Theofficialnewsletterofthe CollegeofRemoteandOffshoreMedicine Foundation

2019

Autumn

CONTENTS PAGE About CoROM 3 Dean’s Desk 4 Message from the Academic Board 5 Photo Gallery 6 Course Calendar 7 Where Are They Now? 8 Dr. Bethan McDonald on her adventures following the TTEMS and RAMS Faculty Spotlight 9 Q &Awith Lara Christy Case Report 11 Rash and eschar acquired in SouthAfrica with Dr. Michael Shertz Public Health 12 Nicole Foster on the Ebola virus outbreak in DRC Trends in Traumatology 15 Jason Jarvis on freeze-dried plasma Selected Product Information for Bioplasma FDP 16 Continuing Education 17 Neil Coleman on recognition of death Test Yourself 18 ECG, drug calculation, and clinical case Resources 19 Aselection of medical references and gear Journal Watch 20 Human Responses to 5 Heated Hypothermia Wrap Systems Visceral and Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a City in Syria Does Oral or Topical TranexamicAcid Control Bleeding From Epistaxis? Exertional Heat Stroke: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Dx, Tx, and Prevention Book Review 22 Blood

Douglas Starr

by

Autumn 2019 2

Cover photo: CoROM alumnus Dr. Keith Winterkorn teaching ultrasound at the TTEMS course in Tanzania

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntaryAcademic Board supported by a faculty of medical professionals from four continents. The College is registered with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta and is a degree granting educational institution.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and resource-poor environments.

What does CoROM specialise in?

About CoROM 3

Dean’s Desk

The College has been busy over the summer. We ran our second annual Remote Paramedic course at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College in Moshi, Tanzania. It is always a high point in my calendar to return to the base of that majestic mountain.

This trip to Tanzania included an official signing of an agreement with Kilimanjaro Search and Rescue (SAR). The College can now offer hands-on clinical experience on their helicopters, and we will be sending paramedics, nurses and doctors with flight or critical care experience. This collaboration is beneficial for both the College and for the Kilimanjaro SAR, as our delegates will be working with their staff to provide world class prehospital care for hikers, rangers and porter who get injured on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Whilst at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) this summer, the College donated anALS manikin, an iPad-basedALS monitor and some supplies for their Emergency Department. We continue to provide financial support and medical donations for the KCMC staff.

The College also provided clinical oversight for Ternopil State Medical University on their ITLS instructor course. We will continue to support TSMU as they become the first ITLS training centre in Ukraine.

It has been a busy few months for the College but there is no rest in sight. We have eleven delegates enrolled in our Higher Diploma of Remote Paramedic Practice, and are revamping that programme to include a third and fourth year that will culminate in the BSc and the BSc(hon) awards.

We look forward to a busy 2019-2020 academic school year.

4

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E MA FAWM DipPara CCP-C TP-C

CoROM Education Manager Neil Coleman (first on left) and ITLS training faculty at Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

Message From the Academic Board

Greetings,

It is with great honor that I am writing this piece in this edition of the Compass. It is the duty of the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine (CoROM) academic board members that past, present and future students get a glimpse of how the College operates.As the name of this newsletter – the Compass – implies, we are committed as a team to show the right direction to all those who join the College to pursue higher education in the various aspects of austere medicine.

Dr. Francis Sakita MD, MMED Emergency Physician Head of ED-KCMC CoROM Faculty

Dr. Francis Sakita MD, MMED Emergency Physician Head of ED-KCMC CoROM Faculty

The diversity and uniqueness of the College’s faculty makes it stand out from the crowd. It is among the few colleges that offer expedition medicine and remote paramedic courses; just recently, CoROM was accredited to award the bachelor’s degree in Remote Paramedic Practice. This is the result of our “A team” working tirelessly to achieve this, and is undoubtedly a great milestone in the development of the College. Many plans for expansion of CoROM’s core curricula are in the works, and now only the sky is the limit.

What makes working with CoROM so interesting is the inclusion of students of various calibers (physicians, nurses, paramedics, and EMTs) from different parts of the world and all with a thirst for knowledge and skills.Alongside the teaching, a broad network is generated which not only facilitates the learning process but opens doors for opportunities to explore.

The high quality education that CoROM offers is extremely versatile and enables the student to ignite the spark of searching for even more knowledge and acquiring new skills. Learning is both a continuous and cumulative process; therefore it is our great hope that your experience with us in the College opens more doors of opportunity ahead, both academically and professionally. I recall a quote by the late Nelson Mandela: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” It is our great hope that after completing courses with us, you will be the change agent wherever you are.

We have memorandums of understanding with hospitals around the globe for our students who wish to have clinical interaction with patients. Under close supervision, students develop confidence while improving their skills and abilities to make clinical decisions. The College facilitates these clinical placements in order to benefit its students as well as the placement hospitals.

I would like to thank you for choosing CoROM. The faith you put in us energizes us to work hard to provide superb remote and offshore medical training to you or your institution. Until next time, see you in Malta!

Dr. Francis Sakita is the first Emergency Physician at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center, which caters to a population of 15 million Tanzanians. He is also a lecturer and instructor at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College and CoROM, respectively. He enjoys teaching, treating patients, and research. Dr. Sakita has published several papers on various topics in Emergency Medicine in Sub Saharan Africa. He is passionate about expanding Emergency Medicine in Tanzania and Africa at large.

