ESS�NTIAL PROTEIN forEquineHealth LAMINITIS

/9YOIIRUOR9E 111R/91'? Don't Judge a Foot by its COLOUR

I/0f<9lKllPINC

GUTHEALTH

ESS�NTIAL PROTEIN forEquineHealth LAMINITIS

/9YOIIRUOR9E 111R/91'? Don't Judge a Foot by its COLOUR

I/0f<9lKllPINC

GUTHEALTH

By Monique Noble

In the world of therapeutic riding, a multitude of heroes make a lasting impact. Selecting just one to honour as a Horse Community Hero is never easy — but in this issue, two remarkable therapy horses stand out: Rupert and Buck. These Norwegian Fjord geldings have been the heart and soul of the North

Fraser Therapeutic Riding Association (NFTRA) for 14 years, beloved by clients and volunteers alike. Although it’s uncertain if they are true brothers, Rupert and Buck have spent their entire lives together, sharing their gentle spirits and unwavering dedication to equine therapy.

Born in 1998, these sweet-natured

horses have dedicated most of their lives to service. They joined NFTRA in 2011 after several years with another organization, quickly becoming integral members of the therapeutic team providing life-changing programs across British Columbia’s Lower Mainland.

Julie Matijiw, NFTRA’s Program

With his gentle temperament and calm presence, Buck soothed many a nervous rider and helped turn challenging therapy into an engaging and rewarding experience.

Manager, shared insights into Buck and Rupert’s lasting influence. Not only have they been pivotal to the program’s success, but they have also become its unofficial mascots, embodying the spirit and mission of the organization.

NFTRA’s roots trace back to the early 1970s, when Tilly Muller and a group of passionate friends recognized the transformative power of equine therapy. What began with two donkeys in Tilly’s backyard blossomed into a cornerstone of hope for individuals of all ages with diverse abilities. Nearly five decades later, NFTRA continues to deliver professional equine-assisted programs to children and adults facing physical, emotional, mental, or social challenges.

Therapeutic riding opens unique pathways of growth often inaccessible through conventional therapies. The rhythmic movement of a horse strengthens underused muscles, improves balance, and enhances core stability. Riding also nurtures emotional resilience, social connection, and selfconfidence, giving participants a profound sense of freedom and

empowerment. Each year, NFTRA serves approximately 200 riders, positively impacting thousands of lives.

Sturdy and steadfast, Rupert and Buck — both standing around 15 hands — have played a role in every aspect of NFTRA’s programs, from groundwork to sidewalking to independent riding. They have carefully guided riders through obstacle courses, games, and patterns, though they were known to occasionally sneak a snack when grass was within reach. Each horse brought a unique gift to the program.

Rupert, naturally curious and playful, excelled with vocal clients and those who reacted quickly or loudly. His calm demeanour helped riders with anxiety, autism, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, or global delays stay focused and confident.

Buck, the quieter of the two, soothed even the most anxious riders. His gentle presence helped clients engage in therapeutic exercises seamlessly, turning challenging therapy into moments of fun and achievement.

This is a gamechanger for their clients, says Matijiw. “Sometimes if they’ve had a bad day, you want to get them out of their

By Madeline Boast, MSc. Equine Nutrition

Protein is important for general well-being, health, and performance of horses. It is a major component of body tissues, second only to water. Aside from the inclusion in tissues, protein is also essential in the formation of enzymes, hormones, and antibodies. The vast use of protein in the body highlights its importance for health.

The building blocks of protein molecules are amino acids. Proteins are differentiated by both the composition of amino acids and the length of the molecule chain. When protein in the equine diet is discussed, most of the time the term “crude protein” is used. For example, when evaluating a feed tag or hay analysis, a percentage of crude protein will be listed.

Using this information to ensure that your horse’s protein requirements are met can be confusing as the nutritional requirement is not for protein, but for essential amino acids. Even when two products have the same crude protein percentage, their essential amino acid content can differ making them of unequal value to the horse. Understanding protein quality and essential amino acids helps owners make informed decisions about optimal protein supplementation and prevent deficiencies in their horse’s diet.

There are 21 amino acids used to make proteins in the horse. They can be classified as essential, conditionallyessential, or non-essential. Essential amino acids cannot be synthesized by the body and must be provided in the diet. Conditionally-essential amino acids can be synthesized, but the horse may be unable to produce enough to meet their body’s demands due to a variety of reasons such as stress, performance, or disease. Nonessential amino acids are not required to be supplied in the diet as they can be synthesized adequately in the body.

Unfortunately, research has not determined exact requirement recommendations for all the 10 essential amino acids; in fact, there is only an established requirement for lysine. Nutritionists currently rely on a recommended intake of crude protein and lysine to determine if protein requirements are being met.

