Keith Barnacastle • Publisher

Richelle Putnam holds a BS in Marketing Management and an MA in Creative Writing. She is a Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC) Teaching Artist, two-time MAC Literary Arts Fellow, and Mississippi Humanities Speaker. Her fiction, poetry, essays, and articles have been published in many print and online literary journals and magazines. Among her six published books are a 2014 Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards Silver Medalist and a 2017 Foreword Indies Book Awards Bronze Medal winner. Visit her website at www.richelleputnam.com.

Rebekah Speer has nearly twenty years in the music industry in Nashville, TN. She creates a unique “look” for every issue of The Bluegrass Standard, and enjoys learning about each artist. In addition to her creative work with The Bluegrass Standard, Rebekah also provides graphic design and technical support to a variety of clients. www.rebekahspeer.com

Susan traveled with a mixed ensemble at Trevecca Nazarene college as PR for the college. From there she moved on to working at Sony Music Nashville for 17 years in several compacities then transitioning on to the Nashville Songwritrers Association International (NSAI) where she was Sponsorship Director. The next step of her musical journey was to open her own business where she secured sponsorships for various events or companies in which the IBMA/World of Bluegrass was one of her clients.

Susan Marquez is a freelance writer based in Madison, Mississippi and a Mississippi Arts Commission Roster Artist. After a 20+ year career in advertising and marketing, she began a professional writing career in 2001. Since that time she has written over 2000 articles which have been published in magazines, newspapers, business journals, trade publications.

Singer/Songwriter/Blogger and SilverWolf recording artist, Mississippi Chris Sharp hails from remote Kemper County, near his hometown of Meridian. An original/founding cast member of the award-winning, long running radio show, The Sucarnochee Revue, as featured on Alabama and Mississippi Public Broadcasting, Chris performs with his daughter, Piper. Chris’s songs have been covered by The Del McCoury Band, The Henhouse Prowlers, and others. mississippichrissharp.blog

Brent Davis produced documentaries, interview shows, and many other projects during a 40 year career in public media. He’s also the author of the bluegrass novel Raising Kane. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Kara Martinez Bachman is a nonfiction author, book and magazine editor, and freelance writer. A former staff entertainment reporter, columnist and community news editor for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, her music and culture reporting has also appeared on a freelance basis in dozens of regional, national and international publications.

Candace Nelson is a marketing professional living in Charleston, West Virginia. She is the author of the book “The West Virginia Pepperoni Roll.” In her free time, Nelson travels and blogs about Appalachian food culture at CandaceLately.com. Find her on Twitter at @Candace07 or email CandaceRNelson@gmail.com.

A Philadelphia native and seasoned musician, has dedicated over forty years to music. Starting as a guitar prodigy at eight, he expanded his talents to audio engineering and mastering various instruments, including drums, piano, mandolin, banjo, dobro, and bass. Alongside his brother, he formed The Young Brothers band, and his career highlights include co-writing a song with Kid Rock for Rebel Soul.

Stephen Pitalo has written entertainment journalism for more than 35 years and is the world’s leading music video historian. He writes, edits and publishes Music Video Time Machine magazine, the only magazine that takes you behind the scenes of music videos during their heyday, known as the Golden Age of Music Video (1976-1994). He has interviewed talents ranging from Ray Davies to Joey Ramone to Billy Strings to Joan Jett to John Landis to Bill Plympton.

by Jason Young

The day Molly Clair’s parents bought her a mandolin, they unleashed a hidden talent onto the bluegrass world. Born and raised in Howell County, Missouri, Molly, now eighteen years old, has already recorded her debut album, Echoes in Time, secured the role of junior Vice President of Tomorrow’s Bluegrass Stars (TBS), and been inducted into the George D. Hay Society.

Clair is honing her collaborative skills under the guidance of Nashville record label, Billy Blue Records. “They have been helping me set up co-writes and learn the ins and outs of the industry,” the recent high school graduate explains.

The budding songwriter is thrilled. “I have been able to write with Caroline Owens, Mike Richards and Mark BonDurant.

“We had a really fun time writing together,” Clair shares about collaborating with BonDurant. We wrote a song that may or may not be released. It’s about a time where I just graduated high school and I am learning to trust God with this next stage in my life.”

After a 2024 Starvy Creek Bluegrass Festival performance, during which The Queen of Bluegrass, Rhonda Vincent, joined Clair on stage to sing “All American Bluegrass Girl,” Back Forty Studios owner Darrell Turnbull approached her.

“After my performance, [Darrell] came up and asked if I want to record an album for free! My mom was with me, and we were both like, What on earth? After Rhonda Vincent jumped up on stage with me. Now, this is happening?”

Coming onboard to produce her debut album Echoes of Time was bluegrass star Clay Hess. “That was incredible when I found out Clay would be helping with the project too.”

Rhonda Vincent sang duet with Clair on the Dolly Parton Classic “Coat of Many Colors.” “[Turnbull] said he could get Rhonda on the album somehow,” recalls the young singer. “That’s one of my family’s favorite songs. It’s been an inspiration to me and the message behind it is really good.”

Clair will be doing shows during the summer and fall months.

“I like playing at Farmer’s markets on the weekend when I’m not writing or I don’t have any other shows,” adding, “I’ll be playing on July 4th in Rosin, Kentucky.”

Although she traveled as far as Raleigh, North Carolina, where she performed at the 2024 IBMA, she preferred to stay local.

“I try to stay in Missouri to build my home base,” shares the eighteen-year-old mandolinist. “I have traveled to Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky.”

The Missouri-born singer says she is making frequent trips to Nashville. “A lot of people in Nashville are kind of watching me and trying to figure me out still!

“Most of the time, I post updates of where I’m going,” Clair says about her website. “People can see what I’m doing and keep up with where I’m at.”

Clair’s mom helps. “She handles the bookings and connecting with interviews. That’s been really helpful,” explains Clair, who says she oversees getting the set lists together. “I do still involve myself in [management] because I want to pick where I’m playing.”

Clair grew up singing in church and says a school trip changed things.

“In the fourth grade, we went to Silver Dollar City and saw Rhonda Vincent &The Rage for the first time. I told my mom that day, I want to be just like her.”

Clair’s parents bought her first mandolin. “They were skeptical at first. My mom kind of played it off since I was young,” Clair remembers.

“I started taking mandolin lessons with Corina Baker (The Baker Family). I just kept on doing it and here I am!” [laughs]

Citing Bill Monroe, Ricky Skaggs, and Sierra Hull as Madolin influences, Clair says Dolly Parton, Whitney Houston, and Patsy Cline inspire her, “through their versatility. Patsy Cline cannot be replicated. I think she is someone who vocalists should try to take inspiration from. I hope I can sound like her someday.”

Clair’s music resonates with younger listeners. “Local kids have started listening to my music. What I’m aiming to do is make my version of bluegrass more approachable for kids.

“Kids think that bluegrass is old hillbilly banjo music, but it can be a lot more enjoyable,” explains Clair, who wants to add other instruments and styles to her music.

Clair is working towards building her reputation as a songwriter.

“There aren’t a lot of girls my age who release music. Although I’m eighteen, I want to be taken seriously!”

by Kara Martinez Bachman

There’s nothing better than a good story, and the storytelling is strong on St. Simons Island, Georgia. It’s a story of a resilient ministry, touching the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors, if not millions. It’s a story about nourishing souls and delivering respite.

