LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER

California’s New

State Park first in 15 years

LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER

State Park first in 15 years

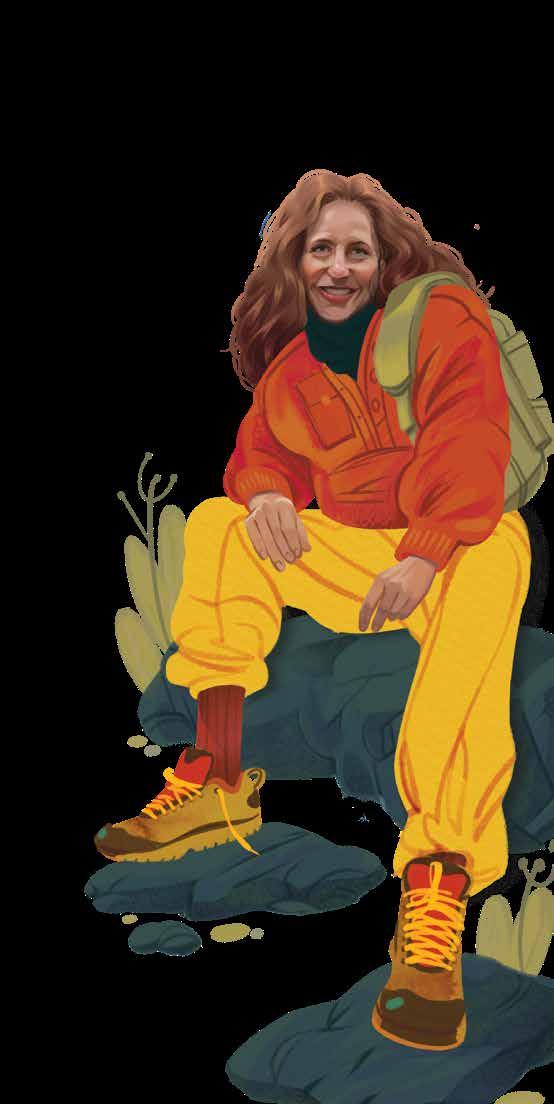

PROFILES 20

Local Heroes

Join our celebration of four inspiring Bay Area people who are caring for the natural world through stewardship, research, and land management. Meet Bay Nature’s 2024

Local Heroes: Naji Lockett, Yakuta Poonawalla, Katharyn Boyer, and Kellyx Nelson.

ByWILDLIFE Bat Healers

When flowers bloom and insects emerge in the spring, so do Northern California’s 17 bat species, making it a good time of year for people to watch them. It’s also when a surge in calls for help keeps NorCal Bats volunteers busy rescuing and tending bats back to health.

By Stephanie PennBay Nature staff 20

PUBLIC LAND 28

The first new state park in 15 years is opening. Situated at the confluence of the Tuolumne and San Joaquin rivers, your modern state park has to be an overachiever: Dos Rios Ranch’s 2,100 acres will serve wildlife, depleted aquifers, underserved communities, and Indigenous people. “A park of the future,” state parks director Armando Quintero calls it.

By H.R. SmithCLIMATE 34

East Bay Adaptation (sponsored)

As a major landowner, the East Bay Regional Park District finds itself on the front lines of climate change. Learn about the district’s efforts to prevent wildfire in the hills and prepare for sea level rise along the shoreline.

By Janet Byron

38

How do you increase inclusiveness in the outdoors? 510 Hikers is a community-grown example that has been building for a decade. Their secret: hold a Bay Area hike nearly every Saturday and welcome everyone.

By Lia Keener

42

By Guananí Gómez-Van Cortright

p. 28

H.R. Smith is a freelance science journalist and editor, and a former Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT. She is exceedingly interested in most things, and is currently at work on a book about habitat restoration and an anthology of queer science writing.

p. 28 & cover G Yang is a background painter and visual development artist currently pursuing a BFA in illustration at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California. Born and raised in Toronto, Ontario, her work explores emotions through color and light, seeking out the whimsical in everyday life. Yang has exhibited in group shows featuring her plein air paintings at Gallery Nucleus and the Animation Guild.

p. 34 Janet Byron is an independent writer and editor whose work most recently appeared in Estuary News, Maven’s Notebook: California Water News Central, KneeDeep Times, Berkeleyside, and Bay Area Monitor. For 13 years, she was managing editor of the University of California’s California Agriculture journal. She is co-author, with Robert E. Johnson, of the self-guided walking tours book Berkeley Walks (Heyday).

Other contributors to this issue: Jane Kim (p. 12), David Nelson (p. 14), Endria Richardson (p. 15), Sadie Rose du Vigneaud (p. 15), Matthew Harrison Tedford (p. 16), Guananí Gómez-Van Cortright (p. 42), and John Muir Laws (p. 46).

p. 38 Lia Keener joined Bay Nature in June of 2022 and is shaping the organization’s first Outreach Fellow position to expand and better understand Bay Nature’s readership. She graduated from UC Berkeley with a major in environmental biology and minors in Chinese language and journalism, writing for The Leaflet and The Daily Californian. In her free time, she loves painting and searching for critters of all kinds in the Bay Area and in Central Oregon.

p. 18 Russ Aguilar is an educator, artist, and naturalist from Marin County. He has worked as a guide and educator for the National Park Service in five states and the District of Columbia. Presently, he teaches a STEAM class at Aptos Middle School in San Francisco, organizes shows of his artwork, and leads nature walks. His work focuses on sharing the wonders of nature with people of all backgrounds, and his artwork focuses on invertebrate life.

p. 20 Violeta Encarnación is an award-winning Cuban illustrator based in New York City. She enjoys creating works for periodicals like Bay Nature, Apple News, Vox, and The Washington Post, as well as for books, one of which is being published later this year. She blends traditional and digital techniques to tell stories through exciting and colorful images. She has recently found a passion for winter camping, along with growing her own vegetables on her windowsill.

masthead, vol 24, no 2

spring 2024

Ex E cutiv E Dir E ctor/ p ublish E r

Wes Radez

E D itor in c hi E f

Victoria Schlesinger

D igital ED itor

Kate Golden

a rt Dir E ctor

Susan Scandrett

managing E D itor

Alia Salim

outr E ach f E llow

Lia Keener

journalism f E llow

Anushuya Thapa

copy ED itor

Cynthia Rubin

aD v E rtising Dir E ctor

Micaelyn Compton

proofr E a DE r

Dominik Sklarzyk

DE v E lopm E nt manag E r

Barbara Butkus

D E v E lopm E nt a ssociat E Christina Jaramillo

m ark E ting & o utr E ach Dir E ctor

Beth Slatkin

o ffic E m anag E r

Jenny Stampp

i nformation t E chnology m anag E r

Laurence Tietz

cofoun DE rs

David Loeb, Malcolm Margolin

b oar D of Dir E ctors

Deonna Anderson, Catherine Engberg, Nan Ho, Rebecca Johnson (president), Suzanne Moss, Anh Phuong Tran

v olunt EE rs/ i nt E rns

Jacqueline Gauthier, David Wichner

Bay Nature is published quarterly by the Bay Nature Institute

1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710

membership:

$40/year

(888)422-9628, BayNature.org

PO Box 6409, Albany CA 94706

Advertising: advertising@baynature.org

Editorial & Business Office: 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710 (510)528-8550; (510)528-8117 (fax)

baynature@BayNature.org

Printed by Commerce Printing (Sacramento, CA) using soy-based inks and alternative energy.

ISSN 1531-5193

No part of this magazine may be reproduced without written permission from Bay Nature and its contributors.

© 2024 Bay Nature

New stories are born, daisy-fresh, each week on BayNature.org. Get great reads, events, trails, and more in our weekly newsletter: TinyURL.com/BayNatureNews

» Precious Muck

Hallelujah: With a shot of funding, some long-deprived Bay wetlands are getting dredged sediment—much of which had previously just been dumped off an underwater cliff. Sonya Bennett-Brandt gets on a boat to follow this magical mud to its new North Bay home and asks: will it be enough to save the shoreline?

» Ag Climate Program Is Short on Applicants

Congress boosted funding for on-farm conservation measures, like making pollinator habitat or wildlife corridors— but the Natural Resources Conservation Service is struggling to spend this windfall, Anushuya Thapa reports.

