A true midwestern vaudevillian

An interview with Dennis Scott, longtime Music Box Theatre organist

By Joshua Minsoo Kim, p. 14

Leor Galil shares his favorite overlooked Chicago records of 2025, p. 18

An interview with Dennis Scott, longtime Music Box Theatre organist

By Joshua Minsoo Kim, p. 14

Leor Galil shares his favorite overlooked Chicago records of 2025, p. 18

04 Nature BIPOC Birders fosters communal connections to nature.

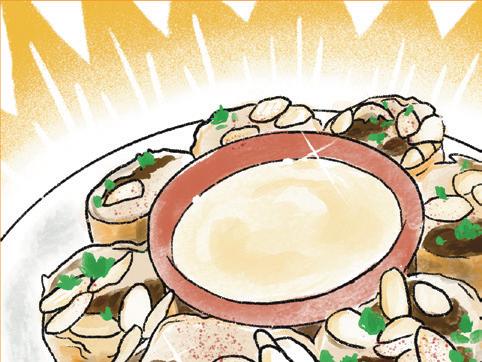

05 Reader Bites | McFadden Mansaf bites at M’daKhan

06 Feature Restrictive regulations, denials, and long wait times plague the state’s weatherization assistance program.

09 Make It Make Sense | Brown & Mulcahy Federal agents use tear gas in Elgin, Waymo eyes an expansion to Illinois, and the Book Cellar staff are unionizing.

10 Feature | Cardoza Artists Ruyell Ho and Li Lin Lee present different takes on abstraction at the Chinese American Museum of Chicago.

12 Feature The Orbit at iO puts long-form improv in the round.

13 Plays of Note Dorian at Open Space Arts celebrates Oscar Wilde; Gaslight at Northlight is a thriller of a good time; and The Real Housewives of the North Pole serves up seasonal tea with Hell in a Handbag.

14 Cover Story An interview with longtime Music Box Theatre house organist Dennis Scott 16 Moviegoer It’s a wonderful life.

18 Feature | Galil The best overlooked Chicago records of 2025

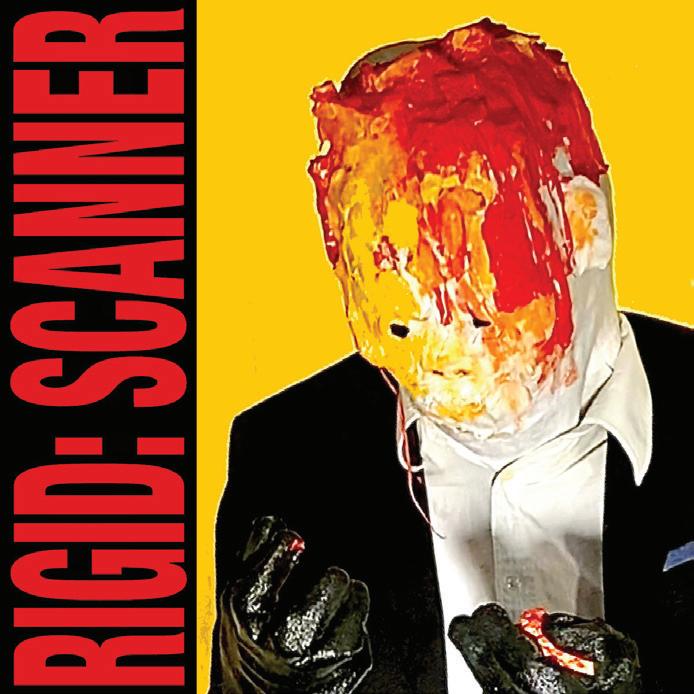

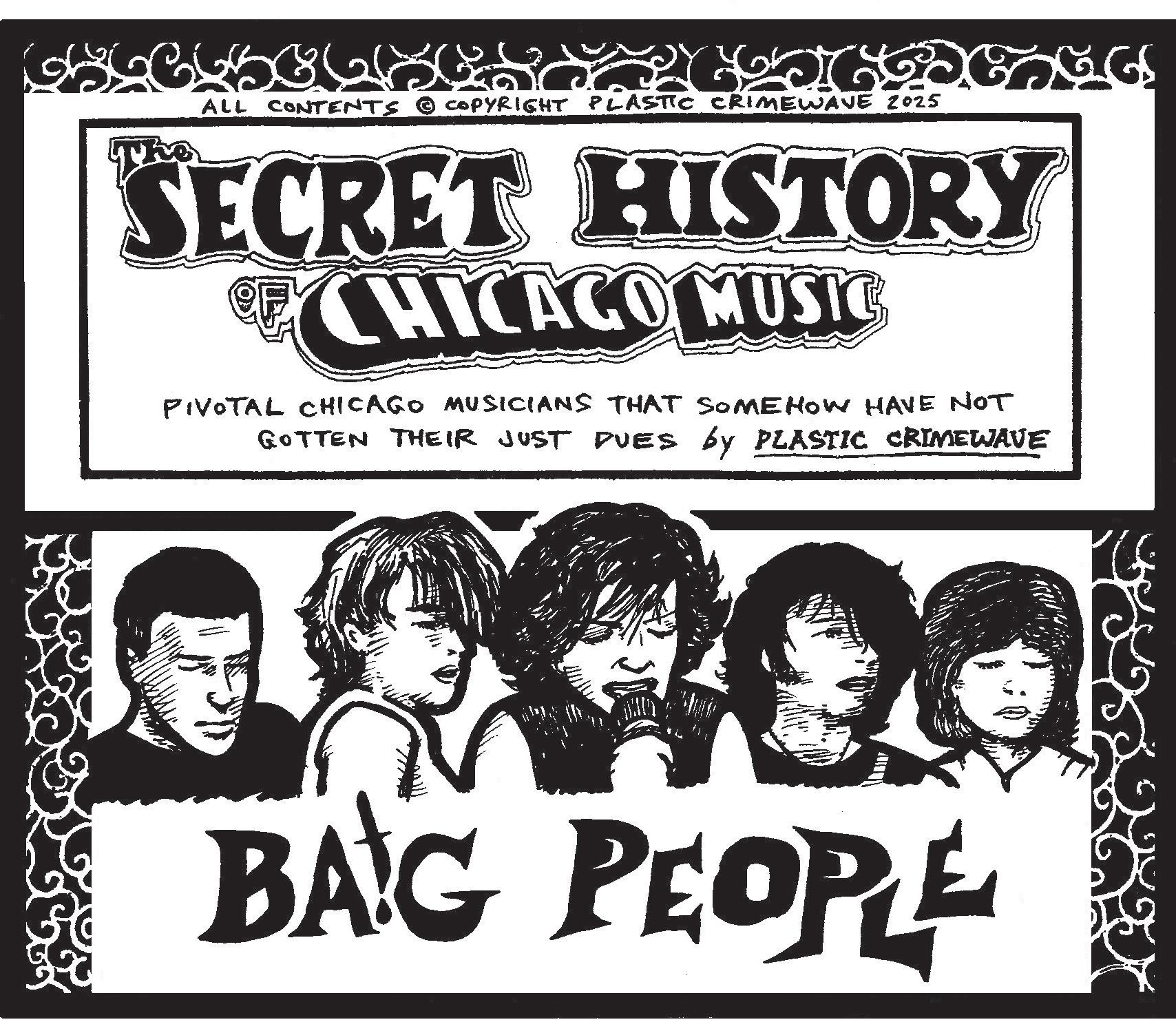

20 Secret History of Chicago Music Feral postpunks Bag People finally have a proper album release.

22 Shows of Note Previews of concerts including Bruiser Wolf, the Bug Club, Flowersatherfeet, and Jay Som

26 Gossip Wolf Alabama indie label Earth Libraries hosts a Chicago showcase, the grassroots campaign to dump Spotify goes national, and more.

CLASSIFIEDS

The Reader has updated the online version of “The unstoppable Andrea Yarbrough,” written by Kerry Cardoza and published in our December 4 issue (volume 55, number 10). The piece has been updated to more accurately describe Illinois’s art economy: it’s roughly $36 billion a year, not $1 billion. A caption has also been updated: the project depicted is “Collective Steps” at the South Side Community Art Center, not “tending to: identidad.”

The Reader updated the online version of “For official use only,” by Max Blaisdell

and Matt Chapman, and published in the December 4 issue. The story has been updated to include additional comments from a SoundThinking spokesperson that were provided a er publication. v

Find us on socials: facebook.com/chicagoreader twitter.com/Chicago_Reader instagram.com/chicago_reader linkedin.com search chicago-reader

The Chicago Reader accepts comments and letters to the editor of less than 400 words for publication consideration. m letters@chicagoreader.com

EMAIL: (FIRST INITIAL)(LAST NAME) @CHICAGOREADER.COM

PUBLISHER ROB CROCKER

OF STAFF ELLEN KAULIG ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR

SAVANNAH RAY HUGUELEY

PRODUCTION MANAGER AND STAFF

PHOTOGRAPHER KIRK WILLIAMSON

SENIOR GRAPHIC DESIGNER AMBER HUFF

GRAPHIC DESIGNER AND PHOTO RESEARCHER SHIRA

FRIEDMAN-PARKS

THEATER AND DANCE EDITOR KERRY REID MUSIC EDITOR PHILIP MONTORO

CULTURE EDITOR: FILM, MEDIA, FOOD AND DRINK TARYN MCFADDEN

CULTURE EDITOR: ART, ARCHITECTURE, BOOKS KERRY CARDOZA

NEWS EDITOR SHAWN MULCAHY

PROJECTS EDITOR JAMIE LUDWIG

DIGITAL EDITOR TYRA NICOLE TRICHE

SENIOR WRITERS LEOR GALIL, MIKE SULA

FEATURES WRITER KATIE PROUT

SOCIAL JUSTICE REPORTER DEVYN-MARSHALL BROWN (DMB)

STAFF WRITER MICCO CAPORALE

SOCIAL MEDIA ENGAGEMENT

ASSOCIATE CHARLI RENKEN

VICE PRESIDENT OF PEOPLE AND CULTURE ALIA GRAHAM

DEVELOPMENT MANAGER JOEY MANDEVILLE

DATA ASSOCIATE TATIANA PEREZ

MARKETING MANAGER MAJA STACHNIK

MARKETING ASSOCIATE MICHAEL THOMPSON

SALES REPRESENTATIVES WILL ROGERS, KELLY BRAUN, VANESSA FLEMING

ADVERTISING

ADS@CHICAGOREADER.COM, 312-392-2970

CREATE A CLASSIFIED AD LISTING AT CLASSIFIEDS.CHICAGOREADER.COM

DISTRIBUTION CONCERNS

DISTRIBUTIONISSUES@CHICAGOREADER.COM

READER INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNITY JOURNALISM, INC.

