13 Resources

A selection of medical references, gear, websites, podcasts and books

15 Journal Watch

Vulnerability to Snakebite Envenoming: A Global Mapping of Hotspots

Emergency Drone System Displays

Effective EMS and Rescue Applications

Ether Anesthesia in the Austere Environment

ASTMH Welcomes New Single-Dose P. vivax Drug

16 Book Review

Burma Surgeon

The official newsletter of the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine Foundation Autumn 2018 2 About CoROM 3 Dean’s Desk 3 Message from the Medical Director 4 Photo Gallery 5 CoROM Courses 7 Where Are They Now? Joshua Bailey on lessons learned with CoROM 8 Instructor Spotlight Q & A with Dr. Andrew Grech 10 Continuing Education Neil Coleman’s research series, continued 11 Trends in Traumatology Jason Jarvis on junctional tourniquets 12 Test Yourself ECG Recognition Drug Calculation Clinical Case 6 On Expedition in Nepal Sustainability, sanitation, and snakes by Nicole Foster 10 THOR 2018 The latest science from the Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research (THOR) Symposium by Aebhric O’Kelly FEATURES

and

CoROM Remote Paramedic students and cadre prepare to enter the cadaver dissection

procedures lab at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University in Tanzania

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine is an academic not-for-profit organisation for healthcare professionals working in the remote, offshore, transit, military and security industries.

The College was founded in 2014 and is governed by a voluntary MedicalAdvisory Board (MAB) consisting of medical professionals from NorthAmerica, Europe,Africa and the Middle East. The College is gaining registration with the National Commission for Further and Higher Education of Malta to become a degree granting educational facility.

CoROM focuses on the improvement of medical training and the practice of healthcare for those working in remote, austere and difficult environments.

What does CoROM specialise in?

About CoROM 2

Dean’s Desk

The College is returning from our summer leave and preparing for a busy autumn semester. We have nearly thirty delegates attending the Tropical, Travel and Expedition Medical Skills course this November. In addition, we have seven Remote Paramedic delegates coming for the four weeks of classroom training this November.

The summer was by no means a period of inactivity – four of our faculty members flew down to Kilimanjaro, Tanzania to run the Remote Paramedic and TTEMS courses.

The College continues to move from strength to strength as we focus on expanding our courses to new venues. We plan to run the Clinical TTEMS course in Mae Sot, Thailand in January of 2019.

The College purchased six new field microscopes and two iPad based ultrasound probes. We plan to implement ultrasound training in as many training scenarios as is practical.

We are delighted to see so many delegates coming from all over the world to participate in our academic programmes.

Message From The Medical

Director

As we approach the new academic year readers of The Compass will be selecting courses that will be part of their continued professional development. The final selection will depend on factors like time, costs, potential job prospects, etc.As adult learners we have also to do our day jobs.

I hope that readers of The Compass consider CoROM as their educational provider. We are still a small organisation with the personal touch. You will meet fellow students (and CoROM staff) who are moving onto a more advanced level of training. The task ahead is not as daunting when you discover you are not alone.

I wish everybody continued success in their future studies and hope it will be an enjoyable and satisfying experience.

Best Wishes, Winston

3

Aebhric O’Kelly 18E MA FAWM DipPara CCP-C TP-C

Winston de Mello MBBS FRCA FFPMRCA FIMCRCSEd CCP-C

Photo Gallery

4

Scenario training at the TTEMS course Dr. Kasia Hampton leading an ultrasound class

Adrian Spillett assisting splint application at the Remote Paramedic course in Tanzania

Scenario training

Dental skills lab at the TTEMS course

Nicole Foster leading the Incision and Drainage skills lab during the TTEMS course

CoROM Courses

SEATTLE

Tropical Medicine short course

TTEMS

RAMS (courses under development)

MALTA

CC-P 22-27 October 2018

CRP 29 October-24 November 2018

RMLS 7-9 November 2018

TTEMS 19-23 November 2018

RAMS 26-30 November 2018

CRP 18 March-13 April 2019

TTEMS 8-12 April 2019

RAMS 15-19 April 2019

CC-P 29 April-4 May 2019

PARSIC (dates TBD)

Burns course (dates TBD)

Pain Mgnt for Clinicians (dates TBD)

TANZANIA

CRP 27 August-22 September 2018

TTEMS 17-21 September 2018

CRP 2 September-28 September 2019

TTEMS September 2019

LEGEND

THAI-BURMA BORDER

Clinical TTEMS course

14-26 January 2019

CC-P: International Critical Care Paramedic (with optional pre-study week)

CRP: CoROM Remote Paramedic*

PARSIC: Pre-Hospital Airway and Rapid Sequence Induction

RAMS: Remote Advanced Medical Skills

RMLS: Remote Medical Life Support

TTEMS: Tropical, Travel and Expeditionary Medical Skills

* The CRP course also includes 20-30 weeks of online training, plus a 400-hour clinical rotation.

