BLACK BEARS | SAILING CARQUINEZ STRAIT | MUIR WOODS

Summer 2024 LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER

Resto R ation

In the Name of Eelgrass

Explore the curious connections of California. From towering redwood forests to vast deserts, breathtaking coasts to bustling cities, discover the surprising relationships among species, people, and places in our majestic state. A New Exhibit | Now Open | Get tickets at calacademy.org Every visit supports our mission to regenerate the natural world through science, learning and collaboration. 32660-CAS-State of Nature-Bay Nature Mag-7.625x10.25-05.10.24-FA.indd 1 5/10/24 3:16 PM

Since 1977, POST has preserved over 87,000 acres of open space for the benefit of all. You can help protect the land we love: © Teddy Miller PROTECTED FOREVER OpenSpaceTrust.org/ ProtectOurHome Lakeside Ranch Measure AA Hike Series Join Midpen Docents for the Celebrate the 10th anniversary of the passage of Measure AA by hiking with our naturalists Find out more at openspace org/events

2 0 1 4 O P E N S P A C E B O N D

Skyline Ridge Open Space Preserve (Alia Mousavi)

VISIT THE WORLD’S LARGEST MARINE MAMMAL HOSPITAL • Join a Tour • See Rescued Marine Mammals • Find Unique Gifts All in the Marin Headlands! ....Meet the Locals PLAN YOUR VISIT MarineMammalCenter.org/visit-bay

elkhornslough.org A haven for wildlife. A laboratory for restoration. A place for connection. at the heart of Monterey Bay Get to know Elkhorn Slough

Photo by Penny Palmer

features

WILDLIFE

Black Bears by the Bay Black bears are living in North Bay counties—Marin, Sonoma, Napa, and Solano— which may come as news to some. The bears have slowly moved in over two decades, spreading seeds and inhibiting deer populations, taking up the role grizzlies once filled. How does the Bay Area learn to live with them?

By Kim Todd

COMMUNITY

24

Eelgrass vs. Anchor-Outs

Eelgrass beds are home to young fish and tiny mollusks, an essential nursery for Bay life. The water above is home to a community of Marin County’s poor, some who have lived there for five decades. Could a healthy eelgrass ecosystem and anchor-outs coexist in Richardson Bay?

By Anushuya Thapa

PUBLIC FUNDS

32

Restoring the Peninsula (Sponsored)

A new preserve. Creek restoration. An 80-mile stretch of connected Bay Trail. All are examples of Measure AA funds at work on Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District lands thanks to voters who approved a $300 million bond in 2014 to be spent over 30 years.

By Austin Price, Katherine Irving, and Janet Byron

contents

ChristinaPrinn via iStock 18 SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 5 contents

A pair of black bears (Ursus americanus) living in Canada.

36 Bay a rea

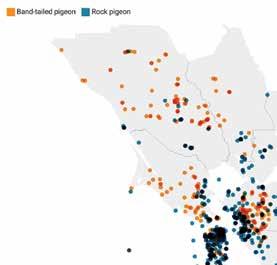

Overlooked for their ubiquity and present because we domesticated them, rock pigeons epitomize the remarkable urban nature we forget to wonder about.

By Lia Keener

39 San f ranci S co

A new beach, you say? Yes, sort of, China Basin Park includes a sprinkle of sand and expansive views of the Bay from China Basin.

By Guananí Gómez-Van Cortright

40 e a S t Bay

Just a half-mile-wide at its narrowest, a stretch of water, called the Carquinez Strait, connects the mighty Delta and San Francisco Bay. See it through the eyes of a sailor.

By Kate Golden

44 n orth Bay

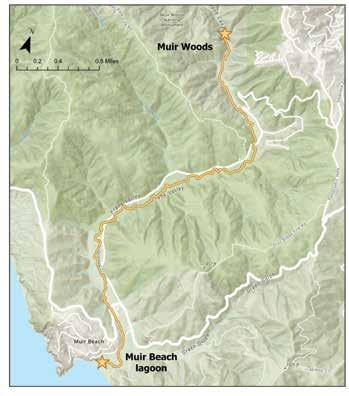

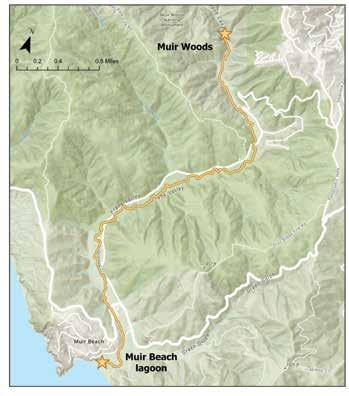

A turtle’s odyssey along the recently restored Redwood Creek, which flows through Muir Woods National Monument down to Muir Beach, signals success.

By Maya Akkaraju

40 17 from the field: 8 Contributors | 9 BayNature.org | 10 Editor's Letter departments THIS SUMMER 12 12 Almanac The invisible and unmissable 14 Signs of the Season Elder statesberry 15 The Human Animal Tomato summer 16 Nature in the Arts Signing off 17 Nature Jobs Branch manager 46 Naturalist’s Notebook Slug spotting 6 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG 36

EXPLORE

12

Clockwise from top left: Greg Clark; Kate Golden; Jane Kim

®

We host over 100 birdhouses in our vineyards to encourage biodiversity and provide a safe haven for wildlife.

p. 24 Anushuya Thapa joined Bay Nature in 2023 as a journalism fellow focused on Wild Billions reporting, Bay Nature’s project tracking federal money for nature in the Bay Area. A Kathmandu native, she sacrificed interesting topography for a four-year degree from Northwestern University, where she’d make escapes to Lake Michigan to stay connected to the natural world. Her work has been published on InvestigateWest and Crosscut. Outside the newsroom, she can be found dancing salsa decently well or playing chess very poorly.

p. 18 Kim Todd is the author of four books about science and history, including Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis and Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters.” For Bay Nature, she has written about city coyotes, white-crowned sparrow dialects, and urban osprey. Her work has also appeared in Orion, Sierra magazine, Smithsonian, and several Best American Science and Nature Writing anthologies. KimTodd.net.

p. 17 Gregory Clarke is a Los Angeles area illustrator and graphic designer, with a bachelor’s degree in fine art from UCLA. His work has appeared in the pages of the New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Wall Street Journal, and New York Times. He is coauthor and illustrator of the recent book A Sidecar Named Desire: GreatWriters and the Booze That Stirred Them (HarperCollins).

p. 24 Jacob Saffarian, born and raised in the East Bay, works as a science communicator. During his time as a marine researcher with UC Berkeley, he picked up his dad’s camera to help advocate for and share the amazing phenomena found in nature. From tropical marine biology to deep space observation, he pairs photography with science to bring attention to pressing issues and amazing wonders. Currently he assists at Wonderlab, a science communication studio in Berkeley.

p. 40 Kate Golden, Bay Nature’s digital editor, often reports on water—usually when it is scarce or polluted. But she is also a keen swimmer, angler, artist, and sailor who for three years lived on a small boat (a Nicholson 32) in the South Pacific. Previously, she produced award-winning data-driven investigations with the nonprofit Wisconsin Watch. Her reporting has been published in Sierra, the Washington Post, Atlantic online, and Hakai

p. 16 Matthew Harrison Tedford is an arts writer focused on ecology, history, and politics. He is interested in how art can inspire us to rethink our relationships with the natural world. Based in San Francisco, he has had work featured on KQED, Hyperallergic, in SF Weekly, and elsewhere. He is currently a doctoral student in the Visual Studies program at the UC Santa Cruz. MHTedford.com

Other contributors: Jane Kim (p. 12), Alison S. Pollack (p. 14), Endria Richardson (p. 15), Sadie Rose du Vigneaud (p. 15), H.R. Smith (p. 17), Austin Price (p. 32), Katherine Irving (p. 34), Janet Byron (p. 34), Guananí Gómez-Van Cortright (p. 38), Maya Akkaraju (p. 44), and John Muir Laws (p. 46). Front Cover: An oppalescent nudibranch cruises a blade of eelgrass in Monterey Bay. By Sage Ono

masthead, vol 24, no 3

summer 2024

e xecutive Director/Publisher

Wes Radez

eD itor in c hief

Victoria Schlesinger

D igital e D itor

Kate Golden

a rt Director

Susan Scandrett

managing eD itor

Alia Salim

outreach fellow

Lia Keener

journalism fellow

Anushuya Thapa

co P y e D itor

Cynthia Rubin

aD vertising Director

Micaelyn Compton

P roofrea D er

Dominik Sklarzyk

D evelo P ment manager

Barbara Butkus

Develo P ment a ssociate

Christina Jaramillo

m arketing & o utreach Director

Beth Slatkin

o ffice m anager

Jenny Stampp

i nformation technology m anager

Laurence Tietz

cofoun D ers

David Loeb, Malcolm Margolin

b oar D of Directors

Deonna Anderson, Wendy Eliot, Catherine Engberg, Nan Ho, Rebecca Johnson (president), Suzanne Moss, Anh Phuong Tran

v olunteers/ i nterns

Michelle Le, David Wichner

Bay Nature is published quarterly by the Bay Nature Institute 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710

Subscriptions:

$70.95/three years; $49.95/two years; $28.95/one year; (888)422-9628, BayNature.org PO Box 6409, Albany CA 94706

Advertising:

advertising@baynature.org

Editorial & Business Office: 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710 (510)528-8550; (510)528-8117 (fax) baynature@BayNature.org

Printed by Commerce Printing (Sacramento, CA) using soy-based inks and alternative energy.

