04 Intro | Ludwig & Williamson Resiliency and joy

06 The Movement Architect | Caporale Carlos Fernandez brings together disparate factions in the fight for racial and economic justice

08 The Replicator | Montoro Janice Lim makes the fake stuff that helps Field Museum exhibits feel more real.

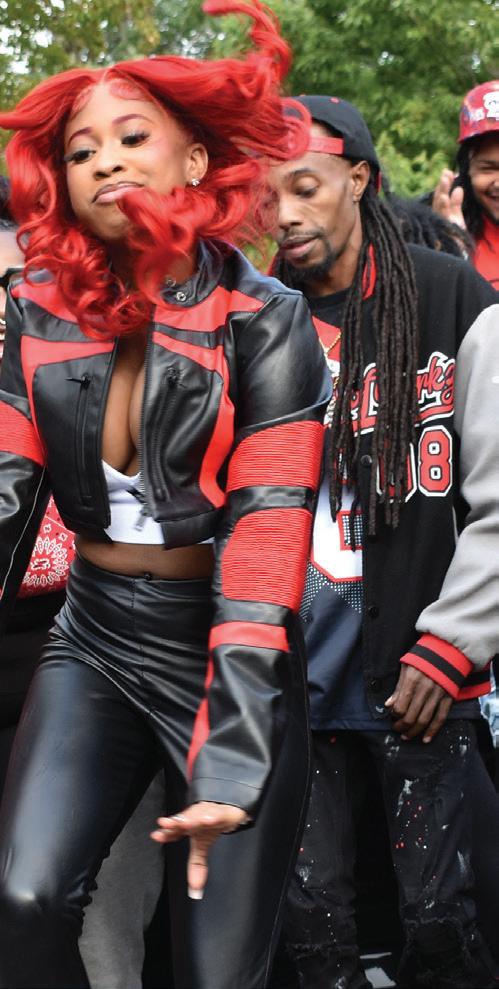

10 The Life of the Party | Triche Lil M.U. reps Chicago juke with the boisterous breakout hit “Top of Cars.”

12 The Tradition Keeper | McFadden Henry Carlson keeps Chicago’s Swedish heritage alive.

13 The Server | Sula Justin E. ArnettGraham uses his experience in the hospitality industry to advocate for workers.

14 The Striptease Savant | Renken Eva la Feva nurtures Chicago’s burlesque scene at the Newport Theater through “collaboration instead of competition.”

15 The Justice Championing Pastor–Professor | Brown Dr. Rev. Luther Young starts conversations and advocates for inclusivity of LGBTQ+ people in the Black church.

18 The Artistic Scientist | Ludwig Bozhi Tian brings a creative imagination to the discipline of bioelectronics.

20 The Tattoo Evangelist | Caporale Kyle Butler forges connection through creativity and touch.

22 The full-spectrum doula | Ludwig Kate Palmer provides compassionate, accessible care in a post-Roe world.

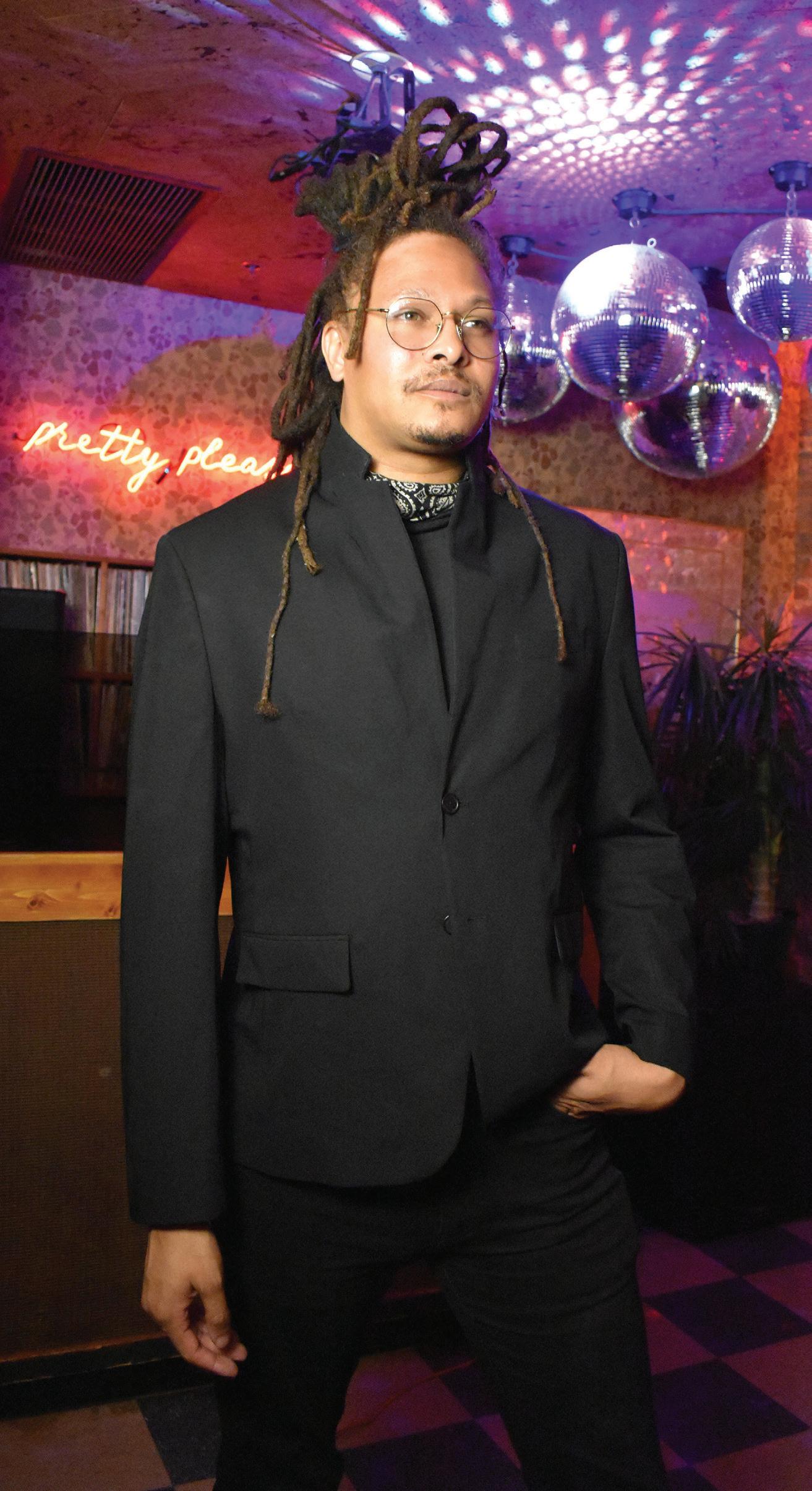

24 The Musical Fabulist | Reid Dominick Alesia brings fantasy and music to the stage.

26 The Community Builder | Mulcahy Nat Palmer centers people in her abolitionist organizing.

27 The Baseball Heir | Galil Night Train Veeck wants to keep baseball affordable and fun.

30 The Arts Visionary | Cardoza Tempestt Hazel helps preserve the cultural stories of the midwest.

32 Shows of Note Previews of concerts including Natural Information Society, Pamela Z, and Algernon Cadwallader

34 Gossip Wolf | Galil Arthur Banks of Jugrnaut passes away, rapper OkDeazy headlines a monster show at Subterranean, and more.

INTERIM PUBLISHER ROB CROCKER

CHIEF OF STAFF ELLEN KAULIG

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR

SAVANNAH RAY HUGUELEY

PRODUCTION MANAGER AND STAFF

PHOTOGRAPHER KIRK WILLIAMSON

SENIOR GRAPHIC DESIGNER AMBER HUFF

GRAPHIC DESIGNER AND PHOTO RESEARCHER SHIRA

FRIEDMAN-PARKS

THEATER AND DANCE EDITOR KERRY REID

MUSIC EDITOR PHILIP MONTORO

CULTURE EDITOR: FILM, MEDIA, FOOD AND DRINK TARYN MCFADDEN

CULTURE EDITOR: ART, ARCHITECTURE, BOOKS KERRY CARDOZA

NEWS EDITOR SHAWN MULCAHY

PROJECTS EDITOR JAMIE LUDWIG

DIGITAL EDITOR TYRA NICOLE TRICHE

SENIOR WRITERS LEOR GALIL, MIKE SULA

FEATURES WRITER KATIE PROUT

SOCIAL JUSTICE REPORTER DEVYN-MARSHALL BROWN (DMB)

STAFF WRITER MICCO CAPORALE

SOCIAL MEDIA ENGAGEMENT

ASSOCIATE CHARLI RENKEN

VICE PRESIDENT OF PEOPLE AND CULTURE ALIA GRAHAM

DEVELOPMENT MANAGER JOEY MANDEVILLE

DATA ASSOCIATE TATIANA PEREZ

MARKETING MANAGER MAJA STACHNIK

MARKETING ASSOCIATE MICHAEL THOMPSON

SALES REPRESENTATIVE WILL ROGERS

SALES REPRESENTATIVE KELLY BRAUN

SALES REPRESENTATIVE VANESSA FLEMING

ADVERTISING

ADS@CHICAGOREADER.COM, 312-392-2970

CREATE A CLASSIFIED AD LISTING AT CLASSIFIEDS.CHICAGOREADER.COM

DISTRIBUTION CONCERNS

DISTRIBUTIONISSUES@CHICAGOREADER.COM

READER INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNITY JOURNALISM, INC.

