INNER SYDNEY HIGH SCHOOL DESIGN PROPOSAL

A series of informed formulaic guidelines that will provide the framework for our design.

A user-centric design approach

Establishing the needs of the school community through direct engagement in the concept + design development phases

Achieved through:

Survey of current high school students and teachers via online forms and interviews

Commitment to engage with these groups throughout the design development phase

Spaces that are both dynamic and flexible, and able to accommodate a range of pedagogy as they emerge and evolve

Future-conscious design that allows for ease of addition and re-appropriation of space to suit changing needs and programs

Achieved through:

Analysis of flexible architecture through precedent studies

Employment of a pre-constructed timber structural system and provision of a grid-defined framework

Responding to the site’s past, present and future, and understanding the impact of all interventions on it

Establishing a sympathetic and respectful relationship between the existing context and the new building

Offering a valuable asset that engages with the needs of the local and school community

A sustainable approach to design that is sensitive to both community and environment

Achieved through:

In-depth site analysis

Survey of local community members via online forms and interviews

Employment of sustainable construction and building systems

Woven throughout every aspect of our approach, these three disparate elements ultimately converge at one unifying point: Sustainability.

The end goal:

A long-lasting, high-performance building

A building which creates a sustainable positive impact on the community

Understanding the catchment area

When designing a school, it is essential to first consider the demographics of the attendees in order to understand their needs. The placement of this school is a response to the lack of public secondary schools serving the Inner City / Inner East area. This was advocated by residents as existing schools were reaching capacity, and it was difficult to travel long distances to attend them. The following graphs demonstrate that students attending will be from a large range of socio-economic backgrounds; an example of this is the average family income ranging from $2307 a week to $3806 a week. This income statistic trends upwards the further you move East. This pattern is also present in statistics such as internet access and Government vs Independent Schooling.

With this, comes a multitude of religious, cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Buddhism was practiced more commonly in the CBD, with 22.2% in the Sydney/Haymarket/The Rocks statistical area. Catholicism and Anglicanism remained consistent amongst all areas, ranging from approximately 12.120.6% and 4.6-16.5% respectively. Judaism becomes common moving further East, the highest being 11.2% in Double Bay. Languages spoken at home ranged greatly. Further West, it is significantly less common for English to be spoken at home, with only 25.1% in Sydney/Haymarket/The Rocks. The main languages spoken instead on this side of the catchment area are Mandarin, Cantonese, Indonesian and Thai. In the East, the main alternate languages are Greek, French and Italian. Spanish remained consistent throughout.

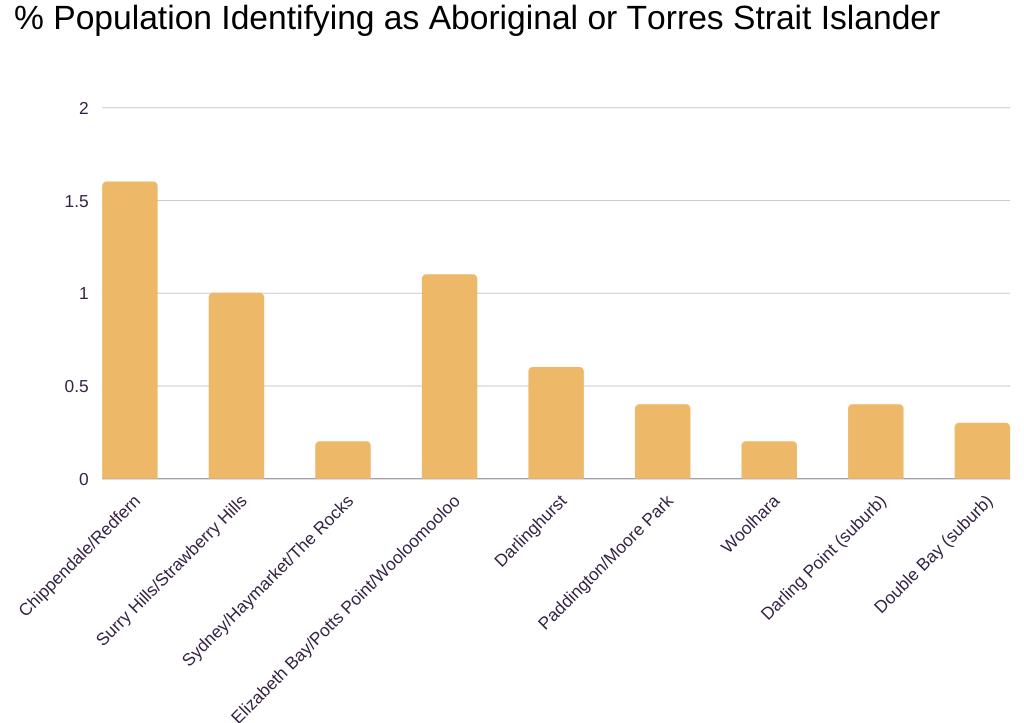

It is also crucial to address the rich Indigenous history of Redfern and surrounds. The Chippendale/Redfern and Elizabeth Bay/Pots Points/ Wooloomooloo statistical areas have a significantly higher percentage of First Nations residents compared to the rest of the catchment. The railyards and warehouses once provided income for many working class families, however, as this area became more gentrified, many social housing complexes were demolished and the once thriving Indigenous community was displaced.

The site itself is in Surry Hills, which has a range of residential, commercial and light industrial areas. There is a rich nightlife, but also many residents who reside mainly in Victorian terrace houses. Their common transport habits are listed in the third graph.

*Areas are defined by 2016 Census Statistical Area Level 2, except Darling Point and Double Bay, which are defined as suburbs because these areas are split by the catchment area border

Community identity

Along with private developments, our site is part of the Greater Sydney Commission’s “A Metropolis of Three Cities” development plan (Greater Sydney Commission, 2017). This is a holistic approach to the future planning of Sydney, looking towards 2056. The plan is split into Infrastructure & Collaboration, Livability, Productivity, Sustainability, Structure Plan, and Implementation. The developments outlined in this plan will contribute to the predicted future growth of the catchment suburbs of our site. They will also improve the public fabric of the surrounding areas, particularly in relation to Central Station. Many of the proposed private developments are for mixed-use skyscrapers, with a large percentage of housing. This will increase the population in the catchment area dramatically, and alter the demographics of the community. Thus, it will be important for our design to be adaptable to any future changes, and to have a positive impact on a community which is constantly working to improve itself.

As part of our initial research, we interviewed eight people who lived in the local neighbourhood (Redfern, Darlington, Surry Hills) to understand the identity and values of the community, and how we can positively contribute to this. This was undertaken on Zoom due to the lockdown restrictions.

Link: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

Location

The Inner-city location is close to public transport and cycling routes so it is easy to travel to work, and it is generally not essential to own a car. As most resources and forms of entertainment such as bars, galleries, restaurants, libraries and sports fields are close-by, the streetscape is very activated from pedestrian activity.

Architecture / Urban Design

The leafy terraced streets and lack of traffic were mentioned by all as a contributor to their decision to live in this area. This urban character is quieter and does give the sense of living near the CBD, despite the proximity. Many of these suburbs have a localised main strip of shops, which was desired by all interviewees as it establishes a connection with their immediate community. The narrow streets and terrace balconies allow for visual connection with neighbours, further contributing to this. Other features mentioned were small green spaces on street corners, markets, community gardens and murals by local artists. Many spoke of the terrace typology as beautiful and historic, signifying the area’s high density working class origins. Residents were willing to sacrifice high rent and less space for these reasons.

History

It was important for all interviewees to engage with the history of the area in which they live. They recognised Redfern as a significant area for Sydney’s indigenous history. Redfern is often referred to as the “Black capital of Australia” (Korff, 2018). Redfern was the location of Australia’s first Indigenousrun legal, children’s, and health services. Locations such as The Block, The Settlement, and the numerous murals painted by Indigenous artists were recognised as important spaces for First Nations community.

Despite acknowledging the importance and inevitability of vertical buildings serving high density areas, there was a universal dislike of many of the nearby new developments. Interviewees referenced the sterility of the apartments near Redfern station, as they lack consideration for aesthetics and scale relative to their context. They also expressed a sadness regarding the destruction of historical buildings, which are characteristic of the working class history of the area. Two people mentioned the adaptive-reuse of warehouse spaces as positive architectural strategy. Respondents did not oppose to the idea of a new school, it is a necessary resource in such a high density area, and contributes towards “public good”. They understood that tall buildings are a necessary solution looking into the future of inner-city areas, but they need to respond sensitively to context.

