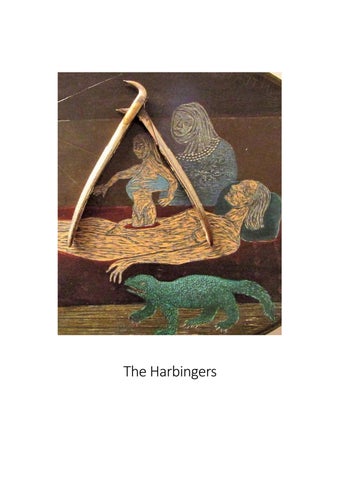

The Harbingers

The Interior (with fish), Birthing Trays Stitched and The Harbingers and Parturient are part of a project entitled The Interior that artist Christine Dixie began in 2005, when she was pregnant with her second child. The project integrates cartographic, religious, and medical references to unsettle established understandings of maternity.

In this most recent iteration, the original objects and prints have been re visited and reconfigured through additions of objects, or they have been stitched onto or drawn and painted over. The compulsion to revisit this work years later, as the children that she birthed are now leaving home, has allowed for the accumulation of traces and a shift in meaning.

At the time of the original iteration Prof. Brenda Schmahmann wrote “Dixie situates her experiences against Western discourses, especially images from early modern Europe. Focusing on the ways in which visual representations construct woman as ‘other’, Dixie invokes reference to not only representations of birth and maternity but also religious, medical, and geographical images. While the gendered underpinnings of these discourses are not always immediately transparent when they are kept discrete from one another, they become evident when they are invoked simultaneously, and Dixie’s works reveal that they are in fact mutually reinforcing agents and indeed often use related tropes. Dixie destabilises their authority not only by challenging their discreteness, however, but also, and even more crucially, by introducing motifs that interfere with their meanings. These additions to, or substitutions for, the imagery in the discourses to which she refers are markers of both a female subjectivity and a postmodernist feminist voice that sees ‘otherness’ as a potential position of strength a place from which to subvert and transgress gendered norms and understandings.” (Schmahmann 2007, 25)

Essays on this body of work include:

Schmahmann, B. 2009. Into the Breach: Christine Dixie’s Birthing Tray Honey in Taking a Hard Look: Gender and Visual Culture. London, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Schmahmann, B. 2007. Figuring Maternity: Christine Dixie’s Parturient Prospects Johannesburg, de Arte 75

Von Veh, K 2014. Deconstructing Dogma: Transgressive Religious Iconography in South African Art Johannesburg, de Arte 89

The Interior (with Fish)

Collection: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Museum Linocut, woodcut, latex, stitching, fish, 3 470 x 3 000 cm

The Harbingers

9 works in the series

Painting onto woodcuts with embedded medical instruments, 400 x 280 mm

Birthing Trays Stitched

Collections: Fowler Museum, UCLA ; UNISA Art Gallery, Pretoria 9 works in the series

Digital Prints with stitching and drawing, 830 x 540 mm

Parturition

Collection: The Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Museum 5 works in the series woodcut on silicone, found objects and electrical light, 900 x 470mm

The Interior (with fish)

Made from prints on rice paper which has been covered in latex, the elements constituting The Interior are positioned in such a way that they accord with a map of Africa by G. Blaeu that was included in the Grooten Atlas (1648 1665). Dixie’s choice of a map by Blaeu is significant. Maps such as the one Dixie quotes here speak of an imperative to harness new topographical knowledge for the successful establishment of the commercial interests of the Dutch East India Company. Signifying the end of the speculative geography that had been a feature of the sixteenth century, the seventeenth century map ‘laid claims to its presence as a studiedly transparent image of an increasingly known world’ (Brotton 1997, 186). Dixie has, however, collapsed her reference to Blaeu with a second discourse one that involves another kind of mapping. Presented as a substitute for the African continent, but adapted to accord with its contours, a medical diagram forms the central motif of The Interior. But this is no general map of the body, and instead one of an especially mysterious physiognomic terrain female reproductive organs. The geographies of dark Africa and female reproductive anatomy have thus both, as it were, been charted and supposedly fixed through geographical and medical inquiry: as Dixie’s juxtaposition of these two discourses makes clear, to a masculine scientific imagination it seemed that the equally troublesome uncertainties signified by both of these ‘others’ foreign topography and woman might be overcome by their being methodically diagrammed. In The Interior, Dixie also reveals how an exploration of the dark mysteries of female anatomy becomes one in which scientific and libidinous imperatives are intricately fused. (Schmahmann 2007, 27)