CHAIRPERSON EILEEN RHODES

TREASURER TIMO MARTINEZ

SECRETARY TORRENCE GARDNER

DIRECTORS MONIQUE BRINKMAN-HILL, JULIETTE BUFORD, DANIEL DEVER, MATT DOUBLEDAY, JAKE MIKVA, ROBERT REITER, MARILYNN RUBIO, CHRISTINA CRAWFORD STEED

READER (ISSN 1096-6919) IS PUBLISHED WEEKLY

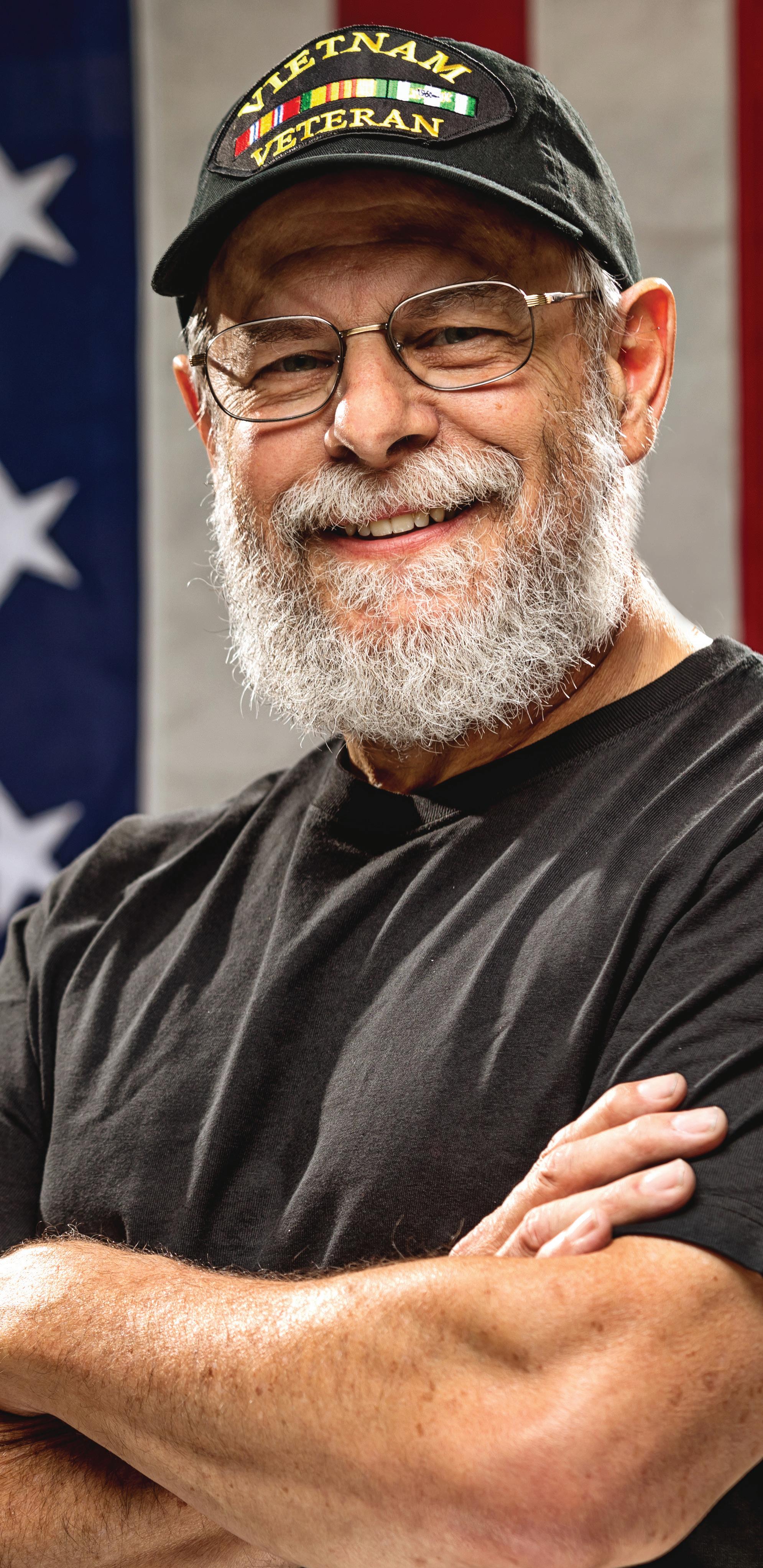

As the photographer for all 14 of this year’s honorees, I am in the special position of being the only Reader staffer to have actually met them all. The process has been fulfilling, and each subject touched me with a moment of joy.

ing. I know now there is a welcoming space in the hearts of man, and that’s a great comfort.

In July, when we started planning this year’s People Issue, we didn’t know if the would still be around for its publication. We were six months into a financial crisis, and amid steep staff and budget cuts, we were operating on a precarious basis—sending each issue to print without knowing whether it would be our last. Still, the prospect of running our annual collection of as-told-to interviews with everyday Chicagoans felt positive: Whatever life brings, we can count on the people in our city to have fascinating stories and perspectives.

As the issue began to take shape, the Reader was acquired by media company Noisy Creek. Finally, a er eight long months, we could breathe a sigh of relief knowing the paper would carry on with its integrity and editorial independence intact.

On September 8, just two weeks a er the acquisition was announced, the Department of Homeland Security launched Operation Midway Blitz, which has been sending masked ICE agents into Chicago and its surrounding suburbs, aggressively targeting individuals and disrupting communities under the stated purpose of arresting “criminal illegal aliens.” In response, ordinary Chicagoans have risen to the occasion and shown what makes the Windy City such a beautiful place.

So, this People Issue is dedicated to you: the people of Chicago. For having courage in this moment, for organizing and building community, and for standing up for family, friends, neighbors, and people you’ve never met. For starting tough but necessary conversations, and learning from those whose experiences and outlooks differ from your own. For engaging in peaceful resistance and for spreading joy through the darkness—whether through distributing whistle kits, supporting immigrant-owned businesses, or attending solidarity events as intimate as a basement benefit concert or as large as the 250,000-person-strong “No Kings Day” march downtown. And importantly, for bearing wit-

ness and telling the world about the injustices happening here. Not because it’s easy, but—as the growing number of people getting involved suggests—because right and wrong matter much more than party politics or superficial divisions. A similar spirit of purpose, hard work, and compassion pervades the 2025 People Issue. These 14 subjects hail from across the city and span more than seven decades in age. Despite their different histories, professions, and points of view, they’re united by a desire to uplift others and make society kinder and better, through actions such as advocating for hospitality workers like Justin E. Arnett-Graham (p. 13), supporting arts and writing projects from underrepresented groups like Tempestt Hazel (p. 30), or dropping hot dogs via helicopter over throngs of hungry baseball fans like Night Train Veeck (p. 27). Speaking about the bioelectronics research group he leads at the University of Chicago, chemistry professor Bozhi Tian (p. 18) says, “We want to design materials that benefit humanity. We want to do good things instead of going to the other side.”

Whether in these profiles or out in our neighborhoods, the takeaway is that anyone can play a part in making Chicago great. And our collective efforts can be a source of hope and pride while directly contradicting false narratives about the city and its inhabitants. “We are so much more than what people say we are,” says rising rapper Lil M.U. (p. 10).

As 2025 ends and a new year begins, there’s no way of knowing what’s coming down the pipeline, but a couple things are certain: The Reader is still standing, and as long as Chicagoans continue to extend those “big shoulders” to one another, the city will remain standing, too. As community organizer Nat Palmer (p. 26) says, “The people are winning, and we will always win.” v

—Jamie Ludwig, projects editor m jludwig@chicagoreader.com

Carlos Fernandez: Carlos toils on the front lines of ICE abduction efforts. It was reassuring to talk with someone who is immersed in the trauma and still able to keep a level head. His determination and positive worldview should serve as a field guide to us all.

Janice Lim: I deeply admire her focus and attention to detail in her fabrications. I feel very much the same way when I can immerse myself in a project from concept to reality—like my months of work on this issue.

Lil M.U.: Fans who heeded the social-media call to appear in her music video took turns showing the fuck out, each in some red item of apparel. Through it all, she remained humble and grounded.

Henry Carlson: As a gatherer of family stories, it was exhilarating to spend a morning with a nonagenarian who has lived in the same house since the Korean War. We sat and talked extensively, and I took a special photo of him so he could send it to his grandson.

Justin E. Arnett-Graham: Hospitality is in this dude’s blood. He joyfully went out of his way to offer me water, food, and genuine smiles at all times. It’s plain to see why he’s chosen the path he is on. Or did it choose him?

Eva la Feva: Eva was the first person photographed for this issue, and she kicked off the project on a high note. Drama! Costume! Sassssss! And she offered me the use of the Newport Theater’s photography studio for future shoots—an offer I plan to take her up on.

Dr. Rev. Luther Young: I fled the church years ago, owing to mainstream christianity’s persecution of LGBTQ+ people. Seeing his queer-affirming congregation was redeem-

