At 1.11 a.m. the East Berlin radio service interrupted their “Night-time Melodies” for a special announcement:

“The governments of the States of the Warsaw Pact appeal to the parliament and government of the GDR and suggest that they ensure that the subversion against the countries of the Socialist Bloc is effectively barred and a reliable guard is set up around the whole area of West Berlin.”

The significance of this pretentious declaration was quite clear: West Berlin was to be sealed off. But in the West, who on earth listened to SED (East German) radio…

It was Sunday 13 August 1961. At 1.05 a.m. the lights suddenly went out at the Brandenburg Gate. Armed GDR border guards and members of combat groups marched up and positioned themselves at the inner city demarcation line. In the glare of the headlights of military vehicles they ripped up the paving stones and erected barbed wire barriers. The scene was the same at many points in and around Berlin: Border Police, armoured vehicles, barbed wire, concrete posts.

At this point the West was completely unaware of the dramatic developments taking place at the sector borders.

Chief Superintendent Hermann Beck was preparing himself for routine duty at the headquarters of the West Berlin Police on Tempelhofer Damm; there had been no special incidents since the beginning of the shift at 5.30 p.m. “Person seeking help at Zoo station”, “Drunken teenager at Wittenbergplatz”. Just the usual sort of thing on a Saturday night in Berlin. At about 2.00 a.m. a report came in which at first Beck didn’t know how to deal with: “13.8.1961, 01.54. Spandau police station report that the S-Bahn train from Staaken travelling to Berlin was directed to return to the Soviet Zone. The passengers had to get out and their fares were refunded.” Just one minute later a further call was received from Wedding police station: “At 01.55 S-Bahn trains in both directions were halted at Gesundbrunnen Station.” Then further calls followed, one after another; all S-Bahn trains were also stopped at Schönholz, Wannsee and Stahnsdorf stations.

The reports, coming in quick succession from 2.20 a.m. onwards, became increasingly threatening. “15 military trucks with Vopos (East Berlin police) at Oberbaumbrücke”.

“Armoured reconnaissance vehicles on Sonnenallee”. “Hundreds of Vopos and Border Police with machine guns at the Brandenburg Gate.” Beck was almost in a state of panic. Was it the attack on Berlin which everyone feared? Should he fetch the sealed envelope from the safe and set in motion the secret plan for the defence of West Berlin which would throw the capital cities of the West into turmoil?

For a quarter of an hour Beck and his superior wrestled with a decision which carried serious consequences. When the telephone reports up to 2.45 a.m. continued to speak of “concentrations of troops”, and “blockades” but not of “advances on to West Berlin territory”, they decided to give the “minor alarm” for the time being.

During the night a total of 13,000 West Berlin police were woken from their sleep and called in. A former police officer commented that “at first we thought they were going to overrun us and march into West Berlin, but they remained precisely within one centimetre inside the sector boundary.”1

It was an operation planned and executed by the General Staff, which was led by an SED official hardly known in the West, Erich Honecker. The 49 year old General Secretary of the Defence Committee was at the nerve centre of operations throughout the night. He worked from the Police Headquarters at Alexanderplatz where he received reports by telephone and courier on the progress of the blockade measures and issued orders to the Commanders. A total of 10,500 operational units of the Peoples’ and Border Police and members

of fighting groups were directly involved in sealing off West Berlin that night. In addition there were several hundred Stasi workers as well as two motorised armoured divisions of the NVA (altogether about 8,000 men) who, however, were ordered to approach the border only as far as 1,000 metres in a “second back-up formation”. Everyone went according to plan. Only 12 of the 81 street crossing points remained passable, the rest were sealed off with barbed wire. The S-Bahn trains running between the two parts of Berlin, as well as into the surrounding area, were stopped.

On 23rd August the number of border crossing points was reduced to seven: Friedrichstraße, Bornholmer Straße, Chaussee straße, Invalidenstraße, Heinrich-Heine-Straße, Oberbaumbrücke, Sonnenalleee and Friedrichstraße/Zimmerstraße (Checkpoint Charlie).

