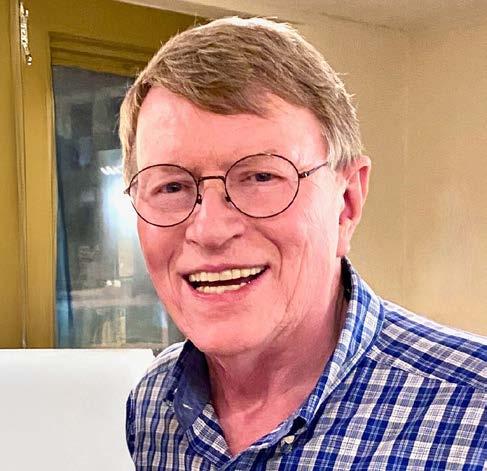

Keith Barnacastle • Publisher

Richelle Putnam holds a BS in Marketing Management and an MA in Creative Writing. She is a Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC) Teaching Artist, two-time MAC Literary Arts Fellow, and Mississippi Humanities Speaker. Her fiction, poetry, essays, and articles have been published in many print and online literary journals and magazines. Among her six published books are a 2014 Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards Silver Medalist and a 2017 Foreword Indies Book Awards Bronze Medal winner. Visit her website at www.richelleputnam.com.

Rebekah Speer has nearly twenty years in the music industry in Nashville, TN. She creates a unique “look” for every issue of The Bluegrass Standard, and enjoys learning about each artist. In addition to her creative work with The Bluegrass Standard, Rebekah also provides graphic design and technical support to a variety of clients. www.rebekahspeer.com

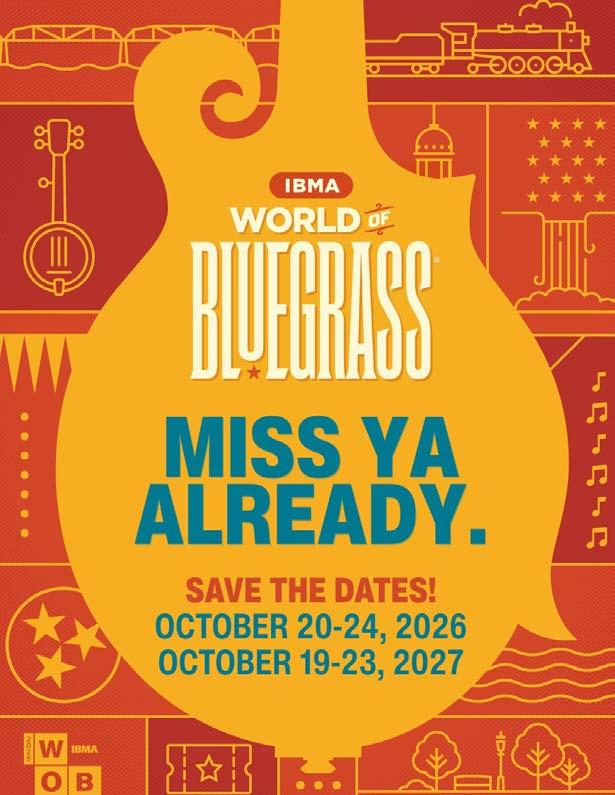

Susan traveled with a mixed ensemble at Trevecca Nazarene college as PR for the college. From there she moved on to working at Sony Music Nashville for 17 years in several compacities then transitioning on to the Nashville Songwritrers Association International (NSAI) where she was Sponsorship Director. The next step of her musical journey was to open her own business where she secured sponsorships for various events or companies in which the IBMA/World of Bluegrass was one of her clients.

Susan Marquez is a freelance writer based in Madison, Mississippi and a Mississippi Arts Commission Roster Artist. After a 20+ year career in advertising and marketing, she began a professional writing career in 2001. Since that time she has written over 2000 articles which have been published in magazines, newspapers, business journals, trade publications.

Singer/Songwriter/Blogger and SilverWolf recording artist, Mississippi Chris Sharp hails from remote Kemper County, near his hometown of Meridian. An original/founding cast member of the award-winning, long running radio show, The Sucarnochee Revue, as featured on Alabama and Mississippi Public Broadcasting, Chris performs with his daughter, Piper. Chris’s songs have been covered by The Del McCoury Band, The Henhouse Prowlers, and others. mississippichrissharp.blog

Brent Davis produced documentaries, interview shows, and many other projects during a 40 year career in public media. He’s also the author of the bluegrass novel Raising Kane. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Kara Martinez Bachman is a nonfiction author, book and magazine editor, and freelance writer. A former staff entertainment reporter, columnist and community news editor for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, her music and culture reporting has also appeared on a freelance basis in dozens of regional, national and international publications.

Candace Nelson is a marketing professional living in Charleston, West Virginia. She is the author of the book “The West Virginia Pepperoni Roll.” In her free time, Nelson travels and blogs about Appalachian food culture at CandaceLately.com. Find her on Twitter at @Candace07 or email CandaceRNelson@gmail.com.

A Philadelphia native and seasoned musician, has dedicated over forty years to music. Starting as a guitar prodigy at eight, he expanded his talents to audio engineering and mastering various instruments, including drums, piano, mandolin, banjo, dobro, and bass. Alongside his brother, he formed The Young Brothers band, and his career highlights include co-writing a song with Kid Rock for Rebel Soul.

Stephen Pitalo has written entertainment journalism for more than 35 years and is the world’s leading music video historian. He writes, edits and publishes Music Video Time Machine magazine, the only magazine that takes you behind the scenes of music videos during their heyday, known as the Golden Age of Music Video (1976-1994). He has interviewed talents ranging from Ray Davies to Joey Ramone to Billy Strings to Joan Jett to John Landis to Bill Plympton.

by Susan Marquez

“Brian Lillie here, playing some hot rockin’ bluegrass hits for ya tonight on the Pickin’ and Fiddlin’ Show on Torrington Community Radio.”

Once again, Brian Lillie signs on the air on WAPJ-FM, as he does every Wednesday evening from 7 to 9 p.m. The station is in downtown Torrington, Connecticut, and it’s the city’s only station hyper-focused on the community. The non-profit, non-commercial station was started by dedicated volunteers and is still staffed by volunteers. Listener donations and business sponsors support the station.

Depending on what time you tune in to the station, which is also accessible via their website at wapj.org, you might hear classic rock, pop, jazz, soul, country, reggae, blues, or even radio theatre, but the Wednesday evening slot is dedicated to bluegrass, and Brian has made it his mission to bring the best in bluegrass to his listeners, week after week. From old standards to more progressive styles, Brian works to create the ideal mix of music on his weekly broadcast. He even plays a little “bluegrass adjacent” music from time to time for fun and perspective.

“To tell you the truth, there is no real plan,” he laughs. “It’s more intuitive with me. We don’t have a program director dictating what I have to play, so it’s purely up to me.” He has done theme shows, such as playing train or coal mining songs. “I will play bluegrass Gospel before Easter, and on St. Patrick’s Day, I’ll start with Tim O’Brien’s ‘The Crossing,’ then play a bunch of Irish music. And of course, bluegrass Christmas during the holidays. I do it just because it’s fun.”

Brian grew up in Chicago and listened to the

blues while all his friends listened to The Beatles and the Beach Boys. He attended graduate school at Indiana University and stayed to teach high school after graduation. “In 1980, some of my students volunteered at Bill Monroe’s Bean Blossom Jamboree, and they got me an armband.” The festival spans two weekends with the entire week in between. “I had planned to go one time to see what it was all about, and I ended up going every day. I was completely amazed. They were playing what my mom had once called ‘hillbilly music,’ and I loved it.”