The story’s main narrative centers on Epworth By The Sea, a nonprofit conference, retreat and vacation center on St. Simons Island. For 75 years, the center has hosted large events such as Bible study groups, government, law enforcement and military groups, corporate meetings and conferences, family reunions, choir retreats, children’s camps, ladies’ and men’s civic groups, and more. It also functions as a hotel for individual visitors.

“We have 100 acres of beautiful retreat center,” explained Tiffany Flavell, who manages Epworth’s sales and reservations. “You can have your activities on the Golden Isles of Georgia. This area is called the Golden Isles because we have the most beautiful golden marshes.”

As a premier conference center on the coast of Georgia, Flavell said they host several hundred groups a year, “and roughly 100,000 visitors a year. We also function as a hotel. We are in our 75th year this year.”

For 25 of those trips around the sun, Flavell has devoted her time, heart, and soul to Epworth, which she believes in wholeheartedly.

“Epworth is a hospitality ministry,” she explained. “We all take our personal ministry seriously. We have a wonderful staff that has servants’ hearts.” In short, they are here to serve.

“We’re affiliated with the Southern Georgia Conference of the United Methodist Church,” she explained. Some nonprofit work is about giving life experiences to those with limited opportunities to live fulfilling lives. One example is Miss Ella’s Camp for Special People, an annual special needs adult camp.

“It is their time to be with other people, to socialize. Most of them live in group homes or with elderly parents.” Flavell said the respite granted to caregivers during camp time – and the opportunities to socialize for camp participants – become landmark, lifeenhancing events for the campers.

There’s also a children’s summer camp, and the nonprofit raises funds to help families who can’t afford to give their kids this experience. Flavell said the center emphasizes Christian values and charity but welcomes religious or secular groups; everyone is welcome.

The storytellers illustrate and expand this great 75-year Epworth By The Sea story. Once a year for 11 years now, professional tellers of tales have descended upon the retreat center both to share stories and to live out new experiences. They come for the St. Simons Storytelling Festival, happening next from February 13 through 15, 2026. Storytellers Flavell described as “world-class” will present their stories and share meals and social time with attendees. It’s a time for entertainment, learning, and forging new connections and new life experiences. It’s a time for reveling in storytelling as an art form and observing masters. Flavell said, “The fellowship of it is really spectacular.”

“February is wonderful here on the Island,” she said about the month the annual event is held. “A lot of times, you can even go to the beach.”

As far as facilities go, Epworth offers five different motel buildings with a total of 235 rooms, with some located on the Frederica River; 22 youth-style bunk cabins; 35 meeting rooms of various sizes; an onsite museum; bike rentals; tennis courts; pickleball courts; bonfire pits; a large athletic field for soccer and other sports; and more. There are also two piers, where Flavell said people can do a bit of saltwater fishing.

Find out more about the center by visiting Epworthbythesea.org and the storytelling fest by visiting Stsimonsislandstorytellingfestival.com.

Although most stories eventually have an ending, staff and volunteers hope the center’s story continues. Flavell is doing her part to ensure Epworth continues to do good work in another 75 years.

“I love sharing Epworth by The Sea with everyone, however I can,” she said. “We are here to serve.”

by Stephen Pitalo

Before taking pen in hand to write jokes for “The Tonight Show,” Oscar-winning scripts and Tony-winning Broadway shows, the late Marshall Brickman had made his bones in the folk music world on stage, on television, and even on one of the most famous movie soundtrack albums ever. A skilled banjo, fiddle, and guitar player, he followed a bluegrass path from Brooklyn to Wisconsin and around the world before heading to Hollywood and returning to New York via the Great White Way.

Born August 25, 1939, in Rio de Janeiro to American parents Pauline and Abram Brickman—his father an immigrant from Poland—Marshall moved with his family to Flatbush, Brooklyn, at age four. He grew up in a postwar neighborhood where kids played stickball in the street and folk music thrived in the parks. He graduated from Brooklyn Technical High School in 1956, made the honor roll, and ran audio for WNYE. By then, his weekends were filled with bluegrass jams in Washington Square Park, often with childhood friend Eric Weissberg.

At 18, Brickman traveled to Moscow for the Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students for Peace and Friendship in 1957. “For 30 bucks, you got to fly to Russia, stay in a hotel,” he recalled. “For two weeks, eat a lot of caviar. And if you had a little talent or a skill other than a scam, they let you do it. I played ‘Earl’s Breakdown,’ [on banjo] which is a tune by Earl Scruggs. I won a prize. I won a gold medal because they had never seen or heard anything like this.” That gold medal still sat years later “on my father’s television

set in Miami Beach next to the Oscar.”

Brickman and Weissberg would cross musical paths for decades as they attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Brickman studied science and music and, for a time, considered a career in medicine.

“Actually, I’m proud to say I had the highest-grade point of anybody who was ever suspended for political reasons from the University of Wisconsin for a semester,” Brickman said with trademark deadpan during an interview for The Writers Guild Foundation in 2020, also noting that he briefly worked in the pathology department at Wisconsin General Hospital. This job promptly ended his medical ambitions. “That’s what cured me of ever wanting to be a doctor,” he said. “I did steal, however, a lot of linen for my friends.”

Despite that early detour, Madison was where Brickman’s musical life ramped up to full speed. “Our apartment was a magnet for the folk music scene in Madison,” he recalled. “We would play Saturday night at the local bar in Madison, but mainly it was just for our own amusement.” When a teenage Robert Zimmerman passed through town en route from Hibbing, Minnesota, to New York City to become Bob Dylan, he stayed at Brickman’s place. “He came in his suit

in a thin tie and didn’t play the guitar. He played the piano. He was a taciturn young man.”

After graduation, Weissberg—already playing with the well-known folk trio The Tarriers—asked Brickman to join. The Tarriers had once featured actor Alan Arkin, along with original members Eric Darling and Bob Carey. Their 1956 hit “The Banana Boat Song” (released just before the Harry Belafonte version) had made them household names. By the time Brickman joined, the lineup had evolved, with Weissberg now on banjo. “The Tarriers were like the Ink Spots,” he quipped. “The name remained the same, but people went through it like a car wash.” Besides Weissberg, Brickman was a bandmate with Clarence Cooper, who had appeared in the award-winning docudrama The Quiet One.

Brickman toured with The Tarriers on the circuit, appearing at clubs like The Bitter End in New York, playing colleges, and even performing live on the landmark TV show Hootenanny. “Remember the fifties and the early sixties when by act of Congress everyone around 18 years old had to have a guitar?” he joked on Late Night with David Letterman in 1983 about the folk explosion of that time. “I did that instead of real work.”

After The Tarriers disbanded in 1965, Brickman joined another short-lived folk supergroup The New Journeymen, formed by John Phillips with his new partner Michelle Phillips. “He wanted to put together a group… and did I wanna join? And I said, sure, why not? I didn’t have an offer from Goldman Sachs.” The group dissolved within the year, with John and Michelle forming the multiplatinum group The Mamas & The Papas. At the same time, Brickman, citing the couple’s anger management issues, moved on, content and grateful to have “escaped that burning building.”

Though his folk career had ended, his banjo playing would reemerge unexpectedly. Brickman and Weissberg had recorded an instrumental album titled New Dimension in Banjo and Bluegrass for Vanguard Records in the early 1960s. When Weissberg got an unexpected hit with “Dueling Banjos” from the film Deliverance in 1972, New Dimensions was repackaged with “Dueling Banjos” and another song added and rereleased in 1973. Titled Dueling Banjos From The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack Deliverance And Additional Music, Brickman’s playing suddenly had a new audience, even though he was already onto his career’s next chapter as a successful humorist who led the writer’s room for “The Tonight Show.”