» Eulogy for a Lost Crayfish

It was about a century ago that a sooty crayfish last ambled across the bottom of a Bay Area stream. At last, she and her kin get their due. “For each crayfish is a world unto itself, a host of tiny passengers,” Anton Sorokin writes.

C tions

In the Winter 2024 issue, two photos by Julie Kitzenberger accompanying an opinion piece on beavers were taken along Los Gatos Creek in Campbell, not San Tomas Aquino Creek. Also, the story says researchers have cited at least 20 Indigenous groups in California with words for beaver; the correct number is at least 27.

» One Heck of a Fungus Debbie Viess introduces us to our new state mushroom, the California golden chanterelle, which can grow and grow to a mon strous size.

» Make Way for Eelgrass

Richmond’s dilapidated, patently unsafe, toxic-creosoteinfused old pier at Ferry Point is finally going bye-bye this summer, Anushuya Thapa writes.

It w I ll be a year th I s March since I stood onstage at the Local Hero Awards and promised that the Bay Nature community would help shape the organization’s future. We asked to hear your thoughts and ideas through surveys, focus groups, and conversations, then listened to your responses.

Collectively, you told us that Bay Nature is more than a magazine. It nourishes those who identify with nature in the San Francisco Bay Area. From these pages, a community grows.

With this understanding, Bay Nature will begin to offer more opportunities to experience our stories together after reading them, deepening our connections with local nature and each other. We’ll take more hikes to explore habitats and ecosystems. Conduct more forums to speak with experts in the field. And visit more project sites where cutting-edge work occurs.

Current magazine subscribers, such as yourself, will be referred to, going forward, as founding members of the Bay Nature community. Rest assured that the Bay Nature magazine you know and love isn’t changing. Rather, you can expect to see more of our stories brought to life.

Bay Nature’s 14th Local Hero Awards event is April 7 in Berkeley, and I invite you to read the profiles of our inspiring honorees in this issue. Dr. Katharyn Boyer, Yakuta Poonawalla, Kellyx Nelson, and Naji Lockett are doing the important work of caring for people and our natural world.

Even as we recognize our community leaders, the Local Hero Awards also celebrate all of you and the efforts by individuals, organizations, and agencies around the area to make local nature and environmental issues tangible parts of daily life. Gathering each year at the Local Hero Awards reminds us that there is nature everywhere. It is common ground that binds us.

Let’s keep exploring nature together in print, online, and outdoors. I hope you will join us in growing and enriching an essential San Francisco Bay Area nature community whose ideas and stewardship are shaping a more equitable and sustainable future for us all.

Please visit BayNature.org/membership or write to me at wes@baynature.org with any questions about Bay Nature’s new membership program.

lyngsogarden.com / 650.364.1730

345 Shoreway Road, San Carlos

A sense of wonder and inspiration awaits you at the UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley! Explore a diverse landscape spanning 34 acres, with something new to see or learn with every visit. Browse the Garden Shop, take a class or docent tour, or host your next event at the Garden!

botanicalgarden.berkeley.edu

... is full of rebounds and reflection.

Year's

Spotlight: Zodiacal light

Find a location free of artificial light, like the Point Reyes National Seashore, with a clear view of the western horizon at dusk. It should also be free of fog, moonlight, and clouds, as the sun finally settles into the Pacific. Once it’s gone, look for a tall “pyramid” of diffuse light reaching up from the horizon. This is zodiacal light. The long-observed phenomenon can be seen in the Bay Area during the spring months, close to the equinox. We know photons reflecting off dust particles orbiting the sun cause zodiacal light, but only recently was the dusty planet Mars pinpointed as the particles’ likely source, according to data collected by NASA’s Juno space probe in 2020.

h ammerhead

c hipmunk rebound

Looking at an iNaturalist map, it appears the Golden Gate strait, San Francisco Bay, and Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta delineate the great divide between the Bay Area’s two chief chipmunk species. To the south scurry Merriam’s chipmunks (Neotamias merriami), and to the north bark Sonoma chipmunks (Neotamias sonomae). The latter elusive cutie was spied last year in Sugarloaf Ridge State Park, perhaps for the first time. In spring, a litter of chipmunk pups is born, weaned, and on its way in a matter of weeks.

The one species of kingfisher that flies Bay Area skies has an industrious spring. Male and female belted kingfishers ( Megaceryle alcyon) not only woo and choose each other, they also dig a tunnel up to 15 feet deep into a stream bank together. If it’s a tricky vertical location, they may take turns ramming it with their blocky heads, beak first. Next, they shovel dirt from the passageway and new cozy nesting cavity using their fused toes. Their famous rattling call, when made as they approach the nest, may be a kind of “incoming!” alert to family members to clear the passage for their landing.

Whim S y all the W ay do W n

Fanning out like great tentacles, the limbs of California’s native Western sycamore (Platanus racemosa) are a savior when the sun is beating down. In early spring, clusters of fuzzy pom-poms bearing teeny-tiny flowers, maroon if female, dangle from the tips of those billowy branches. The wind, carrying away the tufty seeds, soon transforms the pom-poms into ho-hum brown, nubbly globes. Surprising to think they contain multitudes of acres of future shade.

h are of the S ea

Ever wonder how a garden snail looks without its shell? The California brown sea hare ( Aplysia californica) is a pretty good approximation. But a lot bigger (often larger than a human hand), found in tidepools, and known for the clouds of reddish-purple ink it releases in self-defense, irritating nearby anemones. In spring and summer, these hermaphrodites mate and, just before heading to sea hare heaven, lay piles of sticky, jelly-covered “noodles” containing 80 million eggs.

Wingmen

If it’s a silvery blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus) boom year, you’ll likely know it. The dime-size male butterflies gather around spring mud puddles, sometimes by the hundreds, according to lepidopterist and UC Davis professor Art Shapiro. Slurping up sodium and calcium is one reason, particularly when nectar from flowers in the pea family, their favorite, is hard to come by. It’s also possible that these “mud puddle clubs” somehow increase their chances with the ladies.

Have you ever gone outside on an early spring morning and spied “dew” on the grass? And then on closer inspection, you wondered why the droplets only appear on the tips of the blades? Or perhaps you noticed that some plants had water droplets along the margin of the leaves? That’s not dew, it is guttation.

Guttation is actually a mixture of xylem and phloem fluid, which contains sugars and other chemicals produced in the leaves that are exuded by the plant overnight. Unlike dew, which is pure water, guttation is rich in the organic and inorganic dissolved substances that are the lifeblood of the plant. Whereas guttation comes from the plant, dew comes from the atmosphere. You are lucky you got up early that day and were rewarded with this unusual sight, because it soon will evaporate.

What causes guttation? In biology 101, we were taught that when water evaporates from a plant’s leaves it causes fluid to move through the plant, a process called transpiration, but the story is much more complex .

First, a wee refresher: A plant leaf has microscopic holes in its surface, called stomata, that allow in carbon dioxide. A plant combines that CO2 with water by means of photosynthesis, using chlorophyll (perhaps the most important single chemical in the universe). The end product of photosynthesis, oxygen, then escapes through the stoma (lucky us).

A side effect to open stomata is water loss—so much so that 97 to 99 percent of the water brought up through the xylem is lost via transpiration. Each molecule of water lost in the leaf through the stomata is replaced by another adjacent water molecule, which, by capillary action and surface tension, tugs on another molecule, and this goes on down the line through the xylem to the roots. We generally think that water enters the roots passively only because of the pull of this transpiration process, but there is another, less well-known, process also going on: guttation.

The sap within the roots contains dissolved sugars and potassium and other organic and inorganic compounds. The soil in contact with the roots is less rich in such solutes, so water tends to passively enter the roots through osmosis to equalize the concentrations of the compounds in and outside the root. The pressure moving the water

into the root is called the root pressure. The root pressure is so much weaker than the transpiration pressure that the latter overshadows the former during the daytime.

However, at night, photosynthesis shuts down and the stomata are closed, conserving water. If the soil is moist, the root pressure will increase the pressure in the xylem, forcing the leaf to offload some of the fluid. You could think of it as an emergency escape route. When the plant needs to release fluid, and the stoma are closed, the fluid finds another way out. It exits

through specialized pores called hydathodes; they are located at the tip of the blade of grass or at the margin of a leaf, typically at the tip of a marginal tooth or serration. If the humidity is high, the guttation does not rapidly evaporate, but accumulates at the leaf tip.