5

Photo Gallery

Students discuss the priority of care during a mass casualty exercise at the TTEMS course in Tanzania

CoROM Education Manager Neil Coleman teaching ITLS at Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine

CoROM donated €4000 worth of medical training equipment to Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center

Measuring the zone of inhibition around trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in Müller-Hinton agar at KCMC, Tanzania

Gear issue at the Remote EMT course in Malta

TTEMS students ventilating the iGel supraglottic airway using a SAV ventilator

6

Course Calendar

RALEIGH,

NORTH CAROLINA

Special Operations Medical Association Scientific

Assembly 11-15 May 2020

Tactical Medicine Review with IBSC exams

Malaria workshop

MALTA

CC-P 14-18 October

Remote EMT 18-23 November

RMLS 11-13 March, 2020

eITLS 22 March, 2020

FiCC 6-12 April 2020

TTEMS 23-27 March, 2020

eITLS 15 November, 2020

TTEMS 16-20 November, 2020

RAMS 30 November-4 Dec 2020

SEATTLE

Suturing Fundamentals 24 October 14 January, 2020

GERMANY NSOCM TTEMS 18-22 May, 2020 (closed course)

LEGEND

CC-P International Critical Care Paramedic (IBSC)

TANZANIA

TTEMS 3-7 August, 2020

eITLS International Trauma Life Support Completer Course (follows ITLS eTrauma course)

FiCC Foundations in Critical Care (RPP203)

IBSC International Board of Specialty Certifications

NSOCM NATO Special Operations Combat Medic course

RAMS Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS Tropical, Travel and Expeditionary Medical Skills

Advanced Certificate and Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Clinical Placements

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC), Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Level 3 Health and Safety for the Workplace

Level 3 Food Safety for the Workplace

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org. Please address newsletter correspondence to editor@corom.org.

7

Where Are They Now?

Dr. Bethan McDonald on her adventures following the TTEMS and RAMS courses

I completed the TTEMS and RAMS courses last December in Malta, hoping to complete the last step in obtaining my FAWM qualification. After taking some post-course time-out to explore the gorgeous Gozo coastline and go for a SCUBA dive I had to get back to the real world: working in Australia in general practice (family medicine) and doing travel consultations to prep people for their adventures, work trips and international postings.

I’m always on the look out for opportunities to work in wilderness and expedition jobs so I jumped at the chance to support a film crew making a documentary about tiger sharks for the Discovery Channel’s Shark Week. With less than 7 days notice, I headed off for the coast of Norfolk Island in the Pacific Ocean with tourniquet in hand while our crew navigated waters teeming with dozens of apex predators. Such a great chance to see some beautiful animals in a pristine environment! Thankfully we finished the 17-day shoot with everyone still having four limbs. (For you U.S.-based folk, the documentary was released on 29th July).

I should still have a bit of excitement on the horizon. I’ll be working in Laos, supporting Australian embassy staff for a couple of weeks in September and, closer to home, have just joined volunteer ski patrol, caring for the cross-country skiing community during our winter.

8

Dr. Bethan McDonald MBBS FRAGCP DipPaed DTM&H DiMM FAWM

Dr. Bethan McDonald off the coast of Norfolk Island

Faculty Spotlight

Q andAwith Lara Christy

Lara had an introduction to her career in medicine in 1994 with an Emergency Medical Technician Basic course. She then completed a wilderness EMT upgrade and a Master’s in Experiential Education in 1996. She worked as a wilderness therapist with at-risk youth, and later returned to school for a Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing. Lara then worked for 10 years in various intensive care units and a Level 1 trauma emergency department in Saint Louis, Missouri. During that time, she completed her Master’s of Science in Nursing and became an Adult Nurse Practitioner. She moved to North Carolina, where she lives in the Smoky Mountains, and is an avid whitewater kayaker, trail runner, and backpacker. She works as a nurse practitioner in Cardiology, and enjoys teaching as well. She has taught wilderness medicine for several years, and recently earned her Fellow of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM). Lara joined CoROM faculty in April 2019.

What aspect of CoROM motivated you to join the College?

I met Aebhric O’Kelly at a Wilderness Medical Society conference, and we discovered that we had similar backgrounds and goals. When he invited me to come to Malta as a guest lecturer, I was both excited and honored. CoROM has faculty from very diverse backgrounds, and that creates a rich learning environment. The College has worked hard at developing learning sites that provide a variety of remote and austere settings. One thing that excites me about medicine is that I never stop learning. With CoROM I am challenged, and that makes teaching fun.

What is your favorite teaching topic at CoROM?

I enjoy teaching altitude illness recognition, treatment and prevention. The complex pathophysiology of altitude is fun to explain, and draws upon my critical care and cardiology background. Since I live in the mountains and enjoy all things that are wild, I also enjoy teaching others how to enjoy the wilderness safely. Prevention and early recognition is key to surviving altitude illnesses, which is true in most of medicine. By giving others the tools, we can save lives.

Lara Christy MSN, ANP-BC, FAWM, CCRN, CEN, TNCC CoROM Faculty

Lara Christy MSN, ANP-BC, FAWM, CCRN, CEN, TNCC CoROM Faculty

9

Lara Christy navigating Wilson Creek’s Razorback Rapids in North Carolina

Where would you like to see CoROM go in the next five years?

I am really impressed by the depth of knowledge in the CoROM faculty, covering military settings, remote/austere environments, and different climate challenges across the globe, as with tropical medicine and altitude. I would love to see CoROM continuing to train medical professionals in different countries and improve their knowledge base so that quality of life can be improved globally. I feel very fortunate to have trained in one of the premier academic facilities in the United States, at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in Saint Louis, and I would love to expand upon the great work that CoROM is already doing in other countries through education and outreach.

Describe a medical case that has had a lasting impact on you.

My undergraduate studies were in New Orleans, Louisiana in the early 1990s, at the height of HIV/AIDS in the United States, so I was emotionally impacted by the epidemic. Later while in Saint Louis, working in the intensive care unit, I had a patient afflicted with end-stage AIDS. His domestic partner had been fortunate enough to be accepted into a research study with experimental medications that were effective, but my patient was not in the study, and had not been on anti-retroviral medication. The stark difference in their health was shocking. I worked with this patient and his loved ones for weeks before he died on my shift. He was able to have a dignified death, and I was able to support his loved ones. In medicine, sometimes we cannot save lives, but we can still provide dignity and a loving environment. I’ll never forget this case, and will continue to fight to help others gain access to the care and medications that they need.

What are your top three go-to references for remote deployments?

I like the pocket-sized Comprehensive Guide to Wilderness and Travel Medicine by Dr. Eric Weiss because it has a wealth of knowledge in a compact size.Another weight/volume-friendly comprehensive guide is the NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School) Wilderness Medicine Pocket Guide. And I was quite impressed by the CoROM Field Guide as well, not only because of the size and weight, but also because of the wide variety of pertinent topics. Of course, I tailor my references based on where I’m going, and would consider adding the small but heavier Oxford Guide to Tropical Medicine if going to a tropical region.