CHAIRPERSON EILEEN RHODES

TREASURER TIMO MARTINEZ

SECRETARY TORRENCE GARDNER

DIRECTORS MONIQUE BRINKMAN-HILL, JULIETTE BUFORD, DANIEL DEVER, MATT DOUBLEDAY, JAKE MIKVA, ROBERT REITER, MARILYNN RUBIO, CHRISTINA CRAWFORD STEED

READER (ISSN 1096-6919) IS PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY THE READER INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNITY JOURNALISM 2930 S. MICHIGAN, SUITE 102 CHICAGO, IL 60616, 312-3922934,

COPYRIGHT

Chicago BIPOC Birders creates inclusive opportunities for year-round bird-watching and community building.

By JASMINE BARNES

The first time Inma Abreu saw a flock of sandhill cranes migrate, they were speechless.

“There are no words to explain all the emotions that you feel,” Abreu said.

A growing group of enthusiastic local birders are committed to creating communal space for Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color to experience the natural wonder of the Great Lakes region. In 2020, the Chicago Bird Alliance brought together a group of BIPOC birders for a training to address the gap in birdwalk leaders of color. Out of a desire to stay connected and build community, that small group would soon begin organizing what became Chicago BIPOC Birders. Started in 2021, the group now meets regularly to witness, protect, and delight in birds. Abreu has been an active member since 2022.

Zelle Tenorio—a fellow birder and close friend Abreu refers to as their “sibling”—joined BIPOC Birders in 2021 after moving from Texas to Chicago and seeking out a year-round outdoor activity. Birders often mark the start of their passion for the hobby by an encounter with a “spark bird”: the bird that ignites a lifelong passion for bird-watching. For Tenorio, an encounter with an orange-beaked Caspian tern at a BIPOC Birders event cemented their love for the activity.

standing that this might be your first time really looking at [birds],” Lubis said. “There’s a communal joy that comes from [watching] somebody becoming closer to nature.”

Creating a supportive space for people of color to engage with nature is more than a casual hobby. Group members acknowledge explicitly and implicitly that engaging in organized activities in nature disrupts patterns

feel safe and invited.

This month, bird enthusiasts from throughout the region waited patiently at JasperPulaski Fish & Wildlife Area—binoculars in hand—for the arrival of sandhill cranes. BIPOC birders made the long drive to Indiana in a rented van to watch massive sandhill cranes soar through the sky and socialize with each other during their short stay in the midwest as they migrate south. The annual trip was co-organized with Feminist Bird Club Chicago, an organization in which Tenorio is also an active leader.

Tenorio considers this annual birding trip the kicko for a “magical time”—the winter birding season.

“Bird-watching is supposed to be about joy, about respecting birds, about contributing to conservation,” Abreu said. “It’s about tapping into our ancestral connection with nature.”

The winter poses challenges to birding, mainly the frigid conditions and decreased bird diversity, as many migrate south during the colder months. Still, birders embrace what Tenorio lovingly calls “weird duck season.” They spend the winter months looking out for migratory ducks visiting from Canada; gazing upon the bright red cardinals perched in snowy trees; and hanging out with sparrows, dark-eyed juncos, and rare snowy owls.

On this year’s sandhill crane trip, the group noticed significantly fewer birds than in previous years. Abreu believes there might be a connection between the climate changes in the region and the birds’ migration patterns.

As their passion for birding and experience as a bird-walk leader grew, so did their gratitude for Chicago’s location on the Mississippi Flyway, a major bird migration route stretching from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Tenorio has come to appreciate how bird-watching helps you mark the four seasons. “I think a lot of people probably don’t realize until you experience how exciting and almost frenzy-ish spring and fall are,” Tenorio said.

As a nonhierarchical group, BIPOC Birders allows anyone to organize a bird walk. Through their fiscal sponsorship from Friends of the Forest Preserves, the group utilizes funds to support event logistics, including van rentals for out-of-town birding trips, food for social gatherings, free loaner binoculars, field guides, and introductory education on birding basics. All events are free to attend and prioritize wildlife education and relationship building (with other humans and birds).

Another BIPOC Birders member, Milla Lubis, sees these investments in accessibility as an extension of the care and cultural awareness that comes from being in a BIPOC-only space.

“There’s not a pretension around skill level, and I think part of that is this cultural under-

of displacement and exclusion for historically marginalized people in outdoor spaces.

“It’s not only about the birds,” Abreu said. “We’re fighting colonial practices, we’re fighting inequality, we’re fighting the lack of access.”

The group embraces the intersectional identities of its members and prioritizes collaborations with organizations that are “aligned on [their] desire to create inclusive, accessible birding spaces,” Tenorio said. Chicago BIPOC Birders has done bilingual bird walks at public libraries, and one of their recent events with LGBTQ+ group Out in Nature was “Big Flock at Big Marsh,” a bird-themed drag show.

Tenorio emphasized how even small things, like normalizing everyone sharing their name and pronouns before walks, have made them

“We need to remember that birds migrate with the seasons, because that’s their calling for survival,” Abreu said. “There are birds that can only live in a certain type of weather, and there are resources that they need that only grow under certain conditions, and these conditions are being disrupted.”

It’s this love for the natural world that inspires the group to work in alliance with birds by advocating to stop bird collisions, engaging in bird banding for research and conservation, and educating others on the habits and habitats of birds.

In this way, BIPOC Birders are a flock of humans connected to a flock of birds through the earth they share and the desire to survive and thrive together. v

m letters@chicagoreader.com

Find more one-of-a-kind Chicago food and drink content at chicagoreader.com/food

The platter of mansaf bites at M’daKhan—a Bridgeview joint specializing in smoked meats— comes with eight pockets of fluffy rice and bits of lamb encased in thin flatbread, doused in sauce with more on the side, and garnished with herbs and slivered almonds. It’s a shareable, dippable version of traditional mansaf, a rice, lamb, and yogurt dish with roots in Jordanian, Palestinian, and other Middle Eastern cuisines.

creamy but fluid dip. For those familiar with the food of the Levant, jameed is rich and nostalgic. For newbies, it packs an unexpected punch of tanginess and umami, with a pleasantly lingering funk from the fermentation. In either case, you’ll find that a gentle dunk is insufficient, and that the bites—despite how quickly they lose structural integrity— can scoop entire pools of jameed into your mouth. Luckily, there’s plenty, so go ahead and taste it paired with fries, smoked lamb shank, falafel, and whatever else is on the table.

The sauce is the magic here: It’s made with jameed (aka kishk), fermented and dried yogurt balls, reconstituted into a

—TARYN MCFADDEN M’DAKHAN 9115 S. Harlem Ave., Bridgeview, $17.99, 708-229-8855, mdakhan.com v

Reader Bites celebrates dishes, drinks, and atmospheres from the Chicagoland food scene. Have you had a recent food or drink experience that you can’t stop thinking about? Share it with us at fooddrink@ chicagoreader.com.

By TATIANA WALK-MORRIS

On the night of November 19, residents from South Holland, Dixmoor, Dolton, and other nearby southsuburban communities gathered outside Thornwood High School. In a line extending onto the sidewalk, families gathered for a community resource fair hosted by Naperville-based utility company Nicor Gas, which provided free food packages containing fresh fruit, vegetables, rice, chicken, fish, and turkey. Once inside, the line wrapped around the school’s indoor running track. Stevie Wonder’s “What Christmas Means to Me” and other tunes played on loudspeakers. Sectioned o behind yellow-and-black striped tape were

booths from various nonprofits and government agencies, including the Illinois Department of Veterans A airs, the South Suburban Housing Center, the Salvation Army, and the Community and Economic Development Association (CEDA).

Events like this are where CEDA reaches out to low-income residents in Cook County who need help upgrading their homes to withstand the changing climate and conserve energy. The nonprofit is one of many other community organizations and government agencies in the state tasked with administering the Illinois Home Weatherization Assistance Program (IHWAP).

“We get some very nice letters from people

that are thanking us for the work,” said Nick Horras, CEDA’s director of energy conservation, in an interview ahead of the event. “I’d be remiss if I didn’t give credit to our contractors that actually do the work. We work with about a dozen single-family contractors and a handful of multifamily contractors that are really incredible partners in delivering this program.”

The IHWAP provides air-conditioning repairs and replacements, air sealing, attic and wall insulation, and a range of other services meant to reduce energy costs, according to the website of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (DCEO). The program, founded in 1976, is

federally funded and administered by the state.

Though homeowners seek help from local organizations, CEDA and state and local government o cials told the Chicago Reader that federal regulations governing the program have prevented many low-income homeowners from accessing its services. Applicants living in predominantly Black and Latine zip codes have been denied for the program at higher rates than those from the majority of Chicago’s white neighborhoods, according to a Reader analysis of applicant data. Meanwhile, thousands of homeowners elsewhere in the state linger on the program’s waiting list, a copy of the list shows.

