inks inks

THIS WEEK

DRINKS

04 Staff Note | Williamson Ice, not ICE 06 Roundup | Caporale & Sula Winter is coming. Here are five new bottles that will rekindle your blackened heart.

08 Feature | Caporale A tale of two wormwoods 12 History How immigrants shaped Chicago’s bar scene

16 Theater | Reid Drinking shows let you belly up to the theater.

CITY LIFE

05 History Chicagoans have long resisted legalized kidnappings of our neighbors

NEWS & POLITICS

10 Feature | Brown Tenants call for an eviction moratorium amid ramped-up deportations.

11 Make it Make Sense | Hugueley & Mulcahy Trump’s invasion continues, layoffs and labor issues cause strife at Uptown People’s Law Center, and city domestic violence services face budget cuts in 2026.

ARTS & CULTURE

14 Cra Work Yuliya Klochan uses Ukrainian loom weaving techniques in her colorful beaded artworks.

15 Art of Note Recommended solo shows at the Arts Club of Chicago and on the Art Institute terrace

THEATER

18 Plays of Note An enchanting musical version of As You Like It at Writers Theatre, a revival of Richard Foreman’s Bad Behavior, and a darkly comic adaptation of A Devil Comes to Town at Trap Door Theatre

FILM

20 Moviegoer Eye works

20 Movies of Note Predator: Badlands is unlike any other Predator movie, and Sentimental Value is tender and heart-wrenching.

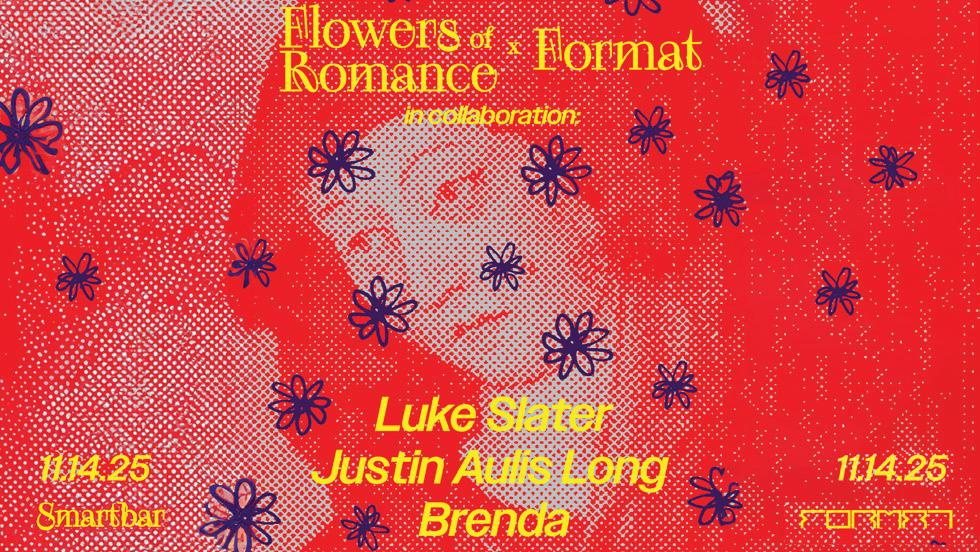

MUSIC & NIGHTLIFE

22 Secret History of Chicago Music Charles E. Gerber sparked kids’ imaginations as the elfin host of The Magic Door

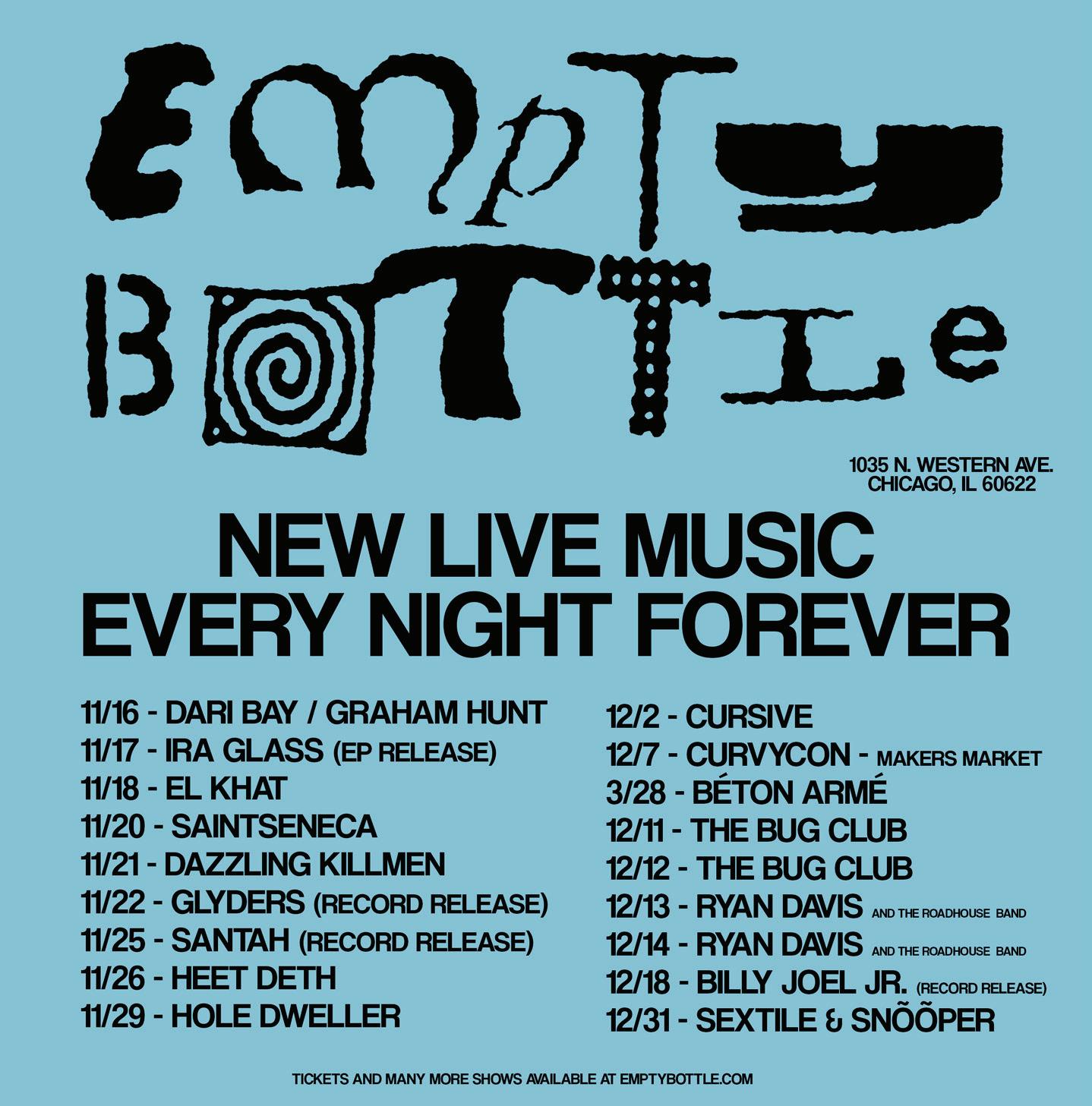

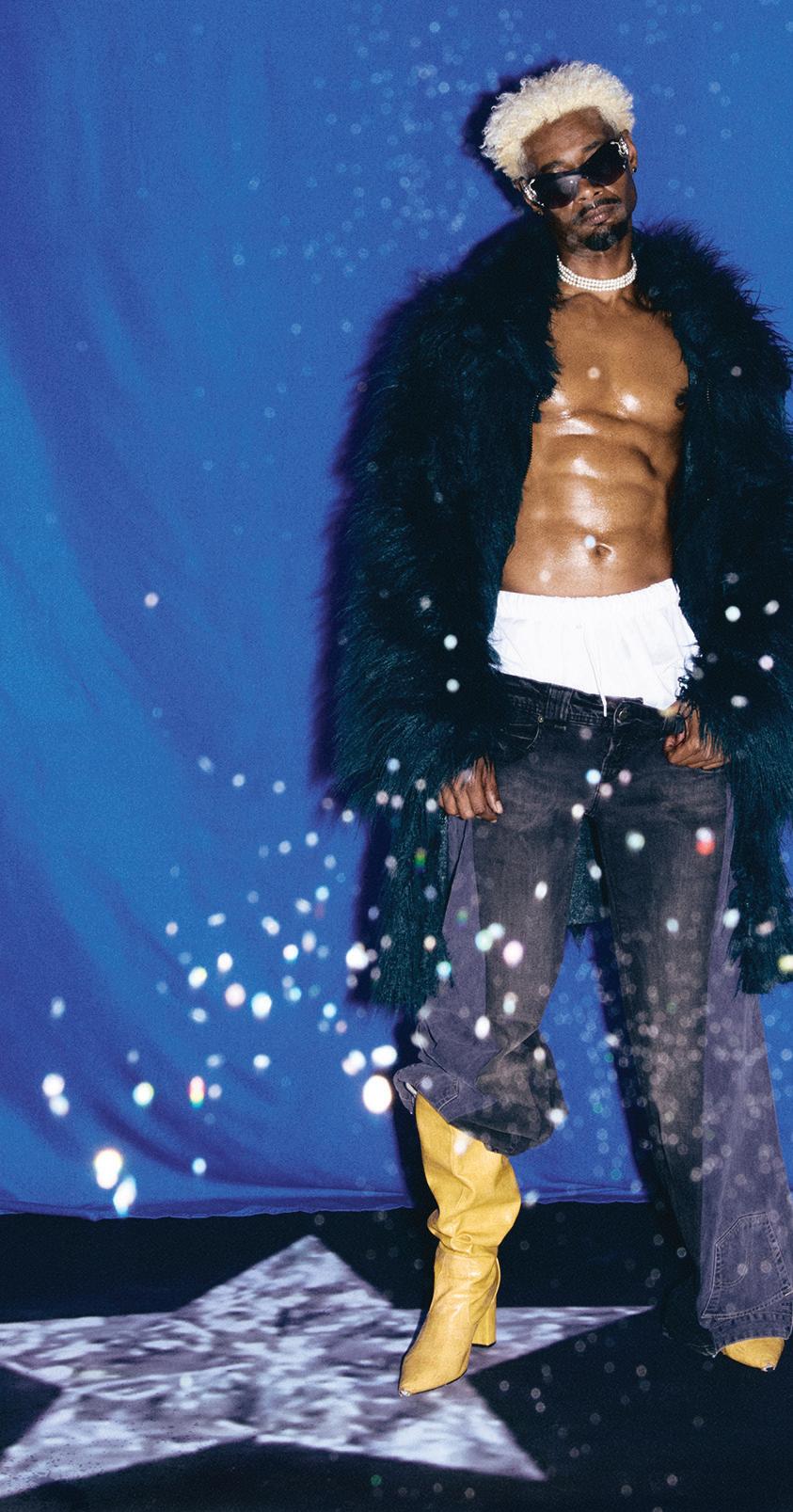

24 Shows of Note Previews of concerts including Pixel Grip, Rwake, and Danny Brown

26 Gossip Wolf Torn Light Records reopens a er a month of mopping up, the Fallen Log shuts its doors, and more. CLASSIFIEDS

27 Jobs

27 Services

Drinks

INTERIM PUBLISHER ROB CROCKER CHIEF OF STAFF ELLEN KAULIG

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR

SAVANNAH RAY HUGUELEY

PRODUCTION MANAGER AND STAFF

PHOTOGRAPHER KIRK WILLIAMSON

SENIOR GRAPHIC DESIGNER AMBER HUFF

GRAPHIC DESIGNER AND PHOTO RESEARCHER SHIRA

FRIEDMAN-PARKS

THEATER AND DANCE EDITOR KERRY REID

MUSIC EDITOR PHILIP MONTORO

CULTURE EDITOR: FILM, MEDIA, FOOD AND DRINK TARYN MCFADDEN

CULTURE EDITOR: ART, ARCHITECTURE, BOOKS KERRY CARDOZA

NEWS EDITOR SHAWN MULCAHY

PROJECTS EDITOR JAMIE LUDWIG

DIGITAL EDITOR TYRA NICOLE TRICHE

SENIOR WRITERS LEOR GALIL, MIKE SULA

FEATURES WRITER KATIE PROUT

SOCIAL JUSTICE REPORTER DEVYN-MARSHALL BROWN (DMB)

STAFF WRITER MICCO CAPORALE

SOCIAL MEDIA ENGAGEMENT

ASSOCIATE CHARLI RENKEN

VICE PRESIDENT OF PEOPLE AND CULTURE ALIA GRAHAM

DEVELOPMENT MANAGER JOEY MANDEVILLE

DATA ASSOCIATE TATIANA PEREZ

MARKETING MANAGER MAJA STACHNIK

MARKETING ASSOCIATE MICHAEL THOMPSON

SALES REPRESENTATIVE WILL ROGERS

SALES REPRESENTATIVE KELLY BRAUN

SALES REPRESENTATIVE VANESSA FLEMING

ADVERTISING

ADS@CHICAGOREADER.COM, 312-392-2970

CREATE A CLASSIFIED AD LISTING AT CLASSIFIEDS.CHICAGOREADER.COM

DISTRIBUTION CONCERNS

DISTRIBUTIONISSUES@CHICAGOREADER.COM

READER INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNITY

JOURNALISM, INC.