Another track from those sessions found a second life sixteen years later when the Beastie Boys hooted and hollered over a 30-second sample of “Shuckin’ the Corn” for their “5-Piece Chicken Dinner” track on 1989’s hip-hop masterpiece album Paul’s Boutique.

Reflecting on the folk boom years later, Brickman marveled at the movement’s cultural reach. “I think people don’t realize what a phenomenon folk music was in the early sixties,” he said. “It was a big movement. Quite discrete and distinct from the early rock and roll stuff.”

Of course, it’s the screenwriting career that ultimately defined his fame. He wrote Annie Hall and Manhattan with Woody Allen, wrote and directed Simon (coincidentally starring his Tarriers predecessor Alan Arkin), Lovesick and The Manhattan Project, and then, nearly 20 years later, co-wrote the book for the Broadway smash, Jersey Boys. Despite the accolades, Brickman always clarified that music lit his creative fire first.

“I keep telling my kids that my life is no example of how to plan a life,” he said. “I wanted to go to a populist college where they had banjo playing.”

Marshall Brickman died November 29, 2024, but left a legacy that echoes like a high lonesome harmony. Long before his Hollywood life, he embodied the very soul of bluegrass—unpredictable, unpretentious, and utterly alive in the moment. From Flatbush to Madison, from Moscow to the movie screen, Brickman followed the strings wherever they led, trusting the tune over the map. In the most authentic bluegrass tradition, he forged a path with no plan but plenty of heart, proving that playing what’s true to you can put you on the road to an incredible life.

by Kara Martinez Bachman

Country/Americana/bluegrass singer-songwriter Sara Jean Kelley loves the natural world, values family roots, and continues to explore varied musical landscapes. Some of her solo work has been described as having a “dark sensibility” and “slightly melancholic sense of humor,” but don’t be fooled; the versatile singer with a husky tone to her voice is as at home in singing alternative country as she is with delivering bluegrass harmonies.

While she loves singing and instrumentation, Kelley said she gets excited about writing lyrics. From an early age, she’s been focused on this in the music she loves.

“The way I fell in love with songs is through the words,” she explained.

As a young girl, she was lucky; her childhood home was filled with music and musicians. A Nashville native, her upbringing involved constant exposure to the Nashville music scene as the daughter of singer-songwriter Irene Kelley. Being surrounded by inspiration was a daily happening. Her mother is a performer and has also penned songs for some of the big names in country music.

While Kelley said she grew up “listening to The Carter Family and Lester Flatt,” she’s “always leaned more toward the singer-songwriter stuff, like Patty Griffin.”

It’s no doubt partly due to the example of her mom’s penchant for crafting words. She’d see it and hear it in the house. Not just from her mother, but from so many other musicians. They were always at her childhood home.

“We’d host jams at our house,” Kelley said. She said when her mom would be at Nashville’s legendary Station Inn when she was a baby, she’d be there, too, sitting on someone’s knee. The business was inextricably tied to her early years, and choosing a career in performance was a natural progression.

Kelley’s first solo records started over a decade ago with her first record release, which she described as “more country” than later recordings; it was heavy in dobro and pedal steel. Her next work veered into what she calls a more rock-oriented collection. She said it was “more energetic, more produced.” It wasn’t until her third release that she felt she hit her perfect groove connecting to what she loves most. “Black Snake” – released in 2021 – was an EP of independent Americana that, up until that point, best defined Kelley as an artist. It had the most apparent singer-songwriter vibe. “I’ve been performing off that [record] the last few years,” she said.

“I use a lot of natural imagery. I’m a metaphor junkie,” she laughed, talking about what lit a spark for her creatively.

Right now, she’s mainly focused on a new project: Women of Kelley. For the first time, she has teamed up with her mother and sister (Justyna Kelley) to form a female bluegrass trio. She still gets to do the writing she loves, but this time, it’s a collaborative effort. That group dynamic is one of the things she likes about this new project.

“The thing that’s the best is just having a built-in support system. It was always just me,”

Kelley said, of the solitary nature of doing solo work. “But now, not everything that needs to be done is on just one person. It’s also an excuse to spend more time together.”

Women of Kelly have released a single, and Kelley said that while there’s no set date as of now, the full album—produced by Grammy Award-winning producer Shannon Sanders—is expected to drop before the end of 2025.

She’s excited to see where Women of Kelley goes in the future, but still has plans of her own; she hopes to put out another solo singer-songwriter record soon. When the pen and paper beckon, there’s no stopping a writer who wants thoughts of the inner world to become a sonic reality. When those thoughts reflect the richness of the natural world, that reality is even more meaningful. Themes of nature have always been a passion in both country and bluegrass, and Kelley is a part of that continually evolving tradition.

by Susan Marquez

As they regroup and recharge in East Bay (the eastern region of the San Francisco Bay Area), sisters Leah Song and Chloe Smith gather energy to continue their unexpected musical career as a globally recognized Americana and world folk ensemble. Heady stuff for a couple of sisters who grew up playing music at home with family on their back porch in Georgia.

“We had not planned on pursuing a music career,” explains Leah. But fate had other plans for the duo who first played fiddle and banjo melodies at family dinners and farmers markets. “We come from a big musical family. Our mother plays fiddle, and our dad plays guitar. They played in contra bands and took us to festivals and contra dances. We probably played music in our home forty hours a week.”

In their early twenties, the girls made a recording project as a surprise holiday gift for their parents. “We recorded our rendition of the songs they had taught us.” The recording was a way to document and preserve their music as a keepsake for their parents.

Soon after, they were invited to participate in a concert in Atlanta called Atlanta Celtic Christmas, featuring several string bands playing different genres of music. “We were considered the ‘voice of young Appalachia,’ ” says Leah. “James Flannery was the host, and Alison Brown, Joe Craven, and J.J. Sheridan played.” The concert was on the campus of Emory University, and the girls were billed as Appalachian hipsters Leah and Chloe Smith (R.I.S.E.). “We played with our mom’s band,” Leah says. “There were 700 people in the audience, and we were terrified. We had never sung into a microphone, and we had no stage presence yet. We were just tossed out there and told to play.” The girls were a hit, and to their surprise, they sold all their CDs. “We got invited to play at more shows, so we kept going.”

But there was no real plan. “We weren’t sure what we wanted to do,” Leah recalls. “We kept our day jobs, working in restaurants, and going to college.” But the more they played, the more demand there was for their unique style of music. “We just kept growing, and it all happened because of a one-off art project.” That resulted in officially starting a band called Rising Appalachia.

In the band’s early days, the sisters busked in New Orleans, where they lived for several years. “We did a lot of writing while we lived in New Orleans.” They also began to find their interpretation of Appalachian music, combining elements of classical, southern gospel, soul, folk, jazz, hip-hop, and other genres. They were also influenced by traveling and studying indigenous cultures in places

like Eastern Europe and Southern Mexico and through work in activism, which includes, among other issues, environmental and food justice, social and economic stratification, and cultural appropriation. They have learned to use their voice for social change and creative expression. “We have certainly been influenced by Irish ballads and traditional folk music from our travels.”

They began spending time with rural Appalachian musicians and eventually moved to the Asheville area of Western North Carolina, which gave them a stronger sense of their musical roots. “We were raised on Southern Appalachian music, so when we left New Orleans, we wanted to live near family in Georgia, and be immersed in the roots of this music, which to us is about gathering, music-keeping, and storytelling. We have a foothold in that part of our life and lineage which is an important part of what informs our music.” The Western North Carolina area is special to Leah and Chloe because it’s where they record, at Echo Mountain, and where they play at the Salvage Station venue. “That’s where we did our first festival.”