Access denied

The U.S. Department of Energy launched the Weatherization Assistance Program in 1976 under the Energy Conservation and Production Act to help low-income families contend with rising utility costs and conserve energy. Today, the energy department provides funding to all 50 states to administer the program.

Illinois uses a scoring system based on criteria set by the energy department to determine which households are eligible for assistance, said Mick Prince, state manager for the IHWAP.

In Cook County, CEDA handles the applications, inspects properties to ensure they can be conserved, and hires contractors to repair, upgrade, and survey homes, Horras said. The organization also has a facility in South Holland, Illinois, where it trains people on weatherization and building science and supports workforce development initiatives.

Between 2018 and 2024, more than 4,100 IHWAP applications from Chicago homeowners were denied. Of those, more than half came from homeowners in predominantly Black zip codes, compared to less than 16 percent from majority white zip codes.

A DCEO spokesperson said that the local nonprofits and government agencies that administer the program have the final word on which homeowners are approved or denied. Neither the energy department nor the DCEO provides input into which households receive services, the spokesperson said, but the households are served “based on the priority of the household.”

Prince and David Wortman, deputy director for the DCEO O ce of Community Assistance, said in an interview with the Reader that they were not aware of the pattern.

Although CEDA conducts outreach and serves homeowners across Cook County, the pattern may be explained by some communities applying for the program more than others, Horras said. The program has income restrictions, and some communities may have a higher concentration of low-income applicants, he added. “There are some communities and some demographics, depending on where you are in the city and the suburbs, that you’re going to see a lower application rate from certain communities based on the socioeconomics, the demographics of that area,” Horras said.

The majority of homeowners are denied because they exceed the program’s income

limit, Prince said. Federal guidelines require that homeowners’ household incomes stay below 200 percent of the federal poverty line, per the DCEO website.

Though the poverty line is adjusted annually for inflation, the state doesn’t have the flexibility to use another metric, such as area median income, Prince said.

“[A] $23,000 annual income in Chicago is not the same as it is in Edwardsville—[a] southern Illinois community—but that’s the way the federal poverty level looks at it,” Prince said. “That doesn’t account for [the] high cost of living in di erent areas.”

Other homeowners are denied for failing to provide adequate documentation, Prince explained. He added that introducing an online application for the program has reduced that barrier. In some cases, applicants are deferred from receiving weatherization services because their homes are too worn down to upgrade, he said.

Within 15 days, CEDA tries to follow up with applicants who don’t complete the required forms, but the onus is on the client to provide the necessary documentation, Horras noted.

The organization has had to turn away homeowners if they’re even “a dollar over” the income limit, said Carolyn Hill, deputy director of weatherization at CEDA. Some homeowners express frustration, but the organization is following federal regulations beyond its control, Hill added. “Ideally, we’d love to be able to help everybody, but it comes down to, again, the funds that are available,” Hill said. “There’s not unlimited funding for the programs. So, given the funding sources that we do have, we try to maximize so that when we’re touching a home, we’ve done the most that we can for it.”

double the federal poverty line. To do this, the state is using federal grant funding from the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The IHWAP also uses funding from the state’s Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) to complete needed repairs, Wortman said.

The U.S. Department of Energy didn’t respond to the Reader’s request for comment. In response to the income barriers, Illinois plans to fill the gap and provide assistance to homeowners who earn up to 80 percent of the area median income, a higher threshold than

The DCEO uses these additional funds as part of its Weatherization Plus initiative, which aims to address the hurdles preventing homes from being weatherized. According to the 2025 IHWAP manual, the DCEO Office of Community Assistance must grant approval

for any Weatherization Plus improvements that cost more than $5,000.

The DCEO spokesperson said the department has this policy “provide a reasonableness check and to ensure proper procurement of services have been conducted by local weatherization administering agencies.” To date, the agency doesn’t have a record of denying a weatherization project exceeding that amount, they said.

Even as the state tries to work around federal restrictions and serve more Illinois homeowners, many homeowners are left waiting for

continued from p. 7

weatherization assistance.

In April 2025, the state had a waiting list of more than 3,000 IHWAP applicants, more than a third of whom were 60 or older, records show. By September, the list had grown to more than 4,100 applicants.

The waiting list had a high concentration of homeowners living in zip codes within Mitchell, Alton, Grandview, and Round Lake Heights, according to an analysis by the Reader. Prince and Wortman weren’t exactly sure why some small Illinois communities had a high concentration of homeowners on the list. The trend could stem from nonprofits or government agencies conducting IHWAP outreach in those areas, they said, as well as the concentration of eligible homeowners.

The waiting list changes daily, Wortman said. “Obviously, there’s more need for weatherization than what we could ever get done in a year,” Prince added. “The process from being on a waiting list, getting prioritized, getting a full application, so on and so forth, can take several months.”

The IHWAP prioritizes low-income households with residents 60 or older, children five or younger, and people with disabilities. About seven in ten homeowners served through the program fall into one of the priority groups, Wortman said. Despite e orts to assist more homeowners through the Weatherization Plus initiative, people whose homes need repairs before they can be weatherized can spend years waiting for help due to the energy department’s criteria. “If we have the ability to do 4,000 houses a year and we get applications from 6,000, five years from now, we’re going to have quite a few people that are still on that list,” Wortman said.

Such is the case for residents of Sangamon County, home to Springfield. Visitors to the county’s webpage on weatherization will see a striking disclaimer: “We currently have a two year waiting list but please call the o ce at 217535-3120 and asked to be put on the list. We will contact you when your name comes up.”

As of September 4, the zip code with the third-highest number of homeowners waiting for the IHWAP’s help was in Sangamon County, according to records obtained by the Reader. Dave MacDonna, executive director of the Sangamon County Department of Community Resources, attributed this elevated number to multiple factors. For one thing, the department provides home weatherization services for homeowners in both Sangamon and Macon counties.

Unlike in Cook County, the program rejects very few Sangamon County applicants based on their income, given that many people in the county live in poverty, MacDonna said.

Still, the o cials try to weatherize seven to eight homes per month. Homeowners seek services such as insulation, furnace repairs and replacements, and hot water heater repairs or replacements, MacDonna said.

The county takes homeowners’ applications to ensure they qualify, conducts home assessments, hires contractors, and reassesses homes once work is complete, MacDonna explained. The county has two home assessors, and inspections can take between four and five hours, MacDonna said. Once repairs are completed, homeowners see their home value increase, utility bills decline, and quality of life improve, he added.

“We’re getting to them as fast as we can,” MacDonna said. “We all wish that the waiting list was shorter, but when you’re doing that much work in a home, it’s not something that can go real fast.” MacDonna predicted that doubling his sta wouldn’t result in a shorter waiting list because the program remains popular and people can reapply after 15 years. “We have done so much already to improve and reduce the waiting list, and we’re still seeing a high number of people just because it’s such a great program,” MacDonna said.

Like in Illinois, organizations and government agencies providing home repair and weatherization in other states are working to fix up homes in underserved, underresourced communities, said Freyja Harris, CEO of the Coalition for Home Repair, a nonprofit based in Jonesborough, Tennessee, that supports home repair and rehabilitation organizations nationwide.

“Oftentimes, getting weatherization elements added—sometimes the funding doesn’t reach that far. They got to make sure that the hole is taken care of in the roof first, that other basic needs like plumbing and electrical and those sorts of things are just functioning appropriately,” Harris said. “If they are lucky enough to get that home into proper condi-

tion, then they can move forward with that weatherization. But it’s just sometimes the needs are just too great.”

As climate change intensifies, homeowners living in poorly insulated homes are at risk of death. Without access to home weatherization programs, that risk will intensify for many homeowners but particularly for older adults, communities of color, children, and other vulnerable people, Harris said.

In Chicago, some neighborhoods are especially vulnerable to climate change. Max Berkelhammer, professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago, has worked with homeowners in Chatham and Auburn Gresham, for example, because they have endured more flooding historically than other parts of the city, disrupting their basements and streets. West Humboldt Park, Austin, and communities on the northwest side have also had high rates of basement flooding, Berkelhammer said.

In conversations with Chatham homeowners, Berkelhammer said he’s heard about the aftermath of flooding, including electrical fires, mold, haggling with insurance companies, and the overall mental toll of the ordeal. Accessing weatherization assistance is critical for older homeowners, especially those who look after young children or who rely on medical devices to treat their illnesses, said Destenie Nock, assistant professor of civil and

environmental engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University. “I’m thinking of your CPAP machines or your oxygen machines. That’s also going to be very important to maintain an electrical supply to them and just, like, have that consistency,” Nock said. Older adults are more vulnerable to climate change due to their chronic health problems, said Arnab Ghosh, assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. They may also take prescriptions, like blood pressure medication, that make them more likely to be a ected by heat.

Home weatherization assistance programs will not only save homeowners money on heating their homes, for example, but they can also allow for upgrades that many wouldn’t otherwise be able to a ord, Ghosh noted.

“If you can weatherize your home, it’s going to cost less money to heat your home in the winter,” Ghosh said. “That’s particularly important again for older adults, particularly those who are on fixed incomes and are kind of worried. . . . Sadly, we know some households are so worried about this. They’re making decisions between whether they can feed themselves or warm themselves.” v

This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. m letters@chicagoreader.com

Federal immigration agents abducted a community member from an apartment complex in the western suburb of Elgin on Saturday, then used tear gas and flash-bang grenades to disperse a crowd of neighbors that had gathered around them.

The violence unleashed on an otherwise quiet, residential street marked the feds’ first use of chemical munitions in the Chicago area since protesters, media, and faith groups moved to dismiss a federal lawsuit that had sought to limit their use. (Full disclosure: I submitted a declaration for the suit, and our editorial union, the Chicago News Guild, was a plainti .)

The hourslong standoff began after a car driven by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents collided with an Elgin man’s car. The man then reportedly fled to a nearby apartment complex and refused to leave. That’s when a crowd of neighbors, community rapid responders, and elected o cials began to gather.

