We respectfully acknowledge the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation, who are the Traditional Owners of the land on which Swinburne’s Australian campuses are located in Melbourne’s east and outer-east, and pay our respect to their Elders past, present and emerging. We are honoured to recognise our connection to Wurundjeri Country, history, culture and spirituality through these locations, and strive to ensure that we operate in a manner that respects and honours the Elders and Ancestors of these lands. We also respectfully acknowledge Swinburne’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff, students, alumni, partners and visitors. We also acknowledge and respect the Traditional Owners of lands across Australia, their Elders, Ancestors, cultures and heritage, and recognise the continuing sovereignties of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nations

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow. Some images, text, terms and annotations used in content and assessment will reflect the period in which the item was produced and may be considered inappropriate today in some circumstances.

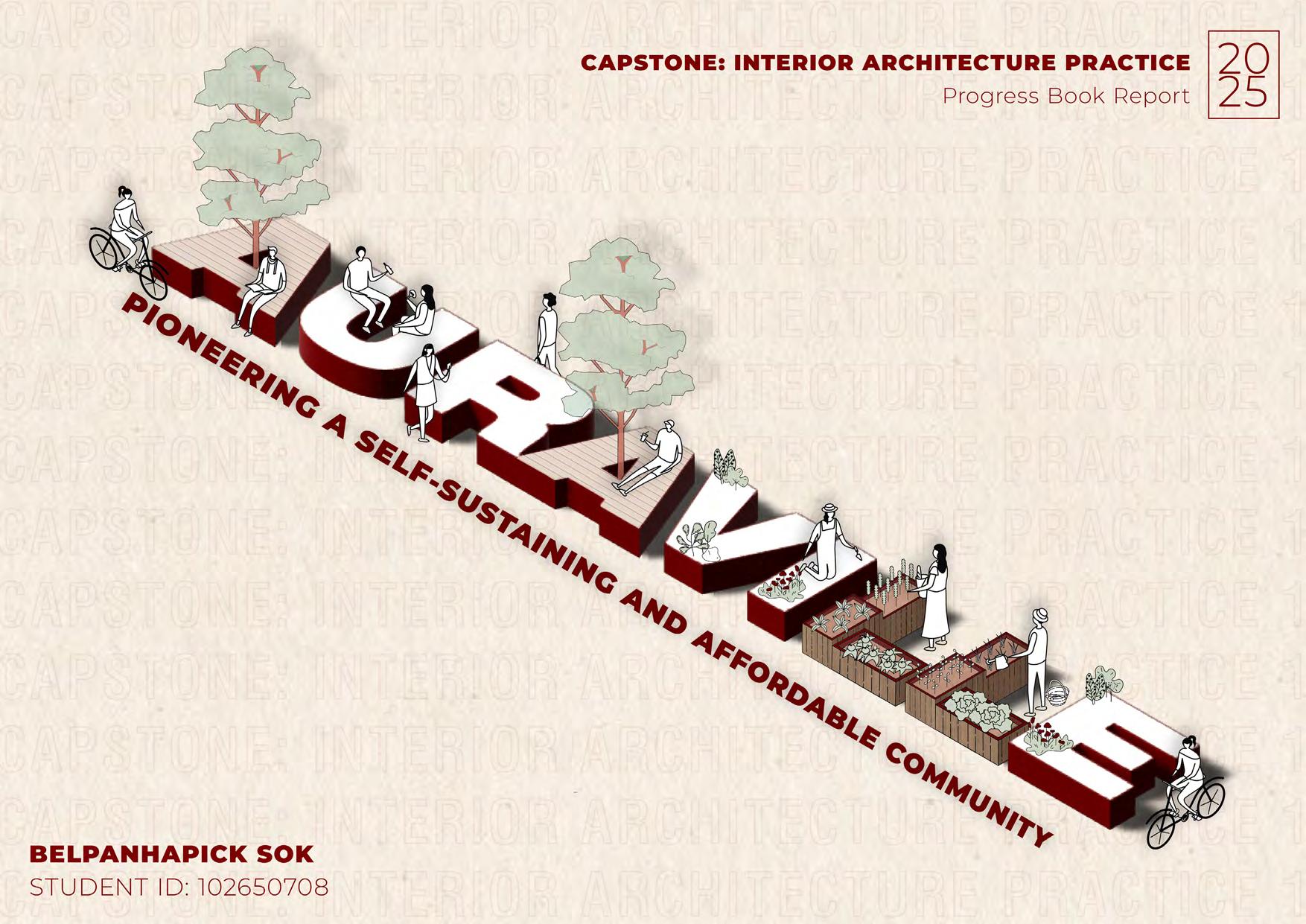

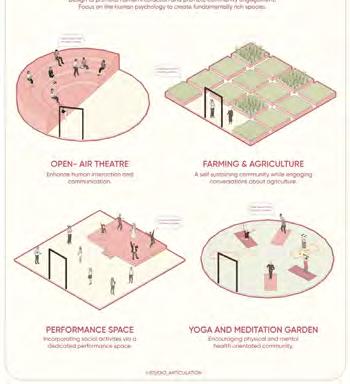

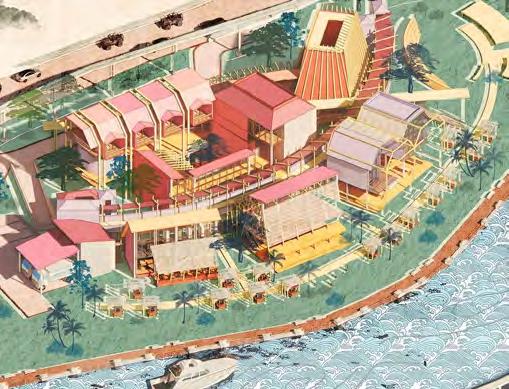

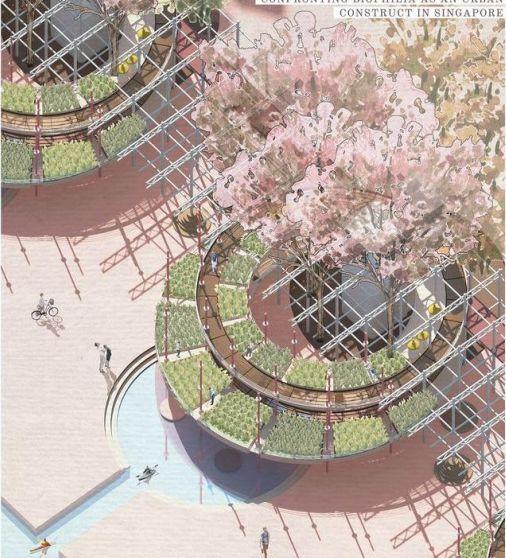

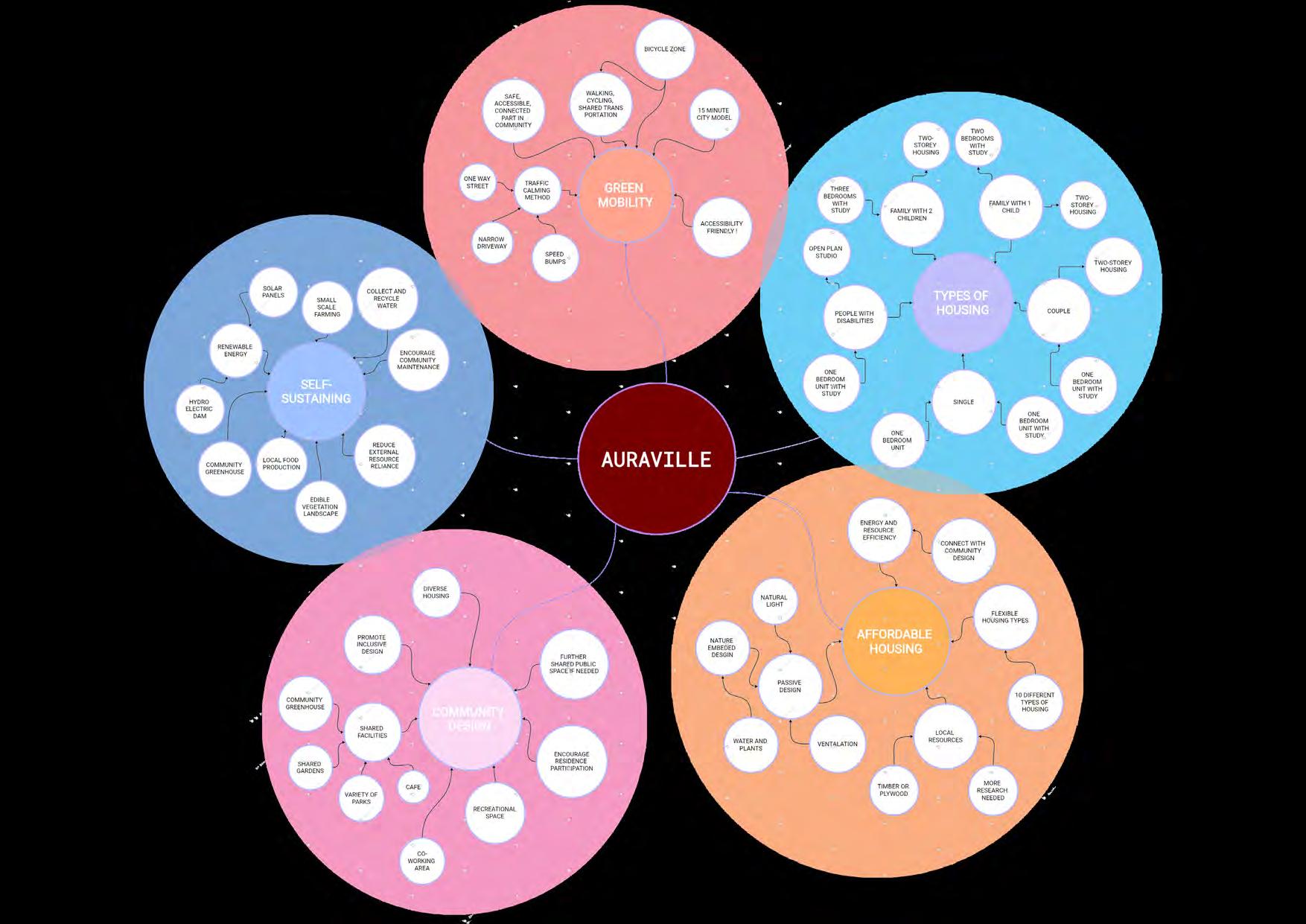

Auraville explores how architecture can create a self-sustaining, affordable community where green mobility is seamlessly integrated into daily life. Designed in response to Australia’s housing and environmental challenges, the project supports adults aged 25–50 with cost-effective living solutions that prioritize both individual well-being and environmental resilience.