Hurricane Helene was a major event in their lives. “My home fared quite well, all things considered,” Leah says. “We had nearly 60 trees down in our neighborhood, and everyone was surging on a shoestring and a prayer. Chloe and her family had it really hard. They had no way of communicating, so they didn’t hear the warnings to evacuate. When the water began rising, they had to walk through two miles of mud to get out, and that was with a toddler. We lost contact with each other for days, which was terrifying.” They finally found each other, and for a few weeks, seven people stayed in Leah’s twobedroom cottage with no electricity or water. At the same time, however, Leah says it was revitalizing to see how the community rallied to help each other.

They plan to return to Asheville and Western North Carolina to commemorate Helene’s first anniversary. “It’s going to be several days of cleaning up, presenting concerts, and having a community catharsis and celebration of survival.”

Rising Appalachia has released two bodies of work in the past two years. Folk and Anchor is a collection of cover songs that tells the story of our writing influences, including artists like Bob Dylan and Beyoncé. They also did a ten-year anniversary rerelease of Wider Circles with the addition of the song “All Fence, No Doors,” written when the sisters lived in New Orleans. “It was written after Katrina. We had never released it, and it had eerie ties to Hurricane Helene. It’s weird when you write a song at a certain time in life, and it takes on a whole new meaning later on.”

Accompanying Leah and Chloe as full-time band members are David Brown (baritone guitar and stand-up bass), Duncan Wickel (fiddle, cello, harmony vocals), and Biko Casini (percussion). Rising Appalachia plans to release a new album after a fall southeastern tour. “It’s our first full studio album in many years,” says Leah. “It has traditional Appalachian fiddle medleys, Irish ballads, and a ton of original music.” The album, Trade My Troubles, will be released late fall.

It looks like this music thing may work out for them after all.

A. P. Carter Highway, Hiltons, VA 24258

@carterfamilyfold

Kody Norris Show

November 1 | 7:30 pm

ETSU Old Time Ramblers

November 8 | 7:30 pm

Russell Moore & IIIrd Tyme Out

November 15 | 7:30 pm

Whitetop Mountain Band

November 22 | 7:30 pm

Carson Peters & Iron Mountain

November 29 | 7:30 pm

For more information

Scan the QR Code

by Susan Marquez

My introduction to Moonshroom began with a Google search. I found their website, and on the home page it boldly proclaims, “A Lunar Fiesta of Cosmic Twang.” Below that heading is a video. Of course, I pressed *play.* For the next three minutes and 47 seconds, I couldn’t take my eyes off my computer screen. A colorful explosion of visual excitement combined with a catchy tune made me want to “Party on the Moon” with the band called Moonshroom.

The brainchild of Jake Keegan and Lily B. Moonflower, Moonshroom is a Kansas-based band that channels futuristic cosmic grooves and deftly melds them with traditional bluegrass to create an expansive, improvisational vibe while honoring the roots of the music they play. Think of it as a jam band with plenty of creative energy and soul. Jake and Lily have been playing together for seven years, combining projects for the past three years to form Moonshroom. The name came to them during a camping trip a few years back. “Jake and I toured the West Coast as a duo, camping a lot along the way,” recalls Lily. “One night, we were on Mount Shasta, kicking names around for the band. We looked up at the full moon and decided it looked like a mushroom. We both love mushrooms…we had recently stopped at a roadside mushroom stand on Highway 1 and bought big porcini mushrooms. And in San Francisco, we found a huge amount of chickin-the-woods mushrooms in the woods. Mushrooms pretty much represent our music and vibe. They are so well grounded and down-to-earth, but they can also be a bit spacey.” They met while working on separate projects. “Lily asked me to record on her album, and we liked our musical chemistry,” says Jake. Along the way, they fell in love, marrying in early summer. “It’s cool that music brought us together,” he says.

Their diverse musical styles, along with the diverse musical backgrounds of their band members, have helped to create a unique sound for the group. The elected array of influences gives the band a pop-Americana-roots-bluegrass-cosmic blend that audiences have embraced at festivals and concerts. “We are regular musical social butterflies,” laughs Jake. “We like to play respect to traditional music, but we also enjoy experimenting with pushing boundaries. I guess you’d call it progressive bluegrass, expanded with rock stylings. I like that we are free to explore creative expression, which is really what is at the core of this project.”

The band’s debut album, Take a Trip, invites listeners into “an atmosphere of spontaneity, acceptance, and unity.” Lily says the album includes all the original music pulled from the forty songs they play regularly at gigs. “We narrowed it down to ten songs that tell people who Moonshroom is. The album takes people on a musical trip, and we hope people listen to it from beginning to end.” The album was recorded at Element Recording Studio in Kansas City, with Joel Nanos as the engineer.

Lily and Jake hope the band has success touring this season. “When the hype of the release dies down, we’ll look at recording a second album. We launched a Kickstarter campaign to get the first one done and exceeded our goal by a lot thanks to our amazing family and friends.

https://moonshroomband.com/

by Jason Young

Nashville isn’t one size that fits all, with maverick singer and musician Joel Timmons, whose solo debut, Psychedelic Surf Country, mixes barroom honky-tonk with a Psychedelic surf vibe.

“I watched the ‘cowboy-fication’ of myself,” says Timmons, describing his five-year stay in Nashville. “I felt like I walked back into 1958. It’s just a level of commitment to that period of music and that style of dress they really hold on to.”

The Charleston, South Carolina, native says “East Nashville Cowboy” is “autobiographical.”

“I enjoy using humor in my writing even when talking about serious stuff and real feelings. I definitely admire people like Roger Miller and Frank Zappa.

“The song isn’t meant to be a teardown,” explains Timmons about Nashville’s modernized culture. “That’s the juxtaposition of the whole thing: it’s 1958, but we’ve got Ubers and we’ve got fancy coffee.”

Despite recording in Nashville, Timmons says there was no demand to make Psychedelic Surf Country a country album.

“There’s all the best fiddlers, all the best steel players and all the history and recording studios there, but I didn’t take it as pressure to make a country record. I took it as an opportunity to explore that sound with some of the best in the game.”

Timmons says dating his future wife, then a Nashville resident and Grammy Awardwinning bluegrass singer Shelby Means, drove him to leave Charleston.

“[Shelby] said, ‘You know this isn’t working. Either I move to Charleston, or you move to Nashville. And I’m not moving to Charleston!’ It was definitely a move for love.” [Laughs.]

Timmons, who performs with singersongwriter Maya De Vitry and his hometown band Sole Driven Train, says he and Shelby were a perfect match.

“We started singing together, which became our duo, Sally & George. It was a natural vocal blend. Both of us were choir kids, so we knew about cutting off words together and opening up our vowels in the same way.”

The couple collaborated on his song “End of the Empire.” “[Shelby] wrote the first lyric with the melody. We were down in the Virgin Islands. She was floating in a little dinghy in the channel, and I was out over the reef surfing. When I got back to the boat, she sang the melody to me.

That song was one that I didn’t really know what I was writing about. I didn’t have a plan; the words just fell out and felt right.”

Timmons, an ardent surfer, felt homesick in Nashville.

“I did feel landlocked,” explains Timmons, who moved back to South Carolina with his wife, Shelby. “I loved the community; I loved the way [Nashville] made me a better musician and a better writer. I just missed the ocean so much.”

