John Muir & Ancient Oaks

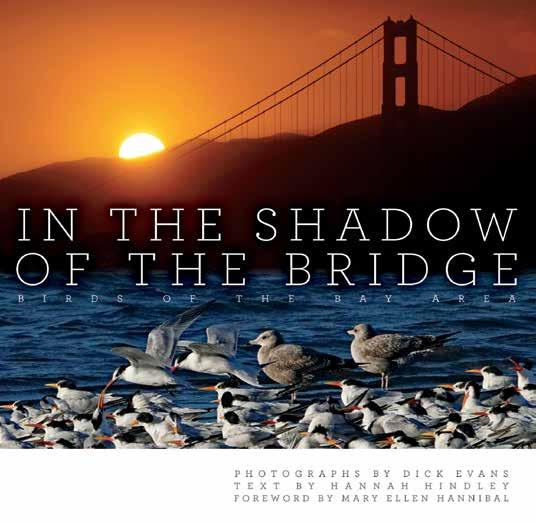

In the Shadow of the Bridge is a spectacular book, capturing the dance of light and color that can only be seen on the feathers of a bird.

John P Dumbacher (Jack), Chief Ornithologist at California Academy of Sciences

Anchored by Hannah Hindley's liquid and radiant prose, the portfolio of Dick Evans attains something transcendent. His photography isn't just about birds, it is about grace in evolution, its diversity, and its poetry.

Obi Kaufmann, Author of The California Field Atlas Series

On the underside of docks everywhere grows a thimble-size, feathery-armed invasive nuisance of an animal with a horror-movie name: BYOO-gyoo-lah. Its symbiotic bacteria are pumping out a chemical that researchers suspect may be a wonder drug.

By Eric Simons

One in three Bay Area residents is from another country, and many cultivate plants to create abundance for bugs, birds, and their own families. What they choose to plant, whether food or medicine, California native or special plant from afar, results in an evolved sense of home—a blending of ecologies.

By Jillian Magtoto

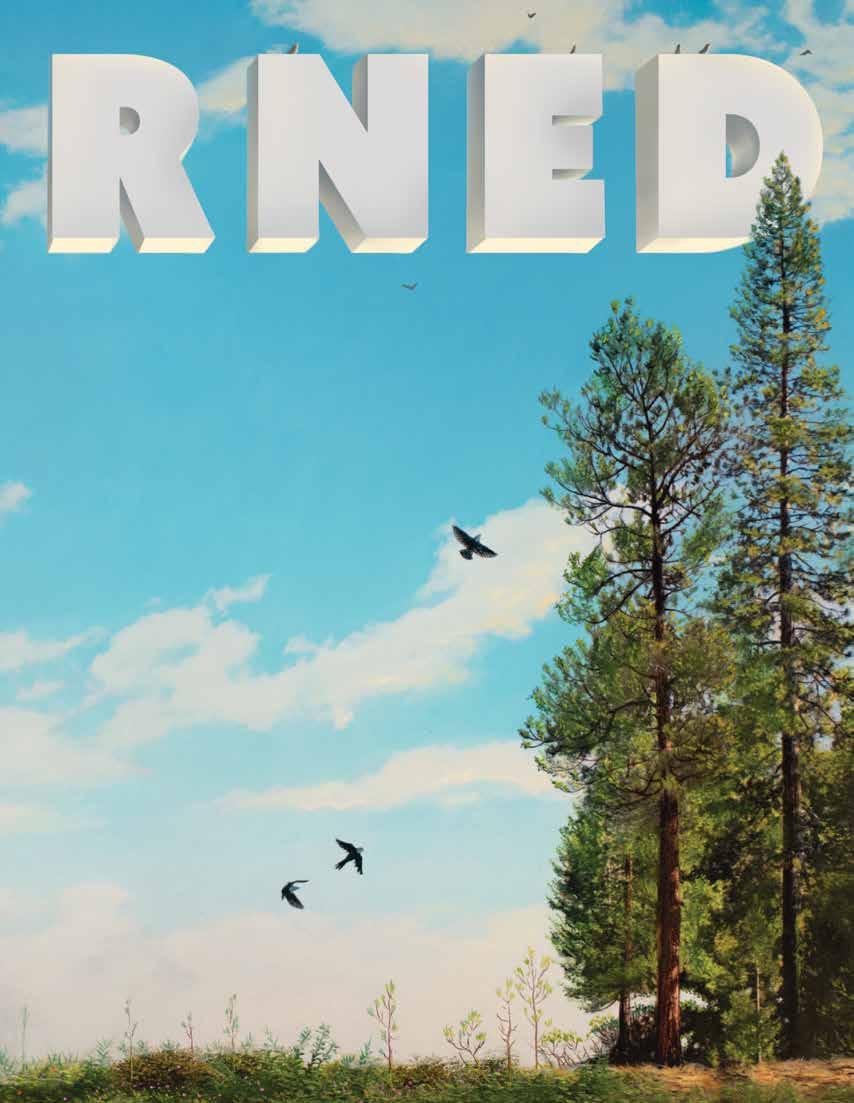

After the Dixie Fire, the U.S. Forest Service was granted a startling amount of money to make the Plumas National Forest and its communities, in northeastern California, resilient to future wildfires. Even $274 million isn’t enough to do the job, our investigation with The Plumas Sun finds.

By Jane Braxton Little

36 d ouble Cross t rail

Wending through San Francisco from the Pacific Ocean to the San Francisco Bay, this 15-mile trail has it all: natural lakes, formidable hills, jaw-dropping views, and hidden gardens. Amid the urban landscape, nature emerges.

By helen J. doyle

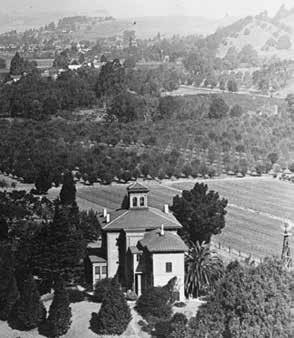

40 alhambra hills

A new park in Martinez, part of which John Muir once owned, boasts a head-clearing ridgeline, a glen of ancient oak trees, and possibly rare Alameda whipsnakes. Years ago it was slated for housing, and local residents fought to protect it.

By aleta george

42 C otoni- C oast dairies

The first nine miles of trail have at last opened in this sweeping new national monument north of Santa Cruz. Throughout the landscape, you’ll find reminders of the Cotoni people, like the rare patches of native coastal prairie where they gathered food.

By sierra garcia

p. 28

Tim O’Brien is an award-winning illustrator whose work has appeared on the cover of national and international magazines since 1987, and he has created covers for most major book publishers, including the Hunger Games series. Tim is the second-longest-term president of the Society of Illustrators, serving from 2015 to 2022, and was inducted into the Illustrator Hall of Fame in 2025.

p. 22 Jillian Magtoto is a climate change and environmental reporter at the Savannah Morning News and formerly a 2024–2025 editorial fellow with Bay Nature. She graduated from the Columbia School of Journalism and UC Berkeley with majors in rhetoric and ecosystems management.

p. 19 Eric Simons is a former digital editor at Bay Nature. He has spent many joyful hours on his belly at Jack London Square with his daughter, peering into the water at the intriguing world of dock fouling creatures. He is still happily looking for a Bugula neritina. He is author of The Secret Lives of Sports Fans and Darwin Slept Here , and is coauthor, with Tessa Hill, of At Every Depth: Our Growing Knowledge of the Changing Oceans

p. 22

Amir Aziz , a 2025–2026 Bay Nature editorial fellow, is a documentary photographer and filmmaker whose visual work explores culture, community, and the environments they shape. Originally from Oakland, he has documented community stories across the Bay Area, France, and Hong Kong, often finding connections to his hometown along the way. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and The Globe and Mail

p. 28 Based in the northern Sierra Nevada, Jane Braxton Little is an independent journalist covering science and natural resource issues for publications that include the Atlantic, Scientific American, National Geographic, Audubon, and Bay Nature. In 2023, when the loss of Plumas County’s only news outlet threatened to turn the area into a news desert, Jane helped launch The Plumas Sun, an online platform serving the countywide community. She lives among trees on 34 acres of forestland.

p. 42 Sierra Garcia is a science communicator for the San Francisco Estuary Institute and a former freelance science and environmental journalist. She writes complex stories about oceans, climate, and coasts and is a National Geographic Explorer as well as a scuba dive master. She is originally from rural northern Monterey County and enjoys salsa dancing, free-diving, reading, and playing beach volleyball (badly) in her free time.

masthead, vol 25, no 4 fall 2025

Ex E cutiv E Dir E ctor/Publish E r

Wes Radez

E D itor in c hi E f

Victoria Schlesinger

s E nior ED itor

Kate Golden

contributing ED itor

Kathleen Richards

a rt Dir E ctor

Susan Scandrett

E v E nts coor D inator

Lia Keener

journalism f E llows

Amir Aziz, Tanvi Dutta Gupta, Jillian Magtoto

fact ch E ck E rs

Sarah Trent, Natalia Mesa, Iris Kwok

co P y ED itor

Cynthia Rubin

aD v E rtising Dir E ctor

Micaelyn Compton

P roofr E a DE r

Dominik Sklarzyk

mE mb E rshi P m anag E r

Patrick Brod

D E v E lo P m E nt manag E r

Barbara Butkus

D E v E lo P m E nt assistant

Sheila Moore

f inanc E D ir E ctor

Jenny Stampp

i nformation t E chnology m anag E r

Laurence Tietz

cofoun DE rs

David Loeb, Malcolm Margolin

b oar D of Dir E ctors

Fatima Abdul-Khabir, Deonna Anderson, Tim Falls, Nan Ho, Rebecca Johnson (chair), Matt McKerley, Dana Swisher, Anh Phuong Tran

v olunt EE rs

Kim Dunn, Robert Jankowski, Julie Keener, Kimberley Pierce, David Wichner

Bay Nature is published quarterly by the Bay Nature Institute 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710

Membership: $40 annually (888)422-9628, BayNature.org PO Box 6409, Albany CA 94706

Advertising:

Advertising@baynature.org

Editorial & Business Office: 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710 (510)528-8550; (510)528-8117 (fax) BayNature@baynature.org

Printed by Commerce Printing (Sacramento, CA) using soy-based inks and alternative energy.