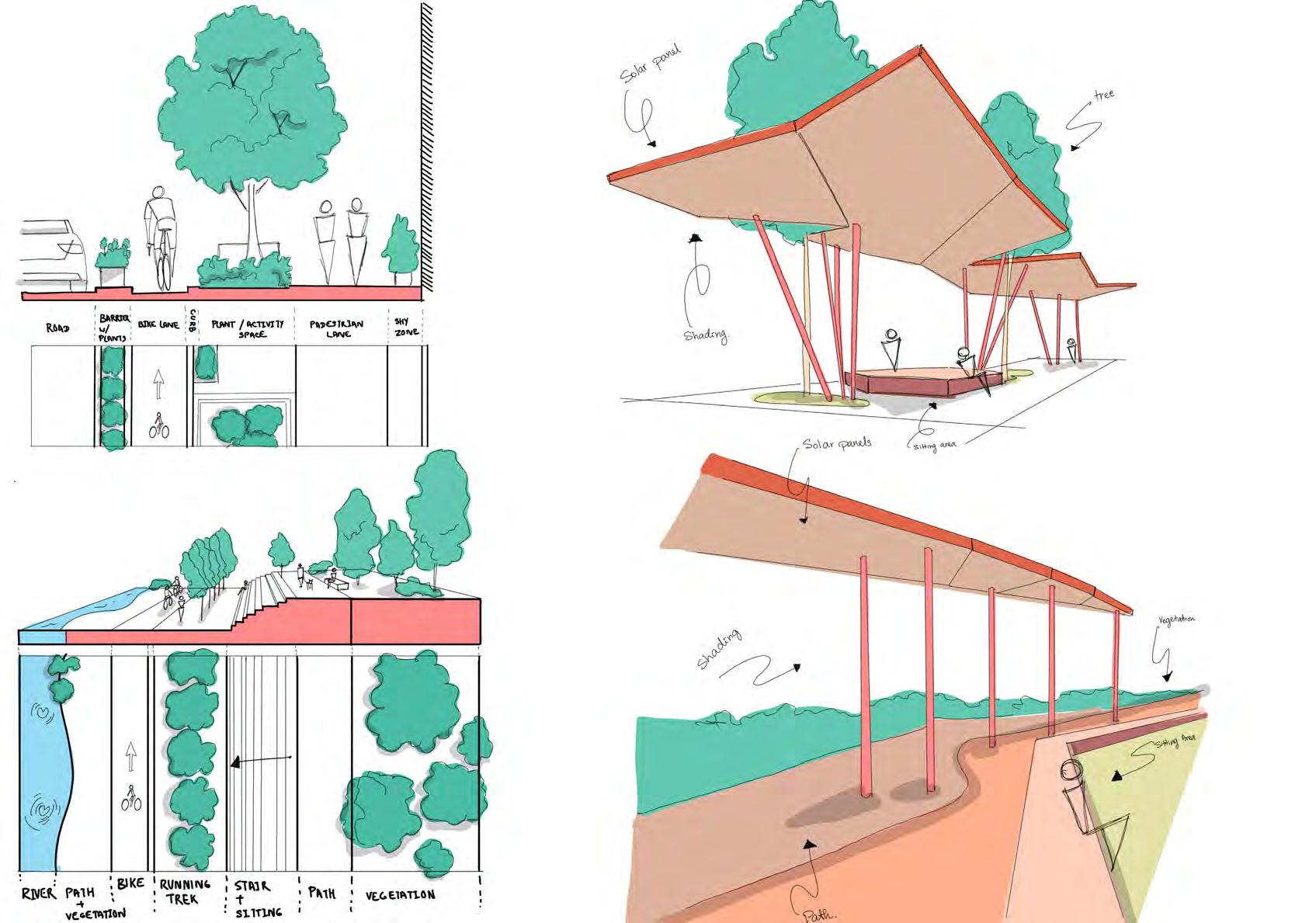

The proposal includes four distinct housing typologies to reflect diverse family needs, alongside a comprehensive masterplan that integrates housing, zoning, roads, and a vibrant community hub. The design incorporates renewable energy from solar and hydro sources, and promotes low-impact mobility through cycling and green mobility, envisioning a people-first community where affordability, sustainability, and connection define everyday life.

36 YEARS OLD

42% MORTGAGE 39.1% PRICE INCREASE

Australia’s average first home buyer is closer to 36 years old whereas in 1970 the average was just over 25 yers old (Global survery, 2024).

House prices in Australia overall have also jumped by 39.1% in the last five years (BBC, 2022).

Australians had to use almost 42% of their income to make their mortgage payment whereas the suggested mortgage should not exceed more than 30% (Global survery, 2024).

BALANCING SUSTAINABILIITY AND AFFORDABILITY RESOURCE MANAGING AND ECOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES PUBLIC PERCEPTION GREEN MOBILITY ADAPTION SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY INTEGRATION

- Costs: Sustainable design often raises initial costs.

- Passive Design: Reduces energy use and long-term expenses.

- Smart Materials: Uses local and recycled resources.

- Shared Systems: Communal transport, gardens, and energy lower costs.

- Integration: Green Mobility needs to be planned to the layout at the beginning of the development.

- Accessibility: Designs must be inclusive for everyone.

- Connectivity: Green mobility needs to be easy access to reduce the use of cars.

- Safety: The design needs to address safety for people.

- User Adoption: Users might take a while to adapt to green mobility adoption.

- Maintenance: Green mobility systems need long-term maintenance

- Energy Demand: Balancing high energy needs with renewable sources, especially during low-production periods.

- Waste Management: Incorporate community waste in recyclable or compostable without overwhelming systems.

- Biodiversity Loss: Disruption of local ecosystems and habitats during construction.

- Land Use: Balancing development with the preservation of natural spaces.

- Exclusionary Design: The design should include all abilities, ages, and backgrounds to achieve balance in the community.

- Privacy vs. Social Interaction: This can be difficult and potentially lead to isolation or overcrowding.

- Lack of Community Involvement: Community involvement is the key factor to understanding the community’s needs.

- Insufficient Social Spaces: Lack of communal spaces or social infrastructure can hinder community cohesion and interaction.

- Housing Inequality: can result in segregation by income, limiting

- Skepticism Toward Sustainability: Can be seen as unrealistic, expensive, or inconvenient.

- Resistance to Change: Adapting to new living models can be seen as a challenge.

- Misunderstanding of Green Mobility: Residents might be unfamiliar with or distrustful of alternative transport.

- Fear of Isolation: The community might be perceived as too remote or self-contained, leading to concerns about social or cultural disconnect from wider urban areas.

- Perceived Quality of Life: Rising concern for limited services, entertainment, or economic opportunities compared to urban settings.

In response to environmental pressure and the surge in standard living costs, there is a critical need to reconceptualize how communities are designed and sustained. In Australia, it is mentioned that residential property value has increased by around 20% in just over a year between March 2009 and March 2010, and Australian mortgages have significantly increased from 32% in 1990 to 142% in June 2010 respectively (MacKillop, 2013). To highlight this issue further, there has been an inadequate need for the necessary infrastructure to meet the rapid increase in the urban population especially homeownership for young people and middle to low-income households (Lai et al., 2023). This situation has led to ‘housing stress’ where more than 30% of the homeowner’s income is dedicated to housing costs (Sivam & Karuppannan, 2017). This literature review will examine the necessity for developing a self-sustaining, affordable community that fosters carbon-neutral living while creating a stronger awareness of the community and minimizing environmental impact. Furthermore, this literature review will analyze how various authors assess the effect of affordable, sustainable housing and explore strategies for implementing a carbon-neutral and self-sustaining pathway for future communities based on case studies and their findings.

Affordable housing can be defined as housing that meets acceptable standards of location and quality without being excessively priced to ensure that residents can meet other fundamental living expenses (Lai et al., 2023). To homeowners, housing can be seen as a ‘nest egg’ or ‘safety net’ as it symbolizes a source of wealth or investment for an individual during their active life (MacKillop, 2013). However, it is fundamentally tied to the challenges of achieving sustainable development as these two provide complex relationships with one another (MacKillop, 2013). Sivam and Karuppannan (2017) identify key barriers to affordable housing in Australia, including the cost of land, provision of infrastructure responsibility, restrictive zoning laws, lack of stakeholder and government interference, and community support. They advocate for the concept of a “compact, well-connected urbanism concept” to lower the cost of affordable housing and promote livability (Sivam & Karuppannan, 2017). Further, Adabre et al. (2020) provide more additions to these challenges by categorizing the main factors of barriers into social, economic, environmental, and institutional. They identified policy and regulation rules, along with the shortage of skilled labor are some of the top issues globally (Adabre et al., 2020). The challenges are further complicated as sustainability measures integrating solar tech or insulation are often perceived as costly,further increasing the affordability problem for the targeted homebuyers (MacKillop, 2013). Lai et al. (2013) investigate these issues using a quantitative research method on homebuyer’s perception survey. It reveals that respondent’s socio-demographic backgrounds and their social status have significantly influenced their perspective on housing factors in the market (Lai et al., 2023).

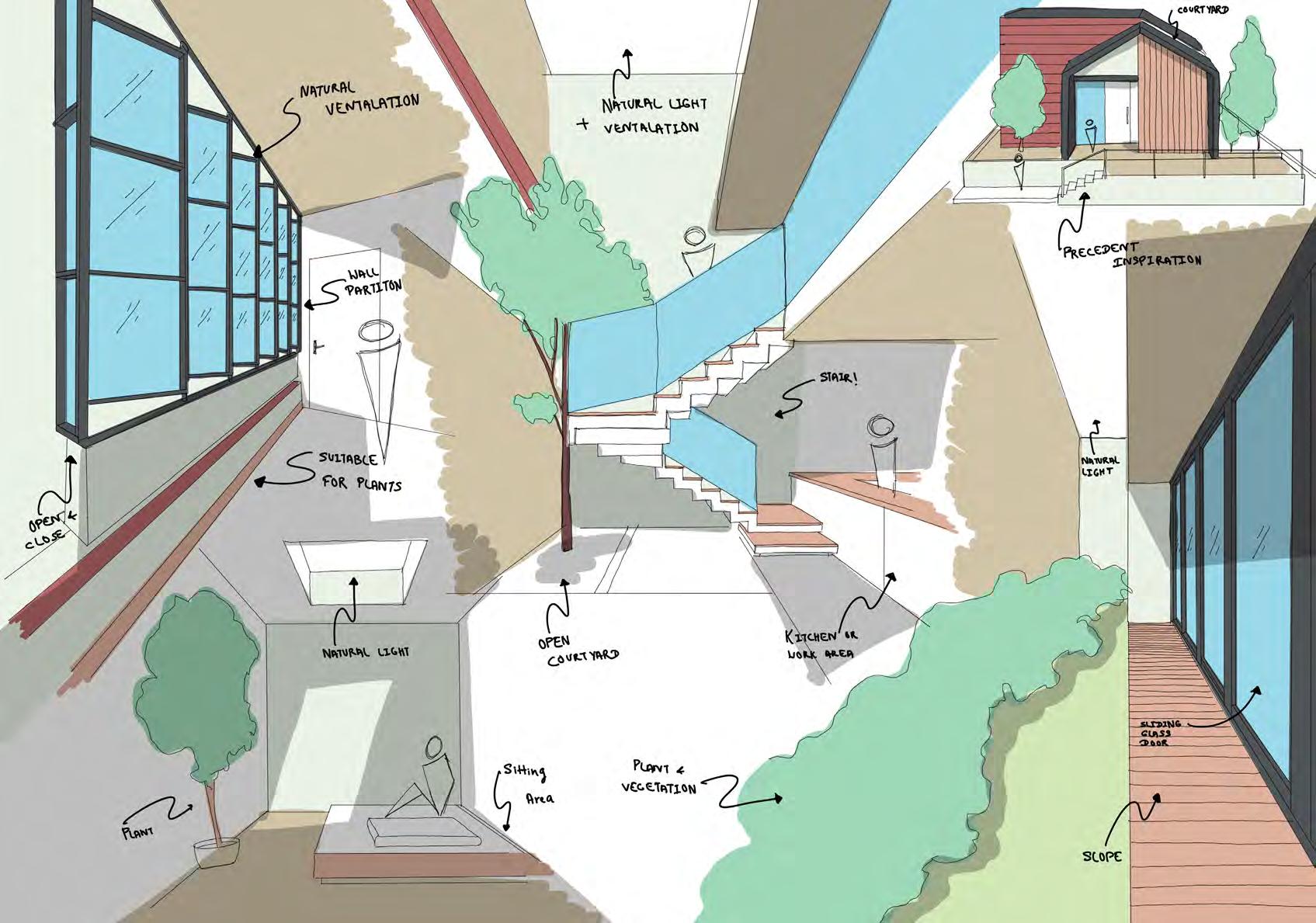

Feasible solutions to address these challenges are highlighted in the chosen articles. Promoting community participation in the housing design process, along with government involvement could be a potential pathway to achieving eco-efficient and affordable housing (Sivam & Karuppannan, 2017). Furthermore, Adabre et al. (2020) suggest that integrating sustainability practices into the policy framework could help identify key barriers and establish crucial criteria for developing strategy for sustainable and affordablehousing. On the other hand, a smarter design approach, such as passive design for shading and cooling combined with vernacular architecture can cre-

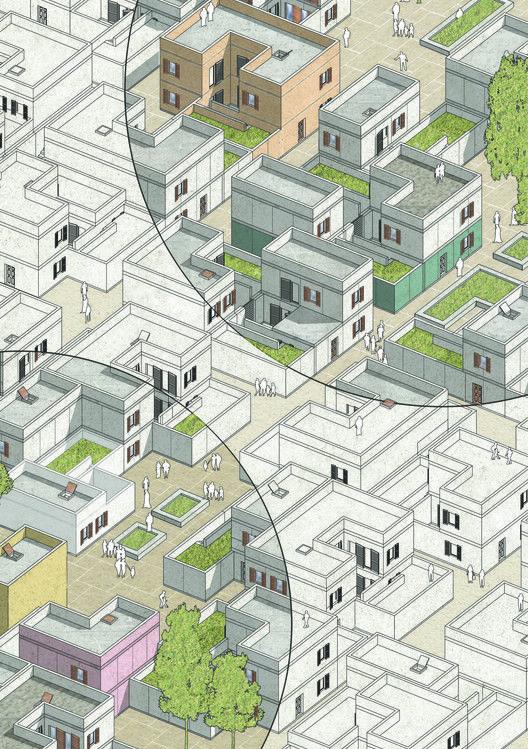

Key design strategies drawn from these case studies are highlighted in the mentioned articles. A self-sustaining village with low interference can be achieved through the use of passive solar design, water resource utilization, and local materials, creating a comprehensive set of design tools to meet the community’s operational goal (Xie et al., 2022). To strengthen key design strategies, incorporating hybrid and renewable energy resources such as solar power, biomass, biogas, wind, and geothermal from local resources can decentralize energy storage and evenly distribute power across the community (Kaur et al., 2024). Moreover, Haahs (2012) stresses the importance of effective land use through compact, mixed-use design strategies that place all the necessary infrastructures within reach, which can encourage pedestrian traffic flow and minimize the need for automobiles and parking.

