The North Buffalo Rail Trail Equitable Community Engagement Framework is an important com prehensive step that will help to enhance our collective community space within University Heights. Collaboration for the plan was performed by students at UB’s Environmental Design Program studio led by Darren Cotton, assisted with the support of volunteers and members of the University Heights Collaboartaive (UHC). The Tool library’s role was instrumental in the formation of this project.

Darren Cotton

Madison Rios

Chris Kameckl (Local Artist & Activist)

Jennifer McQuilkin (M&T)

Jajean Rose (Western New York Land Conservancy) Ashley Smith (GOBike)

Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority

Bert’s Reddy Bikeshare

Bert’s Wegmans Food

Richard Anderson

Rasheed Aribidesi

Julia Bertolini

Caitlin Chan

Reilly Dzielski Olivia Jiang Tanner Laramee Fanny Liang Ellison Mcmahon

James Metzger Maegen O’ Hara Brittany Robinson

Trevor Rubino

Angus Sunday Serina Valletta

Jacob Vollers

Taylor Wallace Sage Welte Bobby Zhao

Stephen Arlington Mike Cartwright

Overton-Burns Dayna Linda Garwol Candy Hayes Raymond Reichert

The role of an urban planner has changed dramatically to plan with a community, no longer for a community. Interactions and conversations are important, as isr engaging with a community and having the ability to engage by their ideal circumstances is equitable for the community. This report will examine the lessons, experiences and best practices of equitable engagement and its importance to its study area.

Located in Buffalo, New York, students of an Environmental Design studio from the Universi ty at Buffalo were presented with the nearby ‘Starin Nature Preserve’, an abandoned rail corridor now inhabited by wildlife. Adjacent is the Minnesota Linear Park and Buffalo Rails-to-Trails multi-use path, which are all sites located in the University Heights neighborhood. There is an apparent risk to transform the study area into a residential development, yet previous advocacy, civic involvement and determination preserved the nearby park and path from similar circumstances. Both a dependent and independent variable, practices and principles of equitable engagement was vital to this triumph. An opportunity has come to allow the Starin Nature Preserve a chance at preservation. Similar to the sur rounding Linear Park and Rail-Trail, understanding how people visit and interact within the study area would not be possible without demonstrating equitable engagement actions.

Throughout the duration of the studio course, students were introduced to what equitable engagement is and its purpose in the profession today. Comprehensive assignments in review, explo ration and synthesis broadened understanding of the principle while students’ skills in background research supplemented these efforts. Among frequent evaluations and assessments of their under standing of equitable engagement, students welcomed and absorbed additional context of their project by means of interviews, site visits and impromptu community service experiences. The accumulation of these assignments and experiences prompted students with the challenge to identify barriers in equitable engagement and provide solutions that could be implemented for future processes of the report’s project study area. At the beginning of the course, a subsequent task was also introduced for a future service event that the studio class was to plan for. A garbage clean-up event was scheduled near The Tool Library, a local community asset and non-profit organization, for the Minnesota Linear Park and Rails-to-Trail path; coincidentally, The Tool Library was founded and is directed by the studio course professor.

In the cumulative period consisting of classroom instruction, event planning and community involvement, the studio class piloted their solu tions involving equitable engagement at the clean-up event and recorded observations for future reference and analysis. In summary, this report is the culmination of exposure, committed efforts, and evaluations of the studio class’ understanding in equitable engagement practic es to recommend a viable plan for future planning frameworks.

In the 21st century, the process of city planning has evolved unprecedentedly. The rapid chang es in connectivity and our environment have challenged us to plan urban environments more responsibly, and more consciously. In general, cities, towns and villages legislate land use, or what is appropriate to be built where, but the communities and natural resources in those areas are responsible for taking care of that land. Like wise, communities are the voices for its land and resources and are its advocates for what it should be, or to become. Recognizing this, modern practice of urban planning must question how to effectively engage.

Today, many planning organizations have transformed engagement processes to effective ly interact with the locale. Realizing continual change in human behavior, modern events and technological innovations, these groups have faced scrutiny for their engagement methods and have been called upon to create fair, or equitable options to engage and communicate. Remark ably, these planning and development projects have seen success results increase by equitably engaging with neighborhoods, communities, and local stakeholders; in result, residents and com munities of these neighborhoods gain influence and resources to improve their surroundings that address their immediate needs.

Traditionally, city or town officials will hold public meetings or hearings to allow their citizens to discuss and debate plans in action on public matters. However, given the scale of urban growth and its consequences, residents and groups have been repressed from voicing their concerns on land use or planning projects. This has resulted in building developers, local officials and even individuals to take advantage of communities and neighborhoods because of no one knowing where to voice their concerns, or of developments in general. Observing the long-lasting effects of this previous engagement process of planning, com

munities and neighborhoods have been physically separated, isolated and disconnected from those around them.

In the early 20th century, racial seg regation rampantly divided communities and neighborhoods by actions of redlining, restrictive covenants, and even physical prevention. Redlin ing prevented demographic minorities from obtaining federally-backed mortgages because of both the house’s location and racial bias, which resulted in a national consequence of massive impoverished housing and segregated neigh borhoods. Similarly, private homeowners had amended their property deeds using exclusion ary conditions to restrict purchasing privilege. Although these practices were deemed uncon stitutional and outlawed in 1968 under the Fair Housing Act, their social consequences carry into now; minority neighborhoods verily experience immeasurable disinvestment and have become greatly overlooked in their local value. Massive roadway projects had also taken priority in

planning developments throughout the mid1950’s into the 1960’s. Continuing similar prac tices of geographic discrimination, urban ex pressways and national interstates had bisected minority areas which physically separated neigh borhoods and communities even further. Even more, public transportation options and availabil ity saw drastic reductions and suspensions, which continue assisting in isolating minority popula tions from their ability to live, interact and engage with their cities.

Equitable engagement recognizes these existing disparities have disempowered commu nities from advocating for their needs and pri orities. Genuine efforts to extend empathy and understanding has informed planners and offi cials of their neighborhoods’ barriers to succeed. By adjusting former and impractical engagement techniques to be inviting and effective, the foun dation of practicing equitable engagement meth ods become more personal, more transparent, and more trustworthy to implement and revitalize communities.

Recent movement patterns show that living in urban or denser environments have become increasingly popular. In contrast, green spaces and public places have become scarcer in urban environments because of existing infrastructure, as well as natural changes in climate. Researchers who have studied the effect of accessible public places found health benefits and neighborhood involvement significantly increase with greater opportunities to use nearby parks and trails.1 Ob serving this relationship, new developments are seen to advertise their proximity to natural spaces and recreation trails for nearby residents, however these developments tend to be exclusionary to existing communities and inhabitants. This trend of “green gentrification” is harmful to existing

communities of nearby nature recreation areas, as they are intended to be enjoyed by newer, and typically wealthier residents.2

Understanding this context, activism among communities across the nation have em powered them to advocate and be more involved in improving and developing nearby green spaces. Knowing that many will share this space is piv otal in providing equity and fairness to original neighborhood residents. Applying inclusionary practices for green space development have gen erally seen varied results, but local successes and continued involvement has proven effective and successful. Local examples are the dependent base and purpose of this report’s project, as the studio class is introduced to the nearby “Starin Nature Preserve” green space.

The studio class of this Environmental Design workshop for the Starin Nature Preserve is intro duced to the practice and importance of equita ble engagement and how it differs from former public engagement methods. Facing an altered circumstance of green gentrification, the Starin Nature Preserve is primed to be developed into single-unit, residential housing which would raze the now naturalized abandoned rail corridor that exists now. Home to local wildlife, it encompases the nearby Buffalo Rail-Trail, which had former ly experienced similar lack of care. Now a vital community asset, the Rail-Trail is enjoyed by the local University Heights neighborhood and sur rounding residents. To preserve the Starin Nature Preserve, utilizing equitable engagement practices is imperative to the study area’s success as harmful development patterns could afflict more exclu sion and displacement. Elements of community development such as regenerative development, asset-based community development and place making will be key tenants in effectively applying equitable engagement methods. In broadening understanding of equitable engagement, acquired

1 The Case for Healthier Spaces. Project for Public Spaces. (2016). https://tinyurl.com/5szucpb2.

2 Inclusive Trail Planning Toolkit. J. Raskin. (2020). https://tinyurl.com/yckkwawj.

organizational skills will be applied at an on-site event to serve as the case study for the studio class’ comprehen sion of practicing equitable engagement.

Moving forward, the studio class has identified key values to reflect upon throughout the course of this project. These values are to remind the reasons for using equitable engagement methods, and how these values are received by community members when in action. Although the class sug gested many values, those that guided this studio workshop included diversity, inclusion, equity, and accessibility. Throughout this report, these values are commonly apparent as the University Heights community defines and embraces these characteristics that serve as common ground for the studio class’ journey with equitable engagement.