Other Contributors: Jane Kim (p. 12), Liam O’Brien (p. 14), Endria Richardson (p. 16), Susan Kuramoto Moffat (p. 17), Tess Taylor (p. 18), Eric Simons (p. 19), Helen Doyle (p. 36), Aleta George (p. 40), John Muir Laws (p. 46).

Front Cover: Valley, blue, and coast live oaks can be found in Alhambra Hills Open Space, along with views of Mount Diablo. By Stephanie Penn, StephaniePennPhotography.com

ISSN 1531-5193

No part of this magazine may be reproduced without written permission from Bay Nature and its contributors. © 2025 Bay Nature

As the days shorten, hunker down on BayNature.org, where you can unearth new stories each week. Find nature news, great reads, events, and places to explore in our weekly newsletter: TinyURL.com/BayNatureNews

The final fish barrier is falling, after decades of activism that began with nighttime dam sabotage. Getting to this point has changed both the watershed and the people who steward it.

Where the Wild ed, Biden’s signature climate laws, BIL and IRA, made it rain for local nature. A “freaking game-changer” for nature: that

» Monarchs and Their Inconvenient Habitat

All the local “critical habitat” groves in a proposed threatened listing for monarchs include a nonnative tree people love to hate. “I wouldn’t actually say that they like eucalyptus,” says one ecologist. “I would say eucalyptus are there.”

» ‘Long-Term Monitoring Isn’t Sexy’

So quips one source regarding the programs that have monitored our waters for decades, are how we know what’s happening to the planet, and are now at risk under the Trump administration.

» Bane of the Picnic, Builder of Hidden

The yellowjackets that bedevil our late-summer outings live in complex underground matriarchies with a lifestyle that is seriously metal.

» The Epic Saga of a Shoreline Menace

In 2016, an uninsured boat captain reportedly fell asleep at the wheel and crashed into the beach. So why did it take nine years to haul off the junk?

I am one of those who has happily received and read (and kept) every issue of Bay Nature from the very beginning. From the “get go,” or “from the gecko” as a mother once told me her young mistakenlydaughter wrote in a school assignment. Thank you all!!

—Lynne Cutler, Berkeley

This is T he 100 T h issue —Vol. 25 No. 4—of Bay Nature magazine, and as frequent readers know, our 25th year of publishing. We’ve been reflecting on that milestone throughout the year—first with a look back last winter at memorable magazine covers, then a shout-out in spring to our cumulative 55 Local Hero awardees, and a refresh this summer of 25 trail-related stories. And now, this fall in this 100th issue, we want to recognize Bay Nature readers.

This magazine and organization are a reflection and measure of you: your passion, curiosity, expertise, and care for the Bay Area’s natural world. Bay Nature is your collective creation, and in a sense more so than for any of us who come and go in our roles here.

Many millions of people, literally from around the globe, have read Bay Nature stories online and in print. But there’s a special subspecies of Bay Nature reader who has been with us for the full 25-year trek and held on to every issue of the magazine. Some of those rare folks responded to my invitation last year to introduce themselves and say hello. With permission, I’m sharing a few of their notes.

Malcolm Margolin, a Bay Nature cofounder and emeritus publisher of Heyday Books, said something to me that I think of often: A magazine is interesting when it brings people together. And that’s the intent, 100 times now, to create a conversation that helps us find each other.

—Victoria Schlesinger Editor in chief

Bay Nature has been a consistent education, inspiration, and pleasure for me during the entire journey [from young techie in Cupertino to land trust board member in Nevada City]. Thank you and the team at Bay Nature for 25 years of such a valuable and unmatched regional publication. I still read every issue cover to cover and every online article, and I look forward to doing so for many years to come.

—Rod Brown, Nevada City

I remember reading about your magazine coming out and walking down to a closet-sized newspaper and magazine place on Grand Avenue to order a copy. For a while I had a second subscription for the elementary school where I was a librarian. Congratulations on 25 years of wonderful issues, nature talks, events, etc. I so appreciate what you do for our environment, local and otherwise.

Barbara Flores, Oakland

I’ve saved all the issues from the beginning though I couldn’t say in which place in the house they all are; I’m just happy to know where the latest one is! And I’m glad I got to write for Dan Rademacher the best thing I’ve ever written: Twinkle, Twinkle, Winter Star (his title, not mine).

—Alan Kaplan, El Cerrito

It drives my wife crazy (OK, other things, too), but I have every issue of Bay Nature, the Great Blue Heron Premier and I keep them in order in net. Thank you for a great all the other work you and Bay Nature.

—Dave Halligan,

I had the opportunity to speak with joined your team and told him how ed the in-depth articles about nature which Bay Nature has provided over ing so many questions that my family we hiked, strolled, and paddled remember that it was one of your chert was formed from radiolarian me to subscribe. Your coverage of its consequences, information about bugs (which we see every year, mostly introductions to nature preserves (with lovely detailed maps) are among send your magazine to the top of Best wishes for the next 25 years!

—Shirley

(OK, this and have saved Nature, starting with Premier Issue, in a filing magazinecabiand and others do at Halligan, Berkeley

with Wes Radez when he how much I appreciatnature in the Bay Area, over the years, answerfamily and I have had as around the region. I your first articles about how radiolarian skeletons that induced of the Vision Fire and about the convergent ladymostly in Muir Woods), and preserves around the Bay Area among the articles that of our “must read” pile. years!

—Shirley Fischer, San Rafael

We’ve kept each and every issue these 25 years as an archive—no, a trove—of illuminating articles, illustrations, and timeless natural history tid-bits, which our family and friends can enjoy rereading.

One of the joys of being a naturalist is that, in finding the answers to questions that pique our curiosity, we always stumble into several more intriguing questions along the way—a “free lifetime supply” of exciting wonder and discovery. Bay Nature has provided a wealth of fascination and interpretation to a broader audience, all in our local “backyard” of the greater Bay Area! It’s well known that such understanding of nature inspires caring about and protecting our wild places, be they a neighborhood alley or the vast wildlands and waters which surround us.

Thanks to Malcolm, David, and you for providing a quarter century of “speaking for the trees”—and for the wrentits, star tulips, whales, ladybugs, trilliums, lampreys, newts, and our other fellow travelers.

—Kurt and Nancy Rademacher, Corte Madera

I came to your first office, which was upstairs from Picante, to subscribe to the brand new Bay Nature magazine. I have saved most every issue. We have a basketful in our guest bedroom for visitors to read. I honestly can hardly believe that it’s been 25 years! It’s always a happy day when a new issue arrives in our mail box! Thank you for all your efforts!

—Joan Johnston, Walnut Creek

...brings with it a little bit of whimsy, the cerulean sky, and a shimmer of promise.

m outh in F oot

In the small universe that is a tidepool, an ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus) dominates its patch of the rocky intertidal. Creeping on hundreds of tiny tube feet, it seeks out its favorite food, mussels. Those little tubes help pry apart the bivalve, letting the sea star begin to digest the mussel in its shell. When ochre sea stars are absent from a tidepool, the mussels can go wild. Kinda. They proliferate, filling an area and influencing what other species settle there. An afternoon in fall, during a low tide—this year, around the first week of December tides will be at their lowest—is an excellent time to catch sight of an ochre sea star, which, a little confusingly, are also commonly purple or orange or brown or red, or various shades in between.