The development of self-sustaining communities presents a systematic approach to environmental concerns, increasing infrastructure needs, and rising population. Haahs (2012) advocates for compact, “cellular” urban development that uses passive design strategies to promote walkability and reduce vehicle dependency, in contrast to “Fractured development” where every zone is separated. Haahs emphasizes the use of transit-oriented development (TOD) to minimize car dependency and unnecessary infrastructure demands, encouraging a stronger connection between the community (Haahs, 2012). The article supports the argument that ‘we can no longer afford to build cities for cars, not people’, which reflects the paper’s primary focus (Haahs, 2012). Moreover, Kaur et al. (2024) present a case study on energy self-efficiency in rural villages using bioengineering technology: hybrid optimization model for electric renewables (HOMER) and techno-economic analysis (TEA) models to utilize accessible onsite hybrid renewable energy sources. Their findings demonstrate that these technologies can pinpoint cost-effective energy solutions while supporting the local economy (Kaur et al., 2024). Further, another case study by Xie et al. (2022) examines a village operating within a low-interference cycle that can function independently without relying on non-renewable energy sources. Their findings also show that the village solely focuses on integrating passive design, a green economy cycle, ecological

The implementation of green mobility also plays a significant role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting carbon-neutral living. Echeverría et al. (2022a) conducted a case study analyzing the demographics and behaviors of green mobility users to identify which groups rely more on adopting a sustainable mode of transportation. The study found that individuals with higher education and income were more likely to prefer green transport options, indicating a gap in access equity compared to other groups (Echeverría et al., 2022a). Further, another case study by Echeverría et al. (2022b) explores the connection between individuals’ emotional well-being and their transportation choices. The study suggests that those who use active transport methods, such as walking or cycling, reported the highest level of well-being, followed by private car users, whereas public transport users reported the lowest level of satisfaction and emotional well-being, indicating another significant barrier to the adoption of green mobility (Echeverría et al., 2022b). Moreover, Tammaru et al. (2023) highlight a major equity concern from the gap between urban and suburban populations, advocating for an equity-centered approach to the mobility model. They argue that transitioning to sustainable mobility requires not only infrastructure but also social fairness, addressing capability, coupling, and authority constraints to promote a quicker transition to sustainable mobility (Tammaru et al., 2023).

Essential design approaches have been highlighted in the case studies to suggest the importance of integrating green mobility early in the master planning of new communities; which includes replacing underused parking infrastructure with transit-oriented development (TOD) and promoting active mobility (Haahs, 2012). Additionally, including well-being and social equity in the design, can further encourage the community to adopt a more sustainable practice toward a green lifestyle (Echeverría et al.,

Future adaptability is a critical component in designing self-sustaining, affordable communities that support carbon-neutral living, ensuring long-term resilience and functionality. MacKillop (2013) suggests a new housing design approach that prioritizes affordability and sustainability through a passive design, reducing energy use, and minimizing community. Additionally, community participation and adaptive zoning policies can ensure eco-efficiency housing and community resilience Sivam & Karuppannan, 2017). Kaur et al. (2024) highlight the importance of improving hybrid renewable energy solutions to support sustainable rural growth over time. Future planning should also focus on low-interference cycles to minimize human impact, establish a green economy cycle, and incorporate community feedback (Xie et al., 2022). Furthermore, Tammaru et al. (2023) stress the need for a long-term planning approach in transportation and green living, particularly mobility access between urban and suburban areas.

In conclusion, integrating affordable housing, self-sustaining communities, and green mobility offers a promising approach to creating environmental responsibility and social equity in the community. By addressing the ongoing challenges of affordability, sustainability, and the integration of green mobility in the community, this literature provides a valuable pathway for reducing environmental impact and improving the quality of life. However, the mentioned key factors such as balancing affordability with sustainability, ensuring future adaptability to the proposed factors, and equitable distribution of resources between urban and rural areas remain central to implementing a successful strategy. It is crucial to continue focusing on solutions that are not only sustainable but also adaptable to future needs, especially with the ever-growing population.

- Design compact layouts based on the 15-minute city model

- Encourage sharing vehicles in the community if applicable

- Provide equality in every accessibility: age, disabilities, and abilities.

- Using shared amenities (e.g. laundry, co-working spaces) to reduce expenses

- Design a mix of small to medium homes for different family sizes

- Use cost-effective, locally sourced, and sustainable materials

- Using passive design to maximize comfort

- Modular and prefabricated building methods to reduce costs

- Focus on low-maintenance design to reduce long-term living costs

- Integrate solar panels and hydroelectric systems for energy generation

- Use rainwater harvesting and water recycling systems

- Plan for edible landscapes and shared community gar dens

- Minimise waste with composting and recycling infrastructure

- Create passive designs for heating, cooling, and lighting

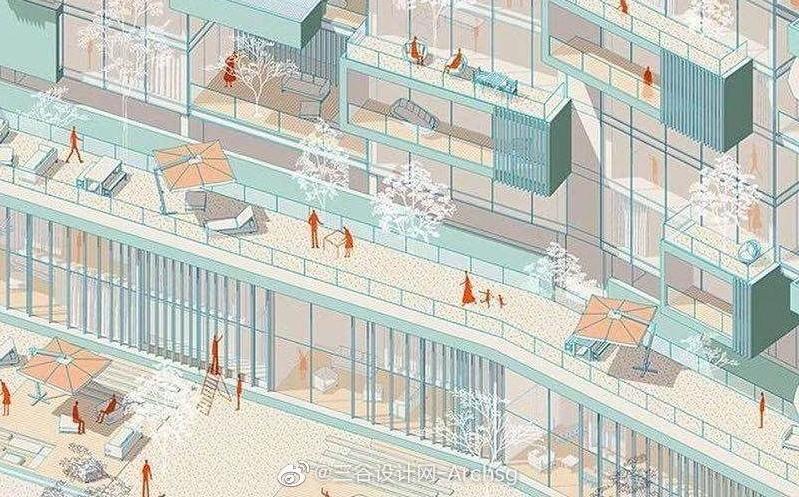

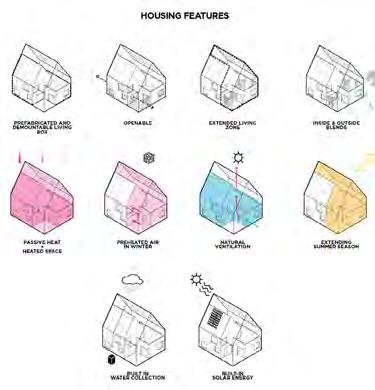

Collaboration between IKEA, Space 10, and EFFEKT focuses on designing affordable housing and combating climate change. Almost all components and materials would be able to be disassembled and easily replaced, reused, and recycled over the building’s lifespan — even the building itself could be retrofitted or repurposed

By EFFEKT architects, design a community that can produce all of their food and energy creating more resilient solutions for the future. The concept is similar to the idea of a cooperative community where each village would include a series of public squares, integrated with technologies like electric car charging points. Individual homes would integrate photovoltaic solar panels to generate power and heat water. They would also feature passive heating and cooling systems, as well as natural ventilation, helping to keep electrical demand low.

- Length: Approximately 40 kilometers (Melbourne’s second major river)

- Location: Flows through the northwestern suburbs of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

- Source: Confluence of Jackson’s Creek and Deep Creek near Bulla

- Mouth: Joins the Yarra River at Yarraville, eventually flowing into Port Phillip Bay

Maribyrnong River is well known for:

- Cultural significance: It’s a sacred site for the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people, with a long history of traditional use.

- Industrial past: Was once a major industrial corridor, with factories and munitions plants, especially during the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Recreation: Popular for walking, cycling, kayaking, and the Maribyrnong River Trail, with parks like Brimbank and Pipemakers.

- The Maribyrnong River supports a diverse range of native plants and animals, functioning as a valuable ecological resource and a self-sustaining habitat for local wildlife.

- The Maribyrnong River Trail is one of Melbourne’s best-known shared-use paths for walking, running, and cycling, stretching for over 28 km.

- The riverfront is popular for picnics, kayaking, fishing, and rowing especially near Flemington and the Footscray area.

Shark and dolphin skeletons have been found under Maribyrnong Park, and oyster and other shells at Steele Creek.

The Aboriginal people of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong of the Kulin Nation have lived along the Maribyrnong River valley for at least 40,000 years, and the name Maribyrnong derives from the phrase ‘Mirring-gnay-bir-nong’, meaning ‘I can hear a ringtail possum’.

The Maribyrnong Defence Site in Victoria is historically significant as one of Australia’s key military manufacturing facilities, established in 1908. It played a vital role in producing explosives and munitions during both World Wars and was also home to military research laboratories. The site included a Remount Depot that supported the Australian Light Horse Brigade in World War I and was the home of “Sandy,” the only horse to return from Gallipoli. Operations ceased in 2000, and the site is now heritage-listed, with plans underway for its remediation and redevelopment.

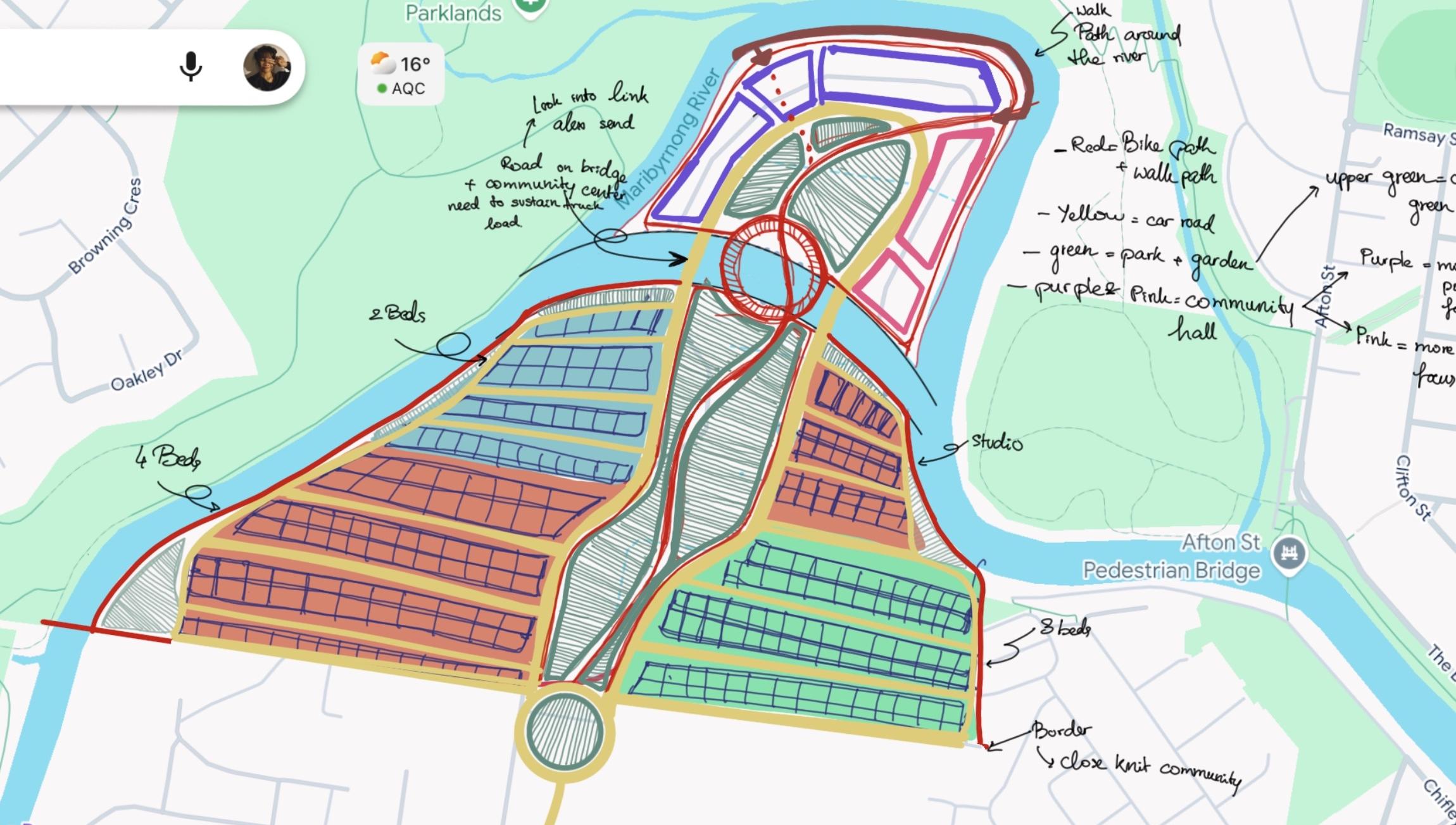

Defence Site Maribyrnong is a 127.8 hectare parcel of Commonwealth land located at 2 Cordite Avenue, Maribyrnong, in the City of Maribyrnong.