10

Lara Christy trail running in Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Case Report

Rash and eschar acquired in SouthAfrica with Dr. Michael Shertz

Mike Shertz, 18D/MD, DTM&H is a former U.S. Army Special Forces medic, board certified Emergency Physician who also has a diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He works in Portland, Oregon but travels in the developing world whenever possible. He also offers TECC/TCCC courses online at www.crisis-medicine.com.

Dr. Michael Shertz 18D/MD, DTM&H

A47 year old male presents to the Emergency Department with an “abscess” on his back. He returned from 12 days hunting in SouthAfrica one-week prior. He noted tenderness inferior to his scapula during the return trip and identified redness and a “pustule” when he looked in the mirror.

Review of Symptoms: Mild myalgias, arthralgias and feeling “flu-ish”, but denies definite fevers, nvd, cough, sob, cp, or abd pain. He is completing his Malarone course post travel and was fully vaccinated for travel toAfrica.

He is afebrile with a lacy, erythematous, blanching rash on his back. There is a 3-5mm black, oval eschar inferior to the scapula with surrounding erythema and induration. He has unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy.

Differential for a rash and feeling “flui-sh” post travel to Africa includes malaria, typhoid, rickettsial infection, and dengue. Differential for an eschar includes myiasis, rickettsial infection, cutaneous anthrax, and Loxosceles spider envenomation.

Presumptive Diagnosis: African Tick Bite Fever

Treatment: Doxycycline 100mg PO bid for ten days

Causative Organism: Rickettsia africae transmitted by the bite of Amblyomma genus ticks

Geographic Distribution: Sub-Saharan Africa, similar species in Caribbean, North, and SouthAmerica

The incubation period is 5 to 7 days and it is a milder illness than Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

Fatalities are rare. Similar to Mediterranean Spotted Fever (R. conorii), but generally much less severe.

Up to 80% of host ticks are infected compared to only 1 in 1000 for RMSF. The majority of patients present with fever (59 – 100%), headache (62 – 83%), rash (15 – 46%) and eschar (53 – 100%). Multiple eschars can be present (21 – 54%).

Serology is available to confirm the diagnosis, but history and presence of an eschar is classic. See the Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses chapter in Tropical Infectious Disease, 2nd edition for further discussion.

11

A 47-year-old male with a 3-5mm black, oval eschar inferior to the scapula with surrounding erythema and induration

Public Health

Nicole Foster on the Ebola virus outbreak in DRC

DRC EBOLA OUTBREAK NOW DECLARED APUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY OF INTERNATIONAL CONCERN

Background:

The North Kivu province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) declared an Ebola outbreak on 1August 2018.As of 25 July 2019, there has been 2518 confirmed and 94 probable cases, of which 1756 cases died (overall case fatality rate 67%).1

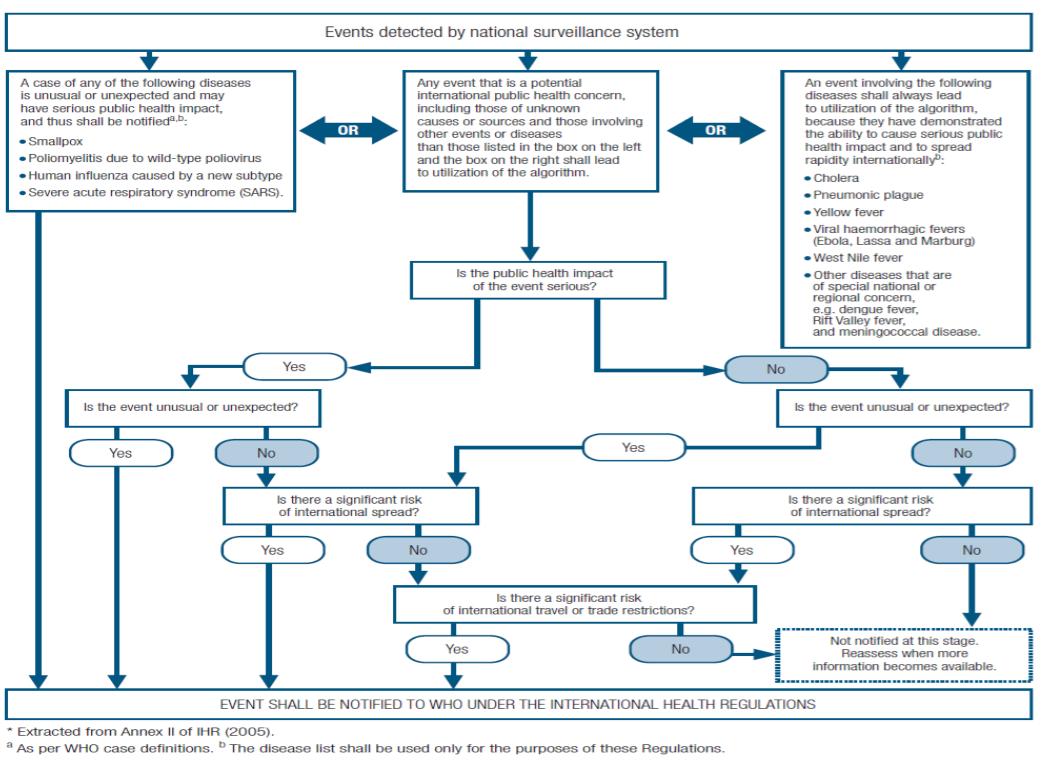

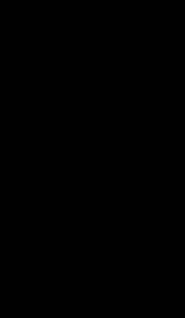

On 17 July 2019, the WHO Director-General convened the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (IHR) to review the situation on the Ebola outbreak in the DRC. Due to the geographic location and porous borders of the DRC, and the confirmed case and death of a patient in Goma (a border city and key economic access point between Rwanda and DRC) and three confirmed cases in Uganda, it was decided to declare the Ebola outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).1

The IHR and public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC)

The International Health Regulations (2005) were adopted by the World Health Assembly in 1969 and have modified several times since, with its purpose “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.”2

The term Public Health Emergency of International Concern is defined in the IHR (2005) as “an extraordinary event which is determined: to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease; and to potentially require a coordinated international response.”2

APHEIC is the highest formal declaration by the WHO and allows for temporary recommendations that can include release of emergency funding, in addition to deployment of resources and personnel. The declaration is reviewed every three months and ensures that the international response is immediate. The decision instrument used to determine a PHEIC is below.2

To date, there have been five PHEIC declarations:

2009: H1N1 Swine flu virus

2014: Wild Polio virus

2014-2016: Ebola virus

2016: Zika virus

2018 – 2019: Ebola virus3

12

Nicole Foster BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

What is Ebola?