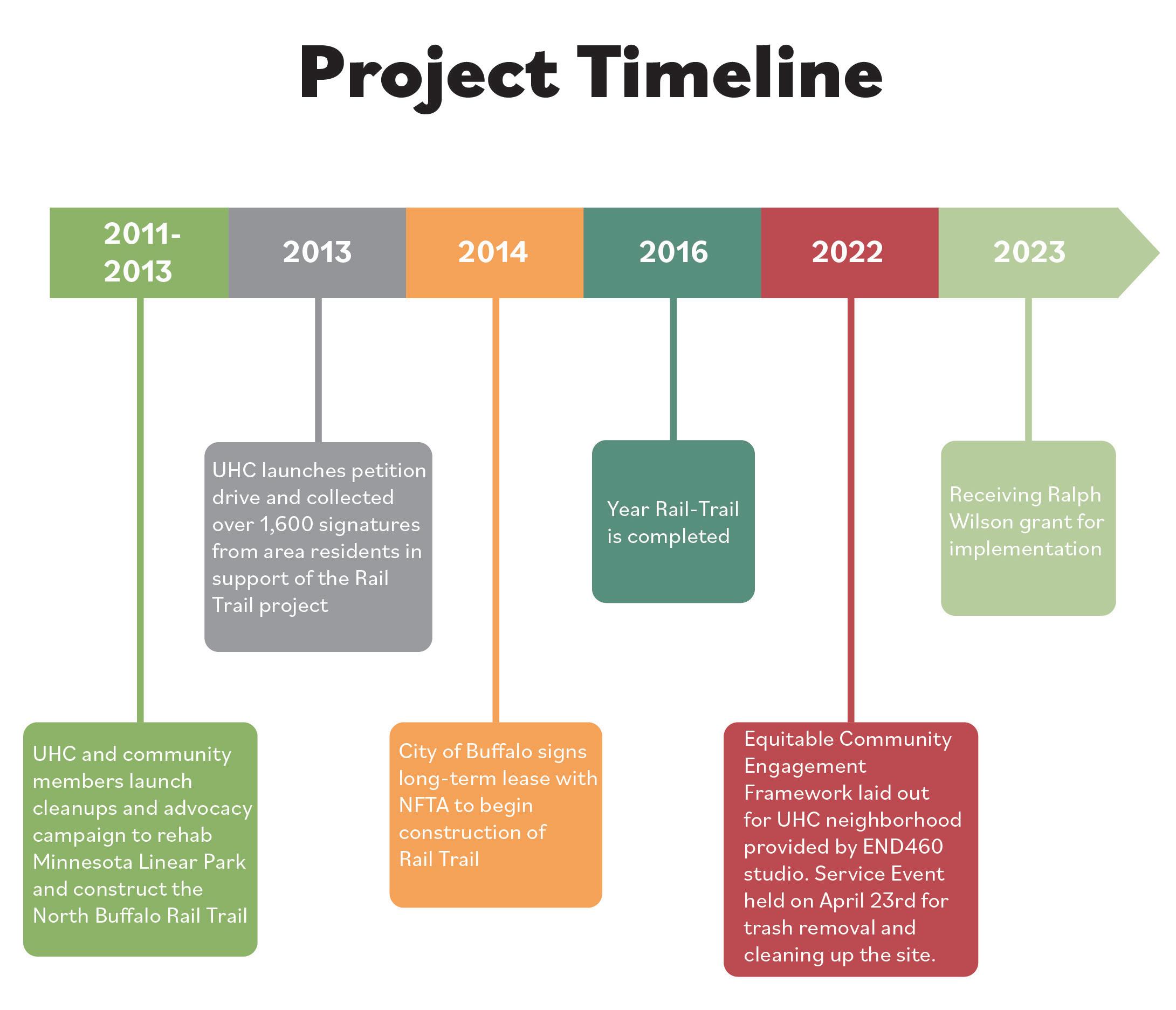

The North Buffalo Rail Trail has been specifically noted in many recent local plans. The study area of this studio project holds significant potential to be integrated into the region’s greenspace and bicycling network system. Of these plans including Bike Buffalo Niagara, One Region Forward, and the Empire State Trail, each report and their respective inclusions of the project study area repeated its value across all scopes. Reviewing the locally-focused Bike Buffalo Niagara and One Region Forward plans, each thoroughly evaluates existing site conditions and vocalizes key values of equitable engagement precepts that have helped their planning efforts. In interest of the Bike Buffalo Niagara report plan, the study area has been designated as a high-priority off-road path project because of its invaluable potential of connecting two distinct areas of Buffalo, along with completing a fragmented path of New York’s Empire State Trail. Both the Bike Buffalo Niagara and One Region Forward reports frequently recall and advocate for equitable practices that empower and connect underserved communities. In addition, dozens of figures between the two reports consisting of response inquiries, event photographs and in fographics reaffirm benefits of equitable engagement practices including asset-based community devel opment and inclusive discussions and decision-making. From all plan reports, significant recognition of the North Buffalo Rail Trail’s value can be attributed to repeated efforts and genuine investment of equitable engagement practices. Understanding the roles many organizations and stakeholders as sumed, the studio project is humble to continue the study area’s current progressions by studying and refining the best equitable engagement strategies specifically for the University Heights neighborhood.

In August of 2018, Durham was directed to “create an engagement plan that will allow the City to create a racial equity plan regarding the Belt Line,” (2018, 2) in response to resident concerns regard ing equity. Over ninety days, a blueprint was developed to reframe the city’s engagement process. The goal was to create a framework that could be used for community engagement procedures for future projects across the city. The city council recognized that it is crucial to be more inclusive with their de cision-making process and prioritized finding strategies to engage with demographics that have been historically dismissed. The identified general themes include accessibility, accountability, power-shar ing, inclusion, information, timeliness, and transparency.

The first thing they did was adopt a set of values. The values that were identified were: right to be involved, contribution will be thoughtfully considered, recognize the needs of all, seek out involve ment, participants design participation, adequate information, and known effect of participation. Their next step was to collect baseline data on who was currently involved with engagement and those who were underrepresented. The Community Engagement team then met with community members to understand more about why people aren’t more involved in engagement and different ways to engage with those residents.

After analyzing the data collected from both research and talking to residents, the city drafted the Steps to Build Equitable Community Engagement Plan. This is a five-step plan that focuses on the level of engagement that should be used, who should be engaged, how engagement should happen, how to measure successful engagement, and how to build for the long-term. This draft is not a one-size-fits-all; however, it outlines key components of how the engagement process should be delivered. This blue print was applied to the Durham Belt Line Trail Equitable Engagement Plan and continues to help the city perform equitable engagement and build trust within the community.3

The Neighborhood Improvement Services Department (NIS) works to preserve and improve quality of life conditions for Durham residents, and to encourage active participation in neighborhood redevelopment and public policy and decision making dialogue. The Community Engagement Team strives to inform, engage, partner and empower the Durham community.

The City has not executed a standardized process for conducting community engagement that is shared or adopted by all Departments. Furthermore, the City has not developed an equitable community engagement process that ensures that its outreach or information gathering approaches include an intentional effort to engage a representation of the City’s diversity. The Community Engagement Team of NIS, to match the goal of encouraging active participation in neighborhood redevelopment and public policy and decision making dialogue, has created an Equitable Community Engagement Blueprint through conversation with other departments and community leaders.

The City of Durham strives to be a welcoming, diverse and innovative community. Equity and resident engagement are key components of the City’s FY2019 2021 Strategic Plan, includes Advance a More Inclusive and Equitable Durham, Shared Economic Prosperity, and the Language Access Plan.

“Many current inequities are sustained by historical legacies and structures and systems that repeat patterns of exclusion. Institutions and structures have continued to create and perpetuate inequities, despite the lack of explicit intention. Without intentional intervention, institutions and structures will continue to perpetuate racial inequities. Government has the ability to implement policy change at multiple levels and across multiple sectors to drive larger systemic change. Routine use of a racial equity tool explicitly integrates racial equity into governmental operations.”

(Government Alliance on Race & Equity, 2018)

In order to create strategies for equity to achieve the City’s vision of an excellent and sustainable quality of life for all residents, the City must engage the community in an equitable way.

3 Equitable Engagement (Equitable Community Engagement Blueprint. City of Durham NIS Community Engagement. (2022). https://www.durhamcommunityengagement.org/equitable_engagement.

Southern Tier Trail is a proposed trail connecting Erie and Cattaraugus Counties in Western New York, following the Buffalo-Pittsburgh rail corridor. This trail features on-road and off-road routes. This trail spans 80.1 miles. It is recommended for pedestrians, bicyclists, equestrians and snowmobil ers. This project was broken into twenty-three subsections. These focused on connection to existing trails, population density, right-of-way availability, public support, municipal support, access to ameni ties/destinations and maintenance support.

A large emphasis on trail connections drives the project. Positive impacts of this include health and well-being of the users. This helps with the likelihood of heart and respiratory diseases. Another positive impact is safety, allowing bicyclists and pedestrians a safe passageway without the interaction of vehicles. Transportation is also a positive impact, as this trail can be used to increase mobility and accessibility to those who don't have access to a vehicle or public transit. Lastly, the trail positively im pacts the economy of the area, boosting tourism, property values, development of new businesses and outdoor recreation.

To get public input on the trail, various meetings were held with the stakeholders, homeown ers, municipality leaders, nonprofits and trail users. These meetings were held to collect more specific feedback. GOBike also engaged in one-on-one outreach, calling to municipal and community groups or organization leaders to gather information, impressions, and local knowledge as inputs to draft planning documents. They also held public meetings, allowing the public to give their input online in maps. This helped gauge what the community actually wanted for the trail.4

This relates to our project through its importance of greenspace and trails. Trails impact com munities positively, through health and wellness. These spaces can help create a more community driven area, and pride in nature.

jqxbf2lAIzB0XcgdlJ4sEWujq_/view.