So go exploring in the early morning and see what you can find. Then you can tell your friends that you were engaged in guttation with the plants! That should roll some eyes at the local coffee shop. ◆

David NelsonThe tiny droplets shown in the photos above and below are not dew. They are guttation, a plant’s internal fluids that are exuded at night under certain conditions.

Running is how i know cemeteries best, which is not as surprising as it seems given the rural cemetery’s history as precursor to the public park in the United States. Anyone who has visited a rural or “garden” cemetery may feel its ambivalent kinship to both public-ness and park-ness. A casual stroll through bare, bleak city streets reveals a compellingly wrought gate, opening to a gently curving path. Abundant trees, shrubs, flowering plants, a green hillside! A view unlike any other in the flat, gray city.

It is easy to miss the gravestones for all the soft green and yellow nature. Certainly before knowing the history of rural cemeteries, I knew their beguiling accessibility. They have felt as much a part of the infrastructure of cities I have lived in as the roads and sidewalks and skylines. In dreary Cambridge, Massachusetts, I ran around the earliest rural cemetery in the country, Mount Auburn, built in 1831. In Brooklyn, I would as often run to Green-Wood Cemetery as to Prospect Park. Now, in Oakland, I run to Mountain View Cemetery.

Prior to the pandemic, I explored its grounds regularly. Before my wife and I got engaged, we meandered up the winding pebble-strewn paths, past the Monterey cypress, the cedar, past the secret outcrop of radiolarian chert, until we found a likely place to sit. The modest skyline of San Francisco and the rounded Headlands and the silver slip of Bay were before us, and we planned our future life together. So drummed into my sense of Oakland was Mountain View that its quintessential privateness did not even register with me until it abruptly closed to the public at the beginning of 2020 due to the pandemic—then was open only to the loved ones of those interred in the cemetery until 2022. A message posted to the Facebook page cited a range of public ills: unruly dogs, trespassing, graffiti, littering, and others.

for these cemeteries. Designed according to Napoleon’s imperial decrees, Père-Lachaise initiated a new-to-the-time practice of selling permanent, private burial plots to individuals and families. Mountain View Cemetery was established in 1863 and designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, known, of course, for his public parks. The goal, for Olmsted and other designers, was to honor the dead and for the stewards of the cemetery to protect against the “carelessness, forgetfulness, and individual bad taste” of public opinion.

At Mountain View, Olmsted stressed that replicating the East Coast cemeteries in the “unfortunate” landscape and climate of the Bay Area was infeasible. Trees indigenous to areas with similar climates were preferable. The cypress of lower California were favored for their ability to grow in climates similar to the Bay Area’s, as well as for “seem[ing] more than any other tree to point toward heaven.”

I so love the sprawl, the winding roads, the grasping trees, the uncanny peace of these garden cemeteries. But I also visit with the uneasy sense that I—not having a loved one resting in their hills—am the noise, the crowd, the public city. And, too, I cannot help but think about the longer history of space and sacredness, so often conflated in the cramped or crowded city. Public space is more and more encroached upon, delimiting spaces of sanctuary: Oakland First Fridays are temporarily paused, People’s Park in Berkeley is walled off, parks are cleared of people’s homes, public housing continues to fall.

The rural cemetery has always been equal parts pragmatic and romantic, and a privatized version of the public cemetery was at the core of its rise. A response to increasingly overcrowded, unsanitary, and largely communal city church graveyards, rural cemeteries arose in the 19th century. They are burial grounds built on the accessible outskirts of cities—meant to be serene and picturesque, but not so isolated or remote as to be unreachable for people living within the city. Unlike the later state and regional parks, rural cemeteries are often privately held, entrusted to a nonprofit or board of trustees to determine the extent to which the lands— which can be sprawling and costly to maintain—would be made open to the public.

The Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris was an early template

Cemeteries are heady spaces, ripe with meaning for how we think, mostly, about life. The rural cemetery movement reveals the weight the cemetery holds in our imagination. Read through the planning documents or opening remarks for these places, and you’ll find similar yearnings, achingly familiar to anyone who has lived in a big city. If we must live so closely alongside the precarities of modern life, we need the comfort of nature, that is, beauty, softness, space, the remembrance of joy. This is not a private yearning. It is a public one, in the sense that it is shared, equally, by all.

Mountain View partially reopened to the public in 2022. Now, three days a week, anyone may visit. I wish it were open every day. The limits reflect that other reality of Oakland: its shrinking public space, its less welcoming demeanor. Still, I am grateful to visit almost every week. Amid death, I am comforted too by the trespassers, the graffiti, the unleashed dogs. I am comforted by the city, its people who come to the cemetery to be transported, to remember that we are, together, its breathing life. ◆

Along linen dress with exaggerated arms inspired by late-19th-century wedding gowns is adorned with more than three dozen embroidery hoops. Stitched on each circle of beige cloth is a California plant in flower. Sewn with light blue petals and brilliant yellow stamen, there’s the normally white and delicate Marin dwarf flax (Hesperolinon congestum), endemic to the state and found almost exclusively in the Bay Area. The unusual dark blue Baker’s larkspur (Delphinium bakeri ), also endemic and nearly extinct in the wild, is outlined with blue and a few purple threads. The colorful stitchings portray a lively panoply of vegetal life.

The dress is the culmination of an eight-year-long project, titled “the lost ones,” by Bay Area textile artist Liz Harvey. She held public performances and what she calls “social stitching circles,” inviting the public to work on the dress and begin a relationship with an embattled species. The project, she says, “draws on the past to navigate toward an uncertain but yet hopeful future,” highlighting “overlooked species, untold histories, and little-acknowledged art practices.” Describing feelings of “unspoken anguish” about climate change and species loss, Harvey wants to open “a portal to people having a connection.”

The dress functioned as both the focal point and the outcome of 26 performances, held almost entirely in the Bay Area and staged over many years. At these events, while performers donned the dress—sitting, singing, and even dancing—passersby were invited to stop and stitch one of the plants selected by Harvey, often picking up where some unknown embroiderer left off. Harvey says that the unsuspecting participants “weren’t quite sure what they were in for.” And since no prior embroidering experience was necessary, Harvey couldn’t know what to expect either. Though she created initial line drawings on the linen to guide participants, she says that “people were free to elaborate and wander.”

“If a scientist were here,” Harvey acknowledges, “they might say, ‘I don’t think this is right.’” But botanical accuracy was not the point. Harvey recalls a tween, during the project’s first performance, who was “very attached” to their work and concerned about having enough time to complete it. It is as if they entered through the kind of portal Harvey hoped to create, one that builds feelings of connection.

Harvey describes each of these performances as a “devotional ritual,” with the participants’ focus and care creating a ceremonial environment. “You have to slow down,” she says of embroidery. “It’s like the slowest drawing you could do.” In these moments, the dress enabled individuals to have a close, if momentary, relationship with an endangered plant.

The one extinct species represented on the dress, the Santa Barbara morning glory (Calystegia sepium ssp. binghamiae), was declared extinct, believed to be rediscovered, and then determined gone again. Another species depicted, Furbish’s lousewort (Pedicularis furbishiae), was just downlisted from endangered to threatened in 2023. Both species reflect how Harvey’s dress is a

snapshot of endangered plants in an ever-changing world. The dress is a time capsule of endangerment—both hope and loss hang in the balance at the moment of its making.

Playing with time is central to the project. For example, Harvey chose the dress’s 1800s-inspired design as a reference to the century in which the current exponential rise in species extinction began. The dress presents a metaphorical collapsing of time in which we see a symbol of the beginning of the sixth mass extinction, along with images of what is at stake today. The dress reminds us that endangerment has a history.

A need to forge a personal connection with climate change may sound obsolete now that extreme weather events touch nearly everyone. Harvey even laughed when describing that initial impetus for the project, a reflection of how much has changed so quickly. But the connections that might be made with plants through methodical, even ritualistic, attention can be enduring. As Harvey brings this project to an end, she’s moving from the past to what may lie ahead. For her next project, she is “thinking about a future world where plants and humans are connected in ways that might be more fanciful than they already are.” Perhaps she has grieved the loss of these plants and is choosing to embrace hope for their future and for our future with them. ◆ Matthew Harrison Tedford

Liz Harvey’s “the lost ones” is on view at the New Museum Los Gatos, as part of the exhibition the lost ones: iterations and murmurs , through April 14, 2024.

Grow community with nature through volunteer land stewardship opportunities for your business, school, or community organization.