ISSN 1531-5193

No part of this magazine may be reproduced without written permission from Bay Nature and its contributors. © 2024 Bay Nature

8 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG FROM THE FIELD |

Kim Todd: Dani Werner

A CliC k A ble Fe A st

Voracious readers, satisfy your cravings with new stories each week at BayNature.org. Get great reads, events, and places to explore in our weekly newsletter: TinyURL.com/BayNatureNews

» Grants Delayed for Forest Communities

A “game-changer” of a new U.S. Forest Service program to help disadvantaged communities reduce their wildfire risks has been plagued by long delays—in part because the agency is so understaffed, Anushuya Thapa finds.

» Predator of the Pools

Reader Dan Osipov got some rare closeups of the gorgeous Delta green ground beetle, which is a bit of a mystery, even to experts, Kate Golden writes.

» Snake Fungal Disease Is Spreading

This emerging infectious disease has popped up in way more California species and places than expected—but surveillance funding is running out. Anton Sorokin writes about how you can be a friend to snakes.

California State University East Bay’s Concord campus is growing a garden for Indigenous stewardship and storytelling, in an EPA-funded collaboration with Berkeley’s Cafe Ohlone. From Anushuya Thapa. Our reporting project exploring the impacts of big federal money

» An Indigenous Garden Takes Root

» Something Borrowed, Something Blue

The Xerces blue, long gone from San Francisco, became a symbol of the fight against extinctions. Now scientists are sending in a replacement, the silvery blue, to the Presidio dunes. Will it take?

H.R. Smith goes butterfly road-tripping.

» The Ginger Badger of Point Reyes

Young wildlife photographer Vishal Subramanyan writes about his quest to find an unusual badger.

FROM THE FIELD | BAYNATURE.ORG

on our area

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 9 Clockwise from top left: Bear, 1827photo via iStock; courtesy of Feather River Resource Conservation District; Dan Osipov; Anton Sorokin; Vishal Subramanyan; Gayle Laird, California Academy of Sciences.

Costs of Conservation

A ye A r A go, Bay Nature launched a reporting project that we’ve dubbed “Wild Billions” to follow federal money flowing into the greater Bay Area for nature-based projects. No doubt you’ve noticed our flashy project logo. As of May 2024, roughly $1.2 billion has been allocated through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to the slice of projects we’re following. And with Bay Nature ’s summer issue, we will have reported about the money in 19 stories, all of which can be read online.

When Bay Nature’s digital editor, Kate Golden, and I reported last year on the challenges of spending the rush of federal funds, we spoke with Rebecca Schwartz Lesberg, who is deeply involved in Bay conservation and is vice chair of the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. She made a point that stuck with us. “A lot of our conservation projects are intertwined with other social issues like housing affordability. The funds that are there for strictly conservation can’t be used to deal with the other social issues that are standing in the way of implementing conservation.”

Based on that conversation, we began reporting on a $2.8 million grant from the EPA, made possible through BIL, for eelgrass restoration where an impoverished anchor-out community lives in Marin County’s Richardson Bay. Schwartz Lesberg’s company is the recipient of the EPA money, and it made possible a matching state grant of $3 million for housing roughly three dozen of the anchor-outs. We didn’t know where the reporting would lead us, but as Bay Nature reporter Anushuya Thapa asked basic questions, the complexity of the story grew.

The result is an in-depth and nuanced exploration of eelgrass ecology and conservation, living in poverty on the water, and, importantly, how environmental groups and the cities surrounding Richardson Bay achieved their goals.

This was a difficult story to report and to publish. But we dug in because other media outlets haven’t. And while Bazy Nature is first and foremost an environmental science magazine, we know many of our readers care deeply about inequality in the region and housing affordability. A community that champions and identifies itself with the environment deserves a full picture of how conservation and homelessness can clash in the Bay Area.

—Victoria Schlesinger Editor in Chief

—Victoria Schlesinger Editor in Chief

10 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG FROM THE FIELD | EDITOR’S LETTER

Clockwise from top left: Barbara Butkus; Ross Macdonald; © angelmoo963, some rights

reserved

(CC-BY-NC)

via iNaturalist

Online

Wild Billions articles

p. 24

Eelgrass p. 18

Black bears

Vegetable Blend, Nursery Mix, Potting Mix, Essential Soil Landscape Mix, Green Roof Mixes, Bioretention Soil Mixes, Diestel Structured Compost OMRI, Garden Compost OMRI, Biodynamic Compost CDFA, Organic Aged Humus CDFA, Premium Arbor Mulch, Fir Bark, Mocha Chip, Mahogany Mulch, Ground Redwood Bark, Actively Aerated Compost Tea, Mycorrhizal Fungi,

Birdfeeding Supplies & Binoculars

California Flora Nursery Located in

Specializing in growing California natives THE WAT E R S H E D N URSERY 10% off your next purchase of California Native Plants with this coupon 10% OFF THE W ATERSHED N URSERY 601 Canal Blvd, Richmond, CA 94804 www.TheWatershedNursery.com lyngsogarden.com / 650.364.1730 345 Shoreway Road, San Carlos Mon – Sat: 7 to 5, Sun: 8 to 4 Lyngso

Garden Books, Tools, Seeds From Whales to Bobcats, Experience Bay Nature Talks @ baynature.org/ bntalks Robb Hannawacker, CC0 1.0 DEED

Off Hwy 101 in Novato (415) 893-0500 wbu.com/marin

Sonoma County, north of Santa Rosa in the town of Fulton calfloranursery.com • 707-528-8813

Down to Earth Organic Fertilizers, Fish & Kelp Emulsion,

Life in Summer

… is full of some happenings that are enigmatic or unnoticed, and some that can’t be unseen.

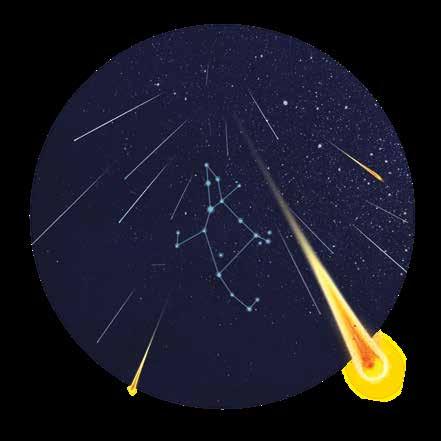

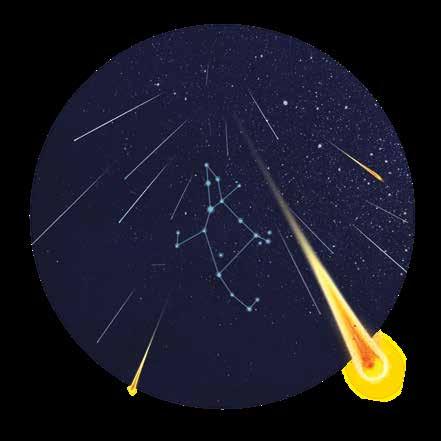

f laming du S t

The Ohlone and Pomo believed that mete ors were objects of fire, dropping from heaven, according to notes by ethnologist J.P. Harrington. When you strip away all that humans have learned in the last cen tury about meteors, fire dropping from heaven is still a pretty good summation of a meteor shower. And one of the year’s finest happens in summer. When Earth swings around through a trail of floating debris left by the chunky, 16-mile-wide comet Swift-Tuttle, we watch the Perseid meteor shower pour from the dark night. These abandoned bits of dust fly through our atmosphere at 133,000 mph, heat up to 3,000 degrees, and vaporize. What we see is the light from that heat, some 50 to 100 times per hour.

This Year's Spotlight: the Night Sky

The show of fiery meteors peaks on August 12 and 13 and will be most visible after the waxing moon sets, between midnight and dawn.

It’s hard for a puppy-eyed Pacific harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardii) to be anything other than adorable. Except maybe when it is molting. June and July are the peak months for harbor seals along Bay Area shores to shed large strips of fur to reveal a sleek new coat underneath. The process can look a little troubling—ragged patches of sometimes bronzy-colored fur overlaying silvery gray. But the seals are all good. They just ask for extra privacy and distance while they make the annual, energy-intensive wardrobe change.

A paragon of patience, that’s what the Western wood-pewee (Contopus sordidulus) is. Perched on a high and open branch, this small flycatcher waits and waits until its prey—perhaps a crane fly, beetle, or moth—sails by. Then the bird darts out, snags a meal, and usually returns to the same spot to eat. The behavior is recognizable, so if you too are the patient type, look for wood-pewees in Bay Area forests this summer. They’ll be here raising their chicks before heading to South America in the fall, exactly where no one knows.

12 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG THIS SUMMER | ALMANAC

ILLUSTRATIONS BY JANE KIM

Western wood-pewee

Pacific harbor seal

Angular-winged katydid

o ver S ized S unnie S

We don’t body-shame at Bay Nature, but it’s hard to write about an ocean sunfish ( Mola mola) without noting that it appears to lack a body, which is really alarming the first time you see this ocean colossus. Measuring up to 10 feet and weighing up to 5,000 pounds, this all-head creature is arguably one of the heaviest bony fish in the sea, and it can be found off Bay Area shores and beyond year-round. In summer, these fish bask and warm themselves at the water’s surface in Monterey Bay, or hang out around floating kelp paddies.