Live feeds of the confrontation posted to social media show agents violently shoving and tackling people, carelessly tossing flashbangs near families, and deploying tear gas with little warning.

A couple of the roughly dozen federal agents at the scene wore green vests with patches that read, “ERO,” which stands for Enforcement and Removal Operations, the division of ICE tasked with arresting and deporting immigrants. At least one agent was spotted wearing a patch that identified him as a ground tactical air controller (GTAC), a role focused

on “air-to-ground communications” that links “law enforcement units with intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance information.”

investigating. And the company has faced mounting public backlash in recent months after one of its cars killed a beloved bodega cat in San Francisco. (Waymo has argued its cars are involved in fewer accidents than cars driven by humans.)

More than that, though, Waymo is a workers’ rights issue. As Reader social justice writer Devyn-Marshall Brown (DMB) reported in his October cover story, “Illinois rideshare drivers organize for labor rights,” companies like Uber and Lyft upended Chicago’s taxi industry and made a fortune off a shadow workforce that lacks basic job protections and benefits. It makes sense that the next step would be to replace those pesky workers with robots.

I don’t know about y’all, but I don’t want any more clankers on our streets. —SHAWN

—SHAWN MULCAHY

The GTAC program is run by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), an agency separate from ICE but also part of the Department of Homeland Security CBP also houses U.S. Border Patrol , whose agents under Greg Bovino terrorized Chicago earlier this fall—and clearly will continue to do so.

As if glowing-eyed, burrito-bearing robots barrelling down Chicago’s sidewalks weren’t awful enough, California-based Waymo reportedly wants to send its self-driving cabs barreling down DuSable Lake Shore Drive.

According to the Chicago Tribune , the driverless car company—a subsidiary of Alphabet , Google ’s parent corporation—is in talks with several state lawmakers about bringing its rideshare service to Illinois. Multiple bills on the issue have been introduced in the General Assembly, but so far, none have made any progress.

Waymo’s rideshare service currently operates in five cities, Los Angeles and Austin among them, and will soon expand to more than 20 additional locations, including Saint Louis and Philadelphia. Brad Stephens, a Republican state representative and the mayor of Rosemont, hopes his town is next. He introduced a bill that would allow Waymo to pilot driverless cabs around O’Hare International Airport , Rosemont and near suburbs, and Springfield.

State representative Curtis Tarver, a Democrat from Chicago, also supports bringing the technology to Illinois. Tarver told the Tribune that self-driving cars “don’t have the same errors as humans.”

Yet, earlier this week, Waymo announced it was recalling software on all its vehicles following multiple incidents in which the company’s cars illegally passed stopped school buses. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is also

has not only a rmed our shared values—it’s a commitment to the future of The Book Cellar,” wrote organizing committee member Jack Welsh. “We believe this union will help strengthen our workplace and ensure that The Book Cellar continues to provide quality books by first time authors and local authors, unique book clubs, and more to enhance our community for another twenty years.”

Suzy Takacs opened the Book Cellar in June 2004. The shop has hosted the Chicago Writers Association ’s annual Book of the Year Awards since 2011.

MULCAHY

Booksellers at the Book Cellar have unionized. On November 24, sta at the independent Lincoln Square bookstore announced that they successfully organized with the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1546.

In a press release, workers say the decision to unionize reflects a desire for fair wages, consistent scheduling, and a voice in decisionmaking about their jobs. “Organizing ourselves

As union members prepare to negotiate a first contract with their employers, they’re calling on the Book Cellar’s community of “readers, writers, and regulars” to support however they can. On Saturday, December 6, the group distributed bookmarks and talked to patrons about how they can support the e ort.

The union is doing it again on Thursday, December 11, during Shop Late Lincoln Square “Stop by to chat with us, and go pick up a book and tell a bookseller you support the union!” they wrote on Instagram.

Find the Book Cellar Workers Union on Instagram at @bookcellarworkersunion.

—DEVYN-MARSHALL BROWN (DMB) v

Make It Make Sense is a weekly column about what’s happening and why it matters. m smulcahy@chicagoreader.com

The Chinese American Museum of Chicago presents an unexpected pairing of work by Ruyell Ho and Li Lin Lee.

By KERRY CARDOZA

Other than their backgrounds and their eventual emigration to Chicago, artists

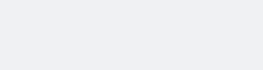

Ruyell Ho and Li Lin Lee may seem to have little in common. Over a career spanning more than 60 years, the China-born Ho has worked across photography, painting, and sculpture, among other mediums. He works primarily in biomorphic abstraction, abstracted compositions that resemble living forms; his lines and shapes are bold and buoyant. Lee, born in Indonesia to Chinese parents, has worked in painting, printmaking, and collage over the past 40-plus years. His pictographic, dreamlike forms emerge intuitively, often in muted palettes. But in “Language of Abstraction,” on view at the Chinese American Museum of Chicago (CAMOC), curator Larry Lee makes the case for putting the artists’ work in conversation.

“[I] just wanted to reintroduce both these artists who have been working without fail,” Lee said. The more he thought about their work, the more he realized that their shared background in language and “the tradition of the calligraphic” had a strong resonance. “For them, that probably stemmed from the fact that they were trained using a brush as not only a writing but painting tool,” he said.

Lee grew up near CAMOC’s current location and has a near-encyclopedic recall of Asian American artists and movements, particularly those with ties to Chicago. “We actually call Larry the cultural memory,” Caroline Ng, CAMOC’s executive director, told me.

Lee has long been inspired by both Ho and Lee’s work. “[I] was a little bit sad that people maybe didn’t have as much knowledge about their work, who they are, the contributions that both artists have made, and the influence and vice versa of their work on Chicago,” he said. “Language of Abstraction” sets out to change that.

The exhibition, installed on the museum’s first-floor gallery, is expansive but tight, o ering important examples of both artists’ work alongside sketches, journals, videos, and timelines of their lives and careers.

Li Lin Lee was born in 1955. He moved to

the U.S. in 1962, studying biochemistry at the University of Pittsburgh before eventually switching to art and settling in Chicago. Lee works in layers, adding and subtracting to his paintings, collaging materials together in his monoprints. He likes to work on a relatively small scale, so that the viewer can take in the whole composition at once.

A series of oil and mixed-media paintings on burlap from the past six years features geometric shapes on textured vertical rectangles executed in rich brown, deep purple, pale yellow, and muted greige. The Astronomy Lesson (undated) is in tune with Surrealism while feeling undoubtedly contemporary; in the left section of the painting, a blue orb hovers below a coral-like motif, on a yellow background, while the right is cast in black, with striped UFO-like shapes partly in view.

Samples of paintings, displayed in glass vitrines, that show Lee working in brighter shades—hot pink, aquamarine—could be studies for a 2025 series of monoprints, larger-scale works made by cutting out and stenciling over many sheets of Thai mulberry paper.

R“LANGUAGE OF ABSTRACTION”

Through 4/26/26 : Wed and Fri 9:30 AM– 5 PM, Sat–Sun 10 AM– 5 PM, Chinese American Museum of Chicago, 238 W. 23 rd St., camochicago.org

accents. They are glyph-like but mysterious, as if playfully trying to communicate.

Ho was born in Shanghai in 1935. He moved to Chicago in 1960, taking art classes at the School of the Art Institute with Ray Yoshida, mentor to the students who would become the Chicago Imagists. In the mid-70s, Ho helped cofound Chicago Artists Coalition and in 2003 cofounded the long-running Artist Breakfast Group. His daughter, Amanda Ross-Ho, who is also an artist, is the archivist of her father’s work; her own work often draws from his life.

“Language of Abstraction” excels at establishing Ho and Lee’s importance in the Chicago art world. “We hope [this exhibition] will transform how the public sees the museum, from this sort of neighborhood,

and then when they see our gallery upstairs, they think, ‘Oh, it’s all new. It’s all young people.’ But it’s not new. Ruyell’s turning 90,” Ng said. “So for me, it’s exciting that we get to insert this into the Chinese American story and also the Chicago art lexicon.”

A small gallery on the museum’s fourth floor hosts the ongoing Spotlight Series, also curated by Lee, that features work by local emerging and mid-career artists of Chinese descent. Since its launch in 2022, the series has garnered critical praise, exhibiting notable artists such as Adrian Wong, Guanyu Xu, and Cathy Hsiao.

It can be a challenge to make the case for the inclusion of contemporary art in CAMOC’s schedule, Ng explained. Part of her job is to make their programming accessible to the local community and its ever-changing demographics. “[There is] this whole chance to expand the historical record in a layered way, to tell more stories,” she said. And while their new programming, like their Pride Month series, may not be for everyone, Ng is heartened by the response overall.

Across the gallery, Ruyell Ho’s well-defined nonrepresentational shapes appear to be in midmotion. A suite of four large-scale acrylic paintings, from the late 80s and early 90s, seems equally inspired by the Imagists and graffiti. In bright primary and secondary colors, Ho anthropomorphizes shapes into expressive, busy designs, like Memphis Milano furniture rendered flat.

I was particularly drawn to two wallmounted acrylic on foamcore pieces from 2015, both large black shapes with red or pink

community-based legacy project . . . to something that looks forward,” Lee said.

He proposed the show to Ng shortly after she stepped into her role, almost two years ago. She quickly put the wheels in motion; everything came together in around six months, a very condensed time frame for such an extensive exhibition.

“This was something we really wanted to do because I think when people think contemporary art, they don’t think of Chinese people,

“I do think there’s a lot of opportunity, a lot of gaps to fill,” she said. “We still can contribute to the conversation from a particular point of view and open it up for more than what is expected. . . . People are looking for more, so how to make the space relevant? How to make these historical things matter?” After all, as Ng put it, “History is still happening.” As a show by local, living artists who helped create Chicago’s cultural scene as we know it today, “Language of Abstraction” deftly presents stories that are both current and historically important. It also helps illustrate the museum’s mission to foster intergenerational dialogue on the Chinese American experience. While Ho and Lee have both spoken about their hesitation for their work to be labeled according to their ethnicity, their experiences nonetheless resonate across generations. v

m kcardoza@chicagoreader.com

The Orbit at iO puts long-form improv in the round.

