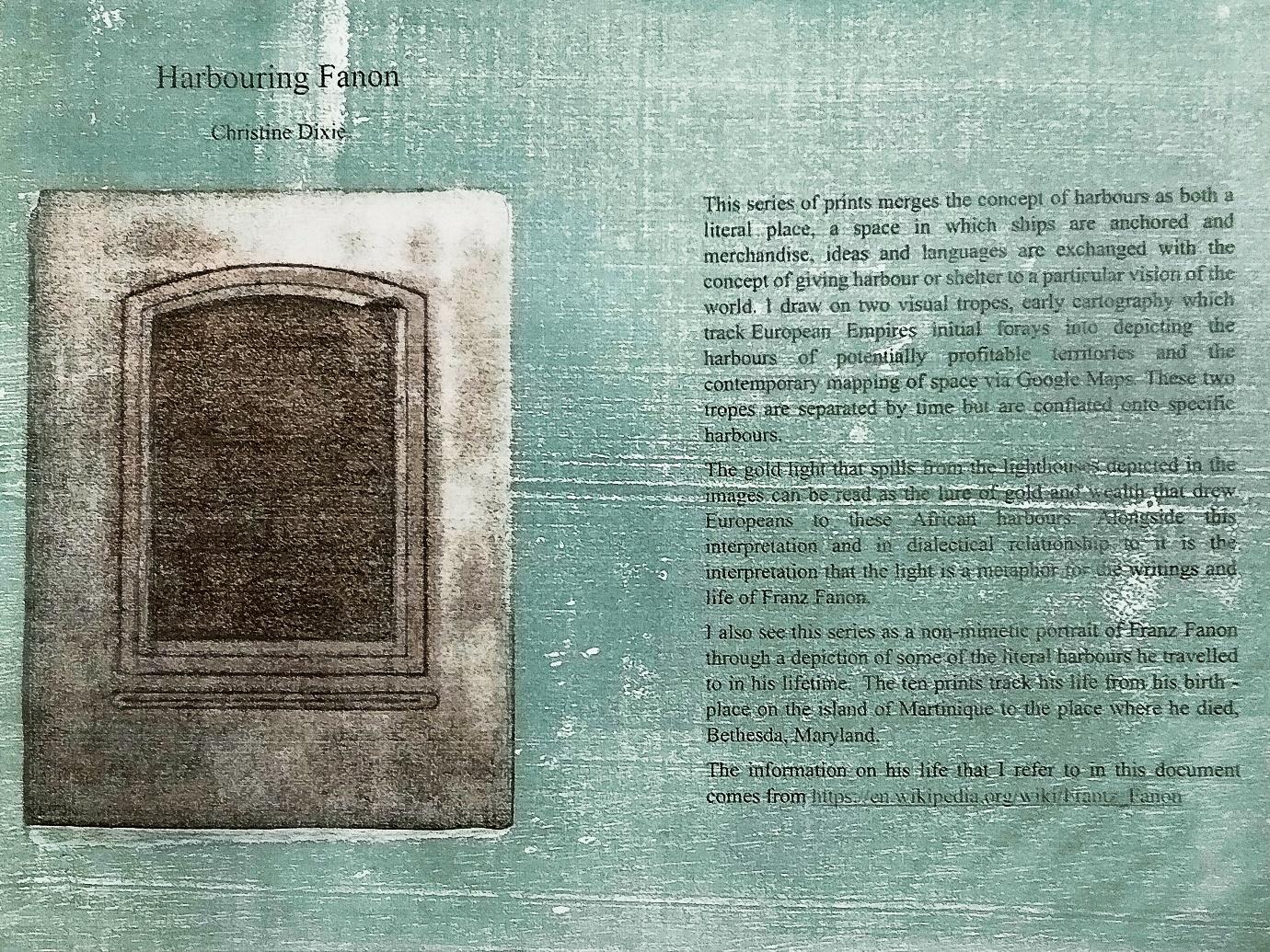

Harbouring Fanon

Christine Dixie

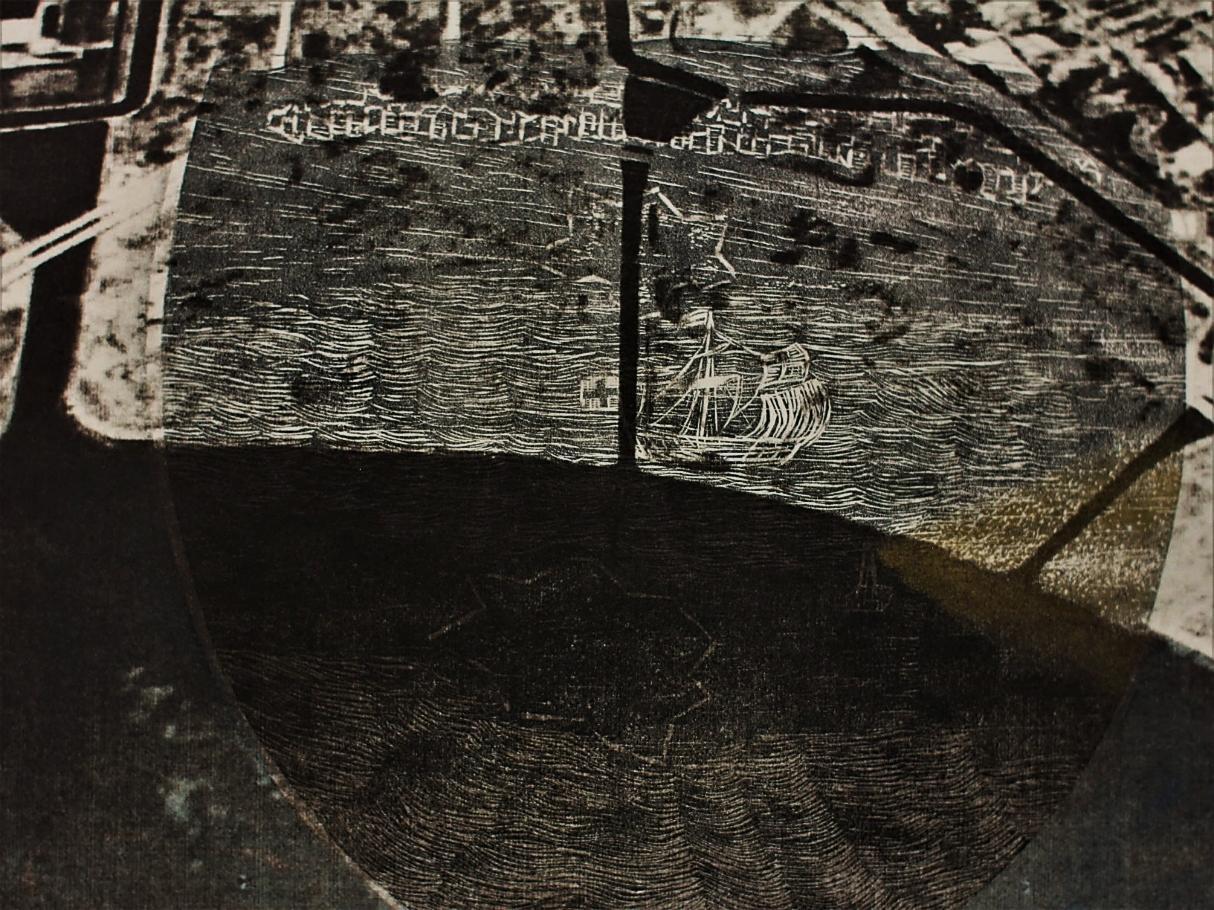

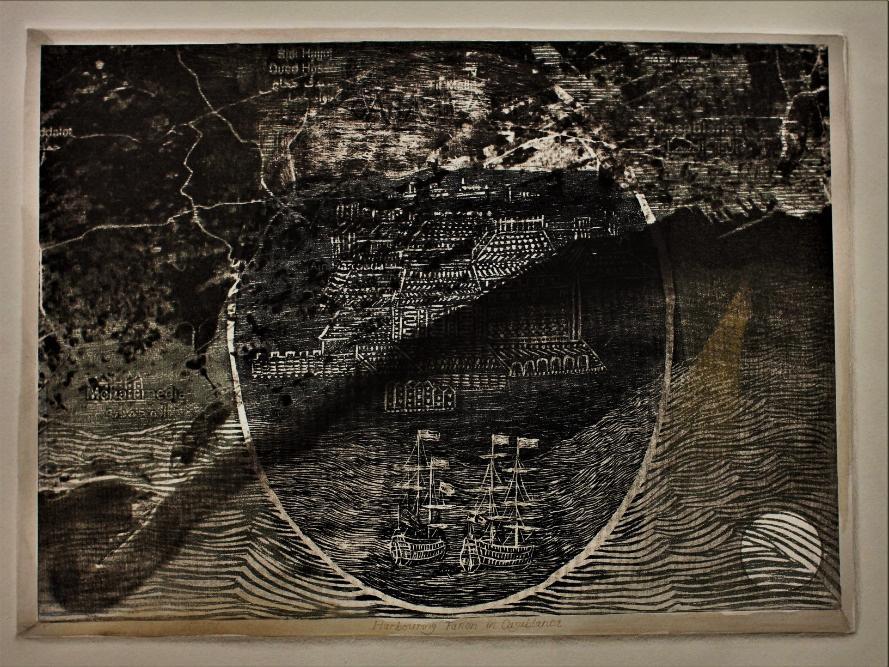

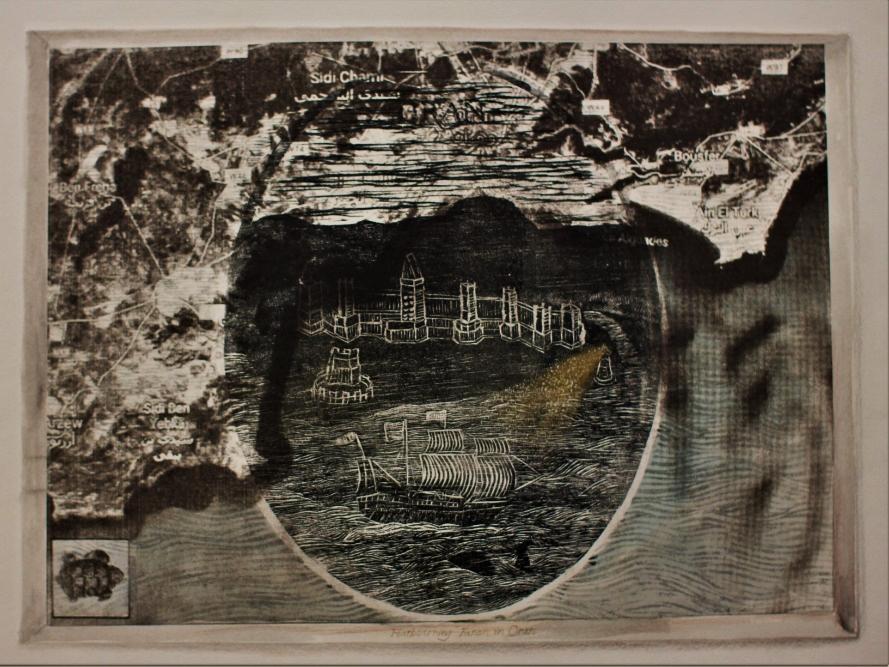

Hand coloured woodcuts and transfer with gold dust. 500mm x 380mm

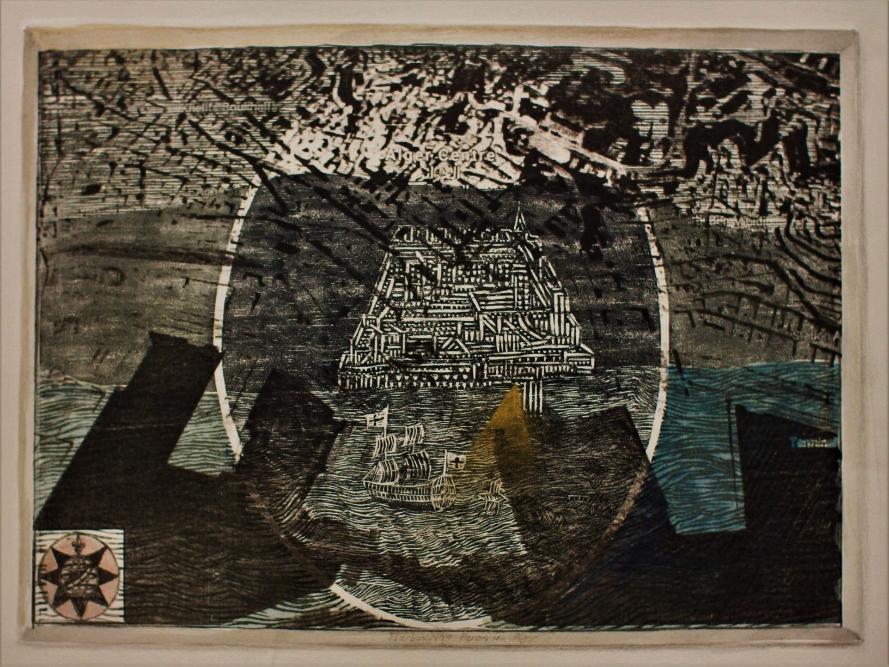

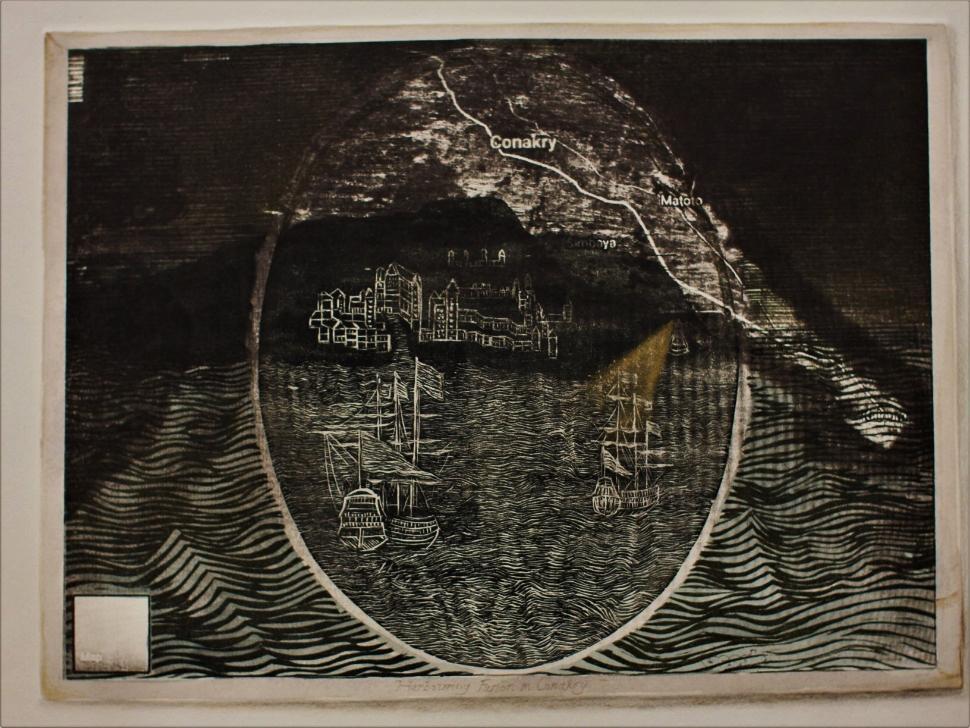

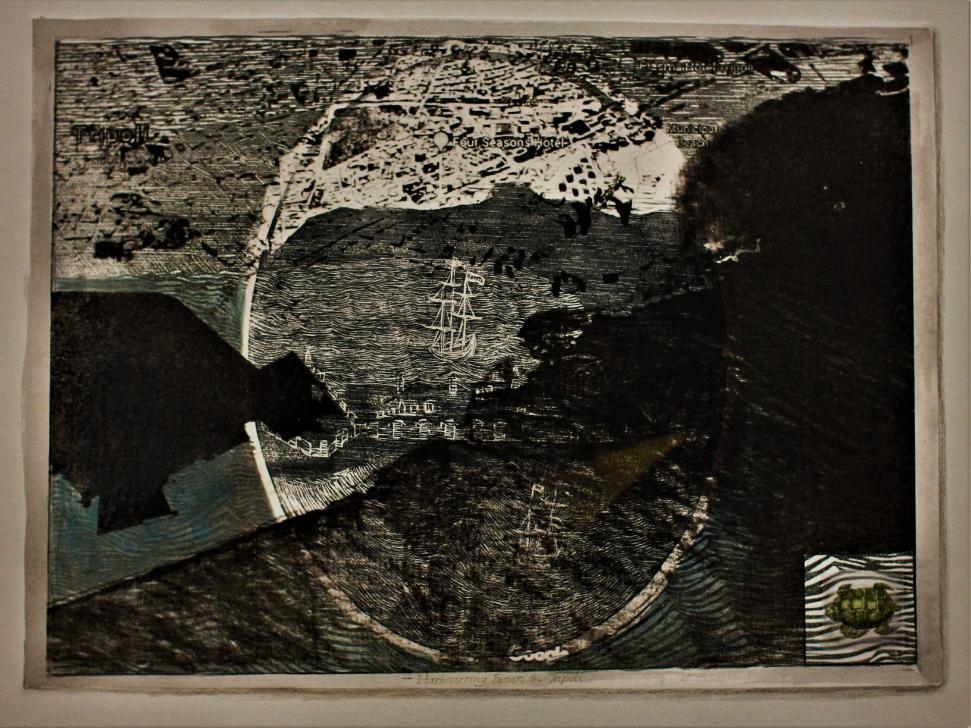

This series of prints merges the concept of harbours as both a literal place, a space in which ships are anchored and merchandise, ideas and languages are exchanged with the concept of giving harbour or shelter to a particular vision of the world. I draw on two visual tropes, early cartography which track European Empires initial forays into depicting the harbours of potentially profitable territories and the contemporary mapping of space via Google Maps. These two tropes are separated by time but are conflated onto specific harbours

The gold light that spills from the lighthouses depicted in the images can be read as the lure of gold and wealth that drew Europeans to these African harbours. Alongside this interpretation and in dialectical relationship to it is the interpretation that the light is a metaphor for the writings and life of Franz Fanon.