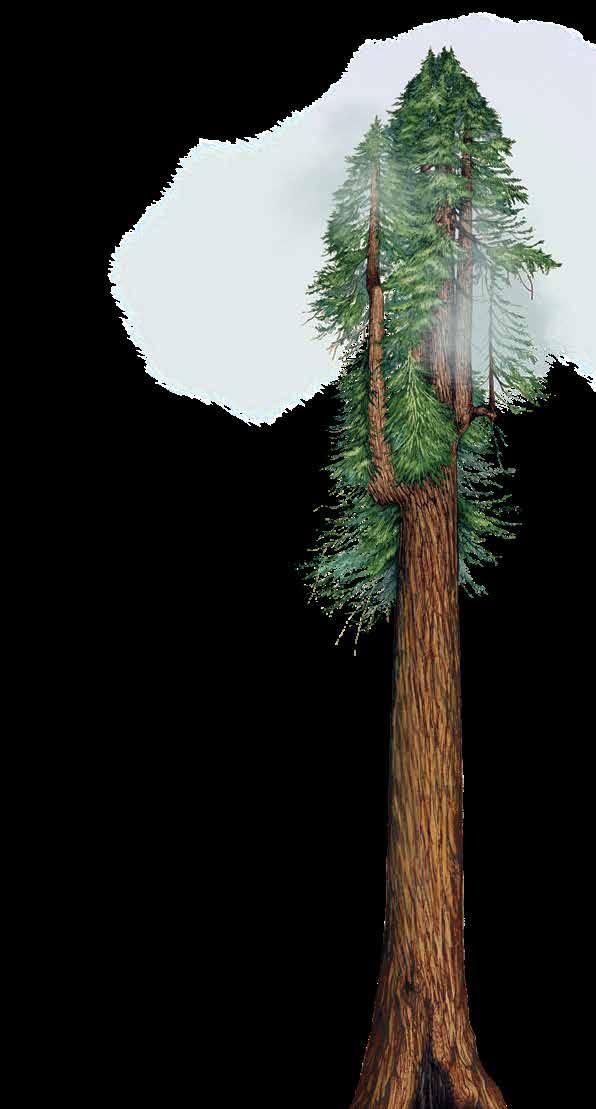

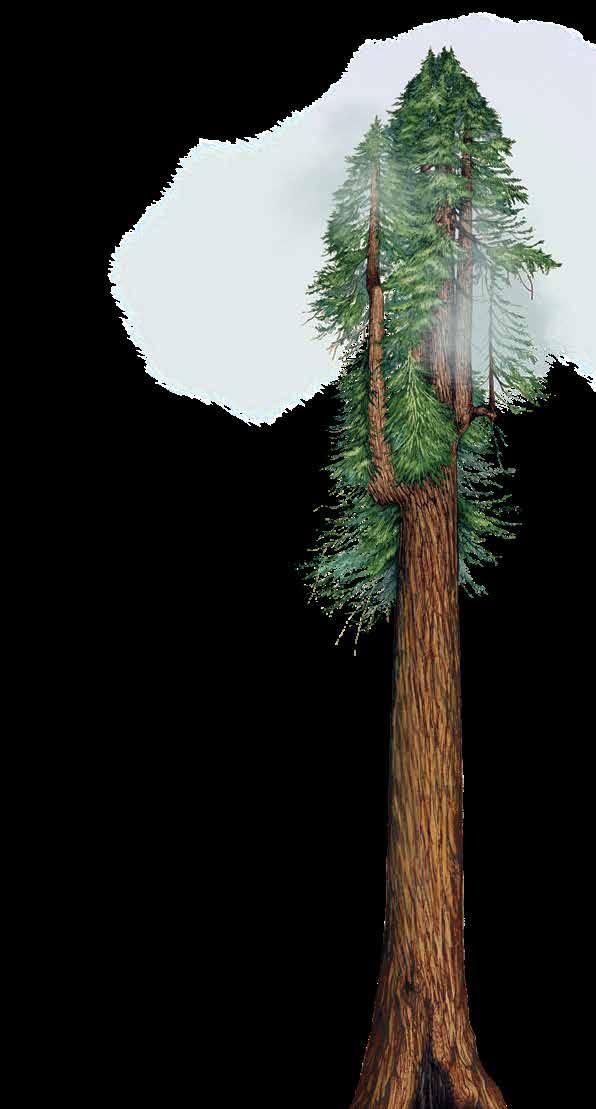

t ree fog

While sitting in the shade of a coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) during summer, consider this fascinating plant process: The redwood is emitting terpenes, compounds that contain the odor of the redwood. When the terpenes react with the air, they form tiny particles that can become the condensation nuclei, or seed, for fog, according to chemist and environmental scientist Allen Goldstein, a professor at UC Berkeley. Most of the fog in redwood forests exists thanks to the temperature difference between the ocean and the land, but the redwoods can contribute a little bit too.

Summer roman C e

On a warm, late-summer evening in the Bay Area, listen for a metronomic tsip, tsip, tsip and a more rapid tick-tick-tick, like two pebbles tapped together. Made by the male angular-winged katydid (Microcentrum rhombifolium), the first sound may be a warning to ward off other males; the second, his serenade. A female will call back with a lower-intensity ticking, and eventually they’ll meet amid the tree canopy. All this so that he can present a nuptial gift—a package of sperm, along with a blob of nutrient-rich, gelatinous food, which she’ll eat instead of his sperm packet. So many ways to love.

Coast redwood

Ocean sunfish

RESEARCH AND WRITING BY BAY NATURE STAFF

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 13

Elder Statesberry

We don’t have a California state shrub yet, but the blue elderberry (Sambucus mexicana … usually) ought to be a top contender for the honor—for its beauty, versatility, and importance to California’s natural and cultural history. It’s an overachiever.

Of the three species of elderberries (sometimes called elders) that grow in California, the blue elderberry is the most widespread and prevalent, gracing hillsides and stream banks all over the state. Anywhere water flows nearby, really.

Blue elderberry may be a small shrub— or grow as tall as 30 feet. A student once asked me about the difference between a tree and a shrub, sending me into a deep philosophical spiral, until I learned trees generally have a single thick trunk, while shrubs tend to have many thin stems— which aptly describes the elderberry’s numerous straight stems. Blue elderberry has serrated, skinny leaves, usually a shiny dark-green, that form a symmetrical pattern. But in summertime the go-to identifiers are the clumps of cloudy blue berries weighing down its branches in heavy skeins. (Also fruiting then is red elderberry, Sambucus racemosa, which has shock-red berries.)

Berries are preceded by lacy bunches of white flowers in spring that release a rich aroma, a bit like a subdued jasmine. At least 23 species of butterflies and moths likely feast on the nectar and pollen. Other insects known to frequent elderberries include tiny, slender winged insects called thrips—the thought of which may make gardeners shiver, as some hungry species leave silvery scars and curling leaves in their wake on other plants. Fear not: thrips have been documented not only pollinating elderberries but increasing their fruit output. If you find yourself in the Central Valley, look for small holes in elderberry stems—signs of the endangered valley elderberry longhorn beetle, which lives its whole life on the plant.

Many birds are huge elderberry fans. After passing through

a scrub-jay, flicker, or bluebird, a seed’s adventure is just beginning. It’s a patient but particular seed, waiting under the protection of a hard coating for the right conditions. It may remain viable for over a decade.

Native people throughout California have long known about the plant’s exacting germination needs and used fire to stimulate its growth. Gentle fire cracks that hard outer seed coat. Once conditions are just right, the plant takes off. It can reach full size in as little as three years!

The Sambucus genus is likely named for the sambuca, an ancient musical instrument from Asia; elderberry stems are still made into clapper sticks, flutes, and whistles.

The array of Indigenous uses for elderberry, throughout California, is as impressive as the plant’s growth rate. The berries dye baskets, and the branches can make clapper sticks (one Pomo elder told me that elderberry is where the music is stored). Historically, Pomo people along the coast used the plant’s flowering and fruiting to time shellfish gathering. Sage LaPena, a Tunai Wintu and Nomtipom ethnobotanist,

says, “Elderberry is one of our most important traditional medicines, and we’ve never stopped using it.” Many Indigenous groups use elderflowers in a fever-reducing tea or in baths to induce sweating.

The next time you’re in the cold and flu aisle of a pharmacy, look at the ingredients of natural cold medicines, and you’re certain to find many that include Sambucus. The plant can be an effective antiviral, antibacterial, antidiabetic, immune-booster, and anti-inflammatory and a powerful antioxidant, according to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s integrative medicine website.

At Berkeley’s Cafe Ohlone, the Indigenous chefs Vincent Medina and Louis Trevino have used elderberry sauce to balance out a meatball stew as a fine cooking wine would do, soaked quail eggs in elderberry tea, and paired elderberry jam with chia pudding. Recipes for elderberry syrups, jellies, and more are easy to come by online, along with elderflower cordials and liqueurs.

But don’t devour those berries raw. They can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, due to cyanide-containing chemicals that can be destroyed with heat. And if you plan to harvest, please do so responsibly. Don’t take more than you can use, and gather no more than about 10 percent of material from an individual plant, as a rule of thumb.