Immediate site context

Prince Alfred Park was considered an important green space that contributed positively to the community. Subjects visited the park often, and utilise the cycling route, basketball courts, outdoor gym and pool. We discussed how a school in this location could contribute to the wider community. Suggestions included spaces like a hall, library, theatre, community garden or sports facilities that could be accessible by community groups outside of school hours.

Site constraints and opportunities

A drawback of the site is that the shortest edge is oriented towards the North. With the intent of utilizing passive thermal design for comfort, light and ventilation, our design approach should aim to maximize exposure to the ideal northern aspect and bring light and warmth through to the southern end of the site, whilst protecting the northern and western edges from the sun during summer, particularly in the afternoons. An exploration of materials and strategies we may use to achieve this (e.g. EFTE cladding, operable louvres, curtains or screens to block sun etc.) are explored in the precedent study section of this document(pages 12-17).

Wind

We must ensure that the building is protected from strong winds along the southerly and westerly edges during winter, and allow cool north-easterly winds to cool the building during summer.

Noise

Primary sources of noise are traffic from Cleveland street at the south of the site, park patrons on the northern and western edges and trains to the west of the park. When planning our school layout, we should take care to place areas requiring quite away from primary noise sources.

Views

We should aim to maximize panoramic view towards the top levels of our building. We must also consider privacy and overlooking concerns at the base of the school. The western view towards Ultimo, Chippendale and Darlington is least impeded by current planned future developments, but we must also consider that this area will be host to rapid growth in the next decade, and therefore the skyline and views will change over time.

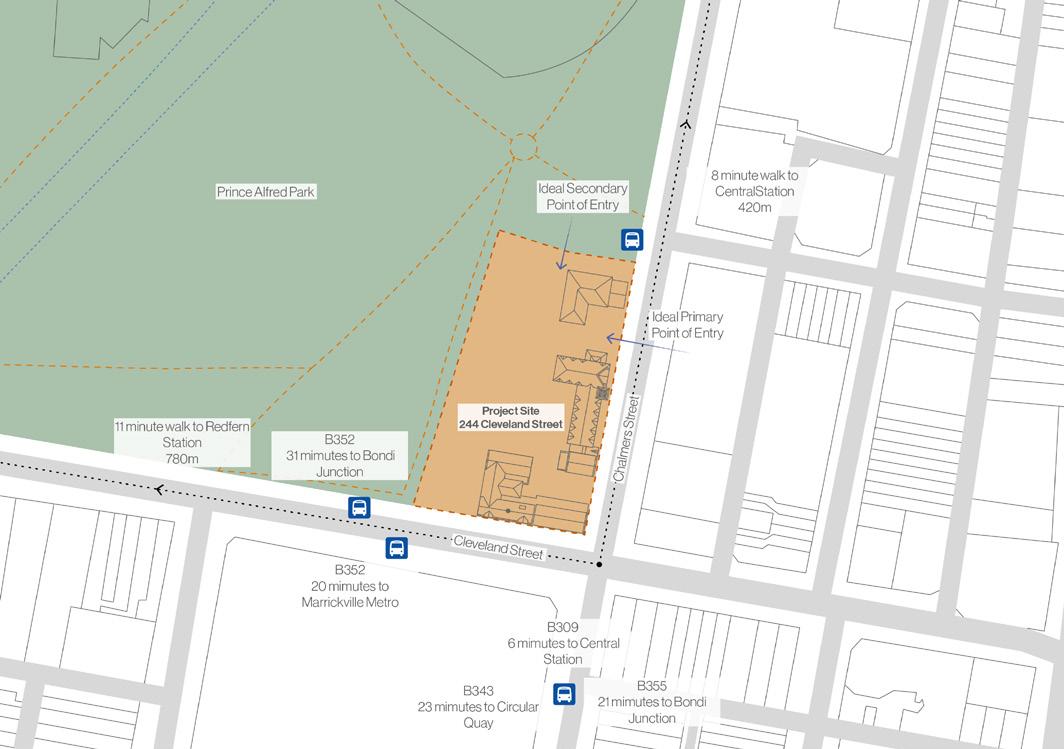

Circulation

The project site’s central location provides ease of access for students and families who reside within the catchment area. It also provides students and teachers with access to a myriad of facilities located throughout the city. Located within a ten minute walk from both Central and Redfern stations and several bus stops, the site is connected to all major routes, and to metropolitan Sydney at large. A network of bike paths across the wider inner Sydney area also provide safe bike access (Sydney cycling map - City of Sydney, 2021).

Host to a transient population the site is frequented by nearby residents, university students, local professionals and many other visitors who make use of the park and its facilities. Pedestrian paths through the park provide access from all edges and ease of circulation throughout. Situated along Cleveland Street, a major arterial road connecting Sydney’s Eastern Suburbs to inner Sydney, the site also sees a high volume of vehicular and passers by.

According to TfNSW, the 2018 average daily traffic count was 22, 937 (TfNSW, 2021). Given the site’s relative ease of pedestrian access from all sides and the high traffic volume of Cleveland Street, we can begin to make inferences about the most appropriate and safe point of entry to the site; a safe distance form the heaviest traffic but still maintaining vehicular access, the Chalmers Street edge offers a good starting point.

Park

Prince Alfred Park is a shared resource and is an undoubtedly valuable asset to the school. We will aim to create a meaningful connection between the park and the new school that allows us to take advantage of the facilities and is respectful of the land and it’s history.

The street entry at Chalmers street was considered most suitable as main entrance due to lower traffic volume and proximity to pedestrian paths in the park.

A smaller rear entrance along the park and corridor views from entry to entry establishes a connection between the park and street edges of the school, but maintains a level of privacy from the general public

Tech and performing arts faculties located in the heritage buildings along the edges of the site to ensure minimal auditory distraction to rest of school. Music and sounds of industrious work may also escape to the street, creating an auditory connection between the activities of the school and passers by.

Naturally occurring courtyards created in the spaces between heritage building provide a generous feeling entry plaza. Interstitial spaces also create a sense of enclosure and are ideal gathering spaces.

Important line of

Body text

This project was an experiment for Tzannes and Lendlease, to see if a sustainable mass timber building could be a viable commercial office building. The building used pre-fabricated glulam and Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) elements as the primary structure, with a concrete base. The International House was Australia’s first engineered timber office building, and has been a huge success both for Lendlease, and for mass timber construction internationally (Hunn, 2017). International House has been important for us as a structural precedent, as we are using mass timber as our primary structure due to its sustainability and flexibility.

Siting & Context

The site in Barangaroo was originally a series of traditional wharfs, and one of the key elements of Tzannes’ design approach was to create a link to the past of the site. The timber wharf piers were reclaimed and used in the new building as cladding for Exchange Place and on the internal stairs. In addition, recycled timber was used as a structural member in the colonnade to Sussex Street (Evans, 2019).

The International House makes up one of the two sisters and three brothers, a group of buildings which have been called the “core of the commercial area” (Evans, 2019). As such, it was important to retain pedestrian connections through the site to access the Barangaroo Precinct. Exchange Place was developed to serve as this connection, and as a community hub. The Exchange connects the existing pedestrian bridges and the Mercantile Walkway on site.

The climate of Sydney was another key consideration; as the first of its kind it was unknown how the extreme UV radiation would affect the timber. Unlike in European constructions, where it would take many days to have an effect, the timber reacted to the UV light within 24 hours, changing from a pale yellow into a deep honey colour (Evans, 2019). This was a welcome change and helps to give the building its warm character.\

Aesthetics & Materiality

In line with their goal of a sustainable design, Tzannes left the timber structure exposed and used minimal finishing materials. This has the dual benefit of not using materials unnecessarily to hide undesirable structural materials and calling attention to the use of timber as the primary structural element. Timber is a warm finish, which has been proven to have psychological and

physiological benefits. It promotes focus and happiness, and promotes a sense of connection to history and nature (ArchDaily, 2017).

The façade glass was also carefully chosen to highlight the timber structure. A low ion glass with no green tint was used to allow the timber to be seen in its true, warm colours from the street. The services visible in the ceiling space were carefully designed in an orthogonal layout and painted an unintrusive matte black, contributing to the clean design of the spaces.

Spatial Arrangement

The use of mass timber in a project on this scale did limit the spatial arrangement due to the limitations of the material. A 6m by 9m grid was used to ensure the structure could withstand its own weight and the weight of its occupants. As the first of its kind, Tzannes wanted to be cautious with the structure and work well within the known limitations of the material. After the success of International House, they are now working on the second sister, Daramu House, which has a 9m by 9m grid. For our project a 7.5m by 9m grid is proposed in the EFSG example Hub Layout, which would be within the known limitations of mass timber construction.

