EN LA PEQUEÑA TIENDA DE LOS HORRORES

IN THE LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS

as flores son los órganos sexuales de las plantas. Esto parecería una extravagancia, pero la naturaleza se obstina en darnos prueba de su genialidad: entre más extraños resulten sus mecanismos de reproducción, será más sencillo para ellas perpetuarse. Las flores no conocen la discreción: sus colores, sus aromas, sus extrañas figuras y formas, parecen provenir de otros universos. Las orquídeas, por ejemplo, serían como gestos supremos de la vida vegetal: llenas de meandros y laberintos interiores, de extensiones y relaciones insospechadas. Vistas al microscopio, las flores (aquellas que son minúsculas, sobre todo) parecen seres extraterrestres, habitantes de otros mundos. Presencias

Flowers are a plant’s sexual organs. They may seem a bit of an extravagance, but nature insists on providing proof of its genius: the stranger a mechanism of reproduction is, the easier it will be for them to perpetuate. Flowers do not understand discretion: their colors, aromas, strange shapes and forms, seem to come from other universes. Orchids, for example, reign supreme in the world of plant life: full of meanders and internal labyrinths, of unsuspected extensions and relationships. Seen under the microscope, the flowers (those that are minuscule, especially) appear simply extraterrestrial, the inhabitants of other worlds. Disturbing presences, like flow-

inquietantes, las flores, regresan siempre a nosotros. Y nos muestran una imagen distorsionada de nosotros mismos.