He describes the benefits of surfing. “Surfing helps me stay connected. It’s been a lifelong pursuit. I have been playing in the ocean longer than I have been playing on the guitar. It helps me find clarity, peace and my mental space.”

The surfing singer-songwriter explains why he chose Maya De Vitry to produce Psychedelic Surf Country.

“We moved to Nashville at about the same time, and I was a fan of [her band] The Stray Birds,” says Timmons, who was impressed by her work. “I just knew that she would help bring other people into the project that could help bring things out of

Psychedelic Surf Country isn’t like The Grateful Dead.

“Live, we let things stretch out a little bit for more of that jam band kind of feeling. Some of the guitar tones are kind of spacy, but most of the song lengths are under four minutes—it’s not exactly a whole psychedelic trip in there.”

Going on, “For me, psychedelics in music is about dissolving the genre lines. You know, is it country, is it rock, is it folk?”

Timmons feels that anything is possible.

“It’s really an exciting time, because there is a lot of potential and uncertainty between my record, Shelby’s record, Sole Driven Train and Maya De Vitry—and whatever else we cook up!”

Timmons teases the idea of recording a more traditional style album.

“I am kind of interested in going real acoustic with some of my [songs]. Being around Shelby and all her bluegrass buddies inspires me to make some string band music. But it took me forty-five years to make Psychedelic Surf Country,” Timmons jokes. “By the time I’m ninety, I’ll have my second [album].”

by Stephen Pitalo

The label/studio name came to him one hungry morning.

“I was eating a biscuit for breakfast, and then I thought, what about Sound Biscuit?” explained Sound Biscuit label/studio founder Dave Maggard. “For some reason, it just stuck,” he said. Later, he discovered that biscuit was also slang in the vinyl era for the pucks used to press records. “Making a record was making a biscuit,” Maggard added. “It worked out well. I’ve had so many people that I’ve given shirts or hats, and they come to me, and they say, ‘What’s a Sound Biscuit?’” Maggard said, usually answering the question at least four times a day.

“I’ve got an old ’55 panel truck with Sound Biscuit written on the side, and people will literally pull up beside me, roll down their window and want to know what a sound biscuit is.”

A name that was once a spur-of-themoment idea has created a titan in Bluegrass recording. Just off a winding stretch in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, nestled near the wooded hush of the Smoky Mountains, sits a recording studio where songs are crafted with grit, warmth, and a little magic. This place is Sound Biscuit—a Grammy-nominated recording studio and record label that doesn’t merely record music. It cultivates, nurtures, and sends it out into the world wrapped in heart and purpose.

At the heart of it all is Dave Maggard, a man whose roots run deep in mountain soil and musical tradition. He’s not the guy who followed a business plan—he followed a calling—one that started decades ago when bluegrass legends were just neighbors stopping by for breakfast.

“I have loved music my whole life,” Maggard said. “As I was growing up, I went to see J.D. Crowe play at the Great Midwestern, Louisville, Kentucky, in 1975. I had to sneak in. I wasn’t old enough to drink beer.”

Maggard grew up in a scene where Ralph Stanley, Ricky Skaggs, and Keith Whitley weren’t icons yet—they were just guys trying to catch a meal and a break. “They were nobody back then. They were just old bluegrass musicians trying to get fed, trying to get to the next show,” he said.

After years of making music for beer money on the sidewalks of Gatlinburg, Maggard detoured into woodcarving, traveling as a sculptor and artist. But in his fifties, he circled back to the sound that never left his bones.

“I went back to school at the Recording Workshop in Ohio. I wasn’t looking for another career, I just wanted to understand the process,” he said. “When I got out, I thought, I gotta do something with this knowledge.”

That knowledge fueled the early incarnation—one room and an ISO booth— and evolved into a top-tier facility capable of everything from basic tracking to full album production, post-production mixing, ADR, voiceover, and audiobook work. Not to be limited, Sound Biscuit has partnered with Warner Bros. Studios for real-time voiceover and ADR recording. That alone would be enough to set Sound Biscuit apart, but the technology is only a tool here. The real power lies in how Maggard uses it—to create moments, to guide careers, and to make music that matters.

The label’s turning point came in 2018 when a few members of The Po’ Ramblin’ Boys showed up at Sound Biscuit to borrow mic stands. “They wanted to do a gospel album, so I said why don’t you do it on a label? Let me start a label, let’s do Sound Biscuit,” Maggard said. That album, God’s Love Is So Divine, was deeply personal and beautifully crafted. Their next project, Toil, Tears & Trouble, landed a Grammy nomination. “That trajectory to a Grammy was so outside my thought pattern,” he said. “That was a real ‘wow’ moment.”

What followed was a string of collaborations with some of the most respected names in bluegrass and country, including Doyle Lawson, Dale Ann Bradley, and Bobby Osborne. “Getting to work with Doyle Lawson doing his final album – what a privilege to be able to do that,” Maggard said.

Maggard’s approach to talent—whether rising or seasoned—is the same: respect the story, support the soul. He has a particular fondness for working with newcomers. “I love working with someone who doesn’t have a clue what they’re doing and helping them understand what they need to do,” he said. “They’ll either walk outta here and go, ‘I don’t want to do this for a living,’ or ‘this is a challenge and I really want to go for it.”

To meet the needs of these emerging voices, Sound Biscuit is preparing to launch Gravy Records, an imprint designed to guide young artists through the maze of copyrights, studio processes, and artistic development. “We’re laying the groundwork for a new leg of Sound Biscuit specifically designed to work with emerging artists… people that need that next step of help,” Maggard said. “We’ve already signed four stellar artists. Killer. We’re so excited.”

Despite its roots in bluegrass, Sound Biscuit doesn’t limit itself to one sound. The studio has recorded in nearly all genres. “We don’t just do bluegrass. We’ve worked with didgeridoos and bagpipes,” he said. “Bluegrass picked me with The Po’ Ramblin’ Boys. It wasn’t like I went out and solicited bluegrass. It just came to me and I went with the flow.”

Maggard’s belief in music as community is baked into everything Sound Biscuit does, from Kids on Bluegrass sponsorships to establishing a scholarship at East Tennessee State University. “That’s one of our main emphases,” he said. “We auctioned off a guitar last year to help raise funds.” And it doesn’t stop with donations—he’s always ready to open the studio doors when a young player needs a leg up. That generosity of spirit extends into sessions that become legends. One day, Doyle Lawson, Phil and Matt Ledbetter, Tim Stafford, Barry Abernathy, Jason Moore, and Jim Van Cleve came together to record “Resurrection Morning” for the family of the late Steve Gulley.

“We recorded Resurrection Morning here, which Vince Gill was on,” Maggard said. “We did the base here. And all these people, all of them, loved Steve.”

With every passing year, Sound Biscuit’s catalog grows, but the intention behind each note defines the label. “What I do with the label is really give them a resume and an opportunity,” Maggard said. “It’s not about me making money for the company.”

For Maggard, it’s about legacy and creating something lasting for the people around him. He doesn’t advertise or chase clients. Instead, Sound Biscuit attracts people by simply being a place they want to be.

“I want to create something that is interesting and so attractive that people want to be a part of it,” he said. “I want to work with people who want to be here.

Maggard’s focus is clear: create an environment where his team—and the artists they serve—can live full, meaningful lives doing what they love. And Dave doesn’t waste a second. He pours that time into building Sound Biscuit not just as a studio or label, but as a platform for others to thrive.