I also see this series as a non-mimetic portrait of Franz Fanon through a depiction of some of the literal harbours he travelled to in his lifetime. The ten prints track his life from his birthplace on the island of Martinique to the place where he died, Bethesda, Maryland. The information on his life that I refer to in this document comes from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frantz_Fanon

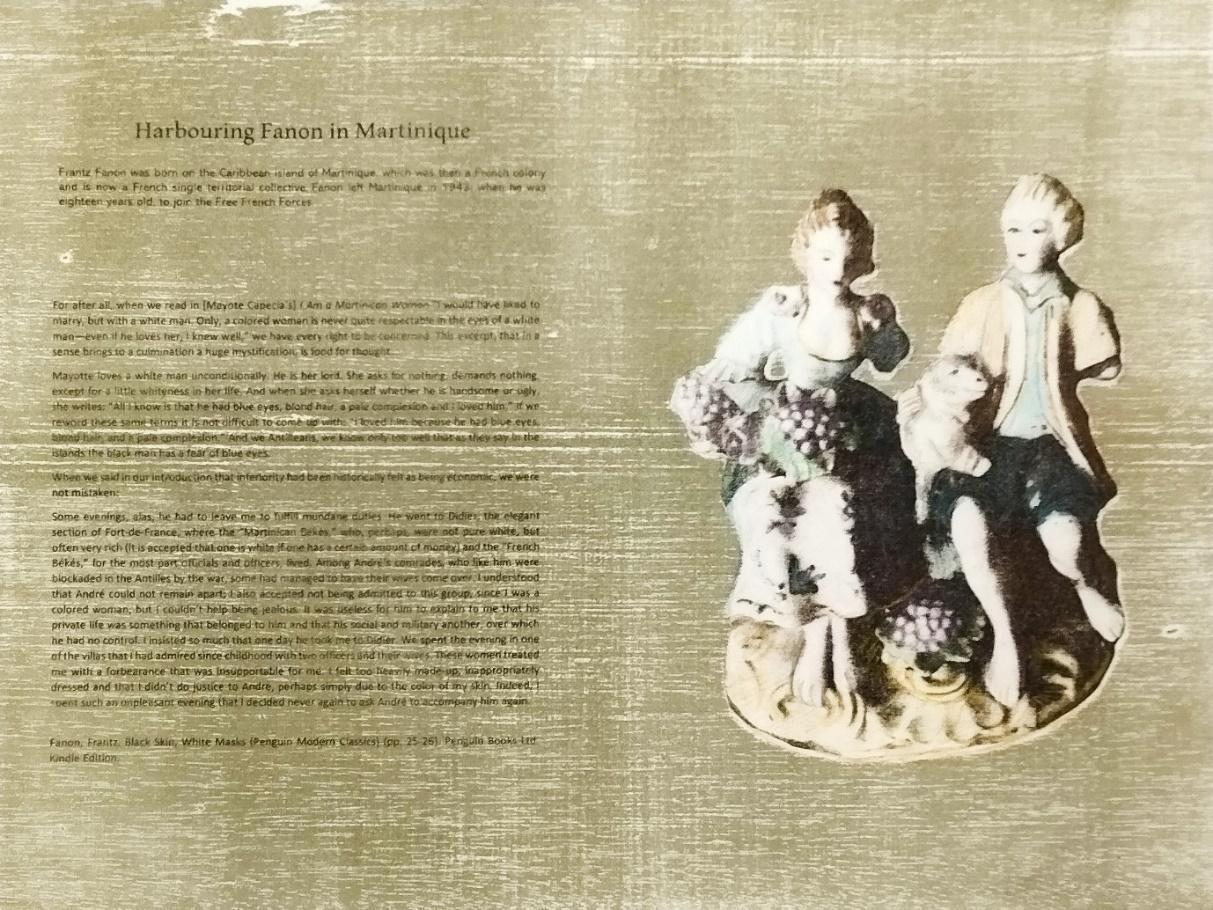

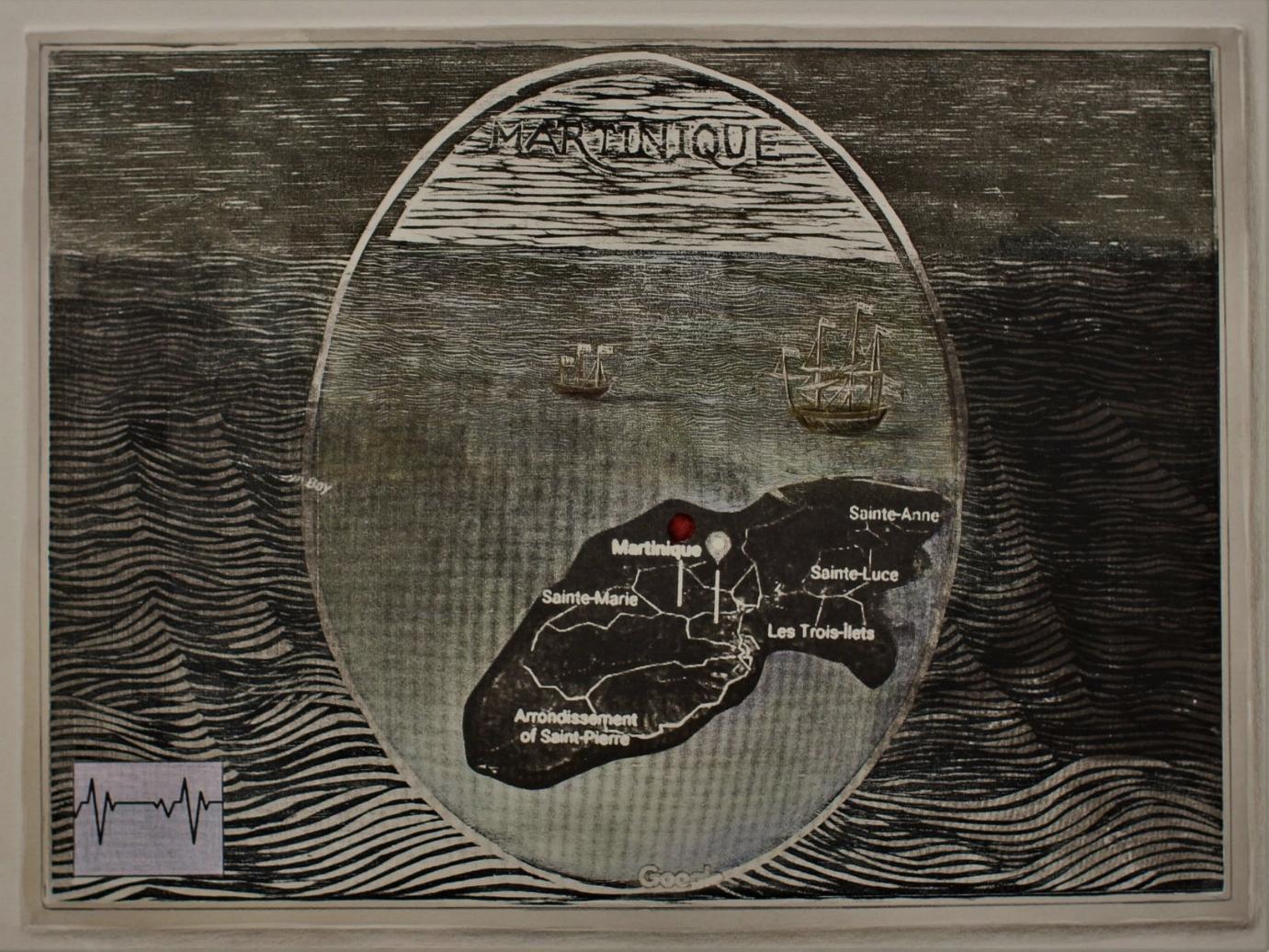

Harbouring Fanon in Martinique

For after all, when we read in [Mayote Capecia’s] I Am a Martinican Woman “I would have liked to marry, but with a white man. Only, a colored woman is never quite respectable in the eyes of a white man even if he loves her, I knew well,” we have every right to be concerned. This excerpt, that in a sense brings to a culmination a huge mystification, is food for thought…

Mayotte loves a white man unconditionally. He is her lord. She asks for nothing, demands nothing, except for a little whiteness in her life. And when she asks herself whether he is handsome or ugly, she writes: “All I know is that he had blue eyes, blond hair, a pale complexion and I loved him.” If we reword these same terms it is not difficult to come up with: “I loved him because he had blue eyes, blond hair, and a pale complexion.” And we Antilleans, we know only too well that as they say in the islands the black man has a fear of blue eyes.

When we said in our introduction that inferiority had been historically felt as being economic, we were not mistaken: Some evenings, alas, he had to leave me to fulfill mundane duties. He went to Didier, the elegant section of Fort-deFrance, where the “Martinican Békés,” who, perhaps, were not pure white, but often very rich (it is accepted that one is white if one has a certain amount of money) and the “French Békés,” for the most part officials and officers, lived. Among André’s comrades, who like him were blockaded in the Antilles by the war, some had managed to have their wives come over. I understood that André could not remain apart; I also accepted not being admitted to this group, since I was a colored woman, but I couldn’t help being jealous. It was useless for him to explain to me that his private life was something that belonged to him and that his social and military another, over which he had no control. I insisted so much that one day he took me to Didier. We spent the evening in one of the villas that I had admired since childhood with two officers and their wives. These women treated me with a forbearance that was insupportable for me. I felt too heavily made-up, inappropriately dressed and that I didn’t do justice to André, perhaps simply due to the color of my skin. Indeed, I spent such an unpleasant evening that I decided never again to ask André to accompany him again.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks (Penguin Modern Classics) (pp. 25-26). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Frantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which was then a French colony and is now a French single territorial collective Fanon left Martinique in 1943, when he was eighteen years old, in order to join the Free French Forces. Harbouring Fanon in Martinique superimposes two visual tropes that are separated by time, a woodcut whose imagery is drawn from early European colonial maps and Google Maps. These two images are collapsed onto the single geographic location of the island of Martinique.

