“ ”

How the Line Defined the Early 1900s

Cecilia Bartter

April 2nd, 2023

Decorative Modernisms around the 1900s

Professor Rugare

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Linear Ornament

A. Reverence for the Primitive

B. Architecture in the Americas

C. The Industrial Revolution and Mass Production

III. Abstraction of Form

A. Eastern European Nationalism and Secessionism

B. The Werkbund

IV. Emergence of Emotion

A. Expressionism

B. Decadence and the Unconscious

V. Reformed versus Primitive

A. Fetishization of the Primitive

B. The Simple Modern Man

VI. Ornament in a Modern Sense

A. New International Style

B. Biophilic Architecture

C. Conclusion

VII. Bibliography

Bartter 2

I Introduction

A young toddler has several colors of crayon balled in her tiny fists Intensely focused she furiously mashes them against a sheet of scrap paper, forming a concoction of color and line; form with placement known only to herself. She finishes her first masterpiece, which is promptly shoved towards her mother. It now hangs on the refrigerator until the child is an adult, a lasting mark of her first ornament.

In his 1927 essay, The Mass Ornament, Siegfried Kraucer mentions how one can determine the nature of a historical time frame or movement by analysis of surface level expressions. That “The fundamental substance of an epoch and its unheeded impulses illuminate each other reciprocally” (Kraucer 75). Kracauer examines the historical development of the mass ornament, tracing its roots back to medieval carnivals and festivals. He notes that the mass ornament has evolved over time, becoming increasingly standardized and homogenized in response to the demands of industrialization and modernization. The mass ornament, according to Kracauer, is a reflection of the dominant values and ideologies of society This applies especially to the early modernist period of art and architecture. Around this epoch of mass technical and social change, two incredibly distinct forms of ornament and design arose, yet both were centered around the form and abstraction of the simple line. The line defined early 1900’s art and architecture in these different ways, utilizing both linear regularity and expressionistic abstraction. This incredible dichotomy between linear and curvilinear styles provides a look into the cultural and societal psyche of the period, as well as provides a new stepping off point for furthering style and design in a modern, technological age.

Bartter 3

II Linear Ornament

To properly discuss where the linear form comes from one has to cast a gaze back to the very beginning of human construction. In Gottfried Semper’s essay, The Four Elements of Architecture, he argues that “it is well known that even now tribes in an early state of their development apply their budding artistic instinct to the braiding and weaving of matts and covers.” (Semper 103) Similar to the child scribbling on paper, the first true ornament and design of architectural canon was the line. A rectilinear grid of woven fiber was a catalyst for linear design with a shadow that continues today. The German words Wand (wall) and Gewand (dress) share the same root word, indicating the woven material itself. Similar to Kraucer, Semper also writes that ornament is an essential part of building design and can reflect the identity and values of a society and argues for the importance of understanding the roots and principles of architecture in order to create structures that not only function but are pleasant. This was quite present in the craftwork period of design, especially as designers attempted to bridge the gap between traditional styles and designs, and modern, industrial methods of production. This period utilized a lot of linear forms, representative of the logic that was believed required to transition to a modern age and marked a significant departure from the continually embellishing of historicist design and its precedents of baroque and rococo.

In the United States, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House (1909-1910) in Chicago stands as a beacon of linear design and ornament.

Bartter 4

The decoration comes from complete linear regularity of form. Long roman bricks band the stretching facades to emphasize the horizontal. The vertical masonry joints are even darkened to highlight the simple lines in parallel. Overhangs stretching over forms which also extend the linearity into the rest of the site, while concealing the interior space. Wright’s main style of architecture highlights the horizontal line, preaching simplicity and regularity. In his Westcott House (1908) in Springfield Ohio, Wright even emits a gutter downspout to not distract from the pureness of his rectilinear forms.