This spatial arrangement was initially worrying for the leasing agents, who knew they would compete with concrete buildings with virtually no supporting or delineating columns. However, the occupants found that the spaces provided by this arrangement were generous enough to work in, and the benefits of the exposed timber structure to the aesthetics and interior quality far outweighed the constraints (Evans, 2019).

Structure

Timber was chosen as a structural material for its sustainable properties. Timber is a store of carbon, and as it grows it removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and produces oxygen. This is a stark contrast to concrete and steel, which during their manufacturing release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Timber is also endlessly renewable, and when sourced locally can have a net positive environmental impact. At the end of its life, timber can be disassembled and reused or recycled.

Timber also has a positive impact on people when used in a beautiful way. Studies have shown that timber interiors have a positive physiological and

psychological benefits for occupants, and particularly in an office (or school) setting, it can reduce stress and anxiety and improve focus.

The ground floor of the building is a concrete base, which protects the timber structure from termites and water damage. It also allows the commercial spaces to have a higher fire rating than the office spaces, as per the Australian Standards. Level 1 to 6 all have a mass timber structure, with glulam beams and columns and CLT wall and floor panels. This is because glulam uses timber layers aligned in the same direction, making it very strong in one direction and ideal for single-spanning members. CLT, as the name suggests, uses timber layers crossed at 90 degrees to each other, which spreads out the force in multiple directions and is ideal for multi-spanning members or cross-directional forces (Evans, 2019).

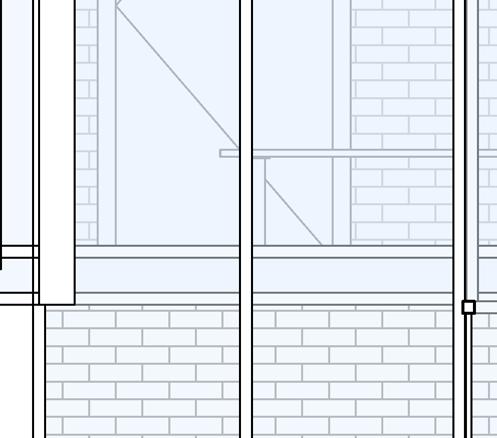

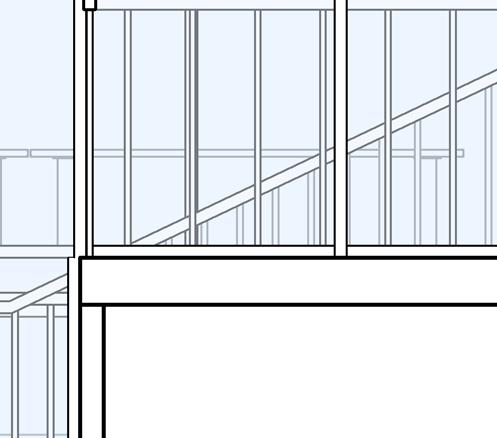

In comparison with concrete, which is usually connected using fixed joints, all timber joints are pin connections. Pin joints are fixed in space but can rotate freely, meaning they are susceptible to lateral forces such as wind and earthquakes (Evans, 2019). In order to maintain structural integrity lateral braces are required. Tzannes decided to make these braces a part of the architectural fabric, treating them as a design element rather than a piece of necessary structure. The result is a pattern of bracing which brings interest and variation to the façade of the building, exposed by the glass façade.

As mentioned previously, in order to comply with Council height restrictions the services were left exposed and running through the ceiling space. Tzannes worked with the mass timber manufacturers to test the load bearing

gives the office spaces a generous ceiling height while actually reducing the overall distance between levels (Lendlease, 2016).

At the time of construction there was no company in Australia who could manufacture the mass timber needed for this project, so the timber was manufactures overseas and shipped here. This meant the design and planning had to be perfect, and presented an opportunity to use prefabricated elements in the design to improve the construction. Engineered timber elements were able to be precision cut and milled, to within a 2mm tolerance on site (concrete usually has 25mm tolerance on site) (Evans, 2019). The connecting pieces were installed in the factory to further increase the speed of construction on site. The fire stairs and lift core were completely preconstructed from CLT panels, with holes for the lift and fire doors pre-cut. The result was a construction time of 1 year, allowing the owners to open and collect rent 3 months ahead of schedule (Lendlease, 2019).

Tzannes placed an emphasis on sustainable systems as well as structure. The façade is double-walled glass with fixed louvres to maximise solar gains for heating. The cooling system uses chill beams rather than traditional air conditioning, tapping into the adjacent harbour to provide cooling and a heat sink. The roof is covered in solar panels, providing much of the required electricity for the site.

Located in the Adelaide CBD next to the botanical gardens, and holding up to 1250 students, Adelaide Botanical High School is South Australia’s first vertical secondary school. The STEM focused school opened in early 2019, and was designed collaboratively between COX Architecture and DesignInc.

Described by Cox as a “school of the city”(Adelaide Botanic High School - COX, n.d.), the site posed similar contextual issues as Prince Alfred Park; ABHS had to respond sensitively to the parklands, whilst engaging with a high density business and university precinct. The location provided the opportunity for learning through the resources provided by the city such as museums, art galleries and libraries.

Methodology and Pedagogy

Before the design stage, the architects allocated over 300 days to collaborate with educators and stakeholders to discuss concepts of future-focused pedagogy. This provided the unique opportunity for the building to be designed for a myriad of teaching and learning styles.

“To participate within the wider world outside the regular school boundary requires a pedagogy that prioritises and develops the student’s ability to be aware, compare, evaluate, listen, empathise and act.” (Adelaide Botanic High School, n.d.)

The main school is 7 storeys, with a basement. The more public programs are located on the bottom of the school and private learning spaces at the top. An existing 1968 building was stripped to the structural frame, with the interiors and facade transformed. (Adelaide Botanic High School - COX, n.d.)

The central communal space of ABHS is the “active atrium” that links the existing building to the new one. (Sacred Spaces, 2020). This space provides views to surrounding context of the CBD on one side, and the gardens on the other. Maximised daylighting minimises any feeling of classrooms being enclosed, which is a common constraint in vertical high schools.

As well linking old and new, the atrium creates a sense of community through visual connections between the learning spaces on each side, a unique opportunity offered by the vertical school typology. These horizontal links become physical through circulatory bridges spanning across the atrium, allowing single floors to become “horizontal learning communities” (Adelaide Botanic High School - COX, n.d.)

The central stairs also double as a furniture piece, with bleacher-style seating, and sunken areas. This encourages students to utilise this as their main mode of circulation instead of lifts. The furniture can also be used as informal learning spaces or group gathering areas. After a year of usage, it was reported that the atrium quickly became the heart of the school; an inviting, light-filled central meeting space with sufficient connectivity to both buildings.

Materiality

A strong timber motif is used throughout the design, especially in the atrium. The use of a natural materials is important for a site and program like this as it provides a link to the gardens nearby and softens interior spaces, making it seem less sterile, Perforations in the timber and plasterboard were made to assist acoustics, as large atrium spaces tend to echo. The EFTE roof of the atrium is a light, heat-resistant plastic film that serves as a great sustainable alternative to glass with low embodied energy. It can be layered or printed with patterns to control heat gain and daylighting depending on environmental and weather conditions. This ensures climatic comfort for users year-round. (What is ETFE and Why Has it Become Architecture’s Favorite Polymer?, 2019) (Adelaide Botanic High School - ARUP, n.d.).

As a result of the pre-design stage, ABHS has a unique approach to learning, with a heavy emphasis on interdisciplinary, future-focused education. Instead of separating by faculty, the whole school is viewed as a “learning precinct” consisting of a series of specialist teaching spaces, flexible learning areas and “learning commons” (untimetabled informal study spaces). Each floor is a unique combination of these, connected both visually and physically. The adaptable spaces in combination with a range of adjustable and moveable furniture pieces, enables teachers to have a unique and adaptable approach to pedagogy. Students are encouraged to view education as all-encompassing, and not isolated to a single discipline. This is aimed to motivate problem solving, adaptability and lateral thinking, preparing them for real-life situations after graduation. It also deepens the sense of community and encourages between faculties.

“The vertical form invokes a dynamic approach based on agility and a desire to de-institutionalise the education experience. No two floors are the same, instead each offer a variety of programs, distinguished by their character and materiality.”- (Adelaide Botanic High School, n.d.)