The site’s historical use by Defence resulted in contamination to land and groundwater which has only partially been remediated.

This site urban context has been taken out from “ Defence site

maribynorng statement of policy intent by the victoria government, 2018”

The victorian government is committed to preparing a planning framework in critical points below:

Establishment of a new community integrated with adjoining

Home to new housing development such as social and affordable housing

New recreational activies spaces and facilities for the public

Covenient access to public and active transport network

Designated commute area to encourage green mobility

Urban landscaping with a variety of native flora and fauna

Active and passive surveillance of public places to enhance safety and amenity

Remediation that ensures human health and environment on the

Community, commercial, educational, leisure, recreational and retail facilities and opportunities for local employment

Public access along the entire Maribyrnong river frontage

Conservation of indegenous and historic heritage

Practice waste, energy and water management, including onsite and downstram flooding

Underground servicing with minimal visual intrusion from fixtures and for fire safety

The photos below are images of the site location I gathered from the websites. Since the site is not yet open to the public, we can see that the site appears to be abandoned based on the building’s condition. There are some actions planned to preserve the site as a common heritage, however, further plans are to be discussed.

There is currently no fixed size limit for the chosen location, as the project is designed to be scalable and adaptable to future community growth.

Highpoint Shopping Centre is a major retail and lifestyle destination in Melbourne’s west, offering a wide range of fashion, dining, entertainment, and services all under one roof.

Maribyrnong College is a government secondary school in Melbourne’s inner west, renowned for its elite sports academy and strong academic programs, fostering excellence in both education and

The surrounding neighborhood of the site promoted a scene of a quiet area, suggesting a suitable environment for developing the

The 15th Essendon Sea Scouts, established in 1952 and based at Fairbairn Park in Ascot Vale, is a vibrant scouting group offering water-based and traditional programs for youth aged 5 to 25, operating from their riverside hall known as S.S.S.

Jack’s Magazine is a heritage-listed 19th-century bluestone explosives storage facility on the Maribyrnong River, built in 1878 and now managed by Working Heritage for future community use.

Pipemakers Park is an 8-hectare heritage-listed park in Maribyrnong, Melbourne, featuring historic industrial buildings, wetlands, and the Living Museum of the West, offering a blend of natural beauty and cultural history along the Maribyrnong River.

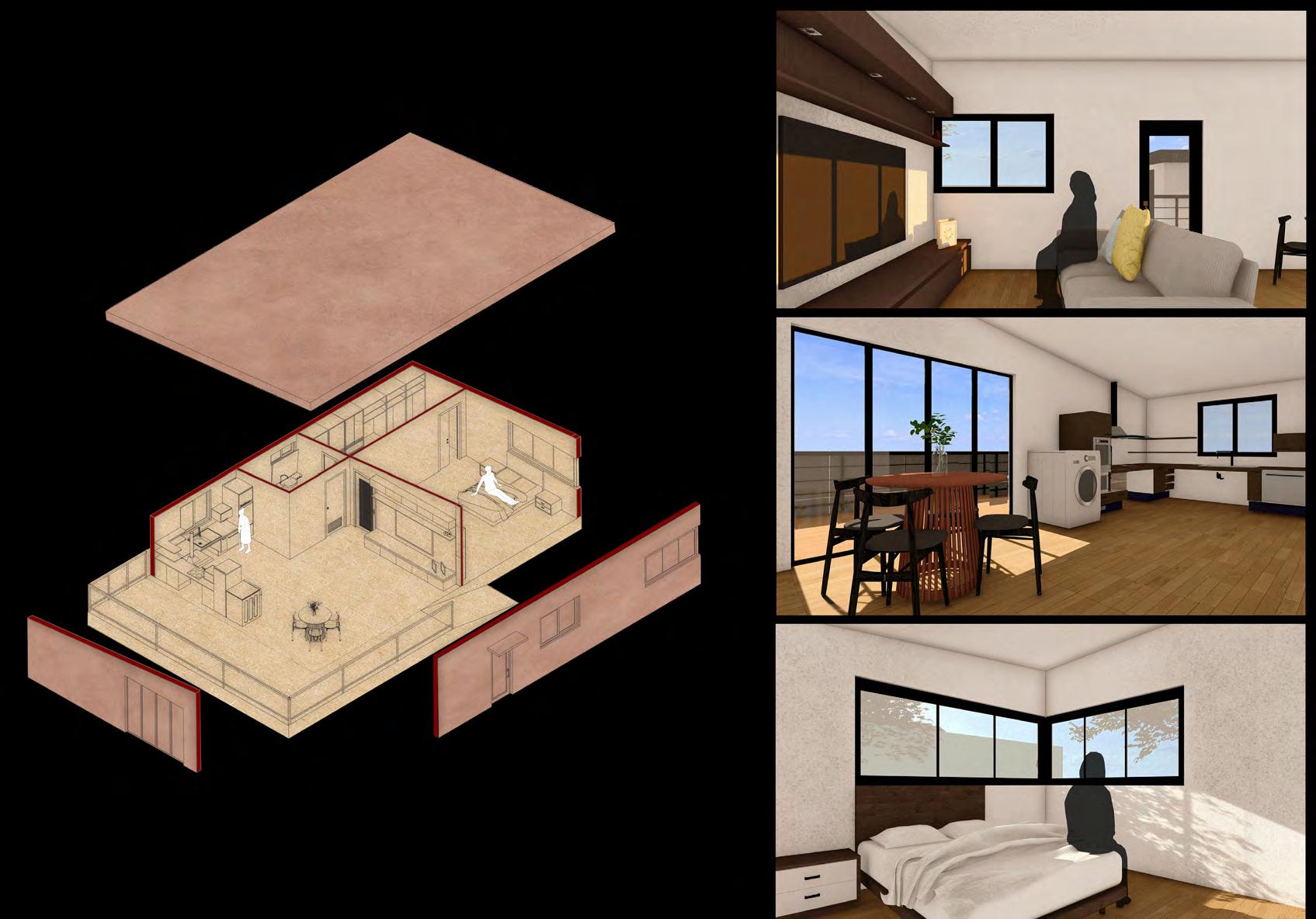

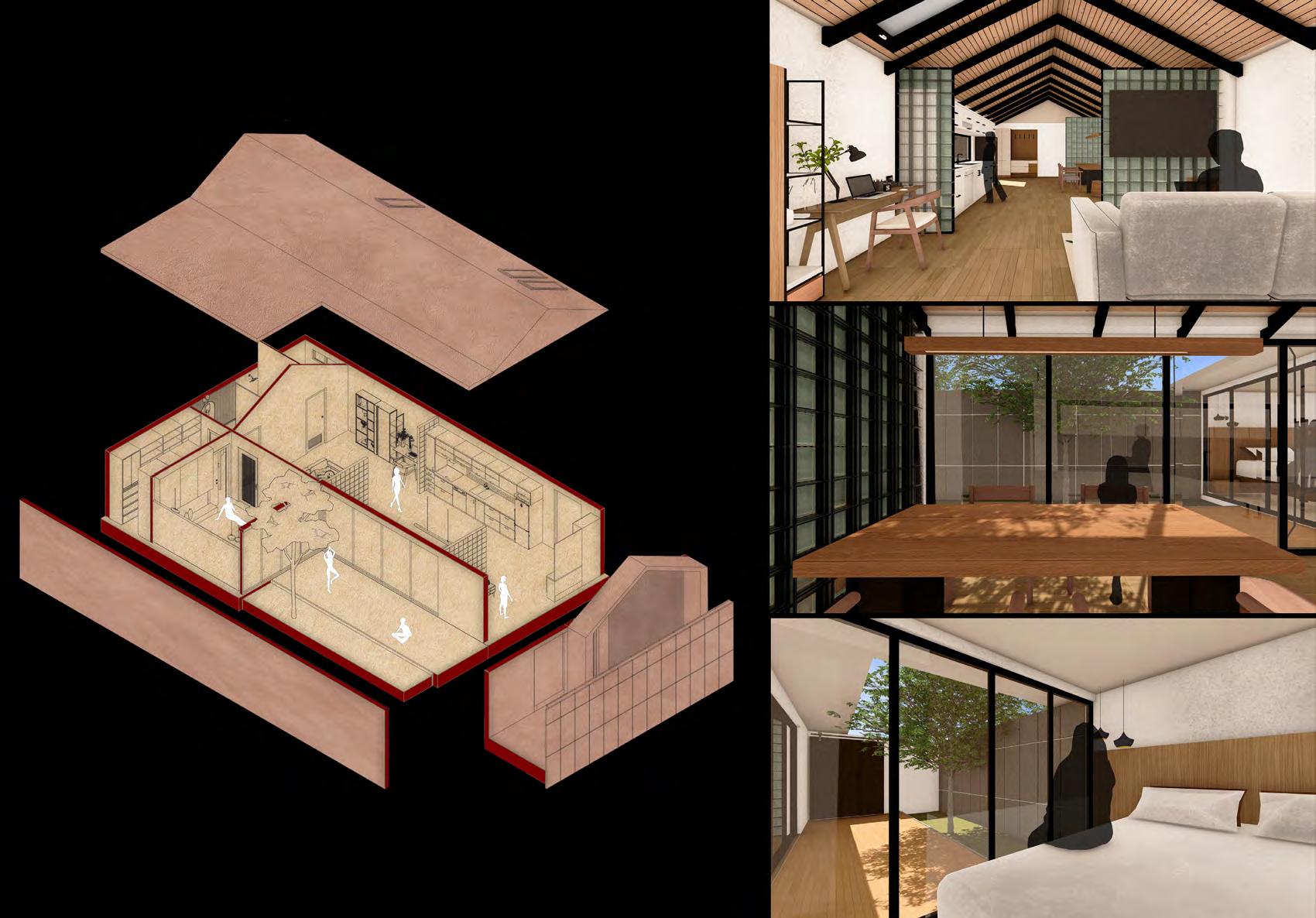

SINGLE

- One bedroom COUPLE

- One bedroom with study FAMILY WITH ONE CHILD

DIFFERENTLY ABLED PEOPLE

- Three bedrooms with study

- Two bedrooms with study FAMILY WITH TWO CHILDREN

This project will accommodate 5 unique households, each presenting with 1 type of housing design.

