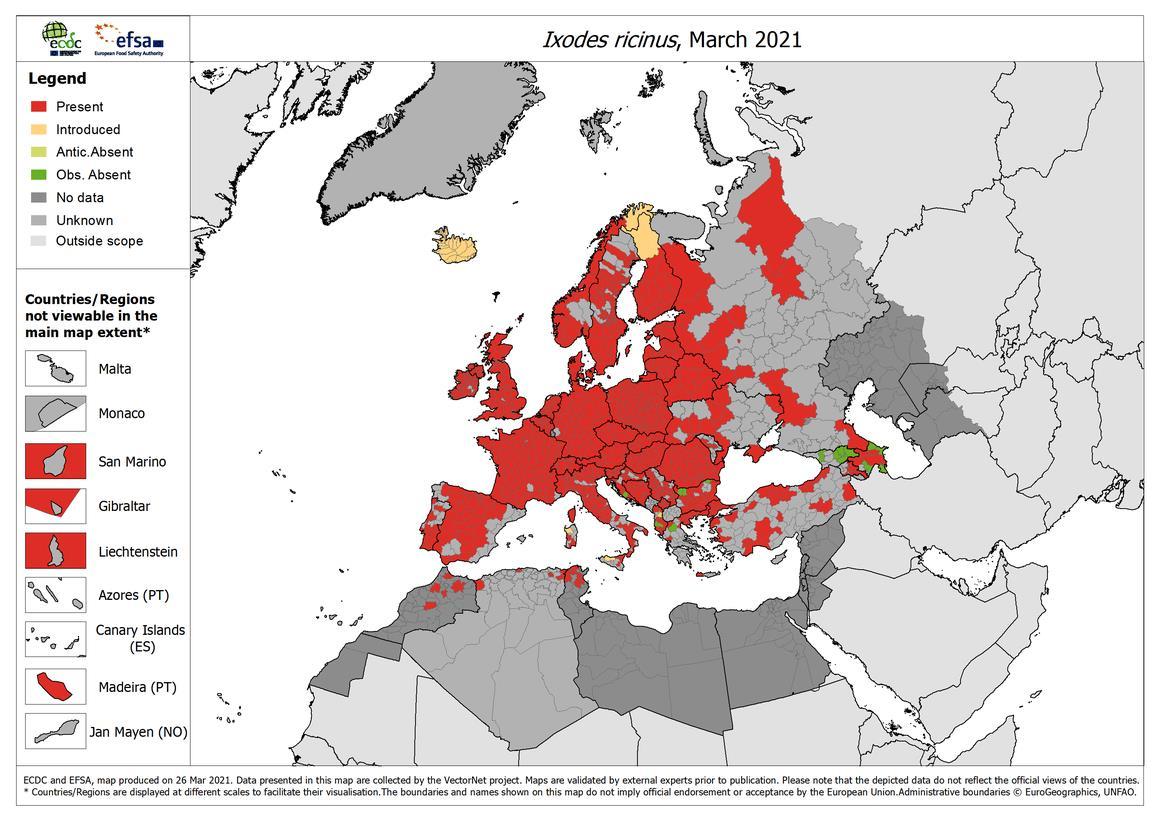

Ixodes ricinus is an important vector of tick-borne encephalitis.

