By Monique Noble

The horse community is full of everyday heroes. Sometimes those everyday heroes inspire someone to give back in such an incredible capacity that it creates an exponentially stronger community — one that, at the start, is hard to envision. Little did the horse community in 1970s Ontario know that by embracing a recently immigrated, newly widowed mother of four, they would be inspiring a horse community visionary who would change the face and accessibility of horsemanship throughout the world.

The saying It’s never over for a visionary suggests that a visionary leader’s impact and influence can extend beyond their active involvement in a project or organization. Visionaries are known for their ability to see possibilities that others may not perceive, and this ability can continue to inspire and shape outcomes even after they have moved on. However, while visionaries can have a lasting impact, their success also depends on

their ability to turn vision into reality and build a sustainable framework to carry on their legacy.

Ann Caine has not only overcome seemingly unsurmountable odds; she has given others the chance to do so as well — with grace and self-accomplishment. Caine is not just a visionary; she is also an advocate and fundraiser wrapped up in one very determined and capable person.

It would have been understandable if Caine had moved her young family of five back to Cornwall, England after the loss of her husband less than three years after coming to Canada. However, seeing how their beloved ponies were helping her children cope with their father’s passing, and having the support of the horse community who helped the family navigate their many layers of loss, Caine was determined to make a life for her children and herself in Canada.

“I just saw how these two ponies, how important they were to the children. The children were 14, 12, 9 and 5 when they lost their father. We were grateful for the people in the community who were wonderfully supportive.”

A few years later, Caine — with a vision of giving back to the community and

championed by her daughter Nicola — was inspired. Her experiences with therapeutic riding in England and her children’s ponies made Caine realize that many people in their region of Ontario could benefit from a similar program. Around the same time, Nicola had just returned from England where she earned her certification as a regular riding instructor through the British Horse Society. Upon returning to Canada, she pursued further training and became one of the first three individuals in the country to achieve the Canadian Therapeutic Riding Association’s (CanTRA) Senior Therapeutic Riding Instructor certification (Nicola later advanced to become a CanTRA Coach and Examiner.) Caine chatted with her family doctor about the possibility of opening a therapeutic riding program in their area. With his blessing and support, she and Nicola opened Sunrise Therapeutic Riding (Sunrise) in 1982 in Puslinch, Ontario. With Nicola firmly boots-on-theground with the association as Program Director and Head Instructor, Caine was able to reach for the stars — and her natural ability for fundraising and advocacy began to shine. Nicola fondly remembers her mother’s amazing ability

Ann’s passion for Sunrise Therapeutic Riding and Learning Centre has brightened the lives of hundreds of students, instructors, and volunteers for over 40 years. Sunrise celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2023.

to raise funds without even seeming to try.

“She can basically get money out of a stone. She’ll not like me sharing this…” says Nicola who then told the story of a potential donor who had come from London to see an individual who rode with Sunrise and with whom the donor had a connection. “My mom made red pepper tomato soup and fed him while he was there. And before he left he said: ‘Just wait, I’ve got to write a cheque for you.’ They went out to his car and on the hood of the car, he wrote a cheque for $50,000 and told her, ‘You keep making that soup and I’ll keep writing cheques.’ She just has a way of getting everybody to feel the same passion that she has.”

Caine’s passion is frequently mentioned by people who have known her over the years. While therapeutic riding and the horse community are clearly important to her, in the larger picture inclusivity in all its forms is her true passion.

“Ann is very, very kind and very determined. She’s just so determined to communicate and to share ideas and is fearless in her approach to things,” says JoAnn Franklin Thompson, Caine’s longtime friend and associate who has been part of CanTRA for over 15 years. “She’s just an amazing woman, awe-inspiring, extremely professional, and carries herself that way all the time. And yet she is also warm and fuzzy, so she does not leave anyone feeling left out or unappreciated.

“Ann is the heart and soul of CanTRA. She was there right from the very beginning,” says Thompson. Over the years Caine has been a huge part of CanTRA, playing every role including president, administrator, and just about everything several times even during the more difficult times, explains Thompson. “She is

Blanketing your horse in winter might seem straightforward — just throw on a cover when the temperature drops and you’re done. In reality, it’s a far more nuanced decision. From choosing the right type of blanket to understanding when and how to use it, there’s a balance between keeping your horse comfortable, preventing health issues, and avoiding unnecessary wear or overheating. Add in the swirl of advice from seasoned barn hands, online forums, and long-held myths, and it’s no wonder many horse owners find themselves second-guessing their choices. This guide will cut through the confusion, explore the facts, and help you develop a practical blanketing routine tailored to your horse’s needs and your local climate.

