4 minute read

SCIENTIFIC ETHICS AS SEEN IN LITERATURE

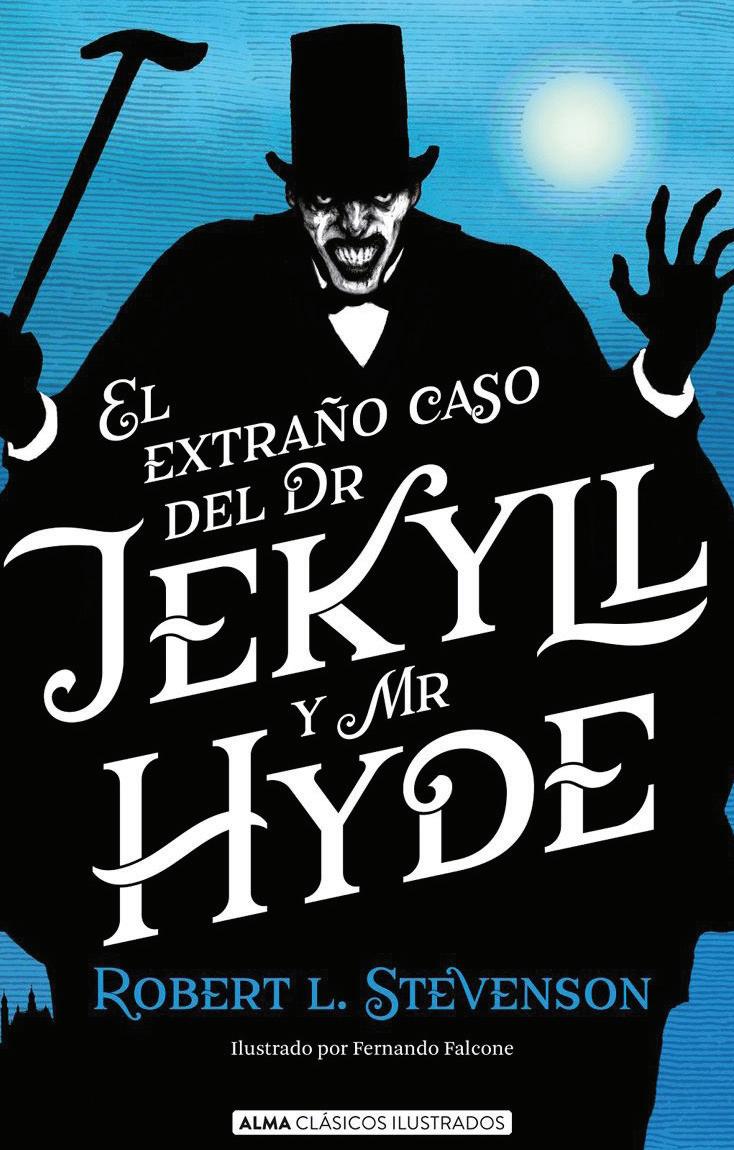

Two classic works of English literature have plots that turn on the ethical dilemma of a scientist: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), by Mary Shelley, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), by Robert Louis Stevenson. In both works, the experiments of a man of science escape his control. Ambition consumes the creator, who is confronted by his own creation.

“I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typefaces, etymologies, the taste of coffee, and the prose of Stevenson,” wrote Borges in “Borges y yo.”1 The relationship between the Argentinian poet and the Scottish novelist was deep, the latter being described by the former as “a certain very dear friend that literature has given me” in the foreword to Elogio de la sombra.

Advertisement

So important is the connection between the two that Daniel Balderston considers the author of Treasure Island a shadowy precursor of the South American writer.2 The twenty references to Stevenson in the complete works of Jorge Luis Borges, most of them in forewords to various books, bear witness to this devotion.3

In a remarkable tribute to the duality of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Borges transforms himself into a character out of Stevenson, incapable of distinguishing between one Borges and another. “Borges y yo” ends with the words: “I don’t know which of the two of us is writing this page.”