By ROB SILVERMAN ASCHER

alling Chicago a “comedy city” is boring in 2025. Yet the city’s comedy laboratories are still experimenting, mixing the old with the new. That’s the case with The Orbit, a new long-form show running at 9 PM on Wednesdays at iO.

“This format draws from a lot of old-school long-form techniques and training that I received coming up in the 90s,” says improv stalwart Liz Allen, the show’s director. “But [we] didn’t want to retread all the old ground. I wanted to create new stu with new people.”

The Orbit ’s eight improvisers, performing in the round, rely on fades and overlapping scenes, not hard resets. “One scene sort of dissolves verbally while another scene starts physically,” Allen points out, fostering experimental, artful improvisations.

The Orbit originated with an empty theater. When Dan Wilcop, the show’s stage manager and iO’s technical director, first walked into the Dayton studio at iO (one of five performance spaces in the theater) and saw there was no stage, he was struck by the idea of an improv show in the round. The unconventional use of space was inspired by Wilcop’s tenure with the Shithole, an underground variety show he ran around Chicago for years.

Wilcop says the concept stayed “in the back of my head” until he mentioned it to Riley

The

Orbit in performance at iO

RACH GRANILLO

Woollen, an iO regular. Woollen couldn’t stop thinking about it and shared Wilcop’s idea with improviser Zach Reynolds at a party. “I remember walking around bringing people drinks and stuff,” Reynolds recalls, “just obsessing over the concept.” When the three began developing the show, they pitched Allen on the format.

“We knew we wanted it to be improv in the round, but it didn’t really come together until we brought Liz on,” Woollen says.

“The ironic, synchronous part of all of this,” Allen says, “is that I’d been kicking [that idea] around for a while,” inspired by casino shows she had seen while working in Las Vegas.

According to Reynolds, the shape the show takes “is a little bit less rigid” than most improv shows. Woollen mentions “a strange kind of overlap not seen in many other forms. We’ve literally done four scenes on top of each other.” Allen says that the show combines “elements of all classic long-form” improvisation, but with twists.

Notably, the cast sits, heads down, at a central table rather than resting at a back line upstage. The Orbit is a real “everything old is new again” situation, altering the rules of the Harold (first developed by San Francisco comedy troupe the Committee and further refined by Chicago improv legend Del Close

THE ORBIT Open run: Wed 9 PM, iO Theater, 1501 N. Kingsbury, 312-300 -3350, ioimprov.com, sliding scale $7 80 -$17 80

at iO with his partner, Charna Halpern) and creating a form of its own. Reynolds puts The Orbit’s relationship to the Harold succinctly: “You learn what the car is, and then you drive it.” (The Harold emphasizes patterns, themes, and group discoveries that spin out from a single audience suggestion, rather than building narrative scenes to tell a single story.)

Something notable about The Orbit is that its scenes often play earnestly, rather than chasing after a bit. Reynolds says that “balancing real and genuine relationships” with humor is central to The Orbit . When asked about this tendency, Wilcop credits Allen’s insistence on vulnerability. “Liz really pushes us to be sincere, and from that, the funny comes out.” Reynolds agrees. In rehearsal, “If we’re stuck in a scene, she asks us to say something true or confess something to unlock a scene.”

“In an ideal show,” Reynolds reflects, the “bittersweet moments give us a little more canvas. . . . If it’s all too comedic, the show becomes narrow.” Allen credits improv dogma for the show’s earnest elements. “The classic view of improv is that you never want to aim for comedy. Unexpected discoveries of comedy are what we aim for.” For Allen, vulnerability is central to an improv group’s dynamic. “In order to have a fruitful collaboration, all members have to feel safe and protected in the group. When people know they’ll be supported, they will act on impulse.” What Allen describes as “an impulse to contribute to the creation” is an engine for the cast of The Orbit. Impulsive creation is exemplified by a segment Reynolds refers to as “organic improv,” a sound and movement extravaganza recalling heady 1960s experimental theater. These moments (Reynolds also calls it “witchy stu ”) serve as transitions, legible words morphing from nonsense sounds and then back to dialogue that initiates a new scene. Reynolds and Woollen admit that this element did not come naturally to them at first. “There was a learning curve for us. We miscalibrated on that component.” Woollen notes that there were shows “where we were just screaming the whole time” early in the show’s run.

Wilcop’s lighting design, a visual live score accompanying the action, is also key. While he initially describes his process as “just vibes,” Wilcop explains that thinking about how he can influence the performers is his focus. “How can this be a conversation? How do I create [that] push and pull that helps the back-and-forth?” The cast frequently takes cues from Wilcop’s lights, a significant shift from the static full wash seen in most

improv shows. “Our heads are down a lot of the time,” Reynolds says, “so we’re not even able to see what’s happening. We have to follow our impulses on something that we hear, or maybe we see out of the corner of our eye, or a change that Dan made.” Wilcop’s lighting design also serves his needs as a stage manager. Woollen points out that “Dan writes the last sentence. Depending on when Dan decides to pull lights, it can be a completely di erent show.”

At 8:40 PM last Wednesday in the Dayton’s green room, Allen runs the cast through a long written list of both traditional improv and Orbit -specific techniques. After some threeline scenes and object work practice, Allen and the cast (Woollen mentions that they’ve done The Orbit with as few as three cast members but always aim for the full eight) head into the Dayton to reset the house. Wilcop pulls out a ladder, making last-minute adjustments to the lighting grid as the cast sets the table in the middle, covering it with a black cloth and placing bistro chairs around it. All told, the Dayton’s transformation takes about five minutes.

Once Wilcop kills the lights, the cast enters, circling the table and soliciting a “favorite winter activity” from the audience. They take their seats, echoing that activity with a gesture, bringing us right into the first scene. “It’s di erent from any improv I’ve ever done, but I have to use all the improv I’ve ever done,” says cast member Erin Washington. Annie Scott echoes that challenge, adding that “nothing is set except we start at the table.” Louie Cordon refers to The Orbit as a “bottomless form” where “there’s a lot of depth but it all feels tangible.”

What’s next for The Orbit ? The plan is to run indefinitely in their Wednesday slot and let the form evolve. “I really think it [will] be something totally di erent a year from now,” Woollen says. “Not better, not worse, just di erent, and that’s exciting.” Allen believes that, “after a six-month run, we [will] know the form inside and out, but still make discoveries.” As The Orbit establishes itself as an artful, subversive show, borrowing from improv’s roots while also innovating, it could become a Chicago staple like the Neo-Futurists’ The Infinite Wrench, drawing repeat audiences and building a cult following. All The Orbit team can do now is get their reps in and enjoy the kismet of it all. “I just think it’s cool we got the name right,” Woollen says. v

m letters@chicagoreader.com

RSurface and symbol

Dorian connects fiction and fact in its picture of Oscar Wilde.

“All art is at once surface and symbol,” wrote Oscar Wilde in the preface to his 1890 novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. It’s a paradigm embraced with queer gusto and no small degree of pathos in Dorian, the 2021 adaptation by Phoebe Eclair-Powell and Owen Horsley first created for Reading Rep in the UK, and now at Open Space Arts under Aaron Holland’s direction.

Simultaneously smart and facile, the show tells the entwined story of the novel and of Wilde’s own doomed relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, or “Bosie,” which led to his imprisonment in Reading (and thence to his “Ballad of Reading Gaol”). Three actors play characters in Wilde’s book and his life with obvious mirroring of their natures (or what they want us to think their nature is, which is, of course, the point of the surface-and-symbol observation). Dorian was the person Wilde said he most wanted to be; doomed painter Basil Hallward was who he really was; and the poisonously witty Lord Henry Wotton was how the world saw him. Here, Anthony Kayer plays both Oscar and the preening Lord Henry, while Luke Gerdes is both petulant Dorian and Bosie, and Brian Kulaga plays Basil as well as Wilde’s loyal friend, Robbie Ross.

Holland’s bold direction spills out all over the tiny basement room at Open Space Arts as the narrative splits and fragments into a kaleidoscope of observations—not just on Wilde’s life and art, but also on queer culture through the ages. At points, Kulaga’s Ross, with his pleas to Oscar to be more careful about how he conducts his sex life, resembles a less abrasive Larry Kramer, whose calls for gay men to abstain from casual sex in the early days of AIDS made him a hated figure to many. Music, dance, puppetry (the judge in Wilde’s trial for “gross indecency” looks like a repressed Muppet), and more take the stage to highlight the fast-moving story. At points, the cast recites the “Victorian Homosexual Quiz,” containing such questions as “Is your wrist flat or round?” and “Do you whistle well, and naturally like to do so?” giving us a snapshot of the arbitrary standards of masculinity haunting the Victorian age (and our own). Though Wilde’s personal story and that of arguably his most famous creation remain tragic, Dorian also reminds us of the defiant wit the artist used as a cudgel against hypocrisy and mediocrity. Stylish, gritty, funny, and bold, it also reminds us that “the truth is rarely pure, and never simple.”

—KERRY REID DORIAN Through 12/21: Fri–Sat 7:30 PM, Sun 2 PM; Open Space Arts, 1411 W. Wilson, openspacearts.org, $30 ($25 students/seniors)

Gaslight at Northlight is a satisfying thriller.

If you dread facing your controlling family members this holiday season, maybe a trip to Northlight to see Steven Dietz’s Gaslight (directed by Jessica Thebus) is just the ticket you need. Based on Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 Victorian thriller, Gas Light (twice turned into a film, and which gave us the phrase “gaslighting”), Dietz’s version lightly contemporizes some of the dialogue and effectively streamlines the action. The result is a psychological thriller that gives its cast ample opportunities to

dig into the twists and turns of the story.