Horses are remarkably adept at regulating their body temperature across a wide range of conditions. According to the National Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Equines, the thermoneutral zone is the temperature

range in which animals can maintain their normal body temperature without expending extra energy. For horses, this range is between 5 and 20 degrees Celsius (41 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit). When temperatures fall outside this range, deciding whether or not to blanket is just one of several important considerations.

Your answers to these true or false questions will test your knowledge of blanketing basics and help you blanket with confidence.

TRUE OR FALSE? If your horse is shivering, he’s already too cold.

TRUE. Shivering is a clear sign your horse is cold and trying to generate warmth. If you see shivering, it’s time to increase warmth immediately, either by moving the horse to shelter, providing hay, blanketing appropriately, or a combination of these actions.

TRUE OR FALSE? All horses need a

By Kathy Smith

blanket once temperatures drop below freezing.

FALSE. Many healthy, unclipped horses with full winter coats and access to shelter can thrive without a blanket, even in freezing conditions. A horse’s coat insulates through its thickness and length, and when kept clean, the hair can fluff up to trap warm air close to the body, reducing or even eliminating the need for added warmth.

However, certain horses may benefit from blanketing, including early-season foals, underweight horses, seniors struggling to maintain weight, horses recovering from illness, clipped horses and those with naturally thin coats.

In addition, horses newly relocated from warmer climates, or those transitioning from life in a stable to living outdoors, need time to acclimate and grow an adequate winter coat. Factors such as age, weight, coat condition, and shelter availability should all be considered when deciding whether to blanket.

TRUE OR FALSE? Clipped horses almost always need blankets in winter.

TRUE. Clipping removes the horse’s natural insulation. Clipped horses often require blankets in cool to cold conditions to prevent chills and support recovery after exercise. Owners who choose to clip their horses are taking on the responsibility of providing blankets to replace lost natural insulation.

TRUE OR FALSE? A higher denier equals a warmer blanket.

FALSE. Denier refers to the strength of a fabric, not its warmth. A higher denier indicates that the blanket’s yarn weave is thicker and more durable. This makes it a better choice for horses prone to destructive behaviour or those that try to remove their blankets. For example, a 1200D blanket is more robust than a 600D one. Warmth is determined by the blanket’s fill weight (e.g., 100g, 200g), not its denier rating.

TRUE OR FALSE? You can layer blankets for more warmth.

TRUE. Layering gives flexibility. Start with a liner or stable blanket, and top with a waterproof turnout sheet or blanket. Just ensure layers fit well and don’t cause rubs or slippage.

TRUE OR FALSE? Horses can’t overheat in winter.

FALSE. Choose the right fill weight for your horse’s blanket by considering his

environment, body condition, and hair coat. The fill weight refers to the amount of insulation in the blanket, measured in grams per square metre (gsm). The higher the number, the greater the warmth. For example, 100g offers light warmth, 200–250g provides medium to heavy warmth, and 400g delivers extra-heavy warmth. Avoid overblanketing, which can cause sweating, dehydration, and discomfort. To check, place your hand under the blanket at the withers or behind the elbow — if the area feels hot or damp, reduce the layers.

TRUE OR FALSE? It’s okay to leave a wet blanket on as long as the horse is warm.

FALSE. Wet blankets lose insulation and can cause chills or skin problems. Always change wet blankets for dry ones or remove them altogether.

TRUE OR FALSE? If the horse is hot and sweaty after winter riding, it’s fine to throw on his heavy winter rug and turn him out.

FALSE. Never place a heavy winter rug on a damp horse. Instead, use a breathable wool or polar fleece cooler to draw moisture away and help your horse cool down gradually without risking a chill. Always ensure the horse is fully dry before turning him out.

TRUE OR FALSE? Fit is just as important as warmth.

TRUE. Poorly fitting blankets can cause shoulder rubs, pressure points, or dangerous slippage. Fit differs among blanket

By Madeline Boast, MSc, PAS

Our knowledge of optimal equine management is continually expanding. The science relied upon to make informed management decisions for our horses is changing as more research becomes available. One of the primary nutrition concerns across North America is the management of horses with metabolic health issues. This article will discuss the goals of nutritional management for these horses, how science has evolved, and updated guidelines based on the newest science for horse owners to follow.