CHAIRPERSON EILEEN RHODES

TREASURER TIMO MARTINEZ

SECRETARY TORRENCE GARDNER

DIRECTORS MONIQUE BRINKMAN-HILL, JULIETTE BUFORD, DANIEL DEVER, MATT DOUBLEDAY, JAKE MIKVA, ROBERT REITER, MARILYNN RUBIO, CHRISTINA CRAWFORD STEED

STAFF NOTE

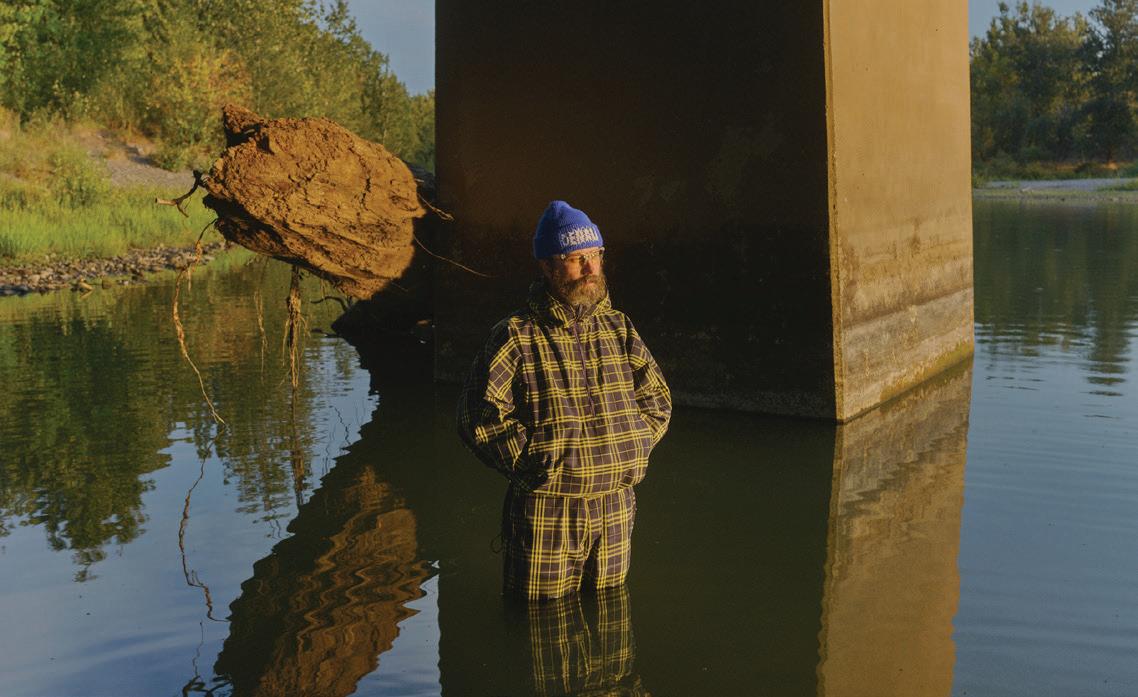

Can art only exist as an expression of beauty, or must it make a statement?

This was a question I had to ponder throughout the process of creating the cover for this issue, which features content related to drinking. What could have felt like a carefree caprice of a concept in a di erent time has now taken on an unexpected semantic workload. You can’t just take pretty pictures of ice and not think about ICE (Immigration

and Customs Enforcement). And this pisses me right the fuck o , both as an artist and as a U.S. citizen with a beleaguered conscience. As I came up with the concept for this cover, I went into the process with a zesty curiosity. I wanted to make ice that was as clear as possible and would photograph well. To do this, I used the “kitchen sink” approach, employing multiple methods to achieve the cleanest product. I used distilled water, which I then filtered and boiled. But for the most part, those tricks don’t matter too much. The key is a method called directional freezing, in which the sides and back of the ice tray are insulated, forcing all freezing action to come from the top, pushing all impurities down rather than concentrating them in the inaccessible center.

Satisfactorily as the end result may have turned out, it feels irresponsible to present this visual celebration of frozen water without addressing the elephant in the White House. Can’t a brother just make pretty pictures without it relating to the hellscape that is 2025 America? God, that would be nice. It’s my main wish—both for me personally and for my brothers and sisters in the fight for justice and a peaceful society—that we could do just that. But not now. Not today. I give it up to the Reader editors, whose job it is to steer this ship through the choppy waters of our turbulent political situation, always remaining upright and not taking on any water. OK, before I’m put on trial at the Hague for torturing this pitiable metaphor (which is more justice than the ICE jackboots

will ever see), I just want to say that it takes courage to continue to stand for what’s right, and I believe that we at the Reader and other local outlets have not wavered from that task. Our journalists have kept front and center in the fi ght and have provided coverage in a way that respects the victims of the current regime and have held the feet of the perpetrators to the fi re. Fire melts ice, after all.

So, this week, have a drink, stay cool, continue to kick ass, and tip your servers. v —Kirk Williamson, production manager/ sta photographer m kwilliamson@chicagoreader.com

CORRECTIONS

The Reader has updated the online review of Uz, el pueblo entitled “Town without pity, ” written by Kerry Reid and originally published in our November 6 issue (volume 54, number 6). The piece now correctly states that the son in the play is Tomás, not Jose, and played by Israel Balza, not Oswaldo Calderón.

The Reader has updated the online version of “Many unhoused Chicagoans uncounted among the disappeared,” written by Katie Prout and originally published in our November 6 issue (volume 54, number 6), to clarify that two abductions, on September 23 and October 24, occurred outside the same North Park shelter, and that the October 29 incident witnessed by Kiersten Solis occurred near Gompers Park, not Eugene Field Park.

The Reader updated some phrasing in the online review of the movie Violent Ends written by Kyle Logan and originally published in our November 6 issue (volume 54, number 6), to clarify the writer’s intent.

Find us on socials: facebook.com/chicagoreader twitter.com/Chicago_Reader instagram.com/chicago_reader linkedin.com search chicago-reader

The Chicago Reader accepts comments and letters to the editor of less than 400 words for publication consideration.

m letters@chicagoreader.com

Southeast Spotlight:

Medley Grill & BBQ

Bringing the best BBQ to the Southeast Side & beyond

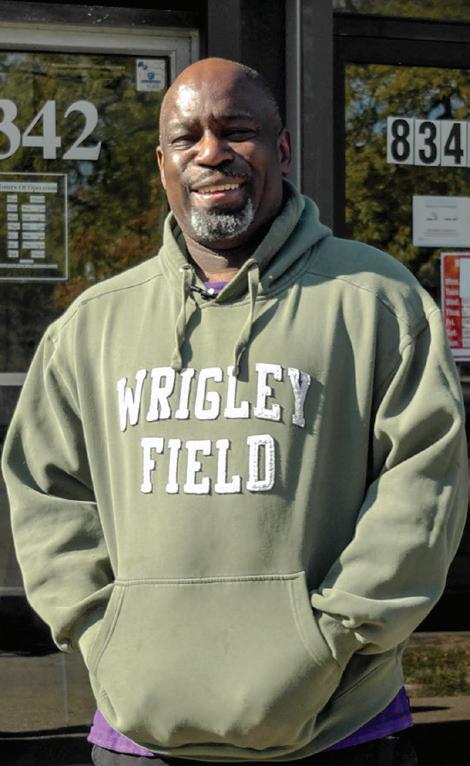

Any good recipe is rooted in family origins, but it often involves some variation and experimentation as it is passed through generations. Similarly, as folks move and travel and try new things, flavors and notes of those experiences follow them. This is exactly how Charles Thurman, founder and master barbecuer of Medley Grill & BBQ, conjured up his array of delicious dishes.

The name “Medley” reflects his process: a mixing of smoke, fire, and seasonings to cook food. What started as a passion in 2014 was slow-roasted into a brickand-mortar space in 2022. “It’s BBQ from the heart,” Thurman modestly shared. Every meal is made from scratch, ensuring quality and stellar taste every day. After years of building up the Medley Grill & BBQ brand, Thurman is confident in letting the smoky, soulful foods speak for themselves. Uniquely, Medley does not provide pork on their menu— making it stand out from most traditional BBQ restaurants—

but still offers a variety of delicious options for everyone, from turkey tips to all the sides one could need.

Like all good restaurants that keep us coming back, Medley Grill & BBQ prioritizes care and consistency. Thurman understands personally that people work hard for their money, so he wants to ensure that they are satisfied and full when they choose Medley for nourishment. Additionally, as a Black business owner on the southeast side, Thurman is fueled by the opportunity to serve his community with good food and good business practices.

When the weather is fine, especially during Chicago summertimes, Medley’s semisecret patio is a sanctuary to enjoy a meal alone or shared with some friends. Grab takeout or cater your next party with Medley Grill & BBQ. Be sure to follow along on social media to stay tuned for their next fish fry or Sunday backyard BBQ for the Bears’ game!

Medley Grill & BBQ

8340 S. Stony Island, Chicago, IL 60617

Wednesday 10:30 AM-7 PM; Thursday-Saturday 10:30 AM-8 PM; Sunday 11 AM-8 PM | medleygrillandbbq.com | @medley_grill_and_bbq 312-922-1272 or medleygrillbbq@gmail.com

KIRK WILLIAMSON

This content is sponsored by the Southeast Chicago Chamber of Commerce

Courtesy Medley Grill & BBQ

CITY LIFE

Chicago has always defied kidnappings of our neighbors

Even a er the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, local officials and everyday people resisted the legalized abductions of Black Chicagoans.

By JEFF NICHOLS

Chicagoans have a long history of making it hard for outsiders to abduct people o our streets. In the 1850s, lawyers, judges, and politicians jammed up the legalized kidnapping of men, women, and children who had escaped slavery. Ordinary Chicagoans refused to be silent when armed “slave catchers,” which included enslavers and bounty hunters, attempted to snatch Black people from public spaces.

Take the case of Uriah Hinch, a slave catcher from Audrain County, Missouri. Hinch didn’t know what the escapees looked like, so one of the enslavers who had hired Hinch “lent” out Henry Stevenson, a man who was enslaved at the time. Through Stevenson’s detective work among free Black people, the pair arrived in Chicago in October 1850.

