EXTREME FLOWERS | 25 BAY AREA TRAILS | JUMPING SPIDERS

LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER Summer 2025

LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER LOOK INTO NATURE AND UNDERSTAND EVERYTHING BETTER Summer 2025

Swim the Bay

Explore 25 Trails

Smell Summer Blooms

Taste Wild Herbs

Spy on a Snake

One of California’s last great coastal wetlands, Elkhorn Slough is still under threat. Learn more about how you can preserve and restore Elkhorn Slough for generations to come.

Look close at a California mountain kingsnake's scales.

Welcome to Bay Nature ’s mini-guide to 25 Bay Area trails in some of our favorite places, ranging from peaks and valleys to redwoods and tidal marshes. Choose a trail and then visit the guide online, where each trail is kitted out with an interactive trail map and in-depth story from our archive.

By Bay Nature staff

Ever consider swimming in the San Francisco Bay? Since the pandemic, more people are suiting up and taking the (very cold) plunge into the world of open-water swimming. Learn about one woman’s journey into the briny waters that bind us and a passel of resources for getting started.

By Susan Kuramoto Moffat

There are 25 different kinds of snakes in the Bay Area, from boas to kings, yet catching a glimpse of one takes intel and patience. For the stealthy among you, this piece offers guidance and a bold claim: Snake-seeking, it’s the new birdwatching.

By Anton Sorokin

30

If you thought looking for wildflowers was a spring pastime, we invite you to explore the plants of the Bay Area’s scrub and grassland that bloom, despite all good sense and logic, during the hottest and driest times of year.

By Ken-ichi Ueda

25 accessible trails

All-terrain wheelchairs, motorized track chairs, and adaptive bikes—many developed by disabled innovators—are catching on in some Bay Area open spaces, making rugged trails and remote landscapes newly accessible to people with mobility disabilities.

By Bonnie Lewkowicz

29 wild herbs

Fennel. Sour grass. And wild garlic. All nonnative, prolific species that grow throughout the Bay Area and are tasty. Edible wild plant educator Cindy Li leads walks and creates videos to teach a new generation about these herbs, connecting with nature, and caring for the environment.

By jillian magtoto

42 connecting the bay area

The Bay Area is unusually fortunate to have three— three!—regional trails that grow mile by mile, and trailhead by trailhead, each year. Discover what’s new with the San Francisco Bay Water Trail, San Francisco Bay Trail, and Bay Area Ridge Trail.

By Tamara Sherman, Brittany Shoot, and Guananí Gómez-Van Cortright

Bring home the vineyard with a glass of Frey wine.

A fascinating and personal look at the condor population, the natural world around it, and the human interventions that have prevented its extinction.

- Cintra Wilson, author of Colors Insulting to Nature

p. 20 Susan Kuramoto Moffat has written for the Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Associated Press, and Estuary News from places including Tokyo, Seoul, Southern California, and San Francisco Bay Area. She is working on a book about urban wilds.

p. 12 Jacob Saffarian, born and raised in the East Bay, works as a science communicator. During his time as a marine researcher with UC Berkeley, he picked up his dad’s camera to help advocate for and share the amazing phenomena found in nature. From tropical marine biology to deep space observation, his work pairs photography with science to bring attention to pressing issues and amazing wonders. Currently he assists at WonderLab, a science communication studio in Berkeley.

p. 25 Bonnie Lewkowicz is passionate about outdoor adventure and ensuring others with disabilities can enjoy it too. For over 40 years, she has advocated for greater access to nature. She authored A Wheelchair Rider’s Guide to Bay and Coastal Trails and created a website featuring accessibility details for more than 125 California parks and trails. Now the manager of Access CA at BORP Adaptive Sports & Recreation, Bonnie continues to research trails, consult on accessibility, and champion disability inclusion in outdoor spaces.

Other Contributors: Jane Kim (p. 10), Guananí Gómez-Van Cortright (pp. 12, 42), Clayton Anderson (p. 14), Endria Richardson (p. 15) Jillian Magtoto (p. 29), John Muir Laws (p. 46).

p. 30 Ken-ichi Ueda is an angry old man from Oakland who likes looking at plants. Hairy flies and offensive glandular aromas are important parts of his love language. He is also one of the cofounders of iNaturalist.

p. 30 Laura Cunningham grew up in the East Bay, which helped shape a keen interest in the natural world. She has a passion for natural history, historical ecology, paleontology, and art and was able to combine these subjects by authoring the book A State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California (Heyday: 2010). Currently she works in the field of conservation biology and is undertaking several paleoart paintings for a museum.

p. 26 Anton Sorokin is a wildlife biologist, writer, and photographer who has been based in California for six years. Previously he worked with endangered parakeets, poison frogs, and, of course, snakes. Here in California, Anton continues to work with reptiles and amphibians—and spends his free time with them, too. His writing and photography have appeared in Bay Nature, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, and more.

masthead, vol 25, no 3

summer 2025

e xecutive Director/Publisher

Wes Radez

eD itor in c hief

Victoria Schlesinger

senior e D itor

Kate Golden

Art Director

Susan Scandrett

events coor D in Ator

Lia Keener

journ A lism fellows

Tanvi Dutta Gupta, Jillian Magtoto

co P y e D itor

Cynthia Rubin

A D vertising Director

Micaelyn Compton

P roofre AD er

Dominik Sklarzyk

membershi P m A n A ger

Patrick Brod

D evelo P ment m A n A ger

Barbara Butkus

fin A nce D irector

Jenny Stampp

i nform Ation technology mA n A ger

Laurence Tietz

cofoun D ers

David Loeb, Malcolm Margolin

b o A r D of Directors

Fatima Abdul-Khabir, Deonna Anderson, Tim Falls, Nan Ho, Rebecca Johnson (chair), Matt McKerley, Suzanne Moss, Dana Swisher, Anh Phuong Tran

v olunteers

Kim Dunn, Robert Jankowski, Julie Keener, Sheila Moore, Kimberley Pierce, David Wichner

Bay Nature is published quarterly by the Bay Nature Institute 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710

Membership: $40 annually (888)422-9628, BayNature.org PO Box 6409, Albany CA 94706

Advertising:

Ueda photo: Tony Iwane

Cover: The San Francisco skyline—including the Transamerica Pyramid, Ferry Building, and Salesforce Tower—rises behind openwater swimmers in the Bay.

By Sylvia Lacock, Pacific Open Water Swim Co.

Advertising@baynature.org

Editorial & Business Office: 1328 6th Street #2, Berkeley, CA 94710 (510)528-8550; (510)528-8117 (fax) BayNature@baynature.org

Printed by Commerce Printing (Sacramento, CA) using soy-based inks and alternative energy. ISSN 1531-5193

No part of this magazine may be reproduced without written permission from Bay Nature and its contributors. © 2025 Bay Nature

New stories waft gently onto BayNature.org each week. Find nature news, great reads, events, and places to explore in our weekly newsletter: TinyURL.com/BayNatureNews

» Ocean Beach’s Dunescaping

Sea-level rise is threatening San Francisco’s shores. Vegetating the remaining sand dunes is part of the city’s answer.

Cat vs. Bird

I am a bird-person. I was assigned this label because I advocate for birds. You may be a bird-person too, or perhaps you are a dog-person, cat-person, or butterfly-person. In the spring of 2025, when I read the Bay Nature piece “A Community and Its Cats” by Endria Richardson, I admit I initially had an unfriendly response. As the director of conservation for Golden Gate Bird Alliance, I hear plenty of misinformed arguments for protecting the status quo, thereby imperiling our local birdlife. Upon a closer read, Richardson’s article was not that. Her article is an opportunity to engage Bay Area nature lovers in an important conversation that can one day reduce the billions of birds that are killed by cats in North America every year. Two things can be true at once: outdoor cats have devastating impacts on wildlife populations, and it is not their fault; they deserve life and care. Cat-people: keep your pet cats indoors or on-leash. Tap into your caring instincts to care for wildlife by refraining from feeding feral cats. Bird-people: support your local animal shelter by donating or volunteering to foster or adopt an indoor cat. Tell your neighbors about catios, or better yet, help them build one. Let’s build a community of cat-bird-people.

Whitney Grover, Golden Gate Bird Alliance

In the winter 2025 issue’s “How to Read the Wind Like a Sailor” article, a reference to “offshore winds” blowing into the Bay was corrected online to “winds from offshore,” as an offshore wind refers to wind blowing toward the shore.

Trump Turmoil Bay Nature is covering the new administration’s impacts on Bay Area nature. Send tips to editorial@baynature.org or contact an editor on Signal, the encrypted messaging app (Kate Golden: cormorant.50; Victoria Schlesinger: VicSch.99).