Walter Ulbricht had achieved his political aim. The escape route across the Berlin sector border, which had been used over many years by more than 1.6 million East German citizens fleeing into the West, had been blocked. It had taken the SED leader a great deal of effort over the past months and days to convince the Soviet Party and State leader Khrushchev and the other Warsaw pact leaders that sealing off West Berlin was the only way to stop the flood of refugees and prevent the GDR from “bleeding to death”.

On 12th August 1961 at about 4 p.m.

Ulbricht signed the necessary orders and the operation swung into action.

It wasn’t until 12 th August when they were instructed by the Minister for Defence, Heinz Hoffmann, that the NVA commanders were brought into the plan. At 8 p.m. an order was issued to them to “support the armed forces of the Ministry for the Interior in securing the Sector borders in and around West Berlin. The troops of the National Volksarmee in the ordered sections, together with the forces of the 1 st and 8th motorised armoured divisions, are to form a second back-up formation at a distance of about 1,000 metres from the border.”2

During the night the Soviet troops around Berlin were put on alarm level 1, although throughout the whole operation they were not supposed to put in an appearance if at all possible.

During the preparations for closing the borders, Ulbricht and Honecker bypassed almost all the leading organs of the Party and State. Even the leaders of the so-called Block Parties knew nothing on the evening of 12th August when they were invited by Ulbricht to come for a meal at his summer residence in Groß-Dölln, 75 kilometres north of Berlin. It wasn’t

intention

until about 10 p.m. that the amazed guests were informed that the sector borders with West Berlin were about to be closed.

It was a warm August night after a hot Saturday. At 2.30 a.m. Allan Lightner, the Senior Representative of the US government in Berlin, received the information about the closing of the sector border – and went back to sleep. He was to be woken as soon as there were any further developments. At 3.30 a.m. the CIA employee, John Kenney, heard that the border was closed via a radio announcement on RIAS (Radio in American Sector, ed.). Shortly afterwards, when he walked into the CIA Headquarters in Dahlem, he expected frenzied activity. Yet the whole building was quiet, with no sign of any alert.

Meanwhile Richard Smyser, an employee of the US-Mission, had received the order from the Duty Officer to “take a look round” in Berlin. At 3.30 a.m. he arrived at Potsdamer Platz. He demanded information about what was going on from the Border Police stationed there – and also his right to go across. After a short exchange of words the barbed wire was indeed pushed aside so that Smyser could drive through in his car. As dawn was breaking on the streets of East Berlin he saw military vehicles, armoured personnel carriers and trucks carrying barbed wire and concrete posts; but he didn’t see a single Soviet tank.

In Washington the first news from Berlin arrived shortly after 5 a.m. MEZ (about midnight local time). John Ausland, an employee of the Berlin section of the US Foreign Ministry, was the first to be informed. He listened to the telephone report and then went back to bed. Four hours later he received a CIA telegram from Berlin which contained the code word instructing that the President should be informed immediately. At this point Ausland hurried into the State Department and urgently looked through the documents for the plans for this particular case. After a lengthy search he at last found a file with the corresponding title, “Border Closure”. It was empty.

At 12.30 p.m. local time President John F. Kennedy was advised of the situation on board his yacht. At first he was indignant at not having being told about the events in Berlin earlier but quickly calmed down. Together with Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, he put together a press release and then said, “I’m going sailing now. Go to your baseball game as you planned.” The press release ran, “It is clear to whole world that sealing off of East Berlin is a defeat for the communist system. The East German Ulbricht regime is responsible for shutting in its own people in front of the eyes of the whole world.”

