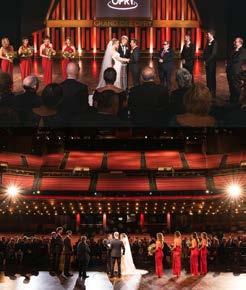

Keith Barnacastle • Publisher

Richelle Putnam holds a BS in Marketing Management and an MA in Creative Writing. She is a Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC) Teaching Artist, two-time MAC Literary Arts Fellow, and Mississippi Humanities Speaker. Her fiction, poetry, essays, and articles have been published in many print and online literary journals and magazines. Among her six published books are a 2014 Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards Silver Medalist and a 2017 Foreword Indies Book Awards Bronze Medal winner. Visit her website at www.richelleputnam.com.

Rebekah Speer has nearly twenty years in the music industry in Nashville, TN. She creates a unique “look” for every issue of The Bluegrass Standard, and enjoys learning about each artist. In addition to her creative work with The Bluegrass Standard, Rebekah also provides graphic design and technical support to a variety of clients. www.rebekahspeer.com

Susan traveled with a mixed ensemble at Trevecca Nazarene college as PR for the college. From there she moved on to working at Sony Music Nashville for 17 years in several compacities then transitioning on to the Nashville Songwritrers Association International (NSAI) where she was Sponsorship Director. The next step of her musical journey was to open her own business where she secured sponsorships for various events or companies in which the IBMA/World of Bluegrass was one of her clients.

Susan Marquez is a freelance writer based in Madison, Mississippi and a Mississippi Arts Commission Roster Artist. After a 20+ year career in advertising and marketing, she began a professional writing career in 2001. Since that time she has written over 2000 articles which have been published in magazines, newspapers, business journals, trade publications.

Singer/Songwriter/Blogger and SilverWolf recording artist, Mississippi Chris Sharp hails from remote Kemper County, near his hometown of Meridian. An original/founding cast member of the award-winning, long running radio show, The Sucarnochee Revue, as featured on Alabama and Mississippi Public Broadcasting, Chris performs with his daughter, Piper. Chris’s songs have been covered by The Del McCoury Band, The Henhouse Prowlers, and others. mississippichrissharp.blog

Brent Davis produced documentaries, interview shows, and many other projects during a 40 year career in public media. He’s also the author of the bluegrass novel Raising Kane. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Kara Martinez Bachman is a nonfiction author, book and magazine editor, and freelance writer. A former staff entertainment reporter, columnist and community news editor for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, her music and culture reporting has also appeared on a freelance basis in dozens of regional, national and international publications.

Candace Nelson is a marketing professional living in Charleston, West Virginia. She is the author of the book “The West Virginia Pepperoni Roll.” In her free time, Nelson travels and blogs about Appalachian food culture at CandaceLately.com. Find her on Twitter at @Candace07 or email CandaceRNelson@gmail.com.

A Philadelphia native and seasoned musician, has dedicated over forty years to music. Starting as a guitar prodigy at eight, he expanded his talents to audio engineering and mastering various instruments, including drums, piano, mandolin, banjo, dobro, and bass. Alongside his brother, he formed The Young Brothers band, and his career highlights include co-writing a song with Kid Rock for Rebel Soul.

Stephen Pitalo has written entertainment journalism for more than 35 years and is the world’s leading music video historian. He writes, edits and publishes Music Video Time Machine magazine, the only magazine that takes you behind the scenes of music videos during their heyday, known as the Golden Age of Music Video (1976-1994). He has interviewed talents ranging from Ray Davies to Joey Ramone to Billy Strings to Joan Jett to John Landis to Bill Plympton.

by Susan Marquez

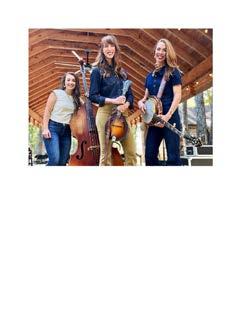

Cuttin’ Grass is a traditional bluegrass and Gospel band based in the Durham, North Carolina area. Co-founded in 2016 by Wally McKay and Amos Rozier (who coined the band’s name), the band aims to honor the roots of the music they play, as well as those who have pioneered the growth of the genre through the years. Steve Moore, who plays bass and is a vocalist for the band, served as their spokesperson.

“We are still pretty much the same group as when we started,” says Steve. “Four of the five original members are still in the band.” New to the band is Ricky Stroud, the mandolin player. “While all of us have played in other bands, Ricky is probably the most professional player we have. He grew up playing with his father in a group called The Pilgrims. They played Gospel music all over the East Coast. He also played with the Hager’s Mountain Boys.”

Steve says that all the guys in the band grew up playing music with their families. “We didn’t realize what a big deal jam sessions were until about 15 years ago. People came to our house at 7:00 every Saturday evening to play. It was a way of life for me while growing up, and I’m so thankful for that now.”

Cuttin’ Grass got its start at Lorraine’s Coffee House & Music in Garner, NC. “Lorraine Jordan, the owner, told Wally and Amos she needed a bluegrass band,” says Steve. “Wally called all of us together, and when we played together, it clicked. We have stayed together

all these years. We all get along, even though we come from hugely different backgrounds.”

The harmonies of the band blend well, which has been a big part of their success. They play for special social events, churches, and festivals. “We play good ol’ music in a hard-driving bluegrass style.” Everyone in the band sings. “We do a lot of covers in our shows – songs by Lonesome River Band, Balsam Range, and many of the old standards. We know a lot of the old songs, and we love it when the crowd sings along.” In a two-hour set list, the band will play about 35 songs. “We try to maximize how much music people get to hear.”

After nine years of playing together, the band released their first CD last year (Cuttin’Grass Volume 1). The album contains all original music, written by the band members. Steve’s wife, Sandra, wrote two of the tunes, “For the Love of Bluegrass” and “Let Jesus In.” Wally McKay wrote three songs on the album, all coming-of-age songs. Steve wrote a song called “Mountain Stream,” and Doug Mead wrote “Trail of Tears.”

Ricky Stroud wrote “He’s Done so Much for Me.”

Over the years, the band has played at several bluegrass festivals, including Willow Oaks, Bluegrass Island Festival, DeweyFest, and they have performed in the Heritage Village during the North Carolina State Fair. They have garnered accolades as well, from winning the

2017 Lil John Band Competition to placing third in the Got to Be North Carolina Bluegrass Band Competition in 2018, and second place in 2019.

Most gigs are on weekends, but they will play on Thursdays and Fridays when an opportunity arises. “Only one person in the band is still gainfully employed,” Steve says. “The rest of us are retired.” The band performs regularly at Lorraine’s Coffee House in Garner, where every Friday night is bluegrass night. Among other performers frequently seen at Lorraine’s are Lorraine Jordan and Carolina Road, Danny Paisley and Southern Grass, Joe Mullins and the Radio Ramblers, and the King James Boys.

“We have a lot of fun together, and we are always joking around on stage,” Steve laughs. “This is something we love – playing bluegrass music and making tens of dollars.”

In closing, he said, “We want to honor the roots of the music. We also work some more modern tunes into the mix. We want folks to enjoy an energetic, artistic, and heartfelt authenticity when they listen to us perform.”

by Jason Young

Words have power in the hands of a skilled artist; a fact demonstrated by Dirk Powell. The four-time Grammy Award-winning singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer has upheld traditional folk music while rethinking its conventions.

A master in both Mountain and Cajun fiddle styles, Powell has worked with Dewey Balfa, Levon Helm, Rhiannon Giddens, Loretta Lynn, Eric Clapton, and Joan Baez as well as with directors Anthony Minghella (“Cold Mountain”), Ang Lee (“Ride with the Devil”) and Spike Lee (“Bamboozled”).

Powell explains from his home in Louisiana that he has turned against traditional folk songs like “Knoxville Girl” and “Pretty Polly” songs he feels glorify violence against women.

“I was singing [Pretty Polly] one day during soundcheck at a show and I just heard the words come out of my mouth, ‘Sweet William stabbing her through the heart.’”

Powell remembers thinking about his daughters Amelia and Sophie and how the song always made them uncomfortable.

“I just got to a point where I thought, ‘I don’t want to spend this short time I have on this planet continuing those stories.’”

Inspired to write his song “I Ain’t Playing Pretty Polly,” Powell says he’s opting for a positive message.

“There are plenty of other stories to tell. I’d rather tell stories like I do in my song [I Ain’t Playing Pretty Polly] about my great uncle Clide and aunt Myrtle, who were married for seventy years. They were beautiful people, and [Clide] was a loving husband.”

Powell shares that there’s been a mixed reaction to his song.

“I had people come up to me in tears thanking me for it, especially women who are victims of violence.” Powell says not everybody has been happy. “I have had people fold their arms and reject it completely.”

Although the song is off limits, Powell admits a fond memory is attached to Pretty Polly.

“My grandfather, James Clarence Hay, played that song, and he played a very beautiful and unique version of it. It was really a treasure and a unique thing that came from him.”

The young Powell cherishes the time he had with his grandfather.

“I would always visit my grandfather in Kentucky. His banjo held mystique for me. It was just this really special thing where I would be around him, and he would play. It

was just really beautiful and timeless.

“He felt that I was learning the old-time music, and he loved it,” Powell recalls. “I started taking the Greyhound from where I lived in Ohio to Kentucky by myself, and just spent time with him and absorbed it all. I credit him with the source of music that really shaped my life.”

As a kid, Powell was drawn to different kinds of music.

“I listened to rock ‘n roll. I was probably around ten or eleven when John Lennon was killed. I thought, ‘What was this about The Beatles?’ So, I listened to them incessantly!

“A little later, I wanted to rebel, so you get drawn into things like Punk,” shares Powell, who discovered that there was more rebellion in old-time music than in his raucous youth music.

“Punk was very much about image,” explains Powell. “At some point I realized about my grandfather’s music, ‘Wait a minute, this is a much deeper rebellion because this is not tied to any commercial culture or image.”’

Finishing up a performance at the Alaska Folk Festival, Powell shares his wonderful time sharing the stage with his friend Rhiannon Giddens.

“It was really awesome. It was the [Alaska Folk Festival’s] 50th anniversary. Me, Rhiannon, and my daughter Amelia played, and it was just a blast.”

Describing the event, “It’s special in that they have fifteen-minute slots on the main stage, and anybody can sign up for them. This goes on for five or six days.”

Powell, who worked off and on throughout their careers producing and recording with Giddens, says she is an amazing talent, especially her vocal performance.

“It’s not like she is imitating something; she taps into that source in herself. She can sing without losing herself.

“Right now, I’m working with Rhiannon and we’re working on a record of hers,” Powell shares. “We’re also collaborating on a musical I’m really excited about. It’s been various things in the studio and then getting ready to go on the road,” adding that he and his daughter Amelia will join Rhiannon’s band.

“We’re gonna be full-time with Rhiannon later this month [April]with Justin Robbinson from the Carolina Chocolate Drops.”

As for plans, Powell believes in letting things happen naturally.

“For now, it’s not looking too much at the distant horizon. We got some cool records in the works and some cool tours coming up, and see how it flows after that!”

by Stephen Pitalo

You wouldn’t think the future of bluegrass music would run through a little town called Arden, North Carolina. But that’s where Mountain Home Music Company sits a label with its boots in the dirt of tradition and its eyes staring straight down the road toward tomorrow. For a genre built on stories older than paved highways, this is the kind of balancing act that either makes you a pioneer or leaves you a relic. Mountain Home knows which one it wants to be.

Founded in 1993 by Mickey Gamble and Tim Surrett as a humble offshoot of Crossroads Label Group, Mountain Home started as a home for bluegrass gospel. But like most things that start small, it grew restless. The label widened its scope, built a catalog of some of the finest bluegrass pickers and singers around, and quietly became the kind of place where a young artist could find a future without losing their past.

Jon Weisberger has been driving that vision since 2019. The former bass player, songwriter, and bluegrass lifer took on the A&R role at Mountain Home with the quiet understanding that this music lives or dies by its ability to move forward without forgetting who brought it here. “I went to work for the label part-time at the beginning of 2019, and then full-time in August of that year,” Weisberger said. He didn’t say it like a man taking a job. He said it like a man joining a cause.

The label’s latest bet on the future is a bold one Dolby Atmos, an immersive audio format designed not for front porches, but for movie theaters and home systems with smart soundbars and overhead speakers. In other words, the exact opposite of the cabinin-the-holler stereotype bluegrass has carried for decades.

“We were basically the first through the entrance, and we’re still the major player in

bluegrass, to be releasing stuff in Dolby Atmos immersive audio,” Weisberger said. “And what’s unique about the Atmos system is that it’s a smart system that tailors what gets sent to whatever Atmoscompatible devices it finds at the other end.”

It might sound like heresy in a genre where the warmth of a Martin guitar or the scrape of fiddle strings are as sacred as church pews. But Weisberger knows better. For bluegrass a music born around a single microphone in the 1940s and built on tight harmonies and close playing this technology doesn’t erase the soul of the music. It expands it.

“It’s actually really good for acoustic music because it means that immersive audio mixing… means that you can do less processing of the instrument sound, so you get a more natural, closer to the real thing kind of sound,” Weisberger explained.

jazz influences but rooted in the hills.

“To me, it’s important that our roster as a whole represents the diversity of bluegrass and that balance between tradition and innovation,” Weisberger said. “We kind of balance on the macro level, so to speak, with the variety that we have in our artists.”

That variety isn’t just for show. It’s a business strategy, a survival plan in a music industry where streaming has changed the rules of engagement. Selling CDs off the stage might still pay for gas money, but the real future is online. Mountain Home knows this because they’ve seen the numbers.

In a way, technology is finally catching up to what Bill Monroe figured out 80 years ago, according to Weisberger: get the sound right in the room, get the players standing close enough, and let the music tell the story. Mountain Home has made storytelling its business, and their lifetime roster reads like a bluegrass festival lineup stretching across generations. There’s Balsam Range and The Grascals. Sister Sadie is straddling the line between bluegrass and country. The young banjo innovator Trey Wellington is steeped in

“The record business these days is the streaming business, and that’s where the listeners are. That’s where the money is,” Weisberger said. “We love and appreciate radio… but most artists will tell you that CD sales are way, way down. And physical products only account for about 10% of the recorded music revenue.”

So, Mountain Home does what smart bluegrass musicians always do adapt without compromise. They help artists build streaming audiences with one song, one click, one honest performance at a time. It’s not flashy. It’s just work. And that same philosophy extends to how the label signs new artists. They’re looking for lifers, not hobbyists. Weisberger said it plainly: “One of the things that we look for a lot is people who are lifers, people who are

really dedicated and committed to making a career in music an integral part of their life.”

In 2024, Mountain Home added Vicki Vaughn, Jesse Smathers, and veteran Gina Britt to its growing family—a lineup that looks a lot like the genre itself: young faces with old souls and old hands with something new to say.

The label’s reputation for community runs deep. Mountain Home projects like Bluegrass at the Crossroads and Bluegrass Sings Paxton are built on collaboration a who’s-who of bluegrass voices stepping into the studio together to see what happens. It’s the kind of thing that occurs naturally in bluegrass circles, where everybody knows everybody else from the road or the picking tent backstage.

“I like to hear people play together. I think it’s really fun to put different combinations and groups of people together and hear what they do,” Weisberger said. “To me,

that just unleashes a lot of creative energy.”

That creative energy is the fuel driving Mountain Home toward its next chapter. Weisberger doesn’t claim to know exactly what the label will look like in ten years. But he knows the direction.

“Musically, it’s the artists that we have and the artists that we will be bringing on who will set the pace, the direction musically,” he said. “We exist to help our artists get their musical vision realized and out where people can hear it.”

At the end of the day, Mountain Home Music Company is doing what bluegrass has always done best. They’re telling stories. They’re playing real music on real instruments. And now, thanks to Dolby Atmos and a vision for what’s next, they’re doing it in a way that might just shake the floorboards of some living room halfway across the world.

So, by trying to deliver the truest sound with the best technology, Mountain Home is carrying the truths of today into everyone’s tomorrow.

It’s often difficult to separate reality from fantasy or fact from fiction today. As we increasingly head in the A.I. direction, tech advancements allow for computer-generated “creative” work that can sometimes actually…trick us. From artificial intelligence artwork and books to “deepfake” videos, the tools used to create artificial art and entertainment have suddenly become quite sophisticated.

Unfortunately, that has also affected the music business. A.I. music has invaded the creative space, and real artists now compete with soul-less content crafted from data instead of from the heart.

To help solve this problem, a new enterprise—still in its first year of operation—called Humanable aims to separate real music from “fake” music and identify real music made with the human touch.

The company stamps its approval on music crafted by human hands. Humanable evaluates a track for a small fee and deems it “100% human-made.” This assures both listeners and recording industry folks that they’re experiencing the real deal.

“As a group, the overriding motive for creating this company was to protect songwriters and artists from generative A.I. siphoning off their royalties and imitating human creativity,” explained Humanable CEO Tim Wipperman. “Technology can help ferret out generative A.I. after the A.I. generated song or track is in the marketplace, but technology is a never-ending cycle of whack-a-mole. The bad guys do X, and the good guys catch them. Then the bad guys figure a way around the technology.”

Wipperman said Humanable helps stop that cycle by approaching the problem “from the point of creation.”

“Bots and generative A.I. don’t have social security numbers and driver’s licenses. Humans do,” he explained. “We ask the writer or artist to register with us as a human, receive a unique personal identifier, then for each song or master, upload it with some info, and that song/master receives another unique identifier that the artist verifies is humanly created. We have audit processes as checks to be sure everyone is truthful.”

He said, “They then are able to use our Humanable trademark,” describing it as “sort of a musical ‘certified organic’ image.” The artist may use it “in all their dealings with publishers, record companies, distributors, and DSPs.”

Wipperman said this certification “guarantees to all those downstream folks that a human created the music. It eliminates legal issues with copyrights and ownership and generates full royalty streams.”

So far, the company is off to a good start, considering it just launched in the fall of 2024.

“We have, at this point, over 4 million songs registered with Humanable,” Wipperman said.

Many artists in bluegrass pride themselves on the heartfelt originality of their songwriting. While other genres, such as pop, are already quite infused with computerdriven music and production techniques, most roots music tends to be more stripped down and genuine. That makes the idea of A.I.-created music even more of an affront to artists who consider authenticity a central feature of what they do. It seems based on his background, Wipperman might truly “get it” about how devastating A.I.-generated tracks might be to roots genres.

“My background was as a music publisher,” he said, explaining that he ran Warner Chappell for 29 years. He’s also an artist himself. “I played on Earl Scruggs 25th Anniversary album.”

Each team member at Humanable brings a different strength.

“One of our founders is an intellectual property lawyer. Another has been in the arts since she was little,” he said. “We all have a love for writers and artists and the right to make a decent livelihood from music. Our long-term goal is to have all human writers/artists join us and give the business entities an incentive to use music created by humans,” he summarized. “A Humanable song or track assures them they are publishing, releasing, and streaming a musical work that is clean.”

by Susan Marquez

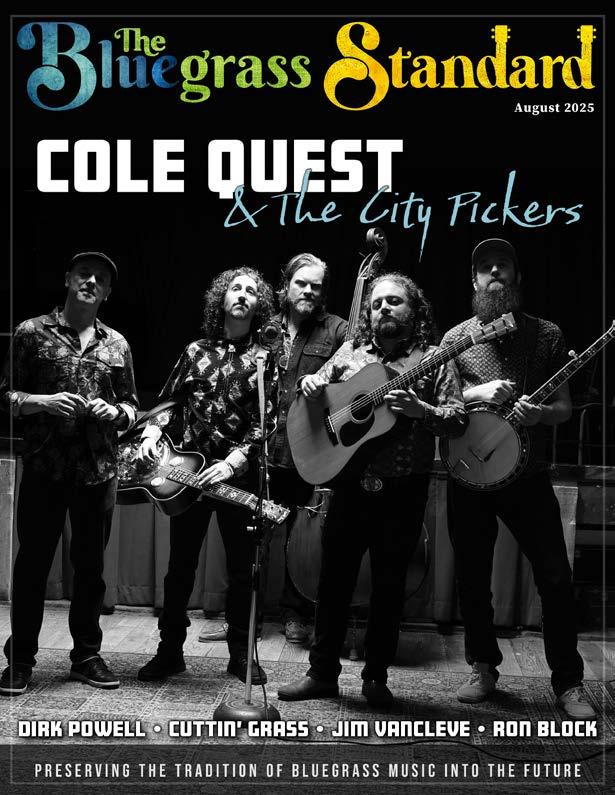

If music is like a woven piece of art with various elements blending to become one, such is the union of Bronwyn Keith-Hynes and Jason Carter. The two fiddle players are now married; their music and lives intertwined into a beautiful tapestry that was always meant to be.

Bronwyn hails from Charlottesville, Virginia. She is a two-time IBMA Fiddle Player of the Year and a Grammy award winner for her work with Molly Tuttle and Golden Highway. Now she is playing on her own. Jason’s roots are in Kentucky, where a stretch of the Country Music Highway in Lloyd is named after him. For thirty years, Jason has played fiddle for the Del McCoury Band, winning three Grammys, including one in 2018 for Best Bluegrass Album with The Travelin’ McCourys, of which he is a founding member. Jason has taken home five IBMA Fiddle Player of the Year awards. He also has his own Jason Carter Band.

It appears the two were destined to meet. Both are phenomenal fiddlers, both are focused on their musical careers. “We met each other at different bluegrass festivals,” says Bronwyn. “We started looking forward

to seeing each other, and our relationship grew from there.”

With music at their core, Jason and Bronwyn seem to be in perfect harmony. In music, harmony is like fitting puzzle pieces together, and it is apparent when talking with the couple that they are a perfect fit for one another, often finishing each other’s sentences, but never stepping on one another’s toes. If melody tells a story, unfolding like a captivating tale taking the listener on a musical journey, their story unfolded in a natural, organic way, beginning with backstage glances and romance. The heartbeat of a song is rhythm, communicating emotions and thoughts like a language without words. There is no doubt this power couple has a rhythm of their own, sharing the language of love in their special relationship.

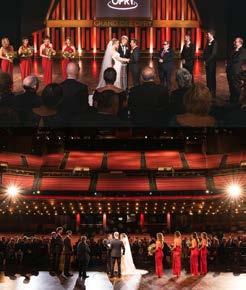

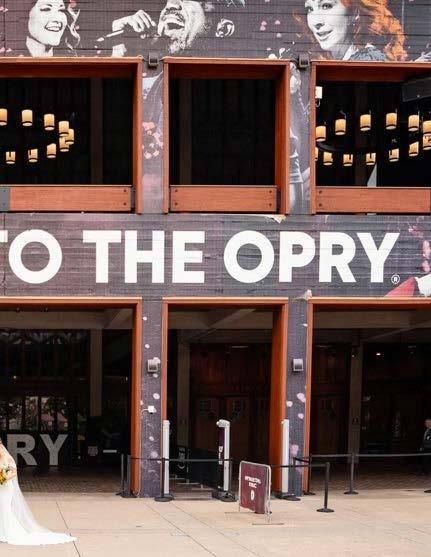

Jason and Bronwyn began dating in 2018 when Bronwyn moved to Nashville. When they got engaged, both began thinking about wedding venues. “We started brainstorming about places in Nashville that were special to us,” says Bronwyn. They had each played the Grand Ole Opry several times through the years, and Jason

started thinking that it would be cool to get married there. While Bronwyn thought it was a bit of a stretch, Jason decided it couldn’t hurt to ask. “I knew Charlie Worsham had his reception there and I was hoping we could get pictures on stage,” he says. “I talked to Dan Rogers, manager of the Opry, and to my surprise, he said if we could do it as a sunrise wedding, we could hold the ceremony on the stage.”

Inviting 200 people, many of them musicians, to come to a wedding held on a Tuesday morning at 8am was a bit of a gamble, but Jason says their family and friends all showed up at the October 15, 2024, ceremony to witness the couple repeat their vows. “The Opry was so gracious. We were married on the circle, which was such an honor for both of us.” Vaughn Johnson officiated the ceremony. Bronwyn’s bridesmaids were a bluegrass who’s who of entertainers: Molly Tuttle, Brenna MacMillan, Christina Vane and

Shelby Means, who served as Maid of Honor. Jason’s groomsmen were Aidan Keith-Hynes (Bronwyn’s brother), Jeff Carter (Jason’s brother), Alan Bartram, with Michael Cleveland, who served as Best Man.

The brunch reception was held in the Grand Ole Opry’s Studio A, where the popular television show Hee-Haw was filmed. An all-star band of musician friends played at the reception. The icing on the cake was when the couple returned to the Opry that evening to perform. “I think the audience was surprised when I walked out in my wedding gown,” laughs Bronwyn. The couple performed “Trip Around the Sun,” off Bronwyn’s first vocal album, I Built a World. It was her first time to sing on the Opry stage. Jason sang as well, and the couple performed “Train 45.”

Jason says the Opry crew was very gracious. “They took care of us and made us feel welcomed and at home. There really

is a family atmosphere at the Grand Ole Opry, and it was a big honor for us to begin our marriage there. It was a true fairytale day.”

As the couple settles into married life, they are feathering their nest in Hendersonville, Tennessee. Both Jason and Bronwyn are busy with their careers. Bronwyn is in the studio working on a new solo record, and she will start a tour in August. Jason recently released an album, Twin Fiddles, with Michael Cleveland, and he is busy with the Jason Carter Band. Between writing, recording, and touring, they are rarely at home. While images of the couple playing fiddles together at home come to mind, Jason says the reality of their life is sometimes a bit different. “I spent all yesterday working in the yard. But I don’t mind -- I’m living the dream.”

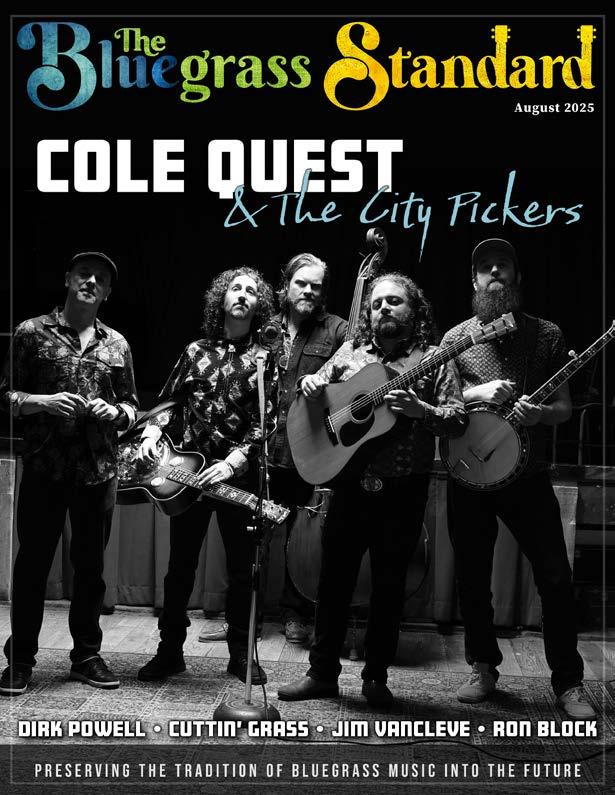

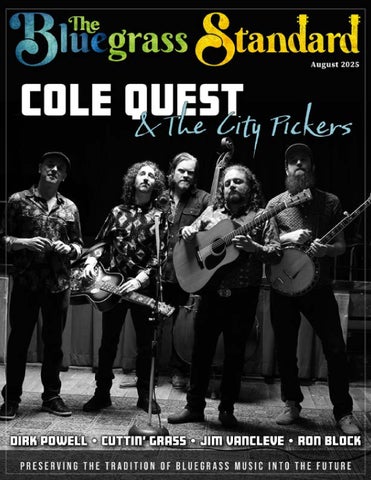

Folk singer Woody Guthrie made his mark on music at a time when many art forms had a huge influence on world events. It was a time of tumult, and a time when new paradigms were introduced through song. According to Cole Quest, of the bluegrass group, Cole Quest and the City Pickers, music can still serve the same role today.

As Woody Guthrie’s grandson, Quest has been influenced quite a bit by the mark his grandfather left on the folk music scene. He said familial connection is, of course, important, but it’s more about a philosophy; Quest thinks music’s proper role is as an agent of change.

“I have a personal belief that there is a responsibility of all artists to call out the injustices of the world,” Quest explained. He hopes to do that, just as his grandfather did.

Part of that mission is on display with the group’s new album, “Homegrown.” Their first release in four years, the record dropped in July. The track list of “Homegrown” includes covers of three of his grandfather’s songs, one of which is the well-known Guthrie number, “Pastures of Plenty.” The album also features a song co-written by Woody and Arlo Guthrie, and songs penned by Peter Rowan and John Hartford. The band released an EP of all original material four years ago, but Quest said “Homegrown” is the first fulllength LP.

Quest thinks the band hailing from Brooklyn, New York, gives it a slightly different sound than much of what’s available in bluegrass. To him, there’s a difference between being a “city picker” and a “country picker.”

“I’m an Italian Jew, born just outside Washington Square,” he explained. “I didn’t grow up as a bluegrass musician in the heart of Kentucky, listening to Bill Monroe every day. I think there’s an innate difference in the sounds.”

He explained that the traditional sound wasn’t “baked into his brain” the way it often is for those reared in Appalachia. He said he encountered bluegrass in a big city environment that attracts alternative types of musicians. For example, he said, “Jazz musicians come here from Japan and find a bluegrass jam…”

As he describes it, the bluegrass coming from the Big Apple is a diverse melting pot, much like the city itself.

One example comes from within the group; the harmonica player is from Brazil. Backgrounds in blues, jazz, rock, classical, and other influences help the group meld diverse inputs in a way that puts their unique stamp on bluegrass.

“I grew up playing guitar,” Quest said of his love affair with music. He’d mostly played in rock bands. Then, he was exposed to something new, and a spark was lit.

“I found bluegrass music 15 years ago in a pub in Astoria, Queens.” He learned to play the mandolin. He picked up a dobro. The rest is history. He said the band is not only influenced by the folk sounds of Guthrie, but the expected bluegrass greats also ignite a

spark of creativity and set a standard to be emulated.

“We’re big fans of Flatt and Scruggs, and Bill Monroe,” Quest said, explaining why a Brooklyn native could be so drawn to a genre that seems a world away from the concrete streets of his upbringing.

“I really appreciate the lyrical straightforwardness…bluegrass is honest and direct,” he summarized.

by Kara Martinez Bachman

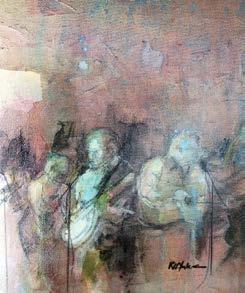

For most visual artists, subject matter comes from the stuff that touches the soul. It comes from themes that tug at the psyche, either because they are familiar or because they offer intrigue. Sometimes, those themes hit close to home.

Artist Robert Yonke’s gentle work depicting bluegrass performers resulted from a longtime fascination with the music, which began when he was a child.

“My father worked for a trucking company out of Wheeling, West Virginia,” Yonke explained. He said his parents’ “big entertainment” was attending the Wheeling Jamboree.

“There was a lot of bluegrass,” Yonke explained.

While this music was always around, he said it wasn’t until later that it truly gripped him. He began attending many bluegrass shows in his hometown of Pittsburgh, Penn. For ten years, he played at a weekly bluegrass jam at a VFW hall in the area he’d moved to next, western Maryland. At some point, he said, “the artwork was a natural thing to do.”

“I started painting those things [portraits of musicians] with no objective in mind,” Yonke said. Then, his daughter – who now handles most of his artwork business –started putting his work online. Somehow, somebody at the IBMA saw it.

“We took a ride down to Nashville for the 2007 conference there,” Yonke recalled, “and I did the artwork for 2008. We did that for three or four years. We’d always set up a booth and display artwork.”

As if being the artist for the annual World of Bluegrass conference weren’t enough, he also created promotional materials for

events such as DelFest.

“For the first year of DelFest, I did a watercolor of Del [McCoury] himself,” Yonke explained. That painting would eventually be donated to a hospital.

He’s painted his fair share of musicians from Bill Monroe to Missy Raines to the Stringdusters. However, Yonke isn’t solely about bluegrass; he also creates artworks depicting golfers, evocative landscapes, riverboats, and more.

While Yonke’s primary passion is watercolors, he said his work has evolved.

“A lot of my stuff has gone to mixed media, with watercolor and then acrylic and all kinda stuff on top of it,” he said.

Original artwork, prints and cards are available at his website, Appalachianstudio. com. While Yonke does not do strict commissions, in the past, he has made arrangements to create artwork around a specific subject matter. To discuss

possibilities, he suggested reaching out via the website to his daughter, Becky Sciullo.

Today, Yonke lives in Florida but still occasionally performs with a group of musicians from a previous band he had in West Virginia.

“We do mostly old country, with a few numbers of the old bluegrass stuff. We do a lot of stuff in hospitals and nursing homes,” he said. “One of the things I miss about being down here is I do miss music. I get together with people, but it’s not the same.”

His first and primary musical passion was the mandolin, but after a shoulder injury, playing it eventually became more difficult. He switched to something that seemed easier on his shoulder. He told himself: The Lord’s telling me to pick up the guitar.

Yonke said he’s liked bluegrass for as long as he can remember. One of the things he has enjoyed – whether he’s jamming with other musicians or creating paintings of them –is the welcoming nature of the roots music community. He said bluegrass is filled with “small egos.”

“The bluegrass people are just so easy to fit in with,” he said. “You can show up at a bluegrass festival, walk around, and then jump in.”

He noted how much he liked the years he attended IBMA: “The whole fun of it was at night, hanging out at the hotel. The bands would even be on the elevators playing!”

He said the great thing about bluegrass jams is you don’t have to be great to be welcomed in with open arms.

“As long as you can keep time,” he added, with a laugh. “You DO have to be able to keep time.”

Alison Krauss and Union Station are back with a new album. After a fourteen-year hiatus, the multi-platinum and gold-selling super group is breaking the silence with Arcadia.

Their first release since 2011’s Paper Moon, the album features new member singer/ guitarist Russel Moore. Banjoist Ron Block was thrilled to take the stage with Union Station at the Grand Ole Opry’s OneHundredth Anniversary.

“It went really well,” says Block, whose thirty-three years in Union Station helped create the hits, “A Living Prayer” and “There is a Reason,”

“We rehearsed, but we haven’t played with this new bunch,” shares the six-time IBMA winner about their first performance with new members. “It’s Jerry Douglas, Alison, Barry Bales and myself. Dan Tyminski quit [the band] a while back, so Russell Moore stepped in, and we added Stewart Duncan to the mix as a multi-instrumentalist.”

Block is thrilled to have Moore. “I remember seeing him onstage in the late eighties. His singing was just so powerful! So, I was blown away by Russell years ago, and when his name came up as a replacement for Dan, I thought that would be great!

About reuniting with Alison Krauss & Union Station, Block said, “Oh my gosh, it’s like coming home. We all go out and have our musical adventures and do fun things, but for me, and I think for everyone else, it’s a musical homebase.”

Block attributes the absence of Alison Krauss & Union Station to solo work.

“Alison came out with Windy City in 2017, and Barry and I played in that band. It was a more old-style country band. After that, she did another record and toured with Robert Plant.”

The Grammy Award-winning musician says plans for a new Alison Krauss & Union Station record were being discussed.

“I remember talking to her [Alison] about it, and she found the first song, which was the Jeremy Lister song ‘Looks Like the End of The Road,’ and that kind of set the tone for a whole new record,” said Block. “She’ll do that.” He described Alison’s ability to find music as, “She’ll get a song or two, and all of a sudden, she is getting this idea of what she wants the new record to be.”

Block says Arcadia is more about story songs than past albums. “There are some similarities, but it definitely sounds different.” The Union Station banjoist says he dialed back his performance. “I know my playing on the banjo is much more stripped down than it used to be. The album is more lyric-focused,” shares Block. “I think we were all conscious of the songs.”

The California native reveals that he’s putting other projects on hold. “I have a record I started several years ago. I was going to finish it, but lots of other stuff came up in the last three or four months.” Calling them “creative enterprises,” Block enjoys working with the band Southern Legacy and North Ireland tenor banjoist Damien O’Kane.

“I am finishing up an album with Damien O’Kane. I just have a few things to do about it, and Southern Legacy is going to

have someone fill in for me. I’m trying to juggle all these things, but Alison has always taken precedence over everything else!”

Block describes how he felt working with Alison and his Union Station bandmates for the first time in fourteen years. “We had a great time! And, of course, you’re trying to get the best performance possible.”

He said, “It’s been years of traveling, hanging out, and playing music together. You know how it is when you have friends from when you were a teenager or in your early twenties—you see them, and nothing has changed. It’s great! I love all those guys and respect them so much.”

The “Living Prayer” songwriter says the recipe for their success is keeping their egos in check. “The whole philosophy of the band is you set aside doing what you think is best for being part of a unit. If you listen to our music over the years, what we play on those records is in support of the song and putting the lyrics across.”

Block would like to see them work on a regular basis, saying “I would love to continue.”

He expresses gratitude, “AKUS [Alison Krauss & Union Station] brought me so much in my life; the creativity, the level of musicality, the level of touring, and making a good living—it’s been incredible. It’s being in a band where people actually care about each other.”

by Brent Davis

One of the albums that knocked the socks off Jim VanCleve might surprise you.

This extraordinary fiddler with such groups as Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver, Mountain Heart, and now, Appalachian Road Show, acknowledges the influence of many bluegrass bands and musicians, including Tony Rice, Norman Blake, Doc Watson, and the David Grisman Quintet. But So Long, So Wrong by Alison Krauss and Union Station is the album that would change things.

“When I was in high school, Aerosmith or somebody would release something that just sonically blew my mind,” VanCleve recalls. “And I would just be wondering why the music that I love to play and listen to so much couldn’t also sound that captivating sonically? Why can’t my favorite bluegrass band sound like Aerosmith on tape?”

The music VanCleve loved was bluegrass. His family regularly went to a Golden Corral Steakhouse in Englewood, Florida, just to hear Ralph Blizzard, a world-renowned fiddler. Even as a kid, VanCleve would stand on a chair and blow a train whistle, accompanying his hero at the restaurant. After the family relocated to North Carolina, VanCleve became a serious fiddler, participating in jams, festivals, and contests to master his instrument. He was in high school when Krauss released So Long, So Wrong.

“She used (engineer) Gary Paczosa and recorded it in a real studio with

one of the best bands assembled to that date for that style of music.” VanCleve felt the album achieved the sound in bluegrass he’d been searching for. “She had obviously asked the same questions that I had. And you can point at almost everything she’s done and say those records are sonically some of the best things that have been put to tape. And they gave a high watermark for us all to chase for a while.”

Because of VanCleve’s attention to sound he’s not only a respected and admired fiddler and performer-he’s an in-demand producer of country, bluegrass, and Americana albums with more than 20 years of experience. He can create the sound that allows the artists to shine.

“The producer is like the director of a movie,” VanCleve explains. “You’re not just guiding performances. You’re making sure you have the right songs with the right singers. There’s a lot of different hats you can wear. And there’s a lot of head games, too. A lot of times, you’ll have artists who are so talented, but they can’t get out of their own way. Because I’ve also been an artist, I’m able to climb into their space so that they can give the performance that they’re capable of. It’s like a pitcher getting the yips. Part of the job as a producer is to inspire and coach them out of that.”

As the fiddler for the Appalachian Road Show band, VanCleve maintains a busy touring schedule in a group that showcases the spirit, culture, and music of the region,

where all the members have deep ties. In 2021, the group was named both New Artist of the Year and Instrumental Group of the Year by the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA).

“And it’s such a good vehicle, such a great, organic, real, honest vehicle for bringing out what’s special about a lot of the music that we all love,” VanCleve says. “And I’ve never been a part of anything that’s grown any faster than this band has, and that’s been as exciting as it can be. It’s a cool thing to be in the business for 25 years and be able to say that. It’s fun.”

In his long and distinguished career as a producer, VanCleve says his solo project, No Apologies, was a milestone. Producing records for Carrie Hassler and Mountain Heart are highlights. He was especially honored to be asked to write a theme song for the IBMA awards show. But now, as a producer, trying to create the captivating, sonic landscapes he sought as a young man, his most satisfying moments may not even be noticed.

“It’s the little things now that make me proud now. Nobody will ever know it mattered to me, but if it’s something I was chasing and we are able to get there, then that’s cool.

“It always starts with a great player, a great instrument, and a great performance. And to me, the magic happens in the air between the musicians playing the thing live and reacting off of one another. And I do feel like I’m getting some sounds that I would have been so excited to achieve when I first heard So Long, So Wrong at the age of 17 or 18. So I feel like I’m arriving at something.”

by Stephen Pitalo

Building Community, One Song at a Time

There is a quiet intention behind everything The Storytellers do. Whether they’re deep in the groove during an onstage jam, sharing lunch before rehearsal, or evaluating the next bit of content for their growing online community, this progressive bluegrass band from Southern California approaches music—and life—with a deep respect for that direct connection to their audience. Founded in 2017, The Storytellers evolved from a duo playing local Los Angeles venues into a five-piece band making mouths drop on national stages, headlining festivals, and writing music that reflects that love of creativity, presence, and humanity. They don’t chase trends or fit into genre boxes. Instead, it’s been about listening carefully—to the music, each other, and most of all, their audience.

Bassist and founding member Lance Frantzich knows that audiences expect labels. In today’s world, where streaming services and festival lineups demand categorization, a band that blends folk, rock, bluegrass, jazz, and improvisation can leave people grasping for a definition. Frantzich accepts that reality but doesn’t let it limit them. “We wish we didn’t have to categorize our music, but I understand why we do because we live in a category culture,” he says. “If the word ‘grass’ is in there, we’re pleased.” The Storytellers have embraced “progressive bluegrass” as a label but have come to love another term even more—“gateway grass”—because of what it says about their mission. “We see ourselves as a gateway to traditional bluegrass,” Frantzich explains. “We’ve been performing at a lot of bluegrass festivals, so we’re extremely pleased that at least some part of the bluegrass intelligentsia recognizes our music as being in the realm of bluegrass. We’re still working to convince the ones who don’t. It may take some time.”

Part of what makes The Storytellers so difficult to pin down is the diverse musical backgrounds of its members. Guitarist Scott Diehl and Frantzich started out playing folk music, while percussionist Steve Stelmach came from a rock and roll background. Fiddler Tyler Emerson has roots in jazz and gypsy jazz, while banjo player David Burns brings years of bluegrass and Irish music experience. Mandolinist Ethan Van Thillo, who Frantzich describes as a freespirited Santa Cruz hippie in his early days, adds colorful, free-form playing to the mix. These different influences don’t just co-exist; they have reshaped how each member approaches their instrument. “Tyler has made Dave more jazzy, so we’re creating ‘Jazzgrass’!” Frantzich says. “The Deadhead contingent of the band – me and Scott – has influenced everyone to become much freer and more experimental.”

But for all their musical freedom, The Storytellers are deeply committed to their audience and view every performance as a collaborative experience. Their shows aren’t rigid recitals of rehearsed material; they are living, breathing moments shaped in real time by the crowd’s energy. “Our audience is inextricably connected, on and off stage, to everything we do,” Frantzich explains. “We’re audience conscious. We’ve conditioned ourselves since the beginning to be aware of them, to bring them into the experience, to make sure they recognize that they’re affecting what’s happening during a show.” This can mean completely abandoning a carefully planned setlist if the audience vibe calls for something different. At a show scheduled with a grassy, folky set at Calico Ghost Town, Frantzich remembers noticing a sea of tie-dye shirts just before showtime. “They’re there to dance, and they won’t be satiated with three-minute songs, so it becomes about longer, stranger jams. You know, bring out The Dead! So, we’ll

abandon an entire setlist if we must. We’re here to please the audience. That’s our only agenda.”

The band’s forthcoming album, *Blossoming Saguaros*, marks an important step in The Storytellers’ evolution. For the first time, they fully embrace original songwriting, a process Frantzich describes as transformative both musically and personally. The challenge to write their own material came from their publisher, Lynne Robin Green, and the band rose to meet it together, crafting songs that reflect their collective spirit. “Deciding to write our own material has been the single most important decision we’ve ever made,” Frantzich says. “It’s truly a band effort. Everyone is contributing at high levels. There are no songwriters or ‘he did the lyrics’ and ‘he wrote the music.’ It’s evolving organically like the band did.”

The themes running through *Blossoming Saguaros* reflect the same values guiding the band since its beginning—love, presence, spiritual growth, and the search for meaning in the everyday. This shared commitment has revealed something profound within the group. “We’re all on the same page as far as being on a path towards personal growth and greater understanding of what it means to be human, which are the themes that folk and bluegrass explore,” Frantzich explains. Working so closely together on original material has deepened their respect for each other’s talents and insights. “We appreciate more than ever how a single chord change can significantly affect the musical story,” he says. “We’re trying to create fine art, so the devil is in the details.”

That attention to detail extends beyond music. The Storytellers operate with a code of conduct rooted in mutual respect, kindness, and mindfulness. This is not

a band where egos run unchecked or members drift apart between shows. “We hug each other when we see each other. We hug when we leave. We share meals. We consciously make sure to say kind things to each other,” Frantzich says. The band avoids alcohol or drugs during work and checks in with each other about their families and lives outside the band. “Everyone understands now that the nature of anything fine is that it’s fragile. It can break easily. It must be handled with care.”

That fragile beauty is something Frantzich thinks about often. It’s why their social media presence is not just promotional but deeply interactive. The Storytellers have built an online community that feels like an extension of their live shows—a place where creativity is encouraged and everyone has a voice. “We encourage participation and sharing of insights and humor,” Frantzich says. “We have endeavored not to make the community about us. We’re not leaders. Our community are not followers. We’re all in this together, co-creating the community.” This approach has resonated. The band has averaged nearly 1,000 new Facebook followers per month over the past year, a testament to their cultivated inclusive space.

Ultimately, The Storytellers are about more than just music. They are about fostering creativity, connection, and community in a world that often prioritizes consumption over creation. For Frantzich, picking up the bass was never just about playing notes—it was about reclaiming time and energy to make something meaningful. “I don’t want to spend my life watching other people live their lives,” he says. “Life is precious. Don’t be passive. Be active. Do. Act!”

As The Storytellers move forward, their path is clear. They will keep writing,

performing, and building spaces—on stage, online, and in their songs—where people can come together, tell their stories, and remember what it feels like to create something real.

by Kara Martinez Bachman

Musicians and event organizers Sandy and Greg Cormier have certainly made a mark on the bluegrass community of central Maine. For the past 34 years, they have put their hearts and souls into creating familyoriented gatherings that welcome some of the best in bluegrass to perform on stage.

The Blistered Fingers Festival occurs twice yearly, in June and August. Next up is the fest, which will take place August 21-24 at the Litchfield Fairgrounds in Litchfield, Maine. It features a nice lineup of performers, including headlining act Rhonda Vincent and the Rage, The Gibson Brothers, and more.

“We’ve got a variety of everything. It’s a nice, clean, family event,” explained Sandy Cormier.

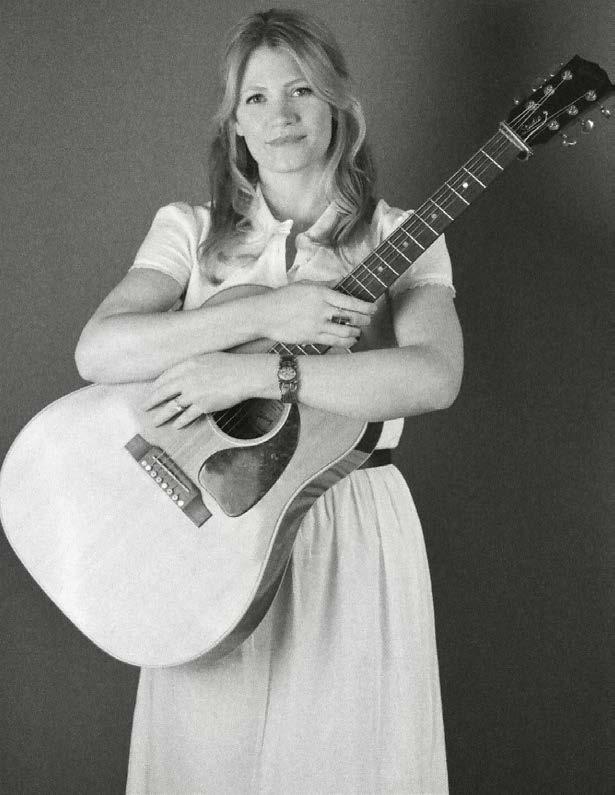

She said the festivals are a true family affair, not just for attendees, but also for the organizers. It’s all put together with a very small group of family members and friends who consider it a labor of love for the music they enjoy the most. Cormier and her husband and other family members perform onstage in the Blistered Fingers Family Bluegrass Band. She’s the lead vocalist and guitarist, and her husband, Greg, picks and strums banjo. Back in 1998, 1999, and 2000, they were named “Maine’s #1 Bluegrass Band” by the Maine Country Music Association, and in 2004, 2005, and 2006, they were voted “Bluegrass Band of the Year” by the Maine Academy of Country Music. They have performed extensively across the northeastern U.S.

and in eastern Canada. They, of course, take to the stage themselves during each festival.

“We like to keep it all traditional acoustic bluegrass,” Cornier explained about how they choose acts for each fest and use a survey to get ideas for future lineups. She and her husband find some acts while traveling and happen upon great new music.

In addition to Rhonda Vincent and The Gibson Brothers, the rest of the August lineup includes Nothin’ Fancy, The Kody Norris Show, Dave Adkins Band, Katahdin Valley Boys, Back Woods Road, The Seth Sawyer Band, Beartracks, Robinson’s Gospel, and, of course, Blistered Fingers.

The event features a three-day “Kids Academy” on Thursday through Saturday, where kids get onstage for a group performance after two days of learning to make music. The fest offers affordable camping, with access to free hot showers. There’s also a free Sunday morning “Gospel Sing and Jam.” In the spirit of a true family environment, kids under age 16 are admitted free with an adult. Tickets are available for the entire fest (purchased for a discount ahead of time, or at the gate), or for individual days. More information on pricing, performance dates and times, and camping and parking info may be found by visiting Blisteredfingers.com.

For Cormier, it sounds like these festivals aren’t just events; they’re a way of life. A

culture.

“Music is such a big part of everybody’s life,” she said, of why she loves bluegrass so much. “It brings that safe family atmosphere…it’s like a family reunion.”

“The whole atmosphere brings warmth. It’s just peaceful,” she added, about the community she holds dear.

For Cormier, the main ingredients in the overall recipe for bluegrass are “the stories, and the harmonies. It’s just the beauty of it all.”

by Candace Nelson

Being nominated for a James Beard Award is an incredible honor—one that represents far more than a single moment or achievement. It’s a recognition of years of dedication, creativity and resilience.

For many in the culinary world, the acknowledgment is the pinnacle of success. It’s a dream that validates the countless hours, the passion poured into every plate, and the commitment to excellence. Even if that nomination does not result in a James Beard Award, the honor stands on its own as a testament to outstanding work and visionary leadership in the kitchen.

This year, the 2025 James Beard Award nominees included several chefs and restaurateurs from across the Appalachian region, as defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission—a diverse area stretching from southern New York to northern Mississippi. These culinary talents represent the best of Appalachian foodways, each bringing a unique perspective rooted in local ingredients, community traditions, and bold innovation.

A native of Charleston, West Virginia, William Dissen has been a pioneer in sustainable, farm-to-table dining in the Appalachian region. At The Market Place, he emphasizes local sourcing, working closely with regional farmers and producers to craft dishes that reflect the bounty of the area. His culinary journey, which includes training at the Culinary Institute of America and experience at renowned establishments like Magnolia’s in Charleston, South Carolina, has culminated in a philosophy that celebrates Appalachian ingredients and traditions.

Katie Button’s culinary path is as unique as her cuisine. With a background in biomedical

engineering, she transitioned into the culinary world, gaining experience at prestigious restaurants including El Bulli in Spain. At Cúrate, she brings authentic Spanish tapas to Asheville, blending traditional techniques with local Appalachian ingredients. Her dedication to excellence has earned her multiple James Beard nominations and a reputation as one of the region’s most innovative chefs.

Ashleigh Shanti is known for her exploration of Black Appalachian foodways, creating dishes that honor her heritage while pushing culinary boundaries. At Good Hot Fish, she reimagines traditional fish camp fare, offering items like shrimp burgers and hush puppies infused with cultural significance. Her work not only delights the palate but also tells a story of identity, resilience and community.

Silver Iocovozzi brings Filipino flavors to the table at Neng Jr.’s, an intimate 18-seat restaurant in West Asheville. ”The menu is a product from Chef Silver Iocovozzi’s perspective as a second generation immigrant, and a person with crossover in the American South and Manila, Philippines with experience in classical genres, new techniques, and general interest in global food traditions and histories,” reads the website. Dishes are crafted with authentic ingredients, reflecting a deep connection to place and heritage. Iocovozzi’s approach creates a unique dining experience that resonates with both tradition and innovation.

Chase Collier’s culinary style marries Appalachian influences with Italian traditions,

emphasizing the use of fresh, local ingredients to create dishes that resonate with the region’s heritage. At Ristorante Abruzzi, he crafts menus that highlight the synergy between these two rich culinary cultures, offering a dining experience that is both familiar and novel.

At Apteka, chefs Kate Lasky and Tomasz Skowronski offer a modern take on Eastern European cuisine, presenting a fully vegan menu that challenges and delights diners. Their innovative approach has garnered national attention, with dishes that pay homage to their heritage while embracing contemporary culinary trends. Apteka stands as a testament to the evolving food scene in Pittsburgh and the broader Appalachian region.

Chef Wei Zhu brings authentic Sichuan flavors to Pittsburgh at Chengdu Gourmet. With

a deep understanding of traditional Chinese cooking and a commitment to quality, Zhu offers a menu that is both bold and nuanced. His dedication to his craft has earned him multiple James Beard nominations, reflecting his impact on the culinary landscape of the Mid-Atlantic region.

These chefs exemplify the dynamic and diverse culinary talent emerging from Appalachia, bringing national attention to the region’s rich food traditions and innovative spirit. Their recognition by the James Beard Foundation not only honors their individual achievements but also highlights the evolving narrative of Appalachian cuisine on the national stage.