Ministry of Culture, Government of the State of São Paulo, through the Secretariat of Culture, Creative Economy and Industry, Municipal Secretariat of Culture and Creative Economy of the City of São Paulo, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo and Itaú present

36th Bienal de São Paulo

36th Bienal de São Paulo

Since its creation in 1951, the Bienal de São Paulo has been marked by constant renewal. Each new chapter in its history proposes a way of existing in time and space, always in dialogue with the contemporary. The 36th edition of the event, under the title Not All Travellers Walk Roads – Of Humanity as Practice, is based on a curatorial concept developed by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. Inspired by the poem “Da calma e do silêncio” [Of Calm and Silence] by Conceição Evaristo, the chief curator proposes an attentive listening to the multiple forms of humanity in displacements, encounters, and negotiations.

The Fundação Bienal de São Paulo believes that its mission is based on a central precept: relevance. This means producing meaning, generating access, and positively impacting as many people as possible. Being relevant means responding to the most pressing issues of our time while also embracing the doubts and uncertainties, in other words, asking questions. To this end, the curatorial selection, an assignment of each new board, is the first step. From there, the artists and their works unfold, chosen for their critical, aesthetic, and conceptual power, and for their ability to reflect or stress collective challenges. But no work is complete alone: the conditions for visitors to approach, interact, and find a space for exchange at the event must be created. This is done before, during, and after their visit, with educational materials, digital content, and new publications, which together broaden the experience and encourage a closer relationship with contemporary art, as well as research and audience building.

Being part of the development of a Bienal is a privilege. It’s watching art history unfold before your eyes – and seeing yourself in it. By following the birth of an exhibition of this scale, we become part of the living process of creation. From the conceptual decisions to the dismantling and the many waste treatment processes when the event is over, each stage requires precise coordination, constant dialogue, and shared responsibility between professionals from multiple fields.

This edition also has a special feature: its extended duration, from September 2025 to January 2026, prolonging its presence in the cultural calendar by one month. More than just an extension of time, it’s a matter of enhancing the possibilities for encounters. And, as always, access is free, both to the exhibition and its programming –a commitment by the Fundação to the democratization of art and the ongoing construction of an increasingly participatory cultural public.

None of this would be possible without the joint commitment of our partners, especially the public bodies and sponsoring companies that believe in the relevance of art as a way of creating a better future for everyone. And, of course, it wouldn’t be possible without the Fundação Bienal’s professionals and the large network of collaborators who diligently ensure that demanding deadlines are met, that the planned actions are rigorously executed, that the institution’s financial health is maintained, and that this jewel of modernism, the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, the main stage for all these meetings, is well preserved. It is this commitment that guarantees the permanence of a historic project that has been going strong for more than seven decades – guided by the certainty of excellence and relevance.

Andrea Pinheiro President – Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

The Ministry of Culture celebrates the 36th Bienal de São Paulo –Not All Travellers Walk Roads – Of Humanity as Practice, an edition inspired by the verses of the renowned writer Conceição Evaristo. Through the Culture Incentive Law, known as the Rouanet Law, the Federal Government is proud to be one of the producers of this important event that brings together leading artists from all over the world to engage with fundamental issues of our times, amplified by an educational program that is internationally recognized.

The visual arts have the power to confront us with the most pressing themes of our time, employing complex poetic approaches that resist simplification or easy answers. More than offering solutions, the Bienal poses questions and multiplies perspectives, establishing contact with the diverse, with other life experiences, and with different ways of inhabiting the world. Visiting the Bienal offers a chance to broaden aesthetic and ethical repertoires through the exercise of empathy involved in engaging with works of art – an essential step toward strengthening a more citizenoriented culture.

The Ministry of Culture has worked tirelessly to support the cultural sector, creating opportunities for artists and cultural workers across diverse languages and fields. Through initiatives such as the Rouanet Law, the Paulo Gustavo Law, and the National Aldir Blanc Policy for Cultural Support, this Ministry has been proud to promote projects throughout the country, strengthening the creative economy and working toward the implementation of permanent and democratic cultural policies.

The Bienal de São Paulo offers access to art free of charge, in a meaningful effort to democratize access to culture – an effort that aligns with the public policies advanced by this Ministry. Art and education are indispensable to ensuring the right to a full and critical citizenship, which belongs to all Brazilians. For this reason, the Federal Government, here represented by the Ministry of Culture, remains committed to investing in initiatives that promote full cultural engagement, so that present and future generations can access the transformative experience that art provides.

Margareth Menezes Minister of Culture – Federal Government of Brazil

For more than 35 years, Itaú Cultural (IC) has played a fundamental role in boosting the appreciation of art, culture, and education in a complex and heterogeneous society like Brazil. This role is expanded through essential partners for the development of the cultural and creative economy, such as the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

Itaú Unibanco is proud to be the strategic partner of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo – a partnership that spans the past 27 years, with this being the 12th edition held in that period – reaffirming its commitment to promoting the visual arts and their transformative role. The Bienal de São Paulo is an important meeting and exchange space for artists, curators, critics, and the public.

In this field, Itaú Cultural organizes actions for enjoyment, education, and promotion, including solo and group exhibitions that take place both at its headquarters on 149 Avenida Paulista (with free admission) and at venues in Brazil’s five regions. Highlights of the 2025 exhibitions include Carlos Zilio – A querela do Brasil, curated by Paulo Miyada, which will present a retrospective of this artist who, with erudition and irreverence, explored the tensions of Brazilian art. Exhibitions will also be dedicated to the visual artist Rivane Neuenschwander and the curator and critic Paulo Herkenhoff.

Visit itaucultural.org.br to browse the virtual exhibitions Filmes e vídeos de artistas, with experimental audiovisual works, and Livros de artista na Coleção Itaú Cultural, whose immersive and interactive features allow for detailed appreciation. At Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural (enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br) you can access hundreds of entries on figures, works, and events in the visual arts.

Being present at the Bienal de São Paulo reinforces our goal of building links with different audiences, valuing the diversity of formats, thoughts, and subjectivities, and fostering creative and critical thinking through Brazilian art and culture.

Bloomberg is proud to sponsor the 36th edition of the Bienal de São Paulo. For more than a decade we have supported the Bienal’s exceptional contemporary art exhibitions in the stunning Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion in Ibirapuera Park and around Brazil, through our partnership with Fundação Bienal. This year’s edition continues the tradition of presenting captivating and thought-provoking art installations that are free and open to the public.

Every day, Bloomberg connects influential decision-makers to a dynamic network of information, people, and ideas. With more than 19,000 employees in 176 offices, Bloomberg delivers business and financial information, news and insight around the world. Our dedication to innovation and new ideas extends to our longstanding support of arts, which we believe are a valuable way to engage citizens and strengthen communities. Through our funding, we help increase access to culture and empower artists and cultural organizations to reach broader audiences.

Bloomberg

For Bradesco, a Brazilian bank par excellence that has just celebrated its 83rd anniversary, art and culture are not only fundamental elements in the formation of a people’s identity or the construction of their intangible heritage, but also a journey of inclusion and citizenship, a healthy convergence of different points of view. It is, so to speak, a journey toward the new, but with the care to value what is special enough to be history or tradition.

Therefore, when it comes to art and culture, the boundaries between past, present, and future, between form and content, become meaningless. Everything becomes reflection and learning, everything becomes provocation and surprise.

It was on the basis of this interpretation, combined with the positive view of the role of companies in making possible what society considers important, that Bradesco became a sponsor of the 36th edition of the Bienal de São Paulo, undoubtedly one of the most important events in the country aimed at promoting the arts scene, publicizing the various expressions of art, and promoting cultural exchange, with all the good that this brings.

By participating in something that is both great and multifaceted, Bradesco shares with the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo – which has organized the event for more than six decades – the goal of democratizing access to culture, multiplying its reach and promoting the appreciation of art.

It’s a path with no end, no turning back, full of challenges and at least one certainty: the more people who take part, the better!

Bradesco

Petrobras has a history of more than forty years of continuously believing in culture as a transformational element and a source of energy for society. By supporting unique projects and longterm partnerships, we have built a relationship of respect and collaboration with producers and initiatives all over the country.

The Petrobras Cultural Program has Brazilianness as its guiding element, which is materialized in the themes, origins, curatorship, history, and characteristics of each project we select. By supporting different projects, we put into practice our belief that culture is an important energy that transforms society. We believe that through creativity and inspiration we promote growth and change.

The Bienal de São Paulo is one of the sector’s most prestigious events in the country and the world. Petrobras’s sponsorship reinforces the company’s role in promoting culture in its various forms, consolidating its position as one of the biggest supporters of the arts in Brazil.

Events such as the Bienal de São Paulo make a significant contribution to the economy, promoting innovation, creativity, and sustainability in the economic dynamic. Petrobras is an ally of Brazil’s development in its various sectors. It invests in many forms of energy, and culture is certainly one of them.

Petrobras is proud to support Brazilian culture in its plurality of manifestations, taking art to all audiences, all over the country. Because culture is also our energy.

To find out more about the Petrobras Cultural Program, visit petrobras.com.br/cultura.

Instituto Cultural Vale believes in the transformative power of culture. As one of the main supporters of culture in Brazil, it sponsors and promotes projects that foster connections between people, initiatives, and territories. Its commitment is to make culture increasingly accessible and diverse, while also contributing to the strengthening of the creative economy.

It is therefore a pleasure to be part of the realization of this 36th Bienal de São Paulo and its educational program, which explores new formats and approaches. Developed from the Invocations proposed by the curatorial team – encounters with poetry, music, performances, and debates that explore notions of humanity across different geographies – the educational program expands the Bienal’s communication with diverse audiences and extends its reach beyond the exhibition space and timeframe, in an interdisciplinary way.

With each new edition, the Bienal invites us to rethink art as an exercise in dialogue, in openness to new narratives, and as a space for learning. In this sense, it aligns with the purpose of the Instituto Cultural Vale: to expand opportunities for learning, reflection, new perspectives, and the sharing of art, culture, and education – both inside and outside museums, throughout Brazil.

Where there is culture, Vale is there.

Instituto Cultural Vale

For 110 years, Citi has been part of Brazil’s history, accompanying its transformations and driving its development. Our journey is intertwined with that of the country: we are both witnesses to and participants in a Brazil that constantly reinvents itself and moves forward.