Insulin dysregulation (ID) is a term that encompasses both tissue insulin resistance, and/or resting/postprandial hyperinsulinemia. Postprandial hyperinsulinemia refers to elevated blood insulin after a meal. Horses with elevated blood insulin are at a higher risk of developing endocrinopathic laminitis (EL). EL is the most common form of laminitis.

Within the hoof are laminae called laminae, which hold the coffin bone within the hoof capsule. Inflammation of these

laminae is referred to as laminitis. Not only is this condition extremely painful for the horse, but in severe cases the laminae tissue will separate and the coffin bone will rotate and sink within the hoof capsule; this is referred to as founder.

Across the industry, the prevalence of ID is increasing. It is hypothesized that this could be related to the increase in equine obesity, as horses with ID are often overweight. However, it is important to note that not all obese horses have ID, and lean horses can be diagnosed too.

Horses may also have health issues that

predispose them to the development of ID. Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), also referred to as Cushing’s disease, impacts the hormone production in the horse, and ID is a common symptom of PPID. In these horses, the insulin levels are elevated due to the tissues not responding adequately to insulin. If your horse is diagnosed with PPID, close medical and nutritional management is warranted.

The goal of nutritional management is to maintain a healthy body condition score

while preventing elevated blood insulin.

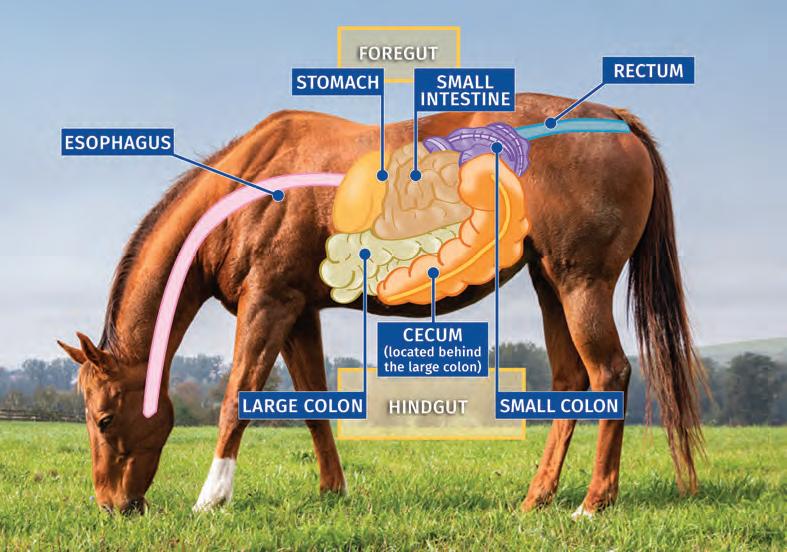

For optimal nutritional management, it is critical to understand how the equine digestive tract works. There are two main sectors — the foregut, and the hindgut. The foregut (stomach and small intestine) is where concentrate feeds are primarily digested and absorbed, whereas forages are primarily digested in the hindgut (cecum and colon).

Most of the enzymatic digestion for the horse occurs in the small intestine. This is where non-structural carbohydrates (NSCs) will be broken down and absorbed along with other nutrients such as protein and fats. The foregut of the horse is the only part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that elicits a postprandial insulinemic response1

When a healthy horse consumes a meal that contains NSCs, this results in enzymatic breakdown and glucose being absorbed into the bloodstream. When glucose enters the bloodstream, the pancreas will release insulin in response to the elevated blood glucose. Insulin is the hormone that stimulates the cells to uptake the glucose so the horse is able to use it for energy.

When the insulin facilitates the uptake of glucose by the cells, the glucose content

in the blood stream will then decrease. As the level of glucose decreases, the pancreas will reduce insulin secretion and all levels return to baseline.

However, in metabolic horses, the cells do not react properly to insulin, which results in an inadequate uptake of glucose from the cells. This means the blood glucose content remains elevated, which triggers the pancreas to continue secreting insulin. As insulin continues to be secreted, the level in the blood rises, which is referred to as hyperinsulinemia. For the health of horses with ID, it is critical to avoid large insulin spikes to, in turn, prevent hyperinsulinemia.

The fibrous feedstuffs, rich in structural carbohydrates, will pass through the small intestine with minimal digestion as they require fermentation. The fermentation takes place in the hindgut and results in the production of volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which serve as a major source of energy for the horse. This process does not result in the same blood insulin spike that can occur with the digestion and absorption of NSCs.