- One bedroom with study

PRIMARY STAKEHOLDERS

- Adults aged range from 25 to 50

- Future Residents of Auraville

- Local Government & Urban Planners

- Environmental & Sustainability Advocates

SECONDARY STAKEHOLDERSTERTIARY STAKEHOLDERS

- Architects, Designers & Urban Developers

- Public Transport Authorities & Mobility Providers

- Construction & Renewable Energy Providers

- Community Organizations

- Academic Institutions & Policy Researchers

- Utilities provider & Service companies

- Environmental & Sustainable organizations

- Local Businesses & Entrepreneurs

- Wider Society & Future Generations

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

SHARED

AMENITIES

RENEWABLE ENERGY

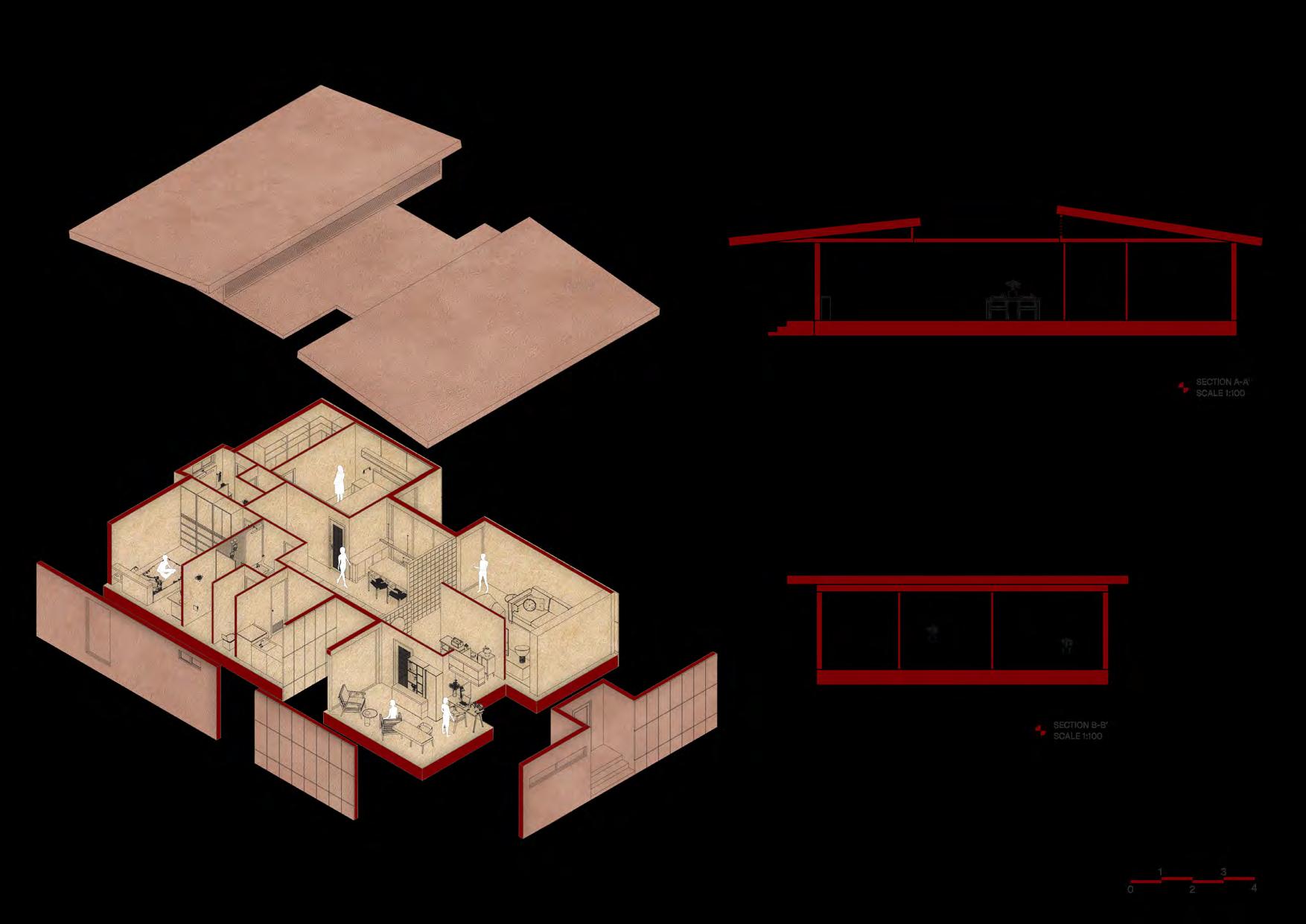

2. LIVING ROOM

3. STUDY/OFFICE ROOM

4. KITCHEN

5. DINNING AREA

6. ACCESS TO COURTYARD

7. GARAGE

8. BATHROOM

9. LAUNDRY ROOM

10. MASTER BEDROOM

11. WALK-IN CLOSET

12. BATHROOM

13. BEDROOM

6.