Root your child in nature with nature camp & environmental education.

Get outside at our preserves, gardens, & partner properties for outings in English & Spanish. Our 2023 Impact Report is out now! Scan the QR code to explore it.

Visit Bay a rea coastal scrub or chaparral in spring to find these particularly Californian habitats at their most welcoming. It’s when their soft sages, chamise, ceanothus, and other low-lying plants start to unfurl, early wildflowers peek out between green grasses, and the earth is soft and moist underfoot. Chipping and chirping, towhees and scrub jays set and defend their territories amid the plants and practice their mating songs.

Wander along and you’ll soon find the ubiquitous coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis). A distinguishing species of coastal scrub and chaparral, it hides and shades birds and mammals and wicks dew from the air, sending it down into the soil during the dry season. But an overlooked herbivore, perhaps the shrub’s greatest Achilles’ heel, can defeat this hardy plant’s defenses: the glittering and exquisite coyote brush

leaf beetle (Trirhabda flavolimbata).

When you find coyote brush, and if you look closely on a spring day, you may catch the emerald gleam of this beetle. Once you see one, you’ll likely spot these representatives of the subfamily Galerucinae, skeletonizing leaf beetles, around the immediate area. Skeletonizing leaf beetles are just what they sound like, insects that masticate the soft tissues of a leaf, leaving behind the harder stem, veins, and midribs. Larvae of this beetle subfamily amass on their host plants, feasting on growing leaves, living and mating during the plant’s peak growing season, laying eggs, and dropping frass (invertebrate poop).

Dominating a Bay Area coastal scrubland landscape is no easy feat for any species. It includes adapting to hot and long dry seasons, invasive grasses, a semi-frequent fire cycle, and herbivores for every

season. But the coyote brush is equipped with considerable advantages. Its crown root can reach down as far as 10 feet into the soil, and lateral roots spread in every direction, collecting groundwater long into the dry season. The plant can resprout after a low- intensity brushfire if the root stem remains unscathed. Waxy leaves, impenetrable to many invertebrates, are just plain unpalatable to deer. Its flowers attract parasitic wasps that prey upon other insects that might eat the shrub.

Yet the coyote brush leaf beetle makes this inhospitable plant home during every stage of its life cycle. Hatching from eggs in February, blue-green and shining larvae climb to the buds and leaves of the coyote brush, where they will eat and grow unceasingly for several weeks, nearly reaching the length of an almond and half the breadth. Small but strong jaws

allow the beetle larvae to succeed where other invertebrates would not, chewing through the waxy coating of the shrub to unlock nutrients inside. A telltale sign coyote brush leaf beetles and their larvae have visited a bush are the semicircles they chew along the edges of leaves.

The larvae and beetles’ beauty belies a mystery: though they shine and glisten in the sunlight and congregate on bushes that birds may visit, such predators often leave them alone. How can this be, when other beetles and larvae are prized treats for spiders, birds, small mammals, wasps, and even some beetles such as predatory rove beetles?

A clue may lie in the close relationship with its host plant, according to research by Wilhelm Boland of Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Germany. Think of how the famed monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) sequesters toxins acquired from milkweed within its body to protect itself from predation. One experience eating the vomit-inducing compounds that the butterfly stores convinces most predators to steer clear of the large, orange-bannered monarch. Similarly, our leaf beetle wields a truly complex and bizarre defense mechanism—and one that is even more powerful.

A coyote brush leaf beetle absorbs chemical compounds from coyote brush into its hemolymph, the insect’s circulatory fluid. The compounds are transported to one of many glands that act as generators and reservoirs for the animal’s defensive chemical munitions. This series of glands contain enzymes that convert the compounds into a precious toxin that is harmless to the beetle. Unlike the monarch, the beetle doesn’t sacrifice its life: leaf beetle larvae can secrete noxious and toxic droplets on demand from

the glands, later reabsorbing it. The smell and taste of these secretions is intended to ward off most predators.

When a beetle larva is fully grown, it crawls to the soil, burrowing underground to pupate and metamorphize. Its body will harden, and many parts will begin to soften, deform, or even liquefy. Within two weeks, it emerges re-formed as an adult, about a third of an inch long. If you thought that was the end of the ordeal for the coyote brush, you’d be mistaken: the adults too feed on the plant, though they’re less

enough to render the wearer impervious to almost any assault. For the toxin-sequestering Trirhabda flavolimbata, a glimmering green shell could become synonymous with a dangerous and disgusting meal. As adults, they can be found congregating on coyote brush, chewing on leaves and flying short distances between host plants as they look for mates and opportunities to feed.

So you wouldn’t be faulted for wondering: how does coyote brush survive the onslaught of this hardy herbivore year after year? Coyote brush enjoys an exceptionally long growing season, as its waxy leaves resist drying out and deep roots draw moisture into the summer.

voracious and less numerous than the larvae.

A full quarter of all known animal species are beetles, and the design of the armor worn by adults makes them especially robust. Their curved, tough exoskeletons can prevent the jaws of small predators, like lacewing larva, ants, or spiders, from finding purchase, and are often hard

Leaf beetles can be sensitive to fire and to frost, as well as to certain predators. This beetle also seems to only sustain its population on coyote brush, and beetles eat large amounts of the plant during their four- to six-week larval stage. If the plant has been burned low or otherwise had its growth disrupted, the beetle may be starved out in a region. The plant will likely recover later.

Unlike some leaf beetles in the family Chrysomelidae, Trirhabda flavolimbata reproduce only once a year, laying eggs in the soil before it is dry. The layer of soil can protect the eggs from the summer’s heat and the frosts of winter. The eggs give rise to voracious larvae once the coyote brush is rapidly growing during late winter and early spring, a characteristic of the scrublands. Because the larvae are the most destructive stage of the beetle’s life cycle and are present for only about a month, a healthy coyote brush will likely survive the insects and recover after the beetle’s season of feasting. ◆

Each year the Bay Nature Institute board and staff select remarkable individuals to honor with a Local Hero Award in recognition of outstanding work on behalf of the natural world of the San Francisco Bay

Area. The 2024 recipients will be celebrated during the 14th annual Bay Nature Local Hero Awards event from 2 to 5 p.m. at the David Brower Center in Berkeley on April 7. BayNature.org/local-hero-awards-2024

young leader naji lockett

Fallen oak branches, tangles of dense undergrowth, heaps of eucalyptus bark, and packed stands of fir trees cover thousands of acres of public land in the East Bay. Scrambling to lessen the risk of wildfire and clear overgrowth, park agencies and public utilities are contracting help. And Naji Lockett is a hot commodity in that market.

Naji leads young crews who cut and pile that vegetation for later burning or chipping, while keeping an eye out for woodrat nests and other important wildlife habitat. These are long, eight-hour days, sometimes in the rain or intense heat, and it takes a certain secret sauce to keep a crew motivated.

“I’m just working alongside them, so they can get a better understanding of how the work needs to be done and have a good work ethic,” says Naji. “This is a hard labor job … but I just let them know, ‘You’re making a big difference doing this type of work, for the safety of others and the earth itself.’”

At age 24, Naji is the youngest staff member at Civicorps, a nonprofit in West Oakland modeled after the New Deal-era Civilian Conservation Corps. The organization trains 18- to 26-year- olds who live below the poverty line for green jobs, ranging from land management to recycling collection. Naji grew up nearby, close enough to walk to the Civicorps HQ, and started the Civicorps training after finishing high school. Almost two years ago, he accepted a staff position to manage the training crews he’d started in, bringing a calm, empathic leadership style. “Naji has a lot of grit,” says Steven Addison, Civicorps’ conservation program manager. “His path is one people look up to.”

There was a day in Tilden Regional Park, Naji recalls, when his crew was working in the rain, and people were cold, and they started to share stories. “We kind of bonded and built more fortitude, hearing the good and bad about everyone. We’re all going through stuff. And just being humane … like, ‘I’m thankful you understand my situation and don’t judge what goes on outside here, but just respect my work ethic.’” Civicorps cleared almost 1,000 acres in fiscal year 2022.