Convinced that Stevenson was making inquiries among Black folks, Hinch tried to distribute fliers describing the people he was trying to kidnap, when, in the words of the antislavery paper Western Citizen , a few gentlemen “kindly informed” Hinch that he was “employed in an enterprise of personal hazard.” Meanwhile, Stevenson was on a boat to Michigan; he had connected with members of the Underground Railroad at a barbershop.

ers. Passed a few weeks earlier, the Fugitive Slave Act imposed heavy fines against anyone who impeded arrests. The a davit of a slaveholder was enough to put an accused Black person into permanent servitude. One correspondent to the Western Citizen reported that a Black man, who had escaped slavery just four years earlier, tearfully explained to a church congregation how the new law “had driven all protection from him, and he had no home, no

Moses Johnson into bondage on the grounds that Johnson’s appearance didn’t match an enslaver’s written description. Though penniless, Johnson had been defended pro bono. A boisterous crowd outside the courthouse jeered at the slave catcher.

Events in September 1854 only solidified the image in the pro-slavery press that Chicago was hopelessly lawless and corrupt. After antislavery activists heckled a speech by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, in which he defended compromises to pacify enslavers, papers across the south reprinted the description o ered by the Douglas-owned Chicago Times, which characterized the event as an attack on free speech by a radical mob.

Southern papers were appalled at how three Missouri slave catchers had been charged in Chicago for assault with a deadly weapon. They had hauled a formerly enslaved man across the sidewalk, firing a pistol at him as he attempted to flee. An indignant statement prepared by the defendants complained that some in “the mob came up to us and told us to leave, saying that we, or anybody else, could not take a negro from Chicago.”

Indifferent to the safety of Chicagoans, a Boonville, Missouri, paper fumed at how the man had been “assisted to make his escape,” while the “persons duly authorized to take him” had been thrown into jail.

and Bagsby were staying, Isbell gathered 14 other Black men who ambushed their cabin at Polk and State. Decades later, Isbell reckoned Calvert and Bagsby would have needed “a couple of weeks” to recover from their beatings. Federal pressure against Chicago increased as the Civil War approached. In November 1860, the kidnapping of a formerly enslaved woman named Eliza Grayson nearly triggered an uprising. Chancellor L. Jenks, an antislavery lawyer, clocked the enslaver who had stalked Grayson for the previous two years. Jenks connived to have the would-be kidnappers, who had procured a warrant against Grayson, arrested for disorderly conduct. Though Grayson managed to escape, Jenks and eight others were arrested for violating the Fugitive Slave Act.

Fearing for his safety, Hinch sought the protection of a Chicago judge, who simply referred him to an antislavery lawyer. Following the advice of his legal counsel, Hinch left town. The next day, the escapees arrived in Chicago. Had Hinch crossed paths with the escapees, he could have tried to get a warrant for their arrests, thus making U.S. marshals do the dirty work of subduing and securing freedom seek-

spot on earth he could call his own.” After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, one mass meeting of Black Chicagoans resolved that “we will stand by our liberty at the expense of our lives.” Though there were white Chicagoans who vigorously defended the law, a clear majority of Chicagoans resented the political and economic power of slaveholders. After some flip-flopping, Chicago aldermen passed a resolution condemning the Act on the grounds it infringed on basic civil rights; the city would not volunteer its police force to help enslavers. The Act had been crafted to force communities like Chicago from being a sanctuary for freedom seekers. In June 1851, U.S. commissioner George W. Meeker refused to send

The threat of violence between the hired goons capturing freedom seekers and the communities that protected them hung over the city. In December 1854, Saint Louis slave catchers obtained warrants for 17 escapees, the news of which spread quickly. Receiving no help from the mayor to deal with potential conflict with gathering crowds, the U.S. marshal from Springfield called in the National Guard. In the commotion, no one was captured. Lamenting the future economic damage to Missouri, a furious correspondent to the St. Louis Republic wrote, “I would not recommend any citizen of a southern State to attempt to get his property here with being well backed by a strong force.”

A few months later, a U.S. marshal tipped o Lewis Isbell, a Black barber, that two slave catchers from Missouri, Joe Bagsby and James Calvert, had asked them to arrest two freedom seekers. Isbell sought out the two Missourians, who o ered Isbell a handsome reward for his help. Now, having found out where Calvert

On April 3, 1861, J.R. Jones, a U.S. marshal appointed by President Abraham Lincoln, executed the early morning arrest of the Harris family. Angry neighbors followed the family of five to the train station, but they were unable to be rescued and were eventually returned to bondage in Missouri. This incident triggered a panicked exodus of Black Chicagoans. Bashed by the pro-Lincoln press and under a new set of priorities with the start of the Civil War, Jones stopped hunting freedom seekers. The charges against Jenks and his compatriots were also dropped. There is much to admire in the town that stood up against the Fugitive Slave Act, but it was no racial utopia. It was one thing for white Chicagoans to hoot at slave catchers—yet another for them to consider Black Chicagoans their betters, let alone their equals. When the Underground Railroad was but a memory, white Chicagoans could imagine themselves as its indispensable leaders, relegating the stories of those like the barber, Lewis Isbell, to the margins. In reality, as Larry A. McClellan writes in Onward to Chicago: Freedom Seekers and the Underground Railroad in Northeastern Illinois, Isbell was “at the center of activity for assisting freedom seekers.” Isbell was recognized as a leader among his Black and white peers, who might have helped, directly and indirectly, up to a thousand people find freedom in Canada.

Today, Isbell lies in an unmarked grave in Mount Olivet Catholic Cemetery. Stephen A. Douglas, whose business portfolio included a 2,500-acre cotton plantation in Mississippi, lies in a grand monument overlooking the lake. v

m letters@chicagoreader.com

Chicago Tribune article from September 12, 1854 CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Drinks

ROUNDUP

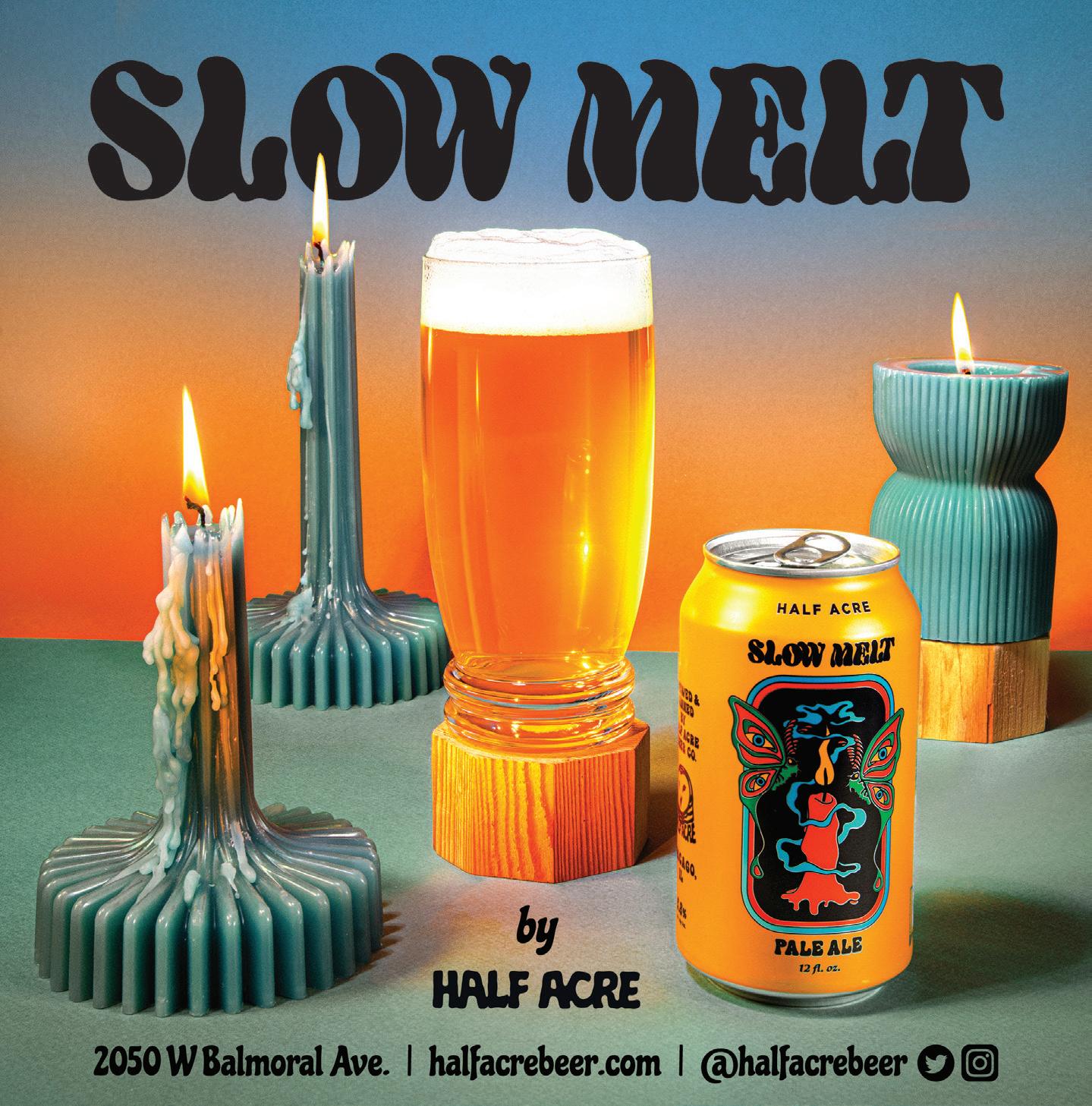

New local spirits to li your spirits

Winter is coming. Here are five new bottles that will rekindle your blackened heart.

By MICCO CAPORALE & MIKE SULA

Last summer, I was dithering with a friend in the tequila aisle at the liquor store and grousing about mezcal and other agave spirits’ superiority to tequila, the less compelling and deceptively manufactured social lubricant and regrettable emetic of frat houses everywhere. A stranger rolling his cart overheard, stopped, and insisted on buying us a bottle of his own tequila brand. We took it to a party, and when I tasted just how complex and interesting it was, I hid it away before it was completely drained. I only learned later that our mysterious booze benefactor was none other than Chef John des Rosiers—best known for Lake Blu ’s fine-dining restaurant Inovasi—who’d just launched his own brand a year earlier, informed by his decades as an ad hoc sommelier in every restaurant he’s ever worked. With the holidays approaching, Chicago is awash in similarly interesting, newly released local spirits. Here are a few we found that were our great pleasure to sip—so you have to.

Apologue carrot liqueur

If carrot cake came in a liquid form, it’d be Apologue’s carrot liqueur. The distiller uses carrots from Marengo, Illinois–based Nichols Farm & Orchard and combines them with ginger, cinnamon, lemon, mint, citrus, and cinchona for a tooth-achingly sweet concoction that, when served alone, is best enjoyed in small sips after dinner. Like most liqueurs, it’s much better as a mixer, providing a versatile, earthy-sweet base that can ground fall flavors like orange and ginger with a hint of surprise. Of course, it goes with tonic; including cinchona in the recipe leaves the door wide open for more quinine flavor. Whiskey is an obvious partner spirit (bourbon

would be too sweet, in my opinion), but I tasted the most room for possibility in a smoky mezcal. Apologue’s carrot liqueur makes a great mixer for drinks trying to scream “fall”—but in the right bartender’s hands, it could be part of a drink so interesting it transcends the season. —MICCO CAPORALE $40, preorder for $35 at apologueliqueurs.com

Cambio tequila reposado

After marrying into a Mexican extended family, John des Rosiers and one of his 92 new first cousins rebuilt a Jalisco distillery to complement his roster of North Shore restaurants. Along with the additive-free blanco it’s built upon, the

French oak barrels.