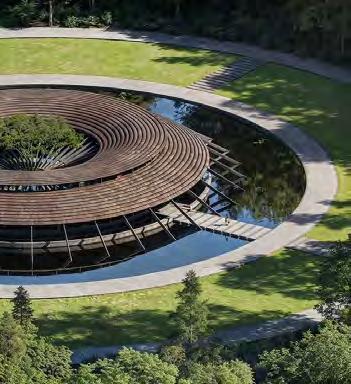

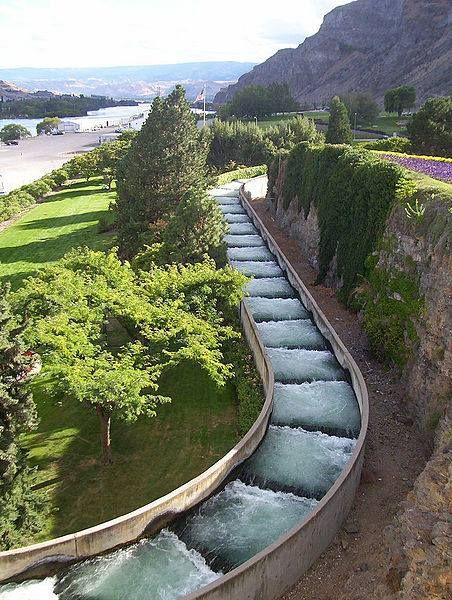

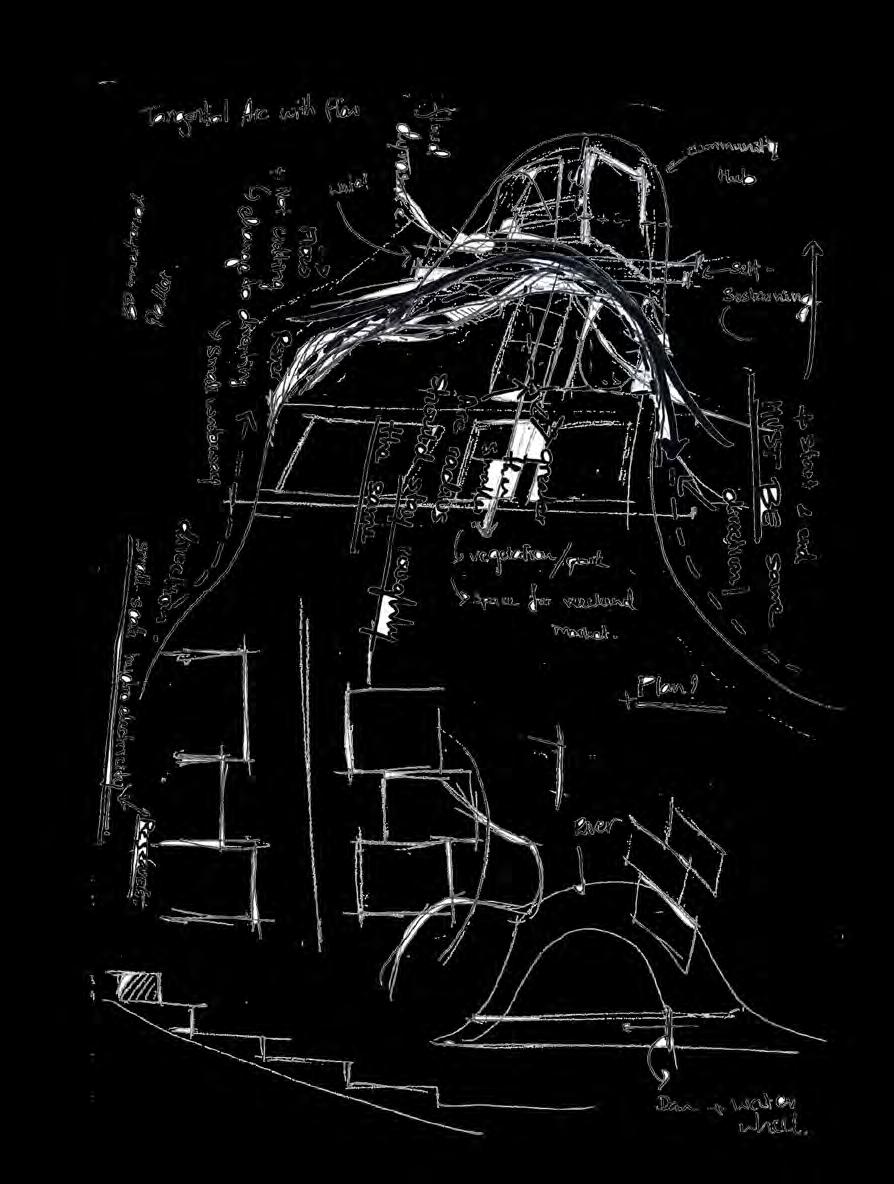

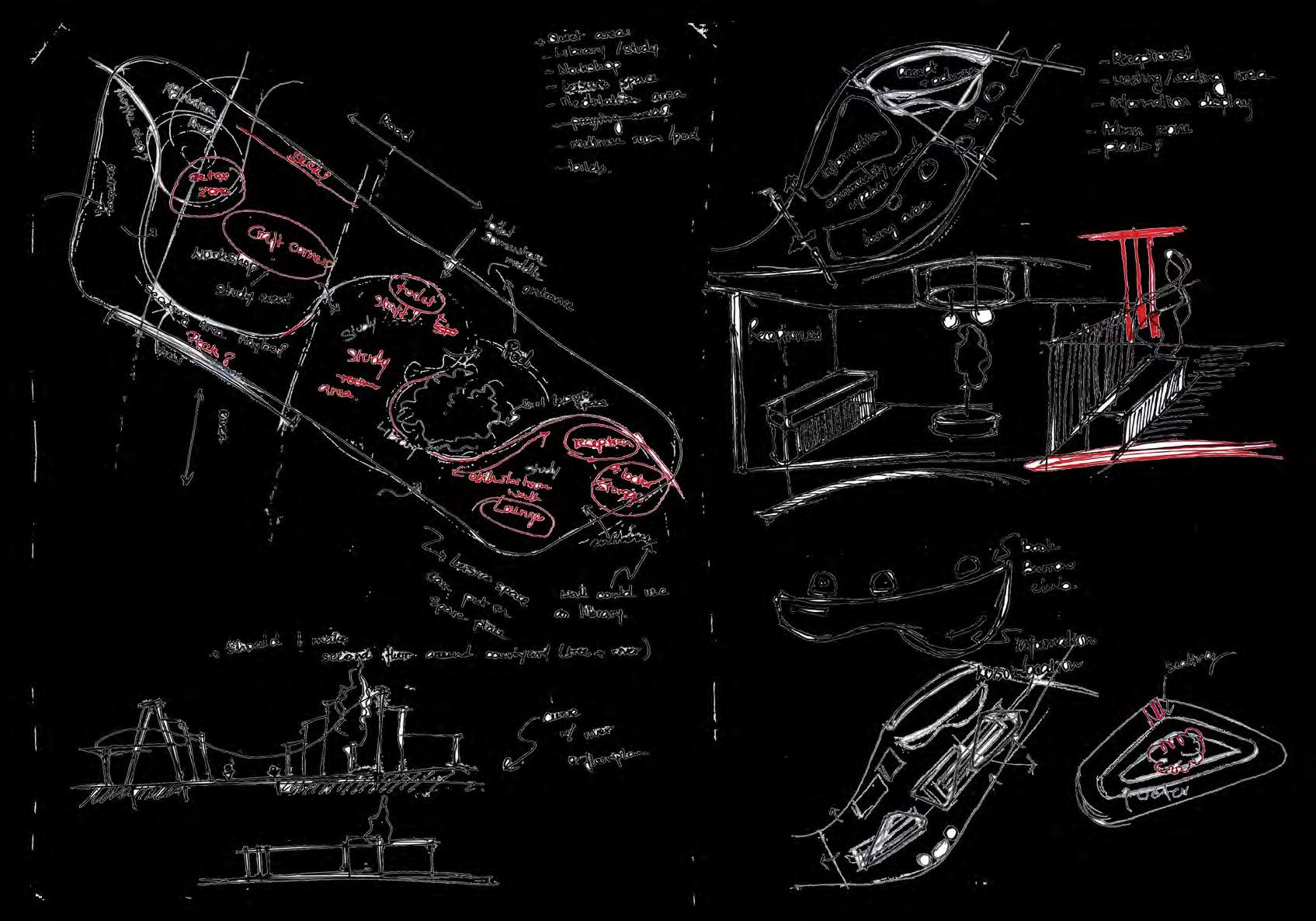

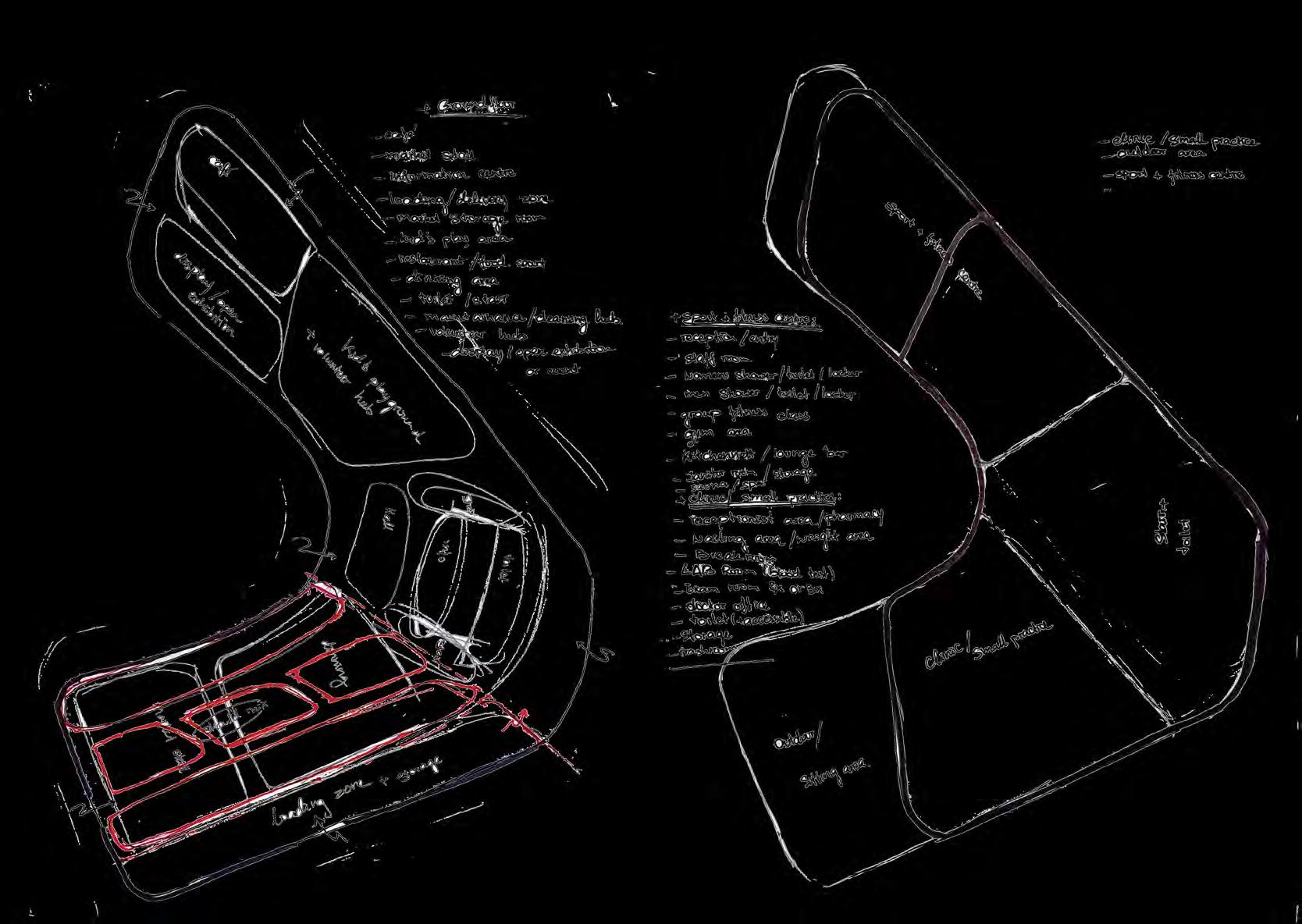

The process of understanding the river flow and diverting it to the masterplan

The community hub layout is shaped by the site’s natural form

Drawing from an understanding of the site’s geography and topography, the water diversion system has been integrated to follow the natural contours of the land and the existing river flow. The design aligns with the site’s arching radius, creating a balanced relationship between the two landforms. Guided by principles of fluid dynamics and tangential flow, this approach not only enhances spatial harmony and landscape integration but also promotes energy efficiency, mitigates erosion, optimises infrastructure, and ensures that water is channelled effectively to areas of need.