Continuing to look at American design, the skyscrapers of Louis Sulivan highlight the regularity of straight lines and a matrix for ornament. His Guaranty Building(1896) in Buffalo, New York, is a great example of the grid and tiling

Bartter 5

Frank Lloyd Wright, Robbie House, Chicago, IL 1909-1910

Image by Tom Rossiter, date unknown

possibilities of linear patterning and ornament. Sullivan also contributed a large body of work in wallpaper design which is evident in his physical decorative form. Tile panels of highly detailed ornament cover the structure in a pattern taken from a heavy embellishment of linear patterns. Part of why this style became so successful was that it was created so early and almost synonymously with the typology of the skyscraper. It was partially because of this association with new industrialization and construction methods, utilizing mass production and steel, that linear elements developed so much in America. They continued to stay as a logical and rational decoration method of design and were influential in the later development of the New International Style.

Part of the progression to easily fabricated repetitive patterning for ornament was the rise of mass production and technological innovation in this time. Because manufacturers were able to very quickly fabricate repetitive patterns, that style of design was quite often used in technologically developed areas like America and Western Europe. Facades could be made up of a few designed tiles and furniture could be constructed quickly and cheaply. With this speed comes the cost of detail, at least at the beginning. Due to manufacturing limitations, the primary form of ornament used consisted of an intricate pattern of all straight lines. The regularity of the grid structure also added to the overall ornament and played a key role in the form of the building.

This in part created a subconscious connection between a “dignified” industrial society and the regularity of linear ornament. Mass production and cheap mechanization also allowed more regular people to experience this form of decoration and spread it.

Bartter 6

Charles Mackintosh’s furniture is a great example of this, each piece is made up entirely of rectangles and designed along a grid format. His Hill House Chair (1902) shows this hyper-regularity along the chair's back, moving away from previous ergonomic forms that curve and flow, in exchange for a regulated angular structure.

Bartter 7

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Hill House Chair 1902 Render by Pixel Hearts, 2018

III Abstraction of Form

The rationality and rigid structure of this particular linear form of design and ornament was heavily used in Eastern Europe, specifically in the development of Nationalism and Secessionist ideals. For many new countries that were struggling to find a national identity, artists and architects looked towards historical precedent present in the craftwork produced to develop a style communicating national pride. These mostly consisted of regular linear patterns that were then applied on a larger scale to develop a supposed national design language. Czech architect Jan Kotěra’s Národní Dům (1905-07), or national house, in Prostějově, is a great example of this.

While the building seems to be sparse of detail, there is no shortage of carefully placed interest. Linear bands of ornament and window wrap the building and emphasize the horizontal nature of it. Tight floors and shallow roofs are used to stretch the building,

Bartter 8

Jan Kotěra, Národní Dům, Prostějově, Czech Republic 1905-1907 Image by Karel Boromejský Mádl, 1922

calling attention to the linear aspect of the design. Kotěra employs a similar strategy but rotates it 90 degrees in his Muzeum Východních Čech (1908) in Králové. In almost what seems like a precursor to the popular American Art Deco movement, extreme geometric striping bands the entrance to the building, where the ornament lies in the linear form of the building itself. Red and tan coloring is also used to emphasize these geometric forms across the dimensions of the building. Kotěra himself said that he was inspired by industrial themes he saw in his youth. This marks the direction that architecture started to move in as a whole, where the form, ornament, and design of a building comes from the structure and capabilities of itself. There was a process of design thought around the time that ornament comes from the natural characteristics of a material, so it would only make sense for architecture to follow and start to be defined by the logical and linear industrial process of stability and construction.

Josef Maria Olbrich was also a key figure during this period, although he focused his work in Germany. One of his more interesting buildings, Hochzeitsturm (1907-08), located in Darmstadt, Germany, shows off a very interesting form of rectilinear ornament. The building itself is a massive masonry tower with seemingly very little embellishments. The ornament placed in the tower comes from key moments where parallel lines frame small rectangular sections that look cut out from the rest of the structure. This sparse regularity of linear ornament creates a very logical understanding of the structure and its form. The roof of the tower is really distinctive as well. What looks like 5 massive lines grow straight up from the tower and round off at

Bartter 9

the end. The abstraction of this linear element has grown from a simple ornament to being the basic element of the building itself.