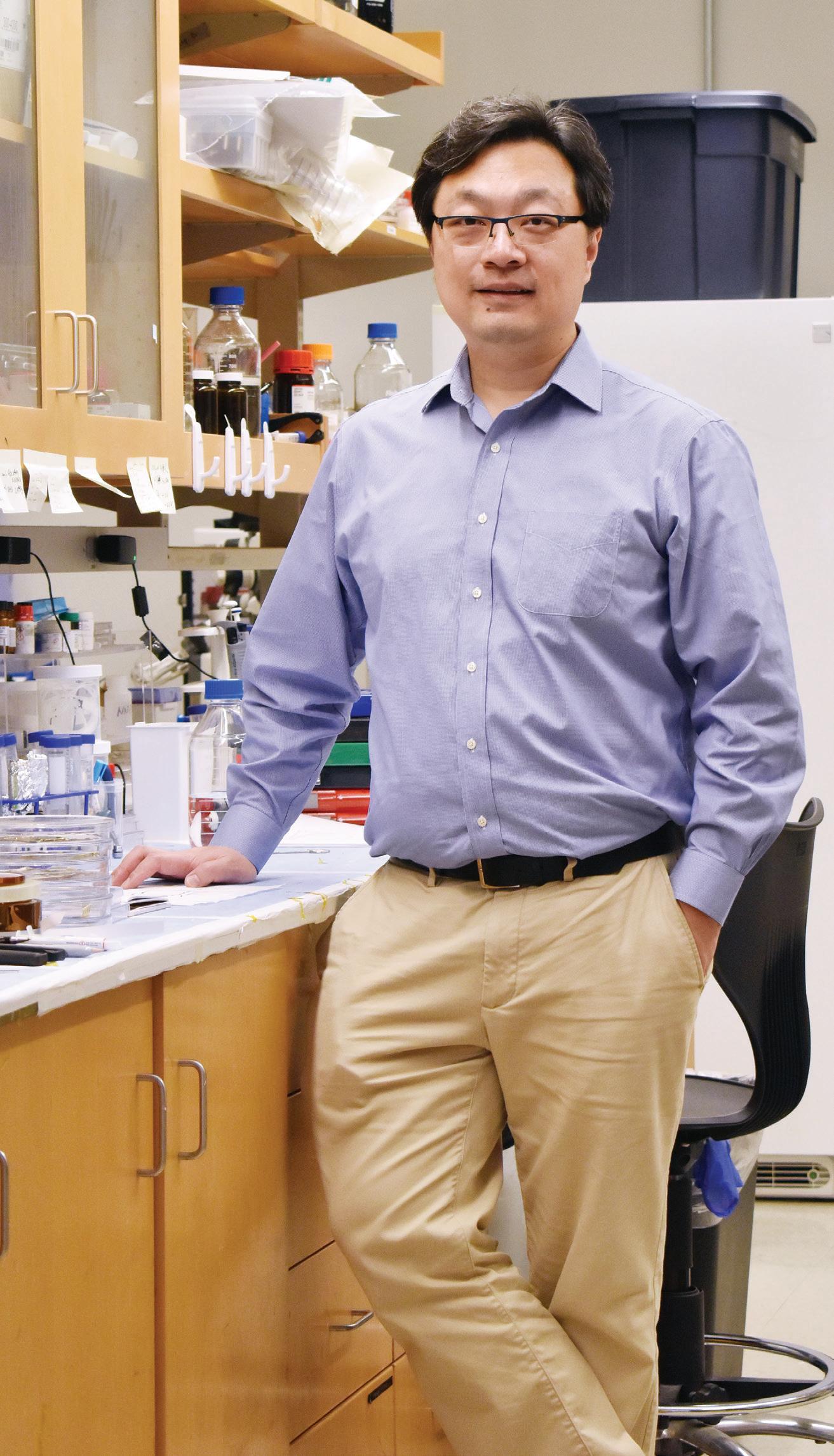

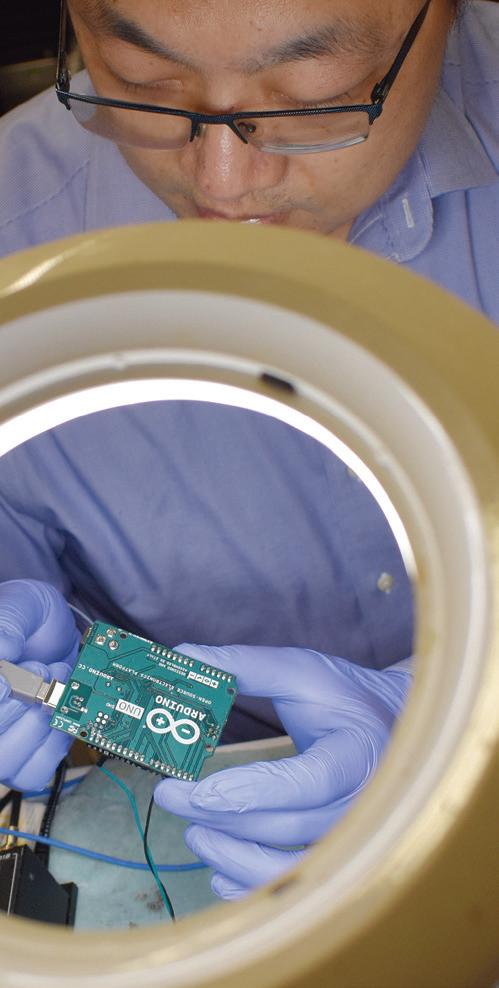

Bozhi Tian: Bozhi’s arts background became clear during the shooting process. He suggested interesting angles and gave me the freedom to crawl behind different tables and other science lab furniture. It’s not o en that a subject is also the perfect photographer’s assistant!

Kyle Butler: He was quite friendly with his client, on whom he had worked in the past, and he discussed travelling to all corners on tattoo adventures. It’s nice to see someone so young who has clearly found their place in the world.

Kate Palmer: I wish more people would devote themselves to helping everyday folks navigate life and liberty in a climate that wants to curtail both.

Dominick Alesia: I was thrilled to discover that Dominick, like me, is Black and Sicilian. I have an uncle Dominick, who was named a er my great-grandfather Dominick. My time with Mr. Alesia felt like family.

Nat Palmer: I felt privileged to be welcomed into Nat’s place of peace, Columbus Park. She showed me all the cool nooks and shaded corners, and we discussed the ducks in the pond with a Zen level of disconnection.

Night Train Veeck: We were always a White Sox family, and the legend of his grandfather Bill looms large. Any guy that endeavors to break the record for the most hot dogs dropped from a helicopter is a gem. And spending a beautiful day on the field with a delightful professional is something few get to experience.

Tempestt Hazel: We were just two goo alls being goofy in the sun. She projects a muchappreciated sense of warmth and quirk. We discussed our unique names and how we have accepted the constant references they elicit: “Captain” for me and “Bledsoe” for her. v

—Kirk Williamson, sta photographer m kwilliamson@chicagoreader.com

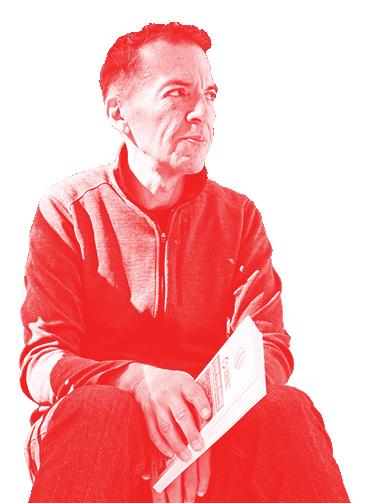

Carlos Fernandez has seen Chicago through many seasons of change. The 52-year-old organizer was raised in Pilsen as the oldest of four boys and the son of immigrants. He brings a firstborn’s assumption of responsibility and a Catholic’s sense of duty into all areas of his life. In 1987, after his family moved to Chicago Lawn, Hernandez started a slow political awakening that has continued to guide his life. The change forced him to commute to school daily across large swathes of the city. Navigating so many different kinds of people and neighborhoods made him begin to consider some of Chicago’s vast political and social problems.

Fernandez headed to the east coast for

college, spending a year each at Brown University and Hampshire College before dropping out. He’d become so involved in punk and activism he lost interest in his studies, though he eventually returned to school and graduated later in life. By the early 2000s, he decided to pursue a career in community organizing, which he’s continued doing for two decades. He’s worked on everything from union campaigns to environmental justice issues— always in a more grassroots capacity. Now based in West Elsdon, he’s the executive director of Grassroots Collaborative, a coalition of eight local groups working to unite disparate factions in fighting for livable wages, affordable housing, strong union jobs, and more.

Interview by MICCO CAPORALE

Photos by Kirk Williamson

My parents ran an auto junkyard and repair shop in Pilsen. I was brought up pretty Catholic. My parents—especially my mom— were very active in the church, and there was a strong sense of service. My mom was involved in a Catholic Worker youth organization that helped people form unions, fight for fair pay, and access food and other needs, like legal aid. My uncle became a deacon and volunteered in the United Farm Workers campaigns in the 70s. That wasn’t political to me; it’s just how I was raised.

Growing up, I didn’t realize how big Chicago is. I had a sense of its diversity, but I grew up in neighborhoods that were majority Mexican. Weekends were spent with cousins and summers in Mexico. I had this sort of insular universe until I was in high school and traveling around more on the bus and train. We moved from Pilsen to Chicago Lawn when I started at the De La Salle Institute, down the street from the Robert Taylor Homes. I took the bus almost every day from 61st and California to 35th and California, and then another bus down 35th to Michigan Avenue.

[In 1987], freshman year, I remember being in class when the news broke of Mayor [Harold] Washington’s death. It was a mixed class of Black, Latino, and white [students]. I didn’t understand why some students were cheering while others were extremely serious and quiet. It was clear that a lot of people, especially white people, but some Mexican and Latino people, had racist views towards the mayor because they had racist views towards Black people in Chicago. That moment taught me that racism doesn’t just exist on the fringes. It was right in that classroom, among 20 or 30 kids.

My social networks in high school and college made my mental map of Chicago bigger and more complicated, not just around race, [though] that’s number one on my sense of divisions in the city now. I went to the east coast for college for a couple of years. Like a lot of Mexican families at the time, I was the first on either side of my family to go to college.

I wasn’t focusing on much at school—I was more interested in going to concerts, lectures, bookstores. I’d pile in the car with friends and go to New York to see a show, or Connecticut, or Boston. If we could go to a protest or wheatpasting, we’d do that, too. I had an interest in literature and film, especially Latin American film, and that’s actually what I got my degree in about ten years later, at Columbia College: film studies. Art felt like a way to map the world, and I was doing what felt right and exciting. A er I dropped out of Hampshire, I came back to Chicago and worked in the family business until I decided to finish my degree around ’99 or 2000. I was still involved in the punk scene, but I became more of an activist. I had friends who started a punk band that sang in Spanish: Los Crudos. [Vocalist] Martin Sorrondeguy and I knew each other before they formed [in 1991]. He introduced me, not just to political punk bands, but also to Latin American folk music that was political, [including] Violeta Parra.

While I was finishing my bachelor’s, I was involved in small activist groups. There was a place called the Autonomous Zone. It was a bookstore (we called it an infoshop) that had all sorts of educational events, and my friends and I were involved. I was doing lots of things, but I felt really dissatisfied going to so many protests [where] the people there didn’t look like me or reflect the neighborhoods I grew up in. I responded to an ad for an organizer at the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. I worked there for a year, then had a couple more organizing jobs. It didn’t feel like I knew what I was doing until maybe ten years later.