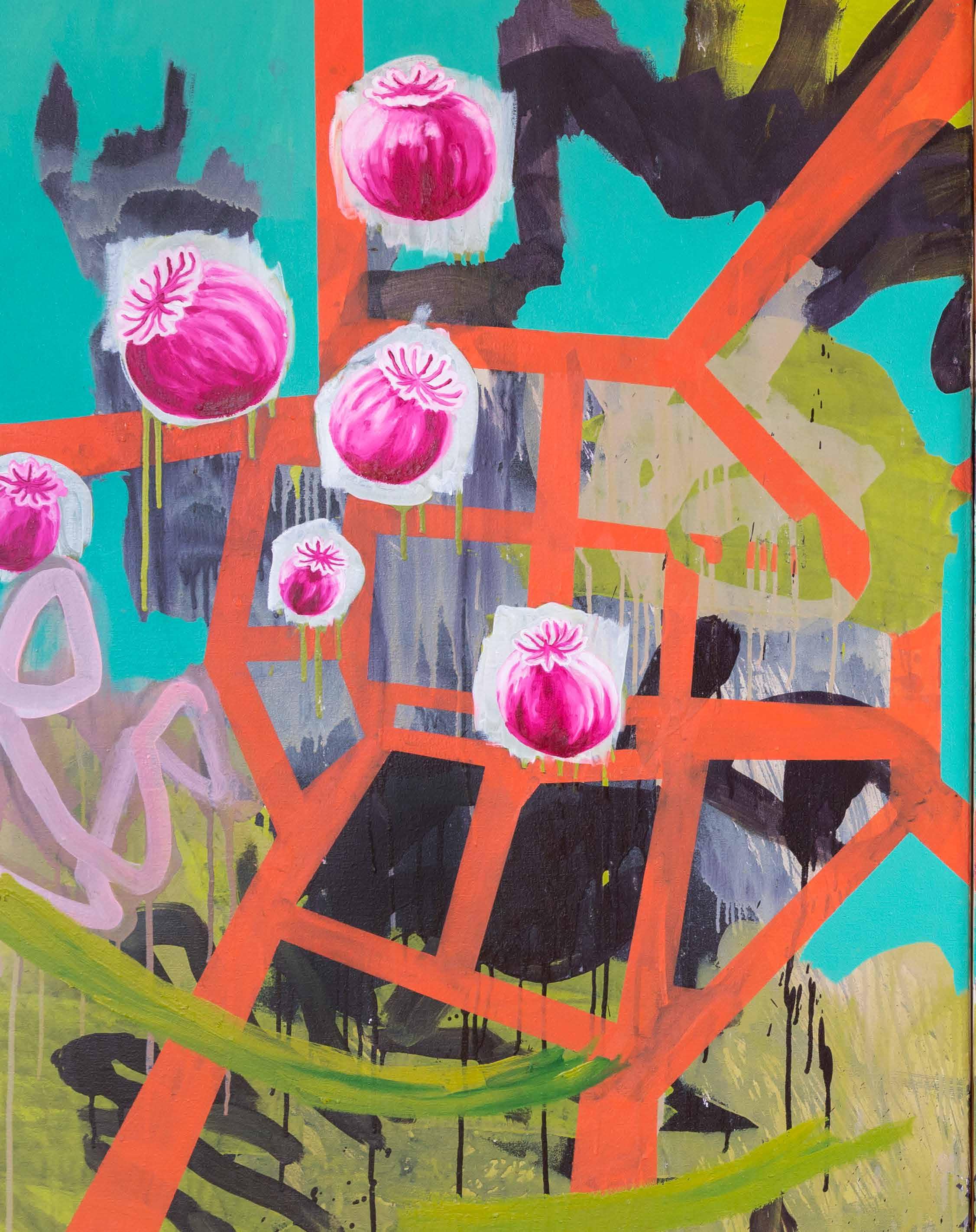

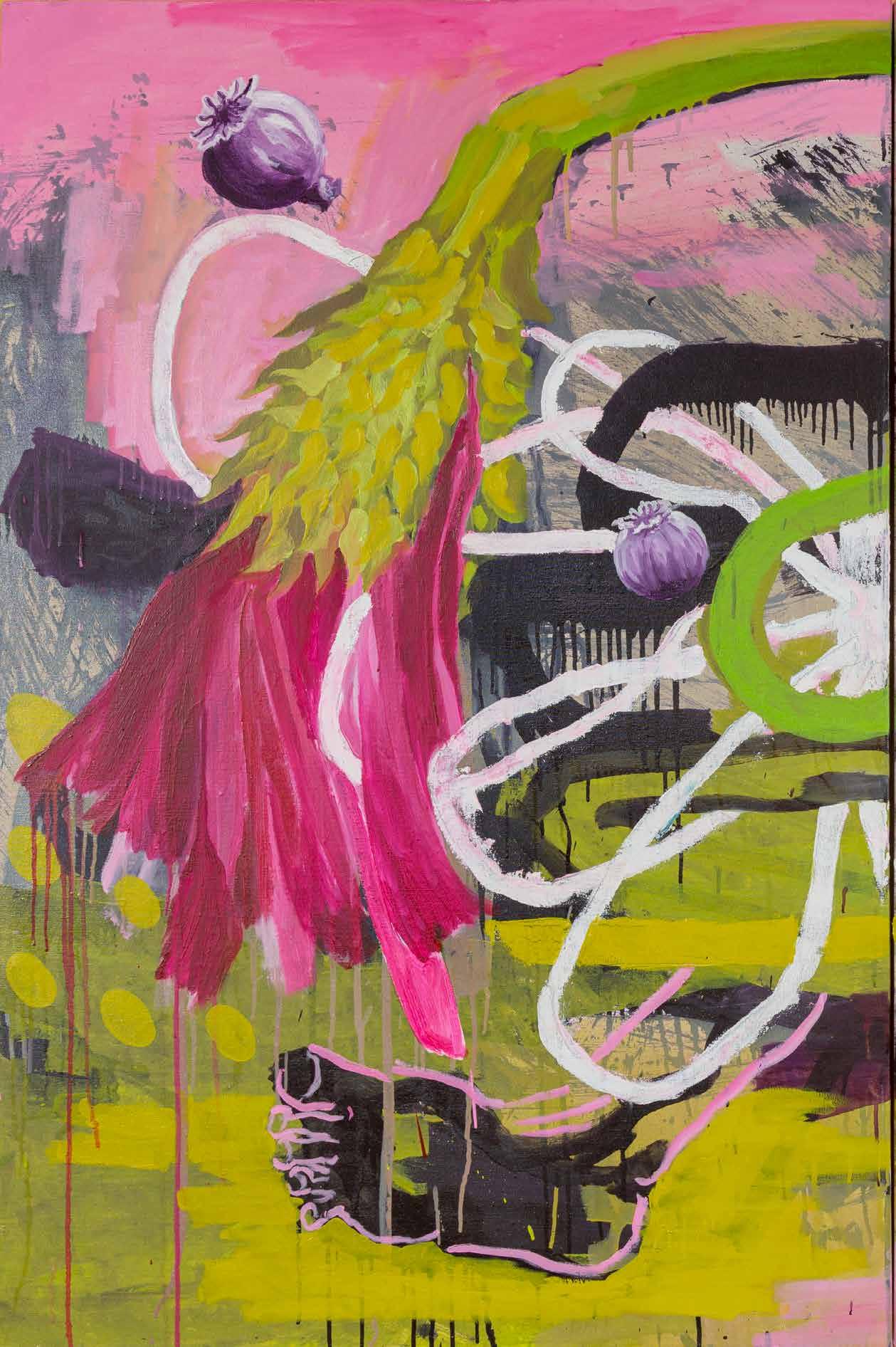

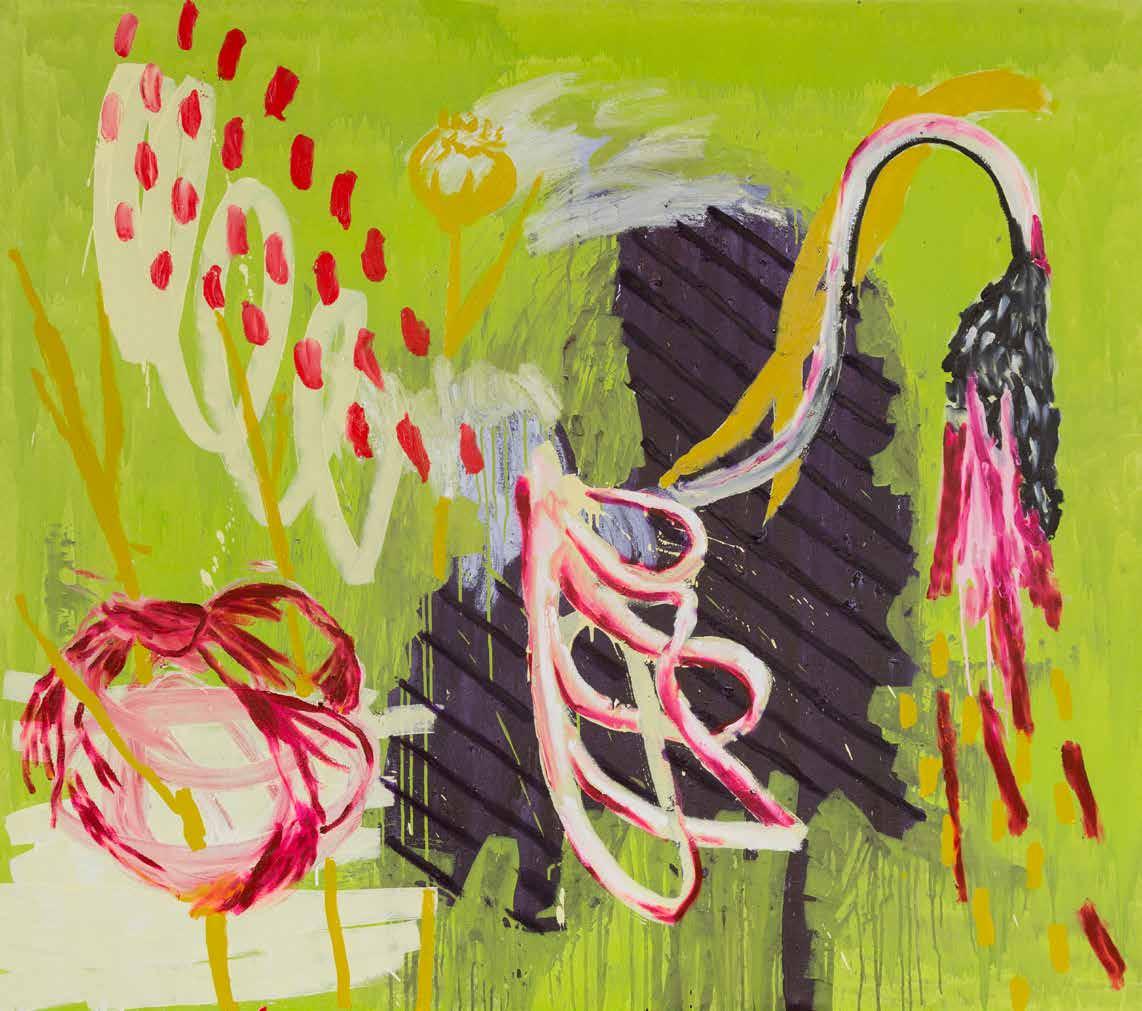

Cuando observamos atentamente las 21 pinturas de Lucio Santiago es inevitable hacerse ciertas preguntas: ¿cuál es la diferencia entre cultura y naturaleza, es decir, en qué se distingue la creación humana, su memoria, sus deseos, con el entorno natural? ¿Qué nos separa, en todo caso, del animal, de la piedra, de los tallos? Son preguntas que atraviesan toda la serie y que al final permiten delinear un horizonte que va más allá del mero hecho vegetal.

Podríamos sugerir que el pintor reunió toda clase de extravagancias visuales, como si las flores no fuesen sólo elementos performativos de sus pinturas, sino las pinturas mismas. Las flores como escenario, no físico, sino de un conjunto de ideas, de residuos, de imaginaciones. Pintar lo exterior y lo interior en un mismo gesto.

Hemos dicho extravagancias, sí, pero siempre con la necesidad de buscar armonía. Lucio Santiago quiere la conciliación en sus bastidores: los colores, ya de por sí eléctricos, se reúnen en una especie de memoria visual. Pretenden ir creando una nueva taxonomía: una que pudiera dar cuenta de nuestra extraña simbiosis con la naturaleza. Sus cuadros crean climas, sensaciones que parecen provenir y fluir de todas partes, pero que, al final, se conjugan en equilibrio visual. Los elementos, animales, vegetales, humanos (a veces fragmentos o

ers, always reflect on us. And they reflect a distorted image of ourselves.

When we look carefully at Lucio Santiago’s 21 paintings, it is inevitable that we ask ourselves certain questions: what is the difference between culture and nature, that is to say how is human creation, its memory and desires, different from the natural environment? What separates us, anyway, from animals, from minerals, and from stems? These are questions which are raised throughout the series and which, in the end, make it possible to draw a line that goes beyond the mere facts of plant life.