More than a financial institution, we believe in the power of culture and education as engines for a more inclusive, innovative, and sustainable future. Investing in these pillars also means celebrating the diversity, creativity, and talent that define the Brazilian spirit.

With this commitment, we are proud, for the first time, to support the 36th Bienal de São Paulo – one of the most important spaces for artistic expression in Latin America, where Brazil thinks, feels, and reinvents itself through art.

We believe in art as an agent of social transformation. Artistic creation has the power to spark dialogue, expand horizons, and inspire new possibilities for the world. By sponsoring the Bienal, we reaffirm our commitment to culture, innovation, and all those who, through art, are building new narratives for both the present and the future.

Vivo believes in culture as a means of social transformation and is one of the most important brands supporting the visual and performing arts and music in Brazil. Art, like technology, creates connections between people and encourages the search for balance between history, nature, and time.

Vivo is currently a sponsor of the most important museums in Brazil, such as the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, the Museu da Imagem e do Som (MIS-SP), the Museu Afro Brasil Emanoel Araujo, the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM-SP), as well as the Instituto Inhotim and the Palácio das Artes, both in Minas Gerais, and the Museu Oscar Niemeyer, in Paraná.

Teatro Vivo, located in São Paulo, offers a curated selection of contemporary plays that promote reflection on current issues and value cultural diversity. In addition, it is a fully accessible space, offering resources such as translation into Libras (Brazilian sign language), audio descriptions, and trained staff, ensuring inclusion for people with disabilities and reduced mobility. In 2024, it welcomed over 50,000 people.

The brand also supports projects in the world of music that are genuinely Brazilian and regional, reinforcing its proximity with local culture at iconic and traditional events in our country, such as the Parintins Festival, Galo da Madrugada, the Çairé Festival, Lollapalooza, The Town, and Vivo Música.

The brand’s initiatives in the cultural sphere broaden access to knowledge with new ways of experiencing and learning, strengthened by the aspects of diversity, sustainability, inclusion, and education. All information is gathered and shared on the @vivo.cultura and @vivo Instagram profiles.

Vivo

Confronted with the incessant problems of humanity, perhaps it is worth dwelling a little longer on some open questions, taking sustenance from resources that allow us to dig and build answers procedurally. In this sense, art, in its many guises, offers fertile ground for critical elaborations about the world and ourselves.

The meeting of art and education – both understood as fields of knowledge – enables the torsion of time and space: it becomes possible, thus, to suspend neutralities and dilate what is precipitated in structures. How far is this approach able to infer the real and interfere in it? It allows us to (re)populate imaginaries, to unpick the universalizing statute attributed to concepts, practices, and people, and thus to carve out reality with narratives that articulate the individual and the collective, in a procedural and coherent manner regarding the issues that permeate existence.

It is according to this panorama that Sesc São Paulo and the Fundação Bienal, through the 36th Bienal de São Paulo, reiterate their long-standing partnership, a mutual commitment to fostering experiences of coexistence with the visual arts, expanding access to cultural actions and the exercise of otherness.

This partnership, which has been established and renewed for over a decade, has led to the promotion of projects such as simultaneous exhibitions, public meetings, seminars, and training for educators, as well as the consolidated itinerant exhibition with excerpts from the Bienal in Sesc units in the wider state of São Paulo. The confluence of choices and propositions is part of the institutional perspective of culture as a right, and conceives, together with one of the largest exhibitions in the country, an accessible horizon for contemporary art in Brazil.

Sesc São Paulo

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung

62 Chapter 2

Grammars of Defiances

64 Suchitra Mattai

66 Ana Raylander Mártis dos Anjos

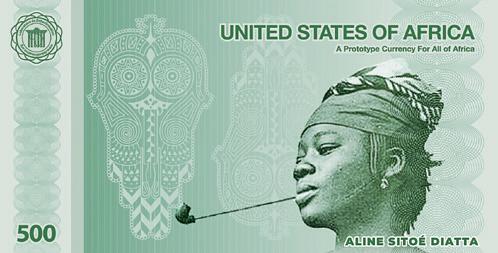

68 Mansour Ciss Kanakassy

70 Emeka Ogboh

72 Minia Biabiany

74 Forensic Architecture/ Forensis

76 Ruth Ige

78 Theo Eshetu

80 Adjani Okpu-Egbe

82 Noor Abed

84 Aline Baiana

86 Song Dong

88 Theresah Ankomah

90 Olu Oguibe

92 Leo Asemota

94 Chapter 3

Of Spatial Rhythms and Narrations

96 Tanka Fonta 98 Otobong Nkanga

Leiko Ikemura 102 Moffat Takadiwa

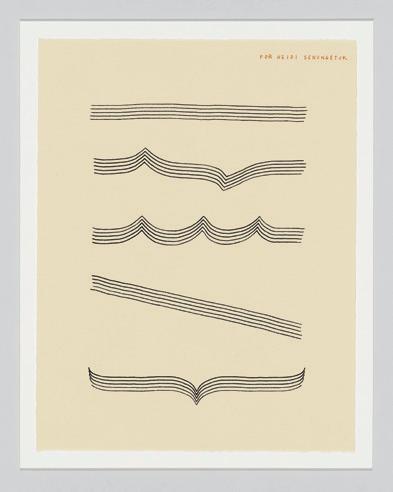

Cevdet Erek 106 Nari Ward 108 Manauara Clandestina

110 Amina Agueznay

112 Marlene Almeida

114 Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn

116 Christopher Cozier

118 Akinbode Akinbiyi

120 Wolfgang Tillmans

122 Pélagie Gbaguidi

124 Raven Chacon, Iggor Cavalera, and Laima Leyton

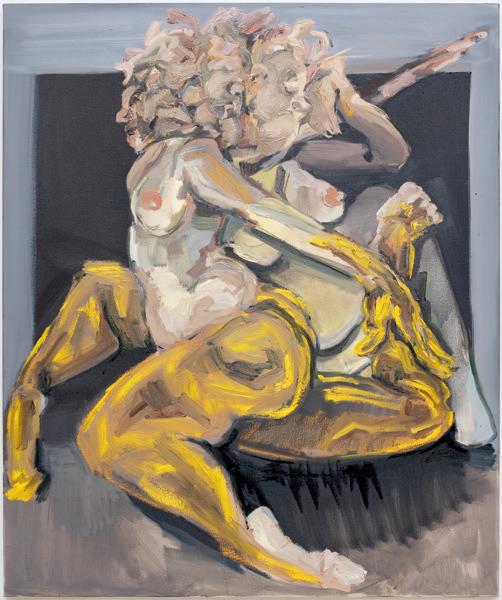

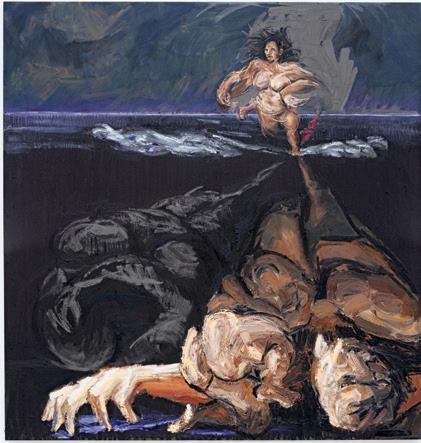

126 Pol Taburet

128 Cynthia Hawkins

130 Márcia Falcão

132 Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide)

