Copy Editing + Proofreading

Amanda Amour-Lynx, Mel Compton, Stephanie Jeremie, Belinda Kwan, Jess Murwin

Distribution

imagineNATIVE Film and Media Arts Festival, Indigenous Youth Roots, InterAccess

Exhibition Partner InterAccess

Administration

Jess Murwin

Design + Layout

Amanda Amour-Lynx, Sol Higgins

Contributing Artists

Amanda Amour-Lynx, AKASOLEIL, Samay Arcentales

Cajas, Mel Compton, Nico La Liberté-Cozzens, Nishina Loft, Sheri Osden Nault, Thomas Robertson, Rihkee Strapp, Sydney Wreaks, Emily Wright

Contributing Writers

Amanda Amour-Lynx, Rihkee Strapp

I hope this exhibition booklet finds you well, as the cliché goes. Actually, I hope it finds you somewhere better than here. I hope the expanse of time between now and a better world for us, is indeed not so long. And that times to come hold something bright for future-makers and builders like yourself.

I find myself at the intersection of two spirit joy and watchful protectiveness over our relations. I revere and witness the earth trembling beauty found within the gift of our awakening song, our collective voice warms the skies and promises bright new vision, stories and truth-telling.

Soaring high above as guardians, the thunderbirds open doorways in all directions, lovingly guiding us through pathways towards ways and

I love you. I love what you are becoming. You are standing tall and strong in your convictions.

Our stories are no longer asleep. You know your worth, you are so much stronger than you were before. You have made so many choices to arrive where you are at today and they were without a doubt far from simple, required you to persevere and believe things will get better without actually knowing if they would.

May the stories we tell be a manifesto for the two spirit future we will create. Let us offer thanksgiving to those before us who left footprints for us to learn from, who spent their days teaching others how to love us better. May the cosmos hold all of you, and see all that you are, for always.

THE ONE WHO LEAVES FOOTPRINTS Jilaptoq

Our stories are no longer asleep. May the cosmos hold all of you, and see all that you are, for always.

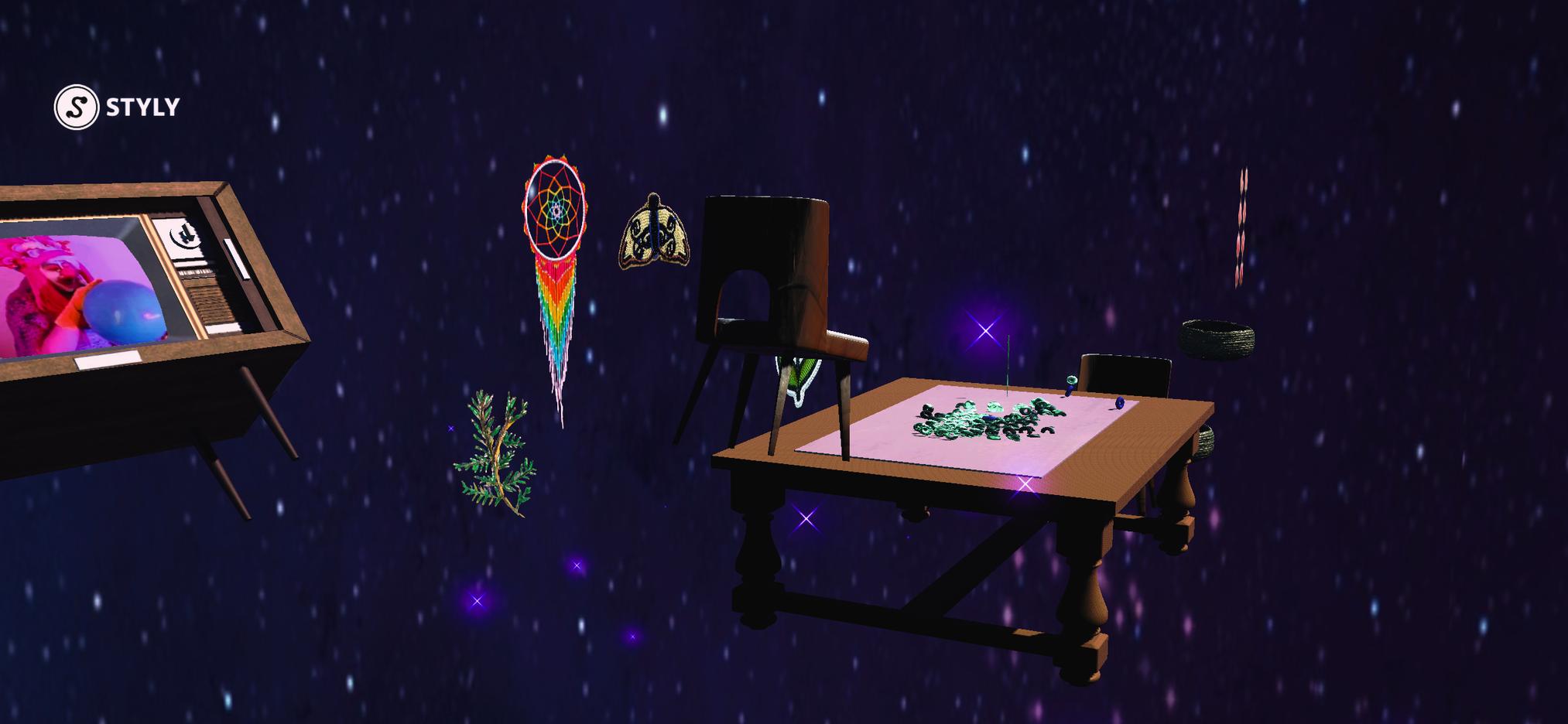

This exhibit is located in cyberspace and is available using STYLY, using virtual reality.

You can experience this interactive artwork in three different ways:

Mobile

You can interact with the artwork using your smartphone. It is compatible with Android and iOS.

HMD (Headmounted Display) VR

Headset

Compatible with all major virtual reality headsets such as Oculus Rift

Desktop Computer

You can connect to styly.cc online using your computer’s browser.

STYLY Mobile is a smartphone application for experiencing AR and VR scenes delivered to STYLY.

You can experience an AR or VR scene by loading a marker called “STYLY marker” on STYLY Mobile. You can also experience the AR scene delivered by STYLY by selecting it on STYLY Mobile

Digital Constellations: Making Our Own Seat at the Table

Scan this code with your smartphone’s camera to activate the VR scene.

Featured Artists

Amanda Amour-Lynx, Samay Arcentales Cajas, Mel Compton, Nico La Liberté-Cozzens, Nishina Loft, Sheri Osden Nault, Thomas Robertson, Rihkee Strapp, Sydney Wreaks, Emily Wright

Immersive Audio by Free Lynxii + AKASOLEIL

The sky world wishes for you to perceive orientation more expansively The ancestors have been mapping the sky for thousands of years. The stars are responsible for being the time keepers for all life on Earth.

Sydney Wreaks

Butterfly

Mel Compton

Tobacco Embroidery

Amanda Amour-Lynx

Digital Brick Stitch Spirit Beads

Samay Arcentales Cajas

3D Chakana

Nico La Liberté-Cozzens

Cedar Wild Rice Blueberry

STYLY: OVERVIEW

Thomas Robertson Animation + Coding

Emily Wright Immersive Dreams

Sheri Osden Nault Orbital Baskets

Rihkee Strapp

Clown TV

Nishina Loft Land Back

The spirit beings who reside in the sky lodge can be communicated with by following a simple set of instructions.

You may approach towards the pulse of energy at the center of the table This is going snake-wise You may leave the table with cautious motion, counter-snakewise to see what inhabits the fringes of the galaxy.

During the Summer of 2023, the Digital Constellations Mentorship program was launched by Amanda Amour-Lynx with the support of Indigenous Youth Roots. Its primary goal was to empower young people who have limited access to institutional privilege, education and networking connections and create pathways for their professional advancement.