We could argue that the painter brought together all kinds of visual extravagance, as if the flowers were not only performative elements within his paintings, but rather the paintings themselves: flowers as a metaphorical setting, as a set of ideas, of waste, of imagination. The interior and exterior painted in the same movement.

We have used the word ‘extravagance’, yes, but always in relation to harmony. Lucio Santiago wants conciliation on his racks: the colours, already electric in themselves, are brought together through a kind of visual memory. They form a new taxonomy: one that can account for our bizarre symbiosis with nature. His paintings create climates, sensations that come and flow from other places but which, in the end, combine and balance visually. The elements, animals, plants, humans (sometimes seem-

recolecciones en apariencia azarosa de una mente herrumbrada) muestran esa tendencia natural de crear nuevos individuos, nuevas percepciones de vida. Así pues, cada pintura va explorando una taxonomía poco evidente, como si Lucio Santiago experimentara en un laboratorio imaginario y fuera creando caprichosas formas de vida.

¿Las pinturas son también imágenes mentales, recuerdos, pensamientos vertidos al color? ¿Los colores mismos personajes de una narración secreta? Ante esta serie de amplios formatos podríamos seguir deshilvanando preguntas. El artista prefiere que cada una de sus pinturas discurra, es decir, que no se someta más que a la volun-

ingly random fragments or recollections of a rusty mind) depict a natural tendency to create new individuals and perceptions of life. Thus, each painting explores an inconspicuous taxonomy, as if Lucio Santiago were experimenting in an imaginary laboratory, capriciously creating life.

Are paintings mental images, memories, thoughts made colour? Are the colours characters in a secret narrative? These wide-ranging notions mean we could continue to ask questions. The artist prefers each of his paintings to flow: he submits only to his own will, as he were feeding, watering or fertilizing a meta-

