application of Urban Horticulture in

practice

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore and interpret China's architectural Feng Shui theory from the perspective of environmental psychology, and then conduct practical design based on the concept of sustainable architecture and urban horticulture. The article first explores the concepts of Feng Shui theory, environmental psychology, urban horticulture, and sustainable architecture. Then it conducts case studies on the Palace Museum in Beijing, the HSBC Building in Hong Kong, the Apple Store in London, and the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong. Extract the principles and methods of Feng Shui theory application and practice from these cases, and explain them from the perspective of environmental psychology. Finally, summarize and apply these principles and methods to the renovation of the Bini Art and Knowledge House, as well as the design of a Chinesestyle garden at Kew Gardens in London, integrating Feng Shui theory, environmental psychology, urban horticulture, and sustainable architecture concepts for practical design.

Key words: Feng Shui; environmental psychology; urban horticulture; sustainable

1. Introduction

Feng Shui has a very long history in China, the emperors, nobles, and common people attach great importance to Feng Shui in their lives. Emperors and nobles strictly followed the Feng Shui theory in their lifetime from the construction of palaces and noble residences to the tombs after death. The common people also strictly followed the Feng Shui theory in their home construction, spatial layout, and surrounding environment. Feng Shui is the Chinese philosophy of life and allows them to live within the laws of nature. They believe that following the Feng Shui theory is helpful for family harmony, career prosperity, good official luck, and national peace and security. Feng Shui is a philosophy that embodies environmental science and cosmic laws. Feng is the wind which refers to vitality and energy, while Shui is water which refers to flow and change.

The study of Feng Shui in Western countries began in the late 19th century. Feng Shui theory faced resistance and opposition from scholars in various countries because it contradicted scientific concepts at that time and lacked scientific explanations and verification methods Afterward, Joseph Needham researched the Feng Shui theory. In his book "Science and Civilisation in China," he referred to Chinese Feng Shui theory as a "pseudo-science" and "landscape architecture of ancient China". He does not believe that Feng Shui theory is scientific, but he believes that Feng Shui theory contains aesthetic elements (Needham and Ling, 1956). Needham believed the Chinese would struggle to accept the mechanical worldview underlying the European scientific revolution. Over time, Joseph Needham's views on Feng Shui philosophy have been challenged. Feng Shui has existed and developed in non-scientific environments for centuries, and it is the default worldview in China and Southeast Asia (Matthews, 2019), and naturally has its significance and rationality. For over half a century since Joseph Needham, not only Chinese and Southeast Asian scholars but also Western scholars have begun to study Feng Shui theory from a scientific perspective.

At present, architects have adopted Feng Shui theory in architecture and interior design (Cho, 2024). Designers use Feng Shui theory in home design and overall life to create balanced and flowing spaces, using arranged pieces in living spaces to maintain balance with the natural world and establish harmony between individuals and the environment They use clear and clean windows to allow more sunlight to enter the interior, making the space appear more spacious, vibrant, and energetic. Sunlight can also vividly render all the colors and objects that residents see. Then designers plant green plants and fill the room with the life energy brought by plants. Green and vibrant plants are one of the key elements in home feng shui (Cho & Khare, 2024).

Modern neuroscience's development has provided new insights into how architecture affects human psychology and behaviour (Robinson & Pallasmaa, 2015). In the process of

continuous development, humans constantly explore, understand, and reflect on the environment, and then this knowledge forms the theory of environmental psychology. Psychologists divide the processing and evaluation of environmental perception information by humans into the domain of environmental cognitive level, and the adaptive response to environmental cognitive information into the domain of emotional level. Humans will respond to the built environment cognitively and emotionally. (Higuera-Trujillo et al. 2021) According to research in environmental psychology, environmental noise causes human stress (Glass & Singer, 1972), and stress related to the built environment can even damage life expectancy (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). There is evidence to suggest that green coverage near home can alleviate the adverse effects of perceived stress on sleep quality (Yang et al. 2020).

By chance, I touch on the concept of "Lu Chong (Road Conflict)" in Feng Shui. "Lu Chong" refers to the direct frontal or sloping direction of a road towards the main entrance of a building (as shown in Figures 1a and b), which is said to direct strong destructive energy onto the building, affecting the comfort and mental health of residents The solution in Feng Shui is to place a "Shi Gandang (large stone)" between buildings and roads. If the buffer zone is large enough, green vegetation can be planted around the "Shi Gandang" or a small pool can be built behind it. In the pool, the fish can be raised and some aquatic plants can be placed.

These concepts and methods have sparked my thinking. When a building faces a "Lu Chong", people living in the building will feel pressure, which comes from the noise of vehicles driving, the panic and anxiety caused by residents seeing cars rushing towards them, and a deep sense of insecurity, worrying about whether vehicles will lose control and crash into the building. In the solution of Feng Shui theory, the "Shi Gandang" forms a safety buffer barrier between buildings and vehicles driving on the road, giving residents a sense of security. At least the "Shi Gandang (large stone)" blocks the out-of-control vehicles first, and then blocks the residents' line of sight such that residents will not directly look at vehicles coming towards them on the road, reducing anxiety. The small pool forms a second layer of safety barrier, even if an out-of-control vehicle rushes over the "Shi Gandang", it

Figures 1(a) The direct frontal "Lu Chong" (b) The sloping direction "Lu Chong"

will still get stuck in the small pool. Green vegetation around "Shi Gandang" and aquatic plants in small pools can soothe residents' moods and reduce stress. At the same time, green vegetation can help drivers restore their tired vision and clearly distinguish roads and buildings based on green vegetation. These seem to be explained by the environmental psychology of architecture. Therefore, these concepts and methods gave me the idea of using environmental psychology to think and explain Feng Shui.

The "Shi Gandang" to solve the problem of "Lu Chong" is a big stone, which can be replaced by a stone or a wall that has been demolished by other buildings. The construction of small pool should also use sustainable building materials, and green vegetation should be able to plant green vegetables or fruit trees. I believe that the concept of feng shui can be combined with the concept of sustainable building materials and urban gardens (urban farms) to achieve this. Therefore, this project will attempt to interpret China's architectural Feng Shui theory from the perspective of environmental psychology and conduct practical design based on the concept of sustainable architecture.

2. Literature Review

2.1 The philosophical foundation of the formation of Chinese Feng Shui theory

Feng Shui in China is an applied discipline that has gradually developed under the background of traditional Chinese philosophy. To truly understand Feng Shui, one must understand what problems Feng Shui is meant to solve and what the ultimate goal is. Only then can we understand the ideological origins of Feng Shui and the philosophical basis of solving methods.

2.1.1 The philosophical origin of Feng Shui: Tao, Yi, and Chi (Dao, Yi, and Qi)

In Chinese philosophy, "Tao" is regarded as truth. Chapter 25 of the “ Tao Te Ching ” , written by the ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi, mentions that "There was something undefined and complete, coming into existence before everything (contain heaven and earth). Void and vast, independent and changeless, moving in cycle. It may be regarded as the mother of everything. I do not know its name, and I give it the designation of the Tao (the Way or Course) or perfunctorily style it the great". That is to say, "Tao" is a rule that existed before the creation of everything and is the truth of the world (Mair, 1990).

In Chinese philosophy, it is believed that "Tao" is the entire real world that transcends the perceptible experiential world and the imperceptible transcendent world. The "Tao" is popular between everything, gathering into form and dispersing into Chi. Form is the surface, and "Chi" is the interior. The "Tao" is manifested through form and returns through "Chi". Form and "Chi" construct the entire world of experience and transcendence together - the "Tao"

"Yi "comes from the "I Ching (or Yi Jing) (Book of Changes)", which is the oldest, most profound, and famous classic in China. It is the crystallization of wisdom and culture and is known as the "head of the group of classics and the source of the great Tao" (Wilhelm, 2010). "Yi" is a way to understand the surroundings and guide our behavior through a symbol system of divination and prediction, and further to perceive the world and understand the "Tao" (Yijing, 2019). Every object or phenomenon has a "Tao" hidden within it, which is not only the essence of the object or phenomenon but also includes its future evolution and the laws of its change. Because the "Tao" is indescribable and difficult to understand and recognize, we can only use "Yi" to predict and perceive objects or phenomena, and further understand the world and the "Tao" through "Yi".

"Chi" is the vital life force or energy that enables objects or phenomena to exist, operate, and even change (Lu, 1998). Organisms balance their body, mind, and surrounding environment by understanding and mastering "Chi", and recognizing objects or phenomena through "Yi" to approach the "Tao" and achieve the highest level of Chinese philosophy, "unity of heaven and humanity" (He, 2022).

2.1.2 The philosophical foundation of Feng Shui theory (1) Yin-Yang

In the "I Ching (or Yi Jing) (Book of Changes)", it is recorded that "Tai Chi emerged from the chaotic changes, and then two elementary parts began to generate from Tai Chi". These two elementary parts are "Yin (means gloomy, moon, night, die)" and "Yang (means bright, sun, day, living)". Yin and Yang alternate in space and time, they are the harmonious interaction of all opposing main bodies, objects, or pairs in the universe, just like two complementary and interdependent phases (Seidel & Ames, 2024).

In Feng Shui theory, "Yin" and "Yang" represent the corresponding geographical environment. The north of the mountain and the south of the river are called “ Yin”, and the south of the mountain and the north of the river are called “ Yang ”. In ancient China, people observed that in the south of the mountains, the sun's rays were relatively easy to reach, and the slopes here were sunny, giving people a bright and energetic feeling, thus belonging to the “ Yang ”. The north side of the mountain is shrouded in shadow all year round due to the difficulty of sunlight shining on it, giving people a deep and mysterious feeling, therefore it belongs to the “ Yin”. The sunlight on the north side of the water is relatively easy to shine on, and these water bodies are usually shallow and have clear colors, so they belong to the “ Yang ”. The sunlight on the south side of the water is difficult to reach, and these bodies of water are usually darker and have a deep blue color, hence they belong to the “ Yin”.

(2) Five Elements (Wu Xing) or Five Phases

The Five Elements are metal, wood, water, fire, and earth (soil) Their images are shown in Figure 3 (a)- (e). It first appeared in the ancient Chinese classic book "Book of Documents". It is a simple classification of all things in the world by ancient Chinese people, who believed that all things in the world are infinitely changed by the interaction

Figure 2 Yin-Yang Tai Chi diagram

of these five different substances (Wang et al. 2020).

3 The Five Elements

In the Five Elements, Metal represents the energy or phenomena of cleanliness, purification, change, austerity, and convergence; Wood refers to all plants, representing the energy or phenomena of growth, development, life, and relaxation; Water refers to all liquids, representing the energy or phenomena of infiltration, nourishment, moisturization, coldness, seclusion, and downward movement; Fire refers to all thermal energy, representing energy or phenomena of heat, warmth, ascension, and take off; Soil refers to all sand and gravel soils, representing energy or phenomena of load-bearing, fertility, and acceptance (Tan, 2022). The meanings and symbols of the Five Elements are as Table 1.

(a) metal (b) wood (c) water

(d) fire

(e) earth

Figures

(a) metal (b) wood (c) water (d) fire (e) earth

Table 1. The meanings and symbols of the Five Elements

Five Elements Metal Wood Water Fire Earth (Soil)

Energy or phenomena cleanliness, purification, change, austerity, convergence, malleable, and condensed growth, development, life, relaxation infiltration, nourishment, moisturization, coldness, soft, seclusion, downward movement heat, warmth, ascension, take off loadbearing, fertility, acceptance

Symbolizing hard, decisiveness, fortitude, shiny, and smooth Vitality life energy Wisdom, flow, transformation hot, passion, brightness thick, sturdy, stability, inclusiveness

Season autumn spring winter summer the transitional season of the four seasons

Colour White Green, blue black red, orange Yellow, brown

Direction West East North South Centre

Taste spicy sourness salty bitterness sweet

Shape evenly pressured circle vertically growing rectangle fluid and indeterminate sharply pointed triangle perfect square

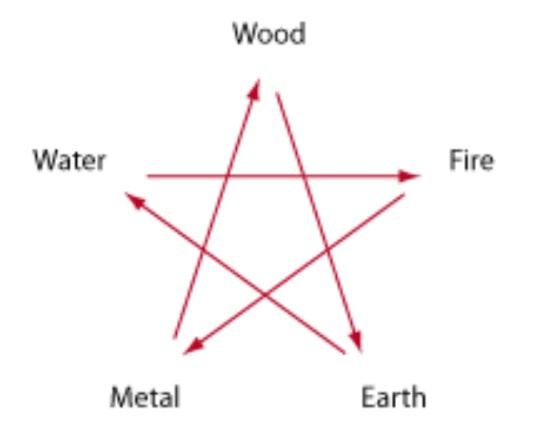

(i) The generating, inter-promoting, or enhancing cycle of the Five Elements

One of the five elements can enrich, nourish, promote, and generate another element, ultimately forming a cycle. Wood element can promote the fire element, the fire which eventually turns into ashes to form the earth (soil) element. The earth element nourishes and buries the metal element, which melts into a liquid state at a high temperature to form the water element. The water element nourishes the wood elements, including plants and wood. This forms a cycle, as shown in Figure 4 (a).

Figure 4. The Five Elements’ (a) generating cycle (b) suppressing cycle (ii) The controlling, destructing, or inter-restraining and the weakening cycle of the Five Elements

One of the five elements can suppress, overcome, or weaken another element, ultimately forming a cycle. Metal is harder or sharper than wood, and a metal knife can cut wood, so the metal element can suppress and overcome the wood element. Trees break through the earth and grow, so the wood element can suppress and overcome the earth element. The earth can absorb water and form embankments to hinder its flow, so the earth element can suppress and overcome the water element. Water can extinguish fires, so the water element can suppress and overcome the fire element. Fire can melt metals, so the fire element can suppress and overcome the metal element. This forms a cycle, as shown in Figure 4 (b). (3) The Eight Trigrams (Bagua)

The Eight Trigrams are eight symbols, each symbol represents a certain thing, attribute, or orientation, it is composed of two basic symbols, the Yang line (-) and the Yin line (⚋), and three lines form a symbol. The Eight Trigrams include Qian (☰), Kan (☵), Gen (☶), Zhen (☳), Xun (☴), Li (☲), Kun (☷), and Dui (☱). The orientation of the Eight Trigrams is divided into the Early Heaven Sequence (Figure 5 (a)) and the Later Heaven Sequences (Figure 5 (b)).

The Eight Trigrams in the early heaven sequence symbolize the primitive state of the universe. The Eight Trigrams in later heaven sequences represent the universe's changes and development. In Feng Shui architecture theory, the Eight Trigrams in later heaven sequences are generally adopted. The imageries of the Eight Trigrams are as follows. The directions and elements represented by Bagua are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. The Eight Trigrams Diagrams (a) in Early Heaven Sequence (b) in Later Heaven Sequences

(i) Qian (☰) is Yang Trigram representing heaven. To the northwest direction, the Five Elements belong to the metal element, representing the father in the family, 45 years old and above;

(ii) Kan (☵) is Yang Trigram representing water. To the north direction, also known as the Xuanwu position, the Five Elements belong to the water element, representing the second son in the family, aged 25-35;

(iii) Gen (☶) is Yang Trigram representing mountain, To the northeast direction, the Five Elements belong to the earth (soil) element, representing the young son in the family, aged 15-25;

(ix) Zhen (☳) is Yang Trigram representing thunder. To the east direction, also known as the Green Dragon position, the Five Elements belong to the wood element, representing the eldest son in the family, aged 35-45;

(x) Xun (☴) is Yin Trigram representing wind. To the southeast direction, the Five Elements belong to wood element, representing the eldest daughter in the family, aged 35-45.

(xi) Li (☲) is Yin Trigram representing fire. To the south direction, also known as the Vermilion Bird position, the Five Elements belong to fire element, representing the second daughter in the family, aged 25-35;

(xii) Kun (☷) is Yin Trigram representing earth. To the southwest direction, the Five Elements belong to earth, representing the mother in the family, aged 45 and above;

(xiii) Dui (☱) is Yin Trigram representing marsh, To the west direction, also known as the White Tiger position, the Five Elements belong to the metal element, representing the young girl in the family, aged 15-25.

The orientation position and color represented by each Hexagram (Trigram) in the Eight Trigrams (Bagua) from the perspective of Feng Shui are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Orientation position according to Feng Shui

2.1.3 The Ultimate Goal of Feng Shui: Gathering Chi

The important classic book of Taoism, "Chuang Tzu: Outer Chapters- Knowledge Rambling in the North" says "A human being is a gathering of Chi; the gathering of Chi leads to life, while the dispersal of Chi leads to death" (Chuang Tzu). Taoism talks about 'Chi', aiming to refine 'Chi'. Traditional Chinese medicine takes "Chi" as the general principle and believes that evil Chi causes human illness. Therefore, for people to be healthy and families to be safe, they must gather Chi.

2.2 The Application of Feng Shui in Architecture

Integrating Feng Shui into modern architecture involves spatial arrangement, orientation position, material selection, and the fusion of ancient Feng Shui principles with contemporary architectural practices. The application of Feng Shui in modern architecture includes the following aspects (Clarkson, 2023):

(1) Spatial arrangement: Designers consider the flow of energy or "qi" in the layout of the buildings to ensure that energy circulates smoothly and evenly throughout the entire space.

(2) Orientation position: The positioning of buildings is carefully planned to maximize the use of natural light and ventilation while maintaining consistency with the surrounding environment and its energy patterns.

(3) Material selection: Emphasize the use of natural materials such as wood and stone to create a sense of grounding and connection with nature.

(4) Colour and Symbols: Colours and symbols are chosen purposefully to enhance the desired energy and ambiance of the space.

Anjie Cho is a certified Feng Shui consultant, professional architect, and author, who has compiled some applications and precautions of Feng Shui in home architecture and

space design. Organized as follows (Cho, 2024).

1. Brighten up entry

The entry is the "mouth of Chi". It lets energy enter your home and your life. We should be uncluttered, need to sweep and clean up the area, and make sure this space is well-lit and bright.

2. Clean windows

Clear and clean windows allow more sunlight to enter. Sunshine will energize and wake you up, and can also render all the colors and objects you see. Light can make your home wider and more vibrant, helping you see the world around you more clearly.

3. The house doors work correctly and smooth entry and exit

Ensure that there is no bunch of clutter behind the door and that the hinges are not squeaking. The house doors represent your voice and communication, its smooth entry and exit represent opportunities that can come into your life, and your voice and communication are smooth, and no interference.

4. Commanding position

The commanding position refers to the farthest position of the room from the door (but not in a straight line with the door). It determines how you position yourself in life and is the location where you want to spend the most time in this space. Placing the desk and bed in these positions is the most ideal choice.

5. Remove obstacles on your path of walking or moving in the house

Obstacles affect the smoothness of your movements and the flow of "Chi" in the house. Over time, these obstacles will accumulate and cause problems for you.

6. Keep the space spacious and items tidy

De-cluttering your items such that tidy will create an open and new space, then make your space and your life more spacious.

7. Space clearing

Clean up the space and repair damaged items, such as lights. To fill the space with bright sunlight and let the sunlight clean your entire home. Let the sweet orange essential oil spread throughout the space.

8. Plants Bring Life Energy

Living green plants connect you with nature, embodying the energy of life and bringing freshness and vitality to your home. Green and vibrant plants are one of the key elements of Feng Shui in the house.

9. Express gratitude with a humble heart

Home is your refuge, a place for you to rest, nourish, celebrate, etc. Always be humble and grateful for your home.

2.3 Environmental Psychology

Our brain or body's absorption and secretion of neurochemicals or hormones may be the biological factors that affect our behaviors. Our unique cultural, religious, social, or personal experiences may be the social factors that influence our actions. Environmental psychologists combine these biological and sociological influences with the environmental factors from our surroundings, establishing a school of psychology that studies how people interact and participate in their environment. The core of the research is to explore how the environment affects us. Environmental psychology can address issues related to learning, attitude formation, motivation, perception, and the social interaction (LAMPS) principle. In certain environments, humans may adopt specific behaviors influenced by their surroundings. Environmental psychology can help us understand why these behaviors occur. Understanding the consequences of environmental changes through environmental psychology can benefit design disciplines such as architecture, interior design, and landscape design (Kopec, 2012).