Map of Africa by G. Blaeu

Details from The Interior(with fish)

Map of Africa by G. Blaeu

Details from The Interior(with fish)

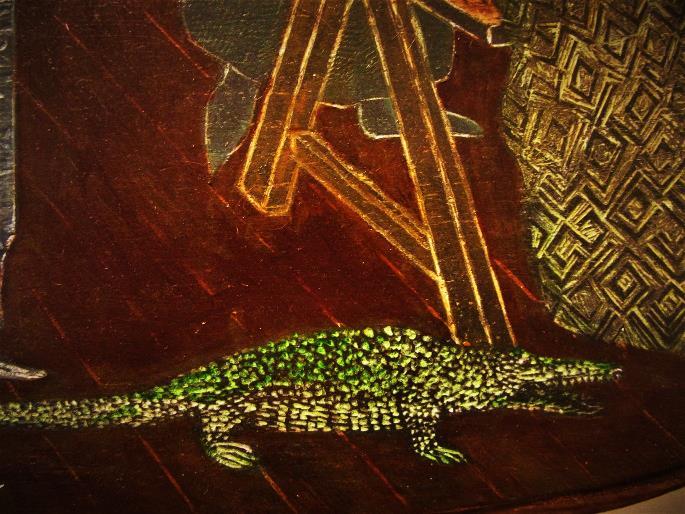

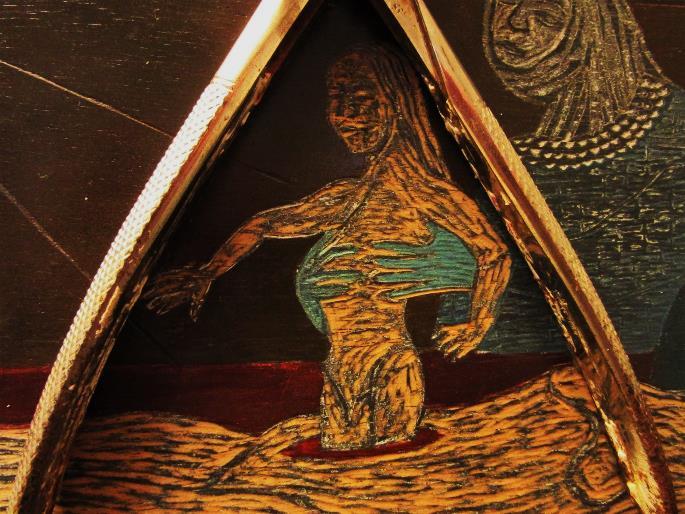

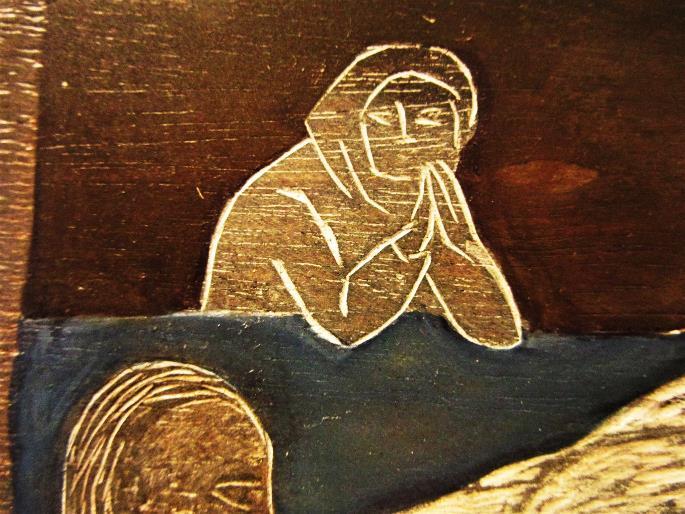

The Harbingers

“At the top of Blaeu’s map are nine roundels depicting harbours, spaces at which the explorer might arrive beforeproceeding on a journey to an unmapped interior, and which thus mark the threshold between known and unknownworlds. Dixie substitutes these images of harbours with scenes derived from early modern representations of labour and delivery, thus pointing to a concept of birth as one in which the child undergoes passage between the mysterious and atavistic interior of the mother’s body and the ‘civilized’ world.” (Schmahmann 2007, 31)