134 Alain Padeau

136

Chapter 4

Currents of Nurturing and Plural Cosmologies

138 Laure Prouvost

140 Kader Attia

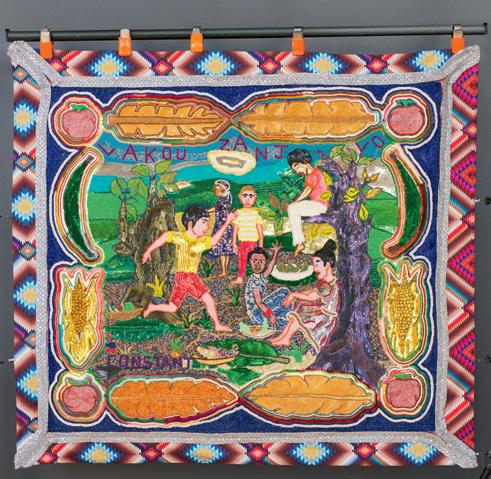

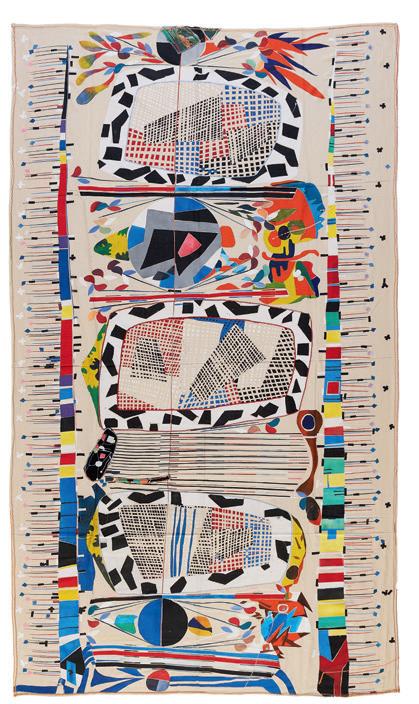

142 Myrlande Constant

144 Joar Nango with the Girjegumpi crew

146 Vilanismo

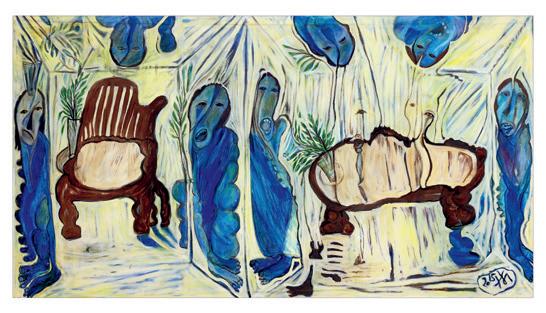

148 Gervane de Paula

150 Sharon Hayes

152 Trương Công Tung

154 Lidia Lisbôa

156 Hao Jingban

158 Meriem Bennani

160 Juliana dos Santos

162 Sadikou Oukpedjo

164 Olivier Marboeuf

166 Camille Turner

168 Simnikiwe Buhlungu

170 Julianknxx

172 Hamedine Kane

174 Sérgio Soarez

176 Leonel Vásquez

178 Helena Uambembe

180 Ernest Cole

182 Metta Pracrutti

184 Kenzi Shiokava

186 Leila Alaoui

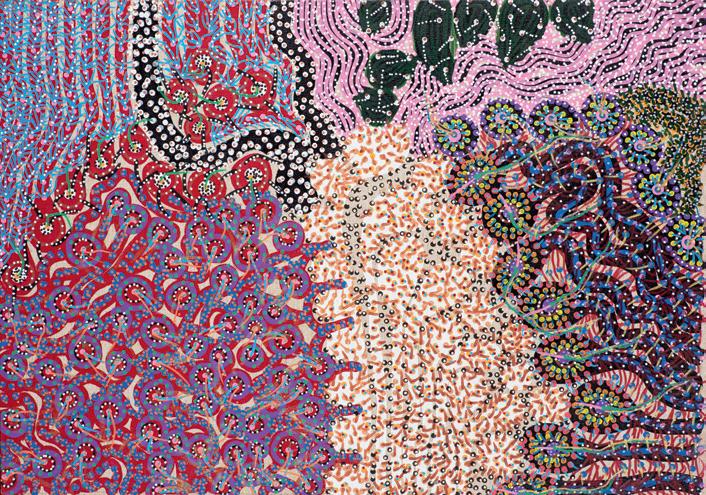

188 Shuvinai Ashoona

190 Myriam Omar Awadi

192 Chapter 5

Cadences of Transformations

194 Antonio Társis

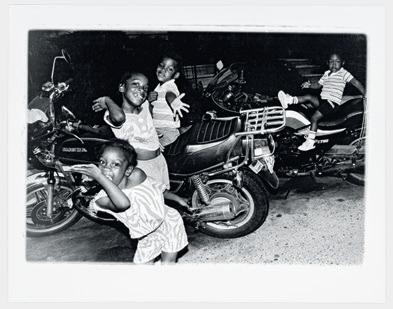

196 Ming Smith

198 Théodore Diouf

200 Berenice Olmedo

202 Hajra Waheed

204 Zózimo Bulbul

206 Nguyễn Trinh Thi

208 Mao Ishikawa

210 Michele Ciacciofera

212 Josèfa Ntjam

214 Lynn Hershman Leeson

216 Richianny Ratovo

218 Cici Wu with Yuan Yuan

220 Laila Hida

222 Korakrit Arunanondchai

224 Maxwell Alexandre

226 Isa Genzken

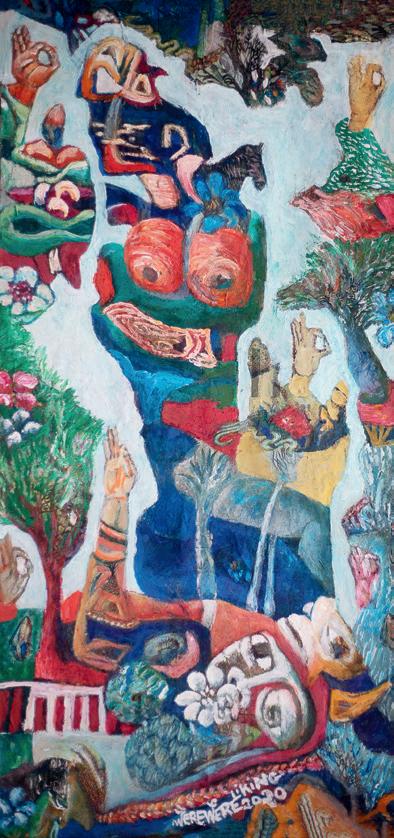

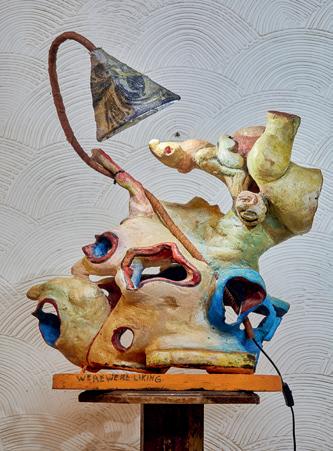

228 Werewere Liking

230 María Magdalena Campos-Pons

232 Chapter 6

The Intractable Beauty of the World

234 Bertina Lopes

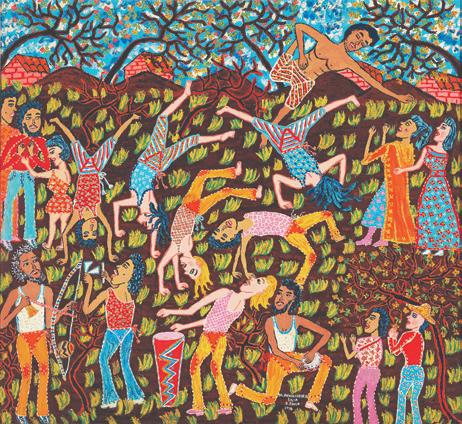

236 Maria Auxiliadora

238 Chaïbia Talal

240 Thania Petersen

242 Hamid Zénati

244 Mohamed Melehi

246 Edival Ramosa

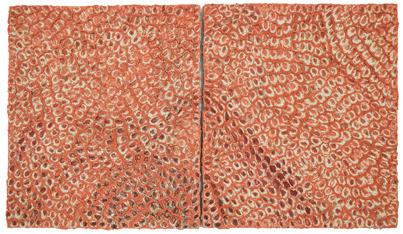

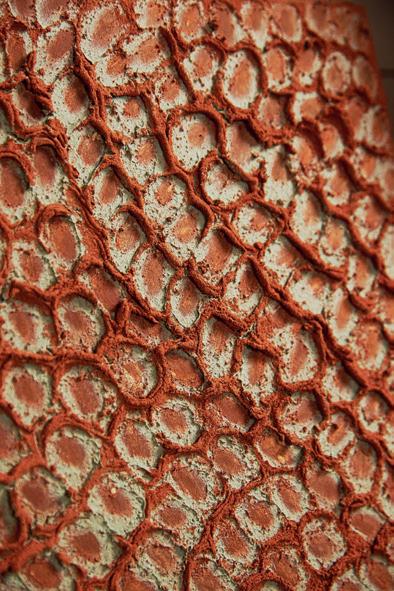

248 Imram Mir

250 Hessie

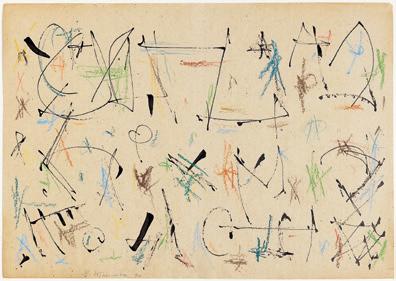

252 Gōzō Yoshimasu

254 Firelei Báez

256 Farid Belkahia

258 Madiha Umar

260 Ernest Mancoba

262 Moisés Patrício

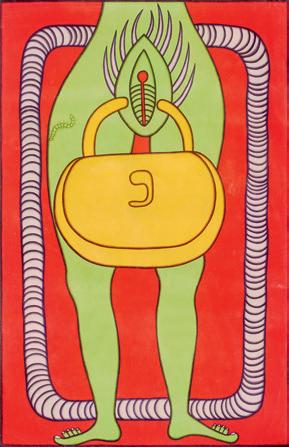

264 I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih (Murni)

266 Behjat Sadr

268 Forugh Farrokhzad

270 Nzante Spee

272 Huguette Caland

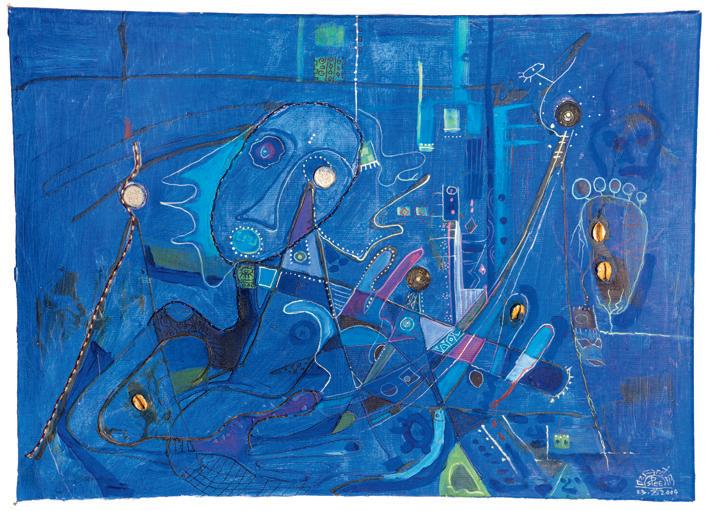

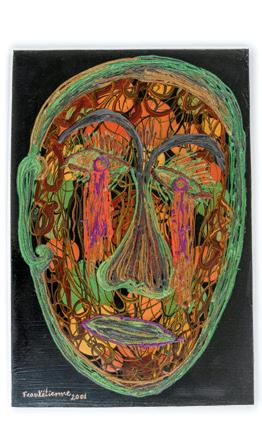

274 Frankétienne

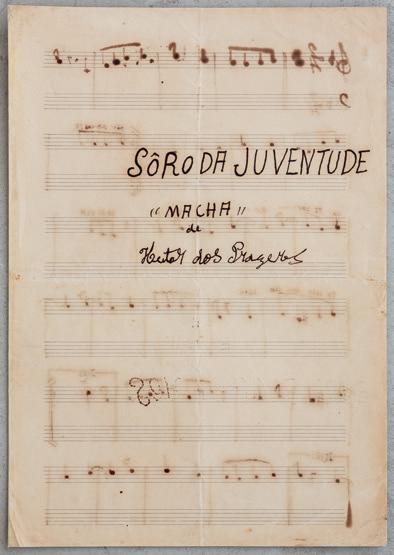

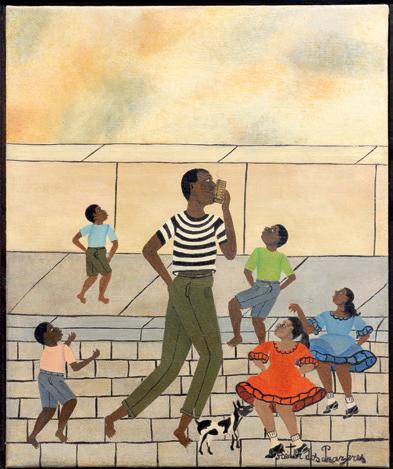

276 Heitor dos Prazeres

278 Adama Delphine Fawundu

280 Aislan Pankararu

282 Raukura Turei

284 Rebeca Carapiá

286 Kamala Ibrahim Ishag

288 Andrew Roberts

290 Alberto Pitta

Marrakech

Guadeloupe

Casa do Povo

Marcelo Evelin

Boxe Autônomo and Dorothée Munyaneza

Alexandre Paulikevitch and MEXA

La Cinémathèque

Not All Travellers Walk Roads

Of Humanity as Practice A Concept

in Three Fragments

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung

February, 2024

Disclaimer: This Bienal is not about identities and their politics, not about diversity nor inclusion, not about migration nor democracy and its failures…

Claimer: It is about humanity as a verb and a practice, about encounter(s) and the negotiations upon the meeting of varying worlds, it is about dismantling asymmetries as a prerequisite for humanity as a practice, it is about joy and beauty and their poeticalities as the gravitational forces that keep our worlds on their axes… for joy and beauty are political. It is about imagining a world in which we place an accent on our humanities.