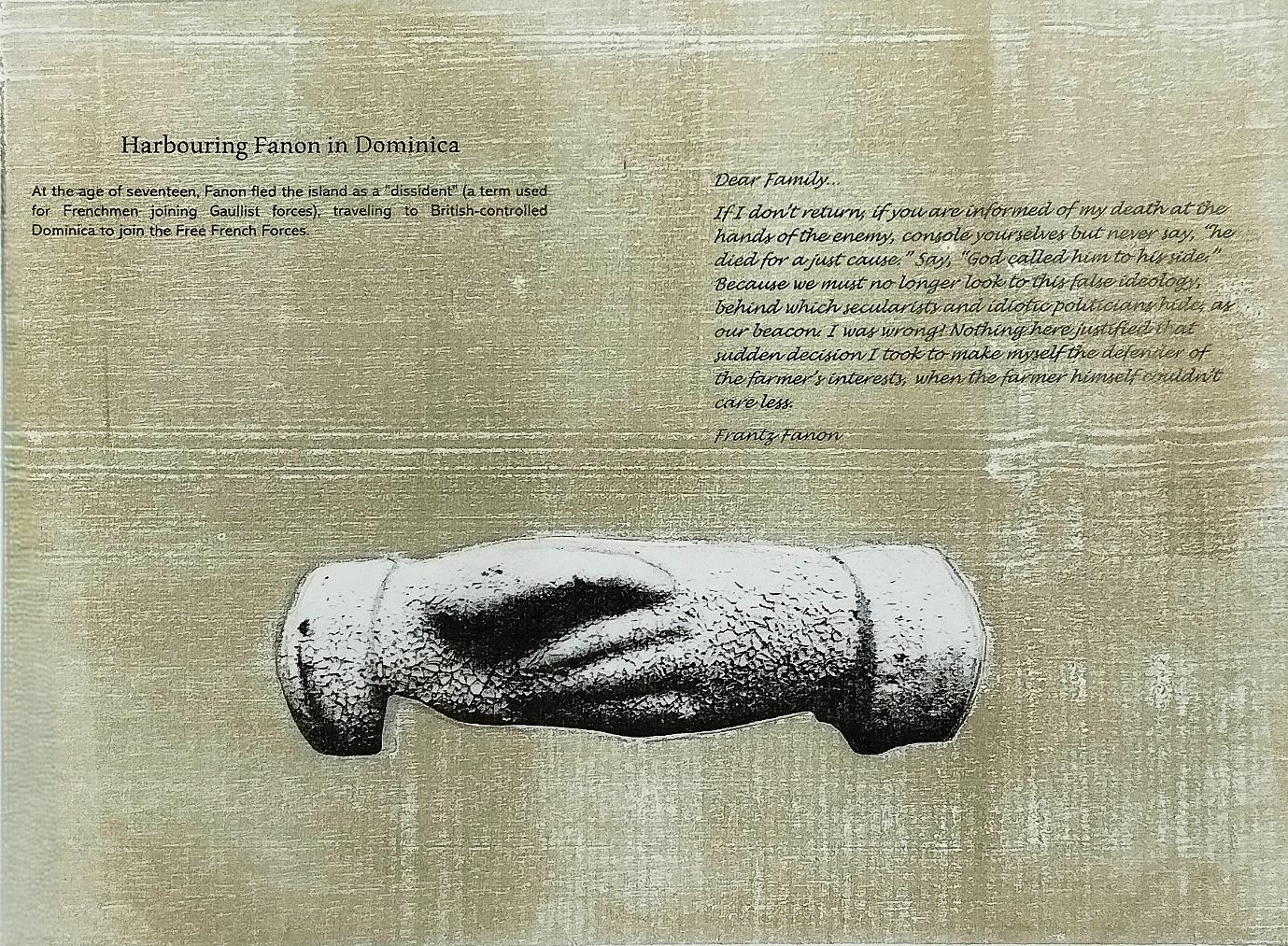

Dear Family…

If I don’t return, if you are informed of my death at the hands of the enemy, console yourselves but never say, “he died for a just cause.” Say, “God called him to his side.” Because we must no longer look to this false ideology, behind which secularists and idiotic politicians hide, as our beacon. I was wrong! Nothing here justified that sudden decision I took to make myself the defender of the farmer’s interests, when the farmer himself couldn’t care less.

Frantz Fanon

Harbouring Fanon in Dominica

At the age of seventeen, Fanon fled the island as a "dissident" (a term used for Frenchmen joining Gaullist forces), traveling to British-controlled Dominica to join the Free French Forces

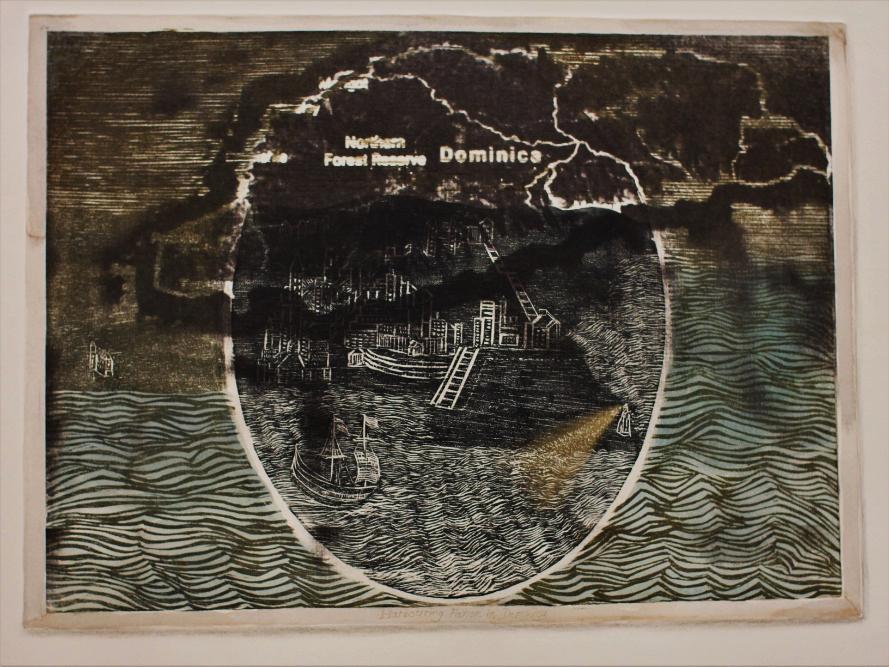

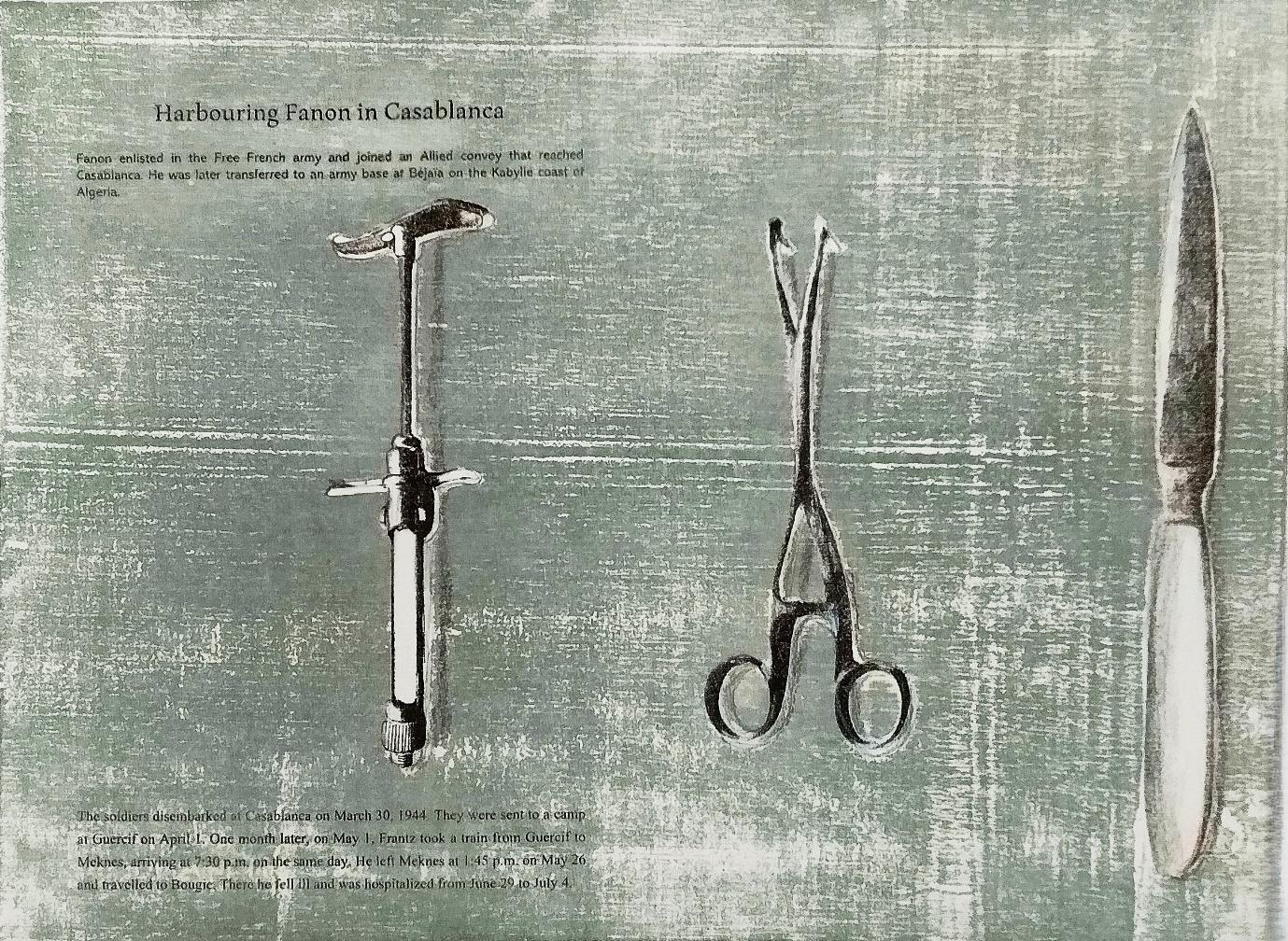

Harbouring Fanon in Casablanca

The soldiers disembarked at Casablanca on March 30, 1944. They were sent to a camp at Guercif on April 1. One month later, on May 1, Frantz took a train from Guercif to Meknes, arriving at 7:30 p.m. on the same day. He left Meknes at 1:45 p.m. on May 26 and travelled to Bougie. There he fell ill and was hospitalized from June 29 to July 4.

