PUERTO PRINCESA SUBTERRANEAN RIVER NATIONAL PARK (PPSRNP) PUERTO PRINCESA CITY

PUERTO PRINCESA SUBTERRANEAN RIVER NATIONAL PARK (PPSRNP) PUERTO PRINCESA CITY

Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park would like to thank the following people and agencies for their significant contributions to the development of our Green Recovery Plan:

Hon. Lucilo Bayron, Mayor, Puerto Princesa City

DENR Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) Palawan

DENR Community Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) Puerto Princesa City

Puerto Princesa City Environment and Natural Resources Office (City ENRO)

Puerto Princesa City Disaster Risk Reduction Management Office (CDRRMO)

Western Philippines University (WPU)

Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS)

Philippine National Police - Puerto Princesa City

We are extremely grateful to Center for Conservation Innovations Ph Inc (CCIPH), Resources, Environment, and Economics Center for Studies (REECS), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Sustainable Interventions for Biodiversity, Oceans, and Landscape (SIBOL) Project

In the western reaches of the Philippines, nestled on the enchanting island of Palawan, lies a natural wonder that has captivated the hearts of travelers and scientists alike the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP). This pristine sanctuary, shrouded in lush forests and limestone cliffs, boasts a geological marvel and ecological treasure that beckons adventurers from around the globe The park is situated in the city of Puerto Princesa, the capital city of the province of Palawan, often referred to as the “Last Frontier’’ due to its untouched natural beauty Specifically, PPSRNP graces the northwestern coast of the city Spanning an expansive 22,202 hectares (approximately 54,862 acres), the park is a vast expanse of natural wonders waiting to be explored Its most iconic feature is the Puerto Princesa Underground River (PPUR), a winding watercourse that stretches an impressive 8 2 kilometers into the heart of a limestone karst cave PPSRNP IN A NUTSHELL

PPSRNP AMID THE PANDEMIC

The 2020 global pandemic that swept across the world did not spare this remote paradise As COVID-19 spread its invisible veil, the oncebustling tourist flow to PPSRNP slowed to a trickle Travel restrictions, health concerns, and economic challenges united and deterred the spirit of exploration that once drew visitors to this unique destination for generations Local communities that relied on tourism for their livelihoods found themselves in front of unprecedented hardships The indigenous groups, who had shared their rich cultural heritage with tourists, saw their traditional way of life disrupted Conservation efforts faced new challenges as resources dwindled, and the delicate balance between preservation and economic sustainability became more precarious than ever

SUPER TYPHOON ODETTE HITS PPSRNP

Life within the four barangays of PPSRNP flowed like a gentle river, calm and undisturbed As the day dawned on the 17th of December 2021, the island was alive with the promise of Christmas celebrations Families prepared to come together, their hearts brimming with joy

The sun painted the skies in hues of gold, and the people went about their daily routines, blissfully unaware of the tempest that was brewing on the horizon On that fateful day, the community was unprepared for the merciless tempest it was Typhoon Odette, known as Rai on the international stage. With the Park still gathering its bearings amidst a global pandemic, a formidable force of nature arrived on the island of Palawan on the 17th, rewriting the Park’s story forever. By morning, the typhoon had made its presence known, unleashing its fury. Typhoon Odette, classified as a Signal III typhoon, had chosen Puerto Princesa as its final battleground The howling winds and relentless rain turned the day into a nightmarish ordeal that would stretch on for an agonizing 24 hours

The once-blue skies turned ominous, heavy with dark clouds, as the tempest approached The forest took on an eerie stillness Birds, once abundant, retreated to shelters, sensing the impending calamity Rangers like Allan Daganta, who had spent their lives in this lush haven, felt an uneasiness in the air Odette’s fury struck with merciless precision Winds howled, trees trembled, and the heavens wept torrents of rain Daganta, who had sought refuge ahead of the storm, watched as Odette descended upon the park Trees that stood for centuries were torn from their roots, and the very ground beneath their feet shook with fear The lush forests, home to diverse flora and fauna, bore the brunt of the tempest, with trees uprooted and scattered like matchsticks

At the forest’s edge, where the old-growth trees had once stood tall and proud, there lay a haunting sight. More than 2,200 trees, some centuries old, lay broken and defeated. The forest, once a vibrant symphony of life, went eerily silent. Patrol boats and fishing vessels were swallowed by the raging sea, disappearing into the abyss. The park’s infrastructure crumbled, leaving behind a trail of devastation. The tempest’s relentless assault left no corner of PPSRNP untouched.

Each barangay found themselves in the storm’s unforgiving grip Floodwaters rose and the residents were forced to evacuate, their homes inundated by the rising tide Amid the chaos, it became evident that this was not just a passing storm but a life-altering event Flash floods struck with devastating force, affecting Marufinas, Cabayugan, and Tagabinet Infrastructure crumbled, agriculture was decimated, and the once-abundant supply of livestock became scarce Drinking water, once clean and abundant, was now a priceless commodity. The source of electrical power, the Sabang Renewable Energy Corporation (SREC), was severely damaged, plunging the community into darkness. The food supply was paralyzed, leaving the community isolated for an agonizing week, with roads impassable and communication nonexistent.

The city that connected Cabayugan to the outside world was rendered incommunicado, its signal lost to the ravages of the storm Tourism sites, like Ugong Rock and the Mangrove Paddle Boat, lay in ruins The tourism industry, already reeling from the pandemic’s impact, now faced another devastating blow, with recovery predicted to take up to ten months The impact was profound, reverberating through the entire community Cabayugan was not just a quiet town; it was a tourist destination, known for its natural beauty and warm hospitality The typhoon’s wrath left its mark on the livelihoods of the people, affecting not only the 5,000-strong population but also the Millions of tourists who had come to experience its charms But the world below, the underground river that had enthralled countless visitors, remained concealed beneath the chaos

After the typhoon’s fury had passed, a heavy silence ruled over PPSRNP As the days passed, park rangers and conservationists emerged from their shelters to assess the damage Assessing the damaged areas was a daunting task as fallen trees obstructed their paths People began the arduous journey of post-typhoon recovery under the scorching heat, while facing the challenge of rebuilding their lives and their beloved community, vowing to emerge stronger and more resilient than ever.

Central and northern Palawan suffered Odette’s wrath over that weekend Life and property were ravaged on an unimaginable scale, and the island’s resilience was put to the test A week after the devastation, the province remained cut off from the world, with power and communication lines severed. Isolation reigned supreme, and information was a rare commodity within the capital of Puerto Princesa City.

The storm’s relentless rains flooded areas in the city with ten barangays submerged in waistdeep waters as rivers overflowed their banks. Landslides scarred the villages of Binduyan, Concepcion, and San Rafael, adding to the challenges of rescue and recovery Preliminary reports began to trickle in and offered a grim snapshot of the situation At least 22 lives were tragically lost, and 16,000 families found themselves displaced Roxas town, where Odette made landfall with winds of 185 kilometers per hour suffered the most In Puerto Princesa City, disaster risk reduction authorities confirmed seven fatalities, including the heartwrenching loss of a three-month-old baby girl and a six-year-old boy, who tragically drowned in the unforgiving currents of the Irawan River Four more souls perished in Langogan, while one lost life was claimed in Lucbuan

The list of missing people grew longer with each passing day, with at least 31 individuals reported missing throughout Palawan Sixteen (16) residents and ten (10) fishermen in Roxas town were among those missing In Aborlan town in the province’s southern reaches, five fishermen were reported lost, while seven individuals were reported missing in Puerto Princesa City by the City Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office. Beyond the tragic loss of life and loved ones, the very fabric of daily life was torn apart. Palawan Electric Cooperative (PALECO) reported that 12 major transmission lines were felled by Odette’s merciless winds of 185 kilometers per hour. Thirteen teams were deployed to assess the damage, clear debris, and embark on the arduous journey of rehabilitation.

By January 18, 2022, the estimated damage costs amounted to PhP 988, 709, 547 in Puerto Princesa City alone, which include damages to power lines, water services, government buildings and facilities, school buildings, and learning materials, national roads and bridges, roads and infrastructure, community houses, city tourist destinations, agriculture and livelihood, and medical supplies and healthcare facilities¹ The estimated date for full restoration remained elusive, casting a shadow of uncertainty over the province

Basic utilities lay in disarray The Puerto Princesa City Water District (PPCWD) revealed that all water sources had succumbed to failure due to generator breakdowns The city’s residents, already grappling with the chaos of the storm, now faced the added burden of water scarcity The telecommunications network, a lifeline for information and connection, had crumbled Smart, PLDT, Globe, and Dito had all fallen silent since Odette made its turn to the province. Communications towers and eight fiber optic lines lay severed, cutting off the flow of information between Puerto Princesa and northern Palawan.