Fragment I – Da calma e do silêncio

Quando eu morder a palavra, por favor, não me apressem, quero mascar, rasgar entre os dentes, a pele, os ossos, o tutano do verbo, para assim versejar o âmago das coisas.

Quando meu olhar se perder no nada, por favor, não me despertem, quero reter, no adentro da íris, a menor sombra, do ínfimo movimento.

Quando meus pés abrandarem na marcha, por favor, não me forcem. Caminhar para quê?

Deixem-me quedar, deixem-me quieta, na aparente inércia. Nem todo viandante anda estradas, há mundos submersos, que só o silêncio da poesia penetra.

[When I bite the word, please, don’t rush me, I want to chew, tear between my teeth, the skin, the bones, the marrow

of the verb, so I might versify the core of things.

When my gaze gets lost in nothingness, please, don’t wake me, I want to retain, within the depth of the iris, the faintest shadow, of the slightest movement.

When my feet slow their march, please, don’t push me. To walk – what for? Let me stay, let me be still, in apparent inertia. Not all travellers walk roads, there are submerged worlds that only the silence of poetry penetrates.]

Conceição Evaristo, “Da calma e do silêncio” [Of Calm and Silence]1

The concept for the 36th Bienal de São Paulo is a proposal to think, listen to, see, feel, perceive the world from the vantage point of Brazil – its histories, landscapes, philosophies, mythologies, and complexities – for the fiction that is Brazil is a culmination of many worlds and their tangents. That said, the emphasis will be laid on listening as the fundamental ground for practicing humanity. As Jacques Attali wrote in his seminal essay Noise: The Political Economy of Music, “for twenty-five centuries, Western knowledge has tried to look upon the world. It has failed to understand that the world is not for the beholding. It is for hearing. It

1. Conceição Evaristo, “Da calma e do silêncio,” in Poemas da recordação e outros movimentos. Rio de Janeiro: Malê, 2008, p.122.

is not legible, but audible.”2 We seem to have inherited a world crafted by people who have tried to see the world and read the world. One could say that, to conjugate humanity as a verb, one must learn to listen to the world, listen to lands, listen to plants and animals, listen to people, listen to the voices of the waves that caress the shores, to the grumbling of waters, to the winds that carve the sand and the contours of the earth, listen to the murmurs of stones and hills and mountains, listen to the plethora of beings that make up our estuaries. It is safe to say that there is a correlation between the impossibilities of listening and dehumanization, as well as the disenfranchisement of people, the appropriation of lands, and ultimately the destruction of the environment.

In this proposal, the physical and philosophical space of the estuary will be used as a metaphor for spaces of encounter, of negotiations, of exchange, of living, of survival, of nourishment, of struggle, of despair, of repair, of rehabilitation, of needs… spaces in which practices of humanity could acquire new meanings.

From the Santos Estuary or the Bertioga Estuary in São Paulo to the Capibaribe Estuary in Recife and the Patos Lagoon Estuary that extends from Porto Alegre to Rio Grande, the moment when two waterways meet each other, like a river meeting the sea, is a moment of negotiation of physical and chemical asymmetries that creates an extraordinary ecosystem flourishing with crabs, crocodiles, fish, migratory birds, mangroves, oysters, phytoplankton, snails, seagrass, sea turtles, zooplankton, and even humans. The particularity of an estuary is its interdependence. Each being has a role, a niche (for example, the niche of oysters is filtration, with each oyster filtering up to 50 gallons of water per day), in the sustenance of each species, in the ecosystem at large, and in the blossoming biodiversity, especially thanks to the varying salinity levels that arise when sweet water meets salty water. Estuaries are thus important for a vast spectrum of beings as habitat, resource, space for reproduction or transition in our ecosystems, and their existences are crucial for our environments. Estuaries serve as coastal buffers in times of erosions, floodings, or storms, just as they help in filtering freshwater. But due to massive urbanization, dredging, overfishing, pollution, oil

and gas drilling etc. on a planetary scale, the ecosystems of estuaries are losing balance, just as humanity is losing its grip on itself and the world.3 By invoking the plurality of beings and their co-existence and contingencies within that space of the estuary as a metaphor for human relations with themselves and others, the project tangentially alludes to the 27th Bienal de São Paulo in 2006, titled How to Live Together and curated by Lisette Lagnado, as well as the 2nd Bienal, in 1953 (also called “Guernica Bienal”), in terms of the agencies and urgencies at stake.

So when Conceição Evaristo writes in “Da calma e do silêncio” that “Not all travellers/ walk roads/ there are submerged worlds/ that only the silence/ of poetry penetrates,” one can think of estuaries as the epitome of those submerged worlds penetrable by the silence of nature’s poetry and at the same time as the path of coexistence that is woven when the different worlds of sweet and salty water encounter each other, as a path that humankind as travellers could take. Brazil was birthed by the violent encounter of Indigenous people, European colonizers and enslaved Africans. Every civilization stems from an encounter, no matter how violent some might be, and some take more time than others to germinate. For the germination and proper cultivation to happen, one might need patience to bite and tear words to the marrow of verbs, stamina to stare into the distance so that clarity of the smallest movements in the far can be impregnated inside one’s iris, as Evaristo insinuates. So which paths do we take in the practice of humanity as a verb? How do we afford ourselves the privilege of going off track, off the road, embracing errancy, getting lost, finding other worlds?

Fragment II – Une Conscience en fleur pour autrui

Ma joie est de savoir que tu es moi et que moi je suis fortement toi. Tu sais que ton froid dessèche mes os et que mon chaud vivifie tes veines. Ma peur fait trembler tes yeux

3. Emily Caffrey, “The Importance of Estuarine Ecosystems,” Ocean Blue Project. Available at: oceanblueproject.org/whatis-an-estuary. Access: 2025.

et ta faim fait pâlir ma bouche. Sans ta force d’être un feu libre ma conscience serait plus seule que la terre morte d’un désert. Ma vie offre des clefs émerveillées à la perception de ta propre essence. Lorsque tu veilles sur ma liberté tu donnes un ciel et des ailes au mouvement de mon espérance. Mon désir d’être heureux, s’il cessait un instant de compter avec le tien tomberait aussitôt en poussière. Quand tu saignes au couteau mon identité nos consciences vont ensemble à l’abattoir.

[My joy is knowing that you are me, and that I am deeply you. You know your cold dries out my bones, and my warmth brings life to your veins. My fear makes your eyes tremble, and your hunger pales my mouth. Without your power to be a free flame, my awareness would be more alone than the dead earth of a desert. My life offers enchanted keys to the perception of your very essence. When you guard my liberty, you give wings and sky to the motion of my hope. My longing to be happy – should it cease to reckon with your own, even for a moment –would fall at once to dust.

When you cut my identity with a knife, our minds go together to the slaughterhouse.]

René Depestre, “Une Conscience en fleur pour autrui” [A Blossoming Conscience for Others].4

The artist Leo Asemota once asked the question: when you look in the mirror, who do you see? He went ahead to respond himself that there is of course the possibility of seeing only yourself, but when he looks in the mirror, he sees all

4. René Depestre, En état de poésie (Petite sirène). Paris: Les éditeurs français réunis, 1980.

the people who came before him and all in his keeping. This spirit of vertical and horizontal interconnectedness might be another crucial element in the conjugation of humanity. In this era of deep political and social crisis in which we find ourselves in the world, the question of who we see when we look in the mirror becomes even more important. To see a multitude in the mirror is to recognize the existence, the concerns, and eventually care for the well-being. The nation-state is one of those constructs that seem to see only itself when it looks in the mirror. That’s why we fortify our borders with walls, fight wars, expel migrants, destroy the environment etc. Could we actually look into the mirror and see humanity? In all its shapes and colors, with all its long- and shortcomings, with all its shades of grey, and all its imperfections? As it stands, the mirror in which we seem to be stirring is shattered into pieces, and instead of a reflection we seem to be seeing infinite refractions that lead to oblivion. But even a broken mirror can be mended. To engage in that process of mending, however, one must allow oneself to be guided by and consent to René Depestre’s maxims in “Une Conscience en fleur pour autrui”: “My joy is knowing that you are me/ and that I am deeply you.” or “My life offers enchanted keys/ to the perception of your very essence.” Humanity is a practice. Humanity is a verb. It can be conjugated.

Fragment III – The Adamant Beauty of the World

Rising from the abyss is the sound of centuries. The song of Ocean’s valleys.

On the Atlantic Ocean floor sonorous seashells tangle with skulls, bones, and iron balls turned green. These depths hold the cemeteries of slave ships and of the many men who sailed them. Deeds of a greedy Western world, violated borders, flags raised and fallen. […]. But these transported Africans undid the separations of the world. They too opened up the Americas’ vast spaces with violent bloodshed. […]

The remains of these ancestors shipped away to become the silt of the abysses, all those former worlds, were ground down until they truly became a new place. One world made Africa laminary. The Africas impregnated distant worlds. This fact makes it possible to see the Whole-World and to comprehend it – the Tout-Monde given to everyone, valid for everyone, multiple in its totality, based on the sonorous abysses.