Joby Fanon (Fanon’s brother)

Fanon enlisted in the Free French army and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. He was later transferred to an army base at Béjaïa on the Kabylie coast of Algeria.

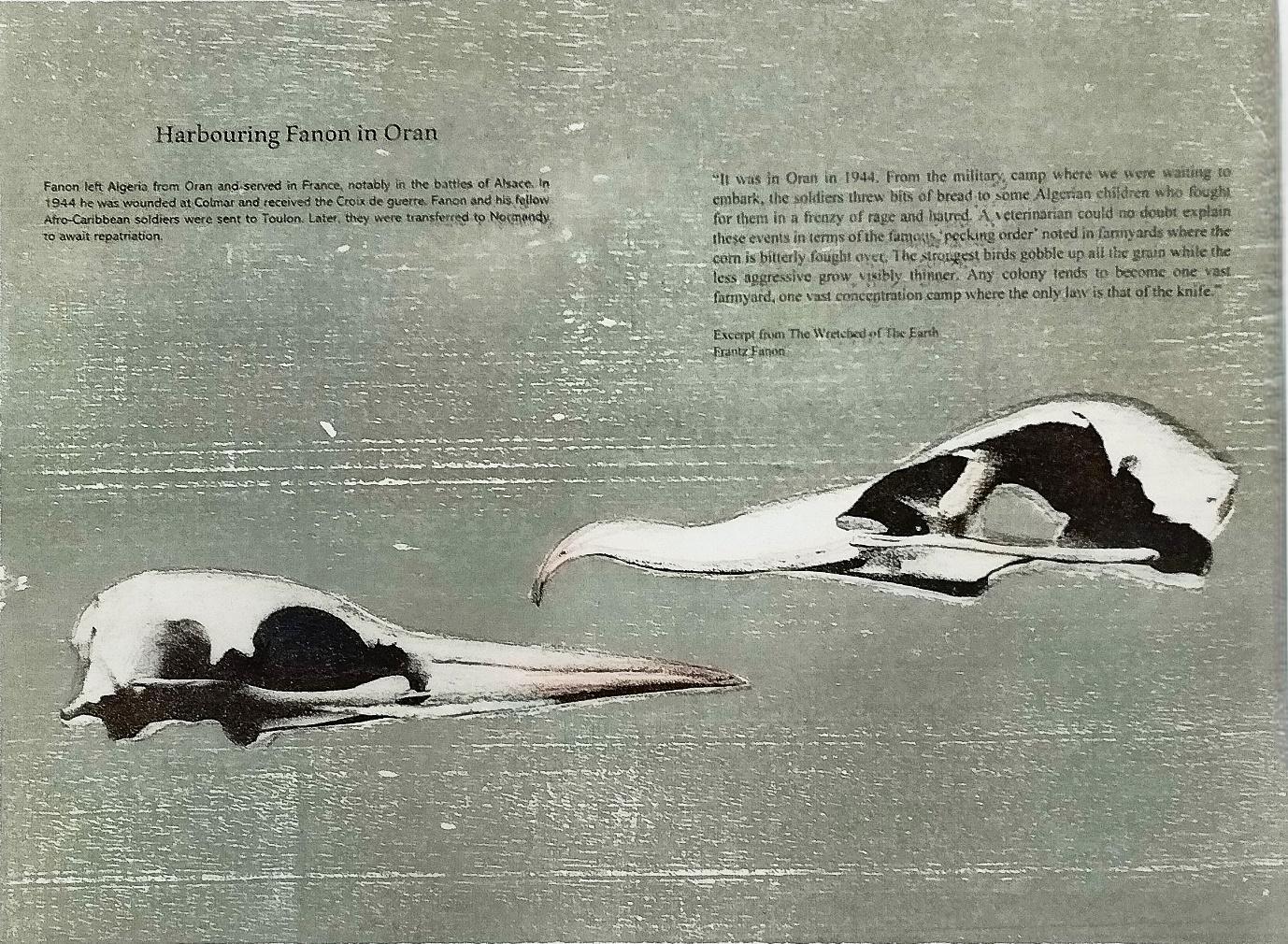

Harbouring Fanon in Oran

“It was in Oran in 1944. From the military camp where we were waiting to embark, the soldiers threw bits of bread to some Algerian children who fought for them in a frenzy of rage and hatred. A veterinarian could no doubt explain these events in terms of the famous ‘pecking order’ noted in farmyards where the corn is bitterly fought over. The strongest birds gobble up all the grain while the less aggressive grow visibly thinner. Any colony tends to become one vast farmyard, one vast concentration camp where the only law is that of the knife.”

Excerpt From The Wretched of The Earth

Frantz Fanon

Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France, notably in the battles of Alsace. In 1944 he was wounded at Colmar and received the Croix de guerre. Fanon and his fellow Afro-Caribbean soldiers were sent to Toulon. Later, they were transferred to Normandy to await repatriation.

Harbouring Fanon in Alger

Algiers

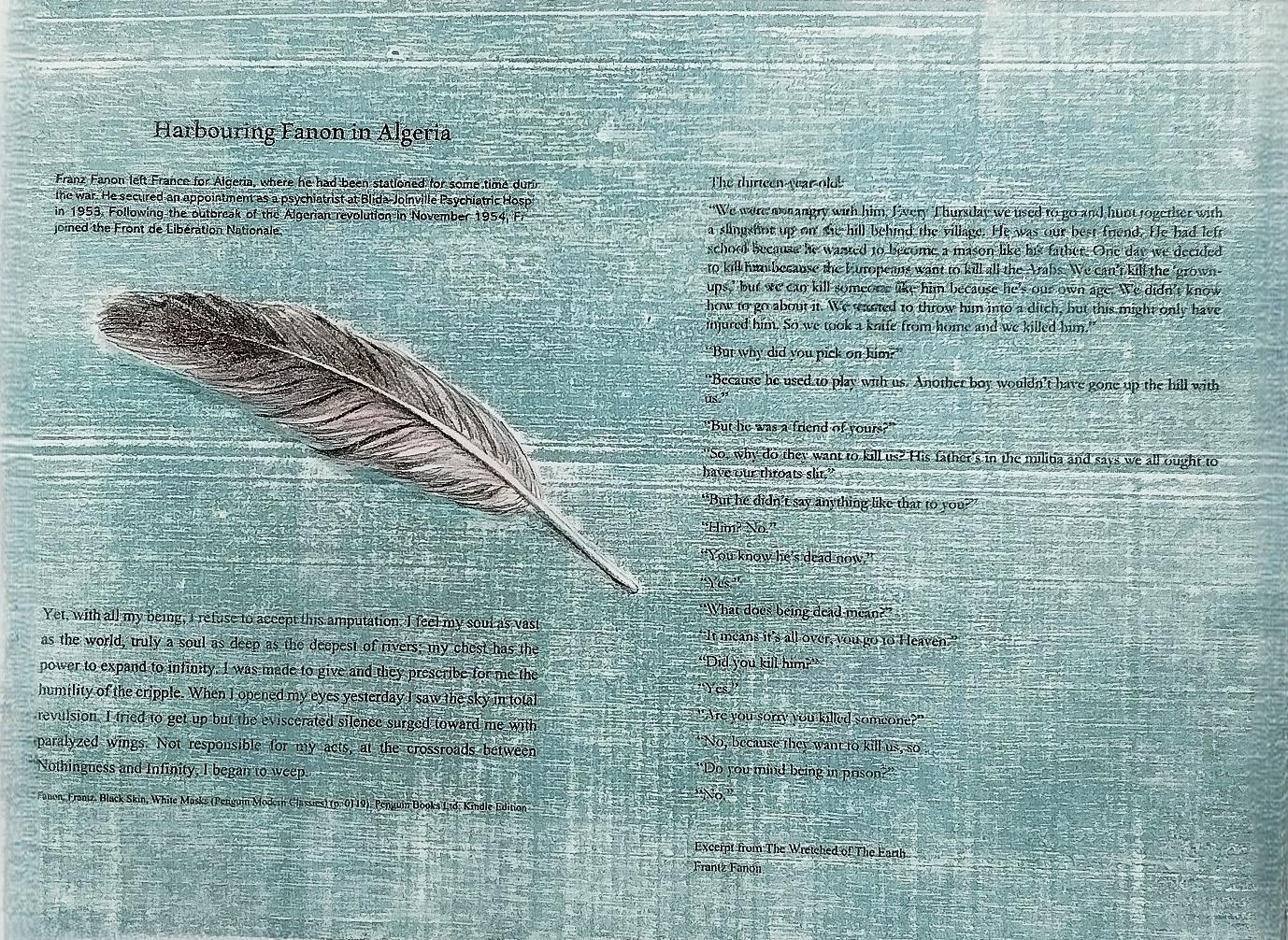

The thirteen-year-old:

“We were not angry with him. Every Thursday we used to go and hunt together with a slingshot up on the hill behind the village. He was our best friend. He had left school because he wanted to become a mason like his father. One day we decided to kill him because the Europeans want to kill all the Arabs. We can’t kill the ‘grown-ups,’ but we can kill someone like him because he’s our own age. We didn’t know how to go about it. We wanted to throw him into a ditch, but this might only have injured him. So we took a knife from home and we killed him.”