The group was invited to attend five virtual workshop sessions delivered by Two Spirit cultural creators, artists, storytellers, curators and small business owners to learn all about how to engage with cultural and art institutions, including how to talk about, protect and conserve the cultural significance of their material practices related to cultural objects, craft and regalia. Workshops were recorded, captioned and uploaded onto a digital learning platform that contained resources specifically for independent Indigenous cultural creatives. They learned how to document their work using their phone, DIY materials and were gifted a digital photography supply kit.

I wanted to create something that I wished I had when I was trying to find my way with cultural art making while attending college and university and kept coming up against repeated colonial barriers including systemic discrimination, academic and bureaucratic language and institutional gatekeeping (Lynx).

The mentorship environment welcomed an engagement level guided by their own pace and on their own terms, choosing their level of involvement as the young people identify with two spirit realities. It is integral to uphold this sense of discretion to members of the program so they can decide for themselves the degree of public access to their creative process, and several expressed finding a lot of value in their anonymity and choice whether to exhibit their works for Digital Constellations: Making Our Own Seat at the Table

I wanted to create something that I wished I had when I was trying to find my way and coming up against repeated colonial barriers including systemic discrimination, academic and bureaucratic language, institutional gatekeeping.

Imagining a Two Spirit toponomy: Our names are the soul memory of who we truly are

By Amanda Amour-LynxWeji sqalia’timk is a concept deeply ingrained within the Mi’kmaq language,

a language that grew from within the ancient landscape of Mi’kma’ki. Weji sqalia’timk expresses the Mi’kmaw understanding of the origin of its people as rooted in the landscape of Eastern North America … our culture, language, and identity sprouted from these lands, much like a plant sprouts from the earth. The Mi’kmaq emerged from this landscape and nowhere else; their cultural memory resides here (17 Sable, Francis).

Toponymy, or the study of place names considers the ecological, cultural and linguistic origins of how places come to be named.

2SHieroglyph,Amour-Lynx,2022

Last year, my friend Jess Murwin gifted me the “Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names” map published by the Canadian-American Center, University of Maine. I felt the warmth radiate through me as my fingers traced over the map learning the original names of locations all across Turtle Island, entirely consisting of the Indigenous languages spoken here. Each name felt like finally learning the truth, being introduced to places I’ve visited and lived for years, as if for the first time.

Indigenous placenames carry significant geographical and cosmological cues about the land, embedded in the very structure of Indigenous languages themselves.

When welearn a place’s name,it comes with a set ofinstructions and responsibilityofhow to carefor theland

Naming is descriptive not prescriptive, verbbased in structure and holding relational connection to its environment. For example, Sipekne’katik, presently known as its Anglicized Shubenacadie, contains two phonemes: sipekn and acadie, or e’kati, meaning the place of the ground nut or ground potato, an underwater tuber that was known as primary sustenance in the area. E’kati as a suffix means ‘the place of’. Placenames are an ancestral oral archive of significant histories and survivals. Reflecting a time before global trade and commerce, these noticings carry deep cultural significance.

Gerald Gloade, L’nu geologist, artist and storyteller from Millbrook First Nation describes a place’s relationship to the specific habitat and language of L’nuekati’k. He shares with Acadia University his first assignment in post secondary to locate every one of Kluskap’s legends geographically. He confirms that all identifiable landmarks, particularly of the waters, are embedded within these L’nu legends.

Gloade describes how descriptive suffixes referring to place in the L’nu language, had been adopted and translated by early French and English settlements who arrived on the territory. Ethnographers who recorded L’nu’k customs and language such as Silas T. Rand, Charles Godfrey Leland, and Wilson D. Wallis had their misunderstandings of pronunciation and orthography, which resulted in centuries of loss of land-based knowledges contained in the original etymologies and stories.

The Mi'kmaw Place Names Digital Atlas has contributed invaluable efforts towards recovering these etymologies. Initiated in 2008, this website resource holds over 800 place names, gathered in collaboration with elders, cultural leaders, scholars and researchers. An interactive map hosts clickable video clips and sound bytes, documenting these linguistic timelines and recovering original L’nuismk descriptions through diligent efforts to maintain intergenerational relationships with elders who remember the meanings of placenames, prior to such mutations in language.

Deities and helpers watch over the land. They are our reminders to seek balance and to remember kindness. Nature will do what it will, constraining it may only temporarily delay the existence of naturally occurring cycles. Landbased teachings express to you how to better coexist with the cycles and patterns and learn how to identify them.

When reconnecting with Jess recently to discuss the mentorship project and collaborative exhibition, they shared with me a poetic metaphor of their relationship to placenames through a trans, two spirit lens. What they shared with me stirred me on a profoundly emotional level:

“When we choose our name and undergo the legal process of renaming ourselves, this feels intrinsically tied to the land and our relationship to who we are and how we are meant to exist on it. Similarly, learning one’s spirit name in ceremony or reclaiming an Indigenous surname after colonial policies have taken language access away from our peoples, feels like coming home to yourself.”

In the whimsical world, there are no rules bounds. Where I grew settler in Anishinaabek of many protocols around images and no Anishinaabemowin word for art, but a language made of it. Without the academic background, I am a peculiar figure to guide anyone, but I have been summoned to take us through an extraordinary journey.

I am your host, Miskwa the MAD clown prophet, your mischievous uncle and guide into the world of Digital Constellations: Making Our Own Seat at the Table, a virtual reality exhibition created by emerging and mid-career Indigenous and Two-Spirit artists, Amanda Amour Lynx, Mel Compton, Sydney Wreaks, Thomas Robertson, Sheri Osden Nault, Nico Laliberte-Cozzens, Nishina Loft, Emily Wright, Samay Arcentales Cajas and myself.