Limiting Amino Acids — Lysine is the most discussed amino acid for horses as it is generally the first to limit protein synthesis. For protein to be made, all the necessary amino acids must be present at the same time. If an amino acid is not present in adequate quantities, it is referred to as the limiting amino acid because it is limiting protein synthesis in the body.

In growing horses, lysine has been found to be the first limiting amino acid. Therefore, when discussing protein requirements, both the lysine and crude protein amounts in the diet are relied on. The other two essential amino acids that you may come across on a feed label are methionine and threonine.

Lysine, methionine, and threonine comprise what is thought to be the first three limiting amino acids in horses. However, most of the time only lysine will be included on a guaranteed analysis.

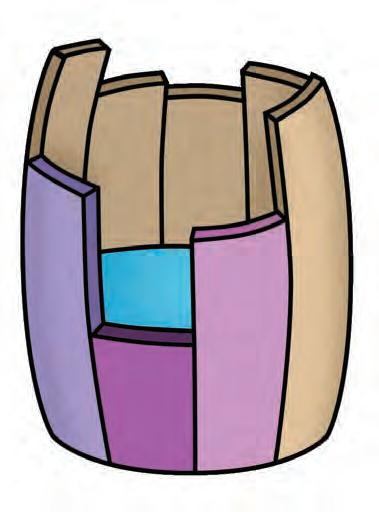

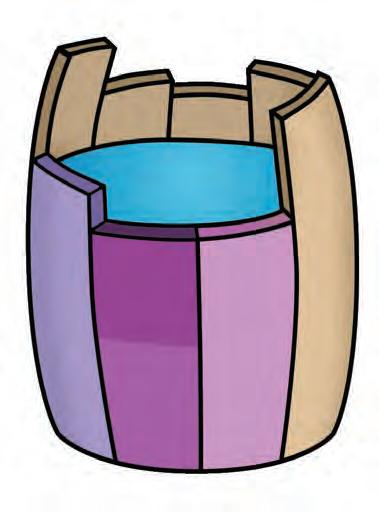

A simple way to picture what this means is with the analogy of a wooden barrel. If the staves (the narrow, curved strips of wood that form the sides of the barrel) are differing heights, then the barrel can only hold as much water as the lowest stave. Once above that level, the barrel will not hold more water, even if the other staves are a greater height (FIGURE 1) To relate this back to protein, when an amino acid is limiting (generally lysine, methionine, or threonine), the horse can only synthesize protein to the rate of the lowest essential amino acid.

Crude Protein — As mentioned, crude protein is listed on hay analyses and feed labels. The term “crude” is used because it is not truly a measure of protein but a measure of nitrogen. The protein’s quality and digestibility are not considered. It would be ideal to use digestible protein as a measurement of protein in feed; however, there is insufficient research to be able to use this measure in horses.

Calculating Requirements — The National Research Council (NRC) 2007 Nutrient Requirements of Horses provides crude protein and lysine requirements in grams based on the horse’s age, weight, and workload. Generally, lysine should account for 4.3 percent of the crude protein content in the diet.

The hay analysis and guaranteed analysis on the feed tag will provide the crude protein value as a percentage; hence, the grams of crude protein supplied must be calculated based on the feeding rate. The following calculations

By Kim Lacey, AWCF

One white foot, buy him.

Two white feet, try him.

Three white feet, be on the sly.

Four white feet, pass him by.

This old saying might make you think twice about purchasing a horse with white hooves — but how much truth does it hold? Given the enduring wisdom of the phrase No foot, no horse, it’s essential to understand the factors that influence hoof health and function, regardless of colour.

Because of the immense forces exerted during weight-bearing, the hoof plays a vital role in a horse’s overall functionality. Over the past 50 million years, the horse (Equus caballus) has undergone a remarkable evolutionary transformation — from the small, multi-toed, dog-sized Eohippus — to the large, powerful, singletoed animal we know today. This drastic shift to a single digit has made the horse one of the most agile and athletic animals on Earth, as well as a valuable domesticated companion that has profoundly shaped human history and culture.

The hoof capsule is the hard, protective outer structure at the end of the horse’s digit. It consists of several key components — the wall, sole, white line, frog, and the

periople (a narrow band of tissue located just below the coronary band) (see Figure 1A and Figure B). Together, these parts form a crucial barrier between the horse’s sensitive inner hoof structures and the external environment.