Advanced Certificate and Diploma Courses

Higher Diploma in Remote Paramedic Practice

Postgraduate Certificate in Austere Critical Care

Clinical Placements

University teaching hospital, Moshi, Tanzania

Remote clinics, Northern Tanzania

Accident and Emergency, St. Mary’s Hospital, UK

HEMS and ambulance placement, Budapest, Hungary

Online Courses

Pharmacology for the Remote Medic

Minor Illnesses Course

Minor Emergencies Course

Tactical Medicine Review

Level 3 Health and Safety for the Workplace

Level 3 Food Safety for the Workplace

For more information about training with CoROM, please visit corom.org. Please address newsletter correspondence to editor@corom.org.

5

On Expedition in Nepal

Sustainability, sanitation, and snakes

by Nicole Foster

by Nicole Foster

On my journey to find my next adventure, I emailed Raleigh International in order to see if they needed any medics for upcoming expeditions - a week later I was in Nepal, choosing my options for medic work in a team of 5 medics. A10-week expedition (13 weeks in total including induction and ENDEX) is split into 19-day phases with several handover days in between. The total 10-week expedition consists of two community phases, wherein the medic, volunteer managers and the venturers live within a community in the Gorkha region of Nepal, rebuilding or constructing water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure including reservoir tanks, tap stands, hand washing stands and toilets. Time in community is split with the second phase 19-day trek, during which the young venturers learn valuable leadership skills.

Nicole Foster

Nicole Foster

As a medic, you are expected to complete the 2-week induction period, during which you provide medical and public health training to the volunteer managers. Medical 1-2-1s is also a part of the responsibilities for both managers and the volunteers and from this, medical treatment plans are mapped out with managers and the head office. If the medic is based in a community or on trek, they are responsible for 11-18 people; while based in head office as the duty medic, the medic is responsible for all of the venturers and managers, which can range from 60-80 people, via phone consult and or MEDEVAC/ CASEVAC (ground vehicle or helicopter).

The med kit provided is adaptable to both static community phases and the trek, containing the basics such as antibiotics, pain and gut medications, lotions and potions, and wound dressings, while each expedition carries 2 emergency kits for anaphylaxis, asthma and meningitis. The main problems encountered included diarrhoea, dehydration, slips and trips, heat rash, foreign body (eye), blisters and infected insect bites. You will get to know which antibiotics are used for what, and you will gain experience working within primary care. Time away from home in challenging environments without access to the outside world makes for stressful situations, and particular care must be taken with mental health of both the young volunteers and the managers.

Raleigh International promotes a culture of safety, with the medics playing an integral role in the expedition process (including some snake wrangling!), allowing young venturers to learn leadership and sustainability in a safe environment while also providing much needed assistance to resource-poor countries. Raleigh offers expeditions to multiple countries (Nepal, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Tanzania and Borneo) several times a year, with expeditions ranging from 5,7 and 10 weeks. If you would like more information, please visit https://https://raleighinternational.org

BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

6

“A small incident during training that involved this snake sleeping on the head of one of the medics!”

Where Are They Now?

TTEMS/RAMS graduate Joshua Bailey on lessons learned with CoROM

Joshua Bailey is a U.S. physician assistant and former U.S. Army medic. He currently works in an urgent care clinic and is pursuing his Fellowship of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM).

C.

C.

I recently attended the CoROM in Malta for the TTEMS and the RAMS. I have been attending different classes while in pursuit of the FAWM and ran across the CoROM. To be honest I had to go to Google to see where Malta was before I signed up for the classes. The thing that I noticed about the classes right from the start was the level of experience that the instructors brought to the lectures and hands on activities.

The lectures especially about tropical diseases stuck in my mind. I found myself working urgent care in Denver with a patient who had remitting and relapsing fevers. In my mind I could hear Jason repeating “fever in the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise.” We have a growing refugee population that may be bringing pathology that is not common to our area, so I asked them where they were from. They had just returned from the Sudan. The TTEMS helped build my differential to include some less common diseases, which may not have been on my radar for Denver.

I am an Army-trained physician assistant who began his career as a line medic. One of the things that I miss about the military is the training. I haven’t found many courses that prepare you quite the same way that the uniformed services do. The hands-on component that the CoROM provided was above average and better than most of my military training. The scenarios taught me how to evacuate patients from vehicles and buildings that I had forgotten. It was a much-needed reminder on how to use my technical skills in an austere environment, far removed from the comforts of home. The first pulse you check in emergency medicine is your own.As we evacuated simulated patients off a helicopter and began to triage, I found myself acutely aware that checking my own state provided my casualties a better outcome.

As I continue my clinical practice here in the states and look for opportunities overseas, I feel more prepared to practice medicine both here and abroad. The locations for the training is not a bad bonus as well. I hear they are going to start teaching in Thailand. Alittle trauma didactic and drunken noodles is right up my alley.