All the time he’s spent in the parks has Naji envisioning more nature in West Oakland: “If things were a lot more maintained,” he says, “there would be more nature and wildlife would come.” And he has a quiet hope that the community can learn more about ecology, about how “certain plants attract certain insects. And if you can bring insects around, birds come—and if birds come, they’ll nest … just knowing that cycle.”—Victoria Schlesinger

“My mother was one of the first people in my life who, when I came back from my treks in the Himalayas, she would say ‘નૂર, તમારા ચહેરા પર નૂર છે,’ a Gujarati phrase for ‘there’s this Noor, or glow, on your face,’” Yakuta says. “ I want to see that in every person I interact with—every single human being. That’s what inspires me.”

As associate director of community stewardship and engagement for the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, Yakuta brings this glow and nature to others. Her path has come full circle, from a journey that was far from linear.

Yakuta grew up in a Dawoodi Bohra Shia Muslim community in Pune, a city in western India. Around the age she first hiked in the Indian Himalayas, she began questioning the patriarchal institutions and inequities in her community and beyond.

Independent and inspired by the environment, she went from leading youth trips through the forests of India to attending graduate school to moving to San Francisco in 2010 and working for the Sierra Club, then joined GGNPC a decade ago.

At least twice a week, she and her team of 12 invite local Bay Area communities to experience nature in the parks—often for the first time. The team facilitates events such as health and wellness walks at the Presidio, wildflower walks at Mori Point, birding outings at Hawk Hill and Rodeo Lagoon, and partnerships with local public libraries.

Other programming connects themes in nature with international holidays such as Holi and Diwali, Hindu celebrations of color and light; Día de Los Muertos, the day to honor the dead in Mexico; and Eid, an Islamic festival marking the end of a period of fasting and prayer. Yakuta encourages people to celebrate the multicultural landscape of the Bay Area and to see themselves— and their cultures and customs—in nature as they plant native species, tend parklands, and learn about local wildlife.

Yakuta also promotes access to the outdoors through resources like GGNPC’s Roving Ranger and facilitates discussions about questions like “what kind of ancestor do I want to be?” She serves on the board of TOGETHER Bay Area and is a member of the California Landscape Stewardship Network’s Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Roundtable, among other organizations.

By connecting Bay Area communities with each other and the outdoors, “we’re creating Noor in nature,” Yakuta says. “I can sense it now when there’s a grandmother from the Tenderloin, from the Arab Muslim community, who’s lost her home … but then she comes here and finds a connection with the Rose Garden, for example, because she had a rose garden in her community.”

“Programs in the park allow us to see ourselves not as alone, not as individuals, but as part of a collective,” Yakuta says. “And that in itself is so powerful.” —Lia Keener

San Francisco State University’s Estuary and Ocean Science Center (EOS) in Tiburon, did not grow up near the ocean. But at summer camp on the Chesapeake Bay, at age 11, she dug into the sand—and marveled at its treasures. Clams! Then she wondered what else was down there, and why it stank. She met people, too—oyster farmers and crabbers—who made a living on the bay. Here was a whole gorgeous world sparking her curiosity. “I was just smitten,” she says.

Now she’s the one revealing the shoreline’s treasures to young people. Some are high schoolers or community members from underserved groups, helping to build experimental reefs or restore eelgrass in San Francisco Bay and learning that climate change can mean jobs. Most are SFSU master’s students. Katharyn inculcates in them skepticism and the principles of ecology, and also how those principles work in the real world—dragging them to meetings with government officials, for example. There is no textbook for her class on restoration ecology, because everyone, Katharyn included, is scrambling to figure out how to achieve it. How to bring back our shorelines, and keep them alive in the face of a rising sea, in all their dynamic messiness. And how to do it fast. “We need to come up with the elegant experiment, or survey, or monitoring project, that helps us get that clarity about how to move forward,” Katharyn says. “I feel this really extreme sense of urgency.”

of sand will stay put when the tide comes in, how a concrete reef can be made light enough for one person to handle. (For Katharyn wants the community, not just cranes, to rebuild our shorelines.) On the board outside Katharyn’s mud lab, a student tacked up a sign: “GET DIRTY.”

Lately, Katharyn has focused everything on saving the EOS, one of the few science labs where such questions can be answered. In 2022 SFSU’s administration declared the 45-year-old center would have to scrounge up its own funding to stay open. Katharyn’s team began churning out grant applications. Money has begun to come in. She aims to make shutting down the center an impossibility.

In a blustery winter rainstorm, just off a dock that was once the U.S. Navy’s property, pelicans preen atop the lab’s experimental reefs, where they poke above the water. Drop a simple structure—bags of oyster shells, or big concrete wiffle balls—and complexity moves in. Life loves irregularities. “There’s room for your amphipods and your isopods and your worms, and your algae and your bryozoans, and whatever else. Mussels, sometimes,” Katharyn says, still marveling at the treasures. Then the fish, and the pelicans. Make it appealing enough, and they can hardly say no. —Kate Golden

w hen she drives down the San Mateo County coast, Kellyx Nelson doesn’t see a piece of land she hasn’t touched. She sees more than 10 dams removed, 500 acres of natu ral and working land that support carbon sequestration, and miles of creeks and watersheds restored—and that’s just the beginning of the work she’s done as the executive director of the county’s resource conservation district, or RCD for short.

Kellyx describes the RCD as connective tissue—a special dis trict, created by the state, that nimbly supports other players in the landscape of conservation. Despite the RCD’s size, the role inspired her. “Here’s this entity that exists not to take anything from anyone, not to regulate anyone, not to shame anyone, not to litigate anyone, but to help people.” Like a hopeless romantic, she jumped ship from the Peninsula Open Space Trust, abandon ing a burgeoning career inside an extremely well-funded entity to work in an office with no staff, no money, no projects, and a “very bad reputation.” From there, Kellyx became Resource Conservation District. And 18 years later, with a grow ing staff of 26 and a budget nearing $19 million, she’s still seen by some as its symbol.

“People always give me the impossible projects,” Kellyx says. Like the restoration of Pescadero Marsh, a thorny problem whose brackish waters had brought about a standstill mix of conflicting interests, differing jurisdictions, and pointing fingers. The key, she says, is listening, and taking an all-inclusive view of con servation: she sees farmers as stewards and thinks conserva tionists, developers, and even people who hate “enviros” can work together. “You don’t have to choose between the people and the land.”

The real enemy, she says, is bureaucracy. Getting a restoration project permitted, funded, and completed often hinges on perfect timing and a herculean effort—but Kellyx doesn’t think it should. In 2019, she helped found the Cutting Green Tape initiative, which has brought together federal agencies and nonprofits to discuss making restoration work easier. The species they’re protecting, like steelhead and red-legged frogs, “don’t know what juris diction it is,” Kellyx says. “News flash—birds fly, and frogs hop, and fish swim.” And they should get to do so freely.

Kellyx is a connector, even from her living room. Our conversation, happening across a repurposed children’s play table, is interrupted frequently. Neighbors come by to drop off their kids. Her own kids make calls to their friends. She often takes them hiking in the Sierra, or camp ing in Joshua Tree, or road-tripping across the country to national parks. “I guess if I have an image of myself, it’s always with kids and the outdoors, even though it’s not what I’m doing anymore.”

Or maybe it is, but with grown-ups and a little closer to home.

conservation action kellyx nelson

conservation action kellyx nelson

On a warm September afternoon at her home in downtown Sacramento, JoEllen Arnold sits at her table where a wall of windows overlooks her backyard’s wildlife garden. She is laying out tools: thick leather gloves, a dish of wriggling live mealworms, tiny syringes filled with a paste of food and water, a stack of clean, soft rags, and her digital scale that measures in grams. Arnold, a 74-year-old retired schoolteacher, rehabs injured bats. It’s a daily ritual of feeding and tending that will take an hour or two. Like a lactation consultant with an underweight newborn, Arnold weighs each bat before and after its feeding to determine how much food it has taken in. She keeps meticulous records, carefully logging the details in her notebook.

Arnold gently grips one of her rescues in a gloved hand, a female hoary bat called “Lodi,” named for the city where she was rescued. A passerby found Lodi on the ground with a compound fracture in her left elbow in April 2021. Lodi’s tiny face now rests on Arnold’s index finger, while in her other hand Arnold wields a miniature grooming tool—an unused mascara brush—that she maneuvers between the bat’s rounded ears. The colors in Lodi’s luscious fur coat glow in the window light—dark brown, reddish-blond, and white. The frosted white fur tips account for the “hoary” in her species’ name.

