Founded in 2008, Canadian Roots Exchange is a national Indigenous youth-led nonprofit and registered charity (832296602RR0001) We envision a future where Indigenous youth are empowered and connected as dynamic leaders in vibrant and thriving communities. We collaborate with communities to provide programs, grants and opportunities that are grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing and being and designed to strengthen and amplify the voices of Indigenous youth.

In the 2019 federal budget, the Government of Canada named CRE as a leading Indigenous Youth organization to take up TRC Call to Action 66 for reconciliation and committed federal funding for a pilot project of $15.2 million over three years (2019/2020 - 2022/2023), with a recent extension of $12.5 million over two years to continue our work on the TRC Call to Action 66 pilot. Budget 2019 set the goal of the pilot project as ensuring that “the voices of First Nations, Inuit and Métis are heard and to support Indigenous youth reconciliation initiatives” Funding supports the establishment of a distinctions-based national network of Indigenous youth, helps ensure that Government of Canada policies and programs are informed by the diverse voices of Indigenous youth, and provides support to community events, gatherings for Indigenous youth and reconciliation-focused community-based Indigenous youth activities, etc. Since that time CRE has grown exponentially with offices in Toronto and Ottawa, ON and over 50 staff members (80% self-identify as Indigenous) working remotely from coast to coast

Centering Indigenous youth perspectives, we have 7 deeply held principles that guide us in our work and in the way in which we relate to each other:

Impact of Budget 2019

Budget 2019 set the goal of the pilot project as ensuring that “the voices of First Nations, Inuit and Métis are heard and to support Indigenous youth reconciliation initiatives” Funding will support the establishment of a distinctions-based national network of Indigenous youth, help ensure that Government of Canada policies and programs are informed by the diverse voices of Indigenous youth, and provide support to community events, gatherings for Indigenous youth and reconciliationfocused community-based Indigenous youth activities. Here are just some of the impacts Budget 2019 had between April 2019- October 2022, and across 23 unique programs:

In Fall 2020, CRE had a total national economic impact of $137 million

In December 2021 the opportunity to submit a proposal to the Department of Justice Canada’s Call for Proposals regarding the UNDRIP Action Plan was shared with CRE in hopes we could support in ensuring that Indigenous youth voices are meaningfully included in the process

CRE has a wide range of experience running successful engagement sessions. CRE’s commitment to active, ethical engagement with Indigenous youth is expressed in our Engagement Framework, and is built on several key guiding principles. As an organization that exists as a platform for amplifying the voices of Indigenous youth, we set these same standards for any agency or government looking to engage with Indigenous youth through CRE.

Through the guidance of our Framework, engagements are not only successful, but are effective and meaningful sessions that provide space for Indigenous youth to express their voices and feel heard. As such, following the submission of a proposal to the Department of Justice in February 2022, CRE moved forward with the planning of our engagement using a number of methodologies outlined in section 2.2 that would seek to provide a platform for Indigenous youth to share their voices in a meaningful way

CRE thanks the Elders who supported us over the past months and guided us through the engagement process in a good way, grounded in culture and community.

In order to meet the goals of the engagement and to ensure it was guided by community priorities, subject matter experts were asked to support in the form of an advisory committee Members of this committee included Brenda Gunn, Chloe Pictou, Jasleen Jawanda, Jukipa Kotierk, and Riley Yesno We are grateful for all of the knowledge and guidance each member provided throughout the course of the engagement. Informed by this committee, and in order to engage as many youth as possible, four main modes of story gathering were chosen, outlined below.

In order to reach a wider audience, with specific attention focused to reaching Inuit youth in the north, CRE hosted an in-person forum in Iqaluit, Nunavut in partnership with Ivviulutit, a i ti th t t f Two-Spirit and LGBTQQIA+ y we also hosted a communit outreached in the commun with local youth.

Sharing circles create a safe space for participants to speak freely regarding their experiences This approach has been used in research associated with healing, most notably with Indigenous groups. The open-structured method ensures that others are listening, allowing for participants to take the lead in developing the direction of the circle, thus giving a sense of empowerment and trust within the circle Further, this method removes the historical power hierarchies that have been imbued within western research practices which have been used with Indigenous groups. Most importantly, this approach emphasizes the element of storytelling, a practice that is so highly valued among Indigenous cultures.

We acknowledge and are grateful for the partnerships we built with Ivviulutit and all the volunteers that supported the forum.

Policy hackathons by their nature, present an opportunity to empower and educate all in the same space, while fostering connections with other like-minded youth. Across 5 sessions over 2 weekends, youth come together guided by their mentors to write policy proposals and prepare for their presentations to judges on the final day. Supported by an introductory learners package, and subject matter expert sessions throughout, CRE prioritizes creating a supportive virtual learning environment that enhances youth’s policy capacity in critical analysis, change-making, and reconciliation. An Elder is present throughout the event to ground the space in ceremony, and to provide ongoing support to participants. We ensure all dialogue happens on a foundation that centers safety, identity, and Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

To accommodate those who weren’t able to participate in the hackathon or sharing circles, CRE also circulated a survey online. Our other methods of engagement largely focused on qualitative metrics, and creating this survey provided the opportunity to both compliment that data with additional focused quantitative data, as well as increase the number of youth we were able to reach throughout the engagement

Across all sessions, CRE engaged with 183 youth from coast to coast to coast. The majority of the youth were from Ontario (27%) and Nunavut (24%) Most youth (67%) were in urban areas, with rural, remote, and on-reserve youth comprising 7%,17%, 7% of the youth we engaged with, respectively.

Most of the participants self-identified as First Nation (55%), followed by Inuit (30%) and Métis (15%) - these numbers include participants who identified with more than one Indigenous community. The average age of participants was 24.

The majority of the youth identified as cis-gender women (51%), with 23% identifying as TwoSpirit, 13% as cis-gender men, and 12% as non-binary Multiple youth (10%) identified with more than one gender, and over half (57%) identified with one or more sexualities under the 2SLGBTQIA+ umbrella. Additionally, 43% of youth respondents identified with having one or more disabilities

As a national Indigenous youth-led organization, our goal is to obtain representation from across Canada in our engagements. However, it is important to note that this engagement had gaps in representation from the provinces of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island

CRE partnered with Ivviulutit, a grassroots organization, to host a one day in-person forum in Iqaluit, Nunavut on September 28th. The forum engaged a total of 33 Indigenous youth in meaningful conversations regarding their needs and priorities as Inuit and non-Inuit Indigenous youth living in Inuit Nunangat, and how this is tied to implementing UNDRIP in a culturally specific way. The forum was prefaced by a community gathering on the evening of September 27th which brought together youth participants and community members through country food (traditional Inuit food), Inuit games and music. It provided the youth and community members with an opportunity to get to know CRE as an organization, and the staff who would be leading the forum in a culturally relevant way

The forum was opened and closed by Annie Petaulassie, led by three CRE staff, and included English and Inuktitut translators. Each staff facilitated three separate engagement circles. The questions were posed, and youth had the opportunity to engage in open dialogue with the staff and in conversation with one another. Before beginning the engagement portion of the session, youth were provided with a brief lesson on UNDRIP to understand the context of the questions that would be asked CRE staff designed the discussion questions in a way that were both accessible, and relevant to participants Indigenous youth were invited to speak on their experiences in the following areas:

Theme 1 - Serving and Reflecting the Voices of Indigenous Youth

Including: discussion of most urgent needs in their community and addressing some of the socio-economic barriers they currently face.

Theme 2 - Community Capacity and Empowerment

Including: distinctions-based needs and community-based leadership and self-determination; envisioning what a strong community looks like; reflecting on discrimination participants have experienced or seen in their communities and how this impedes community empowerment.

Theme 3 - Evaluation and Accountability

Including: indicators of successful UNDRIP implementation; oversight on UNDRIPs implementation; and the Government of Canada’s reporting to Indigenous youth about the progress of UNDRIP in Inuit Nunangat

When asked to reflect on how UNDRIP could or should elevate their rights, participants spoke strongly to four key pillars: access to language, affordable food, affordable housing, and culturally safe health services. Many participants pointed out the gap between Inuit access to these pillars as compared to non-Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat, revealing the ways in which Inuit are too often not given priority in their own homelands. They provided their own personal experiences, observations, and hope for the future in order to answer this question.

Participants spoke to the desire for more Inuktitut-only speaking schools and spaces in Inuit Nunangat generally and in Iqaluit specifically, which would mean more Inuk and Inuktitut-speaking teachers Many shared their experience with teachers from “down south” and/or the turnover rate of southern teachers, with many participants speaking to the negative effect this has on children and youth. They also vocalized the need for nonInuit teachers coming to Inuit Nunangat to work to be enrolled in cultural competency courses, and the importance of getting to know the community as well.

They spoke about the need for stricter Federal Inuktitut policies, and the disparities for knowledge-sharing and learning Inuktitut compared to French. Many participants were disappointed by the political/governmental eagerness to build a French school for nonInuit as supposed to a new school for Inuit on their homelands. They also spoke about there not being a ‘one size’ fits all approach in the school system because while some youth speak Inuktitut at home fluently, others do not As a result, there was a suggestion for a focus on individualizing the school to prioritize Inuktitut but also provide English supports as well.

Access to Affordable Food Youth participants emphasized the extremely unreasonable food prices that exist in Inuit Nunangat as well as the lack of nutritious food that is reasonably priced They provided some alternative solutions including: an increase in funding and programming for hunters as supplies are extremely expensive; an overall right to live off the land undisrupted from colonial projects that interfere with wildlife; and food subsidy programs for large families.

Access to Affordable Housing Participants emphasized the disparity in housing between Inuit and Non-Inuit, where southerners are afforded housing and Inuit are left in conditions that include overcrowding, and long waitlists. They spoke to the housing crisis that exists because there are only so many apartments and houses for a growing amount of people, including Inuit and Non-Inuit They felt that Inuit should be prioritized

“Living in Iqaluit or anywhere in Inuit Nunangat, Inuit should be prioritized. It doesn’t make sense to me why Inuit are homeless and without proper food. We lived here with all those things at one point. UNDRIP should help us go back to our old way of life, or at least help find a mix between the two.

Participants spoke to the racism many of them and their families have experienced in the health care system They placed an emphasis on the disparities between Inuit and NonInuit when seeking medical services, and how they must be strategic in order to get health care professionals to take them seriously. The spoke to the isolation many Inuit feels when having to be medevacked outside of their home and communities, and the cultural barriers that can occur in the south. As a solution, they spoke to the need for preliminary cultural competency tests and training that are needed for health care professionals before coming to Inuit Nunangat They spoke about the need for there to be more culturally relevant mental health treatment centres and treatment centres for those with addictions. Youth spoke to current programs that they know exist and should be spread throughout Inuit Nunangat.

Participants placed an emphasis on returning to Inuit value systems, particularly Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (traditional knowledge) principles as the basis for community empowerment. To them, this includes:

healing; coming together as community members to support one another; access to culture and language; reconnecting with the land; and self-determination

To realize these principles, there was discussion around access to funds and support to get to the point of establishing an empowered community. They spoke to the fact that the knowledge already exists with Elders, youth, and Inuit living in their communities, but it just needs to be scaled In order to implement Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, participants emphasized the importance of reconnecting with the land and the importance of Inuktitut as a basis for a renewed community connection.

There was a clear need and want for all services in Inuit Nunangat to be available in Inuktitut. Additionally, forum participants called for there to be more extensive Inuktitut speaking programs, and mandatory classes for people who come from outside Inuit Nunangat. Some spoke of the importance of Inuktitut to be able to learn and relate to one another from an Inuit perspective, and to be able to connect with and learn from Elders Inuktitut would create an avenue for youth to create strong kinship ties with one another, and their culture, which would in turn create strong confident leaders.

Youth placed a huge emphasis on the land being the foundational source of learning, language, and kinship In order to learn Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, it is crucial for youth and community members to return to the land with one another. Returning to the land would create spaces for storytelling, sharing of knowledge, food, inclusion, and understanding. The land brings purpose and grounding for youth to be able to break cycles and feel supported in the process.

In-Person Forum Participant

Youth spoke to some of the discrimination faced in their communities by service providers, particularly police officers and health care professionals. Participants expressed that the way that these services are delivered adds to the cycles of generational trauma instead of bringing forth healing Some participants articulated their personal experiences in which they, family or community members were met with excessive physical violence by police because they were Inuk. This ultimately leads to Inuit feeling undignified as it takes their power away and leaves them vulnerable

They also spoke of the dismissal by health care professionals and being ‘talked down on,’ treated with dismissiveness and with a lack of empathy Many participants spoke about some traumatic experiences of community members going to the hospital, constantly being dismissed, and then later passing away. They also spoke of the dismissal of Inuit with addictions in the health care system, and

indignity that comes with this

the

“

We need to start reconnecting with land again. So many youth feel alone but you don’t feel like that when you’re on the land. It’s a good way to connect with other people and to learn.

The Indigenous youth who participated in the forum created clear suggestions to evaluate if UNDRIP is being implemented successfully These include:

Increase in overall Inuit quality of life;

Stronger Inuktitut policies and programs;

Stronger Inuit based education;

More programs to reconnect to land;

More affordable housing;

More nutritious and affordable food;

Cultural safety training and accountability structures for health care professionals who come up north;

Cultural training and accountability structures for police officers who come up north Inuit coming first in communities;

More culturally relevant mental health services;

More culturally relevant addictions and healing services; and

A change in statistics related to addictions, suicide rates, overcrowding, education, and employment

When asked who should oversee the implementation of UNDRIP and evaluate its success, youth asserted that this should include several committees spread throughout Inuit Nunangat. This would include community leaders, Elders, and youth. Some youth mentioned creating a youth council to oversee this through the National Inuit Youth Council through Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

When asked how youth would like to stay informed on the UNDRIP Action Plan, many spoke to wanting to see updates quarterly They said they would like to see a wide range of updates including through social media to ensure information is being disseminated in a way that is accessible and straightforward. They emphasized of the importance of updates being in both English and Inuktitut and being accessible via radio or television in order to reach Elders in communities as well. The recommended news station was CBC north as a conduit to disseminate updates to Inuit Nunangat broadly.

Below, recommendations that emerged from the forum have been grouped into themes.

Serving and Reflecting the Voices of Indigenous Youth

1

The UNDRIP Action Plan should speak to the commitment of allocating funds to Inuit communities that would increase: access to language (within the education system and outside of it); access to land-based cultural practices and learning; access to affordable housing; and access to affordable, healthy foods, as well as traditional foods.

2 To support access to traditional foods, the UNDRIP Action Plan should include funding pots for hunters in Inuit Nunangat

3 The UNDRIP Action Plan should include steps to develop and bolster food subsidy programs for large families in Inuit Nunangat.

4 The UNDRIP Action Plan should include measures to support Inuit-led initiatives designed for reconnecting with the land as a basis for community empowerment and healing.

5

The UNDRIP Action Plan must meaningfully address the disparities between Inuit/Indigenous folks and non-Indigenous/Non Inuit in Inuit Nunangat. Inuit should always come first in their own homelands.

Improving Relations Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Peoples

6 The UNDRIP Action Plan should include steps to implement mandatory, ongoing cultural safety training for non-Inuit health care, education, and law enforcement professionals, and accountability structures for racism and discrimination within these institutions

7 The UNDRIP Action Plan should include steps supporting stronger Inuktitut policies and Inuktitut programs

In determining whether UNDRIP implementation is improving the lives of Inuit, evaluation framework should include the following as metrics for success:

Increase in overall Inuit quality of life;

Stronger Inuktitut policies and programs; Stronger Inuit based education;

More programs to reconnect to land;

More affordable housing;

More nutritious and affordable food; Cultural safety training and accountability structures for health care professionals who come up north; Cultural training and accountability structures for police officers who come up north; Inuit coming first in communities;

More culturally relevant mental health services;

More culturally relevant addictions and healing services; and A change in statistics regarding: Addictions, suicide rates, overcrowding, education, employment.

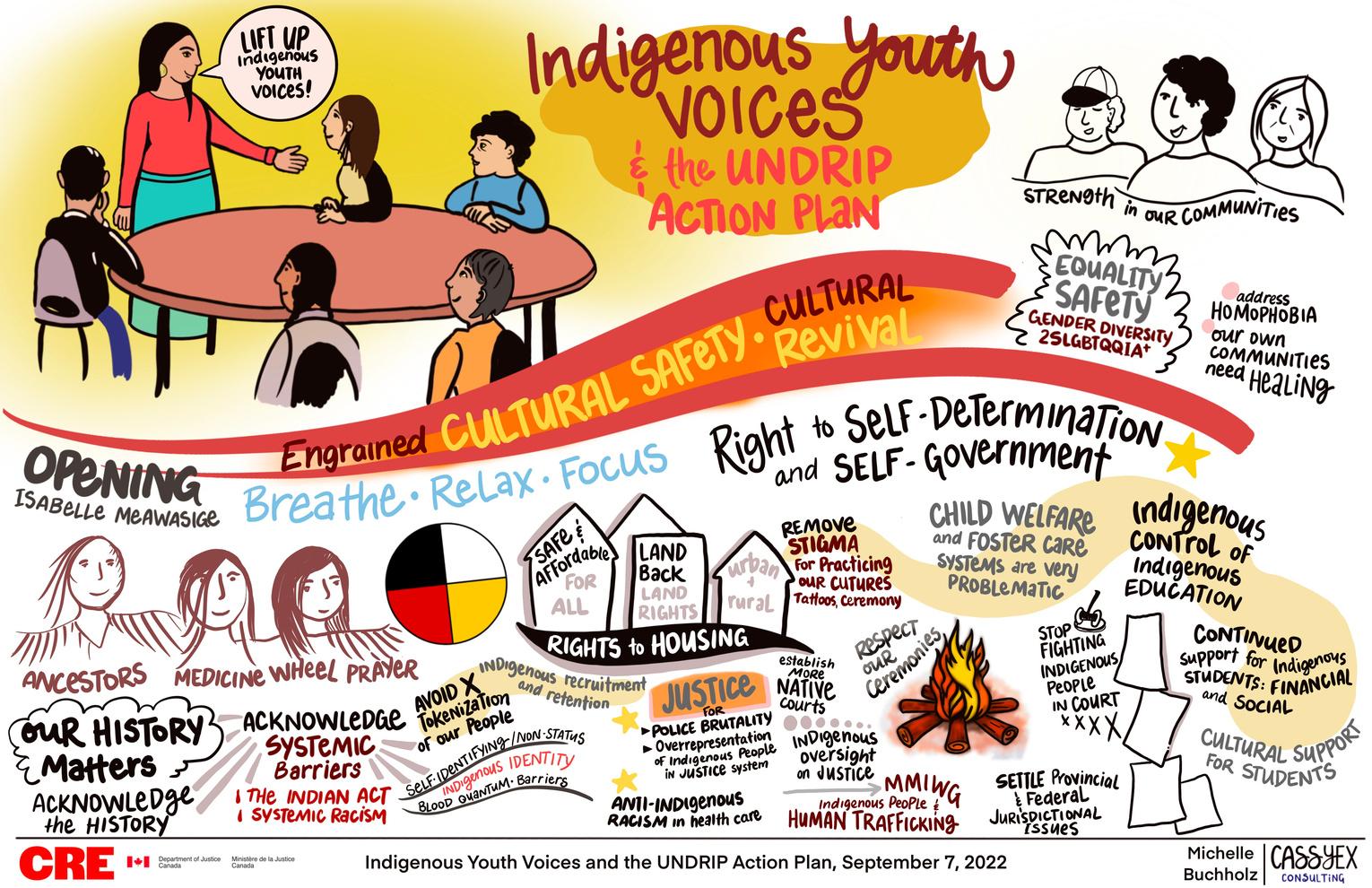

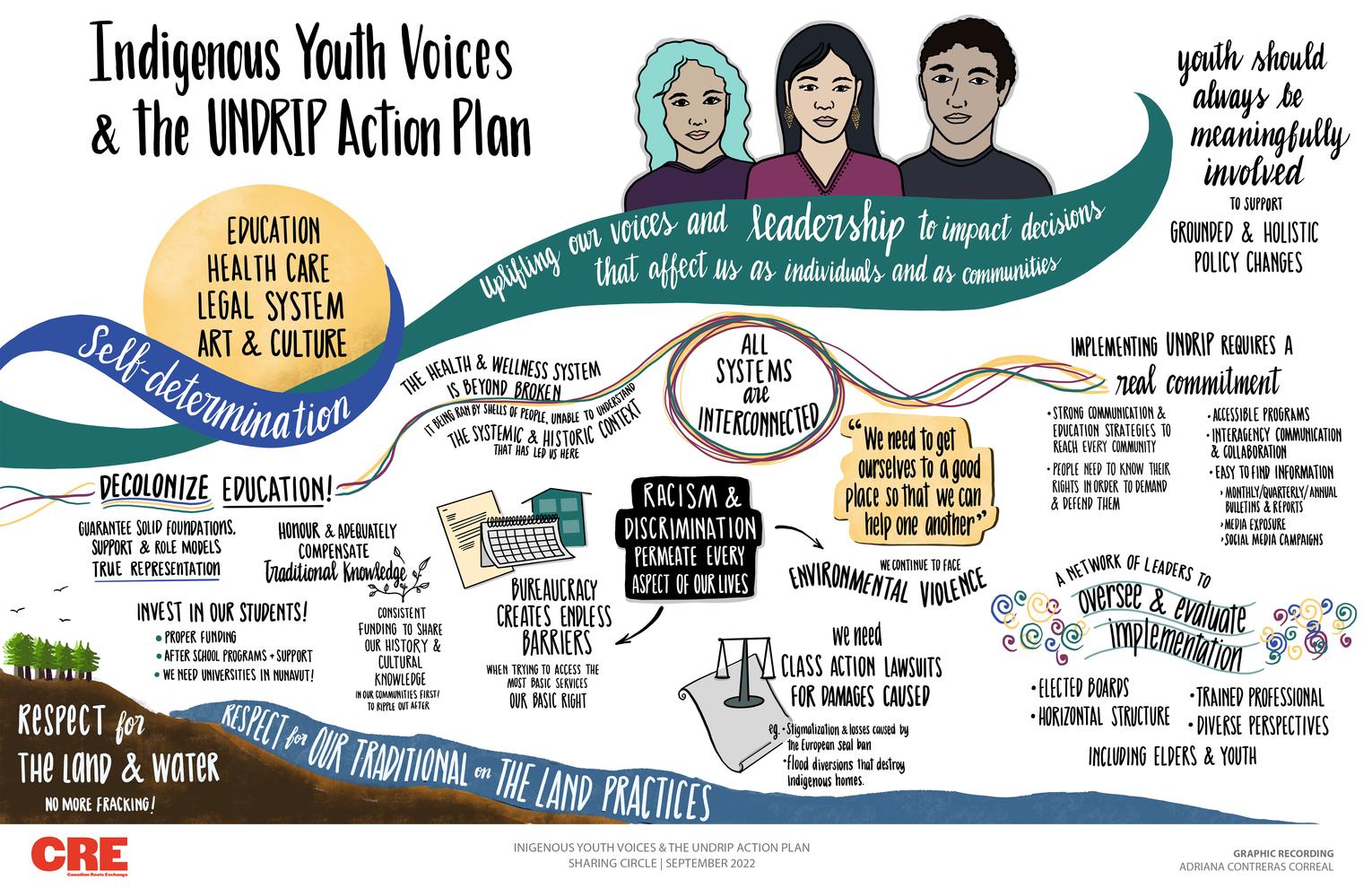

CRE held four two-hour virtual sharing circles throughout September, engaging a total of 52 youth in substantive discussions about their needs and priorities tied to implementing UNDRIP meaningfully Sharing Circles were opened and closed by Elder Isabelle Meawasige and facilitated by two CRE staff With each question posed, participants were free to unmute themselves and speak openly, type their thoughts into the chat, or send their answers directly to CRE staff if they felt nervous or shy. Each circle also included graphic recording by Michelle Buchholz (September 7 and 13) and Adriana Contreras (September 20 and 21), and their important work has been embedded in this report.

Upon sign-up, participants were provided with a learner's package that included information on UNDRIP and on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA). With Sections 5, 6, and 7 of the UNDA containing the Government of Canada's legal obligations, CRE staff crafted the questions to foster discussion about realizing those commitments from the perspective of Indigenous youth. Indigenous youth were invited to lend their insights in the following key areas:

Theme 1 - Serving and Reflecting the Voices of Indigenous Youth

Including: where UNDRIP implementation should start; what rights are the most urgently needing enforcement and elevation; and UNDRIP’s alignment or misalignment with existing Indigenous rights law and policy

Theme 2 - Action Plan

Including: how to end anti-Indigenous racism, violence and discrimination; intersectional discrimination; and concrete steps to advance reconciliation and improve Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations

Theme 3 - Community Capacity and Empowerment

Including: distinctions-based needs and community-based leadership and self-determination

Including: indicators of UNDRIP’s success; jurisdictional cooperation; oversight of UNDRIP’s implementation; and the Government of Canada’s reporting to Indigenous youth about the progress of UNDRIP implementation

A full list of the sharing circle questions can be found in Appendix B. Below, the discussions from the Sharing Circles has been summarized and further broken down based on those themes, and all recommendations based on the sharing circle discussions can be found in the final section of this report.

When asked how their lives would change if UNDRIP were perfectly implemented, Indigenous youth spoke to general quality of life improvements while giving clear direction about what that should look like. A general increase in access to safe healthcare services, education opportunities, and employment opportunities were common points of discussion during all the sharing circles Many participants pointed to the need to address these gaps regardless of what context they were living in (urban, rural, on-reserve, northern, etc.), and a particular need for better and more services outside of Toronto and the GTA was voiced by many participants. Overall infrastructure gaps in rural and/or reserve communities – such as those related to clean water and availability of cellular service – were also clearly identified by youth as being a high priority with implications for safety, health, and mental wellness

In the area of healthcare reform & mental health services, sharing circle participants told stories about being unable to access care when leaving their communities, particularly when the move involved crossing provincial and/or territorial borders. Further, healthcare services that are available were reported to frequently be unsafe spaces, staffed by health care practitioners that were overtly racist and/or not equipped with knowledge about Indigenous-specific health realities to treat them effectively. The youth we spoke to were also firm that social determinants of health must be recalibrated to reflect Indigenous realities and can then be used as performance indicators for UNDRIP’s success. Many participants shared the desire to see negative mental health statistics reverse course, such as those related to Indigenous youth suicide

Relatedly, Indigenous youth reported a range of difficulties in completing secondary school and in accessing post-secondary education (PSE). Many were denied funding to attend or return to PSE for reasons including being too old, poor grades during their first attempt, not being sponsored by their community, and/or being denied student loans Specific barriers were also articulated by Inuit participants living outside of their home territory, making it more difficult to secure financial support. Relatedly, many participants expressed how the lack of transition supports between high school and PSE negatively impacted their early PSE experiences. These barriers are only compounded by anti-Indigenous racism encountered in high school, college, and university from teachers, faculty, administrators, and in curriculum itself

Much of the sharing circle discussions about health care and education gaps naturally flowed into broader conversations about anti-Indigenous racism in those sectors, as well as at work, and when seeking services more generally. Participants specifically spoke to the need for workplaces to be more culturally aware by allowing days off for ceremony, and not discriminating against Indigenous workers and job applicants with traditional tattoos such as facial tattoos. Because they grew up disconnected from their Métis culture and community, one participant noted that for many years, racism was the only lens through which they understood their own Indigenous identity.

In thinking through how a meaningful implementation of UNDRIP could change their lives, participants had robust discussions about rights, community autonomy, and selfdetermination. Youth were firm on the need for their nations to be in control of their own governance structures and free to create and reform the laws that impact them as needed. They spoke to the need to dissolve the status / blood quantum system, support selfgovernance, and many asserted that treaty rights need to be better understood and enforced on the part of settler Canada Youth drew a clear line between bolstering Indigenous rights and self-determination to cultural reclamation and revitalization, especially in terms of land access and land-based cultural practices, and language transmission. Many participants drew a further connection to how this would contribute to environmental sustainability and mitigate the ongoing effects of climate change, which disproportionately impacts Indigenous communities

Finally, many youth thinking through the barriers they have faced in life spoke to the utter devastation and harm created by both the criminal justice and child welfare systems In terms of the child welfare system, participants told stories about the ways in which their lives and their families’ lives have been harmed and destabilized through policies and processes including but are not limited to forcible removals, visitations, birth alerts, and loss of supports due to “aging out of care.” One participant also pointed to the ways in which the Freedom of Information Act processes harms families and survivors of the child welfare system by creating a cumbersome process that requires those who have been harmed by the system to pay the government for information about the harm that has been inflicted upon them by them. Moreover, all of these harms are interlaced with the abuses Indigenous children and youth can and have faced being forced to live with abusive families and/or in under-resourced, poorly managed group homes. The criminalization of Indigenous youth can be similarly devastating to every facet of life, with many participants pointing to the need for more robust and culturally safe diversion programs, better processes for expunging youth criminal records, and general lack of available legal supports for Indigenous youth.

Throughout these discussions, participants outlined their expectations that a meaningfully implemented UNDRIP would mean seeing negative statistics reverse course, such as those related to the prevalence of poverty, homelessness, poor health, unemployment, and education The youth we spoke to were also clear that all of these issues (as well as the ones outlined above) are interconnected and massively impactful on Indigenous wellness in general. Youth also underscored the potential generational impacts of tearing down the barriers they grew up with, emphasizing that Indigenous children should grow up safe, supported, connected to community, and with an understanding of their inherent worth.

“

It’s things like homelessness and poverty that shouldn’t exist if UNDRIP was implemented the right way. There would be more community safety. Sharing Circle Participant

Across all sharing circles, laws and policies related to rights, autonomy, and selfdetermination were identified as the most urgent reform. Key issues within this discussion include replacing the Indian Act and status systems; Indigenous-led justice systems; full selfgovernance; and enforcement of true free, prior, and reformed consent Youth were clear that their nations should be free to determine their own membership and citizenship and spoke to the urgent need for leaders in their nations to be equal partners in the law and policy decision-making that directly impacts them. Autonomy and self-determination were also closely tied by the participants to language and culture revitalization and land reclamation

Youth also spoke to the urgent need for healthcare and education reform and funding, and clearly articulated the ways that the current healthcare and education systems have been sites of violence and racism against them Participants cited the need for more healthcare navigators, described being tokenized in both spaces, and acknowledged that services are particularly bad in smaller provinces on the east coast. On approaches to healthcare, many youth also pointed to the need for decolonizing healthcare by pursuing more wholistic healing models that include spiritual and environmental health considerations Several youth also expressed the urgent need to go beyond nursing stations on reserve and in isolated areas, and youth in more urban areas told stories about being denied care due to being homeless.

Many participants also spoke to the need for criminal justice reform and the decriminalization of Indigenous youth Youth articulated the urgency of ensuring that land defenders are never forcibly removed from their lands and criminalized for protecting their lands and reiterated the need for police and workers in the criminal justice system to be better educated about Indigenous rights and trained in anti-Indigenous racism. A better accountability system is also needed for police and those in the criminal justice system for discriminating and/or brutalizing Indigenous people moving through the system, and for cases of lethal neglect while in custody

Many participants also spoke enthusiastically about the need to decriminalize drug-related offenses and shift from being a criminal justice matter to a health matter. Some participants relatedly spoke to the ways in which the criminal justice system is overly entwined with the child welfare system, another institution that has been endlessly harmful in derailing Indigenous youth’s lives.

“

If UNDRIP were implemented perfectly, the ways in which wellness would be impacted would be astronomical because we would stop seeing our people die from anything other than living a full life.

Participants also asserted that no one should be criminalized for being forced to sleep on the street, while agreeing that Indigenous housing, homelessness, and poverty are extremely urgent issues needing immediate attention and resources. Some youth spoke to their experiences working or volunteering in understaffed, over-capacity homeless shelters and the need for more barrier-free funding for agencies providing those services, as well as the need for more supports and funding for Indigenous housing generally Finally, youth spoke to the urgent need for more resources to be put towards safety of Indigenous people, especially human trafficking victims and victims of domestic abuse, and the need for more measures to remove and/or rehabilitate predators within communities.

In sharing stories about discrimination and racism they faced as Indigenous youth, the youth we spoke to identified overt racism from officials and staff at every level of the criminal justice, education, healthcare, and mental healthcare systems One participant seeking safety from the police was advised to leave the province to escape domestic abuse and stalking, and several more participants described being verbally assaulted and profiled by RCMP officers. All participants reiterated again the need for education about Indigenous rights anti-racism education that debunks dehumanizing stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. Youth shared harrowing stories about being mistreated and violated in healthcare contexts, having just given birth, or in the midst of mental health crises Youth further drew attention to the need for better services through NIHB, and the need for dental services to be covered Best

In speaking to best practices for combatting racism, violence, and discrimination, youth cited community-based healing centres, revitalization of cultural practices and land-based activities, and reconciliation-focused education. Throughout this discussion, youth praised leadership related to transparency, resilience, and tenacity in supporting their community through relationship-building. Asked about what they have seen leaders do to successfully combat racism and discrimination, one participant spoke to how impactful it was to simply see a chief who was a woman elected, and others spoke to respecting their community leaders who do education work with non-Indigenous people.

The law is often used against us. Sharing

In discussing discrimination and racism specific to their intersecting identities, youth described discrimination from both within and outside the community as a result of being Two-Spirit and excluded from certain ceremonies as a result. Afro-Indigenous youth further described exclusion from all communities they belonged to due to stigma and stereotyping, as well as difficulty securing different kinds of government funds and supports due to their mixed-heritage. Several participants called attention to the unfairness of the Post-Secondary Student Support Program in terms of exclusion of some Indigenous peoples, and to the difficulty in accessing cultural practices growing up in or moving to urban areas.

Asked what concrete steps need to be taken to promote reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, youth we spoke to suggested a range of practical measures within the realm of building and removing memorials Among the suggestions were: Youth also spoke to the clear need for concrete measures such as reducing the cost of food, especially in rural, reserve, and northern areas, and the need to ensure that all Indigenous people have access to clean water and healthcare, no matter where they live

Memorial installations at every residential school mass grave / burial site; Continuing to remove statues commemorating colonizers; and Removing the royal family from Canada’s money.

In speaking overall to how the concept of reconciliation has changed over the last decade, youth agreed that it has come to feel more like a slogan connected to recognizing wrongs without fixing them, to the extent that nearly all participants expressed skepticism about the Government of Canada’s ability to implement UNDRIP in a way that would tangibly improve their lives and their communities

“

"

Actual work needs to be done to change the system and infrastructures that are result of colonial actions.

Sharing Circle Participant

In discussing what an empowered community looks like, youth were emphatic that empowerment means sovereignty, independence, self-sufficiency, self-governance, and autonomy. Participants also specified the need for community sovereignty to include internal community justice and policing systems and identified the need for independence in relation to energy, housing, and infrastructure..

Youth also described empowered communities as ones with the resources, structures, and education necessary to support, protect, and include Elders, youth, and Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ people. All these pillars must also be grounded in community connection, mutual respect, and cultural practices Many youth also reiterated their points and recommendations from Theme 1, and spoke to the need for accessible, safe, high-quality supports and services including education, healthcare, and addictions services, no matter where they are living.

The Indigenous youth who participated in our sharing circles suggested clear indicators for evaluating how and whether UNDRIP is being implemented successfully and improving Indigenous peoples’ lives at the ground level These include:

Healthier communities;

Creation of an Indigenous healthcare ombudsman position; Overall increase in quality of life in all communities; Less homelessness and more availability of accessible housing; Growth in understanding of Indigenous rights and realities among the general public; Removing street names commemorating colonial figures; Socio-economic status of Indigenous peoples is at minimum on par with settlers; Increase in positive portrayals of Indigenous people in media; Reversal of statistics related to suicides; Reversal of statistics related to deaths; Reversal of statistics related to substance use; Reversal of statistics related to mental health crises; and Reversal of statistics related to missing and murdered Indigenous women

Youth also asserted that one indicator of the government’s commitment to UNDRIP and elevating Indigenous rights would be the development of respectful, continuous working relationships with their nations, rather than one-off consultations. Relatedly, youth also hold the understanding that if UNDRIP is properly implemented, their nations will have more control of their own resources, and more of a voice in decision-making.

When asked who should oversee the implementation of UNDRIP and evaluate its success in improving the lives of Indigenous people, youth asserted that this is a job for more than one person and agreed that a council, committee, board, or even an entire arms-length agency that includes Elders and Youth should be considered Within this conversation one participant suggested that new electoral ridings be created to correspond to each Indigenous nation, and that those new MPs lead oversight and implementation of UNDRIP. The youth we spoke to were also enthusiastic about continuing to be engaged in this process, expressed that they would be interested in attending future sharing circles about UNDRIP’s implementation.

“

Participants agreed that a yearly written report to parliament is too infrequent for the amount and scope of work that needs to be done in implementing UNDRIP. They expressed that information about UNDRIP’s progress should be completely accessible in every sense – not only should the language be free of jargon and legalese, but youth also expressed that they should not have to go digging in the House of Commons website for the reports Any reporting should be widely available on the social media platforms that youth access the most, widely publicized in mainstream media, and available in as many languages as possible.

Youth also suggested creating an advisory group with the specific mandate of ensuring all Indigenous communities (including youth) are up to date about UNDRIP’s progress and aware of ways they can be involved Finally, youth also emphasized that Prime Minister Trudeau should be leading these updates as a way to continuously reaffirm his own accountability for UNDRIP’s success. Youth suggested the following communication methods for the Government of Canada and the Prime Minister’s Office to provide updates:

Virtual and physical newsletters on a monthly basis; Webinars; Surveys asking communities how UNDRIP implementation is going for them, and regular publication of the results and milestones; A one stop website that is separate from the government website (similar to the TRC website or CBC’s Beyond94); and An UNDRIP update podcast.

“

I won't believe [that the government is implementing UNDRIP successfully] until I see my community or communities around me having a better quality of life. I want to see actual changes rather than another data report.

At the end of each sharing circle, participants were asked how they felt about the discussion and generally whether they felt hopeful about the implementation of UNDRIP. The emotions articulated by nearly all participants were skepticism and a reluctance to believe that the Government of Canada would see the work through in a way that will be impactful at the community level Many expressed doubts that anything substantial would change within their lifetimes, and any hopefulness they expressed was connected specifically to the sense of community they felt at being in a space with other Indigenous youth, talking through these critical issues

To supplement the sharing circles and as a way to ensure that youth who could not attend a sharing circle were included in this important engagement, CRE ran a general survey for approximately eight weeks Youth filling out the survey had access to the same learner’s package given to sharing circle participants, and the survey asked the same questions as the sharing circles (found in Appendix B). As such, the survey questions were broken into the same themes as the sharing circle discussions.

When asked about their priorities regarding UNDRIP implementation, survey respondents spoke to multiple areas where they would first like to see progress made. Of these priorities, the most frequently cited were land rights, healthcare, education, infrastructure, and selfdetermination Youth stressed the importance of accessing their lands for traditional purposes, as well as the need for true Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) In regards to healthcare and education (secondary and PSE), youth said they would like to see more equitable access to these services while also citing the need for these services to be culturally-relevant. For infrastructure, youth most frequently pointed out the need for clean drinking water within Indigenous communities, as well as the need for safe and adequate housing Many also pointed out the need for self-determination, and increased community supports to create the capacity to achieve this

When speaking on obstacles they have faced, youth frequently mentioned facing barriers within institutions such as healthcare and education Most of these concerns stemmed back to inequalities within these systems and related policies, such as not being able to access PSE funding from their communities, not being able to access healthcare where they live, and not being able to access services as a non-status person, or someone living offreserve. Youth were asked what would change, ideally, for them if UNDRIP were implemented perfectly, and many said that these barriers in accessing services and supports would not exist, and at the core, would see healthier communities overall

Measures to end Violence, Discrimination, and Racism Against all Indigenous People Many survey respondents reported instances of racism and discrimination when accessing health care, education, when being a part of the child welfare system, and when dealing with police. Most youth respondents also cited experiencing racism and discrimination from their non-Indigenous peers. In the healthcare system, many youth feel as though their health concerns are not taken seriously as an Indigenous person.

Youth who identified as part of the LGBTQIA2S+ community expressed that they have experienced additional discrimination, often citing that they feel healthcare professionals do not understand how to work with LGBTQIA2S+ folks properly. When talking about discrimination faced in education, youth brought up that not only do they not have equitable access to education, they also face overt racism from PSE professors, often see Indigenous people portrayed incorrectly in lessons (or do not have content on this at all), and that they most often are given content from non-Indigenous points of view When dealing with police, youth reported overtly racist acts by police officers and also cited the need to stop the overpolicing of Indigenous people.

When asked about what they have seen work to combat racism and discrimination, and what reconciliation looks like to them, most youth pointed to education Many expressed the need for anti-racism training for public servants, healthcare workers, education workers, and police. Youth also pointed out the need for Indigenous history education in public schools, starting at a young age

“

" [Healthcare] needs to be a priority, because without our health, the rest of the laws can’t benefit us. Survey Respondent

“

" We deserve and need homes on our own land. Survey Respondent

In talking about what an empowered community looks like, and what their communities need, youth most often cited the need for in-community resources and supports – not just for reserve communities, but with an emphasis on the need for them in urban Indigenous communities. Most youth also said that being connected to their community and their culture is what makes them feel most empowered

When discussing the resources and supports needed by their communities, many indicated that their community needs supports to have the basic needs of the people met (such as having food security), as well as educational resources, support in accessing ceremony and knowledge keepers, on the land programming, mental health and addictions resources, and funding for these supports Youth want to have access to their traditional lands, be able to learn their language, have access to cultural programming, and be connected to their community.

As mentioned in Theme 1, youth often said that the way they will know if the implementation of UNDRIP is working is if their communities are healthier overall. To youth, this includes having access to safe drinking water, seeing lower rates of addiction, seeing lower rates of suicide, and having safe and adequate housing Youth said that they will also know if the implementation of UNDRIP is working if communities begin to exercise the right to self-determination and have the capacity to do so. Many also pointed to the need for the justice system to be reformed and noted that they will know the implementation of UNDRIP is working if there are less Indigenous people in the justice system, less MMIWG2S+, and that the over policing of Indigenous people d oes not exist anymore.

“

An empowered community is a supportive one...they have the power to make decisions for themselves and the resources to follow through.

The majority of youth expressed the need for Indigenous-led oversight of the implementation of UNDRIP, and also that oversight should be done by a group of people, such as a council. Respondents noted that Indigenous youth and Elders should play a significant role within the oversight of this. Many expressed that they believe recurring surveys, or engagements similar to this, for Indigenous youth and communities would be beneficial in the overall monitoring of progress. The need for appropriate representation across Indigenous identities was also expressed, with many saying that they would like to see at a minimum, representation from First Nation, Métis, and Inuit people within the oversight body, as well as representation from across provinces and territories, and inclusion of women and 2SLGBTQQIA+ peoples.

The vast majority of youth said that they believe that reporting should be done more frequently than annually, and that they would like to see progress updates made available through social media and email newsletters Many stressed the importance of ensuring that any updates disseminated be made in an accessible way through using plain language, being made available in Indigenous languages, and being made available through multiple mediums (e.g., Print or video). Most youth expressed that they would like to continue to be engaged in the process of UNDRIP implementation.

Similar to the sharing circles, youth were asked how they feel about the implementation of UNDRIP overall at the end of the survey. While a lot of youth said they feel hopeful about the implementation, many also expressed concerns about it. Some cited overall ambivalence about the process, especially since it is such a large undertaking, while others mentioned specific concerns such as the need for additional protections for LGBTQ2S+ folks under UNDRIP, and potential pushback from non-Indigenous people

Sharing Circle Graphic Recordings by Michelle Buchholz

Sharing Circle Graphic Recordings by Michelle Buchholz

A cornerstone of CRE’s policy hackathons, capacity-building sessions are hosted by a variety of subject matter experts who provide youth with the tools they need to collaborate with their teams to achieved the goals of the hackathon. For this hackathon, we kicked off our sessions with a presentation from Brenda Gunn, a proud Metis woman and law Professor at the University of Manitoba As someone who has been actively involved in the international Indigenous peoples’ movement, including by developing a handbook that is one of the main resources in Canada on understanding the UNDRIP, her session helped build a foundation for participants. On day three, youth heard from Katherine Minich, whose work focuses on the practices of Indigenous self-determination in community, particularly Inuit selfdetermination practices in Nunavut. Katherine shared important insight into the policy writing process to support youth in preparing to write their own briefs for the purpose of the hackathon Youth also heard from Riley Yesno, a queer Anishinaabe writer, researcher, and accomplished public speaker from Eabametoong First Nation, who shared stories and tips about navigating policy spaces as an Anishinaabe youth.

For the hackathon itself, participants were asked to write a policy brief and prepare a presentation exploring each team’s ideas about how the UNDRIP Action Plan should approach eliminating all forms of violence, racism, and discrimination against Indigenous peoples Participants were instructed to consider the specific realities of Elders, youth, children, people with disabilities, women, and gender-diverse and Two-Spirit persons in their answers. They were also encouraged to apply key considerations of self-determination, distinctions-based community needs and accountability to their briefs and presentations. The full case study and prompt questions associated with it can be found in Appendix C.

All policy briefs have been compiled and attached as a separate document, and you can find a summary of each team’s approach below.

Parliamentary Secretary

well as

Honourable

Team 1: Indigenous developed and led First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Parenthood programs to develop capacity in communities and enhance the lives of Indigenous families

Citing the Articles 3, 4, and 10(2) of UNDRIP, as well as the findings of the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Team 1's brief makes a case for community-led early intervention programs for Indigenous parents. The programming they envision is grounded in traditional knowledge and healing practices and draws on clinical

In terms of outcomes, this programming would be a form of violence prevention, and improve social, physical, and mental health outcomes. Specifically, the team cited rates related to the number of Indigenous children in child welfare, infant mortality rates that are twice as high as the non-Indigenous population, and Indigenous parents’ childbirth mortality rate being twice as high as those for non-Indigenous women giving birth. The program suggested by the team would address the racist policies that create these outcomes and the clear gaps in prenatal and maternal crises intervention for Indigenous parents and families. Key factors tied to the program's success are LGBTQ+ inclusion, comprehensive outreach work and relationship building with the serviced communities and government bodies, and analyzing populations based on need

Decrease of Indigenous children in foster care Decrease in unwanted pregnancies, Decrease in rates of death in childbirth

We would like to thank each of our subject matter experts and mentors who guided the youth teams throughout the hackathon. We are grateful for the

Gary Anandasangaree who attended to share a few words with the youth, as

The

Minister David Lametti for sending a video of encouragement to participants. Further, we appreciate the time and commitment of our hackathon judges Rosalie LaBillois and Jake Kennedy.

Build on existing capacity in indigenous communities to improve infant and mother outcomes by improving access to parenthood programs and building partnerships between health care officials and communities to ensure the care provided is culturally relevant and safe

Change suppressive, racist, discriminatory policies that have harmed and/or killed Indigenous people (such as the Evacuation Policy of pregnant Indigenous women at 36-38 weeks in rural or remote communities to deliver babies in an urban setting)

Empower maternal healthcare staff and services with culturally responsive and humility-based skills and teach client-led approaches for self-determination Ensure availability of diverse and inclusive language and options in prenatal and childbirth-related healthcare, including using LGBTQ+ inclusive language in program guidelines and programming to ensure it is applicable to everyone, regardless of their gender identity or sexuality.

Accessible health care for reserves (including building partnerships and allocating funding from various sources to enhance health care programs to be used on reserves, creating mobile health units equipped for prenatal and neonatal checks, infant checks, mother; and incorporating cultural methods into these health units medicines, Elders)

Team 2's brief focuses on responding to Article 14 of UNDRIP, which reaffirms Indigenous peoples’ right to establish and control their own educational institutions and provide education in their own languages and in a method that aligns with their cultural teachings and practices The brief argues that implementing Indigenous and community-led education systems, institutions, and curriculums would address the education, social, and economic gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

In terms of outcomes, the Team 2 argues that the Government of Canada's approval and support of Indigenous-led education would alleviate violence, racism, and discrimination against Indigenous peoples Citing the low graduation rates of First Nations youth compared to the rest of the Canadian population, the brief asserts that provincial education systems do not prioritize the academic success of Indigenous students. This forces communities to develop community-led education initiatives and schools, wherein students can learn cultural practices and language in addition to standardized curriculum. Pointing to Xetólacw Community School as a best practice, Team 2's brief highlights the benefits of such initiatives including supporting the success and preservation of future generations, fostering feelings of belonging and security among the students and community, while also being an exercise in self-determination, resurgence, and resiliency. The direction chosen by Team 2 further responds to and bolsters TRC Calls to Action 62-65, all of which are related to the ways in which education system reform plays a crucial role in reconciliation and in supporting Indigenous cultural revitalization

Invite all Indigenous leaders and organizations from all provinces and territories to join an Indigenous-led education committee The committee would begin its work with a three-year research and consultation period based on the framework from the TRC consultation process. During this time, committee members would be responsible for collecting feedback and data in their respective communities to build relationships and understand the needs in each region.

A year after the school systems have been successfully launched, the Committee will host annual Indigenous Education Gatherings supported by organizations, philanthropists, and the federal and provincial governments. It would include community leaders, panel discussions that include students and booths highlighting schools, programs, resources, initiatives, etc

Quote from Team 2's Brief

Quote from Team 2's Brief

To be held accountable and able to report their findings, the committee will provide reports to the stakeholders that provided funding. This would be groups such as but not limited to non-governmental organizations, philanthropists, and the federal and provincial governments.

“

We believe that culturally safe environments cultivate and enrich the knowledge and gifts of Indigenous People

Team 3's policy brief focuses on relationality education (which focuses on the responsibilities of being part of a community) as a means to combatting violence, racism, and discrimination against Indigenous people. According to their brief, relationality education includes personal relationships, cultural competence, and relationship to the land The brief points to the importance of comprehensive education spanning everything from consent, to intimate partner violence, to trauma, in reducing racism and discrimination, noting that many in Canada continue to possess little knowledge of First Nations, Métis and Inuit realities. Team 3 argues that approaching the whole of curriculum with relationality education in mind rather than simply setting new standards for curriculum models provides more flexibility for education leaders to make the education impactful to their specific contexts

Team 3 Recommendations:

1. 2. 3

That the Government of Canada consult with First Nations, Inuit and Métis leaders, educators, Elders knowledge keepers, and youth; provincial school boards and educational organizations; and community organizations about Relationality Education. That a formal pan-Canadian Committee with proportional representation from all provinces, territories, and Indigenous homelands be selected from this group for ongoing work related to Relationality Education. That a federal grant/funding program be developed with the guidance of a Relationality Education Committee to provide a fixed and ongoing amount of funds to be used by organizations and individuals for project creation, professional development, and capacity building that supports Relationality Education.

Quote from Team 3's Brief

“

" An essential piece of the work toward eliminating racism, violence, and discrimination involves learning how to be in better relationship with ourselves, others, and the land.

Team 4's brief attributes racism and discrimination against Indigenous people to a lack of expertise and awareness about Indigenous issues at the local, provincial, and federal levels. The brief outlines a national strategy that would empower Indigenous people to share their knowledge and build relationships, and includes building an advisory council, distributing grants and subsidies to participating organizations and educational institutions, and collaborating with public education, public servants, and Immigration and Citizenship Canada.

The brief cites the low completion rate of training sessions about Indigenous peoples among the federal public services, and points to TRC calls to action 24, 27, 28, and 93, which call for enhancing education about Indigenous peoples for medical students, law students, and newcomers to Canada. Team 4 argues that a national strategy to coordinate these calls through the means described above would be cost-effective and assist public servants that interact with Indigenous people the most (such as the RCMP) in making more informed decisions regarding Indigenous people, both in their professional and personal lives.

4 Recommendations:

That the Government of Canada consults with local Indigenous organizations across Canada to put a call out for territorial representatives to form sub-committees of the federal advisory council.

We recommend that the Government of Canada immediately implement the Advisory Council to review, revise, suggest, and update educational resources within public sectors beginning with Immigration Services, Public Service Workers, and Public Education.

We recommend that the Government of Canada allocate funding to the council to resource adequate and appropriate materials and bursaries for educational institutions

We recommend that the Advisory Council redevelop, in collaboration with Immigration Canada, the Immigration Services education requirements for new immigrants to Canada. We recommend the Government of Canada collaborate with the proposed Advisory Council to reevaluate, develop, and update the current Public Service Worker training.

“

" There needs to be a national strategy to empower Indigenous peoples to share knowledge and expertise on Indigenous issues at a local, provincial, and federal level; this effort would prove to be instrumental in providing the best possible world and future for our children seven generations from now.

Responding to the many known harms caused by the child welfare system in Canada, Team 5's brief addresses the jurisdictional gap between Bill C-92 (An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, which came into force in 2019) and the provincial child welfare structures Noting the many ongoing impacts of the child welfare system, Team 5 argues that the legislation falls short by not including a substantive framework for transitioning the systems from the provinces into the hands of Indigenous nations, and lacks the necessary guidance on ensuring communities are capacitated for this change.

The brief argues that their policy recommendations will help more Indigenous children grow up in their communities and connected to their culture and families, which will have positive impacts for generations In particular, the recommendations are focused on fulfilling Article 34 of UNDRIP, which protects Indigenous rights to “promote, develop and maintain their institutional structures and their distinctive customs, spirituality, traditions, procedures, practices and, in the cases where they exist, juridical systems or customs, in accordance with international human rights standards”.

Team 5 Recommendations: 1. 2 3. 4

Community-led consultation: Indigenous communities, stakeholders and partners meet with the provincial government to discuss strategies for supporting the transition from Provincial child welfare to Nation-led child welfare.

Provincial government provides funding for Indigenous communities to launch information gathering initiatives with youth in care to discuss their experiences with provincial child welfare. This information will inform whether the transition is successful.

Develop a comprehensive Action Plan for supporting this transition of jurisdiction including a readily available database of supports, resources, research, capacity building recommendations

Provincial governments use the information gathered through recommendation 1 and 2 to develop a framework for applying supports to Indigenous communities moving forward with implementing their own model for child and family services.

Quote from Team 5's Brief

“

"

Indigenous communities who take control of their child welfare will not only reduce the number of Indigenous children and families negatively impacted by the child welfare system but will also create a system designed to empower future generations and families.

Responding to the many known harms caused by the child welfare system in Canada, Team 5's brief addresses the jurisdictional gap between Bill C-92 (An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, which came into force in 2019) and the provincial child welfare structures Noting the many ongoing impacts of the child welfare system, Team 5 argues that the legislation falls short by not including a substantive framework for transitioning the systems from the provinces into the hands of Indigenous nations, and lacks the necessary guidance on ensuring communities are capacitated for this change.

The brief argues that their policy recommendations will help more Indigenous children grow up in their communities and connected to their culture and families, which will have positive impacts for generations In particular, the recommendations are focused on fulfilling Article 34 of UNDRIP, which protects Indigenous rights to “promote, develop and maintain their institutional structures and their distinctive customs, spirituality, traditions, procedures, practices and, in the cases where they exist, juridical systems or customs, in accordance with international human rights standards”.

Team 5 Recommendations: 1. 2 3. 4

Community-led consultation: Indigenous communities, stakeholders and partners meet with the provincial government to discuss strategies for supporting the transition from Provincial child welfare to Nation-led child welfare.

Provincial government provides funding for Indigenous communities to launch information gathering initiatives with youth in care to discuss their experiences with provincial child welfare. This information will inform whether the transition is successful.

Develop a comprehensive Action Plan for supporting this transition of jurisdiction including a readily available database of supports, resources, research, capacity building recommendations

Provincial governments use the information gathered through recommendation 1 and 2 to develop a framework for applying supports to Indigenous communities moving forward with implementing their own model for child and family services.

Quote from Team 5's Brief

“

"

Indigenous communities who take control of their child welfare will not only reduce the number of Indigenous children and families negatively impacted by the child welfare system but will also create a system designed to empower future generations and families.

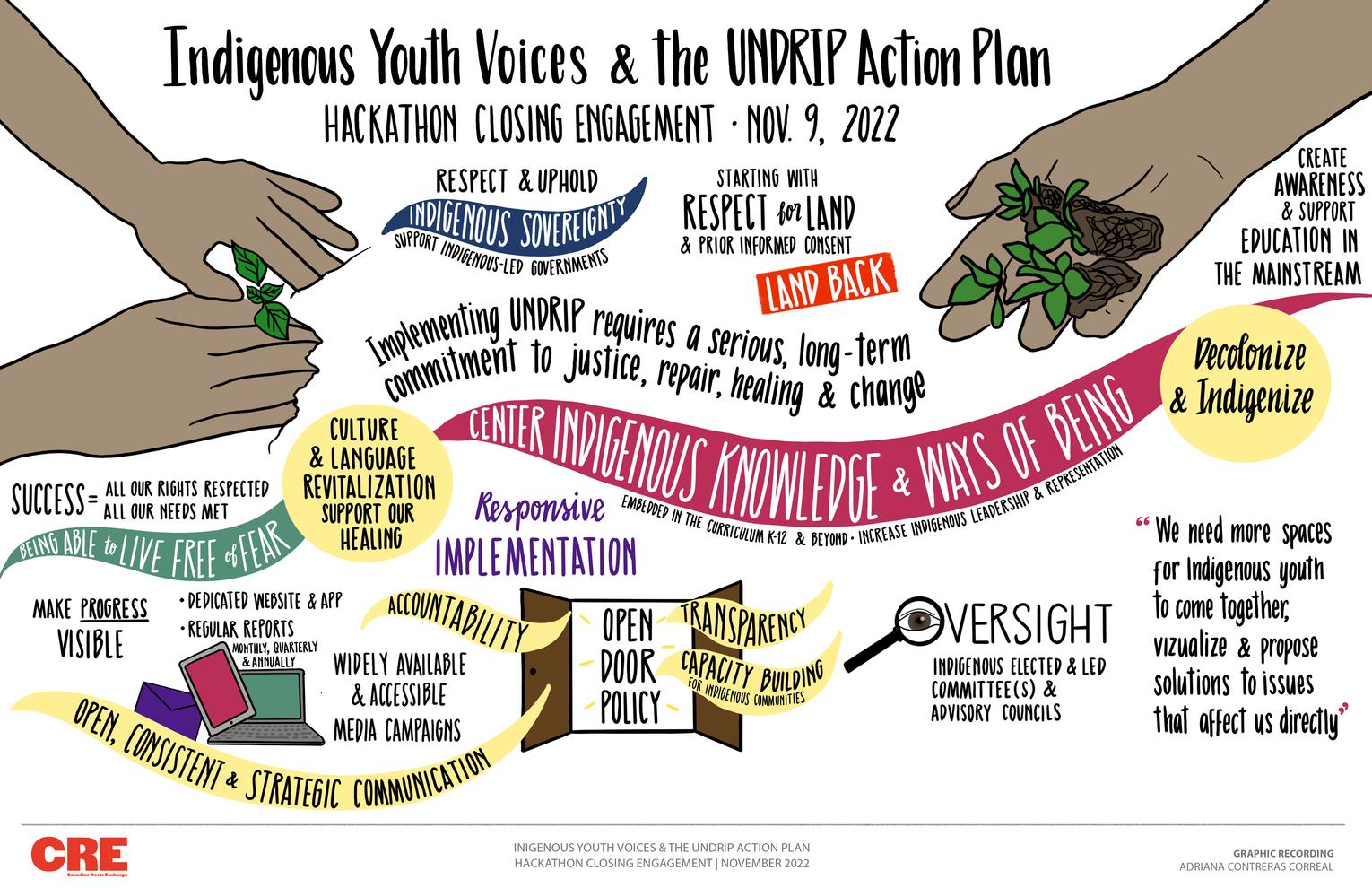

On November 9, 2022, CRE hosted a closing engagement so that the youth could debrief and share their feelings about how the hackathon unfolded, what impacted them the most, and what we can improve on for next time CRE staff also gave space for them to share anything that might not have been included in their briefs, and anything they didn’t have the opportunity to express about the case study during the actual hackathon. The session included graphic recording by Adriana Contreras, which can be found below.

When asked to reiterate what laws and policies were most important to begin with in developing the UNDRIP Action Plan, youth quickly reached a consensus that education for non-Indigenous people would be a key place to start In particular, they recommended that educational curriculum in from Kindergarten to Grade 12 should include courses about the history of colonization and its ongoing impacts. Participants also lauded post-secondary institutions that have made credits in Indigenous history mandatory for graduation, while acknowledging the best approach would be to incorporate Indigenous contexts and realities into broader curriculum Participants also asserted the importance of ensuring these courses are taught by Indigenous people and are founded on Indigenous-produced knowledge Participants also identified that land redistribution, self-governance, and climate change need urgent reform in terms of where UNDRIP implementation should begin.

In discussing how they would measure the success of UNDRIP’s implementation, youth pointed to some broad indicators such as less abuse of power towards Indigenous people, better relationships between the federal government and Indigenous communities, and legislative gaps being addressed (such as those apparent in Bill C-92). More specific indicators identified include:

Fewer deaths in police custody;

Lowering of suicide rates;

Lowering of rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, Two-Spirit, and gender-diverse Indigenous people;

Lowering of rates of violence against Indigenous people; More funding for Indigenous post-secondary students;’

Lowering of rates of homelessness of Indigenous peoples; and Increased availability of affordable and healthy foods

Youth also identified transparency and communication as key to UNDRIP’s success; they expect to see information about UNDRIP’s progress clearly and consistently communicated and expect outreach to their communities about it to be substantive. Finally, they expressed a desire to see enhanced community capacity and empowerment – they want their communities involved with the implementation and their capacity increased. This includes seeing more investment in Indigenous-led governments, land redistribution, and infrastructure projects

During the closing engagement, we also asked youth what they felt was the most impactful thing the Government of Canada could do to eliminate violence, racism, and discrimination against Indigenous peoples. Throughout this discussion, all answers fell into three categories:

Education, including:

Funding anti-racism education for non-Indigenous people, such as cultural competency;

Mandating workplace anti-racism training and training about Indigenous history, and treaty and status rights; and

Support education initiatives that are community-developed and led Land & Rights Recognition, including:

Stable, multi-year funding for Indigenous-developed and led culture and language programs;

Support and affirm Indigenous rights to self-governance and sovereignty (including but not limited to election codes, citizenship, membership);

Support and affirm the TRC Calls to Action across all jurisdictions; Support and affirm treaty rights across all jurisdictions; and Affirm and enforce the principles of Duty to Consult and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

Essential Infrastructure & Services, including:

Ensuring all Indigenous people have access to clean water; Ensuring all Indigenous people have access to housing; Ensuring all Indigenous people have access to affordable, healthy food; Ensuring healthcare is accessible, safe, and free from discrimination; Indigenous-specific anti-racism training for healthcare professionals; and Support for culturally-safe and Indigenous-led addictions treatment such as healing centres.

In speaking to how the Government of Canada should report back about the status of UNDRIP’s implementation and Action Plan, youth expressed that they would like to see updates more biannually or quarterly rather than yearly. Like the sharing circle participants, the youth at the hackathon closing engagement emphasized that updates and milestones should be widely published through a variety of online channels (including social media) and in a variety of mediums and should be written with accessible language and translated into multiple languages Participants also agreed that oversight of UNDRIP’s implementation should fall to an all-Indigenous council that includes elders and political leaders from every region / nation.

Youth voices are crucial to ensuring the design and execution of an Action Plan to implement UNDRIP respond to the lived realities of all Indigenous peoples. Throughout our engagement, youth spoke clearly and directly to their experiences of being disinherited due to blood quantum rules, spoke to the complexities of being afro-Indigenous and/or mixed-nation, and spoke to how government policy has failed to meet their needs because of their heritage. These issues, along with the jurisdictional complexities that further compound them, are not new issues and continue to need urgent action. As the recommendations listed below reveal, addressing discrimination, racism, violence, against Indigenous people in a way that is accountable and measurable, as well as improving relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples requires an innovative, multi-pronged approach. Health care, poverty, mental health, education, criminalization, food, and housing affordability are all inextricably entwined and need to be addressed together.

In particular, we would like to draw Justice Canada’s attention to these three umbrella recommendations, within which many of the more granular recommendations developed by the youth we spoke to are encompassed. Each of these umbrella recommendations should be enacted within the context of pushing towards Indigenous sovereignty and selfdetermination, and should not be understood as a substitute for the rest of the recommendations listed in this report.

1. 2. 3.

Establish regionally-specific funding pots for Indigenous-led initiatives that address food insecurity, housing precarity, and access to all forms of healthcare. Develop a national strategy for Indigenous-specific anti-racism education (including sector specific training requirements, and ensuring Indigenous rights, histories, and realities are incorporated into secondary and postsecondary education curricula) Report back often, in accessible formats, and continue to dialogue with youth through engagement (this includes reporting on at least a quarterly basis, with smaller milestones reported as they develop, as well as cultivating an online presence so that youth have easy access to updates)

In addition to these long-term systemic reforms, symbolic measures – such as working to rename streets and remove statues that commemorate colonizers – could be taken more immediately to and help to begin building trust between Indigenous youth and the Government of Canada In our conversations with youth from coast-to-coast-to-coast, it was clear that while they want the Government of Canada to take UNDRIP implementation and the many rights it stands to elevate seriously, they do not expect that colonial governments are the sole answer to the many colonially rooted barriers they outlined during our conversations. Some youth further articulated the fear that UNDRIP will lose momentum in public discourse and in political will, citing the many TRC Calls to Action and MMIWG Inquiry Calls to Justice that remain untouched

Generally speaking, there is a clear and understandable lack of trust between Indigenous youth and the Government of Canada. Any trust will need to be earned through years of consistent relationshipbuilding, communication, respect, and most importantly concrete action on the priorities that youth have identified here. Many of the youth we spoke to expressed enthusiasm and willingness to continue to be engaged in this process, especially if it means that they continue to build community with other youth For these reasons, we would highlight the importance of continuing engagement with Indigenous youth through advisory councils, more sharing circle, and strongly encourage Justice Canada to cultivate an online presence in order to connect more consistently with youth and their communities about UNDRIP implementation.

The recommendations below have been structured firstly to provide guidance on the following elements of the UNDA:

A. Addressing injustices, combat prejudice and eliminate all forms of violence, racism, and discrimination against Indigenous peoples (including Elders, youth, children, persons with disabilities, women, men, and gender-diverse and Two-Spirit persons);

B. Promoting mutual respect and understanding, as well as good relations, including through human rights education; and

C. Monitoring, overseeing, and evaluating the implementation of UNDRIP.

Due to the breadth and number of recommendations youth shared, we’ve also broken down each section by the law or policy area the recommendation falls under (such as health care, education, self-determination, etc.).

“

"

I’ve studied UNDRIP in university, followed what was happening, especially Romeo Saganash’s work. Being included in conversations like this makes me feel hopeful that my voice and concerns are being met.

Sharing Circle Participant

1

The UNDRIP Action Plan must seek to develop transition plans supporting Indigenous selfdetermination / self-government / sovereignty, including better legal protection for treaty rights for those nations / communities that choose it These plans should be developed on a nation-tonation basis and should include transition plans for replacing the Indian Act and its status system by giving nations control of their own membership, citizenship, and election codes

2

The UNDRIP Action Plan must include developing legislation protecting Indigenous peoples’ rights to practice their culture, including Indigenous workers’ right to take time off for ceremony, and their right to be free of reprisal after receiving traditional tattoos

3