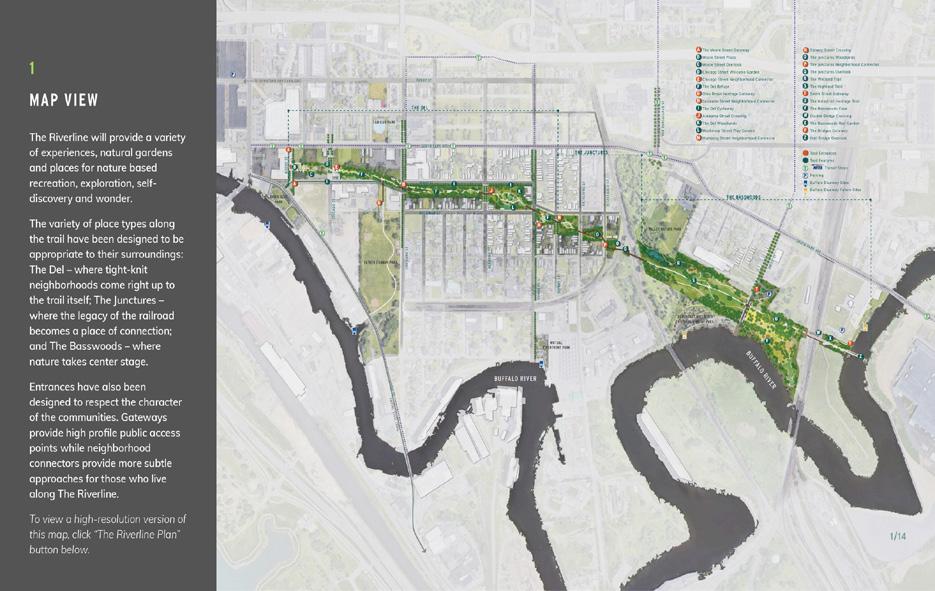

The Riverline5 is a one and a half mile long nature trail and greenway being developed on a former elevated rail corridor adjacent to downtown Buffalo and the Buffalo River. The Western New York Land Conservancy is developing The Riverline based on a vision created by the community through means of equitable community engagement. This multi-use nature trail and greenway has the potential to build on the heritage and vibrancy of three historic neighborhoods– the Old First Ward, Perry, and the Valley. The vision of this trail inspired an international design ideas competition with close to 100 design proposals– a professional jury and community members selected their favorites and winners were decided in various categories. The most recent update in the process was in July 2021 which an nounced the land conservancy and their award-winning partners’ concept designs.

The guiding principles for this project was to prevent cultural displacement while revitalizing the neighborhood, ensure that programming reflects and empowers the history and culture of the surrounding neighborhoods, and promote art and cultural opportunities for current residents. Key themes that were focused on were equity and accessibility, active recreation and healthy living, and strengthening connections between neighborhoods. While discussing the importance of equitable community engagement, these topics were determined to be relatable to the Rail Trail. Similar to the Riverline, the Rail Trail also has many cultural and historic aspects that are prioritized and respected. 5 Equitable Development Framework for The Riverline. University at Buffalo Regional Institute, The State University of New York at Buffalo, School of Architecture and Planning, and Make Communities. (2020). https://brandcast-cdn.global. ssl.fastly.net/d8824b65-42d7-4e51-9cda-37b31642c352/08f61f06-aa94-49fb-9a72-fd404f857589/69a9c40dd995176eaf babb90dbd9238a/TheRiverline_EquitableDevelopmentFramework_June2020_SinglePages.pdf.

Buffalo was first settled in 1789 in an area previ ously occupied by the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) confederacy of six nations: Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. The city was founded in 1801 and incorporated in the early 1830s. Buffalo’s location at the convergence of the Niagara River with Lake Erie allowed for the city to establish itself as a transhipment hub for grains coming from the Midwest. During the Industrial Revolution, Buffalo was the eighth largest city in the United States and much of its success can be attributed to the Erie Canal, which was completed in 1825. Within the decade, the success of the canal was overshadowed by new railroad technologies as the steam locomotive emerged as the primary form of goods and livery transportation. 6

After World War II, the city of Buffalo was the second largest railroad hub in the U.S. and over 700 miles of track ran through the city. The railroad industry was booming and provided ample job opportunities, but this later changed. After the construction of the Interstate Highway System, automobiles became the preferred mode of transportation. Combined with outdated reg ulations and high taxes along with the exodus of downtown Buffalo residents, the railroad industry started to decline in the mid 1960s. Railroad cor ridors were abandoned and remained as unused spaces for decades until recent years. A movement started to transform the abandoned rail lines into public trails for recreational use. The Heath Street Block Club and Merrimac Street Block Club, along with other community members, were able to secure $1.7 million in federal funding to turn the Erie Lackawanna (EL) Railroad into a vi brant trail that people use for exercise, relaxation, and social activities. The shift from rail line to abandoned space to essential greenspace in the community exemplifies how we can transform forgotten spaces into dynamic multi-use spaces

throughout the city, and thus help build commu nity relations, connect various neighborhoods, and improve the local economy.7

The site we will be discussing in this report is unofficially named the “Starin Nature Preserve.” It is an area consisting of approximately 17 acres of undeveloped land, formerly occupied by rail lines, adjacent to Minnesota Linear Park. The Starin Nature Preserve is bounded by neighbor hoods to the north on St. Lawrence Avenue and Brinton Street, neighborhoods to the south on Taunton Place, the University Heights District to the east, and to the west by Starin Avenue. The eastern portion of the property intersects with the recently added Minnesota Linear Park, providing a linkage between neighborhoods that were pre viously separated by infrastructural barriers. To the west, the newly created Rachel Vincent Way is the location of a new housing development and is built along another abandoned portion of the former rail lines.

From Main Street, access to Starin Nature Preserve can be obtained by walking to the rear of the parking lot behind the LaSalle Metro Rail and

6 Early History of Buffalo (ca. 1790’s-1853). J. Walkowski. (2011). https://buffaloah.com/h/jw/bflo.html.

7 University Heights, Links to Buffalo Architecture and History Website. C. LaChiusa. (2016). https://buffaloah.com/h/u. html

following the rail trail along Minnesota Linear Park to the “crossroads.” Walking north, there is abun dant greenery and wildlife surrounding the park. It is not uncommon to see various species of wildlife, such as birds, rabbits, or even deer during a visit. There are limited benches on the path for resting, but there is ample street lighting, making it safer for nighttime use. At the “crossroads,” the rail trail inter sects where there are two large stone abutments on both sides of the path. Entry to the Starin Nature Preserve can be made via the top of the left abutment or through an at-grade entrance after turning left at the intersection and walking westward a short distance. The at-grade trail is a footpath into the undeveloped acreage, marked by a large concrete trapezoidal form. While walking through the Nature Preserve, privately-owned residential backyards on adjacent lots are viewable at higher elevations; future design recommendations may need to consider privacy concerns.

Currently overgrown with various plants, some of which are invasive plant species, the site is evidently not well tended to as there is much litter on the ground. Along the footpath, there is no lighting or seating, typical of a desire path, and there may be areas encroached on by tree branches and overgrowth. People generally use this space for exercising or walking their dog, but it appears to be less widely used compared to the paved rail trails within Minnesota Linear Park. On the other hand, Linear Park has more users, likely due to the presence of lighting, a few benches, and overall better maintenance and visibility of the area. Both the site and Minnesota Linear Park have issues with snow removal in the winter months, though less so for the latter. Workers plow the snow on the paved rail trail in Linear Park, though not necessarily in the areas surrounding it. This makes it difficult to access the park particularly for those with mobility issues. As for the site itself, snow is not cleared, and those who wish to utilize the space must essentially create their own path by trekking through the snow. The unmaintained path can also pose a safety concern during the spring season with wet ground and in the fall season with leaves and other organic debris.

When the site was used as a rail line, two lines converged and required an upper and lower track portion. The remnants of the abutment for the upper rail line remain at the eastern end of the property, and a raised mound exists along the northern length. The southern length elevation is sig nificantly lower, and in some places there exists a sizable depression between the two extents. If the site were to be considered for a trail, there would need to be significant accommodations made to bridge the disconnect between the northern and southern elevations for ease of traversing the site. In consid ering equitable and accessible trails and greenspace, special attention will need to be directed to the safety and mobility concerns for people of all ages and abilities in their use of the property.