In the wake of the devastation left by Odette, Mayor Lucilo Bayron of Puerto Princesa City revealed the city government’s key priorities for 2022. These priorities are predominantly focused on post-typhoon recovery and restoration efforts. During his speech, Mayor Bayron assigned the heads of various city government departments the crucial task of devising recovery plans for sectors severely impacted He called upon the City Planning and Development Office (CPDO) to craft a comprehensive restoration plan, which would involve collaboration with the City Tourism Office to stimulate economic recovery and cooperation with the Agriculture Office and to support affected farmers and fisherfolk

“We need to expedite this City Planning, Agriculture, Veterinarian [for] farmers’ and fisherfolks’ livelihood restoration plan Because we all know that those hit by the typhoon in the north have lost their sources of daily sustenance, and their livestock has gone missing,” Mayor Bayron emphasized

The City Budget and Assessor’s offices were instructed to develop programs aimed at generating revenue or encouraging donations to support the restoration initiatives. Similarly, the Treasurer’s Office and the Social Welfare and Development Office were tasked to meticulously account for all cash and in-kind donations and to properly acknowledge and recognize donors. Mayor Bayron also revealed plans for deputy mayors in the northern minicity halls with backgrounds in agriculture and engineering to be designated. This is to expand the expertise available when addressing the post-typhoon challenges He emphasized the need to expedite projects that were originally slated for 2020 and 2021, as well as to commence those scheduled for 2022 Following his speech, all department heads were convened by the mayor for a meeting on the same day to discuss their respective recovery plans

In the wake of the catastrophic Super Typhoon Odette, the Green Assessment (GA) initiative was born, spearheaded by various organizations that collaborated to assess the extent and severity of the typhoon’s impact This initiative was piloted in Palawan, particularly in critical areas such as the PPSRNP, Cleopatra’s Needle Critical Habitat (CNCH) in Puerto Princesa City, and the greater Cleopatra’s Needle Forest Reserve (CNFR) in the municipalities of Roxas and San Vicente

The GA initiative brought together a coalition of organizations, each contributing their unique knowledge, skills, expertise, and resources, to assess the aftermath The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Philippines Sustainable Interventions for Biodiversity, Oceans, and Landscapes (SIBOL) activity, the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS), DENR Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO), DENR Community Environment and Natural Resource offices (CENRO) in Puerto Princesa City and Roxas, PPSRNP Protected Area Management Office (PAMO), CNCH technical working group, Puerto Princesa City Environment and Natural Resources Office (City ENRO), Puerto Princesa City Disaster Risk Reduction Management Office (CDRRMO), and the local governments of San Vicente and Roxas, joined forces in a collaborative effort to comprehensively determine the typhoon’s impact.

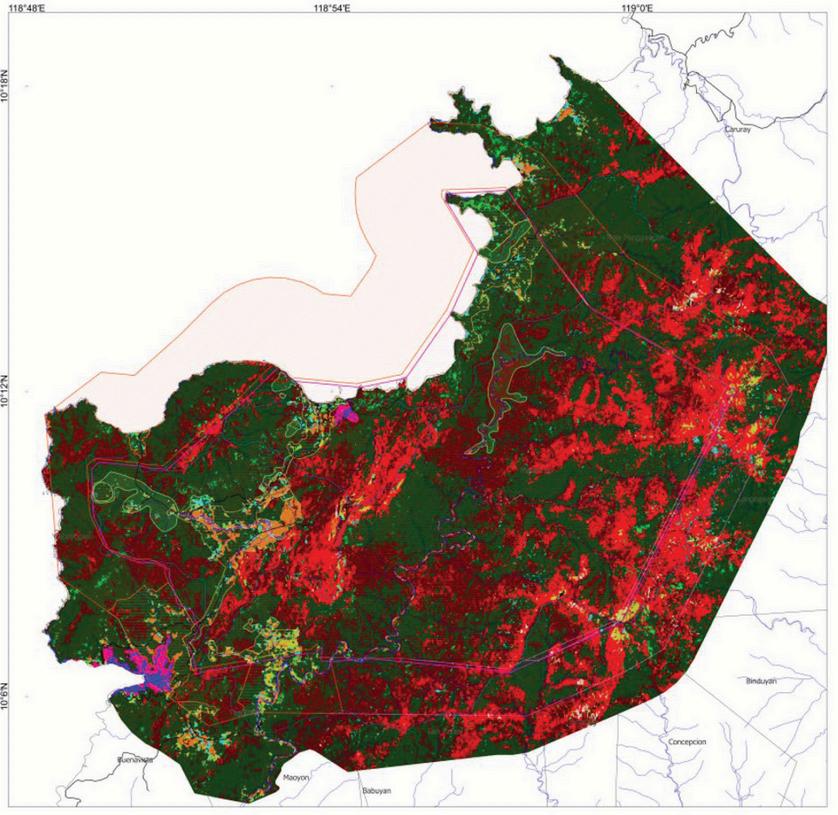

The assessment unfolded into two stages: (1) rapid appraisal; (2) comprehensive assessment; and (3) green reconstruction and resilience planning. The first stage was conducted in January 2022, followed by stage two from March to July 2023 The severity of Typhoon Odette’s impact was visualized using rapid mapping techniques and the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI; Figure 1) The NDVI difference map revealed a stark transformation of the affected landscape, with 96% of dense

The biodiversity assessment recorded a total of 399 species of flora and fauna² in the assessment areas; 261 species were found in PPSRNP alone Globally significant flora species were identified such as Dillenia luzoniensis (kambog), Pandanus simplex (panda), Dipterocarpus grandiflorus (apitong), Agathis philippinensis (almaciga), and Pterocarpus indicus (narra), and globally important faunal species such as the Cacatua haematuropygia (Red-vented cockatoo), Polyplectron napoleonis (Palawan peacockpheasant), Philautus longicrus (Palawan bubble- nest frog), Cuora amboinensis (Southeast Asian box turtle), and Acerodon leucotis (Palawan fruit bat). The assessment also revealed the discovery of new species of plants. Although high species richness was observed, species detection and encounter rates were lower post-Odette due to damaged habitats characterized by fallen and broken trees, defoliated vegetation, and damaged understories

TYPHOON ODETTE DAMAGED MORE THAN HALF OF THE FORESTS

Pre-Odette, PPSRNP was predominantly covered by closed and open forests, constituting 70% of its land cover However, post-Odette assessments revealed that over half of the forests (58%) were damaged, with mid to high-elevation forests being converted into open forests or non-forest areas (Figure 2; Table 1)³ Forest tree species were mostly affected since they act as canopy or roofing over the underlying plants, making them comparatively more susceptible to extreme weather The weight of the trees combined with the horizontal force of the wind created a vertical gravity field during the typhoon, which severely damaged the canopy layer and resulted in the breaking of stems and branches, tearing of bark, and uprooting

²Bautista, M , Abdao, R , Uy, Q , Masigan, J , Edaño, J , Bibar, J , Tablazon, D , Ordinario, J , Mallari,

Figure 1 Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) map depicting the changes in vegetation during pre- and post-Odette events Cloud-free satellite images from available Sentinel 2 images from January 1 to November 30, 2021 (pre-Odette) and December 2021 to February 2022 (postOdette) were used to generate the maps.

PPSRNP: Eco-Disaster Detection Map 2021-2022 Event

Figure 2. Eco-disaster detection map of PPSRNP (2021-2022), showing the land cover and changes (i e damage) post-Odette

Table 1. Post-Odette area calculations of the different land cover types in PPSRNP, and Central and Northern Palawan

ECOSYSTEM SERVICES IMPEDED, COMMUNITY RESOURCES DAMAGED

Typhoon Odette’s impact on ecosystem services was also assessed through community interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), and ground surveys in affected areas. The key findings included unregulated logging as a consequence of the need to clear damaged vegetation, altered flow regulation resulting to water supply insecurity, loss of non-timber forest products (NTFPs), soil erosion leading to river siltation, recurring landslides, and negative impacts to the income of indigenous communities due to damaged honey collection areas The GA stressed the significance of science- based, biodiversity-based, and ecosystem-based assessments to support post-disaster response efforts, such as the implementation of ecological restoration measures in impacted areas

In response to our engagement in implementing the GA, the Green Recovery Plan (GRP) Framework was developed with USAID SIBOL It aimed to establish a collection of strategies and actions intended for repairing damaged ecosystems following climate- induced disasters.