Lodi’s extra-thick fur keeps her warm, a necessary adaptation since hoary bats don’t roost in colonies. Instead they are solitary roosters, hanging alone in trees, and sometimes mis -

taken for pine cones. Their color pattern helps to disguise them as bark and leaves. While all rehabilitating bats need their fur checked and groomed occasionally, Lodi’s fur needs extra attention. She does not hang upside down well, so she sleeps with her feet propped up on a piece of bark and ends up lying in her own poop, which gets stuck in her fur. Grooming sleek coats, offering wriggling mealworms with tweezers to hungry bats, and waking up every two hours to feed orphaned newborn bat pups are all routine for Arnold.

“If we don’t care for them, the bats will die. If a bat is injured or sick, they can’t care for themselves and it will die. I can’t stand that thought,” she says. For the past decade, she has volunteered, along with about a dozen others, for NorCal Bats, a nonprofit dedicated to rescuing, rehabilitating, and releasing bats throughout Northern California. “I really hope that everywhere bats live, they can be cared for,” Arnold says.

Tending to the suffering of individual injured bats and nursing them back to health means Arnold and other bat rehabbers spend a lot of time getting to know many of the 17 bat species that live in Northern California. They use that insight to educate the public through frequent walks and presentations, but their years of field experience and health data also make for an unusual bridge between people passionate about bats and the biologists documenting the threats to an entire order of mammals. The rehabbers “give us a window into the wild world, into parts of the ecological

HEALERS flowers bloom in spring, the bats the calls for help to NorCal Bats.

picture that we as scientists may not have without focused studies,” says Leila Harris, a wildlife biologist, bat ecologist, and PhD candidate at UC Davis.

More than half of North America’s 154 bat species are at risk of severe decline, according to the first North American Bat Conservation Alliance’s “State of the Bats” report, published last year. Bats are vulnerable to climate change, collisions with wind turbines, and habitat loss. Millions of hibernating bats in the United States and Canada have been killed by the fungal disease whitenose syndrome since 2007. They also suffer from the fear and disregard of some people.

In January 2023 , in between a series of atmospheric rivers, NorCal Bats received a call that Mexican free-tailed bats were trapped inside a trash can outside a building in Rancho Cordova, east of Sacramento. A concerned bystander had watched in disbelief as a building maintenance worker removed a sign from the exterior of the building where bats were known to roost, according to NorCal Bats. As the sign came down, Mexican free-tailed bats sleeping behind it fell to the ground. They were then scooped up and dumped into a trash can that was filled with wire, broken glass, cigarette butts, and water, and left to die.

The bystander tipped the trash can onto its side and between 30 and 50 bats crawled out and flew away. A NorCal Bats rescue volunteer arrived on the scene to find nine bats still at the site.

Two had already died, one was ultimately euthanized due to its abdominal injuries, and another was taken to the vet with wing injuries. Five more fell under the care of NorCal Bats volunteers until after the winter storms and were then released. The incident was reported to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife CALTIP program, and, NorCal Bats staff say, a CDFW warden talked to the building’s staff about ethical methods of removing bats and the devastating impacts of disturbing roosts, which is illegal. Bats are nongame mammals and have protection under the California Fish and Game Code.

“Sometimes, people choose to kill them just because they’re afraid and … they don’t understand that there are ethical ways of removing them,” says Mary Jean “Corky” Quirk, who founded NorCal Bats in 2006.

Each time a bat is rescued, NorCal Bats sees an opportunity to educate the bat’s “finder” about bat ecology and conservation. Bats that can’t be released into the wild become ambassadors for their educational programs. NorCal Bats partners with Yolo Basin Foundation to lead a regular bat walk and talk program at the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area throughout the summer. It also makes presentations at schools and libraries and for various organizations year-round and has information tables at events such as reptile shows, bird festivals, and UC Davis Picnic Day. NorCal Bats has permits from CDFW and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to house live, non-releasable bat ambassadors.

Lodi became one of these ambassadors. Her wing was amputated after her elbow fracture injury, making it impossible for her to survive in the wild. Hoary bats are a relatively uncommon species yet are the most geographically widespread bat in North America.

“When people get to see a bat’s face for the first time, everything changes for them,” Arnold says. The hoary bat’s face is described as “a mix of very beautiful and ‘Um, what kind of dog is that, anyway?’” by authors Charles Hood and José Gabriel Martínez-Fonseca in their new book Nocturnalia.

Once Arnold finishes grooming Lodi, she delicately places her inside a portable butterfly enclosure. Arnold zips the lid closed, carries the enclosure out to the backyard, and hangs it from a tree. She sets a timer for 45 minutes—enough time for a good dose of vitamin D.

When Ted Weller, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service, and his team first attached GPS trackers to hoary bats in 2014, they made a surprising discovery. Instead of moving in a linear

What to do if you find a bat?

• Never handle a bat alive or dead with your bare hands.

• If you think a bat is sick or injured, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation facility.

Want to create habitat for bats?

• Spring is the best time of year to install bat houses. It’s when some bats are moving from their winter roosts to their summer grounds, so they are more likely to move into the structure.

• To learn more about bat houses, check the websites for NorCal Bats or Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation.

• Plant natives that support local insect populations.

• Install a wildlife escape ramp in water features, such as pools or fountains, that allow a bat, or any animal that falls in, to get itself out.

A quarter million migratory bats roost in the expansion joints on the bridge during the day.

direction toward warmer climates for the winter as biologists had assumed, male hoary bats made long-distance flights in various directions and sometimes hibernated for the entire winter.

Starting in fall of 2022, Weller and his team began using the Motus Wildlife Tracking System to study hoary bats in partnership with CDFW, the USFS, and the U.S. Geological Survey. While the bats are under anesthesia, small lightweight radio transmitters are sutured to their backs, to communicate with a network of towers. Because hoary bats roost in trees instead of caves, these solar-powered trackers recharge in sunlight and can continue to work without a need to recapture bats for battery replacement.

Arnold virtually attended a recent Bats Northwest talk where Weller discussed his ongoing research. She brought her rehabilitator’s lens to the discussion, inquiring about the safety of the sutures and whether they pose a risk of infection to the bats.

Wildlife rehabilitators have a useful role, alongside scientists and conservation managers, in improving understanding of bat ecology. Detailed records like Arnold’s often go back years, documenting the date pups are first received into care or the time of year particular species are brought in for help. Harris is using rehabber records for a current study of prenatal exposure in bats to contaminants. The records help her predict exactly when to start checking maternity roost study sites in various areas and for different species. “For statewide projects in particular, where phenology can differ markedly between, say, SoCal and NorCal, and you have a small crew, local and long-term knowledge like this can be a really useful piece of the puzzle that helps extend limited conservation ecology research dollars,” writes Harris.

To plan for this summer’s fieldwork, Harris will contact bat rehabilitators for estimated pupping dates at roost sites throughout the state. “When rehabbers are able to compile consistent and accurate records over time, these can add to our overall body of knowledge, and even if not statistically robust on their own, can provide initial observations that suggest directions for future research,” she writes. “We need to honor their information and contributions to our understanding of this complex group of mammals.”

The volunteers with NorCal Bats know that any of the region’s local species might end up in their care. They may get pallid bats, our scorpion-eating new state bat; on rare occasions the mastiff

bat, the largest in the U.S.; or Townsend’s big-eared bats, which, like pallid bats, are referred to as “whispering” bats due to their low-intensity echolocation. Recently there has been an influx of canyon bats, among the first bats to emerge each evening to eat flies, moths, beetles, and other insects. In a typical year, NorCal Bats cares for about eight or nine species, though it varies year to year. But volunteers rescue Mexican free-tailed bats more than any other, due to the sheer quantity of them in the wild and their propensity to live in buildings and bridges, making them much more likely to encounter people.

“When people get to see a bat’s face for the first time, everything changes for them.”

Spring is a transition time for bats. As the insects come out, the bats become more active. It is when some species relocate from their winter homes to their summer homes. It is an ideal time of year to install bat houses, as they are much more likely to be occupied. By summer, bats have already settled into their summer roosts, and by fall they are relocating to save energy as temperatures drop. In winter, they don’t fly every night and when they do, it is usually after dark.

The seasons also bring particular challenges for bat rehabbers. NorCal Bats expects more rescue calls during extreme weather events. Cold temperatures and winter storms increase the number of bats in distress. High winds can break the tree branches where hoary bats roost, causing them to end up on the ground, where they become susceptible to house cat attacks. Extreme heat in the summer can also be deadly, especially for bat pups. When Mexican free-tailed pups overheat, they try to cool off by leaving their roosts. “They cling to each other in chains,” Arnold says, “and when the top pup falls, they all fall.” Sometimes hundreds of pups careen to the ground this way during a heat spell.