Bella (Cheyenne Casebier) is the wife of Jack (Lawrence Grimm), whose early soothing attentions to her soon shade into something far more sinister. Is Bella really mentally fragile, or is Jack trying to drive her crazy? The arrival of Scotland Yard’s Sergeant Rough (Timothy Edward Kane) at their Manhattan home gives her the answer: Bella, you in danger, girl. Collette Pollard’s somber Victorian set and JD Lederle’s lights (crucial to the story, as the name implies) provide a rich atmospheric backdrop for Thebus’s cast.

Kane is a comic delight as Rough, but never veers into pure cartoon, even as he delivers scads of (well-cra ed) exposition and calls attention to his bright blue “saucy shirt.” (Raquel Adorno’s costumes are also spot-on.) Grimm brings oily charm and cold calculation to Jack, and Casebier’s Bella has enough starch in her spine for us to cheer on her quest to free herself from Jack’s machinations. It’s an engaging take on a classic that feels fresh and nostalgic at the same time.

—KERRY

REID GASLIGHT Through 1/4/26: Tue 7:30 PM, Wed 1 and 7:30 PM, Thu–Fri 7:30 PM, Sat 2:30 and 7:30 PM, Sun 2:30 PM; no shows Wed–Thu 12/24-12/25; audio description and touch tour Sat 12/20 2:30 PM, open captions Fri 12/19 7:30 PM and Sat 12/20 2:30 PM; North Shore Center for the Performing Arts, 9501 Skokie Blvd., Skokie, 847-673-6300, northlight. org, $46-$98 (students $15, subject to availability)

The Real Housewives of the North Pole delivers seasonal camp.

Bravo’s Real Housewives franchise has captured the hearts and minds of the people with its (allegedly) candid portrayals of ridiculous people on various trips and through forced socializing. David Cerda of Hell in a Handbag understands the dramatic potential of the Housewives, transporting audiences to the heart of the Christmas industrial complex with The Real Housewives of the North Pole. A er a financial scandal lands several Christmas figures in jail, newly sober Ruth Claus (Honey West) takes Andy Cohen (David Lipschutz) up on his offer of a spot in the cast of Bravo’s newest franchise. Cerda’s play, as directed by Tommy Bullington, does an excellent job of finding the drama, both real and staged, among these women as they put the first season of their show together. The rivalry between the vain and callous Gladys Dasher (Cerda) and the sultry ingenue Clarice (Anna Rose Steinmeyer), Rudolph’s wife, is a highlight. RHONP’s cast breathes Cerda’s archetypes to life, from pious Christian Samantha Snowman (Robert Williams), who has taken up husband Frosty’s magical hat business, to party girl Suzy Snowflake (Britain Shutters), who has a side hustle selling Adult Party Diapers. Lipschutz renders Cohen a perfect slimeball, orchestrating conflict while huffing “medicinal cocaine” prescribed by Dr. Oz. Marquecia Jordan’s costumes capture the trashy “loud luxury” of the Housewives, and Syd Genco’s makeup and Keith Ryan’s wigs are the perfect complement. The Real Housewives of the North Pole is high clown camp, a steaming hot toddy delivered just in time for the season.

—ROB SILVERMAN ASCHER THE REAL HOUSEWIVES OF THE NORTH POLE Through 1/4/26: Thu–Sat 7:30 PM, Sun 3 PM; also Sun 12/21 6:30 PM and Mon 12/22 7:30 PM; no show Thu 12/25; the Clutch, 4335 N. Western, handbagproductions. org, $44.25 (VIP reserved seating with drink ticket $56.25) v

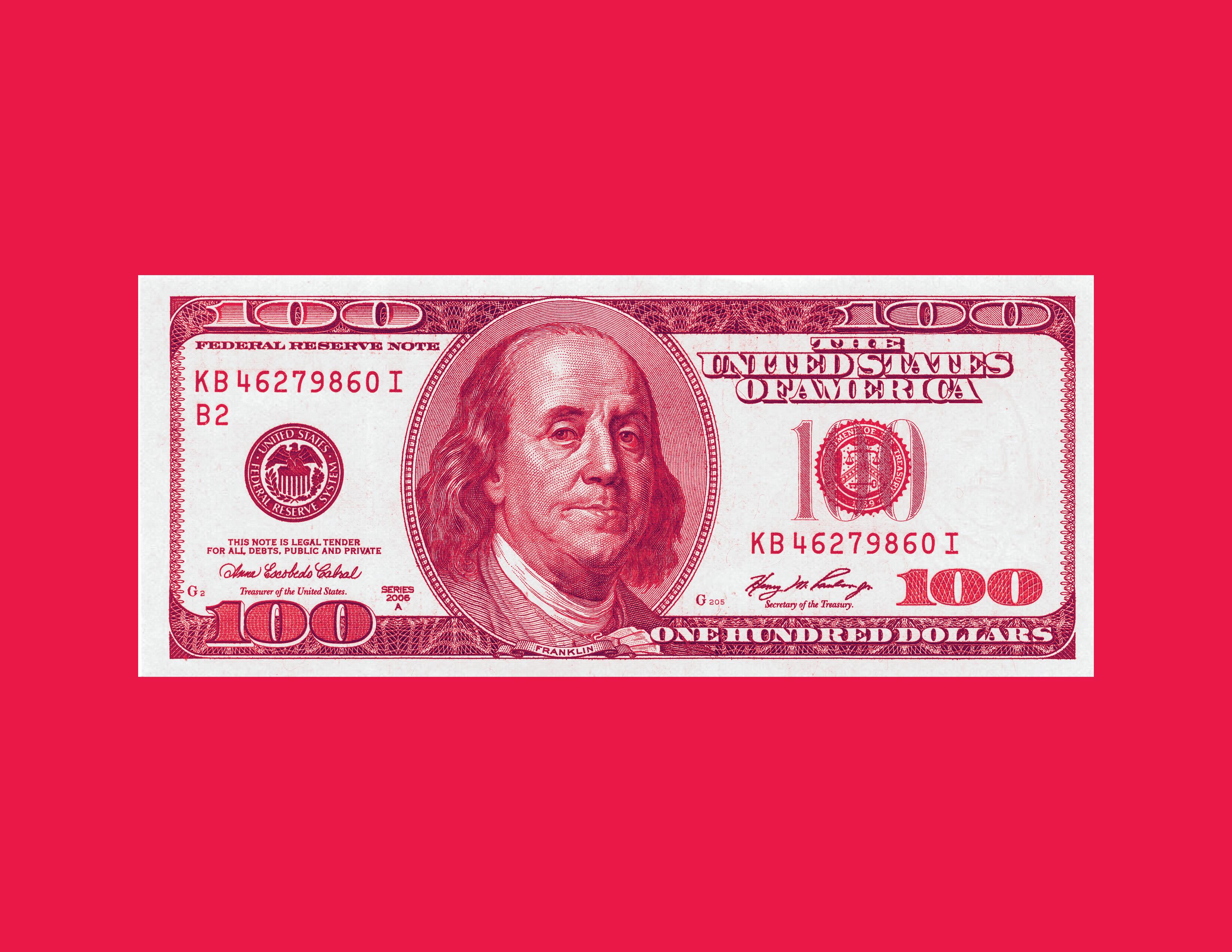

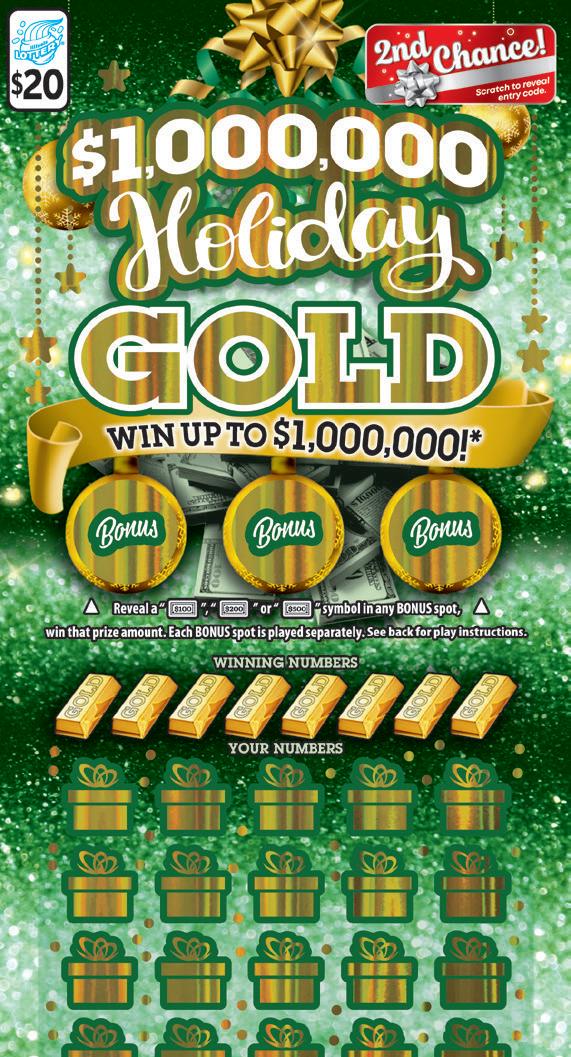

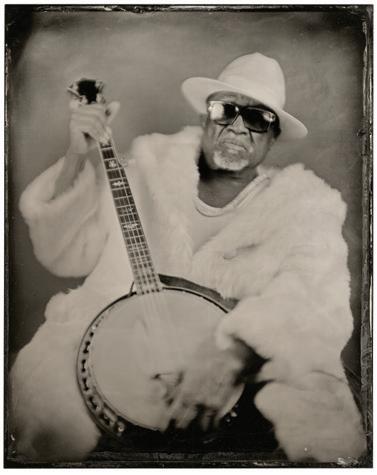

Dennis Scott is one of Chicago’s undersung legends. He’s the house organist for the Music Box Theatre, where his whimsical, charming music can be heard between screenings and accompanying silent films. Scott cut his chops playing organ at pizza parlors—a fad during the 1970s and ’80s—and first played at the Music Box in ’92. His day job in computer graphics prevented him from consistently performing there until 2009, when he became a regular presence.