“Cambio” means “change,” and while they adhere to traditional methods—whole agave hearts cooked in brick ovens, stone tahonas to press the juice, wooden fermentation tanks, copper stills—they’re also breaking new ground. Des Rosiers takes a vintner’s approach, using imported yeast strains more common to winemaking that coax rarely expressed flavors from the agave, fermenting at low temperatures, and bottling at a lower proof (50 percent ABV). Everything about the process is low and slow, taking three times as long as the average mass-market tequila, according to des Rosiers. Out of the bottle, it has a

vanilla-kissed, smoky nose, and a gently floral, caramel drift across the palate. No shots with this one, —MIKE SULA $54.99 at liquor stores all over Chicagoland

Granor hopper rye

Best known for its greenhouse dinners led by former Chicago chef and cookbook author Abra Berens, southwest Michigan’s

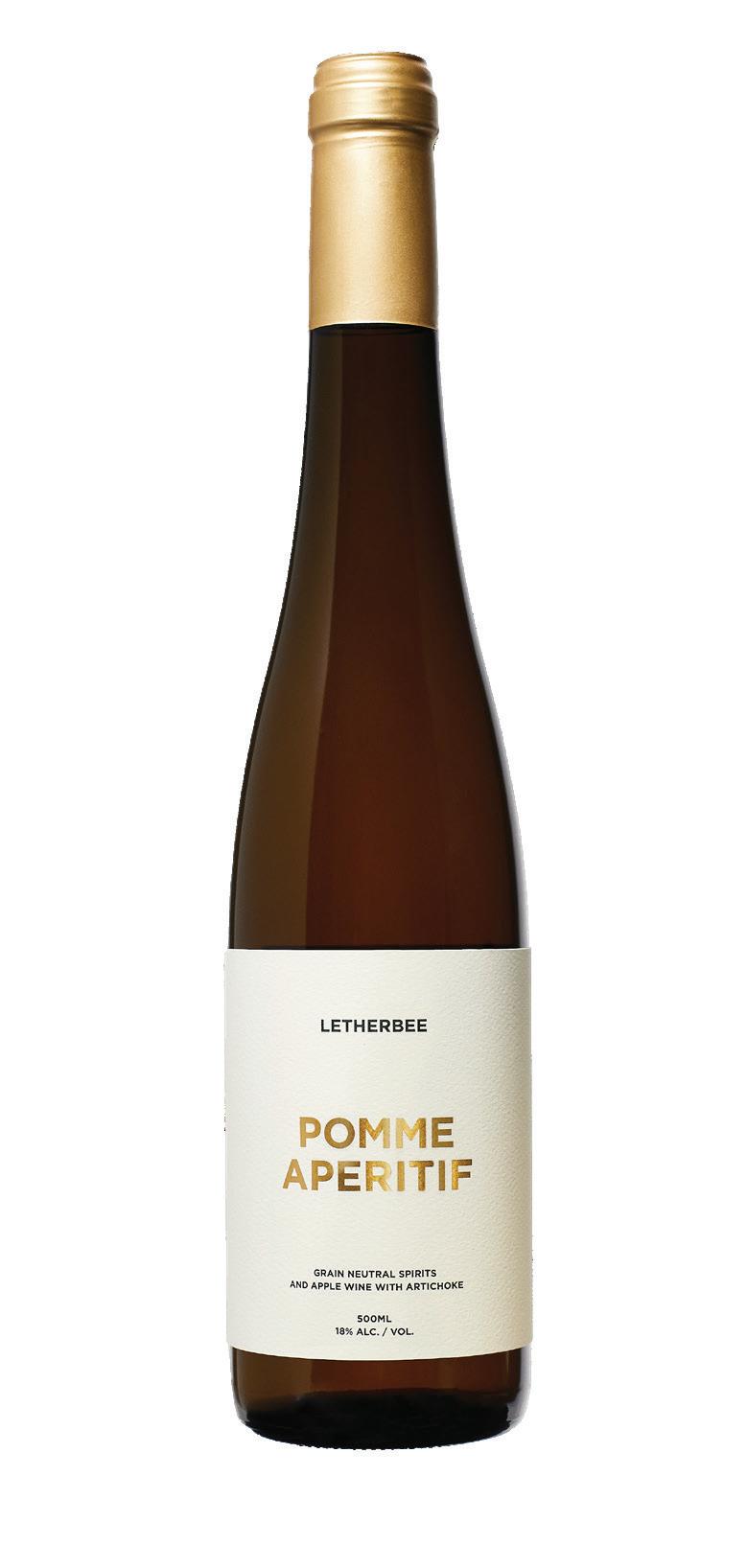

Leatherbee pomme aperitif

To make its pomme aperitif, Leatherbee takes the fermented apple juice, or “apple wine,” of Virtue, a Michigan-based apple farm and cidery, and fortifies it with a neutral grain spirit and artichoke. Aperitif wines are meant to be consumed before meals, not after, so they tend to be drier and lighter. The pomme aperitif is sweeter and a bit more full-bodied than one might expect, but it’s not cloying or heavy. Rather, it has a subtly hearty quality with a faint herbiness that feels very appropriate for fall—especially when served

COURTESY CAMBIO

E.E. BERGER

COURTESY LEATHERBEE

Drinks

hardly refined.) I tried adding lemon to see if that would bring out its fl avor, but the lemon quickly flattened the wine’s overall depth. It mixes well with soda water or tonic for a spritz (bitters optional— though an orange one would be nice). I quite liked it with tonic (especially elderflower tonic) and Sweet Gwendoline gin, too. (Sweet Gwendoline is an atypical gin with a less floral, more spicy flavor.) Combined with the aperitif and tonic, it was like drinking a slice of very sophisticated apple pie. —MICCO CAPORALE

Agora Market, Olivia’s Market, Maison Pasquale, and 57th Street Wines

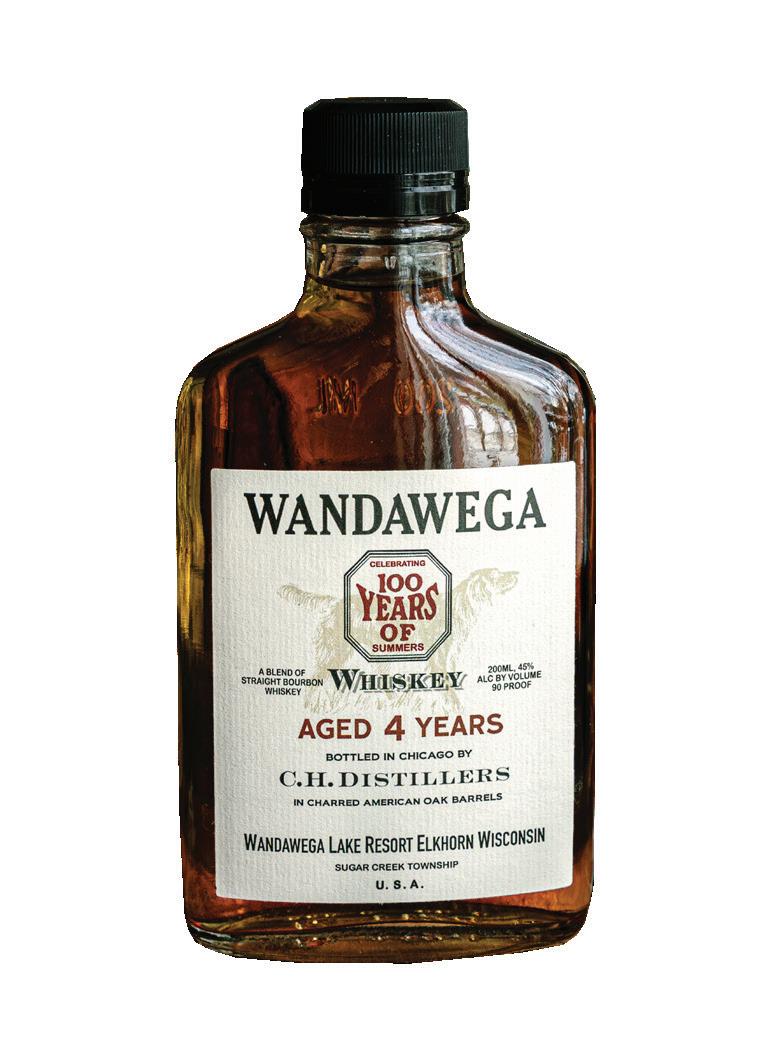

Wandawega whiskey

Elkhorn, Wisconsin’s meticulously restored erstwhile “house of ill repute,” Latvian church camp, and potential Wes Anderson film set introduced this cutesy ass pocket filled with four-to-six-year-old bourbon; it’s meant to

commemorate the glass pints that, as the story goes, Wandawega’s Madame Anna Peck hid from the Feds in her piano. It’s a blend of juice from Indiana’s mega-industrial MGP distillery, and Owensboro, Kentucky’s historic 140-yearold Green River Distilling Co. It’s aged partly in Owensboro and partly in Pilsen at CH Distillery, where it’s also blended and bottled. Yes, it’s a bit of a prop. You can pull it out of your knickers and knock it back like you’re one of those snacky Wandawega models. But with a high corn mash bill, it has a smooth, creamy texture and honeyed caramel notes, and I’d be just as chu ed to —MIKE SULA $10 at the camp store or Chicago Foxtrot Markets v

m mcaporale@chicagoreader.com

m msula@chicagoreader.com

COURTESY CAMP WANDAWEGA

Drinks

FEATURE

A tale of two w mwoods

Exploring the intersecting histories of absinthe and Malört—and why Chicagoans prefer the latter

By MICCO CAPORALE

Chicagoans are bitter. We’re other things, too: brave, resourceful, imaginative, animated—but we’re bitter as hell. Maybe it’s the winters. They’re not as bad as those in other midwestern cities, but ours have the added chill of the wind whipping o the lakefront. It makes us so uniquely bitter we act entitled to parking spots in perpetuity after heavy snow. (You cannot convince me dibs isn’t colonizer energy, but that’s a di erent article.)

Maybe we’re bitter because our city is treated as the lesser sister of Los Angeles or New York. Our rising stars relocate when they decide the city’s too small for their shine, and media misrepresentation of Chicago is so common Vulture even ran a story called “Why does Netflix hate Chicago?” We all know how ideas of Chicago in the national imagination get manipulated to justify political cruelty that impacts us daily. There are a million reasons why we’re bitter—but there’s something about that cultural identity of the wounded underdog that makes us delight in selfflagellating with one of the most bitter spirits of all: Jeppson’s Malört.

Jeppson’s is made from macerating wormwood in a grain neutral spirit. That’s where the liqueur gets its name: “Malört” is Swedish for “wormwood.” But there’s another famous liqueur made in a similar way that’s also a translation of wormwood: absinthe, which comes from the French word. It shares the same Latin root as the plant’s scientific name: Artemisia absinthium . But whereas Malört slowly— slowly —went from a niche spirit to a Chicago icon stocked at every bar in town, absinthe’s never had a huge footprint here. It makes sense that something homegrown would take on more cultural significance, but the virtual absence of Malört’s French cousin in Chicago reveals just as much about the city as the Swedish beverage’s ability to thrive.

Wormwood has a rich countercultural history. It’s been favored in esoteric traditions throughout the world for centuries, and it’s been a staple in folk medicine since before the Bible, too. References to wormwood have been found in ancient medicinal texts in places such

as present-day China, Greece, and Egypt. Both Malört—the trademarked name of one immigrant’s bësk recipe—and absinthe started as folk medicinal drinks for digestive issues. The former, which is a flexible family of wormwood-based spirits, originated in Sweden in the 1400s and the latter in Switzerland in the 1700s. (Interestingly, “bësk” can mean “bitter” or “caustic.”)

Unlike absinthe, bësk has never been banned, in the United States or elsewhere. Switzerland first banned absinthe in 1910, and by 1915, it was forbidden in most of western Europe and the United States. Prohibition began in 1920, but Swedish immigrant Carl Jeppsen, Malört’s founder, was able to skirt prohibition laws by selling bësk as a cure for stomach parasites. Absinthe did not become legal again in the United States until 2007. There are a lot of reasons why absinthe was singled out as more dangerous than other alcohol. Most of it comes down to white supremacy and anti-Semitism. Absinthe was commercialized in the early 1800s using a recipe that began with fermented or distilled grapes, but in the 1860s, a pest infestation and a lot of mildew ruined vineyards throughout France and other parts of Europe (historians call this the “French Wine Blight”). Winemakers were fucked, but absinthe makers could pivot to a beetroot-based spirit and continue.