Ev E rlasting

Sometime around now, early fall, young oak titmice (Baeolophus inornatus) will find their mates, often pairing for life, and stake out a woodland territory (mainly oak) spanning up to six acres. If their land includes your yard, and all goes well for the monogamous couple, they will be defending it from other titmice and intruders year-round. Listen this fall for their scratchy calls and in spring for the male’s various songs.

then imagine you’re a female Bay Area blond tarantula ( Aphonopelma iodius), hunkered down in your cozy burrow. The worst of the Diablo Range heat is over, the fall days are growing shorter. Suddenly, reverberating through your home’s dirt walls come quick staccato taps, a few thumps, and bodily vibrations. It’s a male tarantula drumming. After prowling hillsides in search of you, he is now banging out his best solo to woo you from your she shed to mate, and you must decide, “Does this beat get me on my feet? Is that my Phil?”

s hrub o F pl E nty

g uardians o F th E thick E t

The diminutive, ghostly white fingers of candlesnuff fungus ( Xylaria hypoxylon) that reliably rise each fall and winter from decaying wood in Bay Area forests have caught the eye of researchers. They say genome studies show the little fungi produce a slew of unusual secondary metabolites—substances that help with fungal defense, growth, and communication—some of them previously unknown to science and of interest to agriculture and medicine. Even a common fungus can harbor mystery.

The bright red splash of joy that breaks through the sometimes-gloom of late fall and early winter days in the Bay Area comes from a shrub called toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia). Its bouquets of berries feed robins, hermit thrushes, and flocks of cedar waxwings, among other creatures. Tribes throughout the state have recipes aplenty for preparing the puckery fruits. Check Merriam-Webster ’s wonderful etymology of the word toyon, tracing its origins to Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chochenyo, languages indigenous to the greater Bay Area. Toyon is a distinctly West Coast kind of cornucopia.

Mountain beavers ( Aplodontia rufa phaea) are like the gnomes of Point Reyes National Seashore. Emerging at night from their tunnels to gather food, the muskrat-size, stubby-tailed rodents are rarely glimpsed, even by the most quest-driven researchers. But by winter, when the thickets of vegetation thin where mountain beavers make their burrows, one might spy a small, tidy heap of vegetation piled near the mouth of a hole. The sword ferns, coyote brush, and poison oak have been left out to wilt a little, before the mountain beaver brings them inside for food or bedding.

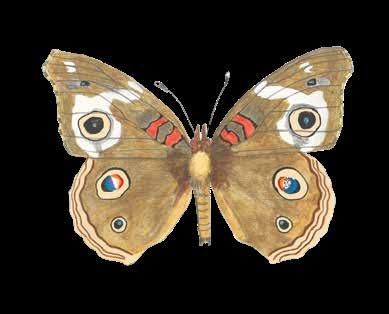

Excerpts from “Butterflies of the Bay Area and (Slightly) Beyond: An Illustrated Guide”

Butterfly migration | I remember living in the Richmond District of San Francisco along Golden Gate Park for a while, and there was a particular day when I was walking and noticed a butterfly flying above me. As I watched it, I saw another, and another, all blasting down Fulton Street. They seemed to be coming out of the park, then heading due west up the road. Another and another, all just going over the tops of cars and my own head. I looked around madly to connect with another human and to verify what I was seeing. It was a California tortoiseshell (Nymphalis californica) “movement”—an explosion of them popping out of their chrysalises after a few days of extended heat, and I was caught up in it, awestruck.

Migration of butterflies doesn’t seem to be as clear cut as those who do and those who don’t. For instance, a vast majority of the blue butterflies don’t fly much beyond where they were born. Many, like gray buckeyes ( Junonia grisea), definitely move about within their range, but they aren’t true migrants like the painted ladies (Vanessa cardui ) and the most famous traveler, the monarch (Danaus plexippus).

So why do butterflies migrate? California tortoiseshells are following the new flowers on plants that are edible in the early spring and then proceed upslope to higher elevations into summer. Then there is a slight reverse migration in the fall. Monarchs travel in search of warmer weather to

overwinter in. Butterflies migrate for different reasons. One rarely sees the full picture of what’s going on because it might take a few generations to complete the journey.

Painted ladies emerge by the bazillions out of the southern realms of California. A great place to witness this is at AnzaBorrego Desert State Park. In the early spring, depending on the year, they can be seen flying in a north-northwesterly trajectory. This butterfly has different migratory patterns throughout the world.

King of all the butterfly migrations is that of the monarch. It is the supreme example of long-distance displacement. Four full generations make the complete journey with the first three having individuals that live up to three months and the final, overwintering generation living four to five. Those living on the western side of America move from basins in Eastern Washington and Idaho in a south-southwesterly direction down to approximately the San Diego area. The ones in the east famously move south along the Eastern Seaboard, round the gulf, and settle in the state of Michoacán in Mexico. Numbers fell to a historic low a few years back throughout its western migration, then rallied like thunder the next year, leading many to conclude that we still have so much to learn with this butterfly. A large group of people are dedicated to this most famous of phenomena.

When butterflies come into an area, they are referred to as immigrants, and when they leave the area they are called emigrants. Those butter flies I saw on the street that day were emigrating to the foothills of the High Sierra. It’s a com plicated behavior that starts to become more clear after many years of watching.

Butterfly watching If you have sunshine and flowers (and even better the two simultaneous ly), the odds are with you that you’ll see some butter flies. They are little solar pan els and they need to be in the high fifties in temperature to really get going. I guess I would have to add a third thing for the ideal recipe—no wind. Butterflies seem to abhor the wind, which makes sense with all their patrolling and following scent trails of pheromones. When looking for butterflies on any windy day, check the leeward side of any hill and you’ll most assuredly find them sitting out of the wind. You may even find them in what we refer to as dappled sunlight— where the shade and sun create glades in a forest or in and out of rows of mature trees on a street. In these areas one might see tiger swallowtails, margined whites, and all of the commas (formerly anglewings). A whole handful of skippers: Common roadsides, arctics, and silverspotteds seem to prefer this habitat as well.

If you get a little more advanced in your

species identification, you develop the ability to “Rolodex” (for you youngsters that was a card index fixed on a wheel people usually had on their desks for phone numbers. Back in the olden days called the seventies.) each environment as you enter it. Say the hike starts in sun at a trailhead, so you think about those species that live only in the sun, then the trail enters full shade. A perfect example of this: One usually only sees a cabbage white (Pieris rapae) in full sun and almost never in the shade of a forest. Its counterpart, the margined white (Pieris napi ), is a denizen of the forest and isn’t seen in the open sun. Coastal scrub, riparian corridors, rocky outcrops, and grassland all have for the most part their

It is sad how much healthy, native habtat our species has altered, but do you want to know an interesting fact?

We’ve actually created butterfly habitat with roadcuts, agricultural field borders, trails, and disturbed areas.

Disturbance is great for the generalists (butterflies that lay their eggs on many host plants) but not so good for the specifests, the species obliged to a single plant, which is usually a native. Fill your gardens with native plants, folks. The generalists will do fine on their own. Remember to look up. It may seem obvious to turn your head to the sky to see a butterfly, but in general people walk looking forward and at the ground before them. There is a whole slew of species up in the canopy of the trees you are either walking below or by. California sisters, mournful duskywings, and golden hairstreaks skip and glide between the oak leaves on a hot afternoon. Keep your eyes moving low, mid-shoulder, and high.

Two other known behaviors of butterflies work toward your advantage in finding them.

The first is the phenomenon of mudpuddling. Males (and sometimes females) need minerals, salts, nectar, and protein to sustain them while in flight. They also play into the male’s need to create a spermatophore packet to pass to the female while mating. Salts are pri marily found in the mud. You’ll mostly see blues and swallowtails there, but oth er species as well in the early afternoon sit ting on the banks of creeks or simply using a puddle to extract compounds from the mud. One can also see them on animal scat extracting minerals and proteins.

The second behavior is hill-topping. Many butterflies, but not all, are internally programmed to go to the nearest hilltop to find a mate. Without this it would be extremely rough to find one another. Why a hilltop? Why do humans go to a singles bar? It’s an excellent way to guarantee procreation for the next generation. It usually gets going about 3:00 p.m., but some species like the anise swallowtail (Papilio zelicaon) are known to start earlier. There are many more boys at a hilltop waiting for girls to fly by. Once you witness this activity on your own it will be difficult to unsee it on every hike with a hill you take from then on. It’s wonderful to see all the aerial maneuvering going on at a mountain summit while trying to tell them apart.

Many butterfly enthusiasts carry binoculars, and this is something you might want to consider purchasing. They’ve made quite a few advances in recent years in close-range binocs, and these most assuredly will help you zoom in on those crucial details. Personally I never got into the habit of carrying them, and they would be rendered useless if I tried now on account of my freakish right eyeball.

To successfully photograph a but terfly, start by remembering that an adult butterfly has the equivalent of ten thousand eyes in those compound opti cal structures. They are programmed just after emerging to dodge anything coming too close—they’ve got mates to find and babies to make. So what is my advice? Don’t act like a bird. No sudden movements. You

will be shocked how close you can get to a butterfly if you move incredibly slow. Slower than what you think is slow. Take your record shot furthest away, then slowly move in for more. If you see the wings go up as you approach and you want that pretty dorsal shot, take a slow step back. (Think about it—wings up means the next movement for the butterfly is a downward exit thrust.) Normally when you take that step back, the butterfly relaxes and drops its wings. If it leaves, don’t chase it. If you stay still, nine times out of ten the butterfly returns right to where it was. As they age on the wing each day, they become easier to approach. ◆

“So what is my advice? Don’t act like a bird.”

you on a hike.”