» Local Nature Service Jobs Vanish Ninety young people doing volunteer nature work for peanuts across the Bay Area lost their jobs when DOGE gutted AmeriCorps this spring. Now the oaks will go unplanted, and aspiring environmental scientists’ career prospects are murky.

In the wake of L.A. wildfires and Trump cuts, California’s $10 billion climate bond is increasingly important. BN has assembled a guide and data visualizations to help local organizations understand and prepare for the deluge of money.

Good news: Relocated silvery blue butterflies are surviving, one year after an experimental release in the Presidio. Volunteers this spring helped a new batch adjust to city life.

One O f

O ries —I was three, maybe—is of standing in the narrow space between the side of my house and the yard’s fence where a shrub grew high over my head. It was shady and cool back there, the hard ground damp. I felt hidden away in a wild world of my own, where dark pink flowers, large as my little hand and otherworldly, pulled my attention. Tentacles seemed to spill from the blooms’ mouths, and the plump petals felt like a strange, living fabric. The memory is so clear, most of all the quality of wonder and quiet fullness.

All these decades later, when I get outside on my own, disengage from all the deadlines and headlines, that feeling of wonderment reappears. And it has a name. Famed biologist E. O. Wilson called it “biophilia” and popularized it in a book by the same name, suggesting that “. . . to explore and affiliate with life is a deep and complicated process in mental development . . . our existence depends on this propensity, our spirit is woven from it, hope rises on its currents.”

Summer is a good time to nurture that spirit and the hope it brings, and we can do it just by being outdoors. This special issue of the magazine—the Explore issue—is a trove of ideas and information for doing so.

There’s an essay about journalist Susan Kuramoto Moffat’s conversion from deep skeptic to enthusiast of open-water swimming in the San Francisco Bay, along with a robust how-to list for newbies. Or, if you favor a slower kind of rush, learn where to look for local snakes, which often lurk nearer than we think. Not into reptiles? Discover the unsung blooms of summer— wildflower walks aren’t only a spring thing in the Bay Area. An article by iNaturalist cofounder Ken-ichi Ueda describes some of the hardiest species and a resource for finding them.

Longtime readers know that Bay Nature places in the Bay Area is deep. Twenty-five years deep. In a nod to our quar ter-century of publishing, we want to revive those stories. Check out our mini-guide to 25 trails and the past articles about them. This issue also cov ers accessible nature, herb foraging, trail running, jumping spiders, three regional trails, and more.

Step outside and find your biophilia.

Support from our partners helps us stay financially sustainable and allows us to continue to produce high-quality environmental journalism and connect our members with nature in unique ways. If you’re interested in partnering with Bay Nature, please get in

Lyngso Vegetable Blend, Nursery Mix, Potting Mix, Essential Soil Landscape Mix, Green Roof Mixes, Bioretention Soil Mixes, Diestel Structured Compost OMRI, Garden Compost OMRI, Biodynamic Compost CDFA, Organic Aged Humus CDFA, Premium Arbor Mulch, Fir Bark, Mocha Chip, Mahogany Mulch, Ground Redwood Bark, Actively Aerated Compost Tea, Mycorrhizal Fungi, Down to Earth Organic Fertilizers, Fish & Kelp Emulsion, Garden Books, Tools, Seeds

Gull juju

Who doesn’t love a souvenir from their adventures? Western gulls (Larus occidentalis) routinely fly the 30ish miles from the mainland to the Farallon Islands, bringing with them all kinds of “gull juju,” as Point Blue Conservation Science biologists call it. “Gulls simply find something that may or may not be edible and swallow it. They then regurgitate it later when they are back on the colony,” writes Farallon program leader Pete Warzybok. He explains by quoting the great naturalist William Leon Dawson: “The Western gull asks only two questions of any other living thing: First, ‘Am I hungry?’ (Ans., ‘Yes,’) Second, ‘Can I get away with it?’ (Ans., ‘I’ll try.’)”

The Farallones’ Western gulls have pulled one over on: “a variety of army men, Winnie-the-Poohs, Lego characters, rubber duckies,” along with a key, a button, marbles, a golf ball, a cigarette lighter, and a creepy baby doll leg, according to a Point Blue dispatch.

Point Blue researchers have studied the islands year-round and Western gulls during nesting season, from April through August, for nearly six decades, but that may change. They are currently grappling with federal funding cuts that were first announced in 2024. This calls for more than juju.

(Hemileuca eglanterina), ceanothus and coffeeberry rank high on the food love list. After eating their fill in spring, each caterpillar hunkers down in a silk cocoon. Starting in July, a spectacular pink-and-orange adult emerges, transformational journey complete. Look for these large moths during the day, flapping their wings continuously, erratically bobbing about.

on the Pacific seafloor an average of five million years ago—to reach the coastal bluffs between Point Reyes National Seashore and Santa Cruz clocks in at millions of years. These ancient clams, along with fossilized gastropods, barnacles, and whale and seal bones, peek from outcroppings at many beaches and whisper, “There is no destination— it’s all a journey, silly.”

ll aboard

Whatever your opinions about opossums

Didelphis virginiana)—yes, they carry diseases and may enjoy your fruit and vegetable garden before you do—a mother possum is a shoo-in for the “most adorable form of ground transportation” award. Once her babies finish nursing in her marsupial pouch and it gets crowded for the growing gang, the young will climb to their mother’s back, sometimes up to 13 of them! Clutching her fur, they will ride the mama possum train for several summer weeks, glimpsing highlights of the adulting ahead.

tH umbs out

Arguably an early adopter of hitchhiking, California oatgrass (Danthonia californica) may climb aboard your sock this summer. This native bunchgrass drops its seeds in July and August, and a skinny thumb growing from each seed covering will grab hold of passing furry legs or sweaty socks for a free ride. Called an awn, this thumb coils and uncoils when it gets wet and then dries, scrunching it ever so slightly toward a spot in which to germinate.

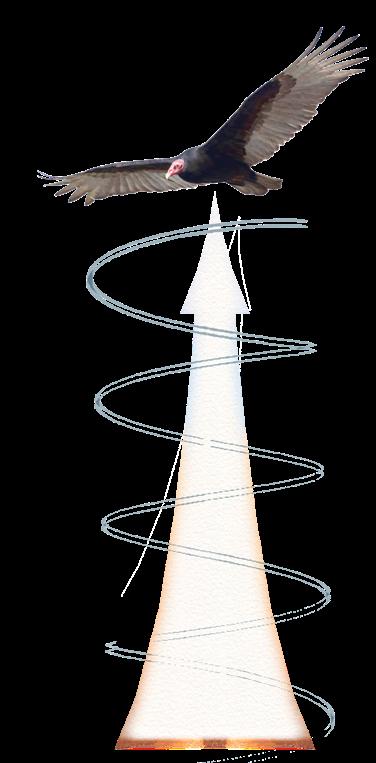

tH ermals

The sun beats down, the land warms up, and heat rises, creating columns of hot air that shoot skyward. These thermal columns are the e-bikes of flying for raptors, especially turkey vultures (Cathartes aura). Spreading their wings, raptors harness the column’s energy, soaring in circles while the rising air pushes them higher and higher, never beating a wing. From there, vultures scan for carcasses or wait to catch a whiff of one on the wind.

Jumping spiders hunt like cats and have the best vision of any invertebrates.

Behold the red-backed jumping spider (Phidippus johnsoni), among the most commonly spotted out of at least 50 jumping-spider species found in the Bay Area—and one of the biggest, being roughly thumbnail-size. These miniature predators can live in habitats from beaches to mountains; find them in open areas or perched on fences on warm, sunny days. In summer, females are guarding eggs: a new generation is arriving.

Text by Guananí Gómez–Van Cortright | Photos by Jacob Saffarian

Fuzzy

Different hairs have different receptors, allowing these spiders to taste and smell their surroundings, pick up on vibrations, and detect subtle air movements.

Males’ bright colors have often been sexually selected for by the ladies; this is a female.

Leap of faith

Jumpers don’t spin webs to capture prey. Instead, they use their remarkable vision and powerful legs to pounce, ambushing crickets, flies, dragonflies, and even small frogs. The spiders use their third or fourth pairs of legs to leap 10 to 20 times their body length. (Imagine a six-foot human hopping up onto an eight-story building.) If a spider misses its target, no problem—it’ll catch itself on a silk line and climb back up to try again.