Family: Negative stranded RNAFiloviridae virus (includes Cueva, Marburg and Ebola)

Genus: Ebolavirus

Species: Zaire, Bundibugyo, Sudan, Taï Forest, Reston and Bombali. (Zaire is responsible for almost all of the Ebola outbreaks).

Reservoir: Fruit bat (Pteropus scapulatus, et al).

Transmission: Animal to human, human to human. (Fruit bat saliva, droppings -> chimpanzees, gorillas, duikers or other bush meat -> human).

How?: Direct contact (broken skin or mucus membranes) through body fluid, secretions or fomites that have been in contact with body fluid or secretions.

Incubation period: 2- 21 days (average 8-10 days).

Signs and Symptoms:

1st phase

Febrile stage <3 days (Quick onset). S/sx: fever, fatigue, conjunctivitis, rash, headache, sore throat.

2nd phase: GI stage 3

10 days. S/sx: 1st phase s/sx, plus N/V, diarrhoea, abdominal pain.

3rd phase: Complicated stage (CNS, organ failure) 7

12 days. S/sx: 1/2nd phase s/sx, plus conjunctival and mucosal haemorrhage, petechiae, gastrointestinal bleeding, confusion, delirium, seizure, coma, death.4

13

A

three-dimensional model of the Ebolavirus

Figure 1: Flowchart for decision-making on a PHEIC

–

–

–

Diagnosis is through the collection of whole blood from live patients, or oral secretions in deceased patients. Testing can include; Rapid Antigen Tests (OraQuick Ebola) for large population screening purposes, followed by Automated or semi-automated nucleic acid tests (NAT)3 .

Treatment: Rehydration, supportive symptomatic care and isolation. Contact tracing and ring strategy vaccinations are slowly stabilising the intensity of the outbreak, but not the geological spread.3

Prevention: 4 new vaccines have been developed since the 2014-2016 outbreak and are currently being trialed. Vaccine demand is high, leading to a undersupply in some areas. Local engagement, consultation and education is the most important preventive measure and must align with the cultural practices and traditional values of its population. More than 170,000 people have been vaccinated, including 34,000 health workers, volunteers, and contact tracers.1

What are the issues? Ebola is not the most deadliest disease outbreak in the DRC this year. You can call it the straw that broke the camel’s back – this year to date, there has been over 100,000 measles cases in 23 of the country’s 26 provinces, resulting in more than 2,000 deaths. This is a 700% increase from previous years. Suspected cholera cases are estimated to be above 13,400, resulting in vaccination of over 1.2 million people, and an estimated 266 deaths. In seven provinces, there has been five outbreaks of circulating vaccine derived poliovirus.5

All of this is occurring in a country that has been in some form of internal conflict or war for the past twenty years. There simply is not the security, health infrastructure and system in place to cope with these outbreaks and attain the required vaccination rates in its population. There is an inherent mistrust of western medicine and health care workers (both local and international), which has led to conspiracy theories about the vaccines – the most popular being health workers are injecting the local people with deadly substances at treatment centres and vaccination sites. This has led to over 200 attacks on health care workers and treatment posts, with five deaths, 58 injuries and several treatment centres burned to the ground by local groups.1 It is also hampering efforts to treat potential Ebola patients and allowing Ebola to spread as people are scared to receive vaccinations or attend treatment clinics and are choosing to receive home care or are hiding, spreading the disease to family members due to the lack of precaution and traditional burial practices. Declaring a PHEIC is going to inject much needed funds and resources into the DRC to assist with the cessation of the spread of Ebola. But until the DRC internal insecurities are stabilised to level where infrastructure is built and maintained, vaccination rates are increased and trust are built within the local communities, there is a chance that this public health emergency lingers for a long time.

References

1. Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 17 July 2019 [press release]. 2019.

2. Organisation WH. Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations (2005). https://www.who.int/ihr/publications/9789241580496/en/. Published 2019. Accessed.

3. Organisation WH. Ebola virus disease. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebolavirus-disease. Published 2019.Accessed.

4. Malvy D, McElroy AK, de Clerck H, Günther S, van Griensven J. Ebola virus disease. The Lancet. 2019;393(10174):936-948.

5. Berkley S. The real public health emergency of international concern: the DRC. https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/25/ebola-real-public-health-emergency-drc/. Published 2019. Accessed.