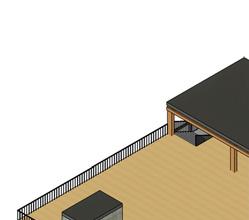

Outdoor Spaces

The main outdoor space is a large trafficable roof terrace situated on top of the gym. This provides a unique angle of the botanical gardens, made seamless through roof gardens lining the area. The “passive play” space is a general recreational area during break times, with a beautiful outlook. These flexible outdoor learning areas connect with permanent classrooms resulting in a pleasant, adaptable and light-filled space. (Sacred Spaces, 2020)

Sustainability

This building has a 5 green-star rating. Solar harvesting and water collection techniques are used, alongside an elaborate exposed mechanical services system. This architectural choice explicitly communicates the sustainable functionality of the building, providing a teaching tool for students to learn about energy and water consumption. (Adelaide Botanic High School - Cox, n.d.) These services ensure that all learning areas have a fresh air supply (Adelaide Botanic High School- ARUP, n.d.). The indoor air quality is also improved through the use of low VOC paints (Sacred Spaces, 2020) which are safer for the respiratory system (Cheng, Huang, Chen and Chang, 2017) Thermal capability is improved through the ETFE roof, as mentioned earlier. Other features include the high thermal capacity of the trafficable roof terrace, and the use of drought-tolerant plants to minimise water usage.

Due to the central location, the school is easily accessible by public transport, and this is encouraged through walking and cycling paths connecting the school to the larger precinct. The inclusion of many bike racks encourages cycling to school, a viable option due to the high density area. A kiss and drop zone is also included for those who need to travel by car. (Adelaide Botanic High School - ARUP, n.d.)

Relevance and Analysis

The similar site features of ABHS gives a useful interpretation of how to adapt to an Australian Inner-City context. Additionally, it also had the challenge of engaging equally as sensitively to the parkland surroundings. It designed around utilising opportunities for learning resources in the larger precinct, and

also encourages the use of public transport and cycling due to its connected location. Our response may differ aesthetically different as Surry Hills contains more historical architecture such as bricked terraces and larger sandstone buildings, but we can engage with similar principles.

We are also interested in pedagogy and contemporary ways of teaching, and have followed a similar preparation approach by interviewing a range of teachers, students and local residents. Through their critiques of current schools, our design process will be centred around solving these issues, and ensuring a pleasant, social and productive learning environment.

During interviews, teachers were shown images of the atrium and learning spaces. The atrium space was generally received positively; the only main qualm being noise. Teachers reported it being a great for assembly, sharing of ideas, wet weather, and an opportunity for inter-cohort interaction.

Feedback on the collaborative spaces was mixed; it was mentioned on multiple occasions that they are often a source for visual and auditory distraction, and that circulation spaces may have to be wider. Additionally, some respondents communicated an importance for teachers to own and personalise their spaces. There is less opportunity to display work on walls, for individual climate control, and for personal desks and storage. The mix of spaces also eliminates a sense of community within faculties, and amongst students of similar interests. It also may form difficulties in communication and centralised storage. However, the idea of flexibility was still seen as important in encouraging peer-to-peer learning, teaching interpersonal life-skills and adapting to different student needs. This is especially true as students have been enthusiastic about group work after returning from online learning during the pandemic. Collaborative learning spaces like the ones in ABHS, in combination with more traditional classrooms will provide a balanced and adaptable educational style that caters to numerous pedagogies.

ABHS is also an example of effectively designing an activated threshold space between old and new construction. It also provides us with some effective sustainable design principles, both in terms of performance and architectural communication.

Nantes School of Architecture / Lacaton + Vassal

Heading

Generosity and Freedom: The Architectural Theory of Lacaton and Vassal

French architect duo Lacaton and Vassal’s practice is rooted firmly in their architectural theory. Committed to creating an architecture of “spatial versatility and climatic flexibility”, Lacaton and Vassal follow an almost formulaic design methodology, and approach each project with equal parts pragmatism and imagination. The fundamentals of their process are this: assess both the physical and socio-political context, establish the requirements of the patrons, determine the qualities present in the existing building or site, retain what is good and “add quality where it is not already present” with minimal intervention.

The pair understand that architecture continues to evolve past the completion of construction, as the inhabitants appropriate the space in their own way. While the physical architecture reflects a fixed moment of intent in an evercontinuing narrative, the ways in which it may be interpreted and transposed are infinite, and will perpetually evolve and shift with each passing moment.

(Vidor, 2019)

We feel that Lacaton and Vassal’s architectural theory aligns with our own priorities when considering the design of a vertical high school; a sympathetic consideration of the building as part of a whole within the city, designing with user experience and freedom as a topmost priority and creating an architecture that is able to evolve over time to accommodate shifts in programmatic requirements and inevitable increases in required capacity.

Siting and Context

Completed in 2009, the Nantes School of Architecture is located in Nantes in north-western France.

Lacaton and Vassal’s approach to siting is one of sympathy and respect for the existing context, viewing each structure as a part of a rich tapestry that comprises the urban fabric. Following this approach, the base of the school touches the ground in way that connects it both visually and physically to site on which it sits. Continuing the tarmac into the ground floor, the base of the building becomes “a literal extension of the street” (Slessor, 2009). Thus, the building becomes a continuation of the city, and the city inhabits the building.

A ramp slopes up the exterior of the building from the ground to the rooftop. In addition to connecting every level of the building with the street, and therefore with the city at large, the external ramp provides a visually comprehensible mode of circulation that creates both ease of physical access and clarity of navigation. Whilst our own design will be both larger in height and a smaller in footprint, we can learn from this project the importance of a sensitive groundplane in siting a building within it’s context, and the value of circulation as a means of not only providing access, but also (this being of particular importance to a mid-rise building such as ours) of creating a dialogue between the ground and the sky.

The school is comprised of “three decks at nine, sixteen and twenty-two meters above the natural ground level, served by a gentle sloping external ramp” (Nantes School of Architecture / Lacaton & Vassal, 2012). Its framework is a concrete superstructure into which many smaller elements may be imposed and interchanged. This freedom of internal configuration, separate from a fixed and generous skeleton means that empty spaces can be rented out by the school for a number of different uses by the community and the building has the capacity to be easily adapted to accommodate a different program in the future (Messu and Patteeuw, 2009). This approach of a fixed external structure containing flexible internal ‘guts’ is a sustainable one.

The architecture is not static, it moves with the user and with use. We find these qualities to be especially valuable when considering the functioning of a school. We can learn from the dynamic way Lacaton and Vassal inhabit the grid. Their approach allows for the users of the building to appropriate the space to suit their preferred pedagogy and ensures that the building has the capacity to evolve alongside these pedagogy.

This level of flexibility is both admirable and aspirational, however we must consider the differing spatial requirements required in a high school. A great level of flexibility imposes a certain level of responsibility on the users of the building. Whilst we consider the incorporation of flexible, unprogrammed spaces to be a necessity for a well functioning and future-conscious high school, we also understand that there must be certain areas where the architecture is fixed and where distractions must be removed or mitigable.

In addition to the flexibility of the interior layout, the Nantes School of Architecture also provides a level of flexibility between interior and exterior conditions. The transparency of the EFTE cladding and the flexibility of the facade elements offer both passive warming and cooling opportunities to the building, but also a greater level of connectivity between the school and the city.

Within the flexible grid, Lacaton and Vassal have inserted double height spaces with mezzanine levels. This creates a sense of generosity of space by generating a variety of different spatial experiences within the same confines of an architecture. These enclosed, transparent, mezzanine level volumes offer visual access to other parts of the building and allow light to be brought into the core spaces.

The visual access that these raised transparent volumes offer is also a key feature that may be beneficially applied to our project. These transparent boundaries serve a dual purpose of partitioning or enclosing spaces without compromising safety or security, and providing connections between school spaces through visual links. Through deliberate use of spatial planning and landscaping, we may also use transparent or permeable/operable facade elements to bring green spaces into the school building.

The project’s programming was developed from the beginning in collaboration with the school’s director (Messu and Patteeuw, 2009). One of the cornerstones of Lacaton and Vassal’s practice in the early stages of their process is community engagement. By speaking with the communities and inhabitants of the buildings they are erecting, they ensure that they establish the priorities and requirements of those for whom they are designing before commencing a project. This approach resonated with us deeply. We have thus made an effort to begin collecting data and feedback from current high school students and teachers, from which we will begin to formulate a set of rules and requirements that will inform and drive our design.

Participatory design approach

As designers, we believe it is essential for students, teachers and community members to be present throughout the design process in order for the school to most effectively serve its user-base and the wider community. Although we were restricted due to the current lockdown, we took inspiration from the work of Professor Henry Sanoff, who has specialised in this field for over 50 years (Sanoff, 2011).