Scott’s job involves an unusual feat of improvisation: He needs to bolster the emotions of any film, sometimes without seeing them beforehand, while ensuring the focus never

RTHE 42ND ANNUAL MUSIC BOX CHRISTMAS SING-A-LONG & DOUBLE FEATURE White Christmas ( 1954) and It’s a Wonderful Life ( 1946), through Wed 12/24, Music Box Theatre, 3733 N. Southport, musicboxtheatre.com/series-and-festivals/the- 42nd-annual-music-boxchristmas-sing-a-long-double-feature

By JOSHUA MINSOO KIM

Joshua Minsoo Kim: What early memories do you have of engaging with the arts? Did your parents encourage it?

Dennis Scott: My father could not have cared less. [Laughs.] As long as he could find a place to go fishing, the rest of the world could take a hike. There was no support there whatsoever. My mother had a passing interest in it. She wasn’t enthusiastic about it—she wasn’t a stage mother—but she liked to paint, and she encouraged that. She wasn’t really interested in my music much until I was out of college and had moved here. I was invited back to Tulsa to play an organ program, and she was surprised. She said, “I never knew that you had such an interest in music; I thought it was just a hobby. I hope you never give it up.” I was probably in my mid-20s then.

What was it like to hear that?

rests on him. While his job may seem thankless, moviegoers frequently praise him for his work, especially in December when he accompanies films in the Annual Music Box Christmas SingA-Long and Double Feature. The tradition continues this month, with dozens of showtimes until the final screening on Christmas Eve. I called Scott on the phone to discuss his life and work. We talked about his early memories of playing the organ; his mentor, John Muri; and the joys that come with playing during the holiday season.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

It was really rea rming since there had never been any particular support from either of my parents. Even as a kid, we didn’t have a piano or an organ until my dad bought a small electronic organ for himself when I was about 13 or 14. That was my first instrument. I always had an interest in piano and keyboard—I would go to neighbors’ houses and ask if I could come in and pick out tunes on the piano, which they allowed me to do. That’s how I got started. My dad’s oldest sister was visiting us one time from Arizona, and she heard me playing and said, “How long have you been taking lessons?” I said, “I’m not taking lessons.” “Why not?” “Dad won’t pay for lessons.” She went to my mother and said, “Go find a teacher for Dennis, and I’ll pay for his lessons.” I had lessons for about two and a half years. And then this aunt, who was much older than my dad, died, and that was the end of my lessons. Back in those days, in the 1950s and early ’60s, my mother was a housewife and didn’t work, so she didn’t have the money to send me to lessons. Everything I did from that point was self-taught.

Do you remember the organ that your dad bought?

It was a Thomas organ—a pathetic little thing. [ Laughs. ] It had the worst sound you could imagine. It had one manual [or keyboard], and it wasn’t even a full one; it was like half of a spinet organ. It had 13 pedals, and it also had a turntable at one end. It came with 48 lessons and an album of records with these lessons, and that’s really how I started. I got through lesson 48, and my dad was only on lesson two or three. He worked nights, so when he left for work, I’d play. Did you see The Holdovers [2023]? Remember at the party, when they’re at someone’s home—in their family room, there’s an organ identical to the one we had. Of course, that was supposed to have taken place around 1960, so it was historically correct. I thought all of those things ended up in landfills years ago. [Laughs.]

When were you born?

November 1946.

Do you remember seeing musical accompaniment to films when you were younger?

I didn’t see many films accompanied by theater organ until I became interested in theater. I grew up in Tulsa. My older brother lived here in Chicago. When I started taking organ lessons, he went to Rose Records on Wabash— which, even after it was taken over by Tower Records, they still referred to it as the Rose Store because it had been there for so long, and all the Rose employees still worked there. He went there in 1960, and they had a theater organ recording department. Somebody bought theater recordings—that was unusual for a record store. He sent me a whole stack of records for either my birthday or Christmas, and they were all theater organ instead of electronic or Hammond organ recordings. Two or three of the recordings were made by

people who eventually became close friends of mine.

I joined the American Theatre Organ Enthusiasts, who eventually changed their name to the American Theatre Organ Society, around 1970. I came to their national convention here in Chicago in 1969. I heard silent movies being played, including one by my mentor, John Muri, who became my dearest friend. He had played in the silent-movie era during the 1920s. I saw him many times accompany silent films. He also recorded many silent film scores for Blackhawk Films, which is now part of Kino Lorber.

He was never my teacher—I never formally took lessons from him—but he was my mentor. I would go to a lot of his silent movies and look over his shoulders. I’d go to some of his rehearsals too, so I’d see the process of preparing to play for a silent film. And then I’d be there for a performance so I could see what he actually did. That in itself was an education. And occasionally we’d talk, and he’d give me bits of information, like, “Try not to play music after the film was made if you want to be authentic about it. Don’t put published songs into dramas because it’ll detract from the story, but you can do them in comedies.” He said, “All these rules can be broken from time to time, but these are all general rules.” That was my first introduction to silent film because you never saw them on TV back in those days.

What’s the protocol for playing along to a movie? Do you have to see it beforehand?

If I really have time, I like to see it once. If there’s another score, I’ll listen to it while I’m watching it. If there’s no score, I’ll take it to the organ and play along with it, and then I see it again and perform it. Years ago, I asked John how he would prepare for a film back in the old days when he was working in the theater. He worked six days a week and had Wednesdays off. He played from the first show around noon until the last show in the evening, and he made good money doing that. I asked him, “How much time would you have to prepare for a movie?” And he told me that a film truck would pull up to the theater in the morning, they would drop o the film cans, one of the ushers would take the film cans to the booth, the projectionist would thread the machine, and he’d play the matinee. He’d play it cold. He’d say, “Hopefully I had it under my fingers by the evening shows.” In those days, they changed films maybe twice a week, so a film would play for two or three days.

I’ve had this happen at the Music Box. We’d get a film in, there’s no screener, and the film might come in on a Friday night, and I’d have to play on Saturday morning. If they had time, I’d come in early, and they’d play the first reel and the last reel, or at least the first few minutes of the opening scene. I’ve heard organists from the old days say that if you can get into and out of the film, the rest of it more or less takes care of itself. But there have been a few times that I’ve had to play films cold. And truth be told, it’s fun to do. [Laughs.] It’s a challenge. After you play them for so many years, you learn how to do that.

Is there a particular film you had to go into cold that proved especially challenging?

I worry about every one of them. [ Laughs. ] Some days you’re just not inspired to do much, but once the theater goes dark and the movie hits the screen and the audience is sitting behind you . . . something clicks, and I get into a di erent gear mentally. Sometimes I don’t know where it comes from. “How’d I pull that one out of the hat?” [ Laughs. ] I try to keep each film fresh. I don’t do the same themes. I’ve seen organists who play the same figurations for every film, but I try to come up with themes that fit the film, fit the mood. If it’s a period piece or a costume drama, I’ll try to come up with sounds that fit into that. I played a Japanese film a few years ago at the Music Box: [Yasujirō] Ozu’s An Inn in Tokyo [1935]. I went on YouTube and found a video with Japanese popular music of the 1930s. I listened to that just to get the flavor of it. Some fella came up to me afterwards and said, “Where’d you find that score?” I told him, “Truth be told, I just made it up.” “No, no, no, that’s authentic Japanese music. I’m a Japanese scholar.” I told him what I did, and he said that I had him fooled. I told him, “Why are you

paying attention to the score! You should be paying attention to the film. I failed!” [Laughs.]

Do you remember the first film you accompanied on the organ?

In another life, I was working in a pizza parlor playing a pipe organ. This was in Michigan, and the owners wanted to do silent films every night. They wanted to do a couple two-reelers. That’s where I developed my chops.

What was the name of the pizza parlor?

It was Pizza and Pipes in Pontiac, Michigan. After they closed, I played at a local restaurant. That was my career at the time. I couldn’t get into the music department at the University of Tulsa because the teacher I had for two and a half years was not state-accredited; they didn’t even let me audition for the music department. I was a journalism major, so I have a degree in that. I worked in public relations and did administrative work for a few years, and then accidentally fell into a music job. I was at a National Association of Music Merchants convention here in Chicago back in 1976. I was at the Thomas Organ Company hospitality suite and everyone was getting pretty well smashed. Someone said, “Dennis, come on and play something!” So I played for a few minutes, and this fella, who was the director of product development [and] also an organist, walked over to me and said, “How would you like to go to work for us as a product specialist?” I said I’d think about it for a while. I honestly didn’t give it another thought, but then, a week later, my phone rang at work, and he said, “What do you think?” “I thought you were kidding me!” At that point, I was 29 years old, and I thought, you know, I always wanted to work in music, and I’ll probably never be asked again. And the job I was in was a job that

I really liked, but I knew that I’d gone as far as I could go—I could sit in that same chair until I was 65.

So I took the job. It only lasted about a year because the organ company went out of business, but in the meantime, I traveled around the country playing in music stores. I was doing training programs for dealers, telling them how to demonstrate and sell organs. I ended up getting a job in San Francisco. They had pizza parlors there, and I was playing at one in Daly City at the Serramonte shopping center. It was a chain of three restaurants— one in Daly City, one in Redwood City, and one in Campbell. Then I got a job o er in Pontiac that was for a lot more money, and I was there for about seven years. After that, I moved back to San Francisco, and after five years there, I said, “I’m too midwestern to live here.” [Laughs.] I moved back to Chicago in 1992.