Within his circle of close advisers Kennedy made no secret of his relief about developments. “Khrushchev would not have had a wall built if he really wanted to take West Berlin. If he were to occupy the whole city he wouldn’t need a wall … . It’s not a particularly pleasant solution but a wall is a damned sight better than a war.”3 Furthermore the “three essentials” of the American policy in Berlin had not been affected:

2. Free access routes;

1. The presence of the Western Allies in Berlin;

3. The right of self-determination for the West Berliners. There was, therefore, little cause for Washington to enter into vigorous negotiations.

In West Berlin, however, things were viewed completely differently on 13th August. The Governing Mayor, Willy Brandt, was not in the city but on a special election campaign train

travelling from Nürnberg to Hannover. Brandt was the SPD candidate for Federal Chancellor in the forthcoming general election in September 1961. He was woken up at 4.30 a.m. by Heinrich Albertz, the head of the Berlin Chancellery, and took the first plane back to Berlin.

“I was greeted by Albertz and Police President Stumm at Tempelhof Airport. We were driven to Potsdamer Platz and up to the Brandenburg Gate and saw the same scene everywhere: construction workers, obstacles, concrete posts, barbed wire and East German military personnel. At Schöneberg Town Hall I received reports that Soviet tanks were encircling the city on standby and that Walter Ulbricht had already been seen congratulating the units of construction workers … .” 4 During the course of the morning Brandt experienced feelings

of rage and fury, but also of concern over a possible escalation of the situation.

It was still morning when Brandt drove out to the leafy suburb of Dahlem to meet with the Allied Commandants. He asked insistently what action the Western Allies had in mind and at first he was met with an embarrassed silence. With mounting anger the Mayor demanded that at least a strong protest should be lodged in Moscow and added, “At the very least send patrols to the border between East and West Berlin to counter the feelings of insecurity and to show the West Berliners that they are not in any danger!” The three Allied Commandants agreed to this at any rate, but otherwise they could seen no reason for any activity, especially as they were waiting for instructions from their respective capital cities.

A sense of being left in the lurch spread among the population of West Berlin. “The West is doing nothing,” ran the headline of the Bild-Zeitung on 16th August and this expressed the feelings of half the city. Faced with this situation Brandt decided on an unusual course of action: circumventing the US Allied Commandant, he sent a telegram to US President Ken-

Employing a directness which was hardly diplomatic, the Berlin Mayor demanded action from the Western powers. “1. Lack of action and a purely defensive stance could cause a crisis of confidence in the Western powers. 2. Lack of action and a purely defensive stance could lead to over-confidence within the East Berlin regime…”

On the afternoon of 16th August 300,000 West Berliners gathered in front of the Schöneberg Town Hall to demon-

strate. The atmosphere was heated. The placards read: “We need protection. Where are the protecting powers?”; “Enough of protests. Now let actions speak”; “Deceived by the West”.

Brandt was faced with a difficult task. On the one hand he had to address the peoples’ feelings but on the other hand he had to prevent a heightening of the situation and any rash action at the barricades.

He struck the right tone in his speech: “The Soviet Union has let their guard-dog Ulbricht off his lead and allowed him to march into the Eastern Sector of this city … The protests of the three Allied Commandants were right but this is not end of the matter!” He appealed urgently to the civil and military leaders of the GDR: “Don’t debase yourselves! Show humanity wherever possible and above all, don’t shoot at your own

people! This city of Berlin wants peace but is not going to capitulate. …”

In the meantime in Washington alarming reports were coming in from Berlin. A State Department official telegraphed: “There is a danger that that fragile thing called hope could be destroyed.”5 In this situation Kennedy decided to take two symbolic actions. He sent 1,500 GIs down the motorway from Helmstedt to strengthen the US garrison in Berlin, where they were given a tumultuous welcome by the population. He also sent his Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson to the beleaguered city. When Johnson arrived at Tempelhof Airport on 19th August he was overwhelmed by the triumphal reception. Hundreds of thousands of people lined the route of his journey through the Western sectors.