“But why did you pick on him?”

“Because he used to play with us. Another boy wouldn’t have gone up the hill with us.”

“But he was a friend of yours?”

“So, why do they want to kill us? His father’s in the militia and says we all ought to have our throats slit.”

“But he didn’t say anything like that to you?”

“Him? No.”

“You know he’s dead now.”

“Yes.”

“What does being dead mean?”

“It means it’s all over, you go to Heaven.”

“Did you kill him?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sorry you killed someone?”

“No, because they want to kill us, so . . .”

“Do you mind being in prison?”

“No.”

Excerpt From The Wretched of The Earth Frantz Fanon

Franz Fanon left France for Algeria, where he had been stationed for some time during the war. He secured an appointment as a psychiatrist at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in 1953. Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale

Yet, with all my being, I refuse to accept this amputation. I feel my soul as vast as the world, truly a soul as deep as the deepest of rivers; my chest has the power to expand to infinity. I was made to give and they prescribe for me the humility of the cripple. When I opened my eyes yesterday I saw the sky in total revulsion. I tried to get up but the eviscerated silence surged toward me with paralyzed wings. Not responsible for my acts, at the crossroads between Nothingness and Infinity, I began to weep.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks (Penguin Modern Classics) (p. 0119). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

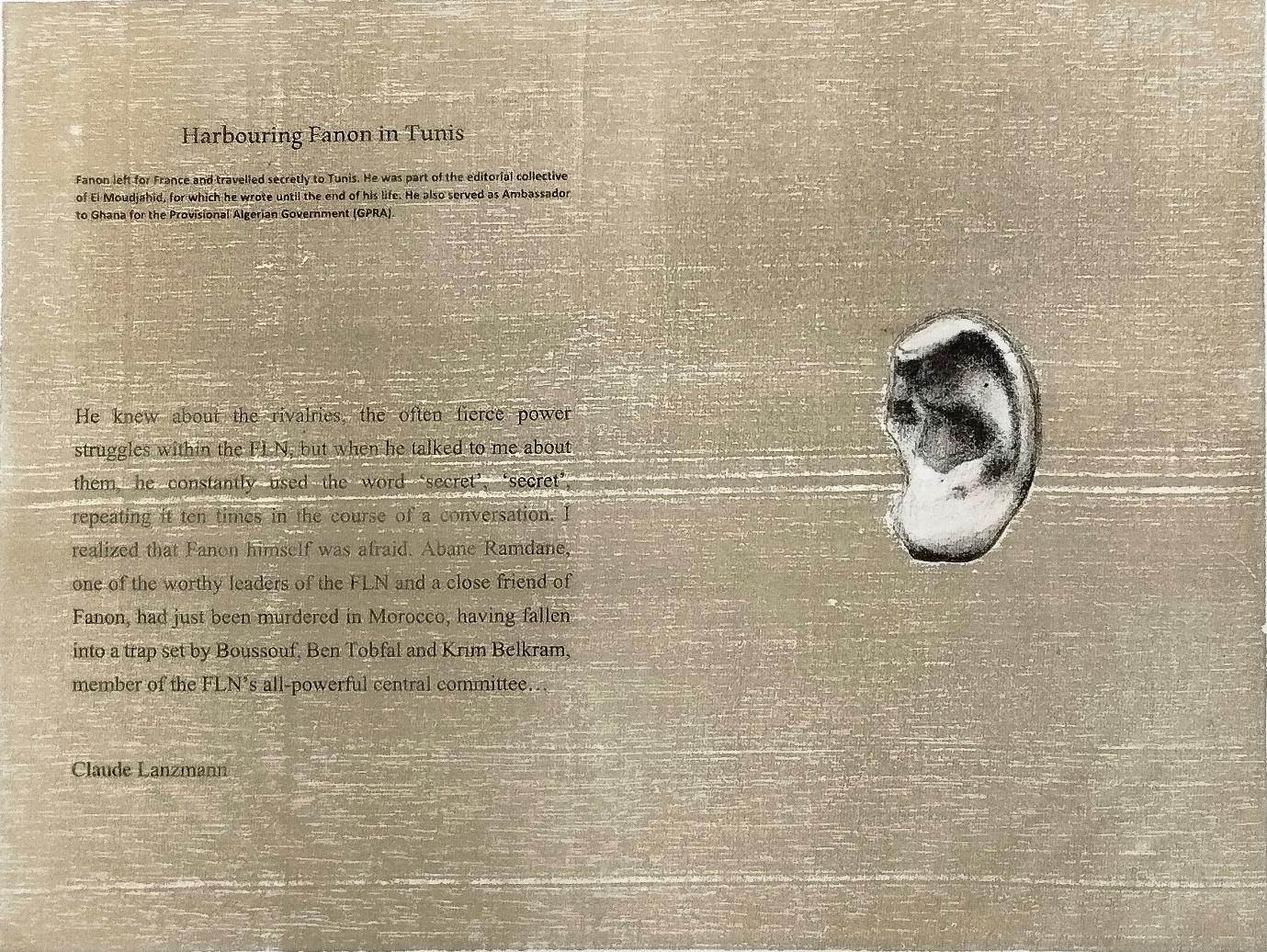

Harbouring Fanon in Tunis

He knew about the rivalries the often fierce power struggles within the FLN, but when he talked to me about them, he constantly used the word ‘secret’, ‘secret’, repeating it ten times in the course of a conversation. I realized that Fanon himself was afraid. Abane Ramdane, one of the worthy leaders of the FLN and a close friend of Fanon, had just been murdered in Morocco, having fallen into a trap set by Boussouf, Ben Tobfal and Krim Belkram, member of the FLN’s all-powerful central committee…

Claude Lanzmann

Fanon left for France and travelled secretly to Tunis. He was part of the editorial collective of El Moudjahid, for which he wrote until the end of his life. He also served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government (GPRA).