During this period country’s pursuit of a new national identity, a movement started in Germany known as the Deutscher Werkbund. The Werkbund was a mass arts movement involving artists, architects, designers, and engineers that led an effort to integrate historic craft into industrial mass production. A key figure in the architecture realm of the Werkbund was Peter Behrens. One of his iconic buildings, the Peter Behrens-Bau (1920-24) in Frankfurt, represents the German push towards blending historic with industrial while utilizing linear ornament through mass and form.

Bartter 10

Josef Maria Olbri homas Wolf, 2022

Much like other more expressionistic leaning buildings, the Behrens-Bau finds its main ornament in the material and form of the structure. The variegated masonry is arranged in rigid lines that span the facade, extending the form in the horizontal axis. These bands of brick are periodically interrupted by vertical indents that frame the windows. The windows themselves are quite thin and tall, further adding to the vertical linear elements.

Many elements of the Werkbund were also aimed at catching Germany up so to speak with England and America in terms of industrial culture. Another one of the most influential figures leading the Werkbund, German architect Hermann Muthesius, did

Bartter 11

Peter Behrens, Technical Administration Building of Hoechst AG “Behrens-Bau”, Frankfurt, Germany 1920-1924 Image by Infraserv GmbH & Co Hochst KG, date unknown

several studies of English vernacular design because of his distaste of current German styles. The “Jugendstil and Secession style… are “artistic fantasies” (Phantasiekunst), inefficient, uncomfortable, and emotionally profligate creations” (Muthesius 81). These more flowing, curvilinear, and abstract styles lacked a sense of sound common sense, or gesunder menschenverstand as Muthesius says. He believed that a properly balanced and sensible view of design was paramount to cultural development, which he found in British intellectual and cultural life. “Furniture, for example, should be simple and comfortable, and the combination of fittings and moveable goods should be coordinated in a manner that simultaneously relaxed the observer and encouraged his or her aesthetic senses” (Muthesius 73).

This more rational sense of English precedent design is very evident in Muthesius’ Haus Freudenberg in Berlin. The form is very simple and clean, and it draws heavily on English Tudor styles, but using brick in place of stone and plaster The building is L-shaped with the main facade being angled from the center. This facade has all the ornament present in the building, creating a linear matrix of decorative beams. The densification of detail in this one particular area is a very functional use of ornament as it draws the viewer's eye to the area, showing them where to enter the space. Similar to American modernism, short horizontal bands of windows are also used in the facade, yet these exist purely as a functional element and not as a decorative piece of the facade.

Bartter 12

IV Emergence of Emotion

With every movement of great change, there accompanies a movement following it. This secondary movement is a rejection of the ideas and values intrinsic to the first movement. The rejection of rational linear form and ornament was most commonly associated with calling on ideas of emotional expression and more painterly qualities that art can have. One prevailing artist motif was the idea of the “hands of the artist” That is, representation of the physical quality of the painting itself, brush strokes, paint build up, etc. There was a clear delineation from the previous realist expression and it was replaced with abstract ideas and a focus on how they were represented and the process of which they were represented by. A good example of this is a painting by the Swiss painter, Eugene Grasset, Young Girl In The Garden

Bartter 13

Eugene Grasset “Young Girl in the Garden” Date unknown

While not particularly what one would call abstract by more modern standards, Grasset’s style is much more impressionistic than artwork that was being produced previously No longer focusing on realism, color, light, and texture are all used in complex curves to define the ambiance and emotion of the piece. More messy splotches of color become painterly and carry purpose in conveying meaning. Grasset also created a fair amount of graphic design in the form of floral patterns, using the same curvilinear process of form. His print, Nasturtiums (1897) is a great example. A big element of art nouveau was curving stem like elements which this pattern uses in multiple ways. There is a main stem curving through the print but several smaller stems bifurcate from it, curving in even more absurd ways. The leaves of the flower that dot the stem are also quite a contrast to the more regular forms of linear ornament. Each leaf, while relatively circular, is rough and not an exact curve. This carries a sort of natural primitivism that was believed to be more aesthetically pleasing and more refined emotionally