While pictures of the anger and protests of the West Berliners were flashed round the world, the situation in the Soviet Sector hardly reached the outside world. “Trams and olive-green military trucks were driving past full of uniformed personnel with iron expressions,” wrote the author Klaus Schlesinger recalling the events of 13th August “Everywhere it was the same picture, chains of armed combat groups and on both sides, people. I … ran instinctively along the streets near the border … there were people everywhere in front of crumbling façades, shaking their heads and waving their arms about passionately.”6

The GDR press printed nothing but reports of triumph and messages of solidarity. The “Neue Deutschland” on 14th August ran quotes from “workers of the GDR and its capital”

such as: “To Walter Ulbricht young railway workers say: Let’s get out of the danger area of West Berlin!” – “We can breathe a sigh of relief” – “Woe betide anyone who gets pushes their luck!” Today, access to the secret reports of the SED district leaders gives a true insight into the atmosphere among the East Berlin population immediately after the closing of the border. These “information reports”7 show a surprisingly unvarnished picture of the reactions within the boroughs. The reports, which were analysed centrally and passed on to Ulbricht, make it clear to the SED leadership exactly what many people in East Berlin really thought of the “anti-fascist protective Wall”.

From Wollankstraße in the borough of Pankow at 10.30 a.m. on the morning of 13th August an anonymous informer

reported: “A woman screamed out, “Let’s go into the middle of the street and force our way through the barrier. We are all Germans, we want to go over to our brothers.” Other young people shouted “It’s a disgrace that you are prepared to guard this border and not let us across. You are not Germans.”

A more subdued report from Weißensee, also made on 13th August runs: “Although relatively scattered, there is a string of open declarations of support,” and, “there is a large number of negative statements, which in essence express the following content: – deepening of the rift by us (SED, ed.), – limitation of freedom, – this isn’t a democracy, and in a number of the conversations the fear of war is a repeated theme.” In the initial stages of criticism the regime took vigorous action in many

places: “On Schönhauser Allee Station a troublemaker was arrested who said, among other things: “There is no democracy in this country”, and that he would soon find a gap where he could slip through to the other side.”

“Near the East Berlin Zoo, on tram number 69E, trouble was stirred up by a BVG employee: “They must be frightened over there, 300 tanks have been brought in and the tracks have been pulled up.” When a comrade squared up to him he started begging for bananas for his children and so on … The comrade was told how to deal with such troublemakers in future.” On 16th August the “section for organisation and personnel” of the SED District Headquarters in Weißensee reported that: “A Frau Dienzloff, … Weißensee, at a Party meeting of the National Front said: ‘Now we are sitting behind barbed wire and they call that freedom.’”

As the “information reports” show, there were many different forms of protest: “In the PKB Kohle a member of the combat group was arrested because he had criticised the Party and the government and had refused to obey orders. At some points there were “coinciding” work breaks, exactly at the same time as the DGB in West Berlin was calling for a so-called protest strike. In the VEB thermal power station the belt on a machine was changed over at that time … with the result that the machines broke down. In the VEB dairy a machine was repaired at 11 a.m. and thereby caused … a shut-down. During the lunch hour on 15th August the following slogan was painted on to the works’ wall at OWL, Treptow: “Berlin is now a prison.” The perpetrators have not been traced yet.”

In these critical days the SED sent several dozen “agitators” on to the street to interfere in discussions and disperse the larger gatherings. They did not have an easy task.

There were individual cases of open disobedience: “Comrade Danis from the Drolhagen brigade has refused to build the sector border. He was isolated from his brigade immediately and later his papers (SED Party book etc.) were taken away from him.” Occasionally, a few policemen and border guards also protested openly and refused to obey orders. For example, on 15th August a police officer did not turn up for duty. “Although during the ensuing discussion he was advised of his politically incorrect behaviour, he reacted by giving up his Party papers and his record of service. The necessary measures were taken.” By the end of August, in East Berlin alone 2,192 people were arrested and 691 were given a prison sentence. Until about October 1961 the SED leadership had largely succeeded in silencing criticism and protest by selective use of the police and the Stasi.