In 1984, Roger Ulrich surveyed the recovery records of patients after cholecystectomy. He found that 23 surgical patients assigned to rooms with windows facing natural scenes had shorter hospital stays, fewer negative reviews in nurse records, and fewer use of potent analgesics (Ulrich, 1984). This sparked the medical community's first consideration of the economic benefits of exposure to nature. A carefully designed garden with a home-like appearance can create an aesthetic placebo, evoking people's familiarity and sense of belonging to a 'home away from home'. This landscape design has therapeutic and restorative effects (Sachs & Marcus, 2014). As a natural environment, hospital gardens are important in balancing high-stress levels, improving happiness, and supporting rehabilitation. After the investigation, it was found that the highest score was in rehabilitation. Participants used semantic difference (SD) factor analysis to reveal six factors related to design: emotion, happiness, nature, mysticism, tranquility, and touch (Cervinka et al., 2014). For the public, long-term exposure to residential green spaces can reduce physiological stress, improve human health, and alleviate depression and anxiety. Reducing air pollution is an important medium for linking green environments with depression and anxiety (Wang et al., 2024). The Natural environment with plants can alleviate physical and mental stress and negative emotions in the human body, while significantly increasing vitality (Yao et al., 2024). Exposure to the natural environment has a protective effect on mental health and cognitive function (Jimenez et al., 2021).

Vartanian et al. (2015) found that ceiling height and perceived enclosure (defined as perceived visual and locomotive permeability) have an impact on aesthetic judgments and approach-avoidance decisions in architectural design. Rooms with higher ceilings and open rooms are more likely to be considered beautiful and activate the structures involved in visual space exploration and attention in the dorsal stream. The decrease in visual and

motorcycle penetration characteristics perceived in enclosed rooms is more likely to trigger emotional reactions to exit decisions.

Environmental psychology has been applied not only in the medical and architectural design of hospitals but also in the architectural and spatial design of schools. According to research, classroom lighting can affect cognition and has been proven to affect academic achievement, attention rates, working speed, productivity, and accuracy, among other reported effects. LED lighting is most suitable for improving psychological and cognitive processes in the classroom, and more importantly, using higher correlated color temperature (CCT) and balancing between daylight and artificial light (Mogas-Recalde & Palau, 2021)

2.4 Urban Horticulture (Urban Farm)

Since entering the 21st century, human civilization has undergone earth-shattering changes on a global scale. The population is concentrated in cities, where they enjoy diverse facilities, better lifestyles, and employment sources. More than 50% of the world's population lives in cities. Although the area of all cities worldwide only accounts for 3% of the Earth's land, there are now over 3.5 billion people living in cities, and the number is constantly increasing (Sustainable Development Goals). The trend of population concentration in urban areas has caused problems such as reduced arable land, worsening malnutrition, and increased distance from cities to traditional food production sites.

In the past decade, the participation of communities in urban food production has steadily emerged. Urban horticulture and urban farms are beginning to rise. Utilize vacant land in the city, building rooftops (Figure 7), or balcony spaces to plant flowers, plants, and vegetables. Urban horticulture and urban farms can add green spaces to achieve sustainability, aesthetics, and offer fresh produce to residents (Cottam, 2022).

Figure 7. A rooftop farm in Thailand. Frango & Imbesi (2015) explore how design activism is expressed through urban horticulture and how citizens seek to change and challenge the quality of urban space

through two examples: LA Green Grounds (Figure 8) and Re: farm the City (Figure 9). By incorporating urban horticulture into design, urban horticulture proposes a new platform for designers to participate and considers a more inclusive design practice model. Although increasing evidence suggests that urban horticulture can further support more sustainable and resilient cities, significant scientific, engineering, and socio-cultural challenges must still be overcome to successfully integrate food cultivation more widely into cities (Edmondson, 2024)

Urban horticulture is becoming increasingly important for cities as it can become a source of income generation, ensuring our food security, guaranteeing food supply and sustainability, becoming a source of recreation and reduction of gender inequality, and even contributing to self-reliance and land management of cities. It impacts cities through increasingly diverse methods, including community gardens, terrace gardening, window gardens, indoor planting systems, container planting, and vertical gardening (Pal et al., 2022).

2.5 Sustainable Architecture

The World Commission on Environment and Development defines sustainability as

Figure 8 (a). LA Green Grounds (b) Turning food deserts into triumphs (LA Green Grounds).

Figure 9. Re:farm the city workshop.

development that meets current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Thomsen, 2013) When sustainability is applied to architecture, it refers to minimizing negative impacts on the environment, energy consumption, and human resource use, thereby design that creating a healthy living environment.

Sustainable architecture is also known as green architecture or environmental architecture. It is often understood as architecture with minimal impact on the environment while meeting the needs of users (Harań, 2025). Sustainable architecture is reflected in the materials, construction methods, resource utilization, and overall design. Architects must conduct intelligent design and use existing technologies to minimize the amount of resources consumed during construction, use, and operation, as well as reduce the harmful impacts on the environment, ecosystems, and communities caused by emissions, pollution, and waste of their components (Ragheb et al., 2016).

At present, new building technologies provide increasing opportunities for creating an infrastructure that can respond to and adapt to the needs of all users (Ferdous & Bell, 2020) Therefore, a sustainable building design that reduces the amount of resources consumed during construction, use, and operation, minimizes environmental impact, and meets user needs is indeed feasible in terms of technology, materials, and construction methods. For the sake of future generations, it should be promoted and implemented.

3. Research Methods and Case Study

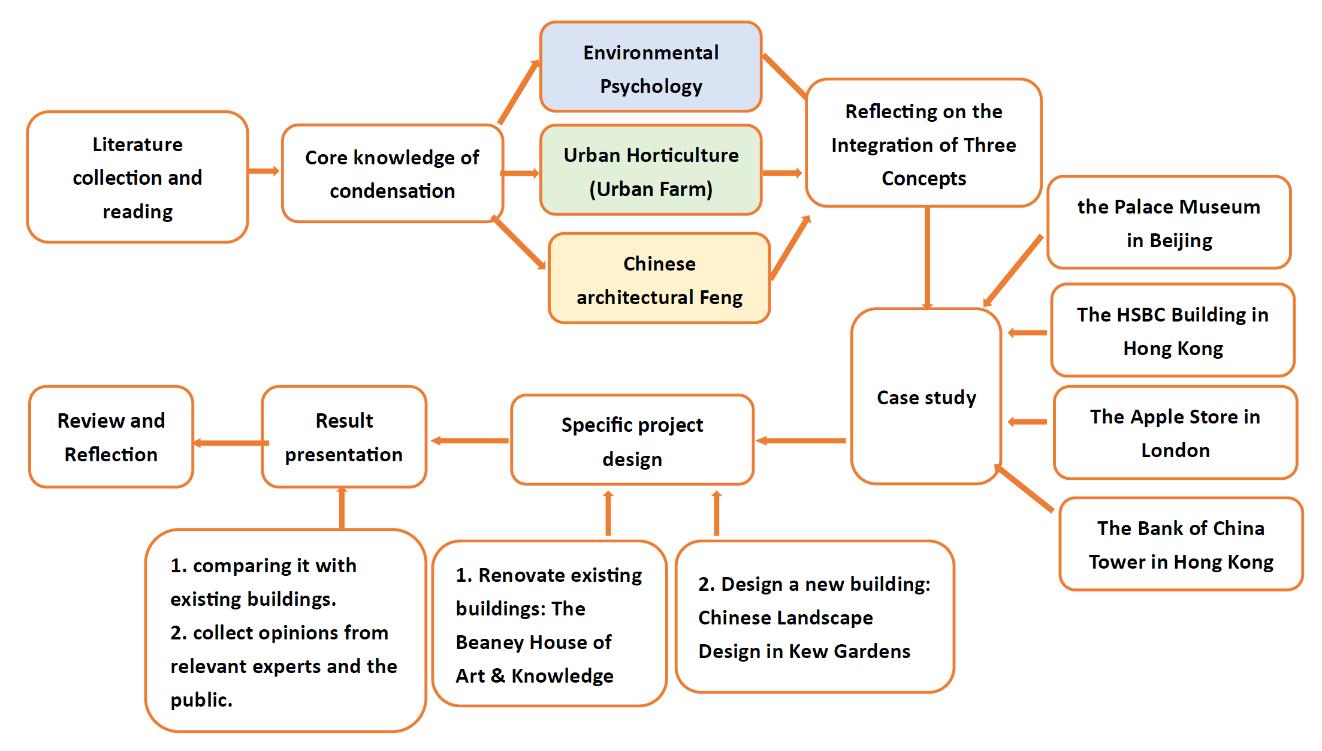

In this article, I want to explore how traditional Chinese spatial philosophy Feng Shui can influence contemporary architecture through the lens of environmental psychology and sustainable design.

Feng Shui is often seen as a cultural belief, but I see it as a system of spatial logic with real potential for enhancing mental well-being, energy efficiency, and ecological harmony in built environments.

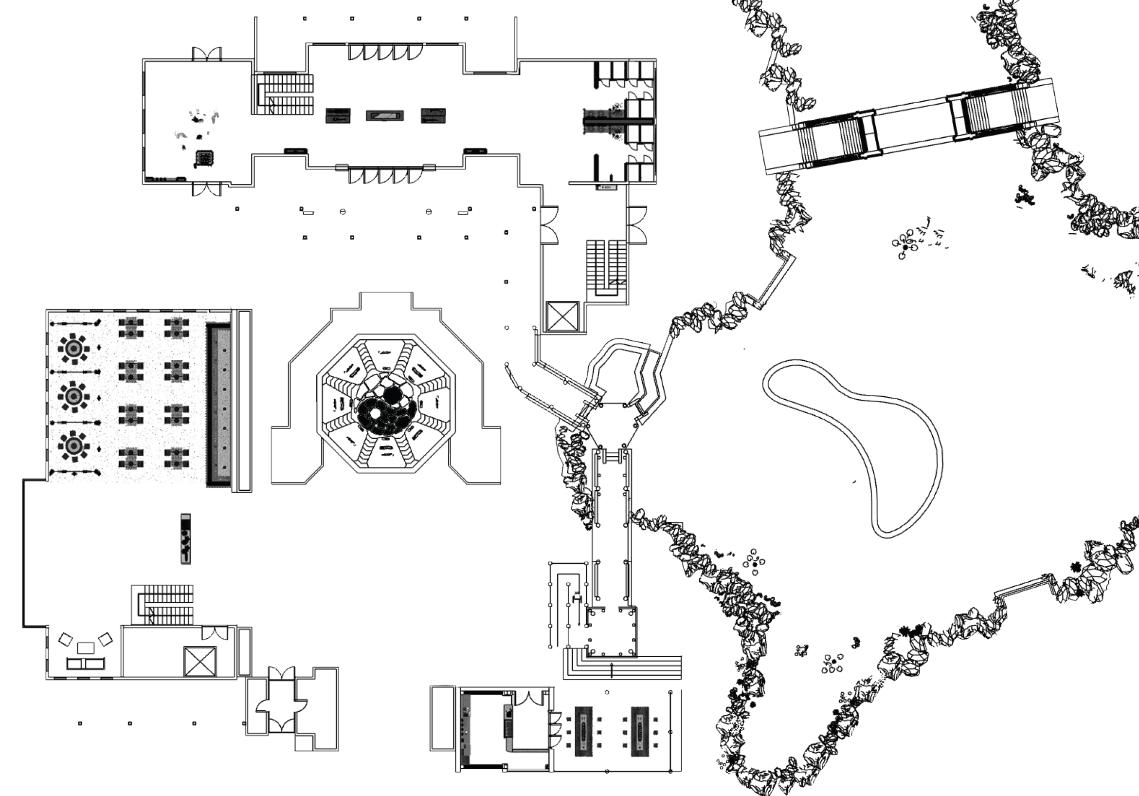

My proposed research takes a mixed-methods approach, combining interviews, case studies, environmental data, and spatial analysis. I hope to build an evidence-based framework that connects ancient wisdom with modern design thinking, contributing to sustainable urban planning and human-centred architecture. My research technology roadmap is shown in Figure 10

10. My research technology roadmap

3.1. Case Studies on Feng Shui Architecture

This article first selects an ancient Chinese feng shui architecture, the Palace Museum in Beijing in China, as a case study to gain a deeper understanding of the application of feng shui theory in architectural design. Then choose three modern Feng Shui buildings and extract the principles and practices of Feng Shui theory applied to contemporary architecture. These three modern feng shui buildings are the HSBC Building in Hong Kong, the Apple Store in London, and the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong.

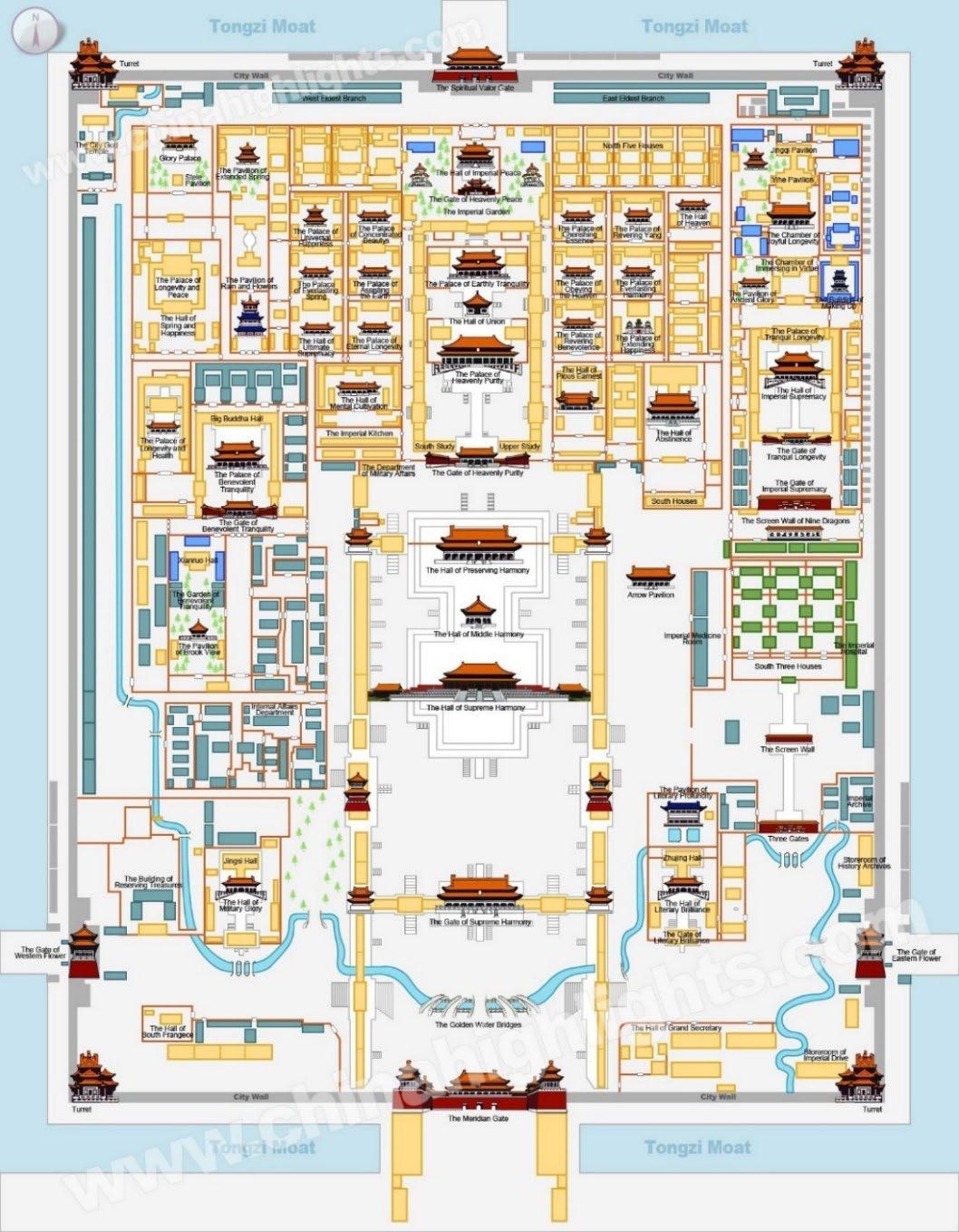

3.1.1 Feng Shui Research at the Palace Museum in Beijing (China Highlights, 2021)

The Palace Museum in Beijing is the largest medieval palace in the world, also known as the Forbidden City. It has a history of over 600 years and was the main imperial palace

Figure

of the last two dynasties in China: the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). The Palace Museum covers a vast area of about 150000 square meters, including approximately 980 buildings. Most of its buildings are constructed based on traditional Chinese culture and the application of Feng Shui theory, mainly including:

Figure 11 The Forbidden City was symmetrically on the north-south central axis of old Beijing.

(1) Layout: North-South Power Axis, the main entrance faces south

The layout of the Forbidden City runs from the main south entrance through its majestic halls to its northern emperors' quarters, with the north-south axis being one of

the most important features of the Forbidden City's layout. The main entrance of the Forbidden City faces south, and the main road leading to the palace extends along the north-south axis. The imperial palace must be built in the center of the capital city on its north-south axis. The important buildings must be located on the north-south 'power axis'. In Chinese culture, the North Star is the only seemingly stationary star in the northern sky, believed to be heaven, while the emperor is considered to represent heaven and is therefore placed in the north.

The imperial palace is in the middle, facing south, and the north-south axis divides the Forbidden City into two halves. The left is east, belonging to Yang, where the sun rises. The right is west, belonging to Yin, where the sun sets. In addition, according to traditional Chinese culture, the status of the left side is much higher than that of the right side. Therefore, the Royal Ancestral Hall is built on the left side of the north-south axis, with the earthen altar and harvesting platform located on the right side. The basic principle of the architecture of the Forbidden City is Heaven central, mankind left, and nature right.

(2) Three auspicious colours

The main colour of the Forbidden City is yellow, which has been the exclusive colour of the royal family in China since the Sui Dynasty (581-618) until the Qing Dynasty, because the emperor is the ruler of the country and resides in the center. According to the Five Elements theory, the center belongs to the earth element, and its colour is yellow. The glazed tiles on the roofs of buildings in the Forbidden City and the bricks on the ground in many places are yellow, and many decorations in the buildings are also painted yellow.

Most of the pillars in the Forbidden City are painted red, which is an auspicious and festive colour associated with happiness, wealth, and power. The walls and window frames of buildings painted red not only appear festive but also eye-catching. Green symbolizes growth and is a very important colour that can be found in wall decorations and on the roof tiles of buildings such as the princes' quarters.

Figure 12. The main Forbidden City colours (Red walls, yellow roofs and green/blue decorations decorations)

(3) Stone and Bronze Lions

Many buildings have stone lions or bronze lions (like Shi Gandang) next to their gates that symbolize guardians and have anti-evil effects. Lions always appear in pairs, standing outside the door, facing inside the door, with females on the left and males on the right. The male lion's right paw is placed on a ball, this ball symbolizes the rights, status, friendship, and emotions guarded by males. The female lion's left paw holds a cub, representing the female guarding the home and children, ensuring the continuity of offspring and the prosperity of the family. When they appear in pairs, they represent the happiness and prosperity of a family or institution.

13. Stone Lions (a) the female lion (b) the male lion

3.1.2 Three modern Feng Shui architectures study

The three selected modern Feng Shui buildings are the HSBC Building in Hong Kong, the Apple Store in London, and the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong. Their design concepts, ideas, construction processes, and results are summarized in Table 2

Table 2. Introduction to three selected modern Feng Shui buildings Case Study Architect Concepts Processes Outcomes

The HSBC Building (Hong Kong) Norman Foster + Partners

The Apple Store (London) Norman Foster + Partners

1. The tall and hollow atrium gathers "Chi".

2. Trees and vegetation block negative energy.

The Bank of China Tower (Hong Kong)

I.M. Pei

1. Flexible "city square" design, increasing transparency and natural light.

2. The banyan tree and glowing ceiling create a warm atmosphere.

1. The appearance of bamboo symbolizes growth and strength.

2. Sharp building edges pose a challenge to feng shui harmony.

1. The atrium design introduces natural ventilation and emphasizes a sense of grandeur.

2. Convert the land in front of the building into a public park.

1. The double-height indoor space creates a comfortable social environment.

2. The clockwise energy flow design stimulates spontaneous purchasing behavior.

1. Reflective glass maximizes natural lighting requirements.

2. The sharp 'blade' shape creates negative feng shui effects (later resolved by HSBC using the 'cannon' on the roof ).

1. Iconic energy-saving design with reflective sunlight characteristics.

2. Consolidating HSBC's global position (HSBC has always been the largest bank in Hong Kong)

Becoming one of the stores with the highest annual sales per square foot in London retail.

