Christine Dixie

Website: christinedixie.com | Instagram: @christinedixie

Christine Dixie is a Senior Lecturer in the Fine Art Department at Rhodes University. She is known for haunting imagery relating to the construction of masculine and feminine roles, exposing how they have been cultivated via myths and image-making. The colonial history that haunts the town of Makhanda, where she lives has compelled her preoccupation with Europe’s legacy in Africa.

Dixie has a proclivity for printmaking, but she often works at incorporating her print works with tactile qualities, through embossing, embroidery or other forms of presentation that deny a flat surface. Her interest in printmaking relates to her preoccupation with texts, particularly those relating to artworks and manifests in her ‘book’ works, and her drive to blur the boundaries between text and images.

Typically, Dixie’s print series are part of a body of work that also finds expression through films or elaborate installations. In this way her art is not limited to a specific medium, and as with films has a narrative quality to it, presenting a developing story, which advances with each image, further blurring the boundaries between the present and the past.

Recent exhibitions include, The Binding Project, The Abyssal Zone and Trade-Off. Her work is included in national and international collections including The New York Public Library, The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, The Iwalewahaus Museum, The Standard Bank Gallery, The Johannesburg Art Gallery, The Iziko National Gallery and the University of Johannesburg Gallery.

Photo Credit: Jonathon Rees

Water-Energy-Food Nexus

The WEF (Water-Energy-Food) Nexus was conceptualized to support an integrated approach to these essential resources. In Eco-Imagining, colleagues from Universities of Amsterdam, Fort Hare, Limpopo and the Witwatersrand, and civil society actors, are collaborating to explore what the WEF Nexus offers in social inequalities and structural violence that deprive many people of sufficient basic resources. Our work includes art in public spaces, through collaborations between artists and members of local communities.

Christine Dixie is part of the Eco-Imagining team, and her multimedia installation, The Abyssal Zone, is a major contribution. The series Out of the Blue and Ghostprints for the Infanta, which form part of the exhibition Blueprint for the Disorder of Things were precursors to The Abyssal Zone, which was exhibited at the National Arts Festival this year.

Eco-Imagining works primarily in urban and peri-urban environments, exploring access to water, energy, and food on land in the context of climate change. Christine Dixie’s The Abyssal Zone

Photo Credit: Mark Wessels

places water, food, and energy resources in a wider perspective – on oceans as well as land. The ocean has always been a source of food, and for several hundred years, a means of distributing food, transport, and political domination. Oceans now also provide critical minerals for the technologies of clean energy. Christine Dixie exposes the ironies of plundering the ocean, polluting waters, and destroying marine life. In her works, astronauts inhabit deep waters; colonial and modern-day ships cross the skies, fish sail through celestial scapes. Having jeopardized the future on earth’s surfaces, we now disrupt planetary order. Work in EcoImagining in supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and S A National Research Foundation (PI Moyer and Manderson).

The Dog in the Night:

Christine Dixie’s Blueprint for the DisOrder of Things – Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

Christine

Dixie

has,

for

a long time, been fascinated by a double spectre: Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas and Michel Foucault’s 1970 essay on the same painting.

These two ‘texts’ haunt her Blueprint for the DisOrder of Things, but have long held sway in Dixie’s imagination. The essay, which appears in The Order of Things, Foucault’s ‘Archaeology of the Human Sciences’, is about representation. Its central argument is that the painting is a depiction of the uncanny relations set in motion on the picture plane: the outward-gazing figures, the self- portrait of the artist, the encircling of the figure of the young princess by all of the other characters. Equally uncanny is the mirror image (of the king and queen) inside the canvas, as well as the luminous light that enters the room – the painting, the studio of the painter – from a window suggested on the right side of the picture. And perhaps most curious of all is the representation of painting within the painting, suggested not only by the artist’s presence in his own work but also by the wooden frame of a canvas

presumably in progress on the left. It is as though the painter is watching himself at work.

In his preface to The Order of Things, Foucault explains that the philosophical and historical zone of engagement in his book is a ‘middle region’ to be found in every culture. It lies somewhere between the codes of a culture (those things that govern its language, values, hierarchies of perception) and the scientific theories explaining why order exists and how it is constituted. In this middle region, culture ‘frees itself sufficiently to discover that these orders are perhaps not the only possible ones or the best ones’ (xx) Foucault’s inquiry aims to ‘rediscover on what basis knowledge and theory became possible’ (xxi).