Starin Nature Preserve Site Vist

Starin Nature Preserve Site Vist

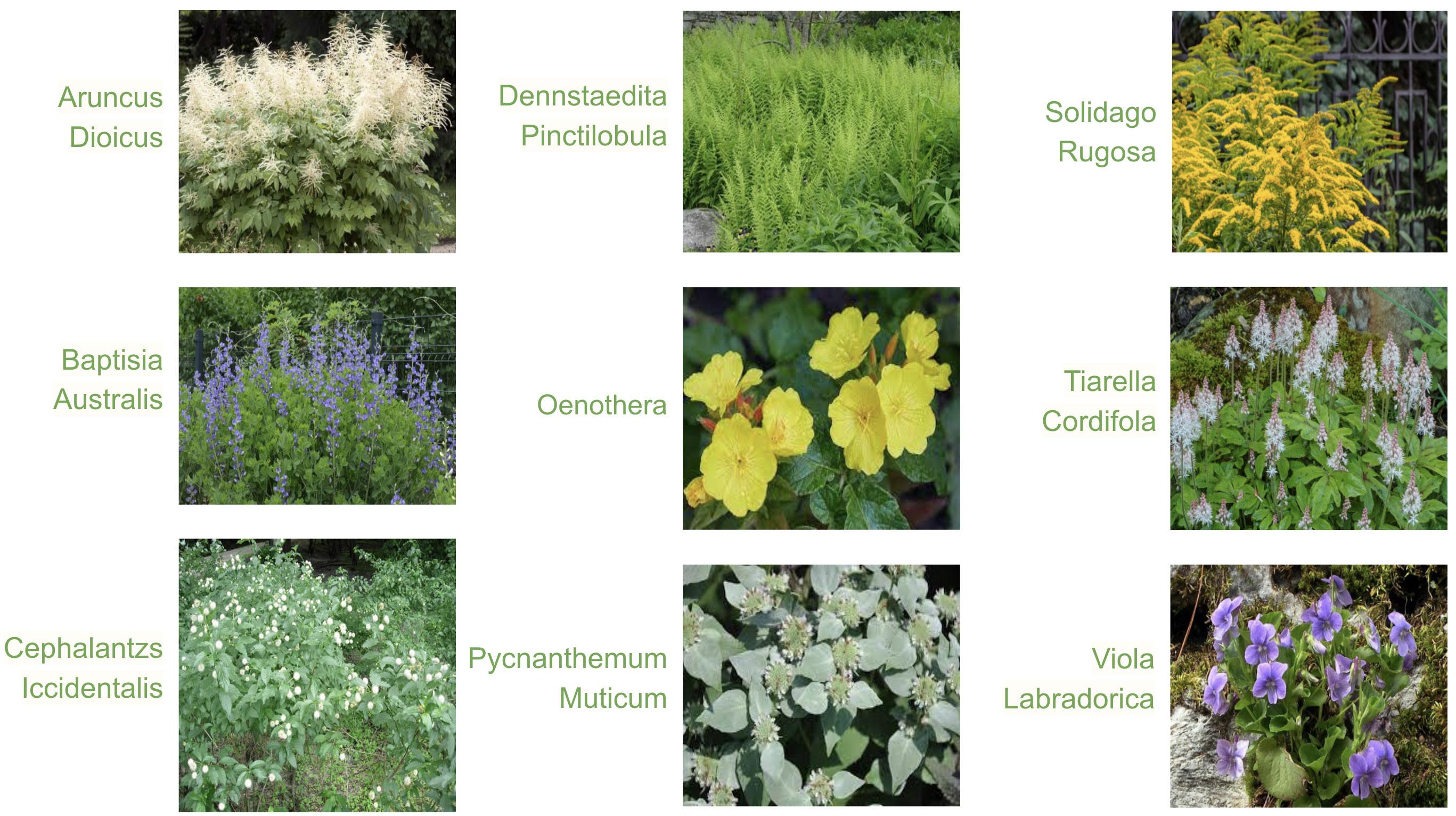

Buffalo consists of many native plants and trees that can be used for our final project.8 For instance, native tree species include Red Maple (Acer rubrum), River Birch (Betula nigra), and American Beech (Fagus grandifolia). Not only do all three of these trees provide bird habitation, but they also provide other uses and benefits including tolerating pollution, growing well in wet areas, and providing shade, respectively. These trees play a very important role in protecting Buffalo’s urban forest, which would be a great asset for the University Heights neighborhood. There are also vacant spaces around our site where trees could be planted along the streets and parks of the area.9 Native plant species of Buffalo also include plants such as Evening Primrose (Oenothera) and American dog violet (Viola Labradorica), which can be used to bring color into the natural landscape. Some common birds in Western New York include the following: Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata), Amer ican Robin10 (Turdus migratorius), and Red-Winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus). Encouraging these birds to inhabit the area and making it easier for them to do so would increase vegetation and balance the ecosystem of the site.

Native Plant Species of Buffalo, NY

8 Western New York Guide to Native Plants for your Garden. Buffalo Niagara Riverkeeper. (2014). https://drive.google. com/drive/folders/1bod2Z5WdPc3ONSmKAV81O6oqrY8N4K2h?eType=ActivityDefinitionInstance&eId=4c59e609-f24a44aa-a744-9263ccb4341d.

9 Native Plant Guide. Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper. (2022). https://bnwaterkeeper.org/projects/nativeplantguide/.

10 American Robin. All About Birds. (2019). https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/American_Robin/id.

Census data can provide insight into the demographics and economic makeup of an area. Using Social Explorer and U.S. Census Bureau data, we gathered key demographic information for the census tracts that surround the Starin Nature Preserve in the University Heights district of North Buffalo. The site is contained within tract 45 of Erie County, NY and is bordered by tracts 80.02 and 80.03 to the north; tracts 46.01 and 47 to the east; and tracts 51 and 48 to the west. For consistency, all data was collected using the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates as the most recently available census data.

Although the data is recent, there have also been major economic shifts due to the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic. Survey data provides a solid foundation on which to better understand a community through quantitative research, but it may not accurately depict the truest or most current representation of community values and demographics. Therefore, it is imperative that we actively and directly engage with the community to account for shifts in socio-economic status not represented by this data, and to reflect the principles of inclusive planning.

The site is predominantly White and Black, with a small percentage of Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander and other races. According to the U.S. Census Data, 87% of residents in tract 80.03 are White, while other races such as Asian, African American, and Native Hawaiian only collectively comprise 13% of the tract. 99% of the population in tract 80.02 are White residents.11 Almost all the data collect ed shows that the White population around the study area is significantly higher than all other races, excluding tract 47. That is because Tract 47 is located east of Main Street, which is where 85% of Black Buffalonians live. This is due to Buffalo’s history in housing segregation that still persists today.12

11 Race, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https://www.socialexplorer.com/ a9676d974c/view.

12 A City Divided, A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo. A. Blatto. (2018). https://ppgbuffalo.org/files/documents/da ta-demographics-history/a_city_divided__a_brief_history_of_segregation_in_the_city_of_buffalo.pdf.

13Nearly all of the census tracts we collected data from have more women than men, though the difference is not too significant. Overall, 51.8% of the population in the selected census tracts are women, while men comprise 48.2% of it. Of all the census tracts, tract 80.03 has the smallest gap between the number of men and women with a difference of only 80 more women. Meanwhile, tract 80.02 has the largest difference of 440 more women. It is interesting to note that the two cen sus tracts are adjacent to each other; In addition, tract 46.01, which encompasses the western half of University Heights, is the only tract to have more men than women with 148 more men.

FIGURE

Most residents living around the study area re ceived a high school degree, a bachelor’s degree, and a master’s degree. Based on tracts 45, 46.01, 48, more than half of the population obtained bachelor's and master’s degrees. Conversely, 64% of the population in tract 47 received some col lege education obtained or a high school degree. Overall, the percentage of educational attainment of the selected census tracts appears to be simi lar.14

Since tract 46.01 is located within University Heights, it is likely the reason why it is the only tract to have an obvious majority of 18-to-24 year olds. Tract 47 also has university students living there, but there is a noticeable increase of young adults aged 25 to 34 as well as middle-aged adults aged 35 to 54. These residents are possibly local Buffalonians, and the increase is likely due to the greater distance away from UB South Campus. Tracts 45, 48, 51, 80.02, and 80.03 have relatively similar age demographics, and there tends to be more young and middle-aged adults. Overall, 25to-34 year olds are the most common age demo graphic when looking at the data as a whole, and there are similar numbers of college age students as well as people in their 30s, 40s and 50s.15

13 Sex, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https://www.socialexplorer.com/ a9676d974c/view.

14 Education, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https://www.socialexplorer. com/a9676d974c/view.

15 Age, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https://www.socialexplorer.com/ a9676d974c/view.

Median household income is a good indicator of wealth within a community. In 2019, the median household income for Erie County was $58,121, with the City of Buffalo reporting a median household income of $37,354. The average median household income for the 7-tract study area is $57,173, which is 1.65% lower than the county and 41.9% higher than the city. Within the study area, tracts 47 and 51 report ed the lowest median household incomes with $39,440 and $44,163 respectively, and both were higher than the city median household income. Tract 47 likely houses many college students who may hold part-time jobs, have limited income to report, or living on loans. Tract 51 has older established neighborhoods and includes the Holling Homes development, a property of the City of Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority. This tract is also home to the newly developed Rachel Vincent Way with residential infill development that may not have been included in the 2019 estimates. The highest income reported was found in tract 48 with a median household income of $76,270. This tract cov ers a significant portion of the commercial district on Hertel Avenue that boasts a variety of locally owned businesses, restaurants, and retail shops.16

FIGURE 7. Median House Incomes

individuals are White. In most of the census tracts, the second highest reported racial demographic of employed people are Black or African American, but this population is significantly smaller compared to the number of White employees. The only exception is census tract 46.01, where the number of Asian em ployees is slightly greater than the number of Black or African American employees. There are no reported Native Americans or Hawaiian employees residing in areas around our site. When comparing the data sets of 2014, 2016, and 2019, the employment rate appears to steadily decrease. The only exception lies in census tract 46.01; While the number of employed workers is still less than it was in 2014, it is greater than that in 2016. When comparing employment by sex, the number of male and female employees are relatively similar. For instance, census tracts 45, 48, 51, and 80.02 have more male employees, but tracts 46.01, 47, and 80.03 have more female employees. Overall, the percentage of male and female employees are relative ly equal with less than 10% difference for all census tracts, with the highest difference in tract 80.02 of 9%.17

It is important to know the employment rate of a community to better understand the condition of the operating economy and get insight on the city’s labor market. In all census tracts, at least 75% of employed

Trails and greenspaces are essential for numerous rea sons, with community health being a major one. Phys ical inactivity and chronic diseases are becoming more prevalent in the U.S. When COVID-19 caused every one to quarantine at home, people had less opportu nities to exercise and relax in nature. If people did go outside, it was difficult to maintain social distancing even in public parks sometimes due to the sheer num ber of people and the insufficient supply of greenspace. Despite the world slowly returning to ormalcy, there is still an increased demand for further expansion and investment in trails and greenspace. A few of the many benefits of trails include better access to the outdoors and increased physical activity, which can help combat conditions such as coro nary heart disease and obesity.18

According to the Trust for Public Land (TPL), Buffalo is ranked 38 out of 100 ParkScore cities in

16 Median Household Income (Inflation Adjusted Dollars), Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https://www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/view.