More than just a shield, the hoof capsule provides essential traction, resists wear from varied terrain, and functions as a natural shock absorber. These roles are effectively carried out only when the outer structures are healthy and work cohesively as a unit. Thanks to its highly viscoelastic properties, the hoof can deform under the horse’s weight and then return to its original shape — absorbing impact and maintaining structural integrity.

However, when the hoof is not functioning properly, distortions such as flares and cracks may develop. This raises an important question: What factors contribute to the development of strong, resilient hooves versus poor, fragile ones?

The shape of a horse’s foot varies immensely and is affected by multiple factors that range from genetics to the environment, but the coffin or pedal bone is the main influence. It is the last bone of the limb and is encased by the hoof capsule, giving the outline to what we see (Figure 2) This bone is developed as a foal and once mature, can only be maintained and supported, but not changed.

The front feet are generally rounder, enabling them to bear about 60 percent of the body weight. The hind feet are pointed to allow for purchase to drive the horse forward and are usually at a slightly steeper angle than the front feet.

The conformation of the horse will affect the angle of the hoof wall, creating different types of feet. The most commonly referenced and seen are ideal,

By Alexa Linton, Equine Sports Therapist

When my newest addition to our small herd, Gwynna — a 40-inch, five-yearold Shetland-Mini cross — arrived last summer, she was overweight, sore, and dehydrated. I quickly discovered that gut health was an issue for her, namely impaction. After our first and thankfully the only emergency call, my vet explained that Miniature horses are prone to impaction colic. Combine this tendency with 30-degree Celsius heat and the stress of a new space, herd, and hay, and she was a prime candidate for problems.

My strategy for her management involved almost no medication and relied mainly on environmental changes. These included introducing a large grass-free track system, fine-tuning her supplementation, allowing 24/7 access to low-sugar tested varied hay in slow-feed nets (one inch and smaller), increasing her water consumption, adding various types of free salt, and promoting lots of movement through varied terrain and herd

enrichment. I am a wee bit obsessed with equine environments — species-specific ones in particular — that mimic how horses live in the wild. I recently started building my fourth horse track system on our new property and just released an online course on Outside the Box Equine about how to create a track system, even in a wet climate, because I love how much movement, choice, and enrichment track systems create. Thankfully, Gwynna has had

no impaction issues for the last eight months, has lost a healthy amount of weight, and is now running freely on gravel with no discomfort.

Many horses are dealing with digestive issues and discomfort daily, whether from ulcers, fecal water syndrome, or impaction, and often their caretaker is unaware. What we might interpret as a behavioural issue, moodiness, or oversensitivity to touch, grooming, saddling, or girthing can be the “canary in the coal mine,” warning us of an unhappy gut. The same can be true for inflammatory issues such as hives, arthritis, hoof issues like thrush, and metabolic disorders. The biggest cause is stress. Let me clarify that not all stress is harmful, but the harmful kind is often caused by factors in the environment, and how your horse with their unique nervous system relates to those factors.

For my pony Gywnna, the main stressors I could discern were lots of change and transition (moving is a big deal!), a challenging past, physical discomfort, loss of function and poor circulation, lack of movement, excess sugars in feeds and grasses, and chronic dehydration. The main pillars of her rehabilitation were:

• Promoting more movement, using her hoof boots as necessary to reduce discomfort;

• Manual, cranial, and visceral therapy to address inflammation, dehydration, and congestion;

• Access to free choice tested and varied hay;

• As much water and fluids as she would consume;

• The right supplementation;

• A balanced herd.

Let’s look more specifically at how the horse’s environment affects their gut health. First, it is important to remember that the equine digestive system is set up very differently from ours, working optimally with small amounts of high-fibre, low-value forage over long periods (17-20 hours) of the day. When a horse is experiencing stress (such as lack of forage), their body chemistry and nervous system shifts. Horses, like humans, have a gut-brain axis, which is a bidirectional communication network between the brain and central nervous system and the enteric nervous system of the gut, involving anatomical, endocrine, and immune pathways, and influenced by the gut microbiome. In a nutshell, the health of the gut is directly influenced by the state of the nervous and endocrine systems, our main barometers for stress. The gut microbiome has gained more and more attention over recent years, and for good reason. It is now understood that the microbiome, the unique makeup of bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites, and other gut flora, has a protective immune function as well as a key role in digestion, and is very impacted by stress-related hormones like cortisol and neurotransmitters like epinephrine. In fact, distress signals sent to the gut by various pathways can cause a heightened inflammatory response throughout the body and have been shown to increase the numbers of pathogenic bacteria leading to gut issues.