Organizing is complicated. You’re building relationships with people that you don’t know and that you may not have a lot in common with. You’re asking them to take risks—to do things that they

“Organizing is as difficult and messy as it is valuable.”

might not want to do but that you believe they will see are in their interests. Organizing is as difficult and messy as it is valuable

One mentor that really helped me was James Thindwa. He was pretty active in the anti-apartheid movement of the U.S. and hired me in 2004-ish. He wasn’t of any particular part of the le , but he understood organizers had an important role in the le broadly. However underpaid and underappreciated or small our roles were, he helped me see we were catalysts for big things.

I became involved with Chicago Grassroots Collaborative because James and I were working at Chicago Jobs with Justice, which is a similar labor and community coalition. [Around 2006], Grassroots Collaborative, Jobs with Justice, and a bunch of other groups got involved in the big-box living wage ordinance. When Walmart was trying to open its first stores in Chicago, union and community groups wanted to make sure that we put roadblocks in front of them. They either had to pay a living wage or not come into Chicago. [Editor’s note: The work of Grassroots Collective and others led the Chicago City Council to pass an ordinance requiring large retailers to pay a living wage in July 2006. Seven weeks later, Mayor Richard M. Daley vetoed the bill—the only veto of his career.]

Just before the pandemic, I was living on

the east coast and working with the American Federation of Teachers. I le my job and moved back in 2020 to be closer to my parents.

At the time, [Grassroots Collaborative’s previous director] Amisha Patel was looking for somebody with labor union experience to do some work with what we call bargaining for the common good, which is something the Chicago Teachers Union pioneered. That was my first role at the Collaborative, which started in 2021, and I became the executive director in 2023.

I feel grounded in Martin Luther King’s quote [adapted from an 1853 sermon by abolitionist minister Theodore Parker]: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” I’m worried that young people take the options that are given to them for making a difference in the world without realizing that those options are structured for them by a world that wasn’t designed for them. We live in a society that answers problems with violence or money or hierarchy or domination and prisons. In each place and time, people have to use the options available while also realizing that they can create new ones. That means finding the approaches, tools, organizations, institutions, and relationships that actually create something more like what they want. I feel like that’s what the arc of the moral universe is.

The return of violence, both on a small scale and also the genocide in Gaza—things don’t just keep getting better, right? But I do believe that you can make some things better, and I think Chicago has gotten better in many ways. It’s become more tolerant and afforded more space for different identities, like queer and gender nonconforming people. I see the multiracial character of young organizers, especially activists motivated by Palestine and George Floyd. It gives me hope.

I think a lesson for anybody, anywhere, is that, even when there are setbacks, you can always see new ways of organizing the world. v

m mcaporale@chicagoreader.com

Janice Lim, 45, works at the Field Museum as head of the replication shop in the exhibitions department. She’d already studied art conservation and worked in furniture restoration by the time she learned what a replication shop was and that the Field had one. She thought the shop sounded so cool—and like such a perfect fit for her skills—that she wrote to the museum looking for a job, even offering to work for free.

The Field took her up on that offer, and in 2014 Lim began volunteering. She left after about a year, when a paying job didn’t open up, but in 2016 she was hired as a mount maker in the museum’s metal shop. Soon she was spending months each year in the replication shop instead, and in September 2022,

she took over as its head. Lim also helped lead the organizing campaign that won Field Museum workers a union with the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees in March 2023. She serves as a steward for her department.

Lim also plays drums in Chicago’s DIY music scene. Mostly self-taught, she learned to play at 19 from beloved weirdo-rock fixture Eorl Scholl, who walked into the record store where she worked and recruited her for a band that lasted one show. After that, she drummed in Civilized Man and then Gula Gila. She currently plays with former Gula Gila bandmate Jill Flanagan (previously of Forced Into Femininity) in the four-piece Shri , who debuted in June 2024.

Interview by PHILIP MONTORO

Photos by Kirk Williamson

Imake the fake stuff for the museum, and especially the temporary exhibits. When there’s an object that’s too delicate to be on display because of light, or it’s just too fragile to be put on a mount and displayed, or if we don’t even have the object or can’t get it on loan, they’ll have me make it.

I make the smaller fake stuff. So not the ginormous dinosaurs erected in the main hall, but the smaller stuff that can be a touchable for the audience—to help make it a tactile experience or help visually impaired folks.

O en we’ll have a show, and then we would want to have it tour around the country or to Canada. Sometimes there will be a wet specimen jar, which is a dead creature floating in a jar of alcohol, and o en they don’t want to travel those—it’s too delicate or whatnot. And they want me to make a replication of the creature and how it lived—instead of a snake coiled up in a jar, it would be a snake lunging at you.

We’re working with 3D prints more these days. If it’s not the correct species that they need for the show, that means I might chop off a tail, sculpt a new tail, correct the ears, and paint the body, either airbrush or by hand, with the correct pattern and colors

Sometimes to save me time, they might order a model online, but o en those models may leach things that might hurt organic objects in the case, like coral or bird skin.

We have a really amazing conservation lab. So they do this thing called an Oddy test: A conservator will ask us for samples of new materials we may use. There’s a little oven that he sets these samples in with little metal coupons made of copper, silver, and lead. Then, to speed up the process, he turns on the oven to a really low temperature and lets it run for a month. And once he pulls out the samples, he looks at the coupons, the little cut pieces of metal, and then he’ll see how they degraded over that month. And then he decides whether that material is safe enough to be within a case—it could be a paint sample, a piece of resin, a type of caulk. There are different ways to light an object that’s

very fragile. We have a great lighting team that will set a timer and measure the light and heat to make sure that it’s at a safe setting. But if it’s like, “No, this cannot even be out,” even in adjacent light or anything like that, then they would have me make something.

For a show called “Wild Color,” there were a few wet specimens, and one of them was a jar of little anglerfish. I think it was five the size of golf balls in one little jar. And they were black seadevil anglerfish. They didn’t want it to travel. So the designer took the opportunity to be like, “Hey, can you just make one living, bigger anglerfish? I would love for it to be, like, four inches by four inches.”

We have a really great fish collection, and we found one jarred anglerfish of that kind in the back. We got to pull it out and then measure it. I was given the iconic book of anglerfish by this man called Ted Pietsch, and I used that as a reference. The anglerfish is a deep-sea fish, and when you pull something up from that deep it o en kind of becomes zombified. Its skin starts peeling—like, dripping off. Even the anglerfish I had was pretty gnarly looking. So I was drawing from all different kinds of sources to make up this new big girl.

I used resin as the main material for the model, but it was really tricky. There was a lot of problem-solving with this show. It was like a color-coded show. Each case was a mixed case—the anglerfish was in the black-andwhite room, so the case it went in was with, like, maybe the hide of a skunk, a black-and-white bird, and then maybe some organic objects. So I had to use Oddy-approved materials.

Fortunately, though, from my experience in the mount shop, I knew which kind of wire, which kind of paint were already Oddy-approved. So I was able to use wire in the tail that I made. I first sculpt-

“I make the fake stuff for the museum.”

ed it with clay and then made a mold out of silicone and poured resin into it. I popped out two, but then those twins started to divert, because one of them was just a test. This was all kind of new to me—I didn’t know what would work. It was very experimental in that sense of, like, how to make a fin. I ended up using Japanese paper and this archival adhesive called [Paraloid] B-72.

I love miniatures, and they asked me to make a diorama of this Hungarian tell as part of a show called “First Kings of Europe.” It’s basically a large mound or hill. A tell is, like, when you have a bunch of civilizations buried on top of each other—it becomes a hill. And so it was this tell with these longhouses on top, and I made a water feature because it was surrounded by a river system. Through excavation and stuff, they pretty much knew where these longhouses existed. They gave me a sketch. Curators work with developers; developers work with designers; and then they work with me, as well as the woodshop and the mount shop. The developer gave me a really hearty info packet, like a dossier, and a video animation that someone made of the tell. So I

took stills of that. If they’re like, “Oh, here are longhouses, here’s an example,” they’ll give me enough, but I want to see something at a different angle or how it was woven. So I always do my own side research, which I totally enjoy. We revamped “Native Truths,” which reopened in May 2022, because we’ve been trying to decolonize the museum. We’re working with living artists, folks, tribes. The new one that’s rotating in is the Coast Salish, and that’s basically the Pacific Northwest, British Columbia area. And so I’m making a diorama of—there used to be this type of dog that’s now extinct called the woolly dog. They didn’t have sheep, so they would breed these dogs and shear their fur and weave really beautiful blankets, and sometimes mix in a little bit of goat hair, maybe some earth materials.

The diorama is a little island, and I’m supposed to make a little canoe where two women just rolled up and are about to feed the dogs salmon. They had the dogs on a diet of salmon, to make the coats really nice.

I absolutely love working for the museum, because of the ongoing educational aspect— we’re always learning, we’re always teaching the public, we’re holding and preserving things from the past for future generations.

People are there to learn, see something new, be blown away by something. We have a really great museum, and it’s amazing what, when we come together, we can show the public.

Isn’t that the whole point of the museum, to show the truth and what had existed? What exists and what existed before? I think if you show something that’s off—I don’t know, it’s just lazy. You’re just missing the point of a museum if you don’t take that seriously. v

m pmontoro@chicagoreader.com

Make time to learn something new with music and dance classes at Old Town School! We offer flexible schedules for all skill levels both in-person and online.

If you left your home at all this summer, you probably heard somebody blasting “on top of cars, on top of cars, shakin’ butt on top of cars” as they sped past you down the street. And if you were really lit, you might’ve been one of the folks shakin’ butt on top of cars. Twentyfive-year-old rapper, DJ, dancer, and choreo grapher Quimaya Sewell, aka Lil M.U. or Maya Unique, released “Top of Cars” in April, and much to her surprise, she had the juke song of the summer less than a year into her music career. She wasn’t necessarily even planning to go into music, but she’ll take juke as far as she can, with hopes to shed a positive light on Chicago’s culture. As summer began to wind down, Lil M.U. and I caught up by phone as she was planning the video shoot for “Top of Cars.” (The video came out on October 10.) She reflected on her roots as a dancer, the impact of juke music, and the whirlwind year she’s had.