Édouard Glissant and Patrick Chamoiseau, “The Adamant Beauty of the World”5

The estuary of Recife is a space of multiple encounters. Not only the meeting of sweet and salt water, but also the first port in the Americas where enslaved people abducted from Africa encountered the so-called new world. Since its founding in 1537 upon Portuguese colonization, Recife has been a remarkable site in which that which has emerged from that abyss, that chasm, despite despicable violences, has been able to manifest its intractable, adamant beauty. A site in which the rumors from and of the depths of that abyss still resonate in all engulfing ripples and manifest themselves as that notion of Tout-Monde.

That “adamant beauty of the world” birthed, in Brazil, some of the most important artistic and cultural movements of the 20th century: the “anthropofagia movement” of the 1920s, that gave form to and informed a Brazilian avant-garde and led both to the “Manifesto Antropófago” and an aesthetics and politics that Oswald de Andrade called “Cannibalist transnationalism” (a philosophy that called for the cannibalization, the ingestion, and the digestion of other cultures as a way of asserting Brazil against European colonial and post-colonial cultural domination, as was so magnificently exposed in the 24th Bienal de São Paulo, curated by Paulo Herkenhoff with Adriano Pedrosa); the Teatro Experimental do Negro [Black Experimental Theater] (TEN), a movement founded by Abdias do Nascimento in 1944 to tackle the dearth of Black presence and dignity in the national performing arts, initiating a movement of Afro-Brazilian playwriting that also engaged politically by bringing the anti-racism struggles to the 1946 Constituent Assembly and 5. Édouard Glissant and Patrick Chamoiseau, “The Adamant Beauty of the World (2009),” in Manifestos. London: Goldsmiths Press, 2022.pp.33-55.

influencing “the proposition of the Afonso Arinos Act, the first legislation geared to curb racism;”6 the Cinema Novo’s “Eztetyka da Fome” [Aesthetics of Hunger] movement, filmically formulated by Glauber Rocha in 1965, understanding cinema as an important tool and weapon for the revolutionary struggle; the Tropicalismo movement of Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa, Tom Zé, and Torquato Neto in the 1960s, advocating with their Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis manifesto for a “field for reflection on social history” through music, film, and other artistic expressions that synchronized African and Brazilian cultures and found a political voice at the height of the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship; or the Manguebit movement of the 1990s in Recife, that stood for a musical revolt against the sociopolitical, economic, and cultural stagnation, for a resistance to the neoliberal agenda that had usurped most of Latin America, that advocated for a cultural memory that embraced all the aforementioned attributes (“given in all, valid for all, multiple in its totality”), and that opted for a way-out of the socioeconomic cul-de-sac through a pidginization of sonic scapes and genres like makossa, Congolese rumba, reggae, coco, forró, maracatu, frevo, as much as rock, hip hop, electronic music, and funk. The Manguebit movement and its manifesto “Caranguejos com cérebro” [Crabs with Brains], written in 1992 by singer Fred Zero Quatro and DJ Renato L, were brought to life by two legendary bands and two albums from 1994 whose titles betray their intentions: Mundo Livre S/A’s Samba esquema noise [Samba Scheme Noise] and Chico Science & Nação Zumbi’s Da lama ao caos [From Mud to Chaos]. This is the crux of Fragment III.

In “Manguebit,” the very first song on Samba esquema noise, Mundo Livre S/A sings of the transistor, of Recife as a circuit and the country as a chip; they sing of Manguebit as a virus that contaminates the eyes, ears, languages, sound waves, and this virus is spread through UHF with the help of needle-antennas inserted in the mangrove in the estuaries. They sing of the land as radio and the destruction of the land and the tributaries. This was an anthem for the strange times then and now.

Chico Science & Nação Zumbi’s first song in Da lama ao caos, titled “Monólogo ao pé do ouvido (vinheta) / Banditismo por uma questão de classe,” is a fierce double

6. “O teatro dentro de mim,” Itaú Cultural, 2016. Available at: ocupacao.icnetworks.org/ocupacao/abdias-nascimento/oteatro-dentro-de-mim/

hymn of defiance. In “Monólogo ao pé do ouvido,” they sing of their movement as a musical evolution to modernize the past, they sing of how fear gives rise to evil and how the collective feels the need to fight against pride, arrogance, glory, and how demons destroy the fierce power of humanity: “Viva Zapata!/ Viva Sandino!/ Viva Zumbi!/ Antônio Conselheiro/ All Black Panthers/ Lampião.” And in “Banditismo por uma questão de classe” they tell a story of bandits, of the talk of solutions and progress, and how this can be done with the killing of innocent people by the forces of law and order. They sing of banditry as survival, as a necessity, as a consequence of class struggles. That these bands refer to a free world and to Zumbi’s nation in their names is no coincidence. That they are from Recife is no coincidence either. After all, it was in Recife that the I Congresso Afro-Brasileiro took place in 1934, including activists like Solano Trindade – who was, by the way, also part of the Frente Negra Pernambucana and the Teatro Experimental do Negro.7 And even more importantly, it was in the states of Pernambuco and Alagoas that the great Francisco Zumbi (1655–1695) of Kongo heritage, who went down in history as Zumbi dos Palmares, claimed his kingdom, fought against the Portuguese colonialists, resisted against the enslavement of Africans, freed his people, and resettled them in the kingdom of Maroons, the Quilombos, that Abdias do Nascimento was later to qualify as some of the first democratic spaces and structures in what is today Brazil. The Quilombos were the foundation on which movements like Manguebit could be built more than 300 years later.

Fragment III is a deliberation on the Manguebit movement and its manifesto “Caranguejos com cérebro,” understood as an exposé of a collective social brain.

In Michael Muthukrishna and Joseph Henrich’s 2016 paper “Innovation in the Collective Brain,” they reflect on something many in non-Western cultures have actually known since time immemorial:

Our societies and social networks act as collective brains. Individuals connected in collective brains, selectively transmitting and learning information, often well outside their conscious awareness,

7. Amurabi Oliveira, “Afro-Brazilian Studies in the 1930s: Intellectual Networks between Brazil and the USA,” Brasiliana: Journal for Brazilian Studies, v.8, n.1-2, 2019.

can produce complex designs without the need for a designer – just as natural selection does in genetic evolution. The processes of cumulative cultural evolution result in technologies and techniques that no single individual could recreate in their lifetime, and do not require its beneficiaries to understand how and why they work. Such cultural adaptations appear functionally well designed to meet local problems, yet they lack a designer.8

The authors elaborate on the origins and machinations of collective brains by discussing their “neurons” and pointing out how individual brains evolve in accordance with the acquisition of culture – the so-called cultural brains (brains that evolved primarily for the acquisition of adaptive knowledge). Which is to say that “our cultural brains evolved in tandem with our collective brains.”

Muthukrishna and Henrich show how “cultural brains are linked into collective brains that generate inventions and diffuse innovations,” as well as examine the ways in which “collective brains can feed-back to make each of their constituent cultural brains ‘smarter’ – or at least cognitively better equipped to deal with local challenges.”9 The threads with which the fabric, the cultural brain, the collective brain of Recife, of the “Caranguejos com cérebro” were woven span from the encounter of the different worlds that were forced to cross paths almost 500 years ago, as well as the different social entities, from the family to the plantation to the samba school, to different social networks. As Muthukrishna and Henrich point out,

the most basic structure of the collective brain is the family. Young cultural learners first gain access to their parents, and possibly a range of alloparents (aunts, grand-fathers, etc.). Families are embedded in larger groups, which may take many forms, from egalitarian hunter-gatherers to villages, clans, and “big man” societies, from chiefdoms to states with different degrees of democracy, free-markets and welfare systems, to large unions.10

8. Michael Muthukrishna and Joseph Henrich, “Innovation in the Collective Brain,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Mar. 19, 2016. Available at: royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2015.0192. Access: 2025.

9. Ibid., p.10.

10. Ibid., p.10.

Next to the people, the geographical and geological bearings of Recife also play an important role in the manifestation of that cultural and collective brain that birthed the Manguebit movement. Recife is situated at the confluence of the Beberibe and Capibaribe rivers, as they proceed in their majesty to empty themselves in that massive body of water, the South Atlantic Ocean, from whose belly, from whose vault, the voices still sing. Topography and climate also contribute in the making of knowledge. With its tropical forest, high rainfall, its monsoon climate, its estuaries, high relative humidity, Recife has been called the daughter of the mangrove, with its Parque dos Manguezais that too lends its name to Manguebit. But this natural, ecological richness of Recife which could be a dream for some became a nightmare for the people of Recife. In Alice de Souza’s article “Life Reborn in the Mud,”11 she writes about Ilha de Deus [God’s Island], an island of Recife that had been generally neglected to its decrepitude in the 1970s and 1980s – there was no water, no electricity, no attention from the government. In the middle of these dire sociopolitical and economic conditions, the island was called Ilha sem Deus [Godless Island]. As if the neglect of Ilha de Deus wasn’t enough, in 1983, two nearby factories provoked an environmental disaster by dumping waste from soap production into the water, thereby intoxicating fish and sea plants, which were the main means of subsistence in the area. This lead to starvation and mass exodus of the islanders in search of greener pastures. At the same time, criminality skyrocketed on the island, which had become a hiding place for gangs. This was not restricted to Ilha de Deus, as the ruthless construction in Recife, the intoxication of the environment by industries, the dumping of waste in the rivers, and the perishing of lives in the city’s mangroves (that had become oversaturated with plastic and other wastes) led to an auto-suffocation. If the rivers and estuaries of Recife were the veins and arteries of the place, then the city was suffering from a terrible thrombosis. It was against this backdrop that the Manguebit movement emerged as a cultural revolution in the 1990s, basically to say “No more,” accompanied by several environmental groups that planned to replant mangrove seedlings, folding sleeves and going knee-deep into the mud to clear the estu-

11. Alice de Souza, “Life Reborn in the Mud,” Believe Earth, Nov. 17, 2017. Available at: believe.earth/en/life-reborn-in-themud/. Access: 2025.

aries from plastic.12 This new movement came with a new sound: Manguebit.