7

Joshua

Bailey PA-C, NREMT-P FAWM Candidate

Joshua Bailey practicing venous cutdown technique during the RAMS course

Instructor Spotlight

Q andAwith Dr.Andrew Grech

Andrew completed his undergraduate medical studies in Malta, where he still works as a registrar in anaesthetics and critical care. After dabbling in remote and industry paramedic education for a few years, he became one of the College’s co-founders in 2016 and remains a trustee on the executive board. He enjoys teaching and being taught, as well as steadily accumulating FAWM credits in his spare time.

What aspect of CoROM motivated you to join the College?

CoROM Co-founder and Advisory Board Member

It seemed to me that in between existing pre-hospital and austere medicine courses there existed a niche that no single programme had yet fulfilled. I was keen to add what I could to the developing specialty of remote medicine and threw my hat into the ring with a group of like-minded individuals interested in pooling experience to accelerate remote and offshore medical education into the 21st century.

What is your favorite teaching topic at CoROM?

I cannot help but say airways! The breadth of airway gadgetry and interventions has increased dramatically over the last few years, and there is no reason why many of these cannot be implemented in the offshore or remote setting when airway compromise is an issue. I developed the College’s PARSIC course a couple of years ago to provide a foundation for rapid sequence airway control, but this barely scratches the surface of what remote providers out there are doing.As many critical care providers will undoubtedly be aware, the multitude of different techniques from delayed sequence to advanced airway decontamination maneuvers is staggering!

Where would you like to see CoROM go in the next five years?

The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine is a multi-faceted machine. We are involved in preclinical simulation training, clinical elective work, continuing professional development credits and increasingly academic qualifications too. There are several sub-specialty programmes available ranging from tactical to tropical medicine, but what I would like to ensure in the future is that the College offers a course for every level of professional as well as every interest. Whether a curious first aider, seasoned emergency medical technician or newly appointed consultant, I believe CoROM should have something to offer at every stage of one’s career. That and a bigger brother textbook to our handbook, of course!

8

Andrew Grech

MD MSc PgCertMedEd MAcadMEd CCP-C FP-C TP-C

Andrew Grech teaching airway intervention theory in Malta

Describe a medical case that has had a lasting impact on you.

I recently put an axillary level nerve block into a patient who was experiencing forearm and hand pain despite high doses of opioid analgesics. This worked a treat and within minutes the patient was entirely pain free with only a little motor weakness of the arm to show for the procedure. The exquisite response to tactful use of local anaesthetic in the face of opioid-resistant pain is something which struck me as something we often underappreciate. Common drugs such as lidocaine and bupivacaine should be in every remote practitioner’s arsenal, and learning even a few simple tricks such as fascia iliaca and digital blocks goes a long way towards making your patient comfortable during prolonged field care and transfer times.

For medical practitioners wanting to learn more about field anesthesia, which three references would you recommend?

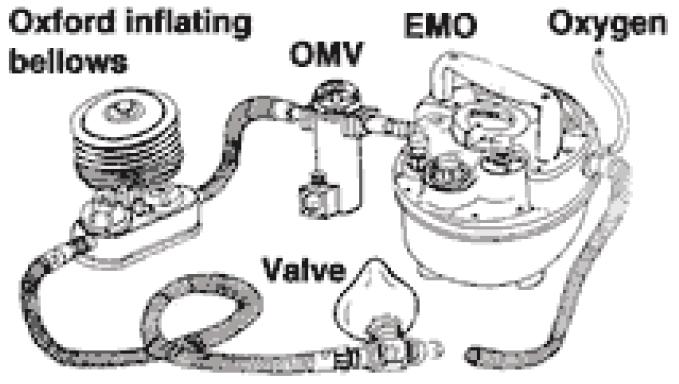

With modern advances in what practitioners of the anaesthetic arts can do, I think the term ‘field anaesthesia’ itself can be difficult to define! Indeed, it no longer refers simply to ether bubbled through a miniature EMO vaporizer to a casualty of war in need of an emergency amputation; we now talk of anaesthetics for austere critical care and facilitation of aeromedical retrievals.

I do not typically like referring to one textbook and often prefer just checking out the methodology of new or reviewed techniques in the literature. However, the addition of Retrieval Medicine to one’s kit bag is never a bad idea (Charlotte, E., 2016. Retrieval Medicine (Oxford Specialist Handbooks). 1st ed. Oxford: OUP).

Additionally, the online resource Life in the Fast Line (https://lifeinthefastlane.com) represents a unique meld of emergency medicine, anaesthetics and critical care for those skirting the fine line between the three.

Finally, not to neglect current literature trends on the topic, I’d like to recommend a rather curious perspective to austere anaesthesia as discussed by Komorowski et al in their recent 2018 article (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29507873). Give it a read…it’s out of this world!