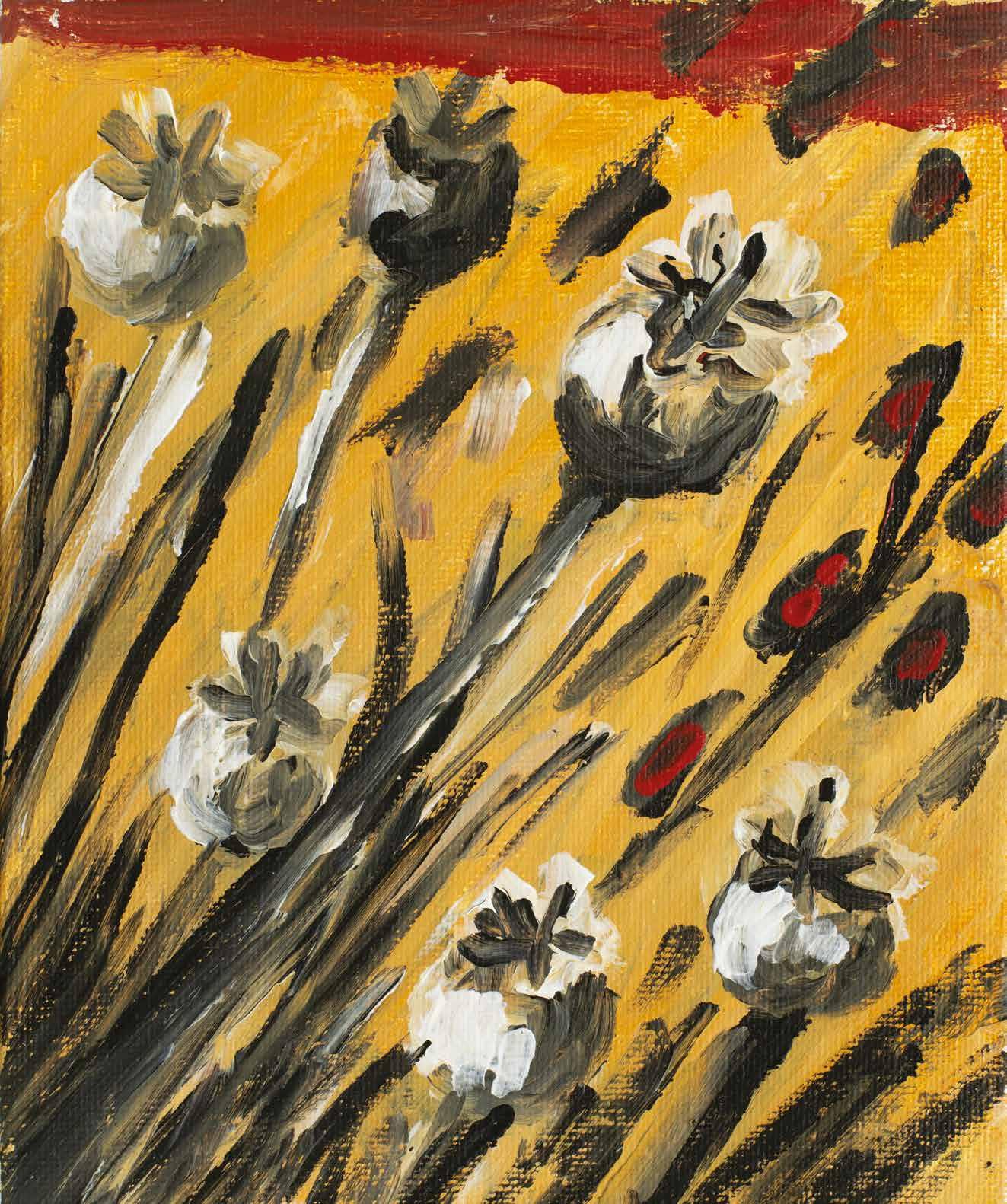

tad de sí misma, como si el pintor estuviera alimentando, regando o abonando con cada pincelada una criatura metamórfica. Estas piezas viven, del mismo modo en que lo hace la hierba en el asfalto o las bromelias epífitas en los cables de luz: dan cuenta del paso de la humanidad por un mundo que no le pertenece. Y al revés, la reconquista de la naturaleza sobre la cultura humana. Pienso mucho en la idea del combate cuando veo estas pinturas. En la lucha contra la nada y en la necesidad de dar forma a las horas. El artista muestra un constante choque de energía, un flujo que recorre todas las telas. Son diversas fuerzas las que se encuentran en el escenario

morphic creature with each brushstroke. These pieces exist in the same way as grass does on asphalt or epiphytic bromeliads do on power lines: they recall the passage of humanity through a world that isn’t theirs and, vice versa, the conquest of nature over human culture.

When I see these paintings, I think a lot about the idea of combat: the fight against nothingness and the need to give form to the day. The artworks reveal a constant clash of the artist’s energy, something that flows throughout the collection. Pictorially, there are many forces at work here. It’s a style of painting which records each of the artist’s movements

pictórico. Es una pintura que registra el movimiento y el impacto físico del artista: busca tanto la tridimensionalidad como la disolución de las formas. El movimiento del cuerpo es evidente. Una obra de arte no es un objeto físico, es también un flujo de energía en movimiento perpetuo. El título del conjunto pictórico lo ha tomado Santiago de una película de culto del mismo nombre, protagonizada por un joven Jack Nicholson y dirigida por Roger Corman en los 60. Esta es una de las películas de serie B más famosas de la historia del cine: una historia asombrosa creada con el más bajo de los presupuestos. La trama implica la posibilidad de que exista una planta que sólo puede alimentarse de sangre humana, y de la vida de un par de empleados de florería que harán todo lo que esté en sus manos para mantener viva a esa extrañísima criatura. Como es obvio, las cosas no salen bien, y este ser adquiere dimensiones y sentidos grotescos. Todo lo acontecido acaba siendo monstruoso, como bien podría ser un crimen multitudinario en una ciudad pequeña. Monstruoso y melancólico. Como las cosas que no podemos controlar. Un argumento cinematográfico se convierte en metáfora y, como sabemos, las metáforas también pueden irse abriendo o disgregando como una corola. ¿No son las flores, o las plantas, entidades que pueden exaltar los caracteres humanos, sus problemas, sus obsesiones más absurdas? El pintor utiliza el ejemplo de la amapola

and their physical impacts, leading to both three-dimensionality and the dissolution of forms. The movement of his body is evident. A work of art isn’t only something physical, but also a flow of energy in perpetual motion.

Santiago took title of this series of artworks from the name of a cult film, starring a young Jack Nicholson, directed by Roger Corman in the 1960s. It’s one of the most famous B-movies in film history: an amazing story created on the lowest of budgets. The plot implies the possibility that a plant exists which only feeds on human blood. The strange creature is kept alive by a couple of flower shop employees who will do anything to keep it fed. Obviously, things do not turn out well and the plant acquires both grotesque dimensions and meanings. As the plot unfolds, it becomes monstrous, in the same way a massive crime in a small city could be described: monstrous and melancholic, just like things we can’t control.