As the horse’s GI tract is designed to process forages, it is recommended to focus on that being the base of the program when formulating an equine diet.

When searching the internet for guidelines to optimally support a horse with ID, the recommendations vary

Like humans, horses are living longer than ever. Typically, older horses will live into their twenties and often into their thirties.

It’s natural to worry about your horse’s health into the golden years. Studies report that 70 percent of horses aged 20 years or older have some type of health issue requiring modifications in management practices and veterinary care. Let’s examine the six key issues your older horse might face, and tips to help you keep your horse feeling comfortable during those senior years.

the horse ages. Horses wear down their teeth as they chew but that wear is often uneven. The development of sharp points in the mouth is more frequent in the elderly equine and this can result in ulcerations, reluctance to chew their food, poor digestion, and a higher incidence of choke.

Severely uneven wear can lead to a condition called “wave mouth,” an uneven biting surface of the molars, where upper and lower teeth don’t align evenly. Missing or loose teeth causing uneven wear to the grinding surface can lead to “step mouth,” which requires regular inspection and care as food can get packed in and cause dental disease, abscess, or infection. In very elderly horses, the teeth may lose their rough edges and become entirely smooth, referred to as “smooth mouth,” which results in an inability to grind food.

Table compares the life stages of humans and horses. A senior horse at around 20 years old is comparable in age to a 60-year-old human. A horse at the extreme old-age of 30-plus years is comparable a human at 85.5 to 100 years of age.

One of the most common health issues of senior horses is dental disease. Extra diligence needs to be paid to the health of teeth in the senior horse. Horses’ front teeth continually erupt at an angle that increases as they age. Cases of unbalanced chewing surfaces escalate as

Maintaining good dental health into old age is one of the single best ways to encourage longevity. It is far more difficult to address and fix a chronic dental issue once the horse has reached an older age.

• If you notice your horse is no longer chewing in a regular circular pattern, this can be an indicator of sharp points and uneven wear and warrants a vet appointment for dental care.

• Horses with smooth mouth should be fed highly digestible feeds that are easy to eat, such as soaked hay cubes or beet pulp; your veterinarian or equine nutritionist will be able to recommend the best course of management.

By Will Clinging, CJF, AJFC

“The farrier crippled that horse.”

Over the past few months, I have heard this from at least two people complaining on behalf of a friend whose horse had gone lame. The farrier was implicated in both cases, and I was asked to consult on one of them. I am going to talk about several issues we farriers deal with all the time, and why it is highly unlikely that the farrier was responsible for the lameness.

These two stories describe the circumstances surrounding complaints in which a horse’s lameness was attributed to the farrier.

The first story concerns a horse that became severely lame, prompting the owner to call on several different farriers for help. While I don’t have details about the cause of the lameness, this situation strikes me as an example of a difficult client rather than a farrier issue. It seems there was little or no communication with the attending farrier, nor was the farrier given an opportunity to address the problem. The owner likely provided no diagnostic information and instead

moved from one farrier to another until the horse eventually improved.

It’s extremely challenging to solve a problem when you don’t know what the problem is — or even that one exists. In such cases, blame often falls unfairly on the farrier, who may be doing their best with very limited information.

Farriers build their businesses around their clients, and good clients are not easy to come by. Unfortunately, many horse owners don’t recognize when they are being poor clients. Issues such as poor communication, refusal to involve a veterinarian for a proper diagnosis, failure to keep horses on a consistent trimming/shoeing schedule, or maintaining substandard stabling conditions all contribute to this. These

Veterinarian, farrier, and owner collaborating on a lameness issue.

factors make the farrier’s job unnecessarily difficult and compromise the horse’s care.

In the second story, a client asked me to examine one of their horses — although another farrier had been providing its care. The client had been told by a fellow boarder that the farrier had trimmed the horse too short and crippled it.

Upon inspection, I found no evidence of over-trimming. Instead, the horse was suffering from a solar fungal infection that had weakened the sole of the already flat-footed, thin-soled horse. In this case, genetics and environmental conditions — not the farrier’s work — were the cause of the problem.

This situation is a good example of the Dunning-Kruger effect, defined as when individuals with limited knowledge or skill in a particular area believe they are far more capable than they actually are. Unfortunately, such misunderstandings can be extremely damaging to a farrier’s reputation. The horse industry is relatively small, and reputation is critical to sustaining a business. Unfounded accusations can unfairly tarnish the standing of skilled professionals doing their best for the horses in their care.