- Understanding the uniqueness of the local area

- Establishing needs and desires of residents

- Analysing local architecture and the site

- Discussing ways a new school can contribute to the community

Traditional ideas of democracy are often described as “low quality citizen action by making a fetish out of only one form of political participation-voting” (Pranger, 1968). In reality, a large proportion of the population cannot hugely impact the politics and policy-making of their society. In the 1960s, the concept of participatory democracy was developed, viewing existing ideas of democracy through a new lens of decentralised collective decision making. (Sanoff, 2011) This concept was then adopted into the design field, enabling users to no longer passively consume space, but to actively involve themselves in the generation and operation of architecture.

- Evaluation of personal school experience

- Establishing universal and specific needs

- Responses to precedents

In addition to gaining a deeper understanding of the current needs of students and educators through our interviews, we thought it was important to explore where the future of learning is headed. Whilst our aim is to design a school that can accommodate the current needs of its users, a future conscious approach is equally important to ensure that our building can evolve with our community.

that educational institutions introduce a wider mix of pedagogies including crosscurricular content and team teaching and greater use of inquiry and project-based learning.” (Foundation for Young Australians, 2017). The national curriculum is beginning to focus more on these transferable soft skills. When we discussed these future projections with our interview subjects, the response from teachers was overwhelmingly in support of this direction.

Despite only the senior students we interviewed expressed a need for study spaces within the school, our research has shown us that independent research and project based study will become integrated from the very start of high school. From this, we were able to adjust our approach to the design of our ‘library’ spaces to accommodate all cohorts.

In his book, Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (1992), Sanoff states that:

• Participation is inherently good

needs already addressed in previous stage

• It is a source of wisdom and information about local conditions, needs, and attitudes, and thus improves the effectiveness of decision making

• It is an inclusive and pluralistic approach by which fundamental human needs are fulfilled and user values reflected

• It is a means of defending the interests of groups of people and of individuals, and a tool for satisfying their needs which are often ignored and dominated by large organizations, institutions, and their inflated bureaucracies.

(Sanoff, 1992)

- Evaluation of initial design

With this in mind, we took inspiration from his suggested structure of participation and developed a 4-5 stage process in which we would engage with our focus group. This consisted of a series of interviews and surveys with current students, teachers and administrative staff from various high schools We found that the collection of anecdotal data through discussion with these sources was the most successful and valuable method of gathering information on the needs of the wider school community. Following these initial conversations, we spoke further with a number of our interview subjects who have consented to engage with us throughout the remainder this project.

- Any necessary further information, discussion and evaluation as iterations continue

- Discussing the future of learning

- Presentation of design concepts for evaluation

- Analyse e ectiveness of example hub layouts, discuss potential alternatives

- Evaluation of initial design

- Any necessary further information, discussion and evaluation as iterations continue

Trends are overwhelmingly pointing towards a move away from skills-specific learning and towards the development of transferable soft skills, often referred to as “enterprise skills”(Foundation for Young Australians, 2017). “These are transferable skills that allow young people to be enterprising so they can navigate complex careers across a range of industries and professions. They... are different from technical skills which are specific to a particular task, role or industry” (Foundation for Young Australians, 2017). Our focus does not reflect a capitalist desire to increase student’s employability or facilitate a school to industry pipeline, but rather an aspiration to understand the way the world is moving as a whole; to create a new generation of creative, deep thinkers that are critically engaged with the world around them. As one teacher we interviewed so aptly put it,

“It’s not about giving the students a bucket full of information, but rather giving them an empty bucket and teaching them how to fill it”.

Thus, we are in favour of and will attempt to design for a new approach to education that “must prioritise new skills, work integrated learning and be designed by all stakeholders, including young people” (Foundation for Young Australians, 2017). Our participatory design approach is testament to this

intention.

Rethinking teaching methods

The post-pandemic age

When looking towards the future we must consider the effects that the Covid-19 pandemic will have on the way we work, learn and gather. One of the after-effects of the pandemic is the increased exposure of societal inequalities, such as access to technology, or a space to work. With this considered, particularly given the demographics of the catchment area, we believe that the necessity of the physical school that provides all the necessary requirements for good learning is more important than ever.

Additionally, increase flexibility in education is beneficial, but does discount the necessity for properly equipped schools. Whilst remote learning is now a viable option for when necessary, it is unsustainable for many. Additionally, to foster a the development transferable soft skills, “physical proximity to other creative people is more important, not less. Working together helps us collaborate and socialise, as well as giving us infrastructure and support. So the office [/school] is not going away any time soon.” (Deloitte, 2019).

Teachers mentioned an increased desire for group work, and to be away from screens in the student body after lockdown. With this in mind, the role of the physical school is moving towards a social hub of team and project-based learning, as these tasks cannot be completed effectively from home.

When presented with this research, the response from the educators we interviewed was very positive overall. We used our findings from this research coupled with our findings from our phase one interviews to begin generating our conceptual approach.

- Working documents

- Construction

- Post-occupancy evaluation

- Working documents

- Construction

- Post-occupancy evaluation

Another important way to future-proof our school is to understand trends in curriculum shifts around the world, so that our building can adapt to possible changes in education programming. One of the key points we found was that ”teaching enterprise skills often doesn’t require discrete subject matter but instead requires a change in pedagogy. Around the world, leading educators are focusing on inquiry approaches and collaborative work. In order to promote 21st century skill development, the OECD has recommended

• 100% of students interviewed expressed a preference for non-enclosed or only partially enclosed stairwells

Insufficient circulation space was also noted as one of the primary inhibitors of navigational ease and sources of congestion

• 60% of students, predominantly in the younger years, commented that it is preferable to situate classrooms for core subjects close together

Students also expressed the value of “landmarks” such as trees and central courtyards within the school as important aids to navigation

• 75% noted lockers as important gathering spaces for both cohort and inter-cohort interaction

Students also noted that locating common facilities such as benches and play areas near shared locker spaces would encourage their use by all year groups and minimise dominance of shared facilities by older students

• 60% of students noted the necessity of appropriately sized spaces for mid-sized gatherings such as year meetings

• 50% noted basketball courts as preferable passive and active play spaces, but noted that insufficient space often leads to these spaces being monopolised by a particular group, often citing senior boys.

• 50% also noted grassy areas as preferable lunchtime gathering and play spaces, citing access to parks as ideal.

• 30% noted a necessity for sufficient “outdoor” partially covered wet weather play areas

• 50% noted a desire for an increased size of the school campus

• 50% felt that they had a sufficiently sized campus, but expressed the desire for more unprogrammed free to appropriate spaces

• 75% noted a desire for sufficient outdoor study facilities such as benches, for casual study and group work

• 100% of students noted the library as a popular independent study space

Students noted that the library was predominantly used as a study space rather than a place for research and reading

Students expressed the necessity for a library space or spaces with different conditions to accommodate different forms of study, e.g. a quiet room for individual study, a larger open area for group study, meeting rooms for project based work/collaboration

• 100% of teachers noted the necessity for multiple access points, and those modes need to be generous enough accommodate mass movement e.g. stair and hallway widths need to be generous

It was also noted that accessibility issues arise in particular in heritage buildings,a and from poor transitional spaces between new and old buildings

• 75% of teachers noted the importance of having one main entry point for security reasons. Signing in and out needs to be easily monitored, as well as ensuring all visitors are accounted for

• 85% of teacher noted that accessibility was insufficiently accounted for in their schools. There needs to be a sufficient number of strategically placed lifts, in addition to accessibility ramps where required

• 50/50 - Teachers noted the equal advantages of both centralized and separate faculty staff rooms

Faculty staff rooms foster a strong sense of community and stronger relationships between the staff. They can also be personalized.

Centralised staff rooms create a cohesive and communicative overall staff team and encourage inter-departmental collaboration.

• 100% of teachers cited the gymnasium as the designated school assembly space. These gatherings are executed through the use of moveable furniture and stage.

Teachers also noted the necessity of a space to accommodate mid-sized gatherings as well.

• 100% of teachers spoke about the importance of outdoor furniture, sufficient shading and ease of supervision.

Many teachers also noted critical role of socialising in the adolescent school experience. Recreational spaces should offer varying conditions to suit different students of all ages and interests, from year sevens entering a new school, to year twelves creating a strong sense of cohort community.

• 85% of teachers noted that the pandemic prompted an increased preference for group work amongst students, and highlighted the necessity of human interaction in the classroom

There was a noted necessity for the improvement of technological literacy amongst both students and teachers, with particular not on ensuring equal accessibility to tech resources.