This wasn’t solely for the artistic community, however, there was a large role played by the architectural stylings as well. French architect, Hector Guimard, uses an incredible amount of curving art nouveau-esque detailing and ornamentation. One of the most prominent examples of this is the entrance door to his Castel Beranger (1894-96) in Paris. Castel Beranger is most commonly known as being the birth of art nouveau as well as being one of the most iconic buildings in Pairs. The entrance in particular demonstrates this abstracted curvilinear ornament and emotional design.

Bartter 14

Starting at the door, corten steel and copper intertwine in undulating malleable lines that establish the theme for the rest of the ornament. After entering one finds themself in a grotto-esque transition space. The walls of this area are covered in a weathered looking glazed ceramic tile with raised curving ornament that looks almost like a paleolithic carving on jagged rocky cave wall, albeit quite a bit more extracted and

Bartter 15

Hector Guimard, Castel Beranger, Paris, France 1984-86 Image by Groume, 2013

diligent. Along the walls are also metallic structures that form branches that sprawl out over the walls and ceiling in an organic but highly elegant matrix. This metal work resembles an abstracted form of tree branches or plant stamps, curving around the space. Guimard became quite known for these abstracted natural curve ornaments and continued to implement them as ornaments in his designs. His Paris Metro Entrances (1900-1903) show off these curves very well. Guimard blends ornament with the structure itself, highlighting the malleable and formative properties of metal.

This style wasn’t endemic to France, however It was quite well liked in Austria as well and used heavily by German architect Otto Wagner. His Karlsplatz Stadtbahn Pavillon (1899) is a metro station in Austria with complex curvilinear ornament but in an earlier fashion. Curves are more subdued and less prevalent but still clearly there. The panelized white facade has gold printed plantwork for ornament that wraps around the structure. This plant and sunflower motif even expands to the ironwork that adorns the roof. The same curves are densified and stretched out forming golden knotted bands along the roofline.

Bartter 16

A movement of the time, known as the Decadence period, also helps establish emotional irrationality through curve in art. One artist of the time, Felicient Rops, does an incredible job of establishing this anti-rational message through extremely graphic artwork. Most of his pieces are erotic in nature, diving fully into human emotion, indulgence, and social decadence. He depicts women peculiarly, the material is borderline pornographic but the subjects are empowered, something that was absolutely not common for the period. His portraits exalt women for their strength, living a life racked with death and the overreach of the establishment, restricted by religious and social dogma. This is work that could only really exist within the bounds of curve and emotion, a push towards the appreciation of a beautiful and irrational human existence.

