State Supplement sponsored by:

PACIFIC NORTHWEST EDITION

A Supplement to:

THOUSANDS of units in service Shipment in 1-3 days

®

SAME DAY shipping on parts & tools FULLY SUPPORTED by a 75 YEAR FAMILY BUSINESS

September 2 2018 Vol. III • No. 18

10% off 10,000 ft. lb. hammers

“The Nation’s Best Read Construction Newspaper… Founded in 1957.”

Why pay more?

CALL 800-367-4937

Your Pacific Northwest Connection – Patrick Kiel – 1-877-7CEGLTD – pkiel@cegltd.com

*On approved credit • Financing Available

Historic Columbia River Highway Needs Modern Updates By Lori Tobias CEG CORRESPONDENT

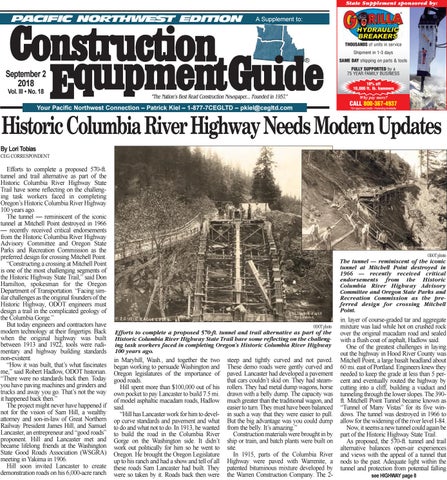

Efforts to complete a proposed 570-ft. tunnel and trail alternative as part of the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail have some reflecting on the challenging task workers faced in completing Oregon’s Historic Columbia River Highway 100 years ago. The tunnel — reminiscent of the iconic tunnel at Mitchell Point destroyed in 1966 — recently received critical endorsements from the Historic Columbia River Highway Advisory Committee and Oregon State Parks and Recreation Commission as the preferred design for crossing Mitchell Point. “Constructing a crossing at Mitchell Point is one of the most challenging segments of the Historic Highway State Trail,” said Don Hamilton, spokesman for the Oregon Department of Transportation. “Facing similar challenges as the original founders of the Historic Highway, ODOT engineers must design a trail in the complicated geology of the Columbia Gorge.” But today engineers and contractors have modern technology at their fingertips. Back when the original highway was built between 1913 and 1922, tools were rudimentary and highway building standards non-existent. “How it was built, that’s what fascinates me,” said Robert Hadlow, ODOT historian. “There were no standards back then. Today you have paving machines and grinders and trucks and away you go. That’s not the way it happened back then.” The project might never have happened if not for the vision of Sam Hill, a wealthy attorney and son-in-law of Great Northern Railway President James Hill, and Samuel Lancaster, an entrepreneur and “good roads” proponent. Hill and Lancaster met and became lifelong friends at the Washington State Good Roads Association (WSGRA) meeting in Yakima in 1906. Hill soon invited Lancaster to create demonstration roads on his 6,000-acre ranch

ODOT photo

The tunnel — reminiscent of the iconic tunnel at Mitchell Point destroyed in 1966 — recently received critical endorsements from the Historic Columbia River Highway Advisory Committee and Oregon State Parks and Recreation Commission as the preferred design for crossing Mitchell Point. ODOT photo

Efforts to complete a proposed 570-ft. tunnel and trail alternative as part of the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail have some reflecting on the challenging task workers faced in completing Oregon’s Historic Columbia River Highway 100 years ago.

in Maryhill, Wash., and together the two began working to persuade Washington and Oregon legislatures of the importance of good roads. Hill spent more than $100,000 out of his own pocket to pay Lancaster to build 7.5 mi. of model asphaltic macadam roads, Hadlow said. “Hill has Lancaster work for him to develop curve standards and pavement and what to do and what not to do. In 1913, he wanted to build the road in the Columbia River Gorge on the Washington side. It didn’t work out politically for him so he went to Oregon. He brought the Oregon Legislature up to his ranch and had a show and tell of all these roads Sam Lancaster had built. They were so taken by it. Roads back then were

steep and tightly curved and not paved. These demo roads were gently curved and paved. Lancaster had developed a pavement that cars couldn’t skid on. They had steamrollers. They had metal dump wagons, horse drawn with a belly dump. The capacity was much greater than the traditional wagon, and easier to turn. They must have been balanced in such a way that they were easier to pull. But the big advantage was you could dump from the belly. It’s amazing.” Construction materials were brought in by ship or train, and batch plants were built on site. In 1915, parts of the Columbia River Highway were paved with Warrenite, a patented bituminous mixture developed by the Warren Construction Company. The 2-

in. layer of course-graded tar and aggregate mixture was laid while hot on crushed rock over the original macadam road and sealed with a flush coat of asphalt, Hadlow said. One of the greatest challenges in laying out the highway in Hood River County was Mitchell Point, a large basalt headland about 60 mi. east of Portland. Engineers knew they needed to keep the grade at less than 5 percent and eventually routed the highway by cutting into a cliff, building a viaduct and tunneling through the lower slopes. The 390ft. Mitchell Point Tunnel became known as “Tunnel of Many Vistas” for its five windows. The tunnel was destroyed in 1966 to allow for the widening of the river level I-84. Now, it seems a new tunnel could again be part of the Historic Highway State Trail. As proposed, the 570-ft. tunnel and trail alternative balances open-air experiences and views with the appeal of a tunnel that nods to the past. Adequate light within the tunnel and protection from potential falling see HIGHWAY page 8