Bite-size

At the tips of their muscular jaws, or chelicerae, are venomous fangs. Using the element of surprise, a jumper leaps onto its prey, flips it (if it’s large or feisty), pins it, and injects paralyzing venom. Jumping-spider venom is not dangerous to humans.

I see you!

You can tell jumping spiders apart from their arachnid kin by their signature big, googly eyes. Unlike most invertebrates, they can focus at high resolution and see about as far as cats can. Two smaller eyes at the sides of their heads scan for peripheral motion. A third pair offers motion detection and distance vision, while a fourth is mostly vestigial.

A female jumping spider, like this redback, spins a silky sac for her 50 to 100 eggs and attaches it to her retreat. Then she guards it while the eggs develop. Look closely for the tiny, leggy bodies visible in some of these eggs.

Mani-pedi

Jumping spiders use fuzzy appendages called pedipalps to detect each other’s silk, store sperm, smell and taste things, and maneuver their food into their mouths. If a pedipalp is damaged, a jumper can regrow it, but the new limb might be shorter or more translucent or have less hair, as seems to have happened with this individual’s left pedipalp. Male spiders have boxing-glove-shaped bulbs at the ends of their pedipalps.

After hatching, often in summer, tiny baby jumping spiders molt eight to 10 times over the next nine months before becoming adults. Spiderlings feed off egg yolk before they leave the nest and learn to hunt for themselves. Jumping spiders usually live for about a year, and males often die younger than females.

Song and dance

Courtship is an elaborate affair. Males prance and show off their fuzzy colors to attract females’ attention, waving their front legs in complex patterns. They drum their other legs and vibrate internal organs to craft a sultry percussive tune. Researchers are investigating how jumpers manage such complex behavior, given that their brains are about the size of a poppy seed. Male jumping spiders get eaten for their trouble about half the time, though less often among the red-backs.

Like Spider-Man, jumping spiders explore the world in all three dimensions, swinging from silk lines to make hasty escapes or sneak up on prey. When exploring, they exude silk from their spinnerets, the silkproducing organs on their butts, to use as safety lines. At night, they rest in spun hammock-like hideaways called retreats, suspended in the crooks of plant stems.

Look out. Summer is here! Exciting, heading outdoors, beautiful sun, warm weather, special places to go! ¶ For a hairy woodpecker (Dryobates villosus), summer is actually a slight reprieve after a very busy spring when a well-positioned tree had to be decided upon, then the “right” spot on that tree had to be “debated,” then the excavation had to be completed . . . phew, I’m tired just thinking about it.

The effort to dig a hole in wood is high by any standard, but woodpeckers do it with their mouth! They have a special shock-absorbing system built between the bill and the skull that allows the birds to deliver repeated blows with their head that would send the average organism into concussion protocol.

Hairy woodpeckers are tough and very adaptable birds found all across the North American continent, and parts of Central America, in deciduous to coniferous forests, living from sea level to almost 11,500 feet in elevation. But wherever hairy woodpeckers occur, they tend to spread out. I’ve never seen more than four of them in close proximity to one another. Hairy woodpeckers don’t generally get the attention from birders that they deserve, as they are in direct competition with their more charming, adaptable, and diminutive cousin, the downy woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens).

All that spring work that affects the outer world—selecting a nest site and developing it—sets the stage for the potential of a very beautiful inner world: the egg laying, the little ones showing themselves, identifying the best hunting grounds, and the pair bond strengthening through life’s most extreme dramas.

Summer’s slight reprieve, it’s still an exciting, eventful, and easily exhausting time. The need to protect the little ones is as great as it will ever be. Flying from hunting ground to nest and back again, possibly up to 60 to 70 times in a day (not including securing the food item), can challenge any feathered heart rate. That sparkling sun and warm weather enable opportunities to hunt longer, go farther, explore more. After about 60 days of creating and developing this inner world, the result can be three or four more young, beautiful hairy woodpeckers.

But this consummate story of creation doesn’t necessarily stop here. An amazing fact about most woodpeckers: They don’t reuse their nest hole the following year. And if the site of the hairy woodpecker’s beautiful inner happening (usually in mature or decaying trees) is undisturbed, it’s much more likely for it to be occupied again the following year, but by a completely different type of bird.

There are a whole host of birds that fall into the category of what we call “cavity-nesters.” These are birds that prefer to build their nest inside of something. It could be anything, from behind a peeling piece of tree bark to an old work boot left on a shelf on a backyard porch.

The following spring at the hairy woodpecker’s old nest hole, a pair of blue and rust-colored, feather-covered balls, weighing about an ounce each, could reuse the cavity to create more inner and outer beauty. The western bluebirds (Sialia Mexicana) are kind of a success story. This bird’s close cousin the eastern bluebird was disappearing in the 1900s mainly because we were mismanaging the dead snags these birds prefer to use for their cavity nests. Once we did the research and started building nest boxes as a substitute, the birds found them suitable and their numbers improved.

The next spring, after the bluebird’s spring, a pair of halfounce, french gray, pointy-headed birds could show up and reuse the cavity. What the oak titmouse (Baeolophus inornatus)

lacks in color it makes up for in personality. These innocuous little birds are very vocal, belting out a variety of songs and calls magnitudes louder than what you would think their little round bodies can handle. They are feisty, adaptable, and pair for life. And the vast majority of the entire oak titmouse population lives only in California.

And so on, the following spring, after spring, after spring.

It’s obvious to me that all woodpeckers are unsung national treasures. The amazing wood-drilling talent of one hairy woodpecker echoes beauty for years into our outer futures, so much so that we all should be touching the placard of our local wooded green spaces in gratitude each time we find ourselves walking by.

This deep effort of creating such a lasting infrastructure for inner growth and beauty results in an outflow of beautiful manifestations: beautiful in, beautiful out. ◆

Clayton Anderson

by

Irecently ran a 31-mile trail race around Lake Chabot. It was the longest distance I’d ever run by about 10 miles. I ran past redwood stands, poi son oak, fern. Occasionally—alerted by a sound of life off-trail, a bird call above—I looked up or around. In a clearing to the side of the trail: parked green excavators, piles of felled and stacked logs, rutted tracks of heavy machinery, signs of the work of trail-building.

The East Bay Regional Park District manages over 100,000 acres of land. More than a thousand miles of trail. You can follow any path or network of paths for hours and hours, from woodland to grassland to creek habitat, without seeing more than the swath of cut land in front of you, the gently graded road. I memorize routes not by landscape or terrain, but by a sequence of turns. Decades of work, acres of world, condensed into a list of names: Grass Valley to Brandon Trail to Towhee to West Shore.

I have been thinking, these past months as I’ve been training—running loops and loops through Oakland parks—about knowing a place through its quickest paths. A trail is a way to move fast. Rocks and roots, the open mud and slick grass of recent rain, a bright ridgeline with its long view—mist on the lake, Mount Diablo to the east—are obstacles to overcome. The climb hurts. The ridge too hot. This is where I caught my foot beneath a root, nearly flew into a ditch. This is a paradox of trail running, and especially trail racing: I want to move quickly enough to miss the rock, the root, the mountain, for the trail.

There is pleasure in this kind of forward movement: unimpeded, constant progress. I follow the work that has been done. The trail moves, and I move with it.

But there are other trails than these. Near the end of a long training run, 18 miles of rolling hills from Bort Meadow to the Lake Chabot Marina and back, my right hip aching and my right hamstring aching, I ran into a friend. They mentioned that another hiker had seen a mountain lion, crossing near the power lines a few minutes up the trail. By the time I passed the spot, the lion—if it had ever been there—was long gone.

Trail-building is world-building. Cleared of brush, empty of cover, the trail marks a boundary between worlds. When animals see me on a trail, I see them leave. Brush rabbits dive back into long grass. A coyote slips between bent oaks. A bevy of quail erupts to the sky. If I’m quiet, I can hear the sounds of another place—the one just off the trail—as I go by: someone picking their way, carefully, through another realm.

But I move too quickly to know it well. A few years ago, on an early summer backpacking trip in Shasta-Trinity National Forest, the trail my wife and I were following disappeared beneath five feet of snow. Stepping through snow, without trail markers or even blazes to guide our way, we took 90 minutes to cover half a mile. Returning to a trail felt like stepping onto a conveyor belt. We moved with such strange assurance.

A mile through uncleared land is a long way. Thirty-one miles on a trail can pass so quickly. It is hard, when going fast, to notice what is not visible—the world displaced so that we can move with ease. Just the sounds of human voices, the softer noises of hiking, may be enough to cause deer and sheep, wolves and bears all to turn in their tracks, remain hidden until dark.