His life philosophy came into sharp focus during a conversation where a colleague demonstrated a perspective he had concerning, well, life.

“I was getting ready to make a big investment,” he said. “I’m looking at this investment, and the guy looks at me and says, ‘Let me show you something.’ He took out a measuring tape, held one end, and then handed it to me. ‘Now go to 76 [inch mark on the tape].’ I went to 76 and he said, ‘Now, the average life expectancy of a male in the United States is 76. Okay, where’s your number?’ And I’m looking at 68 and it’s like, right there, close to me, and I look at where he’s standing [at zero]. And you realize where you’ve been and what you’ve enjoyed, and then you look at what you’ve got left.”

“I want to create something that’s going to outlive me,” he said. “That’s going to provide Shane, Keith... and whoever we hire... the opportunity to do what they love. But also, if Shane’s got his kid’s soccer game, I think you need to go be there. Priorities should be their families and their lives. The happiness of being with family, that’s important.”

And that’s what makes Sound Biscuit a living, breathing testament to the idea that making music and making a life can—and should—go hand in hand. In a world full of noise, Dave Maggard has built a place where sound has meaning, and every moment counts. The great songwriting icon Warren Zevon, in his last days, was noted to say, “Enjoy every sandwich.” To that end, Sound Biscuit fills the belly, the ear, and the heart.

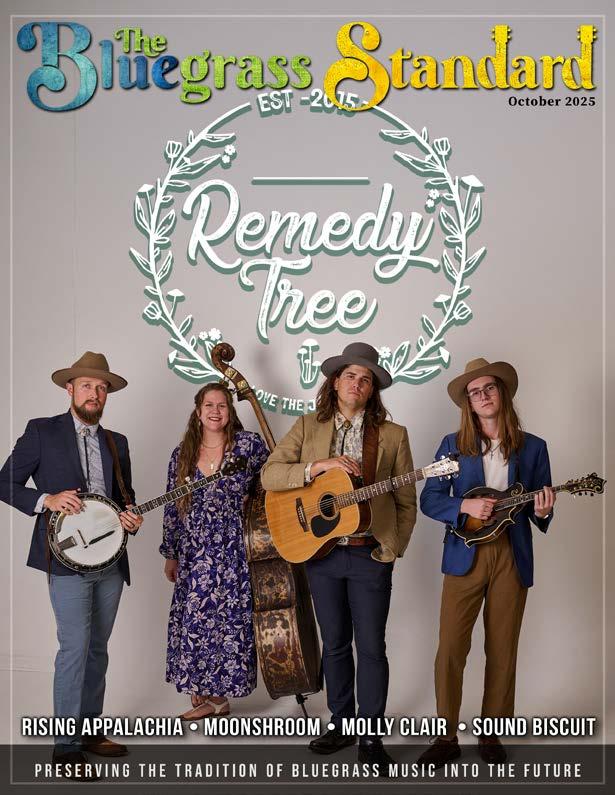

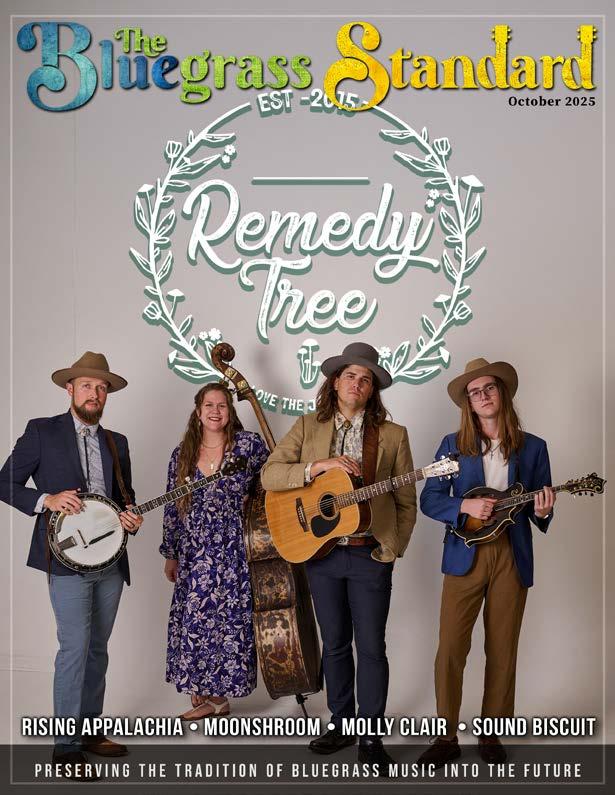

Offering a blend of folk, old time, and bluegrass, Florida-based Americana ensemble

Remedy Tree seems to enjoy a busy year. Having just released a new album in September, this ‘tree’ is growing, expanding its canopy of music and laying down fresh new roots across the worlds of Americana and bluegrass.

Gabriel Acevedo formed Remedy Tree along with his wife Abigail. According to Acevedo, the past few months have been quite rewarding. Their single, “Beyond What I Can See,” debuted at #9 on the Bluegrass Today charts.

“We’ve already sold out two listening rooms, and we’re doing really well. We just played at The Station Inn,” he said, calling that gig at the legendary Nashville venue “an absolute highlight of our career.” They were also selected as a 2025 IBMA Ramble Showcase Artist.

“Our Spotify has blown up compared to what it used to be,” he said, “and we’re just glad to be here. 2025 has been a great year.”

Remedy Tree was formed in 2015. Acevedo described its inception as “a little folky kind of indie folk project.” Over time, he said they just started “going toward bluegrass.”

“We added a banjo in the band, and that took us even more toward a bluegrass trajectory.” Acevedo said, adding that he also started studying bluegrass music and attending bluegrass festivals.

“Of course, it’s a modern Americana type of band. It’s not full bluegrass all the time, but it definitely has extreme roots in bluegrass,” he explained.

The band’s name is a combination of ideas that work well in conjuring what the genuine music of Americana is supposed to be all about.

“I was just putting words together randomly, and that one just kind of stuck with me, because our music is very healing. It’s very positive music,” Acevedo said.

“We don’t do a lot of gospel,” he added, “but a lot of my lyrics have that message in it, and it’s a message of hope. So that’s where the ‘remedy’ part came from. The ‘tree’ part…I think it was just kind of an artistic decision.” He said it’s given the whole project an “earthy” vibe.

When asked about what inspires the lyrical content of the group’s music, Acevedo said his writing is usually triggered by “waves of raw emotion.” These waves serve as inspiration. They’re often feelings associated with real-life events, and they’re pretty personal feelings.

He said the writing is “often infused with themes of chasing dreams and persevering,” with “love songs here and there.”

“For the most part, the songs are about life,” he said. “You know, one of our mottos, which was the title of our last album, was ‘Love the Journey.’ And I really think that is

the theme of the band, just loving the ride that life is – the ups and downs, and everything you learn, and everything in-between.”

Most performers can relate to the challenge of corralling the will to strive and move forward. Perseverance is a lifestyle for most who want to make a career as performers.

“I always dreamed of having a band, and making a living, making a life, with the music. There’s always a part of you that says, this feels impossible.”

He said you keep going anyway. You persevere.

“And you keep improving the things you need improving on, and before you know it, you look back and realize how far you’ve gotten,” he said.

Acevedo’s plan for the coming years is to “just keep expanding our audience and growing, playing bigger festivals and playing bigger venues, and just capturing more people into our remedy tree movements.”

Acevedo described a dynamic—a special communication with the listener—that inspires him to continue on the path.