Bartter 17

V Reformed versus Primitive

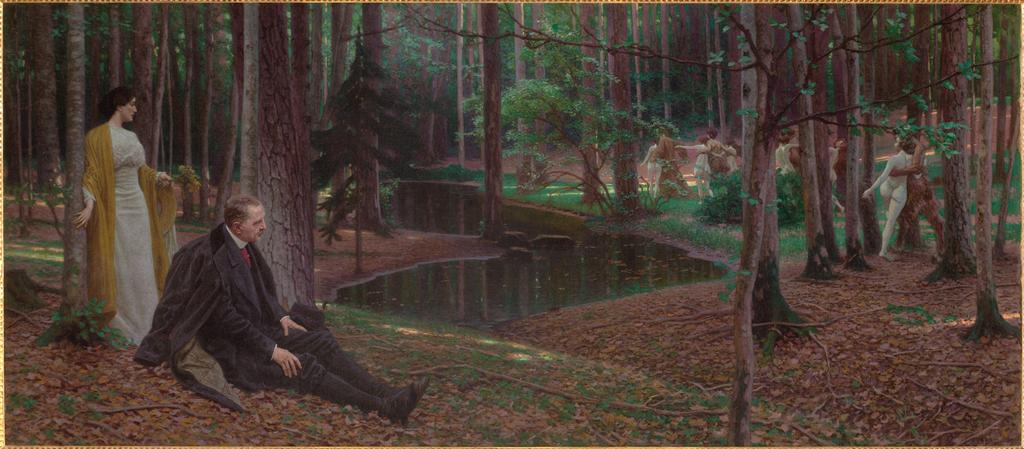

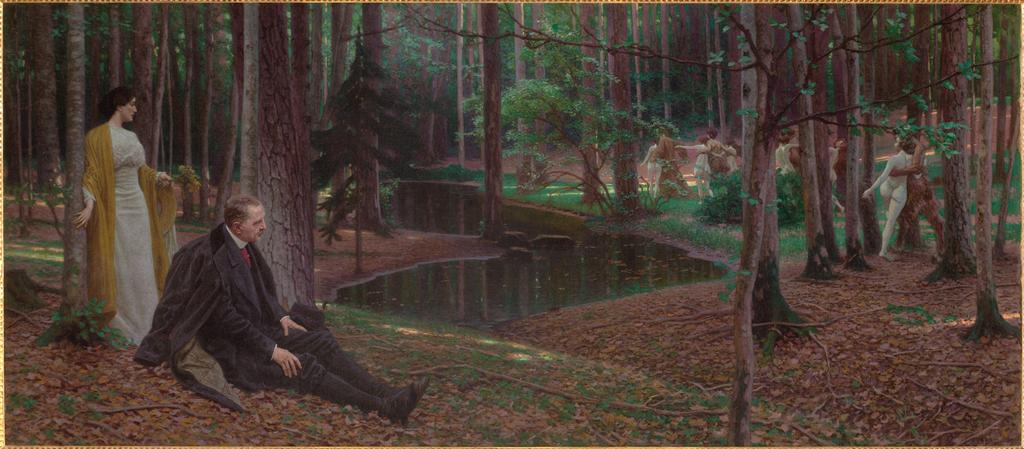

Part of the reason such a dichotomy arose between curvilinear and angular ornament is because of their social association. To many Europeans, curving forms quickly became synonymous with the primitive. The emotional aspect of form was seen as inferior to a supposedly more logical and rational angular ornament, which quickly shifted to a lack of ornament all together At first this association between curve and primitive was embraced by those in anti-burogise movements like abstractionism, Jugendstil, impressionism, and decadence. There was a fetishization of the primitive and its potential for raw emotive expression, unbounded by the shackles of modern industrial life and society. Many painters used this fascination to form their bodies of work, such as Felicien Rops. Austrian painter Maximilian Lenz, however, takes this a step forward. In his Le Peintre Friedrich Koning et Ida Kupelwieser dans une Foret (1910) uses the other painters’ fascination as the subject.

Bartter 18

Maximilian Lenz, Le Peintre Friedrich Koning et Ida Kupelwieser dans une Foret, 1910

Curving trunks and twisting branches and roots lay the scene for a dream-like vision of a painter and a woman witnessing an occult and mythological dance in this forest. The curves of the bodies in motion seem to mimic the slight tilts of the trunks, reveling in a sense of primitivity and early humanity. The dancers themselves are mythological creatures- satyrs and nymphs. Not only are these ancient myths but a representation of early humanity, crossed with animals and trees, running naked in the woods. Other painters, such as Egon Schiel, took the ideas of the primitive into his work as opposed to the actual subject matters. His work focuses on sex, death, and discovery, these all being core human attributes and emotions. Many of his portraits also present a fascination with the nude self, something that could be traced to early biblical stories like casting out Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden.