Until the 1860s, absinthe hadn’t been especially popular in France. It was a drink mostly known among soldiers returning from Algeria, who were served it while colonizing northern Africa—supposedly to break fevers, prevent dysentery, and ward o insects. When they came back, they brought their appetite for “une verte” with them, which some civilians adopted as a shared symbol of empire. At first, absinthe was largely a middle- and upper-class indulgence, but absinthe is very high proof (45 to 75 percent ABV to wine’s 5 to 20 percent). People—especially poets and artists, who were quick to memorialize the unusual green drink in their work—soon realized their francs bought a lot more buzz with absinthe than wine. When the wine supply fell apart, absinthe had a captive audience.

About the same time, in 1867, a man named Valentin Magnan was appointed physicianin-chief at France’s primary mental asylum. E ectively, he became the state’s o cial authority on mental illness. France was a culture in decline, he thought, one corrupted by decadence and disorder. Like many nationalists, he believed in a “French race,” and it was being “degenerated.” Despite many studies to the contrary, he repeatedly blamed absinthe as a culprit. For years, he published a lot of pseudoscience on “absinthism,” a form of alcoholism he believed was separate and more sinister. Hardly anyone in the scientific community agreed with him—but winemakers did.

of deficiency. (Unsurprisingly, today’s French wine lobby loves funneling itself through the far right.)

Winemakers were thrilled with Magnan’s “research” touting absinthe as the drink of degenerates. They used it in anti-absinthe marketing campaigns that emphasized how healthy and patriotic wine is. (Magnan frequently discharged alcoholics from his asylum with a prescription to “only drink wine.”) The wine lobby’s campaigns also exploited a growing wave of anti-Semitism—so much so, some absinthe makers began to advertise they were not Jewish.

absinthe in France was owned by a French Revolution. Prior,

Near the end of the century, winemakers were bouncing back from the wine blight and wanted to regain their market share. At its peak, absinthe never accounted for more than 3 percent of all alcohol consumed in France, but the mere impression of its popularity o ended winemakers. The oldest and most popular absinthe in France was Pernod, which was owned by a nouveau-riche Jewish family who had little political influence. Most winemakers had bought their vineyards at auction during the French Revolution. Prior, the vineyards had primarily belonged to the church. Postrevolution winemakers still wanted to command high prices for France’s best wines, so they needed a performatively democratic marketing strategy: Expensive wine isn’t for wealthy people—it’s for healthy people . . . who are patriots! Wealth just happens to be an inevitable reward for good health and patriotism, and lack of wealth is a symptom

Concern about absinthe wasn’t entirely unwarranted. People who drank an awful lot of it on a regular basis did seem to act, well, chaotically and dangerously—much more so than your average drunk. Magnan blamed this on thujone, a chemical found in wormwood that, in high doses, can produce psychedelic peak, absinthe never accounted

Mephisto, 1914

effects and psychotic behavior. Contemporary scientists have a different perspective, not only from analyzing the thujone levels in pre-ban absinthes (they’re about the same as today’s legal limit), but also looking at the era’s sociopolitical factors.

Alcohol production was not regulated at the time, so it’s likely that the cheapest absinthes contained

Who was most likely to consume cheap absinthe? Poor people. Of course they were the ones most often seen behaving erratically on absinthe. If absinthe was causing moral, cultural, and health decay, it was because too many distillers were making unsafe choices to turn a profit—not because absinthe was popularized by a Jewish family or consumed by the working class.

All of this is clear in hindsight, but it was less obvious at the time. In 1905, antiabsinthe hysteria reached its zenith with a case press deemed the “absinthe murders.” Over the course of a day, a French laborer in Switzerland got very drunk on two ounces of absinthe, as well as wine and at least three

other liquors, then murdered his pregnant wife and children and attempted suicide. He survived and was arrested, but his second try, in his jail cell, three days after his trial, was successful. It was a salacious tragedy perfect for international notoriety, which the growing temperance movement used to their advantage. In 1910 Switzerland became the first European country to ban absinthe. Several other western countries followed suit, and bans remained in e ect well into the 2000s.

Malört started coming into vogue in Chicago about the same time absinthe was re-legalized. Single bottles sat on dive bar shelves collecting dust like forgotten cultural memories. It had some cache in Swedish, Polish, and Mexican communities, but mostly no one cared. Then Sam Mechling, a former bouncer at a wine bar where a coworker first dared him to try it, started giving shots to unsuspecting people. He loved witnessing their reactions—so much so, he started Facebook and Twitter accounts documenting their faces with added commentary like, “It tastes like the day dad left.” By 2012, he was hosting Malört events and selling Malört T-shirts at the now-defunct bar Paddy Long’s. His e orts became so renowned that they caught the attention of the company’s then owner, Pat Gabelick, who showed up to the bar with a lawyer prepared to confront him. Instead, she o ered him a job. That same year, small local startup distillery Letherbee debuted its absinthe. Letherbee started in 2011 after founder Brent Engel’s homemade moonshine grew a cult following from being sold at shows. He started with gin but quickly set his sights on absinthe.

“The process of making it is essentially the same,” he explains. “It’s just a di erent set of herbs, a di erent recipe.”

Engel had been working at Lula Cafe since 2009 and was inspired by a pastry chef making fennel-and-anise shortbread cookies. In addition to wormwood, true absinthe must contain fennel and anise, so the cookies got Engel thinking about using vanilla to temper wormwood’s bitterness. “I really saw an opportunity to make an absinthe aged in American oak,” he says. “The vanilla flavors from the oak work

beautifully.” It gives an American twist to the historically Swiss distillation process—and in 2012, it wasn’t hard to convince people to try it.

“During those years the repopularization of the Prohibition-era cocktail bar [put] a lot of more esoteric spirits back on the radar,” he says. “People were more adventurous. Good food was really sweeping the nation. The farm-to-table concept was taking o . Chicago was in the middle of all these trends that made people more passionate about food and drink. People would go out for dinner and drink three or four cocktails. Now people might have one before dinner. I think people drinking less is probably good. But the drinking culture is nowhere close to where it was ten years ago.”

Drinking absinthe isn’t exactly a casual experience today. Because of its high proof, it’s recommended to drink absinthe in a ratio of roughly one part alcohol to three-to-five parts water (the colder, the better). When water mixes with the liqueur, it opens up the drink’s flavors while releasing the oils in the anise, causing a clouding e ect known as the “louche”—a word that is also French slang for a person of questionable character. People took to placing a sugar cube atop a flat spoon before adding water so it would balance absinthe’s bitterness.

Cafe culture thrived in the Belle Époque, and absinthe was ubiquitous enough for even the most lowbrow establishments to provide things like absinthe fountains and spoons. Engel recalls Chicago bars going through a brief romance with absinthe and investing in fountains or drippers, but enthusiasm quickly evaporated. Today many cocktail bars list one absinthe on their menu (the one they’re making Sazeracs and Last Words with), but it’s never clear whether they’re equipped to properly serve it. NOLA-inspired restaurant Ina Mae Tavern advertises a table-side absinthe drip using a fountain but only o ers two behind the bar. To my knowledge, there are only two places in Chicago with absinthe menus and appropriate accoutrement: the upscale French steakhouse La Grande Boucherie and the rock ’n’ roll bar Delilah’s.

“When absinthe became available in Chicago, I thought a lot more people were going to be fired up to pursue it,” owner Mike Miller says. Miller has been o ering a rotating menu of 15–20 absinthes since it was legalized. He’d long been fascinated by its romantic association with artists, then fell in love with the drink after trying several absinthes on a trip to Europe in the 90s. But he thinks absinthe works for Delilah’s because the bar’s focus has

Drinks

always been finished products—that is, spirits for spirits’ sake, not alcohol combinations.

“I think one of the things that makes Chicago so world-class is that we have people who nerd out about the most interesting stu ,” he says. “The most boutique producers will get their hands on something and really teach other people about it. We have world-class stu made right here in Illinois.”

Letherbee isn’t the only local brand that makes absinthe. North Shore, Star Union, and Dead Drop do, too. Absinthe isn’t a focal point of many American bars, but small producers across the country have been enthusiastically trying their hand at the liqueur. (One of last year’s buzziest in the online absinthe community—Supérieure Isabella—is made in Detroit, but it has yet to receive regional distribution.) Engel believes smaller distilleries do a lot of the research and development for hospitality trends, but he’s hesitant to think absinthe will ever take o on its own in Chicago. Lower alcohol consumption coupled with higher real estate prices make it hard for bars or restaurants to stay open long enough to cultivate a serious niche. Plus, do Chicagoans really have the appetite for something so esoteric and dreamy?

“Midwestern people are pretty, like, pragmatic—no bullshit,” he says. “The marketing for absinthe is typically super romantic and fantastical. I don’t know if that vibe fits in a town like Chicago, which is a little more rooted in, like, labor unions and slaughtering animals.” To him, Malört’s popularity makes sense—though despite making his own bësk since 2013 (which was originally marketed as R. Franklin’s Original Recipe Malört until he was forced to change the name), Engel doesn’t entirely share locals’ enthusiasm.

“You drink it to punish yourself or your friend, or to initiate someone who’s never been to Chicago,” he says. “It’s intentionally unpleasant—like an S&M sort of thing. If you enjoy it, you’re a masochist, and if you like feeding it to other people, you’re a sadist. I get that it can be fun sometimes, but I’m not into that sort of punishment. If I’m gonna spend money on something, I want to enjoy it.”

Maybe Chicagoans don’t believe they deserve nice things. Perhaps Chicagoans just enjoy being bitter. Miller’s noticed that absinthe attracts seekers; even if it never gets popular, people who are really into it manage to find their way to each other by following their curiosity. For everyone else, there’s another wormwood liqueur that reigns supreme. v

NEWS & POLITICS

Chicago tenants demand eviction moratorium

Housing organizers warn against putting people out of their homes “as long as I.C.E. is in our city.”

By DEVYN-MARSHALL BROWN (DMB)

As federal agents continue to arrive unheralded and uninvited to local day cares, airports, hardware stores, and more, some Chicago tenants are calling for an eviction moratorium, warning of increased risks that come with being evicted amid ramped-up immigration enforcement. People are afraid to go to work, and it’s impacting their income.

On October 18, the All-Chicago Tenant Alliance called on Governor J.B. Pritzker and Mayor Brandon Johnson to halt evictions for “as long as I.C.E. [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] is in our city.” Other tenant unions and labor organizations have since joined the campaign.

“We were formed because we believe people

should get to safely stay in their communities of origin, the places where they are choosing to live, where they’ve built lives and families and safety,” says Tory deMartelly, a founding member of the Belden Sawyer Tenant Association (BSTA). “There’s also so many tragic stories of people’s breadwinning family members who have been abducted. They don’t deserve to be evicted right now; it is unsafe for them. They deserve to stay in their homes.”

BSTA has been circulating a petition to send to Pritzker. Organizers have also requested

meetings with the governor and mayor.

Miguel Alvelo Rivera, executive director of the Latino Union of Chicago, says several workers, regardless of their immigration status, have reported feeling concerned about their personal safety. The Latino Union, which has joined the call for an eviction moratorium, uses education, advocacy, and coalition-building to organize domestic workers and day laborers, who have been targeted indiscriminately by federal agents simply because of how they look and where they work.

“Some people have opted to stay away from work, [particularly] those who have a little bit more community support from others,” Rivera says. This is especially common among day laborers, who are experiencing daily deportation raids at hiring sites around the city. Corner hiring sites are known intersections where both working people go out of economic necessity to sell their labor for the day, and where employers go to find and negotiate day labor. Many of these corner hiring sites happen

to be outside Home Depots.

In Rivera’s neighborhood, Albany Park, one of Chicago’s working-class and migrant communities, streets that are usually filled with life are now empty. “I have also spoken with several business owners, from restaurants to the local laundry spot. They have been telling me business is rough because people don’t want to risk being outside,” Rivera says.

The governor has the authority to declare an eviction moratorium, which would temporarily suspend the eviction process or prohibit a landlord from beginning the eviction process due to nonpayment of rent. The most recent moratorium in Illinois happened during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. It began in March 2020 and lasted 17 months.