17 Labor Force, Civilian, Employed, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https://www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/view.

18 BRFSS 2019, 2018. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). ACS 2018 (5-Year Estimates). Places, Local Data for Better Health. (2022). https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/22c7182a162d45788dd52a2362f8ed65.

the U.S. It is based on five characteristics of an effective park system: access, investment, acreage, ame nities, and equity. The city of Buffalo has partnered up with the TPL to create a master plan that will set the course of parks in Buffalo for now and future generations. The main goal of this plan is to have a park and/or public greenspace within a 10-minute walk (1⁄2 mile) for every resident in the city. As of right now, about 89% of Buffalo residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park, while the national average is at 55%. It is also important to note that there is a race and income disparity in regards to this statistic. Residents in neighborhoods of color have access to 8% less park space per person than the city median and 53% less than those in white neighborhoods. In addition, residents in low-income neigh borhoods have access to 8% more park space per person than the city median and 15% less than those in high-income neighborhoods.

Our focus area in the University Heights neighborhood is vital in increasing our percentage of residents living within a 10-minute walk of a park, as there is very little to no space available anywhere else in the immediate area due to dense residential neighborhoods. Within our focus area, there is am ple room for certain amenities that would increase our ParkScore. Such amenities include basketball courts, a dog park, playgrounds, and a splash pad/sprayground. If we can include these amenities in our area and transform the site into an active public park, it will decrease the high-priority focus area that was highlighted in a map provided by the TPL by almost half. This site needs to be protected in order to move our city up in the rankings, and make it a better place to live no matter what neighbor hood you end up in.

Data suggests that coronary heart disease and obesity are concerns in the census tracts including and surrounding the site, particularly the latter. Estimated prevalence rates for coronary heart disease for adults aged 18 years and over range from 4.2% to 5.7%. However, the rates are much higher for obesity and physical inactivity. Tracts 46.01 and tract 48 have the lowest estimated prevalence rates of 26.9% and 27.9% for obesity, respectively. The highest two prevalence rates for obesity are 37.4% and 34.9% for tracts 47 and 51, respectively. As for physical inactivity, the lowest estimated prevalence rates come in at 18.9% and 19.8% for census tracts 48 and 45. Similar to the statistics for obesity, tracts 47 and 51 have the highest prevalence rates of 30.2% and 27.3%, respectively.

Not only do trails and greenspaces allow people to enjoy the natural environment on a mi cro level, but they can also improve community health on a larger scale by improving access to the outdoors. Therefore, preserving and developing the Starin Nature Preserve into a trail has immense benefits for community health in the surrounding neighborhoods, and it can connect to the existing Minnesota Linear Park and further connect existing trails.

19Considering the community that will benefit from the Starin Nature Preserve, it is important to know which neighbors are more likely to commit to its long-term maintenance and care versus those who may enjoy it only briefly. Understanding the relationship of owner-occupied and renter-occupied households may enable a more targeted engagement process to determine the design qualities and community values that each type of household is more likely to respond to. In 2019, owner-occupied households made up 64.58% of Erie County households and 40.72% of households in the city of Buffa lo.

19 Housing, Renter Occupied, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https:// www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/view.

The 7-tract study area surrounding the Starin Nature Preserve has an average of 61.27% for owner-occupied households, which is 5.3% lower than the county average but 40.3% higher than the city average. Tract 80.03 has the highest rate of owner-occupied households with 88.34%. On the oth erhand, tract 47 has the lowest percentage of owner-occupied households of 29.64% due to the higher student population.

Renter-occupied households account for 38.73% of households, which is 8.9% higher than the average for Erie County and 41.9% lower than the average for the city of Buffalo. Tract 80.03 has the highest rate of owner-occupied households as well as the lowest percentage of renter-occupied house holds of 11.66%. The inverse is true for tract 47, which has the highest rate of renter-occupied house holds of 70.36%. Tract 46.01, which borders University at Buffalo’s South Campus, has the most even distribution of renter- and owner-occupied households with a near 50-50 split.

It is important to note that green gentrification and displacement are possible with our plans to preserve and develop the site. The addition of trails and greenspaces can lead to an increase in surrounding property values and rents. People looking to buy homes in the neighboring areas around the Starin Nature Preserve may find it difficult to afford it, and rental households may be particularly affected. Considering the site is in University Heights where a significant number of UB students rent housing, it may cause students to be unable to afford to live there in the future. It is our hope to avoid this issue by implementing equitable community engagement strategies.20

The location of the site is significant in that it lies between University Heights and North Buffalo. This offers a unique opportunity to bridge historic physical and social barriers between these two commu nities. Combined with the state’s current initiatives on expanding trails and greenways, this is a partic ularly pertinent time for the site to be preserved.

Currently, the majority of the University Heights neighborhood is located in an N-3 zone, which is considered an urban neighborhood according to Buffalo’s Unified Development Ordinance (UDO). This zoning code applies to neighborhoods that were originally designed when the streetcar was the primary form of transportation, so it has a classically dense feel to the neighborhood with a mix of both commercial and residential properties. The neighborhood also contains the following zones: D-IL, light industry that popped up around railroads; N-4, single family residential; D-E, educational campus; N-1, urban core; and D-OG, open space. The site itself is zoned D-OG, meaning there are more parks, civic green spaces, or publically accessible areas with trees and landscape framed by an element such as a building facade, trees, or a fence (Buffalo NY, Zoning Map).21

A community asset is a resource that improves a community, and it can include individuals, associa tions, institutions, physical space, exchange, and culture or history. In the case of our project, commu

20 Housing, Owner Occupied, Census Tract 45, Erie, NY. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Social Explorer. (2019). https:// www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/view.

21 Zoning Map, City of Buffalo, Unified Development Ordinance. City of Buffalo. Mayor’s Office of Strategic Planning. (2017). https://www.buffalony.gov/DocumentCenter/View/6105/Citywide_Zoning_Map_January2017?bidId=

nity assets include the University Heights Collaborative22 (UHC), the Tool Library, and the University at Buffalo (UB). The UHC is a community-based organization that fosters and promotes the well-being and cooperation of the neighborhood. It is composed of residents and other groups, such as local block clubs and neighborhood watch groups. The UHC consists of committees involved in beautification, business involvement, communication, neighborhood watch, and landlord outreach. It is a helpful resource because its board consists of residents in the neighborhood, so there is a direct line of com munication with people in the community. Because the UHC also consists of block clubs, we can reach smaller organizations in the community as well as reach more residents that are not necessarilyaffiliat ed with these groups.

The Tool Library23 is a non-profit organization that lends tools for a small annual fee. Anyone in Buffalo or in nearby suburbs, both homeowners and renters alike, can sign up for a membership with the Tool Library. However, considering many households in University Heights consist of shortterm renters, particularly college students, it is especially helpful for University Heights residents to have a place where one can have access to tools that may not be needed for regular use. Rather than buying expensive tools that will only be used once or a few times, people can borrow tools as needed and save money. The Tool Library is home to numerous types of tools, and people can borrow tools needed for anything ranging from simple at-home DIY projects to larger scale events, such as neigh borhood clean-ups and tree plantings.

UB is also a highly valued asset to the University Heights neighborhood, along with its faculty, students, and this studio. This studio aims to focus on equitable community engagement before devel oping design plans for the site, which is not always practiced in the field of environmental design. In addition, the students are also great assets because of their passion for helping the community. In fact, the April clean-up event had an incredibly high turnout, with a majority of the attendees being UB students.

With these community assets, we were able to network and reach community members that know the neighborhood and site well. For instance, we met with UHC board members and were able to get a better sense of the dynamic between longtime residents and student renters. In addition, we utilized tools from the Tool Library for the highly successful clean-up event. Despite the existence of these great community assets, there is a disconnect between longtime residents and student renters. It is not unheard of for older local residents to report negative interactions with college students, and it has contributed to strained relations over time. However, considering a majority of the clean-up event attendees were also UB students, this demonstrates their desire to connect with and help the com munity. We hope that this project can open a dialogue and improve communication between the two groups, as well as allow them to work together in deciding the fate of the Starin Nature Preserve.