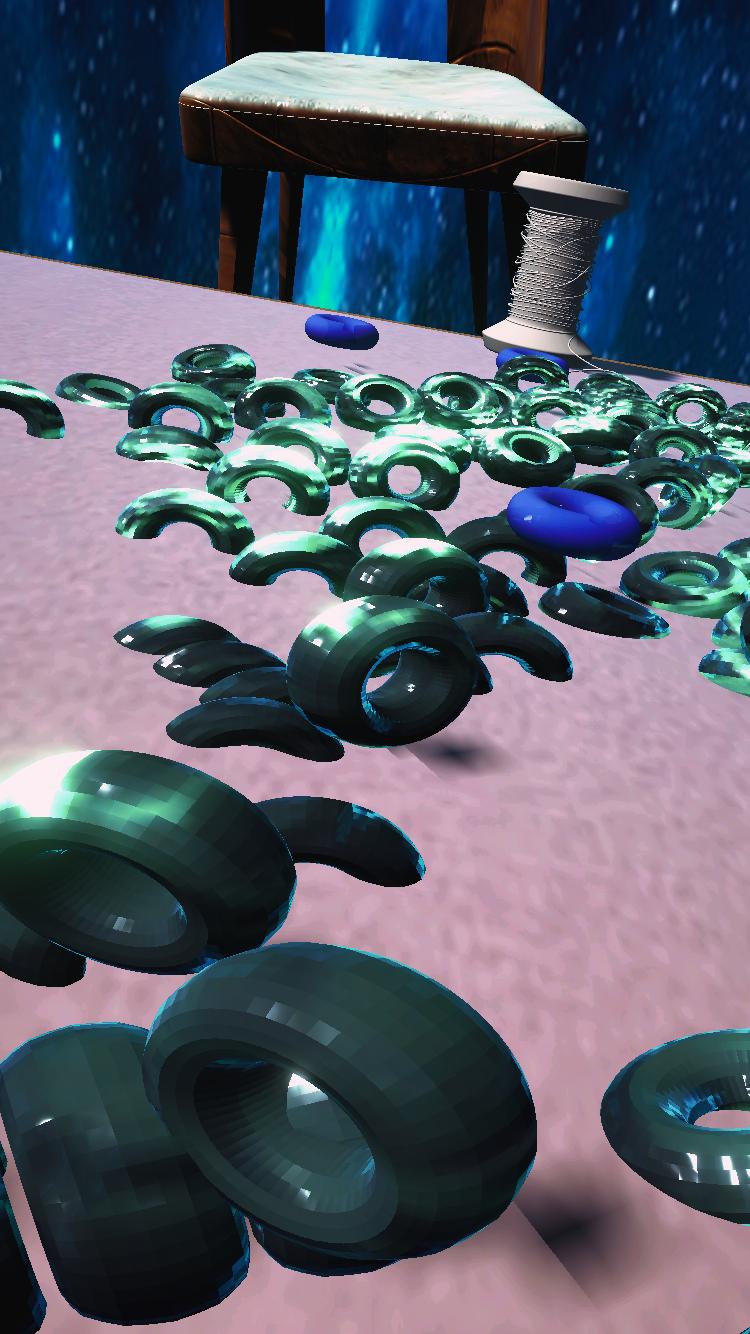

Brace yourselves for atmospheric entry into a digital world where queer Indigenous methodology finds its home in the digital ether. The first thing that grabs our attention is two chairs, each placed neatly at a table. This setup reminds me of Keeoukaywin, the Cree Michif word for visiting, conversation and connection, a place where stories are shared, traditional crafts are passed down, and kinship is strengthened. Métis researcher and educator Janice Cindy Gaudet links Keeoukaywin to what Sherry Farrell Racette, a Métis scholar and artist, refers to as “kitchen table theory,” a reclamation of women’s spaces and ways of doing things. In Gaudet’s words, “Keeoukaywin is a way of celebrating life, creating alternative knowledge, learning, and sharing, a living expression of wahkotowin (the state of being related) that resists colonial dominance” (Gaudet 55).

The kitchen table originated in the 14th century. Europeans had experienced a dramatic loss of life during the Black Death, and colonization was opening new trade networks. Originally exclusive to the rich elite, this dining setup would become common in the 17th century, as those new trade routes brought new wealth, foods and materials like porcelain. The import of Chinese and Japanese porcelain would inspire the style of Spode China that would eventually be gifted to Norval Morisseau from the Queen near the height of his art career (Nohkum).

Métis elder Maria Campbell says “Theory comes from the way you lived. It is inside of you. Go home, visit your relatives, visit the land” (Gaudet 55). When I think about the importance of this relationality, I think about the import of the kitchen table as a drastic alteration to traditional relating. When comparing to the traditional dining practices of the Mi’kmaq, daily life drastically changes with the import of the table and European dining practices:

Since moose are so large, it was easier to eat it where it was killed rather than to carry it back to the camp. They would make a cooking vessel on the spot, using a section of tree trunk that was cut and the interior hollowed out … Dipping was done with a ladle that was made very quickly using a single fold in a piece of birchbark and inserted in a split stick handle (Stoddard).

The table is also the place where bureaucratic practices continue to colonize Indigenous lands and peoples in the boardroom through policy: “State practices, policy and rhetoric have often provided the formal framework within which hate and hate groups can emerge” (Perry and Scrivens 9). In this context, Digital Constellations: Making Our Own Seat at the Table is a testament to the innovation and expression of Two-Spirit resilience against ongoing colonialism and erasure.

Within colonization, artists play a significant role in the erasure of traditional nation-specific Two-Spirit identities and ceremonies. Early Canadian art was predominantly financially supported by church commissions and the early biases of God-fearing artists themselves sought to delete the existence of these people and ceremonies from collective memory. The American artist George Catlin who painted “Dance to the Berdache,” said that the Two-Spirit tradition must “be extinguished before it can be more fully recorded.” Art, like the residential schools, were used as a tool for indoctrination of Indigenous peoples into the dominant colonial culture, as well as reaffirming the beliefs of the early settlers.

The waning complex Western open display only one

However, this cultural bias strongly skewed the gathering of information. Descriptions of [Two Spirits] sometimes contain much more denunciation than data … Indians who absorbed the biases of the dominant culture became reticent about [Two Spirits] or denied their former existence (Kochems and Callender 443).

Jas M. Morgan brings us to the present moment and illuminated the public along other key figures to the ongoing acts of colonialism in Canadian art, in various essays including “Making Space in Indigenous Art for Bull Dykes and Gender Weirdos” (2017).

In 1990, during the Intertribal Native American, First Nations, Gay and Lesbian American Conference in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Elder Myra Laramee proposed the term Niizh Manidoowag

which is Anishinaabemowin for “Two Spirits.” In 1991, Ojibwe artist Rebecca Belmore used technology to renew kinship with the land in Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to their Mother. That same year, the internet's accessibility to the mainstream through the World Wide Web marked a pivotal moment in the history of the internet. One of the early adopters of this technology is Skawennati, who presented the pioneering work CyberPowWow in 1997, an early exploration in internet art publication. As Mikhel Proulx writes, “Materializing at this confluence of Indigenous cultural activism and early web cultures [CyberPowWow] offers a fascinating alternative to mainstream histories of network-based art” (Proulx 203). Modeling Indigenous sovereignty in cyberspace, CyberPowWow foreshadowed the impact that Facebook would have on the Idle No More movement.

With Skawennati, digital media artist Jason Lewis began Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTeC), a network of academics, artists, and technologists in the early 2000s. AbTeC supports researchers and authors to write about the plethora of media art that Indigenous artists were already creating ensuring visibility of these creators. Carla Taunton points out how “These kinds of collectives and associations provide opportunities and support for the growth and development of Indigenous youth so they can imagine what their future might hold” (Taunton 9).

The tale of the internet's birth, born from the crucible of the Cold War, emerges like a mythical creation story. J.C.R. Licklider’s "Galactic Network" concept, a manifestation of the pressing need for a secure communications network in those perilous times, set the stage for the digital revolution that was yet to come. It was a time when the world was on the brink, and the launch of Sputnik the world’s first manmade satellite sent shivers down the spines of Americans. The internet was envisioned as a lifeline, an intricate web that would weave its way through global communication. There were many pivotal technological innovation points in the history of the internet, one such project being ALOHANET. Tyler David Morgenstern looks to “Chicaksaw scholar Jodi Byrd to suggest that the ALOHAnet in this regard functioned as an imperial “transit;” a site at which entrenched colonial imaginaries of ‘Indianness’

Thefloatingbaskets evoke a sense ofthe sacred, astheir rotatingorbit mirrorsthe cyclical nature of stars andtheharvesting seasons of pinetrees

“Digital Constellations: Making Our Own Seat at the Table” is a mesmerizing scene float-ing gracefully in the vast expanse of an astral cyberspace. Sheri Osden Nault’s 3D scanned pine needle baskets orbit around the digital space reminding me of Sputnik and satellites. These baskets are a symbol of the interwoven threads of Indigenous knowledge passed down through generations. The floating baskets evoke a sense of the sacred, as their rotating orbit mirrors the cyclical nature of stars and the harvesting seasons of pine trees which would support their own material production. Like the

connections between our reality and the star world, Indigenous scholars and artists Jason Edward Lewis, Noelani Arista, Archer Pechawis, and Suzanne Kite remind us that:

AI is formed from not only code, but from materials of the Earth. To remove the concept of AI from its materiality is to sever this connection. Forming a relationship to AI, we form a relationship to the mines and the stones. Relationships with AI are therefore relations with exploited resources” (Arista et al. 49).

aresewntogetherbynon-humans.

In earlier digital works, artist Amanda AmourLynx refers to the cosmological belief that the starry sky is where the Mi’kmaq originated and where they will return when they join their ancestors. In this sense, the virtually produced celestial space is where exploited resources, human and non-human dream of ancestral reconnection. Nico La Liberte-Cozzens’ contribution to the artwork reflects a desire to reconnect with plant kin. His cedar drawing floats delicately by the table providing the protection needed to gossip while we bead together.

Beaded tobacco and a butterfly by Sydney Wreaks and Mel Compton respectively, float above the table like an intertribal dance. The use of Kanien’kehá ka motif is here and I am reminded of the multitude of relations that can be expressed depending on the context through this dynamic motif.