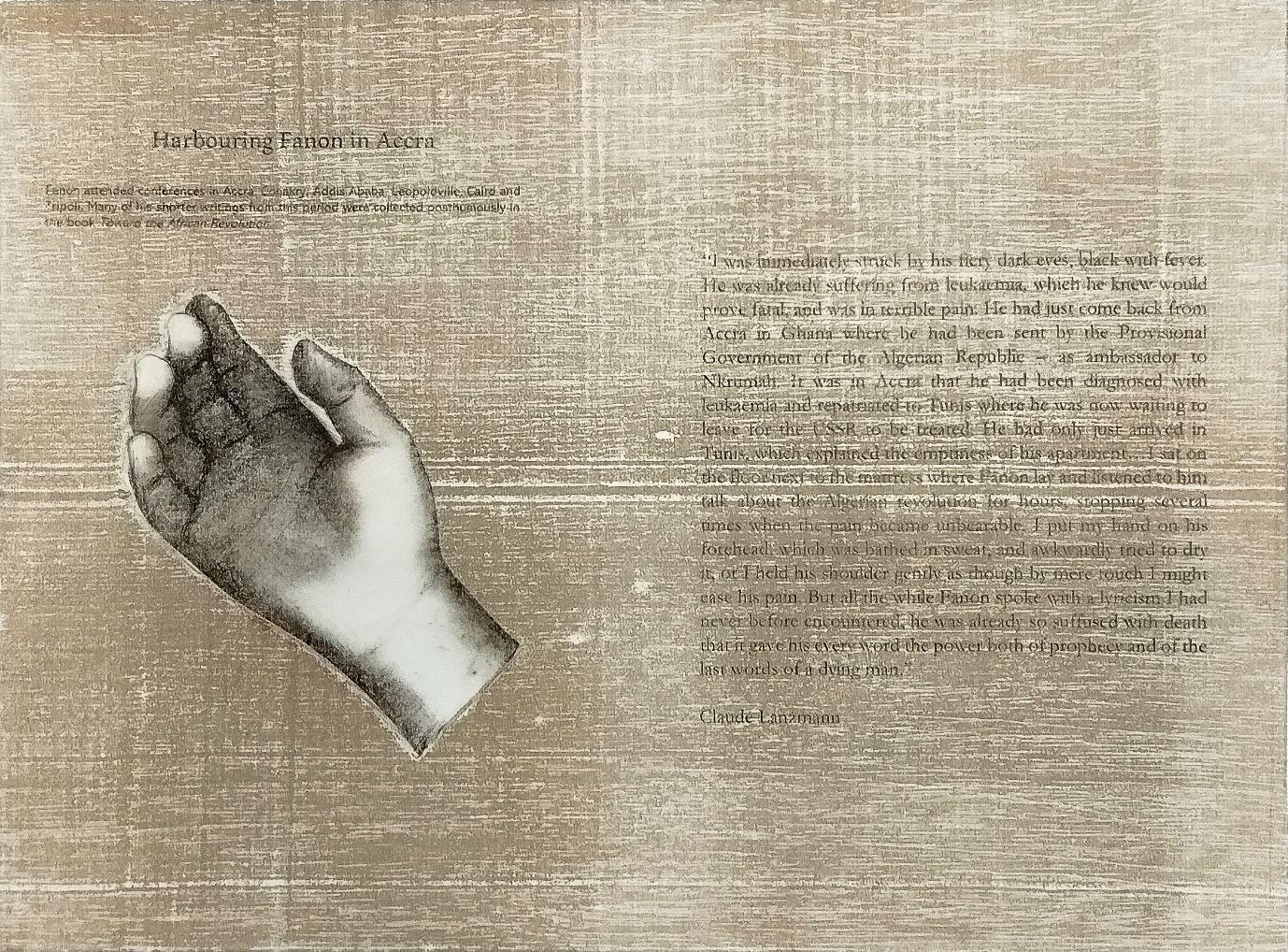

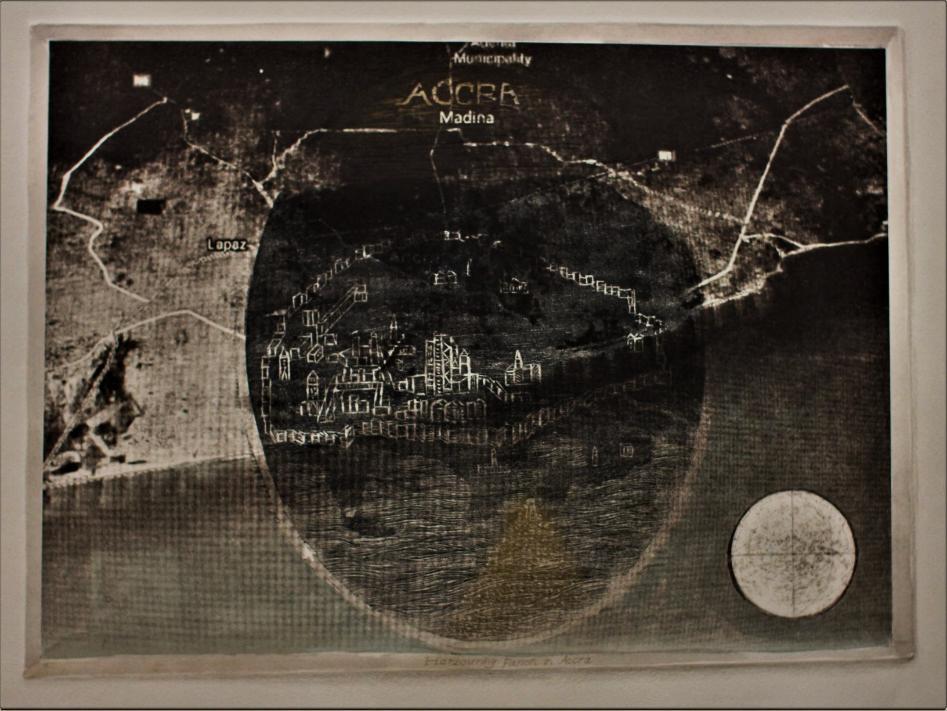

Harbouring Fanon in Accra

“I was immediately struck by his fiery dark eyes, black with fever. He was already suffering from leukaemia, which he knew would prove fatal, and was in terrible pain. He had just come back from Accra in Ghana where he had been sent by the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic – as ambassador to Nkrumah. It was in Accra that he had been diagnosed with leukaemia and repatriated to Tunis where he was now waiting to leave for the USSR to be treated. He had only just arrived in Tunis, which explained the emptiness of his apartment…I sat on the floor next to the mattress where Fanon lay and listened to him talk about the Algerian revolution for hours, stopping several times when the pain became unbearable. I put my hand on his forehead, which was bathed in sweat, and awkwardly tried to dry it, or I held his shoulder gently as though by mere touch I might ease his pain. But all the while Fanon spoke with a lyricism I had never before encountered, he was already so suffused with death that it gave his every word the power both of prophecy and of the last words of a dying man.”

Claude Lanzmann

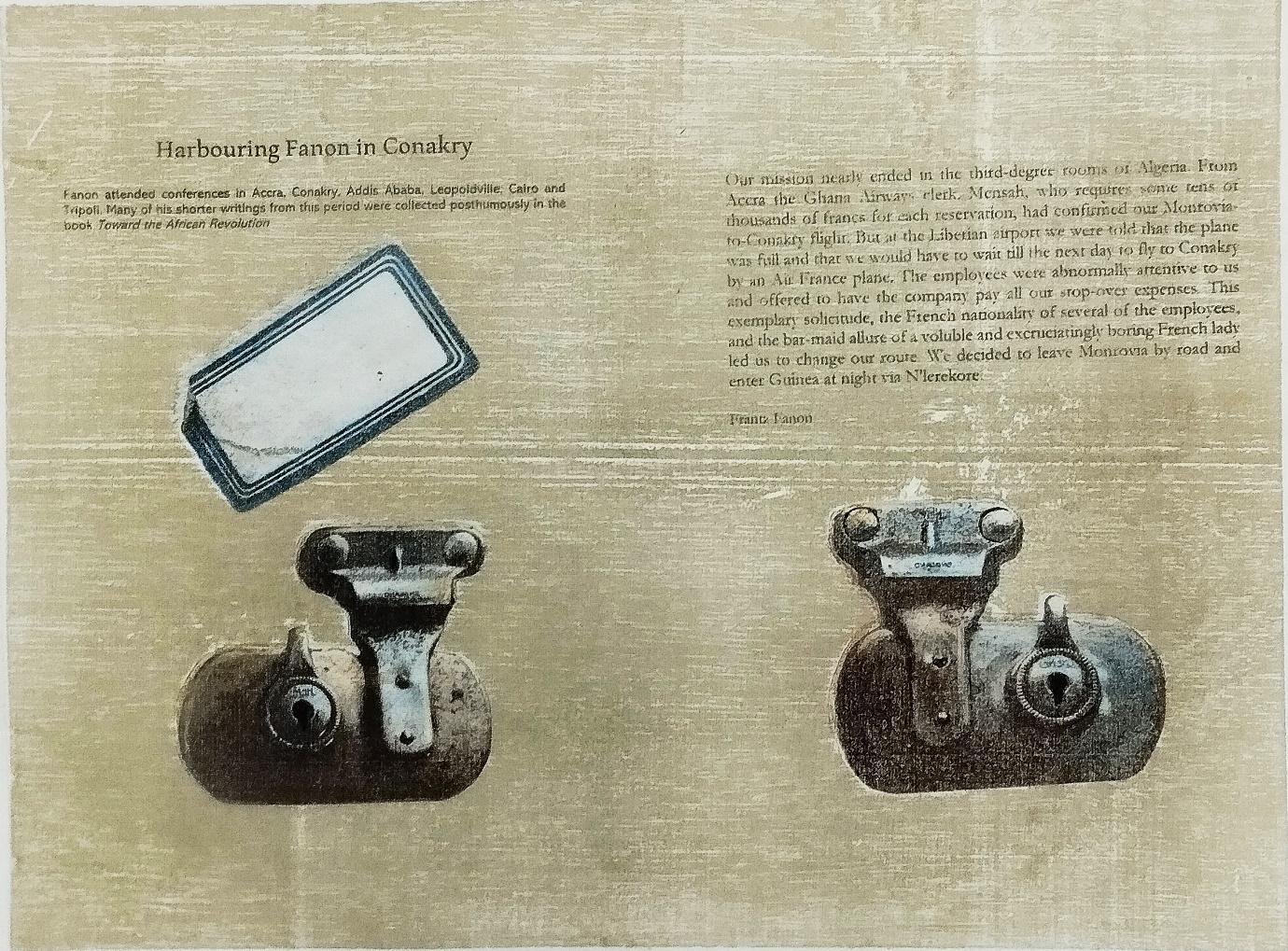

Fanon attended conferences in Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, Leopoldville, Cairo and Tripoli. Many of his shorter writings from this period were collected posthumously in the book Toward the African Revolution.

Harbouring Fanon in Conakry

Our mission nearly ended in the third-degree rooms of Algeria. From Accra the Ghana Airways clerk, Mensah, who requires some tens of thousands of francs for each reservation, had confirmed our Monrovia-to-Conakry flight. But at the Liberian airport we were told that the plane was full and that we would have to wait till the next day to fly to Conakry by an Air France plane. The employees were abnormally attentive to us and offered to have the company pay all our stop-over expenses. This exemplary solicitude, the French nationality of several of the employees, and the bar-maid allure of a voluble and excruciatingly boring French lady led us to change our route. We decided to leave Monrovia by road and enter Guinea at night via N'lerekore.