When the borders were shut, numerous East Berliners and GDR citizens began to panic. “It’s now or never”, many of them said to themselves and made a spontaneous decision to flee. The days and weeks which followed 13th August turned into a macabre contest between fugitives and Border Troops who were trying to make the barbed wire and the wall more and more impenetrable. Those trying to escape, jumped over the barbed wire, crept under fences, broke through the border in vehicles or swam across the Spree and the Teltow Canal. By the middle of September more than 600 people, among them whole families with children, had managed to get to West Berlin using these methods.

There were particularly spectacular escape scenes in Bernauer Straße where the façades of several of the houses formed the sector boundary. Crowds of West Berliners had gathered there and watched as many East Berliners used these buildings to escape.

They jumped out of the windows, abseiled off or dropped into the blankets held out by the West Berlin Fire Brigade. Several dramatic situations developed, for example on 24th September 1961, when the police and Stasi tried to pull back a 77 year old woman who had already climbed out of the window. On 22nd August 1961, 59 year old Ida Siekmann jumped out of the third floor of a building on Bernauer Straße and missed the mattress which was being held out and injured herself fatally. On 19th August a 57 year old man suffered terrible wounds from abseiling off and died on 17 th September.

These fugitives were the first victims of the Berlin Wall.

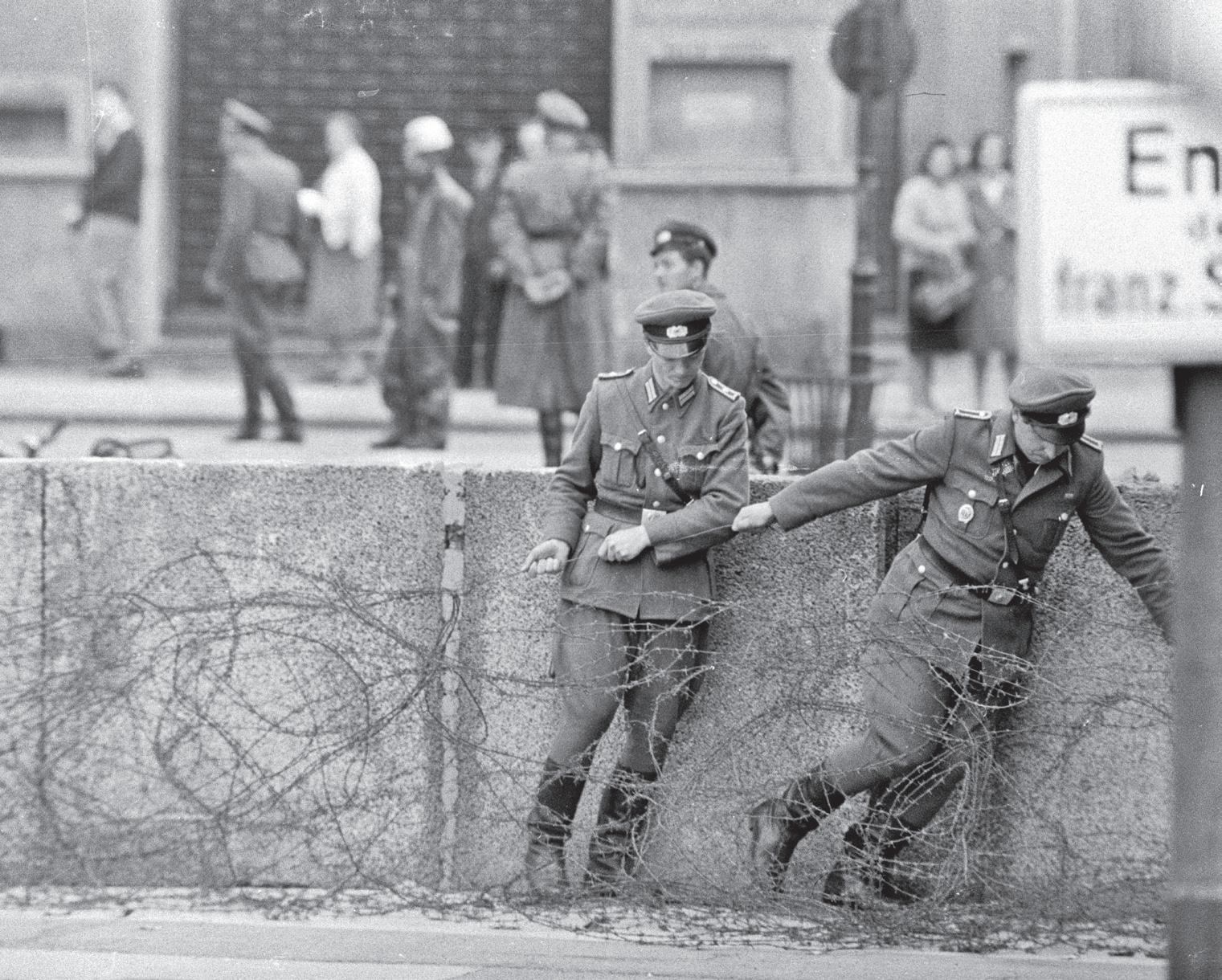

As a counter-measure, on 24th September the Peoples’ Police ordered the 2,000 inhabitants of Bernauer Straße to vacate their homes within four days. The doorways and windows were bricked up. On 15th August journalists in Bernauer Straße were witnesses to a sensational escape. One of the border guards was behaving strangely. He had walked up to the barbed wire barrier several times and pressed it down a bit with his hand. The guard got nearer to the barbed wire, a few minutes passed and then it all happened in a flash. He took a run-up and jumped over the barbed wire, dropped his sub-machine gun whilst he was still in the air and then disappeared in a West Berlin police van. The picture of the first GDR border guard to escape to the West was flashed around the world.