Fragment III of this Bienal will pay homage to the Manguebit movement, as a descendant of all the great movements that ever came out of Brazil. As Melcion Mateu writes in his essay “Nação Zumbi: Two Decades of ‘Crabs with Brains’ (and Still Hungry)”:

The term “manguebit” is itself a hybrid, portmanteau word containing a reference to local landscape (“mangue” as said, “mangrove swamp,” “marshland”) and global technology (“bit” or binary digit, as in computer science): a movement rooted in its landscape but connected to the global technology […]. A parabolic antenna put in the mud became the concept image to describe a movement that aspired to connect the local culture to the global scene.13

Which is to say that the Manguebit is a conceptual paradigm that brings together the notions of maternity, fertility, diversity and productivity with the notion of a technology, digital media or computation that can facilitate syncretism, that can bridge the gap not only across the Atlantic, but between those that survived on land and those still locked up in that abyss. Technology in this context serves a double purpose of connecting but also subverting. Manguebit should also be understood as the possibility of creating technologies, sciences, and arts that not only reflect the quotidian, but are also fundamental for the subversions of the terrors of normativity. The technologies and sciences that were conceived to disprivilege the masses are actually misappropriated and perverted from their original purposes, in what we might call weapons of mass subversion.

The Manguebit manifesto “Caranguejos com cérebro” directly relates to the people of Recife, who are colloquially referred to as crabs living in the mangrove. Crabs, like some other lobsters and shrimps, are known to be masters of navigation of their territories and even territories unknown, since they have a sophisticated memory. They have been found to have the cognitive capacity for complex learning

12. Idem.

13. Melcion Mateu, “Nação Zumbi: Two Decades of ‘Crabs with Brains’ (and Still Hungry),” Crítica Latinoamericana, Dec. 5, 2012.

despite their rudimentary brains. In the article “Clever Crustaceans,” Erica Westly states that crabs “can remember the location of a seagull attack and learn to avoid that area. In mammals, this kind of behavior requires multiple brain regions, but a study published in the June issue of the Journal of Neuroscience suggests that the C. granulatus crab can manage with just a few neurons.”14 The experiments made by neuroscientists at the Universidad de Buenos Aires to test the memory skills of crabs showed that they could retain information for more than 24 hours, which is the clinical benchmark for long-term memory in most animals, including humans. And even more: they showed the ability to apply their acquired knowledge for their well-being and survivor. The researchers attributed this behavior to the crabs’ lobula giant neurons, that might have the possibility of storing information about different stimuli. It is known that crabs learn from their mistakes, that they are ambidextrous, that they have a sense of compassion that leads them to protect their territory, and that crab mothers are very caring, and are said to place snail shells around their young ones to increase their calcium intake. This is an invitation for artists, scholars, and people from varying walks of life to reflect on the social and cultural brain of the collective, which embodies the ambidexterity, intelligence, and prudence of the crabs as a way of being in the world, as a way of being better humans. This is also an invitation for them to deliberate on spaces like estuaries and mangroves, spaces that are evidence of solidarity, a coexistence of a variety of beings, plants, animals, and mycelia that mostly assist and subsist each other, if left alone by the human. So, if such creatures with what we, humans, might call “primitive brains” could exercise such proficient memories and such compassion, why can’t humans? Or can they? The relationship between crabs and humans that is central to the Manguebit movement had already been described in Josué de Castro’s seminal novel Of Men and Crabs, published in 1967. By then, Josué de Castro had earned fame for his path-breaking ecological work on the politics of hunger titled The Geography of Hunger, published in 1946. Being a physician in Recife, De Castro had done studies with workers’ and declared that their “basal

14. Erica Westly, “Clever Crustaceans,” Scientific American Mind, v.22, n.5, Nov. 2011, p.14.

disease” was hunger, that manifested itself clinically as anemia, protein-calorie malnutrition, and more. He linked the socio-economic realities of the people of Recife to their biological manifestation of hunger. In his later work Of Men and Crabs, written while in exile in Paris, he tells a fictional tale of poverty related to his childhood, narrating the tragic life of the young João Paulo. The author interweaves the story of the pathetic condition of all the people around the boy with the story of Father Aristides, whose craving for the guaiamum crabs is insatiable. In that space of exile, and hopelessness, De Castro gifted the world a book that paints the reality of “the wretched of the earth.” It is no surprise that the main character João Paulo disappears during a disastrous flood that literally erases the whole settlement. But as De Castro writes, what we take with us is, “humans fashioned of crab meat, thinking and feeling like crabs; amphibians, at home on land and in water, half-man, half-animal; fed, in their infancy, on that miry milk, crab broth.”15

These relationalities of beings across land and waters, those in the swamps, so playfully and critically put forth by Mundo Livre S/A and Chico Science & Nação Zumbi, these relationalities between different genres, between gods and humans and other existences put forth by Mário de Andrade, these relationalities proposed by De Castro, these relationalities that mediate the rumors from several centuries ago to the rumors of today, that negotiate between the voices in the vault and the voices of those who are still surviving… all these relations speak to an exhaustive and resilient brain: the Mangue brain. The first Mangue manifesto, “Caranguejos com cérebro,” was structured as a trilogy: “Mangue – The Concept,” “Manguetown –The City,” “Mangue – The Scene”… Now we can imagine “Mangue – The Exhibition.” An exhibition that negates the Darwinian notion of survival of the fittest, but advocates for co-existence, interdependence, love, joy, beauty as the basis for the intractable, adamant beauty of the world.

Structure

Exhibition/Manifestation: the exhibition brings together artists from the Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania, working across disciplines and experimenting on content and container to have their works manifest in the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion. A special emphasis will be laid on sonic practices.

Invocations/Tributaries: staying true to the metaphor of the estuary, the tributary as a concept is evoked here to connote the spaces through which one waterbody flows into another. In this project, Tributaries are cultural programs that have been developed with institutions in São Paulo and around the world that will host discursive and performative formats (lectures, workshops, poetry, music, installations, performances). The programs that take place in the run-up to the Bienal exhibition are called Invocations, and those that take place in parallel are called Tributaries. The deliberations from the Invocations will inform the manifestations at the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion and Ibirapuera Park. They are a tangential reference to the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo in 2016, curated by Jochen Volz, wherein Study Days were organized in four cities around the world.

Public Program: the public program is furnished with a series of performances, sonic gestures, storytelling sessions, and lectures. At the core of the public program will be the “Radio du conte vivant,” reminiscent of the Mobile Radio project of the 30th Bienal de São Paulo in 2012, curated by Luis Pérez-Oramas and titled The Imminence of Poetics. But “Radio du conte vivant” takes its cue from the seminal lecture of Patrick Chamoiseau16 with the title “Circonfession esthetique – le conteur, la nuit et le panier” [Aesthetic Circonfession – The Storyteller, the Night, and the Basket], wherein the author discusses the importance of “oraliture” as a core narrative strategy in Caribbean cultures, employing “tales, word games, rhymes, riddles, songs, a popular philosophy carried by proverbs […].” He adds that “transmission is therefore essentially done without many words, through proximity, observation, imitation, sensation, humility, and that dose of unconsciousness that is necessary to aspire to become a master of the word.”

16. Patrick Chamoiseau, “Discours inaugural de la Chaire d’écrivain en résidence,” Sciences Po, Paris, Jan. 27, 2020.

Educational program: so storytelling as a practice of conjugating humanity will be the modus operandi for the public and educational programs, and that goes in line with what Chinua Achebe said when asked in a 1998 interview “what is the importance of stories.” He responded:

Well, it is story(telling) that makes us human. And that’s why we insist. Whenever we are in doubt about who we are, we go to stories because this is one thing that we have done in the human race. There is no group that doesn’t do it. It seems to be central to the very nature, to the very fact of our humanity to tell who we are. And to let that story keep us in mind of this. Because there will be days when we are not quite sure whether we are human or even more commonly whether other people are human. It is in the story that we get this continuity of this affirmation that you are human and that your humanity is contingent on the humanity of your neighbor.17

Choir: an important part of both public and educational programs is the creation of “The Tout Moun Choir” for the 36th Bienal de São Paulo, as well as collaborations with local choirs. The choir owes its name to the maxim of the Haitian revolution, “Tout Moun Se Moun,” that pronounces every human as equal, that declares that every human is a human and therefore has the right to be treated as such with the required respect and dignity. Choirs are the epitome of collective interdependence.

Adoption of artworks: citizens are invited to adopt artworks in the cause of the exhibition. By doing so, they have access to the artists and can also serve as mediators between the artworks and the audiences.

17. “Nigerian Author Chinua Achebe in 1998,” New York State Writers Institute, Oct. 1998. Available at: www.youtube.com/ watch?v=vKDupjm2fU8. Access: 2025.

Chapter 1 Frequencies of Landings and Belongings

The exhibition opens with a cluster of works that connects the exhibition to sounds, sights, textures, and energies of Ibirapuera Park. The works in this chapter thematize the generativeness and agency of soil and land, the grounding of soil, and humanity’s connection to and dependence on soil. The soil from which we are made and the soil to which we must eventually go back into. In an age of extractivism, to reflect on soil and land at large becomes an urgency, as humanity has played a significant part in the destruction of lands and the environment. Imagine embarking on a walk through these sound-, smell-, and touchscapes, sight- and landscapes with Mateus Aleluia’s “O serpentear da natureza” [The Meander of Nature] (from his Fogueira doce [Sweet Bonfire] album), or Büşra Kayikçi’s “Into the Woods” (from her Places album). To conjugate humanity means healing the land, repairing our relationship to it, and being with the land and nature at large. While conflicts ravage across the globe related to the question of ownership of land(s), we must acknowledge that we do not own the land but the land owns us.

This shift implies the human is but a small part of the pluriverse that must exist in relation with other beings rather than in competition. The works in this chapter also speak to the notions of longing for physical, social, cultural, and psychological bearings

that define our belongings. Belonging to places, communities, social structures beyond the nation-state. Belonging to each other and to the world. Listening as a practice is a foregrounding element of this chapter, as to conjugate humanity we must not only listen carefully to each other but to all beings in the world. Belonging to one another and to the world requires a profound engagement that transcends mere words. In this chapter, listening emerges as a visceral practice that demands our full embodiment. To truly conjugate our shared humanity, we must attune ourselves not only to the voices of those around us but also to the silent rhythms of all beings with whom we coexist. A kind of listening rooted in our bodies; it requires us to be present, to feel the energy in a room, and to acknowledge the unspoken dialogues that exist in our shared spaces. Listening as a prerequisite for any acts of liberation and emancipation, listening as a foundation of quilombismo, listening as the catalyst of being in relation.