Back at her worktable, Arnold moves on to tend a Mexican free-tailed bat nicknamed “Sneezy.” She places a drop of water in his mouth to hydrate him. To be ready for release, a bat needs to

To be ready for release, a bat needs to consistently eat well, maintain a healthy weight, and fly in the “flight tent” set up in Arnold’s basement.

consistently eat well, maintain a healthy weight, and fly in the “flight tent” set up in Arnold’s basement. She monitors flight progress remotely with a video camera, identifying each bat with UV lipstick that shows up under black light in the tent.

The Yolo Bypass in Sacramento Valley is the summer home to the largest urban colony of Mexican free-tailed bats in the state. A quarter million migratory bats roost in the expansion joints on the bridge during the day. Then, at sundown, they emerge together, forming long columns silhouetted against the fading glow of the sky. The bats disperse to hunt for moths and other insects, reaching speeds of up to 100 miles per hour. After hunting throughout the night they return individually and anticlimactically.

“I have a soft spot for them. They get along with anybody. They don’t really care if you’re even their own species. I think that’s kind of cool,” says Quirk. “They live in massive colonies. They know each other. They know their friends. They know their family. They eat so many crop pests. They’re very beneficial to us, and often, people don’t realize how important they are to agriculture and reducing pesticide use.”

Summer is pupping season at the colony and lactating female Mexican free-tailed bats can eat their weight in insects each night. It is also an intense time for Arnold because caring for the newborn pups means feeding them formula every two to three hours day and night. Fall brings new challenges for (continued on page 45)

Spring is a transition time for bats. As the insects come out, the bats become more active.Pallid bat Big brown bat

One of Kimberly Stevenot’s responsibilities as a kid was to hang out by the side of the road and look for park rangers—or anyone else who looked like they might be trouble.

The Tuolumne Rancheria, where many Northern Sierra Mewuk had lived since they were forced out of their homes, was granite and solid red clay. It was about as bad as a place could be for growing anything. So her family snuck around to the few places where the plants they had gardened for generations still grew. Many of those places were in state and national parks.

Those places were better than nothing, but not great. The parks were overgrown, and the plants needed hand-weeding. Controlling weeds with fire, the way the Mewuk used to, was too risky—so much as picking a berry in a state park without authorization put them in violation of California Code 4306. Later, when they learned more about pesticides, that was another worry.

But if they followed a river for long enough, past the long stretches of mining and dredging debris, past the riverbanks kept scrupulously bald for the purposes of agriculture, signs of the old California might emerge—tules, cottonwood, willow, and, in the high loam, valley oaks. A grove of valley oaks creates its own microclimate, a small planet of understory plants and fungi. One of these is the Valley sedge, Carex barbarae, a grass whose rhizomes are one of the most coveted materials for weaving baskets.

Thirty years ago, sometime after her mother died, Kimberly’s husband came back to their home in Modesto, radiant with excitement. He’d spotted something while driving through Caswell Memorial State Park. “I think I found your mom’s sedge beds,” he told her.

Cultivating sedge is a lot of work. People tend to keep their spots secret. If someone starts digging a bed and uncovers suspiciously long, straight rhizomes, they usually know better than

to take any—invariably another weaver will figure it out, and give them hell for it later. The sedge Kimberly’s husband had seen had roots all tangled up in its rhizomes. No one was tending it anymore.

Kimberly remembered how her mother and grandmother would follow the Stanislaus River downstream from the foothills of the Sierras, and the abundance of sedge they described finding there. She decided to go see for herself.

Ripa R ian fo R est is a R a R e sight in the Cent R al Valley. About one million acres of trees, shrubs, and grasses once flourished, drowned, and flourished again along the valley’s rivers, creeks, and floodplains; now, perhaps 130,000 acres remain. In recent years, though, that number has begun to inch up again. Caswell has about 260 acres. Seven miles south of there is Dos Rios Ranch—2,100 acres, much of it former dairy farm and almond orchard, at the extremely floodable confluence of the Tuolumne and San Joaquin rivers—which is steadily being restored to riparian forest. Later this year it will open as California’s first new state park in 15 years.

“I think of this literally as a park of the future,” says Armando Quintero, California Department of Parks and Recreation director. Today, a California state park has to deliver more than just a historical plaque or a scenic vista. Quintero cites Dos Rios Ranch State Park as an example of what the state’s ambitious 30x30 goals could look like—providing shelter during heat waves for wildlife, storing floodwaters, harboring endangered species.

Dos Rios is a test of California’s ability to adapt to the future—and learn from the past.

But it will also be one of the few public parks in an area that has grown rapidly in population with no commensurate growth in open space. Valley residents, many Latino and low-income, have never had the same access to public lands as people who live on the coast. Native inhabitants of the valley have lost so much that the scale of it is difficult to even imagine. Quintero has heard that one of the almond orchards at Dos Rios will stay a few more years—that particular lease isn’t up yet—and he’s delighted about that too. “You don’t usually have a park that has a piece of the agricultural story of the Central Valley,” he says. “We used to say ‘man and nature’ and that always made me pull my hair out. Because man is nature, right? This park is going to be telling a fuller story of California.”

In a larger sense, Dos Rios is also a sign of how much California’s idea of nature is shifting. Dos Rios is becoming a wild space in a landscape that has very little of that. But it also is home to a native-use garden, where Indigenous people can gather culturally important plants without permits, and it will be tended in ways, like traditional burning, that would have been flagrantly illegal a few decades ago. “Our native wildlife, our native butterflies and beetles and bees all lived in that same cultivation space with California people for thousands of years,” says Julie Rentner, an ecologist and the president of River Partners, the nonprofit that bought this land to restore it. “They’re all adapted together.”

Until the 1850s most of Califo R nia was, basically, a nativeuse garden. One of the most vivid descriptions of what that looked like, at least in one part of the Central Valley, comes from interviews done a century ago with Thomas Jefferson Mayfield, the child of white settlers who was taken in by local Choinumne Yokuts in the 1850s after his father disappeared to herd cattle. Mayfield describes growing up in a wildly lush landscape where residents lived so well on acorns, mustard greens, tule roots, ground squirrel, deer, and other wild forage that everyone spent

hours a day playing agility games on a hard-packed sand court they’d built in the middle of their village.

By 1862, it was all over. Mayfield’s family had been only the first of many waves of squatters who killed or chased away the wild game, cut down the trees, brought in livestock that pooped in the waterways, banned fishing and foraging by anyone who wasn’t themselves, and murdered anyone who objected. The surviving Yokuts either left the area or eked out a living shearing sheep and doing laundry for the same people who had destroyed the system that they depended on.

i n the 1920s , at the request of the newly created State Parks Commission, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and a team of volunteers began traveling the state, looking for iconic California landscapes to parkify. Land was cheap (because of the Great Depression) and the state was flush with federal mon-

Mewuk baskets

These are serving bowls: willow foundation, sedge, bracken fern.

ey (because of the Great Depression). An opportunity like this would not come again.

Olmsted’s report to the Commission laid out the usual suspects: mountains, redwoods, coastline, desert. But he also made an impassioned case for preserving riparian areas for scenic, recreational, and ecological reasons that, he wrote, “would bring far greater dividends than the separate pursuit of one or more of these ends independently.” Former state parks director Ruth Coleman says that the Yolo and Sutter bypasses, a mix of farmland and open space that’s meant to flood, are the closest thing to what he was hoping to preserve.

But even before Olmsted made his trip, the Central Valley’s forests were nearly gone. A riparian forest is, by definition, next to a river, and the captains of steamboats puttering upriver through the Central Valley had few compunctions about pulling over and logging a bunch of trees to feed into their boiler rooms. In 1850, California, with exactly 19 days of statehood under its belt, got itself included in the federal Swamp Act, which gave it permission to dry out any “swamp and overflowed lands” (which, when wet, were federal property, like rivers) and sell the results. The transformation of the valley’s 15 million acres of grasslands, wetlands, scrublands, and forest turned a lush, mercurial ecosystem into something more squared off and controlled—a landscape that people now floor the accelerator driving through between the Sierras and the coast.

w hen Kim B e R ly was g R owing U p in San Francisco in the 1960s, her mother told her to never tell anyone she was Mewuk. Tell people you’re Filipino, she said. Otherwise no one will rent to us.