In the wake of the GA presentation on January 6, 2023, four interagency technical working groups (TWGs) were established in Palawan to oversee the validation of the GA results and preparation for the green recovery planning in typhoonaffected areas within their respective purviews. In PPSRNP, the TWG is composed of representatives from the PPSRNP PAMO, DENRCENRO Puerto Princesa City, PCSDS, City ENRO, CDRRMO, and Western Philippines University (WPU) From April 25 to April 27, the GA results were socialized in the PPSRNP barangays Local communities’ stances on how to help reconstruction efforts and manage natural resources post-disaster were acquired through this activity The key recommendations include river rehabilitation, reforestation initiatives, and restoration of damaged NTFP harvest sites The suggestions and ideas gathered from the socialization were compiled and used to initiate the development of the GRP To validate the condition of the forest one year after the typhoon’s devastation, a restoration

catalyst plot assessment was also conducted from April 24 to May 1 Results showed that more than 3,000 regenerants are present in the restoration catalyst plots, but < 20% of the regenerants are considered climax or latesuccessional species About 14 mother trees per plot were observed during the assessment These indicate that most damaged areas have the inherent ability to self-regenerate but additional interventions are needed to increase the diversity during the regeneration process

The construction of the GRP involved examining several restoration typologies that are suitable for post-disaster site conditions based on data gathered from the socialization and restoration catalyst plots. During the course of the workshops, five primary interventions were identified. These include protection; spontaneous natural regeneration (SNR); assisted natural regeneration (ANR); assisted natural regeneration with enrichment planting; and monitoring Protecting the persistent forests is a top priority, followed by promoting natural regeneration, and other planting or revegetation efforts

The post-disaster restoration catalyst framework⁴ was developed to assist in determining appropriate interventions for restoring damaged forests It was designed to complement more established approaches to ecosystem conservation and restoration The framework shows a decision tree to come up with a range of different restoration strategies all the way from spontaneous natural regeneration (SNR), assisted natural regeneration (ANR), enrichment planting, conventional tree planting, protection, and monitoring (Annex A) The highest priority is to protect the existing natural ecosystem, then encourage natural regeneration, and lastly to undertake any planting or revegetation efforts Restoration strategies are not mutually exclusive, they are flexible and adaptable approaches that can be applied in a variety of contexts and combined with protection and monitoring activities to meet specific restoration objectives.

There is no definite end-point in restoration, but the main goal is to support nature-driven processes, which in turn will bring a resilient and sustainable ecosystem closer to its original state

The initial stages in determining the appropriate restoration strategy involved ground validation of the damaged (through fallen and defoliated trees) areas by establishing 1-ha restoration plots and assessing the recovery potential and biophysical conditions. We measured the remaining canopy cover, counted the number of regenerants, and tested the soil for characteristics and nutrients This activity helped us evaluate the level of site degradation and determine the intensity of actions needed to promote the growth of new vegetation or to compete with existing vegetation Based on the information gathered through the data, we determined the appropriate restoration strategies in PPSRNP using the restoration framework

SNR is a hands-off approach that permits the self-organizing process of species colonization to initiate forest restoration and create successional trajectories⁵ . Harnessing the natural regeneration potential will greatly reduce costs and will permit larger areas to be restored. We will apply this strategy in areas where successional species colonize naturally and areas where slope is greater than 50% with elevation greater than 500 m.

ANR is any set of interventions that aim to enhance and accelerate the natural regeneration of native forests5, It involves protecting against disturbances (from fire, stray domestic animals, and humans) and facilitating desired native species of trees by reducing competition (through ring weeding, blanket brushing, pruning, coppicing, etc.) of plants that hinder their growth⁵’⁶ . We will be applying this strategy in areas where the slope is less than 50% with an elevation not exceeding 500 m, where the number of regenerants is more than 800 per hectare to close the canopy, and where the regenerants comprise of at least 30% secondary and climax species. In some areas where applicable, ANR will be enhanced through some form of enrichment planting or treeplanting activities in between the existing natural regenerants. We will apply enrichment planting in areas where canopy closure does not occur due to low density and diversity of native natural regenerants, where late-successional (climax) forest tree species are limited (less than 30%) or not present amongst the natural regenerants, and where the remnant forest is far from the ANR site with only a few seed-dispersing animals

Protection activities in PPSRNP will be done to achieve two twin objectives - threat reduction and maintenance of regenerants We will continue implementing existing protection and enforcement systems to reduce the incidence of threats to biodiversity and ecosystems and other illegal activities Regular foot patrols will be conducted to monitor the status of remaining persistent forests within the national park We will also establish forest lines along the forest edge to deter further expansion of anthropogenic activities in areas with high conservation values Forest lining can be done by erecting signages in strategic locations or by planting forest and fruitbearing trees along the boundaries, with suitable spacing, and in between monuments Based on our experience, social fencing is another protection strategy that we plan to continue doing more of in the next decade We will establish more community-based sustainable tourism (CBST) sites around the park and continue supporting those that are already in place The CBST sites are managed by people’s organizations (POs) that will serve as social fences that will manage and protect the park’s outstanding and universal values in exchange for legitimate access to social and economic benefits.

Our ANR and SNR sites must also be given the same level of care and protection to remove any barriers that will hinder our natural forests from regenerating. We must ensure that successional species will recolonize damaged areas naturally. For ANR, we need to establish fire breaks to prevent the spread of fire This will involve clearing combustible vegetation to block moderate groundcover burns⁵

For SNR, consequent to our threat reduction objectives, we will focus our protection on our key indicator species and their habitats Key indicator species such as the Palawan Hornbill, Fruit Doves, Pigeons, and Bulbuls are seed dispersers These species are essential for dispersing seeds from persistent forests to damaged forests/restoration sites enabling the return of climax forest trees5. Successful forest restoration goes hand in hand with biodiversity recovery.

Monitoring informs the efficacy and impact of restoration activities and allows adaptive management based on feedback data Various monitoring strategies can be used, depending on the site conditions Monitoring approaches include: simple photopoint monitoring; plot-based assessment of the tree seedlings (including natural regeneration and survival of planted seedlings) and measuring the growth rate of these trees; survey of biodiversity recovery; measurement of biomass accumulation; remotely piloted aircraft system monitoring of the changes in vegetation cover; and monitoring of other specific parameters (soil fertility, leaf litter accumulation, soil erosion, presence of wildlife species of interest, phenological studies, socio-economic benefits to the local community, etc )

Our ten-year Green Recovery Plan (GRP) is anchored on the vision, mission, and goals of the PPSRNP Strategic Management Plan 2020 to 20307 We recognize the need to secure key threatened habitats and species in PPSRNP by placing people and ecosystems at the heart of our conservation targets The long-term goal of our GRP reflects the first goal of the Management Plan, which states that “The Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park’s biodiversity and ecosystem are effectively conserved and protected.” Maintaining the ecological integrity of PPSRNP would include the restoration of forest ecosystems that were damaged by the onslaught of Typhoon Odette We envision that natural systems and key species in PPSRNP will recover and continue to thrive in the next decade as a result of our restoration efforts

The GRP is anticipated to be implemented within ten years The goal and success indicators are shown in Table 2

Table 2. The GRP’s long-term goals and their corresponding indicators, means of verification, and external assumptions 11,12,13

Long-term Goal Indicators

1 Increased forest and vegetation cover in damaged areas, and maintained coverage of persistent forests through active and passive restoration

Baselines:

a 7,057 97 ha of remaining persistent forests because of Odette in 2020 ⁸

b At least 25% of the 9,619 34 ha damaged forests⁶ are restored

2 Increased population densities or improved habitat suitability of key indicator species

Baselines:

The ecological Integrity of the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP) is maintained

a EN Palawan Peacock-Pheasant (Polyplectron napoleonis) = local population density (km-2 ± CV) estimated at 5 4 ± 37 in early secondary forests (ESF), 10 8 ± 38 in advance secondary forests (ASF), and 20 3 ± 64 in old growth forests (OGF)⁹

b VU Palawan Hornbill (Anthracoceros marchei) = local population density (km-2 ± CV) estimated at 9 6 ± 38 in early secondary forests (ESF), 13 8 ± 35 in advanced secondary forests (ASF), and 19 6 ± 39 in old-growth forests (OGF)³; global population estimated at 20000-49999

c Suitable habitats of 11 threatened birds and high conservation value species are found in areas with dense forests at low-mid elevations

d Contraction of suitable habitats of the Palawan Peacock- Pheasant and Palawan Hornbill postOdette¹⁴

e Other key species identified by the management plan: Leopard Cat (Prionairulus bengalensis), Palawan Bear Cat (Arctitits binturong), and Barbaroula busuangensis¹⁵

3 Decreased incidence of illegal activities

Baseline: Enforcement reports from foot patrols, threats monitoring, and protection systems

Means

Maps showing detected forest cover change; Results of habitat assessments

Population density estimates of key indicator or High Conservation Value (HCV) species; Suitable habitats or occupancy models of HCV species; Ecological assessments showing species-habitat associations

Low incidence of natural disaster events (landslide, typhoon, flooding, forest fires) that may significantly impact the landscape; Sustained stakeholders support on GRP implementation

Low prevalence of wildlife hunting; Incomplete species detection; Absence of natural disaster events that may have significant impact on species distribution

Records of illegal activities; Spot maps of hotspot areas

Continued support of stakeholders on GRP implementation

⁸Bautista M Uy Q Coroza O Andaya K Abdao R Felismino-Inovejas R Jasmin C Empillo L Batistin R Masigan J Mallari N (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Analysis and interpretation of data and information on the green assessment in Palawan Green assessment in Palawan: stage 2 - data analysis and interpretation

Technical Report 2024 Supported by the USAID

⁹Mallari, N , Collar, N , Lee, D , McGowan, P , Wilkinson, R , Marsden, S (2011) Population density of understory birds across a habitat gradient in Palawan, Philippines: implications for conservation Oryx 45(2) 234-242 doi:10 1017/S0030605310001031

¹

⁰BirdLife International (2024) IUCN Red List for birds Downloaded from http://datazone birdlife org on 16/01/2024

¹¹Masigan, J , Edaño, J , Suetos, K , Abdao, D , Bibar, J , Tablazon, D , Rico, E , Mallari, N (2020) Developing a selection process to identify indicator species In Selecting candidate management indicator species in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park, Report No 2 Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc

¹²Masigan J Edaño J Bibar J Abdao D Parr R Suetos K Felismino R Tablazon D Coroza O Mallari N (2020) Predicting suitable habitats of management indicator species in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park In Habitat evaluation procedure model for the management indicator species and beneficiary life forms, Report No 4 Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc

¹³Center for Conservation Innovation PH [CCIPH] (2021) High conservation value areas in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP) Technical Report, 39 p

¹

⁴Bautista M Uy Q Coroza O Andaya K Abdao R Felismino-Inovejas R Jasmin C Empillo L Batistin R Masigan J Mallari N (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Analysis and interpretation of data and information on the green assessment in Palawan In Green assessment in Palawan: stage 2 - data analysis and interpretation

Technical Report 2024 Supported by the USAID

¹

⁵PPSRNP (2020) The Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP) Managament Plan 2020-2030 version 3 pp 1-76

¹

We recognize that, in order to achieve our vision and long-term goal, a battery of various restoration techniques must be implemented in the next ten years Four short-term goals that are rooted in the restoration catalyst framework were identified in Table 3.

Table 3. The GRP’s short-term goals and their corresponding success indicators, means of verification, and external assumptions

1 Forest cover gains or increased in vegetation cover index

Baselines: a 7,057 97 ha of remaining persistent forests because of Odette in 2020

b Green Assessment Stage 1 Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)¹⁷

2 Increase in growth of regenerants

1 Restore 1,055 25 ha of damaged forest through ANR

2 Strengthen protection and monitoring of persistent and damaged forests

Baselines: ANR RCP results (demo plots)

3 High percent (%) survival of regenerants

Baselines: a ANR RCP results (demo plots) b 9,619 34 ha damaged forests

4 Reduced cover of invasive alien species (IAS)

Baselines:

Exact extent of IAS cover unknown but areas with high concentration of IAS are identified within PPSRNP

1 Increased Coverage of Foot Patrols

Baseline: % monitored based on priority enforcement blocks year 2023

2 Reduced incidence of threats

Baseline: 55 incidence of threats detected for year 2023 from from foot patrols

3 Reduced number of violations

Baseline: 31 apprehensions or arrest were reported for year 2023

4 Increased in forest cover

Baseline: 7,057 97 ha of remaining persistent forests because of Odette in 2020¹⁸

Means of Verification External Assumptions

Maps of detected forest cover change or vegetation indices; Habitat assessments

DBH and height of tagged regenerants (demo plots); Aerial surveys

Survival rate of regenerants; Count of regenerants (pioneer, and climax); Count of mother trees

Presence of invasive alien species; HCV and threats assessment

Varied accuracy of maps produced; Availability of satellite images; Low incidence of natural disasters

Natural decay caused by disaster-related events; Low incidence of natural disasters

Natural decay caused by disaster-related events; Low incidence of natural disasters

High dispersal of invasive alien species

Area covered; Frequency of monitoring

Hotspot maps (threats intensity and scope); Enforcement, violations and monitoring reports

Violation reports; Apprehension data

Maps of forest cover change detection

No security and safety issues

No security and safety issues

No security and safety issues

Varied accuracy of maps produced; Availability of satellite images; Low incidence of natural disasters

⁶Bautista, M , Uy, Q , Coroza, O , Andaya, K , Abdao, R , Felismino-Inovejas, R , Jasmin, C , Empillo, L , Batistin, R , Masigan J , Mallari, N (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Analysis and interpretation of data and information on the green assessment in Palawan Green assessment in Palawan: stage 2 - data analysis and interpretation Technical Report 2024 Supported by the USAID

¹⁷Coroza, O , et al (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Green assessment rapid appraisal in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park and Cleopatra’s Needle Forest Reserve In Green assessment in Palawan stage 1 - rapid assessment Technical Report December 2022 Supported by the USAID

¹⁸Bautista, M , Uy, Q , Coroza, O , Andaya, K , Abdao, R , Felismino-Inovejas, R , Jasmin, C , Empillo, L , Batistin, R , Masigan J , Mallari, N (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Analysis and interpretation of data and information on the green assessment in Palawan In Green assessment in Palawan: stage 2 - data analysis and interpretation Technical Report 2024 Supported by the USAID

²

¹

Table 3. The GRP’s short-term goals and their corresponding success indicators, means of verification, and external assumptions (continuation)

Short-term Goals Indicators

5 Zero incidences of encroachment in persistent forest

Baseline:

a SEAMS data (assessment in progress)

b Puerto Princesa City CLUP

3 Increase abundance of key indicator species

4 Restore 5,144 04 ha of damaged forest through SNR

Increased species detection and occurrence rates

Baseline:

Low occurrence and detection of key species as reported by the GA¹⁹

1 Forest cover gains or increased in vegetation cover index

Baselines: a 7,057 97 ha of remaining persistent forests because of Odette in 2020¹⁵

b Green Assessment Stage 1 Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)²⁰

2 Increase in growth of regenerants

Baselines: a SNR RCP results (demo plot) b 9,619 34 ha damaged forests

3 High percent (%) survival of regenerants

Baselines: a SNR RCP results (demo plot) b 9,619 34 ha damaged forests

4 Increase in occurrence of key indicator species

Baseline:

Low occurrence and detection of key species as reported by the GA²¹

5 Improved condition of Almaciga

Baseline: Results of ongoing Almaciga assessment

Absence of infrastructure in Core Zones; No changes in land use and land cover; No anthropogenic deforestation

Number of individuals per species recorded during monitoring; BMS and BAMS activities

Maps of detected forest cover change or vegetation indices; Habitat assessments

No security and safety issues; Continued support of stakeholders on GRP implementation