Brian saw groups like the McLain Family Band and Birch Monroe, Bill Monroe’s older brother. “He was in his early 90s when I saw him,” says Brian. “I once saw Birch and Bill arguing, like brothers do, just off the stage. The festival was held on Birch’s land, but Bill ran the show. It was probably a little dispute about the festival, but I thought it was fun seeing them interact as siblings at their age.”

After attending that festival, Brian was hooked on bluegrass. “It was not just the music, but the culture around it. There were bonfires out in the fields, and all the fiddlers would play around one, mandolins would play at another, and so on. Then the stars would come out of their trailers and join them. Everyone was so friendly and accessible.”

After flying to Connecticut for a wedding and getting a job offer while he was there, Brian picked up stakes and moved to the northeast. He volunteered to work the phones for a fundraiser at WPKN in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and he began hanging out at the station during Chris Teskey’s show (Teskey now has a show five days a week on Bluegrass

Country radio). “I eventually started reading news at the station and auditioned to have my own show, but they wanted me to work the 10 pm to 2 am slot, and I had to get up and teach the next morning.” He did work his way to being chairman of the station’s Board of Directors.

After moving one town over, Brian discovered WAPJ. “They played cool stuff, so I contacted them, and they made a slot for me on Wednesdays, and I’ve been there ever since.”

I met Brian at the 2024 IBMA “World of Bluegrass” event in Raleigh. Over coffee, we learned that we both loved sharing bluegrass – Brian on the radio, and I writing for The Bluegrass Standard. He was able to attend IBMA for the first time in 2023 after he retired from teaching. “It’s been great for the show because I can hear so many bands. It’s fun to discover new talent, like a band from Los Angeles called Water Tower.” (I also discovered Water Tower at IBMA and wrote about them for our April 2025 issue.) “Most of the record companies know about us now, so I get new music all the time, which is great. I probably have 3,000 to 5,000 CDs in my closet that I pull from for my show.” He keeps music released within the past year separate, as he is a reporting station for Bluegrass Unlimited.

Brian also hears both old and new bands at the many festivals he attends. “I have been a judge at the local fire department’s annual pickin’ contest for thirty years and also volunteer in the merchandise tent at the Grey Fox Bluegrass Festival. “I know the artists and their music, so it’s a natural fit for me to sell merchandise. My wife and daughter also volunteer, so it’s a fun family event.” Brian also volunteers at the annual Podunk Festival, which he says is getting better and better each year.

Brian hopes to introduce quality bluegrass music to anyone who dares to listen through

his radio program. “I tell folks that bluegrass is what country music could be if it were really cool. Big country music artists are usually surrounded by entourages, and they are put on a pedestal. Bluegrass artists are so approachable, and they are such nice people. It’s easy to build personal relationships with them, and I’ve had the honor of making a lot of friends in this industry. I love doing this.”

by Jason Young

“We were asking the big questions,” says thirty-three-year-old Them Coulee Boys lead singer Soren Staff, about their latest LP, No Fun in Chrysalis. “This record was coming from a place where there were huge changes for me and the band.”

The project felt change-oriented, explains Staff. “I was trying to figure it all out. I was getting to the point in life where I’m asking myself, ‘Is this what I want to do?”

The band agrees that live streaming poses a financial challenge. “Distributing art to the masses often leaves the artist out of the rewards for success. This is the reality artists face these days.”

Releasing their self-titled EP in 2013, the Eau Claire, Wisconsin band celebrates a varied musical background.

“We started out as a string band—just banjo, mandolin and guitar,” recalls Staff, whose friendship with banjoist Beau Janke led them to recruit his younger brother Jens Staff on mandolin.

Adopting drums and electric instruments, the band, Staff points out, wasn’t afraid to evolve. “We listen to what the songs are telling us in terms of style. We are very open to all kinds of sounds.”

Bassist Neil Krause and drummer Stas Hable add their unique qualities to the mix. “Neil was kind of a punk rock kid in high school, and Stas is Czechoslovakian. He has a lot of cool Czech folk roots but is also into metal and dance-pop. He is our secret weapon when it comes to getting new sounds into our music because he listens to everything.”

To expand their sound on the album, the band enlisted the help of session musicians. “The coolest part about [No Fun In Chrysalis] was that we had some friends come play

fiddle and peddle steal,” the guitarist shares. “We had some fun synthesizer sounds on the record, too. We always wanted to have that kind of musical tapestry.

“With each album, I like to come to the guys with something that feels like it really challenges us, be that sound-wise or message-wise. ‘Ghosts (In 4 Parts)’, for example, took a whole lot of arranging.”

Staff says the song serves as a stark warning about conservation. “It’s like, hey, if we don’t do what we can do now to fix this, we’re not going to have a world to live in. It’s one of my favorite songs on the record.”

Keeping it all together was Grammywinning producer Brian Joseph.

“This is the second record we made with Brian. We grew very close over that first album, Namesake.” Staff says they felt more confident with No Fun in Chrysalis. “In the past, we deferred to him, knowing who he was, but this time we took more agency as songwriters. His superpower is making you comfortable. If we did a couple of takes that didn’t feel right, he would say, ‘Hey, let’s go take a lap,’ and we would walk on the trails outside of his studio.”

Recording at The Hive in Eau Claire, Staff shares the band’s deep connection to the city. “That is where we were playing our first shows. So many musicians have their roots in Eau Claire.”

“We all grew up in small little towns in nowhere Wisconsin [Jokes]. Eau Claire is the closest metropolis. It was around the time Bon Iver was blowing up, and other bands from Eau Claire were seeing more success.”

Going on, “It’s more musically collaborative than competitive there,” shares Staff who loves Eau Claire’s vibe. “We thought,

‘We’ve got to move to Eau Claire—that’s the place to do it!’”

Still holding a day job, the guitarist says the music business is tough.

“The access to music has never been higher, which is incredible, but the compensation for the work as a musician has never been lower. There’s no insurance, there’s no safety net.” Them Coulee Boys plan to face the challenges ahead.

“I think the business forces you to constantly evaluate if you’re doing enough, especially if you’re raising a family. But the reality of this is that as artists, we find a way. We want to do this because it’s fulfilling, joyful, and meaningful. I can’t speak for all of us, but I don’t think I’ll ever ‘quit’ music. It’s an extension of the way I navigate the world— and there’s no part of me that ever wants to cut that out.”

by Susan Marquez

Enda Scahill started playing music at an early age in rural Ireland. “Where I grew up in Galway, on the west coast, most Irish children played the tin whistle in school from age five or so,” he says. “When I was about nine years old, a wonderful music teacher called Bernie Geraghty came to my school. She asked if anyone would like to play the banjo, and my hand shot up into the air. I don’t know why I was instantly attracted to the banjo, and I don’t have a clear memory of where I first heard it. But I remember that day. I was the first-ever banjo player in our village.”

Bernie taught Enda for a few years before Cepta Byrne began teaching music at his school. “Cepta played accordion, but she was one of those beautiful humans who wove magic and joy into music and just inspired me to be creative, brave, and innovative in my approach to Irish music,” Enda says. “She didn’t believe in musical boundaries and thus, neither did I. Cepta is in her 70s now, and almost 40 years later, she’s one of my closest friends and confidants.”

In addition to his music education at school, Enda grew up in a musical family. His older brother, Adrian (who now has two master’s and a doctorate in Irish music and lectures on Irish music at a national university), was a huge collector of Irish tunes, even as a young teenager. So he would sit for hours at the piano transcribing tunes he had recorded at local music (jam) sessions. I learned most of my tunes by osmosis from him. Hence, I am still terrible at remembering tune names.”

Enda admits he is not great at studying. “Sitting and concentrating has always been a struggle for me, so I soak up music by listening, experimenting, and lots of playing.” His biggest musical hero was Gerry O’Connor (the first Irish winner of the Steve Martin Banjo Prize, incidentally). “Gerry was so incredibly inventive in his playing, drawing from many different genres and pushing the technical boundaries of the instrument. As a teenager, his music drove me to be better, faster, cleaner, and even more musically experimental.”

A four-time All-Ireland banjo champion, Enda was presented with the prestigious Steve Martin Banjo Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass in 2022. “It came at a difficult time as We Banjo 3 was winding down, and my musical future suddenly looked very uncertain. I’m a firm believer in a higher power or “the universe,” and that felt like a giant cosmic reassuring hand on my back.

He performed with numerous groups before founding “the hottest group in Irish music,” according to LiveIreland, We Banjo 3, with Martin Howley, David Howley, and his brother, Fergal Scahill. “We started We Banjo 3 in my kitchen in 2009 because I was inspired by a photograph I saw of Kris Kristofferson on stage with his head thrown backwards, laughing deeply. Irish music can be very serious, and I desperately wanted to have fun. I also wanted to be a little controversial and poke at the establishment. What better way than a band with three

banjos? I was determined to stand out from the crowd. Every other band at that time was some Celtic-sounding word, and I knew we had to be very different. But it was only ever supposed to be a bit of fun on the side. Who knew so many people loved the banjo? People came out in droves. At first, we didn’t have enough music to fill a 90-minute show, so we told lots of jokes and stories to fill the gaps. And audiences loved the show! Looking back, we were running to catch up from 2012 to 2019. It took off like a juggernaut. I think we had reached a level of stability in 2020, having taken on management and all of the support systems that brings. But we know what happened in 2020.”

Over the years, Enda says he has been blessed to play with so many amazing musicians. “Even thinking about it blows my mind. I’ve traded solos with Bela Fleck, Alison Brown, and Jake Workman, and I recorded an album with Ricky Skaggs, Aubrey Haynie, and Bryan Sutton. I could go on and on. Sierra Hull, Sam Bush, Ron Block, even Billy Strings. Sometimes it doesn’t feel real.”

A career high happened a few years ago, when Enda stood on stage in the Sumida Triphony Concert Hall in Tokyo with two of the greatest Irish music bands of all timeDervish and Altan. “There were 1800 people in the audience, clapping and smiling, and I realized that these bands were the late night, walking home from the session, headphones in (Walkman cassette tape era!) soundtrack to my youth. And here I was sharing a stage, music, laughter, and friendship with my heroes. That moment on stage, my heart swelled and I had tears in my eyes with gratitude for all the gnarly twists and turns of life that had led me there.”

back when I didn’t know anything about bluegrass music, I inveigled myself (through pure brazenness) onto the mainstage at a big bluegrass festival in Ireland. I managed to nab a 10-minute slot between headliners. We went up, blitzed the set, scarpered off stage to a standing ovation, and ran back across the road to the pub where we were hired to play our own gig. What I never realized is that Earl Scruggs and his band were the headliners that night, and after their show, they came across the road and watched the rest of my gig.”

His inspiration changes all the time and many times. “Right now, Bela Fleck is a huge inspiration for this reason - he has constantly innovated, seemingly without any fear of limitations of genre or ability. So, when I’m feeling musically humdrum or technically stuck, I think of Bela. And it lifts me to try different runs or ornaments in the music. I’m probably unusually annoying in an Irish jam session context as I’m then wandering way off the melody of the tune at times.”

Martin Hayes, the Irish fiddler, has also been a huge inspiration. “He communicates something profoundly moving with deceptively simple playing. And a jazz pianist called Kenny Werner. He wrote the book Effortless Mastery. I watched a seminar of his a few years ago. He sits at the piano, and before he plays, he always says to himself, ‘This is the most beautiful sound I have ever heard anywhere in the universe,’ and then plays. Goose bumps every time.”

Enda also shared another funny tale: “Way

Now Enda spends time teaching. “I love teaching. I only do things that I’m wildly passionate about. Otherwise, I get wildly bored very quickly! Irish banjo can be a tough instrument. Chris Thile once said that the mandolin is an incredibly inefficient

instrument. Well, tenor banjo is that by ten. So I formulated a method of playing that simplifies and describes in detail a pedagogy that works for the banjo. And I’m inspired and excited to help other people become better banjo players and all-round better musicians.”

Enda has a vast online community of students on every continent. “Over 700 currently, and I interact with many of them on a regular basis. Essentially, what I do now is create bespoke high-level, high-tech, multi-camera angle banjo and mandolin lessons. Every lesson is tailored to all levels of ability,

from absolute beginner right up to advanced players. I focus on all the various aspects of technique, constantly challenging students to learn new ideas, ornamentation, harmony, and variations. It’s very immersive and comprehensive.”

But there is plenty of music in Enda’s fingers. “I’ve just released the best album I’ve ever made. Bearing in mind several Billboard #1 albums and many Album of the Year awards, I think that is saying something! The Dark Well is a collaboration with a Swedish harmonic player called Joel Andersson, who incidentally is the number one customizer of

high-end harmonica in the world. The album title is a play on the phrase ‘Drinking water from an ancient well’ - the concept of the deep and sustaining heritage of Irish traditional music. However, the banjo and harmonica are new interlopers. We don’t fully belong in this ancient well. We need to dig our own well. It’s dark and sonorous. Full of texture, drones and gravely banjo sounds. It’s truly unique and different.”

Guests on the album include Grammy winner Francesco Turrisi, Ross Holmes from Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Andy Thorn from Leftover Salmon and many more. “I’m

also touring for the last year with an Italian band called Gadan, who, if you can believe the irony, now have three banjos in the band. They play a high-energy blend of Irish and bluegrass music. It’s a ton of fun and I’m really enjoying playing with the guys.”

Bluegrass came along as a new calling for career musician and classically trained upright bassist Trish Imbrogno. She’d already spent 25 years with her instrument, performing with classical ensembles and symphony orchestras and gracing the stages of prestigious venues such as Carnegie Hall.

Even after all that, the allure of roots music caused her to take an unexpected turn.

“I don’t think I knew what I was missing until I found it,” Imbrogno explained. “When you’re in the classical world, the path is very prescribed – hours in a practice room with Simandl and Flesch, mastering solo rep and excerpts, all aiming for that orchestra job with steady weeks and a salary. That was my world for a long time, and I didn’t really question it. I didn’t even realize there was another way to make music professionally.”

That started to shift after Imbrogno began playing with her partner, who’s a fingerpicking guitarist in the style of Mississippi John Hurt and Blind Blake. She explained, “We were gigging regularly as a duo, and through that, I found my way into the broader Americana scene.”

She was invited to bluegrass night at The Park House, a tiny bar in her Pittsburgh, Penn home base. She said it was so small, she had to lift her hand-carved, one-of-a-kind bass over people’s heads “just to squeeze in the back corner.” It was a scene of “no mics, beer flying, people jumping around inches from us, and no idea what I was doing…but it was electric and became a weekly thing for five years.”

Over time, she started booking so many roots gigs that her calendar was already full; the orchestral work was crowded out. She preferred the more enjoyable bluegrass events.

“I didn’t feel burned out preparing that material,” she said. “In fact, I was excited about it. Meanwhile, every time I pulled orchestral music out of the folder, I’d sigh. That’s when it hit me: Maybe I don’t love this the way I thought I did. Or maybe I never really did – I just didn’t know any other path existed.”

What she found in bluegrass and Americana was connection. “In classical music, you’re making this beautiful, intricate art, but the audience is silent, reverent, hands in their laps. In roots music, the audience gives you energy in real time,” Imbrogno summarized. “You feel it. They clap, laugh, yell, and come talk to you after the show. It’s not always about perfection; it’s about people. And I realized I’m someone who needs that.”

In addition to her gigging with Pittsburgh-based Sweaty Already String Band, she’s just released her debut album, Bluegrass Love Songs, Volume One. She said it is “built around a bit of an inside joke I’ve made for years.”

Calling something a bluegrass love song is kind of an oxymoron, Imbrogno said. “The melodies might sound sweet, but the lyrics usually tell a darker story. I started saying onstage that I only sing ‘Volume One’ love songs – the ones where everybody stays alive at the end…these are the heartbreak tunes…getting dumped, cheated on, left behind. Still sad, but nobody gets murdered.”

It is with this humor and clear love for bluegrass that Imbrogno was guided in selecting numbers for the EP, which includes songs such as the locally beloved tune “Cherokee Shuffle” and what she described as the “love-hate” song “Clinch Mountain Backstep.”

The experienced team Imbrogno assembled for the record includes Murphy Henry (banjo and vocals on one track); Dede Wyland (guitar and harmony vocals); Rainy Miatke (mandolin); and Becky Buller (fiddle). Christopher Henry recorded and engineered the album, with additional recording work by Ben Surratt and Mark Raudabaugh, and mastering by Will Shenk.

Imbrogno is really excited about this deeper new step into the bluegrass world.

“I didn’t make this record because I want to be a front person or start my own band. I love being a side person, and I’ve been fortunate to play on a lot of records across different genres,” she said. “But most of those don’t show up when you search for me. So, part of this project was about visibility – making sure people can actually find me if they’re looking for a bluegrass bass player. And part of it was proving to myself that I could do it.”

She acknowledges the inspiring examples set by others and credits her main mentor in the classical world, her bass teacher, Jeff Turner. Imbrogno said she has found inspiration and mentorship in Missy Raines, whom she described as “an incredible player, teacher, and human.” She also cited other women of roots music, including Dede Wyland, Becky Buller, Vickie Vaughn, Shelby Means and Molly Tuttle.

While she believes women performers of all stripes are a powerful bunch, Imbrogno attempted–quite thoughtfully–to explain the unique features of being a female bassist.

“The upright does have something special,” she explained. “You’re basically wrangling a full-sized human when you play it. There’s a physicality, a kind of grace-meets-power. And when someone really plays the upright – when their technique is dialed in, especially with a bow – it’s like a dance. It becomes an extension of the body. That instrument moves with you. It breathes with you. And that’s something you don’t get with a fiddle, or a guitar, or even an electric bass.”

She said when people see a woman onstage wrangling a bass, they see a “powerful visual of a woman completely in sync with an instrument that takes up space…unapologetically.”

by Brent Davis

After many years on the road—she was with the circus, he hopped freights—husband and wife Keith Josiah Smith and Sparrow Smith, who perform as The Resonant Rogues, have put down roots.

“We live in Western North Carolina,” says Sparrow. “It’s one of the most beautiful natural places in the world. People can come here from all over the world to experience nature here. We’re so lucky to have it in our backyard.”

But as The Resonant Rogues, Sparrow and Keith—sometimes performing as a duo, other times fronting a larger band—maintain a busy tour schedule, playing many songs from their two latest albums, The Magnolia Sessions and the eponymous The Resonant Rogues.

“We love touring for the most part,” says Keith. “Like everything else there’s things that are not enjoyable, but that’s just life. We like traveling and playing music. I feel like going and playing the shows is the easiest part. Everything else is kind of more of the hard work.”

Sparrow plays the banjo and accordion, and Keith plays guitar and percussion. Both sing and are prolific songwriters. Old-time music associated with Western North Carolina is a big part of their musical identity, and being on the move is in their DNA.

“What brought Keith and I together was our love of adventure and our love of travel,” Sparrow explains. “We’ve done a lot of international traveling through the years. We’re really hoping to get back to Europe to tour. We toured Europe three different times prepandemic. We also toured Australia, and we’ve been to Alaska four times. We just really love traveling.”

Last winter, Sparrow and Keith made a bucket list trip to South America to explore the music there. Living in the mountains, they feel a kinship with folk music from other countries tied to mountain culture.

“One of my life dreams is to spend more time in Cusco, Peru, up in the mountains and do kind of a musical exchange where I learn music, teach and share music. There’s a lot of similar instruments, especially with the accordion and the fiddle. And the people are just so friendly and kind, and the music is so great.”

Much of The Resonant Rogue’s material is either old-time fiddle tunes or original compositions, but the songs may get a widely varied treatment. The Magnolia Sessions album was recorded with just the two playing and singing as they sat under a tree.

“It was right during the pandemic, so it was kind of a neat time for trying new things,” Keith remembers. “And the whole point of it was to do a stripped-down, intimate, simple acoustic set of songs. It was all one take with no break. So essentially, it’s a live album in

A. P. Carter Highway, Hiltons, VA 24258

@carterfamilyfold

Kody Norris Show

November 1 | 7:30 pm

ETSU Old Time Ramblers

November 8 | 7:30 pm

Russell Moore & IIIrd Tyme Out

November 15 | 7:30 pm

Whitetop Mountain Band

November 22 | 7:30 pm

Carson Peters & Iron Mountain

November 29 | 7:30 pm

For more information

Scan the QR Code

On the other hand, their self-titled album has a fuller sound, with electric guitars, percussion, fiddles, and guest vocalists, including Sierra Ferrell.

“That was a really special thing to get to do, and we are really happy with how that turned out sound-wise,” says Sparrow. “We love to dance, we love to make people dance and so being able to do that with full bands and to get drums in there was really a good time. And I’d say that that’s true of our shows as well. We go from kind of a string band to a country dance band feel.”

This fall, Sparrow released a solo banjo album, Carolina Mountain, which Keith produced.

“I write a lot of songs, and I had a vision for a banjo-focused record that was about Southern Appalachia and Western North Carolina. It had a very strong sense of place,” Sparrow says. “Honestly, all of them would feel at home on a Resonant Rogues album in some way, but this record was my vision and was all my songs.”

Don’t expect to find them there just because they’re firmly attached to their adopted home (Sparrow grew up in Colorado; Keith in Wisconsin). The road beckons.

“We have a pretty big year of Resonant Rogues touring mostly around festival dates, and then we’re going to do a big national album release tour for the Sparrow Smith record,” Sparrow says. “That will be billed as Sparrow Smith and The Resonant Rogues, so Keith will be on the whole tour. We’ll have some other musicians join us for sections of it. We’re going across the South, going up the West Coast and popping down into Colorado. And then probably touring the rest of the country throughout the year with the new record.”

While this pair of seasoned travelers enjoys many experiences touring offers, Keith observes that the bond between performer and audience member drives them.

“I feel like live music shows can be therapeutic for people with our modern lifestyles,” he says. “What probably feels the best to me when I talk to people at the end of a show is when they get something out of it in that human way of connection. I think that’s something that you can’t get on your phone. You can’t get that on social media. You can’t get that anywhere else. It really is one of the very few places where you can get that level of connection.”

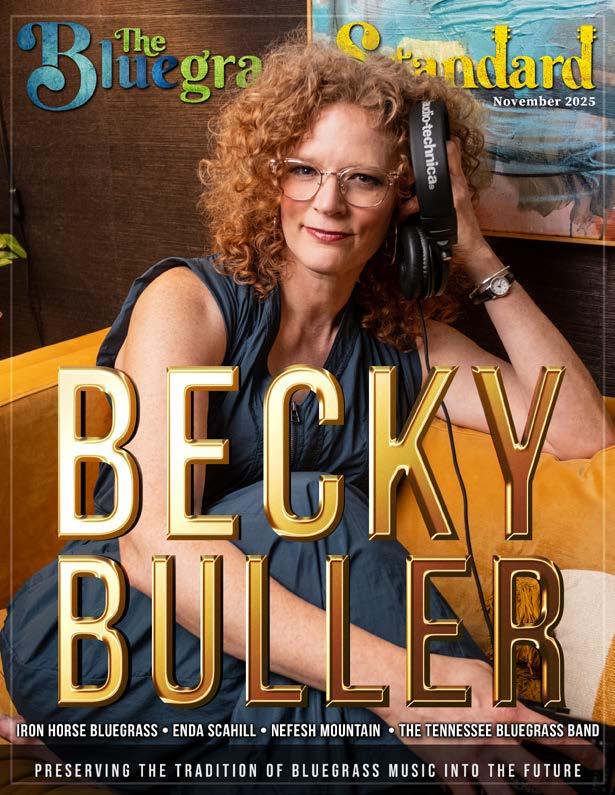

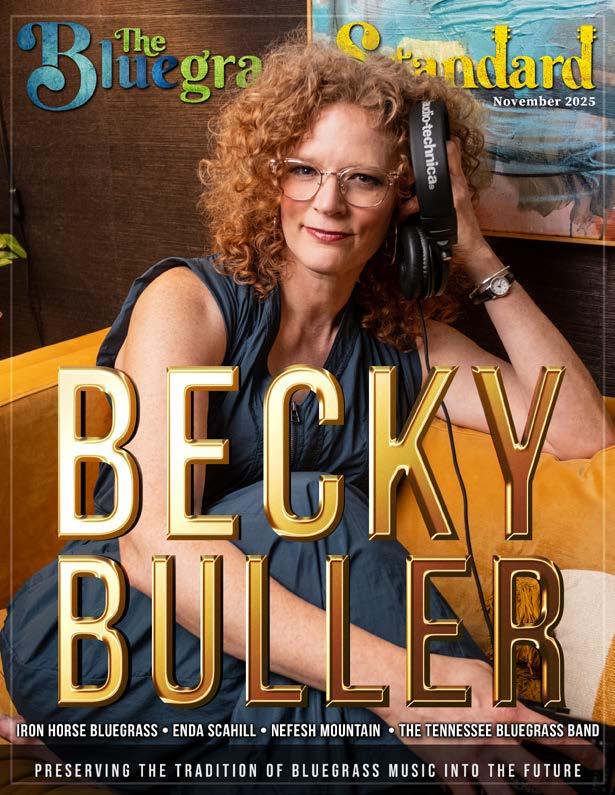

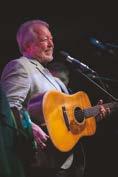

by Stephen Pitalo

A native of St. James, Minnesota, who proudly settled in the Tennessee town of Manchester, Becky Buller has been stacking up accolades for years. She’s the first woman to win IBMA’s Fiddler of the Year, and the only artist to take home both Female Vocalist and Fiddler in the same year. Her songs have been recorded on three Grammy-winning bluegrass albums, including Laws of Gravity by The Infamous Stringdusters, The Travelin’ McCourys, and Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway’s Crooked Tree. And in 2023, she was inducted into the Minnesota Music Hall of Fame. But Becky Buller isn’t chasing acclaim. She’s chasing the truth.

Her latest release, Songs That Sing To Me, arrives on the heels of Jubilee, a soul-baring song cycle tracing her experience with depression and anxiety during the pandemic years. That project was raw and revelatory. This one glows with perspective.

“Sharing my story, baring my soul to the world by way of Jubilee was very liberating,” she said. “It literally parted the waters of the musical pool that was coalescing into Songs, leading me to a place of greater peace and abundance.”

The roots of this new album go back to 2022, when Buller first began production—only to hit pause when the FreshGrass Foundation offered her a commission. That commission bloomed into Jubilee, and once finished, she returned to the Songs That Sing To Me sessions with renewed energy.

“I hear a clear delineation between the two halves of this new album. Once on the far side bank of Jubilee, I dug down deeper, exploring my voice, fiddle, and arrangements in ways I had previously thought beyond my reach.”

And unlike her past solo records—almost entirely filled with original songs—she inhabits someone else’s creations.

“Songs That Sing to Me is my first all-covers project,” she explained. “The title actually comes from ‘The Magician’s Nephew,’ the creation allegory in C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia series. In it, the great lion Aslan is literally singing the land of Narnia into being. That’s what these songs are doing for me; they continue to inspire and inform my own creativity.”

She and longtime producer Stephen “Mojo” Mougin cooked the soup from a large pot, letting the music shape the sound and the theme.

“Stephen and I always start a new album with a mile-high stack of songs,” she said. “The song choices inform our creative direction—traditional versus progressive bluegrass; oldtime; major, minor, modal; to banjo or not to banjo… I love to present a variety of keys, grooves, and subject matter, all in hopes of capturing the listeners’ imagination for the entirety of the album and beyond.”

She didn’t stop at interpreting these songs—she embedded them with the voices and hands of her friends, mentors, and family.

“I absolutely LOVE to collaborate in the studio with my friends and heroes,” Buller said. “The old-timey camp meeting song ‘Camel Train’ screamed The Whites and Ricky Skaggs. Lonesome Jim Lauderdale just about made me weep as we sang ‘Wall Around Your Heart’ together.”

She brought in her daughter Romy for a track alongside Béla Fleck, Abigail Washburn, and their sons Juno and Theo. Her “Muddy Waters” version featured two sons of The Seldom Scene. And “You Can’t Roll A Seven Every Time” turned into a family affair with her husband Jeff Haley, brother-in-law Timmy George, Mickey Harris (of Rhonda Vincent & The Rage), and Ned Luberecki.

“My fantastic band members, past and present, are all over this record,” she said. “Jake Eddy and Jacob Groupman, guitar; Daniel ‘The Hulk’ Hardin, bass; Wes Lee, mandolin; and Banjo Hall Of Famer Ned Luberecki.”

Inquiring minds can check out the album for a complete list of special guests. And for Buller, who’s spent over two decades teaching fiddle, singing, and songwriting in workshops around the globe—and now serves on the board of the IBMA Foundation—learning never stops. While making this record, she enthusiastically returned to the role of the student.

“Through the course of creating this album, I actually ‘went back to school’ for some fiddle and vocal coaching,” she said. “Thanks to Jason Carter, Michael Cleveland and Aynsley Porchak for added inspiration and taking the time to fiddle ‘nerd out’ with me. Thanks also to my opera-singing cousin, Samantha Friedman, who teaches at Wesleyan College in Macon, GA., for encouraging me to explore and expand my vocal capabilities.”

Songs That Sing To Me may celebrate the music that shaped her, but it’s also a declaration of where she’s standing now: a veteran artist still hungry for challenge, collaboration, and connection. Make no mistake, Becky Buller still has plenty to say.

While bluegrass continues to merge with other genres of music, bands like The Tennessee Bluegrass Band are dialing it back to its origins. After one album, an EP, and a handful of singles into their burgeoning career, their latest title track and LP, Nolichucky, further establishes the quintet’s knack for revitalizing a song.

Banjoist Lincoln Hensley spoke from his home in East Tennessee.

“We are super psyched! We’ll be releasing the full album sometime in July. This is the first album we produced all by ourselves,” shares Hensley about the band’s second LP.

“We’ve got some original songs on there and some that would be considered standards.”

Hensley says the band supports local Tennessee songwriters.

“We have songs on the album that were recorded fifty or sixty years ago by local East Tennessee and Western North Carolina bluegrass bands,” adding, “They never got airplay, so people never discovered them.

“Sometimes there is an absolute gem of a song that didn’t have the right finances or pushing behind it. We’ve got several songs like that on [Nolichucky]. We kind of breathe fresh life into the songs and put our own spin on them.”

The title track, “Nolichucky,” written by Leon Kiser, caused a visceral reaction.

“When hurricane Helene hit Appalachia last year, the town I live in was devastated. The river that runs through, called the Nolichucky, rose thirty feet out of its banks and flooded the area, killing six people.”

Continuing, “The song ‘Nolichucky’ was to us by local songwriter Charlie Powers,” Hensley, who says Powers wrote a song in the past as well as a gospel song on their album. “I thought [“Nolichucky”] had been about the hurricane Helene flood, but it was back in 1975 as a fictional song.

“Charlie came up to us and said, ‘Y’all got this,’ and he played the [Kiser] song, and it all over us!”

Founding members Hensley and mandolinist Laughlin have been with the band through iterations since forming in 2021. The banjoist the current lineup has strong chemistry.

“We got two brothers: Jacob Shefield Shefield. We also have Michael Feagen, who with Bill Monroe, playing fiddle.” Unlike past that needed more rehearsal, Hensley says fell right in. “From the word ‘go’ they were It’s the best lineup we’ve ever had!”

Hensley, who continues to gain notoriety banjo playing, reflects on his friendship with Sonny Osborne.

“He showed me a ton. He taught me almost catalogue of his music.” Sonny made Hensley promise. “He said, ‘If you get Flat & Scruggs’ Mountain banjo album and you learn that note, I will show you anything you want to

“I remember thinking, ‘If I could play that, need to know anything!’” [laughs]

Hensley recalls his parting lesson. “He told can play all my stuff now. You proved that. for you to start playing like you now.’ “He that next step. I’m so thankful that happened he passed.”

was pitched Powers,” recalls song for them their latest been written was written got to hear it sent chills

mandolinist Tim through its banjoist says and Josia who toured past lineups this lineup were ready! notoriety for his with the late almost the entire Hensley keep a Scruggs’ Foggy that note for to know.’

I wouldn’t told me, ‘You that. It’s time “He got me to happened before

Although the Tennessee native favors the older sounds of Lester Flat and Earl Scruggs, he’s happy that newer artists like Siera Hull and Billy Strings are bringing younger fans to bluegrass.

“Some of my heroes, like the Osborne brothers, were some of the biggest innovators in the world. A lot of traditional people probably looked down on them for using drums and pedal steel.”

As far as plans for moving forward, Hensley says one of his goals is to get The Tennessee Bluegrass Band on the Grand Ole Opry.

“These two younger boys, Jacob and Josia, never got a chance to play the Opry, and I would love for them to experience it.

“Mike and I played the Grand Ole Opry on different occasions. I got to play with Bobby Osborne and The Rocky Top X-Press, and Mike and Tim played with Bill Monroe and Jesse McReynolds. There’s nothing like it!”

Hensley says The Tennessee Bluegrass Band need the support of their fans to continue.

“The biggest support one could give us is to follow our social media and request our music to your favorite DJ, whether it’s SiriusXM or Banjo Radio. Ask for The Tennessee Bluegrass Band and that will help us big-time!”

by Richelle Putnam

Known for its storied recording history, Muscle Shoals, Alabama, is a major player in the music world. It is also home to a bluegrass band bending genres and surprising audiences for over two decades. Iron Horse.

“It has been said of this area, ‘There must be something in the water,’” says Vance Henry of Iron Horse. “There currently is and has been in the past a lot of music produced in Muscle Shoals, even in the bluegrass genre. We are proud of that heritage.”

They are also proud of contributing to the area’s music catalog through the influence and encouragement of people like Jake Landers, Rual Yarbrough, Jerry Clemmons, Steve Baccus, Dennis Clifton and groups like the Southern Strangers, The Adair Family, and The Dixie Gentlemen.

“These people performed for years, and it was great to have their encouragement. That encouragement helped us gain confidence in the early days,” Henry added.

From the beginning in 2000 to their latest project, Pickin’ On Creedence Clearwater Revival: Bluegrass Rising, Iron Horse formed a career from reimagining songs across the musical spectrum.

“I think of bluegrass as flexible music. It seems to lend itself to any musical style.” Henry explained how CMH Records was an integral partner in allowing them to arrange the songs “the way we feel them. They didn’t require us to do acoustic remakes, note for note like the original, which would be tempting.”

The arrangements for Iron Horse evolved easily because of the band’s bluegrass background. As Henry puts it, Sammy

Shelor of Lonesome River Band said it best: “Bluegrass music produces itself.”

Iron Horse’s discography reads like a mashup playlist of rock and bluegrass, from Metallica to Elton John. However, making seamless transitions can be challenging because choosing one is hard.

“The groups we have covered are phenomenal. Their material seems so good that crossing over to bluegrass is natural.” Henry said that at first, they were unsure. Still, after recording Metallica’s “Nothing Else Matters” and “Unforgiven,” they saw the concept more clearly, as if this is how they were supposed to be played. “Or at least another valid way to present them,” he clarified. “Maybe it is a credit to the greatness of the songs as well as the flexibility of bluegrass.”

However, Henry clarified that honoring the original while adding their creative stamp is a balancing act.

“Generally, bluegrass is a more up-tempo style, so you can double the time signature and sing the vocals close to the original tempo, and it will work. We also look for the signature licks of the song to see if we can incorporate them in a way that will lend it to bluegrass, as if you can hear Del McCoury singing it. That said, we try to stay with what we feel and what comes naturally, which usually ends up as something bluegrass.”

A turning point for Iron Horse happened in 2001 when CMH Records approached the band with an idea: bluegrass covers of rock songs with vocals. Before this, CMH had only done projects of instrumental rock covers. And Iron Horse was ready to do something different.

“We had recorded the Marshall Tucker Band’s ‘Fire on the Mountain’, so we were already trying something you wouldn’t normally hear in bluegrass. But even with that said, we were unsure that CMH’s idea could work.”

It did.

Henry admitted the driving force of Iron Horse is, “Presenting music worthy of the listener’s time. Producing something that has a listenability factor. That is hard, because everyone in the music business is trying to figure out that formula.”

The problem is that spending a lifetime working and worrying on one song to perfect it too often prevents future recordings. He said that kind of microfocus negatively impacts what you want to accomplish.

“If we like listening to it and want to listen again, that is a good indicator that we are getting close. We try to stay true to ourselves and the ideas in the minds of all four of us. Good

music is good music.”

Iron Horse never intends to abandon traditional bluegrass; it is their default music. Nevertheless, their cross-genre work introduces bluegrass to listeners who might not have otherwise discovered it. They know this because they receive comments like, “Finally, music that my father and I can listen to together,” or “We had never heard of bluegrass music until we listened to your version of Rocket Man, and now that we have discovered it, we love it.”

“Generally, most of the feedback on what we have done has been very positive. Fans of the original version like hearing it a different way, and bluegrass traditionalists like it because they hear some of the rock songs they grew up listening to performed in the bluegrass genre.”

Iron Horse strives to meet a certain standard before releasing any project. Still, anything pursued full force with heart and time has challenges. “Overall, we do it and hope for the

best. If it doesn’t happen, we turn the page and move on to the next gig or project.”

Henry pointed out that playing music with difficult people turns into drudgery, so the key is to surround yourself with people you care about. Thankfully, all the members of Iron Horse have been great to work with. We are still friends after all these years and enjoy playing music and hanging out together.”

He keeps his perspective at home, saying he’s just a normal person who can play music on a certain level. He enjoys constant family support because they are the band’s biggest fans. Plus, his wife’s family is musical. “They could all sing and play when they were in the mood. It was a great culture to have around.”

Considering all the musical giants in the world, Henry said he recognized how limited he

is and is “thankful for the opportunity to make a small contribution to the world’s musical landscape. All the while, I realize that it is my place to do what I can do for a short time.”

Looking back, Henry’s advice is to have fun, make memories, not try to live too fast and always enjoy where you are.

“Take lots of pictures and save an event flier of every place you play. Save multitrack files of every project you record. Interact with your fans. They have given you one of their most valuable things: their time and attention.”

As for what’s next, the door is open. So, come on in! The Iron Horse will take you on the ride of a lifetime.

by Brent Davis

In the four years between albums, a lot has happened for the idiosyncratic, boundary-pushing bluegrass/roots band Nefesh Mountain.

“It’s hard to pick up the phone and not just feel constantly affected by this world and this growing tension and divide in our country,” says guitarist/banjoist/singer/songwriter Eric Lindberg, who fronts the band with his wife, vocalist and songwriter Doni Zasloff. “There’s global things going on and there’s wars,” he laments.

But the state of the world has not driven them to despair or hopelessness. Instead, it inspired an honest, optimistic, multi-genre double album that showcases top-tier bluegrass musicians and Lindberg’s and Zasloff’s poignant songwriting.

“Beacons is the name of the album, and the songs are supposed to be 18 little candles,” Lindberg explains. “Little beacons of light that are reminders for my wife and I to stick to our own path and to see the bright side and to be grateful.”

Zasloff says Beacons came together quickly in early 2024, though it was a long time between albums.

“Eric looked at me right after New Year’s Eve and said we’re gonna do this album, and I said ‘Are you crazy? We have three kids. How are we gonna make this happen?’ And then I would say by April we were in the studio making this album, so Eric was on fire and inspired for those three months.”

While previous albums have featured Lindberg’s striking banjo playing, Beacons also allowed him to play the electric guitar, his primary instrument before bluegrass. The musical palette on Beacons is wider because one disc features bluegrass and the other features Americana music.

“We just decided that this album was bigger than the genre or anything specific and that we were gonna throw out the rulebook,” Lindberg says. “We decided that these songs would really live together on two separate things, paying homage to both the bluegrass that people know us for and that we love, and then also this new direction on the Americana disc that is sort of a blues jazz kind of jam direction.”

Zasloff says she grew up hearing all kinds of music and

toured extensively as a performer of children’s music. “I would say meeting Eric really opened the floodgates of bluegrass, and I fell in love with the genre, and fell as deeply in love with it as I did with him, and we started this journey together.”

Nefesh Mountain’s bluegrass music is rooted in the couple’s background and heritage as Jewish Americans. “Nefesh” means “soul” in Hebrew, as Zasloff explained at a recent concert. “We’re just trying to create a little Nefesh mountain universe where everyone is free to be themself and loved for exactly who they are,” she continued.

“On our first album, we recorded some songs that are actual prayers,” Lindberg says. “We want to do something good for the world. And it sounds a little corny, but when we walk around and when we travel, you can tell people are feeling lonely and a little heartbroken and divided. It’s a lonely time, and it’s my responsibility to not just write music that is self-serving, but to really try to give something back. And I really feel that’s something that being Jewish has always taught me. It’s not about us. It’s about giving back to our community.”

The bluegrass cuts on Beacons include A-list musicians Stuart Duncan, Rob McCoury, and Mark Schatz. Lindberg says that over several projects, Jerry Douglas and Sam Bush have become especially cherished collaborators.

“I love those guys with all of my heart,” he says. “I write some challenging stuff at times, and they’re always up for it. One of the huge gifts of my life is getting to know them. It’s amazing.”

For Nefesh Mountain’s ambitious, year-round touring Lindberg and Zasloff have assembled a collective of gifted musicians who rotate in and out of the band as schedules permit. They’ve recruited instrumentalists who can play all the kinds of music featured on Beacons. It’s the music that they want to play and that their fans want to hear.

“My dream for the band is that there’s sort of this kind of blues band rhythm section that on a dime can switch and we’re a bluegrass band,” Lindberg explains. “And then we really get to explore all of those things that I love, and I’m finding that a lot of folks out there really love, too.

“The 18 songs on Beacons are about remembering that this life is just yours and that there’s no rules,” Lindberg says. “Just follow your own flow of the river, and good things will happen. And for us, it’s been really super exciting to play in this kind of multi-genre format. We’re just gonna keep following the river and following our hearts because that’s what’s going to make us happy.”

by Jason Young

The satisfying sound of live music still has a home at Camp Springs Bluegrass Park thanks to North Carolina’s Coswell County resident Cody Johnson. With a heart full of fond memories and hard work, the park is again a thriving venue for bluegrass music.

“I grew up going to festivals, including Camp Springs, which we happen to live near,” shares Cody, who says a sense of nostalgia drove him to buy the once-famous stomping ground. “My mom and dad went up and down the East Coast to every festival they could go to. I just miss those good old days.”

A retired postal worker who never envisioned himself as a concert promoter, Cody recalls that Camp Springs was in terrible shape when he bought it. “It was really bad, I’m not gonna lie. It was overgrown, and the original stage was falling in on itself.”

He was able to salvage a few things. “We rebuilt the stage and were able to repair the original concession stand along with some other buildings that were left.”

Originally owned by legendary concert promoter Carlton Haney, the site hosted legendary performers including Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, The Osborn Brothers, Earl Scruggs, Jimmy Martin, and JD Crowe. It is where guitarist Tony Rice performed his first show in 1971 with JD Crowe & The New South and his last with the Bluegrass Alliance.

Camp Springs Bluegrass Park was also the subject of a 1971 documentary titled Bluegrass County Soul in which Cody’s dad appears.

“My dad helped Carton Haney with different things like security,” adding, “A lot of guys from the community helped out.

“In 2021, fifty years later, we got to bring the producer of the film back with his wife, along with four musicians who played in the movie. So that was pretty special!”

One of the highlights of Johnson’s festivals is airing the documentary. “I play it every year! I have a big drive-in movie screen. We play that for our campers the night before the festival.”

Cody, who noticed the abandoned property during his travels in Caswell County, had questions. “I did some research and found out who owned it, which was Carlton Haney’s family, and that is who I eventually bought it from.”

Celebrating his 8th festival since reopening the park in 2019, the proud venue owner says his annual Tony Rice Memorial Day Musicfest differs slightly from their other shows. “He wasn’t just bluegrass. He played a little bit of everything. So, we added a little bit of everything to the show. One year, we had the late 80s country band Exile play at the festival.”

Although crowds are not as big as in the 1970s, Cody says they grow each year. “We average around two thousand people for the whole festival.”

Cody says he’s still learning how to book acts for his festivals. “You can talk directly to a lot of musicians in bluegrass, but with some of the bigger acts, you have to go through a booking agent. I’m not used to that. Honestly, I’d rather go right to the source.”

Continuing, “Younger bands who’ve seen the movie Bluegrass Country Soul are excited to play at Camp Springs. I think that’s a really cool thing!”

Cody hopes that Billy Strings will play one of his festivals. “The year before the last, I got to meet Billy Strings at one of his shows. He announced our first Tony Rice festival from the stage. I would definitely love to have him—I would say he tops the list!”

While praising his wife, Donna, and Brother Chris for their support, Cody owes a great deal to the award-winning radio DJ Cindy Baucom. “She helps out with her knowledge of bluegrass. She has been our MC from the start.”

The festival organizer is excited about

upcoming plans. “We have a Camp Springs non-profit organization called The Camp Springs Music and Historical Foundation. Our goal is to build a museum that includes a hall for winter performances. It was always Carlton’s dream to build a museum, and I have so much memorabilia.”

Cody shares that Camp Springs has brought folks together over the years and has been a special place for the local community.

“It’s been a part of this area since 1969, so it means a lot to people. It’s a place where you can find your fix of bluegrass music!”

Years ago, while our kids were still emptying Trick-or-Treat bags and comparing their Halloween haul, my wife Susan looked at our family calendar and sighed: “After tonight I feel like we’ve been shot from a circus cannon and won’t land until after the New Year.”

We now realize we had a small-caliber schedule, at least compared to the events hitting the calendars of folks in the Bluegrass community.

That packed itinerary starts with fun but sleep-deprived nights at IBMA. Back home again, there’s the rush to do laundry and get on the road for the National Quartet Convention in Pigeon Forge and countless Fall Festivals across the country.

Next, pause to give thanks, eat more than we should, and head off to rounds of Bluegrass holiday performances. Celebrate Christmas and harmonize on “Auld Lang Syne.” Then put down that eggnog and get ready for SPBGMA, coming up January 22-25 at the Music City Sheraton.

It’s fitting, though, to first take a break and celebrate people who’ve worked behind the scenes so we could have a first-class event at IBMA’s first year in Chattanooga. IBMA staff, committees, sponsors, performers and volunteers joined with City of Chattanooga and venue employees to deliver a week of good fellowship, career development opportunities, amazing entertainment, and well-deserved awards.

As a writer, I especially enjoyed IBMA’s Songwriters Track sessions. Chair Mike Mitchell, founder of Virginia’s Floyd Music School as well as a writer and recording artist, knows how to put together practical programs. He credits committee members

Joe Dan Cornett, Helen Lude, Nancy Posey, Kevin Slick and Johnny Williams for their contributions and hard work.

During one-on-one Mentor Sessions, more than a dozen established writers, publishers and artists shared lessons learned with newer writers. Another program was modeled on “speed dating,” enabling writers to meet several publishers in a short time. Mentor Marty Falle gave me good advice from his perspective as a hit writer/artist, as did Mike Mitchell and Joe Dan Cornett in the earlier session.

A ”Know Your P.R.O.” panel provided stepby-step instructions on monetizing songs, from first drafts to chart hits (and from church hymnals to novelty “singing fish”).

Sherrill Blackman, SDB Music Group publisher, moderated that session. Panelists included Amanda Cook, artist and CEO of Mountain Fever Records; songwriter Dawn Kenney; and Joe Dan Cornett, then Director of Publishing for Billy Blue, now with North Chapel Music.

In a Song Analysis program, two writers each had a song evaluated by music industry pros. Offering advice were Hall of Fame Broadcaster Kyle Cantrell, founder of Banjo Radio; Jerry Salley, Billy Blue Records label head and singer/songwriter/producer; and Becky Buller, Dark Shadow recording artist and songwriter.

“Songwriting for JamGrass” explored unique aspects and challenges of crafting and arranging songs in this growing sub-genre that’s introducing more rock performers and their fans to roots music.

The Jamgrass session was led by Nancy Posey, Lipscomb University faculty member and writer. Other panelists included singer/ songwriter Jeff Daugherty; Grammywinning Americana artist/writer Jim Lauderdale; Ali Vance, 2025 Momentum Vocalist of the Year; Melody Walker, Grammy-winning writer and vocalist with Front Country band; and Jon Weisberger of Mountain Home Music, 2025 IBMA Songwriter of the Year.

Song Circles helped writers get to know each other and hear potential co-writers’ approaches to songwriting, while IBMA’s Songwriters Showcase gave selected writers a chance to perform their songs before a wider audience.

A highlight of this year’s IBMA was the tribute to Hall of Fame member Paul Williams (Humphrey). He was honored for a career that spans seven decades as a Bluegrass writer and performer, including being part of the groups Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, and the Victory Trio.

Mike Mitchell introduced Paul and an allstar group of hitmakers for songs and stories.

Playing Jimmy Martin’s guitar (courtesy of son Buddy Martin) was Doyle Lawson, Paul’s fellow Hall of Famer and friend and collaborator.

Harmonizing with them were Greg Blake, Turnberry Records’ 2025 IBMA Male Vocalist of the Year, and Johnny and Jeanette Williams, award-winning songwriters and recording artists currently in Shelton & Williams.

It was a special moment when this instant “supergroup” performed some of Paul’s best-known songs and invited the appreciative audience to sing along. There was even an encore performance later that day at an event hosted by Keith Barnacastle, Turnberry Records exec and publisher of The Bluegrass Standard.

At a packed reception, we learned Paul Williams has a new publisher. He will write with Tall Oaks Music, the new Turnberryaffiliated publishing firm led by Bluegrass icons Doyle Lawson and Donna Ulisse. With that collection of talent, you can expect more chart-topping songs are on the way.

by Candace Nelson

Bridget Lancaster has become a trusted voice in American home kitchens, but her story begins in the hills of West Virginia. Born and raised in Cross Lanes, just outside Charleston, Lancaster grew up in a culture where food was more than sustenance — it was memory, heritage, and community.

Today, as co-host of PBS’s America’s Test Kitchen and Cook’s Country, she translates that Appalachian food wisdom for a national audience, showing millions of viewers that good cooking doesn’t have to be complicated to be meaningful.

Appalachian food has long been overlooked or misrepresented, often dismissed as heavy, rustic, or outdated. But Lancaster embodies a different truth: it is a cuisine of resourcefulness, seasonality, and deep comfort.

She recalls growing up on meals like beans and cornbread, skillet-fried chicken, biscuits, and vegetables straight from the garden. Those dishes, rooted in thrift and tradition, inform the way she approaches cooking on television—not flashy, not trendy, but enduring.

When Lancaster talks about the joy of a pot of pinto beans simmering all day or the ease of pulling together biscuits with a few pantry

staples, she is channeling her West Virginia childhood. These are foods that stretch to feed a family, meals that emphasize flavor over fuss. Her manner on camera — warm, approachable, and never condescending — reflects how those foods were taught to her: not as culinary performances, but as skills every household needed to pass along.

After college, Lancaster cooked in restaurant kitchens in the South and Northeast, concentrating on pastry. She began working as the test cook for Cook’s Illustrated in 1998. She was also part of the launch team for Cook’s Country magazine and led the recipe development. She is now the lead instructor of America’s Test Kitchen Cooking School and has created hundreds of instructional videos.

Over the years, Bridget Lancaster has grown into her role as a cook and teacher. As Executive Editorial Director and lead instructor for America’s Test Kitchen’s online Cooking School, she focuses on helping viewers and students gain practical, usable skills in their kitchens. In interviews, she has said that her goal is for people to walk away from each episode with at least one valuable piece of cooking knowledge they can apply at home.

Her background comes through in subtle

ways. Lancaster brings a refreshing groundedness in a food culture often obsessed with kale salads or avantgarde plating. “I’ve been over kale for a very long time,” she told Boston Magazine with a laugh. “I am very pro collard greens.” The comment may have been cheeky, but it’s also revealing: collards, not kale, were the greens she knew growing up. In voicing that preference, she brought Appalachian taste to the table of American food media.

Bridget Lancaster’s cooking philosophy reflects a practical sensibility, with an emphasis on helping home cooks make the most of what’s available. That outlook resonates with Appalachian traditions of resourcefulness and preserving the harvest, where stretching ingredients and finding creative uses for pantry staples are second nature.

Even as she has become a national figure, Lancaster remains rooted in a grounded sensibility. On Cook’s Country, many dishes she presents—like buttermilk biscuits— reflect a humble, home-style cooking ethos that resonates with regional traditions. In her co-authored book Cooking at Home with Bridget & Julia, she and Julia offer 150 of their favorite recipes, emphasizing accessible, family-friendly, and comforting meals—qualities often associated with Appalachian home cooking.

For Lancaster, food is more than technique; it’s about helping people feel confident in the kitchen. She emphasizes making cooking approachable and practical, guiding home

cooks through recipes they can realistically prepare. This focus on accessibility reflects the grounded, home-style sensibility she developed growing up in Cross Lanes, West Virginia.

Bridget Lancaster brings a grounded, practical sensibility to her cooking, emphasizing recipes that are simple, accessible, and family-friendly. Her approach reflects the values often associated with Appalachian cooking—resourcefulness, clarity, and heartiness—while reaching a national audience through America’s Test Kitchen and Cook’s Country. In this way, the homestyle flavors and sensible techniques she champions carry the spirit of her West Virginia roots into kitchens across the country, leaving a quiet but lasting mark on American home cooking.