Interview by TYRA NICOLE TRICHE

by Kirk Williamson

Iwas born and raised in Englewood. As a kid, I was very outgoing, kind of like I am now but probably a little bit bolder with everything. I was always dancing. I grew up dancing since I was three years old. I recently, like two years ago, got into DJing, and I just started rapping. I dabbled in making a song when I was younger, because my dad had a studio and he’s a DJ—he produced beats and stuff like that. So I dabbled in that when I was younger, but I never [thought] I’d have a music career growing up.

But now, you know, it turned into something. But growing up, I really was always dancing. You couldn’t tell me nothing! I’d be breaking out and dancing. I’d dance at the 63rd Street Beach by the drums and doing performances.

Dance has meant everything to me. It’s my first love. It was my only love, but I feel like music helped me expand that. But dance has always been an outlet for me: an expression when I can’t express myself, when I’m sad, when I’m happy, when I’m feeling lonely, emotional, anything. Dance has always been an outlet, and dance also is a way to bring everybody together. So I just feel like dance is really healing, and it’s always been healing for not just me but everybody.

I grew up dancing to juke music—it’s always been instilled in me. Always grew up to [Traxman’s] “Get Down Lil’ Momma,” [DJ Spinn’s] “Bounce N Break Yo Back,” all those things. When those came on, I was definitely bobbing my back down. I got videos to prove it! Juke music has always been a part of my life. I think that’s why it’s so heavy with me as far as how I represent Chicago.

[Transitioning from dance to DJing] hasn’t been hard, because it’s all connected—everything is connected through music. Dancing and DJing, it kind of goes hand in hand. When I DJ, I dance at the events. I know what beats or how things blend based on my ear and my counts also, so it all goes hand in hand. When I’m blending stuff, you gotta count it off just as well as you do when you dance. Then they go into my music, because I play my music at the DJ gigs, so it’s all tied to each other.

I’m very impulsive, so if I feel it, I’m gonna do it. That’s just me. The person that allowed me to get in the studio was someone named YdotGdot. He was the first person to take a chance and be like, “OK, you can use my studio.” You know, studios ain’t cheap. He was the first person like, “Yeah, you can use my studio and we can work together.” I’m like, OK, cool. So that was the first person that helped me. From there, my very first song kind of got some buzz, which got my name out there a little bit. Then I dropped my first-ever EP, which included my first song. That kind of took off—that’s going global now.

I started making music in October 2024, and the Handful EP came out in April 2025. I started it at the end of February, I believe, and I finished it at the end of March. I kind of used songs that were already out, that I’d put out on YouTube, and put them on the EP instead of just having them as singles. So, like, “M.U. Stomp,” my songs “Birthday” and “What?!,” those were songs that were singles, and I just put them on the EP.

I expected it to blow up, but not like this. I think this exceeded my expectations, honestly. I wasn’t expecting it to blow up in a short amount of time. Like, I knew it was going to do numbers, but I didn’t know it was going to be, like—right now, I think we passed seven million streams. I didn’t think it was gonna go this far. [Editor’s note: “Top of Cars” had topped 11 million streams on Spotify alone by publication time.]

[Going viral] has its ups and downs. Definitely the good, though, outweigh the bad. I would definitely say that. It’s helping me to see myself and grow as a person, too, and figure out if I really want to be in the music industry. Because it wasn’t my plan, but it’s giving me a glimpse of what it would be if I continue to pursue it, which I am. It’s giving me

“I grew up dancing to juke music— it’s always been instilled in me.”

a glimpse of how I have to move, how I would have to grow, and how I would have to not take everything so personal. But overall, I’ve definitely gotten support from the city, so I love

I mean, it’s kind of crazy. I don’t think I grasp it, because I don’t live in the moment. I kind of keep going and going and going. So it’s crazy to see it in real time, people actually [dancing and listening to my music]. Like, “Oh, that’s crazy, that I really did that.” You know how you don’t expect things to go certain ways? But God has a plan. It got past me, beyond what I imagined it to be. I always imagined myself having this impact as a dancer, not as a [music] artist. So that’s kind of different. It especially feels great to know that I have not only the youth, but I have everyone of different ages, of different eras. And people giving me my fl owers in the footwork community, people giving me my fl owers, like, in

every era. I have the whole city on my back, supporting me, so I really feel great about that.

Mello Buckzz kind of started it, as far as pushing the juke genre out with her song “Move.” And I’m continuing that legacy, to push us to continue [striving] for people to really understand juke and really understand us far beyond drill, to really know what Chicago culture is and footwork. Because, you know, everybody tries to do it, but nobody really knows the history behind it. So [I’m] pushing that narrative and pushing for people to see [Chicagoans] in a positive light, and pushing us to make people dance again.

I’m trying to mix juke with almost everything. I’m trying to put Chicago on the map in so many ways, where it’s like, you can’t deny juke, you can’t deny Chicago. When you hear me, you hear Chicago. When you see me, you see Chicago. Because I definitely am going to rep Chicago wherever I go, and that was before I even started making music. So I’m definitely just putting the city on in as many ways as I can, and in a positive light.

I got a lot planned to keep pushing this Chicago narrative, [for people to] see beyond what the news [portrays] us as and what a lot of people push us as on social media. We are so much more than what people say we are. We are so talented in the city, and I just want people to see us as that and see us as much more than just where we come from. v

m ttriche@chicagoreader.com

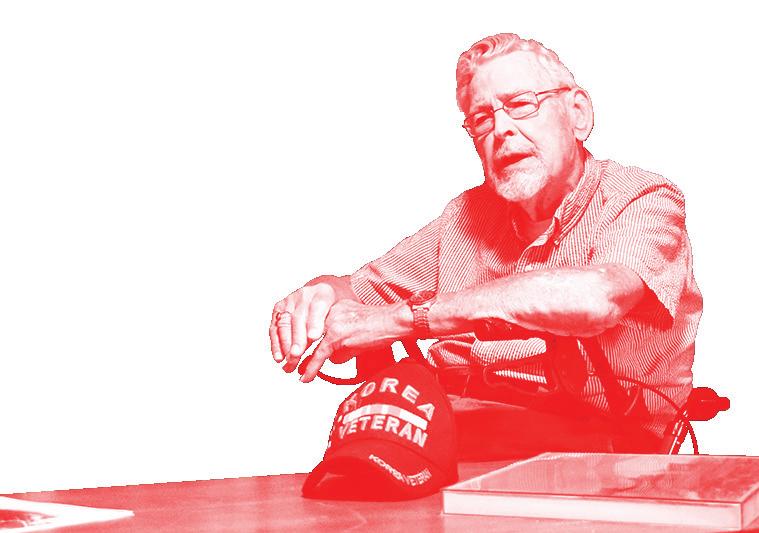

Henry Carlson, 96, was born in Oak Park to Swedish immigrants. He was raised on Chicago’s far northwest side, graduated from Lane Tech College Prep High School in 1946, and studied civil engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Just as he began to put his degree to work, he was dra ed into the U.S. Navy and spent four years working on a fl eet tanker off the southern coast of Japan during the Korean war. He married young and had a son and a daughter. Carlson worked for the City of Chicago from 1953 until 1990. Sixteen of those years were dedicated to the construction of the water purification plant near Navy Pier, a project of which he remains proud.

Carlson, a vocalist and accordionist, occasionally visited Sweden—including a formative first trip at age 17—and

maintains a connection to Swedish culture and community in Chicagoland. Always on the hunt for Swedish relics, he was a shopper at local estate sales and worked as a hobbyist reseller, though his mobility limits that nowadays. Still, for a nonagenarian, Carlson stays busy: He enjoys raising dahlias and birdwatching in his Park Ridge home garden; meeting with his Swedish lodge club; spending time with his daughter and grandchildren; playing bingo with the ladies at a local senior center; driving independently (he passes his test every year); and celebrating Swedish holidays and traditions, such as the Scandinavian Day Festival in Elgin’s Vasa Park, Midsommarfest in Rockford, and events at Andersonville’s Swedish American Museum.

Interview by TARYN MCFADDEN

Photos by Kirk Williamson

My background, as I say, is Swedish.

Both my parents and grandparents immigrated from Sweden. With my cousins, we had a Swedish musical group. I graduated from high school in ’46. It was in the late 40s that we played all these clubs along Clark [Street]. We’d play every Saturday for the Swedish dances here. These Swedish lodges would have their meetings, and then they’d have a little coffee, but then we’d play for the dance so they could remember back home—they could dance the schottis or the hambo.

I met a lot of Swedish people when we played for dances. I met my wife, in fact, at a Swedish dance. My wife’s name was Dorothy. She was from Michigan. Her parents both had immigrated, and they had a lodge, and my father-in-law played accordion, like I did. He played the button accordion, whereas I played the piano accordion. So it was a rather interesting group that I married into.

The fi rst time I went to Sweden, I was 17, with the Swedish male chorus from North Park College. Everything we sang was in Swedish. We sang in the Swedish churches, and we were on tour for an entire month. We went from the southern part of Sweden, from Malmö, all the way up to Luleå in the north part of Sweden.

All the other men were my father’s age—45, 50— and there were three or four of us young guys at that time. We did two concerts a day, for lunch and for dinner. And [at] the dinners, the participants or church people would stand up, and our names would be called, and those are the people we would go home with at night.

They rode a lot of horse[s] and buggies in those days. And no electricity, of course—everything was candles in the house when I got there. You wonder about fires, but everybody had candles going, and of course, the [toilets] were out in back. Some of them did have water inside. Then we’d have breakfast with them in the morning, and we’d get in the horse and buggy and head back to church till departure on the bus.

At that time, you know, I probably didn’t appreciate being a young kid, shall we say—what went on

there and how nice the people were to us in the churches. And most of those people that we went home with could not understand any English and our broken Swedish, but we got along with our hands—like anything else, you point. We knew what we were saying. But they were so kind.

When the tour was completed, I went to visit my grandparents out on the farm—my father’s parents and all my aunts and uncles at that time. I spent over three and a half months in Sweden with them. It was actually very rustic out on the farm. They lived in [Norrbo, near] Grangärde—it’s a small town probably about [40] miles from Falun, which is a big copper mine town. It’s the middle part of Sweden, and the name of the province is Dalarna. This was more where my father came from. My mother, she came from the southern part of Sweden, where her parents immigrated from. And spending three months out on a farm with 17 cousins, I got to pick up the language much sooner than I had anticipated, because they always said, “No English. You must learn to speak Swedish.”