Despite controversy in feng shui, it has become a globally iconic skyscraper.

Figure

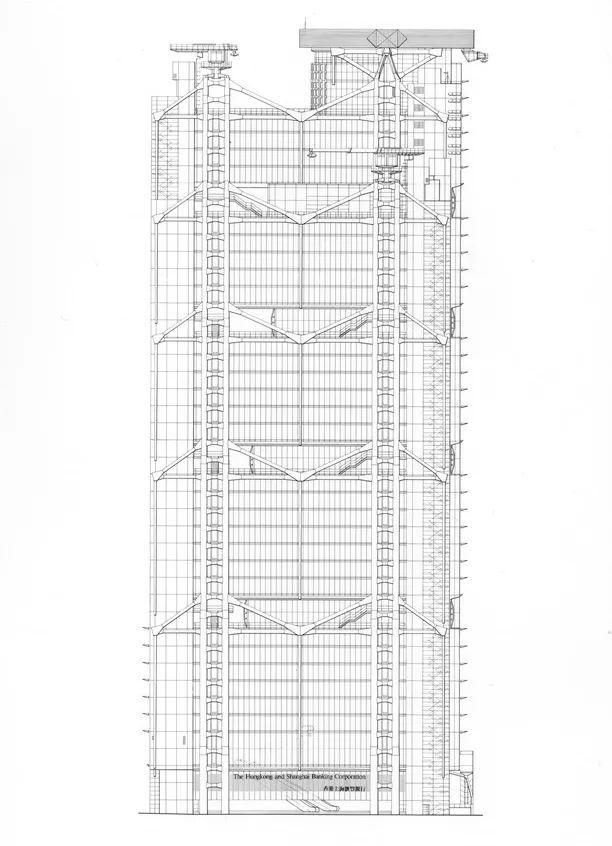

(1) The HSBC Building in Hong Kong

After Norman Partners in the UK consulted several Feng Shui masters, the architect, Norman Foster, designed the HSBC building in Hong Kong in 1986. It took 6 years from conception to completion. The architectural form is expressed in a stepped profile of three individual towers. The three towers are respectively 29, 36, and 44 stories high, create floors of varying width and depth, and allow for garden terraces (Pagnotta, 2011). The main building (Figure 14) includes 4 underground floors, totaling 46 floors, and a total height of 180 meters. It is constructed from 30000 tons of steel and 4500 tons of aluminum.

Figure 14. (a) Front facade (b) Facade design of the HSBC Building in Hong Kong.

Figure 15. The tall and hollow atrium in HSBC building.

Figure 16 Two free-standing escalators on the square

The building has a total of 8 masts, each consisting of 4 columns, supporting 5 independent double-layer high steel suspension structures. The span between the masts is 33.5 meters, and the cantilever distance is 10.7 meters. The system carries all structural loads, allowing the building to create a spectacular column-free bottom layer. The first floor of HSBC Bank is a tall and hollow atrium (Figure 15). There are two supposedly world's longest free-standing escalators on the square (Figure 16), stretching upwards at strange angles for feng shui reasons, they symbolize a dragon's beard sucking wealth into its belly.

The application of Feng Shui in the HSBC Building is summarized in Table 3, and the explanation from the perspective of environmental psychology is shown in Table 4.

Table 3 The application of Feng Shui in the HSBC Building in Hong Kong

The application of Feng Shui

Spatial arrangement

Orientation position

The HSBC Building in Hong Kong

1. The tall and hollow atrium gathers "Chi".

2. The inclined design of escalators also helps guide energy inside buildings. They aim to deflect harmful energy, ensuring that it does not reach the upper floors.

1. Convert the land in front of the building into a public park to balance energy flow The trees and vegetation can block negative energy.

2. The atrium design introduces natural ventilation and emphasizes a sense of grandeur.

3. In feng shui, the orientation of buildings and their relationship with the surrounding environment are crucial for utilizing positive energy. The HSBC building faces the open Victoria Harbour, unobstructed by other buildings, and is considered auspicious, bringing prosperity to the bank.

Material selection steel and aluminum

Colour and Symbols

To address the negative energy caused by the building's appearance with sharp, knife-like edges in the nearby Bank of China Tower, HSBC has installed two "cannons" on the roof of its building. These two 'cannons' are aimed directly at the Bank of China Tower, using the imagery of "cannons" to suppress the knife-like and neutralize harmful energy.

Table 4. Explanation HSBC Building from the Perspective of Environmental Psychology

The application of Feng Shui Perspective of Environmental Psychology

1. The tall and hollow atrium gathers "Chi".

2.The atrium design introduces natural ventilation and emphasizes a sense of grandeur.

3. In feng shui, the orientation of buildings and their relationship with the surrounding environment are

A broad perspective and range of activities affect a person's psychological state and personality development. A high and hollow atrium is more likely to be considered beautiful and makes people less likely to make evasive decisions, making them more proactive (Vartanian et al., 2015).

crucial for utilizing positive energy.

The HSBC building faces the open Victoria Harbour, unobstructed by other buildings, and is considered auspicious, bringing prosperity to the bank.

Convert the land in front of the building into a public park to balance energy

flow The trees and vegetation can block negative energy.

Windows facing natural landscapes or nearby green coverage can create an aesthetic placebo with therapeutic and restorative effects (Sachs & Marcus, 2014), as well as reduce physiological stress, improve human health, and alleviate depression and anxiety (Yang et al. 2020; Wang et al., 2024).

The Natural environment with plants can alleviate physical and mental stress and negative emotions in the human body, while significantly increasing vitality (Yao et al., 2024). Exposure to the natural environment has a protective effect on mental health and cognitive function (Jimenez et al., 2021)

Before the HSBC building was built, the management of HSBC bought the building land, not only the HSBC building site, but also the land in front of it was purchased and handed over to the government for management. The government was required to build a park here and plant trees inside. In Feng Shui theory, trees can ward off negative energy. In environmental psychology, personnel working in HSBC buildings can see the trees and green vegetation in the opposite park through the windows, reducing work pressure and improving work performance.

Then they placed a pair of lion sculptures on both sides of the gate (Figure 17), using the fierce energy of beasts in Feng Shui theory to ward off negative energy. In traditional Chinese culture, it is customary to place a pair of lion sculptures at the entrance of buildings, including the ancient and modern governments, armies, and some enterprises, hotels, especially larger financial institutions, to appear noble and dignified, and can evoke respect from passersby.

Figure 17. A pair of lion sculptures placed on both sides of the HSBC gate.

The first floor of the building is designed as an open space, consisting of a tall and hollow atrium. In architectural ecology, this narrow and high atrium space creates a chimney effect, which drives natural ventilation inside the building. According to the Feng Shui theory, this design can introduce more "Chi".

According to environmental psychology, I believe that a tall atrium can make customers feel that the building is magnificent and grand, and then respect and trust the owner of the building, thereby facilitating successful transactions.

(2) The Apple

Store in London

The Apple Regent Street (Figure 18) was designed in 2016 in close collaboration between Apple’s teams led by Jonathan Ive, chief design officer, and Angela Ahrendts, senior vice president of Retail, and Foster + Partners. It creates a relaxed environment and incorporates Apple's new features and services.

The interior space of the Apple Store in London is a 7.2-meter-high double-decker hall, creating a flexible and welcoming 'town square' style space. The design fills the store with natural light by enhancing the transparency from the street and floods, greatly improving the visual connection between the two levels (Figure 19).

The Apple Store in London is in the "prime location" of Regent Street. It is located at a

Figure 18 The appearance of Apple stores in London

Figure 19. Indoor Open Design of Apple Store in London.

slight turn and can receive more energy. This energy comes from Regent Park and flows down Portland Square and Regent Street. Due to a slight tilt, energy enters the store directly at a certain angle. Once entering the store, energy is forced to move in a clockwise circular manner (Figure 20) In the northern hemisphere, people will feel comfortable when the energy moves in an anti-clockwise direction. We can see that when water flows down into a plughole, the water flows move into a plughole in an anti-clockwise direction. This phenomenon is well-known as the Coriolis effect. However, when energy flows in a clockwise direction in the northern hemisphere, people will feel uncomfortable and confused. It's just like the confused atmosphere in “End of Season Sales” or “Black Friday” sales. People are rushing to buy "bargains" in the crowd. In this chaotic environment, people lack logical thinking and make impulsive purchases. The ultimate result is that people buy more (Oon, 2024) The application of Feng Shui in the Apple Store in London is summarized in Table 5, and the explanation from the perspective of environmental psychology is shown in Table 6.

The

Spatial arrangement

Orientation position

The

1. Flexible "city square" design, increasing transparency and natural light.

2. The double-height indoor space creates a comfortable social environment.

1. The twelve Ficus Ali trees on the ground level and the glowing ceiling create a warm atmosphere.

2. The clockwise energy flow design stimulates spontaneous purchasing behavior.

3. The Apple Store in London is in the "prime location" of Regent Street

Material selection stone, wood and terrazzo

Colour and Symbols

Grey-white (stone), and the original color of wood

The signature Apple display tables

Figure 20. (a) The Google Earth Image (b) The energy moves of the Apple Store in London.

Table 5 The application of Feng Shui in the Apple Store in London

application of Feng Shui

Apple Store in London

Table 6. Explanation Apple Store in London from the Perspective of Environmental Psychology

The application of Feng Shui Perspective of Environmental Psychology

1. Flexible "city square" design, increasing transparency and natural light.

2. The double-height indoor space creates a comfortable social environment.

The twelve Ficus Ali trees on the ground level and the glowing ceiling create a warm atmosphere.

A broad perspective and range of activities affect a person's psychological state and personality development. A high and hollow atrium is more likely to be considered beautiful and makes people less likely to make evasive decisions, making them more proactive (Vartanian et al., 2015).

The Natural environment with plants can alleviate physical and mental stress and negative emotions in the human body, while significantly increasing vitality (Yao et al., 2024).

Exposure to the natural environment has a protective effect on mental health and cognitive function (Jimenez et al., 2021).

The clockwise energy flow design stimulates spontaneous purchasing behavior.

This may be because clockwise energy drives people to move in a clockwise direction, which is inconsistent with people's habit of moving in a counterclockwise direction in sports fields and causes anxiety.

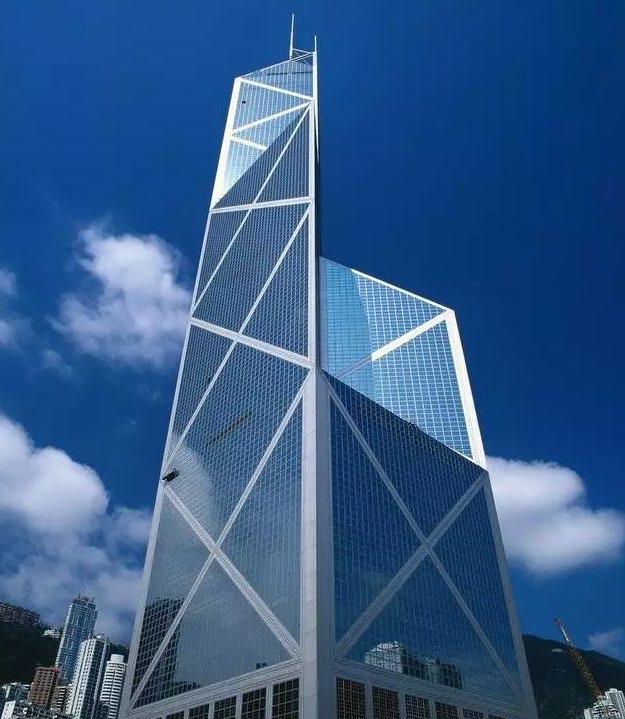

(3) The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong

The Bank of China Tower was planned and designed by renowned architect I.M. Pei in 1982. Construction began in April 1985 and was completed in 1989. The building has a sharp and angular structure with three sharp edges. The design of this building adopts structural expressionism. It resembles growing bamboo shoots, symbolising livelihood and prosperity (Figure 21).

The Bank of China Tower is located near the Central MTR station. The building consists of four triangular towers made of glass and aluminum, all varying heights, the base of the four towers is granite, rising from a triumphal podium of beautiful granite. The geometric changes that occur as the building rises into the sky are the most interesting aspect of this tower. The sharp angles and points of interest create an appearance that contrasts with the dominant flat buildings in the city. The silver-blue reflective glass used in the tower creates objects that reflect light on sunny days and nights (Figure 22).

The silver-blue reflective glass as the building's skin not only reflects the constantly changing images of the sky and city, but also absorbs sunlight, thereby reducing energy consumption for lighting and heating costs (WikiArquitectura, 2020; RTF, 2022) The application of Feng Shui in the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong is summarized in Table 7, and the explanation from the perspective of environmental psychology is shown in Table 8.

Table 7. The application of Feng Shui in the Bank of China Tower

The application of Feng Shui

Spatial arrangement

The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong

1. The Bank of China Tower primarily serves as the headquarters of the Bank of China, featuring high-end office spaces, retail stores,

Figure 21 (a) Front facade (b) Facade design of the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong

Figure 22. The silver-blue reflective glass reflect light on (a) sunny day and (b) night

and a stunning observation deck that offers panoramic views of the city below.

2. Internally, flexible space and offices are provided for the bank.

3. The observation deck on the 43rd floor is continuously open to the public, but a reservation is required to enter the observation deck on the 70th floor.

Orientation position

1. Sharp angles and reflective glass maximize energy efficiency, but challenge feng shui harmony.

2. The sharp "blade" shape has a negative feng shui effect on the surrounding buildings.

Material selection vertical and horizontal steel members, reinforced concrete, granite, and silver-blue reflective glass framed in aluminum.

Colour and Symbols

1. silver-blue reflective glass building

2. The design inspiration comes from bamboo, symbolizing strength and vitality.

Table 8. Explanation Bank of China Tower from the Perspective of Environmental Psychology

The application of Feng Shui Perspective of Environmental Psychology In terms of feng shui, the Bank of China Tower is considered the "most aggressive building in the world" because the edge of its front triangle at the front point to its competitors. This is what the Chinese call "direct attack" in the language of Feng Shui. Later, the neighbor HSBC used the "cannon" on the roof to resolve the feng shui issue.

People in the surrounding buildings of the Bank of China Tower, when they face the sharp edges of the Bank of China Tower, will have a psychological anxiety like facing knives, which affects their physical and mental health. HSBC has built two "cannons" on the top floor facing the Bank of China Tower, which will give people working at the Bank of China Tower a sense of relief and even superiority, because the power of cannons is far greater than knives.

The Bank of China Tower has won the "Excellent" rating award in the 2002 Hong Kong Building Environmental Assessment, the Top 10 Best Buildings in Hong Kong by the Hong Kong Institute of Architects in 1999, the Marble Building Award in 1992, the AIA Reynolds Memorial Award in 1991, the Outstanding Engineering Award in 1989, and the Outstanding Engineering Certificate in 1989.

From the perspective of Feng Shui theory, the Bank of China Tower is a terrible example of Feng Shui architecture. The sharp-shaped Bank of China Tower is like a threebladed knife. The first side of the blade points towards the "Governor's Mansion", and coincidentally, in December 1986, Duke Youde died suddenly of a heart attack in Beijing, becoming the only Governor to pass away while in office. The second side of the blade pointed towards the military camp of the stationed troops in Hong Kong at that time (British army). The third side of the blade points to HSBC, where HSBC's performance

suddenly regressed and its stock price plummeted at that time.

Later, after consulting a Feng Shui master, HSBC's management creatively erected two "cannons" on the rooftop to engage in a "knife cannon battle" with the Bank of China to defuse the bank's "killing Chi". Coincidentally, the stock price rebounded as a result.

In the late 1990s, the location of the Yangtze River Group Center was awkwardly sandwiched between the Bank of China and HSBC. With the advice of feng shui masters, the Yangtze River Center was built in a shield-like shape on all sides, with an impenetrable appearance resembling a fortress, and cleverly avoiding the relative position of "knives and cannons" in height. Although it was repeatedly criticized for not being aesthetically pleasing, but has been safe and sound since its completion.

3.1.3 Summary of Case Studies

Based on the case studies, relevant practices of Feng Shui theory application, environmental psychology, urban horticulture, and sustainability were extracted, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Summary of Case Studies

Feng Shui Environmental Psychology

1. Introduce natural elements such as trees and water to balance ‘Chi’. The trees and vegetation can block negative energy.

2. Design tall spaces to enhance grandeur and harmony.

3. Facing a broad environment with wide views.

4. The direction of water flow in the northern hemisphere is counterclockwise. A comfortable atmosphere is created when the energy of "Chi" reflects this flow.

1. Tall space earns respect and trust (HSBC).

2. Flexible layout stimulates participation and creativity (Apple Store).

3. The vegetation outside can be seen from the window, which helps to reduce stress (HSBC). The Natural environment with plants can alleviate physical and mental stress and negative emotions in the human body (Apple Store).

4. Indoor plants bring nature and comfort to indoor spaces (Apple store).

Urban Horticulture Sustainability

1. The park in front of the building can be planted with fruit trees. (HSBC).

2. Indoor plants bring nature and comfort to indoor spaces (Apple store).

1. Use reflective glass and natural ventilation to achieve energy savings.

3.1.4 Challenges and Opportunities of Feng Shui Architecture

The challenges and opportunities faced by Feng Shui architecture are summarized in Table 10

Table 10. The challenges and opportunities of Feng Shui architecture Challenges Opportunities

1. Feng Shui theory lacks scientific explanations and verification methods.

1. Feng Shui has existed and developed in non-scientific environments for

2. Joseph Needham believes that Feng Shui theory is pseudo-science, but he believes that Feng Shui theory contains aesthetic elements.

3. The scientific mechanical worldview of Western scholars makes it difficult to accept the Feng Shui theory.

4. The research applying Feng Shui theory to architecture mainly focused on China and Southeast Asian countries, and most research papers are published in local languages. There are not many studies that apply Feng Shui theory to architecture and have been published in English.

3.2.

Methods of experimental practice

centuries, and it is the default worldview in China and Southeast Asia, and naturally has its significance and rationality.

2. Feng Shui theory has a vast market in Southeast Asia, especially in China.

3. For over half a century since Joseph Needham, not only Chinese and Southeast Asian scholars but also Western scholars have begun to study Feng Shui theory from a scientific perspective.

4. The English literature on the application of Feng Shui theory to architecture needs further development.

This study aims to conduct in-depth research on environmental psychology and Chinese architectural Feng Shui theory and attempt to interpret Chinese architectural Feng Shui theory from the perspective of environmental psychology. Then, through case studies, the application principles of Feng Shui theory in architectural design are extracted, and the extracted application principles are explained through environmental psychology. Finally, taking the renovation of existing buildings and the design of new ones as practical projects, Feng Shui theory is applied to architectural design and achieved through sustainable building materials. I will select an existing building to improve the design and a site to design a new architecture based on Feng Shui theory, and explain the support of scientific theories in environmental psychology, combined with the concepts of urban horticulture and sustainable architecture for practical design. Present the designed floor plans, renderings, and models for exhibition, collect opinions from relevant experts and the public, and reflect on and summarize them.