“When there’s one person, you know, singing along in the audience…I always lock in with that one person, and it’s just…I appreciate that so much. It’s very humbling to see.”

While those special moments are a big reward, the overall journey sounds like a blast. For Acevedo, the main goal is as simple and understandable as any. He said Remedy Tree wants to “have a good time with it, have fun with it, and see where it leads.”

by Amanda Deboef

FreshGrass: More than a Music Festival, the Art of Creativity as a Way of Life

FreshGrass, a Midwest bluegrass experience like no other, happens every May when the festival takes over The Momentary at Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas. Not just another bluegrass festival, FreshGrass celebrates roots and evolution, blending the deep traditions of bluegrass with modern genres like rock, country, and blues. The past, present, and future play out on stage in real time.

Festivalgoers are treated to a rich mix: artists and makers selling their wares, musicians from local acts to headliners, jam sessions in the Red Barn, artist talks at the RODE House and even squaredancing. Each year is unique, but one thing remains constant. This year’s featured “Intimate Portrait” was with singer, songwriter, and author Rosanne Cash, the eldest daughter of the legendary Johnny Cash. Asked to describe her music, she said, “Someone else would have to answer that, though many refer to my music as Americana.” Her songs often read like poetry because she weaves nature, heartbreak, healing, and growth into her soulful lyrics.

An avid fan of Jane Austen, Cash carved out her place in music as a songwriter. She shared, “I love language that has melody. The rhythm of the writer with a particular voice. When I write prose, I write like a songwriter.” She views music as a service to others. “I consider myself to be in the service industry and feel the function of music is to open the heart.” Quoting Bob Dylan, she said, “The audience comes to

know their feelings,” emphasizing that “Authenticity is immediately recognizable and relatable.”

That authenticity radiated from her headline performance with her husband, John Leventhal, on the final evening of FreshGrass. Her raw and resonant voice and Leventhal’s harmony moved the crowd. Their set celebrated multiple milestones: Rosanne’s birthday, their wedding anniversary, and the 30th anniversary of The Wheel, a fan favorite album produced by the couple’s Rumblestrip Records.

The night before, Cash sat down with sculptor Kevin Kresse for a heartfelt conversation. Kresse, who sculpted the life-size statue of Johnny Cash now standing in the U.S. Capitol’s Emancipation Hall, shared his creative journey. He joked about the sculpture looking like Frankenstein mid-process, saying it nearly talked him out of finishing it. Cash replied, “I, too, have had to pull songs down to the metaphorical skull and start over.”

Though it was her first time at FreshGrass Bentonville, Rosanne felt right at home. “I love festivals that focus on the arts,” she said. “Everyone is looking for something ...to feel their feelings, gain access to repressed feelings, or connect with others. Music is a great connector.”

The statue unveiling held deep personal significance. Cash spoke of her father’s essence captured in bronze. She recalled her Aunt Joanne, Johnny’s legally blind sister, touching the statue to see it

for herself. An emotional day, filled with memory and meaning, Kresse quipped, “Joanne is saucy!” Cash laughed and agreed, sharing a story about meeting Roseanne Barr. “You are the reason everyone misspells my name!” Barr exclaimed, and Cash shot back, “YOU are the reason everyone misspells my name!”

Rosanne Cash’s creative life has earned her numerous honors, including an honorary doctorate from Arkansas State University. “You can call me Doc,” she teased Kresse. She loves mentoring students: “I love working with young people; they are so hungry with passion and creativity.”

She also understands the self-doubt that artists face. “I still have doubts. Doubt is part of the process... You cannot rely on inspiration striking. That is the war of art.” Her creative rituals? Long walks in nature, writing retreats in cabins, and disconnecting from screens. She even keeps a pen on her nightstand, hoping to capture dream-born lyrics.

After her talk with Kresse, the crowd moved to the main stage for boot-stomping, bodymoving performances. The warm evening breeze set the stage for a standout act: The Lost Bayou Ramblers, who also played a rare set later that night at the Tower Bar.

As sunset poured through the windows, the top floor of The Momentary erupted to life with Cajun-Creole fusion from brothers Louis and Andre Michot. Their Grammy-winning band has mixed traditional Louisiana music with bluegrass and rock for 25 years.

Though new to the Bentonville edition, the Ramblers have roots at FreshGrass Mass MoCA in Massachusetts, but began in Lafayette, Louisiana, in 1999, carrying on a family music tradition. Andre builds his accordions; Louis plays fiddle. Over time, they’ve added members, forming a tight-knit crew that primarily performs in Louisiana.

True to FreshGrass’s focus on innovation, the Ramblers travel with a solar-powered Sun Roller Stage, built after Hurricane Katrina to bring music to powerless communities. Louis explained, “FreshGrass is more than a festival; it is a way of life. It celebrates so many genres of roots music... but has lent itself to expansion over time.” Their mission? “Have fun, play music.”

Art is also central to FreshGrass. This year’s standout exhibit featured Jim Marshall’s photography of Johnny Cash’s prison concerts at Folsom and San Quentin. The intimate images transported viewers back in time.

Alejo Benedetti, Curator of Contemporary Art at The Momentary, noted the powerful timing. “It has synergy with the music program,” he said. “Jim Marshall, the Godfather of concert photography, captured a unique and intimate image, placing the viewer right there with the musician.” His friendship with Johnny Cash helped produce some of history’s most iconic concert photography.

“Cash felt Marshall was the photographer who could understand the why behind the prison concerts,” said Benedetti. Marshall’s lens humanized legends, offering glimpses of backstage nerves, pre-show rituals, and onstage passion. His work makes fans feel like

part of the story.

With its “Welcome to All” spirit, The Momentary brings global art and music to Arkansas, offering something for locals and travelers alike. FreshGrass introduces many emerging talents on the brink of success, alongside headline acts like Rosanne Cash, Lukas Nelson, and Shakey Graves.

Few places offer such an immersive blend of music, art, and community. If you’ve been to FreshGrass, you know the magic. If not, mark your calendar for May 2026. Details and lineup will be available at: FreshGrass Bentonville.

by Ted Drake

Young musicians pick up instruments across back porches, festival campsites, and late-night jams, unaware that their hands are still growing into dexterity. Though their fingers fumble through music lessons and melodies, they form identities, build community, and develop life skills from the start. For some, this early start to music leads to the spotlight. For others, it remains a quiet yet powerful lifelong companion.

The Governor’s School for the Arts (GSA) provides a formal pathway for young artists in Norfolk and Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Within the historic building, students from eight school districts gather each afternoon after spending mornings in traditional high school classrooms. They come to study dance, musical theatre, film, visual art, and music.

Executive Director Shelly Cihak and Assistant Director Deborah Thorpe often welcome visitors in the GSA lobby and start there with a tour. They show photographs of past students and proof of the school’s impact on the community. Thanks to public funding, sponsorships, and grants, students pay no tuition, and transportation is provided by each of the

students’ home districts.

The intense schedule involves students collaborating with local arts organizations, taking music technology and production electives, and participating in musical activities outside the classroom. “These kids are growing into their artistic lives,” says Thorpe,” and they’re hungry to learn.”

One of GSA’s success stories is violinist Zach Casebolt, who began playing at age five and graduated from GSA in 1999. Now based in Nashville, he’s recorded with numerous artists and recently released a solo violin album.

“GSA is responsible for my musical talents,” Casebolt says, reflecting on how the program helped shape his foundation.