How did you land the Music Box gig?

I told my brother that I was going to move back to Chicago, otherwise I’d be doing a swan dive off one of the bridges—my choices were the Bay Bridge or the Golden Gate. [Laughs.] I had around $200 in my pocket; I had a piano and organ and records and books and furniture and put them all in storage. I got on a train and came back to Chicago. I worked with a friend here doing pipe organ maintenance and repair for a few months. I was studying computer graphics when I was in San Francisco, and I got my first computer graphics job in ’92, and at the same time, I started to work at the Music Box. Then I changed graphics jobs and went to work at a movie theater chain, Classic Cinemas, and was their graphic artist for almost 14 years. It got to be too much to work that job at Downers Grove and then at the Music Box on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. I was working seven days a week.

continued from p. 15

I had to give up the Music Box. Classic Cinemas had the Tivoli Theatre in Downers Grove, and I’d play down there on Friday nights. After I finished up my job, I’d play a couple intermissions and then go home. About the time I was ready to retire from Classic Cinemas, I got an email from Brian Andreotti at the Music Box. The fella who played the organ after I left had quit, and he asked me if I could play for their first [Noir City Film Festival] with Eddie Muller. They asked if I could play for some or all of the programs, and then they wanted me to play for something in October, and then for the sing-along Sound of Music screenings, and for any and all of the Christmas sing-alongs, and said, “By the way, would you like to come back as house organist?” The timing was right. I sent them a note back that said yes, yes, yes, and yes. This was 2009.

For the first noir fest, one of the guests was Harry Belafonte. They had the Allen organ that they had since the mid-80s. It was on its last legs, so they bought another used Allen organ. My partner, Thom Day, bought the Kimball pipe organ console that you see at the theater now. It was built here in Chicago as a pipe organ the same year that the Music Box was built—1929. We bought the console in 2015, spent three and a half years restoring, refinishing, and respecifying it, and it now works with digital samples. We installed it in 2018, and because of the movie schedule, we only had a few days to get it going before the Christmas sing-alongs. It played its first notes on a Tuesday, and we had two sold-out sing-alongs on a Friday—no pressure, of course. [Laughs.]

Are there particular films you’ve learned to appreciate as a result of accompanying them?

Oh boy. I’ve accompanied so many, and after a while, they all blend together. I’m the organist for the International Buster Keaton Society, so I enjoy accompanying any Buster Keaton film, especially this one I just did last month in Ohio, which is College [1927]. The reason I like doing that is because I have the DVD and the 16-mm film and the Blu-ray of my mentor, John, accompanying that film. He accompanied it for Blackhawk back in the 1970s for a 16-mm film, then they came out with the VHS versions on Kino. They kept his score there, and also when they came out with the DVD and the Blu-ray. Up in my attic, I have John’s papers, and I have the themes that he wrote

out for that film, and I play those themes when I accompany it. Whenever he accompanied something for Blackhawk, he wouldn’t use published music because he was afraid of copyright, so everything was original.

So the Buster Keatons are my favorites to play. I also love the Janet Gaynor films, like 7th Heaven [1927] and Sunrise [1927], which is such a beautiful and powerful film. She had the perfect face for silent film. She’s the only person who could laugh and cry at the same time and you could understand why she was doing both at the same time. I thought she was an incredible actress.

At the Music Box, one of my favorite things to do is the Christmas sing-alongs. Over the years we’ve done more and more of them. Last year we did 30, and before COVID we did 34. Some of this depends on how the holiday falls in the calendar. When I first started at the Music Box, we only did a couple nights of Christmas sing-alongs, and over the years it grew and grew, and we’ve got more people coming each year.

I wrote a song for the sing-along with [emcee] Joe Savino. We both say that there’s so much positive energy during that run. When we get to the final two shows on Christmas Eve, we look at each other and say, “Are we done already?” At that point it feels like we’ve just hit our stride, and on some days we do four shows. People ask if we get exhausted, but we don’t because we get a lot of feedback and energy from the audience. That’s how people in vaudeville must’ve done it back in the old days when they did five shows a day. We call ourselves the last two vaudevillians in Chicago. [Laughs.]

The audience response is so good, and we have people coming up to us and saying that it’s become a family tradition for so many years. In 2019, I had three women on the same day tell me the exact same story, as if they read it from a script. During one of the movies, they were out in the lobby with their baby, and they said, “This is my daughter, she’s six months old. This is her first Christmas, and I’m starting this tradition with her because my mother started this tradition with me before I was a year old, and I’ve been here every year since. I’ve never missed a year since I was born. I hope my daughter keeps this tradition going.” So we’ve created something here that people have latched onto. And with all the goofiness going on in the country, I think people like it as an escape. v

m letters@chicagoreader.com

Should you also be an avid moviegoer, you may know that much has happened in the past week, both in Chicago and in the film industry at large.

First, some good news: According to Block Club, the New 400 Theaters in Rogers Park, which closed in August 2023, is set to reopen, though it’s unknown exactly when. The new lessee, Jordan Stancil, referred to in a post in the “Save the New 400 Theater” Facebook group, is “a former U.S. diplomat and university lecturer turned independent movie theater operator” who “has worked on the successful revitalization of historic theaters in Michigan, including the century-old Rialto Theater, Sanctuary Cinema in Alpena (re-opened in 2023) and the Big Rapids Theater in Big Rapids (slated to re-open in early 2026).” Solid bona fides, I’d say.

And some good news for the midwest moviegoing public, if not specifically Chicago, is that the Music Box Theatre is expanding its footprint to Minneapolis, where it acquired the historic Heights Theater. This is in addition to the Music Box’s third screen that’s slated to open in summer 2026.

But we can’t just have nice things. No. Where there’s good in this day and age, there must inevitably be bad. Over the weekend, it was announced that Netflix acquired Warner Bros. for $83 billion. (Sadly, I only have $82 billion, so any attempt I could make for a hostile takeover—which Paramount is now doing—would be for naught.) This is bad news for moviegoing. Netflix, though it has released many excellent films, is antithetical to the pastime; Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos is paying lip service to still releasing Warner Bros. films theatrically, as they admittedly do many of their own films, though theatrical windows will get shorter, allegedly in tandem with viewers’ desire to watch things at home rather than in a theater.

My mom was in town this past weekend, and I took her to see Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) at the Music Box as part of their an-

nual Music Box Christmas Sing-A-Long and Double Feature. I earnestly love It’s a Wonderful Life as more than a Christmas tradition. Capra is one of my favorite filmmakers for much the same reason Clint Eastwood is: I think he embodies the contradiction—or an entire body of them—that is America. And It’s a Wonderful Life is not an exception, despite its reputation as a “feel-good” holiday classic.

It’s a Wonderful Life is a tragedy, the lamentation of the so-called American dream, with a happy enough ending that, despite being the result of the triumph of capitalism over all things, exemplifies the importance of community. It’s sad because it’s sad: George Bailey did so much for others and, as a result, was never able to realize his dreams, even if he did get the “important” things in life, namely a devoted family and friends. And it’s happy because it’s happy: this idea that in the face of such insurmountable forces, we can in fact save us—that even if not perfect, things can still be good. Well, wonderful, actually. It really can be a wonderful life. In a way, movie theaters, especially the independents, are like the Bailey Bros. Building & Loan. On paper, the evil Potter was right: It was “a measly one-horse institution” that never stood to gain much for its owners, as they prioritized the lives and well-being of their customers. Nevertheless, Potter is threatened because the Baileys have and give something you can’t put a price on.

And what’s that? It’s people. Streaming is data and money (the lack of it needed for the overhead and the abundance of it that comes as a result of not having all that pesky tactility and warm-blooded interference—the real stu , so to speak, like buildings and people). Moviegoing is people. And you can’t put a price on that.

Until next time, moviegoers. —KAT SACHS v

The Moviegoer is the diary of a local film bu , collecting the best of what Chicago’s independent and underground film scene has to o er.

The incentives driving what’s le of music journalism say it makes economic sense to cover popular artists. But loving music isn’t about making economic sense.

By LEOR GALIL

n July, the Atlantic ran a story about a vanishing resource that was once commonplace in publications covering arts and culture: event listings. The story’s author, career musician Gabriel Kahane, had moved to New York City fresh out of college in 2003, and he focused his attention on the New Yorker, the New York Times, Time Out New York, and the Village Voice. His paean and obituary pointed out not only that listings showed him everything he could do each night but also that the pithy blurbs alongside the concert listings in Time Out gave him a crucial early boost as an emerging artist.

Kahane treated these critics’ picks as interchangeable with listings, which caused me some confusion. To me, critical writing about an upcoming concert is fundamentally di erent from a listing, which is typically just the basic details of the event, sorted by venue or date or some other principle. A listing doesn’t have opinions. A critic’s pick, by contrast, o ers a concise argument as to why a specific show matters.

The Reader still runs several such concert previews weekly, though they’re much longer than the old Time Out picks. (My preview of

Chance the Rapper’s headlining show in October, for example, was nearly 1,000 words.)

Kahane and I agree about many of the reasons concert previews are important—for one thing, they allow critics to use their knowledge and insight to advocate for artists their readers may never have heard of. Kahane mentions several famous musicians he found through listings before they became stars, which feels a little self-defeating. If it’s important to write about folks who aren’t household names, why focus on celebrities? I suppose he’s trying to explain the value of listings to boomer readers of the Atlantic

Kahane’s Atlantic piece also gets into the emergence of poptimism in the 2000s and connects it to the death of listings. Poptimism, loosely speaking, is a school of thought that encourages critics to bring intellectual rigor to pop music that’s been maligned (or ignored) by older generations of writers. (That said, two decades after the widespread adoption of the term, two critics might come up with three di erent definitions of it.)

Kahane argues that poptimist critics enriched the culture but couldn’t have imagined “the extent to which their goal would collide