3.2.1 Renovate existing buildings

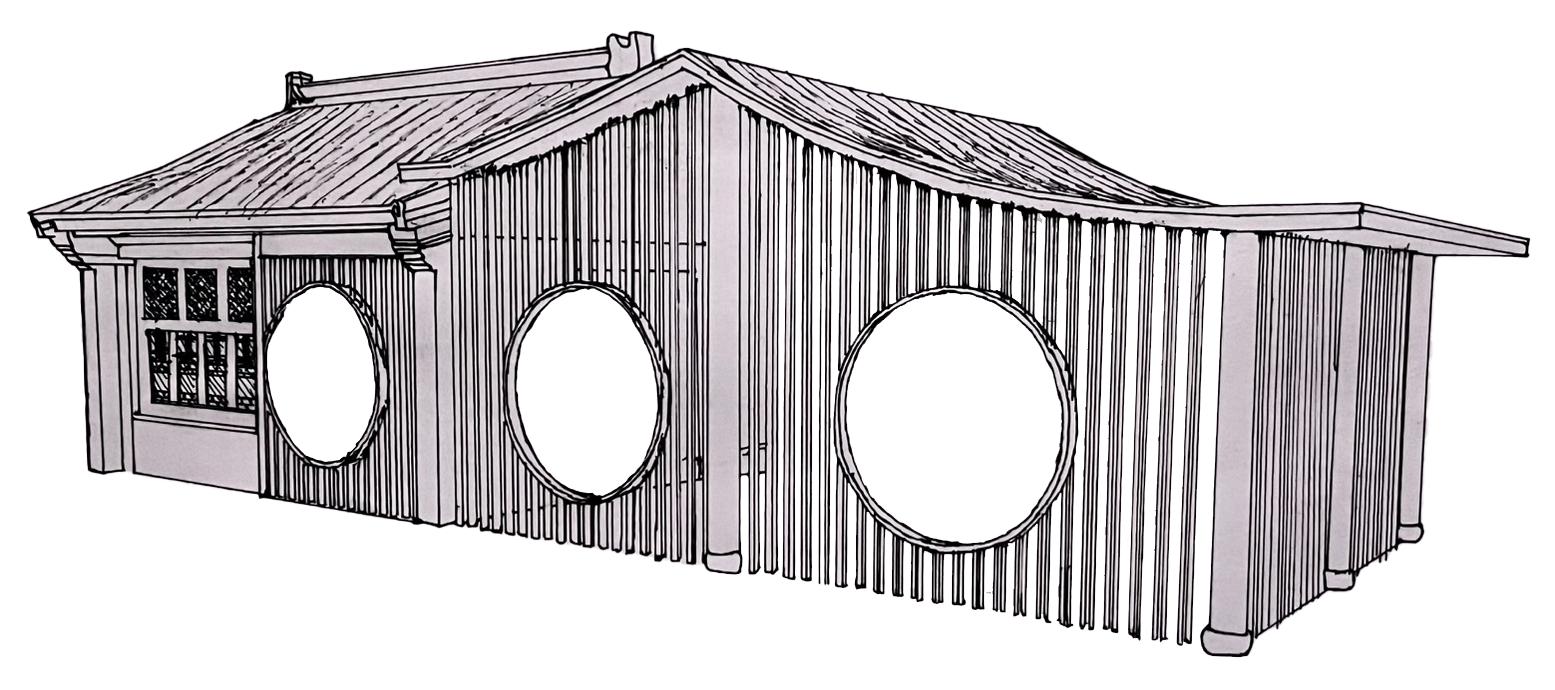

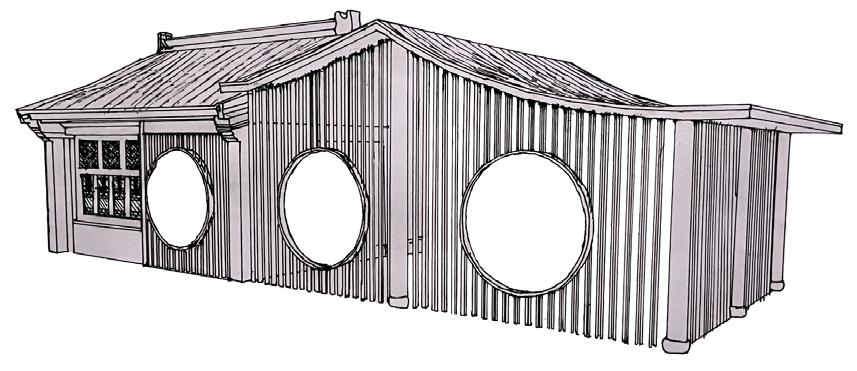

My first attempt is to design and renovate the "Beaney House of Art and Knowledge". I will visit and conduct a site survey to find areas that can be renovated and improved in existing architecture, including structure, materials, interior design, and exhibition hall design. I will attempt to use feng shui theory as a guide for design and implement sustainable building materials.

(1) History of the Beaney House of Art and Knowledge

The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge building takes its name from its benefactor, Dr. James George Beaney (Figure 23). He was born in Canterbury and studied medicine in Edinburgh and Paris. Then he emigrated to Australia and achieved success there. He

became Honorary Surgeon at the Melbourne Hospital and a pioneer in children's health, family planning, and the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases in Australia. After his death in 1891, Dr. Beaney left money in his will to the city of Canterbury to build an "Institute for Working Men". The Canterbury Corporation convinced the Charity Commission to use this money to build a new museum and library. On 16 September 1897, Canterbury Mayor George Collard laid the foundation stone for the Beaney Institute. The architect is A H. Campbell, the building was officially opened on 11 September 1899 (Canterbury Museums & Galleries, 2015).

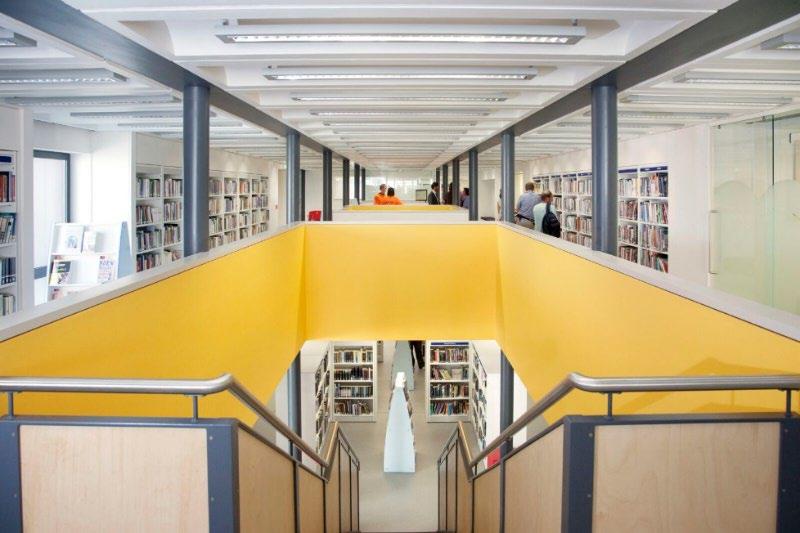

(2) Architectural Features

The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge was designed by architect A H Campbell and built in 1897-99. The building has two floors and a basement. The entrance of the steps has two wooden griffins that guard on each side. There are three gables on the roof, with the largest one in the middle (Figure 24). Its facade facing the High Street has undergone the terra-cotta ceramic mosaics re-bedding and renewal of all lead-work.

The Beaney House has created a new accessible public entrance for the expanded building footprint. This entrance leads to a dramatic top-illuminated foyer space that

Figure 23. Dr. James George Beaney.

Figure 24. (a) Front facade (b) Facade design of the Beaney House

progresses sequentially, ultimately forming a new library and gallery (Figure 25). The Beaney Museum has a large collection of animal specimens from the Victorian era, including specimens of Chinese pangolin, Brazilian three-banded armadillos, and Australian duck-billed platypus. There are also cultural relics from ancient civilizations of Egypt, Rome, and Greece in the exhibition hall. Other interesting details include an iron weather vane, stained glass windows, and a range of decorations such as grotesques and animal designs made in wood and terracotta (Canterbury Museums & Galleries, 2025)