I would relish to go back to Sweden. In fact, [my daughter just went] back to Sweden for ten days. I wish I could go with, but I don’t want to be a burden on anybody. It’s too difficult.

I think it’s been well over ten years [since] I went back. But at that time, I was a little more mobile. The first time I went back, I had 17 first cousins. And I just lost my last first cousin [in July].

I don’t have any people in my generation, unfortunately, anymore. I belong now to a Swedish lodge here in Chicago, [Verdandi Lodge Number 3 in North Park]. And it’s good, there are a few people that still—they’re certainly not as old as I— speak Swedish, and they want to retain that lodge [tradition]. Twice a month, we meet and have a little regular business meeting, and then of course we just have coffee or something a er. I have been a member for the last five years. It’s the only lodge that I can really recall here in the Chicago area. [Membership has] just gone down because, well, the older people are getting old, and their children

With 14 front-of-house restaurant jobs behind him, Ju stin E. Arnett-Graham, 39, has built a multifaceted career within the hospitality industry, largely in support of the tens of thousands of faceless workers in the trenches. As the creative director of beCo, he blends the art and media industries with a hospitality platform. As the founder of the events curation outfit Garn:t, he creates branded, chef-driven happenings outside the traditional four walls of the restaurant environment. And with backof-the-house veteran Nariba Shepherd, he cohosts Terms of Service , a podcast that explores the dark side of the restaurant industry with the aim of improving it for everyone. Arnett-Graham has even more projects in the works, but he still manages to hold down one shi a week for a major Chicago restaurant group, just to keep his finger on the pulse.

Interview by MIKE SULA

by Kirk Williamson

Ihad a stroke when I was two. I had to learn how to walk again. I was in speech therapy for years. My Rs came out like Ws. Shout-out to speech pathologists out there, because they are truly guardian angels. My journey with my own speech led me to create a platform for people to communicate authentically for themselves.

I have said for the longest time that the hospitality industry is the most inhospitable industry that we all have access to. And I would love that to change.

When I was 23 I was living in Columbus, Ohio. I got a job offer to be a server. I was making money hand over fist. It was just off campus. So we were packed. The food was trash. I had friends in the front of house, but I gravitated to the line cooks and the prep cooks. Those were my homies. They taught me what comida was. They were like, “amigo, amigo,” and put me together a little plate. It just showed me a different side of this stupid restaurant.

I started to wonder, “What does it feel like to be putting up food that is supposed to represent your culture through such a watered-down lens?” I saw them make things they were passionate about, while also on a food assembly line making smothered burritos with extra sour cream.

Terms of Service started because of the industry shutdown due to COVID. Everything we saw around us was GoFundMes for big players of the industry. There was no consideration for asking the people that make this industry what it is how the hell they were doing.

I got together with my colleagues, and I was like, “Hey, I think that we should sit down with the spectrum of the industry and ask them.” And so we did a little mini documentary called Six Feet Apart, from the perspective of restaurant laborers that no one was looking out for. We put that online and it really took off. We realized very quickly that there was no platform for the hospitality industry community to be represented. There’s always the well-to-do chefs talking about the well-to-do shit they do, which has nothing to do with the actual labor force that

brings this industry to life.

We wanted it to be light, fun, and engaging, while getting into some deep-seated topics of people’s lived experiences. I wanted to speak the language of the industry. Real talk. No bullshit. It started with us reaching out to our friends, and it grew from there. We took on more sensitive, topical conversations a er season two, because we started getting a lot of PR interest, and they were pitching things like, “Maybe you should talk about The Bear .’” And no, I don’t want to fucking talk about the goddamn Bear, unless The Bear wants to acknowledge that they’re capitalizing off the trauma of the industry. That’s when we got a lot more specific, because we didn’t want to be a platform that talked about this pop-culture phenomenon when we’ve lived it for years.

Shows like Chopped and Bar Rescue are in our faces every single day, and the general public feels like everything is absolutely fantastic, but they don’t understand the type of demons that we all face in this industry.

We’ve talked about sex work in the hospitality industry. Bad behavior within the industry from a chef’s perspective. We’ve talked financial sustainability, financial wellness, financial management— which hospitality businesses don’t seem to give a shit about. Parenting within the industry. We’ve explored losing yourself just for critical acclaim. Mental health. Alcohol- and drug-related issues. What does it look like to ensure that you’re taking care of your body, to ensure that you can perform the task of your job?

We’ve talked about food waste, food sustainability. We’re going to be dropping an episode with the Orange Tent Project about homelessness, painting the reality that everyone is closer to homelessness than financial sustainability in this industry.

When we sat down with [southwest side state] Senator Celina Villanueva and Mike Moreno Jr. [Osito’s Tap, Moreno’s Liquors], that was a very specific conversation directed toward our industry about how we can have migrant protections for our

I’ve been in theater since junior high, and then I was captain of my high school speech and debate team. I’m a real nerd, but I didn’t start dancing until college. I was originally focused on playing soccer, and then one day I just decided I was bored with that and wanted to do something different. There was an extracurricular program at Truman State University where you could take all these different dance classes for free. On a whim, I took a ballet class, and then I just got really invested in it. That’s where I started taking belly dancing and burlesque classes, too.

There was a burlesque performer named Lola van Ella from Saint Louis who decided to host a burlesque workshop at my school. She was a really important influence on me because she was the instigator that got me involved in things like the Show-Me Burlesque Festival and other productions in Saint Louis. She also introduced me to performer and producer Bazuka Joe, who is now a huge part of the Newport Theater.

reflecting a bunch of different cultures that may or may not be your own. So when you try to fuse or add things to it, you really want to be mindful of its origins. I found that there were a lot more opportunities to work and create under the burlesque umbrella. As long as you aren’t being offensive or punching down, there is a lot of freedom to explore and create new things.

Lola started hiring me to do some shows in Saint Louis, and I ended up moving there for its art community. There were a lot of creative people there doing things that were really out of the box when it came to burlesque. There was a lot of performance art infusion that was really different than what I interpreted burlesque to be. For instance, at a festival, one of my friends did an act where she was a robot and then she turned into a flower, and I was just like, “I can’t believe that. You can do that in burlesque? There’s a space for that?”

The Uncanny Attic , which was part of Steppenwolf’s 2025 LookOut Series. The Newport Theater will be hosting its annual Bump and Grind Ball fundraising event January 24.

Born in Cary, Illinois, Eva la Feva is a Chicago burlesque and belly dancer. She is also the founder and artistic director of the Newport Theater, a cornerstone of the city’s burlesque and fringe theater scene, and the founder of Feva Pitch Productions, a burlesque and nightlife entertainment company. Her work blends comedic neoburlesque and classic styles, and she is a prominent and sought-a er performer in Chicago’s nightlife scene. La Feva has produced notable shows such as the Clipper Cabaret, Siren Song Cabaret, and Found’s Quarterly Burlesque Revue, amongst others. La Feva also originated the role of Clara in the absurdist dark comedy

A er I graduated, I moved to Columbia, Missouri, and started dancing with a company there called Moon Belly Dance. I was training pretty extensively and then got into a series of random opportunities. For a while I was touring with a traveling belly dance company called the Bellydance Superstars as their merchandise person. I wasn’t dancing, to be clear, but it allowed me to travel with a bunch of dancers and see them prep for shows. It was interesting to see how organizers ran things and how shows were structured. It also showed me how to organize large groups of dancers, [and] how people connect with each other so that everyone has the same level of emotional investment, which I think is really important for success. Everyone needs to kind of rally around the same flag, so to speak.

I also did a couple of shows with a group called Bellydance Evolution which was also a touring company. Basically, they go to different cities—I performed mostly in New York and Washington, D.C.—and cast people to be in their chorus line.

I really loved belly dancing, but the gig opportunities are a bit more limited, and you’re obviously

As a performer, I have a hard time being serious ever, onstage and off. I try to always put some level of comedy or tongue-in-cheek into my work. For better or worse, sometimes I cling to really stupid ideas that I just think are really funny and then I won’t let go of them until I see them realized. I really enjoy, as an audience member, seeing the fusion of humor and sensuality because I think there’s a lot of people who don’t always feel coordinated or sexy, so it’s nice to have permission to laugh and smile at yourself. I have to explain a lot to people that when a burlesque performer calls something stupid, it’s one of the highest compliments we can give to each other. “That act was so stupid!” I bounced around a lot in my early 20s, living on people’s couches and stuff in a lot of different locations. I moved to Chicago a er living in Spain with my sister because I was kind of broke from teaching English there. I came home to regroup and save some cash and then sort of fell into the performance community here where, like in Saint Louis, there were a lot of people doing really interesting fusion work and putting together concepts that I thought were really artistic and different. Wanting

Reverend Dr. Luther Young Jr. is approaching his second anniversary as pastor of worship and spiritual formation at Lighthouse Church in Lincoln Park. The Black-centered LGBTQ+-affirming church was founded by Reverend Jamie Frazier in 2013 to address inequities experienced by queer Black Chicagoans and create a place of worship welcoming to all. A sister organization, the Lighthouse Foundation, was launched in 2019 as a Black LGBTQ+led multiracial social justice group that promotes physical, spiritual, and economic wellness through education and cultural events.

Young is also an assistant professor of religion and society at Boston University School of Theology. For the past five years, he’s served as board chair of the Indianapolis-based Disciples LGBTQ+ Alliance, which works to help the Dis-

ciples of Christ denomination become more affirming and inclusive of LGBTQ+ people. Young, who earned his PhD in sociology at Ohio State University, is currently working on a book project on Black LGBTQ+ people in the church, and has already authored scholarly articles on the topic for Sociology of Religion and the Journal for the Scientifi c Study of Religion

Young says that when he’s asked fellow Black clergy how their churches address the subject of sexual orientation and gender identity, they’ve responded that their leadership is afraid of backlash or that their congregations simply “aren’t ready” for the conversation. He’s here to correct those misconceptions. “I tell them I interviewed [congregants], and they’re ready for this conversation. They’re waiting on you.”