A few days after my improbable-but-possible near-encounter with a mountain lion, I ran along one of my favorite loops on an early weekday morning, few cars in the parking lot, mist above the hills. I did not look only at the trail in front of me. I looked up and around, scanning for tawny paws dangling from a mossy branch, that long, black-tipped tail switching beyond a curve. But the path was always clear.

I will likely never see a cougar in this world. To move so freely is to be a powerful beast. Look how everything avoids my path. Look how they run. ◆

Hire a local birding guide in the Bay Area with Golden Gate Bird Alliance!

Start planning your solo trip or private group outing today.

Scan the QR code below or visit: https://goldengatebirdalliance.org/ privatebirding

What we put on the land flows to the water. Pesticides and herbicides don’t just stay in the soil - they seep into streams, threatening not only monarch butterflies, and native pollinators, but also juvenile fish that rely on healthy watersheds. Small choices in your backyard can ripple to improve the Bay.

“Craig’s 4-Steps” grasslands through systematic mowing

Get rid of weeds and bring back your wildflowers with craig@ecoseeds.com ecoseeds.com/four-steps.pdf “The Wildflower Whisperer”

Visit Kite Hill Wildflower Preserve in Woodside to see these amazing results!

Let’s work together for a cleaner and more resilient ecosystemfrom our home gardens to the ocean!

Welcome to Bay Nature ’s mini-guide to 25 Bay Area trails in some of our favorite plac es, ranging from peaks and valleys to redwoods and tidal marshes, described in 25 pre viously published stories. Choose a trail and then visit the guide online, where each trail is kitted out with an interactive trail map and an in-depth story from our archive.

Over time, I discovered that no one comes out of the cold water in a bad mood.

by Su S an Kuramoto m offat

There is nothing like swallowing a mouthful of San Francisco Bay to make you care about local water quality. The first time I swam in the cold, murky water, a little wave tossed a jigger of the Bay’s salty soup down my throat. I was suddenly curious about all the microbes making their way to my stomach. And as I swam, the silky feeling of the water on my skin, the slimy blade of eelgrass clinging to my wrist, and the quickening of my breath all raised a thousand questions about the ways I was related to the invisible life floating all around me. I became acutely aware of being a land mammal in a realm that was not mine. I sensed the thinness of the membranes separating the wild world outside my body from the biome within.

Now I immerse myself almost daily in this water. It is a gentle, health-giving, and powerful connection not just to underwater worlds, but to the watersheds from Oregon down to Bakersfield that stream into the Bay. I swim in Sierra snowmelt and Pacific waves that start as far away as Japan. Swimming helps me see myself as an organism subject to landscape-scale forces: the Bay

receives waters from rivers that drain 40 percent of California’s area. Plunging into the Bay submerges me in the world of tiny beings at the bottom of the food chain. In that mouthful of Bay water was a kaleidoscope of life—free-floating larval barnacles, eelgrass pollen, and seaweed spores. A map or a microscope can help us analyze our connections to these landscapes and creatures, but they can’t match the sensory intensity of a full-body encounter with the water.

I started swimming in the Bay at a time when I was feeling disconnected from the world. It was half a year into the pandemic, and I was taking regular socially distanced walks at the Albany Bulb, a landfill that stuck out a mile into the water not far from my home on the Bay’s eastern shore. From the trail, I would see a handful of women stripping down to their bathing suits at the small beach. They’d walk past the romping dogs and glide into the water—most of them sans wetsuits. I thought they were crazy.

Then one October evening, I watched the documentary My Octopus Teacher, about a man in midlife crisis who swam in the

frigid ocean near Cape Town, South Africa, so he could get to know an octopus. The next morning, I took a towel down to the beach.

The women were chatting, all bare legs and baggy coats, pulling on swim caps. They were friendly to a newcomer, introducing themselves and asking my name as if we were at a church coffee hour. I asked for tips but mostly they offered simple encouragement. I took a deep breath and waded into San Francisco Bay.

It was shockingly cold. Feet, thighs, belly: frigid. My brain knew to expect this, but my body was flabbergasted. I took a deep breath, plunged in, and started swimming furiously in a vain attempt to get warm. First, the surface of my skin was cold. Then the cold moved inside. My collarbone felt like it was made of steel, attracting and conducting the cold. After a bit, though, the pain in my clavicle abated and the surface of my skin forgot it was cold. A hundred strokes later, a strange warmth radiated through my body and I swam on in surprising comfort. But eventually the surface of my skin began to burn and prickle. My pinkie fingers stuck out stiffly and I was unable to pull them back in. I thought it best to turn around and I swam back to the beach, pulling with clawlike hands.

Back onshore, I felt only exhilaration. I got dressed among the

other women, all of whom bore the same teeth-chattering, beatific smile I had. Over time, I discovered that no one comes out of the cold water in a bad mood. By the time my frozen hands could pull my shirt and pants on, I was shaking. Not little shivers, but convulsions so violent that I spilled some of the tea in my thermos cup onto the ground.

I later learned this is “afterdrop.” When you swim in cold water, the blood rushes from your extremities into your torso to warm your essential organs. When you get out, the blood starts redistributing itself back to your legs, feet, arms, and hands; your viscera get cold and your body responds with tremors that try to warm everything back up again. This violent ebb and flow is somehow salutary. It feels so good, both mentally and physically, that you begin to crave it. As I began to swim regularly and my body acclimated to the water, I needed longer swims to get the same effect. But it was an addiction that I couldn’t resist.

In the long months during the isolation of COVID, a growing group of swimmers found each other at this spot. The cold

Left: Swimmers begin a swim from the Golden Gate Bridge to the Bay Bridge as the day’s marine layer, aka fog, lifts. Below: At Crissy Field Beach in San Francisco, yearround swimmers take their weekend plunge into the Bay’s chilly water.

water and the warm companionship helped us survive. We felt fully alive, and not alone. Some had been regular indoor swimmers and were desperate when health authorities closed the pools. Others, like me (who could barely swim and detested chlorine), were drawn to the Bay itself. The little daily 8 a.m. group snowballed as curious passersby asked if they could join. Most of us had been strangers to each other, but we built an intimacy that could only happen outdoors in those days and that has since outlasted the pandemic. Every day, we shed our cares with our clothing, share food and humor and heartache. Our common religion is a sense of awe at the spectacular watery wilderness we dip into each morning. Looking across 10 miles of water at the morning light hitting the Golden Gate Bridge and stroking our way toward it—even for a few hundred yards—is a daily practice of hope.

The Bay gives us Big Nature, an altered and invaded yet uncontrollable wildness literally a short walk from the sidewalks and front porches of our tidy human neighborhoods. And that

Open-water swimming has become increasingly popular since the pandemic, when pools were closed and many swimmers headed to the Bay. I’ve compiled great places to swim in the Bay, from beaches to docks, and general information for getting started.

Clockwise from top: Alcatraz rises behind a solo swimmer. Five friends ready to swim from Alcatraz to San Francisco. Swimmers under the Bay Bridge complete a 6.2mile swim.

The Bay is a wonderful place to swim, but it can be dangerous. It’s safest to swim with others. Even if you’re a strong pool swimmer, currents can be challenging and you need to be aware of hazards such as boats, kiteboarders, fishing lines near piers, and underwater debris. To stay safe in currents, which vary and can reverse hour by hour, it’s best to swim with a local swimmer who has experience at a particular site.

The Bay is cold—ranging from the low 50s to the low 60s in most swimmable locations, depending on the season. Be aware that hypothermia can cloud your judgment about just how cold your body is. Stepping into a hot shower when your body is cold can make you dizzy, so beware of falls.

Water quality declines after storms, because rain drains directly from streets into the Bay, so it’s recommended to wait 72 hours after a major rain and to check water-quality reports.

Two open-water swimming clubs at San Francisco’s Aquatic Park welcome nonmember visitors to their shower and sauna facilities on designated days. They also sponsor organized swims from Alcatraz and other locations.

Find all of this information online at BayNature.org/ swimming or scan the QR code.

Lessons for all levels, coaching, and longdistance and destination swims, including to Alcatraz and the Golden Gate Bridge, are offered by private companies, with many swims supported by kayaks and motorized boats. Local triathlon groups also often organize open-water training swims.