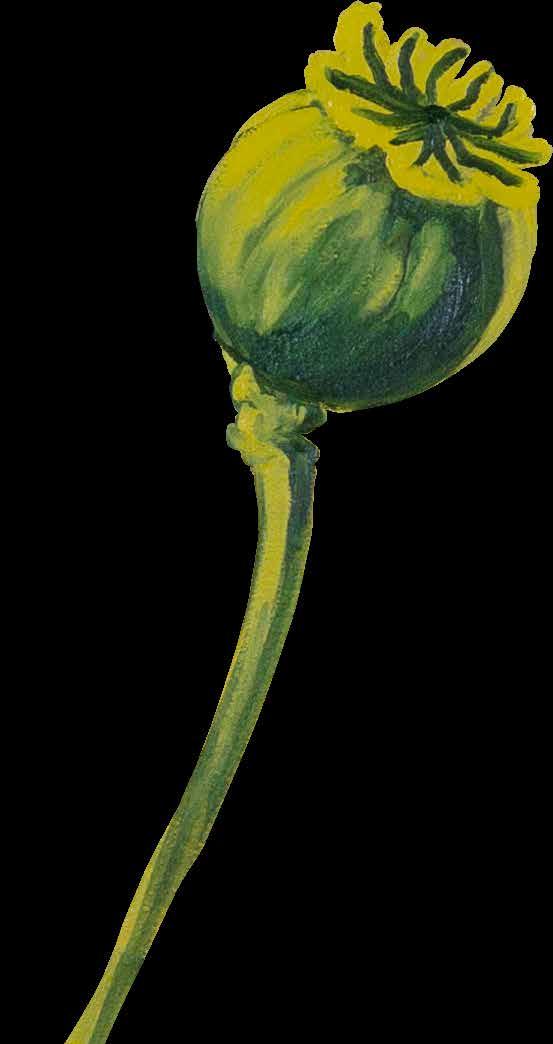

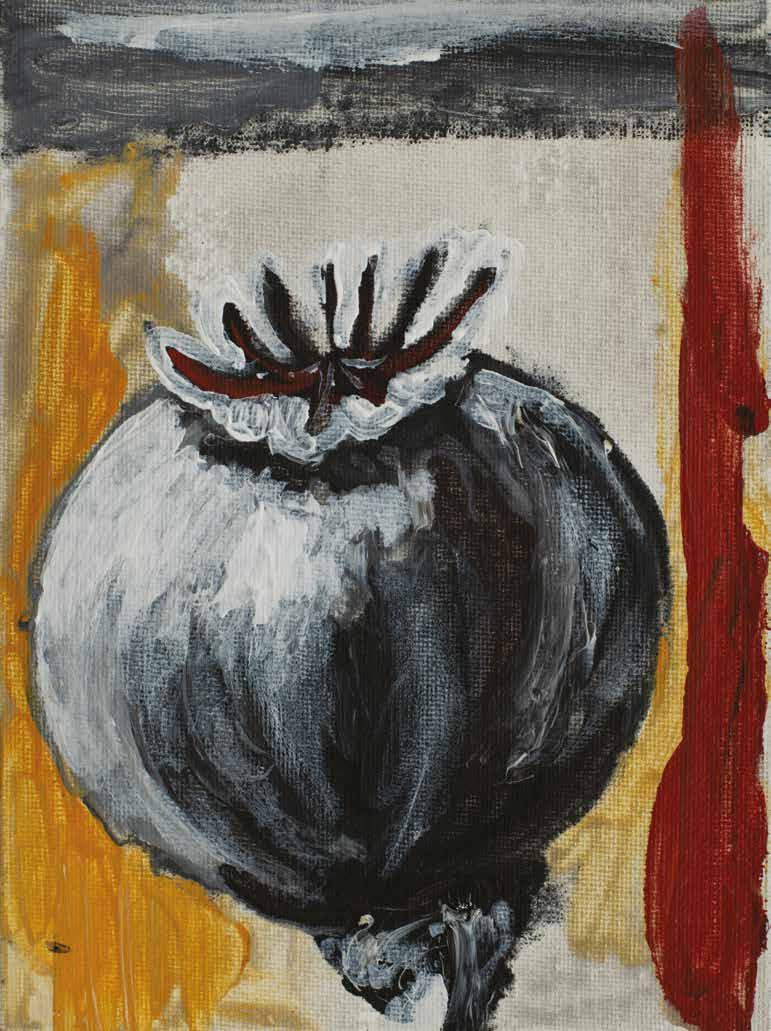

The cinematographic plot becomes a metaphor and, as we know, metaphors can also unfurl or disintegrate like a flower’s petals. Aren’t flowers, or plants, organisms that can exalt human characters, their problems, their most absurd obsessions? The painter uses the poppy (Papaver somniferous), for example, which has a relationship with dreams and the transmutation of deliria. It may not be

(Papaver somníferum), que podría tener una relación con el ensueño y la transmutación del delirio a las superficies. No debe resultar extraño que de las plantas también proceda el papel, el papiro… así podríamos sugerir el interés de Lucio Santiago por crear una narrativa paralela, un universo aparte con sus propias reglas. En Oaxaca cohabita el cultivo de las plantas ornamentales, narcóticas, alimenticias, sagradas: todo eso puede constituir nuestro espacio físico. Un jardín de plantas venenosas, hermosas y malditas… La fascinación por lo vegetal. La fascinación por lo humano.

Existen plantas completamente venenosas, de las que una sola gota de su savia podría matar a cientos de personas. La intoxicación, que es también una especie de envenenamiento, es uno de los grandes hechos de la cultura. La idea, ya muy extendida, de que el desarrollo del lenguaje, que es una forma de sinestesia, procede de la ingestión de hongos alucinógenos de modo accidental por primates durante largos periodos de evolución, nos da un indicio. Las drogas, en general, son ambiguas, porque es ambigua el alma humana: son tanto destructivas como orientadoras. Y Lucio Santiago toma esta ambigüedad a su favor, de ahí la combinatoria de sus cuadros.

Felisberto Hernández, el escritor uruguayo, escribió un breve relato llamado Las hortensias. Nunca es muy claro qué sucede. El cuento podría ser también un largo performance en el que los personajes inte-

surprising, then, that paper and papyrus also come from plants; from this we could infer that Lucio Santiago’s interest is in creating a parallel narrative, a separate universe with his own rules. The cultivation of ornamental, narcotic, food, and sacred plants coexists in Oaxaca: it creates our physical environment. We have gardens of poisonous, beautiful and cursed plants… and it is necessary to note it. There is a fascination for plants. There is a fascination for humans.