Artist and scholar Steven Loft “identifies these indigenous ecologies and cosmologies as cyberspaces … In this way, new media technologies are not so new in that they just enhance the shared connections between past and present, the earth and the universe, and the material and virtual realities that have been and still are intrinsic to Native cultures” (Loft via Taunton 123).

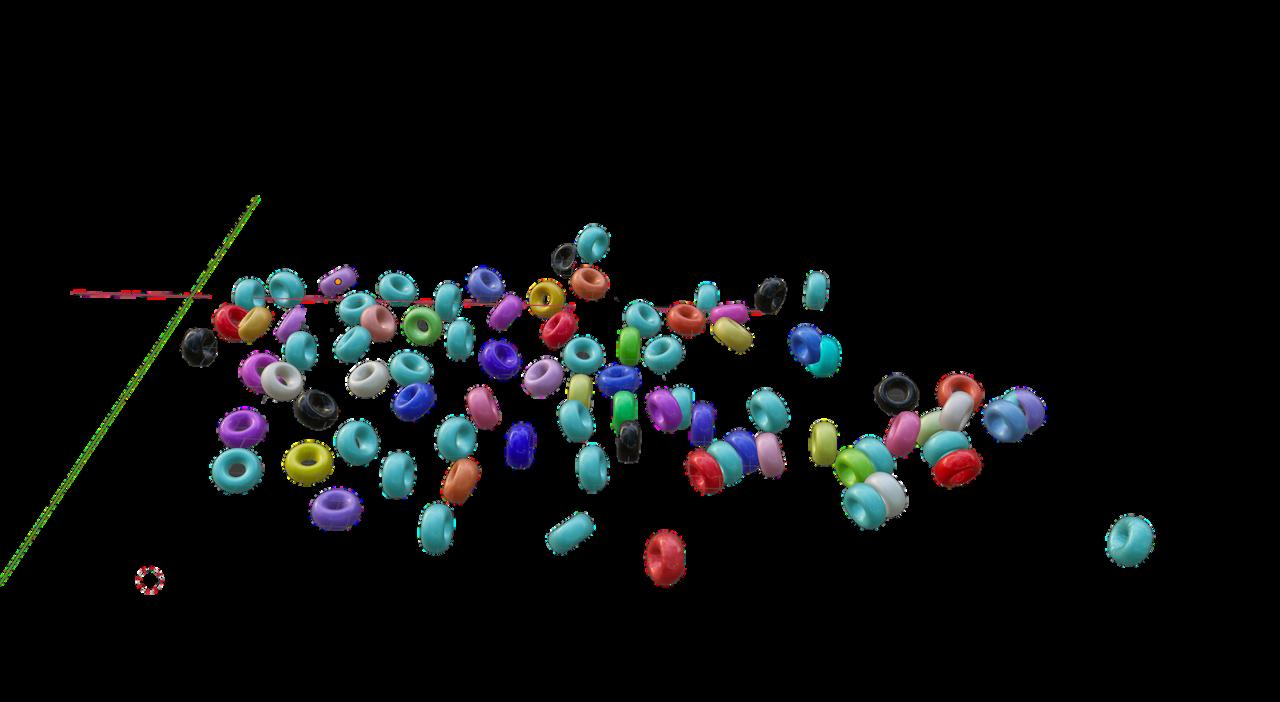

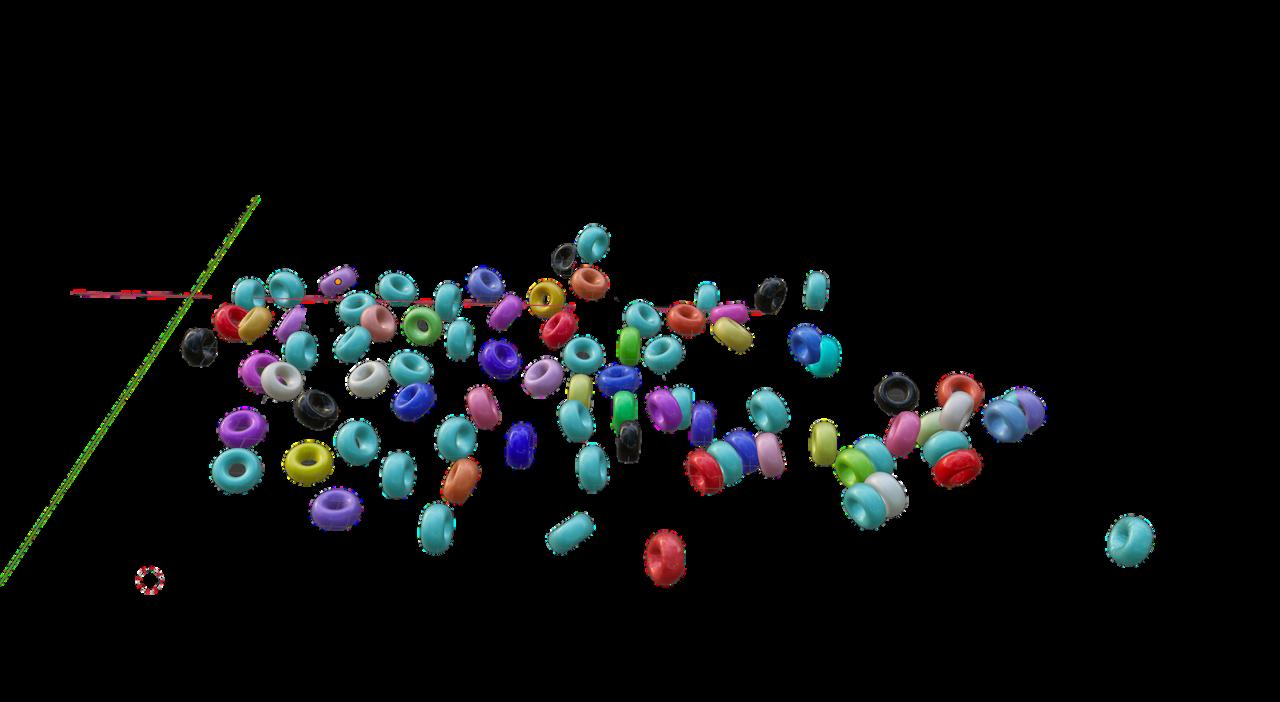

The animated beads take on a personal significance as their luminescence makes me imagine a spirit bead gathering in cyberspace, where all the individual spirit beads in our crafts are sewn together by non-humans. They become

Beaded tobacco and a butterfly by Sydney Wreaks and Mel Compton respectively, float above the table like an intertribal dance.

a digital representation of the interconnectedness of all space and time in the dream realm.

The year is 2017, and I am at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, it is the 3rd Annual Symposium on the Future Imaginary and the crowd whoops and hollers as the Métis are mentioned in the land acknowledgement. Many speakers I recognize from AbTeC’s network, as well as artists working in traditional technologies like Ojibwe artist K.C. Adams who creates traditional clay vessels and the stories woven into that process. Like the encoding of stories into cooking vessels, Indigenous technologists explained the need for our own coding languages, as much of our modern technology reinforces the colonial perspectives that dominate the field.

I find myself immersed in the vibrant chaos of the symposium's second day. The air is electrified with anticipation as the lectures are over and the crowd gathers to play video games and experience virtual reality pieces. I join the queue to step into Kent Monkman's VR adaptation of Honour Dance, an experience in

Like the encoding of stories into cooking vessels,Indigenous technologists explained the need for our own codinglanguages

the spirit of the same traditional Cree ceremony that once left George Catlin preaching to extinguish its memory.

The first time I entered the “Making Our Own Seat at the Table” on my phone, I immediately inadvertently threw a digital chair into the infinite space. Later, one of the digital beaded earrings would collapse and beads would spill into the stars and float away like a jellyfish. Rotating around the table, you will find a rogue bead flirtatiously humping the table. As a clown, I can't help but be reminded of the mischievous beings that often challenge the status quo, disrupt expectations, and encourage us to see the world from a different perspective. In this exhibition, the code becomes modern-day tricksters. I make my own seat at the table, projecting myself on a television, dressed as the pope of the swamp and blowing up a balloon. Both observed and an observer.