• OdysseyOpenWater.com

• PacificSwim.co

• SanFranciscoSwim.com

• SharkFestSwim.com (event swims only)

• Dolphin Club: Public access for a fee, Mon, Wed, Fri; DolphinClub.org/swimming

• South End Rowing Club: Public access for a fee, Tue, Thu, Sat; SERC.com/swimming

wildness echoes the jungle within my body, where the number of bacterial cells outnumber human cells 10 to one. How is it that the minuscule, jewellike diatoms and other photosynthetic organisms floating all around me generate something like half the oxygen in the air that I gulp hungrily with each stroke? How can the invisible animal plankton wriggling through my hair support a food chain that stretches up to salmon and egrets and whales—and us? How can my body imbibe the bacteria and viruses floating in that mouthful of water and know either how to kill them off, to send them back into the water (yes, I pee there), or to add them to the pound or two of resident “good” microbes in my body that help me stay alive? In the water, the way that the slosh of carbon and oxygen flows in and out and through me becomes obvious. Nature is not some pristine thing defined by the absence of humans. It is, rather, a world in which I am both implicated and immersed.

One morning, I thought I accidentally kicked a floating log with my foot. Then, again and again, something was bumping my foot—following me? And then it stopped. A bit unnerved, I looked around. Just a few feet away, I met the shining black eyes of a seal,

There are many informal groups who gather to swim in the Bay. Swimmers tend to be a friendly bunch, so if you see folks at a beach or dock, introduce yourself.

• East Bay Open Water Swimmers: A loose-knit group who swim around the Bay but most often at Keller Beach in Richmond and at the Berkeley Marina. Join their listserv to get notices of when and where people are swimming. EBOWS.org

• Marin Open Water Swim Adventures: An informal group with Saturday swims at Paradise Beach in Tiburon. MarinOpenWaterSwim.org/new-swimmer-info

• The Selkies: A queer and trans open-water swim community using the messaging app Signal to organize swims throughout the Bay Area, mostly from Alameda north to Richmond. They also have a group for South End Rowing Club swimmers and additional community-building events like full-moon night swims and a swim-themed book club. To join the Signal group, join the East Bay Open Water Swimmers listserv at EBOWS.org, post a message with “Selkies” in the subject line, and someone will get back to you.

floating, like me, with just its head out of the water. It wasn’t afraid of me; nor did it threaten me. This was new: on land, a deer or a rabbit will run away, and I want to flee if I see a mountain lion or a bear. But here in the water the seal and I were meeting as mutually curious equals, neither predator nor prey. When I swam on, though, the seal passed under me and brushed its whiskers against my knee, sending my adrenaline rushing. We were not equals after all; the speed and agility of this sea mammal, friendly as it was, let me know that I was in its home territory, not mine.

I’m made small by submerging myself in the Bay, and enlarged. Almost naked in the water, I am vulnerable; my body senses acutely that every millimeter of its surface is in contact with the world. My semi-blindness in the water helps me see more clearly both my inadequacy and my ability to adapt. When I swim, each breath is a miracle, reminding me that I’m not drowning, even though I haven’t evolved to live here. I feel my own weakness and resilience and the power and fragility of all the beings around me. Here, I have found community with other people and with the rest of nature. We find strength in our interdependence as humans and joy in being part of the life all around us. ◆

Inflatable swim buoys that attach to your waist with a strap make you more visible and safer. A brightly colored swim cap is also a good idea. Silicone ear plugs (the soft kind that look like clear cough drops, available at drugstores) help keep you warmer by preventing cold water from entering your ear canal.

Is a wetsuit necessary? It’s up to you. Some people swim year-round with no wetsuit, others always wear one in the water. Neoprene caps can help keep you warm even if you don’t wear a wetsuit, and booties and gloves are an option. Triathlon-style wetsuits are more comfortable for swimming than surfing versions, which are much stiffer. Sports Basement will rent you a wetsuit and let you buy it if you choose.

Accessibility information for people with mobility limitations can be found at SFBayWaterTrail.org/plan-your-trip/ accessibility

1Aquatic Park, San Francisco

Home to two swimming and rowing clubs, the cove has a public beach and is somewhat protected from waves. Stay inside the cove, where the currents are less hazardous, unless you’re on an organized swim or with an experienced buddy. Restrooms are open at the San Francisco Maritime Visitor Center and the Maritime Museum during their operating hours only.

2 Crissy Field East Beach, San Francisco

Swim close to shore. Restrooms, showers, and plentiful parking.

3 Clipper Cove, Yerba Buena Island

Generally calm waters accessed down a flight of steep steps to a small beach. You may need to park at the Treasure Island Yacht Club, just past the beach. No restrooms.

4 Quarry Beach, Angel Island

Ferry to Angel Island and hike or bike to the beach below Fort McDowell. Strong currents. Toilets on bluff above beach.

5 Paradise Cove, Tiburon

Enter water by ramp near foot of pier; avoid swimming near people who are fishing. Flush toilets and picnic areas.

6 China Camp State Park, San Rafael Swimming from China Camp beach to Rat Rock is popular at high tide. Flush toilets and picnic areas.

7 Keller Beach, Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline, Richmond

Very popular spot for swimmers. Pay attention to tides and currents. Showers, flush toilets, picnic area. Park on street.

8 Albany Beach, McLaughlin Eastshore State Park, Albany

Small beach very popular with off-leash dogs and kiteboarders. Vault toilet. Limited parking.

9 Berkeley Marina South Basin

Jump off dock near the Cal Sailing Club or enter water next to Hs Lordships restaurant, which is closed; watch out for windsurfers and dinghies. Flush toilets.

10 Point Emery, Emeryville

Small beach, no bathrooms or showers.

Small parking lot.

11 Robert W. Crown Memorial State Beach, Alameda

Often warmer than other spots in the Bay and friendly to beginners because you can swim in the shallows along the long beach. Showers and flush toilets available.

12 Encinal Boat Ramp, Alameda Jump off dock at high tide; walk into the water between the docks at low tide. Hot showers and bathrooms available next to parking lot.

13 Jack London Aquatic Center, Oakland Jump off dock to swim. Good low-tide spot, also popular with high school crew teams and Oakland’s dragon boat team. Portable restrooms.

14 Coyote Point, San Mateo County Beach entry, bathrooms, and showers. Best in the morning before wind picks up. Vehicle admission charged at card-payment machines. Water quality varies. Check San Mateo County water-quality tests, updated on Wednesdays.

Note: The far southern end of the Bay in Santa Clara and southern Alameda Counties is too shallow for swimming.

(Note: Not all swim spots listed are monitored for water quality.)

• Alameda and Contra Costa County, East Bay Regional Park District: EBParks.org/ natural-resources/water-quality

• Marin County: MarinCounty.gov/ departments/cda/env-health-svcs/ prgm-beach-water-monitoring

• San Francisco County: WebApps.SFPUC. org/sapps/beachesandbay.html

• San Mateo County: SMCHealth.org/ beaches

• Videos about currents, hypothermia, and more from SERC.com/swimming-aquaticpark

• Open-water swimming tips from Dolphin Club.org/swimming

• Tips on swimming and links to tide charts from EBOWS.org

• Great writing about open-water swimming around the world can be found at Outdoor SwimmingSociety.com

Cutting-edge advances in adaptive equipment (aka assistive technology) are transforming the outdoor experience for some people with mobility disabilities. All-terrain wheelchairs, motorized track chairs, and adaptive bikes—many developed by disabled innovators—are opening up rugged trails and remote landscapes that were once considered inaccessible.

Everyone deserves immersive and varied experiences, and as the director of Access California, a program of the Berkeley-based nonprofit BORP Adaptive Sports and Recreation, I’ve worked for more than four decades to make the outdoors more available to people with mobility challenges. But most accessible trails still stop short of less developed areas, limiting the experiences many people with disabilities desire.

Adaptive equipment could help change that, but the prohibitive price puts it out of reach for many who would benefit most. That’s where public land agencies come in. By providing equipment on-site, parks can open the door to a wider range of experiences. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, many of these devices are classified as an OPDMD (other power- d riven mobility devices) and are legally allowed in pedestrian areas, with some exceptions. By embracing assistive technology, parks can expand the definition of accessibility.

equipment as a cost-effective strategy— Marin now has a blueprint for action.

In 2024, Richard Skaff, executive director of the nonprofit Designing Accessible Communities, hosted demonstration events at Rodeo Beach and Tennessee Valley, showcasing the Terrain Hopper, a four-wheel-drive electric off-road mobility vehicle. Land agency staff watched as participants confidently navigated the rugged trails with huge smiles on their faces. People were impressed by the Terrain Hopper’s safety, versatility, and the joy it enabled.

high demand on summer weekends. Beach wheelchairs for use at other locations can also be borrowed with advance reservation, though they are bulky and require a large vehicle for transport.