14

Cutaway schematic of the Ebolavirus

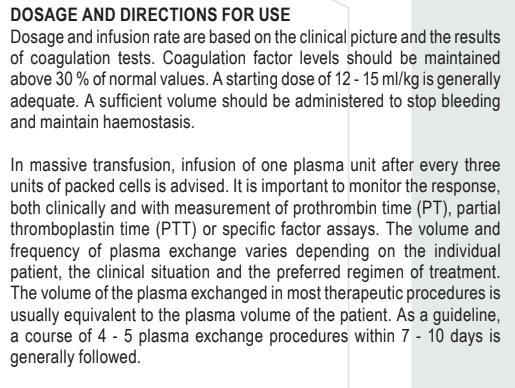

Trends in Traumatology

Jason Jarvis on freeze-dried plasma

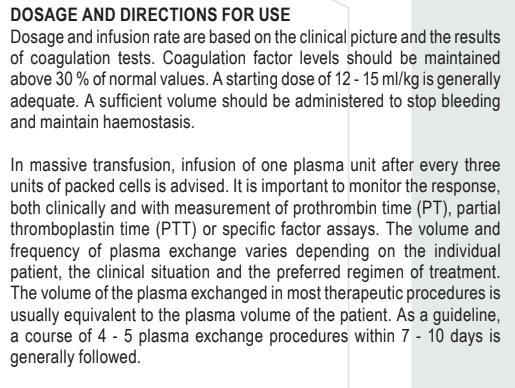

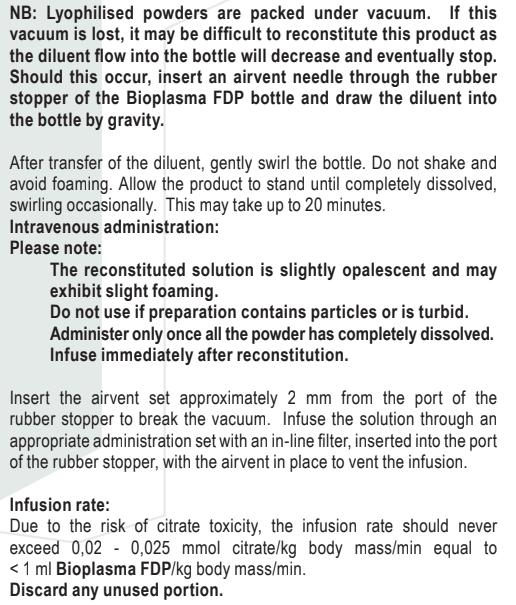

Transfusion of blood products in the field setting can be a challenging but not insurmountable endeavor. Without access to an electric grid, the use of whole blood requires either transfusion “on the hoof” (buddy transfusion) or the added burden of maintaining a mobile cold chain in which to store recently harvested blood.

Fresh frozen plasma presents a similar dilemma with respect to the cold chain, but with a -18°C temperature requirement.

During World War II, the British and Americans embraced the recentlydeveloped technology of freeze-dried plasma (FDP) and began massproducing it on a scale that would have made Henry Ford envious. FDP was shelf-stable withABO universality, and could be quickly reconstituted with sterile water by field medics and administered to casualties in virtually any setting. As an alternative to whole blood, it was wildly successful and continued to be used by the U.S. during the Korean conflict and by the French in the Indochina War. Later in the 20th century, as the scourge of hepatitis waxed among both donors and recipients of plasma, the technology was abandoned by its users; the U.S. FDA withdrew FDP from civilian use in 1968, a decision that still stands.

Following a long hiatus – and the development of pathogen-removing technology

FDP production resumed in the 1990s and continues in France (FLyP), SouthAfrica (Bioplasma FDP), and Germany (LyoPlas Nw).

In 2012, facing similar challenges as their World War II predecessors (hemorrhaging casualties in far-forward environments), U.S.Army Special Forces medics received approval to use FLyP during combat operations, with select U.S. Marine Special Operations Command corpsmen following suit in 2016. On 10 July 2018, the FDAgranted Emergency UseAuthorization for the use of FLyP for the U.S. Department of Defense as a whole. Anumber of U.S. companies are developing FDP, with an estimated product to market date of 2019-2020.

As of this writing, the U.S. Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) includes the use of FDP in their fluid resuscitation protocols:https://www.deployedmedicine.com/market/11/content/40

LyoPlas N-w is produced by the German Red Cross. Unlike the French and South African FDP, the German product is ABO type specific and derived from a single donor.

–

15

Jason Jarvis 18D BSc NREMT-P TP-C CoROM Tropical Medicine Lead The Compass editor

French lyophilized (freeze-dried) plasma (FLyP)

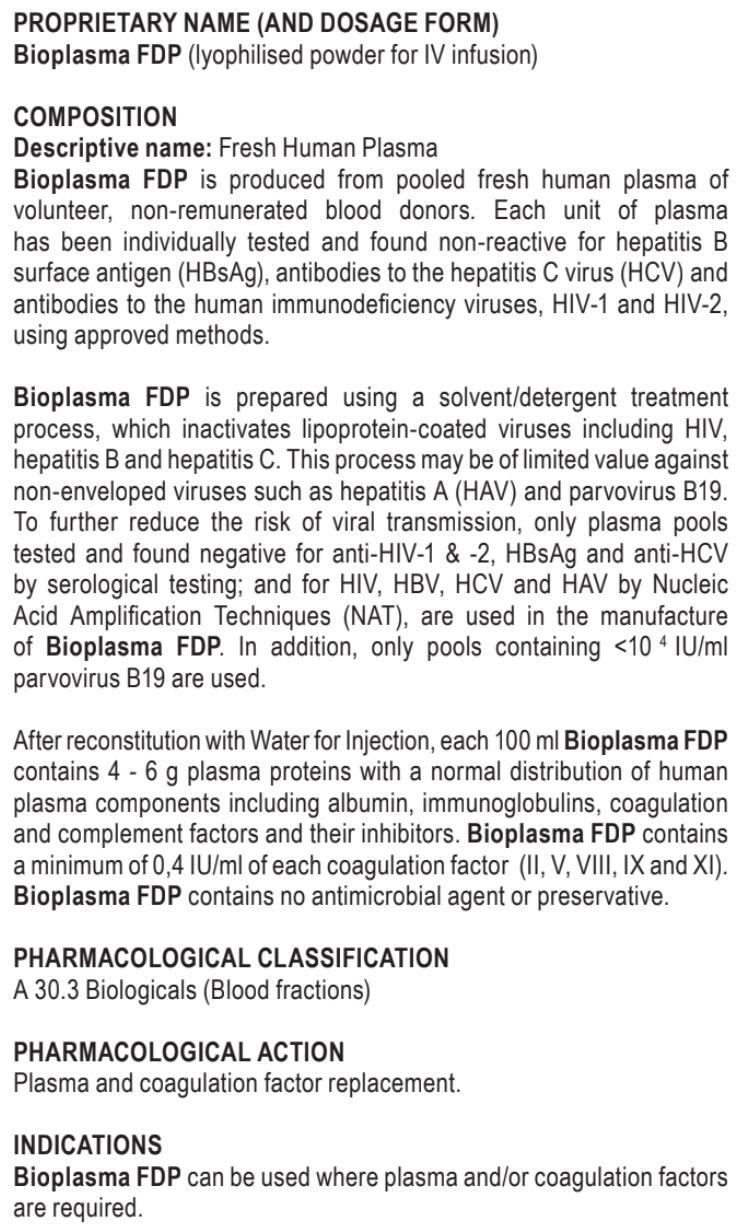

16

Bioplasma FDP(freeze-dried plasma)

Selected Product Information for

Continuing Education

Neil Coleman on recognition of death

While recognising that someone has died may seem like an all too obvious skill for a paramedic, there are issues surrounding the topic that are possibly worth considering.