According to 2019 ACS census data, there is an obvious majority of people who drive a vehicle to com mute to work. Census tract 80.02 has the highest estimated percentage of people who drive a vehicle to work with a rate of 93.9%, while tract 46.01 has the lowest rate of 71.2%. This discrepancy is possibly due to tract 46.01 being more likely to have more student renters, and college students are less likely to own a car compared to working adults. Of the people who drive a vehicle to work, a relatively small proportion of them carpool. For most census tracts, the rate of people carpooling ranges from roughly

22 About. University Heights Collaborative (UHC). (2022). http://ourheights.org/about/#mission.

23 About Us. The Tool Library. (2022). https://www.thetoollibrary.org/about/.

5% to 8%. Interestingly, this figure is significantly higher for tracts 47 and 80.03, with a rate of 20.9% and 13% of people, respectively. Tract 47 is also home to a considerable number of UB students, so it may be the increase in college students that causes such a difference in this census tract. However, it is unclear why tract 46.01 has a noticeably lower rate of 6.4%. Public transportation rates are also highly variable, with the lowest of 2.2% at tract 80.02. There is a moderate increase in public transit rates in tract 51 with a rate of 7.6%. Tracts 46.01 and 47 have the most people taking public transportation to work, with estimates of 17.6% and 10.6%, respectively. Figures for walking and biking are even lower, though the former is slightly more popular than the latter. Rates for walking range from 0% 7.4% while rates for biking range from 0% to 2%. Interestingly, census tract 45 is the only one to have rates of 0% for both walking and biking, and it is also the tract that contains the project site. If the site were to be preserved and developed into a trail, these figures may increase due to better connectivity. Though not as many people rely on public transportation compared to personal vehicles, this would likely change if Buffalo’s public transit system were to be improved. It is important to have an effective public tran sit system to serve those who rely on it, but it may not be sufficient enough for those who do need it. Nearly 56,700 households in Erie County do not own a car. Not only are 67% of these households low-income, but also 2,000 of them are not located in an area with easy access to transportation. There is also a large difference when it comes to race and who is using this public transport. For workers earning between $35,000 and $65,000, 21% of workers of color use public transport compared to 3% of white workers. When comparing workers earning between $15,000 and $35,000, 29% of workers of color use it while 7% of white workers use it. For workers who earn less than $15,000 per year, 51% of workers of color use public transportation while only 8% of white workers use it. As annual wages decrease, the gap between the number of workers of color versus white workers utilizing public trans portation grows exponentially.

It is clear the city of Buffalo is largely dependent on single-occupancy vehicles, but there is still a sizeable portion of people who utilize non-motorized forms of transportation such as walking and biking. There is also a significant number of people who use more environmentally friendly motor ized modes of transit such as public transportation and carpooling. Having more trails and greenspa ces available may encourage people to use cars less, and perhaps more people would walk or bike to work.24

24 Commuting Characteristics By Sex, Census Tracts 45, 46.01, 47, 48, 51, 80.02, 80.03. ACS 2019 (5-Year Estimates). Unit ed States Census Bureau. (2019). https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=1400000US36029004500,36029004601,360290047 00,36029004800,36029005100,36029008002,36029008003&tid=ACSST5Y2019.S0801&moe=false.

“The North Buffalo Rail Trail is located adjacent to a 17 acre site of undeveloped greenspace. In re sponse to recent housing developments in the area, the desire among the community is to see this place preserved as greenspace in perpetuity and prevent any future development.”

-The University Heights Collaborative

Our first visit to the Starin Nature Preserve took place on February 7th, 2022. This visit was used as an introduction to the site and for us as future planners to get a better understanding of the terrain and community we are working with. Upon first observations, the site was covered in snow, as there was a fresh snowfall a few days prior. There were a few people on the trail when we arrived, and there was evidence of residents walking their dogs in the preserve as well, which allowed us to see how the neighborhood interacts with the preserve. We noted that there were also some privacy concerns, as the site rises above property fences, allowing users to look directly into the homes bordering the preserve. There were also some accessibility issues, as far as the abutments go. Overall, the site is in shape to redevelop these concerns.

Chris Kameck, a local artist and activist, provided us with a tour of the Riverline, which bleeds into the First Ward of Buffalo, NY. At this site, he provided plenty of stories and information about Red Jacket River Front Park and the surrounding areas. He told stories of how he interacted with the park and about how some of the residents in the First Ward also engaged with the space. The First Ward is next to Larkinville, an area that has seen significant private investment in recent years. The residents in the area are concerned of gentrification bleeding into their neighborhood.

To be specific, a high end apartment complex is being planned in an old factory next to Red Jacket River Front Park, which is receiving push back from the current residents in the neighborhood. The current residents are worried about being displaced from their neighborhood, some of which have lived there their whole life. It helped that we were able to talk to some of the residents who were walking their dogs or riding their bikes, allowing the class to gain perspective on the community itself.

The Riverline project itself is a nature trail and greenway linking Buffalo to the Buffalo River. This project has engaged with the community several ways. First, they held door-to-door surveying and canvassing the residents of the neighborhood. Another way they engaged with the community was painting a mural with children in the neighborhood. Lastly, they held live-meetings online with polls so the community could vote on designs for the project.

To prepare for our community clean-up, we began to clean up the Tyler Street Community garden and prepare it for springtime use. This was a previous community engagement project and is used as a community garden in University Heights. This was a hands-on introduction into project planning, and implementation. We talked through what the garden needed first, assessing the area, and then bor rowed tools from one of our community stakeholders, the Tool Library, to implement. We cleaned up the trash within the garden and the surrounding area. We also flipped the beds in the garden and did brush removal. This was just a small taste of what the Earth Day Clean-Up would look like and entail. We also used this as an opportunity to determine what tools we may need to borrow from The Tool Library for our clean up event at the Starin Nature Preserve and to understand what we would need to consider when organizing activities for a large-scale community event.

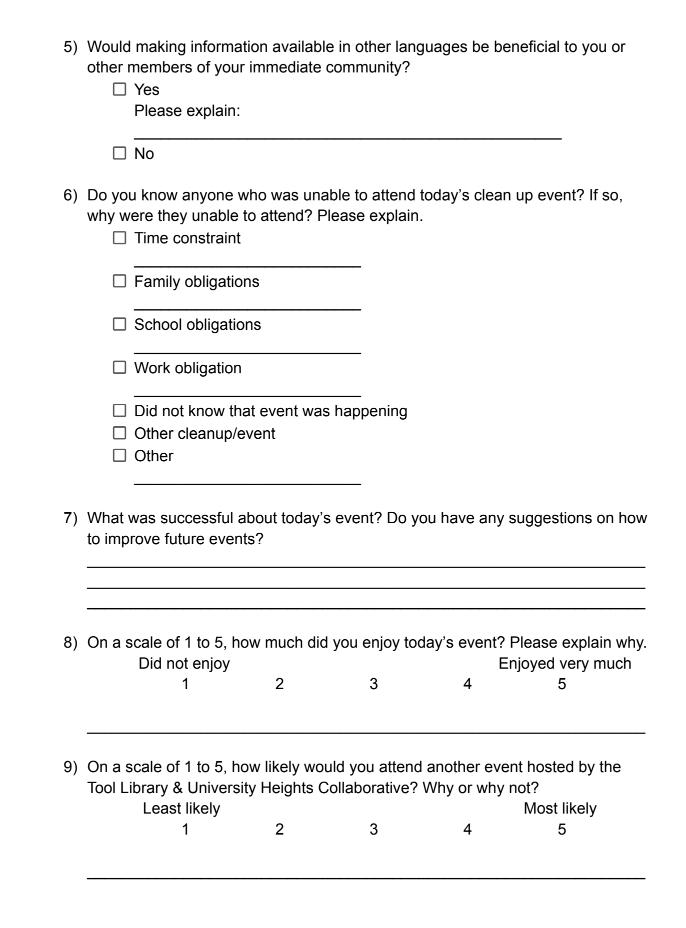

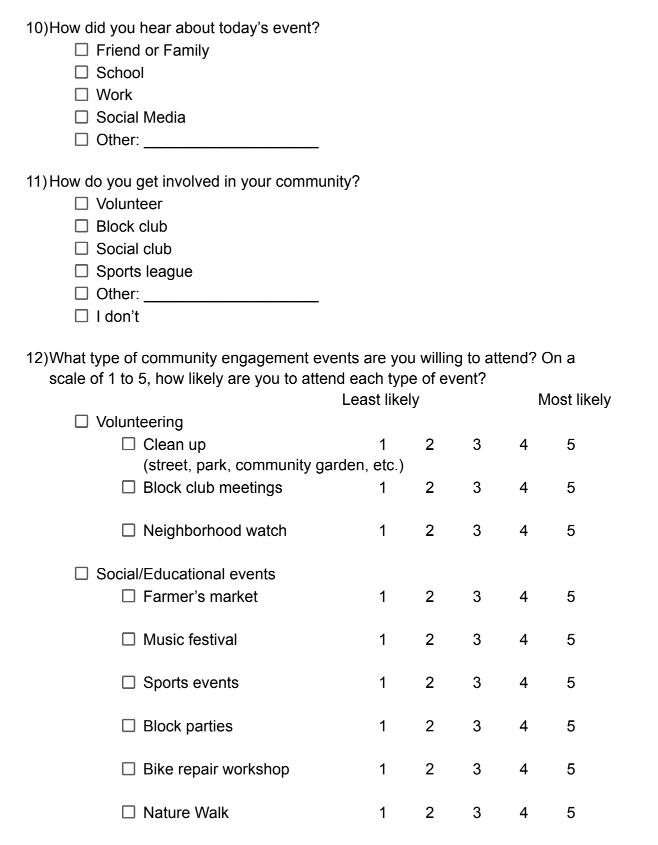

The Earth Day Clean-Up is our community engagement event, in which we cleaned up the Starin Nature Preserve and asked the community what they wanted to see moving forward. This involved cleaning up the site of debris and litter, trimming and removing brush, and engaging with the commu nity as far as what they would like to see done with the preserve.