Foucault’s inquiry aims to ‘rediscover on what basis knowledge and theory became possible’ (xxi).

It is significant, then, that as he sets out on this extraordinary inquiry into the order of things, Foucault should begin simply by describing the elements of a single and singular seventeenth-century painting, as though in the space opened up in the painting by the various lines of sight, the various gazes inward and outward, is that middle region he seeks to understand.

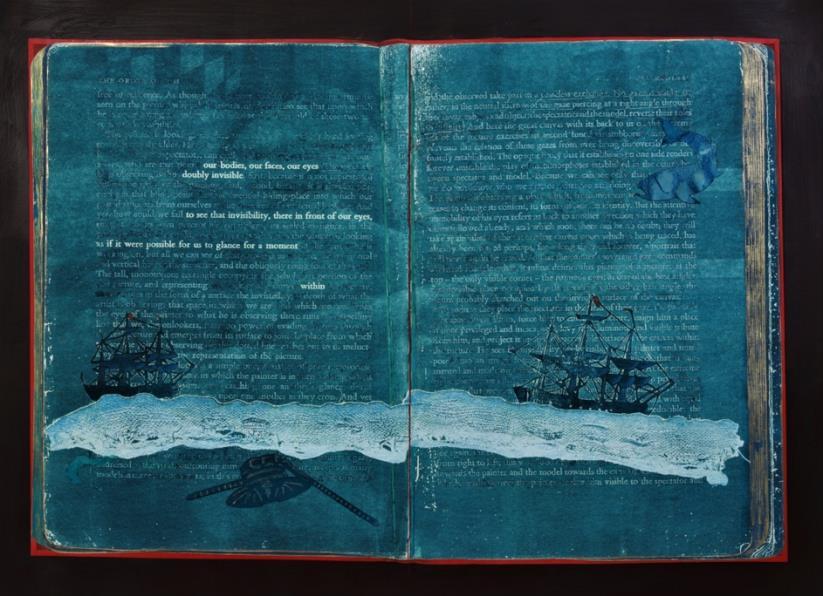

So where does this situate Dixie? When we enter the blue, submarine space of her exhibition, Blueprint for the DisOrder of Things, we enter the middle zone of Foucault’s text. But here, in this submarine space, the materiality of the work – paper, gauzy fabric, golden thread, copper, ink, embossment – is insistent, as are Dixie’s local iterations of ‘the order of things’.

In the layered and labour-intensive materiality of her work – the prints, paintings, sculpture and video – she traces movements through vast arcs of time and space: ships float across the surface of the paper, connecting the twenty-first century to the seventeenth, the Infanta of Velázquez’s painting to slavery, pandemic to pandemic.

Planes fly and land, taking off in Alexandria, Egypt, and arriving in Makhanda, South Africa, before circling away again.

They transect a blue horizon, they crisscross the skies of a southern hemisphere, underneath the sign – the crux – of the skies of the northern hemisphere. But not only planes: ships of sea and space drift across the picture plane, through clouds, through water. The world is inverted: the pilot of the space craft arrives in the depth of the ocean, the diver lands on the moon. These explorers are at once tethered and drifting off into the atmosphere. They pass fish and fowl, they float through space. They represent the event horizon, the moment of exploration and the end of the frontier.

The little princess – the Infanta Margaret Theresa who will marry the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I – traverses space and time, painting, dropping pigment as she goes, pointing up and beyond. She touches the plague doctor, with his strange conical hat and his beaked mask filled with sweetsmelling herbs that are thought to counter the miasma of the infected house.

The plague doctor, his title notwithstanding, is principally a recorder of deaths, a keeper of the numbers, a medieval apparition whose function is not so much healing as counting, imposing order on chaos, controlling through listing.

We know him just as well now as our plague-killed ancestors did. The princess also miraculously generates worlds with her brush. They come into being ‘out of the blue’, which means ‘from nowhere’ or ‘from left field’ – unexpectedly. She paints herself in repeated acts of self-generation: the artist begets her own consciousness through the materiality of paint and brush and canvas. The artist thinks herself into being. She inscribes but is also inscribed upon, she is an extension of the discourse of order, she is a proponent of codes that describe how the world is made, but also how it falls apart.