When addressing your horse’s environment in the context of supporting digestion, it’s important to think about the microbiome. Here are some common stressors/factors that weaken and disrupt

By Lindsay Grice, Equestrian Canada coach and judge

The equestrian’s quest for the perfect circle crosses all disciplines. For Western and English riders, geometry matters. Horse show judges expect to see circles of uniform size and curves ridden with the horse’s body shaped to follow the arc. In dressage and reining, riders must show a clear distinction between large and small circles. In working equitation, circles around barrels and figure-eights must be symmetrical. In equitation and horsemanship patterns, judges frown on ovalshaped “circles.” In all classes, judges will deduct marks for

circles of inaccurate size and over-arced or counter-flexed body alignment.

Circles become ovals when horses cut in, flattening the shape on one side and drifting out on the other. There’s a perfectly good reason from the horse’s point of view…more on that later. Cutting in or bulging out of circles and curves is a matter beyond appearance — the horse’s body slips out of

alignment, shifts off-balance, and his gaits deteriorate. Here are some steering issues and their effects that I see when coaching riders and from the judge’s booth:

Cutting in — When the horse cuts the arc of a circle or curve, his body is crooked. His shoulder shifts to the inside of the track, commonly called “dropping” his shoulder. In extreme cases, when a horse ducks in abruptly, he can lose balance and fall. When a horse cuts to the inside, his rider instinctively reacts by pulling his head to the outside. Counter-bent, the horse’s gaits lose their flow, as if there’s a kink in the hose. He misses lead changes and makes disorganized transitions. A counter-bent horse jumps awkwardly or hits trot-over poles in a trail course, not only because he’s unbalanced but because he can’t focus on the obstacle with his head tipped to the outside. Cutting in offline, after a jump or trail obstacle, leaves you with less room to mentally and physically prepare for the next fence or obstacle.

Drifting out — It’s the battle of the bulge. A bulging circle can range from disappointing — resulting in losing marks for accuracy on the judge’s scorecard — to disastrous: a horse exits a circle on a tangent; a barrel racer exits a curve into the fence; or a hunter pony exits the gate! If the horse’s haunches fishtail outwards, he’ll swap leads or break gait. When a horse drifts outward, off the line of approach to a trail obstacle or a jump, it disrupts the rhythm and flow of the course, resulting in an awkward take-off distance or “chip.” Horses jump in poor form or even run out, past the fence, due to a crooked approach.

• Balance — An accurately ridden figure is easiest when the horse is laterally balanced — equal weight is distributed on his outside and inside limbs. Longitudinally, when the horse shifts weight from his forehand to his hind end, he’s “lighter.” As the circles become smaller this will be more important. A horse steers, moves, jumps, stops, and makes transitions better when balanced and light.

• Alignment — When the horse has his head, neck, shoulders, and hips in line with his path of travel, he’s straight. So, curved path or straight, no body part should drift off the track.

• Self-carriage (the icing on the cake) — When the horse stays consistent in his alignment, stays on the line of travel, stays in balance, and stays in pace without the rider holding him there — he’s “light.” He’s discovered, by trial and error, the perimeters of the chute between my hand and leg aids. And he finds release, or negative reinforcement, within the chute. In self-carriage, circles and curved figures become a beautiful thing indeed.

In my years of training horses and watching them from the judge’s chair, I’ve come to anticipate the equine tendency to cut in one half of almost every circle and swell out on the other half. Why? That’s my favourite question. Why do horses do what they do? I teach riders to appreciate the instinct driving equine behaviour. With that awareness, riders can anticipate and prevent a host of undesired responses before they happen and prevent faulty figures before they appear on the score sheet. Why horses bulge out — The horse is a herd animal, hardwired to believe there’s safety in numbers. He’s naturally magnetized toward the gate, the barn, or another horse. Left unchecked, the horse’s draw to the herd overrides the outside leg as the rider

This horse is bulging out from the arc of the circle, inattentive to the outside leg and neck rein aids.

attempts to keep him on track. At best, the horse ignores the leg and leaves the circle. At worst, the rider’s outside leg gets sandwiched into the fence or earns a kick from another horse not wishing to play bumper cars in the warm-up ring!

Why horses cut in Horses learn to anticipate anything they’ve learned by repetition. If the rider always transitions to a canter on a circle, a curve after a lead change, or turns to the inside after a jump at the end of a line, it won’t be long before the horse starts anticipating what’s coming and makes turns too early. Riders may unwittingly cue their horses to cut in by dropping their own shoulders in anticipation of the turn, leaning in as a motorcycle rider might lean on a curve. The horse compensates by “following the leaner.”