Incomplete detection; Absence of extreme natural disaster event

Varied accuracy of maps produced; Availability of satellite images; Low incidence of natural disasters

DBH and height of tagged regenerants (demo plots); Changes in density of vegetation based on aerial surveys or photo-point sampling (outside demo plots)

Survival rate (demo plots); Changes in density of vegetation based on aerial surveys or photo-point sampling (outside demo plots)

High detection rates of indicator species

Natural decay caused by disaster-related events; Low incidence of natural disasters

Natural decay caused by disaster-related events; Low incidence of natural disasters

Incomplete detection; Absence of extreme natural disaster event

Tapping incision, health of individual tree stands

Anthropocentric practices of tapping

⁹Bautista, M , Abdao, R , Uy, Q , Masigan, J , Edaño, J , Bibar, J , Tablazon, D , Ordinario, J , Mallari, N (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Rapid biodiversity assessment in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park and Cleopatra’s Needle Forest Reserve In Green assessment in Palawan stage 2 - comprehensive appraisal Technical Report December 2022 Supported by the USAID, 62 p

⁰Coroza, O , et al (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Green assessment rapid appraisal in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park and Cleopatra’s Needle Forest Reserve In Green assessment in Palawan stage 1 - rapid assessment Technical Report December 2022 Supported by the USAID

²¹Bautista, M , Abdao, R , Uy, Q , Masigan, J , Edaño, J , Bibar, J , Tablazon, D , Ordinario, J , Mallari, N (Center for Conservation Innovation PH, Inc ) Rapid biodiversity assessment in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park and Cleopatra’s Needle Forest Reserve In Green assessment in Palawan stage 2 - comprehensive appraisal Technical Report December 2022 Supported by the USAID, 62 p

Short-term Goal 1 seeks to restore 1,055 ha of the damaged forest through assisted natural regeneration by year 2034 Forest restoration is a long game and it may take us years to recognize any significant results We identified four indicators that will signal the achievement of our goal

Indicator 1.1 Forest cover gains or increase in vegetation cover index:

We will conduct ground-truthing surveys and to carry out these activities effectively habitat assessments to help in a detailed assessment of the land cover in the area Coupled with satellite images available online, maps of detected forest cover change or vegetation indices will be produced to determine the increase in forest cover from the persistent forests

Indicator 1.2 Forest cover gains or increase in vegetation cover index:

Within the damaged areas of the park, regenerating new trees is crucial for rebuilding the forest ecosystem. We will measure the growth of these regenerants, specifically their diameter at breast height (DBH), height, and crown cover, to ensure they are thriving.

Indicator 1.3 Percent (%) Survival of regenerants:

Not only do we aim to help new trees grow, but we also want to ensure their survival We will count both the regenerants and the mother trees, tracking the percentage of regenerants that survive over time Again, the impact of natural disasters on regenerant’s survival is a factor we must consider.

Indicator 1.4 Eliminate invasive species:

Invasive species can threaten the integrity of the park’s ecosystem We will monitor and take action to eliminate these invasive species It is important to note that invasive species can rapidly colonize and take over areas, so this is a critical task

Short-term Goal 2 is strengthening the protection and monitoring of persistent and damaged forests Ensuring the ongoing protection of the park’s forests, both persistent and those that have been damaged, is vital

We will increase foot patrols and monitoring efforts to detect and address potential threats Our performance indicators include reducing the incidence of illegal activities, violations, and encroachment to forest areas We can also gauge our progress by measuring forest cover, monitoring hotspots, and reporting violations and apprehensions However, security issues and natural disasters may impact our ability to carry out these activities effectively

Indicator 2.1 Reduced incidence of threats:

We aim to identify and mitigate threats to the park’s forests This involves creating maps highlighting areas with intense threats and regularly monitoring them This indicator is in line with Goal 1, Objective 2 of our Strategic Management Plan, which states that “By 2030, there is zero anthropogenic deforestation ” We will refer to PPSRNP’s enforcement plan in carrying out activities that will contribute to both the GRP and the management plan.

Indicator 2.2 Reduced number of violations:

To maintain the park’s integrity, we will work to reduce violations and illegal activities within its boundaries. This includes tracking violation reports and apprehensions We will use data reported in 2023 as our baselines (Detection = 55; Apprehension/Arrest made =31; Total Enforcement Effort = 268)

Indicator 2.3 Increased Forest cover:

Monitoring changes in forest cover is essential to understand the progress of restoration efforts We will use maps to show alterations in forest cover over time However, the impact of natural disasters, map accuracy, and satellite image availability may affect this measurement

Indicator 2.4 Zero incidences of encroachment in the persistent forest:

Preventing encroachment into the core zones of the park is crucial We aim to ensure that no infrastructure is present in these areas, land use and cover remain unchanged, and anthropogenic deforestation and damage are non-existent

Short-term Goal 3 is to increase the abundance of key indicator species

Indicator 3.1 Increase in occurrence of key indicator species

The park’s health can be assessed by monitoring the abundance of key indicator species We will track the detection and occurrence rates of these species However, incomplete detection may affect our ability to measure species abundance accurately

Short-term Goal 4 aims to restore 5,144 ha of damaged forest through spontaneous natural regeneration We have a substantial task ahead of us in restoring damaged forest areas, covering over 5,000 hectares This restoration includes efforts to increase forest cover and the growth and survival of regenerating trees. We will also focus on improving the conditions of Almaciga trees, which have been impacted by human activities such as tapping for resin. We will use maps to measure changes in forest cover, track DBH of regenerants, count regenerants and mother trees, and monitor the occurrence of indicator species. However, the impact of natural disasters, map accuracy, satellite image availability, and anthropocentric practices of tapping may affect these restoration efforts

Indicator 4.1 Forest cover gains or increased in vegetation cover index:

See Indicator 1 1 above

Indicator 4.2 Increase in growth of regenerants:

See Indicator 1.2 above.

Indicator 4.3 Percent (%) Survival of regenerants:

See Indicator 1 3 above

Indicator 4.4 Increase in occurrence of key indicator species

See Indicator 3 1 above

Indicator 4.5 Improved condition of Almaciga

Assessment of Almaciga trees and their conditions is ongoing. This indicator will be updated after the assessment.

Based on the land cover change map generated from the results of the green assessment and the restoration catalyst framework, we calculated the target hectarage for each restoration strategy (Table 4) All persistent forests (6,781 22 ha) and mangroves (10 3 ha) fall under the protection target while the damaged areas (Figure 2) were further classified into possible SNR (5,144 04 ha) and ANR (4,220 98 ha) sites All damaged areas with slopes higher than 45 degrees are automatically included in the SNR sites On the contrary, less steep damaged forests within the low-mid elevation areas are considered for ANR and ANR with enrichment planting The annual target for each restoration strategy is listed in Table 5 All persistent forests and mangroves shall be monitored and protected annually while damaged areas will be restored gradually within ten years Areas for SNR are gradually expanding in the first four years, from 20% of the target hectarage until it reaches 100% Targets for ANR and ANR with EP are divided into five years, wherein ANR and ANR with EP activities are implemented within the selected 422 hectares per year

Table 5. Target hectarage per GRP restoration strategy per year

Assisted Natural Regeneration with Enrichment

Planting

The execution of the GRP will require extensive organization of time, manpower, and resources

Achieving this will be a collaborative effort with other agencies throughout the 10-year plan The table below outlines the specific activities that fall under each restoration strategy (Table 6)

Table 6. Activities per GRP Restoration Strategy, offices involved, frequency, and timeline for the 10-year PPSRNP GRP

Spontaneous Natural Regeneration (SNR) Activities

1 Establishment and monitoring of restoration catalyst plots (RCP)

1 1 Identify sites for SNR restoration catalyst plot Plot establishment (2 ha ) Once

1 2 Monitoring of 2 ha SNR restoration catalyst plots (or BAMS permanent plots)

2 1 Photo-point monitoring

2 Monitoring of identified SNR restoration sites

2 2 Monitoring using Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS)

Bi-annual

2 3 Point count for indicator faunal species Annual

3 Ecological assessments

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

3 1 Flora and Habitat assessment (e g , canopy cover, ground cover, etc )

3 2 Faunal assessment (indicator species)

Every five years PPSRNP PAMO, Academe

Every five years PPSRNP PAMO, Academe

ᵃ SNR activities will be implemented in 20% of the total targeted area in the first year