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Education Manager

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Education Manager

There is usually a protocol-driven system for dealing with patients who are clearly deceased, and those who are in “workable” cardiac arrests. While this is not an article on procedures for running an arrest (or a “code” as it’s sometimes called), the remote practitioner should be aware of the differences.

As a minimum, end of life checks should be included in the repertoire (excluding obvious death such as decomposition or rigor mortis, etc), that would include two separate ECG rhythm strips being printed, assessing the patient for breath sounds, response to painful stimuli and pupillary reaction. Most systems/employers will have a protocol in place for this, so check it.

Other considerations are the cultural factors of a loved one passing. These will vary greatly from area to area, so as a remote practitioner try to familiarise yourself in advance of what the customs are when a patient passes. Remember that the people around you may have just lost a cherished family member, so when anger manifests, it is rarely meant to be directed at you but unfortunately sometimes will be.

17

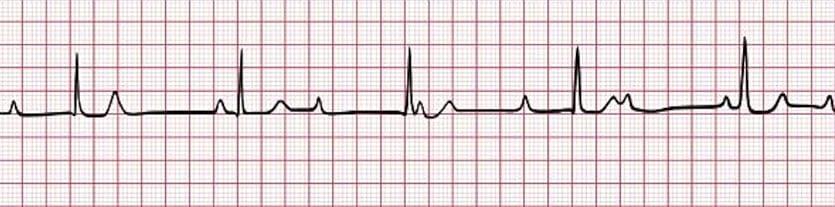

Test Yourself

ECG

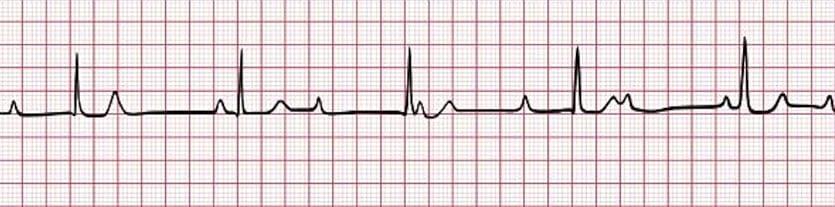

You interpret this ECG as a:

A. Wandering atrial pacemaker

B. Complete heart block

C. Wenckebach

D. Mobitz II

Drug Calculation

As part of a medical team conducting a tsunami relief effort in southern Myanmar, you have been treating an outbreak of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus bacteria. Most patients have responded well to aggressive surgical debridement and antimicrobial therapy. Your antibiotic of choice has been cefotaxime but you have just run out and are now preparing to administer imipenem/cilastatin (Primaxin) 1000mg IV over 60 minutes to your next patient. The total fluid volume of the drug is 200mL, and you are using a 15 drop/mLIV giving set.At how many drops per minute should you infuse the Primaxin?

Clinical Case

While working for Médicins Sans Frontières inAngola, you receive a patient who was recently treated for Plasmodium ovale malaria by a local teaching hospital.Antimalarials prescribed were artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) and primaquine. The patient is now complaining of abdominal pain, headache, nausea, vomiting, and scant dark urine (specimen pictured below). The most likely cause of this syndrome is:

A. Phenylketonuria

B. Addison’s disease

C. G6PD deficiency

D. Co-infection with Trichinella spiralis

Answers will appear in the Winter edition of The Compass.

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG: Hypocalcemia (prolonged QT interval)

Drug calculation: Yes, you have 25 minutes’ worth of procainamide infusion

Clinical case: Vitamin A deficiency

18

Resources

Aselection of medical references and gear

Medical References (Lara Christy’s picks)

Gear IQ Butterfly Portable Ultrasound available at https://www.butterflynetwork.com/

Specs

Dimensions

185x56x35mm

Weight

313g

Battery life

2 hours

Compatibility iPhone, iPad, Pro,Air

Modes M, B, Color Doppler

Min/max scan depth 2cm/30cm

Presets

Abd, cardiac, OB, nerve, etc.

19

Journal Watch

Human Responses to 5 Heated Hypothermia Wrap Systems in a Cold Environment

Wilderness and Environmental Medicine

2019; 30(2): 163-76.

Ramesh

Dutta, et al.

CONCLUSION

The user-assembled and Doctor Down systems were most effective, and subjects were coldest with the HPMK system. However, it is likely that any of the tested systems would be viable options for wilderness responders, and the choice would depend on considerations of cost; volume, as it relates to available space; and weight, as it relates to ability to carry or transport the system to the patient.

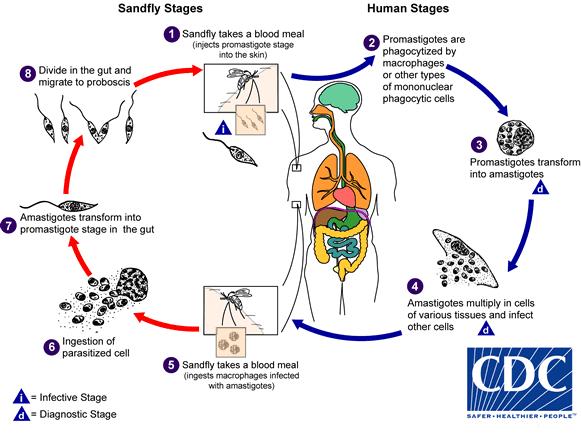

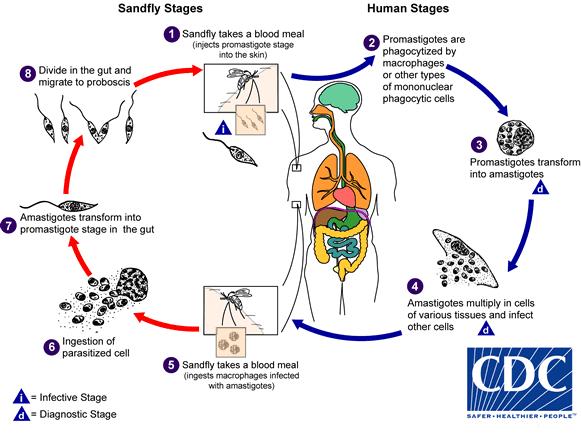

Visceral and Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a City in Syria and the Effects of the Syrian Conflict

The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

101(1), 2019, pp. 108-112. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0778.