1. Define your line — If you fail to plan, you plan to fail. Indecision is often at the root of poor geometry; the rider has a general idea of the circle track but leaves the specifics up to the horse. As a novice rider, my instructor coached me to look “ahead.” Not wanting to appear naïve, I didn’t ask what I was wondering: Where exactly is ahead? Mid-air? Between the horse’s ears? Years later while training hundreds of horses and riding thousands more circles, I connected the dots: geometry “happened” when I (a) plotted destination points in the dirt ahead, and (b) decisively directed my horse through those points.

The rider is the decision maker, charting the path for the horse to travel. On circles, pinpoint four dots around the perimeter, like key numbers on a clock face. As you approach one point, lift your eyes to the next, making your decisions well

By Jec A. Ballou

Given the various components of fitness, conditioning plans can vary widely from horse to horse. Some need a program of mostly therapybased exercises to address coordination, postural, or mechanical deficits before moving on to aerobic and gymnastic gains. Others need a restructuring of their workouts and plenty of good hard efforts to push past performance plateaus.

Occasionally, horses fall somewhere in between, which is tricky territory. These athletes need daily corrective exercises to target muscular or postural imbalances, but they are also capable of maintaining a decent level of aerobic activity for general fitness. In other words, there are physical challenges to address with slow methodical

work, but they are not so severe that the horse’s activities need to be sharply restricted. If programs are too easy for too long, the horse stops making gains. If we focus only on therapy-based routines at the expense of gymnastic efforts, these horses end up losing the supplemental benefits of increased fitness to support better movement, resilience, and muscular activity.

Dean, a six-year-old Quarter Horse, was one of these athletes. His owner contacted me for a fitness plan to recondition him following a thorough rehab from a bilateral meniscus tear, which is a common cause of stifle lameness. By this point, Dean was walking and trotting under saddle for a total of 30 minutes following several months of hand-walking.

While he had by no means regained full fitness, Dean had a solid enough base to absorb a decent training load so long as it also contained routines to address the underlying weaknesses that might predispose him to reinjury down the road. In other words, we didn’t want to go full speed ahead on his cardio recovery without examining muscle patterns that contributed to stifle strain in the first place. Watching videos of him moving, I noticed that Dean had a long stride for his height, which resulted in the tendency for his front end to cover a lot of ground while his hind legs trailed out behind. This type of locomotion can strain the hind joints versus flexing and loading them. The fitter and more energetically a

Roll a ball or massage device back and forth across the horse’s glute muscles.

The fitter and more energetically a horse moves in this posture, the more embedded it can become. Before starting the plan, his owner verified that his hoof balance had been closely examined to rule out the possibility of long toes contributing to the hind-end strain.

As I watched this athletic young horse, I realized we needed to help him to move better through his back to reduce concussion down through his limbs. Additionally, I hoped that by correctly activating the deep and locomotive muscles of his back, Dean would begin to draw his hind legs under him rather than trail them behind. This would enable us to strengthen the muscles that support his stifles.

on page 45

This exercise is more of a strength builder than a stretch. It demands the same response from the horse as when a human executes a sit-up. It is incredibly valuable for stretching the horse’s back and lumbar region as well as toning the abdominals. Do not attempt this exercise if your horse is prone to kicking.

1. Stand squarely behind your horse, and make sure he knows you’re there.

2. Tuck the tips of each thumb just under the dock of his tail.

3. Extend your fingers straight up to form a “box” with your thumbs.

4. Apply direct pressure into the horse’s buttocks muscle with the tips of your index fingers.

5. If the horse does not immediately tuck or “squat” his pelvis away from that pressure, try a light tickling or scratching motion.

6. Repeat three times.

Some horses are very sensitive in this area, others less so. You may need to alter your hand position to find your horse’s response.

By Li Robbins

A couple of years ago I bought a socalled “pasture puff,” a seven-year-old mare who’d lived most of her life hanging out with sheep and cows. Seven isn’t that old, but Pippin hadn’t had much handling let alone riding — she’d only been saddled a month or so before I got her. Not surprisingly, when she arrived at her new home, a boarding farm with sixty-some horses, she was anxious. Walking her from field to barn became a game of chicken, as she whirled, veering into me, and at the barn door the drama continued — other horses clopped in and out as she

steadfastly refused to enter.