As we leave this virtual gallery, let us remember to challenge the colonial narratives that have shaped our perceptions and seek to understand Indigenous cultures from their own nation specific perspective. What is currently known as Canada has seen a persistent increase in sexual orientation and sex and gender based hate crimes according to stats Canada. Let us support and protect the Two-Spirit artists and youth creating sovereign digital spaces into the future.

Amanda Amour Lynx (they/them/nekm) is a Two Spirit, neurodivergent, urban L’nu Scottish interdisciplinary artist and facilitator living in Guelph, Ontario. Lynx was born and grew up in Tiohtià:ke (Montreal) and is a member of Wagmatcook FN. Their art making is a hybridity contemporary painting with new media and digital arts, guided by the Mi’kmaq principles netukulimk and etuaptmumk.

Lynx’s art discusses land, relationality, ecology, navigating systems and societal structures, gender identity, L’nui’smk language resurgence, quantum and spiritual multiplicities.

Their facilitation work focuses on designing community spaces committed to creating healthy Indigenous futurities, guided by lateral love, access and world-building.

@amour.lynx @free_lynxii www.amour-lynx.art

5

Sheri Osden Nault

Sheri is part of the Indigenous Tattoo Revival movement in so-called Canada, and run the annual community project, Gifts for Two-Spirit Youth.

Sheri currently lives and creates near the Deshkan Ziibing, on the lands of the Anishinaabek, Haudenosaunee, Lunaapéwak, and Chonnonton Nations, also known as ‘London, Ontario.’ They are colonially displaced Michif and nêhiyaw of the Charette, Bélanger, and Nault families with connections to the Red River, Duck Lake and Batoche, North Battleford, and Rocky Mountain areas.

@so_nault

www.sherinault.com

3D scanned basket by Sheri Osden Nault

Cedar illustration by Nico La Liberté-Cozzens 19

Nishina Shapwaykeesic-Loft is Kanien’kehá:ka from Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. She is a 2S queer, multi-disciplinary artist in a wide spectrum of mediums. She is a beader, mural artist, filmmaker and costume designer. She continues to grow within her field and explore new opportunities. @nshtsh

Rihkee Strapp entered the world from a sea of blood, fully grown wearing a gold set of armour. They are an Ayakwew Métis multi-disciplinary artist raised in Northern Ontario by nohkum’s dialup internet and its dark vistas. Rihkee is an alumni of the Studio [Y] systems leadership fellowship at the MaRS Discovery District. Their highly collaborative work re-appropriates popculture, myth and nostalgia, playing with concepts of time and technology often using humour and character to animate their ideas. @miskwathemadclown www.rihkeestrapp.ca

Jess Murwin is a nonbinary Indigenous (Mi'kmaq, Scottish and Welsh) filmmaker, curator and educator based in Montreal, Quebec. Their work is largely community-based, and draws on genre and storytelling traditions to imagine social change.

As a programmer, they have worked for the Atlantic International Film Festival, the Toronto International Film Festival, and Rencontres Internationales du Documentaire à Montréal, among others. Their focus in presenting films and media artworks has always been to champion stories by 2SLGBTQ+, and Indigenous artists. They see this work as a critical way of reclaiming narrative spaces.

@jessmurwin

Hi, I'm Thomas Robertson, I'm a game developer and system administrator in my spare time. I currently work for a print shop, and I'm going to school to get a computer systems technician degree. I am Mi’kmaq from Wagmatcook FN and presently live in Montreal, Quebec.

Samay Arcentales Cajas Thomas RobertsonThe concept for Digital Constellations: Making Our Own Seat at the Table was to create a hypersurreal landscape where Indigenous future imaginaries, dreams and stories can exist. I romanticize celestial spaces that subvert the colonial gaze. The scene posits itself as a private sanctuary, outside of colonial and heteropatriarchal structures.

The augmented reality-space acts as an idealistic yet rebellious intervention, an alternative to assimilation, a refusal of normative and exclusionary spaces, unsettling the limitations imposed upon non-binary, trans and two spirit people in particular.

Cultural connection is potent when we share meals, stories, and craft at a table together. This is where our knowledge transfer happens, this is where we bead and bitch, this is where our truthtelling is sovereign and allowed to exist.

Having a seat at the table is a metaphor around belongingness and inclusion. Queer, Indigenous. racialized and disabled voices have historically been excluded from spaces where decisions made concerning their rights and determination. This project was envisioned way to bring in their perspectives to the realm new media practices.

Via finite state machine, the scene can be explored interactively: chairs, crafting supplies and fantastical oversized beads can be moved, dragged, lifted and thrown. My brother Thomas and I came together to bring those elements to life.

Sacred plants sit by the table as a wise council overseeing the gathering. The material context of beadwork and handmade baskets transform into cosmic beings who and the playful traditional ways of

www.amour-lynx.art

@amour.lynx

@free_lynxii

built in scripts, I made a few in the background, and added the objects in the scene, to pick up and move pretty much anything they wanted.

ended up being a bit of a to be an interesting mess, so I What happened was, I added each of the beads, to make them as you picked up the object in the scene. It worked.

having really wonky physics, too many spring joints bouncing getting tangled, which caused to turn into what looked like a monster, and when you picked wriggle away off screen. I felt like bug added a bit of personality up adding to the scene. The d up being normal, however. demonstrate that it was normally possible

Living in the city makes me miss nature a lot, especially plants I never see out here on the west coast. I make quick doodles and sketches of plants and animals that carry meaning to me and my culture to help me feel better. These are some of those sketches from the last few days; I used coloured pencils and brush-tip pens to make the colours pop as they do in real life.