Iam watching the fall migration pattern of red-tailed hawks across the North American continent. Small yellow circles on a lightly shaded map bobble through time and space, moving south as the seasons progress. Midsummer sees a handful of yellow avatars, symbolic hawks, just beyond the northwestern span of the Chugach Mountains in Alaska. July slips into August into September and October, and the bobbles slip down as far south as La Paz in Baja, Mexico City, almost to Guatemala. The Audubon Society’s Bird Migration Explorer—a beautifully interactive compendium of research on bird migration across the globe— visualizes the migration patterns of hundreds of species of birds. Some turkey vultures spend summers in the northwest mountain ranges, then seem to drop, all at once, tumbling down the lines of flight along the Rocky Mountains and Sierras down through Mexico and Panama, to Venezuela and the top of Colombia in September, October, and November. Snow geese per form elegant, elongated swoops across North America. I toggle between species, delighting in a visualized show of their migration that seems to be— from my computer’s-eye view—giddy, free, pleasing in its easy slide.

Paying attention to these simulated (and of course, simplified) patterns of migration soothes the anxiety I feel about the costs of staying in one place. Perhaps nature can help us to remem ber the primacy of movement, its accord with natural, and not national, boundaries.

No movement is untouched by anxiety. Redtailed hawks, turkey vultures, snow geese, mammals—the blue whales and gray whales and humpbacks—may cue in to the tilting of the earth on its axis toward a lengthening day, changes in air or ocean temperature, the presence of predators to determine when to move south or north. And their movement is rarely unimpeded. Coastal modifications, power lines, wind turbines, roads all challenge migration. They are fixed in place, structures that moving animals must move around.

And then there are ideological obstacles to movement. For human migrations, laws and policies act with the force of nature— dictating when and how and for how long humans can travel, rest, make a home in any particular place. Underlying these laws may be the anxiety that a place must be protected—stabilized—for those deemed to belong. Different administrations respond to these anx-

ieties differently. In part to manage the disturbance that houselessness might cause to those who do live in more or less permanent houses, the Supreme Court in 2024 decided Grants Pass v. Johnson, clearing the way for cities like San Francisco and Oakland to arrest and incarcerate people who have no fixed address recognized by the state. This year, the Trump administration passed Executive Order No. 14160, “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship.” The order radically misreads the 14th Amendment’s birthright citizenship clause—ratified in 1868 to overturn Dred Scott v. Sandford, the 1857 Supreme Court ruling that denied citizenship to enslaved people and their descendants in the United States—to deny citizenship to children of some immigrant parents. Decisions such as these are historically human, too—it is human to seek to protect borders, hoard resources, and attempt to create through cruelty what may feel like a safe harbor to some.

But halting movement requires force and resources too, stokes fear, and raises anxiety. Philosopher Thomas Nail describes “the primacy of movement,” a theory of movement that does not seek any ultimate cause, that proposes that movement simply is. Thinking about movement in this way, Nail argues, might fundamentally shift Western philosophy’s assumptions about the human and natural worlds, in which “immaterial and unmoving entities like mind, spirit, essence, form and God were seen as superior to material and moving processes like nature, bodies, weather, and animals.” Nail links ideological systems like patriarchy, racism, and ecocide to a worldview that values that which is immobile over that which moves freely.

To be mobile—not rooted by nation or property—according to Western philosophy, is to be closer to nature, the moving whales, the flying birds, the changing weather. To block a border, a route, a place to sleep, is, among other things, an attempt to assert a hierarchy of beings: ranking those who don’t need to move above those who do.

The question I ask myself constantly these days is what can I do—in the face of the seemingly endless violence humans will invoke to halt a changing sense of place. But what if we embraced the primacy of movement—not just of things, living and nonliving, but of ideas of place, of life itself? That all things have a will to move. Perhaps it is a place to start. To know that a house, an ecosystem, a country, its borders, are as fleet as a red bird against the sky, dipping, gone. ◆

For open-water swimmers like me, autumn in San Francisco Bay is a halcyon moment between the punishing winds of summer and the frigid swells of winter. It’s the one season when both water and air are calm and warm.

Early fall is also the saltiest time of year. To me, the autumn Bay tastes like very briny chicken soup. In winter and spring when rain and snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada dilute the seawater, it’s more palatable—only a third as saline.

For a human, swings in salinity in this range are not a problem. But when I have been immersed in extremely salty seas—for example, the Sea of Cortez—my throat and nasal passages and eyes burned. My mucous membranes were reaching the limits of their osmoregulation—their ability to maintain a healthy electrolyte balance. Regular ocean water is more than three times saltier than the fluids in the human body.

This made me wonder what extreme salinity shifts feel like for creatures that are continuously immersed. Most marine invertebrates are osmoconformers. Water flows in and out of them, and, unable to adapt, they die when it’s too salty or fresh. In fall, the underparts of docks in the Bay are covered with bryozoans and sea squirts. Many of these tiny, mostly exotic, salt-loving animals almost disappear from the Bay in winter when fresh water pours in.

Other animals, the osmoregulators— which include mammals and most fish— maintain a specific internal balance of electrolytes. As Chinook salmon swim upstream from the Bay into rivers, their kidneys discharge excess fresh water through urine as their gills keep their bodily salts in balance.

It is biologically challenging to be euryhaline—amenable to a wide range of salinities—and the vast majority of aquatic organisms are not. But many of the organisms of the Bay are masters of this form of adaptability. Foundational species including eelgrass and native Olympia oysters can

thrive in a wide range of salinities, although they prefer near-oceanic conditions. Some native mussels can handle more salinity variation than exotic ones, notes environmental scientist Daniel Killam from the San Francisco Estuary Institute.

Remarkably, many Bay creatures acclimate to salinity that fluctuates dramatically not just by season, but throughout each day. In response, some mussels clamp open and shut, Taylor’s sea hares adjust their respiration, and fish swim toward their preferred salinities as hormones change the way their gills filter water.

Nearly a quarter of the Bay sloshes in and out of the Golden Gate twice each day with the tide, mixing salt and fresh water on a staggering scale. The surface of the Bay reveals this flux in subtle shades—fresher, browner, more sediment-laden water floats next to, and in some places on top of, denser, clearer salt water, with turbulent churning and stratification happening below. The daily salinity forecast on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration website makes the surface flows vividly clear: It features a mesmerizing animation in colors from deep blue (fresh) to yellow (brackish) to red (salt).

As late fall rains bring fresh water into the Bay, the red shifts downstream toward the ocean and the pattern becomes more complex. Soon, winter water from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers pushes west and south in a blue-coded tongue of fresh water under the Richmond Bridge. It then squeezes between Angel Island and Tiburon on its way to getting sucked out the Golden Gate into the Pacific with the ebbing tide. But a couple of seconds later in the animation (and a few hours later in real life), the ocean pushes back against the river water, sending a flood of yellow-coded brackish water toward Alcatraz Island. The flows are not always continuous streams but detach and float in ragged blobs—variations that swimmers can taste and feel.

In the current dry season, though, the complexity is reduced to a simple line between blue and green sliding up and down in a narrow stretch of river some 50 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean.

This constantly shifting line between salt and fresh, known to scientists and policymakers as the X2 line, is literally the front

“To me, the autumn Bay tastes like very briny chicken soup.”

In early fall, the animation looks a bit alarming. The central Bay is a seething sea of red (salty) water. The round basin of San Pablo Bay pulses like a crimson heart pumping ocean water up into the Delta. The salty water extends well upstream of the Carquinez Bridge to Antioch and beyond.

line of California’s water wars. The salty territory of the Bay has been subject to change as dams and diversions sluice more than half of the fresh river water from the Sierras away from the Bay and toward Central Valley agriculture and to Southern California cities. This salinity threatens not only to wipe out certain fish species, but to invade agricultural and urban water supplies.