of California Press

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis

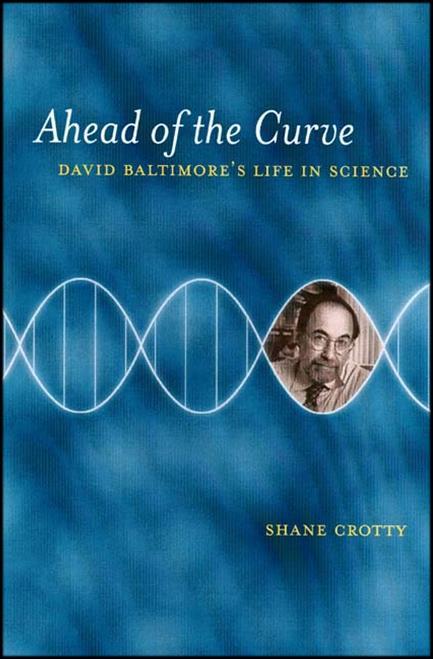

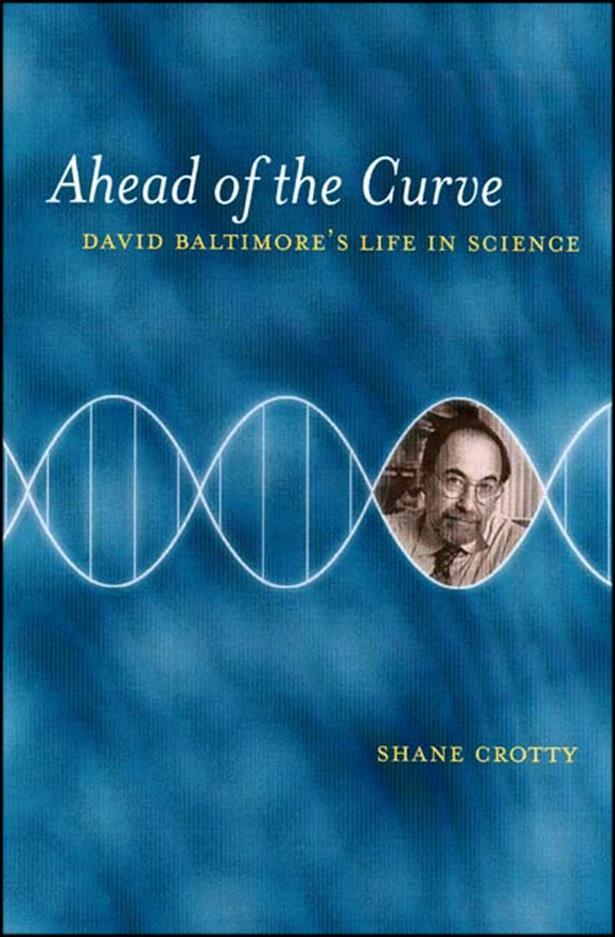

In the age of COVID, the life of Nobel prizewinning virologist David Baltimore is worthy of close examination, which is just what author Shane Crotty accomplishes in Ahead of the Curve

In this larger-than-life biography, Crotty traces Baltimore’s journey as the renowned scientist passes through prestigious institutions like so many towns on a road trip, to include MIT, the Salk Institute, and Rockefeller, just to name a few. David Baltimore is currently President Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Biology at CalTech.