The Los Angeles Tenants Union has also been building momentum to enact a countywide eviction moratorium in response to ICE raids.

Mayor Johnson’s and Governor Pritzker’s offices did not respond to requests for comment by press time, but local tenant organizers say they aim to get an eviction moratorium in place “yesterday.”

“The more we build these conversations, the better,” deMartelly says. “But this is an urgent demand.” v

Some Chicago tenants are calling for an eviction moratorium. SHIRA FRIEDMAN-PARKS The most recent eviction moratorium

Federal invasion continues

President Donald Trump ’s assault on Chicago—and residents’ defiant response to it—drags on more than two months after the launch of so-called “Operation Midway Blitz.”

On November 9, Border Patrol commander Greg Bovino and a caravan of masked soldiers ravaged Little Village, Cicero, and Oak Park. Federal agents tossed chemical munitions into crowds of residents who’d gathered along the bustling 26th Street commercial corridor. A family, including a one-year-old girl, was on a trip to Sam’s Club when federal agents showered them with pepper spray through an open car window. And two sisters—a 14-year-old and an 18-year-old—were reportedly detained when they stepped in to protect their mother, who’s undergoing cancer treatment, from immigration o cials. (The sisters were taken to the Federal Bureau of Investigation ’s field o ce, where they were allegedly held for hours without contact, then released without charges.) Earlier in the week, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents forced their way into a North Center preschool and abducted a teacher as traumatized children, parents, and coworkers looked on.

All of that is possible thanks to the tacit support of local police. ICE’s detention center in suburban Broadview has been transformed

four union sta members without severance. The members—who represent a quarter of the union formed just four months earlier—were told their last day would be October 17. (In the summer, before UWU was certified, management laid o another unit member, one of UPLC’s oldest employees, without severance.)

On September 22, less than two weeks before the most recent layo s, UPLC management told the UWU they would be laying off four workers due to a budgetary crisis. That came as a surprise to union members, who say they’d been told earlier in the month that the organization was stable and the executive director was “conservatively predicting future funding.”

press release, their “management is straying from the organization’s core values” in recent years.

The layoffs have impacted not just the livelihoods of the four members but also the many clients who lost their legal advocates, says bargaining unit member Sofia Cabrera. “Our whole goal with unionizing is to protect our community, which includes sta and our clients . . . so that sta could have a say in how UPLC grows and continues to serve Uptown and people in [the Illinois Department of Corrections].”

into a quasi-fortress guarded by Illinois State Police and Cook County Sheri ’s police. Protest is banned near the sole working entrance to the facility, the sidewalk cordoned o with concrete barricades. On November 7, police arrested 14 suburban moms for the crime of sitting peacefully in a street that’s been closed to vehicle tra c for weeks.

The Chicago Police Department (CPD) detained at least three Little Village residents who’d come out to oppose federal agents on November 9. At one point, according to multiple videos I reviewed, CPD officers even formed a perimeter around Bovino to push community members back while he made an arrest.

—SHAWN MULCAHY

Layoffs and labor stife

The union, which is a liated with the O ce and Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU) Local 39, attempted to negotiate with management on severance pay and benefits for laid-o sta and workloads for the remaining sta members—who are now taking on at least 25 additional community cases. In return, management indicated no intention to meaningfully bargain and denied “critical information needed for union members to understand the crisis,” the union stated in a press release.

UWU is raising funds to help cushion the financial impact on the four members, who are also set to lose insurance coverage by the end of the year: gofund.me/e94d1aa54 —SAVANNAH RAY HUGUELEY

Proof is in the (budget) pudding

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s 2026 budget proposal includes a 43 percent reduction in domestic violence spending, according to WBEZ. The cuts jeopardize crucial services, like rapid rehousing for survivors of gender-based violence, at a time when the federal government is slashing public assistance.

WBEZ reports city funding for domestic violence services would shrink from $21 million to $12 million under Johnson’s latest proposal, due largely to a limited pot of federal pandemic relief money that has since run dry. Yet, Johnson had no trouble finding more money to put toward the already gargantuan amount the city spends on policing each year. The mayor’s proposal would add $38 million—more than enough to bridge the domestic violence funding gap—to the CPD’s 2026 budget, bringing the department’s total allowance to a whopping $2.1 billion.

The Uptown Workers Union (UWU) is accusing its employer, the Uptown People’s Law Center (UPLC), of violating federal labor law by failing to bargain over recent layo s.

The union filed unfair labor practice charges with the National Labor Relations Board on November 3. The charges came exactly a month after the community law firm laid off

UPLC management has been represented by notorious corporate law firm Jones Day, whose lawyers provide “union avoidance” services (and helped Trump try to overturn an election). The bargaining team is still trying to discuss severance, rehiring terms, and workloads, and has yet to begin contract negotiations. UPLC’s advocates have defended the struggle of poor and working-class Chicagoans for over 40 years; yet, according to UWU’s

Notably, Johnson’s budget proposal includes funding for almost one thousand unfilled CPD positions, despite calls from community groups to redirect some of that money to policing alternatives, such as youth employment, nonpolice responders, and public mental health centers. —SHAWN MULCAHY v

Make It Make Sense is a weekly column about what’s happening and why it matters.

m smulcahy@chicagoreader.com

An anti-ICE rally outside the FBI fi eld offi ce on November 9, 2025 PAUL GOYETTE/FLICKR VIA CC BY 4.0

Members of Uptown Workers’ Union UWU

Drinks

How immigrants shaped Chicago’s bar scene

The city’s drinking culture was forged in immigrant-owned, 19th-century saloons and taverns.

By TARA MOBASHER

Liz Garibay’s first sip of alcohol was horrific. “It’s funny to look back on,” said Garibay, who is now the founder and executive director of the Beer Culture Center in Chicago.

But soon, she found herself going to bars alone to study, read, watch a game, or have dinner. “Going to these spaces made me realize how important those bars were to creating community and the value in being a regular at a bar,” she said. “For Chicago, it’s part of our heritage.”

Chicago became a hub for beer brewing in the 19th century. By 1900, the city had around 60 breweries, thanks to an influx of German and Irish immigrants who brought with them lighter, more carbonated lagers.

From the popular (but often-avoided) Malört to the vibrant social atmosphere of bustling pubs and taverns, immigrants integrated deep into the fabric of the city.

Garibay said new arrivals to the city were largely drawn to these spaces because of the sense of community they found. “They want to be in spaces where other people speak their language, wear their clothes, understand their cultural background,” Garibay said.

One of the reasons so many taverns were owned by immigrants, Garibay said, was that liquor licenses were easier to obtain in Chicago compared to other cities. “You can just find four walls and do your thing,” Garibay said. European immigrants in need of work often obtained a tavern license to provide for themselves and their families. Incidentally,

Immigrants’ influence on Chicago is ever-present in the alcohol we drink, the food we eat, the music we listen to, and the books we read.

they also found new social and cultural circles. “Human beings naturally gravitate and want to be with people who are like them,” Garibay said. “They’re coming straight from di erent parts of Europe or di erent parts of the world.”

The new communities, Garibay said, often used taverns as spaces to socialize, relax, and sometimes network. They spoke similar languages, bonded over traditional food and music, and discussed news from back home.

Michael Roper, current owner of Hopleaf Bar in Andersonville, notes how types of alcohol and traditions followed communities wherever they settled.

He bought the bar in 1992 from Swedish immigrant Hans Gotling. Gotling became wellknown for making and selling Swedish glögg, a mulled wine that is particularly popular during the holidays. It was so beloved that people would drive from 50 or 60 miles away for it.

Roper said the unlicensed production and sale of the wine was illegal, but because Gotling was a Democratic precinct captain at the time, he was largely safe from punishment. After he sold the bar, Gotling also sold the glögg recipe to a Minneapolis distiller. “Frankly, it was never the same if he didn’t make it himself,” Roper said. “It wasn’t as good.”

Immigrants’ involvement in the Chicago alcohol industry can even be traced back to the city’s first riot in 1855. The Lager Beer Riot began when anti-immigrant mayor Levi Boone targeted the predominantly immigrant-owned bars. He enforced an ordinance mandating taverns be closed on Sundays and raised the cost of liquor licenses from $50 to $300 per year.

The move was not met well by German immigrants, who worked six days per week, allowing themselves Sundays to socialize—typically at local taverns. They fought around the downtown area for immigrant rights, politics, and beer. The City Council ultimately agreed

Grandma’s Saloon, 211 E. 22nd, in 1906

of a bar at 29th and Federal in the 1910s

to lower the fee, dropping it from $300 to $100. It also voted against releasing those who were jailed for not paying the fine.

But drinking was still preserved as a common aspect of European and Chicago culture. “Most of the immigrants of the 20th century in the United States came from places where alcohol was part of their national culture,” Roper said.

Those traditions also furthered anti-immigrant sentiment against Irish and German communities across the country in the mid-19th century, perpetuating stereotypes that they were drunks and criminals.

Now, neighborhoods like Andersonville, which was once majoritySwedish, have changed as new communities moved in. “The few Swedes left are pretty old, and most of the Swedish businesses in the neighborhood have disappeared. It’s a more mixed neighborhood now,” Roper said.

“More Hispanics, more people from the Middle East. But ethnically, it still retains some of the identity of being a Swedish immigrant neighborhood.”

Even still, immigrants’ influence on Chicago is ever-present in the alcohol we drink, the food we eat, the music we listen to, and the books we read. “Immigrants have not only shaped Chicago,” Garibay said, “but they shaped the way we drink [and] taught us how fighting for something you believe in can cause significant positive change, be a catalyst for change, and can influence the way you actually look at life.” v

m letters@chicagoreader.com

ARTS & CULTURE

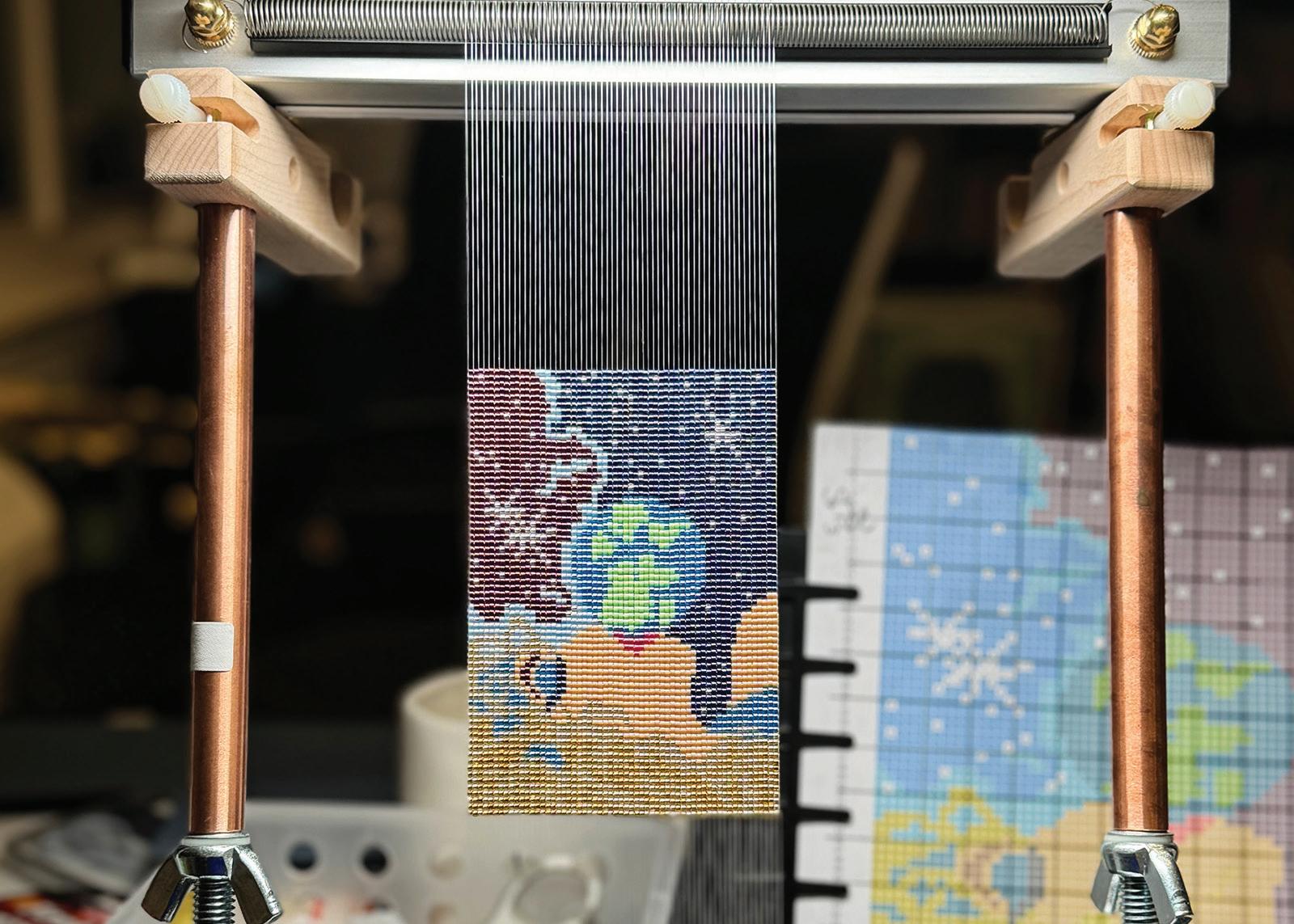

CRAFT WORK

‘ S ee ing the world in bead color’

Yuliya Klochan’s beading practice taps into her Ukrainian roots.