A total of 18,000 men took part in the building and supervision of the border in August 1961 (NVA, Peoples’ Police, members of combat groups, Border Police, Transport Police). They

did not know what their task was until they arrived to go into action at the first they had to cope with physical and psychological demands of the job on their own. The heads of operations around Honecker became increasingly worried about the motivation and psychological state of the border guards. There were more and more cases of desertion and moral was not at its highest among the border guards. On 18th August it was reported that the “party political work among the security forces” was still “unsatisfactory”8 . The reliable propagandist, Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler was posted in immediately to strengthen the shaky ideological attitude of the troops. But even that did not prevent the numbers of deserters from growing.

In the first six weeks after the closing of the border, 85 GDR Border Police fled from East to West Berlin. The high numbers of deserters led to an intensification of the political and ideological training of the Border Troops and a strengthening of controls and sanctions in the Border Regiments. In future, patrols of two to three men were used to ensure mutual checks.

The commands and duty regulations in the months that followed all used clear language. The troops were to shoot “ruthlessly” at “border violators”. Following a meeting held on 22nd August 1961 the instruction went out from the SED leadership, “that anyone who violates the laws of our German Democratic Republic will even – if necessary – be brought to order by using weapons.”9 Two days later the first fatal shots were fired.

On the afternoon of 24th August 1961 the 24 year old tailor Günter Litfin ran towards the border under the rail tracks at Friedrichstraße Station. A sentry in the GDR Transport Police (Trapo) ordered him to stop and gave two warning shots. Litfin jumped into the water of the Humboldt Port in order to swim across to West Berlin. The statement given by the leader of the Trapo section depicts briefly and coldly what happened next: “After a machine gun salvo of three shots had been fired into the water several metres in front of the border violator and the latter did not turn back, there were two further carefully aimed shots and the border violator went under.”10 Two hours later the body was recovered from the Spree by Vopos. Günter Litfin was the first refugee who was shot and killed at the Berlin Wall.