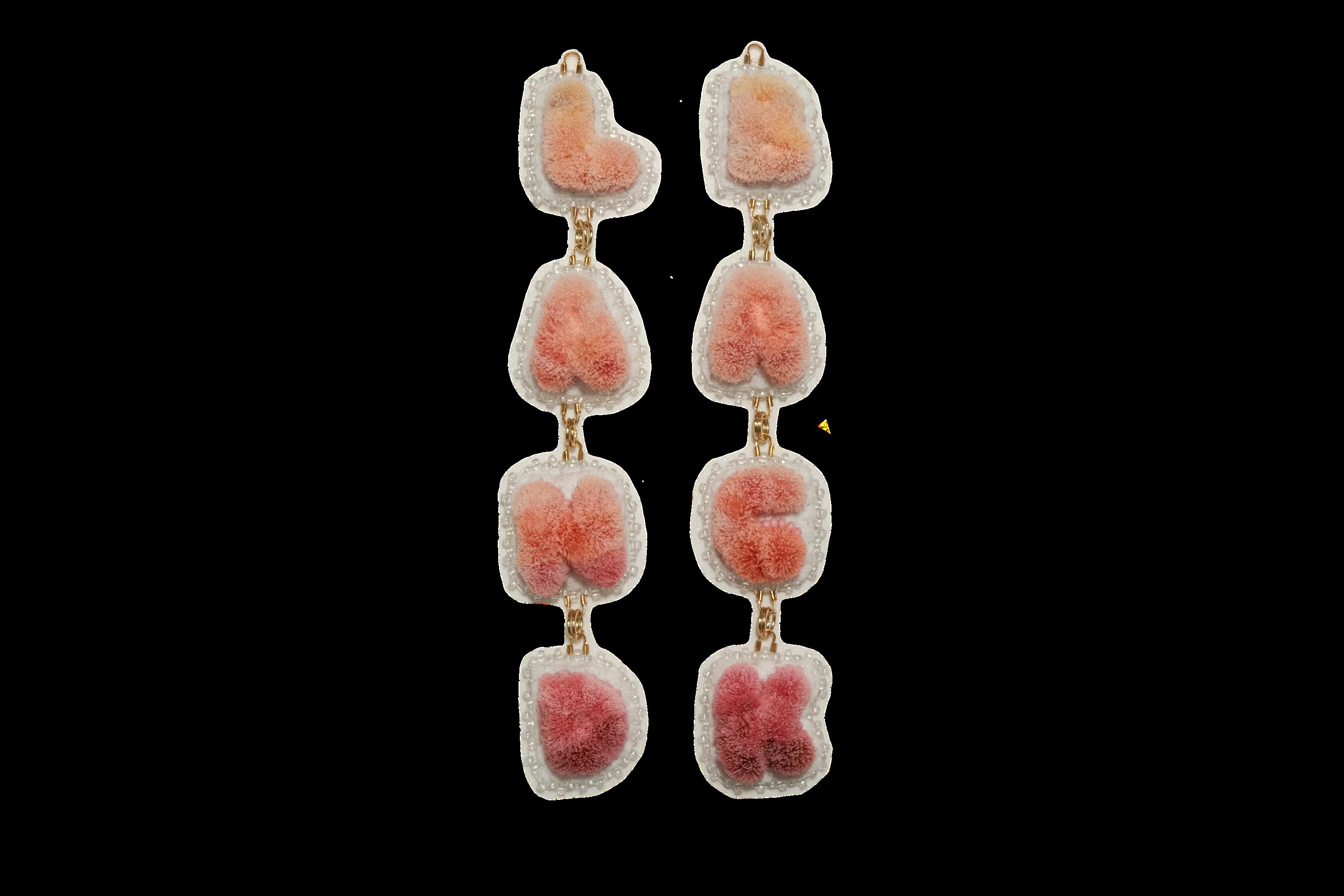

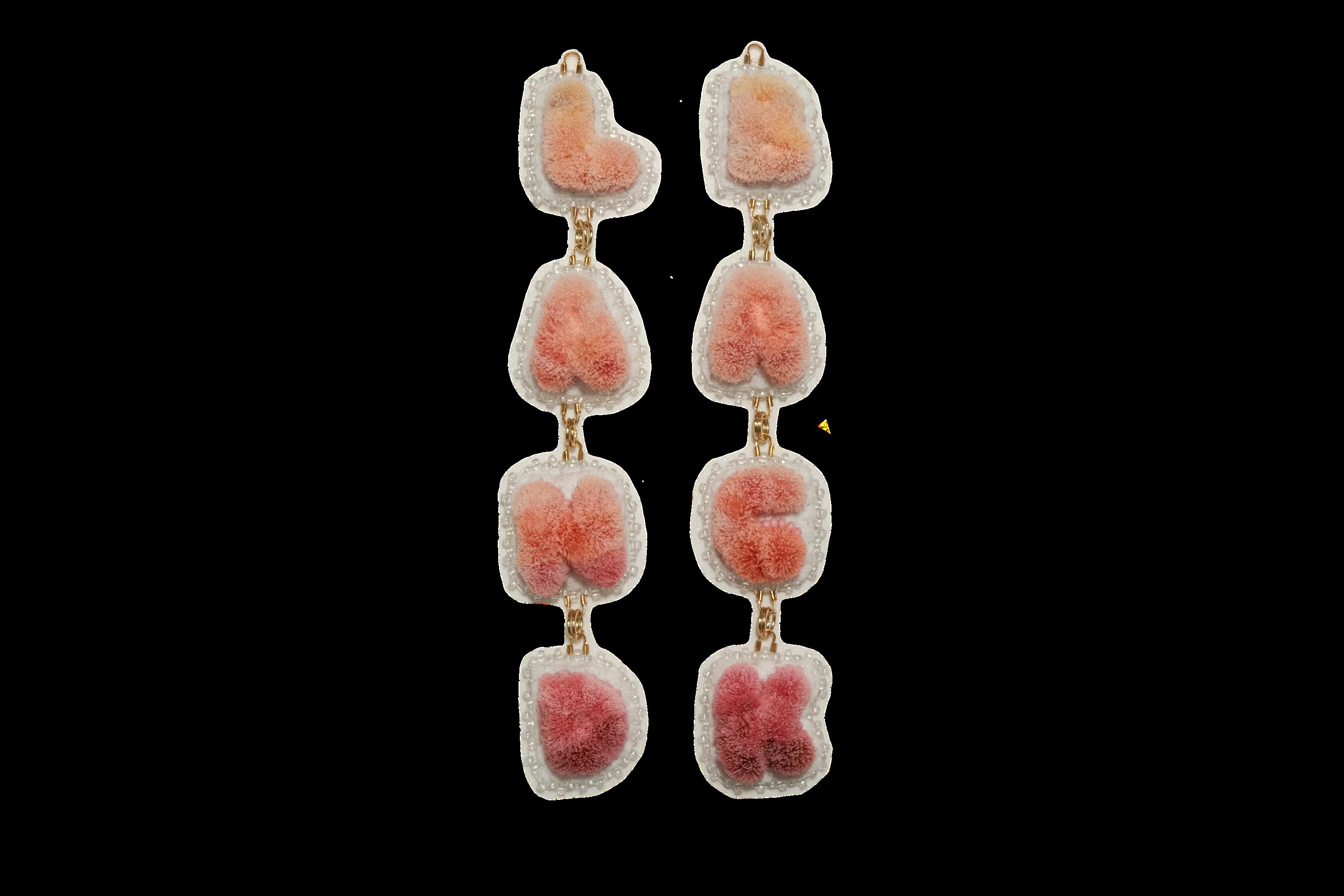

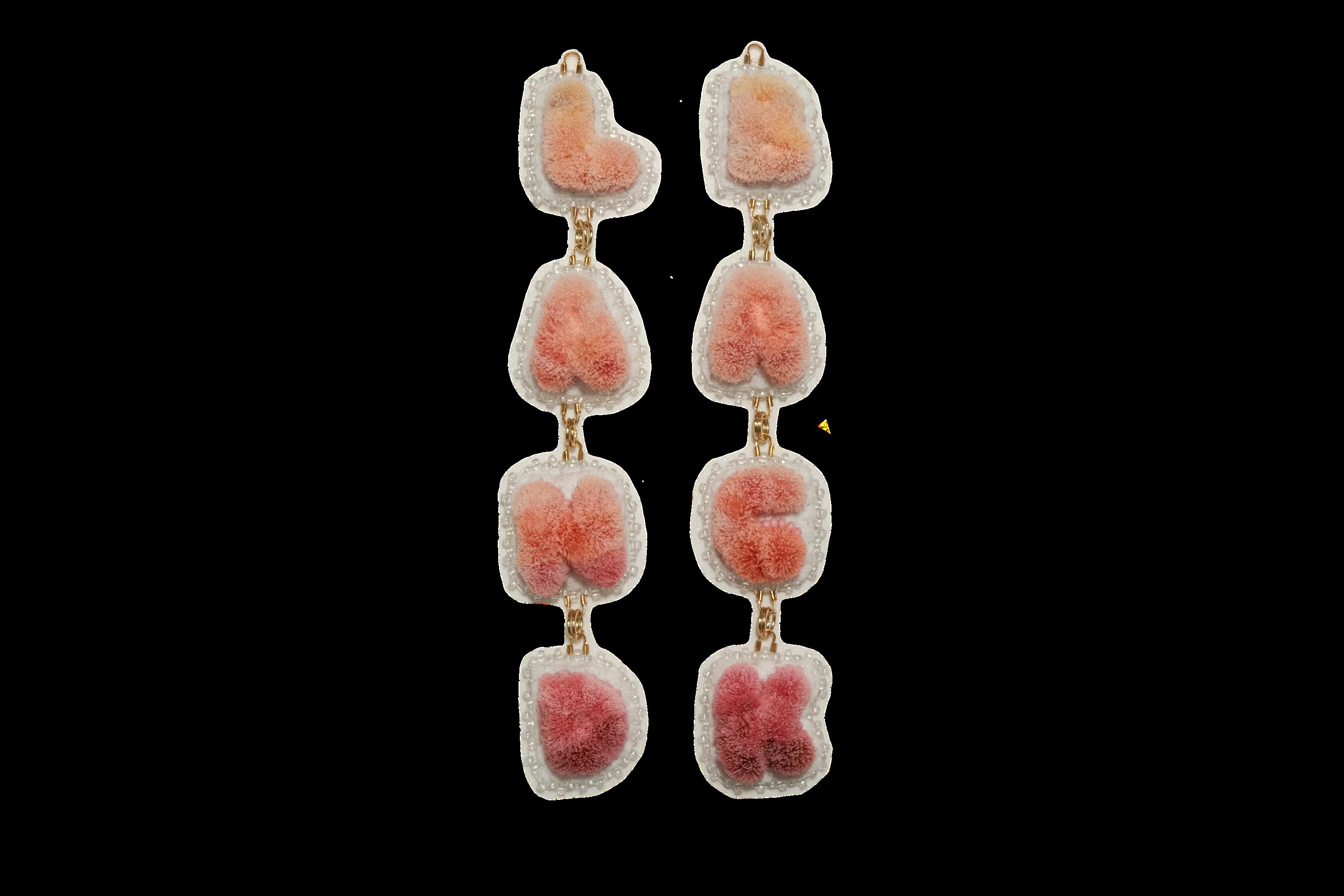

These earrings are a part of a full collection that say Land Back. They are an ombre pink drop earring made up of individual letters. They are made through a traditional practice called tufting with caribou hair that have been dyed. Land Back means different things to each Indigenous person. I thought about the protection for Mother Earth as I created these.

Emily Wright is an Indigenous artist from Wasauksing First Nation with Scottish settler roots. Utilizing contemporary styles with traditional art forms, her work can be described as "big boujee glam”

Follow Emily’s designs and projects at markets and the pow wow trail:

@nishbishdesigns

Three months before the start of the global pandemic, I was diagnosed with an auto-immune condition. My body was yelling at me and I didn’t know how to acknowledge the stress I was putting it under. Like so many of us, I turned to creating as a form of escape and healing. In a strange way, the pandemic forced me to slow down. My entire existence revolves around being an urban person with limited traditional access to Indigenous foods and medicines. The access I did have was hindered by my auto-immune diagnosis that rode alongside the pandemic. This led me to what I called creative pandemic access projects where my creative practice strongly focused on things like medicines and traditional foods. I gravitated towards the things I felt I needed: needed for nourishment, needed more access to, needed to hold and needed for healing.

It started with the four main sacred medicines that many nations use: Sage, Cedar, Sweetgrass and Tobacco, reflected as a Tobacco plant in the STYLY scene. I was making Three Sisters soup a lot through the pandemic and wanted a way to acknowledge the teachings and medicines they give.

The teachings of the three sisters can be summarized as love, community and connection I wanted to take it a step further in order to represent the L’nu teaching of etuaptmumk. Two-eyed seeing presents itself in many different areas of our lives. It’s not just a part of our identity but woven into the way we cook, the way we create, the way we hold space and even in the way we speak. The two different versions of each sister is a reflection of walking between two worlds with the under-tone of how we access them, who gets to access them and what variations are accessed and where.

Corn, beans and squash aren’t just foods, they are medicine and should be readily accessible.

The chakana is an important Andean shape and symbol that encompasses a lot of our traditional cosmology.

Pacha Arts is an Indigenous (Kichwa) family owned store based in Toronto, connecting Indigenous arts and artists from North and South America.

www.pachaarts.com

@samay.c

@pacha_arts

Manifesting medicine through beading and gift-giving.

Beading as Community Counter-Mapping is a participatory, community-based art project that prioritizes Indigenous beadwork teachings when considering our relationships to the land in our communities. Participants are asked to create beaded ‘land-marks’—items that emphasize or are connected to the land in their communities. When considering your land-mark, think about how the land takes care of us. How is that information shared across generations? How can accessing that information become a way to disrupt colonial understandings of the land?

Difficult Histories Database is an openaccess, free, and digitally accessible archive of sites of difficult knowledge and history in and around the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM), in Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and unceded lands of the Mi’kmaq. This territory is covered by the Treaties of Peace and Friendship which Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725.