The elderberry genus provides endless intrigue for armchair taxonomists. Blue elderberry has three scientific names—Sambucus mexicana, Sambucus caerulea, and Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea. Recently, elderberries have been shifted from one family (honeysuckles) to another (Viburnaceae). Some say the genus has been oversplit into more species names than there are species—maybe because it’s so variable in its growth forms, patterns, colors, sizes, and geographic range. You might say the elderberry is too iconic to be contained by categories—though science will keep trying its best. ◆

Alison S. Pollack

Alison S. Pollack

14 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG THIS SUMMER | SIGNS OF THE SEASON

Alexander S. Kunz

Under the Skin

It is early summer in Oakland, which means that soon I will be able to get my hands on as many tomatoes as I want. I will eat them with olive oil and salt. On salads. As sauce. The farmers market is only a few blocks away, and I will walk there with a two-gallon tote. This, even though I know what comes of tomatoes in my orbit. Most of my tomatoes will go, I admit, guiltily, uneaten to the back of the fridge. Eventually, eating them will become a kind of punishment for excess. A daily confrontation with sweet, exuberant abundance and its other side—greed, waste—and my complicity in it all. How can I not sink myself, elbows deep, into the luscious tomato in its season?

It is not that I take tomatoes for granted. I was visiting my East Coast family during winter break, and was making salad for dinner. My sister had a pint of cherry tomatoes. I bit into one of the small, hard, pale things. I spat it out. It was sour and watery, with a faint chemical aftertaste. “Your tomatoes have all gone bad,” I told her. “There is something terribly wrong with your tomatoes.”

She ate one. “This is what tomatoes taste like. You have been on the West Coast too long.”

My first summer in Oakland, years ago, a new neighbor offered to help me plant some tomatoes. I had just finished law school and begun a fellowship with an advocacy organization led by formerly incarcerated people. We were co-counsel in a lawsuit, Ashker v. Brown, part of a larger protest movement against solitary confinement that began in 2011 with a series of hunger strikes. A movement to remind us on the outside about food and resistance, food and freedom. I wanted to connect with food in this new home of mine—a place of wealth and abundance, protest and prisons—and I thought growing a garden could be a way to do that.

We planted a handful of seeds in my backyard, between the angel’s-trumpet and the tree collards. Not everything that we planted survived. But some weeks later, I saw pale green buds with yellow flowers. Then hard green globes. Red and orange fruit! Anyone who has grown their first edible plant knows that no tomato will ever be as delicious as those tomatoes. Food and resistance, I thought, might be as simple and sweet as growing your own tomato plant.

But there is growing a handful of tomatoes, and then there is growing tomatoes. I worked for a few seasons as a market hand for Riverdog Farm. In late July, after dozens of farmworkers planted and harvested, then packed produce onto the truck, we would need extra helpers just to unload tomatoes: Early Girls, Sungolds, Gold Nuggets, Brandywines, Marvel Stripes, and Green Zebras. At the end of the night, the lot was slippery with squashed tomatoes, and the farmer would rumble home, to begin again at dawn.

These luscious tomatoes are the descendants of blueberry-size wild tomatoes from South America. They were domesticated likely in Mexico before being brought, probably by Spanish merchants and colonists, to Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, and to North America by the 18th century. By the 1970s, California farms were producing 80 percent of tomatoes grown in the United States. Today, those farms are still worked for low wages, under harsh conditions, by people who have migrated north from Mexico and Central America.

These inbred domestic tomatoes, even our beloved local heirlooms, have lost many of the genes belonging to their wild cousins. As a result, they can be more vulnerable to disease, drought, pests, and other climate change impacts. This makes farmers’ work ever more difficult and tenuous. Tomatoes are sweet, yes. But the tomato industry is relentless.

This is all to explain, to excuse, to justify myself each summer when I yearn for bucketfuls of tomatoes that I could not possibly eat. It is that I yearn to hold large unwieldy systems, within a space small enough to feel them.

Tomatoes are the works of days and hands and places I can never fully touch. But I can touch the lone tomato. Better, I can touch tons of tomatoes. I can hold them in my arms, I can tuck them into my mouth. I can try to turn them into something else again—a body, life, reckless abundance. ◆

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 15 THIS SUMMER | THE HUMAN ANIMAL BY ENDRIA RICHARDSON

Sadie Rose du Vigneaud

Look Here

A farewell from our arts columnist.

“H

umans are too big,” Mill Valley–based artist Sarah Bird told me, paraphrasing the philosopher Donna Haraway, in a 2019 interview for this column.

“We’ve consumed too many of the resources of the rest of our web of being.” Bird hoped to comment on human overconsumption by projecting a photograph of a redwood tree somewhere in the urban environment—at full scale.

One night this April, Bird achieved it. A glimmering visage of one of these giants appeared, for 90 minutes, on the San Francisco Ferry Building’s 245-foot-tall clock tower. Temporarily, Bird brought together the architectural and the arboreal. Bird isn’t trying to replace our experiences in the forest. Rather, she seeks to give us an additional perspective; it is difficult to experience the whole of a redwood from the forest floor. But Bird lets us glimpse the tree’s immensity. Perhaps humility or awe follows.

Bird’s drive to shift her viewers’ perspective has been a recurring theme in the dozens of conversations I’ve had with visual artists, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, and architects since this column launched in 2018. Through their work, I saw how art can transform our understanding of the natural world, or our relationship with it. In this final installment of the column, I look back at some of the art that stayed with me.

Many of these artists compel us to reexamine the present more carefully. One of my first interviews was with artist Tanja Geis, who also holds a master’s in marine and coastal management and makes place-based video art, drawings, and sculptures, often focused on marine environments. Geis argued that while scientific data often doesn’t result in changed behaviors, art can help us pay attention to the world, thereby transforming our perspective or helping us empathize. Musician Cheryl E. Leonard, who plays rocks and shells as instruments and records the sound of thawing lakes, hopes that her music encourages listeners to slow down and attend to nature’s music around us. In these examples, art is a beacon or a magnifying glass— choose your metaphor—that highlights the treasures around us.

This kind of attentiveness takes

time to bear fruit. Musician Ellen Reid worked with Kronos Quartet and other musicians to create Ellen Reid SOUNDWALK, a GPS-enabled app (available through June 2024) that plays location-specific music as one walks around Golden Gate Park. The result is a unique soundtrack tailored to one’s own walk through the park. Thinking of Golden Gate Park as a work of art, Reid says the app can help people slow down so that they can “see more of the details of the existing work of art.”

Others make art and architecture that look toward the future. Researchers at California College of the Arts and Moss Landing Marine Laboratories created the Buoyant Ecologies Float Lab, an experimental vessel tasked with addressing sea level rise. The undulating vessel, about the size of a small car, gives researchers insights into how underwater fouling communities—invertebrate hangers-on that attach themselves to the lab—can help absorb and dissipate energy from waves during storms. The Float Lab seeks a vision for adaptation driven by creative design. These researchers ask how design can make coastal communities safe in the future.

In her 2022 exhibition at the Marin Museum of Contemporary Art in Novato, Elisheva Biernoff demonstrates how art can aspire to the utopian. Her interactive exhibition gave visitors the opportunity to imagine their own vision for a local wetlands restoration project—letting them move magnets of local flora and fauna, or agricultural and architectural elements, around on the landscape. By providing the elements of a potential environment, Biernoff makes a case for democratic participation in restoration and land use.

Lectiossiti odio eatum nobit earibus iunt periand andam, quiasit, cotktkn re, te nes magnatquid

These artists recognize that art alone is not enough to heal our planet and communities. Art is nonetheless limitless in its power to reorient and inspire. In her bold abstract landscape paintings, African American painter Shara Mays honors, and reimagines, her ancestors’ relationship with the land. In her work, art and nature come together to envision the conditions for a better world. She told me that “by painting landscapes, I was paying homage to the people in my life who deserve transcendence, beyond the limitations of racism that they faced when they were alive.” Mays described painting as an act of freedom in itself. “I have no restrictions in my practice, and that’s because this is my space.” ◆

Matthew Harrison Tedford

Sarah Bird

16 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG THIS SUMMER | NATURE IN THE ARTS

Branch Manager

Tree-trimming is art, done with chainsaws.

Left to its own devices, a tree will prune itself. It will ruthlessly drop lower branches in the quest to harvest maximal sunlight and will deaccession large chunks of personal real estate during times of botanical crisis. In cities, which teem with soft humans and their crushable objects, tree pruners (who focus on tree health) and trimmers (who also serve the gods of aesthetics) mediate between a tree’s goals and the community at large.

The best part of pruning is the trees, says Joe Lamb, who has been doing it ever since he was a film student at San Francisco State in the 1980s. Back then, the work was “a temporary thing, just to stay alive.” But the architecture of trees proved endlessly fascinating, as was the problem of how to edit them. Up in a tree, you can often only see the branches right in front of you. The ability to extrapolate from those branches to the whole of an entire tree is both a skill and something that can’t entirely be taught. Another best part: the coworkers. In some countries, becoming a professional tree trimmer is preceded by years of training in arboriculture. In the U.S., for better or worse, it may be preceded by someone asking you if you think you could prune that tree. This low barrier to entry and a not-awful hourly wage attracts people across lines of race, class, culture, and language (fluency in Spanish is helpful). Coworkers may be arborists, college kids, or people sans formal schooling. Some trimmers migrate on to more lucrative, less physically demanding jobs in urban forestry. Others, like Lamb, stay for decades.