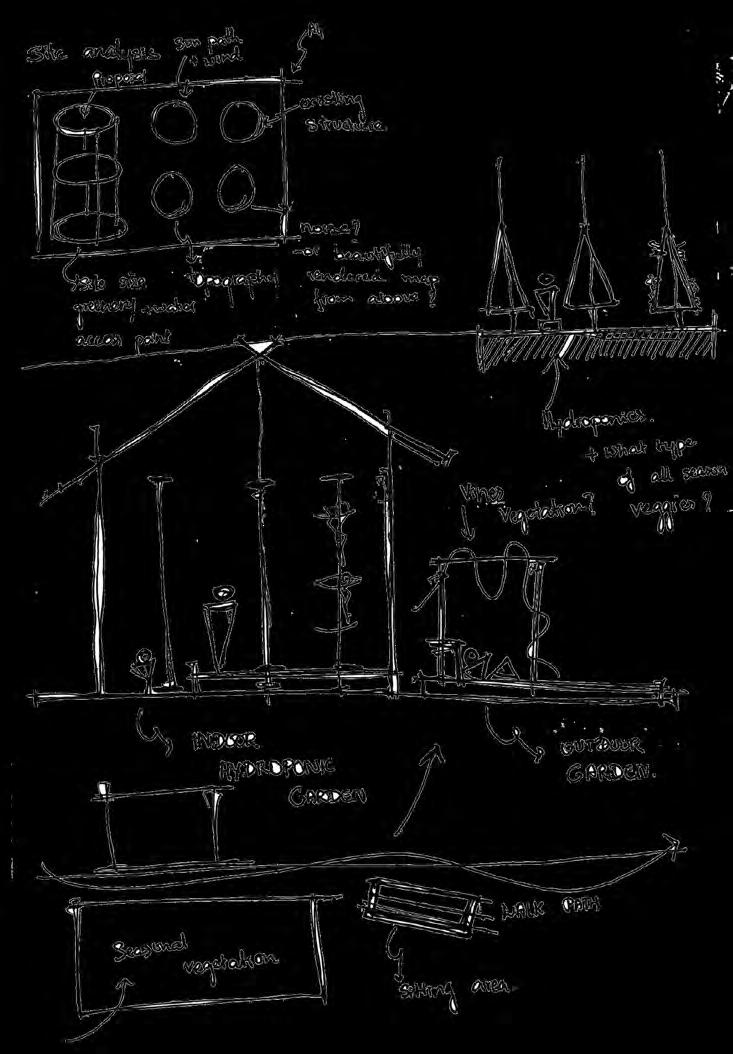

Site analysis planning

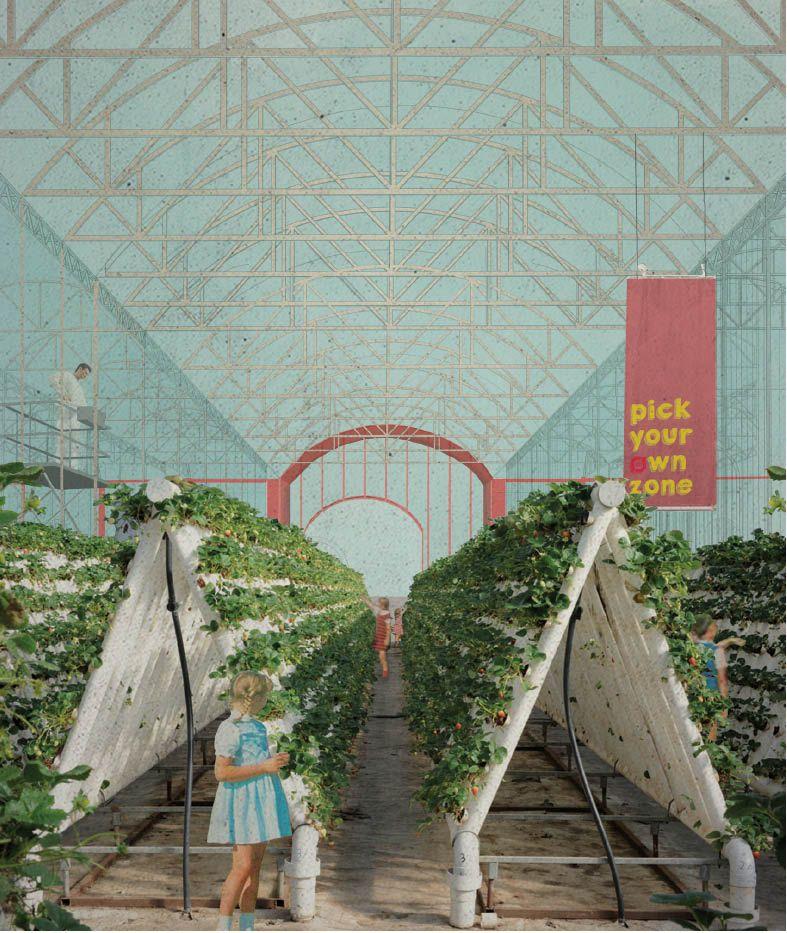

Hydroponics layout idea

Hydroponics and other types of garden layout idea

Greenhouse design functions and layout

Layout brainstorming Other layout ideas for the greenhouse design

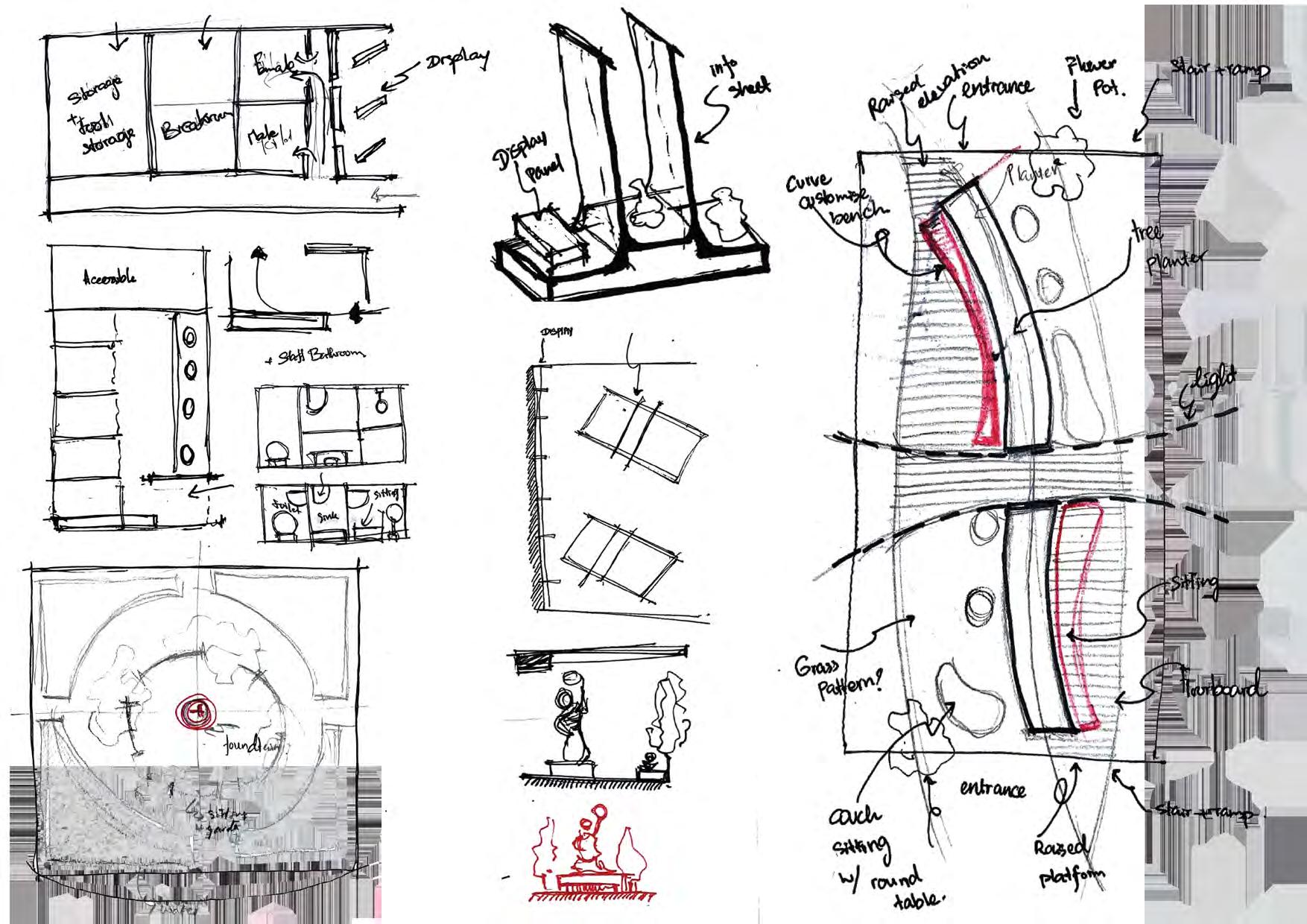

Facade view concept, with courtyard in the midddle

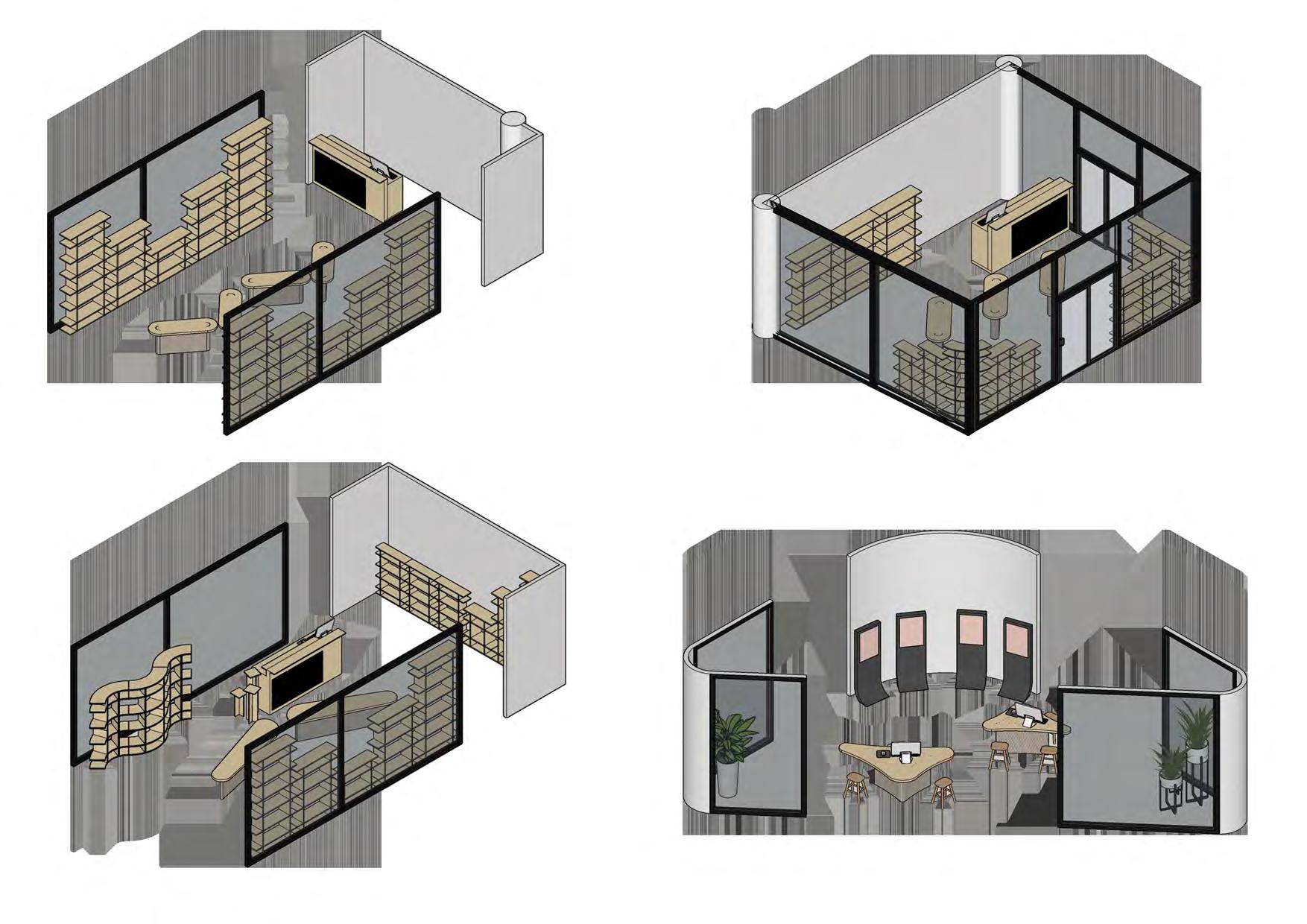

The greenhouse is divided into two zones: a private working area for staff and a public greenhouse space open to visitors. These are separated by a central open courtyard that enhances light, ventilation, and visual connection. The private zone houses key operational functions, while the public area features three cultivation systems such as: hydroponics, soil-based planting, and aquaponics along with a workshop and nursery, forming an integrated and sustainable growing environment

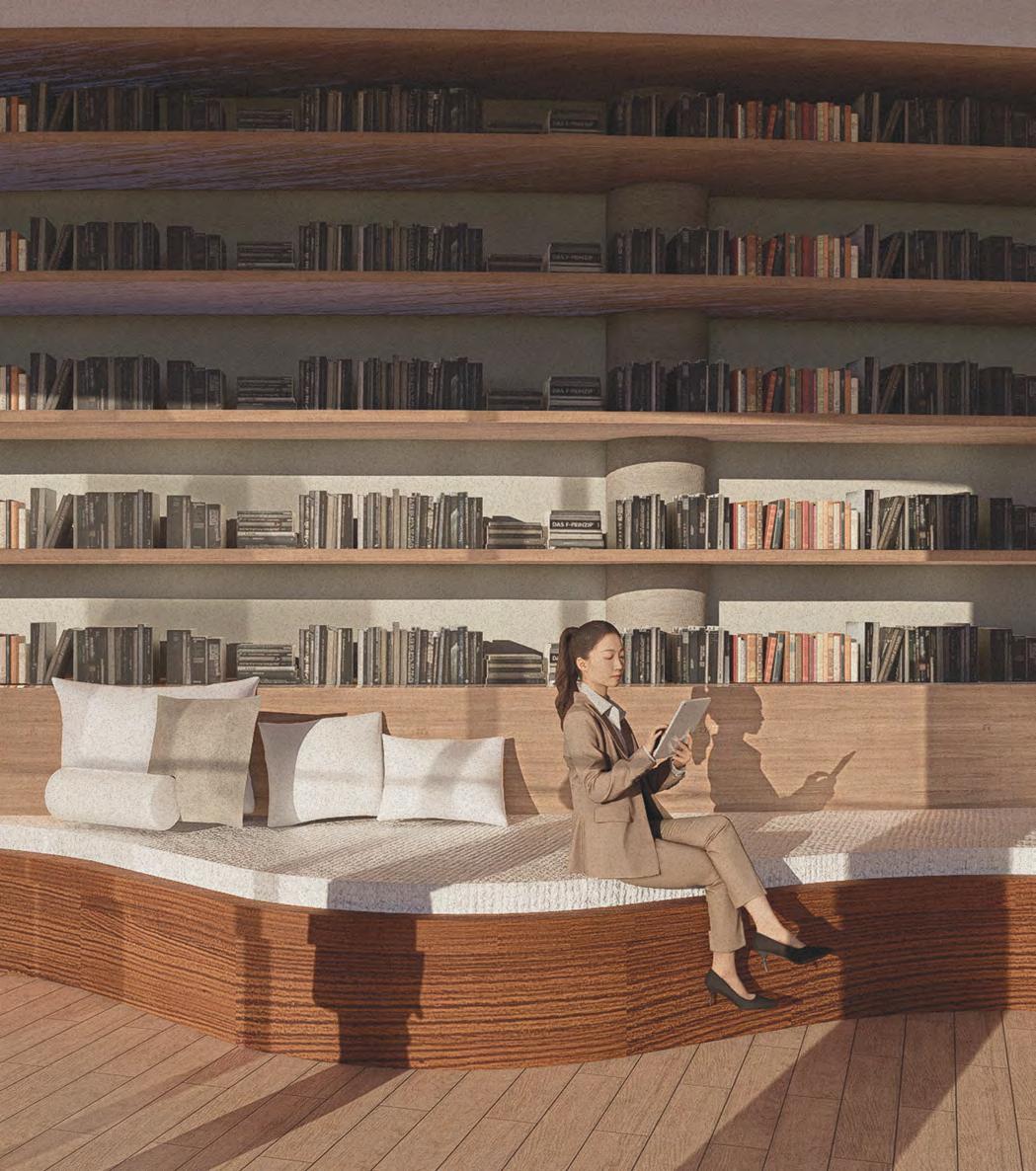

The library’s layout draws inspiration from the wave patterns of the Maribyrnong River, translating its natural fluidity into a series of curved spatial forms. This flowing geometry defines the interior organisation, clearly separating zones for social interaction, focused study, silent reading, and reflection. Each seating and spatial arrangement is carefully designed to integrate nature and creativity, fostering a calming and inspiring atmosphere for users. Positioned along the proposed diverted river, the library embraces its landscape context, offering a new architectural approach that enhances both infrastructure and visual connection to the water, creating a tranquil environment for study and work.