It wasn’t that we didn’t make any progress. Over time “chicken” was downgraded to mere race-walking, and shoving-the-human-sideways was hinted at more than acted on. Still, for many months Pippin exhibited what trainer Stacy Westfall has deemed “culture shock.” Westfall, in a podcast episode called Retraining Older Horses vs Starting with a Clean Slate, points out that a horse of any age may experience culture shock, but if it’s a younger horse people are more likely to be sympathetic — the “ah, poor baby”

response. With an older horse, challenging behaviours may be less tolerated — the “um, you’re really big” response. When it comes to starting a fully grown horse, people tend to have an unconscious bias, a feeling that the horse “should” know better. Even so, Westfall believes one of the biggest factors affecting training isn’t age, but temperament. She tells a story about three young horses who grew up together and all arrive for training at the same time with “about the same level of nervous.” Despite this, they progress at different rates, something she chalks up

to their individual temperaments. As a result, she suggests that instead of worrying about whether your older horse will be difficult to train, try to put that question out of your mind since it may inadvertently cause you to create behaviours you don’t want. Westfall believes that it’s better to approach the older horse simply with curiosity, framing your training sessions with, “I’m just here to learn about who you are today and what we are dealing with today.”

During my first year with Pippin, the horse she was each day seemed like a revolving door of sweet, spicy, calm, tense, opinionated, accepting — I never knew which horse would show up. Still, I was determined to muddle through, at least until two incidents shook my faith. The first was a flat-out rocket-ship bolt caused by something that seemed minor to me, but terrifying to her. At some point the saddle went sideways — and so did I. The second incident happened not long after, when she began to stumble and lean and lurch. Our vet’s diagnosis: a concussion from an unwitnessed accident in the field. The prognosis: uncertain.

In the days that followed, Pippin was shockingly disoriented, her head tilted to one side and she walked like she’d had one too many. At first, all we could do was hand graze, which gave me plenty of time for mulling instead of muddling. Should she recover — and I had to believe she would — the “holes” in her training somehow needed to be filled. Trainer Mark Rashid writes in his book, Finding the Missed Path: The Art of Restarting Horses, that “Horses are a lot like people in that when there are gaps in understanding (particularly when it comes to the most basic of foundational concepts), confusion, and thus frustration, worry, and even anger are sure to follow.” Prebolt and pre-concussion there had certainly been confusion, frustration, and worry; post-bolt it seemed unlikely I would magically resolve our issues, even with the help of a knowledgeable friend. I had to face it. I wasn’t up to teaching my old(ish) horse new tricks; we needed professional help. So, when she got the all-clear for riding, instead of saddling up we began to work with a trainer. It was fortunate there was a skilled trainer at Pippin’s farm, who knew both of us well. Those in remote locations may not have this luxury — one reason online training programs have become so popular. Regardless, whether choosing an in-person trainer or an online program, it’s

“Horses are a lot like people in that when there are gaps in understanding (particularly when it comes to the most basic of foundational concepts), confusion, and thus frustration, worry, and even anger are sure to follow.” Mark Rashid

important to choose carefully, something that Robyn Schiller, COO of Warwick Schiller’s Attuned Horsemanship, writes about in her blog Along for the Ride She suggests asking yourself some direct questions, a few of which are paraphrased and condensed below:

• How have the horses that the trainer has worked with turned out? Has the trainer proven they “walk the talk?”

• Does the trainer communicate in a way that fits your learning style?

• Given your skill level, is the trainer’s process something you’ll be able to incorporate into working with your horse?

In some ways, choosing a trainer is not unlike choosing a riding teacher. A blog post called How to Choose Your Teacher by Karen Rohlf, host of the Horse Training in Harmony podcast, underscores the importance of looking for someone who best suits your needs, rather than signing up with a specialist in one discipline or

someone known for working with a specific kind of horse. You can find Rohlf’s complete post on her Dressage Naturally blog, but here are a few key points, highly condensed:

• Know what you want to achieve;

• Assess your own skill set dispassionately to clearly understand and communicate what you think you need help with;

• Seek someone who has achieved what you wish you could achieve.

When it comes to the specifics of training older horses, Mark Rashid says that the main difference between starting a young, unschooled horse and restarting an older one with issues, is that the young one is likely to be something of a clean slate. That viewpoint is echoed by Jennifer Williams, founder and president of Bluebonnet Equine Humane Society. In her article Starting the Older Horse she also notes that there’s a “huge difference between an older horse who has never

By Sandra Verda-Zanatta SVZ Dressage & F2R Fit To Ride Pilates for Equestrians

n all sports, communicating and working as a cohesive team takes effort, skill, and patience. This is especially true for equestrian sports, as they require a coordinated effort between human and horse to develop an understanding of each other through physical and verbal cues. This complex communication system relies on the rider’s ability to recognize how their horse responds to body language, weight shifts, and physical cues along with teaching them verbal commands. Through hours of interaction and training, the human-horse dyad can achieve successful athletic performances, harmonious partnerships, and longlasting bonds.