There are some plants which have a sap so toxic that it could kill hundreds of people. Intoxication, which is also a kind of poisoning, is one of the great facts of life. That there exists a widespread idea that language development, which is a form of synaesthesia, came about through the accidental ingestion of hallucinogenic mushrooms by primates during our long evolution, gives us a clue as to why. Drugs, in general, are just as ambiguous as the human soul is: they are both destructive and guiding. And Lucio Santiago uses this ambiguity to his favour, hence the combinations within his paintings.

The Uruguayan writer Felisberto Hernández wrote a short story called The Hydrangeas. It is never very clear what happens in it. The story could also be a long performance in which the characters interact with various objects. The hydrangeas could be a metaphor for the amazing colours within Lucio

ractúan con diversos objetos. Las hortensias podría ser una metáfora para hablar de esos colores alucinantes que acompañan las pinturas de Lucio Santiago: una ensoñación a la que te inducen ciertas plantas, ponzoñosas o carnivoras o simplemente de extravagante belleza… como aquellas del jardín de Beatrice Rapaccini, que no tenían más objetivo que rodear y preservar la belleza para que nadie se acercara a descubrir el interior de un espacio venenoso.

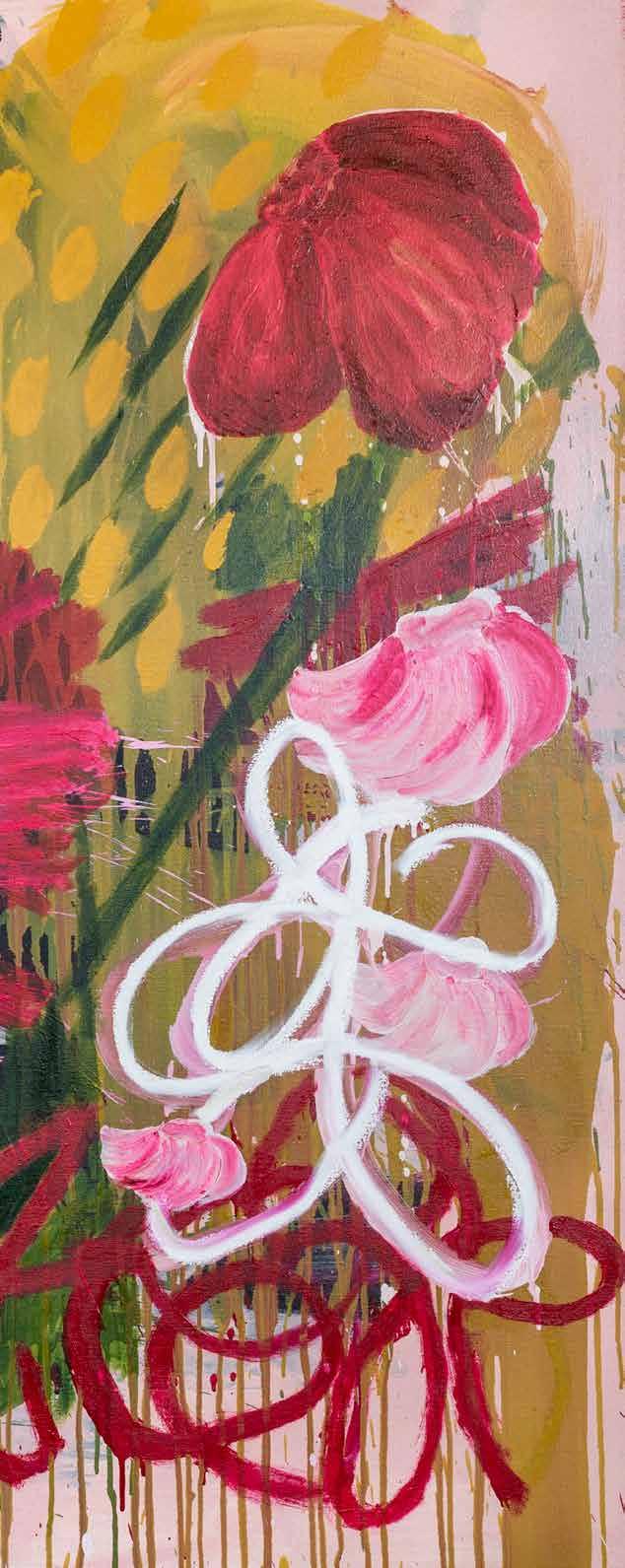

Lucio Santiago quiso agregar esta serie de pinturas a la historia de las flores en el arte. Una historia que se desgaja de la ilustración botánica, pasando por la obsesión de los bodegones, hasta llegar al presente, donde la planta no es sino disgregación de las ideas y de las formas. En este punto sería necesario preguntarse, ¿quedan todavía por descubrirse estados o figuras de las flores que aún no se han visto? La respuesta es afirmativa. Todavía hay mucho que ver, que contemplar, de las flores.

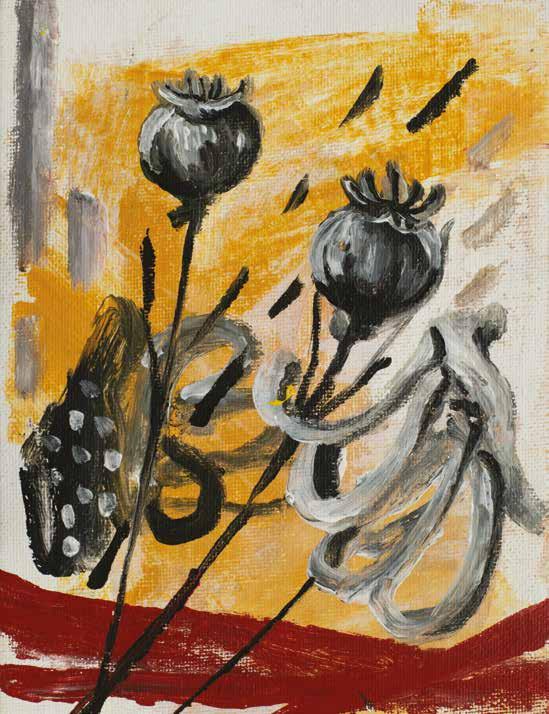

Pienso en el art brut cuando observo estas imágenes. No hay que olvidar que en su origen este arte evolucionó a partir de los gestos de enfermos mentales en el arte, es decir, de otras dimensiones de la psique. Estos creadores quisieron expresar su estado de ánimo, y pusieron a la naturaleza en un espacio único. Santiago ha asimilado desde su mirada particular este estilo artístico: existen los trazos fuertes, la necesidad de exaltar el choque de símbolos, el rastro o deseo de expresar lo originario. Y