These are just two examples of how farriers often end up being unfairly blamed. Farriers receive input from many different sources — the trainer, the lessee, the owner, barn staff, even the spouse of

By Sandra Verda-Zanatta SVZ Dressage &

F2R Fit To Ride Pilates for Equestrians

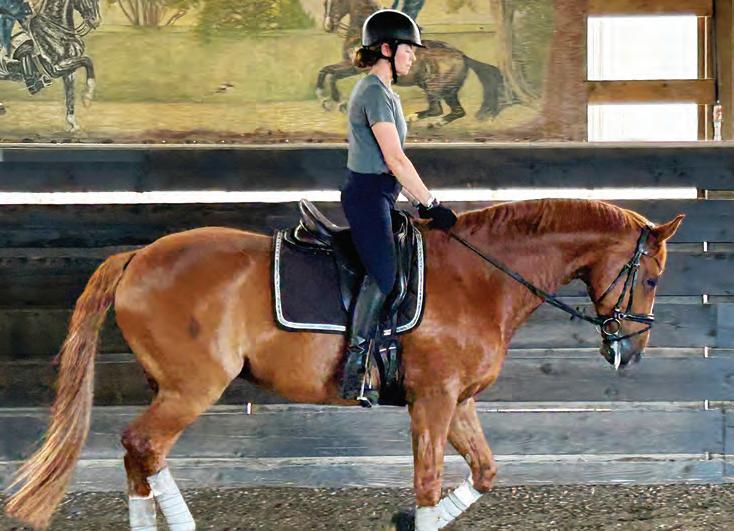

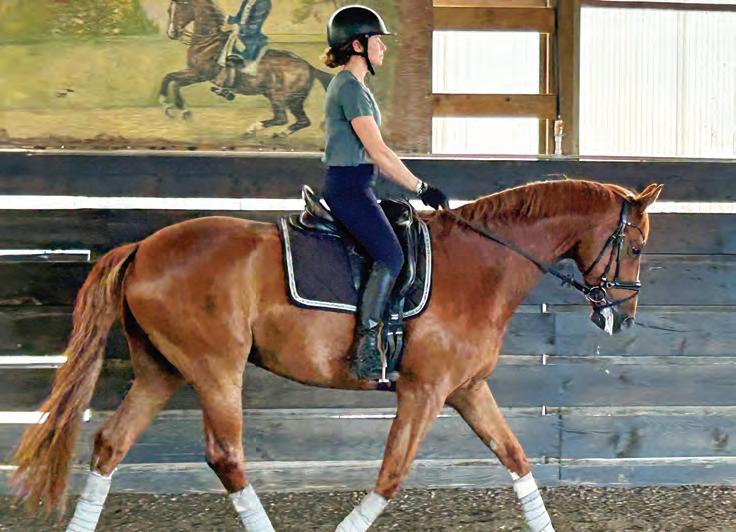

An equestrian athlete’s postural alignment is crucial for balance and effective communication with the horse. A rider’s dynamic posture is constantly changing with the horse’s movement. It should consist of a tall, neutral spine, shoulders down and back, a deep seat, and legs that hang against the horse’s sides with engagement and without gripping. While static, if you drop a plumb line, correct posture vertically aligns the ear, shoulder, hip, and heel, and allows the rider’s body to balance in motion (see Figure 1).

By Alexa Linton, Equine Sports Therapist

Mud season can be a real challenge for horse owners. Managing water and footing is essential to prevent the area from turning into a soupy mess. This past spring, we moved onto our own fiveacre property, and are preparing for our first fall and winter with our herd of four on a track system. It takes creative solutions to keep horses high, dry, and out of the muck, at least most of the time. No matter where you live in Canada, these ideas will help you manage the muddy seasons in your area.

Now let’s get into the nitty-gritty. The amount of mud on your property depends on the time of year; the amount of rain or snow; where you live; the number of horses you have; the amount and type of land you have (forested, pasture, bog); the microclimates and terrain changes on the land (hills, low spots); and the health and make-up of the soil (clay vs gravel). There are countless unique ecosystems depending on where you live, and if we want to preserve or support the land our horses live on, there are some important

By Jacqueline Louie

Halifax Lancers and The Horses of Halifax have been serving Nova Scotia’s Halifax community for nearly 90 years. They teach riders of all ages not only horsemanship skills, but also discipline, teamwork, and leadership capacity. They help people with disabilities learn to ride, grow stronger, and enhance their health. At Halifax Lancers, riding is not about who is the fastest or best performer; it’s about building a stronger community.