It is profoundly comforting to know that he is ‘a figure not yet two centuries old, a new wrinkle in our knowledge, and that he will disappear again as soon as that knowledge has discovered a new form’ (xx). By knowledge, Foucault does not only mean empirical science, or even philosophy or history, but rather something beneath these forms, something that allows them to come into being, a perception in each culture that knowledge can be described and embodied. Once a new body is found through which it can be expressed, we will be redundant.

What is so clearly also at play in this work, expressed perhaps most poignantly in Dixie’s video work, with its sounds of inhalation and expiration, its use of umngqokolo throat singing by women in the Eastern Cape, its beeping and sighing ventilator, is an acute awareness of the frailty of the planet and the tenuousness of our place in it. Things are turned upside down, to be sure, and this body of work is a site of mourning, death and, in its most optimistic moments, regeneration. Perhaps the most haunting motif in Blueprint for the DisOrder of Things, is the arrival, traversal and departure of the car in the video. The depiction of twin headlights lighting up the dark, approaching as though home is being reached, is a gesture that is –almost unbearably – poetically wistful.

The lights suggest a way through, an arrival, but also perpetual departure and loss.

As Donna Haraway suggests in Staying With the Trouble, ‘Grief is a path to understanding entangled shared living and dying; human beings must grieve with because we are in and of this fabric of undoing. Without sustained remembrance, we cannot learn to live with ghosts and so cannot think. Like the crows and with the crows, living and dead “we are at stake in each other’s company”’ (39).

And apropos Haraway, who has written extensively about interspecies collaboration and connectedness, it is the dog in Dixie’s work, an upward-looking and wise creature, who most understands what is at stake.

References

Michel Foucault. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage Books, 1994 Donna Haraway. Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016

Gallery 1

Ghostprints for the InfantaNingxia

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta –our bodies, our faces, our eyes

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta –Alexandria

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ensemble

2020

Copper plates on music stands

Dimensions variable

R90 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta –Damascus

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta – in the midst of this dispersion

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta –manifested into pure spectacle

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta –caught in a moment of stillness

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Ghostprints for the Infanta –Makhanda

2022

Digital print, collage, woodcut, watercolour, thread 1130 x 850 mm

R38 000.00

Between the Pages of Britannica

2024

Encyclopedia Britannica with interventions

R18 000.00

Blue Sequence

2022

Video projection (7 minutes)

Blue Transmission I and II

2022

Ink, collage, and thread

1640 x 1250 mm

R90 000.00 each

Out of the Blue I - V

2022

Ink and collage 1250 x 1770 mm

R115 000.00 each

Below the Crux I - IX

2020

Etching, monotype, collage, and thread

690 x 820 mm

R150 000.00

Blueprint for the Disorder of Things

A solo show by Christine Dixie 23 September – 06 October 2024

All images and text ©Christine Dixie

Exhibition Production: Christine Dixie, and GUS in partnership with Art Source South Africa, Toyota Stellenbosch Woordfees, Stuttaford Van Lines, Eco Imagining Africa, Rhodes University, Stellenbosch Visual Arts and Stellenbosch University

GUS Volunteers: Chrystopher Abbott, Anna Grace, Lucy Clegg, Fleur Esterhuysen, Jacqueline Dow, Jane Rigava, Kajal Ranchhod, Kabous Hanslam, Keishia Van Der Vent, Olorato Makgale, Ofentse Seakgoe, Roe Jones, Ron Sauerman, Samantha Schimper, Bethan Swiegers, Juane Swart, Anna Van Pletsen, and Yasmeen Williams

GUS Curatorial Intern: Bianca Davis

GUS Custodian: Kamiela Crombie

GUS Gallery Committee: Dr. Kathryn Smith, Prof. Ernst van der Wal, Dr. Karolien Perold-Bull, Carine Terreblanche, Ashley Walters, Ledelle Moe

GUS (Gallery University Stellenbosch) is managed by the Department of Visual Arts, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University

GUS

Corner of Dorp and Bird Streets, Stellenbosch

gus@sun.ac.za

www.gus-gallery.co.za

Instagram: @stbgus

Facebook: GUS / @galleryuniversitystellenbosch

Tues - Fri: 09h00 - 16h00

Sat: 10h00 - 14h00 Mondays by appointment