• 60% of teachers noted the value of the traditional classroom format and advised that it should not be discredited or discarded. Teachers noted in particular the benefits of properly dedicated classrooms in creating ease of personalisation and limiting external distraction.

Teachers also noted the importance of distinguishing between flexibility achieved through architecture, e.g. partitions and transparent elements, and through furniture layouts.

Classrooms should facilitate easy interaction between students and teachers, rather than lecture style pedagogy more suited to universities.

• 100% of teachers noted the importance of aesthetic in reflecting the school’s goal as a learning space. A sterile and commercial space negatively affects how engaged students are with their learning

Suggestions were not limited to the inclusion of greenery to provide a positive psychological impact, and creating a sense of playfulness through colour

Stimulus responses

In our follow up interviews with students and teachers, we discussed the future of education and our initial proposed spacial arrangement concept and reviewed the SINSW hub layouts, all aided by visual stimuli.

A hub for each faculty

Our intial conceptial proposal was that of the ‘piazza’, a central space for faculty engagement and gathering, bordered by the required spaces for each subject. Whilst we diverged from this typology as our design progressed, the concept of a faculty hub and the creation of immersive spaces for each subject was very positively recieved. The idea of dividing the library into faculty areas and distributing study spaces of varying conditions throughout the school was also positively recieved.

11

SLSO specific feedback

A generous staircase - integrating circulation and gathering spaces

The overall feedback from interview subjects was positive. Many noted that this stair typology could accommodate medium sized or casual meetings for which there is not often appropriate space provided in schools.

Well integrated circulation was also cited as a good way of facilitating more frequent interactions between different cohorts.

Revised hub layout examples

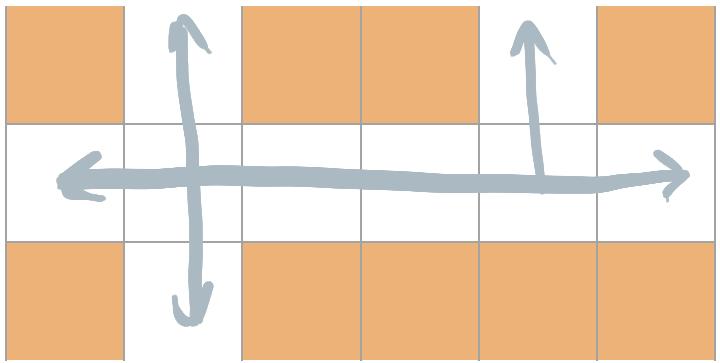

The internal boulevard

In addition to the ‘piazza’, another urban typology we sought to appropriate for the indoors was the indoor street or boulevard, through the provision of generously wide hallways and visual connectivity between closed volumes.

The response to this idea was positive, with particular appreciation of the sense of connectivity between spaces. A note was made however, that transparency should be adjustable where distractions need to be limited.

12

Through interviewing School Learning and Support Officers, we learned the importance of not only physical, but sensory accessibility. It is important for these spaces to have direct navigation routes and are not decorated with stimuli that may be overwhelming. The Support Learning Hub was met with positive feedback, and it was noted that it should be placed in a location that feels part of the rest of the school. Additionally, the positioning should prioritise ease of navigation so students do not get caught in large crowds during peak times.

Student + teacher observations:

• a. Traditional classroom spaces not suitable for many aspects of performing arts (e.g. band practice, drama games etc.), so should be easily convertable to accommodate these uses.

• b. Acoustic curtains as divisions create a sense of showmanship in the space and are a practical method of sound reduction.

• c. An atrium space at the point of entry for “box office”, audience congregation, storage and “backstage” use would be very valuable.

• Access to dark room is too central - should be located somewhere easy to monitor to control permissible entering and exiting (can’t let light in)

• Kiln gets very hot so needs to be near an external wall with ventilation (WHS)

• The immovable utility / specialised space in centre seems strangely located. This specialised facility should be located along an edge

• General learning spaces should sit in the central area of the hub and have partitions that allow it to be opened up and used as a gallery space

Teacher observations:

• Integrate seminar rooms / multi-purpose spaces into the main library area

• Relocate or disperse senior study and computer labs throughout the school so that every faculty and cohort has easy and access to them

• Disperse casual study spaces throughout the school - the library does not need to be centralised

• Provide some sufficient space for reading - use of library for fiction books is particularly common in the younger years

Analysis of universal urban design strategies to both connect seamlessly with the wider context, and create ease of navigation. We were inspired by multiuse centralised urban squares, as well as pedestrian street typologies. These aid us to design effective gathering spaces and activated circulation space between programmatic features.

The urban square

Centralised gathering with multiple points of entry and no clear line of circulation. Piazza Del Campo, Siena, Italy

- Specialised library resources

- Lounge/gathering spaces

- Open space, flexible and collaborative uses

- Circulation

Web of connections

Urban squares are connected by wide streets and smaller alleyways to create a unique web between gathering spaces

The town as a street

The negative space between buildings reveals activated circulatory space and no need for connecting alleyways. Telc, Czech Republic

Activated promenade

Indoor streetscape of multi-use spaces bordered by facilities

Meeting rooms / quiet study spaces

/ workshops / specialised spaces

Perpendicular connections

The addition of East-West connections gives opportunity for prospect and refuge, and connection to the wider context

Outdoor learning spaces

General learning spaces with partitions between

- Specialised library resources

- Lounge/gathering spaces

- Open space, flexible and collaborative uses

- Each floor is unique in spatial quality

Labs / workshops / specialised spaces

Sta touch-down / hub

The urban square Piazza-like incidental gathering spaces are scattered along the promenades

Unique combinations

A combination of promenades, squares, refuge and prospect to the city from all angles allows each floor to provide a unique and active multi-use learning streetscapes

When analysing these urban design concepts within the physical boundaries of the site and program, we came to the conclusion that all spaces should be activated and have flexible usage. Through many iterations, we connected the large gathering spaces with activated promenades to avoid narrow hallways. This not only gives the school a sense of openness, but eliminates bottlenecks through a single, wide path of circulation. Additionally it is easier for teachers to surveil students as there are minimal hidden spaces. Wide corridors allow for traditional and specialised classrooms to open into an activated multi-use collaborative space, whilst still guiding the main flow of circulation through the building. This typology is suited to traditional classroom settings as well as future-focused project-based education because it allows the teachers to personalise their own classroom whilst having the option to open up into many unique spaces, depending on their pedagogical style. Additionally, the typology fits effectively into a grid, and can be expanded vertically due to its modular form.

Library spaces and their uses have evolved, especially as our society progresses technologically. This was discussed in depth with interviewees, and it was concluded that libraries, whilst still maintaining their traditional role as a space to borrow and read books, now serve more as a hub for

information and research. Students tend to use the space more as a location for studying and sharing ideas.

Many interviewees gave sentimental anecdotes regarding the sense of community created through faculty. It was often observed that subjects with a designated space served as a refuge for students to connect over their shared passion for a particular learning area. These relationships transcend cohort boundaries, and often students were much closer with teachers due to their genuine interest in their speciality. This offers an opportunity to create unique personalised spaces, and an increasingly interconnected school community.

With this in mind, we decided to split our main library space into a series of smaller libraries throughout the school. This not only allows us to separate floors by faculty, but gives teachers immediate access to relevant resources, and students a designated area to study with like-minded peers and educators. We initially intended for these libraries to be separated based on subject area, but after more feedback from teachers, we decided to leave them undesignated. This architectural choice encourages inter-faculty interaction and collaboration, which is essential looking forward to the future of education.

Preliminary Design Evaluation and Design Development Consultations

After the submission of our preliminary design, we went through the drawings with our focus group and received feedback on our initial concepts and spatial arrangement. The comments were overwhelmingly positive, and no major changes were suggested. The main student comments were to allow space for activities such as handball in the outdoor spaces, and to provide soft furniture for casual reading in the library. Aside from smaller technical comments regarding specialised spaces, the feedback that permeated was how to improve the activated streetscape spaces. Many teachers felt that a more future-conscious approach would be to avoid allocating these spaces to specific subject areas, as it discourages inter-faculty collaboration. Their comments aligned with our initial research; the future of curriculum design and education as a whole is moving towards a interdisciplinary and cooperative approach. It is important to facilitate this as much as possible through architecture as it encourages students to think laterally and prepares them for life after graduation.