difficulthistoriesdatabase.com

@sydneywreaksart

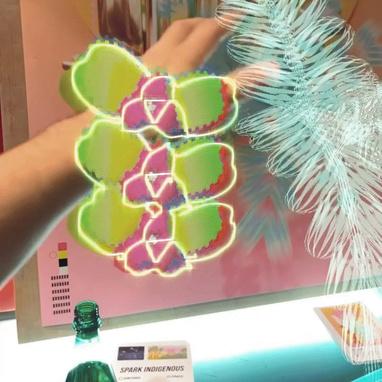

Slow Studies Creative partnered with Meta to launch Spark Indigenous: Augmented Reality Creator Accelerator. This five-week program trains 10 Indigenous creators using Meta Spark Studio to integrate interactive AR experiences into their cultural storytelling.

Meta Spark Studio is a free-to-use AR design platform that provides people with the tools and resources to build their own augmented reality experiences. The user-friendly interface allows anyone to start building whether they have a technical background or not. Start from templates or build custom AR experiences with code as you bring your creative ideas to live.

The Digital Constellations Mentorship program at Indigenous Youth Roots was largely inspired by the curriculum of Joshua Conrad’s augmented reality initiative, Spark Indigenous as an adjunct learning opportunity for IYR’s mentors to develop skills and increase access to new technology.

Our program goal was to increase access for young Indigenous artists and makers in a multifaceted way, using immersive new media as a way to subvert dominant narratives and bring Indigenous culture into digital spaces.

Through the Digital Constellations Mentorship group attended beginner tutorial on how to use the STYLY platform to amplify their storytelling and animate their artworks.

Josh Conrad is a multi-disciplinary New Media artist, Art Director and the Founder of Slow Studies Creative. He is currently living and working on the unceded territory of xwməθkwəy əm, Skwxwú7mesh, and Səlílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh Nations also known as so-called Vancouver. He has Stó:lō / Portuguese roots with strong Nlaka'pamux ties, and belongs to Chawathil First Nation, on S'ólh Téméxw.

His visual mediums include 3D illustration, Motion Arts, Projection Mapping, Installation and Augmented Reality.

He enjoys using bright colours, abstract fluid shapes, places and textures from his memories, and the lush flora from the environment around him to encourage a sense of tactile exploration. With programs typically used to create renders of the real world as realistic as possible, he instead imagines out-of-this-world pieces that often float, bounce, and slide between the boundary of dreams and reality. These soothing forms use familiar textures, feelings, materials and sounds to evoke the senses and promote exploration into the worlds he creates.

@slowstudies_creative www.slowstudies.com

The culture and spirituality of my Coast Salish people has always been a part of my life, but it wasn't until I decided to become an artist that I found the perfect way to express that part of myself.

Originally from Seabird Island, B.C., being a selftaught artist with roots in the Nlaka'pamux and Sto:lo Nation I've built a burgeoning design career, creating logos and other artwork inspired by the traditions of his people for Indigenous and nonIndigenous businesses and for several apparel companies.

Art feels vital to me And being able to share that passion I have is important to me. This tradition of work, and this beauty, is so necessary for our culture and healing.

Find Ovila on Instagram @ovila79 or online at

www.salishsondesign.com

Mel Beaulieu (they/them) is a mixed media artist, with a focus on contemporary beadwork. Through their work they express a sense of fun and nostalgia, creating things that their younger self would love.

Mel is a member of Metepenagiag First Nation and lives and creates in Fredericton, NB.

They can be found on Instagram at @the.beads.knees or online at www.thebeadsknees.ca

Nalakwsis (they/them) is an Eeyou illustrator, contemporary bead artist, photographer, emerging art director and concept artist based in Whapmagoostui, QC. Learning from Eeyou legends, culture and spirituality, they weave these teachings into their work.