Interview by DEVYN-MARHSALL BROWN

Photos by Kirk Williamson

Lighthouse was founded in 2013 and has since blossomed into this really thriving ministry, a safe haven for Black LGBTQ+ people, but also a space for all people. We are a church of a variety of gender identities and expressions, sexual identities, orientations, expressions, and belief systems. Not everybody who attends Lighthouse Church regularly or [is a member] of the church, I would say, consider themself to be Christian. We are a Christian church, but we do make space for that diversity. As long as you can align with our central mission of being passionate about Jesus and being serious about justice, and our core values around love, liberation, and inclusion, there’s a space for you.

Jesus was all about liberating folks, bringing them into greater community, and dismantling systems of oppression and unjust power. And it is with that lens that we approach scripture. Our sermons will always have a justice component where we ask, “Who is the most marginalized in our society? Who is the most oppressed? Who are the ones who are being le out? And how can we, as followers of Christ, seek to mitigate that oppression, seek to uproot those systems of injustice?”

Progressive Christians sometimes say “Throw away the Bible,” but we’re not interested in that at Lighthouse. We dive into and wrestle with how texts have been used versus what the text actually says. We don’t harp too much on the overtly political [nature] of our sociopolitical landscape, partly because the folks who go to our church live it every day. We can speak to those issues, but also it is a space where we can—at least for those 90 minutes—not be subject to those issues. . . . We have other space for that, such as Real Talk, the [social] hour a er service. We try to foster community in a space where people can thrive and have a respite from all that is happening in our world.

I grew up Pentecostal in South Carolina, and so that was my church experience until I became an adult. A er I le home, I moved to Nashville, Tennessee, and attended Belmont University for undergrad. I majored in audio engineering tech-

nology and did some work in music production and studio production, both in church and studios. I went to seminary at Vanderbilt University and did my masters of divinity there. It was there that I discovered the Disciples of Christ.

In seminary, apparently there were people who didn’t know I was queer. So I was like, “Hey, in case you didn’t know, I like guys.” And that did not go well with the church that I was serving at the time, which was a Missionary Baptist Church. I ended up leaving that church, and the Disciples essentially welcomed me with open arms. It was a very complicated time, because that church was [where I was doing] my internship for my degree program. And so I lost my church. I lost my community, I also lost my internship in a really short time. I was able to intern at a Disciples congregation, and I discovered there were Black folks who were Disciples. Some of these churches are great, but I need a church experience with other Black folks that can speak to and hearken to the lineage and legacy of Black Christianity. I found that with the Disciples, and so I connected with New Covenant Christian Church in Nashville, where I was ordained, and I have been part of the DLC ever since.

In that process, I realized I was interested in anti-racism work and LGBTQ+ inclusion in Black churches. There’s just not a lot of folks who have really delved into issues of gender and sexuality in predominantly Black churches. There are some, but there aren’t a lot. That was God’s way of telling me, like, “Alright, well, I guess you better go in and help develop some of these resources.”

I am interested in the role that religion plays in people’s everyday lives, not just what’s happening on Sunday morning. In what ways is religion helpful for mitigating systems of oppression, or in what ways does religion engender systems of oppression? I went to Ohio State University for my PhD, and that’s one of my areas of expertise—social inequalities in the world, but specifically looking at that within the context of Black LGBTQ+ people in Christianity.

“We’d play for the dance so they could remember back home.”

have never belonged to it.

I met a lot of people—of course, at my age, [they’re] all gone—at the Swedish clubs that they had along Clark Street. And the stores here—I remember going with my father. We would buy the herring at Christmastime that was in the old wooden kegs, imported Swedish beans in gunnysacks—and that [era], it’s disappeared. But I still continue to make glögg at Christmastime. I’ve been making glögg for 50 years, as far as that goes. I bought a new garbage can, a 20-gallon, and we would make 20 gallons of that before Christmas. It was always so good to have that fragrance—it felt like I had been drinking! We wanted to have that tradition. I still make 20 gallons of it at Christmastime and give it away. But I taught my grandchildren; they know how to make the glögg for me.

When I came back [from the navy] in 1956, [we] bought a home there, and I’m still living there.

[People say,] “Go to assisted living.” I said, “That’s like going to a motel. No.” It’s helpful, my daughter—she’s close to me, and she helps me, shall we say, “downsize.” I’ve got my backyard; I do my gardening. I’m in a dahlia club, so I raise dahlias annually. I have to work on my hands and knees now, but at least I can get out and work on them.

I’m glad that I was able to put all four of [my grandchildren] through college, and they hopefully have a better life, as they say. I’ve had a good one. Other than the fact of my wife passing. I had a tragedy—I lost my son six months after my wife passed away. So it was not a good year. [But my wife and I] had 65 years together, and we resided here in the Chicago area, out in Park Ridge.

colleagues, and what does that look like from policy into practice?

We put up something online, just saying how the industry has been too quiet. It’s one thing to not understand how to navigate this situation, but it’s another to see it come into your community, affect your neighbors, your colleagues, your friends, and not say a goddamn thing. And that is something that I have a very significant problem with, because if you’re not doing anything to protect our own, then you never gave a shit in the first fucking place.

We got some crazy DMs when we made a public statement against ICE and the threat of the National Guard coming to Chicago from some very surprising individuals: signifi cant chefs that feel as if what’s happening right now is just collateral damage. And I was like, “Wow.”

fear and a desire to protect your staff. They’re naturally going to admit the latter. But the reality is, I feel like it’s cowardice, because they don’t want to isolate their consumer base. It’s capitalism at the end of the day. They just want to make sure that they’re making money. What seems to be the norm out here right now from numerous restaurant groups with regard to ICE protections for unprotected labor in this industry is that there’s no internal cultural dialogue as to what they’re doing, outside of just holding them at the door. The reality is that the employers want to remain compliant so they don’t seem biased. That’s a very hard pill for me to swallow.

The hardest part is getting up.

Truthfully, I don’t think about my age anymore, other than the fact that I can’t do what I used to do. I get tired more rapidly. And it just bothers me because, you know, I figure, “I can still do this.” Well, I can, to a point. And then I just gotta realize my body is just not strong enough. So I work as long as I can. If I get tired, I rest. I have nothing that can’t wait. If it doesn’t get done today, it’s hopefully gonna get done tomorrow.

So that’s about it. As I say, I’ve enjoyed my life, certainly. If I do it, I have to do it slower— go from day to day.

The world has changed, but it’s for the better in some ways. Others—can’t do anything about it. v

m tmcfadden@chicagoreader.com

We got one from a wellknown chef that was saying, “Yes, there are immigrants here that are doing it the right way, but amongst potential criminals.” I was like, “Well, that’s fascinating, because you’re actually in charge of a significant restaurant group. These are not only members of your staff. They’re also community members.” He didn’t like my response, so he blocked me. He’s like, “I thought you guys were great, but you’re just leaning one way that doesn’t understand the functionality of the industry.”

This silence comes from a combination of

Across the board the hospitality industry isn’t saying anything because it isn’t threatened the same way that it was during COVID. That affected literally everyone, and now ICE only affects a very specifi c percentage of the industry—the most vulnerable, the most overlooked. It’s the people that make this industry run all day, every day, without any sort of acknowledgement. It’s easier for people to look the other way. I do want to acknowledge those in the industry for navigating a difficult reality. My hope for my colleagues and people that I will never meet is to ensure that you always remember to give a shit about the stranger that’s next to you, because you never know how important that is in general. v

m msula@chicagoreader.com

“I wanted to speak the language of the industry. Real talk. No bullshit.”

to play in that sandbox with everybody is what made me stay here and eventually create the Newport Theater.

A couple of things happened that kind of set that stage for the Newport. The Uptown Underground [which later became the Baton Lounge and reopens soon as Chicago Eagle] was a burlesque venue that a lot of people performed at that shuttered unexpectedly. Overnight there were a lot of burlesque shows that had been running their productions there that no longer had a home. There was this period where we were all asking ourselves, “Where do we go now?”

At the same time, my partner at the time, Adam Burke, who is a Chicago comedian, was doing a show at Under the Gun Theater. He introduced me to Mark Geary, who is the head of Tight Five Productions [Geary is also the cofounder of Lincoln Lodge]. The Under the Gun space was always meant to be a kind of temporary location for them but they ended up being the sole renters, so when they were about to leave, I had a conversation with Mark about taking over the space to create a venue for burlesque and variety shows. He told me, “OK, put it on paper. Let’s put together a budget and figure out if there’s a way we could make this work.” Mark had a huge influence on getting Newport off the ground, which meant a lot because he’s not even really affiliated with the burlesque community.

of competition. We run classes and try to give people opportunities to launch their projects and get support. We try to keep the rent for producing in the space low in order to be accessible. I really appreciate the way Bazuka Joe has structured our classes because each teacher has pretty much full control over how they want to run their class.

In June of 2019, we officially launched the new concept. One thing the Newport really focused on early on is collaboration instead

I think one of my greatest assets as a leader is that I’m able to attract really wonderful people who contribute to the Newport. This project started as just something I was doing, but now the Newport is really a collection of so many people like Bazuka Joe; Natanya Rubin, who manages [weekly cabaret show] Peek-Easy; Jesse Genito, who started as a bartender and is now our studio manager and in-house photographer; our marketing team—all these people working together. I think a lot of Newport’s success is that I really do feel like we’re an artist collective. Something that sets the Newport apart is a very come-as-you-are energy. We don’t judge. We’ve had a lot of people say they’ve done a lot of gender exploration or other identity searching through our classes. I think it’s really important to have a space where you can create and be excited and not feel like you’re being judged. I know there was a period in burlesque history where there were more rigid ideas about what you could do on stage; you had to wear heels, you couldn’t do this, or you couldn’t do that. Our approach is you can do anything. v

m crenken@chicagoreader.com

“As a performer, I have a hard time being serious ever, onstage and off.”

“Oppression likes to thrive in the shadows. Injustice likes the secrecy.”