After these evaluations, we spoke to educators about spaces on a smaller scale; how our library spaces would operate to cater to different pedagogical styles and ways that flexible furniture layouts can influence how a space is used, to name a few. We drew some real-time diagrams with teachers to further understand how different layouts and spatial arrangements are effective for different types of learning. We then implemented these concepts into our library and classroom design.

The spatial quality of our streetscape spaces was discussed in depth at this stage of the process. We gave subjects many precedent images to respond to; Fig 26 and 27 were the most popular as they were boundary less, flexible and contained many potential formal and informal uses.

A teacher at Sydney Secondary College, Leichhardt gave us an in-depth tour of their “iCentre”. Much like our previous discussions, this library space is designed with the future in mind, with a multitude of different education and practical spaces. They aimed to create three different environments that suit different styles of learning; Campfire, Cave and Waterhole (see left). The students have responded extremely positively since its creation. We were very inspired by the potentialities of this kind of space, and aimed to utilise similar concepts in our streetscapes.

Two teachers commented on the importance of visual connection, but noted that glazing should be used sparingly on internal classroom walls. This is to avoid distraction and feelings of exposure. One subject suggested having high level windows into the hallways as it creates connection, but students cannot see out of them whilst they-- are sitting down.

New Museum for Western Australia

Hassell + OMA

The intricate ornamentation of the masonry heritage buildings is left unchallenged by the simple monolithic cubic forms of the addition. The reflective underside of the suspended addition creates a canvas onto which the heritage forms are transposed, while the crispness of the white perforated metal screening feels light and unimposing suspended above the masonry buildings below. This material palette compliments the heritage buildings without diminishing their stature and character. Unique shapes and patterns are created in voids that mark the threshold between old and new.

The suspended form of the new building over the site creates a sense of shelter in the plaza below. This precedent was heavily inspiring for us, as we wanted to create a contemporary structure that embraced the beauty and uniqueness of the heritage façades whilst embodying its own distinct character. The twisted cubic form allows for the implementation of a modular grid system, and the perforated facade maintains privacy whilst also maximising sunlight inside.

We chose to create a permeable brick façade. This allows air to flow through for the natural ventilation of the building, illuminates the northern rooms, protects the windows and hides the necessary ventilation grids.

The perforated brick screen touches the ground as the masonry heritage buildings do, and serves as a grounding base for the lighter elements suspended above. This material interplay between heavy and light creates a respectful dialogue between the old and new. Through the use of a blonde brick, we aim to link the heritage with the new construction through texture, whilst also creating juxtaposition of colour.

The perforated metal façade provides shade and privacy, and the operability of the screening elements offers the opportunity for the creation of varied conditions inside the building. The perforations both allow light in during the day, and out at night, creating a lantern-like effect and positioning the school as a beacon marking the entry to Surry Hills.

The warmth of the timber structure mitigates any sterility that may arise in a building of this scale and the dispersal of green hues throughout the shading fins on the Western façade creates a sense of playfulness, and connects the façade to the dense tree canopy that it borders.

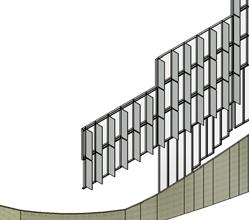

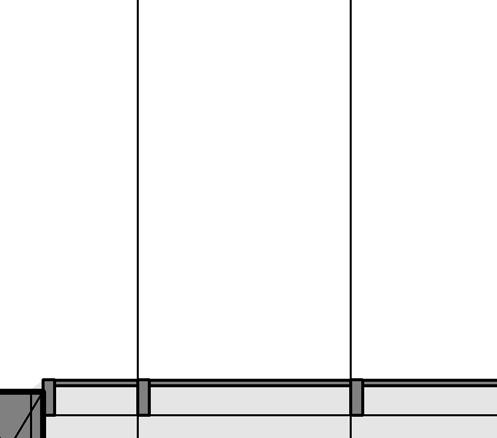

The main structure of the building is mass timber. This system uses a combination of Glulam and Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) as the columns, beams and floor plates. The single spanning members use Glulam timber, which is strong in one direction, and the double spanning members use CLT as it disperses loads in all directions. This system lends itself to a prefabrication system, allowing the columns and beams to be cut and finished with connections in a factory, then shipped to site to assemble. The floor plates, structural walls and main stairs can also be assembled in a factory, with insulation, acoustic panelling, and electrical connections. This allows for a fast construction on site and creates a framework which can be added to or taken away and reused as the building needs change.

In order to create the large open space required for the gymnasium a steel portal frame will be used. The foundations of the basement gymnasium will be concrete, with a brick facade. The portal frame will provide a larger span than mass timber is currently capable of supporting, and will provide a solid foundation for the main entry and gathering point on the ground floor.

Through previous precedent analysis and with the ESFG Hub Layouts in mind, we decided to employ a 7.5m x 9m grid for the timber structure. This is within the documented limitations of mass timber as a spanning member (Silver, McLean & Evans, 2013), and it allows us to utilise the more generous spaces in the Hub Layouts document, uninterrupted by structural elements.

This project aims to utilise the Cradle to Cradle methodology to create a flexible and sustainable building. The timber and steel structural members are designed for disassembly and reuse, using bolted connections for ease of assembly. The pre-fabricated wall and floor panels are also designed for reuse, and the structural grid can be turned to offices, apartments and public buildings as easily as a school layout. Even the facade systems of doubleskinned glass and timber/metal cladding can be reused along with the other structural elements, or recycled to be used in other projects.

The use of concrete is limited to the basement foundation, as it cannot be reused or recycled. The brick facade will be made up of reconstituted brick, reducing the need for new materials further.

In order to encourage the stairs as the primary mode of circulation between classes, the main stairs are located on the park edge of the building and create a light and open gathering space. The classes are gathered in department floors to keep travel between classes as easy to navigate as possible. In addition, a TWIN Lift system (TK Elevator, 2021) will be used to reduce the shaft size and increase the operational speed of the lifts.

The building employs a 7.5m x 9m grid for the timber structure. This is within the documented limitations of mass timber as a spanning member (Silver, McLean & Evans, 2013), and it allows us to utilise the more generous spaces in the Hub Layouts document, uninterrupted by structural elements.

In order to cantilever out over the heritage buildings on the Western facade, a combination of hybrid material beams and Duogong-inspired bracketing is used. This Chinese bracketing system is a series of progressively cantilevering beams that assist one another in transferring the forces to the ground. The 100x300 cantilevered beams are reinforced with steel sections, and sandwiched with timber. The steel beam enables us to have a cantilever of this size as it is much more resistant to bending forces. These beams bracket 300x500 Glulam timber columns on either side, allowing for one continuous member to span the width of the building and cantilever over the heritage buildings.

The perforated metal shading fins and the framing for the double glazed curtain wall are both pinned into the CLT sandwich panel floorplates. On the Eastern side, the corrugated metal operable facade skin is pinned directly into the columns. The perforated brick skin on the Western side is reinforced by steel C sections.

WORKSHOP

MISC.

SCIENCE

SCIENCE

VISUAL ARTS

FOOD TECH / TEXTILES

MATHS

ENGLISH

HUMANITIES

STAFF

SCIENCE

SCIENCE

FOOD TECH / TEXTILES

IMAGES

Fig 1 - SIX Maps, n.d. SIX Maps. [image] Available at: <https://maps.six.nsw.gov.au/> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

FI2 – Data from ABS Census Data. 2017. 2016 Census QuickStats. [online] Available at: <https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/ SSC13715?opendocument> [Accessed 16 August 2021].

Fig 3 – Data from ABS Census Data. 2017. 2016 Census QuickStats. [online] Available at: <https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/ SSC13715?opendocument> [Accessed 16 August 2021].

Fig 4 - Informed Decisions, n.d. Method of Travel to work, 2016. [image] Available at: <Profile.id. n.d. Surry Hills Profile Area. [online] Available at: <https://profile.id.com.au/sydney/ about?WebID=280> [Accessed 8 September 2021].> [Accessed 8 September 2021].

Fig 5 - Forecast.id.com.au. 2019. Dwellings and Development Map. [image] Available at: <https://forecast.id.com.au/sydney/dwellings-development-map> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 6 - Figure 4: Greater Sydney Commission, 2017. Innovation Corridor Diagram. [image] Available at: <https://gsc-public-1.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/draft_greater_sydney_region_ plan_web.pdf> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 7 - Guthrie, B., 2017. Photo of Exchange Place. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/871807/international-house-tzannes> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 8 - Guthrie, B., 2017. Photo of Meeting Space. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/871807/international-house-tzannes> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 9 - Lendlease, 2016. Beam Analysis Extract from the Finite Element Model Showing Service Penetrations. [image] Available at: <https://www.forum-holzbau.com/pdf/29_IHF_2016_ Butler.pdf> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 10 - Evans, J., 2019. Diagram of Timber Disassembly. [image] Sustainable Architectural Practice: Mass Timber Construction in the Commercial World.