Ideas of the primitive were not seen in this positive light by everyone, however

Many made associations between primitive, savagery, and degeneracy An Austrian architect and art critic with entirely too much time on his hands wrote about this degeneracy in his manifesto, Ornament and Crime. Loos’ main argument throughout his essay is that “the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects” (Loos 20). Loos had a passionate belief that the formal use of an object and what function it provides should reign supreme over the form. In a perfect world for Loos, objects would have no value outside what they were explicitly designed for; visual pleasure was something for children, savages, and degenerates. Loos’ writings have severe classist, racist, and xenophobic undertones. He relegates

Bartter 19

that the man who cannot afford to live comfortably in the modern age is nothing more than a twelfth century peasant. He calls polynesian and african tribes degenerate savages for the way they display art on their bodies. He grows frustrated that he lives in a place where people from other cultures enter and spread their views on ornament and society. “The stragglers slow down the cultural evolution of the nations and of mankind; not only is ornament produced by criminals but also a crime is committed through the fact that ornament inflicts serious injury on people's health, on the national budget, and hence on cultural evolution” (Loos 21). Loos was not just talk, he designed a few buildings as well, with his most famous being Villa Muller (1930).

Bartter 20

Adolf Loos, Villa Muller, Prague, Czech Republic, 1930 Image by Miaow Miaow, 2007

Villa Muller sums up Loos’ feelings on design fairly well. He really meant no ornament.

Many architects that set up the stage for design precedent for the next century took Loos’ philosophy to heart. The father of the new international style is no exception. Swiss architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, or Le Corbusier, has a style that continues to push towards a “cultivated” society free of decoration. Le Corbusier’s most influential and famous work, Villa Savoye, not only demonstrates this new modernism but also establishes a return to linear form and hard angles.

In his design, the techtonics of the building become the ornament itself. A long window stretches across the facade, the only contrast to the blank white walls present everywhere. The main box of the house is supported on a regular grid of piers, continuing this linear theme and suspending the main focus line, which is established to be the window strip as running parallel to the ground line without interacting with it.

Bartter 21

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, 1928-1931 Image by August Fischer, date unknown

VI Ornament in a Modern Sense

When people think of “modern architecture” they probably think of white concrete mass with plane facades and hard edges, and while that is certainly an aspect of some modern designs, modernism is infinitely more complex. Modernism exists more as a fluctuating wave of curve and straight ornament.This shift from an ornamental view, using curves and abstracted, embellished forms, to a more formal and objective view, one with boxes and not much else, represents a shift in global culture as well. There was a notion that in the early modernist period and before, decoration was subjective. It was fashionable, confusing, and irrational. Curves and emotion were seen as feminine traits which was apparently an issue. Advocates for a new, objective style believed that it would be instrumental in guiding society towards a more rational and industrial culture. This style pushed necessity, clarity, and a transcendent approach to design. The New International style rose out of this need to integrate traditional techniques and imply them in a modern, industrialized age.

One of the pioneers of this style was the German architect Mies van der Rohe. Van der Rohe was the last director of the Bauhaus, a German modernist institute, and carried his architectural language to America following the rize of German fascism and the Nazi takeover. A key aspect to his design is utilizing framing and transparency to highlight linear regularity, finding ornament through material and structure. Van der Rohe’s S.R. Crown Hall (1950-56) shows off its structure in such a highly rigid and organized manner that it becomes the ornament of the building itself. Crown Hall,

Bartter 22

which houses the College of Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, is primarily made of massive glass curtain walls which are separated into equal bays by black steel fins that wrap thinly around the building. The contrasting use of glass and black metal gives the building a very logical air to it, highlighting the structure and the regularity of it, while celebrating the function of the building by allowing view to the interior programs. A common modernist design trope is that the form of the building should be determined by the function it houses, which translates to the ornament being defined by the structural systems used. Another great example of this kind of design can be very clearly seen in his Farnsworth House (1951), where glass and transparency are used to achieve sparse ornament.