At BORP Adaptive Sports and Recreation, we are partnering with youth educators at Santa Barbara’s NatureTrack to offer “Day on the Beach” events that feature the Freedom Trax, a small, motorized platform with wheelchair seating. Tractor treads allow users to traverse sand, grass, and some rugged trails independently. While their high center of gravity can be limiting, Freedom Trax units are more portable and affordable than many OPDMDs.

This summer, Marin County Parks will launch its OPDMD program in partnership with other regional land agencies. It will begin with two vehicles supporting monthly guided outings on public lands in Marin County—marking a major step toward inclusive access to the region’s landscapes.

In mid-June, people will test-drive a Freedom Trax as part of “All Abilities Day” hosted by the Doug Siden Visitor Center at Crab Cove at Crown Memorial State Beach in Alameda. A beach wheelchair is available yearround at the visitor center but adding a Freedom Trax to the fleet is on the wish list. For many who’ve tried these devices, the impact is profound. After using the Terrain Hopper, one wheelchair user said, “People say they want to go to heaven, but I found it here at the beach.” This equipment won’t work for everyone—but it should be part of a broader solution. It must complement, not replace, ongoing efforts to improve physical accessibility and, most important, challenge land agencies to think more imaginatively about inclusion. The moment calls for bold thinking—and these tools offer a powerful way forward. ◆ —Bonnie

Lewkowicz

EXPLORE ADAPTIVE EQUIPMENT

The Bay Area has long led on disability rights, and parks across the country have taken the lead in offering adaptive equipment. In 2016, Marin County Parks began stepping up. After completing its Inclusive Access Plan which highlighted adapt ive

Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) has long offered beach wheelchairs at sites like Stinson Beach, Muir Beach, Rodeo Beach, and East Beach at Crissy Field. These balloon-tired PVC chairs don’t go into the water but allow users to reach the sand. Although they require assistance and some strength to maneuver, they remain in

For more information about adaptive equipment and accessible trail resources, please see the story online: BayNature. org/accessible

On any Bay Area hike, snakes are likely closer than you realize. They lurk in gopher tunnels, hide under rocks, or bask in thickets just off the trail. Yet you probably won’t spot them—their survival depends on remaining hidden. So for nature lovers seeking a challenge, finding a rare snake is deeply rewarding. “Snake hunting,” says Emily Taylor, a Cal Poly San Luis Obispo biology professor and snake expert, “is the new birdwatching.”

The Bay Area is home to 25 different kinds of snakes. To maximize your chances of a face-to-face encounter, familiarize yourself with your target’s habits and preferences, just like birders do. Finding all our snake species may take years of effort. As a wildlife biologist and obsessive snake seeker, I’m still on the hunt myself. Here are some tips on getting started.

In this area, one hike may meander through redwoods, scrubby chaparral, oak woodlands, and shaded riparian canyons. It’s a mosaic of habitats with an array of inhabitants.

Years ago, when I started looking for snakes, I would open a field guide and flip to the range maps, glance at the shaded region for a species, and rush out, imagining that anywhere in that area could yield my target. I failed to consider microhabitat requirements. Microhabitats are the differing features across the wider landscape—rocky ridges, meadows, creeks. Each species has its

preferred haunt. With no other snake is this as apparent as with the Bay Area’s flagship species, the San Francisco gartersnake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia).

Its range map includes nearly all of San Mateo County and a portion of Santa Cruz County, but you’ll never find it in the redwoods or chaparral. You have to think like a San Francisco gartersnake to find it. What do gartersnakes love? Frogs! What do frogs love? Ponds! The San Francisco gartersnake is rarely found far from water and its frog buffets.

The gartersnake’s alternating stripes of red, blue, and black, which stream down its back and flanks, have earned it an international fan club. “They’re kind of a legendary snake,” says Toby Sheppard-Wilder, a fifth grader and snake aficionado from Oregon whose family made a trip this spring to see these snakes. On a sunny morning in San Mateo County, Toby saw his first one, after just 15 minutes of searching. “I was really happy afterwards, for a long time,” he says. “Still am!!”

Toby’s winning strategy to find them (and mine as well) is to prowl slowly around pond margins, scanning vegetation at the edge for basking snakes. Go slow; despite their bright colors, they blend in well. When you see one, stay quiet and watch—not only to avoid disturbing an endangered species but because an unobtrusive approach has its own rewards. I once watched a gartersnake cruise along the edge of a pond poking its head into the

crevices between matted tule. It caught nine treefrogs, choking each one down like popcorn in a matter of seconds.

The California mountain kingsnake (Lampropeltis zonata) is another looker on the Peninsula, with rings of maroon, cream, and black down its length. But it is no show-off—the kingsnake can be one of the most challenging of all local snakes to find, as it spends most of its time underground. It’s the Goldilocks of snakes, waiting for the perfect blend of conditions to come up and bask at the surface: recent rains and cool nights followed by balmy daytime temperatures. On warmer days, look in the morning. On colder overcast days, a ray of sunlight warming the rocks might bring mountain kings out from their underground halls. These kingsnakes can live for over 20 years, so if you see one, you may well cross paths again!

Red, white, and black-banded snakes are often said to have evolved their flashy colors to mimic venomous coral snakes. On its face, that doesn’t add up for our mountain kings, whose range does not overlap with that of coral snakes. How would predators learn to associate the color pattern with danger and avoid it? Researchers have championed various ideas. Perhaps the species’ ancestors’ ranges overlapped in the past. Maybe predators avoid those colors instinctually. Or maybe the colors give slithering snakes a ‘‘flicker effect,” making them harder to visually track.

What do the rolling hills of Marin County have in common with the Amazon jungle? Boas! But while the Amazon’s enormous anacondas can swallow a capybara whole, here we have rubber boas (Charina bottae) that can swallow a baby mouse whole. Our boas can do something the giant constrictors of South America could never manage, though—survive in the cold. Ours are the northernmost species of boa, and while they don’t mind cool weather they do seem to require some moisture. They are rare or absent in dry areas like the Diablo Range. In the North Bay, they flourish.

On a blustery day in the Marin Headlands, as the fog burns away, the vegetation twinkles with dew, and the sun breaks through in patches—that’s when you might find a boa thermoregulating, maybe underneath a fallen fence post or a wind-whipped piece of cardboard nestled on a grassy hillside, as I once saw. That’s a perfect little safe house to warm up under without exposing oneself to predators like hawks or coyotes. If you find a boa, pause to appreciate how its skin looks several sizes too big and crinkles oddly along the curves. How its olive scales are unusually small and smooth to ease its movement through the soil. Then look at the head. Or is that the tail? Don’t worry, you wouldn’t be the first to confuse the two; in fact, this is the boa’s best defense. Facing a predator, or even an angry mouse whose home has been invaded (boas eat baby mice), the snake presents its tail for a bruising while hiding its head. That’s why older boas almost always sport scarred, knobbly tails.

Admire the boa, and then carefully put back its cover. Boas are slow-moving and slow-growing, and they return to the same favored spots to thermoregulate, so this could be the start of a beautiful friendship. A boa from Oregon was determined to be

at least 55 years old—the longest recorded lifespan of any wild snake. Some of the boas in Marin’s hills could remember the moon landing or the dissolution of the Beatles, if boas cared about the things we legged creatures got up to.

The dry, craggy hills of the Diablo Range in the East Bay are home to snakes that love heat and tolerate dry conditions. Hiking Mount Diablo, if you’re very lucky you could see the threatened Alameda whipsnake ( Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) living up to its name, chasing down an unfortunate lizard so fast that it’s a stripy streak. Just five populations are known to remain in Contra Costa and Alameda counties. In years of hiking the area, I have only seen one. More likely, you may see the area’s own garter, the Diablo Range gartersnake (Thamnophis atratus zaxanthus), diving into a cattle pond to chase tadpoles.

Northern California’s only dangerously venomous snake, the northern Pacific rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus), is found in the Diablo Range in abundance—hence the warning signs at trailheads around here. A bit of caution is warranted, but no need to fear. Venom is costly for snakes to make, and they gain nothing by using it up on something too large to eat. Most venomous snakebites in the U.S. happen when somebody is harassing or trying to kill a snake. Pay attention to where you put your feet and hands, wear proper footwear, keep dogs leashed, and don’t mess with any rattlesnakes, and your chances of being bitten dwindle to the point that the cows you’ll pass on your hike pose a greater risk to your health.