9

Andrew Grech leading the chest drain skills lab in Malta

THOR 2018

The latest science from the Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research Symposium

by Aebhric O’Kelly

by Aebhric O’Kelly

The Trauma Haemostasis and Oxygenation Research (THOR) network offers the annual Remote Damage Control Resuscitation (RDCR) conference which is an invite-only symposium located in Bergen, Norway.

CoROM was extended an invitation to the June conference, an invitation I gladly accepted on behalf of the College.

THOR was created to improve traumatic haemorrhagic shock outcomes by optimising the acute phase of resuscitation. They occupy the forefront of research on resuscitation fluids needed during shock. Their current research suggests that the use of whole blood and blood products by prehospital providers greatly enhances the outcomes for traumatic injuries.

Based on their ongoing research, the College includes the prehospital use of whole blood and blood products in all of our curriculum. We provide hands-on training with buddy transfusion training during our RAMS course.

Continuing Education

Neil Coleman’s research series, continued

Something I am regularly asked is where do you start if you want to do research? My advice to anyone starting out on a project would be to pick something that interests you. It’s a tricky enough road without trying to research something you have little interest in!

Once you have decided what it is you want to research, a really important question to ask is “Why am I researching this?" If you are doing it out of interest, great. If you are trying to prove a point...not so great.

Neil Coleman MSc PG Dip Ed HDip EMT-A Assistant Clinical Professor CoROM Education Manager

Research in its simplest form is throwing evidence in the air and seeing how it lands. Proving your research comes much later in your career, usually at the PhD level.

So now you have a topic, do a literature review. Simply put, this means go to a site like Google Scholar and type in the key words of your research, e.g., “Paramedic, airway, difficult.” You’ll quickly get access to a lot of what is already in print on this topic.

Next month we will look at refining your search parameters, but until then go and explore the literature...it’s endless!

10

Trends in Traumatology

Jason Jarvis on junctional tourniquets

As the number of U.S. troops deployed to the Middle East declined over the past several years, there appeared to me to be an increase in junctional tourniquets (JTQ) being fielded to these remaining troops.

While massive innovation and a continuous stream of retrospective studies were poured into limb tourniquets and hemostatic agents since the early post-9-11 era, the JTQ arrived late on the scene, and hard data on their field effectiveness appears to be scant.

Arecent article* published in the Journal of Special Operations Medicine reflects this dearth of field data. In this study, a total of 12 cases of JTQ application were reviewed. Seven of those applications yielded successful outcomes, three applications failed, and two were “missing documentation regarding success or failure.”

While I have used all four major types of JTQ (CRoC, SAM, JETT, and AAJT) in classroom training sessions, I have not yet had the opportunity to use one in anger. Anecdotal evidence abounds, of course. For example, a colleague of mine reported three successful applications of the AAJT while working as a flight medic inAfghanistan.

It would appear that the utility of the JTQ in hard-to-reach bleeding shows promise, however, the acquisition of further evidence is in order.

11

*JSOM Summer 2018. “Junctional Tourniquet Use During U.S. Combat Operations in Afghanistan.” by Steven G. Schauer, et al.

Jason Jarvis 18D BS NREMT-P TP-C CoROM Tropical Medicine Lead The Compass editor

Combat Ready Clamp (CRoC)

AbdominalAortic Junctional Tourniquet (AAJT)

SAM Junctional Tourniquet

Junctional Emergency Treatment Tool (JETT)

Test Yourself

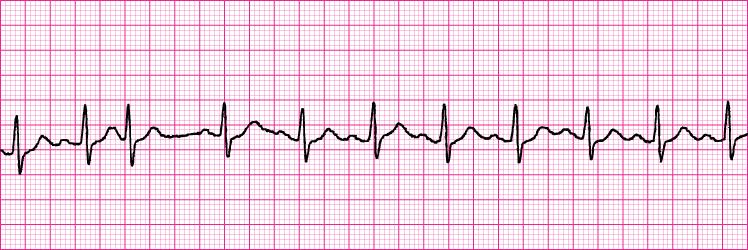

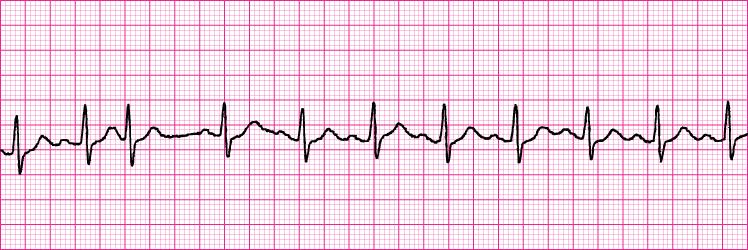

ECG Recognition

A. Junctional tachycardia

B. Sinus tachycardia with one premature junctional contraction

C. Sinus tachycardia with one premature atrial contraction

D. Wandering atrial pacemaker

Drug Calculation

At a remote clinic in Mongolia, your cardiac arrest patient has achieved ROSC, but now suffers from low systolic blood pressure that is refractory to crystalloid IV boluses.