The Bay water on my tongue is saltier than it’s been for most of the past millennium. That’s a big problem for some organisms, including humans, and climate change is making it worse. By immersing myself in the Bay, I’m getting a taste of things to come. ◆

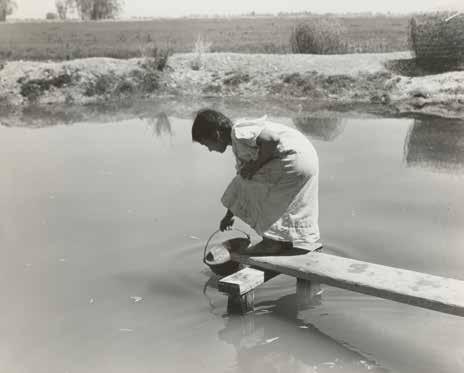

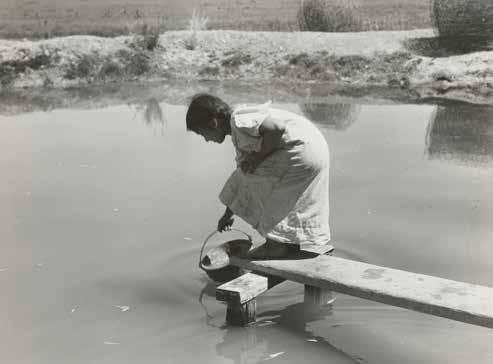

There’s an image by Dorothea Lange I think of often. It’s a bright day in March 1935, and a young woman is perched far out on a plank above a makeshift pond of irrigation runoff, balancing as she dips her bucket in. Lange’s caption describes this scene: Drinking water for field worker’s family. Imperial Valley, California, near El Centro. The photo puts many elements in stark relief: the need for clean drinking water; the need to water crops; the need for decent work; and wider questions of which systems allow people to drink, eat, and live in dignity. The woman holds her fragile balance on the plank: Nothing about these questions is easy. Lange photographed water frequently—at scales that ranged from huge irrigation systems to clean cement washtubs at newly constructed labor camps to rusting buckets at the door of farm laborers’ encampments. A working mother who hung her drying prints in her garage next to her own laundry, Lange also loved photographing laundry on the line. Yet together, her drinking-water, irrigation-water, and laundry shots weave to depict bigger concerns: How do we create systems that let us live justly with one another and the earth?

At the moment Lange made her “Drinking Water” photograph, Imperial County,

which receives less than three inches of rainfall per year, was also becoming the site of the All-American Canal, a vast dam and tunnel scheme that diverts Colorado River water from near Yuma, Arizona, and channels it along the U.S. border, so it can irrigate crops in a desert 80 miles away. Lange photographed the canal’s construction, documenting the way it changed labor and agriculture. Ninety years later, the canal still flows, though huge border walls run along it, and the distant river, groundwater, and mountain glaciers that feed it are all imperiled.

Imperial County is still a center for water-intensive crops like alfalfa, carrots, and lettuce. It’s also a center for border security. While most people don’t pull daily drinking water from irrigation ditches, the county (where the unemployment rate peaked at over 20 percent in July) is still a place where people live in great precarity, using imported water to farm a desert that often reverts to toxic alkaline dust.

“Everything is difficult to photograph well,” Lange commented in an oral interview at the end of her life. “But what surprises me is that when [photographers] present this story of agricultural labor, people don’t really see the big story behind it, which is

the story of our natural resources. . . . That’s where the documentary job has got to be done, to show, for instance, what we in California have done in passing the water bill.” It is hard to photograph a bill, or to figure out which telling details let us glimpse the larger stories in which our lives are enmeshed. Yet Lange was an amazing notetaker and visual storyteller. Across decades, she found ways to interleave the environmental and social concerns of a rapidly changing California.

Later, Lange would photograph development from different angles—documenting Bay Area fields ripped up for tract housing, the communities of the Berryessa Valley being displaced to create the reservoir that is now Lake Berryessa. It sits above a dam on Putah Creek, over the ghosts of destroyed farming communities, regularizing water for the large-scale crops that make Northern California famous: grapes, tomatoes, almonds. In these backstories of the California we inherit today, Lange still asks us to bear witness to the fragile accord we strike with one another, and with the earth itself. Lange’s colleague Ansel Adams spent the 1930s and ‘40s mythologizing a California of rare, seemingly unspoiled places (think of the unpeopled shot of a Jeffrey pine). In the same decades, Lange made a different sort of environmental photography: one that examines the costs and compromises that build and sustain our lives. To me, Lange remains the richer environmental prophet: Enmeshed in what my friend Maggie likes to call “unsexy infrastructure,” she photographs the challenges facing people who labor, the immense project of producing food, the difficulty of finding balance between our hunger for things and their cost. So much of her work—about shelterlessness, migrancy, climate catastrophe, even internment—provides a prescient map of the issues we live with now. Lange shows us a California that’s not pristine, but problematic—and like the woman bending over the irrigation ditch, thirsty—in this case for our attention, our fascination, our care. ◆ Tess Taylor

Tess Taylor’s play Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange will premiere at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art this Nov. and Dec.

A colony of hundreds of small animals, whose symbiotic bacteria pumps out human medicine.

by Eric Simons

toms, and nuclear-power plant water-intake pipes. To go find a public dock, to lie down on what is usually a splintered and birdpoop-covered platform and dig into what is usually murky green water to look for these creatures feels like an unseemly relative of tidepooling. It does not necessarily smell of the sea at its freshest, but you do find a lot of weird stuff.

Once, on a trip to examine dock fouling at Jack London Square in Oakland about a decade ago, I hauled up a thimble-size brown shrubby thing, like a little sandy snowflake. Its branches forked outward and had spots. It matched, in appearance though not fully in color, an abundant creature I had read about in my field guide called Bugula neritina, whose common name is “brown bryozoan.”

Now, it turns out it wasn’t. It took me a while to realize this. In the intervening time I learned some incredible stories about Bugula neritina. One thing I learned: mistaken identity may be where most people start.

i n the late 1960s a lab at the National Cancer Institute found that something in Bugula neritina had the potential to suppress tumors. Over the next few decades scientists at NCI isolated the key compound, which they called bryostatin 1, and advanced it from lab studies to preclinical trials in animals to human clinical trials targeting several different types of cancer.

But the course of Bugula does not run smooth. The human clinical trial results were disappointing; bryostatin 1 didn’t beat cancer. Scientists also realized it wasn’t Bugula neritina that makes bryostatin. The actual compound appears to be the handiwork of

a bacterial symbiont that lives with the Bugula. And it turns out it’s not just me who struggles to identify Bugula neritina; there are precious few bryozoan experts and even they might need close examination to tell Bugula neritina from other bryozoans.

Once scientists had identified the value of bryostatin 1 they naturally went out and gathered lots of what looked like Bugula neritina. But 14 tons of dripping sea creatures had yielded only 18 grams of bryostatin 1—“three full-grown African elephants reduced to the contents of a small salt shaker,” Stanford chemist Paul Wender told me. The cost and complexity of harvesting bryostatin 1 from nature didn’t match the reported benefit. As the supply slowly dwindled, it appeared that bryostatin 1 would be a medicinal wrong turn.

Have I mentioned that when it comes to Bugula, appearances can be deceiving?

Bryozoa is an oxy M oron from the old Greek: bryo (moss) and zoa (animal). What we see when we look at bryozoans is actually a colony of dozens to millions of small animals, with animal features like mouths and guts and complex interpersonal dynamics. The colonies can take different forms, from elegant fans and trees to rubbery crusts and gelatinous goop clumps.

(A tangential mistake, entirely my own: the word Bugula clearly looks like it should be pronounced BUG-you-lah and appear in horror-movie font on Hollywood movie posters. Yet the scientists very clearly pronounced it BYOO-gyoo-lah. They were consistent on this point, but as I am writing this I am saying BUG-you-lah in my

vast majority of marine species are nonnative, Bugula neritina is one of the “dominant players” in the dock fouling scene, says Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) ecologist Andy Chang. The SERC group studies Bay invasions by dropping plates into the water in dozens of places and recording what grows on them over time. Though it’s unclear what specific harm Bugula neritina might be doing in an already-altered Bay, it is clear from the research that it’s fast-growing, fast-spreading, and flexible.

It turns out that so are lots of other bryozoans. The SERC group has found 25 species of nonnative bryozoans making a home in San Francisco Bay. Many of them, to my non-expert eye, look the same. “It’s a little bit like a mystery that you have to solve,” says Linda McCann, a research technician and bryozoan specialist at SERC. “You get better and better at solving them as you look at more and more of them.”

Almost all of us have non-expert eyes when it comes to bryozoans. Only a handful of scientists study bryozoans, says Megan McCuller, an invertebrate collections manager at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. And if you want something identified, she adds, “it’s just word of mouth. Contacting people. By people I guess I mean me and Linda.” (McCuller did mention one more bryozoan superstar, Judith Winston, who continues to study bryozoan taxonomy in retirement but has less of a public role.)

About six months after I had first found what I thought was Bugula neritina on the fouled dock in Oakland, McCuller found my uploaded photo and suggested it might not be Bugula at all, but

targets an enzyme called protein kinase C, or PKC, which plays a key role in promoting tumor growth. Because this is still a Bugula neritina story, though, there turns out to be a different path.

By the late 1990s, a lab led by Daniel Alkon at the National Institutes of Health discovered that PKC played a critical role in memory formation and storage. One form of PKC in particular, Alkon told me, is a kind of “master of ceremonies” for synapse growth and neuron protection. Alkon’s group searched the research literature for any compound known to activate PKC and be safe for human use. They found bryostatin.

Animal trials soon showed that bryostatin 1 could “enhance memory,” Alkon says. As scientists switched from cancer application to memory issues, a new problem arose: Only a few grams of bryostatin 1 remained at the NCI. Grabbing more from the wild was impractical. Attempts at Bugula neritina aquaculture had failed. The only hope for future study was somehow getting more bryostatin 1 without taking more Bugula neritina.