Escape attempts – termed “border breakthroughs” by the Border Troops – became increasingly more difficult and dangerous. On 29th August a man was shot dead trying to swim

down the Teltow Canal. On 13th October a refugee was killed on the Potsdam-Babelsberg border and West Berlin by members of the Transport Police. By the end of October 1961 15 people had met their death on the border with West Berlin. Each escape attempt was carefully registered by the GDR Border Troops. The means of transport used, for example cars or boats, were recorded as well as the circumstances of the escape. This information was assessed by the military commanders and used as the basis for planning further border fortifications. Although the organisation of the border regime and the strengthening of the border itself progressed rapidly, the troops recorded 216 escape attempts involving 417 people up to 18th September alone. At a meeting of the “Central Staff” on 20th September 1961, Honecker gave a warning in the name

of the Politbüro that “the engineering measures to ensure the security of the State Border in Berlin are still inadequate”. He instructed the commanders of the Border Troops to take more vigorous action in future. “All breakthroughs must be made impossible.”11 According to the minutes of the Politbüro meeting on 22nd August 1961, all escape attempts should be stopped, even by taking direct aim if there is no alternative method of making an arrest. “Firearms are to be used against traitors and border violators … An observation and firing area is to be established in the Border Zone …”

For the month of October 1961, however, the border troop statistics list a further 85 “border breakthroughs” (“49 minor incidents; 36 serious incidents”), in which 151 people (carefully separated in the files according to sex and age) succeeded in fleeing to West Berlin. Under the heading “direction” there were two columns: “GDR – West” and “West –GDR”. The latter, it has to be said, remained empty. The most frequent methods of escape were recorded in the statistics as “cutting” or “crawling under” the wire and “climbing over the Wall”. Unquestionably, the duty of the border guards was to prevent “border breakthroughs” and if necessary, to shoot to kill. However, the Party and the military wanted this to be the last resort; any shooting at the Wall and the inner German border should be avoided wherever possible, not least with a view to the damage that it could cause the international reputation of the GDR. The border security system was therefore constructed to be staggered more deeply and to be more close-meshed so that escapees couldn’t even manage to get near the border. In May 1962 a spectacular incident at the Wall turned into a classic shoot-out between GDR border guards and West German policemen. A boy from Thüringen, who was only just 15 years old, Wilfred T., jumped into the

Spandau Canal at about 5.45 p.m. in order to swim across to West Berlin.

GDR guards opened fire. In spite of several wounds Wilfrid T: was able to reach the other side where a transport worker came to his aid. However, the GDR soldiers kept shooting at the escapee whereupon two West Berlin policemen returned fire. During the heavy gunfire the 21-year old GDR border guard, Peter Göring, was fatally hit. The GDR soldiers shot a total of 121 rounds.

In August 1962, a year after the border had been closed, the agonising death of Peter Fechter demonstrated the monstrosity of the Wall to the whole world. Together with a workmate the 18-year old apprentice builder wanted to escape to the West in Zimmerstraße, very close to Checkpoint Charlie.

The death of Peter Fechter, who was shot during an escape attempt in August 1962 and bled to death on the Wall strip, triggered a wave of protest.

They had both already climbed over the first fence when they were noticed by the border guards, who shouted at them and then opened fire. A total of 21 shots were fired. The friend was able to climb over the barriers but Peter Fechter had been hit in the stomach and in the back and lay under the Wall on the East Berlin side. The GDR soldiers made no effort to help Fechter, who was bleeding to death. He was shouting for help but the West Berlin Police could not get to him because he was lying on East Berlin territory. All they were able to do was to throw him packs of bandages. The American soldiers on duty at Checkpoint Charlie were also afraid to step on to East Berlin territory in order to help the wounded man. Hundreds of people gathered on the West American soldiers cover the ‘Checkpoint Charlie’ border crossing point in Friedrichstraße with an anti-tank weapon.

Berlin side of the Wall and shouted in helpless anger and outrage at the GDR guards, demanding them do something to