ᵇFor the first five years ANR and ANR with EP activities (e g liberating regenerants ring weeding planting etc ) will be implemented in 422 ha each year (different sites) After year 5, areas subjected to ANR will be monitored for progress Note that the implementation of ANR activities within year 1 does not necessarily equate to 422 ha restored for that year Restoration success under these strategies should only be assessed after year 10

ᶜThe target hectarage for the protection of forests will be the same for each year The park aims to cover all 6,781 ha of persistent forests in our foot patrols, threats monitoring, and enforcement activities However, our protection activities will also extend to areas identified for ANR and SNR

ᵈThe target hectarage for the protection of mangroves will be the same each year

Table 6. Activities per GRP Restoration Strategy, offices involved, frequency, and timeline for the 10-year PPSRNP GRP (continuation)

Spontaneous Natural Regeneration (SNR) Activities

4 Tree Mensuration

Tree species identification and measurement of survival of seedlings and growth (DBH and height)

Every five years

Spontaneous Natural Regeneration (SNR) Activities

1 Special Events, Meetings, and Capacity Development Activities

2 Identify sites for ANR and establishment of ecosystem restoration plots

3 Staking and Tagging Regenerants

1 1 Community consultation

1 2 Training on Seedling/Wildling and Species Identification Once

2 1 Establishment of 2 ha restoration catalyst plots

2 2 ANR Site Selection Once

3 1 Preparation of markers

3 2 Hauling of markers

3 3 Staking/marking

3 4 Geotagging

4 1 Blanket brushing

4 Liberating Regenerants

5 Maintenance of Regenerants

4 2 Understory brushing

5 1 Ring weeding

5 2 Grass suppression

5 3 Mulching

5 4 Thinning

5 5 Sanitation cutting

5 6 Coppicing of live stump

Annual (first five years only)

Monthly for first 3 months, Quarterly up to 2 years, Annual up to 5 years

Monthly for first 3 months, Quarterly up to 2 years, Annual up to 5 years

PPSRNP PAMO, PCSDS, CSO partners, Academe

6 Monitoring of Regenerants

6 1 Monitoring of 2 ha ANR restoration catalyst plots (or BAMS permanent plots)

6 2 Mensuration (measurement of diameter, height, crown, etc ) Bi-annual

PPSRNP PAMO, PCSDS, POs, community members and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, CSO partners, and Academe

Table 6. Activities per GRP Restoration Strategy, offices involved, frequency, and timeline for the 10-year PPSRNP GRP (continuation)

Timeline

ANR Activities with Enrichment Planting (EP)

1 1 Site validation/ Reconnaissance with community members

1 2 Formulation of project plan

1 3 Selection of framework species

1 Special Events, Meetings, and Capacity Development Activities

1 4 Community consultation

1 5 Presentation of project plan to the management board

1 6 Training on nursery establishment and plant propagation

1 7 Establishment of 2-ha ANR with EP restoration catalyst plot

2 Nursery Establishment

PPSRNP PAMO, PCSDS, POs, community members and CSO partners

3 Propagation of Planting Materials

2 1 Site selection for satellite nurseries

2 2 Construction of nursery facilities Establishment in the first year, repairs after three years

3 1 Seed collection

3.2 Wildings collection

3 3 Seed germination

3 4 Care and maintenance of germinated seeds and wildlings

3 4 1 Watering

3 4 2 Fertilizer/ Insecticide/ Pesticide application

3 4 3 Root pruning

3 4 4 Weeding and other maintenance activities

3 4 5 Sorting and grading of planting materials

3 4 6 Hardening off

3 5 Care and maintenance of the nursery facilities

Quarterly up to two years, bi-annual for the remaining years

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

Timeline

Table 6. Activities per GRP Restoration Strategy, offices involved, frequency, and timeline for the 10-year PPSRNP GRP (continuation) Activity

ANR Activities with Enrichment Planting (EP)

4 Development of Planting Plan

5 Site Preparation and Outplanting Activities

4 1 Designing the planting layout

5 1 Site preparation

5 1 1 Tagging and marking of existing regenerants

5 1 2 Understory brushing

5 1 3 Staking and hole digging

5 1 4 Establishment of fireline

5 2 Seedling hauling and transport

5 2 1 Construction of makeshift holding area

5 2 2 Transport of planting stocks

5 2 3 Stacking of seedlings

5 3 Application of organic fertilizer on the soil

5 4 Actual outplanting

6 Maintenance of outplanted stocks and existing regenerants

6 1 Application of fertilizer

6 2 Ring weeding

6 3 Mulching

6 4 Suppression of competing vegetation

6 5 Pruning

7 Monitoring of outplanted stock and existing regenerants

8 Other Assessments

7 1 Geotagging of planted seedlings and regenerants

7 2 Mensuration (measurement of diameter, height, crown, etc )

7 3 Monitoring of 2 ha ANR restoration catalyst plots (or BAMS permanent plots)

8 1 Conduct of phenological studies

8 2 Biodiversity assessment

8 3 Soil assessment

Annual (first five years only)

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, PCSDS, DENR-CENRO, CSO partners, and Academe

Annual (first five years only)

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, PCSDS, DENR-CENRO; POs and CSO partners

Monthly for first 3 months, Quarterly up to 2 years, Annual up to 5 years

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

Geotagging - Annual (first five years only)

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

Every five years

PPSRNP PAMO, DENR-CENRO, PCSDS, POs, CSO partners, and Academe

Table 6. Activities per GRP Restoration Strategy, offices involved, frequency, and timeline for the 10-year PPSRNP GRP (continuation)

Timeline

Protection and Community-related Activities

1 Patrolling and threat monitoring using LAWIN

1 1 Trainers training on conducting LAWIN patrols and data modeling

1 2 Monthly and quarterly LAWIN reports submission

2 Updating of monitoring and enforcement plans

3 Capacitate and strengthen the skills of forest rangers in monitoring and surveillance procedures

4 Conduct paralegal and deputization training for forest rangers

5 Coordination and collaboration with DENR on their monitoring systems

6 Integrate monitoring efforts of existing enforcement units and other agencies with the monitoring/surveillance of areas for restoration

Every 5 years

DENR-CENRO, PPSRNP PAMO

Monthly and quarterly PPSRNP PAMO

Annual PPSRNP PAMO

Once in first year and in fifth year

DENR, PCSDS PPSRNP PAMO

Once in first year and in fifth year DENR, PCSDS, PPSRNP PAMO

Bi-annual DENR, PCSDS, PPSRNP PAMO

Quarterly meetings DENR, PCSDS, PPSRNP PAMO

7 Create a memorandum of agreement (MOA) with private stakeholders on their involvement with restoration activities Once PPSRNP PAMB, private sector partners

8 Establishment of forest lining

9 Conduct of foot patrols

10 Establishment of social fencing through the establishment of new community-based sustainable tourism destinations or sites

Once PPSRNP PAMO, DENR CENRO

Weekly in Marufinas and Cabayugan; and quarterly crosscountry patrols PPSRNP PAMO, POs

Once PPSRNP PAMO, POs, and CSO partners

11 Biodiversity-friendly enterprise activities Regularly until Year 10 PPSRNP PAMO, POs

12 Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) activities

Annual

PPSRNP PAMO, POs, DENRCENRO, PCSDS, and CSO partners

Table 6. Activities per GRP Restoration Strategy, offices involved, frequency, and timeline for the 10-year PPSRNP GRP (continuation)

Monitoring and Other Activities

1 1 BAMS training

1 Monitoring using existing systems (BAMS, BMS)

2 Data capture and database management for restoration

Every 5 years DENR BMB, PPSRNP PAMO

1 2 Conduct biodiversity monitoring surveys on the 10 biodiversity transects Annual PPSRNP PAMO

1 3 Database management and curation Regularly until Year 10

2 1 Development of EarthRanger data model for monitoring Annual

PPSRNP PAMO, DENR

PPSRNP PAMO, CSO partner

2 2 Establishment of individual EarthRanger dashboards Once PPSRNP PAMO, CSO partner