After deciding to use a vasopressor infusion to increase the blood pressure, you discover that the only available vasopressor on hand is 2mg of epinephrine in a 400mL bag of normal saline.Your CPGs call for an infusion rate of 0.2mcg/kg/minute.

The patient weighs 70kg, and, while there is no infusion pump on hand, you have a 60 drop/mLgiving set.At how many drops per minute will you infuse the epinephrine?

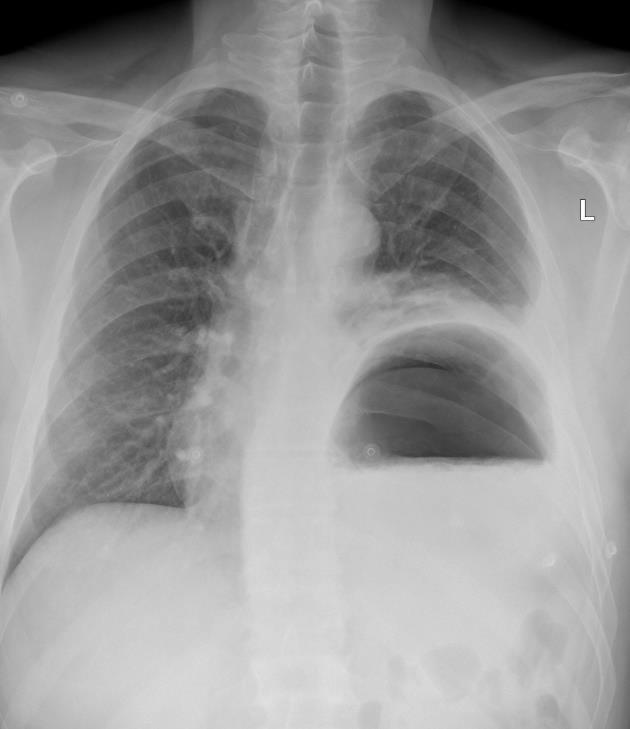

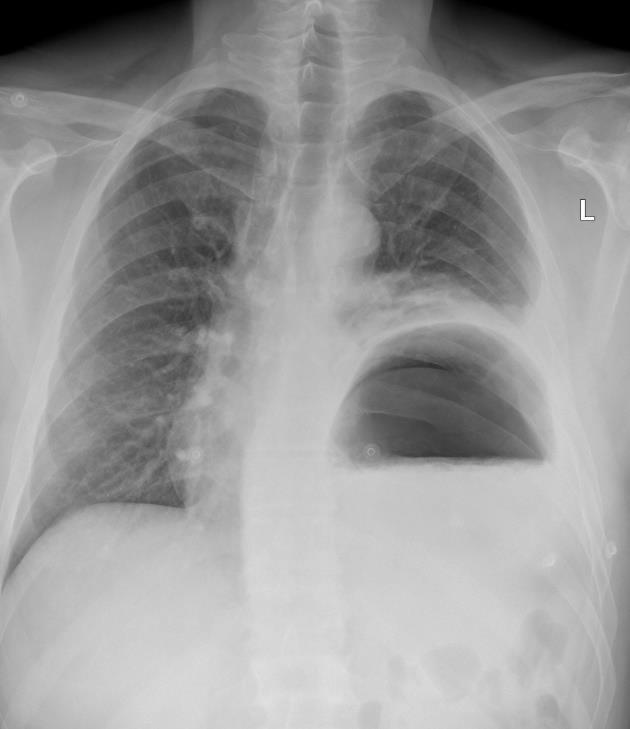

Clinical Case

You are the sole medical provider at an oil refinery in Kirkuk, Iraq.

One of your security vehicle drivers is involved in an unrestrained high-speed collision with a bus and presents to your clinic unconscious and in shock. There is no external bleeding aside from abrasions and superficial lacerations, and you note massive bruising to the anterior thorax. After securing the airway and establishing vascular access, you obtain a chest X-ray that reveals the image to the right.

How would you describe the X-ray findings to your top cover (medical control)?

Answers will appear in the Winter edition of The Compass.

Answers to “Test Yourself” from the previous issue:

ECG Recognition: B. Controlled atrial fibrillation

Drug calculation: This patient can receive up to 8mL of additional lidocaine

Clinical case: Infection with African trypanosomiasis (caused by tsetse flytransmitted protozoa Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense)

12

Resources

Aselection of medical references, gear, websites, podcasts and books

Medical References (Dr. Andrew Grech’s picks)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29507873

Gear Deluxe Field Corpsman Kit available at narp.com

Few non-traumatic events can sideline an otherwise healthy person faster than an intractable foreign body in the eye or ear.