Many experts were pessimistic there would ever be a practical solution, but two groups, including Paul Wender’s lab at Stanford, managed at the eleventh hour to efficiently synthesize bryostatin 1 in the lab. In 2017, Wender and colleagues published a 29-step process to make clinical-grade synthetic bryostatin 1. “In science,” Wender says, “the impossible is possible.”

Now Wender’s lab fields calls from medical researchers around the world asking for bryostatin 1. Among them are Alkon’s company, Synaptogenix, which has used Stanford bryostatin 1 in prom-

ising clinical trials on Alzheimer’s patients. In one recent trial, moderately severe Alzheimer’s patients who were given bryostatin 1 showed no significant cognitive decline over 42 weeks. “We were able to get a complete arrest of that progression with bryostatin,” Alkon told me. Other researchers have also suggested that bryostatin could benefit patients suffering from strokes, epilepsy, HIV, or multiple sclerosis. From a handful of Bugula neritina mailed to the National Cancer Institute in the 1960s, science has uncovered a rich world of possibility.

“We know nature has all sorts of solutions to problems,” Wender says. “But up until we developed the [right] analytics tools we weren’t able to understand. It was a library that was locked. Now we can go in, read what nature is doing, and build on it.”

You’ve heard the argument for conserving biodiversity because of the medicines as-yet undiscovered in the rainforest or among the coral reefs. It’s something of a delight to realize that it doesn’t just have to be exotic places. In the shadow of rusting cargo ships in the midst of our heavily urbanized estuary lives this wildly challenging species complex, a globally invasive nuisance dock fouler with a horror-movie name, whose symbiotic bacteria pumps out human medicine.

When i F irst started reading about Bugula neritina, I noted the journal articles about bryostatin 1 that mentioned its frustrating scarcity, while ecologists wrote about the ever-proliferating Bugula neritina populations in dock fouling communities worldwide. When I was talking to Linda McCann, the Smithsonian bryozoan expert, I mentioned that contrast and she paused. “I can’t imagine running out of this species, honestly,” she said.

Yet after finding out that my Bugula investigation had launched with a mistaken identification, that much of what’s labeled “brown bryozoan” in iNaturalist probably isn’t and that the bryozoan isn’t even brown, that the medicine maker turned out to be a symbiotic bacteria and not the Bugula neritina itself, that the tumor suppressor had turned out to be also a memory enhancer, I decided I needed to find at least one anchor of clarity. I

some sample containers and my 10-year-old daughter into the car to go take one more look. Margaret regularly lists dock fouling as among her favorite activities. Once, when her sister and I were heading out in the morning to go running, she rolled her eyes and said, “well, the two of you wake up early to run. You and me wake up early for tidepools and dock fouling.”

We started at Jack London Square, where we had the public dock below Scott’s to ourselves. The restaurant hadn’t opened yet, but we could see the tables all set, wineglasses and big folded napkins out and ready for work lunches and celebration dinners. Once, as we were wrapping up a dock fouling trip in this spot, a school of bat rays glided by just at sunset, graceful fins rippling the surface. I remember the sun gleaming on the restaurant windows, the fog draped over San Francisco, the sailboats rocking and clanking in the breeze, our tubs full of bizarre orange and yellow and green life-forms, and I remember thinking this might be the most perfect place I know.

Now a few clouds floated overhead as Margaret and I chased some pigeons away and got to work. We caught a Bay pipefish fleeing to deeper water, and we found a trio of Hedgpeth’s sapsuckers laying eggs around the sea lettuce. Margaret yanked up a bryozoan from a large field of them, structurally appropriate but sandy in color, probably the Tricellaria I’d seen so many years ago.

For an hour or so we poked and prodded and brought things to the surface to examine. Finally, just as we had packed up to leave, Margaret reached way down under one of the dock platforms and pulled up a branching, distinctly purple bryozoan.

So was it Bugula neritina? The docks are home to so many creatures, and so many stories. One researcher I talked to forwarded me a list of other marine invertebrates linked to medicine: sponges, tunicates, snails, other bryozoans. You might find a backstory like Bugula’s for dozens of the animals living in a few feet of one crowded dock.

Inevitably we mix them up. Sometimes we get things wrong. But we always learn from the endeavor. In the end, attention

“This is the one I originally identified as Bugula, given that it’s, well, brown and a bryozoan. But they are maybe Tricellaria bryozoans.”

In gardens tended by first-generation immigrants, pollinators flit between homeland and native California plants. by Ji

I often imagine what it was like to immigrate to California. The state probably felt big, dry, and daunting. My grandma said she wasn’t ready to leave her life in Hong Kong in the late 1970s when her family, including my mom, packed up for Los Angeles—preemptively avoiding Britain’s handover of Hong Kong to China. Not long after, my dad and his family immigrated from the Philippines, making the same journey, but to escape dwindling opportunities and search for jobs that could one day lead to owning a home.

What did my family leave behind in pursuit of better lives? How much do they miss? I remember how my grandparents surrounded themselves with familiar aromas, foods, and customs from their homelands that enveloped my siblings, cousins, and me as we grew up. My Chinese grandparents taught us how to kneel to Buddha, they read us folklore, and we played jungle animal chess. My Filipino grandparents took us to Sunday school and fed us a steady supply of imported dried mangoes and coconut-rice desserts, watching with full attention as we gobbled it up.

Outside the house, my grandparents learned to cultivate a sense of home with plants. One of my grandmothers planted sweet potatoes on her small balcony to harvest kamote leaves, a nutritious green that adds a pleasant bitterness to sour Filipino broths. My other grandmother started with mildly sweet small winter melons, popular in soups and stir-fries, that she grew in potting soil recommended by other Chinese nurses. Today her backyard

garden bursts with dragon fruit, tomatoes, and oranges, maintained by methods she learns from YouTube videos.

In the Bay Area, people like my grandparents aren’t hard to find. Immigrants make up about one in three residents in the Bay Area, or over half in many neighborhoods. And in their endeavors to create homes, they imprint themselves on the land. They plant with deep intentions to create abundance for bugs, birds, and their own families. In my reporting—an effort to learn how immigrants remake their homelands through gardening—I saw plants from all over the world that were food and medicine, each an opportunity to build families and communities. Many people planted California natives that attract wildlife, especially pollinators that flit between the homeland and native plants, encouraging both to grow. The result is an evolved sense of home—a blending of ecologies.

Like my dad, Vilma Aquino remembers the nights sleeping on bamboo mats in bamboo huts in the Philippines when she was young. She helped pump water from her family’s well and ran barefoot through sugarcane fields and coconut trees. Her mother and family grew vegetables and raised meat to sell at the market. Then it all ended abruptly at age five, when her family moved to San Francisco in 1965 in search of similar opportunities my father’s family desired. But in the city, there was no land or garden for her

family to tend that might have helped feed Aquino and her six siblings. “I would be so hungry, because there was never enough food back then,” she says. “We were dirt poor.”

Decades later, with a backyard of her own in Vallejo, Aquino planted her first sugar snap peas and tomatoes, growing food for her children. After that she was eager to learn, scouring books, watching lectures and videos, and taking courses to become a master gardener. “I just evolved, and I just kept wanting to learn more, and how we can all play in the ecosystem with balance.” She also began to feel control over her health. Filipino Americans are especially susceptible to heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes compared to the average American, largely due to adopting westernized diets and lifestyles, according to a variety of studies by Virginia Commonwealth University and University of Hawai’i cancer centers. Gardening offered a different path: “When you grow your own food, and you get all that minerals and vitamins and good stuff and the fresh air, you start to become healthy too.”

Today, Aquino is in her 15th year of leading Vallejo People’s Garden in a lot next to a church with a mostly Filipino congregation less than a block from her home. She began it as a way to connect with her roots, by “being amongst other Filipinas in this urban environment and growing food that I’m familiar with,” she says. Alongside Filipina volunteers, she manages 22 beds, many filled with Filipino staples like luffa, taro, and chayote, commonly boiled in soups. Circling the beds are bay trees, whose dried leaves help develop earthiness in adobo, banana leaves to wrap around rice or meat, and guava leaves that help alleviate stomachache. She shows me a fiery costus, or the insulin plant, whose broad

green leaves on branchy twigs are believed to lower blood glucose. “When you chew on it, ” she says. “It helps to manage diabetes.” Aquino’s garden overflows with turmeric, heirloom tomatoes, and Chinese cabbage—a variety of food that reflects Vallejo’s status as among the most racially diverse cities in the Bay Area. Interspersed with the garden’s food and home remedies grow California natives like ceanothus and milkweed. A “pollinator pathway” leads through sections of native garden dedicated to pollinator habitat: seaside daisies for bats, sticky monkey flower for hummingbirds, California goldenrods for beetles, showy milkweed for butterflies, yarrows for beetles and bees, Pacific asters for flies, baby blue eyes for moths, and Oregon grapes for wasps. More than 30 native plant species, along with educational signs, line the path. “Native plants support so much more wildlife,” says Aquino. “A garden is evolutionary, just like people are.”