Frantz Fanon

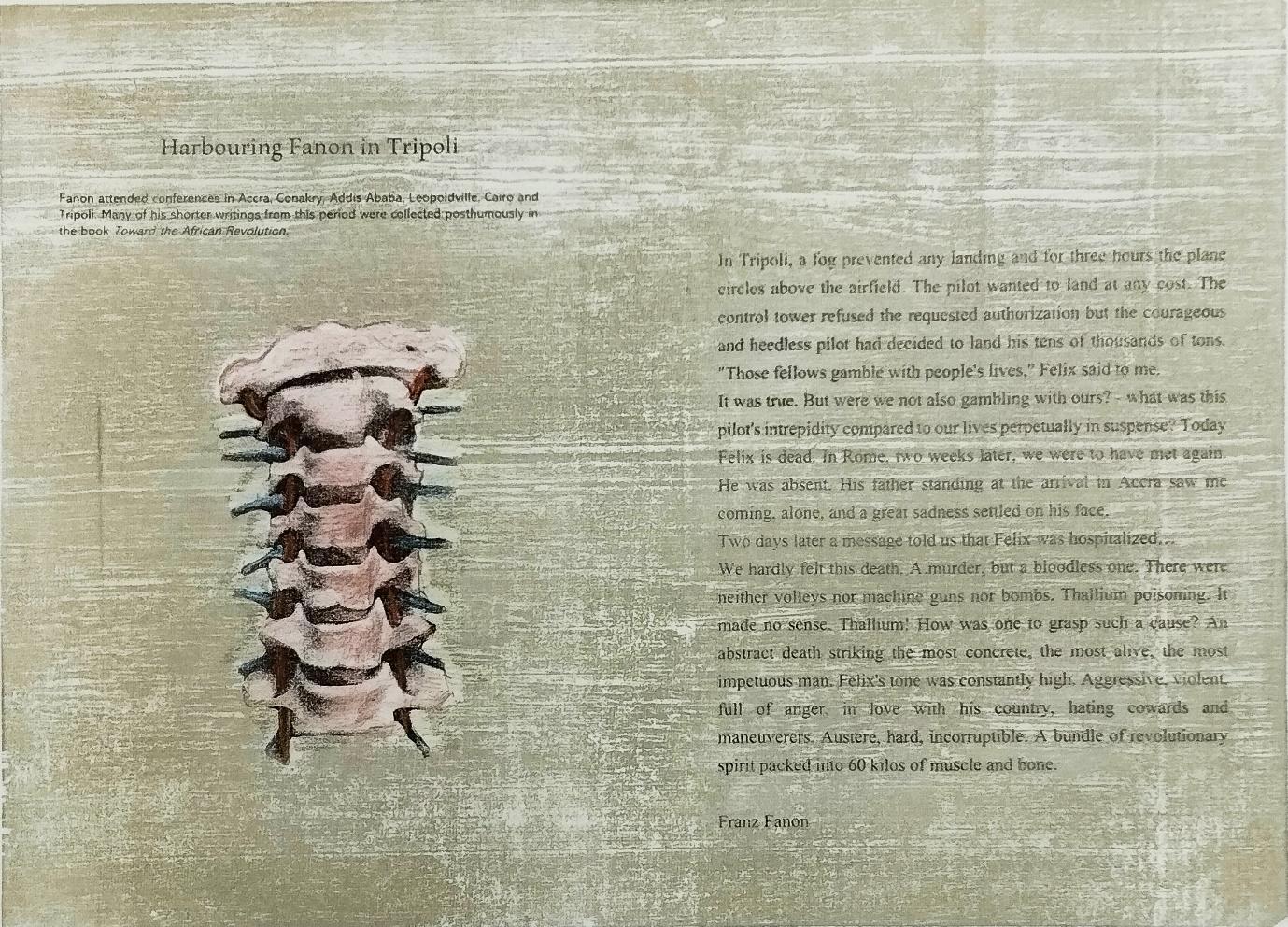

In Tripoli, a fog prevented any landing and for three hours the plane circles above the airfield. The pilot wanted to land at any cost. The control tower refused the requested authorization but the courageous and heedless pilot had decided to land his tens of thousands of tons. "Those fellows gamble with people's lives," Felix said to me.

It was true. But were we not also gambling with ours? - what was this pilot's intrepidity compared to our lives perpetually in suspense? Today Felix is dead. In Rome, two weeks later, we were to have met again. He was absent. His father standing at the arrival in Accra saw me coming, alone, and a great sadness settled on his face.

Two days later a message told us that Felix was hospitalized… We hardly felt this death. A murder, but a bloodless one. There were neither volleys nor machine guns nor bombs. Thallium poisoning. It made no sense. Thallium! How was one to grasp such a cause? An abstract death striking the most concrete, the most alive, the most impetuous man. Felix's tone was constantly high. Aggressive, violent, full of anger, in love with his country, hating cowards and maneuverers. Austere, hard, incorruptible. A bundle of revolutionary spirit packed into 60 kilos of muscle and bone.

Frantz Fanon

Harbouring Fanon in Tripoli

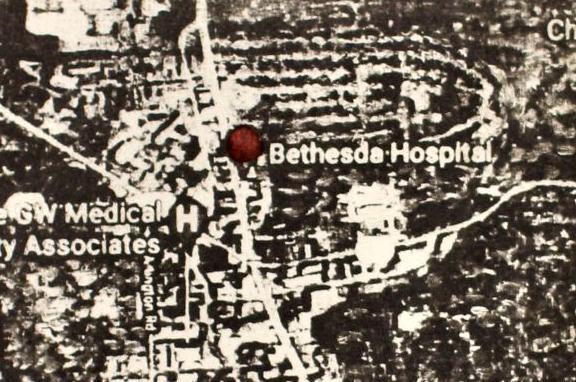

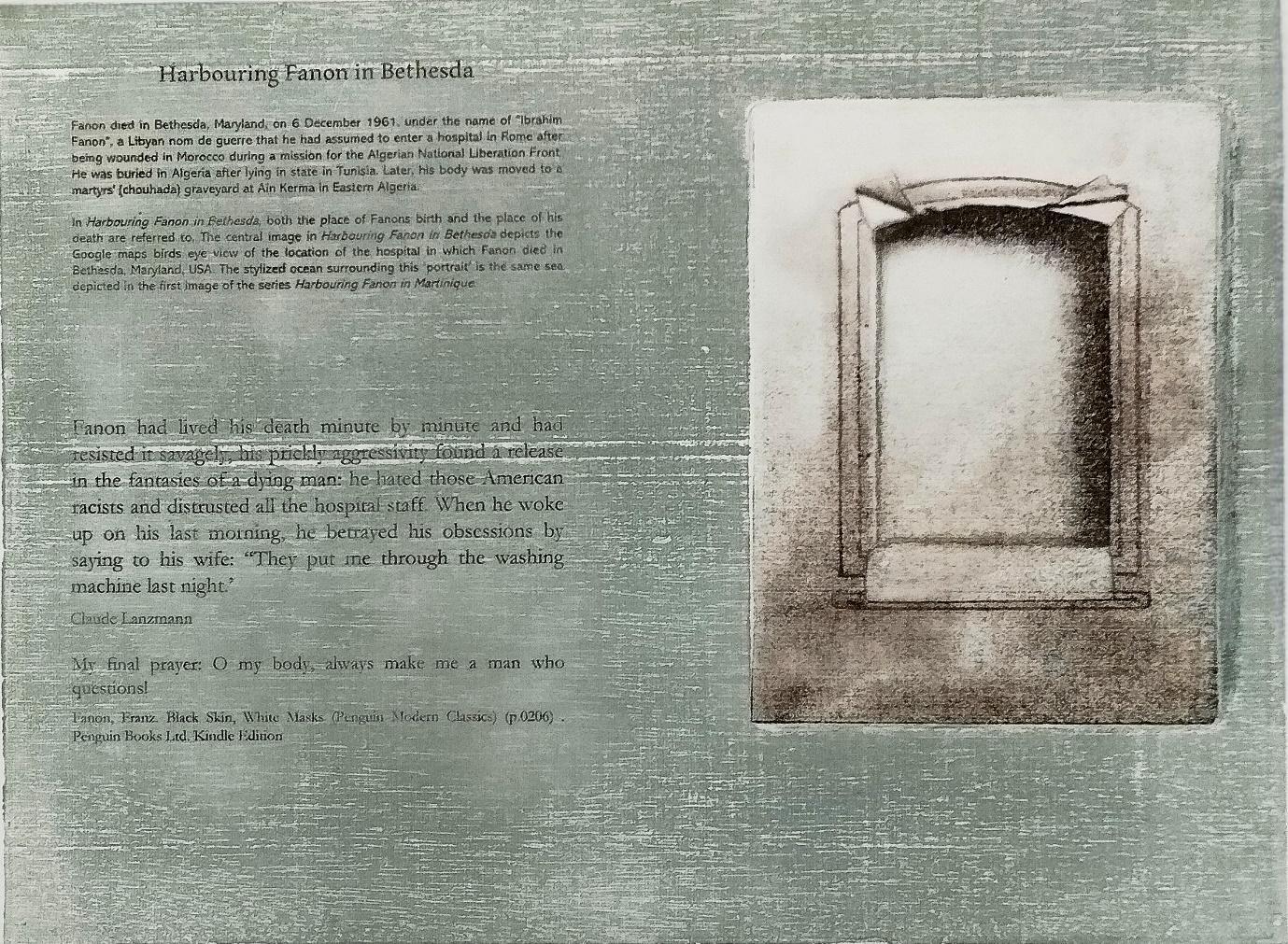

Harbouring Fanon in Bethesda

Bethesda

Fanon had lived his death minute by minute and had resisted it savagely; his prickly aggressivity found a release in the fantasies of a dying man: he hated those American racists, and distrusted all the hospital staff. When he woke up on his last morning, he betrayed his obsessions by saying to his wife: ‘They put me through the washing machine last night.’

Claude Lanzmann

My final prayer: O my body, always make me a man who questions!

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks (Penguin Modern Classics) (p. 0206). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland, on 6 December 1961, under the name of "Ibrahim Fanon", a Libyan nom de guerre that he had assumed in order to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front. He was buried in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later, his body was moved to a martyrs' (chouhada) graveyard at Ain Kerma in Eastern Algeria.

In Harbouring Fanon in Bethesda, both the place of Fanons birth and the place of his death are referred to. The central image in Harbouring Fanon In Bethesda depicts the Google maps birds eye view of the location of the hospital in which Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. The stylized ocean surrounding this ‘portrait’ is the same sea depicted in the first image of the series Harbouring Fanon in Martinique.