Asolid oto/ophthalmoscope, coupled with curettes, magnetic extraction probe, fluorescein strips, cobalt light, and a magnifier will greatly assist the healthcare provider in keeping their teammates in the game.

Websites diversalertnetwork.org (SCUBAdiver insurance and on-call dive safety assistance) medlineplus.gov (online database of diseases and conditions, drug info, and more)

Podcasts Everyday Emergency: The MSF Podcast Bedside Rounds 60-Second Health

13

Amazon synopsis

In recent years, malaria has emerged as a cause celebre for voguish philanthropists. Bill Gates, Bono, and Laura Bush are only a few of the personalities who have lent their names and opened their pocketbooks in hopes of stopping the disease. Still, in a time when every emergent disease inspires waves of panic, why aren't we doing more to tame one of our oldest foes? And how does a pathogen that we've known how to prevent for more than a century still infect 500 million people every year, killing nearly one million of them?

In The Fever, journalist Sonia Shah sets out to answer those questions, delivering a timely, inquisitive chronicle of the illness and its influence on human lives. Through the centuries, she finds, we've invested our hopes in a panoply of drugs and technologies, and invariably those hopes have been dashed. From the settling of the New World to the construction of the Panama Canal, through wartimes and the advances of the Industrial Revolution, Shah tracks malaria's jagged ascent and the tragedies in its wake, revealing a parasite every bit as persistent as the insects that carry it. With distinguished prose and original reporting from Panama, Malawi, Cameroon, India, and elsewhere, The Fever captures the curiously fascinating, devastating history of this longstanding thorn in the side of humanity.

Amazon synopsis

…“hell on earth”, “a cesspool”, “a death camp”, and “infamous” have all been used by prisoners and critics to describe Andersonville Prison, constructed to house Union prisoners of war in 1864, and all descriptions apply. Located inAndersonville, Georgia and known colloquially as Camp Sumter, Andersonville only served as a prison camp for 14 months, but during that time 45,000 Union soldiers suffered there, and nearly 13,000 died. Victims found at the end of the war who had been held at Camp Sumter resembled victims ofAuschwitz, starving and left to die with no regard for human life. Unable to supply its own armies, the Confederates had inadequately supplied the prison and its thousands of Union prisoners, leaving over 25% of the prisoners to die of starvation and disease.

All told,Andersonville accounted for 40% of the deaths of all Union prisoners in the South, and the causes of death included malnutrition, disease, poor sanitation, overcrowding, and exposure to inclement weather. Andersonville infuriated the North so much that Henry Wirz, the man in charge ofAndersonville, was the only Confederate executed after the war. Before the war, Wirz was a Swiss doctor who had practiced medicine in Kentucky, but while some Southern scholars continue to believe he was simply a victim of circumstance, plenty of evidence suggests his actions were far more insidious and deadly.