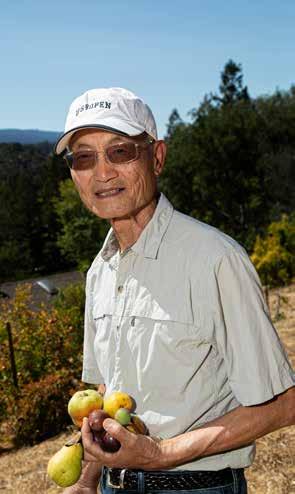

r ough L y six mi L es northwest of where my mother spent her early childhood in Hong Kong, Andrew Chang grew up at the base of a mountain near a jungle. There, he was known as the boy who wrangled snakes. His remote village of about 100 households sat a mile from the bus stop, inaccessible by car. Wildlife moved fluidly between the village and jungle. Cobras and other snakes slithered down the hills to homes and yards, or sometimes, into couches. And when that happened, the villagers called upon Chang.

He would sneak up from behind and grab snakes even if they were poisonous, then give the gallbladders to his grandmother to eat, a Chinese remedy she claimed helped a person stay warm

during winter months, during a time without heaters. At around 10 years old he was helping feed his family by growing a patch of green onions, bok choy, choy sum, and eggplants. He felt satisfaction in seeing a plant grow.

Chang tended the garden until he left for the United States at 19 in 1965 (the same year Vilma Aquino moved from the Philippines) with less than $100 to his name and a strong desire to leave British rule. His attempts to get a visa included a handwritten letter to then-president Lyndon B. Johnson. He made his way through Bay Area schools studying electrical engineering and computer science, working nights and weekends at burger joints and farms. Now, he lives in Los Altos Hills surrounded by 1.7 acres of oaks, grasses, a chicken coop with pigeons, and a grove of large fruit trees. I’d describe his house as sitting in the center of the expanse, like a wooden boat in a sea of green. He lives with his environment, just as it is.

Many of the grasses growing on his property are invasive and too abundant to weed. But he doesn’t mind walking through thickets or tussling with the ever-hungry fauna. “I have lots of wildlife,” he says, and it’s clear he pays close attention to their interactions. Deer and gophers are nuisances; coyotes and hawks help stave them off. Sometimes, he brings in gopher snakes or rattlesnakes he finds on the street to keep the rodents at bay. He also tries to attract different kinds of bees, he tells me while observing little ones zipping between the poppies planted along his driveway. The bees help pollinate his Chinese chives, red dates, and kumquats. As we walked through thigh-high grasses and weeds, I wondered if he had created a California version of his wild homeland.

Chang’s reason for gardening is simple. “I just like being able to

plant things and be able to harvest them myself for me, for family, and for friends,” he says. He gives pomelos as gifts to promote healthy and numerous offspring during the Chinese New Year. He also teaches a Chinese cultural class and tells students about the legend of the red date (sometimes known as jujube), a tale of a future emperor’s daughter who used the dates to help a village survive a famine. And he tells of their medicinal effects. Chang began planting and eating red dates when he was diagnosed with stomach cancer 30 years ago, and he’s now cancer-free. When his students have “health issues . . . sometimes they ask me for it,” he says about the dates. “I share with them.”

Despite everything he grows, Chang doesn’t consider himself a gardener or his land a garden. “I’m kind of more like a resident steward,” he says. “I call it a jungle.”

w hi L e Chang arrived in America with a strong desire to leave Hong Kong, that was not the case for Antonia Master, from Athens, Greece. Master arrived in Martinez, California, in 2000 at age 23 with what she called “the infamous 90-day fiancée visa” and a case of homesickness. “You don’t have your smells, you don’t have your people, you don’t have the places you knew,” she recalls. Above all, “I couldn’t find the same type of oregano that had that same taste and the same aroma like I was used to.” At the time, Greek products like oregano and yogurt were scarce in grocery stores. And so she went hunting.

She didn’t have to look far. Other local Greek Orthodox churchgoers in Vallejo were exchanging seeds and seedlings from trunks of cars—varieties of eggplants, oregano, and tomatoes you wouldn’t find in your average grocery store. “Can you spare

some from your garden?” she would ask. Finally she received her first oregano seedling and began joining in the trades. “We pass the oregano like it’s some type of gold,” she says.

Still, she wasn’t much of a green thumb. Athens was “a big city made out of cement,” she says; the rows of apartment buildings only allowed for small pots on balconies. “I had not grown a leaf in my life.” So her now-former mother-in-law, also from Greece and about 50 years her senior, took Master under her wing. “You’re gonna put the tomatoes there, because they’re gonna be happier there than the other side,” Master recalls her saying. “Pick the oregano when the first flower blooms, not before, not after, because this is when it has the maximum flavor, and the flavor will last for the whole year.”

Now in her backyard home garden in San Bruno, she seems to have mastered these traditions. She grows basil next to a Greek eggplant variety to fight off pests, attract pollinators, and improve the eggplant’s flavor. She grows Concord grapes alongside her fence and rolls the third and fourth fingers of each leaf into cigars to preserve in plastic water bottles for dolmas. She always makes sure to bend down and pet her basil plants, giving each little bush a shake to release aromas into the air. It’s a Greek tradition you must do, she says, because you “can’t trust anyone who doesn’t want to smell basil.”

At the front of Master’s garden is a mix of native and pollinator-friendly plants—dark indigo salvias, white-flowered achilleas, sunshine-yellow fernleaf yarrows, and lavender-speckled rosemary. And with them come the regular visits from bumblebees nesting underneath her backyard shed. The natives that bloom earlier hold the pollinators in the garden for her late-blooming

Greek plants. “I think the garden is just like California. It’s a melting pot,” she says. “We all do better when we’re all together.” Her garden beds are dotted with pollinator watering stations, filled with marbles so that the bees, butterflies, and moths don’t slip and drench themselves in the small puddles. Hummingbirds take bird baths in her small fountain.

“I tried to make my garden part of what I was missing back home, and of course, it evolved,” Master says. “It’s both a California gar den and Mediterranean garden.”

u n L ike the other immigrant gardeners and stewards I met, José Gutierrez was born a gardener, specifically a bee keeper. Since he could walk, he worked from dawn to dusk on his family’s more-than-500-acre ranch in a valley surrounded by mountains in the small town of Matatlán in western Mexico. His family grew corn, beans, peanuts, and zucchini and raised pigs, horses, and bulls. But his father also grew orange, lemon, papaya, plum, and cherimoya trees that produced fruit thanks to the abundance of bees he captured in a collection that grew to over 100 boxes.

Gutierrez caught his first bees at just five years old, and he couldn’t wait to show his father. He wasn’t afraid, wearing just a head wrap his mother sewed from scraps of fabric and armed with only a stick, a box, and his dad’s love for the bees. Despite getting stung on his face, he was able to capture a swarm’s queen—and

the rest of the bees followed. “He said, ‘Oh, you are a good beekeeper,’ and I feel good,” says Gutierrez, remembering his father’s reaction. “He gave me a chance to work with him.”

But his ranch days ended when he was 14 after tragedy struck: his mother’s death. Gutierrez and his five siblings moved to Guadalajara and he had to leave school, working to support his siblings. He was first among them to move to America, a 25-yearold with $80 in his pocket, in 1975. “I arrived on Sunday and started working on Monday,” he says. Five months later, his wife and children were able to come live with him in Hayward. It took another decade to buy a house and finally begin the garden and hives he’d been missing.

Fast-forward 35 years, and I’m standing beside a variety of medicinal herbs bulging from what looks like a single bush that sits in front of the house. It’s a common Mexican tradition, Gutierrez’s grandson Julio Contreras says, explaining that the herbs serve as the family’s first line of defense against ailments, so it needs to be accessible. In bloom are muicle, aka Mexican honeysuckle, for anemia, and cedron, lemon beebrush, for digestion. Jammed in

between them are plants like estafiate, or white sagebrush, for colic, and sábila, or aloe vera, for burns. One plant, whose leaves are shaped like cow hooves, climbs his walls, aptly named pezuña de vaca or the Brazilian orchid tree, is good for people with diabetes like him, he says.

Gutierrez also grows guayabas, persimmons, chayote, lemons, and a dozen varieties of peppers surrounding the house in black plastic pots that remain unplanted in the compacted dirt. Pots and pans sticky with honey are scattered about, and as I follow the trail of bees (and flies), the buzzing grows louder. At the back of his yard, a half dozen hives in wooden boxes casually sit near the fence he shares with his neighbor, next to a row of orange trees. As they were on his father’s ranch in Mexico, the bees feel like part of his family. “They remember you,” he says. “They can see you almost two, three times a week, they recognize your face.”

Even the bees themselves are medicine for the family. Gutierrez’s wife, saddled with sewing machine shoulder pains, often asks him to sting her with four or five bees. The sensation is soothing: “For three or four months, she doesn’t have pain.”

In bloom are muicle, aka Mexican honeysuckle, for anemia, and cedron, lemon beebrush, for digestion. Jammed in between them are plants like estafiate, or white sagebrush, for colic, and sábila, or aloe vera, for burns.