Bartter 23

Mies Van Der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois, 1951 Image by Victor Grigas, 2013

The basic structure of the dwelling is highlighted and celebrated, done so by the white painted steel frame. All walls are floor to ceiling glass, turning the house into a see-through window of sorts. This lack of any other structural reference and design accentuates the vertical piers even more, enforcing their rigidity and regularity. The transparency also lends to the exterior landscape as a facade, whether that be seen through or reflected against the glass. What seems to be a compromise between extremely rigid, linear structure and mechanical support, and natural characteristics of flowing ornament, slowly grew to be more and more common with architects in the post war age. In his essay series “In The Cause of Architecture”, Frank Lloyd Wright discusses how important topics such as organic architecture, the natural landscape, and material context, shape architectural language and influence design to be more comfortable for the modern person. Wright believes in taking a more holistic approach to design and emphasizes individual creativity in an argument for the creation of buildings that are both functional and beautiful.

Another modernist architect tackled rigidity and repetition in ornament in a very different way from van der Rohe. Finnish architects Alar Aaltro and Elissa Aaltro designed a number of projects in which geometric but simple brickwork was used as an ornamental body This is especially the case in their Experimental House (1952-54), which was, as the name suggests, a house for design experimentation inspired by the freedom granted by different materialism, techniques, forms, and proportions.

Bartter 24

The main ornament of the facade is brick, of course, but it extends beyond pure materiality. All the different styles of brick come together to create various patterned pieces that form a patchwork style. Different sizes of brick coupled with layering styles and color add to the compositional work in creating a rigid grid which allows for variations on a theme. This creates a linear matrix of uniform language while still creating a sense of ornament and interest.

This post war version of modernism has been a lengthy catalyst for rectilinear design for the past few decades with very little divergence, but recently a new design language is starting to take hold. In the constant push and pull of basic design language, architects are starting to move towards curvilinear design once more, still

Bartter 25

Alvar and Elissa Aalto, Muuratsalo Experimental House, Muuratsalo, Finland, 1952-54 Image by Jonathan Rieke, 2013

taking nature as a precedent. This emerging style is known as Sustainable or Biophilic architecture. One of the first examples of Biophilic design as it’s known today can be found in the work of the Danish architect Jorn Utzon, specifically in Sydney’s famous Opera House (1959). Contrary to the popular belief that the design is based off of sailing rigs, the scooping design actually comes from an orange that the architect peeled and then arranged, taking inspiration from the spherical shells as well as flower petals and leaf crowns. Architects have always looked to plants for ornament but increasingly they are looking towards animals and creatures as well, such as in the collaborative project, the Elytra Pavilion (2018), between Achim Menges, Moritz Dorstelmann, Jan Knippers, and Thomas Auer.

Bartter 26

Menges, Dorstelmann, Knippers, and Auer, Elytra Pavilion, London, United Kingdom, 2018. Image by the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2018

This pavilion is constructed entirely of 3D printed carbon fiber filament. The line quite literally takes on form and becomes the structure. The idea is taken from beetle wings, also called elytra, as it is inspired by the same ultra-lightweight construction principles that nature imploys in the wings. The ornament of the structure lies in its woven, undulating nature. This curve, quite like the extremely rigid forms that preceded it in logical design, is extremely rational, using only what’s needed and creating a structure as simply as possible. As technology and design has progressed further into the modern age and as more possibilities have been revealed, what was once ideal or rational has become obsolete and unnecessary. In a modern, twenty-first century architectural space, there is not really just one or two architects who are adapting, pioneering, and using new designs, there has been a shift in the entire industry towards this type of development.

In what might be the purest form of curvilinear ornament and abstraction of form, Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid pioneered a futuristic style of warping and bending concrete. Though heavily criticized, it is indisputable that she was one of the most prolific users of this style, pushing curve to the extreme in creating a building from the line itself. While she has passed, her firm continues to push this specific typology in projects around the world. A more recent one being the Jinghe New City Culture and Art Center competition (2022). The proposed design takes heavy influence from the winding Jinghe River and the valleys carved by it. The structure is a single line that curves through the site in three dimensions, taking on an almost life-like quality.