During the clean-up event, we surveyed the participants. We asked a series of questions, involving age, sex, race, mode of transportation, etc. This provided an opportunity to pilot an actual community en gagement activity. We worked hard to make the proess inclusive by having a digital survey and a hard copy of the survey on site.

Of the 64% of surey respondents that claimed they do not utilize the space, the primary reason they cited for not using it was because they did not know it exsisted. This amounted to a whopping 57% of responses citing this reason. 26% of them claimed that a lack of accessible trasnit was the pri mary reason they dont use the space.

We found that most of the community would prefer being notified about events and future activities by email or social media. A very small minority of people would prefer in-person meetings as opposed to these methods. This, along with mailers, prooved to be the least popular form of engage ment. Lying somewhere inbetween the line of popular and unpopular was texting as a form of engage ment - coming in with a score of 13%.

From the collected survey results, we found that 50% of participants who arrived at the Earth Day Cleanup event drove to the location. This means that 21 out of the 42 responses indicated driving as a form of arrival. This signifies that driving to the rail trail may serve to be a popular method of transport in the future. Out of the 42 total responses, the second most popular form of transport to the site was biking which amounted to 13 of the 42 (31%) of participants. This was a pleasantly surprising figure - indicating to us that the rail trail seemed to be incentivizing this method of transport. Coming in next was public transit. This method, although ranking third in popularity, ended up showing a sig nificant drop off in users as opposed to driving and biking, This method of transport ended up scoring 5 out of 42 users which amounts to a 12% popularity score. Finally, walking prooved to be the least popular method of arrival at our Earth Day event only coming in at 3 out of 42 users (7%).

Our survey suggests that residents like to use the rail trail primarily for enjoying nature and relaxing. This amounts to 40% of the 36% of respondents who do utilize the space. The second most popular reason for using this space was for exersize.

Jajean Rose-Burney from the Western New York (WNY) Land Conservancy helped us develop ideas as far as their community engagement and processes from their work. First, they suggested meet ing with the community you are trying to plan and impact before the media makes them aware. By starting with traditional in-person methods, the community gets a more personal engagement experi ence. Surveying residents is also an impactful way to get a sense of how the community feels about and wants from the space, especially from a data standpoint. To gain momentum on the project, it’s recom mended to do direct community improvement events, much like our own community event.

Jennifer McQuilkin gave beneficial insight into Human-Centered Design. Using this strategy, we conceived of the idea for user personas, which will be mentioned later in this report. Through de veloping user personas, we can begin to understand the needs of the community, define problems and barriers, ideate possible solutions, test solutions, and collect feedback. She was very helpful in fleshing out the different types of people who may be interacting with the community and the site, and how we can appeal and be inclusive towards them.

Meeting with our main stakeholders, the University Heights Collaborative was a crucial part of getting involved in the community engagement process for our site. Our meeting with the UHC consisted of interacting with Stephen Arlington, Mike Cartright, Linda Garlow, Candy Hayes, Dayna Overton-Burns, and Raymond Reichert in order to gain a wider perspective of the study area at hand.

The idea of equitable community engagement is a recently created term in the realm of urban plan ning and design, but it is one that has gained a lot of traction since its inception, and it is rare to find a modern public plan of any kind that does not include this concept. We, as a society and especially as planners, have come a long way when it comes to approaching community engagement in a more in clusive way, and the results have been almost universally positive. Because this concept is so fresh, it is vital to gain an understanding of what works and what does not work in the planning process, which is why we need to focus our efforts on recognizing and understanding what type of barriers may exist in the process that ultimately exclude certain demographics of people. It is important to realize that just because we are open to the opinions of the public, this does not necessarily mean that the public knows how to become involved. For our project, we actively researched and hypothesized as many barriers in as many demographics as possible.Next, we created solutions to mitigate these barriers to equitable engagement. Here we will highlight the most common barriers in participation that community mem bers could face using research from previous studios, engagement plans from various cities, as well as our own findings throughout the semester.

To gain a better understanding of possible barriers in community engagement, our class utilized user personas that were created by a previous studio class and also created our own user personas to help us gain perspective of possible users of our study area. Developing user personas is highly beneficial in comprehending various behavior patterns, goals, skills, attitudes, and background information of demographics that we otherwise knew very little about. Developing user personas is also a way to help designers build empathy in order to gain a perspective similar to the user. Creating user personas can help designers see beyond their own perspective and recognize that other people have unique needs and expectations. By thinking about the needs of a fictional, yet relevant, persona, designers may be better able to infer what a real person might need.

21 year-old UB student; Recently moved into a house in the University Heights neighborhood that she is renting with some of her friends

Uses the site to travel to and from UB’s South Campus; uses the site as a place for exercise and likes to run there

Lack of proper lighting

The site lacks the proper space to take part in exercise activities that will not obstruct people using the trail

Increased interactions between her and her neighbors Additional programming that appeals to her age group/demographic

Lacks a connection to her neighbors and the community due student status

More lighting to make space safer

American Robin, which is a common bird throughout the continent that can be found in various outdoor environments and climates

Using the site for nesting, as a place to forage for berries and worms, as a pick-up spot for attracting a mate, and as a place to show off his lyrical abilities

Community lacks knowledge Wildlife lacks a voice

To maintain the environment and keep clean More attention for wildlife

Lack of positive interaction between site users and the wildlife

For the use of pesticides and herbicides at the site to be eliminated

73 year-old Navy veteran that currently lives at the VA hospital located on Bailey Ave

Uses the trail for strolls with his grandchildren and as a place to observe the wildlife present

limited to handicap-accessible infrastructure Struggles to attend meetings that are in person but is not completely familiar with current technologies

More programming available at the site for all age groups

More amenities at the site as well as those that are ADA accessible

immunocompromised due to his age

More variety in the platforms in which meetings are held

30 year-old mother of three kids and recent Laotian immigrant to Buffalo, Non-native English speaker

Uses the trail for walks with her children and as a pass-through to get to nearby stores

Speaks English but cannot read or write

Access for strollers and restrooms

Works evenings and is unable to attend community meetings

A place to relax and enjoy family and friends

Does not understand how she can get involved with the community

Multilingual signage with visual icons

32 year-old wife and mother of three that recently moved to the University Heights neighborhood from Colombia

Has not yet visited the site and has only seen the site in passing because she and her family are new residents to the neighborhood

Is a non-native English speaker

Busy family life afffects attendance

Lack of community connection & knowlegdge of events and the site

Informing non-native English speakers about existing & upcoming resources

50 year-old Caucasian woman with 6 year-old daughter who chose to give up previous job for daughter’s wellbeing

Lives in Minnesota Linear Park’s homeless settlement with her daughter

Lack of motivation to participate in events

More information about the park

Too busy finding daily supplies for her daughter and herself

More signage of assistance for homeless individuals

Lack of connections with other members of the community

Community activities that are geared towards her daughter’s age range

Multi-lingual engagement options

Opportunities to build connections

10 year-old Public School student, enjoys video games, lives with his Mom and sister in University Heights

Uses Barriers Desired Outcomes

Uses the site for sledding in Winter, meeting friends afterschool, and walking on family outings

Lack of lighting at night

Mother worries about safety

Age-appropriate programs and groups Ability to play safely

Lack of youth programs and time constraints

The most common barrier to equitable community engagement is a general lack of understanding of how to get involved in the planning process. This lack of awareness is most often caused by issues in communication between the planners and the public.

Signs are invaluable for parks, trails, and greenways. They make spaces interactive, convey information, create safer environments, and help users find their way. There is currently limited signage in the park, and it can deter individuals from using this space and automatically excludes those who are not aware that the park exists.

Youth: There is little done to involve the youth in the engagement process; meetings can be boring for children, and community events, such as clean-ups and plantings, are difficult for children to do, espe cially without adult supervision.

Elderly: It is difficult to engage this demographic when events are announced via social media and/ or other forms of social media. There is also a barrier in the UHC meetings themselves in that they are done primarily online.

Flora and Fauna: There is a lack of education and awareness in regard to the plant and animal spe cies both native and non-native that are found in the park.

Utilizing Public Dpace: This space is open to the public yet it is scarcely used for public events through community members, the University at Buffalo, and many other organizations in the area.

Lack of Service Events: Although there are various clean-up events throughout the year, there needs to be a great deal more– the community does not get much help from the NFTA or other city workers in regard to cleaning this space and removing large and/or potentially hazardous debris.

Lighting: The park has two tiers; the only light posts are along the lower level’s east side path- this barrier prevents users from being able to use the space at night, a time when many people use the park as a shortcut to get to various destinations.

Limited Security: there are a couple cameras present on the property but they have limited view and the video feed is low quality.

Privacy Concerns: Asking for personal data could make residents fear that they could be a victim of discrimination or experience a threat to their livelihood, so it’s important to be transparent about why you want particular information and explain how it will be used.

Steps, curbs, and lack of paved pathways/trails prevent access to people who use wheelchairs. Lack of handrails on any of the trails’ inclines is also problematic for ADA as well as disabled and elderly indi viduals.