YOUNG from p. 15

I feel like there is an assumption that the Black church is just homophobic and transphobic. I was really wanting to interrogate that. When I saw these instances of Black preachers railing against queer communities, folks like Kim Burrell. (That girl stay in the limelight. She don’t know how to be quiet!) The question that would always come up for me is, “Gosh, what was happening in the room? Were people shocked? Were people appalled? Did anybody leave?”

[ Editor’s note: Kim Burrell is a Texas gospel singer and pastor who came under fire in 2017 for her anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric, which she publicly apologized for in 2024.]

it’s going to be an issue. Or they may be OK with y’all being there, and everybody knows that y’all are together—but they’re not going to perform your wedding ceremony.

If you read any of my articles, there’s usually a line in there somewhere that says the Black church is not a monolith. There’s a diversity of perspectives, and that diversity can be surprising sometimes. Some churches are just LGBTQ+-affirming all the way. Some make it very clear that they believe that homosexuality is wrong and marriage is between a man and a woman, and then there are churches in the middle. And I argue that a lot of times those churches in the middle can be most interesting to examine. . . . This can range from churches that may not say gays are going to hell, but if you go to church holding hands with your same-gender partner,

I would argue, the majority fall in that middle ground. There’s a whole lot of variation in there, and that variation—what I’ve argued in my work—is what has allowed a lot of Black queer folks to go to church, because they can find one that’s accepting enough. Completely affirming churches like [those] in Chicago don’t exist broadly across the U.S. When I’ve asked people, “Why do you choose to go to this church over another?,” there are all kinds of answers that go with that, such as, “My family goes to this church,” or “This was the church that I was raised in and I don’t want to leave that.” Or “I don’t want to go to a church that’s all about my sexuality. I want to go to a church where I can just be somebody. I want to just pick a church because I like it, because they’re not going to send me to hell every Sunday.” If we can start from a lens of perhaps the Black church is just not this bigoted institution, but rather there’s a lot of diversity here, we might be able to shift more churches to be more accepting, affirming to, and advocating [for] LGBTQ+ members. v

m dmbrown@chicagoreader.com

Bozhi Tian makes huge stuff happen using some of the tiniest pieces of the universe. Born in Xi’an, China, and educated at Fudan University in Shanghai and at Harvard, he dreamed of a career in the visual arts before a high school chemistry class inspired him to pursue science—where his creative spirit and imagination have taken him far.

Tian is now a chemist and professor at the University of Chicago, where he founded the Tian Research Group in 2012. He’s done pioneering work in photo-

electroceuticals and living bioelectronics, creating drug-free, cell-based, nongenetic therapies that integrate electronics with biological systems and promote healing in a way that prioritizes environmental sustainability and a better, more humane world. A proud mentor to the next generation of Chicago scientists, Tian believes passionately in the role of imagination in scientifi c advancement— and he continues to create visual art that, like his lab’s breakthroughs, merges nature and technology.

Interview by JAMIE LUDWIG

Photos by Kirk Williamson

My father, he’s the artist. He practiced calligraphy. So when I was three years old, I started calligraphy. When I was six, I started to change to something slightly different—painting— and I found myself more interested in that. I started with traditional Chinese painting; the paintbrush and a lot of the ink is the same as calligraphy. Later, I practiced oil painting and watercolor as well. When I was 14 years old, I started to learn chemistry. I still remember the instructor playing with some chemicals, and there were a lot of color changes. I was so fascinated—I started to [think] maybe I should consider science as my career path. Before that, my parents and I believed I probably should pursue an art career. I even thought I should be an architect, because I loved art, threedimensional objects, and mathematics. But I really felt that science probably had even more fascinating things and mysteries.

The real beginning of my scientific journey was in 2000, when I joined a research lab for the first time during the summer before my junior year [of college]. I studied nanoporous materials—essentially, a porous material, but the size of the pore is at the nanometer scale. What’s remarkable about nanoporous materials is that the pores are highly ordered. They can be arranged in a honeycomb manner, like two-dimensional and threedimensional patterns. I found a lot of fulfillment in doing the science and having direct experience with those beautiful things.

I think [my art background] has certainly helped my research, especially when nature-inspired processes are involved. That’s number one. Number two, I vividly remember that when I practiced calligraphy as a kid, I had to sit there at least five hours just to pay attention to the details. This is a good habit, because when we’re doing science, we need focus. When we focus, time goes very quickly, but we can capture finer details and make discoveries. The third thing is that I sometimes feel that I have a better capability to draw connections between two things that seem like they have no connection or a transdisciplinary connection. Let’s say I try to

design some electronic devices or optoelectronic systems that can emit light. I’ll start to think how in nature, some insects, their surfaces can reflect light. [Making] those connections sometimes gives me fresh ideas.

At that time, the majority of the [nanoporous] materials were insulators, so they do not conduct electricity. A er finishing a lot of projects, I realized I probably needed to work on something that, in terms of function, could be more diverse. Then I thought about electronic systems, especially semiconductors. Starting from my PhD, I started to focus on semiconductor materials, especially silicon, because silicon is the most important building-block material for a computer chip or solar cells. My first PhD work back at Harvard was actually about solar cells.

After I finished that project, I realized the biology system is even more fascinating because there’s a lot of unknowns. So why don’t we choose to combine biology with a semiconductor system and do some interface?

So that’s the starting point of my career in bioelectronics, around 2008. My postdoc was in bioengineering. I learned tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, [and] it became natural for me to combine electronic systems and biological tissues in a more seamless manner.

Our lab is highly diverse, and I intentionally make it diverse. For example, my postdocs are mostly engineers: There are bioengineers, there are electrical engineers, and there are environmental and science engineers. And my graduate students: There are chemists, there are biophysicists. In my early time, we also had a medical doctor, a PhD student. We need people with very different backgrounds so that we can do highly interdisciplinary work. Collaboration is not just a way to enhance the quality of the work; it’s a way for me to learn from my collabo-

“We

rators. For example, for medical doctors, I have a collaboration with a cardiac surgeon; I have a collaboration with a neurosurgeon working on sleep-disorder treatment. I also have a collaboration with an orthopedic surgeon—we’re thinking of designing a device to monitor patients’ recovery a er shoulder-replacement surgery.

I also have a collaborator who is a pediatrician. Recently we developed a remote sensor that can potentially detect the stress hormones of preterm infants. [And] we designed some device that can mimic kangaroo care. This is important for preterm infants; they don’t have enough time for skin-toskin contact with the mother. So we designed an artificial system that can mimic that process. Not just for this skinlike feeling—we can also create a heartbeat sound or play music or do things like temperature regulation or mechanical motion.

So we have the fundamental side. We also have the translational side. There are a few very important translational examples in my lab. The most important is the optically driven cardio pacemaker. Traditional cardio pacemakers are pretty bulky and rigid. So we developed something extremely thin and lightweight, where we can use light pulse instead of electro pulse for heart pacing. We’ve also developed a skin patch that can be used to treat psoriasis, a type of skin inflammation. In the device, we have the wearable electronics part, which is flexible and stretchable but also has living cells, which are commensal bacteria. They’re not dangerous. In fact, they

can actually help us treat skin inflammation. And these two are examples of what we call photoelectroceuticals and living bioelectronics.

In my lab, my philosophy is that I don’t want to create internal competition. Every individual has their own project that’s very distinct. This is healthy, because they can take their time and focus on the depths and innovation instead of launching a project in order to compete with each other. It also provides the opportunity to collaborate and support each other.

One of the typical questions we try to address is, “How does this device help us instead of invade our privacy?” Almost every player in the bioelectronics community has to be cautious in terms of our device design, especially when the device involves wireless components—because wireless components mean that potentially other people can get the data remotely without permission. But we’ll make sure, for example, the data collection distance would be limited to just less than a few centimeters, so that you can only use something like your cell phone to collect the data and it won’t potentially be detected by other people.

There are strategies to navigate this, and I really feel that as a professor, as the manager or leader of the research group, we have to train our students and postdocs really well to let them know the right things to do and what are not the right things to do. In our community, we mostly have agreement and know what areas we should try to work to solve the problem. Other areas, we just step away and focus more on the fundamental side.

I really feel that as a scientist, the most important thing is fi rst to be a good person and have a good personality. And then you do great science. If you have hobbies like art, that’s great. If not, that’s also totally fine, but being a good person, that’s the number one most important thing. We want to design materials that benefit humanity. We want to do good things instead of going to the other side. And also, this field relies largely on collaboration. So we need good people, and then the collaboration will be more fruitful. v

m jludwig@chicagoreader.com

Kyle Butler eats, sleeps, and breathes tattooing. The Aurora-born artist and entrepreneur has been collecting ink since he gave himself his first stick ’n’ poke at age 14 (it was the Deathwish Skateboards logo). A week a er his 18th birthday, he moved to Chicago to study creative writing at Columbia College and soon began home tattooing. Two years later, he dropped out to devote himself to what had become a full-blown obsession. Now 33, he’s the sole owner of the Irving Park street shop Red Devil Tattoo, which he started with Miranda Larson in 2021, and also runs a private, appointment-only studio nearby.

As tattooing moved from an underground industry to a “legitimate” trade in the late 20th century, home tattooing became frowned upon by the broader professional community. But

many artists—including many industry trailblazers—had started as so-called “scratchers.” Over the past decade, home tattooing has experienced something of a renaissance thanks to the wide availability of single-use needles (an industry standard since the early 2000s) and home tattoo machines, along with the ubiquity of social media as a tool for learning and self-promotion.

Butler embodies a shop owner who came from the modern underground. He remains excited about how reduced barriers to entry have led to fresh styles and ideas in tattooing. At the same time, he encourages a reverence for tattoo history and an investment in the cra smanship (such as learning to build one’s own machines) that’s o en lost to younger artists.

To Butler, tattooing isn’t a trade, it’s a lifestyle—and he can’t imagine any other.

Interview by MICCO CAPORALE

Photos by Kirk Williamson

Itattooed myself when I was 14. Then I got a tattoo in Indiana when I was 16 because you can get tattooed underage in Indiana, so we just drove over the [Illinois] border. Once I turned 18, I was getting tattooed all the time.