Once you’ve braved the cows and made your way to, say, a rocky ridge, start peering at rock piles, especially sun-dappled ones that offer the residents in their nooks a nice temperature gradient. You might even find a rattlesnake den, a spot where rattlers overwinter. Usually it’s a deep fissure that offers insulation from temperature

A rubber boa’s foe may struggle to make head or tail of it, given how similar its two ends look.

swings. These can be spots for various roommates of other species—gartersnakes, whipsnakes, racers, and gopher snakes have all lodged with rattlers. A tip from expert Emily Taylor: Look for a pregnant female in July or August. When it is too hot to lie in the full sun, “she may have just one loop of her body sticking out in the sun,” Taylor says. That’s “the loop that contains all her fetal rattlesnakes, with eight or 10 little baby snakes in there.” Mom is doing something that only snakes, with their long bodies, can do: By heating up a segment of her body, she speeds up her babies’ development.

In fall, you may see the newborn rattlesnakes tangled up in a wad with their siblings, each as cute as a button, with only a single tail nubbin rather than a full rattle. They are no more dangerous than adult rattlesnakes, contrary to myth. Actually less so, because they have less venom. You may see their tired mothers nearby, deflated after giving live birth. Seeing their unblinking eyes and unwavering expressions, you might assume they’re unfeeling. But research shows that pit vipers form connections with their young and siblings. They’ll go their separate ways, then converge when they return to the den. And in difficult situations, rattlesnakes stress less with another snake nearby.

Rarely, you may see two males raising themselves off the ground, teetering as each tries to lift his head a little farther skyward than the other, shoving but never biting his rival. In this rattlesnake “combat,” the bigger snake typically wins by pinning the smaller and hopefully impressing any female rattlers nearby. But don’t count on seeing this on your first rattlesnake sighting or even your hundredth! ◆

Starting your snake journey

In the past year, California snake enthusiasts gained two new fantastic resources. California Snakes and How to Find Them, by Emily Taylor, is full of personal stories, natural history, and tips. California Amphibians and Reptiles, by Robert Hansen and Jackson

Shedd—biologists with decades of experience investigating California’s reptile species—is a trove of range maps, identification keys, and info on every imaginable morph and variety of species. Both books are stunningly illustrated. Thanks to guides like these, there’s never been a better time to start looking for snakes. If you do, I hope you will come to love them, and look forward to even fleeting glimpses of a sinuous coil flowing into the tall grass beside a trail.

Traffic from Highways 24 and 13 in Oakland roars as we walk under the shade of oaks and redwoods. To our left is a stand of fluffy emerald wild fennel, which 29-yearold tea-maker and edible wild plant educator Cindy Li kneels down to pick, smell, taste, then collect, placing a sprig of the herb into crinkled paper bags that formerly held pastries.

Li has been picking fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) since she could walk alongside her mother, who would later fold the licorice herb in with pork into homemade dumplings. Fennel began its invasion in California over a century ago, with deep taproots that survive disturbed soils and a generous seed bank birds love. Its dense stands have become so pervasive, the herb is now naturalized in North America.

Li and I share similar backgrounds: the daughters of Chinese immigrant mothers who raised their children in Los Angeles County. But it’s clear she knows quite a bit more than I do about plants. As a child, she studied leaf shapes and patterns in the garden cultivated by her mother, who grew and foraged for nearly all of their produce and carried around little bags on hikes with Li to collect greens for that night’s meal. “I don’t think I learned the word foraging for a long time,” says Li. “It was just my mom and I would go on walks or we’d go hiking.”

For the past few years, Li has led what she calls forays, during which she teaches edible plant identification at green spaces in the East Bay and San Francisco. Harvesting is illegal in most public spaces, and she makes it clear the foray is not a harvest. Instead she focuses on wild herbs— those that are abundant and often invasive. She also runs an edible plant Instagram account, with over 20,000 followers, where she reminds people to follow local rules.

I can see why her classes and videos are popular—between bursts of laughter and easy smiles, Li teaches with an infectious enthusiasm grounded in a mindfulness of her surrounding environment. If the plant is a native, like miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata), Li plucks what she needs from the top of the plant, encouraging its growth. If it’s nonnative, like fennel or wild garlic, she’ll uproot it from the base.

And as I follow her gaze, study her techniques, and find familiar smells and tastes, I begin to recognize edible plants everywhere. If plants had leafy hands, they would belong to California mugwort ( Artemisia douglasiana), minty and a touch tart, which Li likes to steep in hot water for relaxation. Wild three-cornered garlic ( Allium triquetrum) grows rampant, with pungent, tangy stems—good for a stirfry, bad for native plants—but otherwise appearing harmless, adorned with delicate white flowers. Just bloomed are the citrusy cousins—pale-pink sorrels (Oxalis incarnata) and yellow Bermuda buttercups (Oxalis pes-caprae)—easy to spot, pleasantly sour to chew on in small amounts, and also nonnative. It appears that the most flavorful flowers also have the most territorial tendencies.

centered around certain plants. “I feel like one thing that I was really missing from my group forays that I’ve gone on with other teachers or leaders was that all of them were white,” she adds. “There was no discussion and no context set about the history of foraging on this land.”

Li tells me the story of rooreh, the Chochenyo word for miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata), each bowl-shaped leaf adorned with a tiny white flower in the center. It tastes mildly sweet, and mostly watery, like spinach. During the Gold Rush, scurvy-ridden miners “observed the native people eating the plant, and they started eating it too,” says Li. “It has a lot of vitamin C and vitamin A, so it cured them of the scurvy problem.”

As we walk along the road, rooreh springs from the sidewalk cracks, just a few feet from cars whizzing by. While one might think the sidewalk un-forageable, a UC Berkeley study in 2019 showed that leafy greens like chickweed, mallow, and sour grass, growing through the asphalt and along roadsides in over 30 locations in Oakland, Richmond, and Emeryville, were safe to eat and sometimes more nutritious than domesticated leafy greens, after rinsing.

Plants are often deemed “inedible” in American foraging books due to Western conventions of flavor, says Li. So edible plant education is mostly

“You don’t have to go somewhere really far away,” says Li, “to see interesting plants.” ◆ Jillian Magtoto

Point Reyes National Seashore: 2 qt a day of some berries and apples; 3 lbs of mushrooms a day. No foraging for sale.

Salt Point State Park : 2 lbs a day per person. Organized groups larger than 10 people require a permit. No foraging for sale.

Jackson Demonstration State Forest in Mendocino Count y: 1 gal of mushrooms a month. Some commercial foraging allowed.

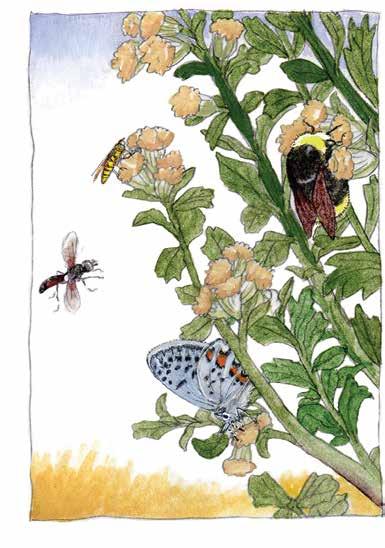

by Ken-ichi Ueda | illustrations by Laura Cunningham

it’ssummer and it’s dry. You can’t remember the last time it rained. The warm wind blows past your ears, the fallen tree leaves and withered blades of dead grass crunch beneath your feet, and you’re thinking about fire, and maybe getting out of town, at least for a little while, maybe to a cool, rushing Sierran creek, lined with lilies and ranger’s buttons, hearing the water burble and a nutcracker cry instead of that worrying crunch.

But that’s because you’re an animal. If you don’t like the way things are, you can move. Plants don’t have that option. When things get too dry, or too hot, or too cold, or too wet, plants can’t skip town and rent a place somewhere nicer. They need ways to survive in place. In our dry summer and fall, many of them just . . . die. Oats, chia, goldfields, and scores of herbaceous plants have children in the form of seeds and drop them onto the soil or throw them to the wind and then just kick the bucket. This is why our grassy hillsides turn such a disappointing shade of taupe around June and become so disturbingly crisp a month later: they live fast and die young, but not before having a ton of hardy kids that will replace them when the rains return. Almost all of our favorite wildflowers are like this too. It’s called the annual lifestyle.

The other way is that of those oaks and their crunchy leaves: invest in roots to tap water deeper in the soil or even in rock, seal in your moisture with thick stems and waxy leaves or shed everything aboveground when things get dry, and just tough it out. Live long and prosper! Manzanitas, death camas, buckeyes, hound’stongues, and countless other sturdy plants follow a similar path: the perennial lifestyle.