The hips are an essential element in the development of an independent seat, which in turn is crucial for effective communication. From sitting trot to two-point position, sliding stops to reining spins, the rider’s hips play an important role in the execution of movements throughout equestrian sports. Regardless of their competitive discipline or style of riding, equestrians need a balanced seat with strong yet flexible hips to stabilize the pelvis, maintain postural stability, and support a secure leg position that allows for clear, concise aids. A seat that is shock-absorbing and doesn’t rely on the reins, stirrups, or gripping with legs is the foundation for developing a clear

communication system. Relaxed, open hip joints and a mobile pelvis allow the rider’s seat freedom of movement to follow the horse’s rhythm, encouraging the horse to relax and swing, promoting fluidity of the gaits. Tight hips restrict the rider’s ability to follow the horse’s movement and often result in stiffness and bouncing in the saddle, hindering the horse from moving confidently forward in a consistent tempo.

1 Hip Flexors — main functions are posture maintenance and leg position.

• Iliopsoas (iliacus and psoas major): lifts leg and maintains postural stability while mounted

• Rectus femoris (quadricep muscle): hip flexion and stabilization

• Sartorius: leg alignment and positioning

Weak hip flexors impact the rider’s ability to maintain proper posture and leg position, which can cause a loss of balance and the upper body to tip forward. When these muscles are tight, they restrict the movement of the rider’s pelvis and the ability to shock absorb, making it difficult to follow the horse’s movement.

continues on page 59 (exercises are shown pages 56-58)

By Ken Morris, Canadian Horse Heritage and Preservation Society

Roxanne Salinas of Bear Hollow Farm in Lone Butte, BC, has been a tireless advocate and historian of Canada’s National Horse for a quarter century. As we celebrate Canada Day 2025 and all things Canadian, Ms. Salinas gives us a sneak peek into her upcoming book, Canada’s National Horse: A History.

Why are you writing this book?

To give the Canadian Horse back its history. A lot of folks know the Canadian Horse is the National Horse of Canada, but they may not know why it deserves that recognition.

Why does the Canadian Horse deserve to be Canada’s National Horse?

Because he is “all ours,” developed entirely within Canada by and for Canadians. Some might say the Canadian Horse is only a Quebec horse. Of course, Quebec is where the breed originated, and the people of Quebec are justifiably proud of their race patrimoniale (heritage breed). But the Canadian Horse played an important part in the exploration, settlement, and development of the rest of our country, too. In my book I tell the story not only of the Canadian Horse within Quebec and Ontario, but throughout the western provinces.

Tell us about your own history with the Canadian Horse. What inspired you to tell this story?

Around 1976, I saw a photo in a magazine of a Canadian Horse for sale.

Something about that horse must have struck me because I always remembered it. Years later, I saw a black Canadian mare with a big wavy mane at a Morgan horse show. The Morgan folks said she looked “coarse,” but I rather liked her. When my Morgan got old, I tried to find another one like him, but couldn’t. When I saw an ad for Canadian Horses I thought: That’s what I’m looking for!

In the summer of 2000, I visited Swallowfield Farm in Ladysmith, BC, and went into their pasture to see their mares and foals. They were being pastured with their stallion, Eno, who by then was 25 years old. As I recalled years later, “Eno walked out from behind a grove of trees. He held himself so proudly, and he looked right at me with a look that was strong and confident… one of those moments that is forever embedded in memory.”

That fall, I bought his weanling son, Swallowfield Eno Kelbeck and competed with “Kal” for ten years, mostly in dressage. We were showing Second Level and well on our way to Third Level when I sent him to Canadream Farm in Quebec. It almost broke my heart, but MJ Proulx gave Kelbeck the

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

Sam Steele’s Scouts were created in 1885 to help quell the North-West Rebellion –an uprising of Metis and Indigenous Peoples which occurred between what is now Edmonton, Alberta and Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. Sam Steele was selected to lead the Scouts due to his dedication, honesty, and horseback skills, which were honed during some of Canada’s most important historical events.

Born in Ontario in 1848, Samuel Benfield Steele joined the military at age 16 as a competent English-style rider. He supported Canadian Confederation in 1867 and helped quell the 1870 Red River Rebellion in the province of Manitoba. In 1873, Steele was hired by the newlyformed North West Mounted Police (NWMP) to train unruly horses and raw recruits into confident horse-and-rider teams at Fort Garry, near today’s Winnipeg, Manitoba, for the 1874 March West. The creation of a federal police force and subsequent dispersal of NWMP members across the vast Western Canadian prairies was initiated to protect Indigenous Peoples from the ills of whiskey and the land from illegal hunting and American annexation.