But during the fourth grade, after a lesson about the Spanish missions, and after the teacher said one too many times that all the Indians were dead, Kimberly went home and said that she needed to take some baskets to school and lay some truth on the class. Her mother reluctantly agreed. This was long before the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, and Mewuk could get harassed and even arrested for gathering.

Kimberly doesn’t remember how her classmates responded. She does remember that a student teacher, who was Native Hawaiian, let Kimberly know she was doing the right thing. “That was kind of the smoke before my fire,” Kimberly says, chuckling.

t oday, the s mithsonian C alls Kim B e R ly on the R eg U la R to consult about Mewuk history and culture. While she was on the board of the California Indian Basketweavers Association, she worked with the national parks system and California state parks to legalize native gathering—no more child lookouts, no more sneaking around. She could go to the same sedge beds that her mother and grandmother had used, but legally this time.

Or at least she could in theory. A few months after the permit was developed, Kimberly drove out to see the county’s park district supervisor and get her permit signed. When she found him, the supervisor informed her that he had never heard of such a permit. Also, he added, Caswell’s sedge was off-limits, because the park was home to a very special and almost extinct creature

known as the riparian brush rabbit.

“Excuse me?” said Kimberly. “You are talking to one of two Mewuk traditional basket weavers here. You want to talk extinct?”

f o R the past C ent UR y, state parks have run on a boom-andbust cycle—funded when times are good, hung out to dry when times get tough. In the late 1970s, California started “trimming back everything except prisons,” says Richard Walker, a historian of the conservation movement in the Bay Area. California also has a long-standing habit of trying to pay for crucial environmental priorities with bond measures, adds environmental historian Jon Christensen. That includes parks and conservation, but also clean water (2014’s controversial Prop. 1) and climate adaptation (on the ballot in November 2024).

One consequence of that unpredictability is that even though Dos Rios has been floated as a possible state park since at least the late 2000s, it was ultimately a nonprofit—River Partners— that pulled together the money to buy the site, with the hope of one day handing it over to a public lands agency. There were no guarantees. “It can be competitive,” says Rentner. “There’s really beautiful properties on the coast and in the forests that would love to become state parks.”

“Bond after bond after bond would come and go, and the money went to the coast,” says Ruth Coleman. As state parks director in the 2000s, she spearheaded the Central Valley Vision Implementation Plan, which sought to develop more state parks in the valley. “If you looked at a map of the California state park system, you will see a bazillion dots along the coast and a lot of dots in urban areas. You will see very few dots in the Central Valley.”

It took River Partners over five years to pull together $22 million in funding to even start the process, from sources like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the California Wildlife Conservation Board, the state Department of Water Resources, the California River Parkways Program, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and the U.S. Bureau

California’s Central Valley was transformed dramatically by European settlers in the 19th and 20th centuries. Now, so much water has been spoken for that habitat restoration focuses on landscapes less dependent on year-round surface water—fewer lakes and marshlands, and more forest, shrublands, and grasslands.

Pre-1900s

2010s

California's coastal counties have one-third the area of the inland counties, but more than twice as many parks.

Inland

Coastal 83 193

Excludes eight parks that span inland and coastal counties. Data: California State Parks.

of Reclamation. River Partners commissioned site analyses, and planned how to un-level the land, and decided which plants would go in where, in what order. They pulled out the concrete riprap, which had been dumped on the riverbanks to keep the river from spreading out. They put in an order for 2,400 pounds of locally adapted native seed (only to find, when it was time to plant, that the price of that seed had tripled).

Each funding agency governed some different angle—navi-

gable waterways, public spaces, endangered species, flood risks. “We had to go through hydraulic analyses to prove that the trees were not going to impede floodwater conveyance,” says Rentner. “It’s intense.” Getting permits to begin restoring the wet side of the levee took four years longer than the permits for the dry side. River Partners had to navigate at least eight overlapping regulatory processes just to get permission to plant trees next to the river. Coleman worries 2024 could be a return to the bad old days of

parks funding. But she’s heartened by the fact that Dos Rios has to be so many things to so many people. Because it plays such a variety of roles—biodiversity, public health, climate adaptation, groundwater recharge—it can pull funding from a wide array of sources.

Dos Rios is also a trial run for how the Central Valley will adapt to climate change. Its 2,100 acres make it large for a park in the area. “I think Dos Rios is going to have untold ecosystem benefits we haven’t even begun to understand,” says Coleman. Ten percent of the irrigated farmland in the San Joaquin Valley needs to come out of production by 2040, as water becomes scarcer. That land could become mango farms—or, as is happening in Kern County, to the south, it could become Amazon fulfillment centers. Or it could be an early link in a chain of riparian restorations along the rivers of the Central Valley—a massive wildlife corridor for migratory birds and other species, as well as a hedge against future droughts and flooding.

i f yo U a R e going to B e C ome a state pa RK , a lot of species will come to rely on you. There are the riparian brush rabbits, sure, but also the riparian woodrats (also endangered) that make little houses for themselves out of sticks. There are neotropical migratory songbirds, which stop here on circuits that can stretch from the Brazilian Amazon to western Canada . There are young chinook salmon, which like to forage for insects, amphipods, and other crustaceans in the relatively still waters of a floodplain, instead of getting banged up in some fast-moving stream.

And there are—well, there will be—humans. A lot of them— from kids spending their first night camping in the outdoors to birdwatchers, to trail runners, to friends and families looking for an affordable space to gather, to locals trying to get cool in the broil of summer, to school groups for whom this landscape and its history are going to become their lesson plan. People who never even visit the park will benefit from the floodplain’s ability to capture and store groundwater and reduce the risk of flooding downstream. If the city bus that makes it all the way out to Shiloh Elementary School in West Modesto can go another two miles, there will be the people who ride out here on transit, or on bikes. The average Modesto resident makes about $33,000 a year—about two-thirds the California average. Sixteen percent of city residents, and 20 percent of children, live below the federal poverty line.

Julie Rentner grew up on the outskirts of public outdoor space like this—near Mount Diablo, which owes its continued wildness to California’s public lands buying spree in the 1920s. “I grew up with crazy privilege, not because my family’s rich,” says Rentner. “I didn’t go to jail as a teen probably because I had access to open space.” Then Rentner, as people do, grew up and fell in love with a guy who enrolled at UC Merced.

Rentner was not sure how to process 1990s-era Merced. The air was bad. The water was bad. Nobody had access to open space. Then she saw a job posting for an ecologist.

The instructions for getting to the interview were this: Drive to the end of Dairy Road, and look for the pickup truck. “I got

in with the field manager, Stephen Sheppard—this really unassuming tomato farmer from Chowchilla,” says Rentner. “He goes, ‘We’re just going to show you one of our projects, and see if this is something that you think you’d like to work on.’ ” Sheppard drove up a levee, and a vista opened up beneath them. “Three thousand acres of beautiful marshland and forest,” says Rentner. “All clearly just restored. I said, ‘What the heck are you guys up to?’ ” Rentner had studied forestry at UC Berkeley. At no point had anyone mentioned to her that there used to be forests in the Central Valley. But here one was—the beginnings of one, anyway.

Kim B e R ly fo U nd o U t a B o U t d os Rios in the fall of 2019, when Rentner met a niece of hers and invited the family to come out and talk about native uses of the plants that were being put in on the land. People involved in the restoration understood the role these plants were playing ecologically, but wanted to know more about their usefulness to the cultures that had tended them in the first place. “We brought all our baskets, everything, out here,” says Austin Stevenot, Kimberly’s son. “I’d never heard of River Partners. I live in Modesto, which is 12 minutes that way. There’s 2,000 acres here being restored. And I’m like, ‘Who are these people? What the hell is going on?’ ”

Rentner talked about making Dos Rios available for native use, without permits. “Philosophically,” she said, “this restoration we’re trying to do is actually just our impression of what a cultivated natural community in California looks like.”

“They explained everything to us,” says Kimberly. “Every time I think about it I get really emotional. It’s weird.”

“The entire time, I’m thinking, I gotta work for these people,” says Austin. “Afterwards, I went up and I talked to Julie. I’m like, ‘Hey, you guys hiring?’ She goes, ‘Funny thing, I was gonna ask if you’re interested in a job.’ ”