51

SCIENTIFIC E THIC S A S SEEN IN LITER ATURE Humberto Orígenes Romero Porras holds a degree in history from the Universidad de Guadalajara. A former Paralympic athlete (2006-2017), he won a medal at the 2015 Parapan American Games held in Toronto, Canada. A partisan of worthy causes, he is interested in the interconnections between history, literature, and soccer.

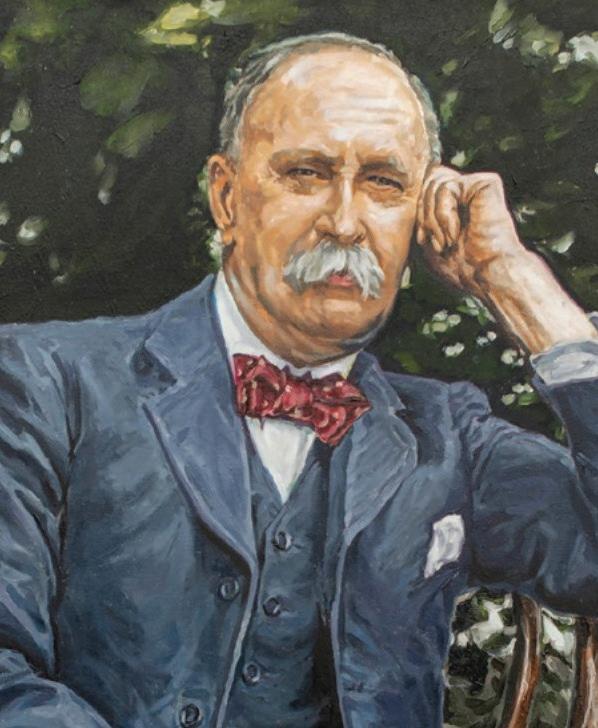

Two classic works of English literature have plots that turn on the ethical dilemma of a scientist: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), by Mary Shelley, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), by Robert Louis Stevenson. In both works, the experiments of a man of science escape his control. Ambition consumes the creator, who is confronted by his own creation.

So important is the connection between the two that Daniel Balderston considers the author of Treasure Island a shadowy precursor of the South American writer.2 The twenty references to Stevenson in the complete works of Jorge Luis Borges, most of them in forewords to various books, bear witness to this devotion.3 In a remarkable tribute to the duality of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Borges transforms himself into a character out of Stevenson, incapable of distinguishing between one Borges and another. “Borges y yo” ends with the words: “I don’t know which of the two of us is writing this page.”

About a week has passed, and I am now finishing this statement under the influence of the last of the old powders. This, then, is the last time, short of a miracle, that Henry Jekyll can think his own thoughts or see his own face (now how sadly altered!) in the glass. Meanwhile, the creation detests his creator, a motif he shares with the monster in Shelley’s novel: The hatred of Hyde for Jekyll, was of a different order. His terror of the gallows drove him continually to commit temporary suicide, and return to his subordinate station of a part instead of a person… Like Dr. Frankenstein, Jekyll confesses to the crime of having played at being God. Both of them regret the harm their experiments might have done to humanity.

REVIEW

“I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typefaces, etymologies, the taste of coffee, and the prose of Stevenson,” wrote Borges in “Borges y yo.”1 The relationship between the Argentinian poet and the Scottish novelist was deep, the latter being described by the former as “a certain very dear friend that literature has given me” in the foreword to Elogio de la sombra.

