5 minute read

ON ETHICS AND CLINICAL RESEARCH

The development of technology and new medical treatments undoubtedly involves all members of the community, not only medical researchers, doctors and nurses, and other hospital staff, but also society in general.

The unquestioned need of human beings to overcome physical pain or mental suffering and to prolong life drives a continual search for treatments that can help us bear both the physical ailments themselves and the anguish and uncertainty that often accompany them. Sometimes a sense of desperation, caused by ignorance and lack of knowledge of our illnesses, makes us rush our decisions and even to commit injustices and abuses against others. How can we avoid seeking to benefit a loved one or ourselves over the interests and benefits of our fellow human beings? How can we render justice in society where medical treatment is coveted and expected by millions and yet available only to a few? How can we develop new therapeutic options without hurting those less fortunate than us along the way?

Advertisement

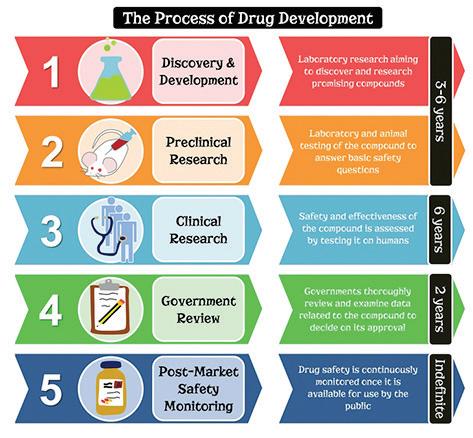

The development of new treatment options, especially drugs, designed to address doctors’ questions that remain unanswered, requires the investment of millions of dollars over very long periods of time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Source:https://portal.unidoscontraelparkinson.com/medicamentos-parkinson/1639-parkinson-farmacosnuevos.html

There are two primary objectives that must be demonstrated in the development of any new treatment: the efficacy of the treatment and its safety. This means that it will not only help to solve or mitigate some medical issue, but also not cause harm to the people who are going to receive it. In other words, it must be demonstrated that any risk of receiving a new drug is clearly offset by the benefit caused to those affected.

But how do you prove the safety and effectiveness of a new medical treatment? The best way to do this is through clinical research studies, which require the participation of expert physicians and of patients suffering from a given unresolved medical condition.

This kind of research demands a large investment of both money and human resources. It is normally financed by the international pharmaceutical industry and/or academic medical institutions which, through medical groups and specialized care clinics, work to develop the research protocols around the world.

The medical specialists who collaborate on these development projects invite patients suffering from the condition in question to receive the treatment under investigation and to allow themselves to be surveilled during the time established in the project. In this way, doctors collect information from patients all over the world, under strict quality standards, which then allows developers to draw valid conclusions about whether a medical treatment is effective or not and ―no less important― whether it is safe or not. Before initiating a clinical research protocol, the country’s regulatory and health authorities must review documentation that describes the intentions of the research and that allows them to determine a) whether there is sufficient medical data to justify research on human subjects, and b) whether there are any other treatment alternatives with which the benefits and potential harms proposed by the research in question might be compared.

This is where the ethical principles of “beneficence and non-maleficence” strictly apply, making it possible to determine whether the treatment in question has the objective of benefiting the patient without causing harm or, as we have expressed it above, whether the benefits outweigh the risks.

Each country has its own system for reviewing and authorizing research protocols. In general, with small variations, this consists of a research committee, normally located in the health institution that will carry out the clinical trial, whose main objective is to validate the scientific purpose of the project, ensuring that its approach is consistent with the medical and scientific knowledge available at the present time.

There is also a research ethics committee, or simply ethics committee, which ensures that the rights of the patients participating in the research are respected and that the project information given to each one of the participants is complete and understandable, allowing them to make an informed decision about whether or not to participate in the study, so that their human rights are in no way violated.

The process of reviewing and authorizing a clinical research project can take between two months and a year (or sometimes even longer), depending on the efficiency of the process and the variants considered in the review by the various agents, simultaneously or sequentially.

In order to harmonize the activities of global pharmaceutical development, in 1996 the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) was established to draw up guidelines for good practices in the manufacture, distribution, and development of pharmaceutical products for human use, with the collaboration of the European countries, the United States, and Japan. The E6 guide, revised in 2016, deals with, among other things, clinical research protocols and the participation of medical specialists (known as clinical investigators) and of their patients as participants in the research. It makes clear that participation in a research project is voluntary, that individuals may not be compelled to participate in any way (or encouraged through payments or other benefits), and that they may stop participating at any time, without detriment to their health care.

No medical discovery or need for treatment justifies an assault on a person’s integrity or freedom of decision. A person should not be pressured to participate in a research project on the premise that it is the only available treatment option for his or her condition. What we in the medical and research professions must do, within an ethical, humanistic, and scientific framework, is to provide all available information about the new treatment, both risks and benefits, and let the person decide whether to participate in the research or not. This decision should be free and voluntary.

The physician treating a patient, when inviting him or her to participate in a clinical research project, should think of the benefit to the patient and consider that the center of the decision, rather than the scientific knowledge in itself. The premise primum non nocere, which means “first to do no harm,” attributed to Hippocrates, should always be considered in scientific research. This will ensure that any medical research procedure has as its main purpose the benefit of those affected by it, with the certitude that we will not harm their physical, mental, or social integrity more than the disease itself has already done.

Dr. Guillermo Caletti, Ph.D.

Chief of Clinical Operations at Boehringer Ingelheim for Mexico and Central America.