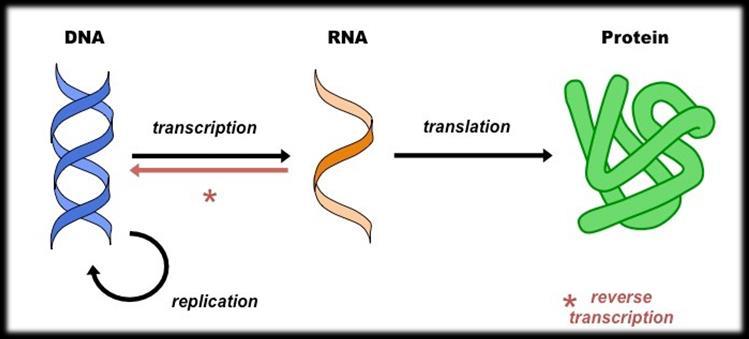

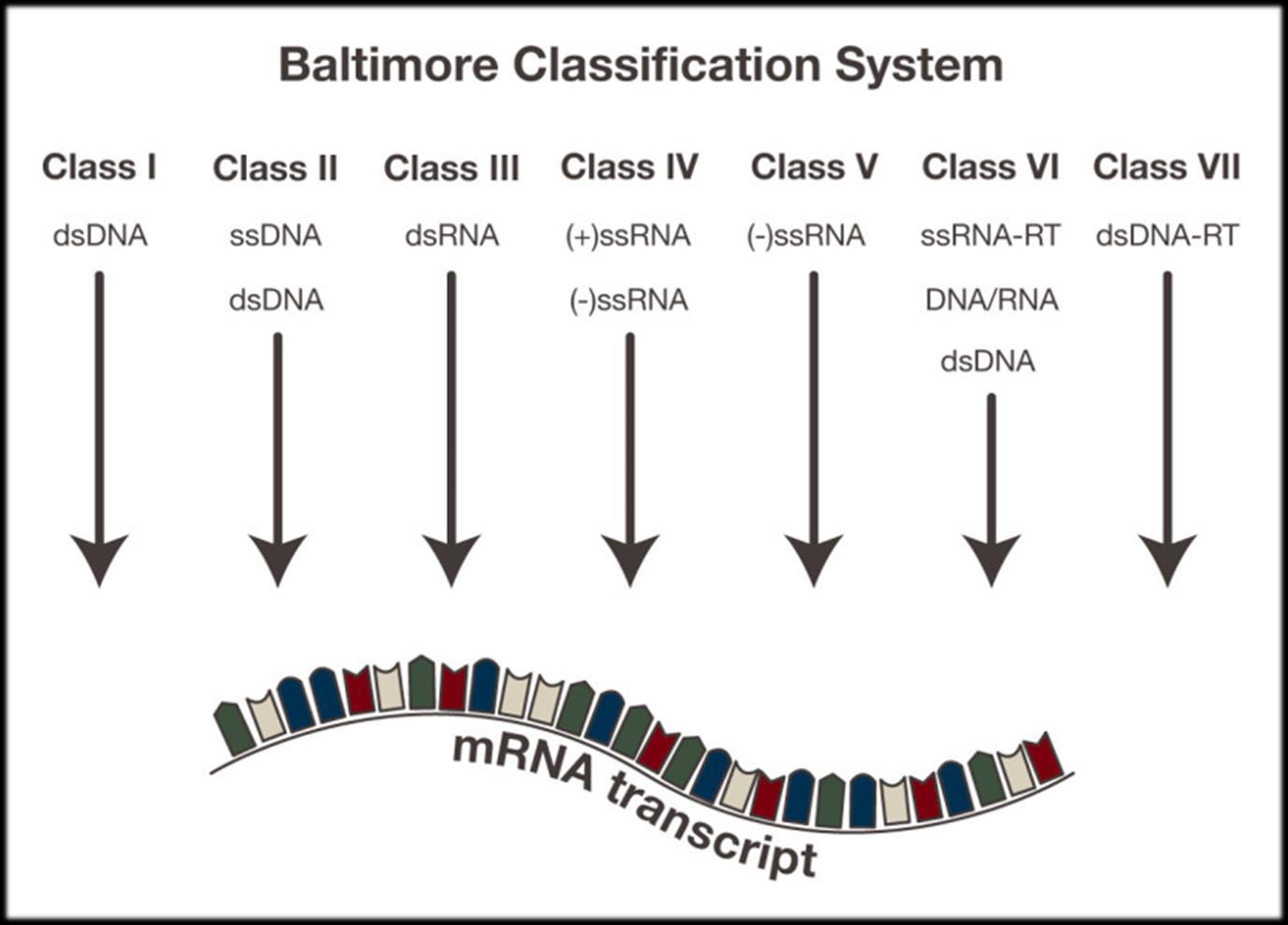

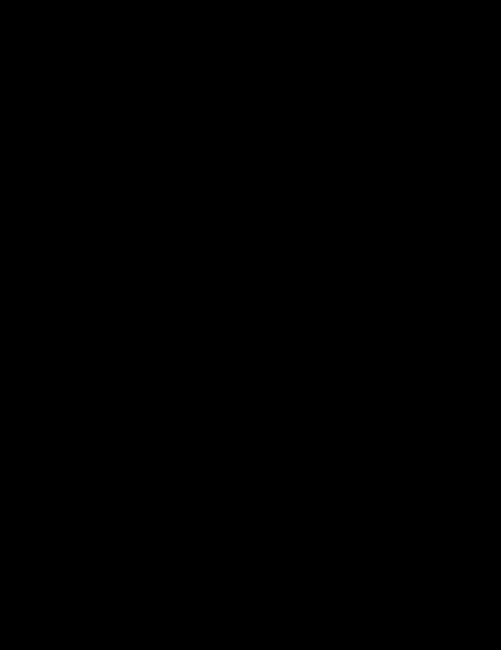

Baltimore won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1975 for his codiscovery of the viral reverse transcription process, but it is his classification of viruses (based on the manner in which they replicate) that first drew my attention to him, courtesy of professor Vincent Racaniello on the This Week in Virology podcast. Baltimore’s viral classification system still bears his name, and is elucidated on the following page.

"A thoroughly researched, vivid, and accessible portrait of one of the towering intellectual figures of our time, David Baltimore: his life, his politics, his driving ambition, his stunning self-confidence.”

-Alan LightmanThe Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. Baltimore won the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the asterisk in this diagram.

Shane Crotty, Ph.D., is a professor at the Centre for Infectious Disease and Vaccine Research at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. His research focus is on understanding the immunobiology underlying vaccine function, with particular interest in the roles of these mechanisms in human viral vaccines and protection from infectious diseases. At University of California, San Francisco he discovered a mechanism of action of the antiviral drug ribavirin, widely used to treat chronic hepatitis C infections. He completed postdoctoral work at the Emory University Vaccine Center with Dr. Rafi Ahmed, studying aspects of the generation and maintenance of immune memory after viral infections.

“Baltimore was plagued by nagging questions about the safety of recombinant DNA. They distracted him from his work and complicated his planning for Asilomar. He would often sit in his office, stroking his beard slowly, and just think. ‘We can always argue that any specific experiment would not be dangerous, and yet when you consider them in aggregate, probably somewhere in there there’s a serious danger, and you don’t know where it is.’ He thought about plasmids, he thought about politics, he thought about viruses, and he thought about how biologists had always been limited by what evolution had created naturally, until now.”

- Ahead of the Curve

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary Academic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