The park has close to 2 miles of paths/walking space and only a handful of benches or areas to rest. There are no benches on the top levels of trails which can be problematic for disabled and eldery indi viduals using the space.

There are issues regarding overgrown trees, bushes and grass impeding the trails, as well as an ac cumulation of trash throughout the year, a lot of which is dangerous in nature (drug paraphernalia, sharp objects, rope and wires to trip on, etc.). During the winter months the snow removal is sparse or non-existent, making it difficult and sometimes impossible for park goers to utilize this space.

Unlike the rest of the park, which has multiple access points, the western neighborhood has very few areas to enter the park due to houses and fence lines impeding the way.

There is a lack of signage, both temporary and permanent throughout and surrounding the park–many people do not know that this park exists, and navigating the trails can be difficult to new users.

People who spend less time online and have lower digital capability may not be able to participate in online community engagement and communications efforts effectively.

As much as community members would like to be involved, many of them just do not have the time to do so, especially when planning meetings and events are held during the day. People who are employed can also find it difficult to attend during work hours.

Parents and caregivers can find it difficult to participate in face-to-face engagement events, especial ly during the planning process, as it may be difficult to find child care and can be expensive to hire a sitter for those who are financially strained.

Aside from the neighborhood to the west, there is a general difficulty in being able to access the park, especially during the winter when most of the access points are buried in snow. There are no maps posted on any of the current signage, there are very few signs that point in the direction of the park

rom the most commonly used streets (Main Street, Starin, Kenmore Avenue), and in the park, the lack of wayfinding signage is an issue in that the space is not perfectly straight and can get very confusing.

Short Term: This demographic mainly refers to college students living in the area who may not feel the need to be involved in the engagement process because they will not be living here long, or that they do not have as much empathy for a space that they barely know. The student population may also face discrimination barriers due to the history of students in the area being disrespectful of the space (littering, vandalism, noise complaints, etc.)

Long Term: The effects of the short-term residents may also create a barrier for long-term residents because they may think it is not worth the trouble to create a space that may inevitably be abused or destroyed.

It’s important to understand the various languages that are spoken within a community and offer mul tilingual services so that people can interpret and engage with materials in their preferred language. Matching the right language level for the audience is equally important.

People may not be able to take off of work or do not have the discretionary income to participate regu larly in community meetings as a volunteer.

The University at Buffalo has created events for the public but has historically only hosted them on UB property and have not utilized other public space, such as the rail trail park.

Based on our survey responses, many people are not aware of the site itself or events which the community holds. An example of how awareness can impact a project is the t-shirt design created by the studio as a logo for the Earth Day clean up event. Creating a recognizable brand for the service event helped bring more attention and awareness to the event and introduced the site to the com munity as an identifiable asset, even without an official title.

Considering there is not an official name for this project or site, it can be chal lenging for people to identify and locate it. It is highly recommended that one of the first courses of action be naming the site. Allowing the location to be easily identifiable will bring more awareness to the site and the project. Create a unified project and community brand. This will be beneficial to identify the community group and get people engaging with the members.

Collateral materials should be created explaining the “who, what, when, where, and why” of the proj ect. This could be listed on flyers, postcards, or other print and digital materials. The next step would be to create a mailing list of the residents that would like to be involved in the project. This can be done by collecting emails and addresses at neighborhood events and meetings.

The collected contact information can then be used to keep everyone notified of upcoming events, meetings, and plans for the site. A presence in news stories, web pages, and social media would also be beneficial in spreading information and attracting engagement with the community. It is important to be respectful of the community by allowing them to be the first to hear of, review, and vote on plans before it is shared by larger media outlets.

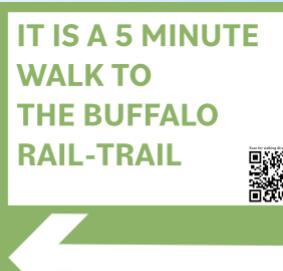

“I Love Public Parks” Earth Day Tree created by Julia BertoliniSignage, both on and off the site, is crucial for attracting people to engage with the site. Accessibility concerns can be addressed by providing easy-to-read signage to properly direct people to the site from major travel corridors, like Hertel Avenue, Main Street, Kenmore Avenue, and Starin Avenue. It would be beneficial to have the site added to local, regional, statewide, or national maps of trails.

Temporary signs and posters would be a great way to test the efficacy of signage to determine if it would bring added awareness to the site. WalkYourCity.org has temporary signs which are easy to in stall and help users better understand the spaces around them. These could be placed along the major travel corridors mentioned above in addition to places along the Rail Trail. Temporary signage is a cheap and easy way to run a trial to determine the need for signage, appropriate placement locations, and improve messaging until there is long-term funding available for the site.

Wayfinding signage can go up to direct people to the site. There can be scannable QR codes which lead to maps, websites or additional information.

This can include directions to the location, information about the site, along with educational signage. There can also be updated and newly created maps to inform users on the physical space, paths, addi tional information and park amenities. This can build upon the existing information that is exhibited along the Rail Trail. These could provide information regarding flora and fauna.

Bulletin boards at the crossroads of Linear Park and the Rail Trail are also recommended. These could be used for groups involved with the site, like the UHC and Tool Library, to share their information and for the community to share their knowledge. For example, if someone wants to put up a business card or a flyer for a local event.

Some examples that could be used are nature walks and Flora and Fauna events conduct ed by the Buffalo Audubon Society, where the community can get educated on the wildlife in the area. This can include information on the ecological research done for the site about native plants and the revitalization and preservation of the native ecology or the use of pesticides and herbicides.

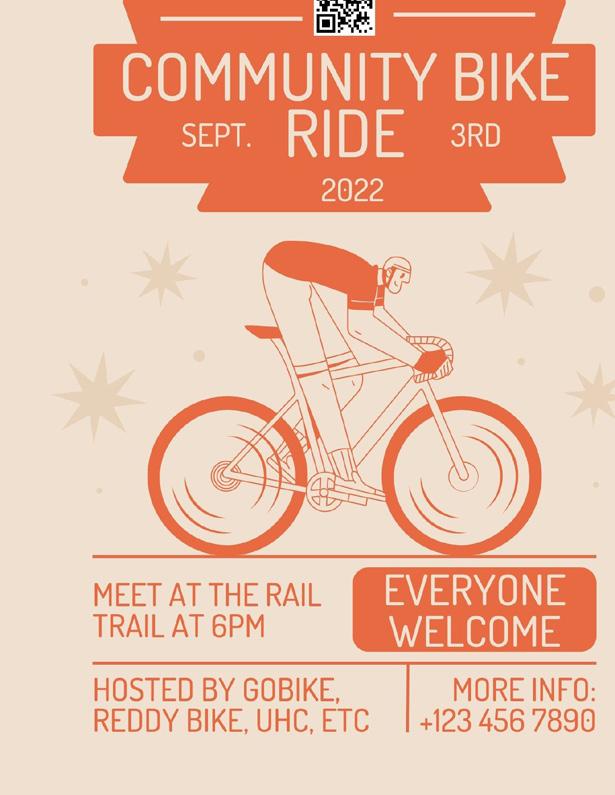

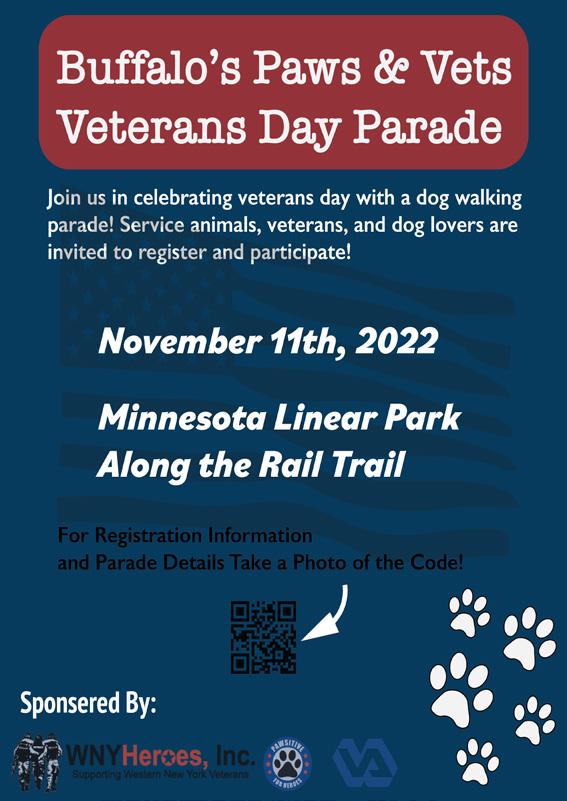

Public and community outreach events hosted at the space may include: public art exhib its, created and shown by local artists; pet parades that could be charitable events to aid with local not-for-profits, and in partnership with the VA Hospital; and rummage sales or farmer’s markets, also in partnership with charitable organizations or to provide maintenance funding for the site. A final suggestion is to host annual clean-up and service events at this location to build on the momentum of the recent Earth Day Clean-Up event. To appeal to all ages, it is recommended to include youth programming that could include tactile projects such as building bird baths or box es; and senior programming to promote health, wellness, and social networking. Each program also provides an opportunity to solicit additional feedback on the prospective design and imple mentation of the project site. ‘Pup Parade’ is a great way to celebrate veterans and have a fun event of dog walking which not only includes veterans and their service dogs, but other pets as well which will help celebrate and raise money for those who served our country.