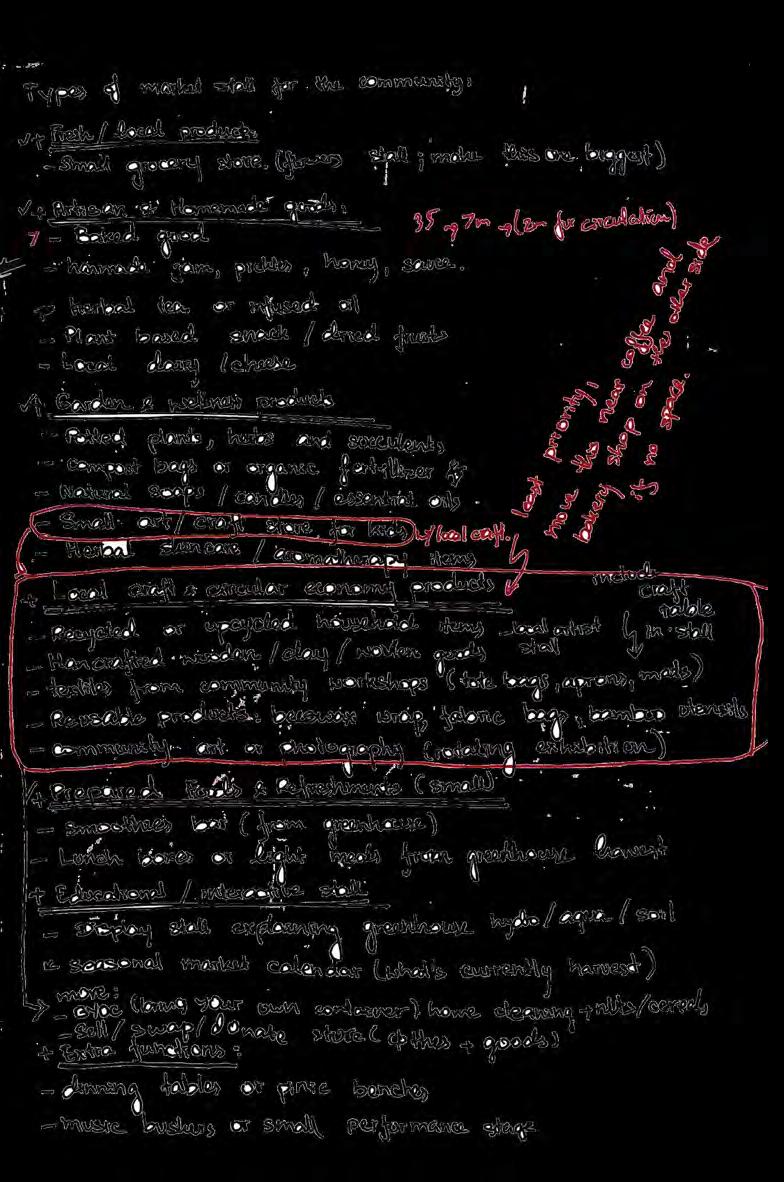

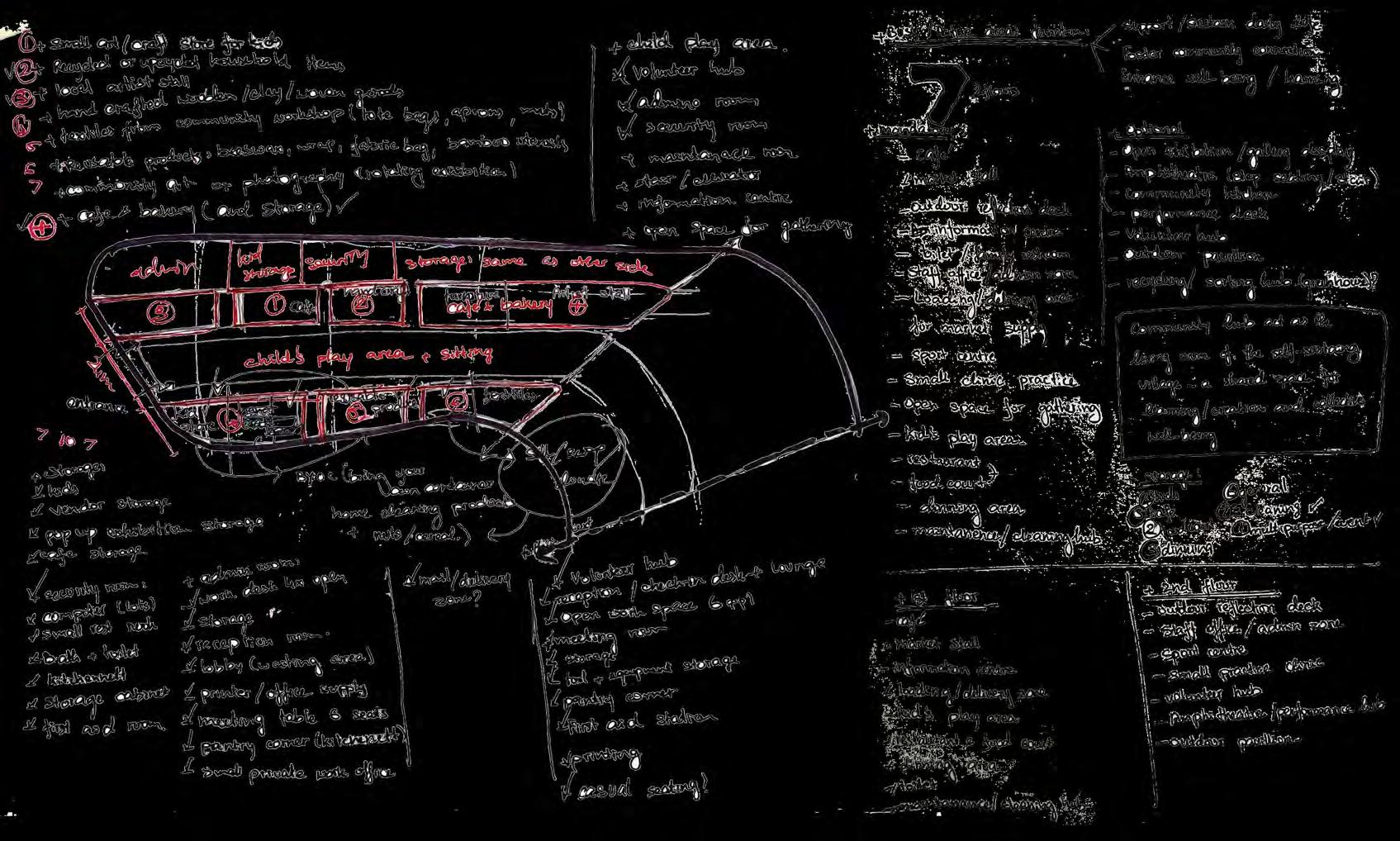

The community hub features seven types of market stalls, each designed to support local livelihoods and promote self-sufficiency within the community. These include stalls for fresh and local produce, artisan and homemade goods, garden and wellness products, local crafts and circular economy items, prepared food and refreshments, educational and interactive displays, and additional multifunctional uses. Each stall type is thoughtfully designed to provide job opportunities for residents and to partially source produce from the greenhouse, reinforcing the interconnected systems within the village. The stalls are strategically distributed throughout the hub floor plan to encourage accessibility, interaction, and community engagement.

grocery store layout and diagram

Layout design for stall display/ dinning area/ and storage and movement footprint

ĊTAÄÄ ANǍ ČĎÁÆĄĂ TĆĄÆÂT

ĴĹ ÂÇĎĄČMÂNT ANǍ ĊTĆĈAÀÂ ĈĆĆM

7Ĺ MÂÂTĄNÀ ĈĆĆM

ǨĹ ĆČÂN ĊČAĂÂ ÐĆĈÃĄNÀ AĈÂA

ĶĹ ĐĆÆĎNTÂÂĈ ĀĎÁ

ĪÌĹ ČANTĈÉ ĚĆNÂ

ĪĪĹ ČĈĄNTÂĈ ANǍ ĆÄÄĄĂÂ ĊĎČČÆÉ ĈĆĆM

ĪĮĹ MANAÀÂĈ ĆÄÄĄĂÂ

ĪĨĹ MÂÂTĄNÀ AĈÂA

Ī4Ĺ ÐĆĈÃ AĈÂA

Ī5Ĺ AǍMĄN ĚĆNÂ

ĪĴĹ ĊÂĂĎĈĄTÉ ĈÂĊTĄNÀ AĈÂA

Ī7Ĺ ĊÂĂĎĈĄTÉ ÆĆĂÃÂĈ ANǍ ÁATĀĈĆĆM

ĪǨĹ ĊÂĂĎĈĄTÉ ĈĆĆM

ĪĶĹ ÂÆÂĐATĆĈ

ĮÌĹ AĂĂÂĊĊĄÁÆÂ TĆĄÆÂT ĮĪĹ MAÆÂ TĆĄÆÂT

ĨÌĹ MAĈÃÂT ĊTAÆÆ ĊTĆĈAÀÂ ANǍ ÆĆAǍĄNÀĻǍĈĆČ ĆÄÄ ĚĆNÂ

ĨĪĹ ĊMAÆÆ ÀĈĆĂÂĈÉ ĊTĆĈÂ

ĨĮĹ ǍĄNNĄNÀ ĀAÆÆ

ĨĨĹ ÆĄÀĀT MÂAÆ ĊTĆĈÂ

Ĩ4Ĺ ÆĎNĂĀ ÁĆX ĊTĆĈÂ

Ĩ5Ĺ ÅĎĄĂÂ ÁAĈ

ĨĴĹ ÁĆTANĄĊT ĊTĆĈÂ

Ĩ7Ĺ NATĎAÆ ĊĆAČĊĻ ĂANǍÆÂĻ ÂĊĊÂNTĄAÆ ĆĄÆĊ ĊTĆĈÂ

ĨǨĹ ĀÂĈÁAÆĻ ĊÃĄN ĂAĈÂĻ AĈĆMATĀÂĈAČÉ ČĈĆǍĎĂTĊ ĨĶĹ ĄNÄĆĈMATĄĆN ĂÂNTĈÂĻ ÀĈÂÂNĀĆĎĊÂ ÂǍĎĂATĄĆN ĊTAÆÆ

4ÌĹ ÆĆĂAÆ ǍAĄĈÉ ČĈĆǍĎĂÂ (ǍÂÆĄ)

4ĪĹ ÁAÃÂĈÉ ĊTĆĈÂ

4ĮĹ ĀANǍMAǍÂ ÅAMĻ ČĄĂÃÆÂĻ ĀĆNÂÉĻ ĊAĎĂÂ ĊTĆĈÂ

4ĨĹ ČÆANTŁÁAĊÂǍ ĊNAĂÃĻ ǍĈĄÂǍ ÄĈĎĄT ĊTĆĈÂ

44Ĺ ĀÂĈÁAÆ TÂAĻ ĄNÄĎĊÂǍ ĆĄÆ ĊTĆĈÂ

45Ĺ ĆČÂN ĀAÆÆ AĈÂA

4ĴĹ ĊTAĄĈ ANǍ ÂĊĂAÆATĆĈ

47Ĺ TÂXTĄÆÂĊ (TĆTÂ ÁAÀĊĻ AČĈĆNĊĻ MATĊ) ĊTĆĈÂ

4ǨĹ ĂĀĄÆǍĈÂN ČÆAÉÀĈĆĎNǍ AĈÂA

4ĶĹ ÆĆĂAÆ AĈTĄĊT ČĆČ ĎČ ĊTAÆÆ

5ÌĹ ĈÂĂÉĂÆÂǍĻ ĎČĂÉĂÆÂǍ ĀĆĎĊÂĀĆÆǍ ĄTÂMĊ

5ĪĹ ÃĄǍĊ AĈT ANǍ ĂĈAÄT ĊTĆĈÂ

5ĮĹ ĀANǍĂĈAÄTÂǍ ÀĆĆǍĊ

5ĨĹ ĊÂÆÆĻĊÐAČĻǍĆNATÂ ĊTĆĈÂ

54Ĺ ÁÉĆĂ (ÁĈĄNÀ ÉĆĎĈ ĆÐN ĂĆNTAĄNÂĈ) ĊTĆĈÂ

55Ĺ ĊĄTTĄNÀ AĈÂA

5ĴĹ ĂAÄÂ ANǍ ĈÂĊTAĎĈANT

57Ĺ ĈÂĎĊAÁÆÂ ĄTÂMĊ ĊTĆĈÂ

ĮĶĹ ǍĄNNĄNÀ AĈÂA ĊTĆĈAÀÂ

5ǨĹ ÁĆĆÃĊTĆĈÂ

ĊTĆĈAÀÂ ĪÌĹ ÆAÁ ĈĆĆM (ÁÆĆĆǍ TÂĊT)

ĪĪĹ ĎNĄĊÂX

Į4Ĺ ĂĆNĊĎÆTATĄĆN ĈĆĆM

Į5Ĺ ĂĆNĊĎÆTATĄĆN ĈĆĆM Į

ĮĴĹ ĊMAÆÆ ČĈĆĂÂǍĎĈÂ ĈĆĆM

Į7Ĺ ČĀAĈMAĂÉ ĈĆĆM

ĮǨĹ ÐAĄTĄNÀ AĈÂA

ĮĶĹ ĊMAÆÆ ĂÆĄNĄĂĻ ČĈAĂTĄĂÂ

ĨÌĹ ĈÂĂÂČĊTĄĆNĄĊT AĈÂA (ĂÆĄNĄĂ)

ĨĪĹ ĂĆNĊĎÆTATĄĆN ĈĆĆM Ĩ

ĨĮĹ ĂĆNĊĎÆTATĄĆN ĈĆĆM 4

ĨĨĹ ĂĆNĊĎÆTATĄĆNĻ ÂÇĎĄČMÂNT ĊTĆĈAÀÂ ĈĆĆM

Ĩ4Ĺ ĊČĆĈT ANǍ ÄĄTNÂĊĊ ĂÂNTĈÂ

Ĩ5Ĺ ĈÂĂÂČTĄĆNĄĊT AĈÂA (ÀÉM)

ĨĴĹ ÄĈÂÂ ÐÂĄÀĀTĊ ĊÂĂTĄĆN

Ĩ7Ĺ ĂAĈǍĄĆ AĈÂA

ĨǨĹ ÉĆÀAĻĊTĈÂTĂĀĄNÀ AĈÂA

ĨĶĹ ČĄÆATÂĊ ĈĆĆM

4ÌĹ ĊAĎNA ĈĆĆM

4ĪĹ MAÆÂ ĊĀĆÐÂĈ ANǍ TĆĄÆÂT AĈÂA

4ĮĹ ÄÂMAÆÂ ĊĀĆÐÂĈ ANǍ TĆĄÆÂT AĈÂA

4ĨĹ ĊTAÄÄ ÆĆĂÃÂĈ ANǍ ÁATĀĈĆĆM

44Ĺ ĊTAÄÄ ÁĈÂAÃĈĆĆM (ÀÉM)

45Ĺ TĈAĄNÂĈĻ ĊTAÄÄ ĈĆĆM

4ĴĹ ĂĆNĊĎÆTATĄĆN ĈĆĆM (ÀÉM)

NATURAL SOAPS/ CANDLE/ ESSENTIAL OILS

- Heritage Trails and Walks. (2019). Vic.gov.au. https://www.maribyrnong.vic.gov.au/Discover-Maribyrnong/Our-history-and-heritage/Heritage-Trails-and-Walks

- ACT, R. (2025, April 3). Department of Defence. Defence. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/locations-property/asset-disposals/property-disposals/defence-site-maribyrnong

- David, R. (2023, July 27). DERT seeking Expressions of Interest for Defence Site Maribyrnong. Liberty Industrial. https://libertyindustrial.com/ dert-seeking-expressions-of-interest-for-defence-site-maribyrnong/

- jimjin. (2018, October 24). New suburb nearer on contaminated Maribyrnong Defence site. Maribyrnong & Hobsons Bay. https://maribyrnonghobsonsbay.starweekly.com.au/news/new-suburb-nearer-contaminated-maribyrnong-defence-site/

- Lucas, C. (2017, June 2). Chinese developers unveil $2.5 billion plan for Maribyrnong defence land. The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/chinese-developers-unveil-25-billion-plan-for-maribyrnong-defence-land-20170602-gwj8vy.html - Mulwala Homestead Precinct. (2024, June 3). GML. http://gml.com.au/projects/mulwala-homestead-precinct/

- Whinnett, E. (2015, November 26). Delay over munitions factory site blasted. Heraldsun; Herald Sun. https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/delay-over-munitions-factory-site-deal-drags-on-for-six-years/news-story/e75db5bd215c26535023084a7860119f