2 3 Training of trainers (TOT) on using EarthRanger Every five years

2 4 Rangers training Every five years

2 5 Capacity Development of Community Members for Citizen Science

Every five years

2 6 Maintenance of EarthRanger dashboard Regularly until Year 10

3 Monitoring and evaluation of conservation interventions and restoration strategies Annual

PPSRNP PAMO, CSO partner

PPSRNP PAMO, CSO partner

PPSRNP PAMO, CSO partner

PPSRNP PAMO, CSO partner

PPSRNP PAMB, PPSRNP PAMO, Academic partners, CSO partners, POs, DENR, PCSDS

The onslaught of typhoon Odette subdivided the large forested areas into fragmented patches. The large continuous forests of PPSRNP became dissected, forming a mosaic of damaged and persistent forests This fragmentation has significant consequences for wildlife conservation since many species require a minimum area of continuous habitat to sustain viable populations Small, isolated forest patches can shrink even further due to edge effects, which makes protection a priority for all forest remnants Subsequently, various restoration strategies can be employed from the forest edges to connect these isolated patches Forest restoration can eventually create 'wildlife corridors', which connect forest fragments, giving the species the necessary security to travel from one forest patch to another These fragments re-linked together have greater conservation value compared to those left isolated Following this principle, initial sites for

restoration were selected as “stepping stones” or islands of restored forests that primarily facilitate the movement of wildlife. These “stepping stones” habitats will promote natural regeneration in the surrounding damaged forests and eventually reconnect the fragments of persistent forests

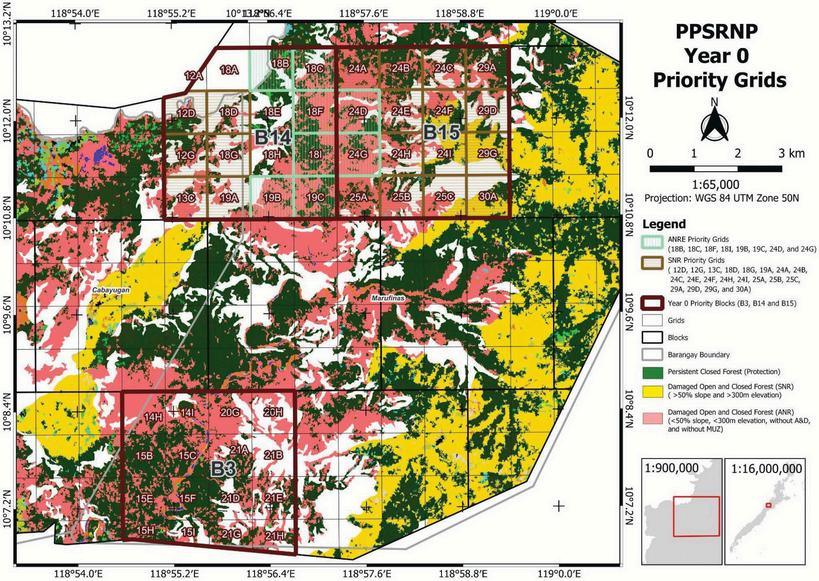

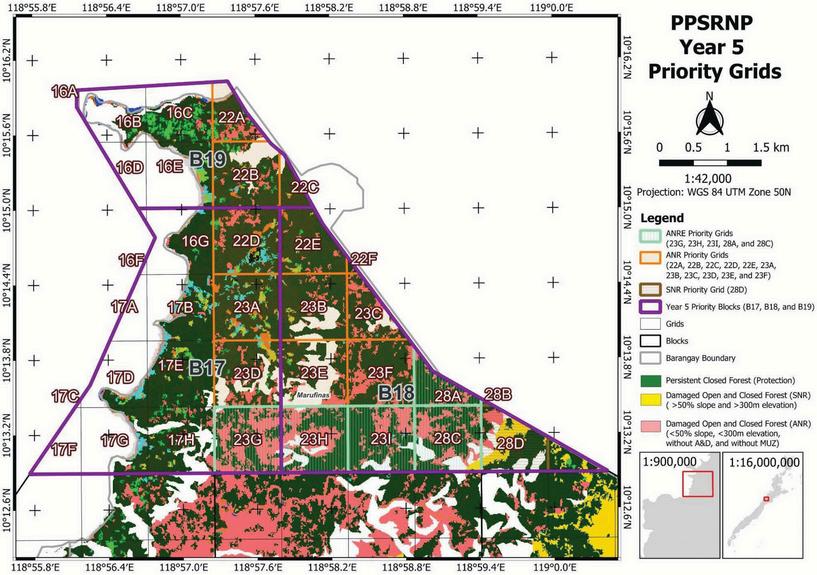

Each year (Year 0 to Year 5) has designated priority areas (i e priority blocks) for restoration A priority block may have more than one restoration strategy, depending on the current condition of the vegetation and topography of the area Figure 3 summarizes the identified priority blocks for Years 0 to 5 Each block (larger square) consists of 16 smaller grids with an approximate size of 100 ha The specific priority areas for restoration from Years 0 to 5 are presented in Figures 4 to 10, including the different restoration typologies assigned per grid

Figure 3. Map of GRP priority blocks for Year 0 to 5

The priority areas selected for Year 0 to 5 are summarized below:

Year 0: Block B3 (Brgy. Marufinas), Block B14 (Brgy. Cabayugan/Sitio Kalaga, Brgy. Marufinas), and Block B15 (Sitio Kalaga, Brgy. Marufinas)

Year 1: Block B1 and Block B2 (Brgy Cabayugan)

Year 2: Block B7 (Brgy Cabayugan)

Year 3: Block B8 (Brgy Cabayugan) and Block B13 (Sitio Sabang, Brgy Cabayugan)

Year 4: Block B6 (Brgy Cabayugan)

Year 5: Block B17, Block B18, and Block B19 (Marufinas)

Year 0 Priority Restoration Areas

Chosen restoration sites for year 0 already have ongoing restoration and rehabilitation efforts initiated by other organizations

Priority grids for SNR:

Block B14 - 12D, 12G, 13C, 18D, 18G, and 19A

Block B15 - 24A, 24B, 24C, 24E, 24H, 24I, 25A, 25B, 25C, 24F, 29A, 29D, 29G, and 30A

Priority Grids for ANR:

Block B3 - All grids

Priority grids for ANR with EP:

Block B14 - 18B, 18C,18F, 18I, 19B, 19C, 24D, and 24G

Figure 4. Map of GRP priority grids for Year 0 Green (Protection) areas represent persistent forests while pink (ANR sites) and yellow areas (SNR sites) correspond to damaged forests

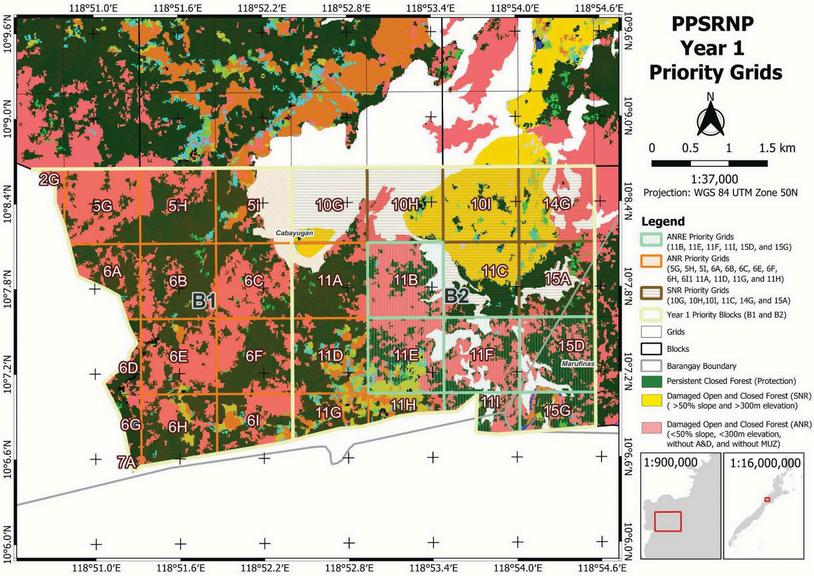

Year one prioritizes damaged areas (Blocks B1, B2) located in Cabayugan (Figure 5). Blocks 1 and 2 have large damaged areas (pink and yellow) adjacent to patches of persistent forest (green). These areas are also prone to human intrusion and anthropogenic activities since they are adjacent to the boundaries of Barangay Tagabinet. Thus, to prevent further degradation and fragmentation of these areas, blocks 1 and 2 are included in the priorities for restoration. Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) will be primarily implemented to restore damaged areas and reconnect them to other forest patches

Priority grids for SNR:

Block 2 - 10G, 10H, 10I, 11C, 14G, 15A

Priority grids for ANR:

Block B1 - 5I, 5G, 5H, 6A, 6B, 6C, 6E, 6F, 6H, and 6I

Block B2 - 11A, 11D, 11G, 11H

Priority grids for ANR-EP:

Block B2 - 11B, 11E, 11F, 11I, 15D, 15G

Figure 5. Map of GRP priority grids for Year 1. Green (Protection) areas represent persistent forests while pink (ANR sites) and yellow areas (SNR sites) correspond to damaged forests

The priority recovery areas (Block B7) for Year two are located in Barangay Cabayugan. As shown in Figure 6, the block contains large persistent forest patches, damaged forests, and persistent croplands (orange). Damaged areas will be restored through ANR or SNR while protection shall be strengthened to avoid encroachment of croplands to damaged and persistent forests.