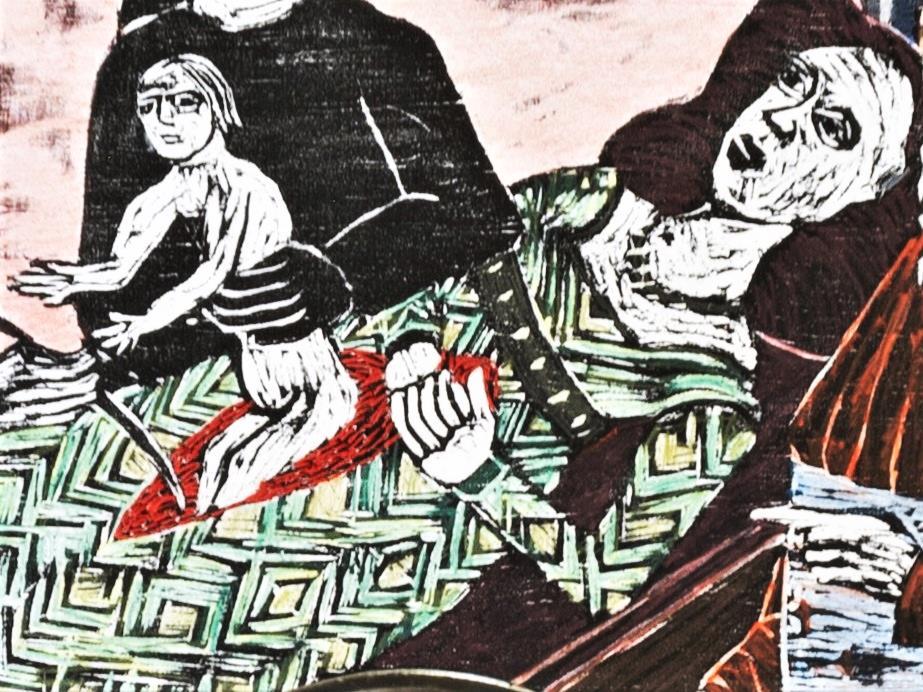

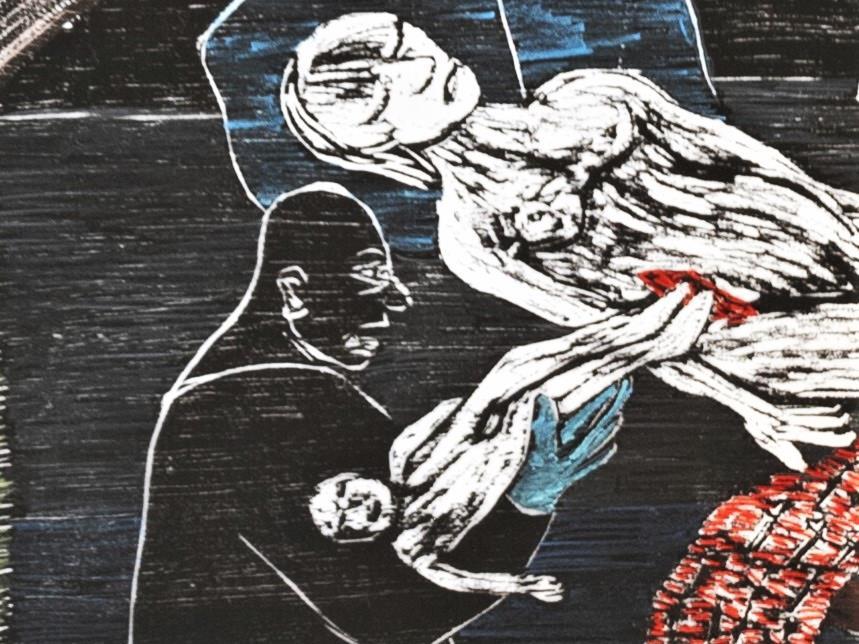

The woodblocks in The Harbingers are cut into the shape of the roundels depicted in the map, with writing which names the source of the fourteenth century image carved into the sides. Each have a medical instrument embedded into the wood. The medical objects interact with the scenario depicted, echoing the shape of an elephant’s trunk, bow an arrow or the splayed legs of the mother who is being operated on. The interior scenes which focus on the scenes of labour also include reference to objects such as the sextant, used for navigation, or views of ships out at sea. These refences to discourses associated with expedition and discovery underscore the exclusion of women from these historical events and act to reinforce the gendered norms played out in the birth process.