Gutierrez’s bees now live well beyond his backyard. He looks after 100 hives at locations in the Bay Area from San Leandro to Hayward—it’s the buzzing engine of his family honey business at the Hayward farmers market every Saturday; some of his 17 grandkids and 13 great-grandchildren participate. A number of the hives reside at community gardens in Ashland and Cherryland, unincorporated communities in Alameda County.

The family began running one of the gardens last spring, planting rows of corn, bean, squash—three crops known throughout the Americas to grow well together. Other immigrant families have taken notice and begun helping out, admiring corn varieties they thought they would never see in California. Alongside it, purple collard greens planted by past community garden groups grow en masse, tended by the Gutierrezes for the plant’s significance to the Black community. There’s a plan to put hives between the native yarrows and achilleas at the back of the garden and the planted crops up front. The pollinators help both areas thrive.

San Francisco Bay winds for the past 24 years. Humidity feels foreign to me, and dryness feels normal, despite flare-ups of eczema and dandruff that seem to be telling me otherwise.

Belonging, I realized, isn’t straightforward for my grandparents either. In preparation for my grandfather’s funeral earlier this year, the funeral home managers asked my grandmother how she would like to proceed with Chinese burial traditions. “I don’t know,” she responded. She has never had to bury someone in China. “I am Chinese American,” she stated.

I never saw that. I only saw how she finds speaking in Chinese easier than English, plays mahjong at her community center, and sings Chinese opera. But in fact, she has been an American longer than I have been alive and has been in Los Angeles longer than she’s lived in Hong Kong.

She has lived the American dream and grown alongside this country since the ’70s. She and my grandfather listened to the Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel on their record player on repeat.

Different people can belong to these community gardens, says Contreras, who is now a beekeeper and 4-H program coordinator for the University of California Cooperative Extension. It’s for family, immigrants, and everyone, he says, who passes by the chainlinked fence and sees land they want to help cultivate.

i have a L ways wondered, what land do I belong to? I think it must be the land my parents belonged to and the land their parents belonged to. My nose is wide; my skin is brown-ish—I’m suited for the tropical, humid climates in Southeast Asia. But really, my body has acclimated, dried like jerky in the Los Angeles heat and

Her garden isn’t just a piece of land to produce familiar food, but a place where she makes something new and entirely hers. The tomatoes and dragon fruits are not Chinese, and neither are her compost methods from YouTube. I think the only things directly imported from China are her potting bags and watering bulbs from Temu. As she gardens to feed, grieve, and learn, the garden’s vibrancy reflects her well-being and determination to thrive despite loss. Instead of wondering what land I belong to, maybe the better question is the one my grandparents asked: What land can we create? ◆

Dedicated to my late grandfather, Daniel Ho.

To protect the Plumas National the next megafire, the Forest

Forest and its communities from Service plans to burn it—intentionally. Can $274 million do the job?

By Jane Braxton Litt L e

Awhite-headed woodpecker stirs the dawn quiet, hammering at a patch of charred bark stretching 15 feet up the trunk of a ponderosa pine. The first streaks of sun light the tree’s green crown, sending beams across this grove of healthy conifers. The marks of the 2021 Dixie Fire are everywhere. Several blackened trees lie toppled among the pale blossoms of deer brush and the spikes of snow plants, their crimson faded to dusky coral.

Flames raged through neighboring forests, exploding the tops of trees, flinging sparks down the mountainside until, on August 4, 2021, the fire itself reached the valley below and Greenville, 90 miles north of Lake Oroville. It took less than 30 minutes to destroy a town of 1,000 residents. Yet this stand at Round Valley Reservoir survived.

Years earlier, U.S. Forest Service crews had removed the brush and smaller trees, reducing the most flammable vegetation. Then they set fires, burning what was left on the ground in slow-moving spurts of flame. When Dixie arrived, the same fire that melted cars and torched 800 homes hit this stand and dropped to the ground. Here Dixie was tame, a docile blaze meandering across the forest floor with only occasional licks up the trunks of trees, says Ryan Bauer, Plumas National Forest fuels manager for the past 18 years.

If only there had been more active forest management like this, laments Bauer. Instead of 100-acre patches, “if we had burned 10,000-acre patches, we’d have 10,000-acre patches of surviving forest. We just never did,” says Bauer, who recently retired and is now working with a nonprofit to adapt communities to fire.

Two-thirds of the Plumas National Forest has burned in the last seven years, an area twice the size of San Francisco Bay. The fires have sent smoke charging down the Feather River Canyon, across the Central Valley, and into the San Francisco Bay Area, turning the sky burnt orange. Each fire has taken a toll on the watershed that provides drinking water to over 27 million people in California. With every blaze, habitat for deer, bald eagles, and four of California’s 10 wolf packs hangs in the balance.

The rest of the Plumas Forest is still green but far too crowded, with trees six to seven times as dense as in the past, according to a 2022 study led by prominent fire scientist Malcolm North. As forests dry each summer, a process exacerbated by climate change, vegetation becomes vulnerable to the least spark, poised to rage into the catastrophic wildfires experts predict are inevitable without a dramatic increase in active forest management. If the Plumas burns, the 8,000 people who live in towns like Quincy, Graeagle, and Portola are in jeopardy—at risk of joining the thousands of us forced to evacuate Paradise, Greenville, and other Plumas communities destroyed by recent wildfires.

A Wild Billions investigation from Bay Nature and The Plumas Sun

manager of the Feather River Resource Conservation District. Because forests in the Sierra Nevada have evolved with fire, they depend on its power to clear out overcrowded trees and let in nurturing bursts of sunlight, to spur new growth. Black-backed woodpeckers, morels, grasses, ferns, and wildflowers all rely on periodic wildfires. A century of fire suppression has stymied this natural succession, creating overcrowded and decadent stands that have fueled the recent sequence of megafires. If we don’t deal with the threat such fires pose, the soil and seed banks that replenish forests will be destroyed, the trees replaced by shrubs and snags, Hall says. Some ponderosa and red fir stands will convert to oak and brush. Without active management, those will burn, too. “And then we’ve lost a forest,” he says. It’s a nightmare scenario that has jolted Forest Service officials into action.

Urged on by scientists, the Forest Service, and other natural resource agencies, Plumas Forest officials have launched a plan for a dramatic change in forest management. To mount it, they are using chain saws, drip torches, and an array of gigantic machines that include masticators, feller bunchers, grapples, and hot saws. The goal is to thin, log, and intentionally burn what experts say are unnaturally fire-prone forests. If their work can stay ahead of stand-converting flames, they hope to leave a vast swath of trees resilient to future fires. The project, which targets 285,000 acres of forest, is called Plumas Community Protection, and Congress in 2023 gave the Forest Service $274 million to carry it out.

This plan is visionary and ambitious but untested in scale. Its success depends on rapid accomplishment by a bureaucracy seldom known to be nimble, and now in the hands of an administration that has laid off thousands of workers and frozen millions of dollars of federal funds.

The forest also faces an existential risk, says Michael Hall,

Despite the high stakes, Forest Service officials have held few public meetings, refused to provide basic details of the project with reporters, and declined to review a summary of our findings. Bay Nature and The Plumas Sun reported largely without the help of federal officials, including public information officers who said they feared doing their jobs would end them. Instead, we interviewed 47 forest experts—agencies, nonprofit organizations, and community leaders—and mined public documents to piece together a picture of the Plumas Community Protection project so far.

These interviews have made clear that the funding, unimaginable five years ago, has been largely spent or obligated. Yet little on-the-ground work has been accomplished in the woods. The plan is already foundering.

Almost all of us who live in Plumas County can recite the recent fire sequence in chronological order starting in 2017: the Minerva,

Prescribed burns are essential to protecting forests from megafires, scientists say. But you usually have to reduce the flammable fuels first.

THINNING: Cutting down some trees and not others. Reduces forest density so it can be better managed by prescribed (intentional) fire. Suitable for landscapes with big “saw logs” that can be sold and for dense post-fire forests.

Cost: About $4,000/acre or $15,000/day, depending on equipment.

MASTICATION: A machine chews up vegetation. Another way of reducing fuel density before broadcast burns, especially with trees that can’t be sold. Suitable for brushy landscapes. Costs cannot be recovered.

Cost: $2,000–$3,000/acre.

BROADCAST BURNS:

Intentional fire that burns along the forest floor safely.

Removes fuel to tame future wildfires. High-risk, because it can escape, and hard to schedule. Highest impact and provides greatest ecological benefit to forests. But often first requires thinning, mastication, or logging.

Cost: $800–$4,000/acre. Also being affected by the current market.

PILE BURNS: People with chainsaws cut down vegetation, pile it, and burn it.

Low-risk and helps remove fuels, but many say it lacks the ecological benefits of broadcast burning.

Cost: $800–$8,000/acre. Demand and a glut of funding have distorted the market.

Since the Plumas Community Protection project got $274 million in 2023, much of the area is now covered by approved plans to thin, log, and burn. As of August 2025, intentional broadcast burns have been done on less than 1 percent of the target landscape.