14

Books

Journal Watch

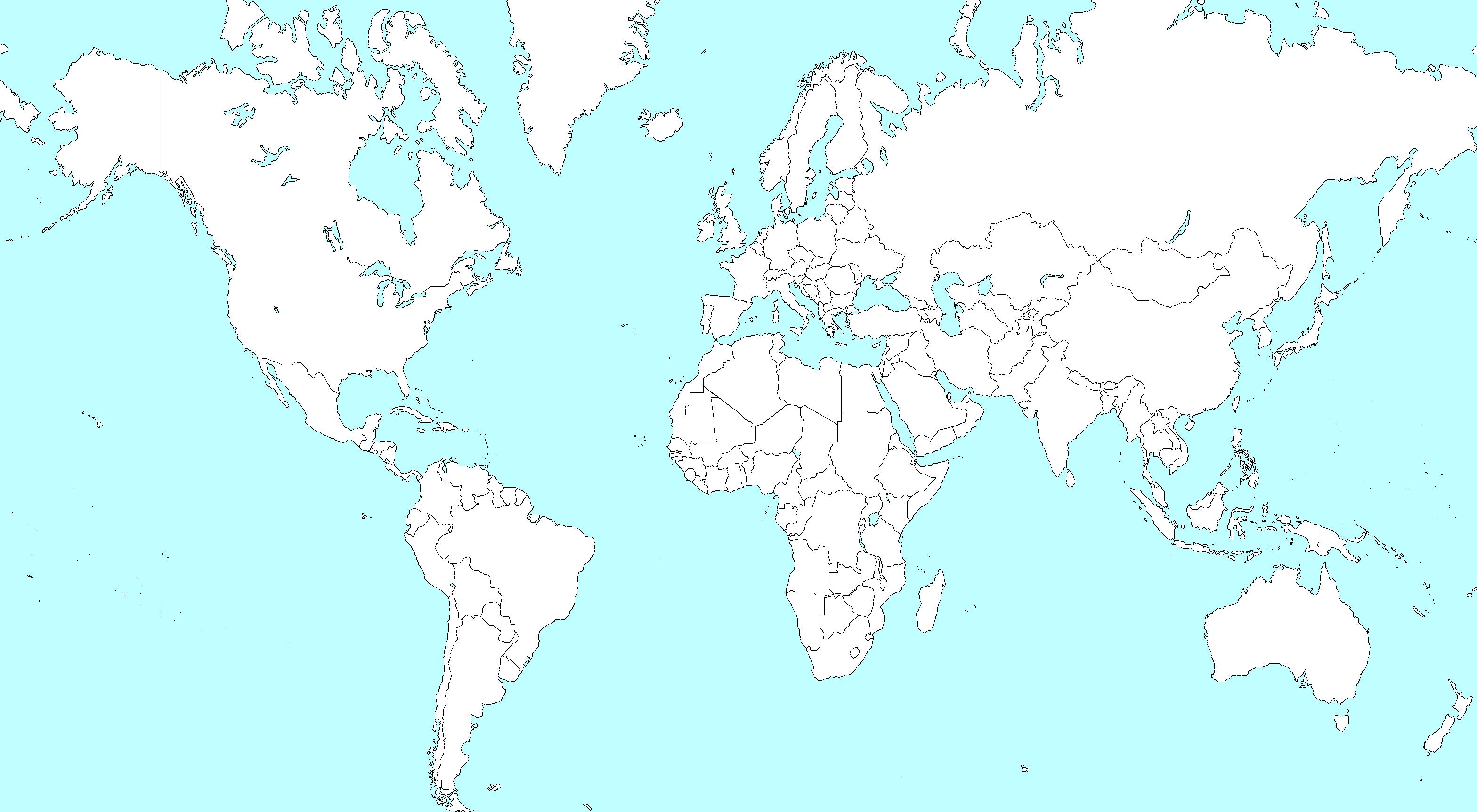

Vulnerability to Snakebite Envenoming: AGlobal Mapping of Hotspots

The Lancet

Published online 2018 July 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31224-8

Joshua Longbottom, et al

Open access funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

INTRODUCTION

Snakebite envenoming is a frequently overlooked cause of mortality and morbidity, responsible for 81,000138,000 deaths annually, and between 421,000 and 1-2 million envenomings. Contact from venomous snakes, spiders, and scorpions contribute to 1-2 million years of life lived with disability annually. The burden remains poorly characterised because of under-reporting; as snakebite is rarely notifiable, existing estimates are typically derived from extrapolated hospital records and community surveys.

Snakebite primarily affects the poor rural communities ofAsia and sub-Saharan Africa, where socioeconomic status and agricultural and other practices contribute to increased snake–human interaction.Venomous snakebites can also inflict a heavy burden on livestock, creating economic hardship for already impoverished communities. Medically important snake species, however, have a cosmopolitan distribution, making snakebite a global challenge.

Emergency Drone System Displays Effective EMS and Rescue Applications

Journal of Emergency Medical Services

Published online 2018 June 1. https://www.jems.com/articles/print/volume-43/issue6/features/emergency-drone-system-displays-effective-ems-and-rescue-applications.html Andreas Claesson, RN, EMT-P, PhD

Open source

CONCLUSION

Drone systems have a strong potential to facilitate lifesaving medical interventions, such as transporting and delivering an AED in cases of OHCA[out-of-hospital cardiac arrest]. Our three-year vision is to implement a drone system that will autonomously dispatch to OHCApatients in suitable areas, defined by current regulations in the jurisdiction, controlled airspace considerations, and other factors associated with air traffic security.

We would like to encourage fire departments and EMS systems worldwide to learn more about the potential of deploying drone technology for both OHCAand water lifesaving purposes.

15

The fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper), a viper native to South America. Vipers are venomous snakes with large hinged fangs, triangular heads, elliptical pupils, and with a dark skin pattern on a lighter background.

The Indian cobra (Naja naja), an elapid native to central southern Asia. Elapids are venomous snakes with permanently-fixed fangs in the upper jaw.

Journal Watch

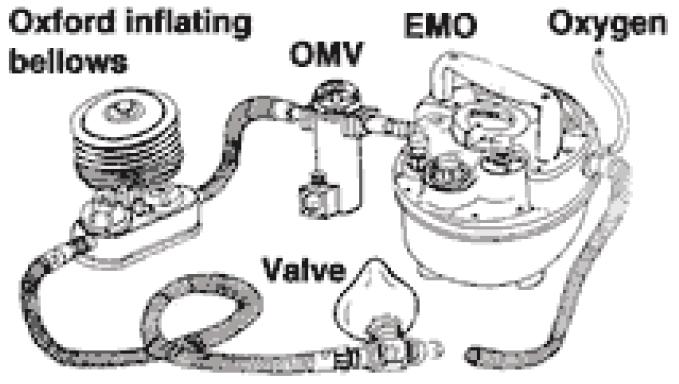

EtherAnesthesia in theAustere Environment

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

Published online 2018 Summer. https://www.jsomonline.org/jsomstorefront/index.php?rt=product/ product&product_id=2355

Morgans LB, Graham N

ABSTRACT

Medical services in the austere and limited environment often require therapeutics and practices uncommon in modern times due to a lack of availability, affordability, or expertise in remote areas. In this setting, diethyl ether, or simply ether anesthesia, still serves a role today as an effective inhalation agent.