Fig 11 - Lendlease, 2016. Pre-Assembled Lift Core, Braced Bay Lifting, and Installed Braced Bay. [image] Available at: <https://www.forum-holzbau.com/pdf/29_

Fig 12 - Thompson, R., 2017. HESS TIMBER Composite Beams. [image] Available at: <https://www.hess-timber.com/en/references/detail/international-house-sydney/> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 13 - Cox Architecture, 2018. Render of Adelaide Botanic High School. [image] Available at: <https://indaily.com.au/news/2018/05/29/adelaide-botanic-high-health-technologyvision/> [Accessed 24 August 2021].

Fig 14 -Noonan, S., 2019. Adelaide Botanic High School. [image] Available at: <https://www.coxarchitecture.com.au/project/adelaide-botanic-high-school/> [Accessed 22 August 2021].

Fig 15 - Adelaide Botanic High School, n.d. Diagram of Interdisciplinary Approach. [image] Available at: <https://abhs.sa.edu.au/educational-vision/> [Accessed 24 August 2021].

Fig 16 - Noonan, S., 2019. Adelaide Botanic High School. [image] Available at: <https://www.coxarchitecture.com.au/project/adelaide-botanic-high-school/> [Accessed 22 August 2021].

Fig 17 - Ruault, P., 2009. Ecole d’architecture, Nantes. [image] Available at: <https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=55> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

Fig 18 - Ruault, P., 2009. Ecole d’architecture, Nantes. [image] Available at: <https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=55> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

Fig 19 - Lacaton & Vassal, 2009. Architectural Drawings - Nantes School of Architecture. [image] Available at: <https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=55> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

Fig 20 -Ruault, P., 2009. Ecole d’architecture, Nantes. [image] Available at: <https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=55> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

Fig 21 - Ruault, P., 2009. Ecole d’architecture, Nantes. [image] Available at: <https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=55> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

Fig 22 - Foundation for Young Australians, 2017. Growing demand for enterprise Skills. [image] Available at: <https://www.fya.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/The-New-Basics_ Update_Web.pdf> [Accessed 18 September 2021].

Fig 23 - Deloitte, 2016. The path to prosperity: Why the future of work is human. [image] Available at: <https://images.content.deloitte.com.au/Web/ DELOITTEAUSTRALIA/%7B90572c4f-4bb5-4b54-bf27-cc100d86890d%7D_20190612-btlc-inbound-future-work-human-report.pdf?utm_source=eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_ campaign=20190612-btlc-inbound-future-work-human&utm_content=body> [Accessed 18 September 2021].

Fig 24 - Noonan, S., 2019. The vertical school where the building is a learning tool. [image] Available at: <https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/projects/education-research/verticalschool-adelaide-botanic-high> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Fig 25 - Benschneider, B., 2013. Rosa Parks Elementary School in Lake Washington School District. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/326114/the-8-things-domesticviolence-shelters-can-teach-us-about-secure-school-design> [Accessed 14 September 2021]. (Deloitte, 2016)

Fig 26 - Noonan, S., 2019. Adelaide Botanic High School. [image] Available at: <https://www.coxarchitecture.com.au/project/adelaide-botanic-high-school/> [Accessed 22 August 2021].

Fig 27 - Clarke, P., 2011. Flexible spaces at Alkira Secondary College by Hayball and Gray Puksand. [image] Available at: <https://architectureau.com/articles/beyond-theclassroom/#img-1> [Accessed 22 August 2021].

Fig 28 - Sydney Secondary College, Leichhardt, 2017. VR Immersion day. [image] Available at: <https://www.flickr.com/photos/123663364@N03/39013146251/> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 29 - Sydney Secondary College, Leichhardt, 2019. School Captains 2019. [image] Available at: <https://www.flickr.com/photos/123663364@N03/33112743518/> [Accessed 1 November 2021].

Fig 30 - Bennetts, P., 2019. New Museum for Western Australia / Hassell + OMA. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/930564/new-museum-for-western-australia-hassellplus-oma> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 31 - Bennetts, P., 2019. New Museum for Western Australia / Hassell + OMA. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/930564/new-museum-for-western-australia-hassellplus-oma> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 32 – Bennetts, P., 2019. New Museum for Western Australia / Hassell + OMA. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/930564/new-museum-for-western-australia-hassellplus-oma> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 33 Kennedyand, S., n.d. Believe in Better Building. [image] Available at: <https://archello.com/story/36143/attachments/photos-videos> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 34 - Kennedyand, S., n.d. Believe in Better Building. [image] Available at: <https://archello.com/story/36143/attachments/photos-videos> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 35 – Kennedyand, S., n.d. Believe in Better Building. [image] Available at: <https://archello.com/story/36143/attachments/photos-videos> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 36 - Nuno Pacheco, P., n.d. Dos Platanos School. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/885993/dos-platanos-school-murmuro?ad_medium=gallery> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 37 - Partee, J., n.d. College of Forestry. [image] Available at: <https://www.archivibe.com/new-mass-timber-buildings-for-the-college-of-forestry/?fbclid=IwAR2VocHi3EtSBymzDMo uAccwqZG-w6itdgXojWQ7fltoDk6c7gOy4-uBpEI> [Accessed 19 September 2021].

Fig 38 - Gardiner, R., 2019. SERIE ARCHITECTS SCHOOL OF DESIGN AND ENVIRONMENT. [image] Available at: <https://divisare.com/projects/410778-serie-architects-rory-gardinerschool-of-design-and-environment> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 39 – Fennessy, S., 2019. Breathable mesh facade. [image] Available at: <https://www.dezeen.com/2019/03/30/nth-fitzroy-apartment-melbourne-interiors-fieldwork-flack-studioaustralia/> [Accessed 12 October 2021].

Fig 40 - Wulf Arkitekten, n.d. DZNE German Center for Neurodegenerative Disease. [image] Available at: <https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/louvers/> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 41 - Wulf Arkitekten, n.d. DZNE German Center for Neurodegenerative Disease. [image] Available at: <https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/louvers/> [Accessed 8 October 2021].

Fig 42 Caulfield, J., 2017. Pre-fabricated Panel. [image] Available at: Mass timber: From ‘What the heck is that?’ to ‘Wow!’ | Building Design + Construction. [online] Bdcnetwork.com. Available at: <https://www.bdcnetwork.com/mass-timber-what-heck-wow>

Fig 43 - Lendlease, 2016. Ironbark Column Arrangement, Cross Section, Fabrication, Finish. [image] Available at: <https://www.forum-holzbau.com/pdf/29_ IHF_2016_Butler.pdf> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 44 - Lendlease, 2016. Pre-Assembled Lift Core, Braced Bay Lifting, and Installed Braced Bay. [image] Available at: <https://www.forum-holzbau.com/pdf/29_ IHF_2016_Butler.pdf> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 45 Guthrie, B., 2017. Photo of Interior. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/871807/international-house-tzannes> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 46 - Thompson, R., 2017. HESS TIMBER Composite Beams. [image] Available at: <https://www.hess-timber.com/en/references/detail/international-housesydney/> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 47 - Guthrie, B., 2017. Photo of Meeting Space. [image] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/871807/international-house-tzannes> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

Fig 48 - Thompson, R., 2017. HESS TIMBER Composite Beams. [image] Available at: <https://www.hess-timber.com/en/references/detail/international-housesydney/> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

ABS Census Data. 2017. 2016 Census QuickStats. [online] Available at: <https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/ quickstat/SSC13715?opendocument> [Accessed 16 August 2021].

Adelaide Botanic High School. n.d. Adelaide Botanic High School. [online] Available at: <https://abhs.sa.edu.au/> [Accessed 23 August 2021]. Alexander, C., 1990. A pattern language. München: Fachhochsch., Fachbereich Architektur.

ArchDaily. 2012. Nantes School of Architecture / Lacaton & Vassal. [online] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/254193/nantes-school-of-architecturelacaton-vassal?ad_source=search&ad_medium> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

ArchDaily. 2017. International House / TZANNES. [online] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/871807/international-house-tzannes> [Accessed 27 August 2021].

ArchDaily. 2017. Dos Plátanos School / Murmuro. [online] Available at: <https://www.archdaily.com/885993/dos-platanos-school-murmuro?ad_medium=gallery> [Accessed 8 October 2021].