Alexey Youssef, et al.

ABSTRACT

War provides ideal grounds for the outbreak of infectious diseases, and the Syrian war is not an exception to this rule. Following the civil crisis, Syria and refugee camps of neighboring countries witnessed an outbreak of leishmaniasis. We accessed the database of the central leishmaniasis registry in Latakia city and obtained the leishmaniasis data of the period 2008-2016. Our data showed that the years 2013 and 2014 recorded a surge in the number of both cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) cases. This surge coincided with the massive internal displacement waves that struck Latakia governorate during that time. Subsequently, after 2015, the number of recorded CL and VL cases gradually decreased. This drop coincided with a reduced influx of internally displaced persons into Latakia governorate. Our report depicts the effects of the Syrian crisis on the epidemiology of leishmaniasis by outlining the experience of Latakia governorate. Similar results may have occurred in other refugee-hosting Syria governorates.

20

The Doctor Down hypothermia system was one of the most effective products in the study, with “higher skin temperatures and lower metabolic heat production.”

Journal Watch

Does Oral or Topical TranexamicAcid Control Bleeding From Epistaxis?

Annals of Emergency Medicine. August 2019, Volume 74, Issue 2, Pages 300-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.01.042.

Rachel E. Bridwell, MD; Michael D. April, MD; Brit Long, MD.

Rachel E. Bridwell, MD; Michael D. April, MD; Brit Long, MD.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Compared with usual care, either oral or topical tranexamic acid reduces the risk of rebleeding within 7 to 10 days among adults with epistaxis. Ahigher proportion of patients demonstrate bleeding cessation within 10 minutes with topical tranexamic acid compared with other topical hemostatic agents.

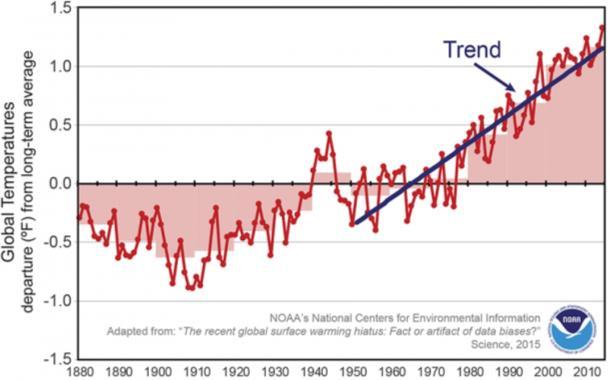

Exertional Heat Stroke: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

Journal of Special Operations Medicine. Summer 2019.

https://www.jsomonline.org/AllArticles.php#Article922.

ABSTRACT

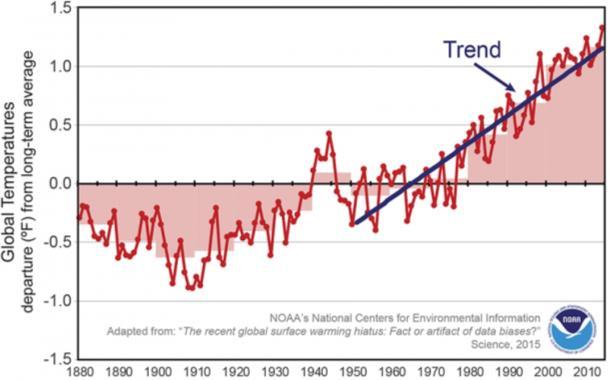

Temperature increases due to climate changes and operations expected to be conducted in hot environments make heatrelated injuries a major medical concern for the military. The most serious of heat-related injuries is exertional heat stroke (EHS). EHS generally occurs when a healthy individual performs physical activity in hot environments and the balance between body heat production and heat dissipation is upset resulting in excessive body heat storage. Blood flow to the skin is increased to assist in dissipating heat while gut blood flow is considerably reduced, and this increases the permeability of the gastrointestinal mucosa. Toxic materials from gut bacteria leak through the gastrointestinal mucosa into the central circulation triggering an inflammatory response, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), multiorgan failure, and vascular collapse…the cornerstone of EHS diagnosis is recognition of central nervous dysfunction (ataxia, loss of balance, convulsions, irrational behavior, unusual behavior, inappropriate comments, collapse, and loss of consciousness) and a body core temperature usually >40.5°C (105°F). The gold standard treatment is whole body cold water immersion. In the field where water immersion is not available it may be necessary to use ice packs or very cold, wet towels placed over as much of the body as possible before transportation of the victim to higher levels of medical care…

Global temperature trend courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

21

Knapik JJ, Epstein Y.

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is available in both injectable and tablet forms. Injectable TXA may also be applied topically.