By RUBY ROSENTHAL

A work in progress on the artist’s loom COURTESY THE ARTIST

Two years ago, beading artist Yuliya Klochan was a prolific writer, armed with a newly minted master’s from Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism. At the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy, she was up for a promotion to senior communications manager: a shiny new title for a shiny new stage of life.

This was it, right? She’d made it. But then she realized she couldn’t stay awake during half the day she was supposed to be working. She learned she has a chronic sleep disorder, and that it would be impossible to work a traditional nine-to-five. So she grieved. And she created new traditions, including a beading practice, tapping into her Ukrainian roots.

Then one afternoon earlier this year, Klochan was strolling around “That’s What She Said,” an exhibition of women’s art at Jackson Junge Gallery in Wicker Park. Hanging on the walls, she saw crushed eggshells and dried roots in Conversations With My Mother by Doina Mihaela Iacob, robin eggs captive in a gumball machine, and a bird perched pen-

pants, Klochan tells me that before she emigrated from Ukraine at age 14, she learned loom beading in a class called “labor,” which is equivalent to home ec in the U.S. Boys and girls are separated; boys make wooden stools, and girls sew skirts and learn how to cook. Fun?

“Nobody was into this class,” Klochan remembers.

So Klochan began by cross-stitching reproductions, purchasing patterns she found on Etsy made by other Ukrainians. Then, in July 2023, she began beading. A little over a year in, the owner at Artem in Evanston—the first gallery to accept her framed beaded art and allow her to bring whatever she wanted—told Klochan she should raise her prices.

Now, her work hangs at Jackson Junge, Andersonville Galleria, Chicago Fine Art Salon. And You’d Look Prettier If You Smiled More is sold out on her website.

sively outside in the sculpture Anybody Got a Quarter? by Deana Bada Maloney. It was complex, political, moving. But she certainly couldn’t create something like that, she told her husband. “Why not?” he asked.

Klochan now hunches over a loom for hours, her cats Clunk and Strawberry afoot, creating beadwork about a world she wishes existed. That world has equal rights, LGBTQ+ pride. It’s without men chastising women to smile, like in her 2,560-bead piece of an orange-haired woman. Her eyes are closed, mascara dripping down her face while she applies garnetcolored lipstick to barely upturned lips, called You’d Look Prettier If You Smiled More—it’s the first piece she created that really felt like “her.” Could this be it?

Klochan is 29 years old. She has shoulder-length bouncy red curls, brown eyes transforming into half-moons when she smiles, and a soft laugh. Midway through our interview, she pops open her fridge door (a mosaic of pig-themed magnets from around the world) and hands me a fuchsia can of Bubly seltzer. As I wipe condensation on my

It’s an experience she describes as “seeing the world in bead color.”

“I started because I wanted a hobby,” Klochan says. “As an adult, I’ve never had a chill, nonmoney-producing, nonside-hustle hobby.”

That didn’t exactly go as planned. Her first beading reproductions were van Gogh’s Starry Night , the CTA el map, and Munch’s The Scream . Then, the originals: portrayals of queer love, nonbinary and Ukrainian American pride, and subversions of myths; women’s issues, like Pro-Choice , depicting a partially nude woman with flowers covering her vagina, or Double the Hours of Housework Per Week , where a woman waves her right hand as she holds a baby in her left, one foot in the o ce, one foot at home.

Artist Yuliya Klochan’s labor-intensive bead works take hours to create.

Though she now makes art with a four-inch needle instead of a pen, Klochan still uses her writer’s brain when creating characters in her beadwork, using color to develop their personalities. Sitting atop her desk is a small plastic chest of drawers filled with Toho Aiko beads, labeled by color combinations: red, pink, and orange; green, purple, and brown; colors making up the Ukrainian flag. She used an iridescent white, for example, in Magic Wand , where a woman donning a black-andwhite leotard directs a wand toward a splatter of silvery gray, using the shimmering white and her shiniest black beads to highlight playfulness. Its background is also a particular blue—a matte, washed-out cobalt to make it look like a vintage pinup model poster. She also maintains an entire box of white beads and a whole box of brown, to get hair just right. But what really matters to Klochan is when what she’s made resonates with people.

And sometimes, she’ll spy a brief instance of beauty—like in A Sunset Moment, where a couple wearing fluorescent pink shorts capture a smartphone photo of the sun slinking into peach-colored clouds—snap her own discreet photograph, and later use it as inspiration.

“A Ukrainian family noticed my piece Ukrainian-American , which describes the struggle of having two worlds,” Klochan says. “There was a little kid, maybe like five years old, and his mom said to him, ‘This is you.’ It was just so powerful to me—that it was applicable to such a wide range [of experiences] even though it was a personal piece.” I think she’s found it. I think this is it. v

m letters@chicagoreader.com

ARTS & CULTURE

EXHIBITIONS

RAn exhibition worth revisiting Temitayo Ogunbiyi’s poetic approaches to geography.

Tracing a journey from Lagos, Nigeria, to Chicago, Temitayo Ogunbiyi’s “You will have revelations along felled branches and longer roots/routes” at the Arts Club of Chicago is a pursuit into the ecological life found within each environment. Attuned to the healing properties of botanical forms native to either region, the transnational exchange results in a series of drawings, paintings, and sculptures that stand out for their quiet but steady captivation.

The exhibition, which forms one position of the artist’s spate of public programming this fall, relies mischievously on viewer engagement to accentuate its full potential. Utilizing vintage furniture as display and storage containers, Ogunbiyi’s installation, You will find new framings in cra s of old, is placed within closed drawers and, sometimes, underneath the furnishings themselves. To access them, viewers are invited to interact carefully, a process that only helps to pull attention to the intricate detail of Ogunbiyi’s botanical studies, mixed media on herbarium paper that are reminiscent of early scientific illustrations.

In aesthetic contrast, a vast array of paintings, almost all created from varnished Japanese ink and acrylic on found fabric, enlarge and enliven the flora tucked away. Pale hues offer so depictions of plant life, while sculptural works inside and outside the gallery shimmer with cultural and material vibrancy.

Positioned across linguistic, formal, and conceptual assemblages, Ogunbiyi creates a network of meaning filtered through poetic approaches to geography. There is, invariably, no way to glean all the rich knowledge on display. But perhaps this is best: an invitation to return to the venue and (re)learn about relationships unfamiliar, connections that can only blossom and grow with time, as the artist intended. —LUCAS GÓMEZ-DOYLE “You will have revelations along felled branches and longer roots/routes” Through 12/19: Tue–Fri 11 AM–6 PM, Sat 11 AM–3 PM, Arts Club of Chicago, 201 E. Ontario, artsclubchicago.org/exhibit/4967

RThe

future is here

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Diane Simpson builds herself into the heart of the city.

In her 90th year, Diane Simpson, a Chicago legend, presents work inspired by time. With a decades-long practice in the fields of art, design, and architecture, Simpson’s cra is a tour de force, demonstrating the multiplicity of creation, form, and perspective.

For the first time in her career, Simpson’s sculptural works are shown outside, gracing the Bluhm Family Terrace at the Art Institute of Chicago. Rendered from preparatory sketches developed in the 1980s, on which the artist had inscribed “Good for Future,” the three newly commissioned sculptures on view come to life. With the future now here, Simpson has materialized the past; the works are a testament to patience, a celebration of longevity, and a reminder that dreaming builds far more durable foundations than the unstable base of immediate impulses.

Set against a portion of the Chicago skyline and overlooking the Lurie Garden, the sculptures are geometric siblings to their surrounding urban environment. Each work, fabricated from medium-density fibreboard and painted with acrylic, is a semi-optical illusion, a product of Simpson’s translational style between twoand three-dimensional space, resulting in a perspectival flattening of the objects. To break from this transfixing spell requires viewers to shi around the site, in turn activating the works, which are animated by a play between light, form, and color. From some angles, the shapes look joyfully animalistic, while in other sight lines they more closely resemble miniature sci-fiesque constructs.

In either case, the result is wonderfully interactive— outcomes achieved only through the complementary coexistence of objects, people, and space. Surrounded by the bustle and cacophony of city sounds, Simpson has built herself into the heart of Chicago. —LUCAS GÓMEZ-DOYLE “DIANE SIMPSON: ‘GOOD FOR FUTURE’” Through 4/19/26: Fri–Mon and Wed 11 AM–5 PM, Thu 11 AM–8 PM, Art Institute of Chicago, 111 S. Michigan, artic.edu/exhibitions/10630/dianesimpson-good-for-future, adults $20–32, seniors 65+, students, and teens 14–17 $14–26, children under 14 and Chicago teens 14–17 free v

EXPLORE HOLIDAY ITINERARIES, EVENTS, DEALS AND MORE AT

A Musical Adaptation of William Shakespeare’s As You Like It

Adapted by Shaina Taub and Laurie Woolery

Music and Lyrics by Shaina Taub

Directed by Braden Abraham

Music Direction by Michael Mahler

Choreography by Erin Kilmurray

Top: Temitayo Ogunbiyi, Arts Club of Chicago; Diane Simpson, Art Institute of Chicago

TOP: MICHAEL TROPEA; COURTESY THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO

Drinks

Belly up to the theater

Drinking shows can be fun but require ground rules and common sense.

By KERRY REID

Drinking and theater have always gone together, from the winesoaked festivals of Dionysus in ancient Greece to the boisterous ale-enhanced behavior of the groundlings during Shakespeare’s plays at the Globe Theatre. Plays set in bars have also stood tall (or staggered) throughout the modern canon, from Eugene O’Neill’s epic The Iceman Cometh (which Reader critic Tony Adler called “a masterpiece of excess”) to William Saroyan’s The Time of Your Life to Conor McPherson’s The Weir (a collection of ghost stories told by characters in an Irish pub).

The camaraderie of bar culture extends o stage for many actors, though most of the time they save their imbibing for after the show. (John Barrymore of the legendary acting clan being a famous—and tragic—exception.)

But there are shows where actors and audiences are encouraged to enjoy cocktails while the story plays out. Recently, I saw Drunk Dracula at the Lion Theatre downtown (also the home of the long-running Drunk Shakespeare), wherein an actor is selected at the top of the show to down several shots (and may drink more during the performance) and then has to make it through the material. When the artists of Drunk Shakespeare went union a couple of years ago, I asked company member and organizer Diego Salinas how they protect the designated drinker at each show. He told me, “We have robust systems in place to make sure that our drunk actor is taken care of before, during, and after the show. We are all in rotation to make sure everyone’s liver gets a break. And we make sure our actor goes home in an Uber or Lyft or a cab at the end of the night.”