Steele earned respect on that infamous ride by helping lead “several of the youngest and weakest men, 55 sick and almost played-out horses recovering from a severe attack of epizootic, 24 wagons, 55 oxcarts with 12 drivers, 62 oxen, 50 cows and 50 calves” for over 1,400 kilometres from Roche Percée in present-day southern Saskatchewan to Edmonton, Alberta. Steele wrote, “The trail was kneedeep in black mud; sloughs crossed it every hundred yards and the wagons had to be unloaded and dragged through them by hand. The poor animals, crazed with thirst and fever, would rush to the ponds to drink, often falling and having to be dragged out with ropes…”

Having thrived during the March West, Steele’s NWMP career continued. He attended the signing of Treaty 6 in 1876, spent time in what became British Columbia, and in 1885 was called up to lead a group of volunteer ranchers, farmers, and frontiersmen to help the military quash the North-West Rebellion.

The rebellion occurred in the rolling hills and swampy lake country located on both sides of what is now the Alberta–Saskatchewan border east of Edmonton and north of Lloydminster. By the time Steele was summoned, nine men had been killed at Frog Lake in northeast Alberta by the Indigenous war chief, Wandering Spirit. Shortly thereafter, a large Cree force surrounded nearby Fort Pitt and took residents hostage.

Discontent had been brewing for years. Once the buffalo were decimated, Indigenous Peoples starved and the federal government limited rations even after signing treaties that promised support. Concurrently, Louis Riel returned from exile in Montana and agreed to lead the Metis in Saskatchewan. The Metis were demanding land title and parliamentary representation, but the federal government didn’t respond to those demands. The Metis and Indigenous struggles coalesced into violence, and Sam Steele’s Scouts were part of the action. Steele’s Scouts, also known as the

By Shawn Hamilton

Nestled in the San Miguel Tecpan region of Mexico lies a quaint ranch, overlooking the State of Mexico Valley, awaiting eager riders to enjoy the tranquility and beauty of the area on amazing horses. Rancho Las Margaritas, approximately 50 km northeast of the Mexico City International Airport, is named after owner Alejandro Villaseñor’s wife and daughter, both named Margarita. Until now, the ranch had only received friends and family members, but Villaseñor and his best friend and business partner, Gustavo Saavedra, have decided to invite outside guests to their exquisite location. Through Unicorn Trails horse riding travel agency, myself and two friends, Ewa and Carrie, were fortunate enough to be the first official public guests in November 2024.

After flying into Mexico City on the “red eye,” we spend the night in the airport hotel and take an Uber the next morning to meet Saavedra at the Holiday Inn in Santa Fe, about an hour away from the ranch. He greets us in his sweet manner and we can tell instantly how excited he is to share their piece of

paradise with us. After winding through various urban villages, two large iron gates open to reveal a stable with 10 box stalls, a small riding arena, and a quaint four-bedroom guest house perched on a hill. Just across the driveway is an additional 22-stall barn, a second riding arena, and a workers’ house with a guest

apartment. The ranch is situated on five hectares bordering Cumbres Sierra Nevada National Park, which offers endless trails throughout the region. During our short four-day visit we will ride to lakes and dams and through old growth forests, lunch beside rivers, and enjoy spectacular views overlooking both the Toluca and Mexican valleys.

Villaseñor grew up on a cattle ranch in La Huasteca, Mexico, where his father raised beef cattle and bred Criollo and Thoroughbred horses. In 1991, Villaseñor began to breed his own line of Quarter Horses and became highly successful, as one can tell from his very full trophy room. For seven years he served as the president of the Association of Quarter Horse Breeders of Mexico and is currently the Vice President of the Mexican Trail Riding Federation. At the age of 76 he is still impressive in the saddle.

On a flight from Guadalajara 45 years ago, Villaseñor flew over the area where the ranch is now located. Liking the look of the untouched land, he explored more

by car to scope it out.

“It was just corn fields back then, but I saw the potential so bought the land,” he explains.

His brother, an architect, helped to design the house and eventually Villaseñor’s dream was complete.

Ewa, Carrie, and I are honoured to be the first-ever outside guests of Rancho Las Margaritas. Upon arrival we’re greeted by Villaseñor and three of his ranch hands, brothers Adrian, Norberto, and Gustavo, whose father also worked for the ranch before passing away.

Small cups called “cantaritos” are gifted to us, and we’re asked to bring them wherever we go in the case a shot of Tequila is necessary (I love this place already!).

A scrumptious charcuterie of guacamole, pico de gallo (a type of salsa), deli meats, chorizo, olives, cheese, and cantarito de barro juice (spiked with a little Tequila if desired), is enjoyed on the front patio looking down at the valley below. After a quick change into our riding clothes, we are given a tour of the trophy