Priority grids for SNR:

Block B7 - 4E, 9H, 10D, and 10E

Priority grids for ANR:

Block 7 - 4F, 4H, 4I, 5B, 5C, 5E, 5F, 9G, 10A, and 10B

Figure 6. Map of GRP priority grids for Year 2 Green (Protection) areas represent persistent forests while pink (ANR sites) and yellow areas (SNR sites) correspond to damaged forests

Year three priority blocks 8 and 13 are located within Barangay Cabayugan Damaged forests will be restored through ANR (pink) and SNR (yellow) and protection will be strengthened in persistent and damaged forests near Sitio Sabang (B13) Sabang is one of the most accessible areas and considered as the tourist hub of PPSRNP Most of the human activities are concentrated in this sitio, which might contribute to further disturbance and inhibit natural regeneration

Priority grids for SNR:

Block B8 - 10C, 10F, 13E, 13F, 13H, 13I, 14A, 14B, 14C, 14E, and 14F

Priority grids for ANR:

Block B13 - 9C, 12F, and 13B

Priority grids for ANR with EP:

Block B8 - 9F, 9I, and 13D

Block B13 - 8D, 8G, 9B, and 13A

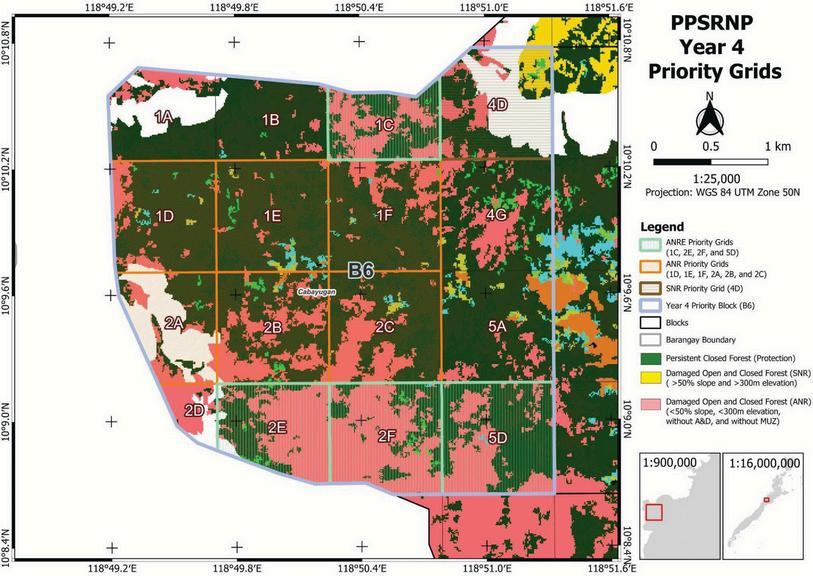

In year 4, damaged forests near the edge of persistent forests in Block 6 will be restored through ANR It is assumed that persistent forests will serve as sources of regenerants and damaged forests near forest remnants can recover faster than other areas Large damaged areas with no or little remnant forest will probably need more help through enrichment planting

Priority grids for SNR: 4D

Priority grids for ANR: 1D, 1E, 1F, 2A, 2B, and 2C

Priority grids for ANR with EP: 1C, 2E, 2F, 5D

Year 5 priority blocks 17, 18, and 19 are all located within the boundaries of Barangay Marufinas The fragmented persistent forest will be relinked through ANR and ANR with Enrichment Planting Damaged forests will be restored gradually to form ‘stepping stones’ and eventually biological corridors for wildlife

Priority grids for SNR:

Block B18 - 28D

Priority grids for ANR:

Block B17 - 22D, 23D, and 23A

Block B18 - 22E, 23B, 23C, 23F, and 23E

Block B19 - 22A, 22B and 22C

Priority grids for ANR with EP:

Block B17 - 23G

Block B18 - 23H, 23I, 28A and 28C

Figure 9 Map of GRP priority grids for Year 5

The costs for restoration vary greatly depending on local conditions, and they increase significantly with the level of damage and degradation Restoring highly-damaged areas might involve enrichment planting, hence nursery costs are included in the budget Aside from this, all restoration strategies require labor during implementation and this determines the maximum area to be restored per year Line-item budgets were calculated per strategy after determining the target hectarage per year (Table 7) A detailed budget breakdown can be found in Annex B

Table 7. Cost per strategy

Monitoring, evaluating, and reporting the results of the GRP will be PPSRNP PAMO’s responsibility This is a critical process as the review will allow us to track our progress and make necessary adjustments in our activities to ensure that our goals are achieved

Each target (refer to Table 5) should be monitored annually The results of the monitoring need to be reported, indicating the accomplishments in a year A review and evaluation of this Plan (GRP) is also required five years after implementation The short-term goals (refer to Table 3) must be reviewed and evaluated to see whether our performances have matched our goals Otherwise, necessary changes should be made to the Plan All results must be documented and reported appropriately

In conclusion, the recovery and restoration plan for the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP) is a comprehensive and ambitious endeavor aimed at rejuvenating and preserving this ecologically vital and culturally significant natural treasure

Our overarching goal is to safeguard the biodiversity and ecosystem within the PPSRNP, ensuring its resilience in the face of natural disasters and human-induced pressures. We aspire to see the park thriving and flourishing, not only for our generation but for future generations to come.

To achieve this vision, we have outlined a meticulous plan that includes increasing forest cover, regenerating damaged areas, strengthening protection and monitoring efforts, enhancing the abundance of key indicator species, and addressing the pressing issue of invasive species. Each of these elements is integral to the park's restoration and long-term sustainability.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this journey is not without its challenges Natural disasters, such as typhoons, can impact our restoration efforts and alter the landscape We must also contend with security issues and varying degrees of map accuracy, all of which can influence our progress

Despite these challenges, we are committed to the cause We have engaged in collaborative conservation efforts, forged partnerships with various stakeholders, and embraced a holistic approach to restoration By working together, we can harness the collective strength and knowledge of our community to protect and preserve the PPSRNP

In the coming years, we envision a PPSRNP that has not only recovered from the impacts of Typhoon Odette but has also become more resilient to future challenges We see a park with increased forest cover, teeming with the diversity of life that makes it so exceptional We envision a place where the persistent forests are safeguarded, and threats are minimized We anticipate a future where key indicator species thrive, a testament to the park's ecological health Moreover, we aim to restore damaged areas, bringing back the lush greenery and natural beauty that defines this national treasure

Our restoration and recovery plan is not just about ecological integrity; it's about preserving the cultural heritage and livelihoods of the communities connected to the park It's about ensuring that the PPSRNP remains a source of pride and wonder for Puerto Princesa and the entire world

As we embark on this journey of restoration, we understand that it will take time, dedication, and collaboration However, with our collective effort and unwavering commitment to the PPSRNP's well-being, we believe that we can overcome the challenges ahead and achieve our vision of a thriving, resilient, and protected national park for generations to come. Together, we will continue to be stewards of this remarkable natural wonder, ensuring that it endures as a symbol of our shared commitment to environmental conservation and sustainability.

Annex A. The Restoration Catalyst Framework

Table B1. Summary costs per budget item (total and per year)

Table B2. Cost per hectare for each budget item, per typology

Table B3. Government counterparts per cost category

Table B4. Percent Share of total costs (per typology, per budget item)