Book Review

Blood:An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce

By Douglas Starr Perennial, 2002

By Douglas Starr Perennial, 2002

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis

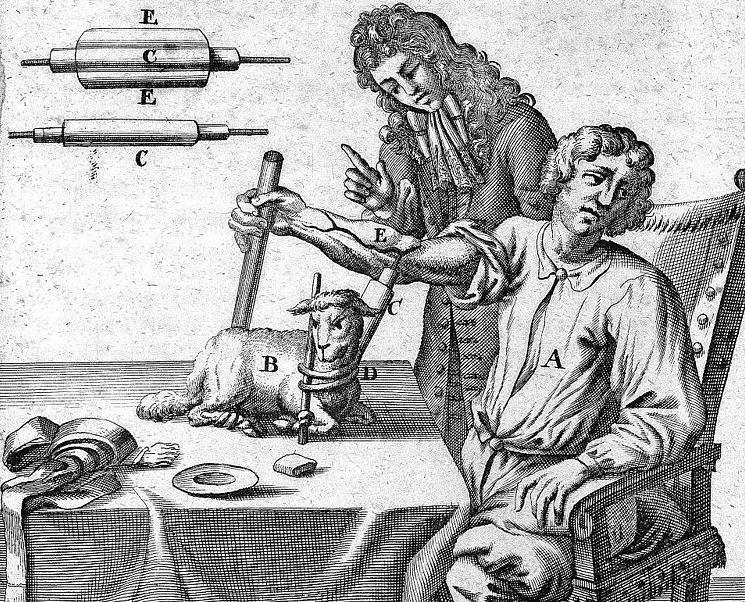

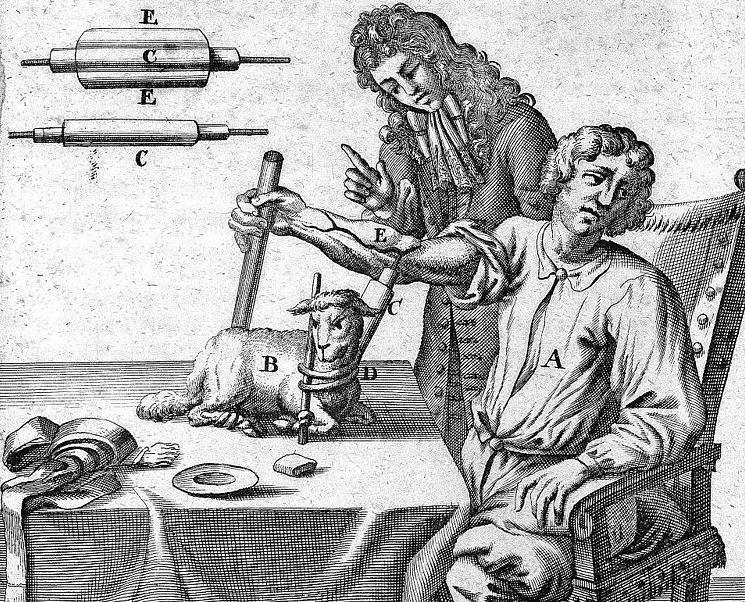

The history of the medicinal application of blood is recounted in thrilling detail in Douglas Starr’s prizewinning book Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce. From the first experiments that attempted to cure insanity via the infusion of animal blood, to the specter of HIV-contaminated blood products (and the ensuing international scandal), Starr offers readers a flyon-the-wall perspective on the heroes, villains, beneficiaries, and victims who populate the centuries-long saga of therapeutic blood.

Blood is divided into three evocatively-titled parts: “Blood Magic,” “Blood Wars,” and “Blood Money.”

“Blood Magic” details the Renaissance era of Western medicine, a time described by Starr as “a haphazard mixture of folk cures, astrology, religious incantations, and lessons from the Greeks.” Blood from “benevolent” farm animals such as calves and sheep is transfused into the insane in the hope that the gentle dispositions of such animals will be made manifest in the human subjects. Bloodletting is performed wholesale, often to the point of exsanguination. Through decades of trial and error, animal-to-human transfusions are abandoned in favor of the decidedly more successful human-to-human transfusions, and, along the way, the ABO blood groups are discovered by Dr. Karl Landsteiner. By the early twentieth century Dr. Richard Lewisohn has tackled the seemingly insurmountable problem of the coagulation of stored blood with the question “Might it not be possible to inhibit the danger of the clotting of blood during its transfer without diminishing the clinical value of blood to the recipient?” His perennial solution to the problem: sodium citrate.

“Blood Wars” focuses primarily upon the impact of blood and plasma on the Allied andAxis powers of World War II. The degenerate philosophy and cultural isolation of the Nazis put their medical science years behind the rest of the world, and their inability to transfuse their casualties as effectively as their rivals is cited as a major contributor to their demise.

Blood concludes with “Blood Money,” a fascinating study in dichotomies: humanitarian idealism and the exploitation of the poor; blood as a life-saving therapy and blood as a deadly brew teeming with viruses; wellmeaning doctors transformed into pariahs and unscrupulous opportunists making their fortunes on the back of one of the most morally and legally ambiguous commodities of all time.

22

Douglas Starr is an associate professor of journalism and codirector of the Knight Center for Science and Medical Journalism at Boston University. A former newspaper reporter and field biologist, he has written on the environment, medicine, and science for a variety of publications, including Smithsonian, Audubon, and Sports Illustrated. He was science editor for Bodywatch, a health series that ran for three years on PBS.

–

“Blood should be included in all first- and second-year medical curricula.”

Scientific American

“

That the king’s doctor would infuse a man with animal blood was not outrageous, given the state of medicine at the time. Seventeenth-century medicine was a haphazard mixture of folk cures, astrology, religious incantations, and lessons from the Greeks. Physicians would treat patients with a desperate assortment of remedies: roots, herbs, worms; powders made from precious stones, crabs’ eyes, vipers’ tongues, or “moss from the skull of a victim of violent death.” Barbers operated as frequently as surgeons; both would destructively bleed patients at the first sign of disease, draining out the “bad humors” with the blood, often to the point of death. Life was unhealthy, brutish, and short…”

“In the Pacific [World War II], a wounded navy gunner named Harry Starner was receiving some plasma when, glancing at the bottle, he saw his own name; he had donated blood while on leave in Washington, D.C. That infinitesimally small possibility demonstrated just how industrialized

how mastered – blood had become. It was the ultimate stage in the liquid’s evolution. Blood, once held in religious regard, had been removed from a man’s circulatory system, separated, processed, freeze-dried, packaged, shipped, and reconstituted – only to be injected into the same individual in a completely different form several months later and half a world away.”

“…blood is both a gift and merchandise, and only by accepting the dual nature of blood products will humanity use them with sufficient care and intelligence. Blood is a precious and dangerous medicine. We must be careful how we use it.”

23

–

Remote &Austere Medicine Field Guide for Practitioners, 2nd edition

Contents:

Prolonged field care

Tropical medicine

Extended formulary

Snakes and arthropods

ACLS & ECGs

Paediatric ALS & diseases

OB/Gyn

Dentistry

Ultrasound

Dermatology & STIs

Field laboratory techniques

Environmental medicine

Call-for-evacuation templates

…and much more!

AVAILABLE LATE

SEPTEMBER 2019 at corom.org

Review by Jason Jarvis

Review by Jason Jarvis