It’s dangerous work , shimmying up a tree and spending hours up there with nothing but a chainsaw for company. The loosey-goosey safety practices of Lamb’s youth were supplanted years ago by more rigorous protocols, but Lamb has hearing aids in both ears due to youthful inattentiveness to ear protection. People who stick with the job are the kind who look out for others—if you’re the one up in the tree with

the saw, you’re also the one who gets your lunch hoisted up so you can eat your sandwich with the birds and squirrels.

The worst part of trimming is the people who fight over trees. Lamb is occasionally brought in to trim when one neighbor sues another whose tree is blocking a view of something said neighbor would like to look at. Feelings ride high when parties might be spending six figures in legal fees. Lamb likes his clients to be happy. But, he says, “at the end of a view pruning, usually you’re successful if both people are unhappy, because you’ve had a meeting between their extreme desires.”

To be a tree pruner, says Lamb, start pruning trees. Look for entry-level jobs like “groundskeeper.” Jobs are plentiful, and likely to increase with the $42 million worth of tree cover coming to the Bay Area

via the Inflation Reduction Act . Much of that money is aimed at low-income areas where trees have been on the decline , despite their proven ability to improve local air quality and keep temperatures down. “As everything starts heating up, it’s going to be critically important to keep our urban forests healthy,” says Lamb. “It’s a beautiful profession I think people should consider.”

—H.R. Smith

GETTING STARTED

Pay is $20–$40 per hour depending on skill, perhaps more if you own the business. Work requires comfort with heights, power tools, and physical labor; diplomacy is a plus. Courses in arboriculture, like at City College, Merritt College, or Foothill, can be a good way in.

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 17

THIS SUMMER | IT GETS ME OUT Greg Clarke

18 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG FEATURE | TOP OMNIVORE

A black bear (Ursus americanus) in Kings Canyon National Park, California.

by the

BearsBlack Bay

For the first time in history, black bears are living in North Bay counties, occupying an ecological niche once filled by grizzlies.

by kim todd

On a gray early March morning in Sonoma County, everything is dripping. Somewhere, out of sight, in hollow trees and rocky caves, tiny American black bear cubs nurse in the dark. Born at less than a pound only a few weeks before, they won’t emerge until spring. But adults—ones that haven’t given birth this year— might be out and about, turning over logs, poking at anthills. In this temperate climate, coastal bears don’t hibernate like their high-country cousins. Food is plentiful all year round; there’s no need to sleep away the thin months.

So even in early spring, snow still deep in the Sierra, we are hoping to see one.

The road up the mountain at Sugarloaf Ridge State Park is washed out. Meghan Walla-Murphy, an ecologist and expert tracker, hops out of the ATV where the pavement ends and starts looking for evidence indecipherable to a novice. Signs might include bear scat laced with grass, saplings with the tops snapped off, trunks that have been used as back scratchers. They are hard to see: camera traps have captured hundreds of images, but park manager John Roney says there have only been five in-person sightings. Walla-Murphy inspects the post of a barbed wire fence. Nothing.

A little farther, a power pole tilts at a steep angle. Here, the wood is battered, marked by deep, horizontal gouges. “All of this is bear scratch marks, bear claws,” Walla-Murphy points out to me. Bites, too, she thinks. Brown hairs are stuck in the splinters.

A decade ago, bears were a rare sighting in the North Bay. When a wildlife camera, newly installed near staff housing in the park, recorded one ambling by, it was thought to be a wide-ranging individual just passing through. Then, one August night in 2016, the camera caught not one, but three pairs of glowing eyes. Animals took shape—round ears; long, low back. Clearly, Ursus americanus. The mother bear neared, then veered off camera, closely followed by a second, much smaller, while the third, a lollygagger, stopped to inhale some scent in the dirt. The family indicated

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 19 Floris van Breugel via Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

bears were not visiting but living in the park.

In response, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), state parks, winegrowers, ranchers, the California Indian Museum and Cultural Center, the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians, and others formed the North Bay Bear Collaborative to learn more about the newcomers and plan for their arrival. Walla-Murphy is the lead scientist.

Throughout the Bay Area, black bear sightings are increasing.

Last summer, a black bear stopped in the front yard of a San Rafael home, sniffing a garbage bag, raiding the strawberries. Another wandered a sidewalk in Larkspur. Three years ago, a black bear climbed an oak in San Anselmo, licking its paws and drawing a crowd in midday.

It’s part of a trend all over the country: bears venturing into small towns and suburbs. They are hibernating under Connecticut decks and swimming in backyard pools in New Jersey. In one surreal occurrence, last year a black bear climbed a tree in Frontierland in Florida’s Disney World, a real wild animal exploring a fake version of the “Wild West.”

In January, one found its way into Sallie Miller’s yard, tucked between the road to Sugarloaf Ridge and roaring Sonoma Creek, forested hills rising on either side. Returning home, Miller found her beehives smashed, wood frames scattered on the pavement. She’d seen scat on the lawn, but this raid was a different level of interaction.

“There were live bees everywhere,” she remembers. She and her husband cleaned up and went out, only to come back to find the bear had been back, making even more of a mess this time. “It was probably just hanging out on the hill, watching us,” she says.

Finally, they moved the remaining hives right by the house, thinking the bear wouldn’t venture so close. But they woke at 1:30 a.m. to find a bear in the carport. Banging pots and yelling got it to flee, and not long after, rains swelled the creek. “It hasn’t been back,” Miller says. But the trees on the other side of the water connect to 12,000 acres of public lands and large estates with few people: good bear country.

Much remains a mystery. What led to increased numbers? Maybe the bears are spreading from bear-rich counties like Mendocino as the overall bear population in California grows, up from between 10,000 and 15,000 in the early 1980s to roughly 65,400 today (though it is hard to compare precisely, as counting methods have changed). Maybe it’s a response to humans building deeper into wildlife habitat in the North Bay. Or it could be the recent catastrophic wildfires. Climate change alters the availability of food, from seeds to ants to trout, possibly pushing bears closer into the suburbs.

Whatever the cause, how will this influx of large omnivores affect the ecosystem of the North Bay?

A black bear (Ursus americanus) in Kings Canyon National Park. In one surreal occurrence, last year a black bear climbed a tree in Frontierland in Florida’s Disney World, a real wild animal exploring a fake version of the “Wild West.”

“Black bears are common and well-studied everywhere and we still know so little about them,” says John Roney, park manager at Sugarloaf Ridge.

In an effort to answer some of these questions, starting this summer CDFW will satellite-collar bears in Marin, Sonoma, Napa, and Solano counties, aiming for eight males and eight females. Biologists will document where the bears are roaming, where they are crossing roads that might put them in danger, the location of den sites. Then, by placing cameras on dens, they will estimate numbers of cubs.

“It just seems like it’s a good time to study this species,” says Stacy Martinelli, the environmental scientist for CDFW running the satellite collar study. “It’s such

a big, charismatic, wonderful animal.” As they move south, though, toward the San Francisco Bay, the bears will eventually run out of forest and, increasingly, into people. “The more that we’re in their space, there’s an increased likelihood that we’re going to encounter them,” Martinelli says. More knowledge may keep trouble at bay; if the state knows the bears’ travel routes, for instance, it can work with landowners and Caltrans to develop wildlife corridors.

In addition, ongoing DNA studies by the North Bay Bear Collaborative, where volunteers collect scat and send it to a lab at UC Davis for analysis, will suggest numbers of individual bears, genetic relationships between them, and where they are coming from. Estimates based on these studies put about 70 individual black bears in Napa and Sonoma counties, with two or three in Sugarloaf Ridge State Park. Marin County results will be available later this summer.

One clue to how the black bear might fare in the region comes from the past. The Bay Area used to be teeming with bears, but most weren’t black bears. They were California grizzlies. Reports have them running down a hill on the Peninsula, pacing near Strawberry Creek in what would become Berkeley, leaving tracks at Mount Diablo. Nineteenth-century zoologist C. Hart Merriam divided the California Grizzly into seven subspecies, three of which met at San Francisco Bay: the California Coast Grizzly, the Tejon Grizzly, the Klamath Grizzly. (Now all grizzlies are thought to be the same subspecies of brown bear: Ursus arctos horribilis.) The final wild California grizzly was seen 100 years ago, in 1924, by a cattle rancher near Sequoia National Park. “It was the biggest thing I ever saw— bigger than any cow, and looked as though sprinkled all over with snow,” claimed Alfred Hengst. Black bears, who never lived in this area historically in any abundance, are just walking in their mighty footsteps.

While grizzlies still roamed the state, most black bears near San Francisco were likely captives. An ad in the San Francisco Examiner in 1888 read, “Wanted—A BLACK BEAR CUB, NOT more than one year old; must have fine coat and be gentle.” An Oakland Post Enquirer article from 1928 announced

20 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG FEATURE | TOP OMNIVORE

“Rampaging Bear Gets New Owner” and told the story of 5-month-old Betty, “probably the only bear in Berkeley that is not a football player,” who escaped. She knocked over a bunch of trash cans and was then adopted by the police officer who tracked her down.

Black bears are smaller and shyer than grizzlies. They love the forest while grizzlies prefer open meadows and chaparral but, in ways, they play a similar ecological role.

Omnivores, black bears eat voraciously and expansively, everything from cow parsnip roots to yellow jackets to clover. In Florida, bold ones go after alligator eggs. In California vineyards, refined ones graze on pricey grapes. Though they don’t often hunt large animals, they will take available meat. One wildlife camera at Sugarloaf, trained on a dead deer, caught a bear swiping it like it was shoplifting jeans at the Gap and then disappearing into the woods. And, if they can find them, they dine on half-eaten peanut butter sandwiches, granola bar crumbs, cold French fries.