Bartter 27

Similarly to much of the cannon provided by modern architecture, the ornament of this proposed structure is found in its form and the meandering nature of it. While elegant and curving this was designed in a very logical system that best connects points of interest and circulates through the site. Increasingly the previous distinction between a logical linear system of ornament and an emotional and abstract curving form is blurred as they are blended together by 21st century architects pioneering a smarter built future.

Of course in the time between the early modern period and today’s age, there were several more styles and architects than listed here, similarly for the examples listed. During the craftwork period there were, without a doubt, architects and designers who produced work that is both linear and curving. Similarly, several modern architects created curved designs in addition to the more thought of rigid forms. Even

Bartter 28

Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), Proposed Project for the Jinghe New City Culture and Art Center, Jinghe, China, 2022 Image by ZHA, 2022

the father of painfully unornamented, Le Corbusier, started his career by designing over the top, highly decorated Swiss chalets. However with all of this variance, the core social association remains the same. Straight, linear, regular ornament commonly arose in societies that valued industry, technology, and furthering those ideas of modernity. In contrast to abstracted, flowing, curvilinear design was present where emotion and care was needed to find a person’s way in their rapidly changing world. Neither one is particularly “better” than the other or a superior design, both are simply products of the people who developed them and the world they lived in. Upon reaching this conclusion, designs of today can be further appreciated as they exist as a synthesis between the two different forms. Linear and curve come together to produce designs that are smart and logical, necessary requirements to build safely for occupants and the environment, as well as beautiful and appeal to the emotional comfort of those who see it. Architectural language is an ever changing progression which produces a physical, tangible timeline of design. One can look back thousands of years and still see what those societies built, and with that, what their culture allowed and appreciated.

Bartter 29

VII Bibliography

Semper, Gottfried. “The Four Elements of Architecture”. 1989

Kracauer, Siegfried. “The Mass Ornament”. New German Critique, No. 5. 1975

Muthesius, Hermann. “New Ornament and New Art”. Dekorative Kunst, 4. 1901

Loos, Adolf. “Ornament and Crime, 1908”. Trotzdem. 1931

Clement, Gilles. “‘The Planetary Garden” and Other Writings” University of Pennsylvania Press. 2015

Image Credits

Frank Lloyd Wright, Robbie House, Chicago, IL. 1909-1910. Image by Tom Rossiter, date unknown

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Hill House Chair 1902. Render by Pixel Hearts, 2018

Jan Kotěra, Národní Dům, Prostějově, Czech Republic. 1905-1907. Image by Karel Boromejský Mádl, 1922

Josef Maria Olbrich, Hochzeitsturm, Darmstadt, Germany. 1907-1908. Image by Thomas Wolf, 2022

Peter Behrens, Technical Administration Building of Hoechst AG “Behrens-Bau”, Frankfurt, Germany. 1920-1924. Image by Infraserv GmbH & Co. Hochst KG, date unknown

Eugene Grasset. “Young Girl in the Garden”. Date unknown

Bartter 30

Hector Guimard, Castel Beranger, Paris, France. 1984-86. Image by Groume, 2013

Otto Wagner, Karlsplatz Stadtbahn Pavillon, Austria, Germany. 1899. Image by Pudelek, 2016

Maximilian Lenz, Le Peintre Friedrich Koning et Ida Kupelwieser dans une Foret, 1910

Adolf Loos, Villa Muller, Prague, Czech Republic, 1930. Image by Miaow Miaow, 2007

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, 1928-1931.

Image by August Fischer, date unknown

Mies Van Der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois, 1951. Image by Victor Grigas, 2013

Alvar and Elissa Aalto, Muuratsalo Experimental House, Muuratsalo, Finland, 1952-54. Image by Jonathan Rieke, 2013

Menges, Dorstelmann, Knippers, and Auer, Elytra Pavilion, London, United Kingdom, 2018. Image by the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2018.

Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), Proposed Project for the Jinghe New City Culture and Art Center, Jinghe, China, 2022. Image by ZHA, 2022

Bartter 31