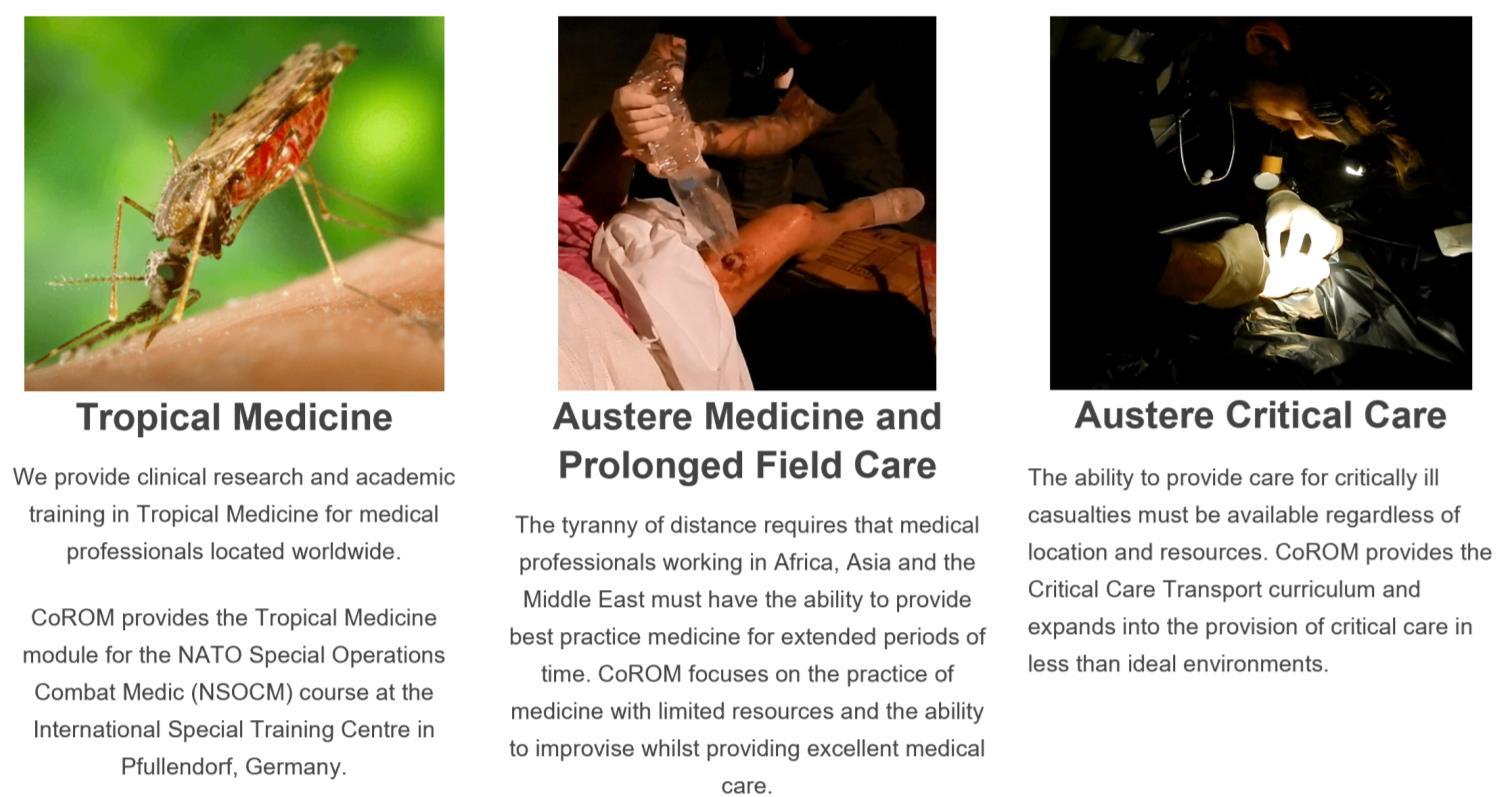

We provide clinical research and academic training in Tropical Medicine for medical professionals located worldwide.

CoROM provides the Tropical Medicine module for the NATO Special Operations Combat Medic (NSOCM) course at the International Special Training Centre in Pfullendorf, Germany.

The tyranny of distance requires that medical professionalsworking in Africa, Asia and the Middle East must have the ability to provide best practice medicine for extended periods of time.

CoROM focuses on the practice of medicine with limited resources and the ability to improvise whilst providing excellent medical care.

The ability to provide care for critically ill casualties must be available regardless of location and resources. CoROM provides Critical Care Transport curriculum and expands into the provision of critical care in less than ideal environments.

NORWAY

TTEMS (closed course) Dates TBD

SWEDEN

TacMed Conference 11-12 October

MALTA

Suturing Fundamentals 23 October

NORTH CAROLINA

SOMSA Conference 2-6 May 2022

Tactical Medicine Review (O’Kelly)

2022 Tropical Medicine Updates (Jarvis)

Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

Higher Diploma Remote Paramedic Practice

PG Cert Austere Critical Care

Diploma of Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme

Altitude

PG Cert Tropical Medicine & Hygiene (in accreditation process)

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Kibosho District Hospital, Kilimanjaro

Ghana National Ambulance Service

ACC Acute critical care

Degree Courses

TANZANIA

Clinical Tropical Medicine Dates TBD

Bachelor of Science Remote Paramedic Practice

MSc Austere Critical Care (in accreditation process)