Santiago’s paintings which bring about a reverie for certain plants and poisonous, carnivorous, or simply extravagant beauty… just like the plants in Beatrice Rapaccini’s garden which have no other reasons to exist than to create and preserve beauty so that no one comes close to discovering a poisonous interior space.

Lucio Santiago wanted to add this series of paintings to the history of flowers in art. This story, however, breaks away from botanical illustration, passes beyond the obsession of still life’s and reaches the here and now where a plant is nothing more than a disintegration of ideas and forms. At this point it is important to ask whether there are states and forms of flowers which have never been seen and which are yet to be discovered? The answer is yes. There are still many flowers to see and to contemplate.

When I look at these images, I think about art brut. It is important not to forget that this art form originally evolved from visible symptoms of mental illness in art. In short, from other psychological dimensions. These artists wanted to express their mental state, and they did that by moving nature in a unique space. Santiago has incorporated this artistic style, but through his own gaze: there are strong lines, the need for symbols to clash, the desire to trace and express the original. Santiago, however, adds a fur-

Santiago agrega un elemento más: el gusto por el detalle, la exaltación y la meticulosidad del objeto. En este sentido, la búsqueda de Santiago va creando un estilo: un lenguaje, una obsesión. Y eso es también el arte: obsesionarse con lo que se mira a través de las rendijas de la memoria. Todo lo que se ve, lo que se toca, lo que se habita, se convierte en aquello que transforma al artista.

ther element: the detail of his object and his exaltation of the meticulousness of it. In this sense, Santiago is searching for and creating a unique style: a language, an obsession. Obsessing over what you see through flickering memories is also art. Everything that is seen, touched, inhabited, becomes something which transforms the artist.

Al mirar estas pinturas vienen a nuestra mente fogonazos de pinturas de un joven Gerhard Richter y fragmentos de un Neo Rausch. E incluso de Peter Doig. Pero serían influencias soterradas, ya que Lucio Santiago toma también de la literatura y del escenario social muchos elementos que desembocan en su obra. Además, es posible afirmar que está generando un estilo propio, que se vale de la combinatoria y del uso del azar buscado o producido. Al pintor le interesa jugar, plantear preguntas o enigmas con cada cuadro.

Los habitantes de las cavernas pintaban para sobrevivir, como un acto reflejo, para dejar marcas y vestigios… Muchos años después, ya con la invención de los alfabetos, el papel y las superficies, los artistas han intentado dejar ese mismo rastro. Lucio Santiago intenta crear un jardín: un espacio de recogimiento interior, alejado del ruido de la era actual. Sin embargo, es consciente que todo jardín también debe tener plantas venenosas.

Flashes of paintings by a young Gerhard Richter, fragments of Neo Rausch, and even Peter Doig, come to mind when looking at these paintings. But, as Lucio Santiago also borrows many elements in his work from literature and the social scene, these influences are almost completely hidden. It’s also possible to say that he is generating his own style, combining that which is sought or produced by chance. The painter plays games, asks questions or creates enigmas within each painting.

Cave dwellers painted to survive, as a reflex action, to leave marks and traces… Many years later, with the invention of alphabets, paper and surfaces, artists have tried to do the same thing. Lucio Santiago has done this by creating a garden: a space for interior seclusion away from the noise of the current era. However, he is aware that every garden must have some poisonous plants.