Hitch*Cocktails

have in some way featured alcohol as a component of the action to find out how they walk the line between fun and mayhem, and how they protect the artists and audiences from the consequences of excessive boozing.

Open run, Fri 9:30 PM, Annoyance Theatre, 851 W. Belmont, 773 - 697-9693, theannoyance.com, $22

There’s a drinking game for the audience to play that all is based o things we do or say onstage triggering your drinking, if you would like to participate.” Additionally, there’s a game for the actors. “If an actor o ers another a drink from the onstage bar, the actor must accept that drink and must finish the drink before the scene finishes,” says Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick says that her training in intimacy direction means that she is focused on “consent-forward practices” for performers. Actors can opt out of drinking and be the night’s “designated improviser,” meaning they’ll stay sober and make sure that things don’t get off the rails for either the cast or the audience.

Additionally, notes Fitzpatrick, “We have two shorthand signals—one that’s verbal and one that is physical—that tell the other actors onstage, ‘I’m not OK with what is happening to me right now.’

So it might be that you get served a drink, but you’re like, ‘I’m absolutely not gonna drink this.’ You can use one of those signals, and we know somebody else is gonna swoop in and take that drink from you. Or it might be that you were the designated improviser and somebody accidentally served you an alcoholic drink, and you can use those signals as well.”

and Kerouac and Dorothy Parker.”

The show took shape as an examination of “the connection between creativity and alcohol,” and opened in its first incarnation in fall 2002 with Mosqueda, Benjamin, and fellow Neo-Futurist Diana Slickman at the nowclosed T’s Bar in Andersonville, where, as their website describes it, “We sat at the bar and drank and talked about famous drinkers and writers, our drinking and writing, the e ects of alcohol on the body and mind and family, and we drank . . . more.”

The first show was a hit, leading to further chapters exploring Prohibition-era writers, hangover cures, and even holiday shows (The 12 Steps of Christmas , A Beer Carol ). Along the way, the Drinking & Writing Theater also supported local brewers through the Beerfly Alley Fight competition, featuring craft brewers, art, and food, and moved into film with the Tied House Film Festival, where filmmakers created short films on “the 5 stages of intoxication.”

O cially, Drinking & Writing works under the umbrella of Tied House Productions, which Mosqueda says is both a nod to the history of tied houses in Chicago (saloons owned by brewing companies— Schubas started out as one such establishment) and a way to apply for funding with a name that might be a little less o -putting. But Mosqueda says they don’t shy away from the alcohol-friendly nature of the shows. “If someone is offended or a venue is offended by what we do, then, you know, we move on and drink somewhere else.”

I recently checked in with other shows that

Hitch*Cocktails from High Stakes Productions operates in a somewhat similar fashion to Drunk Shakespeare but is entirely improvised. Bri Fitzpatrick, the intimacy director and culture coordinator for High Stakes, notes that Hitch*Cocktails begins with a suggestion of a fear from the audience. “We want it to be a fear that an audience member believes is unique to them and them alone, and then we improvise a two-act Hitchcockian thriller.

It’s not hard to figure out the focus of the long-running (albeit produced intermittently) show Drinking & Writing . Cocreators Sean Benjamin and Steve Mosqueda met while company members of the Neo-Futurists. As Mosqueda tells it, “After the shows we hung out in bars a lot. We were hanging out at Simon’s one night . . . thinking about doing a show about Charles Bukowski. We were gonna call it Buk on Ice, and it was gonna be a show with ice skating and Charles Bukowski. So that was the first idea. And then as we were doing research, we just learned that there were just too many writers to not involve everybody. You know, we got Hemingway and Fitzgerald

As for blending their own creative processes with booze, Mosqueda says drinking makes it “easier to come up with the ideas. But then again—I mean, this is kind of a cliche now—when drunks write, they write it down and then they wake up the next morning and realize it’s crap. But within that crap, there’s little nuggets that you can pull out of there.”

Mosqueda says that the “writing” part in Drinking & Writing inspires its own fandom, where people will reach out with suggestions. “‘Have you ever read this by Bukowski, or Kerouac?’” Bars even haunt his subconscious:

DRINK: AT THE ARCADE!

Fri–Sat 11/ 14 -11/ 15 7:30 PM, Cornservatory, 4210

N. Lincoln, cornservatory.org, $11-$ 30

Mosqueda’s latest work in development, the musical Miersten Wolf, comes from a dream he had in the pandemic about an encounter with a mysterious woman at a bar. (The company is hoping to open the show mid-February 2026.)

And yes, sometimes there are patrons who take the audience participation and imbibing too far. But Mosqueda notes that the Neo-Futurist training helped them learn how to deal with it. The shows back then ran at 11:30, and Mosqueda says, “People would show up drunk off their ass.” If anyone got out of pocket, Mosqueda says, the cast would “stop in the middle of it and say, ‘Hey, can you stop?’ And nine times outta ten, it would embarrass the hell out of them. And they’d shut up or they’d leave, which is great.”

Corn Productions also has a lot of experience dealing with drunk audiences. After all, they’ve encouraged it for years with their holiday-themed drinking-game sketch productions, like Death Toll: A Halloween Drinking Game Performance , the Christmas-themed Happy Holly-Daze , and the Saint Patrick’s–themed O the Paddy Wagon. Currently, they’re running DRINK: At the Ar-

game.” Lance notes sometimes the game remains consistent throughout the show, and other times the rules change over the course of the performance.

Lance notes that when the shows first started, there would be a “designated drinker” onstage. “The first time I was dubbed the drinker, I realized I should be taking tiny sips far too late and was, uh, quite drunk for the show. Made it through, just barely.” Now, says Lance, the actors mostly avoid drinking, which helps with crowd control.

Another element that helps things go smoothly is that Corn has a designated host for each show, who explains the rules of the game (drink anytime someone sings, for example). A light-up “DRINK” sign reminds people as well, but Lance says that they emphasize that moderation is key. And there is also the all-important “don’t be an asshole” rule. “We basically explain, ‘Hey, the show’s up here; it’s not out there for the next hour and a half. We’re a lot funnier than however funny you think you are.’”

There is also the allimportant “don’t be an asshole” rule.

cade!, built around themes from video games. Though the company doesn’t have a bar onsite, they’ve also long encouraged BYOB for patrons.

Artistic director Justin Oliver Lance (who is married to managing director Deanna DeMay) says that the BYOB aesthetic evolved into the drinking-game shows. “We used to always call it the cheapest date night that you could find in Chicago. We really embraced the idea of having a sketch show where there’s a drinking

Drinks

are not drinking. We’ve had plenty of people who don’t drink come to see the show. It’s an element of the show that people really, really enjoy, but it’s by no means necessary to be able to enjoy the show.”

Even if, like Cassio in Shakespeare’s Othello, you have “poor and unhappy brains for drink-

DeMay says that having an earlier start time than in the past means they’re getting people at the beginning of their night, rather than patrons who are already three sheets by the time they get in the door.

As for the creative process for the sketches, DeMay says, “When people are writing sketches, we’re not telling them to write with any game in mind. We’re like, ‘Here’s the theme of the sketch show. Just write something. We’ll figure out a game.’”

With drinking, however, unpredictable behavior follows. DeMay says that her favorite incident involved an audience member ordering a pizza during the Saint Patrick’s show. The host, Lindsay Bartlett (who performs her duties in character as Bono), managed to shame the patron into giving up a slice or two for interrupting the performance when the (unpaid) delivery arrived. DeMay and Lance also say that, while it’s not commonplace, there are people who don’t know their limits, which is why they emphasize where to find the bathroom at the top of the show.

Everyone I talked to stressed that they want sober audiences to be able to enjoy their shows as well. Fitzpatrick says, “We have had underage folks come to the show before who

ing,” it’s possible to take in these shows with clear eyes—and gain a fresh appreciation for the skills artists need to make the connection between the stage and audience, sober or otherwise. v

m kreid@chicagoreader.com

The audience at Death Toll COURTESY CORN PRODUCTIONS

Drinking & Writing (Steve Mosqueda at far right) COURTESY THE ARTIST

THEATER

OPENING

RThe enchantment of love Writers Theatre’s As You Like It sings the joys of redemption.

In recent times, our greatly imperfect union has seen the eruption of hatred from human to human. At first, As You Like It seems like more of the same: two pairs of brothers—Oliver and Orlando, and Duke Frederick and Duke Senior—each determined to outlast the other by any means necessary. Orlando (Benjamin Mathew), raised in a humble speakeasy by servant Adam (Torrey Hanson) and firm to prove his inborn honor, enters Duke Frederick’s wrestling match. A nasty fight ensues, Orlando prevails—and finds that there is no winning: Like Duke Senior before him, the man is banished. Intolerant of all he imagines opposed to his rule, Duke Frederick (Scott Aiello) decides that his niece, Rosalind (Phoebe González), daughter of Senior and erstwhile companion to his own daughter, Celia (Andrea San Miguel), must also go. But whither ought these fair youths wander? There is but one place: the forest of Arden.

Sophie Haviland in 2000. Director Seph Mozes staged the production at the United Church of Rogers Park (it was the first time Foreman’s work had been performed in Chicago in 30 years). The play is about two gay men trapped in a labyrinth pursuing a Minotaur. The labyrinth

candlestick maker, will be instantly relatable to anyone who’s dealt with the literary world in any way, shape, or form.

The highlight of the entire play is a wordless pantomime of the townsfolk demonstrating in increasingly erotic/ridiculous gestures the techniques by which they scrawl away at their masterpieces.

The joke, of course, is on each and every one of us who has ever tried to make anything at all.

Because even the most cynical, world-weary wretch harbors a tiny flicker of a dream that fools them into continuing the most hopeless pursuits. This one’s funny because it’s true.

—DMITRY SAMAROV A DEVIL COMES TO TOWN Through 12/6: Thu–Sat 8 PM; Trap Door Theatre, 1655 W. Cortland, 773-3840494, trapdoortheatre.com, $22

Elegy for broken children

The 4th Graders Present an Unnamed Love-Suicide looks at the horrors of prepubescence.

If you know kids, you know that everything they think and feel lives close to the surface.

“Johnny wrote this before he shot himself,” a boy mutters into a microphone at the beginning of a school assembly. Johnny’s play is a theatrical suicide note, loaded with the dead boy’s observations of his class’s social dynamics and dramatizations of his own regrets. Johnny was clearly preoccupied with the nature of goodness, the ways he hurts his “girlfriend,” Rachel (Charlee Amacher, heartbreaking), and how his peers (including a terrifying Quinn Leary as a sociopathic bully) hurt him, leaving him to ask if there’s any good le at all.

Writers Theatre’s production of the musical adaptation of Shakespeare’s play by Shaina Taub and Laurie Woolery, directed by Braden Abraham, with music direction by Michael Mahler and choreography by Erin Kilmurray, is crackling, sharp, and radiant. The enchantment of love is articulated plausibly through poppy, happy songs that will follow you home, sung, danced, and acted by a collective that offers redemption in their very being. Life-affirming, love-affirming, and deeply, beautifully joyful—we need such antidotes to remind us of the magic that remains with us in small and large acts of generosity. —IRENE HSAIO AS YOU LIKE IT Through 12/14: Wed 2 and 7:30 PM, Thu–Fri 7:30 PM, Sat 2 and 7:30 PM, Sun 2 and 7 PM; Wed 11/12 and 12/10 7:30 PM only, Sun 11/23 2 PM only, no show Thu 11/27, Fri 11/28 2 PM only; open captions Thu 11/20, ASL interpretation Sat 11/22 2 PM; Writers Theatre, 325 Tudor Ct., Glencoe, 847-242-6000, writerstheatre. org, $45-$125, pay what you can Sun 11/30

RRichard Foreman lives Bad Behavior illustrates the queerness in the late artist’s work.