For 38-year-old Megan Pegg, joining the Halifax Lancers has been lifechanging. Born with cerebral palsy, Pegg began riding as a very young child. Riding enhances her quality of life in a major way and has given her more freedom.

“It’s opened up so many doors. The horses helped me build my strength and control to walk independently as a small child; they help me live my life to the fullest as an adult,” she says. “The therapeutic riding program gives people a

Taking photos of horses is easy right? Just point your camera at the horse and snap away. You will indeed have photos of horses, but will you want to post, share, or hang them on the wall? The following guidelines will help improve your equine photography with any type of camera, including your phone.

Have you ever looked at your photos and thought: If only I had washed off that manure stain, brushed his mane and tail, and had the farrier out before taking these photos?

Take the time to bathe the horse, allowing ample time for his coat to dry. Brush the body, mane, tail, and forelock.

Find an area with a simple background and place the horse a good distance in front to make the horse the main subject.

Clean the eyes and nostrils with a cloth and keep it handy during the shoot. If you apply fly spray, do it sparingly to avoid wet, shiny spots that will reflect the light.

Tack should be clean, in good shape, and well-fitted, with all straps buckled up and loose ends tucked in. Avoid chains over the horse’s nose and lead ropes with large clips. Hanging the lead rope lower than the horse’s head will make it easier to remove in editing. If you are using a bridle, it is more pleasing to have the reins over the horse’s head and even, as uneven dangling reins can be a distraction.

For portrait and conformation shots, have one or two assistants on hand to make the job easier — one to handle the horse, and the other to get the horse to

look alert with ears forward. Shaking feed in a bucket, waving a small plastic bag on the end of a lunge whip, shaking leaves on a branch, or throwing a hat or cloth in the air should get the horse’s attention. If you have a whinny ringtone on your phone, use the longer version. Set yourself and your camera up in advance of using these tools as many horses quickly grow bored of them.

Avoid busy backgrounds that distract from the subject. Choose a simple location with just a few elements. Position the horse at a distance in front of the background so the horse is the main focus of the image. For black backgrounds, stand the horse in the

lit area of a doorway opening to the barn or arena, and turn off all visible lights inside.

Look for consistent lighting. Avoid shadows on the horse’s face and body. Often, the horse turning his head will cause a shadow on his neck. Position yourself and the subject in even light, either full sunlight or shade such as under a tree, but watch for shadows of leaves.

To adjust exposure on phone cameras, look for the sun icon next to the focus box — drag your finger up on that line to brighten the image, or down to darken it. On other cameras, adjust the exposure by using the plus/minus compensation dial (+/-), which instructs your camera to lighten or darken the image at the settings you have chosen.

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

About 1,500 horses run free on the eastern slopes of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains north of Highway 1, which bisects Calgary, and south of Highway 16, which splits Edmonton. Their presence is controversial. Advocates believe they’re part of the natural ecosystem — just like wildlife — and have historical significance. Indigenous Peoples deeply value the horses and consider them culturally important. A burgeoning number of photographers, artists, and tourists travel to see the horses and record their wonder. Ranchers believe the horses damage range slated for cattle, and occasionally bachelor stallions break their fences. The Government of Alberta considers the horses feral — an invasive species — and has developed a management framework that includes culling or contraception for population control. The science is slim; what’s available is sometimes ignored. Determining the truth is like searching for that proverbial needle in a 500 kilogram round bale of hay.

The Government of Alberta (GOA) states that the horses “are descendants of escaped or intentionally released domestic horses, used by First Nations, farmers, ranchers, logging and mining industries, and hunters before and after the Industrial Revolution.”

Dr. Claudia Notzke, Professor Emirata at the University of Lethbridge, says that a precursor to the modern-day horse (the Equidae family) originated in North America about 60 million years ago. They evolved and spread throughout the world, ultimately going extinct in North America during the last ice age which ended roughly 12,000 years ago. Recent

data indicates that the Yukon Horse went extinct only about 5,000 years ago — a blink of an eye in the timescale.

“About 500 years ago, things came full circle when Christopher Columbus introduced the Spanish horse to modern-day Mexico in 1519,” says Notzke on The Wildie West podcast. The horses then moved north through Indigenous trade and European colonization. This history matches research by Paul Boyce at the University of Saskatchewan, that determined horses came to the foothills of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains in the 1720s with European colonization.