The exhibition here is a space in active dialogue with the Park and all the vibrations that emanate from it.

Precious Okoyomon

What might moments of calm and quiet look like amidst the bubbling and buzzing effervescence gathered around an event like the Bienal de São Paulo? What spaces of collective rest could be envisioned, and how could they shape the audience’s experience as their bodies swarm and sway across the alleys full of artworks?

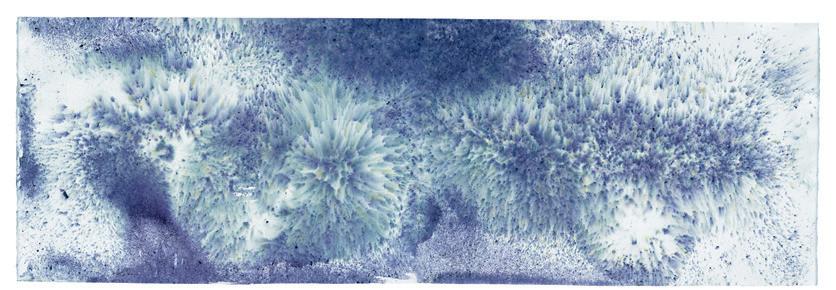

As a response to the curatorial statement of this year’s edition of the Bienal, Nigerian-American artist Precious Okoyomon proposes an installation titled Sun of Consciousness. God Blow Thru Me – Love Break Me (2025), a piece that spatially reappropriates and reconfigures part of the Cicillo Matarazzo Pavilion. Known for their bold and imposing installations, Okoyomon’s practice lies at the intersection between poetry, food, and installation, merging sound with living and decaying materials such as rocks, plants, trees, and moss, among others. Effortlessly moving within several disciplines, Okoyomon wears several hats, sometimes acting as a visual artist, poet, chef, composer, and film director among others, with poetry and words acting as the red thread. As the artist often expressed in several interviews, most of the poems were written before they started making objects, and these poems have formed the seeds of their artworks.

Highlighting the vulnerability of our human condition and the complex, intricate, and inextricable relationship we share with other-than-human entities, Okoyomon, in this commissioned piece, applies a metaphorical lens to the cerrado desert and its seemingly chaotic and fragile ecosystem, drawing parallels between one of Brazil’s largest biomes and humanity. Chaos here, as often ascribed to nature or humanity, does not refer to some sort of cacophony or disorder. Rather, it refers to the symbiotic and unpredictable relationships resulting from the multiple and interdependent encounters between the different animate and inanimate beings, which likewise form the backbone of the cerrado and our societies. What Édouard Glissant refers to as the Chaos-Monde1 in his reappraisal of cultural choc and encounters.

Echoing the famously known Pidgin English adage “Bodi no be fayawood,” the piece Sun of Consciousness. God Blow Thru Me – Love Break Me also emphasizes the need to embrace rest and refuge as a productive site, particularly in a world constantly evolving and paced by the capitalistic enterprise.

Billy Fowo

1. Interview with Yan Ciret published in Chroniques de la scène monde. Paris: Éditions La Passe du Vent, 2000.

ONE EITHER LOVES ONESELF OR KNOWS ONESELF, 2025. View of the solo exhibition the world requires something of me and I’m looking for a place to lie down at Kunsthaus Bregenz. Photo: Markus Tretter. © Precious Okoyomon, Kunsthaus Bregenz.

See The

Gê Viana

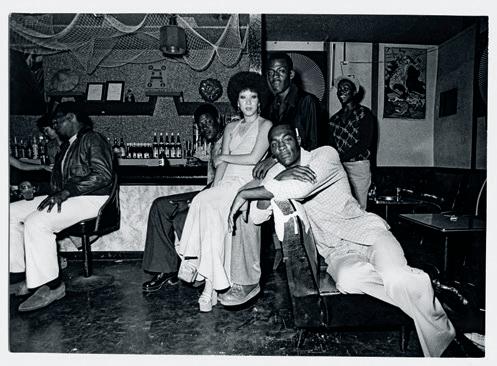

At the crossroads of faith, sound, and belonging, Gê Viana investigates the vibrations that sustain Black and Indigenous communities, in which music is not just a cultural expression but a historical inscription charged with insubordination. Her research starts from experience and unfolds like a living narrative, connecting bodies, territories, and affections by interweaving real and fictional memories. In this way, the artist dismantles scenes crystallized in official historiography and expands readings on cultural heritage in Brazil. Articulating a visual and sound archaeology that reconstructs fragments of records – within the hegemonic discourse or in the popular imagination – she creates works that become symbols of resistance. By challenging colonial narratives, Viana rescues the dignity of marginalized populations and creates an affectionate practice that moves between the analogue and the digital. Her works displace the marks of racial violence and establish meanings of imaginative liberation, something that Édouard Glissant called “overcoming colonial trauma.” The radiolas of Maranhão, the beats of reggae, and the drums of the terreiros emerge as sensitive layers in her works, resonating with memories that defy historical silencing. The Maranhão reggae tradition, captured by the artist’s senses, reveals itself as a genre that, although marginalized, has built its own territory, rooted in the Black diasporas and the struggle for permanence. Powerful sound systems and ancestral rhythms structure her work, in which noises, echoes, and pulsations act as insurgent forces that intone community celebrations, forming a fabric that transcends the aesthetic experience: they are traces of a collective trajectory that defies oblivion.

Beyond the harmonic impact, her practice carries a non-negotiable political commitment. Her images evoke the past of diasporas but without fixing these bodies in pain – on the contrary, she inserts them into poetic universes of fabrication, resistance, and futurity. Her creations operate as portals where time blurs and the echoes of other stories can still be heard.

The fusion between archive and speculative creation reveals a search for interrupted continuities, for buried narratives that insist on emerging. With each juxtaposition of images, with each displacement of an old photograph onto a new medium, the artist builds a cartography in which all times vibrate together and the future is not just a wait, but a call to invention. Whether reconfiguring images or amplifying centuries-old frequencies, her poetics create a space where continuity and rupture coexist. Her works not only document but open up ways for visual sonorities to remain as pulsating matter, a promise of the future and an invitation to listen to ancient whispers that have never stopped vibrating: melanin, love, faith, struggle, invention, and community.

Nathalia Grilo

Translated from Portuguese by Philip Somervell

Nádia Taquary

In her sculptures, Nádia Taquary evokes feminine power through bronze casting. By transmuting the metal and shaping it, the artist imbues it with a technical refinement reminiscent of sumptuous ancient African production. Her work re-signifies African traditions, bringing to light technologies, narratives, and aesthetics that have historically been ignored or appropriated by the West.

Based on her studies of Afro-Brazilian jewelry, Taquary delves into ancestral, religious, and Afro-feminine history. Jewelleries such as balangandans, which adorned the waists of Black women during the enslaved-owning period, are symbols of strength and power. By expanding them into three-dimensional form, the artist deconstructs narratives imposed by colonialism and the history of art itself.

Mulher Pássaro [Bird Woman], 2021. Bronze. 185 × 55 × 75 cm. Menina Pássaro (Areyegbó) [Bird Girl (Areyegbó)], 2023. Bronze. 155 × 55 × 45 cm. Photo: Thales Leite.

In the installation Ìrókó: A árvore cósmica [Ìrókó: The Cosmic Tree] (2025), created for the 36th Bienal de São Paulo, the artist deepens her relationship with materials and with bronze forging. Using fiberglass, bronze sculptures representing the Ìyámis (female ancestral entities), and strings of beads in the colors of the deity Ìrókó, the work evokes ancestral knowledge through the cycle of life. Ìrókó, the orisha lord of time and ancestrality, came to be worshipped in Brazil by means of the gameleira – a tree found in the yards (or terreiros) of religions of African origin, signaled by a white flag. Ìrókó is the antidote to evil, the calm after the storm, and the inevitability of life. It was the first tree to be planted and, according to tradition, it was through it that the orishas descended to Earth, and upon which the Ìyámis sorceresses landed.

Ana Paula Lopes

Translated from Portuguese by Philip Somervell

Obaluaê (Dinka Orixás series), 2018. Glass beads, cowries, copper, gourds, raffia. 160 × 40 × 12 cm. Photo: Sérgio Benutti.

Madame Zo

Untitled (Style Déménagement) [Moving Style], 2013. Banana fiber, spool, grass. 216 × 118 × 1 cm. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur, ADAGP, Paris, 2023. Courtesy of Fondation H, Antananarivo.

Widely known by her artist name Madame Zo, Zoarinivo Razakaratrimo (1956–2020) was a major figure of the Malagasy art scene, renowned for her works that constantly blurred the boundaries between arts and craftsmanship. Trained in weaving and textile dyeing, Madame Zo drew inspiration from traditional Malagasy techniques and patterns, producing unique and distinctive abstract pieces, politically charged due to their capacity to question environmental and sociopolitical issues in Madagascar. With a conscious endeavor to rethink the limits of conventional weaving practices, Madame Zo integrated atypical and unexpected objects into her weaves, complementing the traditionally used materials such as cotton and silk. Often sourced from the quotidian, these resources, beyond their aesthetic or mere functionality, provided information on the artist’s creative process and deep engagement with her surroundings and the people that form it.

In the framework of 36th Bienal de São Paulo, a selection of her works provides in-depth insight into Madame Zo’s practice, which spanned nearly five decades. Woven with copper wires, herbs, wood, plastic, food bits, and magnetic bands, just to name a few, Madame Zo’s choice and usage of each material draws our attention to some of the particular urgencies she aimed to address. Copper, which predominantly appears in her pieces, could be read as a reference

L’Éclair [The Lightning], 2015. Thread, cut newspaper, magnetic tape. 229 × 192 × 1 cm. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur, ADAGP, Paris, 2023. Courtesy of Fondation H, Antananarivo.