An understanding of ether as an anesthetic not only illustrates the evolution in surgical anesthesia but also demonstrates ether's surviving function and durable use as a practical agent in developing nations. Although uncommon, it is not unseen, so a working knowledge should be understood if observation and advocacy for patients receiving this method of anesthesia are experienced.

EMO Ether Inhaler (Epstein, Macintosh, Oxford)

A drawover system is designed to provide anesthesia without requiring a supply of compressed gases

ASTMH Welcomes New Single-Dose P. vivax Drug

American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

Published online 2018 July 25. http://www.astmh.org/blog /july-2018/astmh-welcomes-new-single-dose-p-vivax-drug

Open source

BLOG POST

ASTMH welcomes the FDA’s approval of a new drug, Krintafel (tafenoquine), that can prevent relapse of Plasmodium vivax malaria with a single dose. The previously approved medication for P. vivax malaria requires a 14-day regimen that can be difficult for patients to comply with. Tafenoquine is approved as a single-dose treatment for radical cure of P. vivax malaria in patients 16 years and older and who do not have an enzyme problem, called G6PD deficiency, as it can cause severe anemia.

Tafenoquine, the first new treatment approved specifically for P. vivax malaria in more than 60 years, was synthesized by scientists at the Walter ReedArmy Institute for Research (WRAIR) in 1978.

Despite being much less known than its P. falciparum African counterpart, P. vivax is still a very significant cause of disease and death worldwide, with more than 2.5 billion people living at risk of being infected by this malaria parasite. According to the WHO, the P. vivax parasite is a major cause of malaria in the Americas, Southeast Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean. There were approximately 8.5 million cases of P. vivax in 2016, and malaria caused by this parasite can keep reoccurring months or even years after the initial infection if not treated properly. Additionally, P. vivax, formerly considered a "benign" parasite, is now recognized as being associated with severe disease, and even death.

16

Book Review

Burma Surgeon

By Gordon S. Seagrave

W.W. Norton and Co.

First edition published in 1943

Review by Jason Jarvis

Burma Surgeon is an autobiographical account of the exploits ofAmerican doctor and missionary Gordon S. Seagrave (1897-1965) before and during Japanese hostilities in World War II-era Burma.

After receiving his medical training at Johns Hopkins, Seagrave – with his wife and young child in tow – departed for Burma in 1922. From his remote hospital near the Chinese border, Seagrave ministered tirelessly to the needs of the local population, became conversant in the regional dialects, trained local nurses, and spearheaded many building projects. In the early days of his jungle practice, his untrained wife juggled the responsibilities of child rearing and the administration of chloroform anesthetics. The Seagrave family personally contended with tropical diseases from virtually the time they arrived in Burma, in addition to thousands of parasite-ridden Burmese and Chinese patients.

Seagrave’s selfless and unflagging approach to patient care is reflected in the following passage: “The Medical Examiner of the Mission Board in New York once said, ‘If Seagrave were a good doctor, he would not allow himself to get infected with malaria and dysentery.’ That is quite correct. If I had been a good doctor, missionary doctor, I would have climbed under the mosquito net at 6:00 pm every night and stayed there and I would have boiled all of my drinking water myself. I certainly would not have let my cook ‘boil’it for me, nor would I have ever answered those numberless emergency calls at night to villages near and far. I would have let the crazy fools go ahead and die unassisted.”

1940 proved to be quite an eventful year in the life of the Seagraves. Amassive plague epidemic subsided only to be replaced by a malaria outbreak. In October the Japanese bombed northern Burma, and by December Rangoon had been bombed as well. Seagrave, by now highly-respected and well-connected among the locals (as well as being fluent in the Burmese, Shan, and Karen languages) found himself swept up in the tide of war.

Battlefield-commissioned into the United States Army at the rank of major, Seagrave was deployed to far-forward austere surgical theaters, in which he operated on hundreds of wounded troops (mostly Chinese). Due to the intense heat and humidity, he performed many of these surgeries clad only in shorts, with assistants swatting the mosquitoes from his body while he worked. As the Japanese front moved ever south, Seagrave and his loyal cadre of nurses were forced on a long and arduous retreat to safety through the Burmese wilderness via truck, pony, raft, and finally, on foot.

17

Dr. Gordon S. Seagrave

by Nicole Foster

by Nicole Foster

BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

BSc, CCP-C, CiiSCM, MPHTM FAWM candidate CoROM Faculty

C.

C.