Emma Hassencahl-Perley is Wolastoqwiw from Neqotkuk (where the two rivers flow beneath each other), also known as Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Art from Mount Allison University (‘17) and a Masters of Art in Art History (‘22) from Concordia University. Emma is a Visual Artist, Curator, Educator, Author, and Arts Criticism Essayist.

Find Emma on Instagram @emma_hassencahlperley or online at www.emmahassencahlperley.ca

Charlene Johnny is a Coast Salish artist from the Quw’utsun Tribes of Duncan, B.C. residing on the unceded territory of her relatives the xwməθkwəy əm, Skwxwú7mesh, and Səl ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh Nations. She began her career in 2012 when she won two artist grants from the YVR Art Foundation working with business, graphic design, photography, glass, and textiles. She has apprenticed under wellknown artists and has formal art training from Native Education College. She graduated from the silver and copper carving program in 2018. She became a full time artist in 2020, with her main practice in graphic design and mural art. With her interdisciplinary approach to art and language, she will continue to work in various mediums to explore and express her ancestral artwork through a number of contemporary ways.

Chase Gray is a 2-spirit Musqueam and Tsimshian artist living in their traditional xʷməθkʷəyəm territory, also known as Vancouver, BC. Growing up, he was always surrounded by culture and art, particularly Tsimshian dance and Formline design. Through time, learning, and understanding, Chase has developed a separate Coast Salish design style, which he now uses to represent xʷməθkʷəyəm art within xʷməθkʷəyəm territory. Much of Chase’s art features bright colours, nostalgia, and queer representation as recurring themes, as he hopes to spread the joy of each community he is a part of.

It’s important to change the narratives around who has the right to access spaces and whose voices are valuable.

I wanted to make a place where we share between each other things that shouldn’t be secret when it comes to our survival and prosperity.

Knowledge stewardship from an Indigenous perspective is the role of an entire community.

Spaces like western education, academia, government, policy, etc. actively gatekeep knowledge and the way it is seen and accessed by society.

Archibald, Jo-Ann, et al , editors Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. ZED Books Ltd, 2019.

Buck, Wilfred. Kitcikisik (Great Sky): Tellings That Fill the Night Sky. Indigenous Education Press, 2021

--. Tipiskawi Kisik: Night Sky Star Stories. Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre Inc., 2018.

Dodge, Ernest S “ETHNOLOGY AND ETHNOGRAPHY: The Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada. Wilson D. Wallis and Ruth Sawtell Wallis.” American Anthropologist, vol. 57, no. 6, 1955, pp. 1311–13. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1955.57.6.02a00300.

Dr Margaret Wickens Pearce Coming Home: To Indigenous Place Names in Canada. Canadian–American Center, The University of Maine Orono, Maine, USA, 2017, https://umaine.edu/canam/publications/cominghome-map/

Dunsmore, Amanda, and Matthew Martin. “Art of the Table.” NGV, 27 February 2014, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/art-of-the-table/. Accessed 26 September 2023.

Francis, Bernie, and John Hewson The Mi’kmaw Grammar of Father Pacifique: New Ediiton. Cape Breton University Press, 2016. Open WorldCat, https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/p ublicfullrecord.aspx?p=4814055.

Gaudet, Janice Cindy “Keeoukaywin: The Visiting Way - Fostering an Indigenous Research Methodology.” aboriginal policy studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2019, pp. 47-64. University of Alberta, Campus Saint-Jean, https://journals library ualberta ca/aps/index php/ap s/article/view/29336/pdf Accessed 26 09 2023

Gilhuis, Nicole Dannielle. Colonial Ghosts: Mi’kmaq Adoption, Daily Practice & the Alternate Atlantic, 1600-1763. University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Open WorldCat, https://escholarship org/uc/item/30c3v1cz

Kochems, L. M., and C. Callender. “The North American berdache.” Current Anthropology, vol. 24, no. 4, 1983, pp. 443-470. https://doi org/10 1086/203030, https://doi org/10 1086/203030

Landscape and Place Names. Directed by Acadia University, 2021. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=3ClZmLwdlu4

Lee, Annette S., et al. Ojibwe Sky S Constellation Guidebook: An Intr Ojibwe Star Knowledge. Native S 2014. Open WorldCat, http://web.stcloudstate.edu/asle AP/home.html.

Marshall, Lillian. Muin Aqq l’uiknek Ntuksuinu’k: Mi’kmawey Tepkike Musikiskey a’tukwaqn (Muin and Bird Hunters). Nimbus Publishing 2017

Mi’kmaw Place Names Digital Atl

https://placenames.mapdev.ca/. Acce 2023

“Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Cent Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centr https://www.mikmaweydebert.ca/hom 11 Oct. 2023.

Morgenstern, Tyler Colonial Recurs Decolonial Maneuver in the Cybe Diaspora. Peer reviewed|Thesis/diss 2021, pp. 289-290. UC Santa Barba Theses and Dissertations, UC Santa B https://escholarship org/uc/item/62t4

Morton, Ron, and Carl Gawboy. Talk Geology and 10,000 Years of Nati American Tradition in the Lake S Region. 1st University of Minnesota P University of Minnesota Press, 2003 WorldCat, http://site ebrary com/id/1

Nixon, Lindsay, and Cowley Abbott “Making Space in Indigenous Art for Bull Dykes and Gender Weirdos.” Canadian Art, 20 April 2017, https://canadianart.ca/essays/making-space-inindigenous-art-for-bull-dykes-and-genderweirdos/. Accessed 26 September 2023.

Perry, B., and R. Scrivens. “A Climate for Hate? An Exploration of the Right-Wing Extremist Landscape in Canada.” Crit Crim, vol. 26, no. 2, 2018, pp. 169-187. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-018-9394-y. Accessed 26 09 2023

Proulx, Mikhel. “CyberPowWow: Digital Natives and the First Wave of Online Publication / CyberPowWow: les Autochtones à l’ère numérique et la première vague de publications en ligne.” Journal of Canadian Art History, vol. 36, no. 1, 2015, pp. 203-216. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90021458.

Robertson, Marion. Rock Drawings of the Micmac Indians. Nova Scotia Museum, 1973.

Sable, Trudy, et al. The Language of This Land, Mi’kma’ki. Cape Breton University Press, 2012.

--. The Language of This Land, Mi’kma’ki. Cape Breton University Press, 2012.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai, et al , editors Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. Routledge, 2019. Open WorldCat, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx? direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN =1776302

Whitehead, Ruth Holmes. Stories from the six worlds: Micmac legends. Nimbus, 1988.

Stoddard, Natalie B. “The MicMac Indians of Nova Scotia ” Mcculoch Centre, Halifax: The Nova Scotia Museum, 1966, https://mccullochcentre.ca/portals/80/articles/Trad itional%20eating%20habits%20of%20Mikmaq.pdf

. Accessed 26 09 2023.

Taunton, Carla. Indigenous Art: New Media and the Digital. Edited by Heather Igloliorte and Julie Nagam, Toronto, Public, 2016.

Vickers, Ben, and Kenric McDowell, editors. Atlas of Anomalous AI. Lawson Publishing Limited, 2020.

Michelle Beausejour, Sol Higgins, Field Liberty, Millie Robertson, Kelsey Whissel, Kaitlyn Wilcox, Savannah Simeoni, Stephanie Jeremie, Mel Compton, Katsitsanoron Beauchamp, Brooke Rice, Julia Giraudi, Farah Talaat, Emily Gove, Miriam Arbus, David Han, Joshua Conrad, Chris Gismondi, Nathan Clark, Fallon Simard, Natalie King, Kaya Joan, Alex Jacobs-Blum, Aiden Gillis, Belinda Kwan, Emily Peltier, Karina Iskandarsjah, Suzanne Barry, John R. Sylliboy, Cole Kippenhuck, Avery Velez, Sabrina Muise, Alivia Moore, Rox Letiec, Laureen Blu Waters, Eliza Knockwood