For banjo player Gina Furtado, the impact of early learning in music was deeply personal and enduring. She started piano at five and banjo at eleven and says the latter “completely changed my life in just about every way I can think of.”

Music opened the doors professionally, but it also opened her spirit socially and emotionally. “It made me part of a built-in music family,” she says. Her closest relationships, including with her husband, luthier Ben Walters, were born through music. “Thanks, banjo,” she often jokes, recalling the strange, beautiful, and unforgettable moments music has delivered over the years.

Guitarist Steve Kaufman spent his early years playing the piano, cello, and electric guitar until he heard Doc Watson. Then, Kaufman dove into flatpicking. “I was eaten up with playing guitar,” he says, having now played for over 50 years. As the founder of the renowned Kaufman Kamp in Maryville, Tennessee, he shares his passion with hundreds of aspiring musicians each June. “The drive, the practice, the desire to do nothing else, that’s what it takes,” he says.

In Norfolk, the Robertson and Dunlap families prove how music transforms individuals and entire households.

Chris and Heide Robertson have five children, and at some point, each picked up an instrument, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. “There was less school, church, and swim team,” Chris recalls. “So, there was more time to play music together.” Their son Asa,

now 15, took lessons for about six months but primarily plays by ear. “Let Asa do his thing,” Chris says, and it looks like Asa did. He plays fiddle, mandolin, guitar, bass, and harmonica.

Chris has become an accomplished musician, playing bass, piano, and guitar, leading songs and mentoring others. “Music keeps the kids busy, gives them confidence, and introduces them to new people. It’s given our family something to grow around.”

The Dunlaps, Stacey and Christian and their four musically inclined kids share a similar story. Stacey, who minored in music in college, introduced her children to instruments early, with all four joining the school orchestra by fifth grade. A turning point came at MerleFest in 2022 when they bought a mandolin, a fiddle, and a banjo. By the end of the weekend, the kids were playing “I’ll Fly Away.”

School, concerts, and local jams fill the Dunlaps’ days. Their daughter, Ella, splits her time between Cox High School and GSA, studying piano and violin. “I love playing music with my kids,” says Stacey. “I feel like I’ve won the parenting lottery.”

The Robertson and Dunlap families perform as Take Your Pick, playing festivals, farmers’ markets, and regional events. In May 2025, they performed at Graves Mountain.

Beyond family jams and formal schooling, local organizations make space for young learners. The Tidewater Bluegrass Society (TBS) produced The New Cabin Fever in March 2024, a three-day festival that includes a “Kid’s Academy,” led by musician Jesse Burdick. There, the young participants learned songs together and performed on stage at the end of the weekend.

Eric Yoder, a retired doctor and TBS board member, has also played clarinet since age 10 and guitar since age 13. Now retired, he performs with Tidewater Arts Outreach, bringing music to senior living communities. “Music is still teaching me,” he says. And I get to share what I’ve learned.”

Note the similar stories throughout the bluegrass world, from school hallways to festival stages and campfire circles to concert halls. Learning music early in life develops a lifelong language of expression in addition to mastering notes. Statistics show that music cultivates confidence, discipline, connection, and joy, whether a child becomes a touring artist, a community picker, or someone finding solace in an instrument.

To quote a cliché, music is the gift that keeps giving, especially when placed in young hands.

by Candace Nelson

These restaurants — each deeply rooted in place, culture, and community — achieved significant recognition from the James Beard Foundation in 2025. While none took home the trophy, their nominations spotlight Appalachia’s culinary breadth and rising influence. More than just a nod of approval, these honors affirm that chefs and restaurateurs across Appalachia are creating food that resonates locally and nationally.

In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Fet-Fisk earned a finalist spot for Best New Restaurant, one of just 10 restaurants across the nation to do so. This Nordic-inspired seafood bar in the city’s Bloomfield neighborhood has quickly gained acclaim for its inventive approach to local ingredients, serving up dishes like grilled cabbage Caesar, spaetzle, and whole branzino, paired with aquavit-forward cocktails and natural wines. With its clean aesthetic and minimal plating, Fet-Fisk stands out for its commitment to technique and precision without pretense. Despite ultimately losing out to Minneapolis’s Bûcheron, FetFisk’s place among the finalists elevated Pittsburgh’s culinary reputation and displayed the city’s potential for boundary-pushing, ingredient-driven cuisine. It also demonstrated that Pittsburgh, long known for its blue-collar food traditions, can support and celebrate refined culinary experiences that remain true to place.

Further south in Staunton, Virginia, Maude & the Bear was nominated as a semifinalist in the same Best New Restaurant category. Housed in a lovingly restored 1926 Montgomery Ward kit-house, the intimate space is the latest project from chef Ian Boden, who coowns the restaurant with his wife and hospitality partner, Kathleen Galvin. The couple has created a space that’s equal parts restaurant and retreat. Guests who dine on Boden’s whimsical, modern tasting menus—featuring seasonal fare sourced from the Shenandoah Valley—can stay overnight at the attached boutique inn, making for a fully immersive culinary escape. Dishes might include dry-aged duck with sorghum glaze or Appalachian heirloom beans plated like fine art. While Maude & the Bear didn’t advance to the finalist round, its nomination marked a significant moment: one of the first times Staunton found itself on the James Beard radar. The recognition underscores the growing sophistication and ambition of small-town dining in Appalachia and affirms that rural settings are no barrier to culinary excellence.

Asheville, North Carolina, also made its mark this year. Leo’s House of Thirst, a cozy wine and cocktail bar in West Asheville, was named a semifinalist in the Outstanding Wine and Other Beverages Program category. Known for its tightly curated list of natural wines, small-batch spirits, and seasonal cocktails, Leo’s has become a haven for wine lovers and curious drinkers alike. What sets Leo’s apart is its sense of place – the wine

list leans heavily on producers who prioritize sustainable farming and low-intervention winemaking, while the bar’s menu often features Appalachian touches like pickled ramps, trout roe, and smoked mushrooms. It’s more than a neighborhood bar; it’s a thoughtful expression of the beverage culture emerging across Appalachia. While Leo’s didn’t make it to the finalist round, its inclusion among semifinalists reinforced Asheville’s position as a beverage destination, a city that supports innovation and depth far beyond traditional breweries and distilleries.

Even without bringing home any awards, these nominations carry substantial weight. A James Beard nod as a semifinalist or finalist can increase visibility, drive reservations, attract press coverage, and position a restaurant for future accolades. It offers national validation and encourages the region’s food lovers to support businesses defining Appalachian cuisine on their terms. For restaurants in smaller cities and towns, the impact of a Beard nomination can be transformative, helping them attract talent, investment, and a new wave of culinary tourism.

This year’s nominees also underscore the range and diversity of Appalachia’s food scene. From the seafood-forward minimalism of Fet-Fisk, to the tasting menu elegance of Maude & the Bear, to the wine-soaked charm of Leo’s, each restaurant represents a different vision of what dining in Appalachia can be. These establishments don’t rely on stereotypes or outdated notions of the region; instead, they expand the definition of Appalachian food, drawing from global influences while remaining grounded in local sourcing and storytelling. The region is not simply adapting to national trends but helping to set them.

The path to top James Beard honors is often incremental. Today’s semifinalists become next year’s finalists; next year’s finalists may go on to win. The attention gained from one nomination can ripple outward for years. Whether that ultimate win happens in 2026 or beyond, what’s clear is this: Appalachia is no longer on the sidelines of the national food conversation. It’s in the room. And the food it’s bringing to the table is thoughtful, rooted, ambitious and worth celebrating.