Stevenson’s tale can function as a detective story, beginning as it does with a lawyer looking into the relationship between the sinister Mr. Hyde and his friend Henry Jekyll, a reputable doctor, whose house has been occupied by Edward Hyde, and ending with Dr. Jekyll’s own account of the events. Jekyll was attempting to create a substance that would separate the evil from the good in each individual. It was an experiment in the spirit of the times,4 Mary Shelley having already dealt with the theme of the manipulation of the spirit as a scientific aspiration. Dr. Jekyll becomes fused with his own creation:

About a week has passed, and I am now finishing this statement under the influence of the last of the old powders. This, then, is the last time, short of a miracle, that Henry Jekyll can think his own thoughts or see his own face (now how sadly altered!) in the glass.

Meanwhile, the creation detests his creator, a motif he shares with the monster in Shelley’s novel:

The hatred of Hyde for Jekyll, was of a different order. His terror of the gallows drove him continually to commit temporary suicide, and return to his subordinate station of a part instead of a person… Like Dr. Frankenstein, Jekyll confesses to the crime of having played at being God. Both of them regret the harm their experiments might have done to humanity.

Illustrated by Fernando Falcone

Will Hyde die upon the scaffold? or will he find courage to release himself at the last moment? God knows; I am careless; this is my true hour of death, and what is to follow concerns another than myself. Here then, as I lay down the pen and proceed to seal up my confession, I bring the life of that unhappy Henry Jekyll to an end.

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, who took the name of her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, wrote Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in Switzerland, while travelling in the company of Shelley and Lord Byron in 1818. The title itself contains the metaphor: a scientist who, like the Greek Titan Prometheus, defies the gods. Shelley’s work is in accord with the science of her day: “The event on which this fiction is founded has been supposed, by Dr. Darwin, and some of the physiological writers of Germany, as not of impossible occurrence,” she wrote, in the preface to Frankenstein.

The Darwin referred to is not Charles, but his grandfather Erasmus, whose experiments in galvanism provided the basis for Shelley’s novel, in which Frankenstein’s monster is brought to life by means of electricity, as the Italian scientist Galvani proposed. The monster develops a deep hatred for Dr. Frankenstein, owing to his condition as an “Adam without a mate,” as José de la Colina5 has put it. The monster asks its creator for a companion, which is created, before being destroyed by the scientist, who immediately regrets his work.

Shelley’s novel, which actually begins in medias res, with Dr. Frankenstein pursuing his creation across the Antarctic, deals with themes such as good and evil, the fear of solitude, and scientific irresponsibility. Victor Frankenstein, a scientist eager for recognition, joins together fragments of corpses in order to achieve one of science’s greatest dreams: the creation of life. But it all gets beyond his control, for, as the Mexican biologist Antonio Lazcano has accurately expressed it: “Electricity is no substitute for the soul.”6

1. In El hacedor (1960).

2. Daniel Balderston, “El precursor velado: R. L. Stevenson en la obra de Borges.” Available online at <http://www.borges.pitt. edu/bsol/dbi.php>.

3. Jorge Luis Borges, Obras Completas (Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1984 [1974]).

4. See the lecture “¡Frankenstein (y la biología)!” by Dr. Antonio Lazcano Araujo, available online at <https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=-UkxZLuPozw>.

5. José de la Colina, “La Mamá del Monstruo de Frankenstein,” Letras Libres (Mexico City), May 2012. Available online at: <https://www.letraslibres.com/mexico-espana/la-mama-delmonstruo-frankenstein>.

6. Lazcano Araujo, “¡Frankenstein (y la biología)!” cited above.

Humberto Orígenes Romero Porras

holds a degree in history from the Universidad de Guadalajara. A former Paralympic athlete (2006-2017), he won a medal at the 2015 Parapan American Games held in Toronto, Canada. A partisan of worthy causes, he is interested in the interconnections between history, literature, and soccer.