2019. Wood shavings, fabric, 16mm film, cotton thread. 111 × 77 cm.

Nicolas Brasseur, ADAGP, Paris, 2023.

of Fondation H, Antananarivo.

to communication technologies, but also to healing due to its capacity to conduct energies – what Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung termed the “techno-spiritual” aspects of copper in a text written on Madame Zo’s works.1 Furthermore, materials such as herbs or paper, particularly in the form of newspaper clippings, refer to her engagement with alternative therapeutic practices and information dissemination, respectively.

In what could be perceived as a retrospective, the constellation of works presented in the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion alludes first and foremost to a retrospection –a re-contextualization of each piece, particularly as they pertain to this year’s Bienal thematic and invite us to conjugate humanity in its manifold manifestations.

Billy Fowo

1. Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, “Spacemaking and Shapeshifting in Mme Zo’s Weaving Practice”, in Madame Zo. Bientôt je vous tisse tous. Paris: Fondation H, 2024.

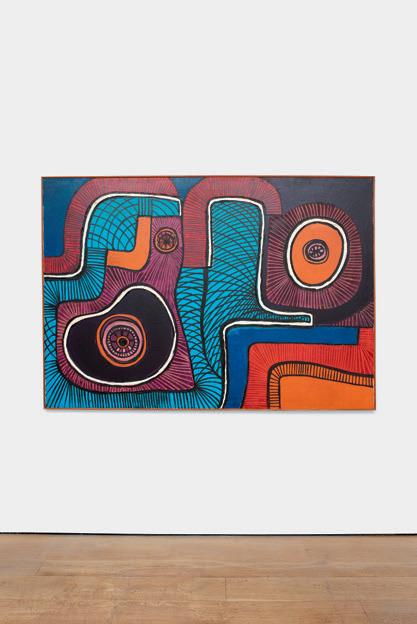

Frank Bowling

Frank Bowling’s practice has drawn from color field painting and abstract expressionism. His prioritization of process and the properties of paint are central to his works. Combining abstraction, landscape, and cartography, Frank Bowling’s oeuvre is characterized by an experimental and spontaneous relationship with shape, color, and structure. Known for his continually evolving practice, Bowling began his career with more figurative painting before moving to pure abstraction in the 1970s and rooting his work in a convergence of techniques and styles evident in his work to this day.

“Blackness is no more expressed, in the literal sense, by painting a black face than by a black line,”1 Frank Bowling wrote in 1970. There is no one symbol that represents the experience of Blackness more than another symbol. Abstraction is just as effective as figuration in Black meaning-making, perhaps in that neither is effective at all. The symbols in

are a collection of

iconographic signifiers that the artist arranges in thematic series. Leaning on abstraction, Bowling creates compositional arrangements that remain opaque vestiges of land masses and shapes.

Born in South America, in Guyana, Bowling has spent his six-decade-plus career living between London and New York. The artist’s choice to represent the shapes of continents and islands reflects a stripping away of assumed relationships between color and identity, nation and personhood. Shapes that once seemed representative, such as continents and islands, are abstracted to reveal that even the illusion of the shape has a great bearing on the message extracted from the painting. For Bowling, “the subject of painting is paint,” the artist’s son, Ben Bowling, said in 2024.2 The illusion of meaning has its foundation in the human eye’s perception of formal elements. Committed to process, Bowling’s compositions also question the politics of cartography, a motif ubiquitous across his work. In the Map Paintings (1967-1971) series, the South American continent begins as a formal outline that ascribes to the cartographic borders, then becomes a remnant of a shape beyond cartography. The motif is abstracted as the continent becomes an amalgamation of rectangles, which later become vertical lines that stretch from the top of a painting down to the bottom. In abstractions that seem to depict horizons or landscapes, we find the motifs of continents and longitudinal lines seeming to appear again. The illusion of shape, horizon, atmosphere, border, and shore, however, is merely a trick of the eye.

Margarita Lila Rosa

1. Frank Bowling, “Silence: People Die Crying When They Should Love.” Arts Magazine, v.45, n.1, Sep.-Oct. 1970, p.32.

2. “‘The Subject of Painting Is Paint’: On Frank Bowling,” The Nation, Jan. 10, 2024.

This participation is supported by: British Council, within the UK/Brazil Season of Culture 2025-2026

Dancing, 2023. Acrylic and acrylic gel on canvas with marouflage 413,2 × 197,5 × 4,3 cm Photo: Anna Arca. © The Frank Bowling Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Courtesy of The Frank Bowling Foundation.

Sertão Negro

Sertão Negro is both an aesthetic and political proposition, an initiative that challenges boundaries – between art and life, community and autonomy, collective organization, belonging, and displacement. Founded by Ceiça Ferreira and Dalton Paula, the project is a space for creation that respects individuality within a joint action, where art is not confined to the production of objects but unfolds into a way of inhabiting the world.

Based in Goiânia, Goiás, Sertão Negro hosts a studio, residencies for national and international artists, a film club, a capoeira group, an active kitchen, gardens, and nurseries. These are not mere metaphors of resistance but concrete tools in the search for sovereignty and self-determination, evoking quilombola and Indigenous resistance practices – both past and present. There, cultivation and creation intertwine, making the notions of care and continuity more than words: what is planted in the Sertão is a way of doing and thinking that transcends beyond its walls.

Formed by around thirty people – including resident artists, researchers, cooks, educators, curators, and members of Sertão Verde, a group focused on agroecology and food sovereignty – the collective promotes debates and exchanges of experiences in an alternative model of exchange, where processes are as important as the artistic production itself. The foundation of the project is rooted in quilombos and terreiros – spaces of resistance and knowledge – as well as in ancestral construction techniques and the wisdom of the land.

At the 36th Bienal de São Paulo, Sertão Negro manifests as an active and expanded space. In collaboration with the Fundação Bienal’s education team, the group proposed a public program with workshops, open studios, a film club, and activities in Ibirapuera Park. Inside the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, the work is organized around two stone circles, inspired by the Sertão Negro space where collective decisions are made. The stones, loaned by the Guarani of Jaraguá, São Paulo, represent a gesture of respect for the land’s time. Two walls structure the space: one presents the history of the project through photos and documents; the other projects the ongoing activities and processes. There is also a mud counter, built with ancestral knowledge, where botanical workshops and cooking practices take place. These actions are tools for imagining and constructing alternative ways of being in the world, within a collective experimentation space where art unfolds as a fluid process, in dialogue with multiple temporalities and territories.

Amanda Carneiro

Translated from Portuguese by Sergio Maciel

Sallisa Rosa

Sallisa Rosa works with memory, formed in clay works, drawings, installations, photographs, and other media. There are incarnate mysteries that we experience in contact with the objects and spaces she produces. Our sensitive presence encounters others that have been there longer, and history is made in an overdue dialogue. Collecting is a central procedure of her work. For her objects or installations, the artist collects clay from different territories. I wonder if the earth has a memory of its own – of its uses and, consequently, of the abuses it has suffered. So I take clay as an ancestral memory, as the sediment of history. Memory is also an attribute of plants, animals, rivers, and other beings. They all record their trajectory, the absorption of time, and transformations of place. Branches, for example, reveal the ways in which a tree responds to the scarcity or abundance of water, changes in the soil, air, and interactions with other bodies. In dealing with this material, Sallisa Rosa is working with historical material. When she collects elements for her works, perhaps she is collecting documents from a history that has not yet been told and which is elaborated by the gestures of building. I wonder if it’s possible to inherit gestures when handling a material loaded with time, like a memory of touches. The gesture is the expression of a body that, at every moment, deals with the set of memories inscribed in it. With these gestures, the artist erects objects that grow like hollow bodies or beings made up of sutured fragments. She erects walls, invents new places, new territories. With the gestures she inherits, she takes part in the use of the land.

Her practice is also anchored in collectivity when she brings together a group of people to work, be, eat, plant, think, and feel together. In these moments, the artwork is born from the sharing of knowledge about construction, materials, modeling, ceramic firing, among others. The ways of making narrate these encounters and condense the specific knowledge of a group – their way of dealing with life. With the memory of matter, organized by the gestures of those who work, Rosa’s work constructs a narrative in which time takes the form of her labyrinth: there are several entrances and exits, and the paths are spiral. Outside of linearity, it is possible to return to where you came from to experience smells, sounds, and temperatures. In the labyrinth, the body moves forward by intuition, risking getting lost just to see what’s on the other side of a wall. There are always other sides – and each path leads to another.

Caio Bonifácio

Translated from Portuguese by Philip Somervell

Carla Gueye

In her multidisciplinary practices, Carla Gueye investigates notions of intimacy and transculturality, exploring how these themes manifest and reverberate in the family context. Her works propose reflections on the complexities of identity, affective relationships, and the experiences that emerge from encounters and tensions between different cultures. By approaching otherness, her work also reveals emotional, artistic, and socio-ecological dimensions. By using materials such as lime and clay, the artist not only explores their physical properties but also constructs narratives that reconfigure cultural knowledge and imagery. Themes such as memory, the female figure, and processes rooted in the excavation and re-appropriation of partially confiscated narratives run through her work, which simultaneously becomes a way of re-inscribing and understanding her own history. The manual labor that permeates

her poetics establishes an intimate, almost domestic relationship with the materials – metaphorically evoking the idea of construction in both its social and humanistic dimensions. In this way, her works become sensitive spaces for dialogue and reflection on culture, identity, and the complex webs that shape human experience.

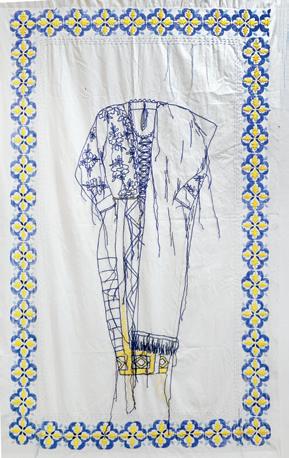

Cabinet of Invisible Desires (2025) is an interdisciplinary installation that explores the sensory, symbolic, and cultural dimensions of intimacy through a contemporary reinterpretation of female seduction rituals, especially those associated with dial diali, the Wolof art of seduction. The project uses a hybrid language that combines sculpture, fabric, video, and olfactory composition to propose an aesthetic of desire rooted in invisible everyday gestures, vernacular knowledge, and the sensitive archives of the body.

Ana Paula Lopes

Translated from Portuguese by Philip Somervell

This participation is supported by: Institut français, within its IF Incontournable program

Malika Agueznay