25. Library facilities have been moved to two-storey accommodation.

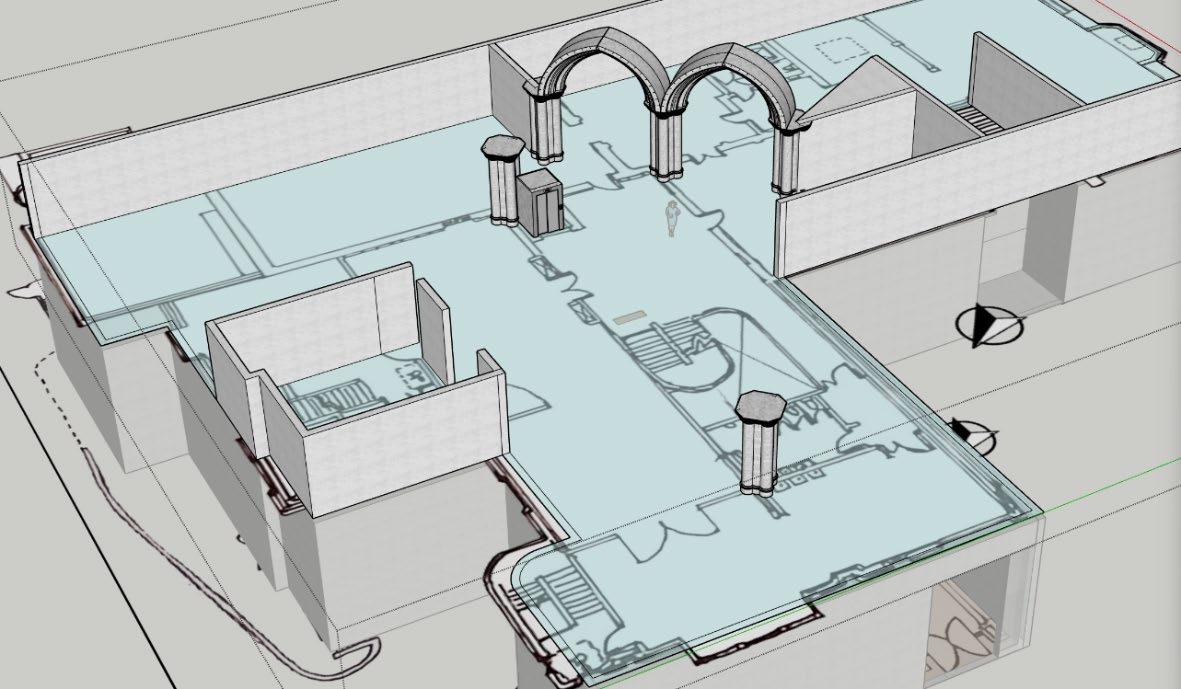

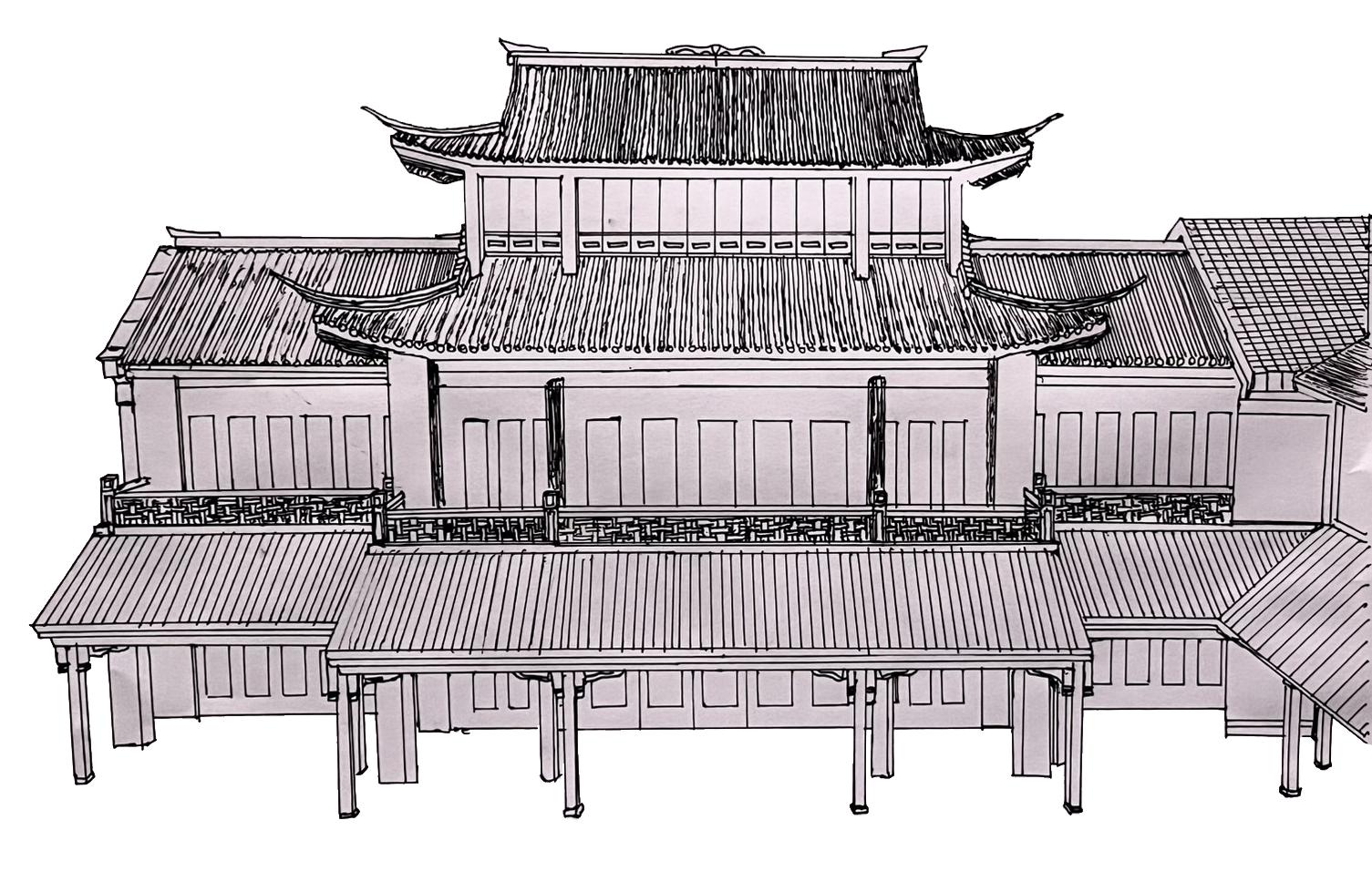

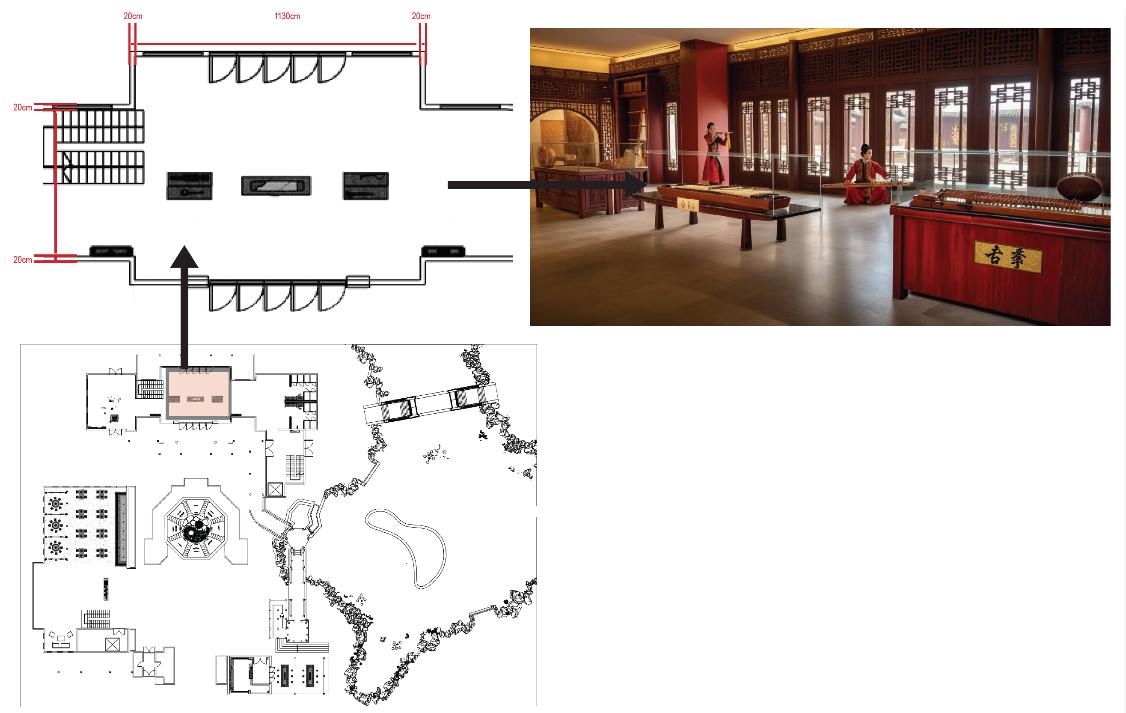

3.2.2 Design a new building

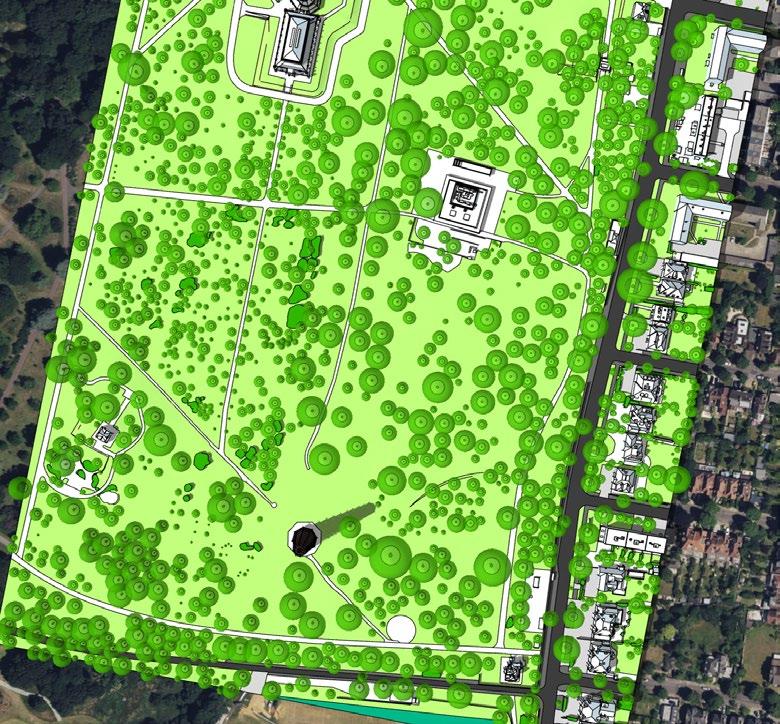

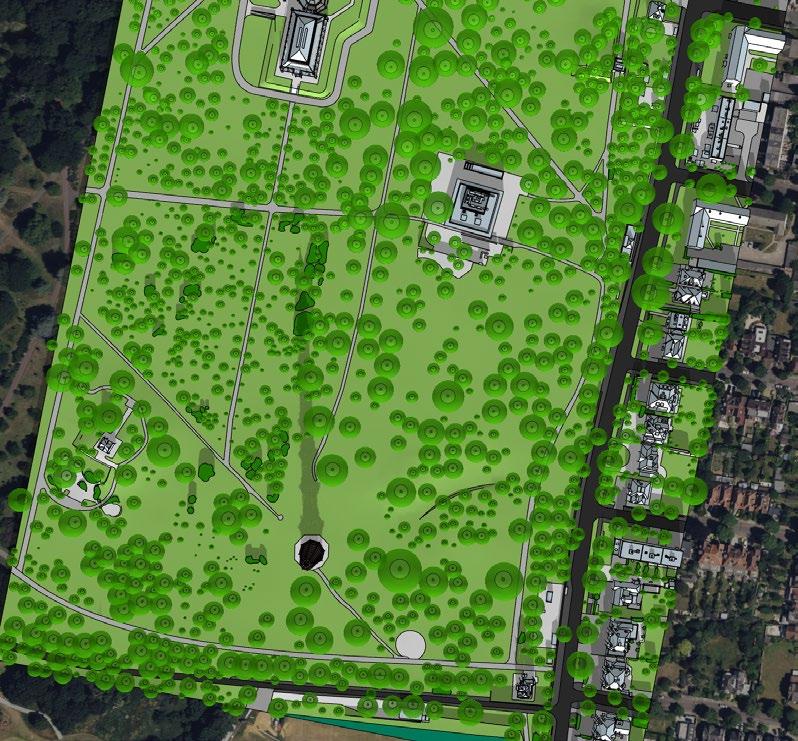

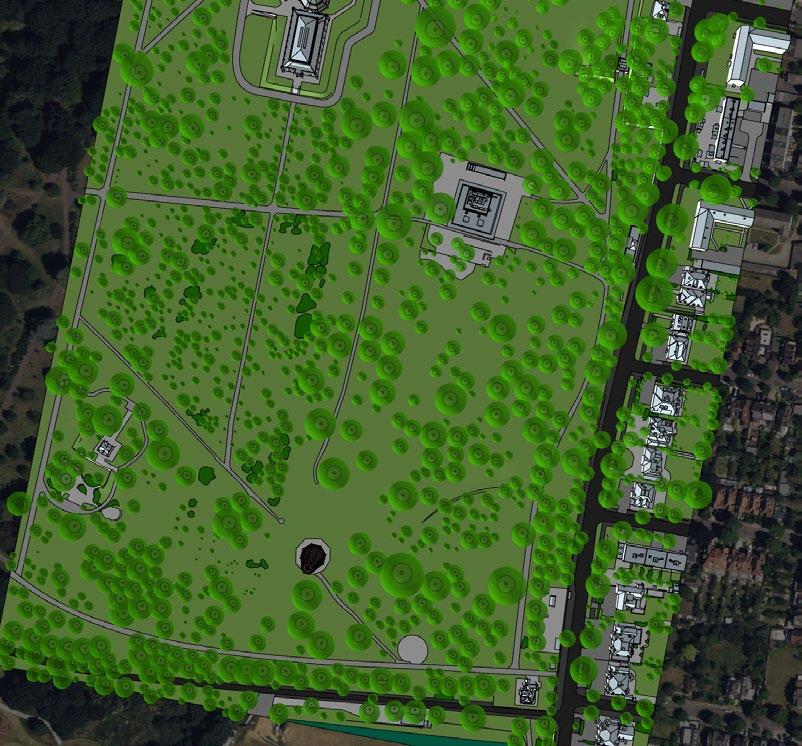

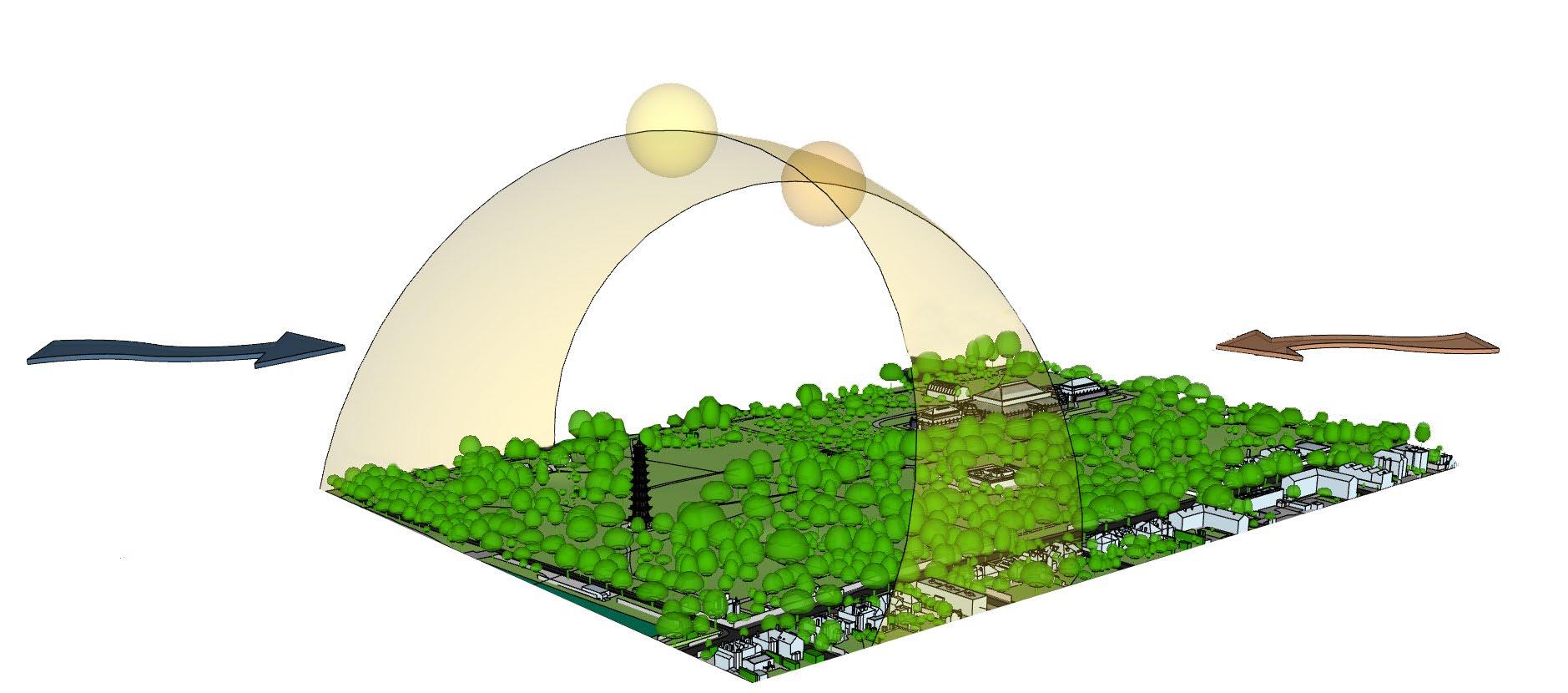

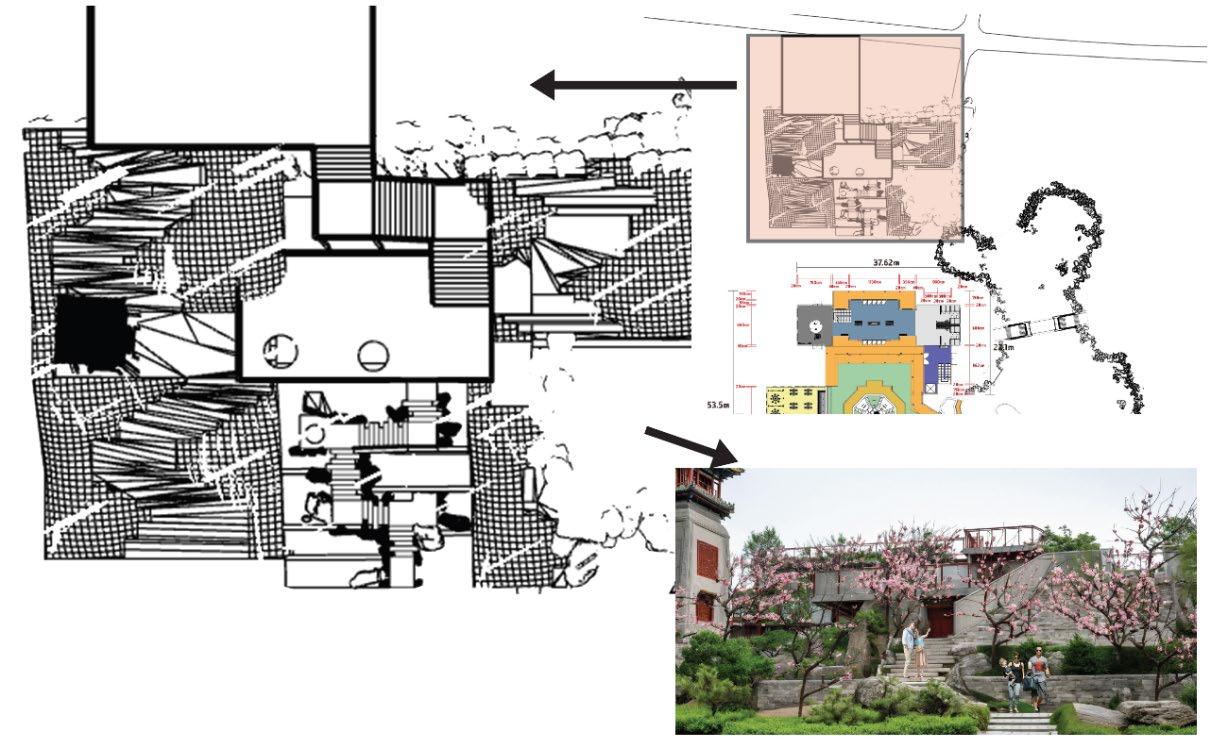

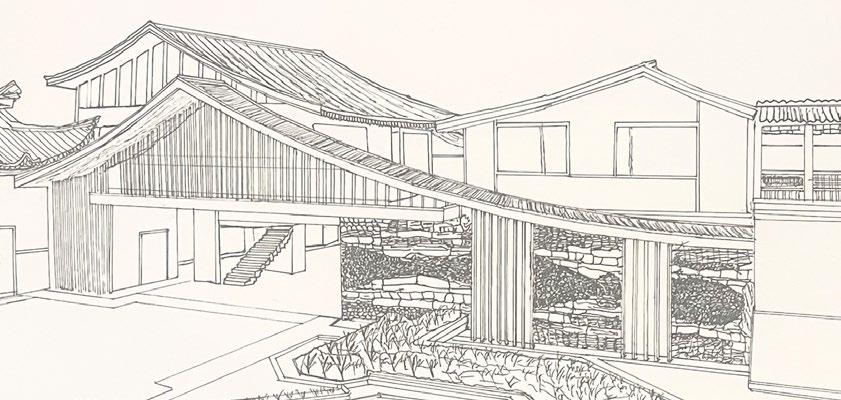

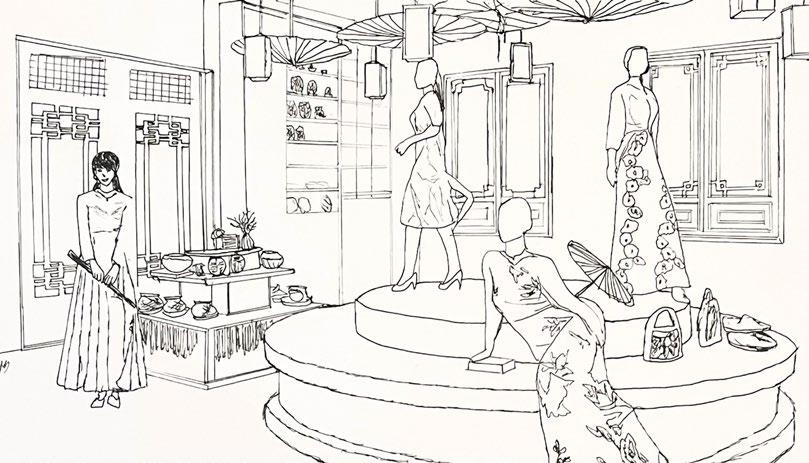

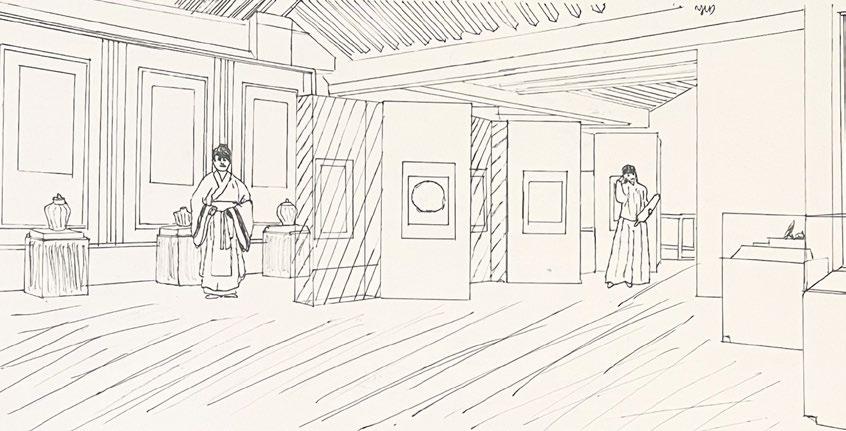

My second attempt is to design a Chinese-inspired garden and art gallery in the UK, exploring the balance between rules and creativity. A Chinese-inspired garden harmonizes traditional elements with modern needs, promoting cultural understanding. The Art gallery integrates Feng Shui principles with modern design to create a Chinese cultural hub in the UK.

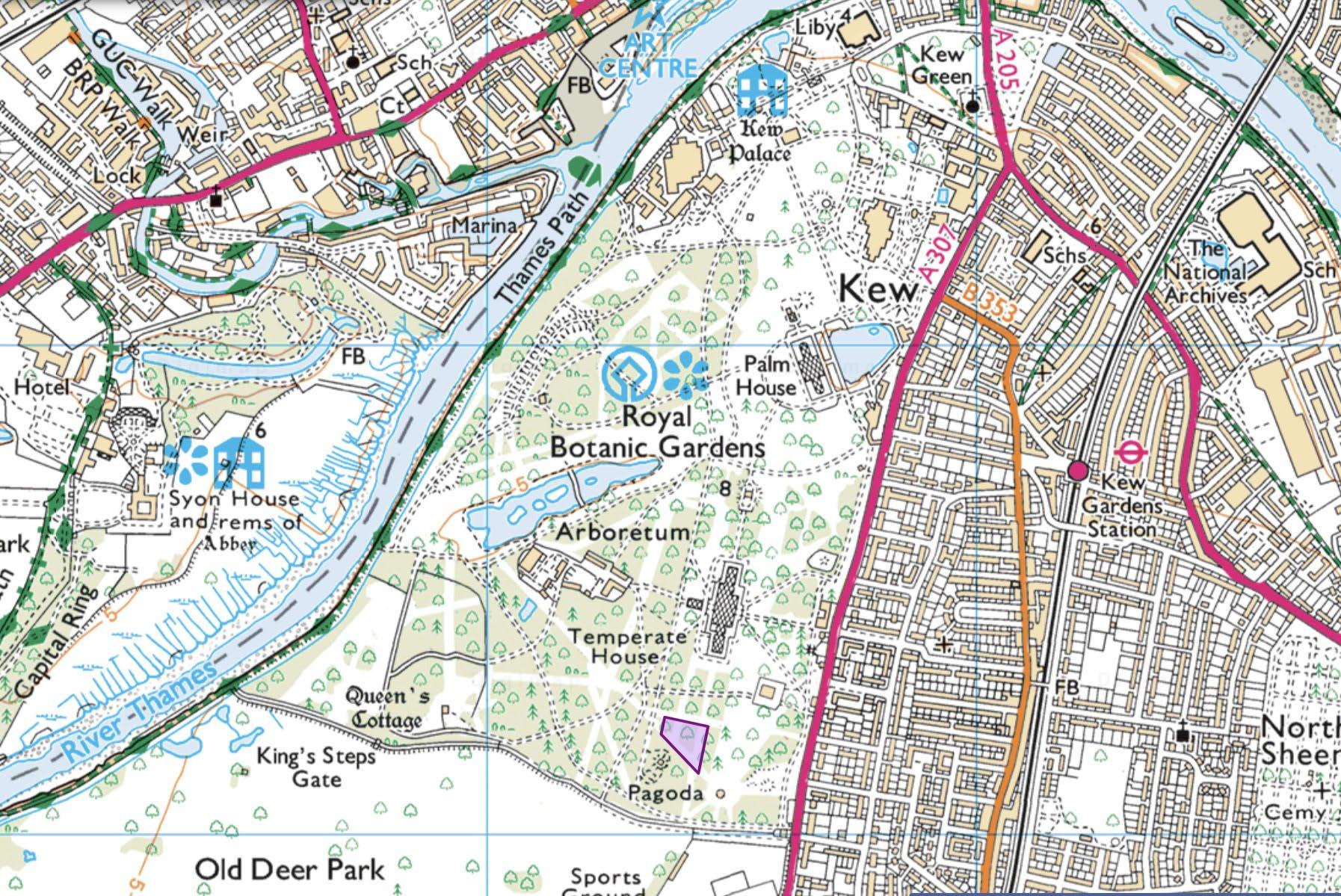

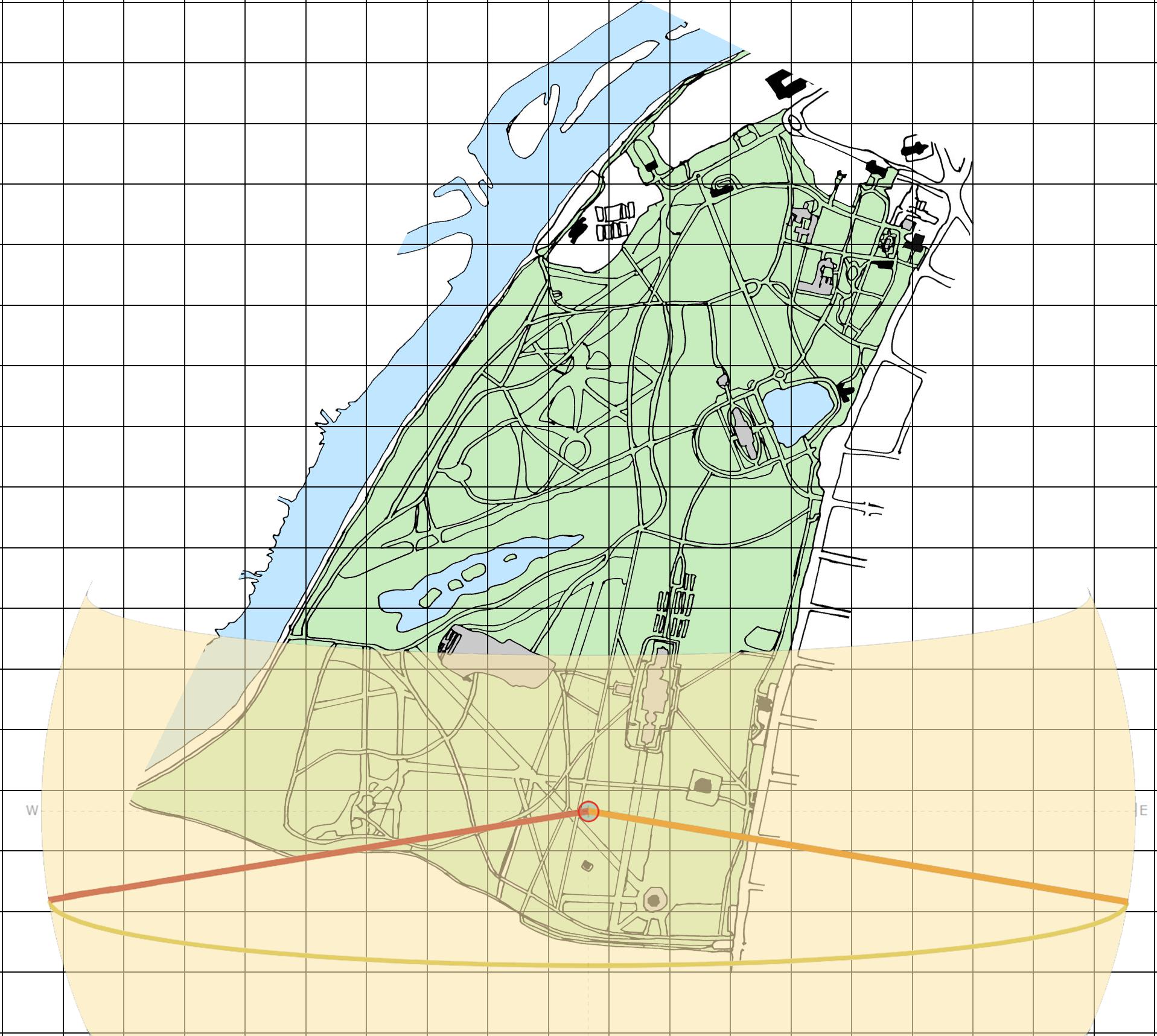

(1) Site Comparison: Evaluating Potential Locations

As the site for this project, I carefully evaluated three locations: "Kew Gardens (London)" (Figure 26), "Regent’s Park (London)" (Figure 27), and "Eastbridge Hospital (Canterbury)" (Figure 28). The comparison considered factors such as cultural relevance, environmental quality (sunlight, wind, botanical potential), and compatibility with Feng Shui principles.