The harbours depicted in G. Blaeu’s map name some of the major trading ports of that era Tanger, Cevta, Alger, Tunis, Alexandria, Mina, Mozambique and Canaria The titles of the works directly refer back to these harbours but in addition close the semantic gap between harbour and harbinger. Harbinger derives from the word harbour and speaks of harbouring a person or an emotion.The Death, Dread, Ruin, Decay and Carnage refered to in the titles of eight of the works allude both to the destruction that came in the wake of the ‘civilizing’ mission that cartographic maps like these heralded and simultaneously to the medical discourse around caesarean births that became the site for a gendered struggle within the field of medicine.

The ninth woodblock, The Void Equinoctalis, makes more overt reference to the Map of Africa by G. Blaeu. The detail of this map which focus’s on the Atlantic Ocean and the Equator, the line which marks the divide between north and south becomes a focal point for the work and a comment on the North/South divide which continued to structure the Enlightenment project. The Caliper, used for measuring diameter, lies like a medical instrument across the image and echoes the medical instruments embedded into the other eight woodcuts.

Detail

Detail of The Harbinger of Eternal Death in Tanger

Detail of The Harbinger of Eternal Death in Tanger

The Harbinger of Shadows in Cevta The Birth of the Virgin

Detail of The Harbinger of Shadows in Cevta

The Harbinger of Shadows in Cevta The Birth of the Virgin

Detail of The Harbinger of Shadows in Cevta

The Harbinger of Decay in Alger The Birth of the Virgin

Detail of The Harbinger of Decay in Alger