MSc Leadership in Healthcare (in accreditation process)

Online Courses

Critical Care Transport

Aeromedical Retrieval Medicine for Extreme Altitudes

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support

ATTEMS Advanced Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

ITLS International Trauma Life Support

PALS Paediatric Advanced Life Support

PARSIC Prehospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction course

PG Cert Postgraduate certificate

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

RPP104 Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice (classroom learning)

SOMSA Special Operations Medical Association Scientific Assembly

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

EMS drug cards

Calculators

Snakes & arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS

Paediatric diseases

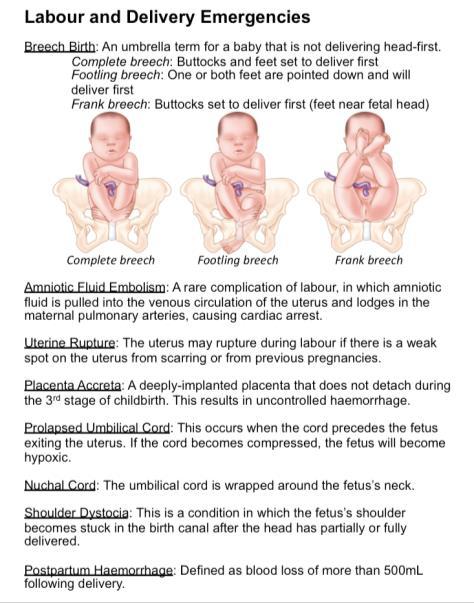

OB/Gyn

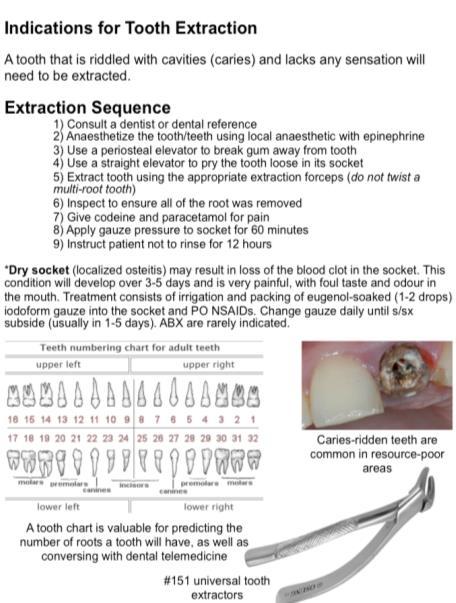

Dentistry

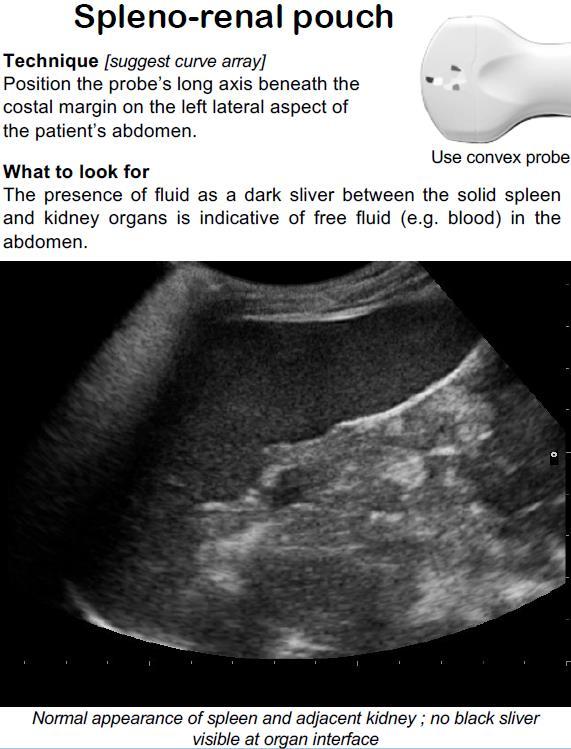

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

Canine medicine

…and much more!