Figure

Regent’s Park lacks Chinese context; it has no architectural or historical Chinese element presence. Regent’s Park is leisure-oriented, the functions primarily as a recreational park rather than a cultural site. So Regent’s Park is weak cultural justification, a new Chinese structure would feel disconnected from the park’s identity and history.

Eastbridge Hospital is dominated by medieval and Christian architectural elements, influenced by Gothic and Norman styles. It represents a strong religious identity, and its solemn spiritual setting is difficult to reconcile with Chinese garden principles, resulting in some cultural incompatibility issues. The contrast between Chinese architecture and the surrounding churches will create visual and symbolic dissonance, leading to architectural contextual conflicts.

Figure 26. Kew Gardens (London)

Figure 27. Regent’s Park (London)

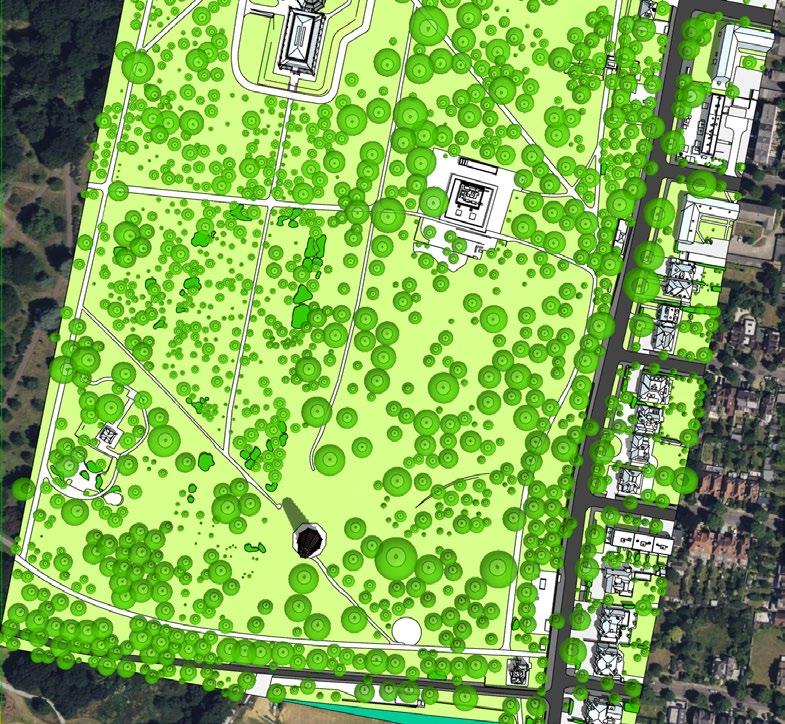

The Great Pagoda (Figure 29) in Kew Gardens, built in 1762, provides a direct visual and symbolic connection to Chinese influence in British history and becomes a cultural anchor. As a world-leading and excellent botanical garden, Kew Gardens provides an ideal setting for showcasing Chinese plants and seasonal symbolism. Kew Gardens' mission supports cultural learning and ecological awareness, aligning perfectly with the goals of my project in terms of educational coordination. Finally, Kew Gardens was selected for its strong historical resonance, botanical richness, and alignment with both ecological and cultural objectives. It offers the clearest opportunity for a meaningful architectural dialogue between imagined and authentic Chineseness.

(2) History of the Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens originated in the exotic garden of Lord Capel of Tewkesbury. Its development began in the 16th and 17th centuries, when Henry VII built Richmond Palace and moved his court to Kew during the summer. Kew Gardens is located along the banks of the River Thames. The entry of the royal family, nobles, and courtiers led to the rapid

Figure 28. Eastbridge Hospital (Canterbury)

Figure 29. The Great Pagoda in Kew Gardens.

development of Qiu Village. Frederick, Prince of Wales, rented the Kew farm in 1731. He redesigned and built the house, adding a white Palladian facade expansion on both sides, and earned the name "White House". Frederick and his wife, Princess Augusta, are both garden enthusiasts. They took on landscaping the area around the house with trees, large lawns, lakes with large islands, and the mound. Frederick passed away in 1751, and Princess Augusta continued to expand with the help of the Earl of Bute. Bute dreamed of having a garden containing all the plants known on Earth, and with the help of Princess Augusta, they founded the Botanic Gardens at Kew.

Richmond Gardens and Kew Gardens merged in 1802, and the "White House" was demolished. The botanist Banks initiated collection activities in South Africa, India, Abyssinia, China, and Australia, bringing back plants, including over 800 species of trees and shrubs. In 1840, Kew Gardens was established as a world-leading botanical garden and was adopted as the National Botanical Garden, with William Hook as its director. Under his leadership, buildings and structures were redeveloped, including the construction of palm houses, an increase in site to 75 acres, and an expansion of amusement parks or botanical gardens to 270 acres, later expanding to the current 300 acres.

Today, Kew Gardens is a leading plant research center, a professional gardener training center, and a tourist attraction. Its seed bank contains approximately 7 million specimens. The library and archives have over 500000 collections, including books, plant illustrations, photographs, letters, manuscripts, journals, and maps.