In this, they are like the grizzly, of whom

and sign: A good example of a black bear’s right front paw track; black bears claw at tree trunks, sometimes scraping away the bark; piles of their sometimes-tubular shaped scat changes in appearance with the bear’s recent meal; black bear fur can range in color from white to cinnamon to black and most shades in between.

John Muir commented, “To him, almost everything is food except granite.”

Bears are fierce and curious, clumsy yet graceful. (Some words just seem made for bear movement—”amble,” “lumber.”) With a roughly human shape and larger-than human size, they inspire affection and fear. As a result, bears are embraced symbolically (see: teddy bears) but often are not tolerated in actuality (see: the extinction of the California grizzly). Grizzly Peak Boulevard, Bear Valley in Marin, Grizzly Island in Suisun Bay—bears’ power lingers in names and pictures even when the animals are absent. Nowhere is this clearer than on the UC Berkeley campus. Here bears are everywhere: bear statues, bears on T-shirts, bears on notebooks. The California state flag, with its big grizzly, flies over it all.

The Bay Area has seen a wave of new and returning species in addition to bear in recent years: osprey, peregrine falcons, gray fox, coyotes. Though we might not know the exact reasons, the influx is no mystery at all, according to Christopher Schell, a UC Berke-

ley ecologist who studies urban carnivores.

“Most cities, like this one, are situated on purpose on top of biodiversity hotspots,” Schell says. As if to underscore his point, a hummingbird darts outside the second-story window of his office, between a eucalyptus grove and redwoods along the creek. Animals of all kinds are attracted to spots with plentiful water, fertile soil. “We need the same types of resources that many of these other species need.”

And when carnivores come in, they change the landscape around them. This effect is called the “landscape of fear.”

“Having bears or pumas or wolves on the landscape dictates where deer go,” Schell says. For example, one study showed that west of the Sierra Crest, where large populations of black bear prey on mule deer fawns, fewer deer migrate to that bear-dense summer range. Deterred from the west side, many feed on the east side instead. Changes in deer behavior like this have far-reaching results. “They’re not going to overgraze on native plants and vegetation. And if they

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 21 Clockwise from top left: © omarfpena, some rights reserved (CC-BY-NC) via iNaturalist; © Kyle C. Elshoff (he/him), some rights reserved (CC-BY-NC) via iNaturalist; © nescaladahsu, some rights reserved (CC-BY-NC) via iNaturalist; © angelmoo963, some rights reserved (CC-BY-NC) via iNaturalist

Track

don’t do that, then the native plants and vegetation can sustain a greater diversity of birds, which can then eat and sustain a greater diversity of invertebrates.”

A broad diet and wandering ways make black bears and grizzlies important seed dispersers, often in cooperation with other species. One study in the Carson Range of Nevada showed that deer mice nabbed chokecherry, Sierra coffeeberry, and red osier dogwood seeds from black bear scat and buried them. The ones they forgot to retrieve, germinated. Bears also enrich the soil; both species haul migrating salmon out of the rivers and drag them into the woods or eat them on the bank, then ramble away to defecate, spreading marine nutrients and fertilizer into the forest.

Carnivores change the spaces where they live and, in turn, these spaces alter carnivores, particularly those lured by garbage. “Eating more anthropogenic foods changes stress physiology, gut microbiome, how bold the animal is,” Schell says. Black bears with easy access to trash grow bigger and have more cubs. Paradoxically, though, these garbage-filled areas can be “sinks.” They draw bears with the temptation of easy calories, but car crashes and conflict with humans (which can result in removal or killing) keep numbers low.

Humans are part of the ecosystem incoming black bears will have to navigate. And perhaps our most dramatic effect on animal lives comes through the stories we tell. Newspaper accounts and memoirs portrayed California grizzlies as ferocious man-eaters and sheep stealers, but a recent study by UC Santa Barbara professor Peter Alagona analyzed teeth and bones to show that, like black bears, grizzlies ate mostly plants. The arrival of the Spanish and their livestock in 1542 prompted a change in diet, though only from 10 percent meat to up to 26 percent. But the lore of huge, bloodthirsty predators and the glory of besting such a monstrous creature provided fuel for killing them off.

An actual bear roaming the Berkeley campus, sizing up the statuary, seems a long way from likely. The East Bay and South Bay don’t have breeding populations, according to John Krause, senior environmental scien-

tist supervisor with CDFW, though the most recent draft of the state’s Black Bear Conservation Plan shows suitable bear habitat in the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Diablo Range. But even bears several valleys over pose interesting questions about the nature of nature, Schell says. “It would restart this conversation around why we think we’re separate from it when we live in the city.”

One of the most important goals of the North Bay Bear Collaborative, according to Walla-Murphy, is rebuilding a “bear culture,” reframing our stories and expectations: “We don’t remember how to live with these critters anymore.” Rectifying this involves learning from local tribes and other communities that have coexisted with bears for a long time, she says.

Over the past three years, as part of an effort to pass on knowledge about black bears to its youth, the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians has conducted a monitoring program on the Kashia Coastal Reserve and the Stewarts Point Rancheria. Interns complete vegetation transects, install wildlife cameras, and collect seeds for habitat restoration projects. In addition, according to Nina Hapner, director of environmental planning for the Kashia Band, they learn about black bear habits and habitat, needs, and importance in the system. The interns also interview family members or other tribal members about the tribe’s bear history and understanding.

The interns didn’t glimpse a bear until the third year, recalls Hapner, but when they did, it made an impression: “Everybody knew that we have bears up on the Kashia Coastal Reserve…but we just hadn’t seen one. And then we see this guy lumbering along, and it was like: Yes!”

Observations like these mean they are not only learning about bears but from them. “Basically, what a bear eats, we can eat,” Hapner said. “Fish, berries, some plants when they’re young. They teach us things if you watch, if you pay attention.”

She adds, “Just opening your eyes and being open to that instead of being fearful…That’s really important.”

After the bear ransacked Miller’s beehives, Walla-Murphy and Roney stopped by and advised her on how to avoid another

visit. Electric fencing would keep the hives safe, as would, possibly, planting species bears love, like manzanita, on the far side of the creek. If bears show up again, banging pots and pans should scare them away. Roney sent her an air horn. In general, those living in bear country should protect their trash and compost, bring in bird feeders, keep pets inside, pick up windfall from fruit trees. Anything smelly should be secured. The most important thing is to establish a boundary and defend it, says Walla-Murphy: “The bears will respect the boundaries if we have the boundaries, but if we don’t, they’re going to push back.”

Back at Sugarloaf Ridge, we begin to walk toward the old ranch where the first bear was caught on camera. Walla-Murphy strides through the grass, eyes to the ground, pointing out the swirl of a bear track, clipped stalks where a bear could have grazed. She scrambles up a hillside to see whether a bear might have taken this route to the abandoned orchard. Wildfires in 2017 and 2020 burned much of the park and all the old ranch buildings used as staff housing. This left a fence that no longer fences anything in or out. A power line without electricity. A mailbox on a pole that gets no letters. With a few trees left in the orchard—apple, pear, persimmon—it’s a wildlife playground now.

In a clearing where the buildings used to be, bright yellow daffodils mark gardens of previous inhabitants. A huge live oak stands, half burned and flourishing. We continue up the trail, ducking under and scrambling over trees downed in the recent atmospheric river that swept up the coast. Finally, Walla-Murphy comes upon a bear bed, a divot under a scorched conifer. Bears love the bases of big trees like this, the options of advancing down the hill, of retreating up the trunk. She’s never seen a bear in this park, but evidence is all around. And this morning, filled with reedy birdsong and the rushing water of Bear Creek, after an absence of a century, bears are once again possible. ◆

Support for this article was provided by the March Conservation Fund.

22 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG

FEATURE | TOP OMNIVORE

outings@landpaths.org (707) 544-7284 618 4th Street, Santa Rosa #217, 95404 landpaths.org Fostering a love of the land in Sonoma County Sue Johnson Custom Lamps & Shades Since 1972 1745 Solano Avenue Berkeley, CA 94707 510 • 527 • 2623 www.suejohnsonlamps.com Offering online and in-person courses. Interest Groups include hiking, adventure, language conversation, film, books, and more. Visit olli.sfsu.edu Membership Classes Interest Groups A PLACE FOR AGE 50+ LIFELONG LEARNERS OLLI_BayNature_PubSpring2024_draft1_FINAL.indd 1 2/8/24 10:29 AM

In the Name of Eelgrass

To protect the eelgrass meadows in Richardson Bay, the anchor-out era near Sausalito is coming to a close. by anushuya thapa

From a single blade of eelgrass, life overflows. Amphipods build tiny hollow tube-homes on it, while marine snails eat it, and nudibranchs travel its length in search of prey. Small eelgrass sea hares graze epiphytes attached to the blades and lay their yellow eggs inside transparent jelly-like blobs on the thick green of the grass. Amid the meadows, pipefish hide and graceful rock crabs scavenge, and in the fall and spring, giant schools of silvery Pacific herring enter the San Francisco Bay, the end point of their weekslong annual migration. On the eelgrass, they deposit clumpy beads of yellow roe on the order of hundreds of millions, like underwater honey drops. Or the eggs must taste that way to the thousands of birds that join the melee of feasting. Cormorants and loons dive after flashes of fish. Gulls circle above. Rafts of scaups, buffleheads, and more stretch across the water feeding on roe. During a spawn event, which can last for a few hours or several days, herring milt turns Bay waters a lighter hue.