But what most local annuals and perennials have in common

is that they do their most important work, growing and breeding, in spring and early summer when times are good and water is abundant. That’s when the oaks are filling the air with pollen (much to the chagrin of some humans) and when our phacelias and mule’s ears and thistles are at their most ebullient. But when the party’s over, the annuals set seed and die, and the perennials start living on a budget while they wait for rain. Many humans choose to live in lowland California because we don’t have a harsh and freezing winter, when ice would destroy a tender leaf and snow could blot out the sun, but the aridity of our dry season can be just as brutal for our photosynthetic neighbors. Better to retire until the rains return.

Except, deep in the hot, dry doldrums of the Bay Area’s death sleep, a flower blooms.

Actually, a lot of flowers bloom. Seemingly in defiance of all good sense and logic, some plants of our scrub and grassland not only can perform their most difficult and essential metabolic work at the most oppressive time of year, they only do it at that time, with gusto and good cheer. Annual or perennial, they grow roots and leaves during winter and spring like their fellows, but then instead of dialing it back and retiring to the soil as roots or seeds, they double down and spend like maniacs, growing even more aboveground and blooming and reproducing long after the sane plants have called it a year. It’s like buying a house with the last of your savings, like running an ultramarathon after running a regular marathon, all with a smile on your face, every single year. Some species turn hillsides yellow, others provide flashes of crimson and sapphire, many scent the air with a perfumer’s panoply of aromas, an entire show that you might miss while driving east

toward your Sierran creek.

So who are these gonzo flowers of fire season? How do they achieve the seemingly impossible? And why?

Coyote Brush: the party perennial

Coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) probably doesn’t top your list of iconic plants of the Bay Area, but it should. In grasslands or in scrub, if you’re looking at a shrub in this part of the country, it’s probably coyote brush, and that’s because it’s hardy, prolific, aggressive, and tough to eradicate. Sound like a weed? In some situations, it is! It can invade grasslands and transform them into shrublands, displacing grassland species and creating more fuel for fire. It also creates habitat for brush rabbits, wrentits, rain beetles, earthtongues, and countless other plants, animals, and fungi that depend on it for shelter, feed on its shoots and roots, or grow from the duff of its decaying leaves and branches. In a volatile, postcolonial, climate-changed world, coyote brush is a native plant that isn’t just surviving. It’s thriving and helping others thrive too.

But its craziest trick: It blooms in September and October. It carries out a blush-inducing bacchanalia of reproduction at the most bone-dry time of year. Entering a flowering stand of coyote brush can smell like stepping into a chamber of vaporized honey and sound like you’re nearing a hive for all the buzzing bees, flies, and other insects zooming around to

feast on one of the only nectar sources around. When the party’s over and it’s time to set seed, the female plants can produce such a fleece of white, wind-dispersed seed-tufts as to look practically mammalian.

So how does coyote brush pull this off? First, deep roots. Almost all summer blooming plants employ this technique, whether perennial or annual, because the most consistent and persistent source of water is underground, the deeper the better. Gardeners will recognize that even in the driest months, digging just a foot or more can often reveal some damper soil. Andrew Wright, a master’s student at UC Berkeley in 1928, painstakingly dug up a few coyote brush individuals “with a small ice pick” and found that they had sent down roots deeper than nine feet, even when the aboveground plant was hardly taller than three feet. Given that a mature coyote brush can be twice as tall or more, these roots are probably extending one to two NBA basketball players beneath the surface in search of water. There’s more of the coyote brush belowground than above.

Another of Wright’s findings was that in addition to those deep roots, coyote brush maintains a network of shallow roots. These help it exploit another important source of summer moisture in coastal California: fog. Working on a thesis at UC Berkeley almost a century after Wright, plant ecologist Allison Kidder proved coyote brush supplements its water supply with fog, particularly as seedlings, suggesting fog may be important in the plant’s ability to invade grasslands. She also

Coyote brush hosts an interrupted hornet fly (Spilomyia interrupta), yellow-faced bumblebee (Bombus vosnesenskii), Acmon blue (Icaricia acmon), and a Cylindromyia fly.

found, amazingly, that coyote brush loses water at an increasing rate from spring through fall, culminating in its bloom in September and October. The less water it has, the more it spends, a spendthrift party animal almost until the rains come again.

After traversing a beige grassland as dun as the dullest pair of hiking pants at REI, the sight of vinegar weed (Trichostema lanceolatum) is a revelation: shining verdigris leaves speckled with shocks of reaching purple-blue flowers. Summoned, you approach, reach to touch this crystalline living gift amid a mat of death, stoop to inhale its swee–HOLY CRAP WHAT IS THAT SMELL?! Vinegar weed is a looker, but it is also a stinker, emitting a bouquet of organic compounds equivalent to an odiferous roar: DO. NOT. EAT. Much like coyote brush, vinegar weed bolts and flowers fairly late in the year, blooming at a time when there’s less competition for pollinators and the sunlight is plentiful. But this poses a problem: If you’re the only green growing thing around, you might look attractive to pollinators, but you also look awful tasty to

herbivores desperate for a juicy mouthful. Some summer-blooming plants dissuade such attention with a medieval armament of spikes (like star thistle and spikeweed), but vinegar weed has chosen better living through chemistry. It literally exudes acetic acid, better known as vinegar, and if you pretend to be a deer and stick your face in it, you will immediately understand why deer don’t do that. Its effervescent pungence will startle you awake, but it doesn’t exactly whet the appetite. In addition to vinegar, vinegar weed emits an array of interesting volatile compounds, including terpinen-4-ol, the primary component of tea tree oil and a powerful toxin acting against bacteria, fungi, mites, and even other plants. This compound has been shown to inhibit the gut microbiota of deer, suggesting that in addition to simply exposing them to an arresting smell, eating vinegar weed might arrest digestion in those desperate mammalian herbivores.

Curiously, the chemical armory of vinegar weed has been shown to inhibit the germination of other plant seeds as well, leading some experts to theorize that it may stunt or stop the growth of other plants around it, but field experiments have shown that despite that toxicity, it has no significant effect on its neighboring plants in the real world. Terpinen-4-ol has also been shown to be toxic to mosquito larvae, so it seems probable that while these defenses may not do much against competing plants, they do probably guard against caterpillars in addition to deer and cattle.

Let’s be frank: When it comes to California’s many botanical wonders, no one is wondering much about turkey mullein (Croton setiger), also known more poetically (if not more admiringly) as doveweed. This relative of poinsettia has little of its Christmas cousin’s pizzazz, opting instead for muted blue-green foliage, demure and tiny flowers of a similar color, and at best ankle-high stature. If you find yourself charmed by this gray tribble of September, it might be for lack of other options.

But you wouldn’t be alone. In addition to moisture-retaining, sun-reflecting hairs and potentially toxic foliage (it was used as a fish poison by California Indians and cattle tend to avoid it), turkey mullein charms an unexpected cadre of admirers: spiders. Researchers at UC Davis noticed that the hairy leaves of turkey mullein often collect pollen that may be blowing around in the hot fall winds. They theorized collecting pollen might attract generalist insect predators that feed on other insects that would otherwise eat the turkey mullein. To test this, they coated some wild turkey mullein with pollen, left some others alone, and counted the bugs on both. Weirdly, while they didn’t see too much difference in the abundance of insect predators on the plants with added pollen, they observed a marked increase in the number of tiny spiders on those plants. This is a bit of a mystery, because almost all spiders are obligate predators that only eat other animals. Why would they care about pollen? But apparently, even though these

researchers didn’t observe it in their experiment, some spiders do supplement their diets with pollen, so perhaps turkey mullein adds to its defenses against insects by setting out an appetizer for arachnids that then, for their main course, protect the plant by devouring aphids, caterpillars, and other hungry, hungry marauders.

Are you noticing some patterns here? From deep roots to chemical defenses to luring in useful thugs, the flowers of fire season often

adopt the same strategies to survive in dry times. But tarweeds? They do it all, and more.

Tarweeds belong to a tribe within the sunflower family containing many faces familiar to the California flower fancier, from the shrubby seaside woolly sunflower of the coast (Eriophyllum staechadifolium) to the hill-coating golden carpets of Monolopia to be seen in Southern California’s Carrizo Plain and elsewhere. Believe it or not, the gargantuan Hawaiian silverswords you may have seen on top of Haleakalā or Mauna Kea are also tarweeds, the descendants of a Californian species that probably hitched

a ride across the Pacific on (or in) a bird about five million years ago. Californian tarweeds bloom at different times of year, but it’s the summer- and fall-blooming species that help define the look and smell of our dry season flora, from the superabundance of white (or yellow) hayfield tarweed (Hemizonia congesta) in areas with fog to Heermann’s, San Joaquin, and virgate tarweeds (Holocarpha heermannii, obconica, and virgata) of the baked interior.