Guillermo SantoS

Guillermo SantoS

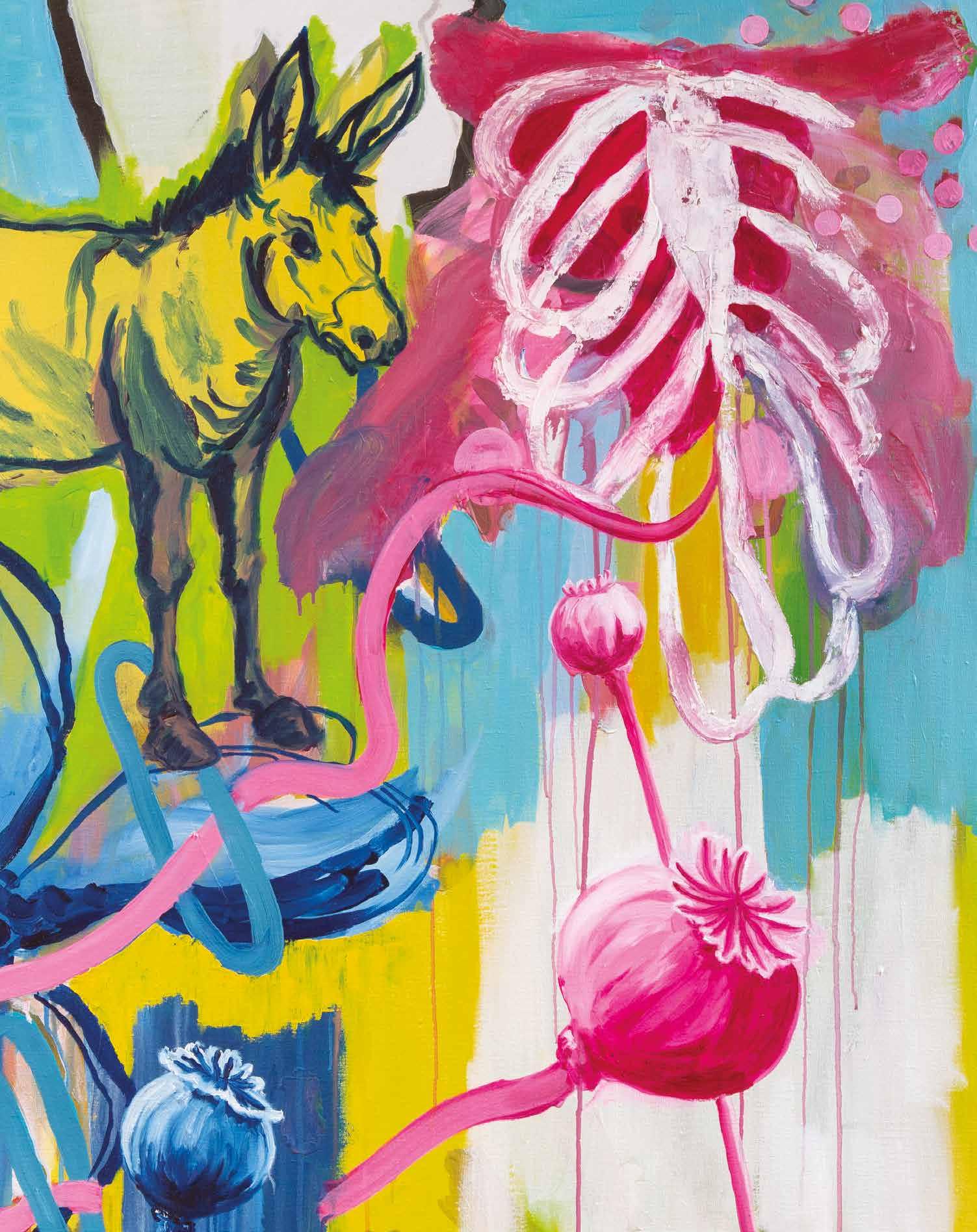

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 160 x 120 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 170 x 150 cm | 2021

sobre tela | 170 x 150 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 160 x 120 cm | 2021

Página anterior

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 150 x 200 cm (díptico) | 2021

Sin título

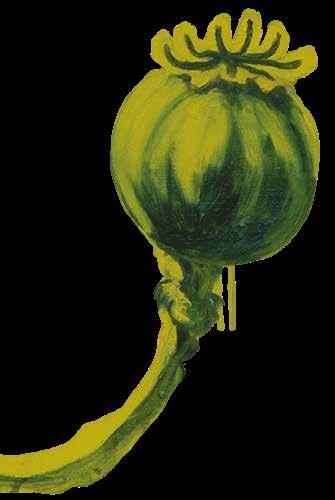

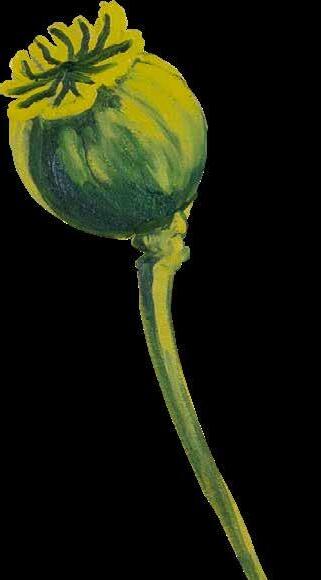

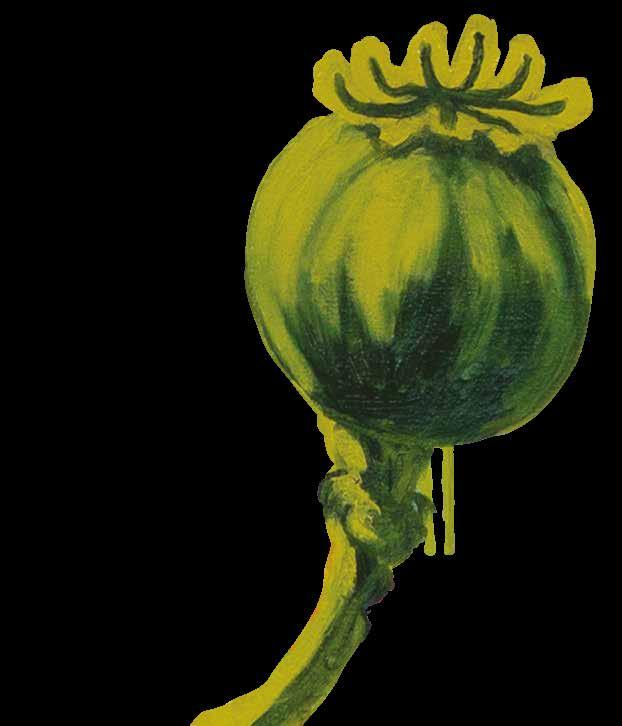

Óleo sobre tela | 45 x 45 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 45 x 45 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 150 x 170 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 200 x 180 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 150 x 200 cm (díptico) | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 75 x 75 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 75 x 75 cm | 2021

Página anterior

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 150 x 300 cm (políptico) | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 200 x 150 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 200 x 180 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 200 x 180 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 170 x 150 cm | 2021

Sin título

Óleo sobre tela | 150 x 200 cm (díptico) | 2021

Sin título

| 150 x 200 cm (díptico) | 2021

Óleo sobre tela

título

Óleo sobre tela | 120 x 100 cm | 2021

Sin

Sin título

sobre tela | 175 x 400 cm | 2021

Óleo

The flowers that I have never given

Por las flores que nunca he regalado

atiEnda dE los horro r E s de LucioSantiago , sete

tipográficas: Frutgier y Kepler . Eld uleto Estud i o . S e t i r nora je052me acitsúr 05y ne atsap .arud

r en ene r o d e l 2 0 22 ne sol

aLedserellat araP.acfiárGall us nóicisopmoc es noraelpme