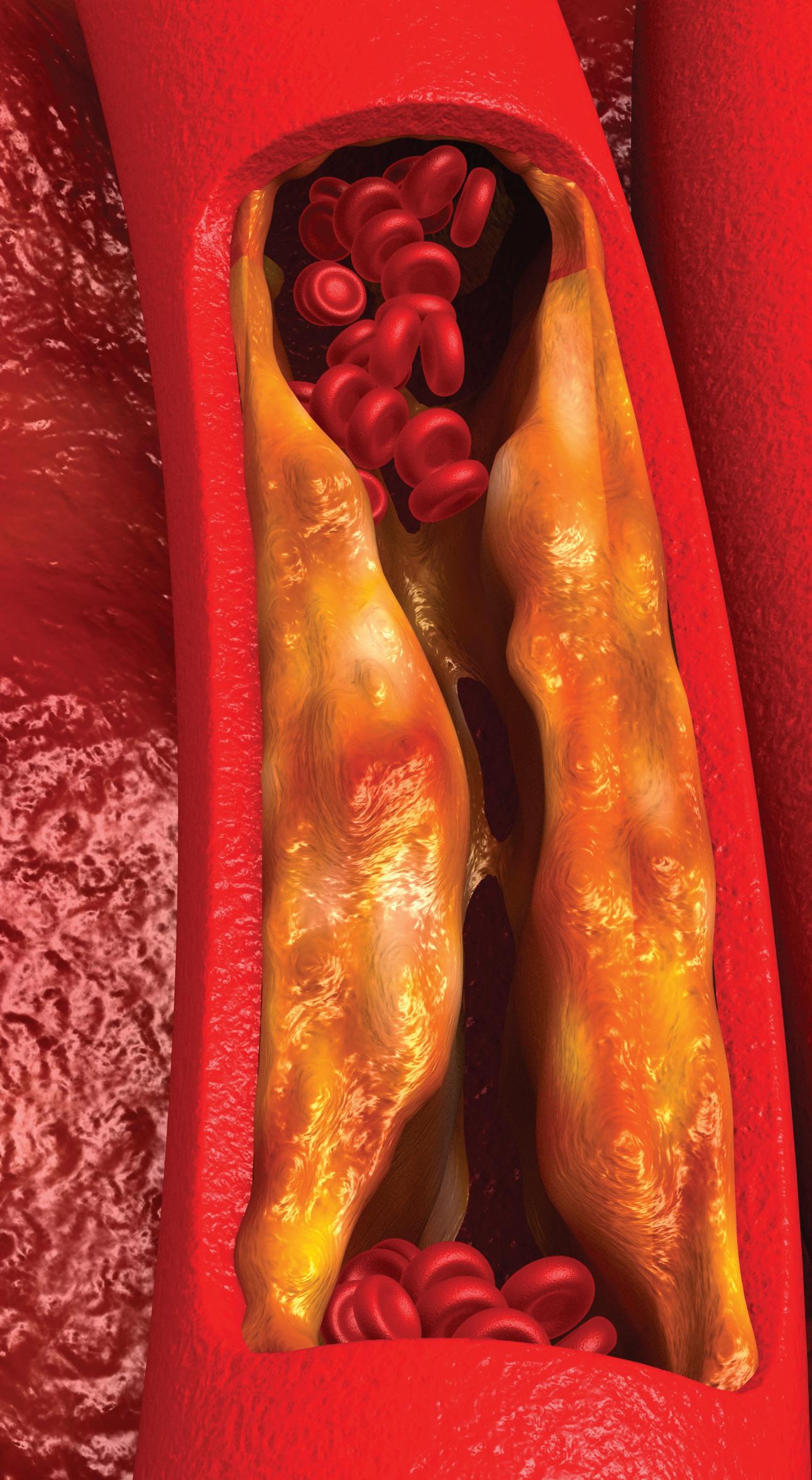

Stevenson’s tale can function as a detective story, beginning as it does with a lawyer looking into the relationship between the sinister Mr. Hyde and his friend Henry Jekyll, a reputable doctor, whose house has been occupied by Edward Hyde, and ending with Dr. Jekyll’s own account of the events. Jekyll was attempting to create a substance that would separate the evil from the good in each individual. It was an experiment in the spirit of the times,4 Mary Shelley having already dealt with the theme of the manipulation of the spirit as a scientific aspiration. Dr. Jekyll becomes fused with his own creation: