How to Accurately Feed a Forage-Based Diet

By Madeline Boast, MSc. Equine Nutrition

By Madeline Boast, MSc. Equine Nutrition

Most horses are maintained on a forage-based diet, meaning that the primary component of their daily ration is hay or pasture. In the equine nutrition world, the term “forage-first” has gained popularity. This feeding practice provides a multitude of clearlyreported health benefits, such as reduced risk of gastric ulceration and stereotypical behaviours. However, simply allowing your horse to have free choice access to hay or pasture is not enough to ensure optimal nutrition.

Additional nutrients are required, and there are some key considerations that go into accurately feeding a forage-based diet to optimize the horse’s nutritional well-being.

When considering a forage-based diet for your horse, or if your horse is already consuming one, understanding the why is important. Horses are herbivores that have evolved as trickle feeders, meaning their digestive tract is most effective when consuming small amounts of feed frequently. In the wild, horses are freerange on grasslands. This has resulted in horses being adapted to large amounts of high-fibre roughages or forages. When given the choice, a horse will graze for upwards of 18 hours per day.

Anatomy

If we dive into the equine gastrointestinal (GI) anatomy, even starting at

PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK/ ALEXIA KHRUSCHEVA

PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK/ ALEXIA KHRUSCHEVA

the mouth, there are clear anatomical features that support a forage-based diet. Did you know that unlike humans, horses do not salivate in anticipation of a meal? If you know your favourite meal is almost ready, you may salivate in anticipation of consuming it. Not so with horses; their salivation only occurs during chewing.

It is well-known that saliva is important for moistening the feed, but it is also a gastric buffer, which means it plays a role in buffering the acidic environment. Long-stem fibre, such as hay, has a longer chewing time than concentrates and grains. Therefore, when you feed products that require less chew time, saliva

Simply allowing your horse to have free choice access to hay or pasture is not enough to ensure optimal nutrition.

production is decreased, which can result in an increased gastric pH.

Another key anatomical feature is the small size of the horse’s stomach in relation to body size. In fact, it is only about 10 percent of the equine GI tract. This anatomical feature favours continuous movement of feed. Therefore, a horse eating in a similar pattern to a human (three large meals daily) would negatively impact its GI tract, which has anatomically evolved to consume small meals frequently.

In addition to its small size, the equine stomach constantly secretes hydrochloric acid. Since horses are grazers and meant to spend most of their day eating, they have

constant acid production. Therefore, when the stomach is empty and no forage is present, the pH will drop, resulting in a very acidic environment. This can lead to an increased risk of developing gastric ulcers.

The hindgut of the horse (cecum and colon) is the largest portion of the GI tract. Horses are hindgut fermenters, so the health of the hindgut is critical to their well-being. In the hindgut of the horse, there is a diverse population of microbes including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. These microbes require a stable ecosystem and are sensitive to environmental changes, such as a drop in pH.

It has been documented that when a horse is maintained on a forage-based

vs

Therapeutic Conditioning EXERCISES

By Jec A. BallouHow to keep the horse moving by modifying work routines.

When an injury occurs, it is prudent to inactivate the horse for a short period. In less defined scenarios, however, we owe it to our horses to understand that movement itself is therapy, or at least certain types of movement can be. Exercise is not always something that reduces or diminishes a horse’s well-being. More often, it improves overall welfare, and for this reason eliminating exercise must be reserved for only extreme scenarios.

When a horse’s performance and comfort seem to decline from physical causes such as muscle soreness or imbalance, “kissing spine” (overriding dorsal spinous processes), ulcers, stiffness, or reasons that are hard to define, it is logical to change his current exercise plan to allow the body to repair. Change, however, is not the same as elimination. Rather than assuming all movement will worsen any underlying discomfort, the question should be: How to modify the current routine to keep the horse moving daily?

It is worth noting that modification

does not mean just doing a shorter version of the horse’s normal activities. It means finding ways to move the horse’s body without complexity and intensity. For instance, if your dressage horse’s gaits have been irregular but the vet cannot find an injury or explanation, do not cease activity entirely. Nor should you proceed by shortening your daily ride and hoping for the best. Instead of your sameold arena sessions, find exercise that is a lot less taxing and that your horse can perform for approximately 30 minutes.

Generally, it helps to consider the three points outlined in this article. Remember, your goal is to discover what movement your horse can do comfortably while you wait for him to regain 100 percent functionality. Maybe you discover he feels stiff and cranky in the arena when you ride circles and ask for a working trot with rounded topline, but he will meander comfortably down the trail on loose reins. Or you notice that he gets irregular when you sit the trot as normal but travels sound if you post the trot or ride two-point position. Perhaps you

determine the horse can walk beautifully and perform all kinds of manoeuvres, but any gaits faster than that look vaguely lame. Or maybe you decide the horse is only capable of multiple short bouts of stretches and hand-walks throughout the day. The point is to commit to what he can do until you solve the larger issue.

1 Modify the Dominant Gait or Speed

Muscle imbalance, hypertension, and soreness — not to mention faulty muscle activation — can cause a surprising number of gait irregularities. This is especially true for horses that spend most of their working time in a particular gait. Many Western performance disciplines, for example, spend the majority of their

When it’s necessary to avoid weight on the horse’s back, therapy can still be provided through easy, rhythmic movement by groundwork or leading for at least 25 minutes a day in simple straight lines and without restrictive gear.

schooling time each day loping. In several cases when one of these horses begins showing irregularity — tail swishing, poor posture and rhythm, refusal — the trot will remain smooth, comfortable, and willing.

Likewise, many horses eventually diagnosed with “kissing spine” will willingly trot but become grumpy and reactive cantering. It is worth exploring all gaits when there seems to be a problem. When a horse gives a clear indication of discomfort in one gait, it does not mean all gaits should be avoided. If you discover one or two gaits where the horse finds steady rhythm, with or without a rider, embrace those gaits while you work on solving the larger issue. Sometimes, it is only a matter of

If the horse shows discomfort in one gait, keep him moving by finding one or two gaits where he can comfortably maintain a steady rhythm. Slowing the gait may also stop triggering the source of aggravation until the larger issue is resolved.

Old Profession, New Innovations

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJHistorical records show that horseback riders first used cloth saddles in approximately 700 – 400 BC. It wasn’t until about 200 BC, that rigid saddle trees were invented. Since then, Reconstruction of one of the earliest solid-treed saddles, the four-horn Roman military saddle without stirrups, used as early as 200 BC.

When horses went off to war, their tack was customized to prevent saddle sores which could slow down an army. Soldiers riding for long days in all types of weather required differently shaped saddles than cowboys roping cattle, foxhunters jumping hedges, or polo players whacking balls around. Customization has been a big part of the industry, and yet, the basic saddle design — leather and wool sewn to a wooden tree — hasn’t changed much in the last 300 years.

“The basic philosophy of a saddle is fine,” says Christian Lowe, a saddler in Sault Sainte Marie, Ontario who works for Lim Group, one of the largest saddlery companies in the world. “The horse hasn’t changed or evolved so dramatically that something that’s worked for hundreds of years has to be reinvented. But it’s been the nature of the saddlery and harness industries to tinker and evolve.

“Companies that have deep enough pockets for research and development will always be innovating and developing new concepts,” says Lowe. “The reward for getting it right is very high because the horse world is happy to try new products. Companies like CWD, for example, are very technology-driven.” Computerization is one of the big technological changes. In years past, a leather cutter would hand-cut every piece of leather from a hide using a knife.

“Now the cutter identifies where each scar or weak point or flawed material is in a hide, then tells the computer about the bits that they don’t want in the end product,” explains Lowe. “The computer maps it all out and cuts around the flaws to maximize hide use.

“Leather tanning has changed, too,” says Lowe. “It’s way more environmentally friendly now, plus some companies are using non-leather products. Composite plastic and carbon fibre trees are common.”

Today’s market offers colourful leather and non-leather products which provide endless options for customizing saddles and tack. Meanwhile, customized and adjustable trees, changeable gullets, air bags and shims, plus developments in stirrups, stirrup leathers and girths, are ongoing.

But it’s important to remember that

Riders making tough choices

By

By

Canada is a massive country, with large distances between equine competitions and a relatively small number of upper-level equestrians. Hence, Canadian riders who want to be competitive at upper levels struggle to find enough higher-level competitions to advance their riding careers. Canada also has winter weather that precludes many riders from training outside for half the year. This can limit advancement and horse fitness. For example, three-day event riders can’t school cross-country jumps or get their gallop training in when fields are drifted with snow, nor can endurance riders do long rides on varied terrain.

To address these challenges, some riders choose to travel to the United States (US) or overseas to train and compete. Others may move to the US or Europe for all or part of the year. But those decisions have their own challenges. I spoke with three riders who’ve struggled with these choices to understand the Canadian-specific challenges of those wanting to pursue horse sport excellence.

Traveling is Mandatory

Kendal Lehari is a Canadian three-day eventing rider based in Uxbridge, Ontario and considers travelling outside of Canada to train and compete a necessity.

Due to Canada’s long winters, Lehari explains that it’s difficult to get horses fit enough for higher level competition without travelling south of the border.

“If we have winter until mid-April, riders have to go south for at least a little bit to get their upper-level horses fit for spring events,” she says.

“You can stay in Canada to train and compete at two-star level,” says Lehari. “At three-star level it depends on which event you’re aiming for. It’s a little easier to prepare for a fall three-star when based in Canada, but if you’re aiming for a spring three-star you really have to be based in the United States.

“Plus, you can’t qualify for a CCI**** in Canada anymore, so you have to go to the US for that,” says Lehari.

However, even in the US, the number of upper-level competitions is limited. Riders from Canada may have to travel significant distances, such as to Florida or California, to event at high levels.

“It’s pretty difficult for Canadian eventers,” Lehari says.

In August, 2023 Lehari was a member

Crossing Poles IN STRIDE

By Lindsay Grice, Equestrian Canada coach and judgeGround rails, trail pattern poles, or obstacle course logs — these low-lying obstacles are a regular feature in the equestrian experience. We walk, trot, and canter over them in straight paths, serpentines, or pinwheels.

There are more commonalities than differences in pole crossing styles between riding disciplines. I’ll cover the shared essential ingredients for English and Western riders in this article. But first, let’s start with some differences worth noting.

Western riders cross poles set at shorter distances and in quieter striding, working toward patterns of poles in tighter formations. Competitors in trail, ranch trail, ranch riding, and Western riding classes navigate poles at the jog and lope. Precision is prized. There are assigned penalties for hitting poles, even for a slight tick in trail classes. Adding or subtracting a stride between the rails earns penalties, too. In walk-overs, two hooves in the same space or no hooves (skipping) a space costs a one-point deduction.

Moreover, style and consistency are scored. The horse should cross each pole without a change in cadence or topline or even changing his pleasant expression.

English riders use ground rails as a training tool rather than an element in competition. Riding over poles on the ground is an excellent way to work on stride adjustability for the horse and for the rider. Poles can encourage buoyancy in the stride, teaching your horse by trial and error to rebalance and “define” his step. Ground rails can prepare horse and rider to answer the questions asked in jumper and equitation courses without actually jumping.

Regardless of your riding style, the principles and the ingredients are the same in order to take poles in stride.

Pole Crossing Principles

TWO BIG IDEAS

1 Master fundamentals before including poles. Don’t skip training steps. Nothing shakes a horse’s confidence like getting his feet tangled as he leaps over

and lands on the rails. And no wonder — for a prey animal to have trapped feet is big trouble.

A good math teacher communicates the basic concepts, rehearsing adding and subtracting before teaching equations and problem-solving. As a rider, it’s your responsibility not to pose questions with poles your horse isn’t ready to answer.

Trotting over a row of multiple poles is overwhelming to a horse that hasn’t mastered crossing two poles. Misjudge the spacing on the first two poles and by mid-row, his legs are scrambling like Fred Flintstone’s feet as he rushes to the end of the line.

Loping over a pinwheel of four poles starts with consistently rating the stride between two poles and then three on a shallow curve, before tackling the tighter turns between pinwheel spokes. Misjudge the distance to the first pole and it’s tricky to recover your rhythm and carry on without a big move. And big moves scare green horses.

Building your horse’s skill and confidence over poles begins with laying

Remain Calm & Ride On

By Tuning In To Your Internal State

By Annika McGivern, MSc, Sport and Exercise PsychologyAll riders are familiar with the joy and challenge associated with mastering the dance of connection and communication between horse and rider. However, fewer riders are familiar with the role which regulating our nervous system plays in this intricate ballet. We can all picture the ideal of equestrian connection and communication: seamlessly guiding our mount with subtle cues, both attuned to each other’s energy and intention, lightness and ease exuding from every step. We can likely also picture the many obstacles that get in the way of achieving this ideal, such as fear, tension, frustration, and confusion.

Achieving such a level of harmony requires more than just physical skill; it demands that we tune in to what’s happening within us, and how that internal state impacts the horse. In this article, we will look at the fascinating impact of nervous system regulation on horse and rider communication, exploring why mastering this skill is not only beneficial but essential for riders seeking to enhance their bond with their equine partners, manage their own stress and fear, and achieve peak performance.

What is Nervous System Regulation?

Let’s start with understanding the nervous system. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) governs our physiological responses to stress and relaxation. This system has two branches. When we feel safe, the parasympathetic branch directs our thinking and behaviour. When faced with fear or stress the sympathetic branch takes over and triggers the “fight or flight” response, designed to help us survive in the face of a threat.

To self-regulate our nervous system simply means to practice being aware of whether you are in a parasympathetic (regulated) state, or a sympathetic (dysregulated) state, and to intentionally use tools and techniques to maintain, or bring yourself back into, a parasympathetic state when needed. The knowledge of how

to do this and the practical application of these skills is the process of selfregulating the nervous system.

Problems Created by a Dysregulated Nervous System While Riding

Due to the dynamic and risky nature of equestrian sport, riders commonly experience the physical symptoms of an activated fight-or-flight response: tension, increased heart rate, anxiety, feeling frozen, struggling to think clearly or make decisions, and/or shaking. When we get stuck here and are unable to bring ourselves back to calm, our nervous system is dysregulated. A dysregulated nervous system can lead to heightened emotions and a breakdown in communication between horse and rider. Here are some examples of how a dysregulated nervous system can interfere with communication and effectiveness in the saddle.

1 Interpreting what’s happening in an emotional rather than logical way. For example, a rider in fight-or-flight is more likely to assume their horse is intentionally ignoring them and respond with frustration, rather than become curious about why the horse isn’t responding and attempt to problem solve. This can create unnecessary negative experiences while riding.

2 Unclear signals to the horse. A dysregulated nervous system creates tension which muddies the precision of our aides. For example, a rider in fight-orflight may be unintentionally telling the horse to slow down without meaning to. The rider may experience this as resistance from the horse when in fact the issue is coming from the rider.

3 Heightened fear and nerves. A dysregulated nervous system starts to anticipate danger everywhere and can respond disproportionally to what’s happening. For example, a rider in fightor-flight may feel their horse is taking off with them or is out of control, when in fact they still have control, and the horse is not moving as quickly as they think it is.

Benefits of a Regulated Nervous System While Riding

When in our parasympathetic or “calm” nervous system we experience a host of benefits including clearer thinking, better decision-making, enhanced empathy, open-mindedness,

easier access to positive emotions, and even better memory. As a result, a rider who can skilfully regulate their own nervous system and bring themselves back to a parasympathetic state will experience the following benefits:

1 Improved emotional consistency. In other words, you’ll be able to stay in a calmer, more positive and open-minded place emotionally, even during challenging rides.

2 Self-regulation helps you stay in, or come back to, the calm and grounded state of your para-sympathetic nervous system. This means you will be able to transmit cues to your horse with greater awareness, precision, and clarity. You will also have an enhanced ability to read and respond to the horse’s signals accurately and compassionately.

3 Accurately assessing risk. Being able to self-regulate allows us to better assess risk and understand when we are in danger vs experiencing a challenging moment. We are able to think more clearly and apply our knowledge and skills according to what’s happening to us.

The heightened emotions and anxiety of a dysregulated nervous system can create tension leading to frustration and a communication breakdown between rider and horse.

How and When to Regulate Your Nervous System

These tools are useful while riding, but I also encourage you to consider the value of taking a moment to regulate yourself before you enter your horse’s space. This might be before you get out of the car at the barn, or in the barn before you get your horse from her paddock. This small step can help set the tone for your ride and ensure you aren’t starting from a place of fight or flight because of a stressful day.

1 Breathing exercises. A breathing exercise is simply breathing in an intentional and focused manner for a short period of time. Try this simple breathing exercise to get started.

a Breathe in through your nose for a count of four. Let the air come into your lungs slowly and imagine your rib cage expanding forwards and backwards as your lungs fill.

b Hold your breath for a count of two.

c Exhale through pursed lips (like you’re blowing out candles on a cake) for a count of six. Imagine your ribs contracting and pushing the air out. Allow every drop of air to leave your lungs.

d Repeat five to ten times.

PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK/ROLF DANNENBERG

PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK/ROLF DANNENBERG

IS Desensitization HELPFUL?

A closer look at the troubling physiology behind this common practice and how to support curiosity and courage in our horses instead.By Alexa Linton, Equine Sports Therapist

Now that I’m celebrating my 20th year with my mare, Diva, when I look back at our horsemanship journey, I feel guilt and shame over some of my actions. On reflection, many of those actions related to the belief that Diva needed to be “desensitized” to things in the human world, and to the way I went about doing this.

“Desensitization” is defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary as: to make emotionally insensitive or callous; specifically: to extinguish an emotional response (as of fear, anxiety, or guilt) to stimuli that formerly induced it.

I’ve done a lot of inner work and self-forgiveness around what I see now through a more informed lens as hyperstimulating, forceful, and often abusive treatment in the name of making my horse do all the things I wanted. I know that acclimatizing our horses to the human world is important, but there are ways to achieve this goal that prioritize connection and relationship above all. This article describes my shift in perspective and way of training, and I dedicate it to Diva and her infinite patience with this slow-tolearn human.

I consider Diva to be a sensitive

horse, which is not surprising because I’m her person. Since she arrived in my life at age four, she has been worried about new, novel, weird-sounding, and weird-looking things. Whether cars, bicycles, dirt bikes, tractors, leaves, flags or tarps, her instinct is to go away from the stimulus and not engage — and in the case of what she considers very scary things, to flee. Unfortunately for her, I wanted to explore and do lots of stuff, which meant facing those scary things and in addition, I was about as patient as a gnat and expected her to be on my often-rushed schedule.

For a long time, my answer to her sensitivity was what many of us have been taught — desensitization in the form of forcing her to deal with the scary thing or making her “get over it” through whatever means necessary. The means often involved no choice or time for integration on her part. As with many things with horses, I expected her to be on my schedule. I recall spending hours walking her around an excavator or tractor to “desensitize” her, despite how stressed she was and how much she wanted to leave. Or crossing a creek time and time again, even though she wasn’t

PHOTO: ORY PHOTOGRAPHY

PHOTO: ADOBESTOCK/MARK J BARRETT

PHOTO: ORY PHOTOGRAPHY

PHOTO: ADOBESTOCK/MARK J BARRETT

Mounted Exercises to Improve Rider Seat & Effectiveness

By Sandra Verda-Zanatta, Level 3 High Performance Coach

Rider fitness is fundamental to achieving a harmonious partnership with your horse and improving overall performance together. Regardless of the equestrian discipline, physical condition directly influences the rider’s ability to stay balanced in the saddle and communicate effectively with the horse. Core strength, coordination and flexibility are the pivotal components contributing to a secure seat and refined aids. Whether it be the precision of dressage, the agility of jumping, or the endurance required for eventing or trail riding, every equestrian discipline requires varying levels of physical exertion and skill. A tailored fitness program ensures that riders can meet the specific demands of each sport.

Horses are incredibly perceptive animals, capable of sensing even the subtlest shifts in their rider’s weight, posture, and contact. A well-balanced rider provides a dynamically stable platform, allowing the horse to move freely with expression and fluidity. Conversely, an unbalanced rider can create confusion and discomfort for the horse, hindering its ability to use its body with ease and efficiency. The influence of a rider’s posture and position on the horse is critical, directly shaping the communication system. A rider’s posture serves as a language that conveys cues and commands to the horse, dictating direction, speed, and level of engagement. A balanced and aligned posture creates an independent seat and allows for correct leg placement and subtle rein aids, fostering confidence and a sense of security for both horse and rider, while significantly influencing the horse’s movement, steadiness in the contact, and self-carriage. A well-positioned rider encourages the horse to engage its hindquarters, achieve proper collection, and execute manoeuvres with precision.

In order to maintain a correctly aligned, secure body position, engaging the core muscles is paramount. They provide a stable foundation aiding in the absorption of the horse’s movement. The deep abdominal muscles, the transverse abdominis, and pelvic floor work to support the rider’s spine, while the obliques assist in lateral stability. The muscles of the back, particularly the erector spinae, play a crucial role in maintaining an upright posture and allowing subtle communication with the horse through the seat. Leg muscles, such as the adductors and quadriceps, need to be firm and supple to provide effective aids with varying intensity and maintain proper alignment. The rider’s ability to finely tune and coordinate these muscle groups is essential for progressive training and positive performance results.

Mounted exercises offer a variety of benefits for riders, encompassing both physical and skill-related advantages and significantly contributing to rider stability and balance. They can build strength, improve coordination, and teach riders to isolate parts of their body independently, while targeting muscles necessary to maintain correct posture and alignment. As riders practice the exercises in this article, they gain body awareness and learn how to engage their core, the first step of many to developing a solid and centered seat.

Mounted lunge lessons play a crucial role in improving a rider’s position, as they provide an opportunity to focus entirely on their own body alignment and balance, without having to train or control their horse. It enables them to develop a deep, independent

seat, refine their balance, and become more attuned to the subtle nuances of their body’s movements in harmony with the horse. It is important to use safe, reliable, well-trained horses for mounted lunge lessons and the handler/lunger should be experienced and skilled in the safety aspects of correct lunging practices.

The journey of a rider in any discipline transcends technical proficiency; it is a dynamic and ongoing evolution that demands an open mind and holistic approach to training. Beyond mastering specific exercises, I encourage all riders to recognize the interconnectedness of their fitness, posture, communication, and unique bond with their horse, by embracing a training approach that not only enhances their individual skills but encourages a partnership characterized by respect, trust, understanding, and teamwork. It is imperative for riders to view their development as an ongoing process. Just as our equine partners continuously adapt and learn, so too must riders remain committed to refining their skills. The pursuit of excellence in equestrianism is challenging and marked by dedication to continual improvement. So, let every stride be an opportunity for growth, every mounted exercise a chance to build your partnership, and every challenge a stepping stone towards becoming the accomplished rider you strive to be!

EXERCISE 1

Arm press forward — band around waist

• Hold band and press the hands forward towards the horse’s neck just in front of the withers, maintaining upright posture and a seat deep in the saddle — you will feel a slight contraction of your core as you resist;

• Hold for five strides and then relax arms back to neutral position keeping slight tension on the band — repeat 10 times each direction;

• Progress to pressing one hand forward at a time.

The Cowboy Way

SEASONS of CHANGE

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJCowboys are icons of the North American Wild West, and the cowboy culture continues to dominate Canada’s Western provinces.

“There’s something about being out in the hills by yourself with just a horse and a dog for company,” says Mack Burke, a 21-year-old cowboy who works full-time at the Gang Ranch in central British Columbia (BC) west of Williams Lake.

Founded in 1863, the Gang Ranch was purchased in 2022 by Douglas Lake Ranch located south of Kamloops, BC. It remains a throwback to earlier times. With over one million acres of grazing rights that extend west into the gnarly Chilcotin Mountains where bears, cougars, and wolves roam, Gang Ranch cowboys still live and work as their predecessors did over 100 years ago.

“The Gang Ranch has a lot of old school methods,” says Burke. But it’s unusual. Most cowboys live a different existence today.

“Cowboys nowadays have a lot more

options,” says Terry Grant of “Mantracker” fame. He’s a director of Friends of the Bar U Ranch, a society which works with Parks Canada to promote ranching history through education and activities at the Bar U Ranch National Historic Site near Longview, Alberta (AB).

“Back in the 1880s, cowboys moved around a lot,” says Grant. “They owned a horse, a saddle, chaps, a sleeping bag, and would work for one or two years at a ranch, then move on to the next ranch.

“Ninety-eight percent of the job was looking after cattle,” he says. “Moving cattle as they ate the grass down, calving, weaning, checking on them. The wintertime was a lot less work because a lot of the big ranches didn’t [hay] their cows in winter. They had a lot more land for grazing.”

“Herd Quitter,” a 1897 oil painting by C.M. Russell, Montana Historical Society MacKay Collection, Helena, MT.

Formerly a community for working cowboys’ families, with several services including a store, schoolhouse, and post office, the Gang home ranch is still home to the ranch’s cowboys.

PHOTO: ISTOCK/CG BALDAUF

“Herd Quitter,” a 1897 oil painting by C.M. Russell, Montana Historical Society MacKay Collection, Helena, MT.

Formerly a community for working cowboys’ families, with several services including a store, schoolhouse, and post office, the Gang home ranch is still home to the ranch’s cowboys.

PHOTO: ISTOCK/CG BALDAUF

Bucking Horses

Unsung athletes of the rodeo world

Most riders don’t want a horse that bucks. But for bareback and saddle bronc riders competing at rodeos across North America, that’s exactly what they want — horses that buck and buck well for eight seconds.

Not every horse wants to buck or has the necessary athleticism to do it. Just as dressage movement, jumping skill, and cow sense have been selected by breeders, so has the innate ability and desire to buck. Bucking horses

are purpose-bred, registered, and trained to do their job, just like other performance horses. Larger draft crosses are preferred because they have increased longevity, maintain their soundness, are stronger, and can handle the weight of

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJcowboys on their back while maintaining their bucking style. They’re also bought and sold by breeders looking for new bloodlines and are transported to rodeos across North America where they make their living dumping riders and entertaining fans. And, just like other horse sports, bucking horses can make or break the careers of the bronc riders assigned to ride them.

Making Broncs

“I’m one of the smaller producers,” says Austin Siklenka, the 2023 Canadian Bucking Stock Contractor of the Year from Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan. He’s been breeding bucking horses for six years and has about 40 head of stock on his 1,600-acre operation. “We’re going for quality over quantity.”

As every horse breeder knows, developing horses with specific talents is a long game. Not every stallion and mare match-up will produce the expected talent, whether that’s a winning racehorse or a consistent bucking horse. Plus, it takes years to find out whether the match works.

“The horses start at the bottom and work their way up,” says Siklenka. “We take the two- and three-year-olds, and strap on a surcingle that has a small box attached to it called a ‘dummy.’ The box has a remote connection to an electronic device so that after the horse leaves the chute and bucks a few times, the trainer can push a button to release the cinch and bucking strap, and the whole dummy contraption falls off. That way the horse learns to enter the chute, get fitted with a surcingle and bucking (flank) strap, then leave the chute and buck, all without a rider.

“The horses are learning how to handle themselves,” says Siklenka. “They’re thinking and everything’s controlled. It’s like an athlete in training.

“A good bucker is consistent, userfriendly, gets high in the air, and kicks high over their head,” says Siklenka. Since professional riders are trying to make a living riding broncs, they don’t want horses that make quick changes of direction or funky dance moves. Just like other equestrians, bronc riders are looking for consistent horses that they can score well on.

As the two- and three-year-olds train and develop, they’re entered in futurity contests where they’re ridden by the “dummies” and judged for their skill. They aren’t ridden by humans until they’re at least age four.

“When the horses come up through the ranks with the dummy, we watch them and try to determine how good they’re going to be,” says Siklenka. “Sometimes they just keep getting better and better and end up being ridden by the open level riders; sometimes they don’t.”

A typical rodeo might need 30 to 40 head of bucking stock, which is generally supplied by a large stock contractor. Top horses produce top rides, so it behooves

The horse and the contestant are each scored out of 50 points, for a total possible score of 100 points for a qualified ride. Very good scores are in the 80s; exceptional scores are in the 90s.

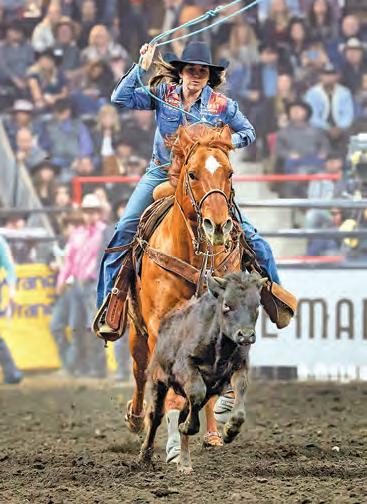

Women’s BREAKAWAY Roping

THE FASTEST SPORT IN RODEO

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJBreakaway roping is the fastest rodeo sport on the planet right now. Winning times are less than two seconds. Yes, you read that right — less than two seconds can garner professional breakaway ropers thousands of dollars in winnings.

And it’s a sport just for women.

“Breakaway roping is a career path for women nowadays, where it was never even considered before,” says Margo Fitzpatrick, the organizer of Canadian Finals Breakaway in Claresholm, AB, which provides the biggest one-day event

payout in Canada of almost $40,000. She’s been organizing local breakaway roping events in Alberta for more than 20 years, but it’s only since 2019 that the sport has taken off.

In 2019, RFD-TV’s The American oneday rodeo event in Texas, United States (US) included breakaway roping for the first time. Nearly 500 women qualified for the inaugural event, chasing a piece of the rodeo’s $2 million in prize money. The winning breakaway rider took home an astonishing $110,000 USD and that single event put breakaway roping on the map.

“Breakaway going mainstream in 2019 changed my life,” says Lakota Bird from Nanton, AB, who was fourth in the average at Canadian Finals Rodeo 49 (CFR) in November, 2023. Now age 27, Bird has been roping since she was 7, and is the breakaway roping director for the Canadian Professional Rodeo Association (CPRA). “I rodeo professionally pretty much full-time. But if it wasn’t for breakaway roping becoming an event at professional rodeos, I probably would have just stopped roping after college. There was nowhere for me to go.”

Here’s how breakaway works: A calf is

held in a chute at one end of the arena. A roper enters the “start box” to the calf’s right. When the roper nods her head, the calf is released and starts running down the arena. Then a rope across the front of the roping box releases, allowing the roper to gallop after, and rope, her calf.

“For most rodeo associations, the bell collar catch is the only legal catch,” says Fitzpatrick. “That means the rope passes over the calf’s head, comes tight on its neck behind the ears, and it can’t include any other parts of his body like a leg or a tail.”

The non-roping end of the lariat is tied to the rider’s saddle horn with a thin string. After the rope is around the calf’s neck, the rider stops her horse, breaking

the string attaching the tail of her rope to the saddle horn. The clock stops when the rope is pulled off the saddle horn, which for winning professionals, is less than two seconds.

“Prior to 2019, breakaway roping was part of high school rodeos but it wasn’t considered an event by amateur or professional rodeo associations,” explains Fitzpatrick. That meant as soon as the high school rodeo gal who was competing in barrel racing, pole bending and breakaway graduated from high school, the only rodeo event she could carry on with was barrel racing. Boys compete in breakaway roping at the junior level, too, but once they reach age 14 to 16, they’re no longer eligible. However, they can

South Algonquin EQUESTRIAN TRAILS

Autumn in Ontario is my favourite time of year, when Mother Nature paints the trees spectacular arrays of reds, yellows, and oranges, and rural roadsides are bordered with the brightly coloured seasonal decor. Algonquin Provincial Park, in Ontario’s southeastern region, is a popular spot to take it all in. Located approximately 250 km north of Toronto and 260 km west of Ottawa, the natural area spans 7,630 km² — larger than Prince Edward Island at approximately 5,684 km². Accessible from the large urban centres of Toronto and Ottawa, every year nearly one million visitors come to hike,

bike, bird watch, canoe, camp, and if lucky spot a deer or a moose.

In 1999, the South Algonquin Equestrian Trails horse facility opened its gates in a newly accessible part of the park’s southern tip, allowing visitors to explore from the saddle the vast array of fresh trails leading to lookouts, lakes, rivers, and waterfalls.

Tammy Donaldson, owner of South Algonquin Trails, saw an opportunity to add horse owners to their visitor roster and built the first equine-friendly campsite on the property in 2018. Thanks to a growing demand they have now expanded to 13 horse-friendly camping areas, one with

By Shawn Hamilton

By Shawn Hamilton

an electrical hookup, and three cabins available for rent. These sites, which are easy to manoeuvre horse trailers in and out of, come equipped with a fire pit, picnic table, and covered stalls, as well as shovel and wheelbarrel. Horse owners can enjoy the trails on their own mounts at their desired pace or hire a guide to show them around. Riders who find themselves horseless can join their friends on one of the facility’s 45 horses, accompanied by a guide. The campsites also provide a comfortable location for participants of the many clinics hosted on the property. From first-time rider to advanced trail enthusiast

One of South Algonquin Equestrian Trails’ 13 equine-friendly campsites in Algonquin Provincial Park.

One of South Algonquin Equestrian Trails’ 13 equine-friendly campsites in Algonquin Provincial Park.