Even when the herring aren’t running, the eelgrass beds teem with food. Paige Fernandez remembers kayaking just off the shore of Sausalito. She was paddling over an eelgrass bed, likely brimming with slugs and tiny crustaceans—which were, from the surface, invisible to her. But she could see the harbor seals. And one in particular kept bobbing its head up over the waves, closer and closer. Now a program manager at Richardson Bay Audubon Center, Fernandez says it was “definitely one of the coolest encounters I’ve had in the Bay.” The surfacing seal’s forwardness surprised her, but in retrospect it made sense: she was above a bed of eelgrass. “That’s where they can find little snacks to munch

24 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG FEATURE | CONSERVATION

on.” They go where the eelgrass goes—and so does a host of other marine life.

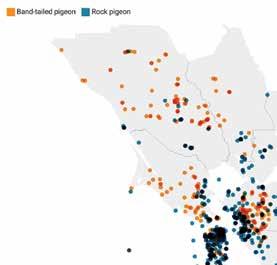

Anchor-out vessels on Richardson Bay float above meadows of eelgrass (Zostera marina) that are home to bay pipefish (Syngnathus leptorhynchus) and graceful rock crabs (Cancer gracilis).

To give shelter and food to the species that rely on it, eelgrass needs to thrive. And in Richardson Bay, which lies between Sausalito and Tiburon in Marin County, dozens of acres of eelgrass are tangled in with the anchor chains of dozens of boats that often float just five feet above the meadows. When tides shift, the ground tackle—that is, any equipment used to anchor the boat, usually a long and heavy chain—is yanked by the pull of the vessel. In circular, sweeping motions, the chain slices the eelgrass rhizomes, the lateral tubes from which the shoots and roots grow. The chains and ground tackle erode the sediment, creating a depression in the substrate. After years of scraping, a dead zone forms, cleared of eelgrass, where shoots don’t take root. From above, boats hover over what look like ghostly crop circles, some half an acre in size, called mooring scars. There are almost 80 acres of scarring in Richardson Bay.

In the spring and early summer of 2024, researchers from San Francisco State University’s Estuary and Ocean Science Center, restoration workers with environmental consulting firm Merkel & Associates, and Audubon volunteers and staff—including Fernandez—began replanting eelgrass in the Richardson Bay mooring scars thanks to a $2.8 million grant from the Environmental Protection Agency; the grant is part of an EPA program funded by the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Over the course of four

years, the project aims to restore 15 acres of eelgrass, each acre allowing more life to bloom. But for workers to restore eelgrass in these scars, the anchors causing them must also be removed. “It is well demonstrated that eelgrass and anchoring are incompatible throughout the world,” says Rebecca Schwartz Lesberg, president of Coastal Policy Solutions, who was awarded the EPA grant. “Richardson Bay was really behind the times in terms of how to manage this natural resource conflict.”

In Richardson Bay, these long, heavy anchor chains are often attached to boats with people living on them— the so-called “anchor-outs,” people who have spent decades building their lives on the water, on their boats, and on the premise of free anchorage. Born of the ‘60s counterculture, the community began with artists

Bay Nature’s reporting project exploring the impacts of big federal money on our area.

Bay Nature’s reporting project exploring the impacts of big federal money on our area.

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 25 From top: Jacob Saffarian; Shane Gross (3x)

and young people who were drawn to the scrap left by World War II’s Marinship shipyard, material they salvaged for boats and homes. It quickly grew into an on-the-shoreline, and on the margins, way of life that has included famous artists, like Shel Silverstein and Allen Ginsberg, but mostly those who are unknown, like Lisa McCracken, once a silk-mache artist, and her friend Peter, who she says snaps daily portraits of the Bay fog and cloudscape.

The lifestyle has been called many names: anchoring out, being a live-aboard, or, in McCracken’s younger days, living “on hook.” It comes with a degree of precarity, where a single storm or a faulty anchor might sink a vessel. Many anchor-outs drown, or their boats come loose and crash into shore or other boats. McCracken says about her life on the Bay for 30-plus years, surrounded by water, marine creatures, and in community with artists, “It’s a privilege and a blessing.” And for many who took to the Bay’s waters, then and now, the alternative to life on their boats is homelessness.

But after six decades, the anchor-out era is coming to an end, in part to protect eelgrass habitat from mooring scars. The number of anchor-out vessels in Richardson Bay has dropped from over 200 in 2018 to about 32 today. The authorities that regulate Richardson Bay and the entirety of the San Francisco Bay began in 2019 to focus on upholding ordinances that have long been on the books but were rarely enforced. As a result, anchor-outs have been evicted and left homeless and unoccupied boats crushed. The last of them have been ordered to leave the zone where eelgrass grows by this October and the water entirely by 2026. Authorities are offering housing to some as an incentive to meet the deadline.

Richardson Bay eelgrass beds naturally change over time. Notice the circles of anchor damage.

Restoring eelgrass

To McCracken, and other anchor-outs, eelgrass restoration is the latest excuse employed by authorities in their long-standing campaign to rid the water of her community. And her opinion is partly well-founded. There are examples and studies of eelgrass thriving when the mooring scar-causing chains are replaced with “conservation moorings.” These moorings, used around the world, are affixed to the seafloor, eliminating the dragging chain that creates mooring scars. Despite a 2019 feasibility study recommending eelgrass-friendly moorings in Richardson Bay, environmental groups, regulatory agencies, and cities pursued a more stringent option: remove all anchored-out vehicles from Richardson Bay eelgrass beds, in perpetuity.

But during public meetings in the years following the feasibility study, local residents voiced concerns—they felt environmental restoration was clashing with the needs of the region’s most vulnerable. “This will have huge effects,” reads a public comment by “Elias” in 2020. “What about the young children who will learn of this and not feel comfortable working with nature organizations because of their relationship with poor people?” He equated it with “forced migration perpetuated by environmentalism.” David Schonbrunn, a Sausalito resident, commented in a 2021 meeting that opting to remove anchoring instead of choosing mooring systems that would let the anchor-out community and eelgrass coexist was “a question of policy, not science.”

It’s a bright windy day in March, and Jordan Volker is steering a motorboat into Richardson Bay. He’s a field operations manager for Merkel & Associates, which has published articles and field reports on eelgrass for 30 years and run eelgrass surveys in the area for decades. The company’s 2014 survey found a massive die-off in Bay eelgrass caused by a marine heat wave. To repair the loss, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) funded a 75-acre eelgrass restoration project that’s ongoing and aligns with the Bay Area’s Subtidal Habitat Goals. The 2010 goals, in an ambitious 208page document, lay out a vision to study, protect, and restore an

FEATURE | CONSERVATION Eelgrass Occurrence Frequency (2003-2019) 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

26 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG

From left: An anchor-out boat; aerial image of eelgrass in Richardson Bay showing anchor damage in 2017; researcher Jordon Volker monitors eelgrass in the Bay.

array of subtidal habitats, including eelgrass and oyster reefs. The regional effort brought together the California State Coastal Conservancy, the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), San Francisco Estuary Partnership, the California Ocean Protection Council, and NOAA, giving them a common framework to achieve a healthier Bay.

Collectively, the agencies set a goal of restoring up to 8,000 acres of eelgrass by 2060—latest counts say there’s a maximum of 5,000 acres in the Bay. Any added acres would mean more habitat for herring and birds, at a time when waterbird data has grown grim. Scoters, for one, saw a 50 percent decline around the second half of the 20th century, according to a Sea Duck Joint Venture report. And that’s for their populations across the whole Pacific Flyway—local numbers are worse. Both greater and lesser scaup have declined by a similar amount, and horned grebes and buffleheads, two beloved Bay Area visitors, have also suffered. “It’s all part of one big food web,” says Casey Skinner, program director at Richardson Bay Audubon. “And if we lose eelgrass, we lose everything.”

Eelgrass’s benefits go beyond ecology. The beds act as sentinels of the Bay, trapping sediment, storing greenhouse gases, and protecting against wave action. Threats to eelgrass, too, are multifold. In 2005, for example, sediment that broke loose smothered nearby eelgrass beds, causing a die-off in subsequent years. Built-out marinas, ports, and wharves are potential stressors, too. They can shade out the eelgrass underneath, preventing meadows from growing. And, in addition to mooring scars, anchor-out vessels can damage the water quality if occupants mismanage waste—although 2018 reports show water quality has been improving overall in Richardson Bay. “Submerged habitats truly need ongoing championing because it is so easy to ignore. They’re out of sight out of mind,” says Marilyn Latta, a project manager at the California State Coastal Conservancy, who helped develop the goals for eelgrass restoration.

Keith Merkel, the principal consultant of Merkel & Associates, has been (often literally) knee-deep in eelgrass since restoration efforts began in the Bay Area, conducting Bay-wide surveys of eelgrass on three separate occasions. And the one thing he’s learned?

Richardson Bay is vital for eelgrass. It contains the second-largest eelgrass bed in San Francisco Bay and is the single most important spawning area for Pacific herring in the estuary. “Richardson Bay is protected against many of the things that fluctuate quite a bit,” Merkel says.