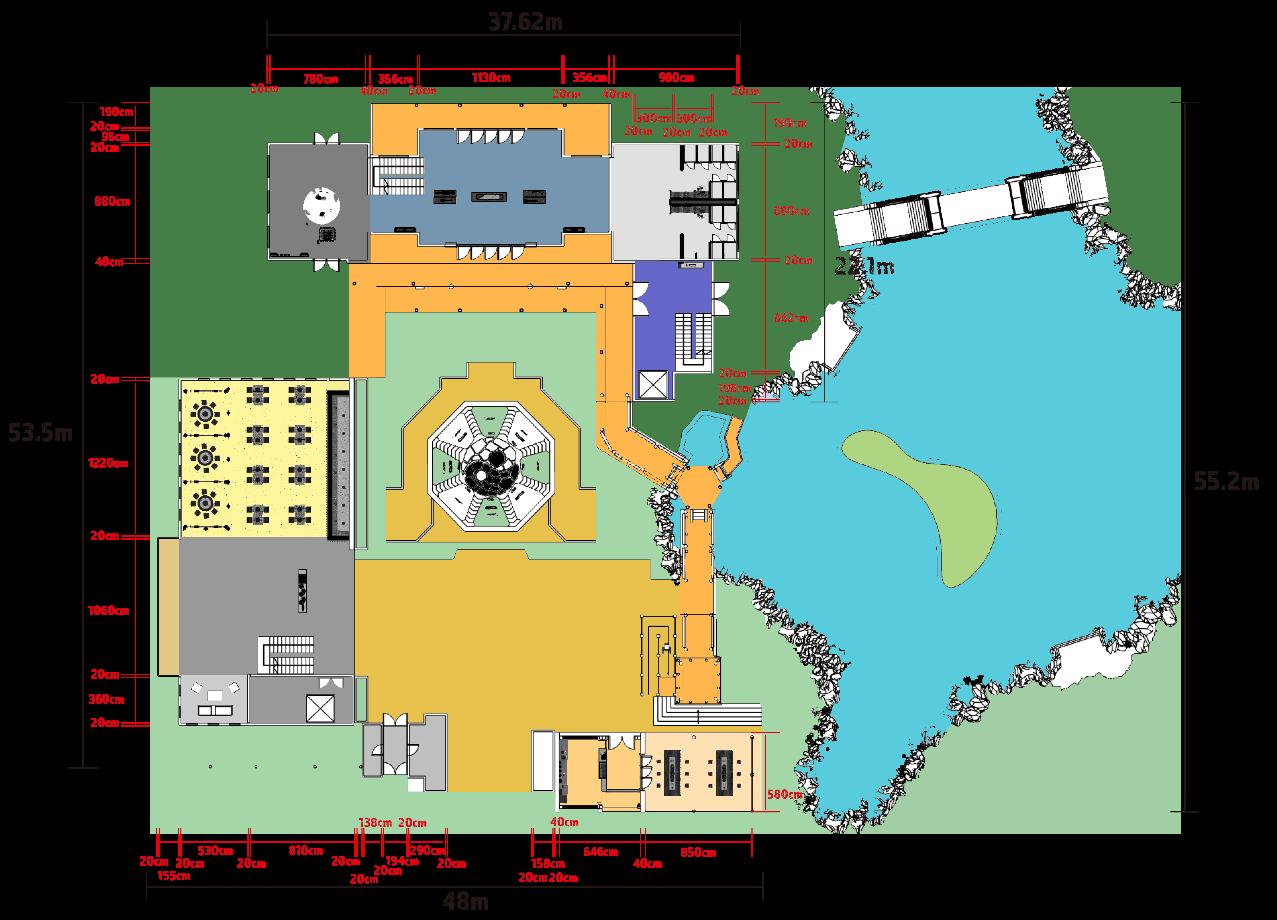

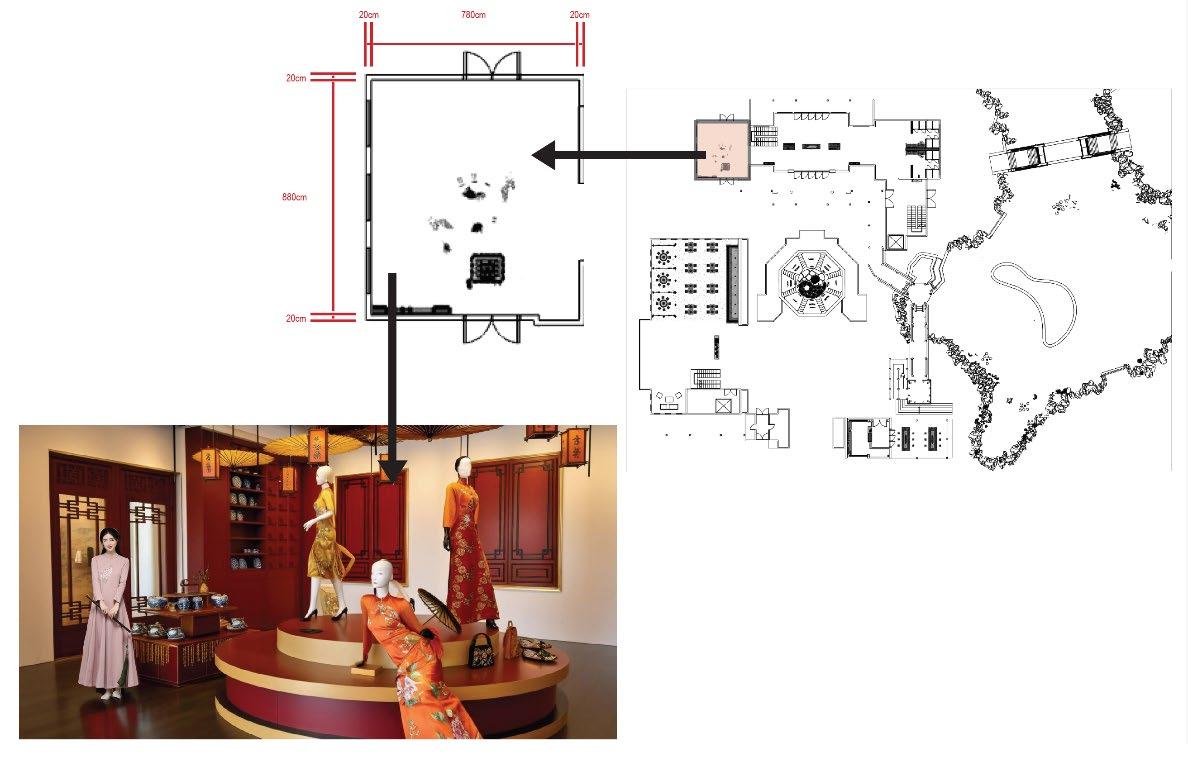

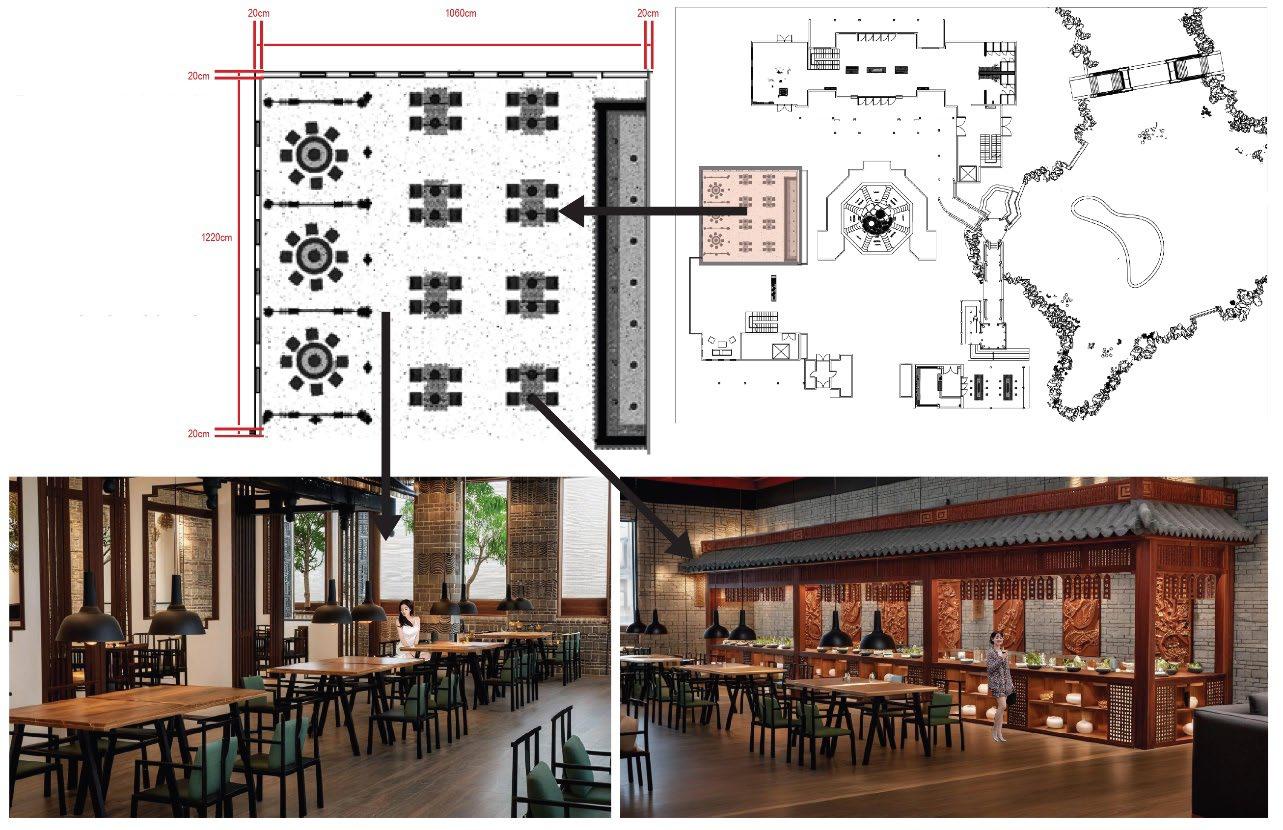

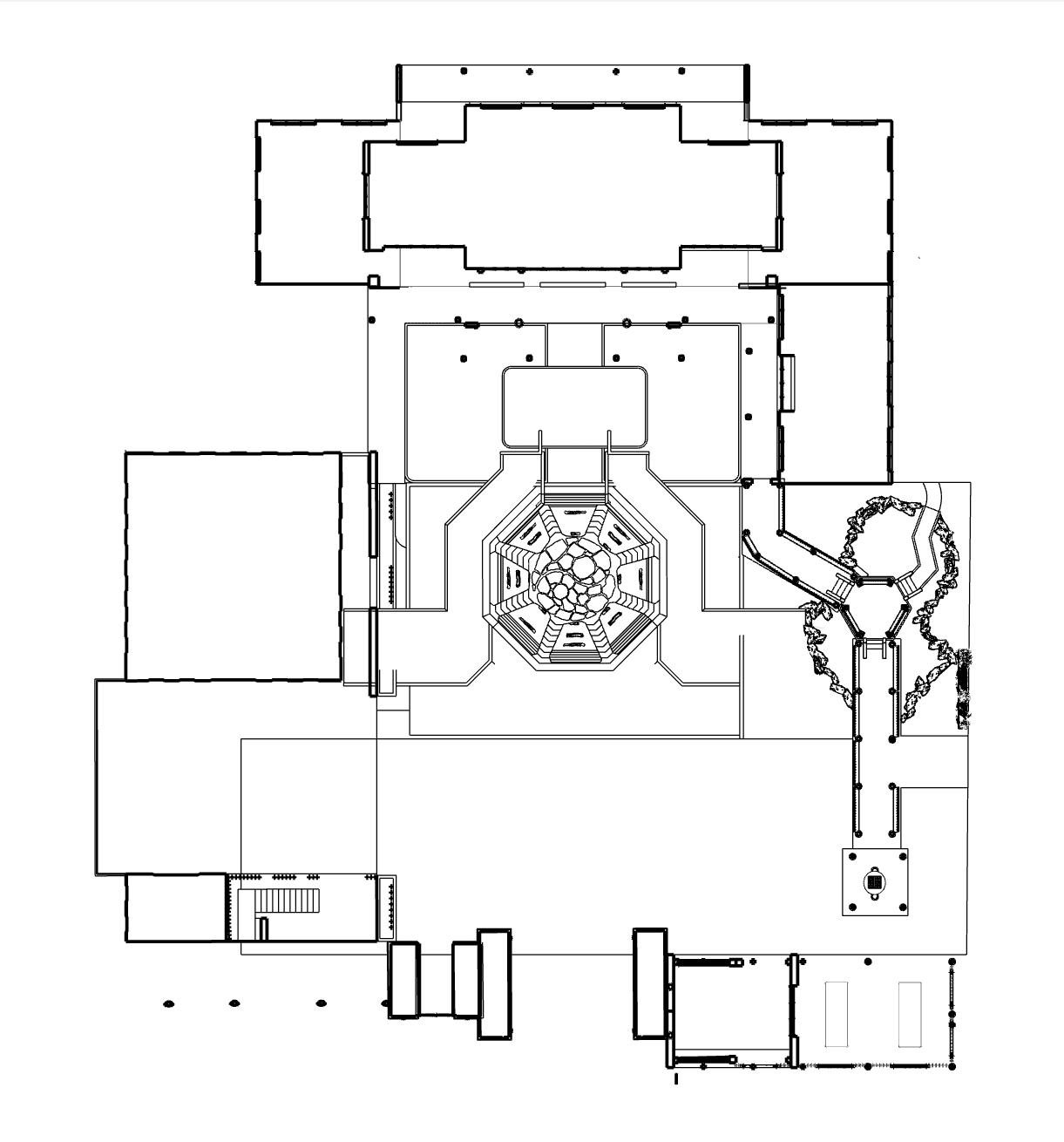

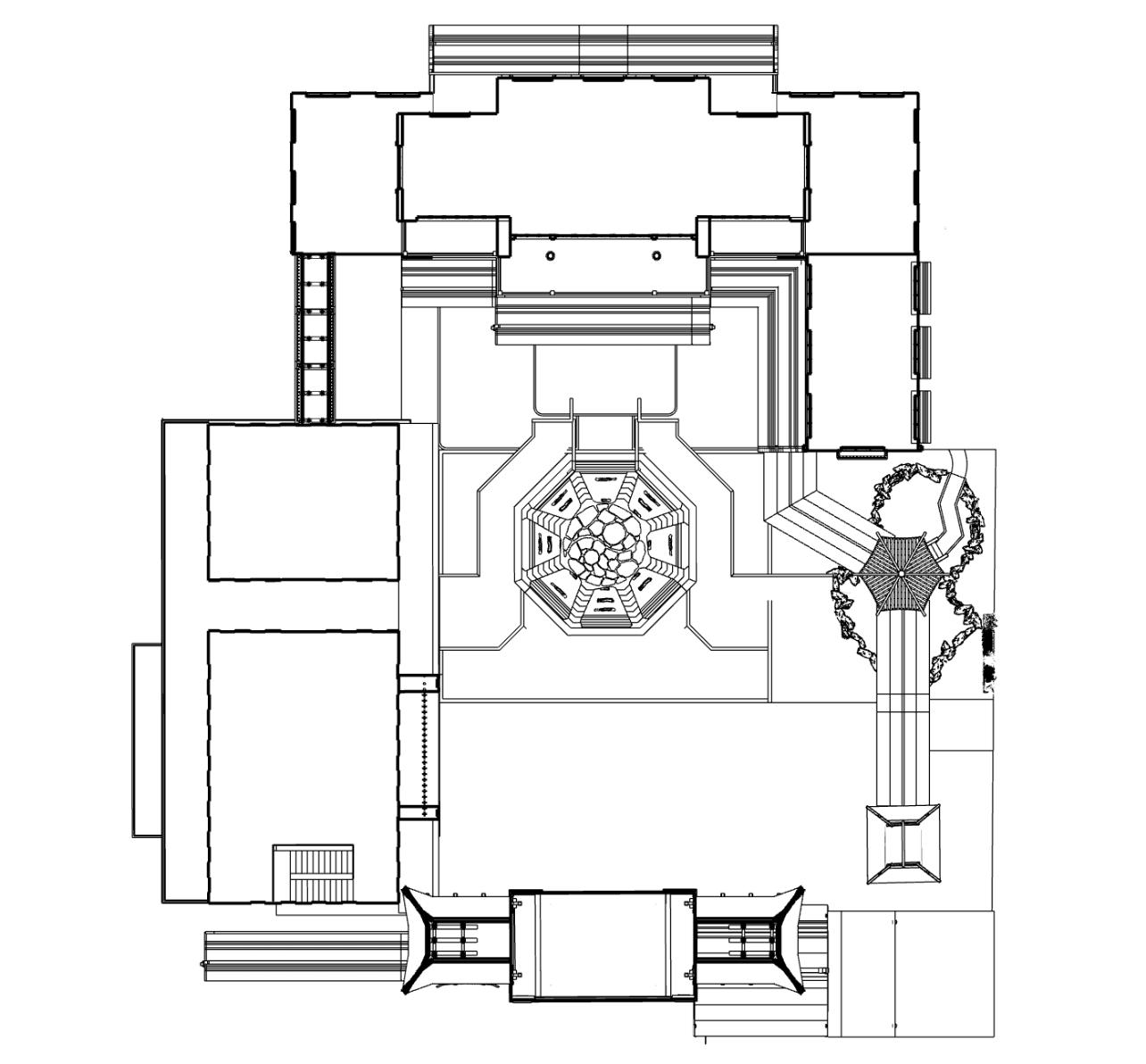

(3) Project Overview

The project combines Chinese architectural feng shui theory with ecological architecture concepts to construct a Chinese garden centered around a museum. The building materials used are sustainable, conveying the artistic and aesthetic beauty of Chinese gardens and the concept of sustainability to more people. The museum's exhibition area will showcase Chinese calligraphy, painting, carving, jade, porcelain, embroidery, clothing, architecture, and garden design, among other artistic works (Kerr, 1997), and hold courses on Chinese culture, calligraphy, painting, embroidery, and feng shui design.

The whole park will hold propaganda and experience activities of Chinese folk culture (such as the Chinese New Year dragon dance, lion dance, and Yuanxiao Festival lantern making), horticultural planting, urban gardening, environmental protection, and sustainability. Therefore, my partners include government agencies, urban horticulturists and botanists, artists and art institutions, educational institutions, community organizations, media, suppliers, sponsors, and donors. The main sources of funding are government agencies, sponsors, and donors. We conduct marketing and promotion through online and offline channels, including media, community networks, and educational networks. We manage customer relationships through the following methods. Personnel service of the tourist service center, organizing learning activities and educational seminars to establish

study groups, designing projects and experiential activities for the local community to enhance community participation, providing digital interaction for online virtual reality visits, and establishing a membership system.

This project can promote sustainable concepts, raise people's awareness of environmental protection, introduce Chinese culture, art, and philosophical ideas, establish relevant learning communities and courses, unite the centripetal force of the community, help the local economy, and make positive and good contributions to society. After the evaluation of cost structure and revenue streams, it is indeed feasible and profitable.

4. Design Practice

In this section, I will renovate the "Beaney House of Art and Knowledge" and design a Chinese-inspired garden and art gallery in Kew Gardens to explore the experimental practice of Feng Shui theory, and connect it with environmental psychology, urban gardens, and sustainability.

4.1. Renovate Beaney House of Art and Knowledge

4.1.1

Analysis of Improvement Areas for Beaney House of Art and Knowledge

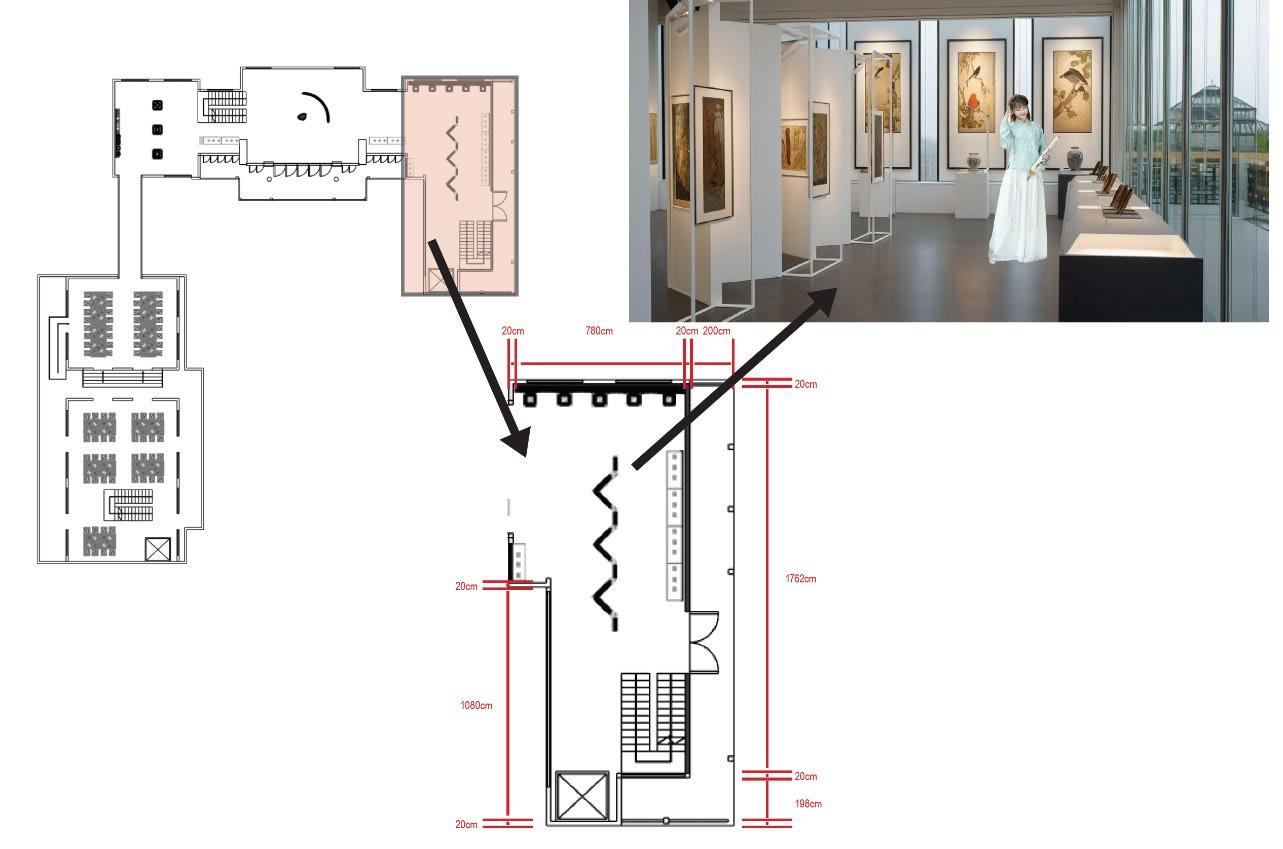

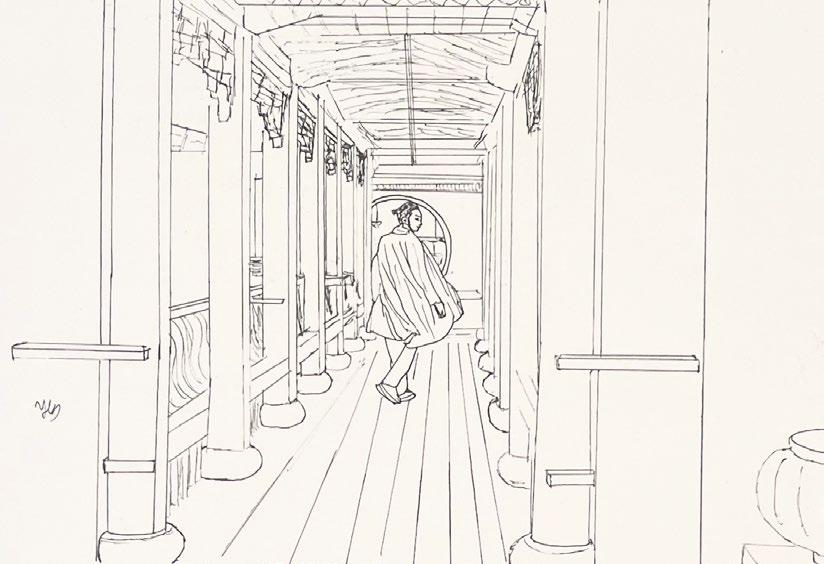

People enter from the public entrance of the existing 19th-century facade of Beaney House of Art and Knowledge facing the High Street, the reception area is located at the focal point of the entrance, opposite a glass curtain wall elevator shaft and open staircase. The reception area serves as a pin interlocking that combines old and new building designs, bringing design coherence. The space of the library has doubled compared to before, and a temporary gallery and related educational space have been built near the original gallery. All exhibition spaces provide good professional lighting and environmental control to meet international standards.

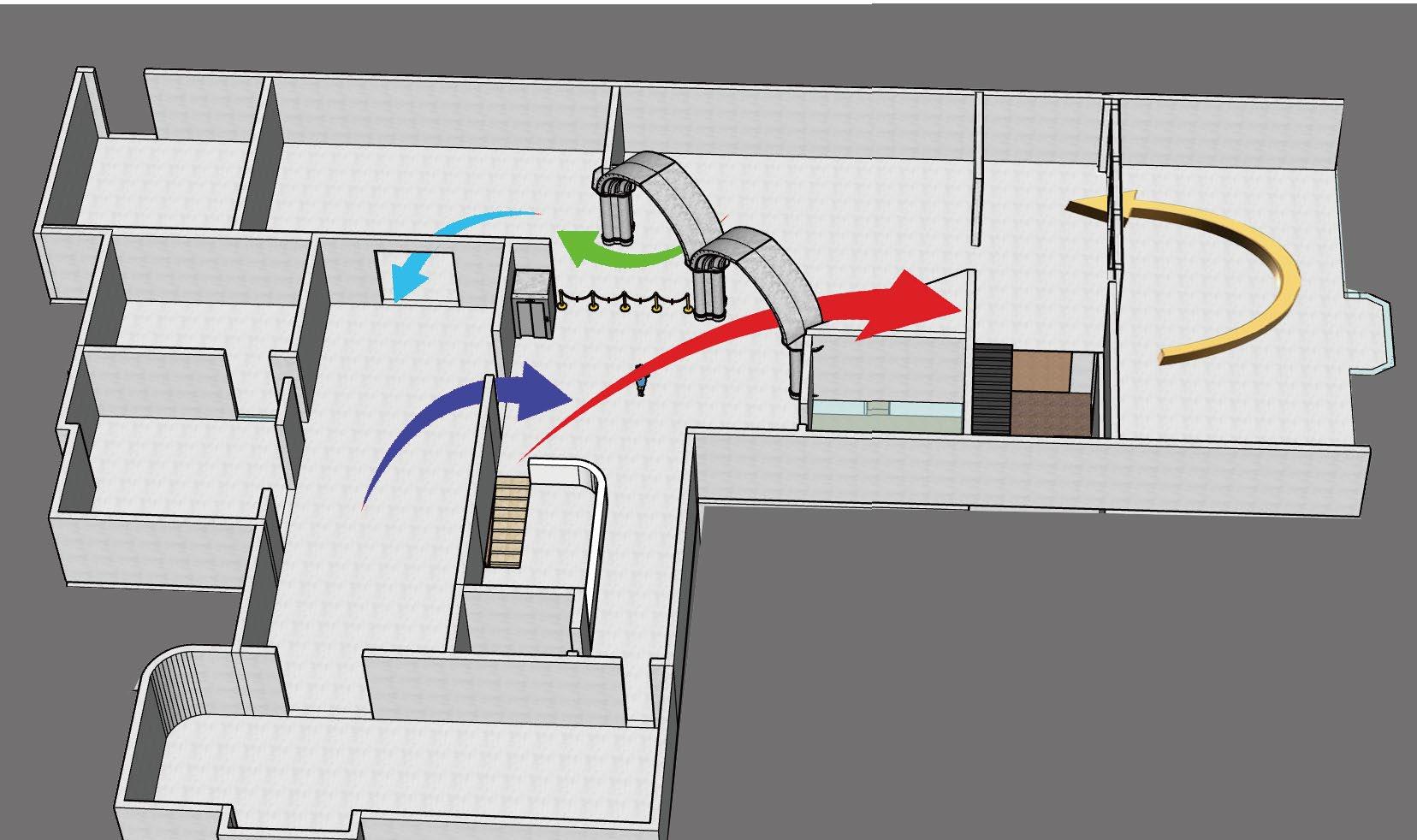

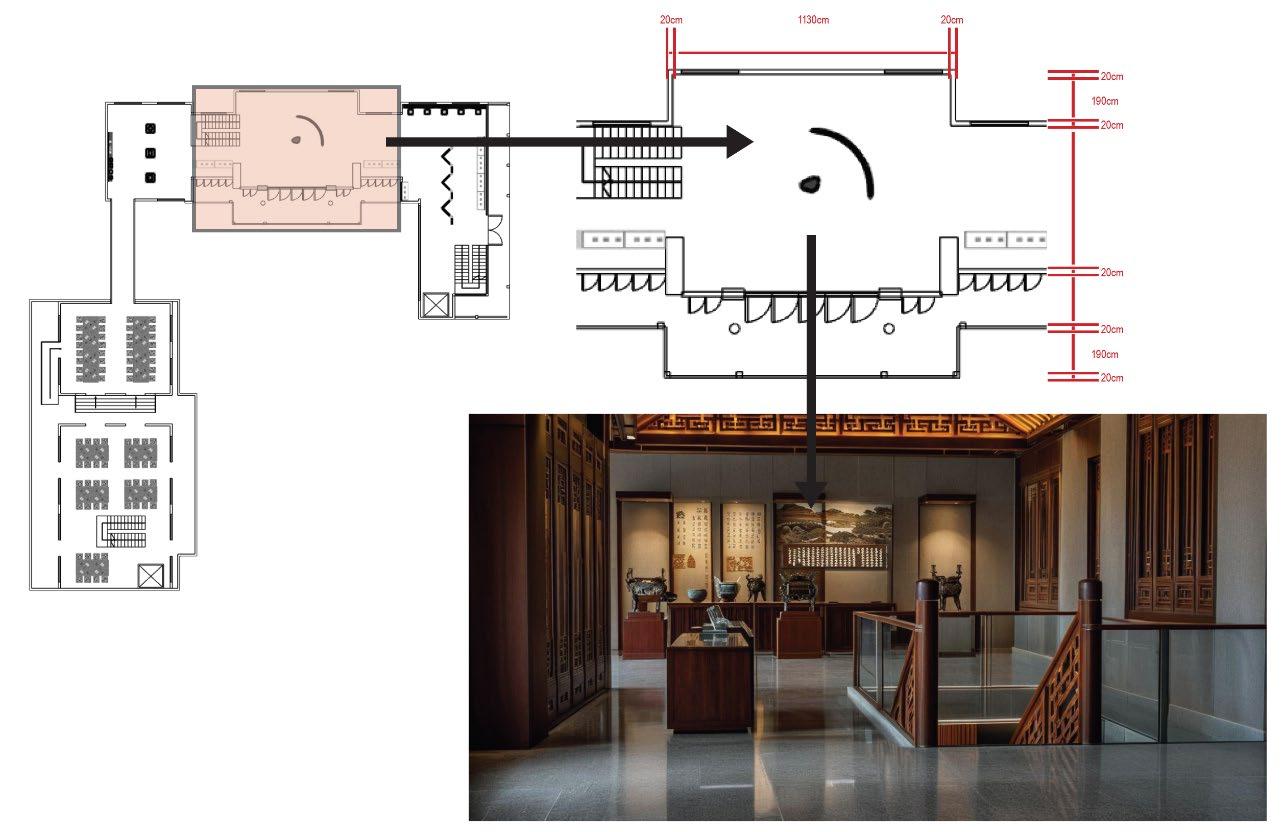

The on-site terrazzo and wood mosaic flooring, colored glass screens, ceilings, stairs, railings, and frequently renovated finishes inside enhance the safety of museum and art gallery spaces. The ceramic tiles in the public atrium space, solid oak flooring in the gallery space, and rubber sound-absorbing flooring in the library space all make the entire building more perfect. So, it was difficult for me to find areas for improvement in the architectural design of Beaney House of Art and Knowledge, until I noticed that the exhibition hall on the first floor (Figure 30) appeared smaller in the crowded visitor crowd, and the move flow design was not smooth enough. Therefore, making the exhibition hall more open, providing visitors with a better view, and having a smoother move flow became my entry point.

Figure 30. The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge first floor plan

4.1.2 Thoughts on Design Architectural design thoughts and outcome

(1) Navigation Challenges

The original layout of The Beaney posed significant challenges for visitors. The interconnected rooms, ambiguous pathways, and the overwhelming number of possible routes often led to confusion and disorientation. Visitors didn’t have a clear sense of where to go, which disrupted their ability to fully engage with the exhibitions.

To address this, I analyzed the existing floor plan, identifying areas where walls and doors created unnecessary complexity. I proposed a new layout that simplifies the spatial flow. By removing these barriers, I introduced a clear circulation route that guides visitors from the entry point, through the exhibitions in a cohesive loop, and back to the exit seamlessly. This reimagined design enhances accessibility and ensures a more intuitive visitor journey.

(2) The Arch Design

One of the key features of my redesign is the addition of navigation-enhancing arches. Initially, I explored using a Gothic-style arch to align with The Beaney’s Victorian Gothic architecture. This was intended to harmonize with the existing interiors. However, during the process, I realized that this approach blended too closely with the original structure and was similar to the original design. It failed to serve as a distinct navigational marker that would stand out for visitors.

In response, I shifted to a modern arch design. This new design introduces clean, contemporary lines that provide the necessary contrast to the existing elements while maintaining a subtle connection to the building’s historical context. The arches are designed not just as functional elements but also as aesthetic features that guide visitors through the space. These arches include placeholders for stained glass panels, inspired by Canterbury’s local architecture, to further enhance their cultural resonance

(3) Incorporating Canterbury’s Heritage

To deepen the connection with Canterbury’s identity, I incorporated elements from The Canterbury Tales into the stained glass panels. Each arch includes six panels on one side, and with two arches in total, there are 24 panels, each representing one of Chaucer’s tales. These panels serve as a storytelling medium, transforming the arch into a bridge between history and modernity.

The stained-glass panels are backlit with integrated lighting, allowing vibrant colors to illuminate the space. This not only adds visual appeal but also enhances the narrative experience for visitors, creating a dynamic interplay between light, color, and storytelling. By combining a modern arch structure with traditional stained glass elements, the design strikes a balance between functionality and cultural significance.