The Harbinger of Decay in Alger The Birth of the Virgin

Detail of The Harbinger of Decay in Alger

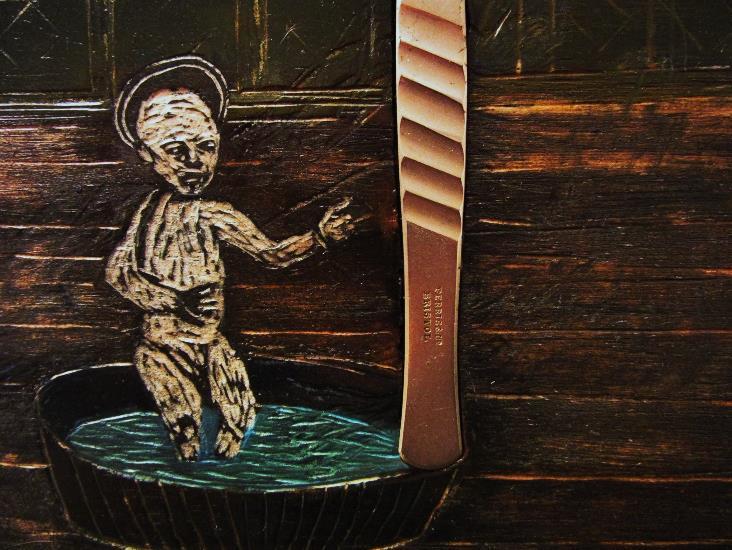

The Harbinger of Dread in Tunis The Birth of John the Baptist

Detail of The Harbinger of Dread in Tunis

The Harbinger of Dread in Tunis The Birth of John the Baptist

Detail of The Harbinger of Dread in Tunis

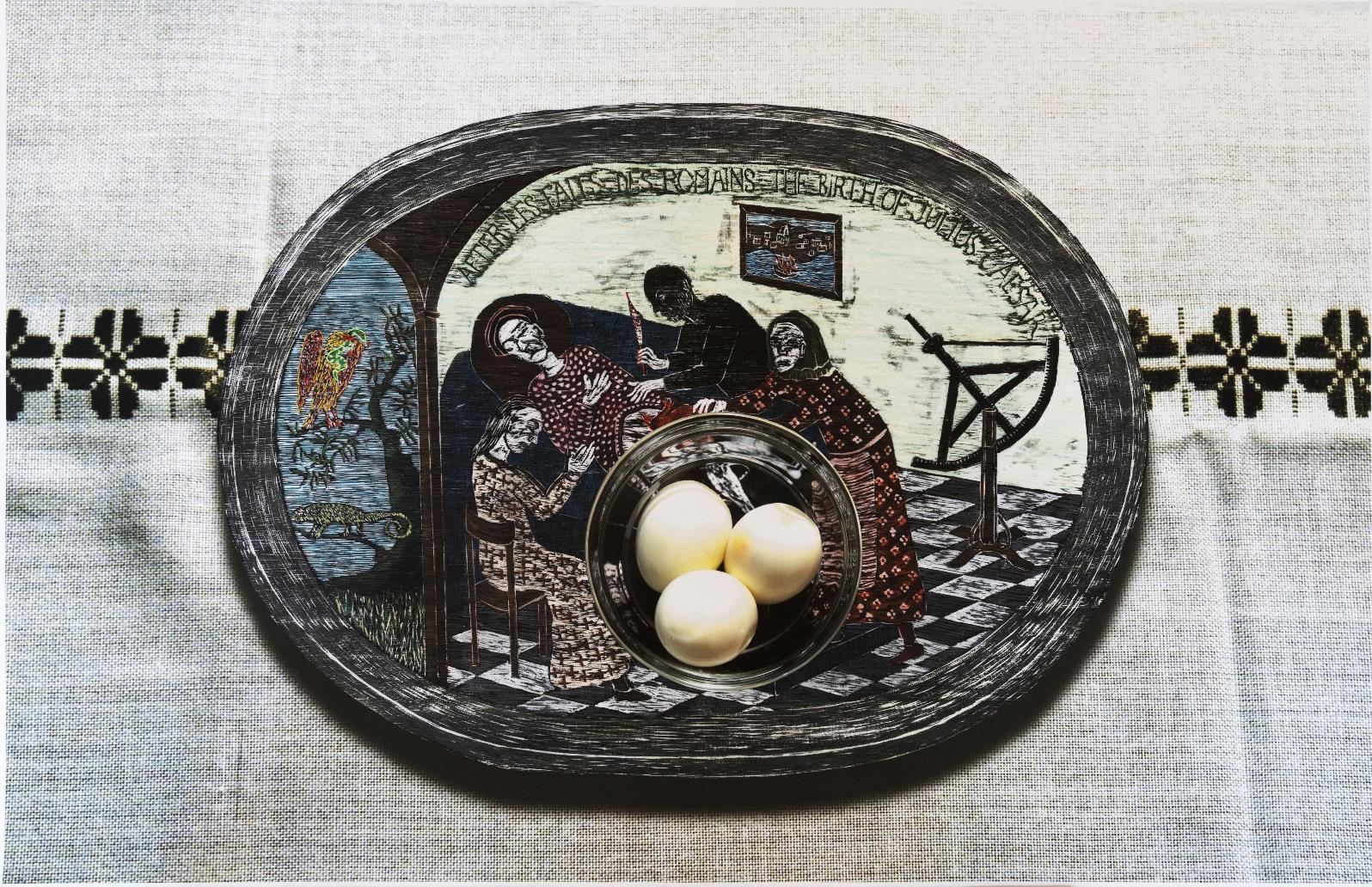

The Harbinger of Ruin in Alexandria The Birth of Julius Caesar

Detail of The Harbinger of Ruin in Alexandria

The Harbinger of Ruin in Alexandria The Birth of Julius Caesar

Detail of The Harbinger of Ruin in Alexandria

Detail of The Void Equinoctialis

Detail of The Void Equinoctialis

Detail of The Harbinger of Carnage in Mina

Detail of The Harbinger of Carnage in Mina

Detail of The Harbinger of Chaos in Mozambique

Detail of The Harbinger of Chaos in Mozambique

Detail of The Harbinger of Desolation in Canaria

Detail of The Harbinger of Desolation in Canaria

Birthing

Birthing

Birthing Tray Stitched Fish

Birthing Tray Stitched Fish

Birthing

Birthing

Birthing

Birthing

Birthing Tray Stitched Mussels

Birthing Tray Stitched Mussels

Birthing

Birthing

Birthing Tray Stitched Water

Birthing Tray Stitched Water

Birthing

Birthing

Birthing Tray Stitched Wishbone

Birthing Tray Stitched Wishbone

“Electrical illumination of each ‘reliquary’ performs a similar function: while red light conveys a sense of the mystical glow of candlelight in sacred shrines, white light is suggestive of a surgical theatre. Wording carved on the base of each object, likewise, offers a conflation of the religious and the medical. (Schmahmann 2007, 36 )

Parturition Vestibule

Parturition Vestibule