In the South Bay and Oakland, that factor is turbidity—too-dark waters, without enough sunlight. In the North Bay, too much fresh water discharges from the Delta. And around the Pacific Coast, the wind blows east, so eelgrass seeds fail to disperse. Yet Richardson Bay has “so much eelgrass that we never lose 100 percent of the eelgrass in [it],” he adds. The “core eelgrass bed”—areas that lie at the ideal depths for the plant to thrive and should support close to 100 percent eelgrass cover—include the mooring scars. If restored, Merkel says, this area will consistently flourish. It’s the kind of priority restoration area that the Subtidal Habitat Goals have highlighted. It took research to prove restoration in the anchor scars was even possible. NOAA funded the first small-scale project to test the potential in 2021. Even this 2.5-acre effort, Merkel says, got off the ground only after many anchored-out vessels had been removed. NOAA won’t fund more restoration, he says, unless authorities can demonstrate there’s little risk of anchors being dropped again.

Back inside the motorboat’s cabin, where Jordan Volker works, things are dark, and he has both hands on the wheel to navigate the churning, unruly water. On the monitors above, he shoots glances at two screens that give readings from the Bay underneath. The boat pumps a sonic signal into the waves below—and returns a spiky, pulsing graph. Because eelgrass blades store oxygen in their cells, they are less dense than the surrounding water, so they return a telltale “bump” to Volker’s machine, locating the meadows.

Volker has been restoring eelgrass in Richardson Bay for Merkel for so long that he can recognize some of the beds he’s planted just from the dots on the graph. “It always brings a big smile on my face when I drive over and go, ‘Ho! Look at all that grass.’” Now he is dropping markers on a digital map, locating anchored-out boats and mooring scars, data that will inform where to plant next.

Once they choose a spot, Volker and others plant during low

SUMMER 2024 | BAY NATURE 27

Left page: Merkel & Associates; Shane Gross; Jacob Saffarian. Right page: Image courtesy of Audubon California, collected by Patrick and Julie Belanger, The 11th Group, Inc.; Jacob Saffarian

tides—restoration crews up to their hips in Bay water, the boats of the anchor-outs looming behind. Volker says folks on the water and those from the land used to meet at some kind of a shore-y middle ground. An anchor-out near a cluster of volunteers might say hello from their deck and play music. “While we’re planting a mooring scar, people that are nearby say, ‘What radio station do you want to listen to?’ and [start] cranking their radio up,” he says. Often, they’d be smiling, waving, and curious about the restoration effort going on in their backyard waters. “Some of the anchor-outs understand, ‘oh yeah, eelgrass is an important thing. I don’t want to harm eelgrass. I just want to live,’” Volker says.

Lisa McCracken has called Richardson Bay home for three decades. She lives aboard Evolution and spends her time helping other anchor-outs.

But things are different now that people know their lifestyle is under threat. There are fewer friendly faces when he cruises the water. “Some of the anchorouts, I think, see a survey vessel, or see a bunch of college kids coming in with grass in their hands, as a threat.” As if on cue, our tiny survey vehicle weaves in close to an anchored-out boat, with a gray-haired man on his deck. Outside, Scott Borsum, Volker’s assistant for the day, greets the stranger. He returns our “hi” with a “hello,” but, when asked for a picture, tosses his hands to the air, turns away, and shakes his head no.

Borsum’s new to restoration work—this project is his first field job since getting his PhD. Already, though, he feels like he’s watching a “microcosm” of the housing crisis in the San Francisco Bay Area unfold, wherein people are pushed out into alternate lifestyles by the cost of living or decades’ worth of other factors, then become the object of long and drawn-out political debate over who can use public spaces and for what. “It becomes a user-rights issue,” he says. “Who gets the right to the Bay?”

Volker says he’s glad he’s not the one deciding. Unlike the “policy side of things,” he says, the eelgrass restoration is a peaceful, straightforward task. And the housing and what comes after is for other, more policy-savvy folks to decide. “It’s the side of the issue that I would not want to deal with,” Volker says. Borsum agrees: “Our job doesn’t constitute us solving that problem. It just constitutes us understanding the grass.”

Similar sentiments are echoed by project managers at Audubon, another of the EPA grant beneficiaries, who say their “area of expertise” is the eelgrass, though noting that they favor fair housing. The researchers at SFSU involved in the long-term monitoring of the grass also declined to comment on the anchor-outs. On the water, the restoration crew’s survey boat and the anchor-outs are two ships that, both metaphorically and practically, pass each other by—leaving an uneasy silence rippling in their wake.

Living on the water

It’s an unusually calm day—no wind, great sun—when we set out in a kayak. We paddle across a boating channel, the thick on-the-water “highway” used by cargo vessels and traveling houseboats alike, to the waters where the last anchor-outs hold on.

We weave in between vessels, passing signs of life everywhere: on one boat, scuba gear hangs out to dry on a clothesline on deck; on another, smoke escapes a moka pot visible through a cabin window. Names like Irish Misty and Levity are hand-painted on the sides of boats big and small. Some are 15-foot sailboats with little to nothing in the way of rain shelter for their occupants. Others, like the mighty Evolution, a 50-foot powerboat, tower above our kayak. But the captain on its deck is Lisa McCracken, who is anything but forbidding. Her sand-brown hair is turning white against the sun, and she wears mismatched work gloves and a friendly, if squinting, smile. She greets us, but is too busy to chat long—there are always chores to be done on the anchorage, whether it’s changing oil in a generator or fixing a solar panel. When we come back another day, it’s 4 p.m. and McCracken’s still working—her friends are visiting, their presence evident by the skiffs tied to the back of her own. They’re trying to get a motor up and running, when she welcomes us aboard. A flimsy white ladder is the only way up. And landing zones are scarce in between the piles of decommissioned engines, old anchors, empty diesel cans, dusty life vests, tubes and piping, et cetera. McCracken, though, steps on and over them with ease—at times nimbly jumping up and sitting on railings to let us pass. “I tend to this place,” she says. Many of the objects aren’t hers—they’re things she’s rescued from the Bay. She points to an anchor, coiled up in its own chain, that sits in a corner. “That tends to disturb the bottom—these are anchors. These we have pulled up.”

McCracken, now 61, says she’d want to learn more about the eelgrass, if she could, and had a mind to send in samples to someone. “If you notice it, it’s getting gray,” she explains. “I want to understand the characteristics of it, the features.” She says she sees, studies, and notices things—like the pigeons and gulls that have made a nest on the boat’s roof. Or, occasionally, a dying bird adrift, which she’ll try to call in to local authorities. She doesn’t believe her boat does harm to eelgrass (and, given that it’s on a six-point mooring and not a blockand-chain anchor, it likely does less damage than others), or that the

Jacob Saffarian Shane Gross 28 BAY NATURE | BAYNATURE.ORG FEATURE | EELGRASS

harm she does is any greater than the waste generated by the city or the propellants of high-speed yachts and other boats that dock in Sausalito Yacht Harbor or any of the dozens of other harbors nearby. “To say that we are a problem, then every boat here is a problem.”

As we talk, the boat turns gently with the wind, a planet spinning, the sun hitting the inside from each angle in turn. Maybe, McCracken admits, she’s selfish for not wanting to give it up—a panoramic view of the Bay, who would? But more than the view, it’s the community she can’t bear to part with. It was fellow anchorouts who taught her how to live on the water. She recalls, laughing, when her first boat lost footing and slammed into a barge, and how the owner taught her the ropes of being a mariner. By now, she’s more than returned the favor: jumping in to help friends pull someone who was having health problems out of a boat. Or standing by the hospital bed of Craig, a longtime friend who, in gratitude and in passing, gifted her and her friend Steve Evolution.

These days, she wakes up and takes off in her skiff—looking for others on the anchorage who might need a hand, or a battery, or something she can offer. “I’ve held fast to anchor. I can’t even imagine being condemned to a room,” she says. “I don’t know what I would make of my day.” Besides, she doesn’t qualify for the housing and cash deal offered by local authorities, since she doesn’t own Evolution. Steve owns it, and according to reporting by the Pacific Sun, the program provides one housing voucher per boat.

“I don’t want the money,” she says, of the cash offer: $150 per foot of the boat. “I want to be left alone—you can build your paradise around me, okay?” Her voice rises as she speaks. “I’ll figure out some way to put a mirror up, so you don’t have to look at me if you don’t want to.”

In five months, however, she’ll have to leave the anchorage. Evolution doesn’t qualify for the Safe and Seaworthy program that would have allowed the boat to stay two years longer. McCracken says a caseworker is advocating for both her and Steve to be housed, but she isn’t sure where she’ll be five months from now, or if she’ll even want to go.

The policy fight

In the years leading up to 1985, no single agency existed to guide the use and conservation of Richardson Bay’s waters, so cities on its shores created and adopted a “special area plan” that stated, among many things, that “all anchor-outs should be removed from Richardson Bay.” Even then, nearby authorities felt the number of boats anchored offshore was growing.

To execute the plan, the Richardson Bay Regional Agency (RBRA) was formed, via a Joint Powers Agreement among Marin County and the cities of Mill Valley, Tiburon, Belvedere—and, formerly, Sausalito. The agency quickly passed an ordinance allowing transient vessels, such as cruisers from outside the Bay, to drop their anchors in designated areas for less than 72 hours. One section hugged the Sausalito shoreline; the other spanned the anchor-out area. It also states that permanently “living aboard” any vessel in the water is illegal—permits could be granted for 30 days, and potentially longer, if the harbor-

master “determined that no permanent residential use is intended.”