(4) Application of Feng Shui Theory

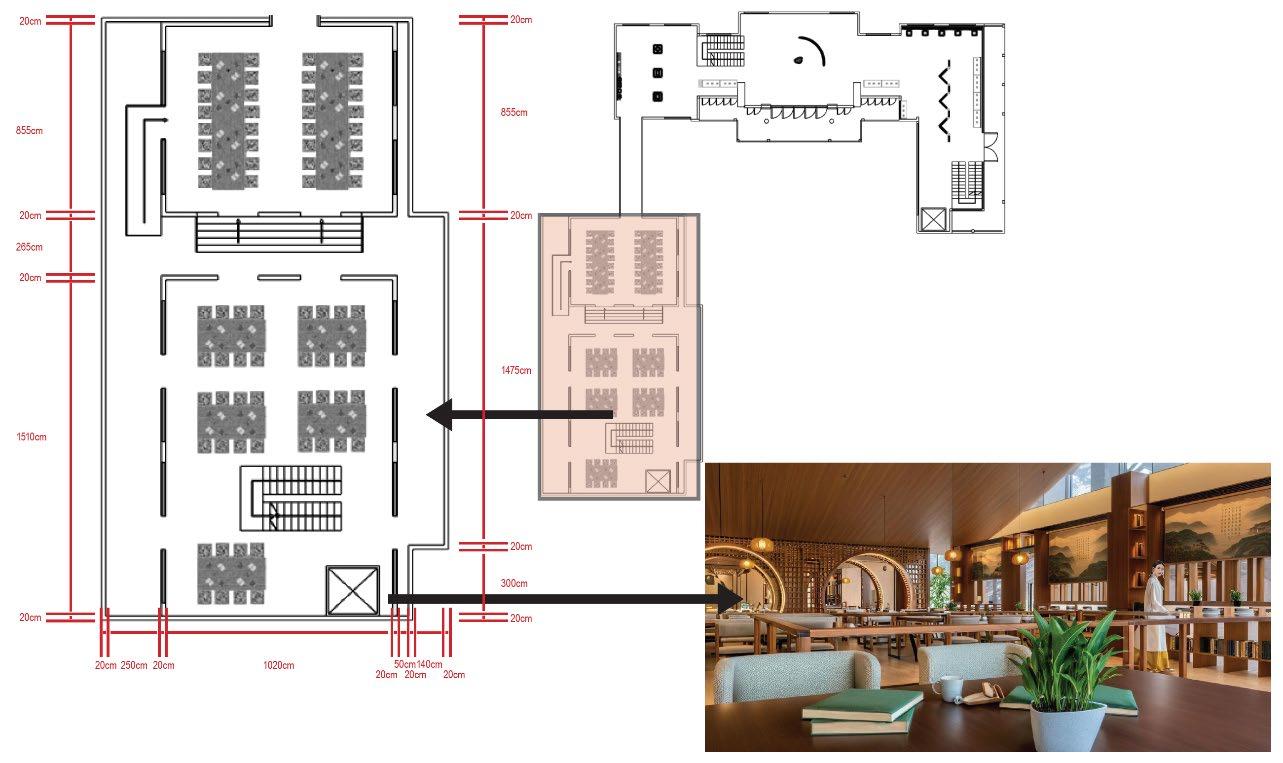

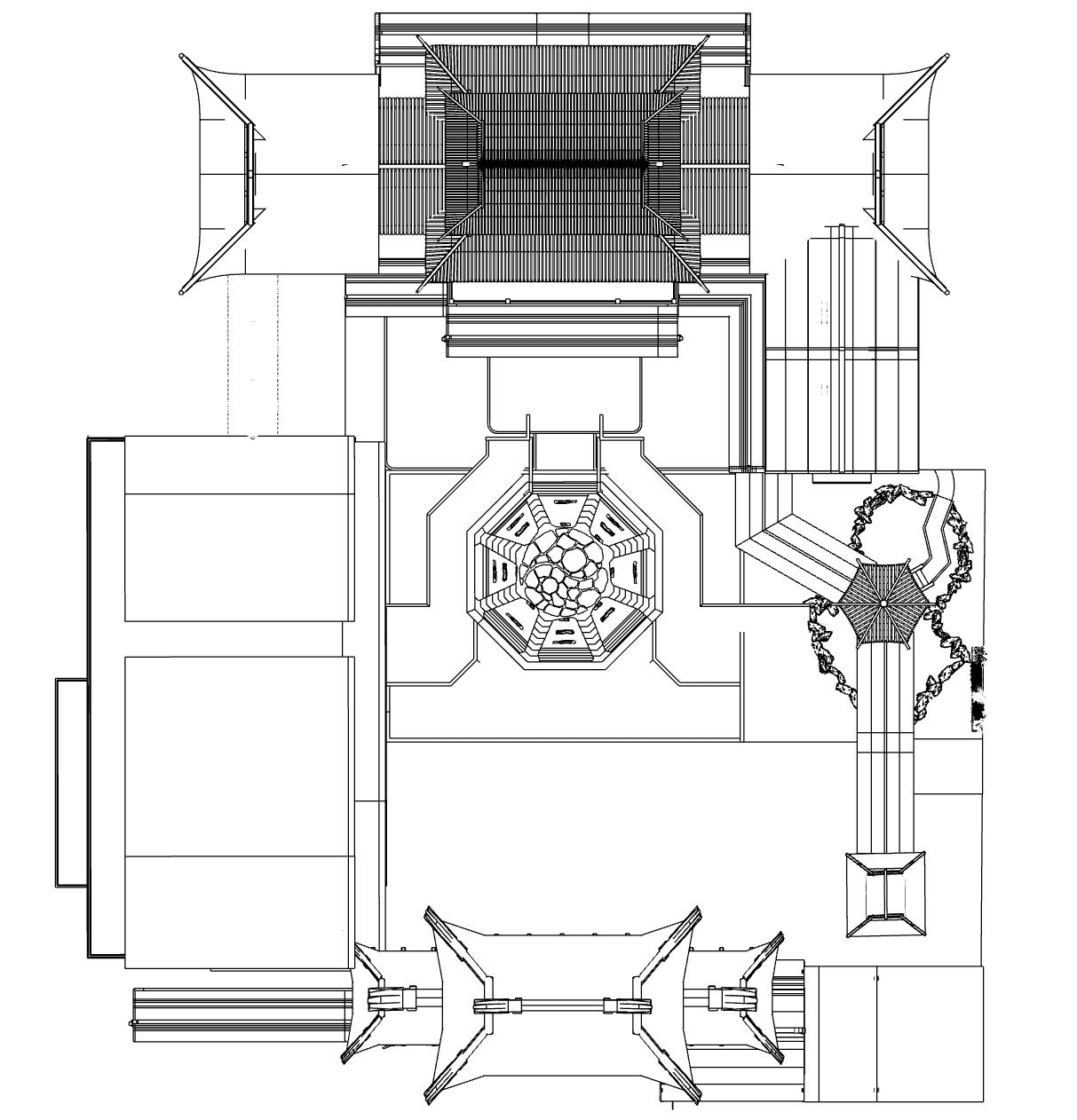

The plan and Stereoscopic drawing of the first-floor renovation are shown as Figure 31

and Figure 32. My method to renovate Beaney House of Art and Knowledge based on Feng Shui theory is as follows.

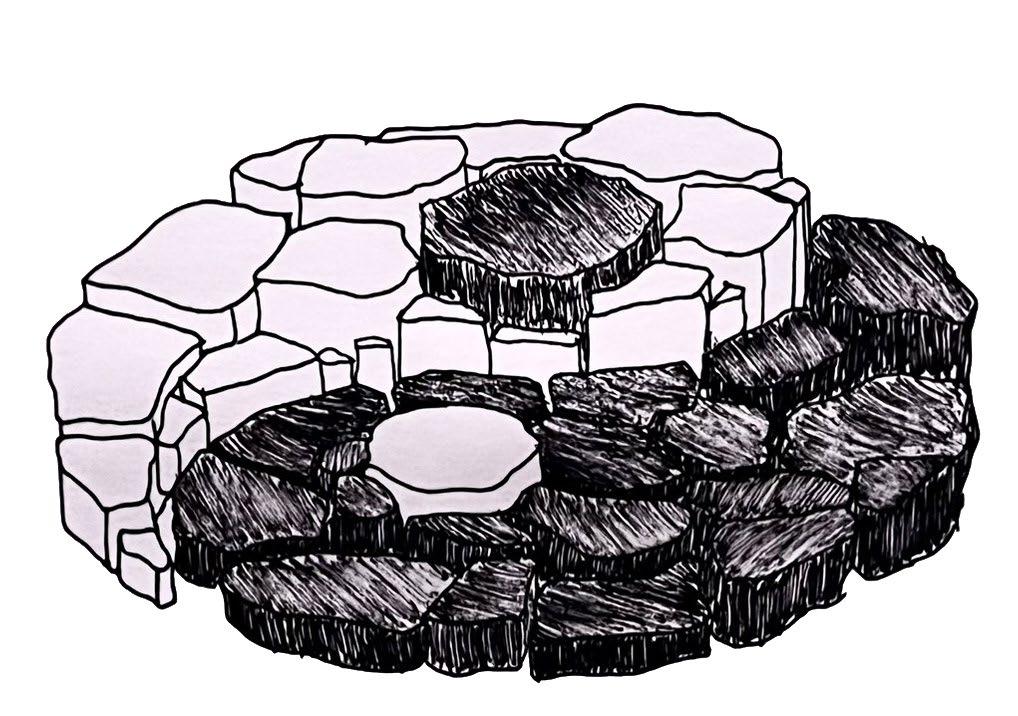

(i) Using the method of Five Elements Creation, the flowing energy of water element is created through the elements of gold, wood, fire, and earth. My design idea is to demolish the partition wall on the first floor and create a double

Figure 31. Plan of the first-floor renovation

Figure 32. Stereoscopic drawing of the first-floor renovation

arch to guide people in and out, making the flow of people like water and making the route planning more reasonable. In Chinese feng shui theory, the five basic elements of metal, wood, water, fire, and earth (or soil) can mutually stimulate or generate each other. I want to design an arch with the four elements of metal, wood, fire, and earth to stimulate the flow characteristics of water elements so that the flow of people is like the flow of water, smooth, unobstructed, fast, and beautiful. So in addition to using stone (earth element) and wood (wood element) for the columns in the design of the arch, I hope to add stained glass because the basic materials of glass is the sand, soda ash, and limestone (earth element) mixed in a certain proportion, then various additives such as aluminum, lithium, magnesium, potassium (gold element), etc. will also be added. The mixed raw materials are heated to a very high temperature (fire element), usually reaching 1300 ° C to 1500 ° C for firing. Therefore, glass has the characteristics of three elements: gold, earth, and fire. The entire arch and stained-glass combine the four elements of gold, wood, fire, and earth. According to Feng Shui theory, they can drive and create the water elements, thereby generating a flowing energy that allows visitors to receive the propulsion of flowing energy and move more orderly and smoothly.

(ii) Adopting a counterclockwise movement design to obtain stable and orderly energy. I adopt a counterclockwise design for the entrance and exit direction of the arch and the entire movement line. According to Feng Shui theory, energy moving counterclockwise can make people feel more comfortable and their minds clearer. In environmental psychology, most people have a habit of moving counterclockwise, which is a historical and cultural imprint formed by people's activities or running on the sports field. Most people's hearts are on the left side, resulting in a slightly heavier body weight on the left side, which is suitable as the axis (center of gravity) for rotation. In addition, most people's right foot

Figure 33. The arch design based on Feng Shui theory.

has more strength and is suitable as a pushing role for changing direction when moving, so they are more accustomed to moving in a counterclockwise direction.

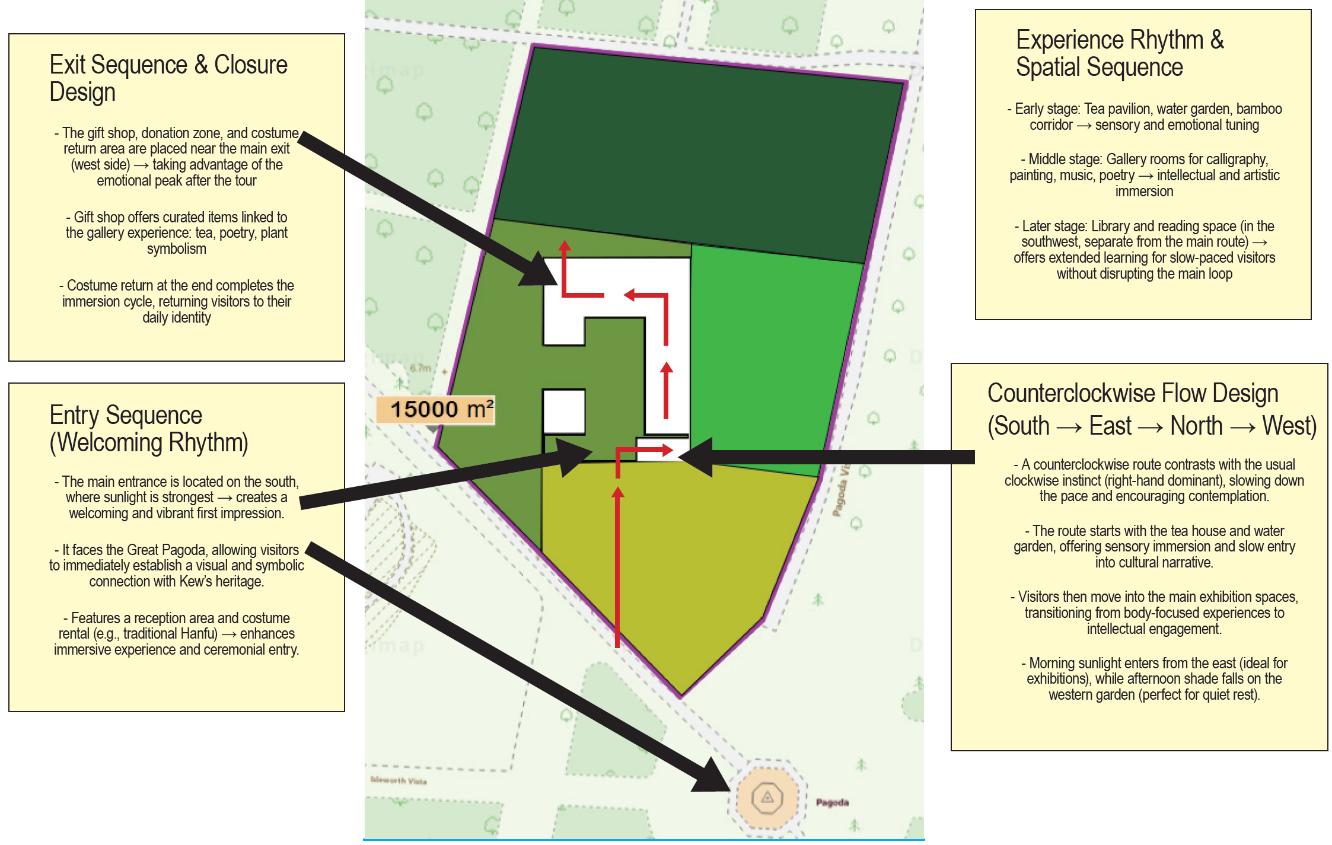

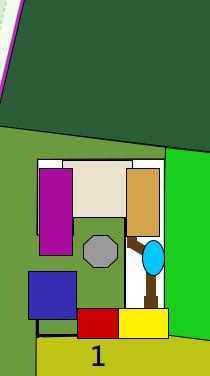

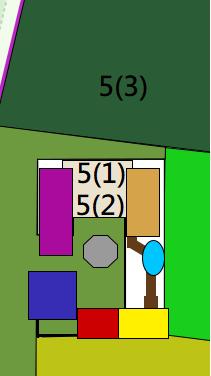

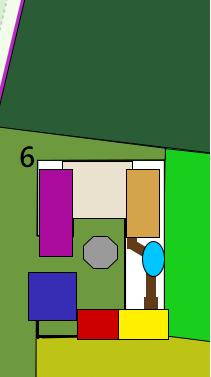

4.2. Design a Chinese-inspired garden in Kew Gardens

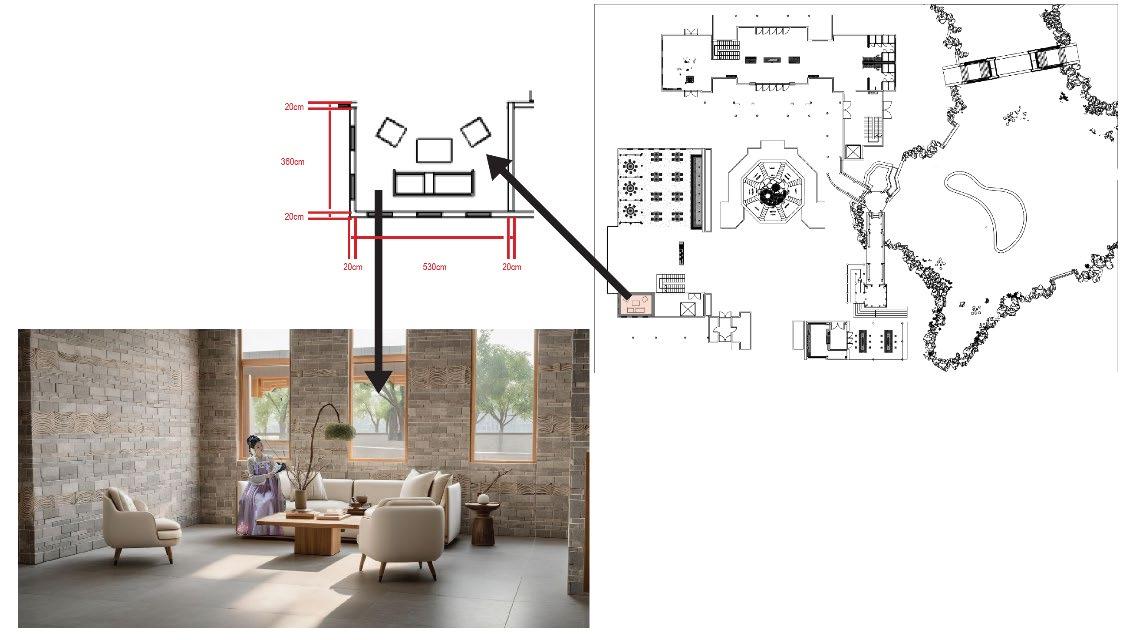

4.2.1 Thoughts on the Kew Gardens Project

Before starting this design project, I first thought about and explored the answers to the following questions

Q1: Why Kew Gardens?

Choosing Kew Gardens is based on four reasons.

(1) Occupying a strategic location: Kew Gardens' convenient access, either overground or underground. Over 2 million annual visitors, located in the Greater London area with high visibility.

(2) High cultural and historical value: Kew Gardens is a UNESCO World Heritage site with iconic architecture and Chinese-style architecture that can engage in dialogue between Chinoiserie and authentic Chinese architectural design.

(3) Environmental opportunity: Kew Gardens has a flat terrain suitable for traditional

Figure 34. The counterclockwise movement line is based on Feng Shui theory.

Figure 35 Models of (a) the arch and (b) the renovation of the first floor.

courtyards and new structures. It has over 50000 plants, making it a suitable location for Chinese-style garden architecture.

(4) Great potential for cultural integration: Kew Gardens has strong British-Chinese historical ties (via the Great Pagoda), making it an ideal site for applying feng shui principles to showcase Chinese gardens and culture.

Q2: Why does London need this project?

London needs this project because “This is more than a building it is London’s response to culture, nature, and its evolving identity”. There are four reasons for segmentation.

(1) Cultural and urban necessity: This project can fill a cultural gap and strengthen multicultural identity. London, despite being multicultural, lacks public spaces that reflect authentic Chinese architectural and garden philosophy. This project can fill the cultural gap and address this absence. This project includes a Chinese garden and museum, where the gallery and exhibition halls can serve as places for engagement, participation, and cultural expression, aligned with London’s ethos of inclusion and cross-cultural dialogue, strengthening multicultural identity.

(2) Enhancing global cultural role: This project can reinforce London as a global cultural capital and boost cultural tourism. The design and establishment of the Chinese garden and museum demonstrate the city’s willingness to embrace and translate nonWestern cultural forms into its built environment. It can reinforce London as a global cultural capital. A destination that combines contemporary design, sustainability, and cultural depth can appeal to global architecture and culture-focused visitors, boosting cultural tourism.